A History of the County of York East Riding: Volume 7, Holderness Wapentake, Middle and North Divisions. Originally published by Victoria County History, London, 2002.

This free content was digitised by double rekeying. All rights reserved.

K J Allison, A P Baggs, T N Cooper, C Davidson-Cragoe, J Walker, 'Holderness Wapentake: Middle and North divisions', in A History of the County of York East Riding: Volume 7, Holderness Wapentake, Middle and North Divisions, ed. G H R Kent (London, 2002), British History Online https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/vch/yorks/east/vol7/pp1-4 [accessed 19 April 2025].

K J Allison, A P Baggs, T N Cooper, C Davidson-Cragoe, J Walker, 'Holderness Wapentake: Middle and North divisions', in A History of the County of York East Riding: Volume 7, Holderness Wapentake, Middle and North Divisions. Edited by G H R Kent (London, 2002), British History Online, accessed April 19, 2025, https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/vch/yorks/east/vol7/pp1-4.

K J Allison, A P Baggs, T N Cooper, C Davidson-Cragoe, J Walker. "Holderness Wapentake: Middle and North divisions". A History of the County of York East Riding: Volume 7, Holderness Wapentake, Middle and North Divisions. Ed. G H R Kent (London, 2002), British History Online. Web. 19 April 2025. https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/vch/yorks/east/vol7/pp1-4.

HOLDERNESS WAPENTAKE (Middle and North Divisions)

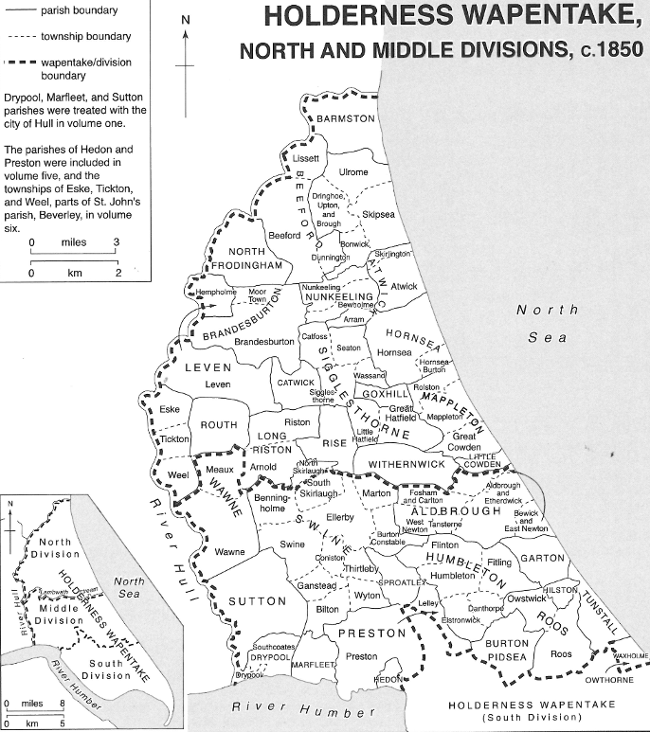

AN account of the former wapentake has been given in an earlier volume. (fn. 1) The history of the whole of South division, including Waxholme township, which was in Middle division but part of Owthorne parish, together with that of Hedon and Preston from Middle division, has similarly been dealt with elsewhere. (fn. 2) Extensions to the boundaries of the borough of Kingston upon Hull in the 19th and 20th centuries have taken in, from Middle division, the whole of Drypool and Marfleet parishes, most of Sutton on Hull, and parts of Bilton and Wawne. The history of the first three of those parishes has accordingly been treated along with that of the rest of the city of Hull. (fn. 3) Eske township, in North division, has been dealt with as part of the borough and liberties of Beverley. (fn. 4) The present volume covers the rest of Middle and North divisions.

Holderness Wapentake, North and Middle Divisions, c.1850

The North and Middle divisions shared with the other part of the wapentake an undulating plain bounded on the east by the North Sea. The western boundary of the two divisions was the river Hull and its tributaries, a stream flowing east to the sea marked the northern limit of the wapentake, and other watercourses draining west and south-west to the Hull and Humber defined its internal divisions. Much of the land lies between 10 and 20 m. above sea level, but the ground at Nunkeeling reaches 30 m. and in the Hull valley and the flat margins of the Humber estuary it scarcely exceeds sea level. Most of the area is covered with glacial deposits, chiefly boulder clay but also locally important concentrations of sand and gravel.

Alterations to the natural drainage were made by monastic houses and lay lords in the Middle Ages, and later there were piecemeal attempts to improve the area's poor drainage, but it was not until the formation of drainage boards in the later 18th century that flooding began to be controlled. The improvement finally enabled the remaining wastes to be added to the farm land, as well as causing the virtual disappearance of one of Holderness's characteristic features, its meres, permanent but fluctuating lakes of which only that at Hornsea now remains.

Several of the parishes were very large and contained a number of settlements, the largest being Swine, which in the 19th century, after earlier losses to adjoining places, contained nearly 15,000 a. divided between thirteen townships. The area also includes the smallest parish in the wapentake, Goxhill with just over 800 a. The differences may reflect landownership before the Conquest, as well as possible variations in the number of churches built by early lords on their holdings. There is no apparent explanation in the pattern of landownership which obtained in the larger parishes in the mid 11th century. Aldbrough, later of 6,400 a., thus comprised, besides Ulf's manor, sokeland belonging to Morkar's manors of Kilnsea and Easington, while Humbleton, of a similar size, was a dependency of Morkar's manors of Kilnsea and Withernsea and the archbishop of York's manor of Swine.

After the Conquest there were two chief holdings, those of the archbishop of York and the count of Aumale. The latter lordship passed to the Crown and then eventually, in the 16th century, to the Constable family of Halsham in south Holderness and Burton Constable, which later held much land in Holderness, including a compact estate of several thousand acres in and around Burton Constable. In the Middle Ages large landowners in the area included several religious bodies, notably the abbeys of Meaux and Thornton, in Lincolnshire, foundations of William le Gros, count of Aumale, and the priories of Swine, Nunkeeling, and Bridlington. The connection with Lincolnshire, evident in the holdings of Aumale tenants like the Goxhills of Sproatley, may have been reinforced by Thornton's long possession of the manors of Humbleton and Garton and its other estates in Holderness. Much of the land formerly belonging to religious bodies, as well as some otherwise held by the Crown, was sold in the 16th and 17th centuries. The Bethells, whose interest in the area resulted from their position as Crown officers, built up an extensive estate in North and Middle Holderness from the 16th century: Rise manor was leased and, in the 17th century, bought, and other purchases and acquisitions by marriage enlarged the family's holding there and in many other places. By the mid 19th century the estate in Holderness comprised almost 14,000 a., with much land in Riston and Arnold, Catfoss, Ellerby, and Leven parish, where the manor formerly belonging to Beverley minster had been bought in the 18th century. A smaller estate in Sigglesthorne and Hornsea parishes was created by another family called Constable, later the Strickland-Constables, a local gentry family who bought Wassand manor in the 16th century, and later acquired much of Seaton; by the 20th century the estate comprised some 2,000 a. in Wassand, Seaton, and Hornsea, besides Hornsea mere. The Thompsons of Scarborough, purchasers of Thornton abbey's manor of Humbleton in the 17th century, and their heirs, the Hothams, created an estate of c. 2,500 a. in that parish, while from the 18th century the Kirkbys of Hull built up another compact estate based on Roos manor which passed to their heirs, the Sykes of Sledmere. The estate around Wassand Hall remains largely intact, but sales, especially in the 20th century, have extinguished or reduced the other large holdings. The Chichester-Constables, successors to the Constables, remain as landowners in Holderness, but part of Burton Constable has lately been given to a trust to ensure the survival of the Hall and park there. The decline of the old estates has to some extent been accompanied by the creation of large farming concerns managing considerable areas with few farms.

North and Middle Holderness remains a predominantly rural area of nucleated settlement in villages and hamlets. While several of the larger villages have had some commercial pretensions, only one settlement developed into a market town, that of Hornsea, formerly belonging to St. Mary's abbey, York. The settlements of the area were usually sited on the higher ground, often on the better-drained sand and gravel deposits, although there is evidence for earlier, prehistoric lakedwelling at Ulrome. The common plan was a long street-village, sometimes with discrete ends. The number of medieval villages and hamlets has been reduced, some places, like Monkwith, in Tunstall, and Cleeton, in Skipsea, being eroded by the sea, and others, like the subsidiary settlements of Ellerby township, in Swine, being reduced to one or two farmhouses. Conversely, the opening of a railway from Hull in 1864 accelerated the development of Hornsea, both as a coastal resort and seaside suburb of Hull, besides creating the hamlet of New Ellerby close to one of the stations. Many of the other settlements also grew and changed their character in the 19th and especially the 20th century, to a great extent losing their connection with agriculture and becoming enlarged dormitory settlements of the city of Hull and the towns of Beverley, Bridlington, and Driffield. In Wawne and Bilton, in Swine, the process has gone further, and parts of those places have been taken into the city of Hull and covered with houses.

Brick is the predominant building material, but most of the churches, and some domestic and farm buildings, are of stone, either imported limestone or boulders from the fields and shore. At least one house, at Beeford, represents an earlier building tradition, being constructed of mud. The churches include one of more than local significance, the Perpendicular chapel at Skirlaugh, and at Goxhill a charming Gothick building with early Victorian fittings. Noteworthy secular buildings in the area formerly included the Norman castle at Skipsea, the head place of the lordship of Holderness, now represented by impressive earthworks. Later buildings of note include Burton Constable Hall, the seat of the Constables, lords of Holderness, a medieval house which was largely rebuilt in the 16th century, and later remodelled in Classical and Jacobean-revival styles, and Grimston Garth, in Garton, a large, Gothick summer residence built near the cliff in the 18th century. Those houses, and that of the Bethells at Rise, stand in parks, and the woods there and close to Wassand Hall in Sigglesthorne provide a welcome variety in a landscape largely cleared of its old woodlands. On a smaller scale Italianate villas were put up at Woodhall in Ellerby and at Wyton, in Swine, in the earlier 19th century, and groups of houses were built or remodelled for the middle classes at Wyton and Burton Pidsea. At Swine the village and outlying farmhouses were rebuilt by the Crown in the 1860s, and there was similar building in other places dominated by a single landowner, among them Burton Constable, Rise, Wassand, and Wawne. Hornsea's role as in part a detached suburb of Hull was reflected in the urban, even metropolitan, style of its buildings from the later 19th century, and more recent building and lay-outs there and elswhere have diluted still further local characteristics in building.

Travel between settlements was difficult before the area was drained. Some of the medieval improvements to streams seem to have been prompted primarily by the need for better communication, and the Hull's importance for transporting goods was evident from the extension of the system in the 19th century by canals, including that at Leven. The chief roads running through North and Middle Holderness were those from Beverley and Hull to Bridlington, and from Hull to Aldbrough. Stretches of those roads were improved by turnpike trusts in the 18th and 19th centuries. Other roads run through the coastal settlements between Withernsea and Bridlington, and connect that route to the inland road to Bridlington. Otherwise the area is served by minor and field roads. A railway line linking Hull and Hornsea, and serving several villages between those places, was operated from 1864 to 1965.

The chief occupation of the area was for long agriculture, which remains significant but now employs only a fraction of the population. The inadequate drainage of much of Holderness caused large areas to be left unimproved as marshland, or carrs, and moors until comparatively recently. Though waste, the unimproved grounds contributed to the local economy, providing, besides rough grazing, fish, fowl, reeds for thatching, and crops of furze, or whins, for fuel. The abundance of grazing, notably in the south of the Hull valley, and the location there of the Cistercian houses of Meaux and Swine, may have made sheep-and dairy-farming more important in the Middle Ages than later.

Evidence for changes in land use and agricultural practice in Holderness are, on the whole, poorly documented. The extension of the farmed land into the waste in the 13th century is perhaps clearest in the immediate proximity of Meaux abbey in Wawne parish, and that house's records also document the later retreat from demesne farming. The inclosure of the open fields and other commonable lands, and the sometimes related conversion of tillage to pasture, was a lengthy process. Several places dominated by one landowner, whether a religious house, as at Nunkeeling and in the hamlets of Leven parish, or a lay lord like the Constables at Burton Constable, were apparently inclosed before the mid 16th century, and piecemeal inclosures at Little Cowden, in Mappleton, and other places were also reported in 1517. The sale of former monastic and other Crown estates in the 16th and 17th centuries prompted a rash of inclosures, some initiated presumably by purchasers like the Micklethwaites at Swine, who inclosed land there in the 1650s, and the Bethells, who inclosed Rise in 1660. At Wawne Sir Joseph Ashe, member of a London mercantile family, probably inclosed, as well as instigating an ambitious drainage scheme. There is good evidence for some twenty places in North and Middle Holderness being inclosed in whole or in part in the 17th century; the areas involved cannot always be determined, but at Brandesburton and Burshill over 3,000 a. were dealt with in the 1630s. Inclosures by agreement continued into the 18th century, the second of Flinton's inclosures dating from 1752. The lengthy process was completed in the later 18th and 19th century by inclosures under Acts of Parliament, but the proportion of land left to be dealt with was almost certainly less than in other parts of the riding. Of the c. 100,000 a. comprised in the area, only some 38,000 were then inclosed by Act. That the number of smaller tenants was reduced and holdings consolidated during the process is suggested at North Frodingham, inclosed in the early 19th century: one of the c. 55 allottees and his partners then received land for many newly-purchased holdings, and later the large village had only some 20 farms. After inclosure was completed, the area developed as a major producer of cereal crops; also significant in the 20th century was the intensive rearing of pigs and poultry.

There was little employment in the area unconnected with agriculture, but one or two local tradesmen at Burton Pidsea and Marton achieved wider renown in the 19th and 20th centuries as makers of agricultural machinery. Bricks were made from the local clay in small works in several parishes, and the extraction of sand and gravel expanded from small beginnings to large-scale working in the 20th century, most notably in Catwick and Brandesburton. Occupations for those living along the coast have included fishing from Hornsea, and the removal of gravel from the sea shore. More recently seasonal work has been provided by holiday makers on the caravan sites and leisure facilities which developed after the Second World War. Some small-scale industrial and commercial concerns have also made use of the sites of former airfields at Lissett in Beeford and Catfoss, in Sigglesthorne.