Survey of London: Volume 46, South and East Clerkenwell. Originally published by London County Council, London, 2008.

This free content was digitised by double rekeying. All rights reserved.

'Clerkenwell Close area: St James Clerkenwell', in Survey of London: Volume 46, South and East Clerkenwell, ed. Philip Temple (London, 2008), British History Online https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vol46/pp39-54 [accessed 12 February 2025].

'Clerkenwell Close area: St James Clerkenwell', in Survey of London: Volume 46, South and East Clerkenwell. Edited by Philip Temple (London, 2008), British History Online, accessed February 12, 2025, https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vol46/pp39-54.

"Clerkenwell Close area: St James Clerkenwell". Survey of London: Volume 46, South and East Clerkenwell. Ed. Philip Temple (London, 2008), British History Online. Web. 12 February 2025. https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vol46/pp39-54.

In this section

St James's Church

St James's Church, erected in 1788–92, is the only known building of importance by the architect and surveyor James Carr. It replaced the ancient church of the Augustinian nunnery of St Mary, by then much altered but basically of the twelfth century. Part of this church had been used by the local inhabitants since the creation of the parish of Clerkenwell in 1176, and after the nunnery's suppression the building was retained as the parish church. The dedication, originally to the Virgin Mary, was augmented before 1500 to include St James the Less, and by 1540 the church seems to have been rededicated to St James alone. (fn. 1)

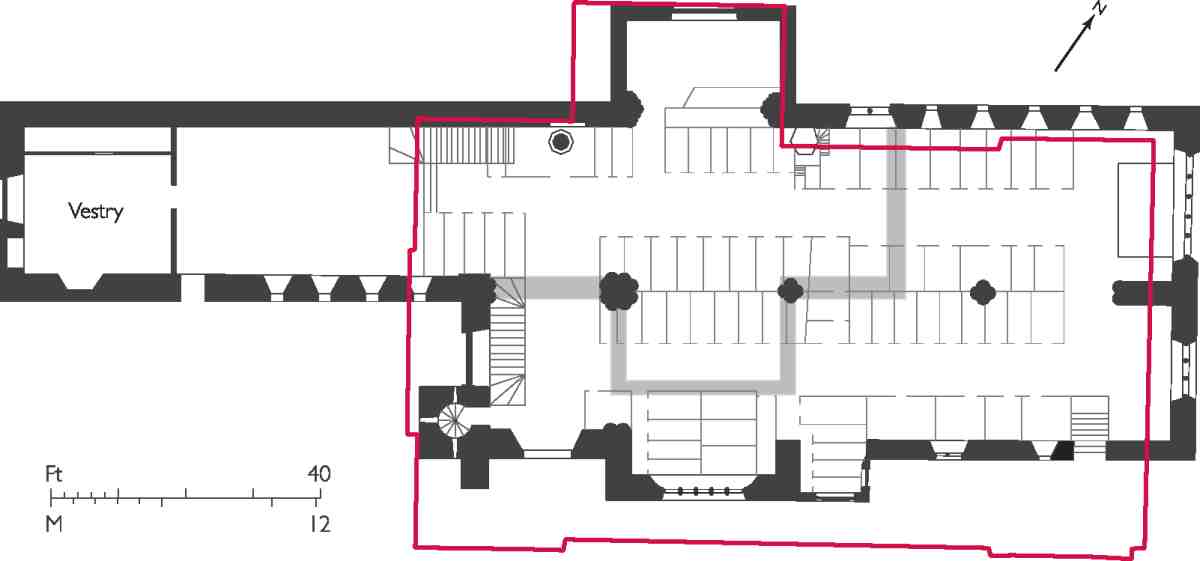

21. Old St James's Church, showing outline of rebuilt church of 1788–92 in red. The grey shaded portion indicates the probable extent of the original cruciform nunnery church of c. 1160

Of James Carr relatively little is known. (fn. 2) He was probably the Mr Carr who acted as surveyor to the Apothecaries' Company in 1785, and he was one of the City Road Turnpike Trustees from the 1780s onwards, and probably surveyor to the trust as well. (fn. 3) In Clerkenwell, he is known to have drawn up a plan for building on the Penton estate in 1781. At the time of his involvement with St James's and adjacent houses on the Newcastle House site (see above), he was described as of Artillery Place, Finsbury. In both these projects he was associated with James Fisher, a carpenter of Bunhill Row, who acted as his trustee in some deeds. (fn. 4)

The Old Church

The nunnery church

Little is known of the church as originally built, c. 1160, other than that it was a stone structure, probably cruciform in plan, and aisleless (Ill. 21). (fn. 5) All that survived subsequent reconstruction was the long, narrow nave and the north transept. A view made during demolition in the late eighteenth century shows remnants of blind arcading on the inner face of the nave's south wall, with scallop or chevron-moulded capitals—a characteristic Early English feature that originally may have extended around the other walls of the nave (Ill. 26).

More is known of the church as enlarged in the 1180s and 90s, after it took on the additional role of parish church, as essentially this was the form it retained until the rebuilding of the church in the 1780s (Ills 21–28). The major alteration was the demolition of the south transept and east end to make way for a much bigger and taller chancel with north and south aisles. At the east end of the nave and old crossing an extension was built to the south, with a square-plan tower and porch as a new public entrance. On the north side of the church a cloister was constructed, part of an enlargement of the conventual buildings. It has been suggested that these late twelfth-century additions may also have included a clerestory over the east end and crossing. (fn. 6)

22. Old St James's Church, from the south-west, c. 1750; the low building to the left of the tower is the former nunnery church nave

The most likely interpretation of this new arrangement would have seen the central chancel and north aisle of the enlarged east end, and the north transept—easily accessible from the conventual accommodation around the cloister—appropriated as the nuns' 'high quire'. This probably would have been screened off from the south aisle, which, with the tower and porch, served as the parish church, well placed for public access from the main nunnery gate to the south. The function of the nave after this reconstruction is less clear, though possibly it was reserved for brethren and other male members of the nunnery community, as the chaplains' accommodation was situated near by, on the west side of the precinct.

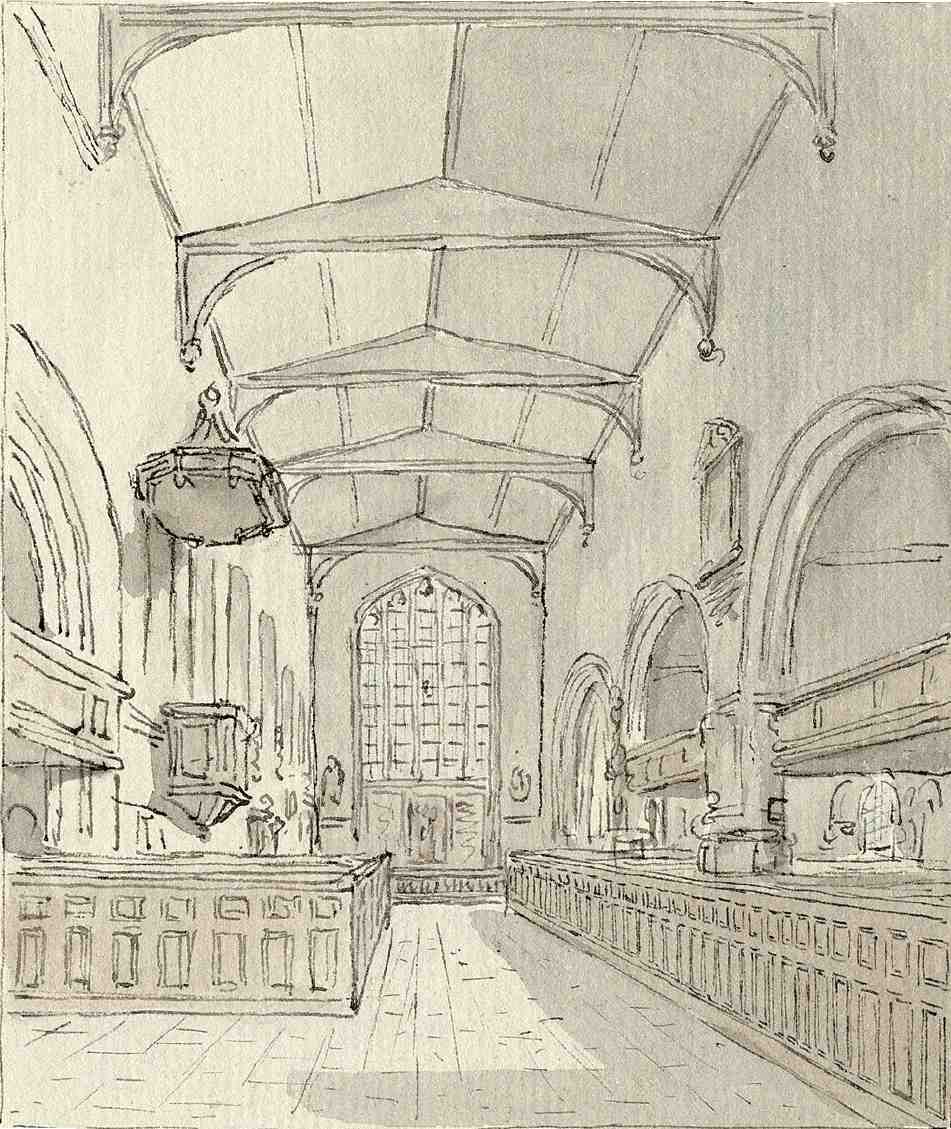

23, 24. Old St James's Church in 1788. Looking east into the chancel and (right) looking west

The arcades separating the new chancel and aisles comprised large semi-circular arches with rolled mouldings, supported on piers with clustered shafts (Ills 25, 26). Beneath the north-east corner of the tower was one particularly massive pier with eight shafts. Marking the entrance to the north transept was an arch and responds with smaller, more heavily clustered shafts and ribs, and chevron or scallop decoration.

After centuries of financial constraint, a major reconstruction of the church began in the late 1470s, funded partly by papal indulgences, partly by private benefactions, continuing into the early 1500s (Ills 23–26). A new roof was laid across the east end on a much shallower pitch, the gables and upper parts of the walls being rebuilt in brick. If there had been a clerestorey, it must have been removed at this point, and, perhaps to compensate for the loss, large Perpendicular windows were inserted in the east end, the north transept, and the lower stage of the tower. Both the body of the church and the tower were given stone battlements. With the reconstruction of the cloister, the north wall of the nave was entirely rebuilt with an outer face (to the cloister) of dressed ragstone rubble, into which were set the triple-shaft responds which supported the ribs of the cloister vaulting (Ills 27, 28). Part of this wall, now exposed in St James's Garden, is the sole remaining fragment of the nunnery to survive above ground.

Brackets either side of the main chancel window and five niches over the crossing arch shown in the eighteenth-century views appear also to be late medieval in date (Ills 23, 24). These were presumably intended for statues, most likely of Our Lady and St James at the east end; and perhaps of angels holding the five instruments of the Passion over the crossing, as this was a popular subject with female orders.

The church after the Dissolution

When the downfall of the church was decreed, its general

aspect was that of an edifice, antique indeed, but in which

nearly every ancient feature was so mixed up with modern

repairs, that few feelings of veneration could be excited by it. (fn. 7)

The local historian Thomas Cromwell's description of old

St James's on the eve of its destruction conjures up an

image of organic irregularity of the sort that taste then

and later found so unappealing. Had it not been demolished in 1788, the church would certainly have succumbed

to the improving hand of the High Victorian restorers.

St James's had survived the Dissolution more or less

intact, presumably because of its additional status as

parish church. According to Stow, it drew not only locals

but also worshippers from as far afield as Muswell Hill,

where some 65 acres of land once belonging to the

nunnery formed a detached portion of the parish. (fn. 8) Until

the Interregnum, St James's was privately owned, and

rented by its parishioners; but in 1656 they were able to

acquire the freehold, and, most unusually, held on to it

even after the Restoration in 1660. (fn. 9)

25, 26. Old St James's Church, demolition in 1789. The tower from the north transept arch and (below) looking towards the east window, with remains of twelfth-century blind arcading in old nave at extreme right

By the 1780s St James's was hardly recognizable from the outside as an ancient structure, its rough stone facing patched up in brick and partly covered in plaster, and with houses picturesquely built up against it, particularly at the south-west, next to Clerkenwell Close (Ill. 22). But essentially it was still the twelfth-century nunnery church. The long and slender nave had been adapted as a vestry and other offices, and worship was confined to the old chancel and south aisle, the north aisle having collapsed before 1587 (Ill. 21). The loss of the aisle apart, the greatest change to the fabric since medieval times had been the fall of the steeple in 1623 and the damage caused by the fall of its replacement during construction. This second collapse, due to neglect on the part of the builder, took with it the church bells, their carriages and frames, and part of the roof, 'the Weight of all these together, bearing to the Ground two large Pillars of the South Isle, a fair Gallery over-against the Pulpit, the Pulpit, all the Pews, and whatsoever was under, or near it'. (fn. 10) Construction of a new tower had reached as high as the church roof by 1627, but does not seem to have been completed till considerably later. Eighty feet high, square on plan, the tower appeared squat and massy, with heavy corner buttresses, and battlements originally coped with stone (Ill. 22).

As part of the reconstruction, a sort of transept was inserted at the junction of the nave and tower, where much of the damage had been done. Though it projected a little beyond the main walls at either end, the transept apparently 'made little appearance within'; but externally it was incongruous, the gable-ends of its steeply pitched roof a prominent feature in later views of the church (Ill. 22). (fn. 11)

St James's was the subject of a number of views by artists in the 1780s and early 90s, shortly before and during demolition, leaving behind a reasonably detailed record of its final form (Ills 23–26). To a large degree the heavy, clustered stone columns and semicircular moulded arches of the twelfth century still dominated the interior. At the east end the large perpendicular five-light window was one of the last significant alterations made before the nunnery's suppression. The roof, and most of the fixtures and fittings—including the oak box-pews, galleries, pulpit and tester, were of post-Dissolution date.

The west end was closed by a screen, built across the twelfth-century arch separating the crossing from the choir, and above this was a gallery for charity children, added in 1722 with money bequeathed by Thomas Crosse, of a local brewing family. On the south side of the nave were two other galleries: a private one for the Duke of Newcastle and his family, added in 1633, almost opposite the pulpit; and, in the next bay to the west, another known as 'Loveday's gallery', built with funds left to the parish in 1704 by Francis Loveday. (fn. 12)

27, 28. Old St James's Church, remains of the south cloister in 1786. View from north, showing eighteenth-century furniture warehouses; and (below) view east along the cloister walk

More than anything else the post-Dissolution church was noted for its fine series of funerary monuments, recorded sedulously by writers of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. A number that survived the rebuilding and were reinstalled in the new church are briefly described below. Important burials at the church included those of its founder, Jordan de Bricet and his wife, Muriel de Munteni, in the chapter-house; Isabella Sackville, the nunnery's last prioress, whose grave lay near the high altar; and Sir William Weston, prior of St John's monastery at the time of its suppression in 1540, who had a spectacular monument set against the north wall of the chancel (see Ill. 159 on page 133). (fn. 13) Thomas Dekker, the playwright, was buried at the old church in 1632, and in the mid-seventeenth century two of Izaak Walton's sons were buried in the churchyard, as was Thomas Britton, the 'musical small-coal man' (see page 139). (fn. 14) Daniel Defoe's first child, Daniel, was baptised here in 1708. (fn. 15) Samuel Pepys recorded his attendance at the church on several occasions between 1661 and 1668, in the hope of catching glimpses of two local ladies, the beauteous Frances Butler and the remarkable Margaret, Duchess of Newcastle.

Decorative improvements and 'beautifyings' of the church were made on several occasions during the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, but little seems to have been done to address the building's structural defects. Few important alterations were made after about 1700, but one, the cause of controversy, was the erection of a new reredos in 1735. This was a sort of triptych in the form of an architectural façade, with Corinthian pilasters and a broken pediment with a bishop's mitre occupying the break (Ill. 29). It caused great offence because of the subject matter of its paintings: a central panel of the Nativity with the Virgin Mary, and two flanking panels with images of Moses and Aaron. One correspondent to the Bishop of London denounced it as 'the Reproach of Protestantism, and very near ally'd to Images, which we so justly condemn in the Church of Rome'. A later description suggests that a vase subsequently took the place of the mitre; no doubt the offending pictures were also covered up or replaced. Carter's sketch of 1788 (Ill. 23) suggests a central picture (but no pediment), flanked by panels of writing. (fn. 16)

The New Church

By the early eighteenth century the poor structural condition of the old St James's was recognized. 'Our church', its churchwardens noted at the time of a visitation in 1711, 'hath lately been Beautify'd both within and without at the Charge of the Parishioners but it is in a very weak & crazy condition not capable to be long supported by the inhabitants'. (fn. 17) But though the church-building commission set up in that year identified the parish as one where an additional church ought to be built and looked into sites, rebuilding the old church was not considered. Instead, it was decided to purchase the remnant of the priory church of St John as a second church for Clerkenwell (see page 128). (fn. 18)

The question of rebuilding finally came to a head in 1786, when the Vestry set up a committee to look into the matter. Having contemplated reconstruction, a majority on the committee voted for another round of repairs. But an examination of the fabric by the Vestry's surveyor, Francis Carter, and another surveyor-architect, James Carr, found it to be in a parlous state; brought in to give a second opinion, the county surveyor, Thomas Rogers, condemned it outright. That convinced the committee to change tack and opt for rebuilding. Carter and Carr were appointed joint surveyors for the new church. In April 1787 they produced a ground plan, which was approved despite a last-ditch attempt by some vestrymen to keep and repair the old tower. Soon Carter dropped out, and Carr became sole surveyor. (fn. 19)

29. Reredos erected in 1735 in old St James's Church

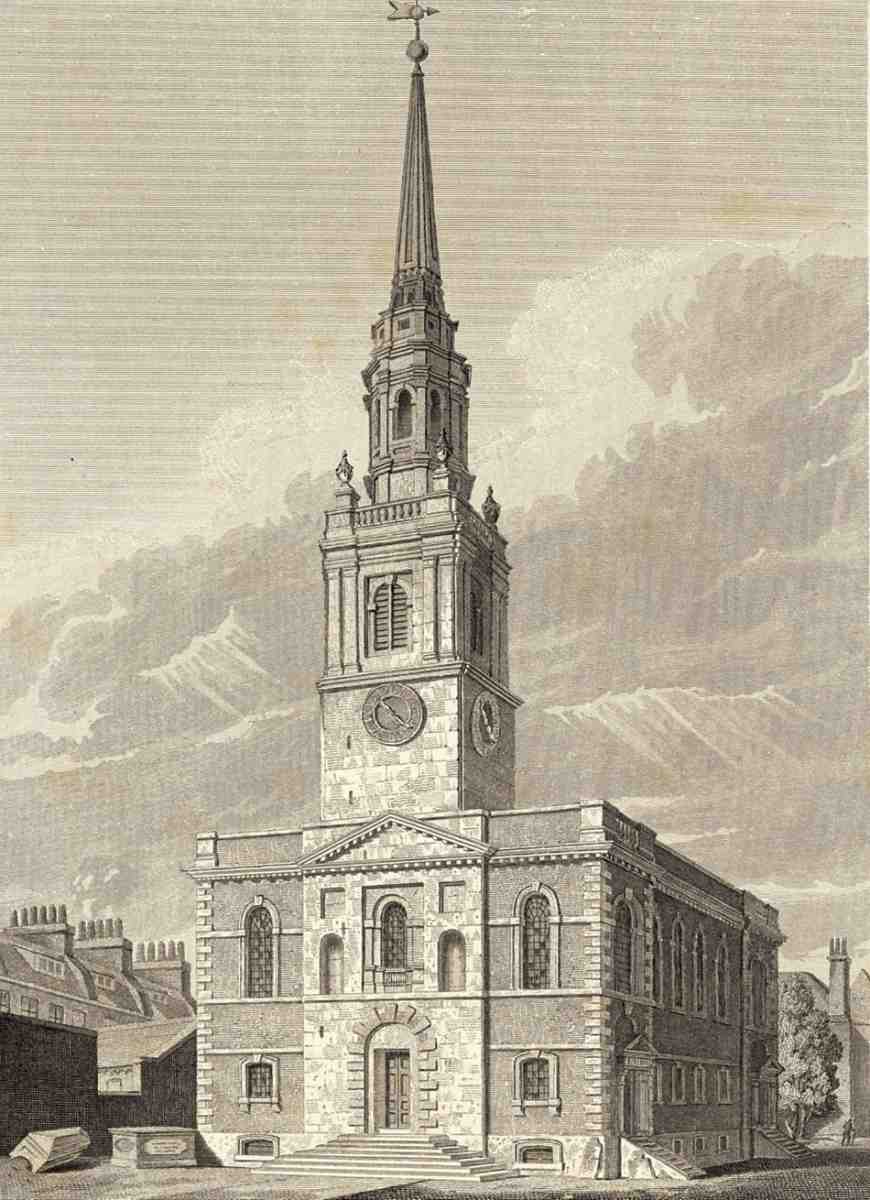

30. St James's Church, west end. Drawing by John Coney, 1818

As often in Georgian church-building, it was necessary to secure a special Act before anything could be done. Passed early in 1788, this sanctioned the removal of the old building and empowered a large body of trustees to raise up to £8,000 on the security of the rates for the new one by means of subscriptions and annuities. It was supplemented by a second Act in 1790. (fn. 20) Demolition of the old church had started by May 1788. Of the old materials a portion, it was reported that autumn, 'is now working up into houses in St George's Fields' (Southwark), while some found its way to Islington for use as hardcore in the foundations of a chapel, in what is now Gaskin Street. (fn. 21) Following competitive tenders, the building contract was awarded in August to John Lee, William Fielder and William Hopcraft, the last identifiable as a stonemason. (fn. 22) The arched vault or crypt of the new church was constructed 'over the same parts of the former structure', (fn. 23) and therefore to some extent the size and alignment of the building was dictated by its predecessor. Nothing of the old fabric appears to have been retained, however. But the more compact form of Carr's building permitted much of the old nave with the vestry room at its west end to be retained during the works, 'as decently fitted up as possible for prayer and preaching', until its successor was ready. (fn. 24)

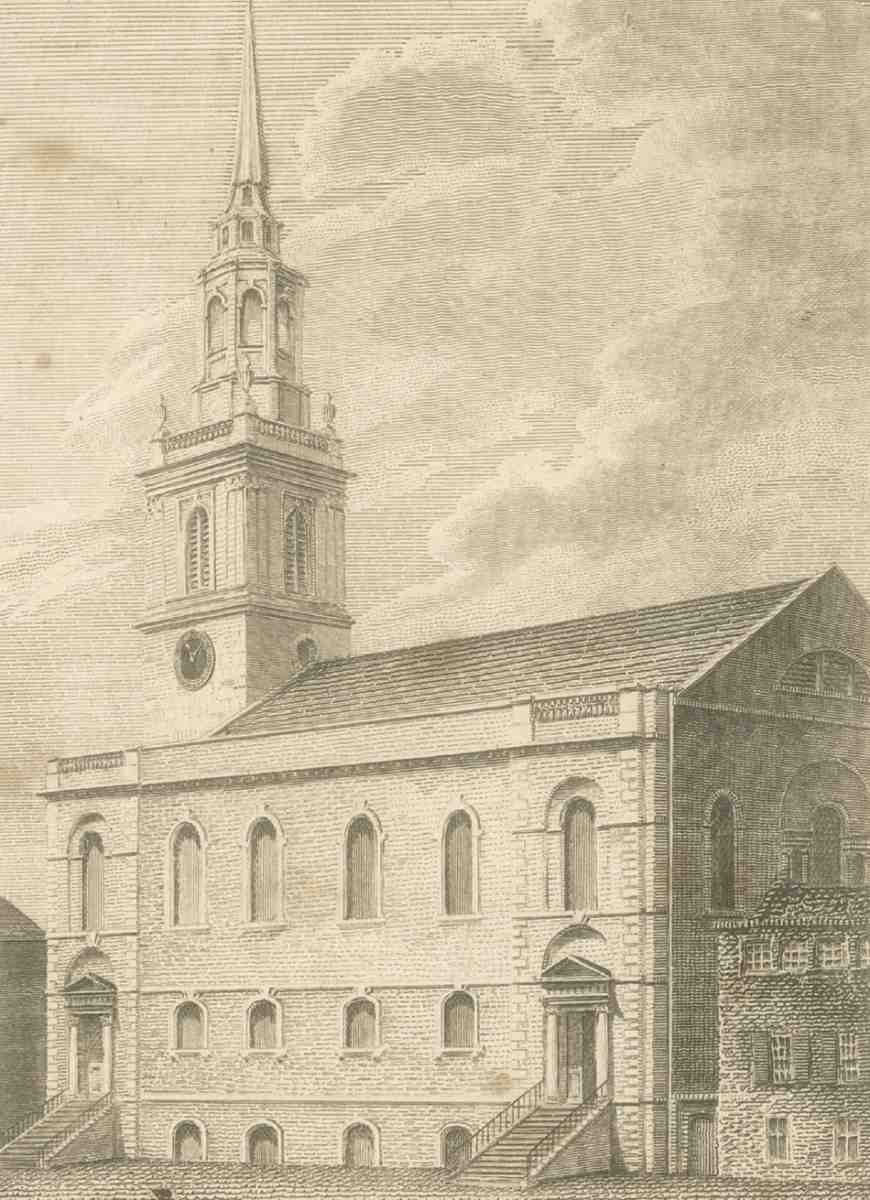

31. View from the south-east by S. Rawle, 1799

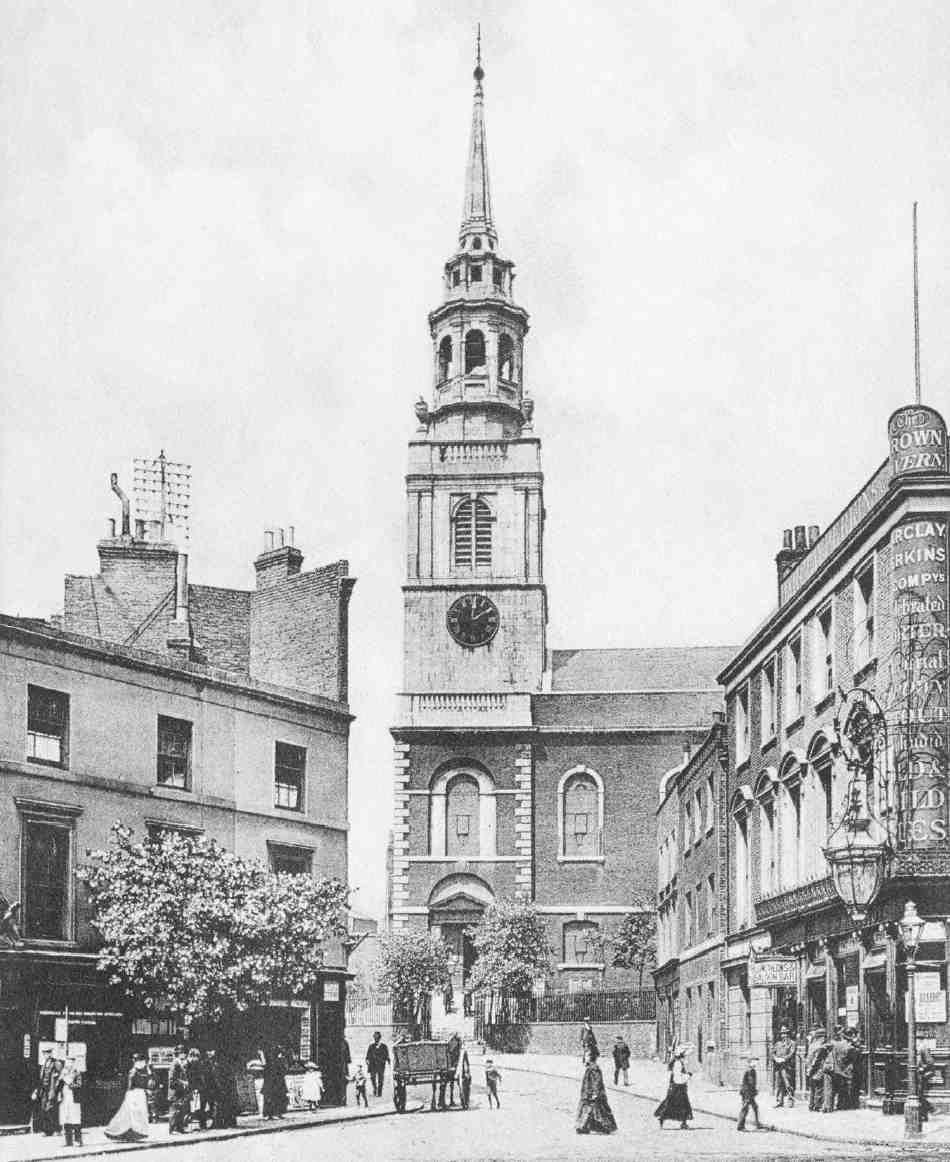

32. View from Clerkenwell Green, c. 1900

33. View from the churchyard in 2007

St James's Church, Clerkenwell Close. James Carr, architect, 1788–92

34. Looking east from the gallery

35. Looking west

36. Altar, reredos and east window

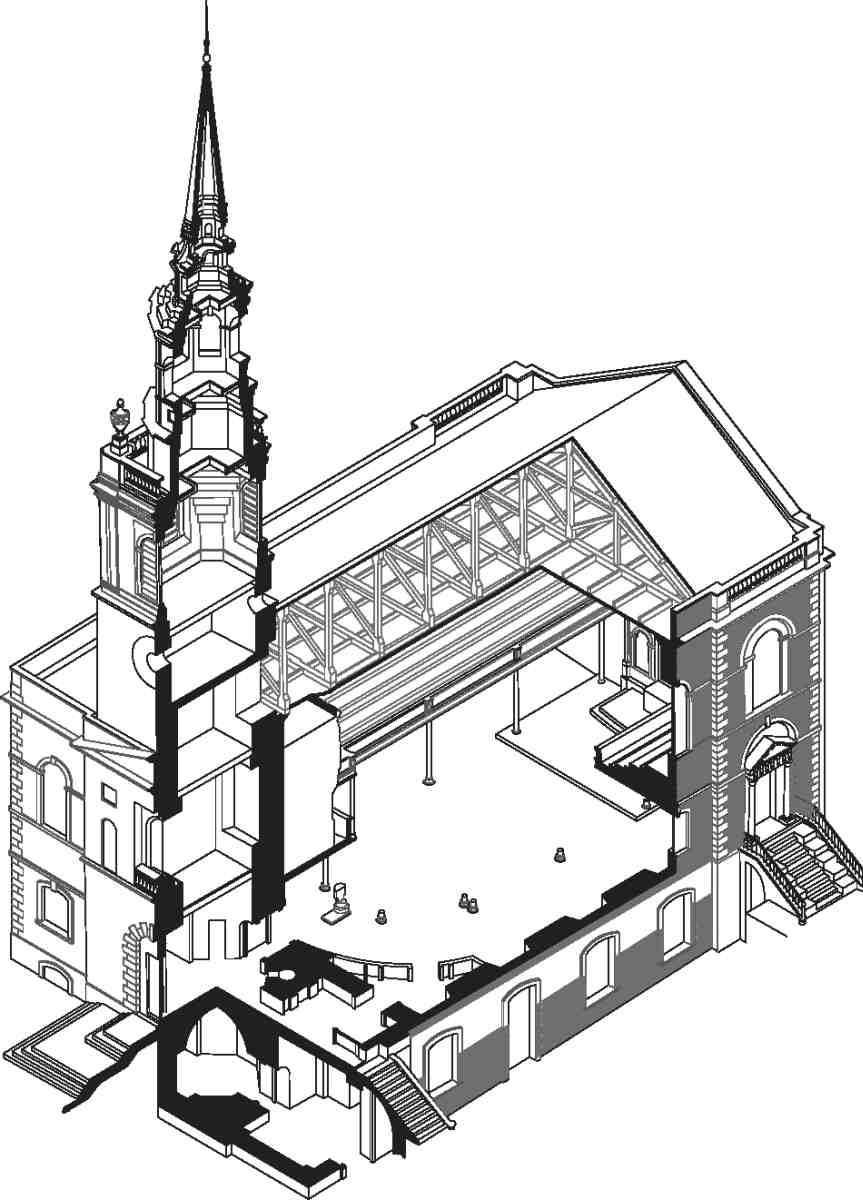

37. St James's Church, axonometric view of church and steeple

The foundation stone was laid on 16 December 1788, scaffolding on the spire was struck at the end of March 1791, and consecration took place on 10 July 1792. (fn. 25) The total cost was reckoned afterwards at £11,674. (fn. 26)

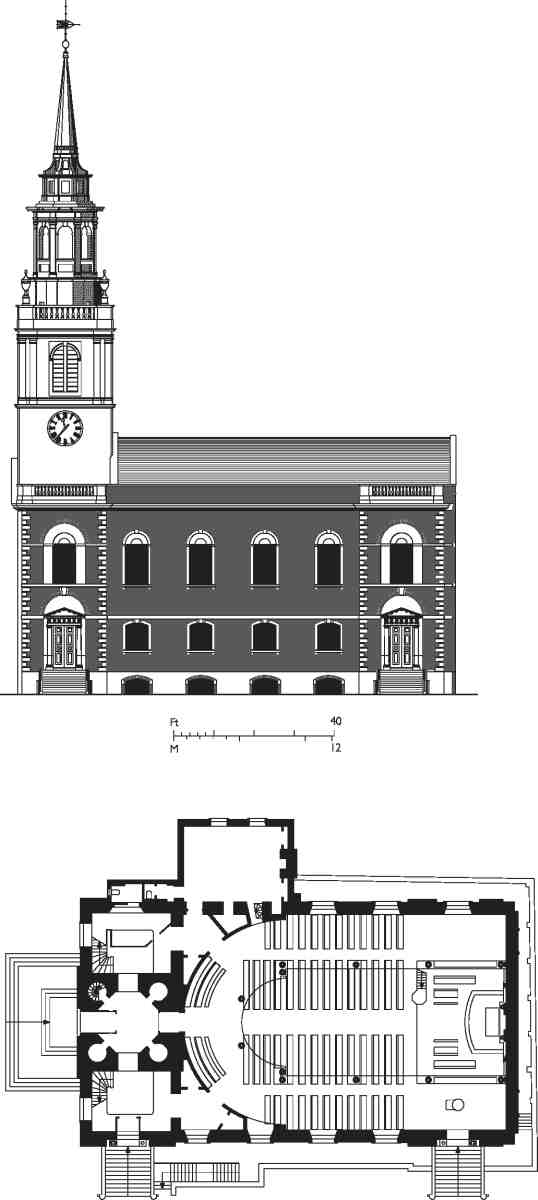

Exterior

St James's is a fairly plain Georgian preaching box, wanting the geometrical conviction of London's best churches of the 1780s and 90s, such as Plaw's St Mary's, Paddington Green, or Spiller's St John-at-Hackney. What it lacks in architectural flair it makes up for in its elevated, village-like setting, just above Clerkenwell Green (Ill. 32). The west and south-west aspects, enlivened by the sweep of Clerkenwell Close and by Carr's fine if old-fashioned tower and steeple, have always been those most cherished. Originally old houses abutted close upon the east end, but that did not prevent Carr from providing an ample louvre under the gable to ventilate the roof, and below it the frame of a large Venetian window, blocked at first (Ill. 31). The north side was equally hemmed in, partly by a row of new houses also due to Carr (see above), and made irregular by the prominent projection of the vestry. The basic material of the exterior is brick, set off by Portland stone for dressings and architectural features. The roof, carried on nine king-post trusses, is shallow-pitched and slated (Ill. 37).

The ends of the open elevation to the south are embellished with two pedimented doorways, framed in the Tuscan order which runs quietly but consistently through the church's major features. The doors (the eastern one now blocked) are reached up steep flights of steps flanked by plain iron railings which appear to be of the early nineteenth century. But the principal approach to the church was from the west, where a portion of the Newcastle House ground was incorporated into the churchyard. (fn. 27) The flat-fronted and pedimented centrepiece on this elevation is faced in stone to read with the tower and steeple, while a three-sided flight of steps leads up to the rusticated west doorway (Ill. 30).

The square stone tower rises in two stages from the body of the church, surmounted by a steeple. This steeple, based on long-established models like St Martin-in-theFields and St Giles-in-the-Fields, was an afterthought. Carr's original design had called for a three-storey tower topped off with a wooden dome or cupola. Shorn of one storey in May 1788, the revised design is shown on the obverse of a medal struck to serve as a pass to the site. (fn. 28) The trustees evidently harboured ambitions to substitute a stone cupola for the wooden one. At first the extra cost deterred them, but in November 1790, with work on the tower well advanced, the wooden cupola was ousted in favour of the high stone steeple. A model of this was ordered from James Fisher and survives in the vestry room. (fn. 29) The tower contains a clock, with dials on three sides; the mechanism was made by the local firm of Thwaites in 1791. (fn. 30) Above the clock is a bell chamber with eight bells, seven of which were recast in the same year by Thomas Mears from the six bells in the old church. The first peal was rung in September 1791, well ahead of the consecration. (fn. 31)

Interior

The west end consists of three compartments, with two double-height stairwells of generous dimensions flanking a lower octagonal central lobby. In the side compartments stone staircases with winders lead up to the galleries. The sheet-metal 'modesty boards' attached to the plain iron railings are presumably original; in 1792 the trustees agreed 'that something is necessary to be placed against the Balusters on the Gallery Stairs of a proper Height to screen them from the site [sic] of Persons below'. (fn. 32) All these spaces have been little altered. They have dado-height panelling, now painted, with plastered walls.

In the body of the church (Ills 34, 35), the main components of the galleried interior are also still Carr's, despite many later alterations. The most fetching feature, and the chief clue to its date along with the delicate plasterwork of the ceiling, is the curved west end, reminiscent of urban nonconformist chapels. Originally the interior was box-pewed. The pews on the ground floor were divided into two ranks with a wide central aisle between them, in which were placed three Honduras mahogany benches (soon augmented). The only survivals of the original seating are below the west gallery, the Corporation Pew to the south and the Church Officers' Pew to the north. These, along with the dados lining the aisles, are grained. Towards the east end, a high central pulpit and sounding board flanked by a clerk's desk dwarfed the communion table and reredos behind. Carr's first proposal for the pulpit took up too much room, so early in 1792 he designed another, with a hexagonal plan and a circular stairway. (fn. 33)

At the east end is a chaste tripartite reredos in the Tuscan order, with attached columns, pilasters, frieze and pediment, surmounted by a large Venetian window (Ill. 36). It was considerably altered in 1881–2. As first erected the reredos was lower than its present position, and 'painted in wainscot' to look like oak, with pillars and pilasters marbled. It framed four round—headed panels inscribed with the Lord's Prayer left of centre, the Commandments in two narrow central panels beneath the pediment, and the Creed right of centre. Only the panels bearing the Lord's Prayer and the Creed survive, relettered and relocated left and right to the sides of the reredos. The pediment was originally crowned by the arms of George III, executed in Coade stone and dated 1792 (now to be found in the entrance lobby above the door into the nave). On the entablature to either side stood two 'flaming urns' of Adamesque profile, also of artificial stone. The crown and palm branches in the tympanum of the pediment were originally gilded, while gilt flowers also filled the metopes of the entablature. On either side of the reredos the walls were decorated with gilt plaster bas-reliefs of the communion utensils and other items, suspended by ribbons. (fn. 34)

A striking difference between the interior as first built and its present-day appearance lies in the treatment of the area over the reredos. Originally the Venetian window opening here was blank, since houses behind entirely screened the eastern elevation. (fn. 35) In February 1792 the trustees accepted an offer from Thomas Greenwood, scene-painter at Sadler's Wells, Covent Garden and Drury Lane theatres, to paint free of charge, 'some ornaments at the east end of the church'. Four panels on frames were made to fill up the openings. On the central panel Greenwood painted the word 'Jehovah' in Hebrew, surrounded by a glory under a curtain, on the two side panels he painted various sacred emblems, and, on the semicircular panel at the top, infant angels and a dove descending. (fn. 36) No illustration is known of this rare feature, which disappeared in or before 1863.

Only the main gallery is original, the upper tier being a later addition. It is supported by Tuscan columns, hollow and enclosing iron cores. They are doubled up at the junctions with the western curve and at one time were painted to resemble veined marble. (fn. 37) The finest feature of the gallery, and indeed of the church as a whole, is the organ with its noble frontispiece, built in 1790–2 by George Pike England (see below).

38. St James's Church, south elevation and plan in 1933

39. St James's Church, looking west in 1858

A complete list of craftsmen who worked on the new church does not survive, but some names are known. The original light fittings, including a three-tier 36-light central candelabrum, were produced by the Hoxton brassfounders John Horsley & Son, but do not survive. Much of the furniture, including the pulpit, was provided or executed by the Aldersgate firm Gilding & Banner, which was based temporarily in Newcastle House adjoining the church at this time or shortly before (see page 36). (fn. 38)

Alterations since 1792

One early change to the church considered, though in the event not carried out, was the building of a western portico. At some stage Carr must have designed one, because when in 1812 the Trustees met to consider buying some columns for a portico, he produced his original plan (and two alternatives) and persuaded them not to proceed. (fn. 39) The portico was again discussed but rejected in 1824, and again in 1829–30. (fn. 40) No more is recorded of the matter in the trustees' minute books. But that some sort of competition for the portico may have been held around the latter date is suggested by a drawing, now known only from a photograph, inscribed with the romantic Italian motto Celato Nondimeno in Terra and bearing the date 1829. It shows a domed Doric circular portico of monumental grandeur, with a tetrastyle propylaeum in front for the approach from Clerkenwell Close. This rather juvenile design may relate to the fashion for urban improvement schemes around 1830. (fn. 41)

The first major executed change to the interior took place in 1822, when an upper tier of galleries was added to provide seating for some 500 children (Ill. 39). Hitherto they had been crammed into two recesses at the west end over the doors on to the main gallery. (fn. 42) Carr having died by then, the new galleries were designed by a Mr Blyth—probably the surveyor Andrew Blyth of Goswell Street—and made by Reddall & Ashby, carpenters and window manufacturers. Originally they extended from the organ right round to the east end, carrying across and partially obscuring the upper windows of the nave, and in the opinion of Thomas Cromwell 'improving the general aspect by relieving the former blankness of the walls'. They could be reached either from the two main staircases at the west end (whose reinforcement with iron columns and girders probably dates from this time) or from two new, very tight staircases boxed into the north-east and south-east corners of the church. Supported on slender iron columns, the upper galleries were 'light and not inelegant in appearance', with pretty ironwork fronts. (fn. 43) All that survives of them are two quadrants flanking the organ, which continue to add a theatrical touch to the interior (Ill. 35). In 1824, just after these galleries were installed, the sounding board was removed from the pulpit, presumably because it blocked the view of and muffled the sound of the preacher for those sitting high up. (fn. 44)

In a survey of 1843, the trustees' surveyor Ebenezer Perry found the upper part of the steeple to be 'considerably out of perpendicular' and 'quite far enough advanced towards a state of danger that its reinstatement should be no longer postponed'. (fn. 45) Nothing was done, however, until 1849, when in the wake of wind damage which took off the weather vane, the upper part of the spire was dismantled and rebuilt in Portland stone. Erected under the supervision of the local architect William Pettit Griffith, the replacement spire was apparently a faithful facsimile of the old. (fn. 46)

The inevitable Victorian refurbishment of St James's, though postponed until as late as 1881–2, was 'so radical as to amount to a transformation'. (fn. 47) The job of making this typical Georgian urban church interior more sacramental and therefore directed towards the altar was entrusted to Arthur W. Blomfield, architecturally expert in such conversions. On this occasion Blomfield appears to have subcontracted most of the work to his principal assistant, J. S. Paul, who is jointly credited with his master. The builders were Dove Brothers, equally experienced in such tasks; they also undertook a general restoration of the fabric. To achieve the desired liturgical result, the east end of the nave was raised a step and a squarish chancel area formed with a mosaic floor and choir stalls. The oldfashioned high box pews in the main body of the church were replaced with oak benches; and the 1822 galleries were cut back at the east end, the subsidiary staircases being removed. The pulpit and reading desk were cut down and the pulpit resited to one side. A brass eagle lectern, given by the Clerkenwell Lodge of Freemasons, was also installed. (fn. 48)

In 1899 another round of renovation and redecoration saw the extension of the mosaic pavements to the nave and aisle passages, the erection of a wrought-iron chancel screen, the installation of electric light, and the final ousting of the old wooden pulpit. This last was replaced by an open iron pulpit incorporated high up within the chancel screen itself—a 'curious though not unpleasing device' in the view of the Daily Graphic. The work was carried out by Campbell, Smith & Co. under the superintendence of J. S. Paul & Sons. (fn. 49)

The present appearance of the interior is largely as altered by Dove Brothers following a report by the architect Thomas Ford in 1938. A restoration of the fabric in 1939 preceded substantive internal changes, apparently carried out during the early months of 1940. Ford removed Paul's iron chancel screen and integral pulpit and further cut back the upper galleries, leaving only the two short surviving stubs on either side of the organ. He also installed the present wooden pulpit. (fn. 50) In the 1990s Blomfield and Paul's choir stalls and lectern were removed.

Furnishings and fittings

Reredos. Original wooden reredos remodelled by Blomfield and Paul, and raised 'to make the caps of columns range with cornice of gallery'. (fn. 51) The present three-arched openings with their subsidiary pilasters all date from 1881–2, as do the fibrous plaster panels they contain painted with the Commandments to the sides and the Communion injunction in the centre, and probably also the white-and-gold colour scheme. Of the four panels from the original arrangement two survive (inscribed with the Creed and the Lord's Prayer), resited on either side of the reredos.

Communion table. Bow-fronted, of mahogany inlaid with boxwood. Ordered in 1792 from the cabinet-maker Francis Gilding, of Gilding & Banner. (fn. 52)

Communion rails. The main section of these wrought-iron rails is also original, although they have been much altered, probably in 1881. (fn. 53)

Pulpit. Made from old pews in 1939, apparently to the design of Thomas Ford. (fn. 54)

Reading desks. The two reading-desks in the chancel are probably remnants of Blomfield and Paul's fittings, 1881–2.

Fonts. The main font is a circular stone basin on squat Romanesque marble pillars, installed by Blomfield and Paul in 1881–2, now in the south-east corner. A portable early nineteenth-century font of rosewood with a tricorn base, given by Michael Gillingham, stands near the pulpit. The original font, designed by Carr, was a 'handsome basin and pedestal of marble', though smaller than he had intended. Its position is not known. It was replaced in 1851 by a font designed by W. P. Griffith, who also raised the money to pay for it. Carved from Portland stone by the mason John Malcott, it consisted of a lead-lined bowl decorated with carved leaves, raised on a stumpy column with a moulded base. A simple Jacobean-style oak cover was given by a parishioner. (fn. 55) Griffith's font latterly stood at the west end of the central aisle, below the organ, where its successor may also have originally stood. (fn. 56)

Organ. By George Pike England, and inscribed on the front of its case 'England fecit 1792'. One of this distinguished maker's earliest instruments, it replaced an organ built for the old church in 1749 by his grandfather, Richard Bridges. The new instrument impressed the professionals, the organists at Windsor Castle and the Chapel Royal in St James's telling the building trustees that they 'could not have had a better one made anywhere'. (fn. 57) It was enlarged in 1877 by Gray & Davison and extensively altered in 1928–9 by Alphonse Noterman, who brought forward the case, building what was effectively a new organ inside with a detached pneumatical-action console in the gallery to the south. Noterman's changes were undone in 1978 when Noel Mander, a descendant of England, rebuilt the instrument 'on 18th-century foundations'. In twelve of the twenty-two speaking stops, the pipework is mostly England's. (fn. 58) Mander also restored England's mahogany case and scarlet paint to the carved drapery and hangings over the lower flats and central tower. The three finials on the pipe towers are not England's. The central finial, a sort of plumed helm almost touching the ceiling, was in place by 1941, when the two flanking towers terminated in hemispheres topped by decorated cones. Mander replaced these with the two flaming urns which had stood on either side of Noterman's console. (fn. 59)

Figure of St James the Less. Probably dating from the eighteenth century, this stands over the inside of the main door from the central lobby into the church. It stood over the poor-box in the old parish church, and was then for many years in the vestry room of the present building. (fn. 60)

Stained glass

Stained and coloured glass was first introduced to the church in the 1860s. (fn. 61) During the 1881–2 reordering all the remaining clear glass was replaced by tinted cathedral glass. The earliest and largest of the stained-glass windows is the garish Ascension scene filling the Venetian east window, installed in 1863 by Alexander Gibbs & Co. to replace Greenwood's painted panels. The treatment of the subject attracted some criticism, especially the inclusion of the Virgin among the Apostles. The window is historically significant as an early example of the 'Raphaelesque' school in Victorian stained glass. (fn. 62)

East end. The two pictorial windows flanking the main east window, showing 'The Building of the Temple' (north) and 'The Queen of Sheba visiting the Temple on its completion' (south), were installed in 1882 as a gift from the Crusaders' Lodge of Freemasons, to designs by Charles Evans of Warwick Street. Masonic emblems and the arms of several lodges are included. (fn. 63)

North side (under gallery). East: Memorial to Ephraimia, wife of the Rev. Robert Maguire, by Heaton, Butler & Bayne, 1866, and described as 'of the German School'. (fn. 64) Centre: Memorial to Helen Augusta Paget, made by James Powell & Sons, 1892, repeating a design by George Woolloscroft Rhead first used at St Stephen's church, Dublin. West: Memorial to the Rev. John Henry Rose, vicar, signed by T. F. Curtis of Ward & Hughes and dated 1899.

40. St James's Church, view from south-west stairs, showing (left to right) Burnet, Penton and Crosse monuments

South side (under gallery). East: Commemorating the Rev. Robert Maguire's first ten years as incumbent, by Cox & Son, 1867. (fn. 65) Centre: Memorial to the Rev. C. J. Parker, vicar, by William Morris & Co. (Westminster), 1938. (fn. 66) West: Memorial to Benjamin R. Moore, clockmaker, by Arthur Louis Moore, signed and dated 1882.

South side (over gallery). East: Memorial to Colonel Henry Penton (d. 1882), by John Jennings, founder of the Lambeth Art Glass Works.

Monuments and memorials

The best monuments are all from the old church. A few of the more notable were re-erected at the expense of the Trustees; otherwise, old memorials were installed in the new church only if relatives or other interested parties footed the bill. (fn. 67) Among the old monuments destroyed were those of Isabella Sackville, last prioress of St Mary's nunnery; Thomas Bedingfield, Master of the Tents and Pavilions to James I; and John Weever, the poet and antiquary. Only the monuments to Thomas Crosse, William Wood and possibly Henry Penton were immediately installed in the body of the new church. Others were originally stored in the crypt and only gradually moved up during the nineteenth century. Two older monuments re-erected in the new church were the mutilated effigy of Lady Elizabeth Berkeley (d. 1585), lady of the bedchamber to Elizabeth I, illustrated by Pinks (fn. 68) and now preserved in an ante-room, and the skeletal effigy of Sir William Weston, the last prior of St John's monastery. The architectural setting of Weston's tomb (see Ill. 159 on page 133) was destroyed in 1788, but his effigy was preserved and in 1882 placed under the easternmost window on the north side of the nave, a site comparable to its position in the old church. In 1931 it was removed to the crypt of St John's Church (see page 133). (fn. 69) The first new monument, erected in 1792, was an oval tablet to the minister, the Rev. William Sellon, put up by his son. (fn. 70)

41. St James's Church, monument to Countess of Exeter (d. 1654)

The following is a select list of monuments, chronologically arranged.

John Bell (d. 1556), Bishop of Worcester 1539–43. Brass, the oldest memorial in the church. Bell retired to Clerkenwell and was buried in the old church. The top of his crozier, long missing, was restored in the 1990s, having been found in Hereford Cathedral.

Elizabeth, Countess Dowager of Exeter (d. 1654). Marble mural monument with heraldic carving (Ill. 41).

Sir William Wood (d. 1691), marshal of the Society of Finsbury Archers and author of The Bowman's Glory, or, Archery Revived. Inscribed tomb-stone which stood outside the old church, against the south wall. In 1792 it was placed on the wall of the south gallery staircase, the Toxophilite Society of London having paid for its restoration. (fn. 71)

Elizabeth Partridge (née Holder, d. 1702, aged 17). A Baroque cartouche with weeping putti, drapery, skull and a half-length alto relievo of Elizabeth herself in a roundel. It has lost its original colouring and gilding, and shield with impaled arms of the Partridge and Holder families. Stored in the crypt until placed in its present position in 1858. (fn. 72)

Thomas Crosse (d. 1712) and his wife, incorporating portrait busts of the couple (Ill. 40). Erected in 1722 at the Vestry's expense in recognition of Crosse's 'great acts of charity to the poor of this parish'. By an unknown sculptor. The long-accepted attribution to Roubiliac, who did not come to England until the 1730s, is now rejected on grounds of both chronology and quality. (fn. 73)

Gilbert Burnet, Bishop of Salisbury (d. 1715). This inscribed black marble floor slab, one of two memorials to Burnet in St James's, originally covered his grave in the old church which was near the altar. It was cut by Edward Stanton. (fn. 74) The second memorial was put up by the Vestry in 1715. Architectural cartouche, incorporating scrolls and books (including Burnet's own History), surmounted by his arms under a mitre. Signed Robert Hartshorne, one of Edward Stanton's assistants. Stored in the vaults after rebuilding, it was restored and fixed in the south staircase compartment in 1819 (Ill. 40). (fn. 75)

Henry Penton of Lincoln's Inn (d. 1715), purchaser of what became the Pentonville estate. Decorated marble obelisk wall tablet (Ill. 40).

John Short (d. 1794), late of Edlington, Lincolnshire, and a lord of the Manor of Clerkenwell. Marble wall tablet with coat-of-arms.

Thomas Greatorex (d. 1824) and his sister, Mrs Mary Fox (d. 1840). Neo-Hellenic tablet, signed J. Hollis of Goswell Road.

William Clare (d. 1838) and his wife, Sarah (d. 1845). Signed John James Sanders of Keppel Row, New Road.

Abud family (d. 1827, 1842 and 1848). Signed John Malcott of Newgate Street, who was also responsible for James Carr's monument in Cheshunt Church, Hertfordshire, (fn. 76) and W. P. Griffith's font of 1851.

Rev. W. E. L. Faulkner (d. 1856). Signed James Samuel Farley of Goswell Road.

Memorial to victims of the Clerkenwell Explosion. An emotionally worded tablet to the six people killed in 1867 when an attempt was made to free Fenians awaiting trial in the nearby Middlesex House of Detention.

Memorial to the Protestant Martyrs, consecrated 1963. Black painted board with the names inscribed in gold of the 66 Protestants burned at Smithfield during the reign of Mary Tudor. The martyrs were formerly commemorated in the Smithfield Martyrs Memorial Church, demolished in 1955 (see page 313). (fn. 77)

Vestry Room

On the north side of the church is the vestry room, entered from the north vestibule and lobby. An original feature of Carr's church, it is an airy and well-lit space, the trustees having ordered that it should be more than two feet six inches higher than Carr had originally intended. (fn. 78) The room retains its original wooden chimneypiece, tall panelled dado and various doorways, some giving access to cupboards. Gilding & Banner supplied a suite of mahogany furniture in 1792, comprising two seven-foot tables, four benches, each four feet long, one large chair and six small ones. (fn. 79) None of these pieces remains in the room, but a mahogany armchair now in the chancel may be part of this set. On a bracket above the fireplace is Fisher's model of the steeple, adapted as a clock.

Crypt

Beneath the church is a large crypt (Ill. 42), 102 ft by 53 ft, with simple quadripartite brick vaults originally supported on brick piers, and intended for storing the coffins, grave slabs and many of the monuments salvaged from the old church. More of a semi-basement than a true crypt, it was commended by Pinks for not having 'that gloomy cheerless aspect common to such places of sepulture … being well lighted and ventilated' by open windows, on all four sides, filled only with protective iron grilles. (fn. 80) Having been reorganized by Blomfield and Paul in 1882, it was cleared of coffins in 1910–11, when it was converted into a hall or schoolroom with a stage, a gymnasium and other rooms off. The floor was then lowered six feet, the brick piers were removed and replaced by steel girders resting on pairs of cast-iron columns, and the windows lengthened and glazed. (fn. 81)

42. St James's Church, view of crypt in 1995

Churchyard and St James's Garden

The spacious area of grass and trees surrounding St James's Church today contrasts with its original cloakedin situation, houses then abutting closely to the building on the north and east. Those to the east were already old, but those on the north, replacing Newcastle House and its garden, were the private speculation of the church's architect (page 36). So concerned were the trustees that in 1792 they sought agreement with Carr to secure sufficient light to the new vestry room. (fn. 82) They also acquired from him a small piece of the Newcastle House ground to make a proper entrance to the west door of the church. The iron railings around the west and south-west borders of the churchyard, erected on a brick retaining wall with castiron copings, date from this period. They have gates with overthrows and oil-lamp holders aligned on the west and south-west doors.

To the south-east of the church, a large piece of ground was taken from the Green and added to the churchyard. This was enclosed by a low wall and railings, with a gate at the corner, from where a path led diagonally to the south-east door of the church (see Ill. 98 on page 92).

Burials having ceased, in 1890 the graveyard to the south and south-east of the church was laid out as a public garden to the design of the Vestry's surveyor, William Iron. A small portion along the east side was sacrificed to widen St James's Walk. (fn. 83) Nothing survives of Iron's layout of curving walks, but some of the plane trees in this part of the churchyard probably date from that time (Ill. 33).

Drastic clearance for a public open space planned by the London County Council in the 1960s would have swept away most of the buildings on the north side of the Green and left the church in more or less splendid isolation. Some ground north and east of the church was cleared, and with the abandonment of the scheme was laid out as a garden and children's playground called St James's Garden.