Survey of London: Volume 46, South and East Clerkenwell. Originally published by London County Council, London, 2008.

This free content was digitised by double rekeying. All rights reserved.

'Clerkenwell Close area: Middlesex House of Detention site, and other buildings', in Survey of London: Volume 46, South and East Clerkenwell, ed. Philip Temple (London, 2008), British History Online https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vol46/pp54-71 [accessed 6 May 2025].

'Clerkenwell Close area: Middlesex House of Detention site, and other buildings', in Survey of London: Volume 46, South and East Clerkenwell. Edited by Philip Temple (London, 2008), British History Online, accessed May 6, 2025, https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vol46/pp54-71.

"Clerkenwell Close area: Middlesex House of Detention site, and other buildings". Survey of London: Volume 46, South and East Clerkenwell. Ed. Philip Temple (London, 2008), British History Online. Web. 6 May 2025. https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vol46/pp54-71.

In this section

Middlesex House of Detention site

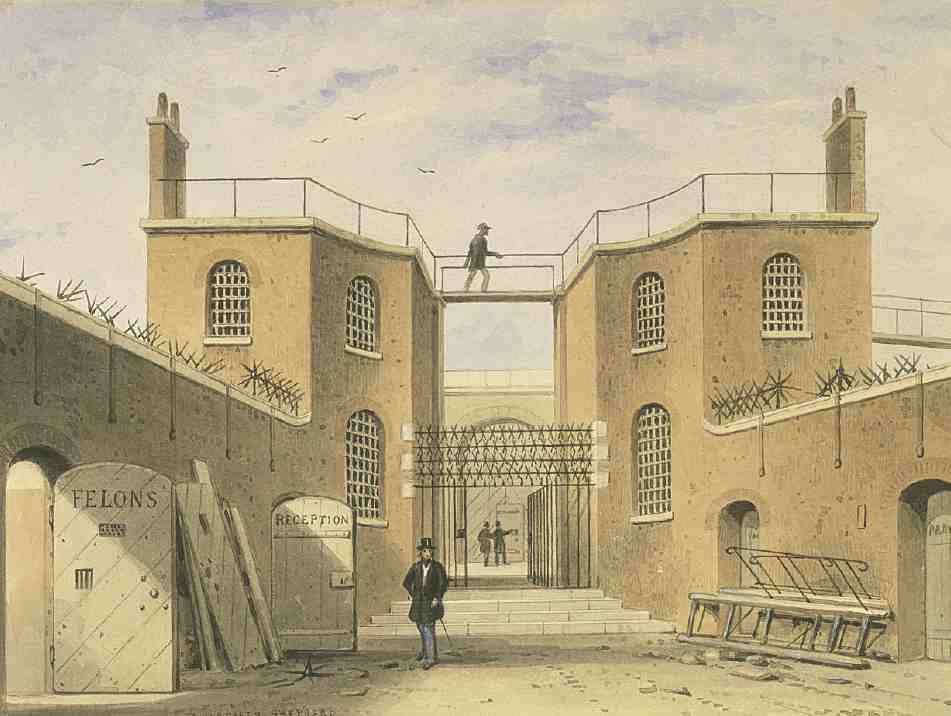

43. The New Prison (1816–18). The turnkeys' passage, looking south towards the main gates, c. 1840

The two-and-a-half-acre site described here has a long history of institutional use, famously as the site of the Middlesex House of Detention, the scene of the 'Clerkenwell Explosion' set off by Irish nationalists in 1867. Most of the site is occupied by the late Victorian buildings of the former Hugh Myddelton School, one of the largest board schools to be built in London, latterly a further education college and now converted to offices and apartments.

In medieval times this land was a corner of St Mary's Close, the nunnery field purchased after the Dissolution by Sir Thomas Seckford, Master of the Court of Requests. When Seckford died in 1587 he left the greater part of the property to endow an almshouse in Suffolk (see Chapter II), but excluded a house in the north-west corner of the field, with a 'Great Orchard' and gardens, which he left to his male heirs to become the family's London home, or 'Seckfordes Seate'. In the event this did not happen, and by the early 1600s the site had come into the ownership of the Bedingfield family. (fn. 1)

Bridewell, workhouse and New Prison, 1615–c. 1845

In 1615 the Bedingfield property was acquired by the Middlesex Justices of the Peace for a new county prison. This was originally to have been built beside Hicks' Hall, the new sessions house in St John Street (see page 206), but the site there was too restricted. By the end of the year a 'house of correction' had been erected on one of the former Bedingfield garden plots. This 'New Prison', or Clerkenwell Bridewell, took the overspill from the City prisons. (fn. 2) It was an L-shaped block, partially enclosing a yard (Ill. 9). (fn. 3) A passage leading to it from Clerkenwell Green became known as New Prison Walk (now St James's Walk), and the path leading north (now the upper end of Clerkenwell Close) Bridewell Walk.

In 1663–4 a 'great Building' of quadrangular form was erected on the north side of the Bridewell as a workhouse for a union or 'corporation' of Middlesex parishes. Its governors had wanted £18,000 to build and furnish this 'Corporation Workhouse' for 600 able-bodied and 100 aged and blind paupers, but the plan seems to have been reduced in the undertaking. As it was, more than half the inmates died in the plague of 1665, and, unable to generate sufficient income, the workhouse was defunct by 1675. (fn. 4)

In 1679 the Bridewell burnt down, and soon after the prison was moved into part of the disused workhouse. (fn. 5) The remainder, the greater part of the building, was leased in 1685 to Sir Thomas Rowe, JP, as a county school for poor orphans. This pioneering venture provided scholarly and religious instruction and practical training, but failed to survive Rowe's death in 1696. By 1700 the former school premises had been let to Quakers as an almshouse– cum–workhouse and orphans' school, which became known as the Quaker Workhouse. (fn. 6)

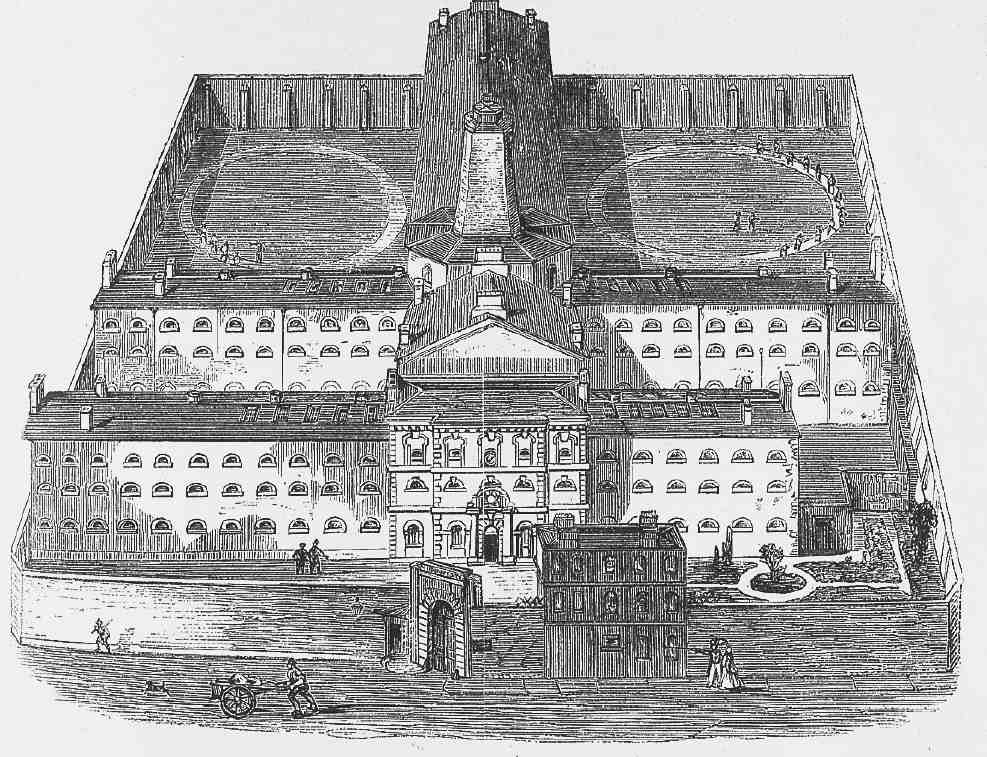

44. Middlesex House of Detention. Perspective view, c. 1862

By 1685 a second county prison had been built to the south of the workhouse and Bridewell. A 'house of detention' for those awaiting trial who could no longer be accommodated at Newgate, this too was called the New Prison. (fn. 7) It was considerably enlarged and rebuilt in 1774–5 to designs by Thomas Rogers, the county surveyor. (fn. 8)

East of the workhouse and prisons, the remnant of Thomas Seckford's orchard had by the 1740s, perhaps drawing on the success of the nearby London Spaw and New Tunbridge Wells, become a pleasure ground called the Mulberry Garden. The proprietor, William Body, supplied food and drink, musical entertainments, fireworks, and other diversions. (fn. 9) It is not known for how long the garden flourished, but it was used from about 1800 as an exercise ground by the local militia, the Clerkenwell Association or Clerkenwell Volunteers. (fn. 10)

The prison and workhouse buildings remained until the early 1800s, by which time the dilapidated, makeshift Bridewell had been superseded by a new Middlesex House of Correction at Coldbath Fields, and the workhouse had closed. Some of the buildings were then taken down and, war with France intensifying, both sites were appropriated by the Volunteers as an adjunct to the Mulberry Garden, with drill and exercise yards and a barracks. (fn. 11)

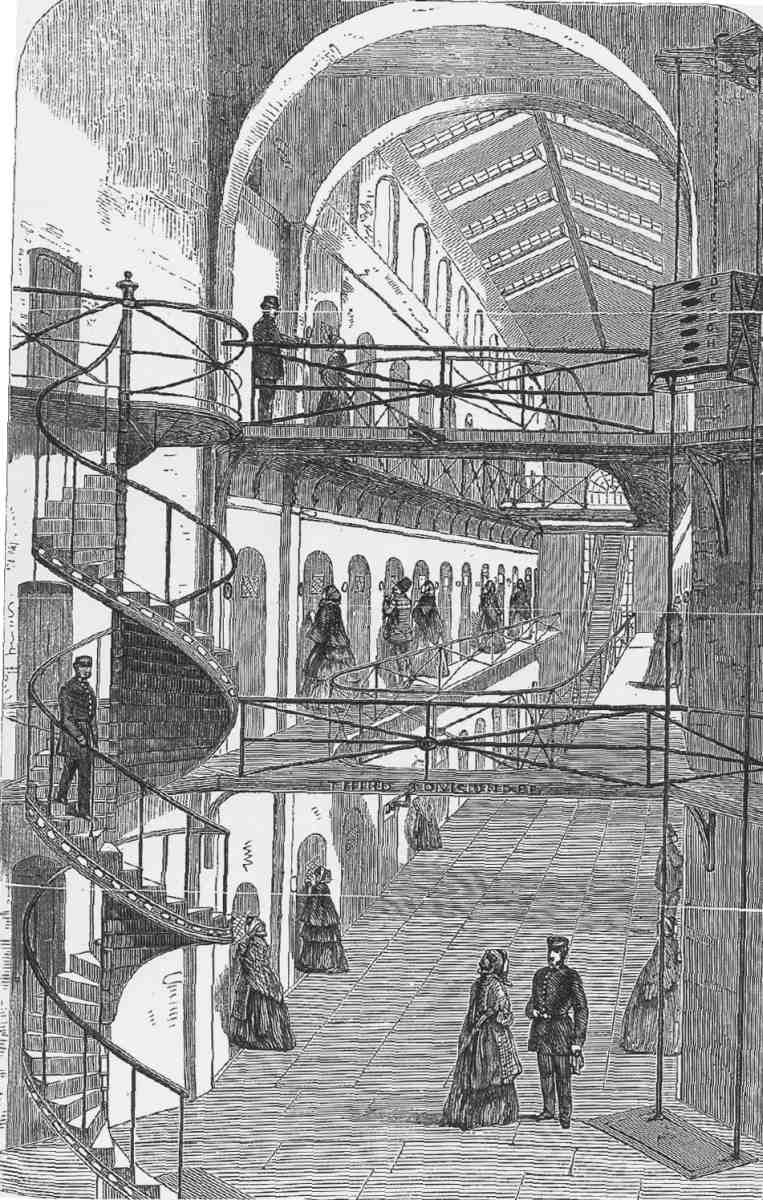

45. View along north wing from Central Hall, c. 1862

46. Basement of central octagon, retained beneath the Hugh Myddelton School, in 1991

47. Aftermath of the Fenian explosion in Corporation Row, December 1867

By January 1816, with war over, the county had decided to rebuild the New Prison on a much larger scale by extending it over the Mulberry Garden, Bridewell and workhouse sites, as well as those of adjacent houses in Bridewell Walk, Short's Buildings and St James's Walk. A plan had been drawn up by William Wickings, the county surveyor, which incorporated existing fabric at the south end, the proposed buildings and walled yards being arranged into twelve groups for six classes each of male and female inmates. Wickings resigned in May before work began, and the final plans were prepared and construction overseen by the architect Samuel Ware, who had been lending assistance as a member of the prison rebuilding committee (Ill. 43). The building contract was won by Robert Streather of Cambridge Heath Road, Bethnal Green, at a price of £18,799; this included a new boundary wall, large parts of which survive today, particularly on the south and west. Work was completed in 1818. (fn. 12)

Middlesex House of Detention, c. 1845–86

By the 1840s the New Prison had become overcrowded and outmoded. In some places there were 30 or 40 prisoners to a room, lines on the floor demarcating the areas for particular classes of inmate. (fn. 13) A new short-stay prison, the Middlesex House of Detention, was designed for the site by William Moseley, the county surveyor, and erected in 1846–7; Samuel Grimsdell was the contractor. (fn. 14)

The new buildings were strongly influenced by the recently completed Pentonville Prison, designed on the 'separate' system. The long wings of single cells, galleries, and the lofty octagonal central hall at the intersection of the male wings all followed the Pentonville pattern, though here in a 'rougher, less expensive' style of architecture (Ills 44–46, 48). (fn. 15) As at Pentonville, each cell had its own WC and basin, but only one small window, high in the end wall. A ventilation and heating system was designed by Moseley in collaboration with Messrs Haden of Trowbridge, who had been responsible for that at Pentonville. Fresh air was heated in the basement, circulated to the cells, then taken off in flues and expelled through a funnel above the central hall.

Moseley's plan was basically cruciform, with the three northern wings given over to male prisoners (Ill. 44). At the foot of the wider south arm of the cross, which housed offices, staff rooms, the chapel and other parts common to both sexes, stood a transverse wing for female prisoners. Most of the reception cells, as well as the examining rooms, baths and fumigating rooms through which all new prisoners passed before being distributed to the main wings, were situated in the basement. (Some of these apartments survived the demolition of the prison and were incorporated in the basement of the Hugh Myddelton School—see Ill. 46) Between the wings were exercise yards, where the prisoners walked in circles, and against the south wall, near the gates, were an entrance lodge and residences for the governor and matron. A new boundary wall was built on the east side, but elsewhere Streather's wall of 1816–18 was retained. (fn. 16)

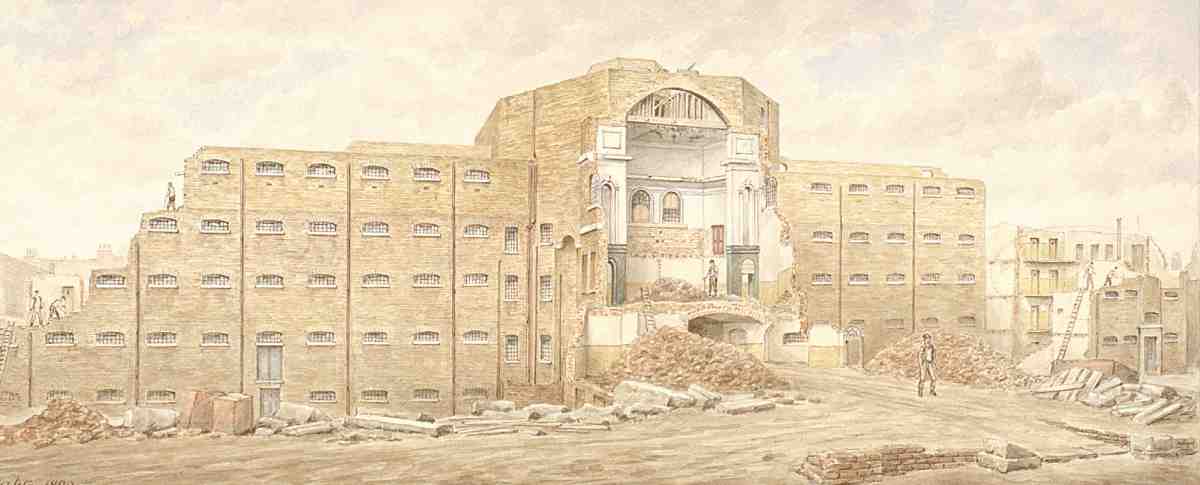

48. Demolition of the House of Detention in 1890

Intended largely for those awaiting trial for petty crime, the House of Detention was not as fearsome as the longterm correctional prisons. Communication between prisoners was forbidden, but they were allowed to wear their own clothes, and food could be brought in by friends and relatives, as could work materials for those who wished to carry on their outside occupations. (fn. 17)

The female wing was extended with more cells at the western end in 1853–4, designed by the new county surveyor Frederick Pownall. In 1865–7 Pownall also added an extra storey of cells to each of the three male wings, and at the same time built a house for the chief warder at the south-west corner of the boundary wall. Apart from the wall, this three-storey stuccoed house is the only part of the prison to survive above ground today. (fn. 18)

In December 1867 Fenian agitators used a barrel of gunpowder to blow up some 60ft or more of the north perimeter wall in a failed attempt to free two compatriots. Six civilians were killed and some fifty injured, and most of the houses opposite in Corporation Lane (now Row) were damaged beyond repair (Ill. 47). (fn. 19)

The last twenty years of the prison's existence saw further expansion and enlargements to maintain separation between prisoners and improve security. In 1871 the authorities bought the houses on the west side of Woodbridge Street—which were only six feet from the prison wall—from the Seckford Trustees, extending the boundary wall along the site and building an additional male cell block and a detached infirmary. (fn. 20)

The prison, closed in 1886, (fn. 21) was replaced in the early 1890s by the Hugh Myddelton School.

Former Hugh Myddelton School, Sans Walk

Now converted to flats and offices, the former Hugh Myddelton School comprises an important group of lateVictorian board school buildings: a main 'triple decker' block on a large scale, resplendent with buff terracotta facing; and a series of one-and two-storey special-purpose centres ranged about the perimeter of the site (Ills 49, 50). Another of these satellite buildings, originally a deaf-anddumb school, was rebuilt on a larger scale after the Second World War as the Rosemary School for infants, fronting Woodbridge Street.

The school was ceremonially opened on 13 December 1893 by the Prince of Wales. This was the first time that the School Board for London had been accorded the distinction of a royal opening for one of its establishments, an honour commensurate with the school's status as the biggest and most expensive yet built by the board, but also intended, no doubt, as an act of public exorcism of the site, formerly occupied by a state prison. Redevelopment had not entirely obliterated the physical presence of the old building: the school was in part erected on the old basement, where rows of cells were left intact, and the playground wall was in large part the prison wall, albeit reduced in height and punctured by new entrance gates. In his address, the chairman of the board called on the Prince to dedicate the site to 'higher and nobler ends' than those of the past. With the same ideals in mind, the school was named not after the street in which it stood, the usual practice of the board, but after the seventeenth-century creator of the New River—a name with a strong local association and connotations of purity, public health and the spirit of improvement. (fn. 22)

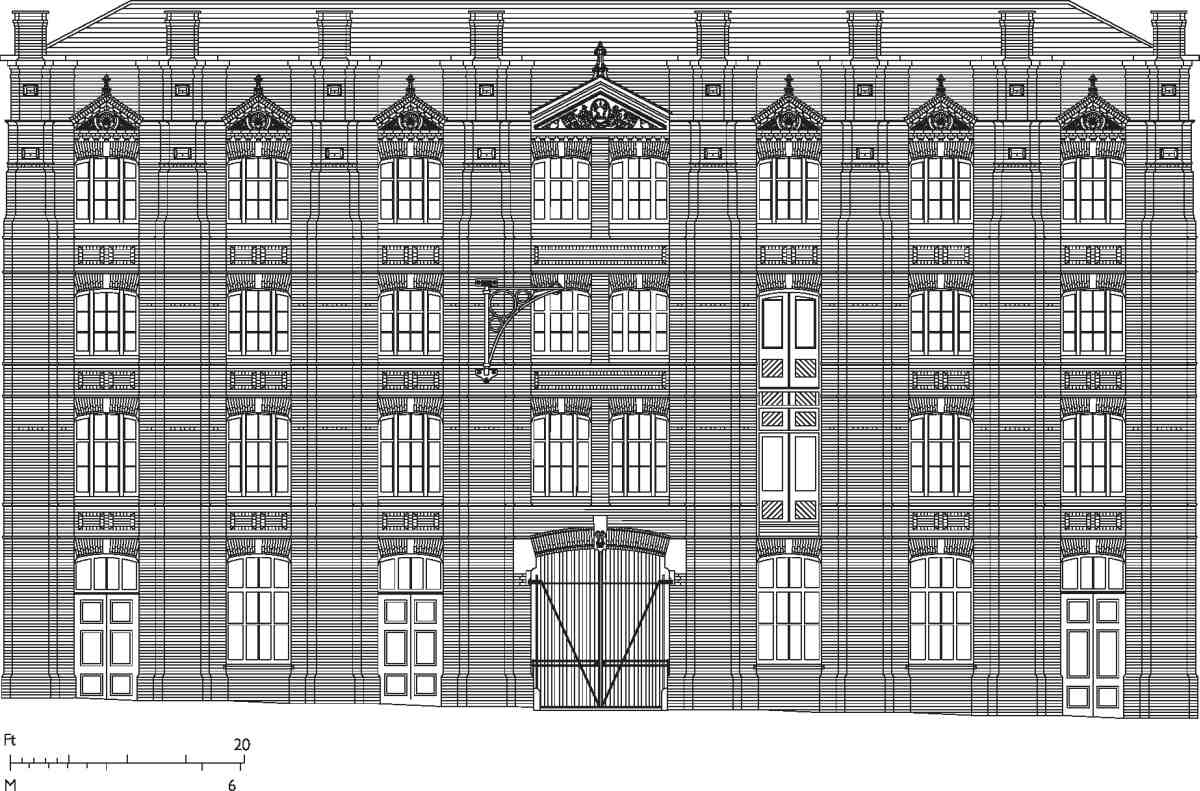

49. The former Hugh Myddelton School in 2004; T. J. Bailey, architect, 1891–3

On the closure in 1885–6 of the two Clerkenwell prisons, Coldbath Fields and the smaller House of Detention, the School Board obtained approval from the government Education Department for a new school on one or other of these sites. In neither case did the board have its eye on more than a portion of the ground, however. (fn. 23) In 1887 the entire site of Coldbath Fields Prison was acquired by the Post Office; the House of Detention was bought by the School Board in 1888, for £20,000. This obviated the need for ground in Northampton Road, for which compulsory purchase powers had already been included in a Bill then going through Parliament. At about two-and-a-half acres the ground was larger than needed for the 2,000– pupil school proposed, and it was only as a result of the machinations of William Hazel, a builder and estate agent in the Old Kent Road, that the board came to acquire it all. (fn. 24) Hazel originally negotiated the purchase of the site from the Home Office for model dwellings, ostensibly on behalf of a philanthropic syndicate which was to have let just a portion to the School Board. Subsequently, however, he upset the Home Office by putting himself forward as the board's agent for buying the whole site, intending that the surplus ground should be sold on to him personally. In the end the board, no doubt to speed up the transaction and secure a site at the favourable price negotiated by Hazel, offered to buy the lot with a proviso that any surplus would be sold for low-rent dwellings. (fn. 25)

Having acquired the ground, the board evidently cast about for ideas to make full use of it, and in the end the question of selling part never arose. (Two small pieces of ground belonging to the site, but outside the prison walls, were subsequently conveyed to the parish and added to the public way in Sans Walk and Rosoman Street.) (fn. 26) It was proposed at one time to use a wing of the prison as a temporary 'industrial school' for truants. (fn. 27) A wing was used initially as a central depot for school furniture, and for a while the board intended to erect a new Stores Department building on the site. (fn. 28) In the event, a new combined store for furniture, stationery and other supplies was built in Clerkenwell Close opposite the Hugh Myddelton School (see page 64). Late in 1890 the prison was largely razed (Ill. 48), leaving just the boundary wall, the governor's house, warders' lodges and part of the basement intact. (fn. 29)

Mindful of the history of the site, the board put up a commemorative plaque inside the wall between the northern gateways, at the point where the 1867 Fenian bombing had occurred—the start of what was intended to be an on-going programme to record important historical associations of board school sites. Some local ratepayers, however, wanted the wall itself demolished and replaced by a railing, probably to dispel any lingering sense of a jail. Considerations of cost (and the likely nuisance from playground noise) prevailed, however. (fn. 30)

The main building, designed by the board's architect T. J. Bailey, was erected in 1891–3 by J. Bull, Sons & Co. Ltd of Southampton, opening in August 1893. (fn. 31) It is built of yellow stock brick, with red-brick dressings, a facing of cream or buff terracotta largely confined to the upper floors, and red tiled roofs. The main, south range, facing Sans Walk, is flanked by massive towers with high pavilion roofs, the northern range by small polygonal staircase towers with ogee domes (Ill. 49).

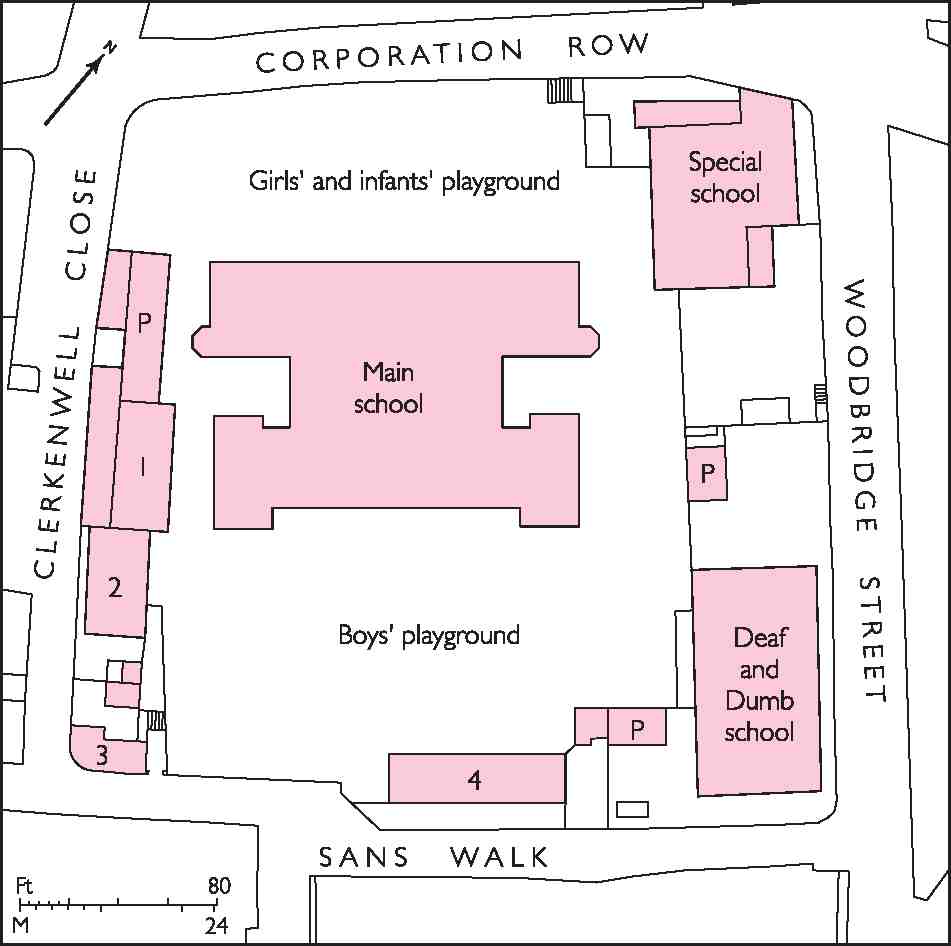

50. Hugh Myddelton School, site plan in the 1920s showing satellite buildings, including: (1) metal workroom over covered playshed; (2) cookery & laundry centre; (3) schoolkeeper's house; (4) manual training centre. 'P' denotes covered playsheds

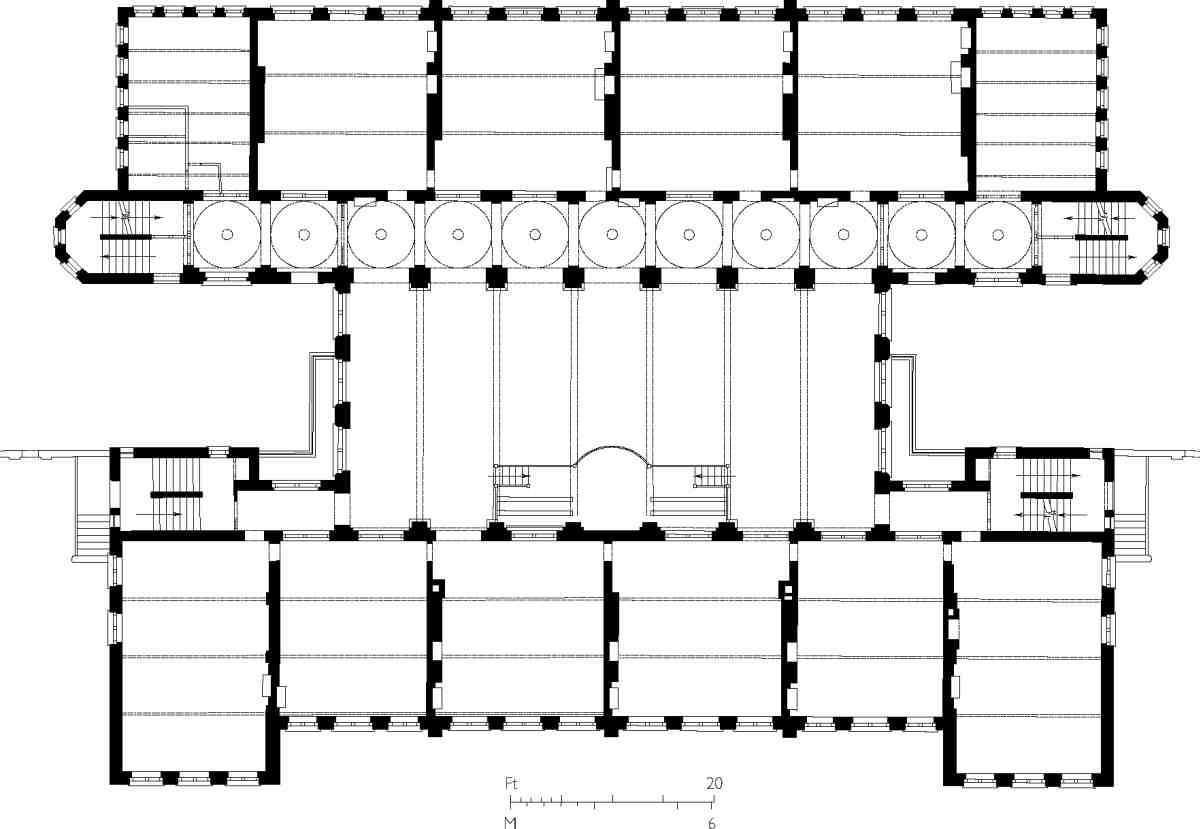

51. Hugh Myddelton School, original ground plan

52. Hugh Myddelton School. Girls' barbell drill, 1907

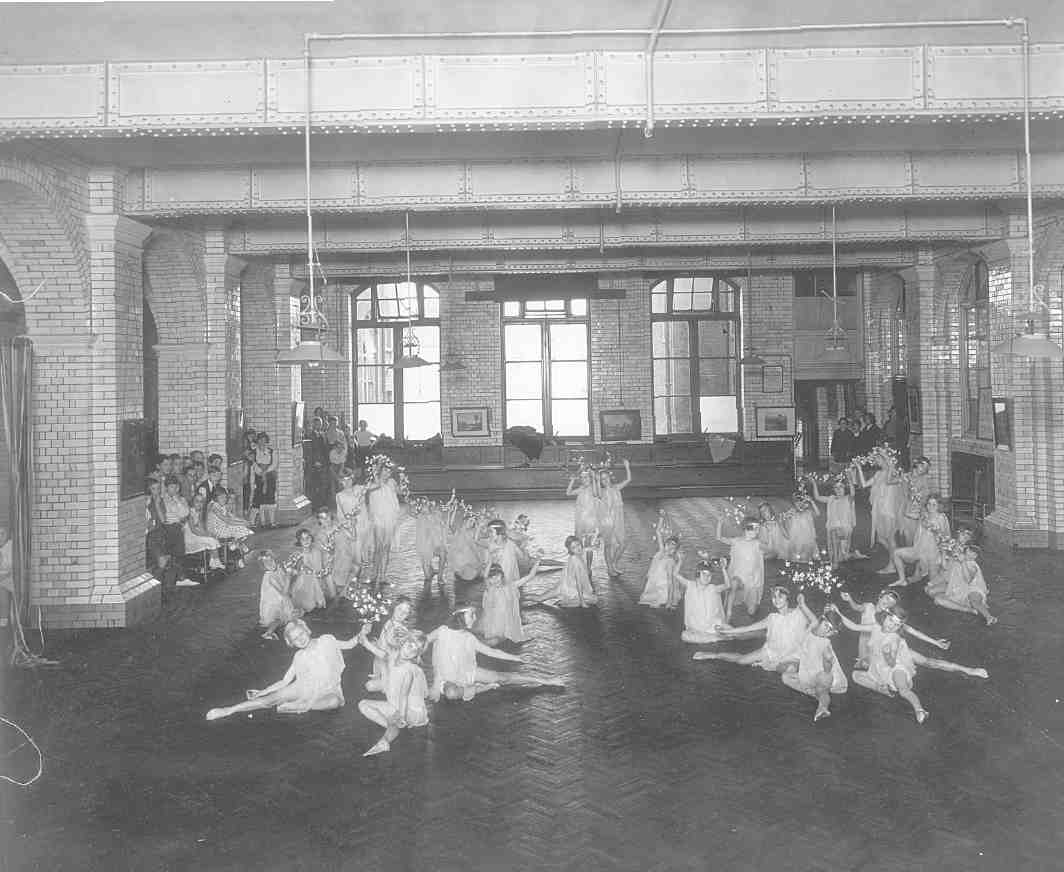

53. Girls' (second-floor) Hall, 1935: 'classical dancing'

Doubtless for reasons of economy, the building was partly erected on the prison foundations. Its alignment follows that of the central octagon of the prison and the east and west wings, which also dictated the width of the assembly halls. Otherwise, the plan is characteristic of the larger and costlier late board schools, with a single large assembly hall on each of three floors as well as individual classrooms, the original accommodation being for 800 infants and 600 each of girls and boys (Ills 51, 53). Additional classrooms were provided on further floors in the end towers of the north and south ranges.

The former boys' hall, on the second floor, is doubleheight and was designed to be used as the school gymnasium. It has a mansard roof carried on iron trusses (with metal loops for attaching climbing ropes), and is lit by large windows and skylights. The hall piers are faced with dark-green glazed brick, which was used to dado level throughout the building generally.

54. Deaf-and-dumb school, 1908

55. The Rosemary School newly completed. London County Council Architect's Department, 1948–9. Demolished

The special-purpose centres comprised a series of separate one- and two-storey buildings (Ill. 50). Originally, the board intended that there should be a deaf-and-dumb school, a blind school, a cookery and laundry centre for the girls, and also a swimming-pool. The first of these, for 144 pupils (Ill. 54) opened before the main school, in May 1892; it was badly damaged by bombing in the Second World War. In the event the proposed blind school was not built, though one was provided at some distance, in Thornhill Road, Islington. The pool, too, failed to materialize, and when the idea was revived some years later it was quashed by the Education Department (which had originally approved the scheme). The cookery and laundry centre was opened at the same time as the main building. At first, a room was set aside in the main school for woodwork instruction, and in 1895 a separate boys' manual training (woodwork) centre, with a chemistry laboratory above, was built adjacent to the cookery and laundry centre. The contractor here was C. Miskin of St Alban's. Stylistically, the earlier of these special centres harmonize with the main building, but are essentially domestic in scale and treatment, and have no terracotta facing. A plain, single-storey metalwork centre was added by the London County Council in 1913. (fn. 32)

In 1891–2, while construction of the school was still in progress, the board directed its attention to the problem of educating mentally and physically handicapped children. Three 'schools for Special Instruction' were projected initially, as an experiment, one for the Hugh Myddelton site, the others in Lambeth and Whitechapel. (fn. 33) The Clerkenwell special school, in the north-east corner of the site, was built on a separate contract, by N. Lidstone of Blackstock Road, opening in August 1895. A single–storey building, with an extra-wide corridor to allow ease of movement for disabled children, it was designed for 150 pupils in classes of 30 each—about half the size of classes for able children. It closed as a special school in 1933. (fn. 34)

Apart from the cut-down perimeter wall, the only relic of the old prison to survive above ground is the chief warder's lodge of the 1860s at the south-west corner of the site, which was used as the schoolkeeper's house. Plans to replace it in 1939 were apparently abandoned with the outbreak of war. (fn. 35) The prison governor's house was used by the School Board for a while for storage. Consideration was given to adapting it as a temporary special school in early 1892 and it was probably pulled down soon afterwards. The other warders' lodges, which stood to the east of the chief warder's, were also demolished some time in the early 1890s. (fn. 36)

The Hugh Myddelton School became something of a showpiece for the School Board, and a year after it opened a disapproving government inspector complained that the number of visitors was interfering with lessons. (fn. 37) He was also keen to put a stop to the holding of exhibitions in term time. These included the display (in the boys' hall) of more than sixty designs for a school, entries in a competition held by the board in 1893 (with John Macvicar Anderson as assessor) to see if outside architects could come up with any 'fresh ideas' in planning. None were forthcoming. (fn. 38)

Following the closure of the Hugh Myddelton School in 1971, the premises became part of the Kingsway Princeton Further Education College. In 1999 the former school was sold to Persimmon Homes and converted into flats and offices, marketed under the name '1892', the date which appears on the School Board's tablet on the main building. It is now called Kingsway Place. (fn. 39)

The bandleader Geraldo (Gerald Walcan-Bright, 1904–74) was a pupil at the Hugh Myddelton School, returning on occasion in later life to address and entertain the children.

56. Peabody Estate, Pear Tree Court, view from west side of internal courtyard, 1994

Rosemary School, Woodbridge Street (demolished)

Occupying the site of the Hugh Myddelton deaf–and–dumb school, which had been bombed in the war, the Rosemary infants' school was built in 1948, one of four 'lightweight' schools—steel-framed with a cladding of reinforced-concrete panels—put up by the London County Council at this time (Ill. 55). It was designed by the LCC Architect's Department under the Chief Architect, Robert Matthew, and erected by William Harbrow Ltd at a cost of £37,228. (fn. 40) The building, for 160 pupils, was traditional in planning, with classrooms ranged along a central corridor, in contrast to the 'compact' planning of LCC lightweight schools erected after 1949. (fn. 41) It was demolished at the end of 2007.

Other buildings

Peabody Estate, Pear Tree Court

A characteristic group of tall, severe artisans' dwellings, this was one of six such estates built by the Peabody Trust in the late 1870s and 80s on sites cleared by the Metropolitan Board of Works as part of a London-wide scheme of improvements initiated in 1877 under the terms of the first 'Cross' Act, of 1875. (fn. 42)

By the time of the Act the scarcity of cheap ground had virtually halted the Peabody building campaign begun in the 1860s. When the first of the MBW's improvement sites under the Act, at Whitechapel, failed to let or sell at auction, the trustees made a 'take it or leave it' offer of about £120,000 for six of the eight sites—a fraction of the estimated market value—stressing that the offer was 'solely from considerations of public utility'. Despite the heavy loss to ratepayers, the board felt obliged to accept, in effect providing the Trust with an indirect form of public subsidy. To help meet construction costs, the trustees also arranged a £300,000 Treasury loan. (fn. 43)

The houses in the Pear Tree Court area had been condemned as unfit for habitation by the local Medical Officer of Health, Dr J. W. Griffith, in 1875. Dilapidated and insanitary though they were, many had a picturesque quality, including a brick-and-timber group jutting out into the Close, removed to widen the roadway (Ill. 12). (fn. 44)

As built, the estate occupies a much larger area than at first envisaged. Originally, the improvement scheme was confined to the courts and alleys on the north-west side of the Close—in and around Cromwell Place, Pear Tree Court and Yates's Rents—it being understood that the adjoining land to the west fronting what is now the northern half of Farringdon Lane, which had been cleared for work on the Metropolitan Railway's 'widened lines', would in time be built up with tall warehouses like that already erected for John Greenwood & Sons (No. 34 Farringdon Lane, see page 375). The four-storey dwellings intended would thus have been hemmed in to the west by commercial buildings.

The Farringdon Lane site was owned by one of the Pear Tree Court landlords, John Earley Cook, and it was he who suggested to the MBW and the Home Office that taller, longer blocks could be built across his land, improving light and ventilation, and access as well. Cook argued that these larger blocks could also accommodate workingclass residents being displaced from another MBW improvement at Gray's Inn Road, leaving that site free for more lucrative commercial buildings. And so the board acquired Cook's land, and passed it with the original improvement area to the Peabody Trust in 1882. (fn. 45)

Pear Tree Court was the last of the six MBW sites purchased by the Trust to be developed. Construction of the eleven five-storey blocks was begun by William Cubitt & Co. in August 1883, and had been finished by the summer of 1884, the buildings being fully occupied by the end of the year. (fn. 46) Peabody dwellings were aimed at the 'respectable' labouring-classes, and so few of the new residents were of the same class as those displaced for the development. (fn. 47)

In its layout the estate follows the Peabody architect Henry Darbishire's usual preference for rectilinear planning, with eight of the blocks (A—H) arranged in a square around a central court on the west side of the Close, the other three (J—L) situated at its northern end, where it abuts Robert's Place (Ill. 5). (fn. 48) By this period Darbishire had devised a standard unit of five 'associated' flats (i.e., having shared lavatories and sculleries) off a central staircase, which could be repeated within a block as required. (fn. 49) At Pear Tree Court blocks A—H are of this type, the others being modifications of the standard pattern to fit the more awkward areas of the site. Elevations are of stock and white Suffolk brick, in the Trust's customary barrack-like style (Ill. 56).

The improvement extended to the surrounding streets, and included an extension of Clerkenwell Close northwards to meet Roberts Place, where a wall was removed and steps constructed for pedestrian access to Bowling Green Lane, where the ground level is higher. All the paving and sewerage work was carried out for the MBW by John Mowlem & Co. (fn. 50)

Blocks G and H, next to Farringdon Lane, were badly damaged and tenants killed during an air-raid in December 1940. Block G was later cleared and replaced by a row of two-storey dwellings, Nos 1–5 Peabody Terrace. (fn. 51) An air-raid shelter in the central courtyard was removed in 1985 as part of an improvement scheme. (fn. 52)

Clerkenwell Close

For Nos 1–5 and 8–13, see page 107.

No. 6

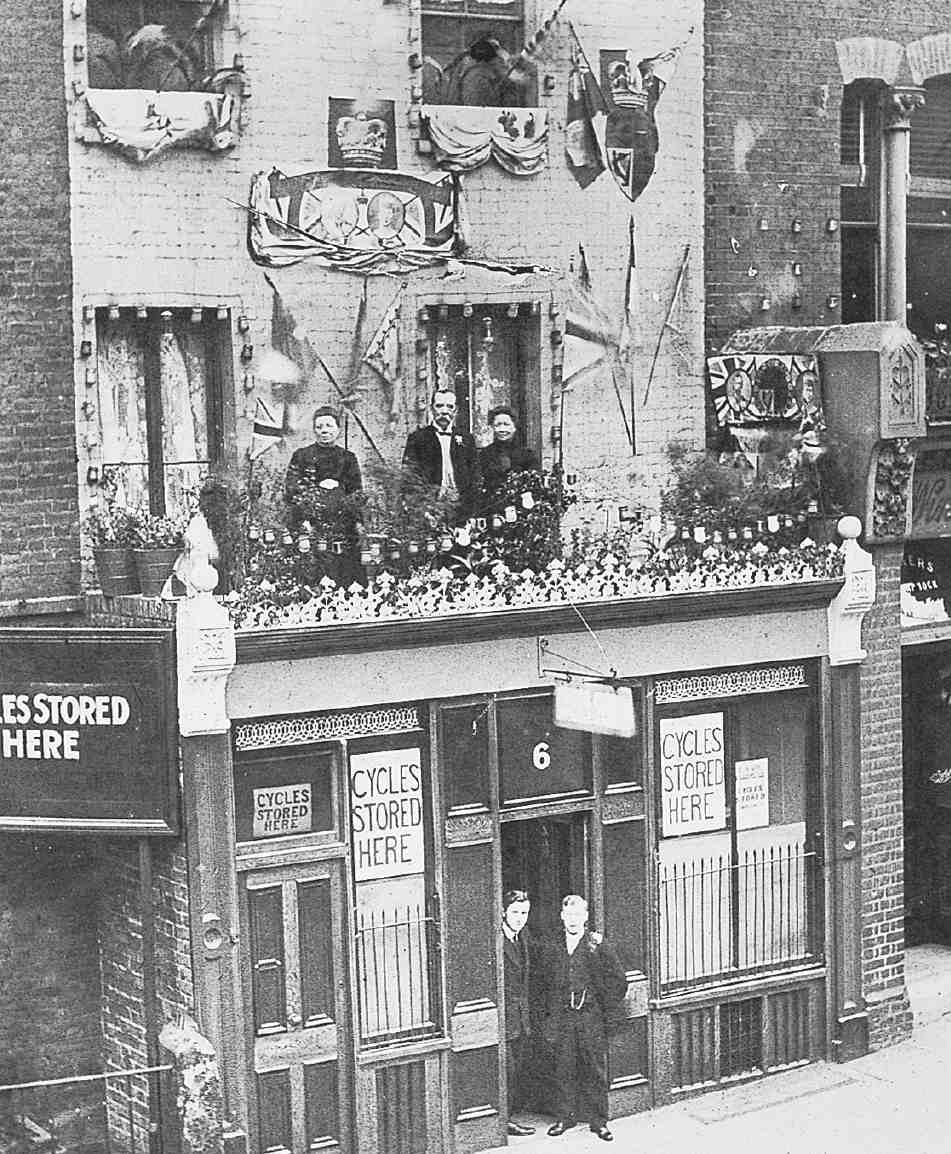

This was one of a row of three plain brick houses (with Nos 4 and 5, now demolished), erected in the early nineteenth century, perhaps as late as the 1830s; the shopfront, with iron cresting above the facia, was built out over the forecourt in 1884. (fn. 53) From 1896 until 2000 it was occupied by the Oliver family, dealers in cycles and later auto-spares (Ill. 57). (fn. 54)

57. No. 6 Clerkenwell Close, probably in 1911, at the accession or coronation of George V and Queen Mary

No. 7, the Three Kings

A public house has occupied this site since at least the eighteenth century, when it was known as the Three Johns, then (after 1774) as the Oxford Arms; the present name first occurs in 1783. (fn. 55) The old house was replaced in 1871 by the present building, designed by the architect Robert C. James of Southampton Row for Mann, Crossman & Paulin. The tiled ground-floor front was probably added during alterations in 1938. (fn. 56)

Nos 14–21

Opposite the churchyard, the west side of the Close up to the Peabody estate comprises an unremarkable group of mostly commercial buildings. Some are converted Victorian warehouses, variously restored or reconstructed, others modern pastiches.

No. 15 was built in 1898 and first occupied, until about 1910, by S. B. Cohen Ltd, pencil-makers; its frontage has been recast on several occasions since. (fn. 57) Nos 16–18 date from the early 1980s, Nos 16 and 17 replacing or replicating a factory and warehouse built in the 1880s for William Pye & Sons, printers' engineers, who also had premises to the rear at Nos 22–24 Farringdon Lane. (fn. 58) A long vault of ancient date beneath the building was used by Pyes as a print shop. (fn. 59) The firm was still based here in 1978. (fn. 60)

Nos 19 to 21 stand on part of the site of the post–Dissolution mansion, Challoner or Cromwell House. Nos 20 and 21, though much rebuilt and extended, are essentially a pair of three-storey houses (formerly Nos 14 and 15), erected in the 1820s along with a court of small dwellings called Cromwell Place (since demolished), after fire destroyed what remained of the old mansion. (fn. 61) No. 19 (Challoner House) dates from the late 1860s, when it was built for Knight & Hawkes, type-founders. (fn. 62)

58. Nos 24–26 Clerkenwell Close in 1972

Nos 24–26

At the rear of this site, set back from the roadway, is a squarish late-eighteenth-century building, still performing its original function as the main part of a public house, known then and now as the Horseshoe (Ill. 58). Three small houses and shops were built out in front during the early 1800s. (fn. 63) The easternmost pair survives today as Nos 25 and 26, for many years separate properties, now combined as a newsagents', with flats above. The stucco–fronted two-storey pub frontage at No. 24 appears to have been added in the 1840s or 50s.

59, 60. Former London School Board stores, now Clerkenwell Workshops, in 2006. T. J. Bailey, architect, 1895–7. General view and (below) overdoor pediment

Nos 27–31, Clerkenwell Workshops

Until the early 2000s these former warehouses were in use as craft workshops, but they have since been taken upmarket as offices and design studios. They were built in 1895–7 as the central stores of the London School Board, to designs by the board's architect T. J. Bailey, and are the only buildings of their type in the capital.

By 1874 the board had rationalized the supply of stationery and other equipment to its schools by establishing a stores department, which opened that December in the board's former offices in New Bridge Street. By the following Christmas the department had moved to a converted warehouse at the rear of the board's new offices on Victoria Embankment. (fn. 64) Additional stores in south London were rented by the mid-1880s. From 1889 the board was also buying its furniture wholesale, direct from contractors, for central storage and checking initially in a disused wing of the Middlesex House of Detention, which had been acquired as the site for a new school. (fn. 65) For a time a purpose-built store was planned for part of the prison site, but in 1893 the board decided instead to utilize ground on the opposite side of Clerkenwell Close, acquired in the 1880s for a proposed enlargement of Bowling Green Lane School. (fn. 66) By November 1894 the old houses there in Clerkenwell Close and Waterloo Place had been demolished, and construction by Kirk & Randall of Woolwich was under way. The stores were largely complete by December 1896, becoming fully operational the following year. (fn. 67)

Essentially the new buildings comprised two warehouses—a long, curving furniture store fronting Clerkenwell Close, and a rectangular stationery and needlework store alongside the Bowling Green Lane School playground—joined over the entrance gateway leading to a covered yard (Ill. 5). Both were brick built, with timber upper floors on steel joists encased in concrete, supported on cast-iron columns and brick piers.

Stylistically, the buildings are in the School Board manner, adapted to their purely utilitarian function. They are faced in red and yellow brick, with blue engineering brick on the ground floor, and have large segmental–headed windows, and carved pediments over the entrances to the individual departments (Ills 59, 60). The flank wall to the Bowling Green Lane school playground was given a plainer stock-brick finish.

Almost as soon as they opened the stores were insufficient, and in 1900 the board rented the former Moore's clock factory at Nos 38 and 39 adjacent. This was given over to surplus stock and returns, the main stores holding new stock only. (fn. 68) In 1904 the buildings were transferred to the London County Council's Education Department, along with the rest of the board's property and responsibilities. They later served as the LCC's general Supplies Department stores. (fn. 69) An extra storey was added to the former stationery store in 1920. (fn. 70)

61. Nos 33 (left) and 34 Clerkenwell Close in 2006

62, 63. No. 35 Clerkenwell Close. Views from north-west, in 2006, and (below) south, in 2007

In 1976 the buildings were converted to craft workshops by Urban Small Space Ltd, initially on a five-year lease from the Greater London Council. However, by the early 2000s the freehold had been sold to developers and the buildings were subsequently refitted as offices and studios. (fn. 71) The renovation, completed in July 2006 to designs by MAK Architects, included a new glass canopy over the courtyard (which was lowered to allow access to basement units) and roof extensions. (fn. 72)

Nos 33 and 34

These two adjoining late-Victorian buildings form a wedge-shaped island near the north end of the Close, where it meets Sans Walk (Ill. 61). They occupy the site of the two westernmost houses (Nos 1 and 2) on the north side of Short's Buildings, John Pescod's development of the 1740s, which were eventually combined as a public house called the Jolly Coopers.

A long rear wing, originally a separate building, was later added, giving the site its distinctive shape. (fn. 73) With the extension of the New Prison in 1818, the other houses on the north side of Short's Buildings were demolished, leaving the Jolly Coopers isolated, separated from the prison by an ill-lit passageway, complained of in Victorian times as an unpleasant route for ladies attending church, on account of 'all kinds of nuisances'. (fn. 74)

In 1897–8 the Jolly Coopers was rebuilt on a smaller scale, the new building, now No. 33, taking up only the north part of the old site. It is faced in red and stock brick, with thin pilasters and panels of moulded brick. The remainder of the old building was later demolished for warehousing (No. 34, below). (fn. 75) As part of the redevelopment the passage walls were renewed, with new plaques asserting ownership by the London County Council, replacing those of the county of Middlesex, the original prison authority. (fn. 76)

In 1920 the Jolly Coopers closed and was converted to an engineer's workshop. Since then it has continued in industrial and, more recently, commercial use. (fn. 77)

No. 34 was built in 1901, apparently as a speculation. Howell J. Williams of Bermondsey Street was the contractor. (fn. 78) A modest stock-brick block, three storeys high, with a pediment on the parapet and exposed steel girders over the windows, it was soon taken by May & Co. Ltd, ink-makers, who remained here from 1902 until the early 1930s. Later occupants have included furniture-makers and printers. (fn. 79)

No. 35

This former factory-warehouse, of stock and red wirecut brick beneath its recent greyish wash, was erected in 1871–2 for Henry and Thomas William Donkin, pattern–card makers, who had purchased the old house on the site. Their firm, Wright & Donkin, was based here until 1910. The builders were Scarlett & Elmer, of Acton. (fn. 80) Until the renumbering of Clerkenwell Close in 1903 the warehouse was known either as No. 39 (one of two in the Close), or as No. 15 in Short's Buildings or Sans Walk (so renamed in 1893 after a long-serving vestryman). (fn. 81) The nowdemolished house adjoining at No. 14 Short's Buildings/ Sans Walk was also acquired by the Donkins, in 1878. (fn. 82)

64. No. 40 Clerkenwell Close in 2006. Peter Tigg Partnership, architects, 1987–8

In 1910 No. 35 was purchased, along with No. 14 Sans Walk, by James Samuel Harrisson, a City brush-maker, as a factory and warehouse. Among various alterations, Harrisson added a lift at the rear, and rebuilt part of the external north wall. (fn. 83) The longest-running concern here was T. Smith & Co., electro-platers, from the 1930s till about 1990. (fn. 84)

65. Nos 42–46 and 47–48 Clerkenwell Close in 2006

In 1995–7 the disused plating works was converted by MRA Architects to a house and studio for the sculptor Marc Quinn. The factory floor was removed to create a double-height basement studio, living accommodation being arranged on the three upper floors. (fn. 85) Quinn moved on in 2000, and the house was later acquired by the journalist and broadcaster Janet Street-Porter, who in 2002 commissioned the architect David Adjaye to remodel and extend it (Ills 62, 63). At the back, the wall was removed and a steel-and-glass extension cantilevered out, providing terraces at first- and third-floor levels and a bedroom on the second floor. These look out over the parish churchyard. The existing mansard floor was replaced with a steel and bronzed glass 'pavilion' containing the kitchen and living-room, the glass sandblasted to give a misty effect which led Adjaye to call the building 'Fog House'. (fn. 86) The project does not seem to have been an easy one, and Janet Street-Porter was provoked by building faults into public condemnation of Adjaye, whom she dreamed of 'ritually disemboweling' before 'mopping up the storm water in my living room with his designer sweaters'. (fn. 87)

East of No. 35 is Priory House, No. 3 Sans Walk, a mid-1990s block of sheltered accommodation for the elderly, designed by Levitt Bernstein Associates for the Mercers' Company. (fn. 88)

No. 40

Designed by the Peter Tigg Partnership, this office building—'gloriously illiterate in the Docklands Post-Modern style' (fn. 89) —caused something of a furore at the time of its construction in 1987–8, when it was claimed that permission had not been given for the facing materials: yellow brick, reflective glass, and silver-grey panels (Ill. 64). Islington's planners later admitted that a mistake had been made in passing the design, which replaced a more conventional one for a gabled brick building originally submitted for the site by a different architect and developer. (fn. 90) The building (then Nos 36–41) originally bore the name Observatory prominently on the front, but this has now been removed or covered up, while the silver-grey panels have been replaced with blue-green. (fn. 91)

Nos 42–46

This mid-1980s brick office building replicates more or less in facsimile the row of artisans' cottages with attic window lights erected here by James Carr in the 1790s (Ills 65, 14). The architects were Daniel Watney Douglas Young. (fn. 92)

Nos 47 and 48

These are the only two surviving houses from James Carr's terrace of six built in 1792–4 as Newcastle Place. Adjoining the parish church, these were the biggest houses built by Carr, and the centrepiece of his little estate. Once home to merchants and watchmakers, by the mid–twentieth century they were in multiple occupation by small businesses, such as costume jewellery makers and printing-materials manufacturers. (fn. 93)

By the late 1950s or early 60s the four southernmost houses of the row (Nos 49–52) had been demolished in anticipation of a proposed expanded open space around St James's Church and Clerkenwell Green (see page 95). Eventually the two surviving houses were acquired and restored by the council, at considerable expense. So bad was their condition that most of the outer walls had to be demolished and rebuilt in facsimile, using reclaimed stocks, which resulted in their listed status being removed (Ill. 65). The contractor, W. J. Fayers, found evidence of jerry-building, the original party wall being bonded only at random to the façades. Further restoration and conversion was undertaken in 1985–7 by Hunt Thompson Architects for a housing trust, part of a scheme which included the demolition of more Carr houses behind, at Nos 1 and 2 Newcastle Row, to make way for a new housing block (No. 1 Newcastle Row). (fn. 94)

Nos 53 and 54

Like the Crown public house and adjoining buildings on the corner of Clerkenwell Green, these simple threestorey stock-brick houses are roughly contemporary with the reconstruction of St James's Church in 1788–92 (see Ill. 126 on page 113). For most of their history they have been in use by small businesses, including in the 1840s and 50s a watch-dial painter at No. 54. From the late 1850s till the late 1870s No. 53 (then numbered 51) housed a private boys' school. (fn. 95) Both were restored in the 1980s for residential and commercial use. (fn. 96) In the basement of No. 54 are medieval stone fragments, thought to relate to the gatehouse of St Mary's nunnery. (fn. 97)

For No. 55 see page 114.

Bowling Green Lane, South Side

With fields to the north, the line formed by Bowling Green Lane and Corporation Lane (now Row) marked the northern limits of built-up London in the seventeenth century (Ill. 9). By then the north side of the lane, as its name suggests, had been given over to bowling greens, and also pasture; the south side had merely half-a-dozen or so houses and an inn, the Cherry Tree, with large gardens ranged between a burial ground and a public laystall. (fn. 98)

On the site now occupied by warehousing at Nos 16–17 was 'His Majesty's Bear Garden', then as now more generally referred to as the Hockley Hole or Hockley-in-theHole bear garden, after the nearby street on the west side of Coppice Row (now part of Ray Street). Patronized both by the beau monde and lower sorts, it became known in the later seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries for the ferocity of its entertainments—'dogs tearing bulls, bulls goring dogs, or mastiffs throttling bears', as well as gladiatorial contests between men armed with swords and daggers, such as Richard Richbell of Waterford, 'the famous and terrible Hibernian', and even between women. (fn. 99) It found its way into the literature of the period, including Butler's Hudibras (1678) and Gay's Trivia (1716) and Beggar's Opera (1728). Still in use in the 1730s, it had closed and become waste ground by 1744. (fn. 100)

66. Former Bowing Green Lane School in 2004

It was not till the 1770s and 80s that building spread over the gardens and bear-garden site as far as Coppice Row, mostly in the form of smallish houses, sheds, workshops and stables. (fn. 101) In 1830–1 part of the frontage west of the Cherry Tree was redeveloped by Richard William Roberts, gentleman, of Corporation Row, who erected seven third-rate houses and shops on Bowling Green Lane (latterly Nos 9–11 and 12–15), of which a few survive, and eight smaller, fourth-rate houses in a cul-de-sac behind, once known as 'French Yard', but thereafter as Roberts Court or Place. (fn. 102)

This domestic scale of development lasted until the 1870s. By then clearance had taken place at the western end of the street, for work on the Metropolitan Railway, and in 1872 a factory was built there, facing Farringdon Road, since demolished (Nos 62–66, see page 369). Very soon afterwards an early board school arose at the eastern end, and by 1879 a long run of tall brick warehouses had taken up most of the intermediate frontage. These 1870s buildings, since converted to other uses, still dominate the south side of the street.

No. 10, former Bowling Green Lane School

Built in 1873–5, Bowling Green Lane School was among the first London board schools in the 'Queen Anne' style with which the genre was to become so closely associated (Ill. 66). Although documentary proof is lacking, it was almost certainly designed by the School Board's architect E. R. Robson in collaboration with his friend and partner in private practice, J. J. Stevenson.

When the school was planned, the site, part of the Marquess of Northampton's estate, had been held on lease by the parish for the past two hundred years, most of it as an auxiliary burial ground and the remainder being occupied by houses and the Cherry Tree tavern. Negotiations for the purchase of the site were under way in the autumn of 1872, and the building contract (following a tender of £6,261) was made with G.S. Pritchard of Finsbury in October 1873. The school was partially opened in January 1875, the boys' department not until the following August. (fn. 103)

Although he was never on the School Board staff, Stevenson played an important role in the development of the familiar board-school style during the busy early years of Robson's tenure as architect. (fn. 104) The two men set up in private practice together in September 1871, two months after Robson's appointment. Though their first school designs, exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1873, bore both their names, it has been suggested since that their work was in fact done separately, Robson being responsible for the 'Gothic' buildings, Stevenson the 'Queen Anne'. (fn. 105) However, Stevenson's assertion that he was responsible for the 'architecture' of some early schools suggests he may have been designing elevations for Robson's plans, rather than designing schools from scratch. (fn. 106)

At Bowling Green Lane, Robson's thinking is evident in the cellular planning, avoiding corridors, which he thought extravagant. (fn. 107) He preferred inter-communicating rooms, though some shallow balconies were also provided on the first floor for access between rooms, as well as sheltering parts of the playground from rain. At the time this arrangement was considered 'compact and very convenient', (fn. 108) but by the early twentieth century it was frowned upon. Without proper corridors classrooms became ad hoc passageways, making supervision difficult. Also criticized in later years was the separation of the two ground-floor halls by the headmaster's room, which prevented their being thrown together for gatherings of the entire school. (fn. 109)

While the planning of the school was economy–minded and unremarkable, its exterior was in the van of architectural fashion, and it is here that Stevenson's hand is to be discerned. The shaped gables, narrow brick pilasters, tall chimney stacks, and the aedicular treatment of the mezzanine window on the street front, all recall his second London house, No. 8 Palace Gate, Kensington, the school's exact contemporary. (Robson was credited as joint architect of the Palace Gate house, but as with their school work this was no doubt merely a formal acknowledgement of their professional partnership.) (fn. 110)

Stevenson's influence at Bowling Green Lane did not extend to the detached schoolkeeper's house, obscurely sited against the south-west boundary wall. This was erected by Pritchard on a separate contract in 1876–7, after the Robson—Stevenson partnership had come to an end, and its red and yellow brick elevations lack any refinement of detailing. (fn. 111)

Ground to the south was acquired in the 1880s for an extension of the school, but this became unnecessary with the construction in 1891–3 of the Hugh Myddelton School on the opposite side of the Close (see above). From 1899 the Bowling Green Lane site functioned as the junior department of the larger school. (fn. 112) It closed in 1970 on the opening of a new Hugh Myddelton Primary School in Lloyd's Row (see Survey of London, volume xlvii), but the building remained in educational use for some years as an annexe to Islington Green Secondary School. In 1982 it was converted for light-industrial use and enlarged with a flat-roofed ground-floor extension on the south-east side. (fn. 113) It is now used as design studios; occupants include Zaha Hadid Architects.

No. 11

Extending over the sites formerly occupied by houses at Nos 9–11 Bowling Green Lane and 1–4 Roberts Place, this utilitarian stock-brick factory was built in 1930 for M. C. Ritchie Ltd, manufacturers of box-making and printing machinery, formerly of Farringdon Road. The architects were Rowland Plumbe & Partners. (fn. 114) The rooftop addition was part of a 1990s residential conversion of the upper floors, which included a loft-style first-floor apartment designed by the architect Spencer Fung. (fn. 115)

Roberts Place

The concrete-framed building at Nos 5–8, of c. 1962, was designed by L. Obermeister, architect, for the production and storage of books. The façade was altered in 2004 by Ian Simpson Architects Ltd, who took over the building as their London studio. (fn. 116)

Nos 12–15

Built in 1830, this short row of three-storey houses and shops is all that remains of Richard Roberts's development at Nos 9–15 and Roberts Place, and constitutes the oldest fabric in the street.

From 1880 until the early 1970s, No. 15 was the office and workshops of Thwaites & Reed, Clerkenwell's oldest clockmakers, who specialized in the manufacture and repair of large turret clocks for churches, town halls and commercial buildings. (fn. 117) They moved here from Rosoman Street. The main workshop, a two-storey building at the rear of Nos 13–15, had been built in 1865 by a previous tenant, George Terry, a builder. (fn. 118) Thwaites & Reed moved in 1974 to a new factory in East Sussex, where they remain in business. Since then No. 15 has largely been rebuilt in facsimile. (fn. 119)

67. No. 16 Bowling Green Lane in 2007

Nos 16–17

The large warehouse fronting the street, formerly numbered 16–17 but now just 16, was erected in 1877–9 for James Johnstone, proprietor of the Standard and Evening Standard newspapers. (fn. 120) Conveniently placed for the mainline termini at King's Cross and St Pancras, it was part of an improved system of production and distribution at a time of great expansion.

A lawyer by training, Johnstone had acquired the Standard, and the Morning Herald, advantageously in 1857 from their bankrupt owner. By dropping the price, increasing the number of pages and making the Standard a morning paper, he boosted sales and for a while made it a genuine challenger to The Times. Although a new Evening Herald as sister to the Morning Herald proved a failure, closing in 1865, the Evening Standard, which he launched in 1859, was an outstanding success. (fn. 121)

The Clerkenwell warehouse development coincided with the erection of new City offices in St Bride Street and Shoe Lane, and the introduction of modern printing presses and production facilities. However, Johnstone died (in October 1878) before he could enjoy the fruits of all this investment; it was under his successor, William Mudford, that daily sales first exceeded 250,000 in the mid-1880s. (fn. 122)

The warehouse is a confident piece of architecture (Ills 67, 69). Built of red and yellow brick with minimal stone dressings, the façade is a symmetrical composition with rugged full-height pilasters and steep pediments of moulded brick and terracotta over the top windows. In the central pediment a terracotta composition in high relief comprises the winged helmet of Mercury flanked by royal standards, with the rose, thistle and shamrock (Ill. 68). The large central carriageway (with the helmet motif repeated in the keystone) led to a covered yard, with coach-houses and stabling. The architect's identity is not known.

68. No. 16 Bowling Green Lane, detail of central pediment, 2007

69. No. 16 Bowling Green Lane, main elevation in 2004

In 1927 Standard Newspapers sold the premises to William Notting Ltd, who moved their printing-machinery works here from Nos 18–19 adjoining. Nottings, who obtained a new long lease from the Northampton Estate, demolished the coach-house and stables, and built a large two-storey extension over most of the courtyard. (fn. 123) They were the main occupiers until 1987. (fn. 124)

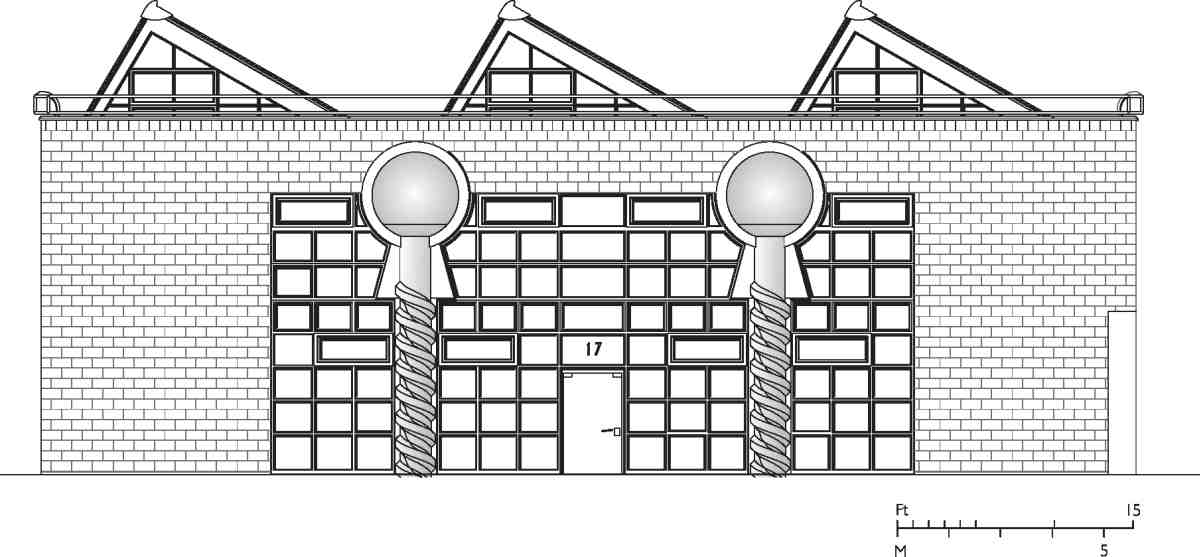

By March 1988 the site had been acquired by the architects Campbell Zogolovitch Wilkinson Gough as their new offices. The courtyard addition was given a new northlight roof, and a postmodern façade incorporating two of the practice's trademark giant 'screw' columns in pre-cast concrete (Ill. 70). The old warehouse has been let or sold, CZWG remaining in the courtyard building (No. 17). (fn. 125)

70. No. 17 Bowling Green Lane, north front in 2004. CZWG, architects, 1988

Nos 18–20

Like No. 16 immediately to the west, these warehouses were erected in 1877–9 under lease from the Northampton Estate. Though the eastern part (now Nos 18–19) has been refaced, the whole range originally shared the same pedimented stock-and-red-brick style as No. 16, and may have been by the same unknown architect.

The lessee was William Notting, manufacturer of brass-rules, presses and other printing equipment, formerly based in Type Street, Finsbury. That site being required by the Ecclesiastical Commissioners, Notting moved in 1872 to premises in Crawford Passage, but being unable to agree terms with the ground landlord there took a building lease on the vacant Bowling Green Lane site. (fn. 126)

The development comprised two warehouses either side of a staircase bay facing the street. Nottings' own premises, 'Enterprise Works', was the larger of the two (Nos 18–19). This had a small office at the front, and two single-storey workshop extensions at the back. A passage from Farringdon Road led to a small yard. (fn. 127) The other warehouse (No. 20), called 'Enterprise Buildings', seems to have been first occupied in the early 1880s by Thorburn, Bain & Co., wholesale stationers. (fn. 128)

After Nottings' move to Nos 16–17 in 1927, Nos 18–19 and 20 were occupied by a variety of firms, including the jewellers and goldsmiths Mappin & Webb. (fn. 129) The remodelling of the façade at Nos 18–19 was part of an early 1960s refurbishment by the Ruislip architects Godderson & Buckley, though their work has in turn been altered as part of a residential conversion of the upper floors in 1999. (fn. 130)