A History of the County of Somerset: Volume 10. Originally published by Boydell & Brewer for Victoria County History, Woodbridge, 2010.

This free content was digitised by double rekeying. All rights reserved.

'Introduction', in A History of the County of Somerset: Volume 10, ed. Mary Siraut (Woodbridge, 2010), British History Online https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/vch/som/vol10/pp1-13 [accessed 23 April 2025].

'Introduction', in A History of the County of Somerset: Volume 10. Edited by Mary Siraut (Woodbridge, 2010), British History Online, accessed April 23, 2025, https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/vch/som/vol10/pp1-13.

"Introduction". A History of the County of Somerset: Volume 10. Ed. Mary Siraut (Woodbridge, 2010), British History Online. Web. 23 April 2025. https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/vch/som/vol10/pp1-13.

In this section

Introduction

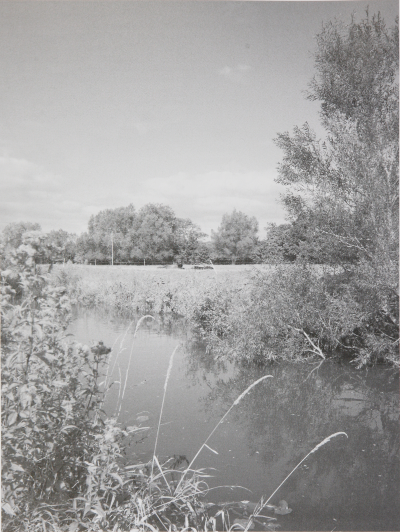

1. The River Cary at Babcary

THE NORTHERN part of Catsah hundred occupies a Jurassic landscape of fossiliferous Lias, forming a watershed between the Brue and Cary rivers. The area covers c. 12,000 a. (c. 4,900 ha.), divided between ten ancient parishes, including the tiny parish of Wheathill, anciently in Whitley hundred but included in this volume. Castle Cary lies in this very rural area and there are no obvious landmarks or features to interest those who see the countryside only from an express train on the main line between Taunton and London. Apart from the former milk factory chimney at Castle Cary station the only sign of industry or commerce evident to the traveller is the railway itself. For much of its length across the area it is alternately embanked or in cuttings and dominates small communities like Wheathill, Lovington, and Clanville. Even Castle Cary's industrial buildings are hidden and the great chimney at Higher Flax mills, now demolished, did not intrude into views of the town. The impression the area makes on the visitor is one of a rolling landscape consisting of villages and farms surrounded by a patchwork of fields with many fine hedgerow and specimen trees.

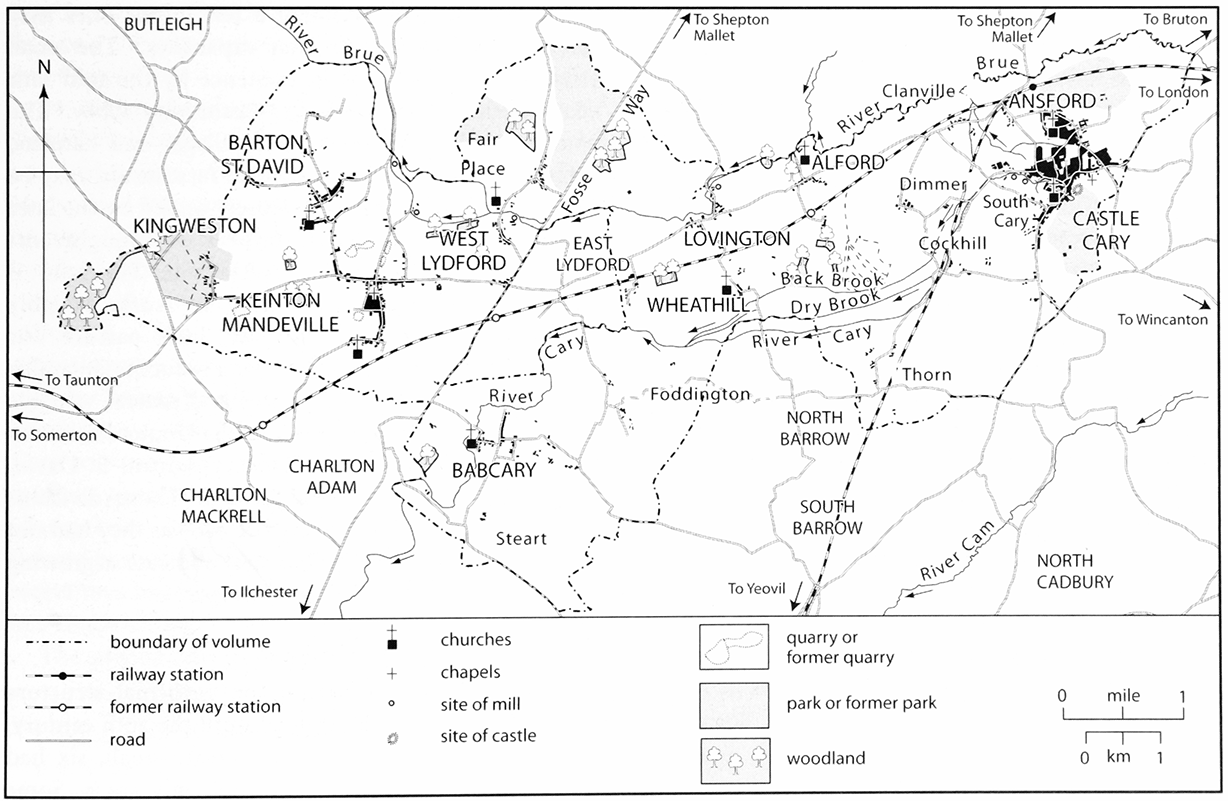

2. Castle Cary Area 2000

The Castle Cary area in 2000 is crossed by several major lines of communication, including the Roman Fosse way and the London-Penzance railway line. The parishes are of modest size and often contain several settlements. The area is well watered by the rivers Brue and Cary and their tributaries, and there are still pockets of woodland and parkland.

To the west and east the land rises to hills, which close the view, as do the lower ridges to north and south. In the centre undulating land, rarely exceeding 61 m. (200 ft.), separates the two rivers while in the east a large area of former marsh surrounds the infant river Cary and its tributary brooks. The Brue flows along the northern boundary of the hundred except at West Lydford where the parish straddles the river. The river Cary rises in Castle Cary and runs west and south through the southern part of the area. Half the parishes take their names from the Cary or fords through the Brue. The highest ground is Lodge Hill (154 m. (506 ft.)) in Castle Cary on the boundary with Bruton hundred, an island of golden Oolite in the otherwise grey Lias. In the extreme west of the area a well-wooded ridge of Rhaetic clay (100 m. (328 ft)) forms a visual and geographical barrier between the Brue valley and King's Sedgemoor. The visible high points outside the area are Glastonbury Tor (159 m. (521 ft)) 11 miles north-west and South Cadbury hill fort (153 m. (502 ft)) 6 miles south of Castle Cary. (fn. 1) The area contains two contrasting Sites of Special Scientific Interest; Copley Wood on the ridge south of Kingweston and a rich natural meadow by the Cary in Babcary. (fn. 2) The area is also home to the Carymoor Environmental Centre. (fn. 3)

EARLY SETTLEMENT

There is little evidence of the prehistory of the area apart from round barrows at Babcary. (fn. 4) However, given that it is a favourable area for settlement and that it was bisected by the Roman Fosse way, the lack of evidence is probably due to lack of systematic archaeology. A Roman villa has been uncovered at Dinnington only a few miles to the south. In the east housing development at Ansford and Castle Cary in the late 20th century revealed Bronze and Iron Age features as well as evidence of Romano-British activity especially at the site of the former manor farm in Castle Cary. (fn. 5)

Two historic roads quarter the area, crossing in West Lydford, but none of the original centres of settlements lay on them indicating that the roads were long distance routes. From south-west to north-east, the Fosse Way, still a main road, ignores the topography and, apart from a short section in Babcary, still follows its Roman course across the area. The meandering Somerton– Castle Cary road runs roughly east–west along the watershed between the Brue and Cary rivers keeping close to the former river and may also predate the Anglo-Saxon settlement pattern.

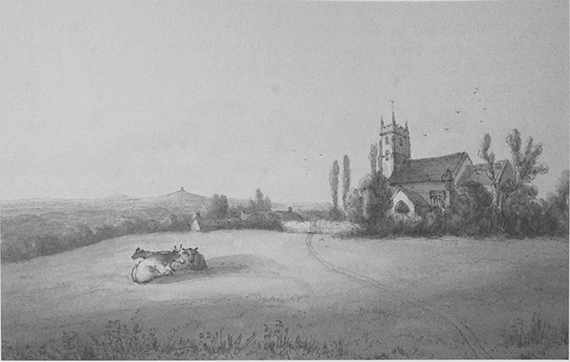

3. Ansford old church with view south-west to Glastonbury Tor, 1846. The church was demolished in 1860 and replaced on the site by the present church designed by C. E. Giles.

There is little evidence of church organization in the area before the Middle Ages but the existence of early Christian sites at Glastonbury, Wells, and Sherborne probably implies that Christianity was well-established in the area. All the major settlements were in existence by the 11th century although a few minor ones may result from medieval or later expansion. (fn. 6) The small estate of Wheathill was in existence by the mid 10th century when it was given to Glastonbury abbey. (fn. 7) The pattern of closely spaced small villages and hamlets, some of the latter possibly divided farmsteads, may be Anglo-Saxon. The area was densely settled by the later 11th century with large numbers of ploughteams indicating extensive arable cultivation. The land is fertile but was said to be hard to work, possibly requiring more teams. However, little pasture was recorded and this may account for a reduction in arable by 1086. There was ample water and several valuable mills had been established. Before the Domesday survey some large estates such as Babcary, Barton St David, and Foddington had been divided. Those divisions probably happened shortly before 1066 as they had not acquired separate names and may indicate a growing number of knights to be provided for. (fn. 8)

THE MIDDLE AGES

During the medieval period the parochial structure assumed the pattern it retained until the 20th century. The parishes in the area were mostly small, six had fewer than 1,000 a. and Wheathill only 325 a. Some parishes contained several settlements, none more than 2 miles from another. By the late 12th or early 13thcentury every parish had a church except Wheathill, which does not appear to have had one until after 1291. Babcary had chapels of ease in its secondary settlements of Foddington and Steart. (fn. 9) Pre-Conquest or later estate division may account for the number of secondary settlements in parishes like Babcary and Barton St David sometimes consisting of two or three farmsteads. However, the dispersed settlements at Dimmer and Thorn in Castle Cary are probably the result of medieval expansion and clearance for agriculture, and later inclosure. Many single farmsteads resulted from inclosure or the later tendency to move farmyards out of villages. Many settlements appear more nucleated today because modern planning controls have preferred infill development on village orchards, paddocks, and other open spaces to expansion of the village 'footprint'.

Churchpaths and market ways linked the respective settlements. There was no obvious centre to the area and Castle Cary's market had no continuous history. Somerton, Ilchester, Glastonbury, and Bruton markets were also used as villagers attended the nearest or most accessible just as they do today. The area was not isolated nor was the population immobile. Men surnamed Babcary were at Castle Cary and Bristol in 1327 (fn. 10) and a man from Brabant lived in Babcary in 1436. (fn. 11) In 1559 a Babcary man was described as also of Dunster and Cornwall. (fn. 12)

In the medieval period the area formed part of Catsash hundred, a division of the county. Sheriff's and hundred courts were held, the former probably near Hadspen in Pitcombe, east of Castle Cary and the latter by the Sparkford–Castle Cary road. Although the hundred belonged to the Crown at this period, central control was weak and landowners exerted more influence. The tithing, the most local royal administrative unit, did not always coincide with the parish. Some parishes were so small they were administered with others such as Ansford with Castle Cary to form Caryland. Large parishes were divided into two or more tithings. (fn. 13) Because of its ownership by Glastonbury abbey before the Conquest, Wheathill formed part of the abbey's hundred of Whitley and was sometimes linked with Blackford and Holton parishes in a single tithing. (fn. 14)

The private administrative and judicial unit during the medieval and early modern period was the manor, which in this area usually consisted of a single parish as at Kingweston or less as in Babcary. There were no religious houses within the area, although Bruton and Glastonbury were nearby. Manors and estates were small; there were few large houses and most landowners were absentees. They included a number of religious communities; Bruton priory had estates in Foddington and Steart in Babcary; St John's hospital, Wells, held a large part of Keinton Mandeville; and Kingweston manor belonged to Bermondsey priory (Surrey). (fn. 15) Glastonbury, which had owned Wheathill before the Conquest, lost it before 1086 to Serlo de Burci. (fn. 16) The Lovels, major lords or overlords in the east of the area, spent at least some time at Castle Cary where they had their castle and later a house. (fn. 17)

Manor courts usually appointed the tithingmen who represented the community at the hundred court and acted as law enforcement officers. Those courts also elected officials such as haywards, moor reeves, and field supervisors to manage farming and draining and to police disputes and nuisances. Manors also maintained village pounds and at Kingweston a cage and a pillory. (fn. 18) Important courts such as those at Castle Cary, which also administered Ansford manor, met every three weeks in the 14th century, (fn. 19) and most manors had courts twice a year but few records survive. Although lords of small manors such as Steart in Babcary may not have held a court they demanded attendance from their tenants. Some small or divided estates such as Alford, Wheathill, or Keinton were probably administered from a larger manor. (fn. 20) Lovington and West Lydford were subject to the peculiar jurisdiction of the dean and chapter of Wells and the rector respectively. At Lovington the Wells chapter held both manor and spiritual courts for which the tenant paid. (fn. 21)

Castle Cary, like the rest of the area, was primarily agricultural during the Middle Ages and was probably controlled by the manor and its resident lords and then by farmers of the manor until the mid 17th century. Kingweston was probably dominated by the bailiff and tenants of Bermondsey priory; a 13th-century bailiff was accused of acting without permission of the prior. (fn. 22) West Lydford was a parish of wealthy tenant farmers, probably from an early date. It was highly taxed in 1327, when two of the 16 taxpayers paid 10s. (fn. 23)

The parishes were very much alike in terms of agriculture with common arable fields on the gentle slopes and meadows beside the rivers and streams. Many were relatively short of pasture, there was little rough grazing, and it may have been difficult to maintain the draught animals required for extensive arable farming. By the late 11th century there had been some loss of cultivated lands and ploughteams with a consequent fall in the value of most of the estates across the area but arable still predominated. Most demesnes had ample meadow and large quantities of woodland remained, especially at West Lydford and Castle Cary. (fn. 24) However, woodland and marshy areas were cleared for agriculture during the Middle Ages to provide arable, meadow, and pasture. By 1905 only Kingweston and Lovington recorded more than 100 a. of wood and Ansford and Castle Cary had lost all their 11th-century woodland. Apart from the wooded ridge west of Kingweston only a few small pockets of woodland survive and the well-wooded appearance comes from the many hedgerow trees. There were parks at Ansford, Castle Cary, and West Lydford cleared from woodland apparently in the late 13th century; parkland at Kingweston is an 18th-century creation. (fn. 25)

Lack of pasture in the medieval period, and therefore of sheep and wool, may account for the lack of evidence for cloth making in this area in the Middle Ages although there was a fulling mill at West Lydford in the later Middle Ages. (fn. 26) The medieval economy is poorly recorded but it appears to have been largely based on corn production. Five parishes had one or more mills in the 11th century and at least three of these sites retained a working mill until the early 20th century. Four mills were assessed at over 10s in 1086 and none at less than 5s. (fn. 27) Castle Cary appears to have had a corn market in the 13th century, although it lapsed later. West Lydford had a market from 1260 possibly until the mid 14th century. A fair, also established in 1260 was more successful and continued until the 19th century. The fairs granted to Castle Cary in 1468 had a more chequered history but one was still being held in the early 17th century. (fn. 28)

The density of settlement and the number of parishes is a possible indicator of prosperity. Although many of the churches have been rebuilt, the size of Castle Cary and the quality of surviving Norman work at Barton St David, the 13th-century tower at Lovington, and late medieval glass at Alford imply some degree of wealth. There are several modest houses of some quality including the medieval range at Lower Cockhill, Castle Cary and the medieval wing at Standerwick in Babcary. (fn. 29)

THE EARLY MODERN PERIOD

The area, apart from Castle Cary, appears to have been conservative and was scarcely involved with the major rebellions of the period. No-one outside Castle Cary was fined in 1497 (fn. 30) and the western rebels were only near Kingweston in 1549 because they had been chased there. (fn. 31) In 1685 only three rebels were reported, two who went missing from Babcary and a man from Lovington assumed to support the duke of Monmouth. (fn. 32)

One explanation might be the royalist sympathies of the area, for which it suffered during the Civil War. The parish churches of Castle Cary and Lovington were ransacked and damaged, the former c. 1643 when a surplice was stolen, the latter probably in 1645 by the New Model Army on its way from Sherborne (Dors.) to Bristol when the chalice was taken. However, the object of the perpetrators was probably theft rather than iconoclasm. (fn. 33) Clubmen, theoretically neutral and opposed to troops entering their localities, were active in the Castle Cary area. Several local people served and fought in the King's service and later many had to compound for their estates. (fn. 34) The sequestrator, Edward Curle, had a difficult time because of the 'extraordinary malignancy of the place' and was often opposed by local people especially at Babcary and Barton St David who continued to support their old landlords by removing crops and livestock. However, Curle was usually more than a match for them setting watch on the fields and tracking down cattle to distant markets and grazing. (fn. 35) Such sympathies may explain why tenants at Castle Cary were prepared to shelter Charles II after the battle of Worcester. (fn. 36)

It was at this period that religious dissent took hold in some parishes, although not all, and it was usually short-lived. Even where parishes were neglected by their incumbents, like Barton St David, nonconformity did not take hold before the late 18th century. In Alford the rector was ejected not only for his royalist sympathies but also for scandal, however, he continued to live in the parish. In West Lydford the 'pious scholar' appointed in the Interregnum continued in the living until 1689. Castle Cary was represented at a Presbyterian classis in the 1640s but the Presbyterian cause in the parish was short-lived. Castle Cary and West Lydford had several Roman Catholics in the 17th and 18th centuries and in the later 17th century there were small numbers of Quakers in several parishes. In general, however, it seems that the rural population was naturally conformist. (fn. 37)

The church still exercised civil and spiritual jurisdiction through church courts. The peculiars at Lovington and West Lydford remained in existence, held respectively by the canons of Wells and the rector. Their courts were concerned with the fabric and ornaments of the church, absenteeism, and matrimonial and probate business. Parish officers were sworn and made presentments of moral offences, non-payment of tithe, failure of the clergy to do duty, and repairs. (fn. 38)

There were early attempts at industrialization with the Castle Cary stocking industry but agriculture remained the main occupation. Farming in the area was mixed, and the villages and hamlets were set among open fields. However, inclosure of arable, meadow, and pasture usually took place piecemeal between the 16th and 18th centuries, although Alford, Keinton Mandeville, and West Lydford required parliamentary inclosure in the early 19th century. Most estates and farms were small and there are few records of land use during this period but arable crops appear to have predominated. Fairs were still held at Castle Cary and West Lydford, and Babcary also had a fair from the early 17th until the mid 18th century. (fn. 39) Seventeenthcentury trades included parchment making and gloving. (fn. 40) Alford achieved short-lived fame in the late 17th century for its purgative well whose waters attracted many visitors. (fn. 41)

The settlement of America encouraged many to leave the area for the new colonies. Henry Adams, ancestor of two American presidents, is said to have been born in Barton St David in the late 16th century, moved to Kingweston by 1622, and emigrated to America in the 1630s with several of his wife's relatives. (fn. 42) In the 1640s Robert Arnold of West Lydford was in Virginia. (fn. 43) A Babcary man had a son overseas in 1673. (fn. 44) The first recorded emigrant from Castle Cary was Gabriel Ludlow, baptised there in 1663, who landed in America in 1694. (fn. 45) A man of black African origin from Jamaica baptised at Ansford in 1732 was presumably a servant of a returning emigrant or plantation owner. (fn. 46) Men from Ansford were in Newfoundland in the early 18th century but probably intended to return home. (fn. 47)

THE MODERN PERIOD

The 18th and 19th Centuries

The coming of turnpike roads, several in 1753, opened up the area to both east–west and north–south traffic and several coaching routes were established, mainly through Ansford and Castle Cary. However, all these routes declined in importance with the rise to prominence, especially in the 20th century, of the rail line from Taunton to London via Castle Cary and the great west road to London further south. (fn. 48) The 1611 market way from Babcary to Bruton through North Barrow and Castle Cary was still useful enough locally for the section through Castle Cary to be turnpiked in 1778. (fn. 49) In the opposite direction the 18th-century market way from Foddington in Babcary, possibly to Ilchester or Somerton, was largely abandoned before 1839. (fn. 50) The greater use of carts, and later motor vehicles, concentrated traffic on the main roads and led many tracks to fall out of use. Improved roads enabled commercial enterprise to thrive as well as assisting the traditional marketing of agricultural produce and the development of industries such as textiles and quarrying, which depended on good transport. The survival of fairs at Castle Cary and West Lydford was probably due to their positions near major roads. The coming of the railways in the 1850s, when a station was built near Castle Cary, opened the area to new goods, distant markets, and better communications, although a proposed tramway of 1892 to link Castle Cary with the station, neighbouring villages, and the Keinton Mandeville quarries was never completed. (fn. 51) Brick, Welsh slate, and cement products imported into the area displaced Keinton (fn. 52) or Cary stone and thatch as the predominant building materials. Only in Castle Cary, which had a brickyard possibly from the late 18th until the early 20th centuries, had there been much brick building, and that largely for industry. (fn. 53)

Many of the parishes were gradually laid to grass from the 18th century and as in much of Somerset dairying predominated in the 19th and 20th centuries as corn growing declined. In 1801 wheat was still the most important crop produced on c. 800 a. over seven parishes. (fn. 54) Potatoes were grown on c. 195 a., mainly in the east, and beans (c. 155 a.) and peas (c. 80 a.) mainly in the west. There were also c. 160 a. of barley, c. 98 a. of oats and c. 75 a. of turnips. (fn. 55) There was still c. 3,700 a. of arable in the ten parishes c. 1840, (fn. 56) but only 1,613 a. by 1905 when there was over 9,800 a. of grass. (fn. 57) Agricultural improvements and experiments by the landowner were documented at Kingweston, but at Castle Cary improving farmers, notably college-trained George Wyndham Gray, James Mackie, and the Longman family, led to the parish being noted for its cheese in the 19th and 20th centuries. Orchards were also developed in the same period, mainly for cider production, and although most were destroyed in the later 20th century, new orchards have recently been planted at West Lydford. (fn. 58) The fragmented ownership and many small freehold farms probably led to a greater variety of crops such as potatoes and flax at Castle Cary and teasels at Babcary and Keinton Mandeville (fn. 59) which large landlords tended to discourage. Traditional mixed farming declined during the later 20th century but dairying remained important. More unusual produce included ice cream at Lovington and alpaca at Barton St David. (fn. 60)

4. Castle Cary, South Street, east side showing some of the variety of building styles and materials found in Castle Cary including local Cary stone. The raised pavement was created partly by lowering the road in the 18th century to improve the approach to the town.

Commercial exploitation of the lias in the west, notably in Keinton Mandeville and Kingweston, changed the face of the area. It produced stone for building and paving and for the distinctive narrow pavements and slab garden fences which can still be found in places like Keinton Mandeville, Kingweston, and West Lydford. The Keinton quarries were extensive and were managed on an industrial scale from the late 18th to the early 20th century producing not only walling, fencing, and paving, but also sinks, troughs, and tomb stones. (fn. 61)

The other major industry was the production of cloth and clothing. Stockings continued to be made in the area in the 18th century, mainly for Castle Cary hosiers. By then serge and linen were also produced in Castle Cary. Stocking making and serge weaving declined in the 19th century and attempts to develop silk making failed but the linen industry prospered in Castle Cary, as did horsehair weaving, begun in the 1830s. Both linen and horsehair factories were built in the town and horsehair continues to be woven there. By the late 18th century most food processing and industrial business was based in Castle Cary. The coming of the railway encouraged the development of new businesses such as milk processing and allowed existing businesses to expand. (fn. 62)

5. House in Keinton Mandeville built of Keinton stone. Keinton Mandeville's easily quarried lias was used extensively for local houses, walls, fencing and paving, but also supplied pavements for towns throughout the south of England.

The history of the market at Castle Cary shows cycles of success and failure but there were several fairs and many shops in the town by the end of the 18th century. Most villages had shops in the 19th century but apart from farm shops they only survive at Keinton Mandeville. Almost every settlement had at least one alehouse and there is evidence of travelling entertainment. The Ansford inn and some of those in Castle Cary had ballrooms and catered for the 'carriage trade'. Plays and concerts were performed at Castle Cary by the 18th century.

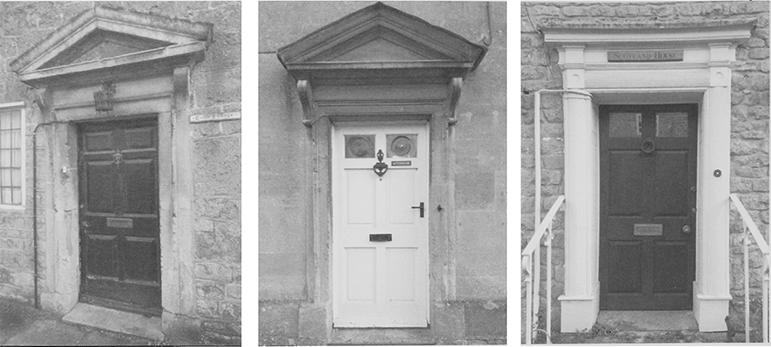

The rise of industrial and commercial prosperity probably accounts for the fine surviving late 18th and 19th-century town houses in Ansford and Castle Cary, and the former Florida House at Castle Cary built in 1877. Terraced housing for industrial workers was also built in the 19th century in Castle Cary and Keinton Mandeville, some of which survives. Large new houses were built at Kingweston in the 18th century and Alford in the 19th, the former with extensive areas of parkland requiring the removal of streets and roads. Kingweston village shows the influence of its landlords in distinctive farm buildings and estate cottages and in the extent of surviving wood and parkland. (fn. 63) Alford and West Lydford owe the layout of farms and fields to inclosure by their dominant landowners who, although largely absent, were represented by close relatives in the respective rectories. (fn. 64)

From the mid 18th century Kingweston was subject to the Dickinson family who were very active in changing the physical, farming, and social structure of the parish. Alford for a large part of its history had absent owners but from the early 19th century was managed by the Thring family and most residents worked on their farms or in domestic service with Alford House the major employer. (fn. 65) Parishes like Babcary and Wheathill, with absentee lords of manors, (fn. 66) Lovington, with its divided ownership, or Barton St David, with several freeholds and no large estate, have been dominated by farmers throughout their history. By the 19th century the presence of quarry workers altered the social structure of Barton, although not as greatly as at Keinton Mandeville. However, most fathers recorded in the early 19th-century Barton parish register were either labourers or stonecutters. (fn. 67) In the late 19th-century an enlightened farmer at Castle Cary invited leaders of the National Agricultural Labourers Union to address local labourers. (fn. 68)

6. Doorcases in South Cary, indicating aspirations to gentility in a street where many detached houses and inns were built from the later 18th century, (from left): Tudor Cottage, a late 18th-century house with a façade of random large squared blocks of Cary stone; Westholme, c. 1800, formerly the Golden Lion inn, built of Cary rubble with a Doulting ashlar façade; Scotland House, late 18th-century of squared and coursed Cary rubble with an early 19th-century doorcase.

Changes also took place in the government of the area as new local bodies replaced the rule of manorial courts and churchwardens. Centuries of hundredal administration came to an end in the 19th century and the area was divided between different authorities. In 1835 Alford, Ansford, Castle Cary, Lovington, and Wheathill became part of the Wincanton poor law union and in 1894 part of Wincanton rural district. Babcary, Barton St David, Keinton Mandeville, and Kingweston, became part of the Langport poor law union and in 1894 part of Langport rural district, but West Lydford formed part of the Shepton Mallet poor-law union, later rural district. In 1974 the parishes were reunited in Yeovil (later South Somerset) district except West Lydford, which as part of the new Lydford on Fosse parish lies in Mendip district. (fn. 69) Castle Cary had a parochial committee appointed in 1895 by Wincanton rural district council to deal with matters devolved to it by the district council. All the parishes had either a parish council or parish meeting although some were later amalgamated and since 1984 Castle Cary has had a town council. (fn. 70)

The population continued to be largely rural and agricultural although by the 19th century there were alternative employment opportunities for labouring families. The area's population rose from 3,070 in 1801 to 4,306 in 1831 but fell slightly to 4,235 in 1891. The fall would have been greater but for Keinton Mandeville's quarries and the rise of industrial Castle Cary. The latter accounted for 42 per cent of the area's population in 1801 and 1831 but 49.5 per cent in 1891. (fn. 71)

The growth of an industrial working class, notably in Castle Cary and Keinton Mandeville with its neighbour Barton St David, probably explains why religious nonconformity obtained a strong foothold in the area. Methodism and Congregationalism were established there from the late 18th century. At Keinton Mandeville in 1851 attendance at the chapels was more than twice that at the parish church and for another half century there was animosity between the rector and some nonconformist inhabitants. (fn. 72) At Castle Cary both the parish church and two nonconformist chapels flourished in the later 19th century but in 1851 attendance at church was greater than that at chapel. Most parishes, including Castle Cary, spent large sums rebuilding or enlarging their churches during the 19th century. (fn. 73) Nonconformist chapels, schools, Castle Cary market house, shops, and factories were also added to the built landscape.

Despite the employment opportunities of the early 19th century there was substantial poverty and migration. Emigration may account for the large fall in population in West Lydford in the 1820s (fn. 74) and in the early 19th century the Barton St David baptism register recorded people 'abroad'. Young men sought work in Bristol and London. (fn. 75) Others went gold digging in America and Australia. (fn. 76) Some parishes paid parishioners to emigrate. At West Lydford in 1848 the vestry recommended assisted emigration for 30 people willing to leave and between 1849 and 1856 at least five labouring families from Babcary emigrated to Australia. (fn. 77) In 1851 many paupers were on parish relief in Castle Cary and between 1849 and 1854 at least 11 adults, all literate and aged 19 to 25, with 5 children, went to Australia. (fn. 78) Between 1872 and 1896 it was said 300 members of the Castle Cary Good Templars Lodge had left the area. In the late 19th century many emigrated to Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, America, Canada, and India and some went to try their luck in the Californian goldfields. The Castle Cary Visitor was begun partly to keep emigrants in touch with the town. (fn. 79) Several sons of farmers and clergy were among emigrants from the area to Canada before the First World War. (fn. 80)

Castle Cary, however, also attracted immigrants especially from Scotland, which provided such leading inhabitants as John Boyd and William McKerrow from Ayrshire in the 1830s and 1840s and cheese factor James Mackie in 1853. (fn. 81) They arrived as travelling drapers, like the six young men from Scotland who shared a house in South Cary in 1871, and later William Macmillan. (fn. 82)

Local men sought employment in the army and navy in the 19th century, including a Castle Cary man who served as purser's steward on HMS Polyphemus and was at the battle of Trafalgar. (fn. 83) Some served for long periods and there were several military pensioners in the 19th century. (fn. 84) Volunteer corps were raised locally in the late 18th and early 19th century. In 1794 Castle Cary provided the first troop of Somerset yeomanry and in 1797 c. 50 volunteers formed an infantry company. A volunteer rifle corps was founded in 1860, which in 1908 became part of the Territorial Army. (fn. 85) By 1872 the headquarters of the 25th Somerset Volunteer Rifle Corps was based in Keinton Mandeville. (fn. 86)

The 20th century

That tradition of military service combined with strong local sentiment possibly accounts for the large numbers of local people who served during the First World War. Records, many of which survive, were made of service in every parish in the county. By December 1915 213 men from Castle Cary had joined up, over 12 per cent of the population, but more than 50 had been turned down as medically unfit. By 1918 330 had served and 28 had been killed. In Keinton Mandeville about a fifth of the population joined up and in most villages over 10 per cent of the population was in service, several were killed and many more wounded. The war decimated landed, clerical, and working families, and in the worst hit villages like West Lydford where more than a third were killed or wounded, shortage of labour after the war may have accelerated conversion of arable to grass. In addition to the 'young men's war' recorded on many war memorials, the 'home front' provided important support. Many women served as nurses, learned to use a rifle, and made kitbags and other items. Others took in Belgian refugees, as did several schools. Farms provided produce to be sent to the army and the navy and even children helped provide vegetables for the troops. (fn. 87)

The Second World War was experienced more directly as a war on civilians at home, partly due to the importance of local industry and the main railway line to the war effort. The presence of large numbers of military personnel in the area, including Americans, the construction of camps around Castle Cary, the large ammunition dump and camp at Dimmer, and a smaller dump at Babcary, the presence of searchlights in several parishes, and the widespread ownership of a wireless set, brought the war into even the smallest community. Castle Cary was for a large part of the war home to a brigade of guards, black American soldiers, and American and Red Cross nurses. There was also the airborne war, at least two British planes crashed locally, but the worst aspect of this war was the bombing. Unsuccessful attempts were made to destroy local industries but Castle Cary station at Ansford was bombed and machine gunned on 3 September 1942 killing three signalmen and injuring ten other people. The engine shed, parcels office, signal box, the Railway Hotel, and a train were destroyed and the milk factory and three railway cottages were damaged. (fn. 88)

The later 20th century has seen major changes in the area. Villages, although flourishing and most with increasing populations, gradually lost their shops, businesses, and services. All the villages but one have retained their church but many no longer have a service every Sunday. Castle Cary is linked with Ansford, a longstanding partnership, but Alford, Babcary and Lovington form part of a group of six parishes and Barton St David, Keinton Mandeville, Kingweston, and West Lydford are part of a grouping of five parishes which takes its name ironically from Wheathill, the one community which has lost its church, now a private house. Many nonconformist chapels in the area have closed, but Methodism thrives at Castle Cary and Keinton Mandeville. Schools have also been lost with declining populations and the move towards larger schools. Two large primary schools in Castle Cary and Keinton Mandeville and a small one in Lovington serve the needs of young children many of whom move on to Ansford School, although there are also secondary schools at Bruton and Street on the periphery of the area. Two rail lines carve their way across the area but there are no longer stations or facilities between Castle Cary and Taunton westbound or between Castle Cary and Yeovil southbound. Both Keinton Mandeville and Alford stations closed in 1962 when the Taunton service to Castle Cary was withdrawn. (fn. 89)

Evidence of the changing economy can be seen in the surviving Edwardian warehouses in Castle Cary, large, mechanised farmyards in several parishes, and the late 20th-century Torbay industrial estate. The importance of leisure and tourism have led to the establishment of a museum at Castle Cary, a golf course at Wheathill, large dining extensions to several public houses, and three long distance footpaths centred on Castle Cary. Housing has dominated new building from the bungalows and local authority housing of the mid 20th century to 21st-century timber houses at Castle Cary. By 2001 the area's population had risen to c. 5,500 (fn. 90) of which Castle Cary and Ansford accounted for nearly 60 per cent, despite the development of new housing and farmyard conversions in the rural area. (fn. 91) Although today the largest settlement and only town in the area, Castle Cary does not dominate. Not only does it lie in the extreme north-east but also other local towns, including Street, exert a pull on residents. However, Castle Cary still provides a variety of individual shops, services, and employment for a large part of the area and has the advantage of a park and ride railway station with regular services. With the decline of agricultural and industrial employment the inhabitants of the area increasingly work elsewhere and can commute to Taunton, Yeovil, Reading, and London. Apart from Ansford, now in effect a suburb of Castle Cary, the largest village is Keinton Mandeville, reflecting its recent industrial past. It continues to provide local shops and services on the road almost half way between Somerton and Castle Cary.

CATSASH HUNDRED

LIKE most Somerset hundreds Catsash was a fairly topographically cohesive area bounded by the river Brue to the north, except at West Lydford, which straddles the river and by hills to the west, south and east. Although Somerset hundreds were in existence by the 1080s, and probably at least a century earlier, many were later reorganised and renamed. Some, like Bruton and Somerton, were based on royal estates. As Catsash was not recorded until 1185, it has been suggested it was one of the unidentified 11th-century hundreds of Ascleia and Blachethorna. However, it is more likely to have been part of Bruton hundred. (fn. 92) In 1084, in an inquest detailing hundreds, manors later in Catsash appear to have been in Bruton hundred which comprised 232 hides, unusually high. (fn. 93) In 1280 a jury from Catsash, Stone, and Norton hundreds inquired into the ownership of Bruton hundred. (fn. 94)

The name may be medieval referring to the meeting places of the courts. (fn. 95) In the 18th century, and possibly for centuries before, the sheriff's tourn was held, with those for Bruton and Norton Ferris hundreds, at Cats Aish, an ash tree in a field by three cross-ways near Bruton. (fn. 96) The tree was later said to have been opposite the north-west drive to Hadspen, (fn. 97) near the boundary between Bruton and Catsash hundreds. Hundred leets, however, were held 3 ½ miles to the south-west at an ash tree in North Cadbury parish, on the Sparkford–Castle Cary road, named Catsash by 1822. (fn. 98) The jury was said to stand or sit round the tree to choose the constables (fn. 99) but it is not known how long this meeting place had been in use. The site possibly gave its name to fields either side of the road called Down Ash. (fn. 100) A crossroads further east, known from the later 19th century as Three Ashes, was also claimed as the meeting place. (fn. 101)

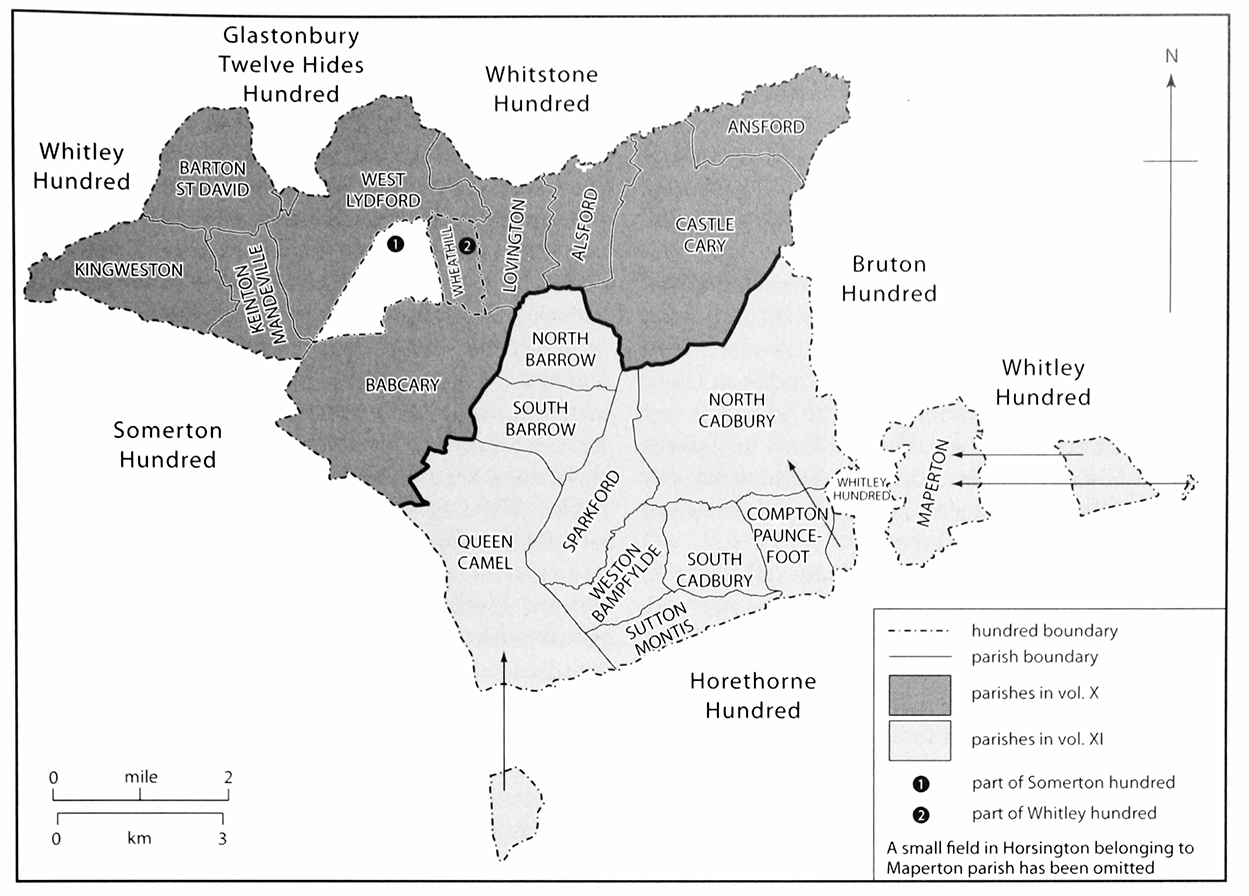

7. Catsash Hundred

The hundred of Catsash is fairly compact, although it surrounds East Lydford in Somerton hundred and Wheathill in Whitley hundred. Maperton is slightly detached from the rest of the hundred. A few parishes have detached areas, notably Hatherleigh in Maperton and Nether Adber in Queen Camel.

Catsash lacks complete topographical cohesion because of the earlier removal by Glastonbury abbey of its pre-Conquest estates of Blackford, Holton, East Lydford, and Wheathill to its own jurisdiction. The abbey lost East Lydford after the Conquest and it was attached to Somerton hundred. (fn. 102) In 1841 Catsash covered over 25,000 acres and comprised 19 parishes. (fn. 103)

THE MEDIEVAL HUNDRED

In 1303 Alford, Ansford, Babcary, North Barrow, South Barrow, Barton St David, North Cadbury, South Cadbury, Castle Cary, Compton Pauncefoot, Keinton Mandeville, Lovington, West Lydford, Maperton, and Sparkford were in the hundred. Although not recorded, Kingweston, Sutton Montis, and Weston Bampfylde were probably already part of Catsash and were so considered in 1316 when Steart was also included although Queen Camel was listed under Somerton hundred. (fn. 104) In the 13th century Steart in Babcary was a free tithing, owing no suit to the hundred, and Queen Camel was a hundred of itself. (fn. 105) In 1327 and 1336 both Steart and Queen Camel were taxed as free manors. It is a feature of this hundred that several tithings included more than one parish not always adjacent or in the same ownership. Barrow tithing comprised North and South Barrow parishes and Cadbury comprised North and South Cadbury parishes. Alford formed a tithing with Lovington, Ansford tithing was recorded from 1225 (fn. 106) but was often considered to be part of Castle Cary tithing or Caryland (fn. 107) apparently a unit for royal administration, and Barton St David tithing included Keinton Mandeville by 1327 and from the 16th century Kingweston. Compton Pauncefoot was part of Sparkford and Sutton Montis was part of Weston Bampfylde. (fn. 108)

During the 13th century the hundred belonged to the Crown. (fn. 109) However, Crown control was weak and some landowners withdrew their holdings to more convenient courts. The hundred jury in 1242 complained that part of Barton tithing paid suit under Croscombe tithing to Whitstone hundred and that Barrow tithing had withdrawn. (fn. 110) Inquiries in 1274, 1276, and 1290 found that suit to the hundred had been withdrawn by the owners of a third of Barton St David for over 40 years, West Lydford, Babcary and Foddington, and lands in Castle Cary and North Barrow for up to 20 years. (fn. 111) It was claimed that William Mandeville had freed his men in Keinton and Barton from suit to the hundred in the early 13th century but his successor in 1315 complained he was distrained to find a man to serve. (fn. 112)

In 1225 a hundred bailiff or sergeant and a jury of twelve examined a case of murder. (fn. 113) From the early 14th century a succession of royal appointees held the office of keeper, usually with Stone hundred in the south of the county. (fn. 114) At least one held office for life (fn. 115) but in 1370 Catsash hundred with the sheriff's tourn was farmed for 10 years to Sir William Botreaux for £10 11s. 6d. a year and in 1381 to Sir John Lovel, renewed for 12 years in 1391, although the hundred was valued at only £10 a year. (fn. 116) The actual profits were presumably unrecorded. In 1392, however, the hundreds of Catsash and Stone, were granted to John Holand, earl of Huntingdon (d. 1400), his wife Elizabeth, and their male issue. (fn. 117) The earl, and after his attainder the king, farmed out the hundred. (fn. 118) In 1418 the earl's son, also John Holand (restored 1417, cr. duke of Exeter 1444), obtained the hundreds with reversion of Elizabeth's dower. (fn. 119) They descended with West Lydford manor (fn. 120) but in 1484 Catsash hundred was given by Richard III to Sir Thomas de Burgh (fn. 121) and in 1487 by Henry VII to his mother Margaret, countess of Richmond (d. 1509) whose heir was her grandson Henry VIII. (fn. 122)

POST-MEDIEVAL HUNDRED

The Crown retained the hundred for most of the 16th century. Sir Edward Seymour was steward in 1546 although John Hannam served as his deputy. Most of the recorded income was spent on fees and expenses. (fn. 123) In 1552 the revenue from the combined hundreds of Catsash and Stone was £6 7s. 4d., half from court profits and most of the rest from rents and free suitors. (fn. 124) The steward was paid £3 6s. 8d. a year (fn. 125) and in the bailiff and collector £2 13s. 4d. (fn. 126) The Crown leased the hundred from the 1570s for more than the stated income out of which the lessee had to pay the fees of the steward and bailiff, which indicates that there were sources of income that were not recorded in the official accounts. (fn. 127)

Tobias Andrews (d. 1620) acquired Catsash, which he settled on his grandsons, sons of William Overton. (fn. 128) Edward Curle and William Gander, sequestrators between 1645 and 1647, controlled large parts of the hundred, which had been held by royalist landowners. (fn. 129) In 1650 the Overton family conveyed the hundred to George Starr (fn. 130) who replaced the hundred bailiff Henry Gander, appointed by the county committee, with John Mogg. In 1651 the hundred constables were ordered to arrest Starr and Mogg for contempt. (fn. 131) Little is known of the later ownership of the hundred but the Blandford family held it between the 1790s and 1830s (fn. 132) and it presumably descended with their estates in Weston Bampfylde. (fn. 133)

HUNDRED COURT AND JURISDICTION

Three-week courts and sheriffs' tourns were recorded in the late 13th century. (fn. 134) In 1400 six hundred courts and one hundred leet were held in a half year. (fn. 135) Courts leet with view of frankpledge were held twice a year in the 16th century usually in October and April, followed a few weeks later by the sheriff's tourn and 14 hundred courts held at roughly three-weekly intervals throughout the year to deal with pleas. The leets and tourns were attended by all the tithingmen except for Queen Camel. They presented millers, butchers, and bakers overcharging, alesellers and brewers in breach of the assize, and highways out of repair. Money was received from tithings and free suitors and expenses were shared with Stone hundred. In the later 16th century lists of freeholders owing suit were also presented. (fn. 136) In 1604 two tithings outside the hundred were presented for not paving a road. (fn. 137) In 1745 the court was advertised for the recovery of small debts and met at North Cadbury. (fn. 138) The sheriff's tourn was still held in the 18th century. (fn. 139) By 1806 most business was carried out at Wincanton and from 1810 to 1848 or later a court was held at Sparkford. A hundred court leet held in 1848 appointed four constables and tithingmen, except those for Castle Cary and Queen Camel. (fn. 140)

Court rolls survive for 1511–12 (fn. 141) and 1564–5, (fn. 142) estreats for 1598–1607, (fn. 143) and summary accounts for several years from 1525 to 1552, when the bailiff accounted for two leets and eleven hundred courts. (fn. 144) By 1600 the understeward, John Dyer, kept the accounts and continued to do so after becoming steward in 1603. (fn. 145)

In the early 17th century, for purposes such as relief of the poor and ship money, Catsash hundred was grouped with Bruton, Horethorne, and Norton Ferris hundreds. (fn. 146) By 1636 the hundred was divided into east and west and there were rating disputes between the two and between tithings. (fn. 147) Sir Thomas Wroth found 'so much delay and unwillingness in this place to pay the ship money' partly caused by the claim by the western division that the eastern division was worth more. (fn. 148)

During the 17th and early 18th centuries the hundred constable, occasionally two, enforced the law. He compiled lists of alesellers for Quarter Sessions, (fn. 149) toured fairs, even outside his area, in search of thieves, (fn. 150) and was involved in the arrest and detention of suspects. (fn. 151) A constable was discharged and replaced in 1621 to serve both Catsash and Stone hundreds. (fn. 152) It is not clear if courts were held under sequestration but Edward Curle suppressed alehouses, 'the nurseries of Hell', and maltsters. He and the county committee were supported by the hundred constable. (fn. 153) In 1732 a poor blacksmith was considered unsuitable for the office, then known as High Constable, as he was not a freeholder, so presumably not independent, and could not write nor read a written hand. (fn. 154) Shortly after that date constables were chosen for each division of the hundred (fn. 155) and in 1848 for the 'in' and 'out' hundred, Lovington, and North Cadbury. (fn. 156) By the late 19th century only one constable was appointed, solely to collect the county rate. (fn. 157)

THE END OF THE HUNDREDAlthough the hundred may have exercised less jurisdiction by the 18th century, it was used as a unit for collecting taxes, elections, and raising the militia. (fn. 158) Castle Cary had four tithings but otherwise the composition of the hundred was unchanged and tithingmen or petty constables were sworn at the Catsash leet. Queen Camel kept its freedom and appointed its own constable who dealt directly with the county treasurer but it was regarded as being in the hundred. (fn. 159) Part of Barton St David parish was in Whitstone hundred, Clapton in Maperton and possibly Woolston in North Cadbury (fn. 160) were in Bruton hundred, and Nether Adber in Queen Camel was in Houndsborough, Barwick, and Coker hundred. (fn. 161) By 1837 memory of the meeting place at Catsash had been lost. (fn. 162) By the late 19th century the leets had ceased to be held and no business was conducted at the Catsash hundred courts. (fn. 163) By 1900 it was said the hundred itself was forgotten. (fn. 164)

The historic grouping of parishes that was Catsash hundred was broken up when the new poor-law unions were created. Having no suitable centre for a workhouse most of Catsash was absorbed into the Wincanton union but some parishes further away were placed in Shepton Mallet and Langport unions. The creation of rural districts in the 1890s rendered these new divisions permanent. Although most of the old hundred was reunited in 1974 in the modern South Somerset district, which merged Langport and Wincanton rural districts, Lydford lies in Mendip district. (fn. 165)