A History of the County of Wiltshire: Volume 18. Originally published by Boydell & Brewer for Victoria County History, Woodbridge, 2011.

This free content was digitised by double rekeying. All rights reserved.

'Historic Parishes - Purton with Braydon', in A History of the County of Wiltshire: Volume 18, ed. Virginia Bainbridge (Woodbridge, 2011), British History Online https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/vch/wilts/vol18/244-285 [accessed 4 April 2025].

'Historic Parishes - Purton with Braydon', in A History of the County of Wiltshire: Volume 18. Edited by Virginia Bainbridge (Woodbridge, 2011), British History Online, accessed April 4, 2025, https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/vch/wilts/vol18/244-285.

"Historic Parishes - Purton with Braydon". A History of the County of Wiltshire: Volume 18. Ed. Virginia Bainbridge (Woodbridge, 2011), British History Online. Web. 4 April 2025. https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/vch/wilts/vol18/244-285.

In this section

PURTON

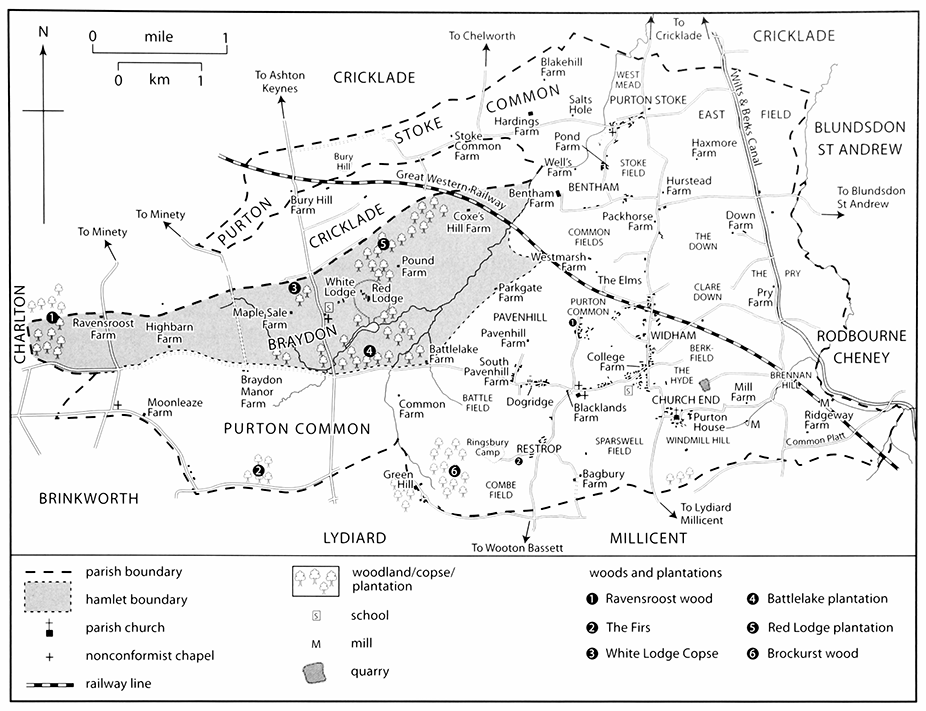

PURTON is a large parish which includes Purton village, Purton Stoke and various outlying settlements, several of which coalesced with the village as it expanded during the 20th century. (fn. 1) The village centre lies approximately 16 km. east of Malmesbury, 6 km. south of Cricklade and 7 km. north-west of Swindon town centre. The name, referring to a settlement by a pear-tree, was first recorded in 796, when Purton was described as lying to the east of Braydon forest. (fn. 2) Parts of the parish lay within the bounds of the forest, including the tithing of Braydon, formerly the Duchy woods in the central part of the ancient forest, (fn. 3) which became a separate civil parish in 1866. (fn. 4) Most aspects of Braydon's history are treated separately in the last section of this account. The other sections are concerned with the parish as it existed after 1866 and before 1984, when further changes were made to its boundary. (fn. 5)

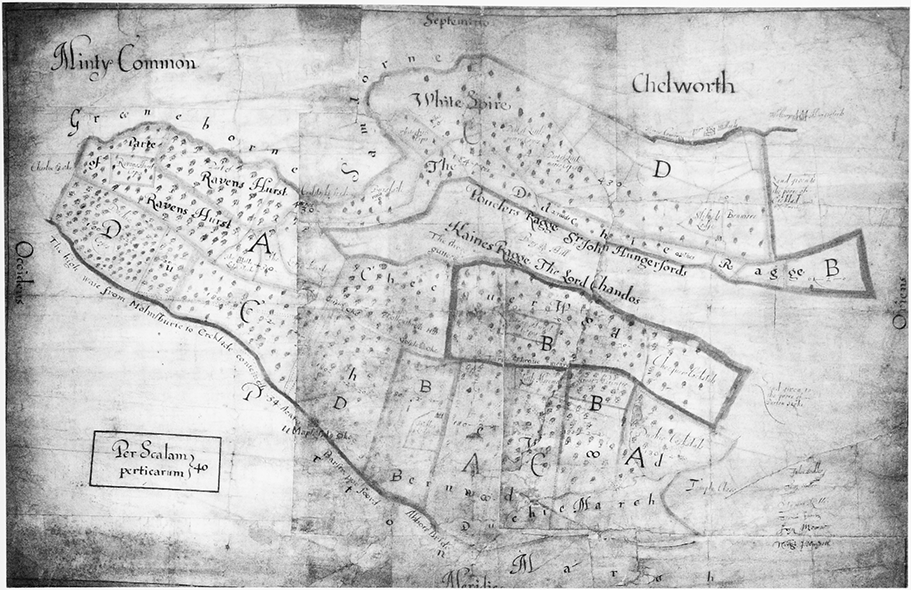

Boundaries

The parish is approximately rectangular, but with long fingers of land extending westward from the northwestern and south-western corners. (fn. 6) To the east of Purton lie Blunsdon St Andrew, and what was formerly part of Rodbourne Cheney parish and became Haydon Wick; to the north lies Cricklade St Sampson, and to the south lie Lydiard Millicent and, at the south-west corner, Brinkworth. Braydon tithing occupies much of the area between the two fingers of Purton land, and the remainder is another strip of land which belonged to Cricklade St Sampson. Purton's more northerly finger, extending westward from Purton Stoke, derives from two long narrow strips of Braydon forest called Keynes rag and Poucher's rag after heirs of Adam of Purton. (fn. 7) In 1637 the vicar of Purton successfully resisted a claim that the rags were part of Cricklade St Sampson parish. (fn. 8) In 1879 Purton covered 6,464 a. and Braydon 1,483 a., a total of 7,948 a. (fn. 9) In 1984 the intruding strip of Cricklade St Sampson land was transferred to Purton parish, and small areas of land along the southern boundary at Green Hill were transferred from Purton to Lydiard Millicent. Purton contained 2,822 ha. (6,973 a.) in 1991. (fn. 10)

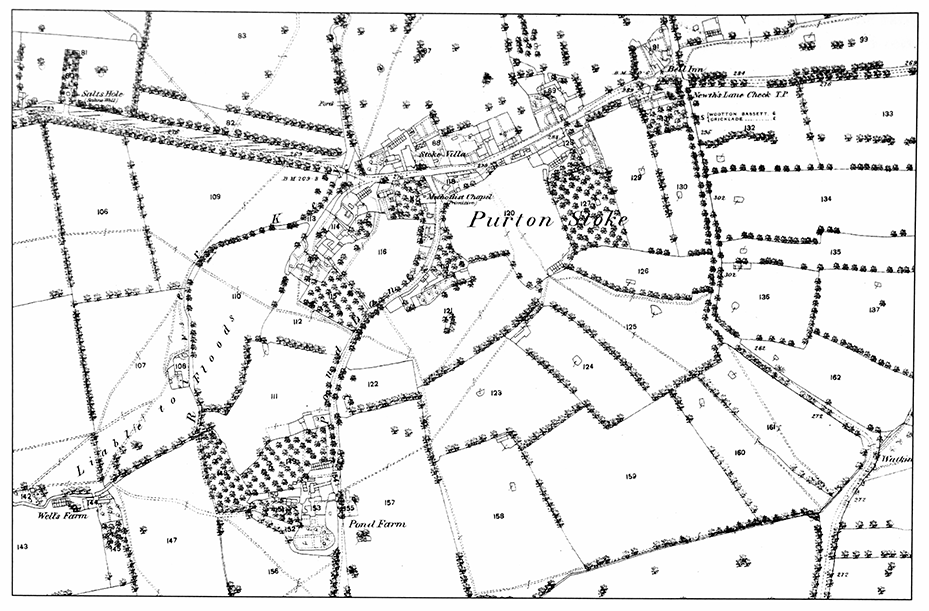

MAP 19. Purton and Braydon c. 1875. Most settlement developed in the east of the parish; the western half lay within the ancient boundaries of Braydon forest. The tithing of Braydon became a separate civil parish in 1866. For maps of Church End and other areas of Purton see following pages.

The late Anglo-Saxon bounds of Purton are purported to be set out in a Latin redaction of an Old English boundary clause. (fn. 11) The territory described has been shown to correspond in most respects to the later parish, including Braydon tithing but excluding Purton Stoke and the rags, its westward extension, although boundary points within the forested area may not have remained static. (fn. 12) A two-day perambulation in 1733 of the parish boundary, including Braydon tithing, Purton Stoke and the rags, was described in minute topographical detail. (fn. 13) New boundary stones were erected in 1999 to celebrate the millennium. (fn. 14)

Purton's pre-1984 boundary follows the Ray along its entire eastern length, and elsewhere utilises streams, including a length of the Key, field boundaries, and roads and droveways leading into the forest.

Landscape

The Corallian limestone ridge, which outcrops intermittently across north-west Wiltshire from Westbury to Highworth, is Purton's most prominent landscape feature. (fn. 15) It forms an escarpment running south and east from its highest point, 144m at Pavenhill, on which the village High Street, Dogridge, Restrop and Church End all stand. Disused quarries, where the stone was won for local buildings, are located south of Playclose, at the Hyde and elsewhere. (fn. 16) In places, north and south-east of Restrop, behind North View hospital and at Common Platt, Kimmeridge Clay overlies the Corallian; and beneath it at Ringsbury and south of Restrop a brownish-grey sandstone outcrops, known as the Ringsbury Spiculite Member or Rhaxella Chert. North of the Corallian escarpment, from Widham to Purton Stoke and the Ray, and westward below Pavenhill and Ringsbury into the former forest areas, the topography is uniform Oxford Clay, typically between 82m. and 100m. above sea level, but rising to 113m at Bury hill and 105m. near Blakehill farm. Alluvial deposits have formed along the Ray and the Key, and the Ray leaves the north-east parish boundary at about 80m. A saline well, Salts Hole, west of Purton Stoke village has been exploited as a spa. (fn. 17)

Communications

Roads (fn. 18)

It is very likely that the medieval road

between Oxford and Bristol, via Faringdon and

Malmesbury, passed through Purton, presumably

following a line similar to that mapped in 1675. (fn. 19) The

tithing, later parish, boundary with Braydon between

Battlelake farm and Braydon Manor farm is set back

from this road as if fossilising the line of a medieval

trench or clearing alongside a highway through

woodland where robberies might occur. (fn. 20) The road in

1675 entered the parish by a stone bridge over the Ray

north of Mouldon hill, continued along Collins Lane,

High Street and Dogridge, whence it descended to

traverse Braydon forest. (fn. 21) Use of this road may have

declined in the 18th century and it was not turnpiked.

A road running north from Wootton Bassett to Cricklade entered Purton at Restrop, turned east at Dogridge to follow the line of the old main road along High Street, and at Lower Square diverged north down the hill to Widham, past Purton Stoke village and on to Cricklade. It was turnpiked in 1790 and disturnpiked in 1879. (fn. 22) Tollgates were erected near where it entered and left the old main road; the tollhouse at Collins Lane Gate on Widham survives and still displays a table of fees. (fn. 23) A road further east ran parallel, linking Common Platt and Church End to Cricklade. It allowed access to agricultural land and the Wilts. & Berks. canal was later built alongside it. Minor north–south roads crossed Braydon forest, through the fingers of Purton land, and one, between Wootton Basset and Cirencester via Ashton Keynes, was turnpiked between 1810 and 1863. (fn. 24) The parish had many internal lanes, including Mud Lane, an ancient track leading from Ringsbury camp to Restrop, (fn. 25) and Hoggs Lane, first mentioned in the 1200s, (fn. 26) one of several lanes in central Purton. Bentham Lane turned west from the Cricklade road, north up Cow Street and west into Purton Stoke street.

Canals

The North Wilts. canal, opened in 1819,

linked the Wilts. & Berks. canal north of Old Swindon,

with the Thames & Severn canal, which it joined at

Latton. (fn. 27) The canal crossed the Ray on the Moredon

aqueduct. (fn. 28) Traffic ceased in 1906 and it was closed in 1914.

Railways

The Cheltenham & Great Western

Union Railway broad gauge line was opened in 1841,

with a station at Purton, as a branch from the Great

Western Railway trunk line to serve Gloucester and

Cheltenham. Its course runs diagonally through the

centre of the parish from south-east to north-west

corners. It was transferred to the GWR in 1844. After

1850 it became the main railway link between London

and south Wales. (fn. 29) Although Purton station was closed

in 1964, (fn. 30) the line remains open. In 1883 the Swindon

and Cheltenham Extension Railway Company opened

a second line through Purton, which traversed the

eastern edge of the parish, with a station named

Blunsdon (although just within Purton parish), which

opened in 1895 mainly for milk traffic. The company

became the Midland & South-Western Junction

Railway Company in 1883 and was absorbed into GWR

in 1923. (fn. 31) Blunsdon station was closed to passengers in

1924 and completely in 1937. A section of the line was

re-opened as the Swindon and Cricklade railway in

1978, centred on Blunsdon station, and enthusiasts are

working to restore the tracks and rolling stock. (fn. 32)

Population

Medieval Purton was a populous and wealthy parish. In 1086 there were 45 households of villein, bordar or cottar status, and five of demesne slaves. (fn. 33) There were 45 taxpaying households in 1332; (fn. 34) and in 1334 Purton paid 140s. out of a total of 216s. in tax collected in Staple hundred. (fn. 35) Purton's total of 318 adults paying the 1377 poll tax ranked it the twelfth most populous fiscal unit in Wiltshire. (fn. 36) In 1576, 33 households were assessed for a total £12 10s. 8d. tax, higher than any other community in the combined hundreds of Highworth, Cricklade and Staple. (fn. 37) In 1676 there were c. 700 adult communicants in the parish. (fn. 38) By 1801 the total population was 1,467 inhabitants and in 1821 1,766. Unlike most rural Wiltshire communities, numbers rose steadily throughout the 19th century. The 1841 total of 2,141 included 75 labourers building the Great Western Railway and 76 persons in the Cricklade and Wootton Bassett Union workhouse. The 1871 total, 2,344, was attributed to the increased number of mechanics employed at Swindon railway works; population peaked at 2,432 in 1891. The parish total included a separate figure for Braydon's inhabitants from 1821 when 70 people lived there. In the 20th century the population continued to rise steadily from 2,525 in 1901, to 2,678 in 1951, (fn. 39) 3,295 in 1961, 3,630 in 1971, 3,873 in 1981, 3,879 in 1991. (fn. 40)

SETTLEMENT

Early Settlement

Two Iron Age hillforts lie within the parish. Bury Hill, a univallate fort reduced by ploughing, stands on a low eminence remote from the main areas of settlement two miles west of Purton Stoke. (fn. 41) Ringsbury camp, west of Restrop, is bivallate with an eastern entrance and well preserved banks and ditches. It occupies a commanding site overlooking Braydon forest to the west. (fn. 42) Neolithic tools found within the fort suggest its reuse from earlier prehistory, (fn. 43) but very little other evidence of prehistoric activity in the parish has been found.

Building debris and pottery imply Romano-British settlement at various locations, east of Purton Stoke and near Church End south and south-west of the former Fox inn; (fn. 44) a Roman lamp was found c. 1890 in Purton churchyard. (fn. 45) The principal focus of later Roman activity appears to have been in the Dogridge area. Here an industrial site producing pottery from at least four kilns, probably for a short period in the 2nd century, was excavated in 1975. (fn. 46) It may have been associated with or superseded by one or more highstatus residences furnished with mosaics which were discovered further north between Dogridge and Pavenhill in an area named Black Lands in 1744. (fn. 47) To the east a late-Roman walled cemetery was discovered in 1987 on the site of Purton workhouse (North View hospital). Finds included opulent grave goods and a stone ossuarium containing cremated remains inside a glass vessel within a lead container inscribed with Christian symbols. (fn. 48)

An inhumation cemetery of the early Anglo-Saxon period was revealed during quarrying at the Fox from c. 1900; grave goods found in 1912 suggest that it was in use in the 7th century or later. (fn. 49) If the dating evidence is correct this cemetery may have been contemporary with the first acquisition of Purton by Malmesbury abbey in 688. (fn. 50)

Later Settlement and Built Character

From the 7th century to the 16th, Purton was among the largest and most important, if rather unwieldy, of Malmesbury abbey's possessions. Its settlement history in the medieval period is complicated by two factors. By the early 13th century, the abbey, while retaining considerable demesne, had leased out a substantial porton of its manor to a knightly family, who also held the serjeanty of the forest and the manor of Chelworth in Cricklade. (fn. 51) The submanor itself fragmented and as a result the abbey retained only a loose hold on many aspects of life in Purton; the new estates became, in effect, distinct manors with their own demesne. In consequence Purton parish embraced settlements of various types, including hamlets such as Purton Stoke and Pavenhill, moated sites at Widham and Bentham, and high-status houses at Church End, Restrop and elsewhere. Alongside these holdings the abbey retained, along with the overall lordship, some demesne land, and control of the mills and the church. A second complicating factor was Braydon forest, much of which occupied the western third of Purton parish even after the forest bounds were reduced in 1300. Largely unpopulated, it was a resource exploited in different ways by the abbey, the Crown, the manorial lords and their tenants; their various rights and prohibitions affected not only parish government, but also the pattern of settlement. The forested area was regarded as a tithing of Purton, and some aspects of Braydon tithing's history are treated separately.

The location of the Anglo-Saxon cemetery some 2km. east of its late-Roman predecessor, and Malmesbury abbey's decision to establish its demesne premises nearby, and perhaps found a church there also, (fn. 52) may be indications that the main area of settlement shifted eastwards along the Corallian escarpment between the 5th and 7th centuries. The subsequent isolation of Church End, leaving manor house and church some 600 m. south-east of High Street, is best explained by the development of Purton in the Middle Ages as a thoroughfare village along a main road. Away from these two foci, medieval hamlets and farmsteads were scattered through the parish, both on the Corallian, at Restrop, Bagbury, Pavenhill and elsewhere, and on the clayland to the north, at Widham, Bentham and Purton Stoke. (fn. 53) Several clayland farms, at Widham, Bentham and Pond Farm, Purton Stoke, were moated, and there is archaeological evidence of medieval settlement desertion at Common Platt and Purton common. (fn. 54) In the early 17th century there were at least 149 agricultural holdings, 28 in High Purton, 29 in Restrop and Pavenhill, 36 in Westmarsh and Widham, and 29 in Purton Stoke and Bentham, (fn. 55) and more than 60 recently-built cottages housed poorer inhabitants. (fn. 56) The inclosure of the common lands in the 18th century caused many more scattered farmsteads to be built in outlying areas, surrounded by their newly allotted fields and closes.

The parish experienced considerable development in the 19th century, particularly after the coming of the railway in the 1840s. Among many small homes were Wheatfield Cottages, built east of Church End at the Fox in c. 1884. (fn. 57) The break-up of the Shaftesbury estate in 1892, when much of the land was sold as small building plots with road frontage, also contributed to the 'suburbanisation' of Purton, which continued throughout the 20th century.

Purton's prosperity throughout its history is reflected in more than fifty listed buildings and monuments scattered throughout the parish. (fn. 58) Its architectural heritage was described in 1894 as one of the most interesting in north Wiltshire for the mansions and farmhouses of the gentry, 'representing in well-nigh unbroken succession the various stages of domestic architectural development from Elizabethan times'. (fn. 59) Houses built for those of middling social rank in the last two centuries reflect every phase of modern suburban development from late 19th century red brick terraces to inter-war bungalows and council housing and late 20th-century cul-de-sacs. (fn. 60)

Surviving farmhouses and buildings dating from the late 16th to the early 19th century conform to the local vernacular with limestone rubble walls and stone slate roofs. The higher status manor and farmhouses, notably Manor Farm, Restrop and Bentham House, are built with dressed stone and reflect national architectural fashions. From the mid 19th century brick was used for many smaller homes. Much 20th-century development was piecemeal and apparently built with little overall planning control, resulting in a lack of coherence to the appearance of the main village streets. Recent building campaigns have been more sympathetic to local traditions, notably at Thompson's Close built on the former garage site on the corner of High Street and Restrop Road.

In describing the built environment of the parish it will be convenient to consider first the early village nuclei of Church End and High Street; then the outlying settlements, including those now engulfed in suburbs; and finally Purton Stoke village. Buildings associated with the major manorial and estate owners receive separate treatment as part of Purton's manorial history.

Church End

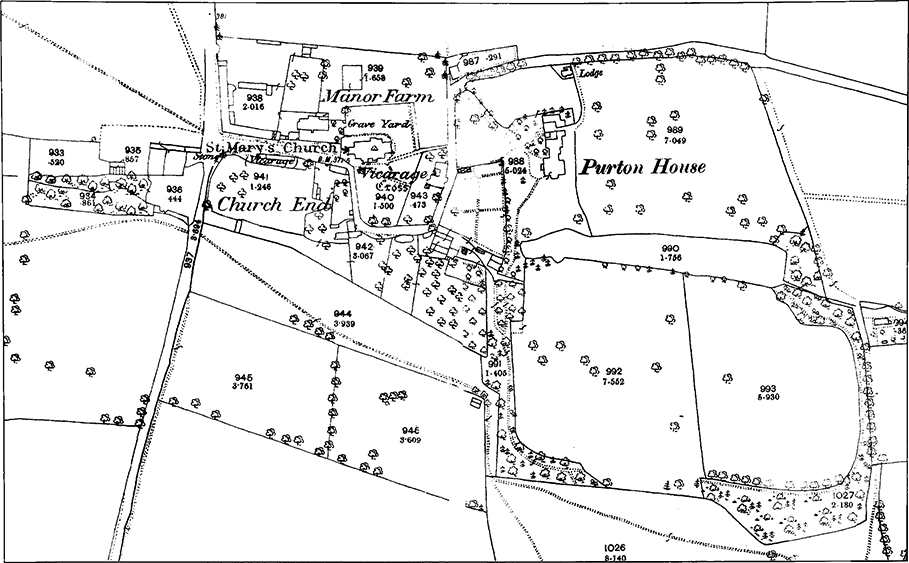

MAP 20. Purton, Church End in the late 19th century.

Standing aloof from the main built-up area of Purton, Church End consists of the church, approached by a straight avenue flanked by the manor house, its long range of farm buildings, and cottages. In the Middle Ages a number of farmsteads apparently clustered around the church. A recently-built vicarage stood at the entrance to the church in 1276: to the south two other houses shared its plot, and the hall, a dwelling house and crofts belonging to Malmesbury abbey lay to the east. (fn. 61) The rent from Chamberlains, later Purton House, funded the office of Malmesbury abbey's chamberlain. (fn. 62) The Buthaye, 4 Church End, stood on church land called Parson's hey or Court close, where by the 16th century lay a church house, known as Church Inn in the 17th century, when the complex of buildings included a grange, brewhouse, malt kiln, cottage and outbuildings belonging to the Gleed family. (fn. 63) Following the dissolution of Malmesbury abbey and the sale of the manor and rectory estates, Church End was redeveloped: the manor house was rebuilt by Edmund Bridges, Lord Chandos, in the later 16th century; (fn. 64) 3 Church End was built as a farmhouse in the 17th century; and Thomas Gleede, a wealthy yeoman and former tenant of the abbey, built a farmhouse, now called the Milk House, in 1656, (fn. 65) on land which was once part of the abbey's demesne. (fn. 66) Church End has apparently changed little in the intervening centuries and was designated a conservation area in 1974. (fn. 67)

High Street

38. View of Purton's High Street, looking towards the Angel Inn, around which settlement was concentrated in the 18th century.

Purton's narrow high street follows a meandering course for c. 1 km along the limestone ridge. Settlement grew up around the crossroads at the east end of High Street (Lower Square). It was concentrated around the Angel inn in the 18th century and extended west to just beyond Play Close on the south side of the road. Between Play Close and the junction with Restrop Road further west (Upper Square), arable land lay to the south and farmsteads were scattered along the north of the street with small clusters of buildings at the junctions with Hoggs Lane, or Side of Pipney, and the lane to Pavenhill. (fn. 68) Little had changed by the early 20th century, although there was some infilling on both sides of the street. (fn. 69) The older houses are either of local rubblestone sometimes dressed with brick, or of brick. Tudor Cottages, 20–21 High Street, date to c. 1600 and 7 High Street is dated 1673. (fn. 70) College farmhouse and the Court (now Purton Court, 3 High Street) are discussed below. (fn. 71) Many new buildings appeared between the late 18th and mid 19th centuries, some with shallow slate roofs, and a landmark was established at the corner of Lower Square in 1879 when the tall free-style Workmen's Institute was built. During that period several farmhouses were rebuilt in fashionable style, and most were detached from their lands to become gentry residences for wealthy local families or incomers. (fn. 72)

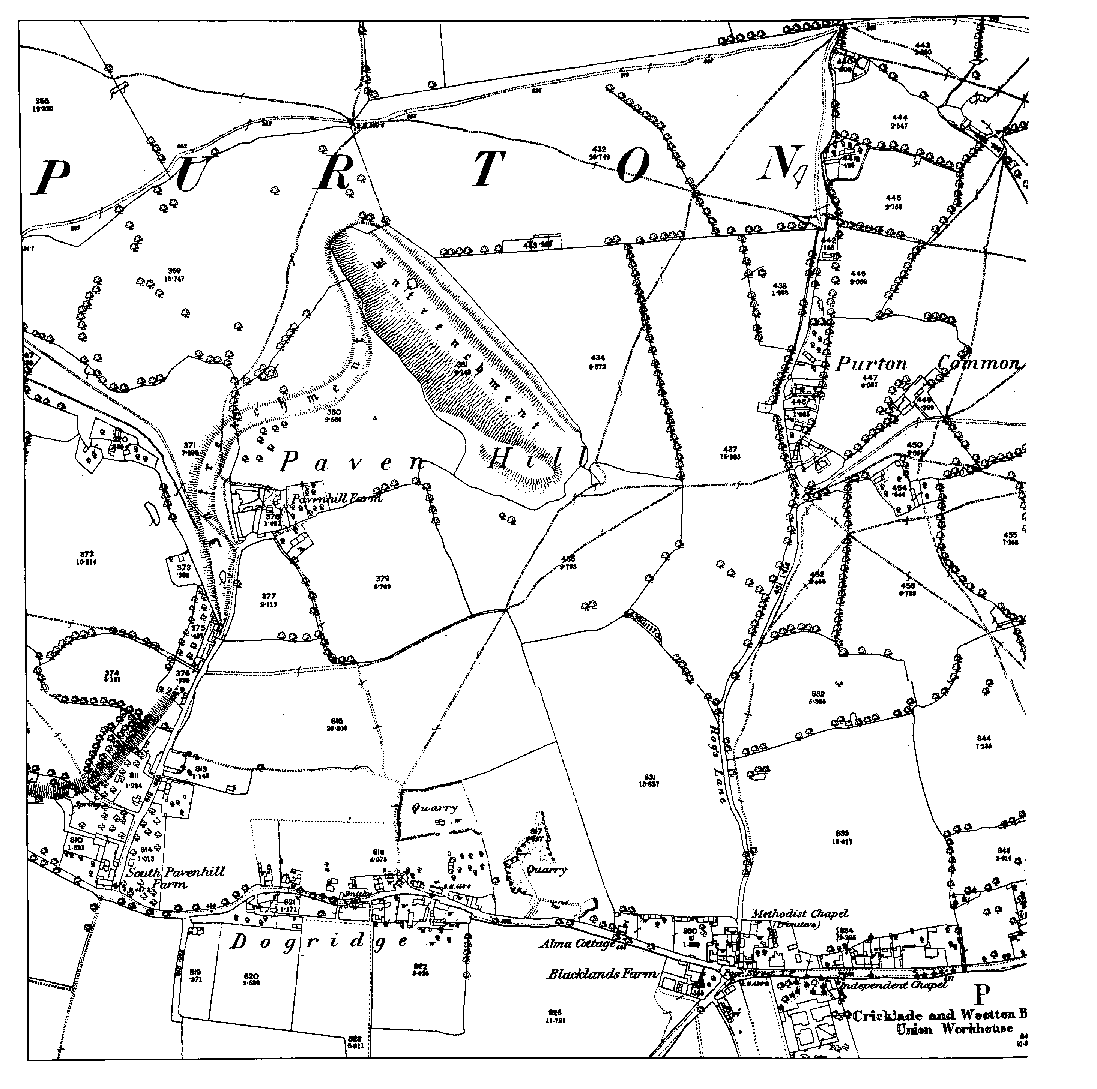

MAP 21. Purton, the centre of settlement in the late 19th century.

Hallidays, 24 High Street, was named after the Halliday or Holliday family: (fn. 73) '1784 R x H' is carved on an attic beam of this 18th-century farmhouse. In the 19th century it was redesigned as a gentry residence and a farm building became a coach house. It belonged to Richard Garlick Bathe in 1840 and was occupied by the Misses Bathe. (fn. 74) When it was sold in 1920, the coach house had become a 'motor house'. (fn. 75) Hallidays was part of the Bathe estate centred on High Street inherited by the Brown family. The 1920 sale of the estate led to development in the area between Upper Square and along the south side of High Street: parts of Blacklands farm were sold to Cricklade and Wootton Bassett Rural District Council between 1920 and 1945 to build council housing from Pavenhill in the west, along Dogridge and High Street to Church End. Hoggs Lane leads north to Purton Common. (fn. 76) Infilling took place on both sides of High Street in a variety of building styles and several housing estates and cul-de-sacs were built behind the street.

Dogridge and Pavenhill

In the decades around 1800 building took place on each side of Pavenhill between the junction with Hoggs Lane and the turning to Upper Pavenhill. On the south side a detached house dated 1767 stands alongside a terrace of cottages dated 1896 and the Cricklade and Wootton Bassett workhouse which was built in 1837. The Primitive Methodist chapel built in 1856 at the south end of Hoggs Lane, farm buildings altered for residential use and cottages with 20th-century modifications survive, together with infill housing of varied periods and styles. (fn. 77)

There was settlement at Pavenhill by the 13th century, (fn. 78) when the homesteads of the Malreward and Walerand families stood there. (fn. 79) In the early 1700s there were several farmsteads along the main highway leading past Lower Pavenhill farm, the home of the Gleed family. There was settlement on both sides of the road leading to Upper Pavenhill farm from LowerPavenhill farm, which dates from the 17th and 18th centuries and has stables dated 1777 constructed of diaper brickwork for Thomas Plummer. In c. 1990 an early 17th-century barn was converted into a dwelling house. (fn. 80) The present buildings along the lane to Upper Pavenhill date from the later 18th century onwards and are generally of rubblestone construction. (fn. 81) Small cottages have been knocked into larger homes and later 20th-century and early 21stcentury infill has been constructed out of similar materials to blend in with older buildings. In the early 20th century Pavenhill was known as 'Copper Street' because it was the poorer end of the village. (fn. 82)

Southern Purton

Restrop and Bagbury both grew up around farmsteads on the stonebrash soil to the south of the main village. Restrop is on an ancient track leading from Ringsbury camp. (fn. 83) The name, first recorded in 1208, (fn. 84) is derived from a personal name and thorp, the Old English for settlement. (fn. 85) In the 13th century the Radesthrop family, free tenants of Malmesbury abbey, were its principal inhabitants. (fn. 86) Restrop house was rebuilt as a mansion by the Digges family c. 1600. (fn. 87) Bagbury is first recorded in 1250, when Nicholas of Baddebyr, a knight, lived on a 2virgate freehold estate. (fn. 88) Neither hamlet grew in significance, (fn. 89) and both remain small clusters of cottages around their ancient farmsteads.

There was settlement at Common Platt by the later Middle Ages. (fn. 90) The hamlet grew larger in the 19th century. (fn. 91) It consists mainly of mid 20th-century houses and bungalows, (fn. 92) and cul-de-sacs of late 20th-century housing south-east of the Foresters' Arms at Common Platt and Sparcells, built as part of Swindon's western expansion. (fn. 93)

The Widham area

There were several farmsteads to the north of the main village. At Widham a moated site was occupied in the later Middle Ages, (fn. 94) and there was settlement in the area of Common farm. (fn. 95) Widham farm was built c. 1600. (fn. 96) Further north along Cricklade road Pound Farm (fn. 97) and the cottages at Packhorse Corner (fn. 98) were built in the 17th century. On the road leading north east from Church End, Pry farmhouse (fn. 99) and Crosslanes farmhouse (fn. 100) were built in the 17th century, and buildings at Packhorse, Hurstead and Haxmore farms in the 18th and 19th centuries. (fn. 101) Park House Farm was built in the late 18th century, apparently on the site of an earlier farmstead. (fn. 102) By the early 18th century there was housing around Bowshot along Witts Lane and along the west side of the lower reach of Hoggs Lane. (fn. 103) Terraces of red brick houses were built along Station Road in the late 19th century and in the 20th and early 21st centuries cul-de-sacs of modern homes were built between Station Road and Purton common. By 1650 there was a farmstead at West or West Marsh, (fn. 104) later known as Purton Common Farm. (fn. 105)

39. The Victorian front of Bentham House, an 18th-century farmhouse almost completely rebuilt by the Sadler family.

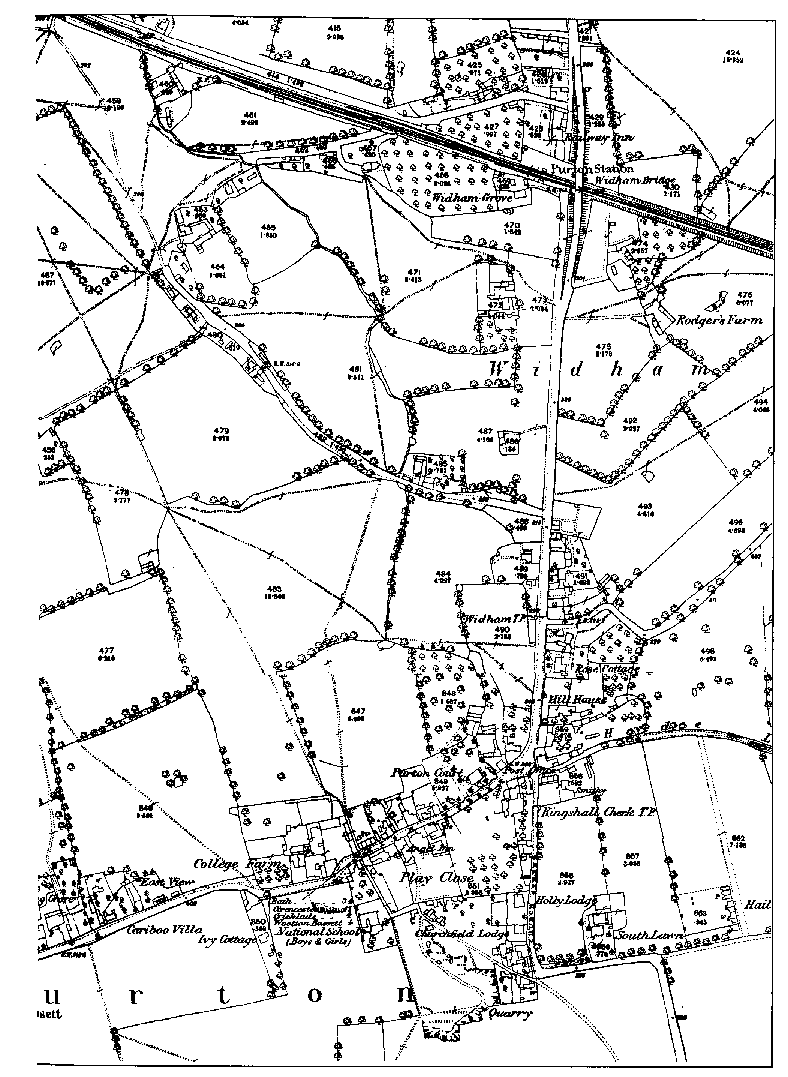

Purton Stoke

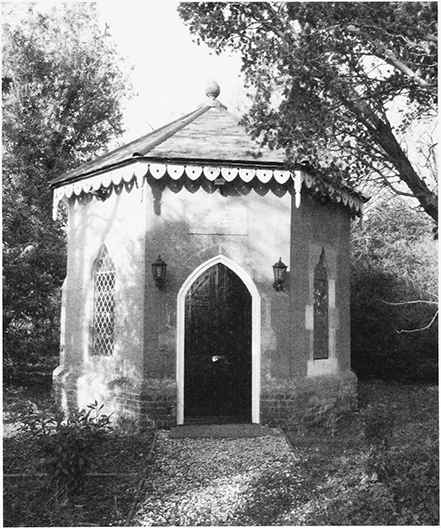

Occupying the northern, largely clayland, portion of the parish, Purton Stoke stands apart from the main village, c. 3.5 km. north of the parish church. The earliest part of the settlement, first recorded in 1257, (fn. 106) was built on an area of raised ground, which curves to the south west along the bank of the Key and overlooks Stoke common. Here, south of the junction between Pond Lane and the west end of Stoke street, several cottages and farmsteads are arranged around what may once have been a village green. One former farmstead dates to c. 1600, and to the south-east of the junction stands No. 34, an 18th-century rubblestone house with long timber lintels over the windows. No. 35 is of a similar date. To the north-east of the junction, Purton Stoke House dates to c. 1800. A farmhouse belonging to the Shaftesbury estate, it was later used as a private school, and known as Stoke Villa by 1875. (fn. 107) Further west within a small garden on Stoke common, is Salts Hole, an octagonal well house designed in playful Gothic style and built of rendered brick over the saline spring in 1859. (fn. 108)

South of the village, approached by Pond Lane and Cow Street, stand the moated Pond Farm and Bentham House, both associated with major Purton landowners. (fn. 109) Land to the south and east of Bentham House show the ridge and furrow pattern of preinclosure arable cultivation. In 1640 Thomas Shayle owned Benthams, and a cottage called Redlands. (fn. 110) In the 18th and 19th centuries the hamlet consisted of a group of farms, (fn. 111) including Bentham farm, (fn. 112) New farm and Stoke Common farm. (fn. 113) By 1941 there was another farm called Dairy farm. (fn. 114)

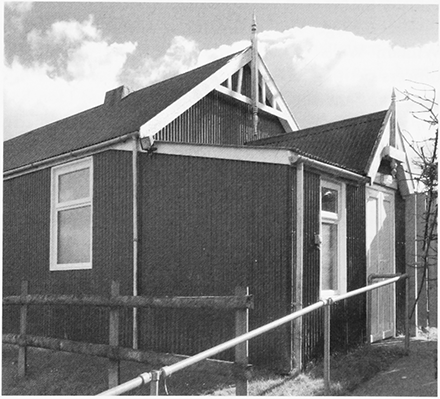

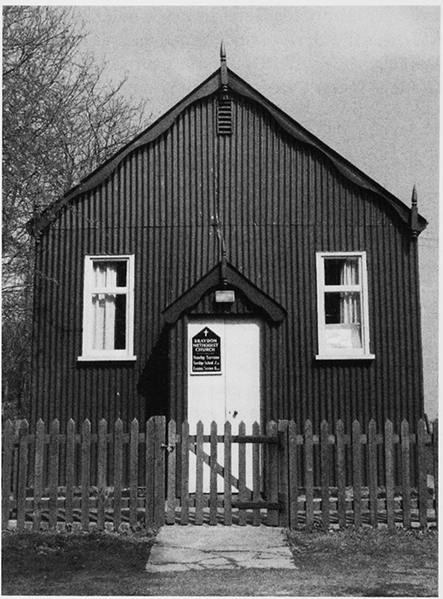

Stoke street stretches east along a low ridge from the junction with Pond Lane. Around 20 farmsteads were laid out along both sides by the early 18th century. (fn. 115) The street now has a mix of limestone rubble and brick buildings. The farmhouses were built in the local style in the 18th and 19th centuries. Of the 18th century are Manor Farmhouse, set end on to the street, no. 17, Dairy Farmhouse, of brick with long timber lintels, and Stoke Cottage which has an early-to-mid 19th-century extension. No. 38, built of rubblestone with a formal front of three bays, dates to c. 1800. Cottages along the street appeared mainly in the 19th and early 20th centuries. At the east end, Stoke street crosses the road to Cricklade and becomes Newths Lane. The Bell inn was built in the early 19th century to the north-west of the crossroads, and a corrugated iron reading room south-east of them in 1909. (fn. 116)

MAP 22. Purton Stoke in the late 19th century

Because it was further from the railway station, less development of suburban character occurred at Purton Stoke in the 19th century than around Purton village. However, the farming community of the early 20th century had changed to one of commuters by the early 21st century. The 1928 sale particulars for Dairy Farm suggested that the house might become a 'gentleman's residence'. (fn. 117) Subsequently other farmhouses have been converted to dwellings and new houses have been built between older ones along the street, including semidetached council housing at the east end. (fn. 118)

North-west of Purton Stoke, Blakehill airfield was built in 1942–3 on 580 a. of land belonging to Blakehill farm in Purton and Whitehall farm in Cricklade. It was used for D-day and other Second World War operations and closed in 1946. Afterwards it was used for training, and later a GCHQ monitoring station was set up there. The site was partially cleared in the 1970s and the runways used as hardcore to build the M4 motorway. In 2000 it was acquired by Wiltshire Wildlife Trust and became the subject of one of Europe's largest grassland restoration programmes. (fn. 119)

MANORS AND OTHER ESTATES

Malmesbury abbey owned Purton from the 7th to the 16th century, and in the Middle Ages leased much land to tenants. When the main lay submanor was divided between heirs c. 1266, each claimed manorial status, and three manors emerged, all probably focused on the area of the church and Church End: Purton Keynes, Purton Paynel (later Poucher), and Gascrick. These co-existed with the abbey's rectory estate and with smaller freeholds, at Bentham and Pond farm in Purton Stoke, and in the south of the parish, at Pavenhill, Restrop and elsewhere. By the 16th century Purton Poucher (formerly Paynel), had apparently combined with Purton Gascrick and Wootton manor and these lands were then sold piecemeal; the rectory estate and Bentham, a Purton Stoke freehold, were held with Purton Keynes manor. The post-medieval descent of the manors is confusing because holdings which were sold off carried certain manorial rights with them and the names of the principal manors were then attributed to more than one portion of their former lands. The fragmentation by sale of the Purton Keynes estate c. 1609 added further complications. A new landholding élite emerged which accumulated estates in the parish, principally the Sadler, Cooper (Shaftesbury), Maskelyne and Bathe families. These holdings in turn were broken up in the later 19th and early 20th centuries, permitting piecemeal suburban development.

In the following sections each manor of medieval origin is described in turn, and then the estates that emerged after 1609 are considered. Ownership of Braydon, which lay partly in Purton parish, receives separate treatment as part of the history of Braydon tithing.

MALMESBURY ABBEY'S MANOR

As part of Malmesbury abbey's accumulation of lands in north Wiltshire under Abbot Aldhelm, the West Saxon king Caedwalla granted the abbey a 30-hide estate 'on the east side of Bradon wood' in 688. (fn. 120) This can be equated with all or part of the 35-hide estate at Purton taken from the abbey by the Mercian king Offa and restored to it by his son Ecgfrith in 796. (fn. 121) The abbey may twice have lost possession of Purton again, before 854 and in the mid 10th century. (fn. 122) By 1066 Malmesbury had regained ownership and Purton remained an important constituent of the abbey's Wiltshire landholdings until its dissolution in 1539. (fn. 123) At that time income from the Purton estates was assigned to the abbot's exchequer, and the offices of cook, chamberlain and refectorian. (fn. 124)

From an undated boundary clause it is clear that Malmesbury's pre-conquest property at Purton at one time included much of the later parish but excluded Purton Stoke. (fn. 125) By 1086, however, since no other landholding in Purton is described in Domesday Book and none is required by the geld roll total for Staple hundred, the abbey's estate was probably computed to include Purton Stoke and any land supporting a possible early minster church. (fn. 126) Keynes rag and Poucher's rag, however, within the royal forest, were not regarded as lying within Purton parish until the 13th century or later.

By the early 13th century, the abbey had formed a substantial portion of its Purton holdings into a lay submanor, held by Thomas de Sandford, son of Richard de Sandford, and serjeant of the forest and lord of Chelworth in Cricklade in the 1230s. (fn. 127) The submanor was leased in return for military service. Thomas de Sandford, described as a knight engaged in abbey business in 1221, (fn. 128) was succeeded by his nephew Adam, who held ¾ knight's fee in Purton in 1242. (fn. 129) Adam of Purton, who also had interests in Chelworth, Staple hundred and Braydon forest, died without male heirs c. 1266, and his Purton estate was divided between his three daughters and their heirs. Half was inherited by his grandson Robert de Keynes (son of his daughter Margery), and a quarter each by Catherine, wife of Sir John Paynel, and Isabel, widow of Sir Robert de Welle. (fn. 130) This tripartite division resulted in three manors, sometimes known as Purton Keynes, Gascrick and Purton Poucher, which co-existed in Purton under Malmesbury abbey until the later 15th century.

Despite these important changes, the abbey retained its manorial site and a valuable demesne. (fn. 131) In 1276, under the enterprising William of Colerne, abbot 1260–96, it appropriated the rectory estate, developed its manorial site, and purchased or recovered the landholdings in Purton of Walter Smith, Gervase Wotton and Agnes Paynel. (fn. 132)

In 1515, the new abbot, Richard Camme leased the manorial site and demesne, together with the vicarage and advowson, to Richard Pulley and his wife Margaret for an annual rent of £23. Pulley died c. 1526 and his wife Margaret lived on at the manor until c. 1544, when she was succeeded by her daughter Isabel and her husband Benet Joy or Jay. Following the dissolution of the abbey in 1539, the abbey's demesne manor had reverted to the Crown, which in 1544 granted it, together with the rectory estate, to Sir Edmund Bridges (d. 1573), son and heir of the lord of Purton Keynes and 2nd Baron Chandos from 1559. (fn. 133) These changes provoked a bitter dispute with the abbot's lessees. In 1548, in the court of Star Chamber, Isabel and her husband alleged that Bridges had been harassing them to leave, forcibly entering their dwelling in Purton with armed men, attacking their servants, destroying their dovecot, killing livestock and polluting their well. (fn. 134)

The abbot's lessees were eventually evicted and Bridges thereafter rebuilt the manorial house, which was then occupied by members of his family. (fn. 135) Edmund Bridges left the manor to his widow Dorothy for life, and to provide an income for his younger son William. (fn. 136) It passed to Edmund's heirs, his sons Giles (d. 1594) and then William (d. 1602), by when the manor was assessed at only one-twentieth of a knight's fee. (fn. 137) William's son Gray Bridges, Lord Chandos (d. 1621), sold the lands piecemeal in 1609, after the death of Nicholas Stevens, who was tenant of the manor by right of his wife Frances (neé Bridges). (fn. 138) It was as a result of this sale that landholding in the parish fragmented, leading to the creation of new estates which were to dominate Purton's tenurial history through later centuries.

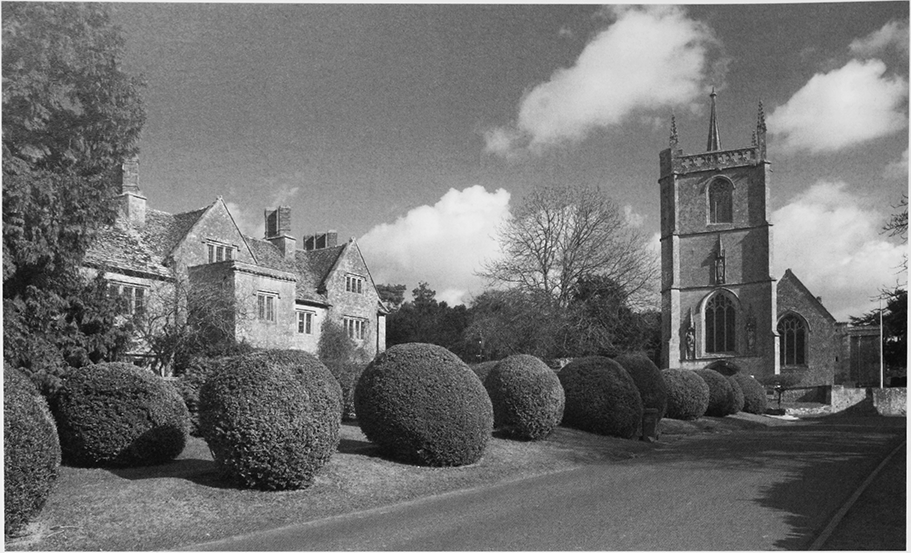

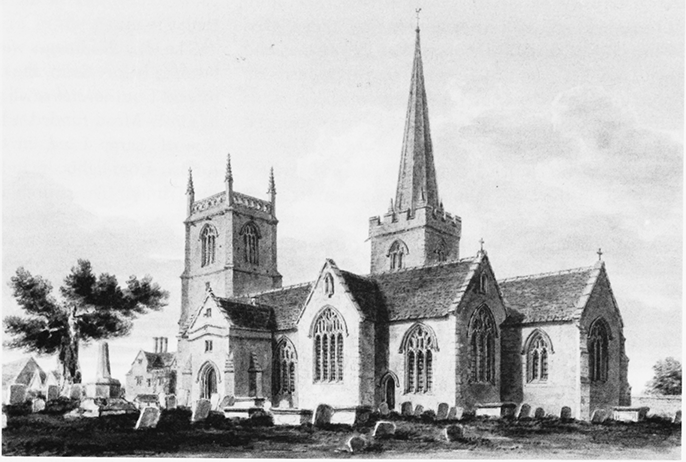

40. View of Church End, looking east with the Manor House, rebuilt by Edmund Bridges, lord Chandos, in the later 16th century, and the tower of the parish church.

The Bridges family retained some lands, concentrated in Purton Stoke (fn. 139) and the title to the manor, which passed to George Bridges, Lord Chandos (1620–1655) and then to his widow, Jane (d. 1676). In 1657 Jane married George Pitt (d. 1694) of Stratfield Saye (Hants.) and the property passed to Pitt and his descendents. (fn. 140) In 1738 George Pitt of Stratfield Saye was described as lord of the manors of Great Purton. (fn. 141) He died in 1745 and was succeeded by his son, also named George (d. 1803), who was created 1st Baron Rivers in 1776. (fn. 142) Purton Keynes and Purton Poucher farm of c. 50 a. was sold off in 1792. (fn. 143) The Purton estate descended with the manor of Minety, which was owned by one Joseph Pitt c. 1792–1844, (fn. 144) perhaps the same Joseph Pitt who owned Bury Hill farm, c. 250 a. in Purton Stoke in the same period. (fn. 145) By 1875 the Pitts were no longer lords of the Purton's manors, described at that date as the Great manor, Purton Poucher, Purton Keynes and the Little manor, which included Purton common. (fn. 146) Dr Waraker was lord of the Great manor c. 1870–80, (fn. 147) and sold it with the Hill House estate, c. 40 a. to Cornwallis Wykeham-Martin (d. 1903), from whom it passed to his son Charles Wykeham-Martin (d. c. 1911), whose trustees sold it in 1920, (fn. 148) after which the title lapsed. Edmund N. Ruck, lord of Purton Keynes manor c. 1875–80, (fn. 149) was succeeded by Thomas Glenn c. 1898, and his trustees c. 1903–1911. (fn. 150) Lordship of the Great manor, Purton Poucher, and Purton common was also claimed by the earls of Shaftsbury, (fn. 151) who sold lordship of Purton Poucher to Charles M. Beak, whose trustees sold it to Helen Walsh. (fn. 152)

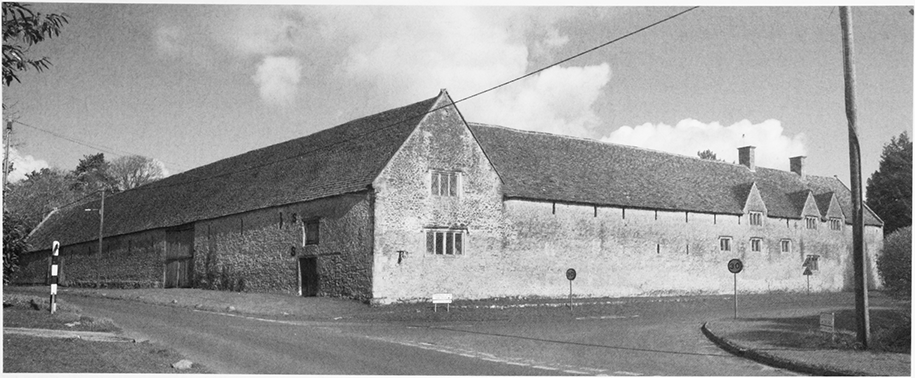

41. The two ranges of barns on the manorial site, from the south-west. The east end of the south range was converted into cottages in the 19th century.

Manor House (Church End)

Malmesbury abbey's

manorial site lay to the west of the church, where the

present manor house stands. William of Colerne (abbot

1260–96) redeveloped it, building a hall inside a

surrounding wall and a grange with a stone roof. A new

garden was laid out with two fishponds and a third

fishpond was made near the abbey mill. In the farmyard

he built another great stone-roofed grange, a thatched

cowshed next to the entrance gateway and two

dovecotes. (fn. 153) This aggrandisement may have been the

result of acquiring the site of the rectorial curia,

which presumably lay nearby, as a result of the

appropriation of 1276. (fn. 154) In 1547 the abbot's mansion

house had a parlour and buttery with an entrance

passage between them, a separate kitchen in the same

courtyard, a dovecote and farm buildings. (fn. 155) The

abbot's manor house was rebuilt by Edmund Bridges

before his death in 1573 at a cost of £1,200. (fn. 156) In 1610 it

was sold to Sir Anthony Ashley (d. 1628), (fn. 157) who

assigned it to his daughter Ann (d. 1628) on her

marriage to John Cooper (d. 1631). (fn. 158) It was one of the

homes of their son Sir Anthony Ashley Cooper, 1st earl

of Shaftesbury (d. 1683), (fn. 159) and in the early 18th century

was occupied by the scholarly Maurice Ashley

(Cowper) (d. 1726), brother of the 3rd earl of

Shaftesbury and translator of Xenophon's Cyropaedia. (fn. 160)

In the later 18th and 19th centuries the Ashley Coopers

apparently let the manor house to tenants, gentlemen

farmers, who included members of the Bathe family

and John Brown, a descendant, from c. 1851–93. (fn. 161)

In 1895 Charles Miles Beak, who had returned to Purton from Canada after making his fortune as a cattle drover and rancher, bought the manor house from the 9th earl of Shaftesbury. He lived there from 1895 until his death in 1900, giving a piece of his land to extend the churchyard. (fn. 162) After his death, in 1900 his executors retained 139 a. farmed as Church farm by James D. Beak in 1911. (fn. 163) Purton manor house was sold with 84 a. to Helen Walsh, widow of Arthur Francis Walsh, of the Hoystings, Canterbury, and her son Arthur J. Walsh, (fn. 164) who sold it c. 1952. (fn. 165) The Walsh family made extensive alterations to the interior and to the farmyard, gardens and surrounding closes. (fn. 166) The house was owned briefly by Thomas Fairfax, 13th lord Fairfax, subsequently by Mr and Mrs Garraway and Charles Arnott, partners in a veterinary practice run from the barns, and by Mr Thompson, a timber merchant, who sold it to the current owner Mr Coxen, a commodity broker, and his wife in 1984. (fn. 167)

The manor house stands north-east of the church slightly above the road on made-up ground; the garden to the north is terraced down to a boundary wall which may reflect the line of an old road; disturbed ground in the field north of that may indicate additional buildings once stood there. The south front of the house is 17thcentury, of five bays with gables over the centre and end bays, mullioned windows of three and four lights and a two-storey south porch which may be original. The end bays project to the north as wings, and in the angle of the east wing lies a stair tower. A modern west porch bears a stone inscribed 168.. The very thick north wall of the central three bays may predate the 16th century. It incorporates a newel stair with timber treads and belonged to a building with a ground level much lower than the present one. The eastern two bays of the house seem to have been built with two tall storeys, which may represent hall and great chamber of an apparently grander house; the upper room, according to the roof structure, had a plaster barrel-vault, probably of the late 16th century. In the 17th century the western end of the house was rebuilt with the present floor levels, and the eastern end reconstructed as a cross wing. In the later 19th and early 20th centuries the exterior was tidied up, and before 1887 rooms had been built on the north side between staircase tower and west wing. Two north-west service wings with courtyard between had been built before 1923. (fn. 168)

The present barns are arranged as an L west of the manor house. The two ranges, of ten and thirteen bays, were probably built in the late 16th century or the 17th century; the roofs have tenoned collar and tie trusses with queen struts and upper raking struts. Both barns were made to look picturesque in the late 19th century, probably by C. M. Beak. The changes included the insertion of modern brick into the timber framing below eaves level, the conversion of the east end of the south range into a dwelling and milking parlour with granary over, and the re-use of mullioned windows, probably from the house, to light an east staircase and fill openings broken through the south-western gable. Other outbuildings then in the farmyard may have flanked a surviving brick granary with dovecot and 1746 date. (fn. 169)

PURTON KEYNES

The estate described in 1375 as Purton Keynes manor passed from Robert de Keynes in 1281 to his son and heir, Robert, a minor, who came of age in 1289, (fn. 170) and before his death granted it to Hugh le Despenser, earl of Winchester. On Despenser's fall, it was confiscated by the Crown, but was returned to Robert's widow Eleanor as dower in 1327. (fn. 171) The estate passed to their son Robert de Keynes, (fn. 172) and by 1361 was held by John de Keynes, who died in 1366, leaving it to his son John, a minor. (fn. 173) John became a royal ward and in 1370 his property was leased to John Wecche, or Weeks. (fn. 174) In 1375 John de Keynes and his sister Gwenllian both died as minors, and the estate passed to their aunt Elizabeth, sister of John de Keynes, who apparently sold it to William of Brantingham. (fn. 175) Elizabeth died in 1385 and her heir was Margaret, widow of William of Wootton, who relinquished her claim to Brantingham. (fn. 176)

Brantingham held the manor, by then known as Purton Keynes alias Brantingham until his death in 1413. (fn. 177) The manor then reverted to Alice, wife of Lewis Cardigan, a descendent of the de Keynes family. In 1420 she granted the manors of Purton Keynes and Purton Stoke to Robert Andrew, who held them in 1428. (fn. 178) Until 1502, when he was attainted and his lands forfeited to the Crown, these manors were part of the estate of Edmund Ferrers, centred on Blunsdon. (fn. 179) In 1503 the King granted the estate to Giles Bridges (d. 1511), (fn. 180) and at the time of Malmesbury abbey's dissolution, it was held by his son, Sir John Bridges (1st Baron Chandos from 1554, d. 1559). (fn. 181)

After Sir John's death, Purton Keynes manor presumably passed to his heir Edmund Bridges, and Lord Chandos, by then lord of the abbey's demesne manor. It descended with that manor with Edmund's heirs at least until the sales of 1609.

Keynes Court

A manorial or court house had

evidently been built by the earlier 13th century, when

Thomas of Purton (d. by 1238), who had already

granted his demesne tithes to Malmesbury abbey,

received permission from Abbot John (1222–46) to

establish a private oratory within its walls, provided it

did not prejudice the rights of Purton parish church. (fn. 182)

Keynes Court or Place is mentioned in 1376 as held by

Gwenllian Keynes. (fn. 183) Described as the demesne house, it

was still in existence in 1609 when it was sold to William

Read, a yeoman. (fn. 184) Its location is unknown. (fn. 185)

PURTON PAYNEL (POUCHER)

Isabel de Welle's quarter of her father Adam of Purton's estate appears to have passed to her Paynel relatives by 1274, when it was held jointly by her brothers-in-law Robert de Keynes (d. 1281) and Sir John Paynel (d. 1275) and assessed as a ½ knight's fee. (fn. 186) It presumably descended to John and Catherine Paynel's sons, John (d. 1287) and Philip (d. 1299) and then to John Paynel (d. 1334) and was inherited by his daughter Margery (d. 1349), wife of John Pouger, from whom it passed to their son, John Pouger. (fn. 187) He died in 1405, having unsuccessfully tried to gain possession also of Gascrick manor. (fn. 188) His son John Pouger added a freehold called Nele's place to his Purton property before he died in 1418. (fn. 189) His heir was his son Henry, a minor, who died in 1421. (fn. 190) Nele's place became the property of John Pouger, who died in 1423, (fn. 191) and in 1428 another John Pouger was tenant under Malmesbury abbey. (fn. 192) The manor passed to the Sotehill family by marriage. When Sir John Sotehill died in 1495, his son George, a 'natural idiot from his birth' was heir. (fn. 193) On George's death the manor of Purton Poucher passed in 1502 to his sister Barbara, wife of Sir Marmaduke Constable (d. 1545), whose family subsequently broke up the manor. (fn. 194)

A capital messuage in Purton, held by Catherine Paynel, daughter of Adam of Purton, at her death in 1296, and rented from her nephew Robert de Keynes, was perhaps originally that of the Welle's or Paynel portion of Adam's inheritance. (fn. 195) The capital messuage and lands of Purton Poucher were sold in 1553 by his son, Robert Constable to William Telling, husbandman and Thomas Calfee, yeoman. The sale included Poucher's grove, later known as Pouchers rag, 300 a. of Braydon forest. (fn. 196) The Constables sold another portion of their estate to Sir Anthony Hungerford (d. 1558), (fn. 197) of Down Ampney (Glos.), whose kinswoman Mary Hungerford (d. 1533) was a freeholder of the manor. (fn. 198) Telling's daughter Elizabeth married John Read and through her the capital messuage, Neal's (Paynel's) farm, and certain lands passed to the Read family and became known as Read's tenement. The location of the farm and tenement are not known. (fn. 199) However, Reads tenement descended in the Read, Watts and Bathe families, with a tenement called Scissells or Richards from 1783. (fn. 200)

GASCRICK

The quarter of Adam of Purton's estate inherited by Catherine and Sir John Paynel in c. 1266 passed in turn, after Sir John's death in 1275, to their sons John (d. 1287) and Philip (d. 1299). (fn. 201) It passed to another John Paynel, and on his death in 1334 to his daughter, Elizabeth, wife of Richard le Gascrik. (fn. 202) Elizabeth and Richard sold part of the estate, 106 a. in Braydon forest, to John de Barton and John de Melton, who sold it to Henry, earl of Lancaster and Derby in 1342. (fn. 203) Elizabeth subsequently married Thomas of Fulnetby. After she died in 1373, William of Gascrick successfully sued John of Fulnetby for reversion of her quarter of Purton manor. (fn. 204) Gascrick manor was leased to Nicholas Wotton, and Edmund Gascrick sold it to him and Edmund Dauntsey in 1422. (fn. 205) Still held by Nicholas Wotton in the 1430s, (fn. 206) by 1514 it was re-united with the manor of Purton Poucher under the ownership of Sir Marmaduke Constable. Gascrick manor reverted to the Crown in 1539 and seems to have become the property of the duchy of Lancaster. (fn. 207) In the later 16th and early 17th centuries the Hungerford family claimed lordship of Purton Wootton, (fn. 208) as did Anthony Ashley in 1617, when the manor was among the holdings he assigned to his daughter and her husband John Cooper. (fn. 209)

OTHER ESTATES OF MEDIEVAL ORIGIN

Pavenhill

The estate, which was based in the south of the parish and which by the later 15th century had become the reputed manor of Pavenhill, may have originated in a mill and three hides in Purton held by Walerand of Blunsdon before 1241. (fn. 210) In the later 13th century other members of the Walerand family held land in the parish. In 1275 Nicholas Walerand encroached on the highway at Restrop and Hoggs Lane, and in 1276 John Walerand had a house at Pavenhill. (fn. 211) By 1281 Waleran's sons, Nicholas and John had both inherited lands in Purton from their father. (fn. 212) In 1332 William Walerand, parson of Leigh, had a house and a ½ virgate of land in Purton, (fn. 213) and Adam Walerand, who held an estate centred on Broad Blunsdon, was one of Purton's wealthier residents. (fn. 214) Two hides of land at Pavenhill were part of an estate held by Thomas Walerand in 1348, (fn. 215) and later by William Walerand, who died in 1369. William's heir was his nephew Gilbert of Shotesbroke, son of his sister Joan. (fn. 216) In 1428 John de Shotesbroke owed ½ knight's fee for Purton lands, as tenant of the Abbey. (fn. 217) Thomas Rogers held the manor from Malmesbury abbey in 1488, when it descended to his daughter Elizabeth and her husband William Essex. (fn. 218) They remained in possession when the abbey was dissolved. In 1550 it passed to their son Thomas, who leased it to Vincent Godard and his wife Elizabeth in 1557, (fn. 219) and then sold it to John Sadler in 1583, when it was said to include Malfords. (fn. 220) Thomas Sadler sold some of the lands to William Holcroft (d. 1632), and some to William Read in 1616. (fn. 221)

Malreward (Malfords)

In 1242 Robert Malreward owed military service of 1/8 knight's fee. (fn. 222) Thomas Malreward held 1½ hides of land in Purton in the 1290s, (fn. 223) which passed to Robert Malreward by 1332, (fn. 224) and was held by the heirs of John Malreward in 1428. (fn. 225) The estate may have become part of the Walerand family's estate at Pavenhill, which John Sadler purchased in 1583. (fn. 226)

Restrop

Denise of Radestrop was a free tenant in 1323, and her son Thomas in 1353 was granted licence to hold the estate for his life and that of his son. (fn. 227) This holding may have become the Restrop estate in the south of the parish which belonged to John Diggs (or Dix) in 1576. (fn. 228) By 1588 it had passed to his son Edmund Diggs and his wife Elizabeth, the sister of Lionel Cranfield (earl of Middlesex from 1622), who still held the estate in 1609. (fn. 229) The estate passed from Edmund Diggs, owner in 1609, to his brother Giles. He sold it to his nephew William (d. 1640), who bought lands from Richard Diggs and others to add to the estate, which passed to his son Richard. (fn. 230) In 1719 Anne, widow of Toby Richmond was tenant of the estate, which consisted of c. 300 a., (fn. 231) owned by Richard Diggs in 1738. (fn. 232) In 1744 the estate was occupied by Dr Frampton. (fn. 233) Richard Francome (1736–1797), who came to Purton c. 1760, may have had an interest in the estate, as might his sons John Francome (1767–1814) of Restrop farm and Richard Francome of Constables farm. (fn. 234) When added to the Shaftesbury estate it was known as Framptons, and the mansion with c. 200 a. was let to tenant farmers. (fn. 235) The estate and mansion were sold by Lord Shaftesbury some time after 1892. (fn. 236)

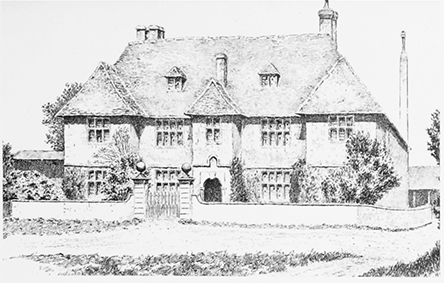

Restrop House

Built c. 1600, probably by Edmund

Diggs (fl. 1588–1609) on the site of an earlier house, (fn. 237) in

1641 it was described as a mansion house called

Restrops Place. (fn. 238) The main block is E plan, of limestone

rubble, with two storeys, an attic floor, a part cellar, and

mullioned and transomed windows. Wings project at

the rear: a north-eastern wing, containing a fine dog-leg

staircase, was extended during 17th or 18th century by a

two-storey service block, and a north-western wing was

added c. 1912, when the central chimney was probably

removed. (fn. 239) Over the porch entrance are carved the arms

of the earls of Shaftesbury of the mid 18th century. The

house was known then as Frampton's Great House, (fn. 240)

and it may have been about that time that the hipped

stone slate roof was added to modify an originally

gabled facade. It was subsequently occupied by two

families of gentlemen farmers, the Large family from

1789, (fn. 241) and c. 1813–92, the Warman family. (fn. 242) In 1912

Restrop House was bought by Lieut. Col. Canning

(d. 1960), who extended and restored it. (fn. 243) Main rooms

have moulded stone fireplaces, one with a carved

wooden overmantel.

42. Restrop House, probably built by Edmund Diggs c. 1600, altered in the 18th century, and depicted before being restored and extended in 1912 by Lieut. Col. Canning.

Rectory Estate

Malmesbury abbey took over direct management of the rectory estate when it appropriated it in 1276. (fn. 244) The location of the rector's curia or manorial site is unknown, but it was presumably near the church and hence after 1276 it may have been absorbed into the abbey's manorial site which also lay nearby. The rectory estate was leased together with the abbey's demesne manor in 1515. (fn. 245) At the dissolution it was acquired, with the demesne manor, by Edmund Bridges (d. 1573), and descended with the Bridges' Purton Keynes estate. (fn. 246) In 1609–10 it was sold, with the advowson of Malmesbury church, to Anthony Ashley (d. 1628), and descended with the Shaftesbury estate. (fn. 247) The income from the rectory, or parsonage, and the tithes was £150 2s. in 1729 and had risen to £239 13s. 10½d. in 1771. (fn. 248)

Bentham

A freehold estate, dependent by 1249 on the keeper of Braydon forest's manor of Chelworth (in Cricklade), (fn. 249) Bentham included two moated, and therefore highstatus, sites, also Temple close, a valuable pasture adjoining Braydon forest. (fn. 250) Presumably it was retained by the Keynes family, after the sale of the keepership and its Chelworth manor to the Despensers in 1300, and descended with Purton Keynes manor to be sold by Gray Bridges after 1609. (fn. 251) By 1640 a farmhouse called Benthams belonged to Thomas Shayle. (fn. 252) At some point it was acquired by the Cooper family, earls of Shaftesbury, and descended to Cropley Ashley Cooper, (d. 1851), who sold it to Samuel Sadler (1782–1845) in 1825. (fn. 253) It descended thereafter with the Sadler estate until this was dispersed by sales c. 1950. (fn. 254)

Bentham Farmhouse

Situated in Purton Stoke, it

was built on a raised site in the mid 18th century or

earlier. (fn. 255) The barn and stable complex with attached

pigsties date from the time of the 1825 sale. (fn. 256) In the mid

19th century, the farmhouse was rebuilt with some

pretension as Bentham House by the Sadler family, but

it retains elements dating back to c. 1750. (fn. 257)

Pond Farm

A high-status medieval moated site, (fn. 258) it was the centre of an estate held by the Bathe family from c. 1640, (fn. 259) until the mid 18th century. (fn. 260) It was inherited from his brother Richard by William Bathe (vicar 1664–1715), and passed to his son William Bathe, who left it to his great nephew, William Maskelyne (d. 1772). The house was the country retreat of Revd Dr Nevil Maskelyne (1732–1811, Astronomer Royal from 1765). (fn. 261) After his death the furniture was taken to his family's main seat at Bassett Down. (fn. 262) Thereafter Pond Farm was occupied by tenant farmers. The house and farm descended with the Maskelyne (Purton Down) estate until its sale in 1928. (fn. 263)

43. Pond Farm on a medieval moated site. The taller part is late 16th century, the gabled section of c. 1600.

Pond Farmhouse

A much altered house of irregular

plan stands within the moat. Built of limestone rubble,

the southern end of the main range has two full storeys

and a steep stone-tiled roof with coped parapet to the

north gable end. The east front facing the road has on

the ground floor mullioned and transomed windows

under relieving arches, which together with internal

details suggest a building erected during the late 16th

century. The lower northern end of the house was built

c. 1600 and has two gabled bays and one surviving

mullioned window. The house was remodelled with

sash windows inserted c. 1800, but major alterations

ceased after Maskelyne's death in 1811. An early 18thcentury rubblestone stable with half-hipped stone slate

roof adjoins the house at right angles. To the north is a

cowshed built of coursed squared stone c. 1903 in Arts

and Crafts style. (fn. 264)

Other high status freehold sites

Nicholas de Baddebyr, a knight, held a 2-virgate freehold estate in 1250, perhaps at Bagbury. (fn. 265)

The moated site at Widham, occupied in the later Middle Ages, (fn. 266) suggests premises of high status. Widham farm, built in c. 1600, (fn. 267) was a possession of the earls of Shaftesbury in the 19th century.

ESTATES OF LATER ORIGIN

With the fragmentation of the medieval manors a number of new landowning families emerged, including some drawn from established tenants, who by purchases in 1609 and subsequently accumulated freehold estates in Purton.

Hungerford estate

In the 16th and 17th centuries the Hungerford family held lands centred on Purton Stoke, as part of wider property interests in the area. (fn. 268) Anthony Hungerford (d. 1558), of Down Ampney (Glos.), (fn. 269) acquired various lands in Purton. (fn. 270) A freehold in the manor of Purton Poucher passed with the manor of Chelworth Poucher, Cricklade from his kinswoman Mary Hungerford (d. 1533). (fn. 271) In 1554 he purchased 300 a. in Purton Poucher, (fn. 272) and leased Temple close, Bentham, from the duchy of Lancaster. (fn. 273) Lordship of the manors of Purton and Purton Stoke passed to his son John (d. 1582), (fn. 274) and a claim to the lordship of Purton Wootton manor. (fn. 275) The property apparently passed with Chelworth Poucher down the Down Ampney Hungerford line. (fn. 276) Temple close was subsequently held by John Ernley who sold it to Anthony Hungerford (d. 1627), of Black Bourton (Oxon.). (fn. 277) It was still owned by one Mr Hungerford in c. 1650. (fn. 278)

Shaftesbury estate

A major purchaser in 1609 was Anthony Ashley (d. 1628) of Wimborne St Giles (Dorset), who from 1596 had owned land in Purton which formed part of an estate in Lydiard Millicent. (fn. 279) He acquired from Lord Chandos the Rectory estate and property belonging to the manors of Purton and Purton Keynes. (fn. 280) In 1617 Ashley assigned certain lands to his daughter Ann (d. 1628) on her marriage to John Cooper (d. 1631). These included Purton manor house and parts of Purton Great Manor and Purton Wootton (Poucher). (fn. 281) This estate passed to their son Sir Anthony Ashley Cooper (Baron Ashley from 1661, 1st earl of Shaftesbury from 1672, d. 1693), (fn. 282) and descended with the title earl of Shaftesbury in the direct line through four generations, all named Anthony Ashley Cooper (d. 1699, 1713, 1771, 1811), and then to a brother, Cropley Ashley Cooper, 6th earl of Shaftesbury (d. 1851). (fn. 283)

Some time before 1759 parcels of land belonging to Anthony Wheelock were added to the estate, and around the same time Restrop was acquired. By 1800 the Shaftesbury property had reached its greatest extent of over 1,250 a. (fn. 284) In 1824–5 the 6th earl sold around half the estate, including Wells farm, Bentham farm, Common farm, Flaxmore, or Haxmore, farm, and Sparcells farm, part of which lay in Purton and part in Lydiard Millicent. (fn. 285) The reduced estate, which included Manor farm, Restrop farm and Widham farm, descended with the title to Anthony Ashley Cooper, 9th earl of Shaftesbury, who offered the remaining 620 a. for sale in 1892, much of it divided into small building plots. (fn. 286)

Hyde estate

In 1609 Nicholas Hyde had an interest in another portion of Purton manor, presumably acquired from Lord Chandos. (fn. 287) His brother Henry Hyde (d. 1634) bought an estate at Purton and moved his family there from Dinton c. 1623–5. (fn. 288) Henry's son, Edward Hyde (1609–1674, earl of Clarendon from 1661) recuperated from serious illness at Purton in 1625–6; (fn. 289) although it has been suggested that Edward's daughter Anne (1637–71), future wife of James II, may have been born there, she was probably born in Windsor (Berks.). (fn. 290) On account of Hyde's Royalist allegiance, the estate was heavily taxed by Parliament in 1646, (fn. 291) but remained the property of the Hyde family in 1665. (fn. 292) The Hydes sold the estate to Sir Charles Duncombe in 1708, and it was ultimately purchased by George Clarke in 1718. (fn. 293)

In 1739 George Clarke, fellow of All Souls College, Oxford, became Worcester College's major benefactor, when he bequeathed his estate, which included College and Pavenhill farms, to endow six fellowships and three scholarships. (fn. 294) College farm was sold to the tenant farmer, Charles John Iles (d. 1945), in 1906, although the College retained the house until 1964. (fn. 295) Iles bought Pavenhill farm in c. 1912. (fn. 296)

College Farmhouse

The Purton premises of the

Hyde and Clarke families was bequeathed to Worcester

College, Oxford, in 1739. An early 17th-century arched

gateway contemporary with the house was the original

approach from High Street. The two-storey house with

pitched roof and end chimneystacks is L plan, with a

symmetrical east front of five bays, and a central gabled

porch, on which the date 1754 is scratched; the two-light

mullioned windows with hoodmoulds have been

modified and the attic dormers added. The central

entrance lobby, with stairs to the rear, is flanked by

reception rooms. (fn. 297) In the early 17th century the parlour

was fully panelled, and the stone fireplace, possibly

later, has an elaborate wooden overmantel dated 1626,

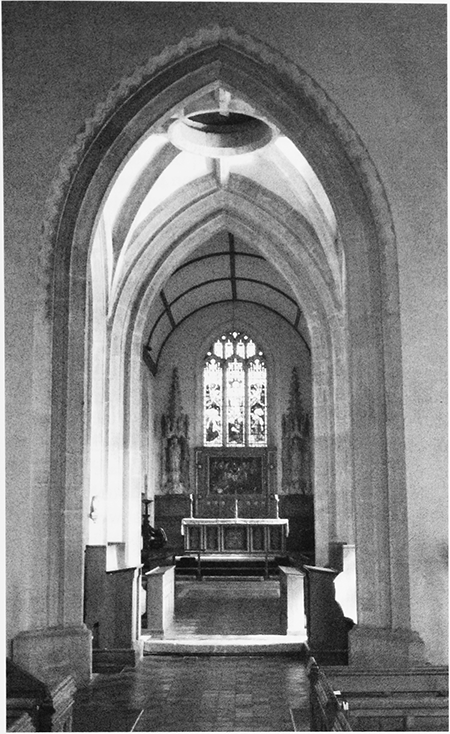

carved with the coat of arms of Amy Sibell (d. 1606), the

mother of Henry Hyde (d. 1634). (fn. 298) A similar overmantel

on the first floor has different arms. Attached to the

north end of the house is another dwelling of 1½ storeys,

built in the late 16th or early 17th century and later used

as an outbuilding; it retains a large stone fireplace in the

central bay of three. A brick granary in the farmyard

was built in 1759. (fn. 299) The college retained possession of the

house after the land was sold off in 1906 to its tenant,

Charles Iles, who undertook repairs and modernization;

it was further restored by subsequent owners. (fn. 300)

Maskelyne (Chamberlains) Estate

Members of the Maskelyne family held land in and around Purton in the later 1400s, (fn. 301) and in 1576 Robert Maskelyne (fl. 1551–76), was one of Purton's wealthier inhabitants. (fn. 302) His son Henry (d. 1640), greatly enlarged the estate when he bought Purton manor lands from Lord Chandos in 1609. These included Chamberlains, Ayleford mill, and lands at Westmarsh. Chamberlains, which lay in Church End, was presumably a substantial house or estate in the Middle Ages since, as its name implies, its rent supported the abbey's chamberlain. Presumably it had been acquired by Bridges together with the main manorial site in 1544. The enlarged estate passed to Henry's son William (d. 1649), and to his son Henry, who died without heirs in 1667. Chamberlains and other lands were sold to Francis Goddard in 1669. (fn. 303)

Francis Goddard (d. 1701), was succeeded by his sons Edward (d. 1710), and Anthony (d. 1725), and his grandson Richard Goddard MD (d. 1776). (fn. 304) In 1792 Richard Goddard's only daughter Margaret (d. 1843), married Capt Robert Wilsonn RN (d. 1819), and had four daughters. (fn. 305) Capt Wilsonn's estate included Ridgeway farm, 193 a. and land in neighbouring parishes. (fn. 306) In 1824 Sarah, his eldest daughter, married Richard Miles (d. 1839), who purchased Purton House from his wife's family in 1829. (fn. 307) In 1840 Sarah Miles sold Purton House with grounds of 30 a. and other lands to a cousin, Horatio Nelson Goddard. In 1843, after Margaret Wilsonn's death, her daughters Isabella and Emma sold their portion of the estate, Ridgeway farm, a mill and a stone quarry, (fn. 308) and Horatio Nelson Goddard sold his portion and Purton House and grounds, to Major Elton Mervyn Prower, the son of John Mervyn Prower (d. 1869), vicar of Purton. (fn. 309) 1878 the Prower family sold the estate to Sir Charles Brooke, 2nd Rajah of Sarawak. (fn. 310) He let the house to the Russell family, who bought the estate in 1899 and sold it to Capt. Arthur Percy Richardson c. 1908. (fn. 311) In 1931 it was bought by William Wilson Fitzgerald, and passed to Col. Francis Wilson Fitzgerald in 1935, and to his son, Lieut. Col. William Wilson Fitzgerald, who sold the estate in lots in 1976, (fn. 312) when Purton House and 38 a. was bought by Mr and Mrs Barker. (fn. 313)

Chamberlains (Purton House)

The Maskelyne

property, sold to Francis Goddard in 1669, was called

Chamberlains in the 16th and 17th centuries and

Church End house by 1800. (fn. 314) Richard Goddard (d.

1776) modernised the house, laid out the grounds and

made an ornamental lake from the medieval

fishponds. (fn. 315) A contemporary drawing of the house

survives from around this time. (fn. 316) In the early 1800s,

Robert Wilsonn (d. 1819) undertook substantial

building work on the house, (fn. 317) after which it had four

reception rooms, four main bedrooms and a sitting

room, six servants' bedrooms, servants' quarters, a

service wing, cellar and gardener's room. (fn. 318) Between 1829

and 1839 Richard Miles replaced that house with the

present symmetrical three-bay house, faced with finely

dressed ashlar, and created new offices, coach houses

and stables. A new western entrance façade was made,

and a central porch, with ionic columns in antis,

superseded the previous eastern entrance. Parts of the

previous building were incorporated into the internal

structure. (fn. 319) By 1839 when the property was again to let,

it was known as Purton House. (fn. 320) Major Prower added a

servants' wing with offices below in 1863. (fn. 321)

Maskelyne (Purton Down) Estate

A second branch of the Maskelyne family also held land in Purton. (fn. 322) In 1576 George Maskelyne (d. 1582), younger brother of Robert Maskelyne (fl. 1551–76), owned a small estate at Purton Down. (fn. 323) His son Edmund (d. 1630) greatly enlarged the estate by buying lands at Westmarsh from the Dodeswell family in 1598; Malfords and other Purton manor lands from Lord Chandos in 1609; (fn. 324) and an estate at Bentham from the Ware family in c. 1613. (fn. 325) Edmund's son Nevil (d. 1679), (fn. 326) inherited the estate and passed it to his grandson Nevil (d. 1711), of Westmarsh, Purton. (fn. 327) His son Nevil (d. 1774), sold the property at Westmarsh and rebuilt Down farmhouse at Purton Down for himself. (fn. 328) Nevil's brother Edmund had three sons and a daughter, Margaret, afterwards Lady Clive. (fn. 329) Edmund's eldest son William (d. 1772), inherited Pond farm, Purton Stoke, from his great-uncle, William Bathe. (fn. 330) In 1763 Edmund's second son, also Edmund (d. 1775), bought an estate at Bassett Down in Lydiard Tregoze, now Wroughton parish, which became the family's main residence. (fn. 331) The third son Revd Dr Nevil Maskelyne (d. 1811) outlived his brothers to inherit the estates at Bassett Down and Purton, which included Pond Farm, his country residence. (fn. 332) The estate passed to his daughter, Margaret (d. 1858), and her husband Anthony Story, who took the name Story-Maskelyne, then to their son Mervyn Story-Maskelyne (d. 1911), and to his daughter Mary and her husband Hugh Arnold-Forster. (fn. 333) Mervyn Story-Maskelyne added more property to the estate, including Restrop farm in 1876. (fn. 334) Mary Arnold-Forster offered the Purton estate for sale in 1928, when it covered 608 a. and included Restrop farm, Pond farm, Down farm and Brockhurst wood. (fn. 335)

Sadler Estate

The Sadler family were wealthy yeomen and the tenants of a former estate of Tewkesbury abbey (Glos.), which included lands in Purton in 1555. (fn. 336) In 1583 John Sadler bought the reputed manor of Pavenhill from Thomas Essex, (fn. 337) and Thomas Sadler sold some of the lands to William Holcroft (d. 1632), and William Read. (fn. 338) Some family members made money in international trade, (fn. 339) and the family either owned or leased significant amounts of land in the parish. (fn. 340) In 1799 James Sadler was among the wealthier farmers in the parish, (fn. 341) and in 1815 John Sadler had an estate of c. 140 a. in Purton Stoke. (fn. 342) Samuel Sadler (d. 1845) of the Court, now Purton Court, became one of the largest landowners in the parish when he bought part of the Shaftesbury estate in 1825, which included Bentham farm. (fn. 343) By 1838 he owned an estate of 193 a. based on Bentham House; he also owned Wells farm, Purton Stoke, another 50 a.; and farms in the east of the parish, Haxmore farm, 100a. and Pry farm, 104 a. (fn. 344)

Bentham farm, with Bentham House, passed to his eldest son William James Sadler (1804–70), (fn. 345) and then to William's daughter Caroline, (fn. 346) wife of Col. Thomas Heycock. (fn. 347) Other parts of Samuel's estate passed to his younger son, Dr Samuel C. Sadler. His son, James Henry Sadler (1843–1929), of Lydiard House, Lydiard Millicent, known as the 'squire of Purton', added to the estate in 1892 when the rest of the Shaftesbury estate was sold. (fn. 348) When the Maskelyne estate was sold in 1928 he purchased Pond farm, Purton Stoke, 157 a. (fn. 349) Among the other farms he owned in 1910 were New farm, Bentham, 59 a.; and Mill farm, 73 a.; (fn. 350) and in 1941 Fox Mill farm, and Bagbury Green farm, 53a., (fn. 351) also Hayes Knoll farm, and lands in Lydiard Millicent. In c. 1950 all his properties were offered for sale to the sitting tenants, before they were sold on the open market. (fn. 352)

Other members of the Sadler family owned land in Purton. Thomas Sadler bought Blakehill farm in 1826, 143 a. on the northern arm of the parish, (fn. 353) and following his death, it was sold in 1871. (fn. 354) Ann Sadler owned Ridgeway farm, Church End. (fn. 355)

Purton Court

The handsome house at 3 High

Street was built in the mid 18th century perhaps to

replace an earlier house. Because the site slopes down

from the street, there are two storeys at the front and

three at the rear. The main five-bay south front is

terminated by ashlar pilasters, has windows with raised

ashlar architraves and keystones, and a Tuscan porch. A

rear block was added in the early 19th century, and the

west, garden front was remodelled. (fn. 356) 'The Court' was

the home of Dr Samuel C. Sadler (d. 1889) and his son

James Henry Sadler (1843–1929), who owned large

portions of the parish. From c. 1890 it was let to tenants

and sold after James Sadler died. In the 20th century it

had several owners and after falling into decay it was

renovated in the early 21st century. (fn. 357)

Bentham House

Bentham farmhouse was rebuilt

for the wealthy Sadler family c. 1850–2 in 'vigorous early

Victorian gothic style', with ashlar facing, a display of

bay windows and gables with carved barge boards, and

internal fittings in the same style. (fn. 358) A single-storey

carriage house of limestone rubble dates from the same

period. Service wings at the rear preserve several earlier

phases of building dating back to c. 1750. (fn. 359) Additions

were made in 1867 by a Swindon architect, Thomas

Smith Lansdown, (fn. 360) and a billiard room was added in

1903. (fn. 361) Bentham House and 25 a. descended to Caroline

Sadler and her husband Col. Thomas Heycock (d.

1931), (fn. 362) and was used after 1939 as a centre for evacuees.

In the 1950s the land was sold to the tenant farmer,

Leonard Scott, and the house became a preparatory

school for boys. (fn. 363) Later uses have included dog

breeding, (fn. 364) and as a centre providing music therapy to

handicapped adults. (fn. 365)

Bathe Estate

By the later 16th century the Bathes were a wealthy yeoman family, (fn. 366) tenants of Purton Keynes manor, where Richard was succeeded by his son William (d. 1610). (fn. 367) Another son, Anthony, was a tenant of Malfords at Pavenhill. (fn. 368) The family also held the Pond farm estate from c. 1640, (fn. 369) until the mid 18th century. (fn. 370) Inherited by William Bathe (vicar 1664–1715), it passed to his son William Bathe. By then, this William could be described as a gentleman, (fn. 371) and was one of Purton's wealthiest residents in 1738. (fn. 372) Anthony Bathe (d. 1769), yeoman, left a substantial landed estate to his sons William, John, James and Anthony and a malthouse to Richard; his children also received a legacy in 1777 from their maternal grandfather Richard Garlick of Wroughton. (fn. 373) John and Anthony Bathe were among Purton's wealthiest residents in 1799. (fn. 374)

The family began to build up a freehold estate, centred on High Street, in the early 19th century, when in 1823 Richard Garlick Bathe and William Bathe purchased a capital messuage called Read's tenement, originally part of Purton Poucher manor, and a tenement called Scissells or Richards from Richard Read. (fn. 375) In 1838 Richard Garlick Bathe farmed Purton Manor farm, 356 a., and the vicar's glebe, 46 a., and he owned Spring Grove farm, 159 a. west of College farm, (fn. 376) and in 1840 a large house called Hallidays, occupied by the Misses Bathe. (fn. 377)

The Bathe family estate passed to the Brown family through Richard Garlick Bathe's daughter Sarah, wife of John Brown. (fn. 378) By 1910 the Brown estate included Blacklands farm, 135 a. (fn. 379) It also included the hospital and other properties in Purton village purchased by William Brown, and Blake Hill farm, 139 a. purchased by John Brown (d. 1920). After John Brown's death his executors sold off the estate piecemeal. (fn. 380)

ECONOMIC HISTORY

Agriculture was the main occupation of Purton's inhabitants until the 19th century. Arable crops were cultivated on pockets of stonebrash soil and in other parts of the parish in the Middle Ages. Extensive pasture and meadow on the heavy clays supported livestock and dairy farming. Cattle and sheep were being reared for the London market by the early 1600s. (fn. 381) After the coming of the railway in the mid 19th century, many small dairy farms grew up to supply liquid milk for doorstep delivery in London and Birmingham. In the later 19th century Swindon railway works offered employment to Purton's inhabitants, and in the later 19th and 20th centuries small industries developed within the parish.

AGRICULTURE

Before inclosure

In 796 there were 35 manentes of cultivated land at Purton, corresponding to 35 hides recorded in 1066. In 1086 there was enough land for 24 plough teams. Malmesbury abbey had two plough teams and five slaves to work its demesne lands of 21½ hides. A further 20 households of villeins, 12 of bordars and 13 of cottars had 19 plough teams between them. (fn. 382)

Little is known of the abbey estate's administration, but in 1275 Geoffrey of Purton served as reeve. (fn. 383) The annual income of the demesne manor was valued at £18 in 1291 and the manorial site and the demesne were farmed out at for £23 p.a. in 1515. In the 1530s, the total annual value of the abbey's estate, including customary rents and the farm was put at over £52 and in 1541 when it was in the king's hands it was valued at over £60. (fn. 384) In 1547 mixed farming was practiced on the demesne farm; corn was grown, cattle, goats and poultry were reared and the farm buildings included a dove house, a wool store and a malt loft. (fn. 385) Some tenants may have farmed their holdings from premises near the church and along the High street. Farmsteads belonging to free tenants lay to the south at Restrop (fn. 386) and Bagbury, (fn. 387) and probably to the north at Down farm. (fn. 388)

Arable

The stonebrash soils of the Corallian

ridge were suitable for arable cultivation and this is

probably where the manorial demesne and most

medieval farmsteads lay. (fn. 389) In the late 13th century, 61 a.

of arable land was cultivated as part of the lord's

demesne of Purton Keynes manor, (fn. 390) and Purton Paynel

manor had 64 a. of demesne arable. (fn. 391) In 1349, Purton

Paynel had 40 a. of demesne arable, (fn. 392) which had shrunk

to 23 a. by 1405. (fn. 393) The size of the abbey's own demesne

arable is unknown, but the valuations suggest it was

considerable, perhaps 200 acres or more.