A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 16. Originally published by Boydell & Brewer for the Institute of Historical Research, Woodbridge, Suffolk, 2011.

This free content was digitised by double rekeying. All rights reserved.

'Henley and the Chilterns', in A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 16, ed. Simon Townley (Woodbridge, Suffolk, 2011), British History Online https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/vch/oxon/vol16/pp1-18 [accessed 10 May 2025].

'Henley and the Chilterns', in A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 16. Edited by Simon Townley (Woodbridge, Suffolk, 2011), British History Online, accessed May 10, 2025, https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/vch/oxon/vol16/pp1-18.

"Henley and the Chilterns". A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 16. Ed. Simon Townley (Woodbridge, Suffolk, 2011), British History Online. Web. 10 May 2025. https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/vch/oxon/vol16/pp1-18.

In this section

HENLEY AND THE CHILTERNS

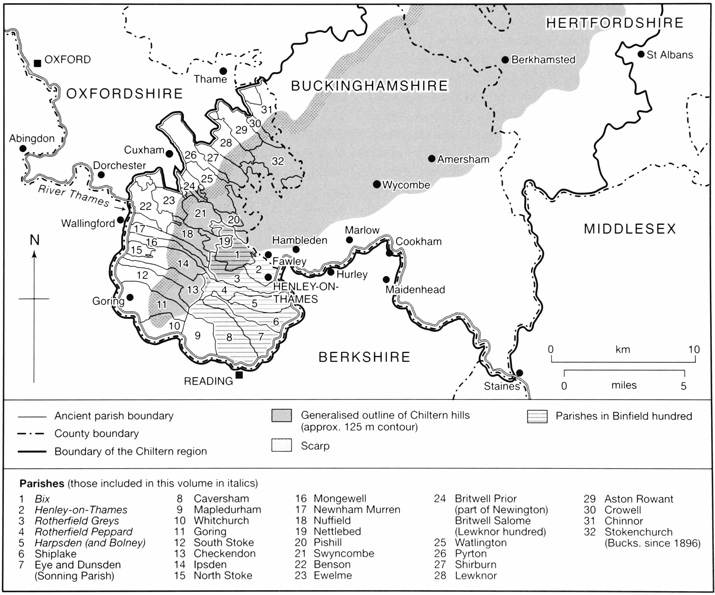

Henley-on-Thames and the four surrounding rural parishes covered in this volume are in the far south-east of Oxfordshire, bordering Berkshire and Buckinghamshire. They formerly comprised the northern half of Binfield hundred. (fn. 1) Bix, Harpsden, Rotherfield Greys and Rotherfield Peppard all lie on the dip slope of the Chiltern hills, a chalk outcrop which stretches 50 miles (80 km) across parts of four counties, from Goring (Oxon.) in the south-west to Hitchin (Herts.) in the north-east. With their scattered farms and hamlets set amongst steep slopes, woodland, and small fields, these places form part of a distinctive landscape region on the edge of the London basin, separated from the rest of the county by the scarp face of the northern side of the Chilterns. Henley itself, the only town in the hundred, lies on flatter land to the east, on a sheltered bend in the river Thames, surrounded by hills on three sides and low-lying meadows to the south. The river, which for part of its course marks the county boundary, forms a large loop around a number of parishes south and west of Henley, from Goring (in Langtree hundred) in the west to Shiplake in the east. (fn. 2)

1. Henley, Binfield hundred, and the Chiltern region, showing boundaries and relief.

The south-west Chilterns have long been a thinly settled area, forming an upland buffer zone between surrounding lowland regions. But despite its peripheral location and rather difficult terrain, this part of Oxfordshire has never been self contained. It was also a connecting point: a small but increasingly important hub of communications and economic life which was firmly tied into its surroundings. From prehistory the Chiltern hills formed a shared resource and communication route, used by those living beyond the scarp face as well as by inhabitants of the dip slope and the Thames valley. By Roman times the southern part of the hills, though remote from major centres, included several villa sites, and was crossed by roads and tracks which formed part of a network connecting the west of England and the Midlands with the south-east and London. Most remained important routes for communication and trade for many centuries. In the later Anglo-Saxon period the Henley area belonged to the large royal estate of Bensington, linking it with Benson and the clay vale across the Chiltern hills. (fn. 3) The partial break-up of the Bensington estate before the Conquest created smaller estates which formed the basis of the later parish structure, stretching up into the hills from the lowlands beyond the northern scarp, and from the bottom of the dip slope.

From an early period, however, the most powerful link with the outside world was the Thames, which acted as a corridor for the movement of people, goods, and ideas. In the high Middle Ages the area's longstanding connection with the lowlands to the north was subordinated to increasingly important economic ties with London, some 65 miles east along the river, which then and long after provided the easiest transport route for heavy materials. In the late 12th century an urban centre and market was created at Henley next to a pre-existing river crossing, almost certainly on royal initiative; by 1300 the town was both the pre-eminent collection and trans-shipment point for grain sent from the middle and upper Thames valley to the growing metropolis, and one of a number of loading places for fuel wood, which was also carried downriver. Its success was underpinned by increasing demand from London, by deteriorating navigation further upstream, and by its excellent communications by river and road, which were enhanced by the construction of a stone bridge probably when the town was laid out. (fn. 4)

The relationship between Henley, London, and the surrounding rural areas continued after the Middle Ages, as the capital's population and economy expanded. Henley remained an important inland port, shipping grain, malt and wood to the city, and by the 18th century it had also become a main coaching stop on the road to London (c. 38 miles away overland). Difficult farming conditions in the parishes immediately around the town were partially ameliorated by agricultural improvement and a continuing growth in farm size, and by the presence of an important local market. The mid 19th century brought a new transport link in the form of the railway, which had a profound effect. This faster connection with London initiated the decline of the river as an artery of trade, but it also made the town and surrounding countryside more accessible to visitors, and helped to turn Henley, with its popular annual regatta (established in 1839), into a fashionable riverside resort in the late 19th century. The area's social character changed as a result, with a new breed of affluent residents moving in. At first the effects were relatively limited, promoting pockets of new housing development. But in the second half of the 20th century social changes were intensified by the rapid decline of local farming and a striking rise in property prices, as the area became an increasingly popular hideaway for the very wealthy. (fn. 5)

Landscape

The area north-west of Henley is one of the most deeply dissected and irregular parts of the Chiltern dip slope. The land surface, which forms a kind of tilting shelf, slants in a generally south-easterly direction – from higher ground in the north and west (150–195 m.) to flatter, more open land further south and east, where the dip slope meets the gravel terraces of the Thames valley (35 m.). The terrain is deeply etched by steep-sided narrow valleys or 'bottoms', set amongst sharp ridges and small uneven plateaux. The valleys here are dry, with permanent streams found only below the spring line at the very foot of the dip slope. In places the chalk bedrock lies exposed, particularly on the steeper ridges, but much of the area is covered by patches of clay-with-flints, sands and gravels. (fn. 6)

Thanks to these superficial deposits, the countryside is more like that of a hilly 'wood-pasture' district than an open chalk downland, with fields and commons interspersed among extensive areas of woodland. The Chilterns region, including the southern part around Henley, is one of the most heavily wooded areas in England. (fn. 7) Woodland (now mainly high beech interspersed with plantations, but formerly more varied) is most extensive on the clay plateaux and steeper slopes, particularly in the west of Bix and the Rotherfields. But even in the valleys, which are more open, the fields are divided by numerous hedges, some of them forming small wedges of woodland called 'shaws', left over from the clearance of more extensive woods. (fn. 8) The wooded and uneven terrain creates a secluded and intimate landscape with short horizons from all but the highest viewpoints.

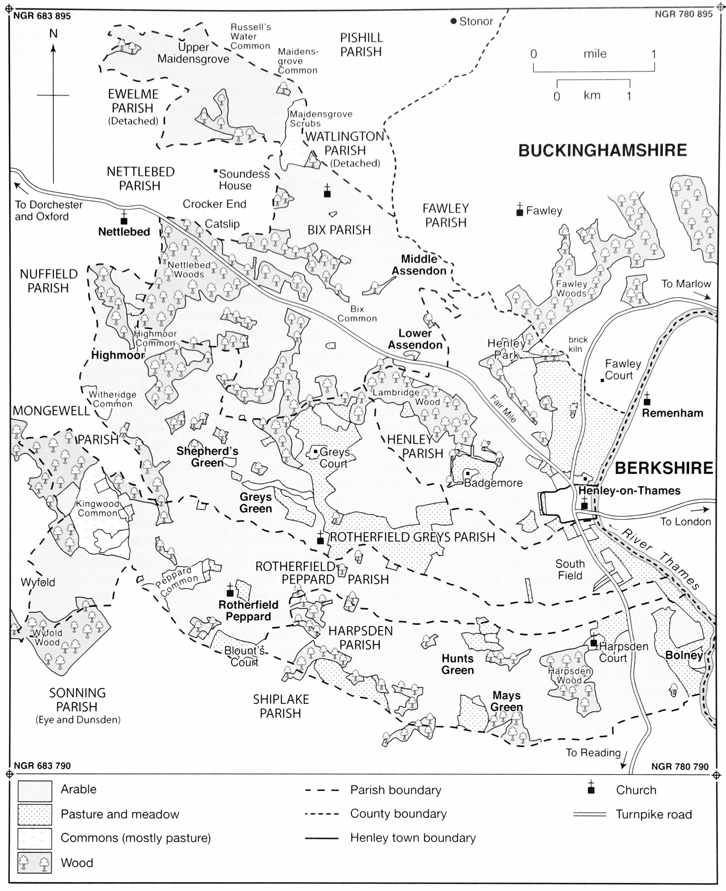

2. Land use in the Henley area c. 1840, a period of intensive arable farming.

The mixture of woodland and open country almost certainly reflects a very old landscape pattern. (fn. 9) The name 'Rotherfield', meaning 'open land where cattle graze', suggests that parts of Rotherfield Peppard and Rotherfield Greys already had an open character in the Anglo-Saxon period; (fn. 10) presumably that included the heaths and commons which remain in the centre and west, as well as the flatter land towards the Thames in the east. The name Bix ('box tree' or 'box grove') similarly implies a discrete wooded area in a partly open landscape. (fn. 11) Yet despite these important continuities, the appearance of the countryside has changed considerably over the centuries.

Part of the story is the reduction of woodland during phases of increased farming activity. Large areas have been cleared for agriculture, presumably from the earliest periods of settlement and farming, and perhaps as early as the Neolithic. Certainly the eastern part of the area near the river seems to have been largely open grassland by the Iron Age. (fn. 12) The conversion of woodland to fields is difficult to date, but clearance almost certainly increased during periods of agricultural expansion such as the high Middle Ages and the late 17th to early 19th centuries. (fn. 13) Other areas seem to have gradually changed from woodland to open common thanks to intensified grazing and wood-cutting, as at Maidensgrove (formerly Minigrove or 'common grove'), which extended into the north-east of Bix. (fn. 14) Thus while woodland probably covered over a third of the area in 1600, (fn. 15) it accounted for only about 17 per cent by the 1840s. (fn. 16) Since then some hedgerows have also been removed, partly through amalgamation of holdings, and more recently to facilitate the use of large farm machinery.

At other times, areas of woodland have increased in size. The presence of Roman settlement in Harpsden Wood and High Wood suggests that the now well-wooded spur of high ground above the Harpsden valley was once much more open, perhaps reverting to scrub and then woodland in the post-Roman period. (fn. 17) In the late Middle Ages, too, contraction of farming seems to have led to a gradual expansion of tree cover. (fn. 18) More recently, from the late 19th century, woodland has spread as agriculture has gradually decreased in intensity. In part this reflects the plantation of coniferous woods as game coverts (some of them on former arable land), and creation of parkland and orchards. Elsewhere, the spread of scrub and trees has resulted from reduced grazing, as on Kingwood Common (Rotherfield Peppard) in the later 20th century. (fn. 19)

The landscape is heavily pock-marked by numerous small pits, next to farmhouses and scattered across fields and woods. These were apparently dug to extract a variety of substances, including clay, sand, gravel, marl, and chalk, which was sometimes burnt to produce lime. These materials were used for brick-making, local road construction and repair, and above all for farming: chalk, marl and lime were all spread over fields to improve soil texture and reduce acidity. Individual pits are nearly impossible to date, but many were probably created during the period of intensive agriculture in the late 18th to mid 19th century. Some larger-scale gravel extraction was carried out in the 20th century, as at Highlands Farm (Rotherfield Peppard), but there has been no major quarrying industry. (fn. 20)

Communications

Roads

Henley stands at the intersection of several early routes, whose importance long pre-dated the building of a bridge and the development of the medieval town. These routes passed mainly in a north-west to south-east direction, but just north of the area covered here, at the scarp face of the hills, they intersected with the ancient ridgeway and Icknield Way, which probably provided long-distance passage north-east towards East Anglia. (fn. 21)

The most important of the early routes was the road from Dorchester and Wallingford, almost certainly of Roman or earlier origin, which enters modern Henley along the Fair Mile. Westwards, it connected with the north-south road from Watling Street and Alchester, which ran through Dorchester and on to Silchester. East of the river it probably joined the main Roman road to St Albans (Verulamium), although where it crossed the Thames has not been definitively established. (fn. 22) Presumably the road continued in use during the Anglo-Saxon period, linking the royal centre at Benson and the Alfredian burh at Wallingford with the important royal minster at Cookham in Berkshire. Possibly it helped to determine the shape and extent of the Bensington estate, which extended along much of its length, straddling both the Chilterns and the later hundred boundaries. (fn. 23)

The building of a bridge at Henley in or before the late 12th century both reflected and enhanced the Dorchester road's importance, particularly from the early or mid 13th century as Henley emerged as a major trans-shipment point. (fn. 24) By then it formed part of the main route from London to Gloucester and the Welsh Marches, which passed through Wallingford and Oxford until the building of Abingdon bridge in the early 15th century. Thereafter the favoured route for long-distance westwards traffic from Henley was through Abingdon, Faringdon, and Lechlade, or through Witney and Burford via Newbridge. The Dorchester road nonetheless remained the chief route from Henley to Oxford. (fn. 25)

Of the other early routes, one of the most significant was through the Assendon valley to Watlington. In the Anglo-Saxon period this connected with a route along Knightsbridge Lane through Pyrton and eventually to Oxford. (fn. 26) Probably it retained considerable importance in the Middle Ages, when it may have connected the Thames valley with Worcester. (fn. 27) The road through Bix Bottom seems to have provided an alternative northerly route in the earlier Middle Ages, although it declined thereafter. (fn. 28)

By the 13th or 14th century and probably much earlier, a network of roads linked Henley with the surrounding towns of Watlington, Wycombe, Marlow, Maidenhead, and Reading. (fn. 29) The Reading–Marlow road, intersecting the Dorchester–London road at Henley's northern end, must have been a major route by the time the planned town was laid out, and almost certainly existed in the late Anglo-Saxon period. (fn. 30) Traffic from Southampton, recorded in the 15th century, (fn. 31) perhaps also entered Henley through Reading. A road from Hambleden, presumably part of the Marlow road, was mentioned in 1416, and a road from Goring (passing to Henley probably through Rotherfield Greys) in 1353. (fn. 32)

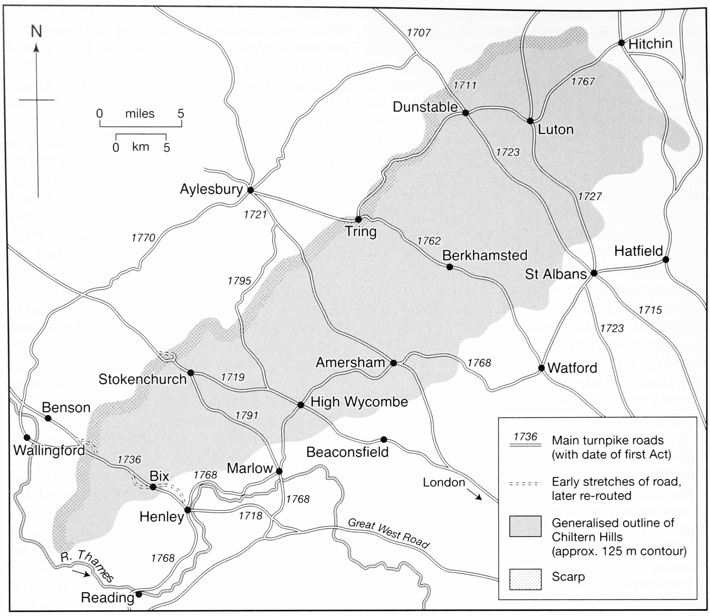

From the early 18th century the chief roads through Henley were improved by local turnpike trusts and on private initiative. Work was inspired by a general increase in traffic, and particularly by the growth of coaching. (fn. 33) The road from Maidenhead to Henley bridge was turnpiked in 1718, (fn. 34) and the Henley– Dorchester road (continuing to Oxford via Abingdon) in 1736. (fn. 35) The south–north route from Reading to Marlow, continuing to St Albans and Hatfield (Herts), was turnpiked in 1768. (fn. 36) In the 1780s, by which time coaching had 'greatly increased' traffic over Henley bridge, the Dorchester road formed part of the Great Western Road from London, leading to south Wales and the north-west of England. The bridge itself was rebuilt in 1781–6. (fn. 37)

Turnpiking brought better road surfaces and reduced journey times, though road travel retained its hazards, including highwaymen. (fn. 38) The most widespread problem was poor surfaces on unturnpiked roads, which were still maintained at a parish level. A dense network of muddy lanes and tracks continued, criss-crossing the rural parishes to link the area's dispersed settlements and scattered agricultural resources. (fn. 39)

Coaching declined rapidly with the provision of local railway links in 1839–40, though some goods continued to be transported between Henley and London by road, especially before the belated opening of a railway station at Henley itself. (fn. 40) Additional local road traffic was created by carriers operating between the new railway stations and nearby settlements. The scale of road use was transformed in the second half of the 20th century, partly through the general spread of private motor car ownership, but also through improved long-distance communications following the construction of the M4 and M40 motorways in the 1960s and 1970s. (fn. 41) Congestion around Henley and its narrow 18th-century bridge remained a problem in the early 21st century. (fn. 42)

River and Rail

The Thames provided a major trade and transport route from early times, especially in periods of economic growth. The scale and frequency of activity in late prehistory and the Roman period remains uncertain, but goods seem to have been moved along it (especially downstream) from at least the later Bronze Age, and by the late Iron Age Thames trade may have been highly important. Usage seems to have intensified in the 10th and 11th centuries, thanks partly to canalization. (fn. 43)

3. Turnpike roads in the Chiltern region.

From then until the 19th century the river remained a major artery for commerce, though not always to the same degree along its whole length. An increase in the number of weirs and mill-dams between the 10th and 14th centuries seems to have made navigation upstream from Henley increasingly difficult, and from the 14th century falling demand from Oxford and from upriver towns such as Wallingford (both of which experienced economic difficulties in the later Middle Ages) probably further reduced merchants' profit margins on the upper stretches. Occasional navigation to Oxford continued until at least the mid 15th century, but by the mid 13th Henley was being used for trans-shipment of goods, and by c. 1300 it was a significant 'break point', beyond which regular, large-scale commercial navigation seems to have been regarded as uneconomical. Consequent neglect of the higher Thames probably cemented Henley's role as the preeminent trans-shipment point for goods being transported to and from London. That role was undermined by the reopening of regular navigation to Oxford and beyond in the early 17th century, following major engineering works by the Oxford-Burcot commission. Nonetheless, increased demand from London ensured that Henley continued as a major inland port, supporting a significant body of bargemen and other river workers, and trading in the increased variety of goods which were carried on the Thames by the later 18th century. (fn. 44)

The construction in 1839–41 of the Great Western Railway from London to Bristol crippled Henley's coaching trade almost immediately, and initiated a protracted decline in commercial use of the river. (fn. 45) Henley's initial failure to secure a branch line caused severe economic problems for the town, which became a transport backwater until a station was opened in 1857, with another small stop at Shiplake 1½ miles to the south. Although services were limited, especially before the 1890s, the railway proved highly important for both passenger and goods transport, providing a catalyst for Henley's regeneration as a riverside resort and for the gentrification of the area more generally. Regular through-services to London were abandoned in the 1970s, but direct peak-time services to Paddington were reinstated in 1993 and remained well-used in 2009. A Reading service introduced in 1988 was later dropped. (fn. 46)

Settlement

Early Settlement

The first human presence in the area dates from up to half a million years ago. The evidence for such early activity comes from a gravel pit at Highlands Farm (Rotherfield Peppard), where excavations have revealed a major flint-tool production centre. The site was reused over a long period, and chance finds from elsewhere suggest the intermittent presence of small numbers of hunter-gatherers during the vast span of time covered by the Palaeolithic and Mesolithic, roughly 500,000–4,000 BC. (fn. 47)

There have been scattered Neolithic finds, (fn. 48) but the first clear indication of settled farming communities is a probably early Bronze-Age barrow near Crosslanes (Rotherfield Peppard), 1½ km west of Henley. This may have been part of a significant ceremonial centre incorporating other smaller barrows, and seems to have had several phases of use. (fn. 49) Iron-Age settlement has been identified on the gravels of the Thames floodplain at the foot of the dip slope, (fn. 50) while a section of earthwork called Grim's Ditch (probably a tribal boundary), together with pottery finds in Bix Bottom, suggest late Iron-Age activity and probably small-scale settlement on the dip slope itself. (fn. 51) Nonetheless, the main focus of late Iron-Age population was probably in the surrounding lowlands rather than in the hills, with Dorchester to the north-west apparently acting as a 'gateway' settlement or meeting point between different social groups. (fn. 52)

Remains of Romano-British villas have been found on high ground in Bix and Harpsden. (fn. 53) The villa on the edge of Harpsden Wood is one of the larger ones known in the county, but like the smaller complex at Bix it seems to have been of modest status: both were apparently unusual among Chiltern villas in not having tessellated paving, although the Harpsden complex was only partly excavated. (fn. 54) Possibly this reflects the area's position on the southern edge of a region whose main administrative and economic focus was at Verulamium (St Albans), 40 miles north-east, to which the small town at Dorchester acted as a subsidiary centre. (fn. 55) Dating evidence is fragmentary, but suggests a peak of activity in the 3rd and 4th centuries, and a fairly rapid decline thereafter. The full extent of rural settlement during the Roman period remains unknown, but some lower status farmsteads were almost certainly present in addition to the villas, and a pottery kiln was located in the west of Rotherfield Greys. (fn. 56) A more substantial settlement may have existed at Henley, where the Silchester-Verulamium road probably forded the river, but so far the findings have been inconclusive. (fn. 57)

Medieval and Later Settlement

Evidence for the early Anglo-Saxon period is limited. One view is that the earliest Anglo-Saxon settlement was concentrated on the gravel terraces of river valleys north and south of the hills, and that the higher ground was only gradually colonized from the 7th century onwards, starting in the flatter, better watered and more fertile north-east. However, this may have been because the Chilterns formed part of a surviving British enclave, rather than because it was an unappealing and abandoned wasteland. (fn. 58) The apparent spread of woodland around Grim's Ditch and the villa sites implies a reduction of farming activity after the 4th century, but how long this lasted is uncertain. Placename evidence and later territorial links suggest that in the 7th and 8th centuries the southern Chilterns was predominantly used for seasonal grazing by pastoralists coming over the scarp from the lowlands in the north. (fn. 59) By the 10th century, however, charter bounds for areas bordering Harpsden and Bix show that this part of the hills was closely organized and, almost certainly, settled. (fn. 60) It seems probable that in the 10th century (and perhaps as early as the 8th) settlement comprised dispersed farmsteads and small hamlets, perhaps mainly located below the spring line at the foot of the dip slope, in the valley bottoms, and on those plateaux with more favourable soils. (fn. 61) Domesday Book (1086) gives a picture of small and scattered farming communities, including around Bix, some way up in the hills. (fn. 62)

Medieval settlement remained dispersed, its broad outline probably similar to that shown on 18th- and 19th-century maps. By the high and late Middle Ages it took the form of scattered hamlets and isolated farms, characteristic of much hilly and wooded countryside. (fn. 63) The growth of population was hindered by a lack of water supply on the dip slope, where there were no streams or regular springs: until piped water was laid on in the early 20th century, locals had to rely on clay-lined rainwater ponds, tanks and (later) deep wells. (fn. 64) The early formation of strip-like land units did, however, help to provide the inhabitants of individual estates with a mixture of resources, from Thames-side meadow and valley land to woods and hill pasture. (fn. 65)

Loose settlement clusters, partly reflected in surviving medieval churches, manor houses, and a few (late) farmsteads, focused on two main features: roads and commons. Stretches of road, and particularly road junctions, probably attracted widely spaced farmsteads from an early date, for example in the Harpsden, Bix and Assendon valleys. (fn. 66) Commons may have become centres for settlement slightly later, when their boundaries stabilized in the 12th or 13th century because of the need to protect remaining woodland and grazing from further clearance and conversion to arable. (fn. 67) Common-side settlements (often later suffixed 'Green') were particularly numerous in the Rotherfields, perhaps reflecting greater population growth, a larger number of smallholders, and a higher level of assarting in these two parishes. Places which combined road junctions with commons seem to have been particularly attractive: in Rotherfield Peppard many medieval dwellings were gathered probably around Peppard Common, where the north-south road from Nettlebed to Reading crossed the east-west route from Henley to Goring. (fn. 68)

Settlement was far from static during the Middle Ages, however, and later maps cannot be treated as blueprints for medieval (and especially early medieval) patterns. The location of houses and settlement clusters probably shifted over time, as suggested by a substantial scatter of late 12th- and early 13th- century pottery in a now unoccupied field east of the present Bix 'village'. (fn. 69) In particular, there seems to have been fairly large-scale settlement shrinkage in certain areas during the later Middle Ages, thanks to the long period of reduced population which followed the famine and plagues of the 14th century.

Striking evidence of settlement decay is provided by two cases of parish amalgamation in the 15th century, the first involving Harpsden and Bolney and the second Bix Brand and Bix Gibwyn. In both cases population decline after the Black Death made two churches unnecessary, and the smaller, poorer ones (Bix Gibwyn and Bolney) were abandoned. These places were probably especially susceptible because of the small size of the parishes before amalgamation and, in Bolney's case at least, because of a lack of population growth between 1086 and 1300. The effect of decay was to thin out certain areas, rather than to fundamentally alter the dispersed pattern of settlement. The areas worst affected were seemingly the south-east of Harpsden, and the Bix Bottom valley in the north of Bix. These were the core of the Bolney and Bix Gibwyn manors and the vicinity of the abandoned churches, of which nothing now remains. (fn. 70)

When limited population growth bolstered settlement in these parishes from the 16th and 17th centuries, the overall picture was subtly altered. In Bix, a formerly complex and highly dispersed pattern of medieval settlement (which included an estate centre at Bromsden in the far south-west of the parish) apparently gave way to a greater concentration in the south-east, around the Assendon valley and what is now called Bix 'village'. This was probably associated with an increase in traffic on the main road which passed through the south of the parish. (fn. 71) In Harpsden, the decline of Bolney shifted the focus to the Harpsden valley until the early 20th century, when new houses were built around Bolney Court and in Harpsden Wood.

4. Landscape and settlement in the Henley area c. 1797, from Davis's New Map of Oxfordshire. The mixture of woodland, wood pasture and small hedged closes is typical of the Oxfordshire Chilterns.

In all the rural parishes modern settlement remains mostly dispersed, despite some 20th-century infilling. This is largely thanks to modest population growth between the 16th and early 20th centuries, and planning restrictions introduced from the mid 1960s. (fn. 72) Settlement in Harpsden and Bix is particularly thin, not least because of problems of access and a lack of services; what development there has been is concentrated in the Assendon valley (which connects to the Fair Mile), and in the far south-east corner of Harpsden, close to Shiplake and its train station. A greater level of new building has occurred in Rotherfield Peppard, and especially in the eastern part of Rotherfield Greys, which from the 19th century became a suburb of Henley. Until then Henley itself expanded little beyond its medieval boundaries, and although from the 1890s it saw substantial growth southwards, in the early 21st century it remained relatively self-contained. More modest urban expansion westwards encroached into Badgemore, another area affected by late medieval shrinkage. (fn. 73)

Economy and Land Use

The Medieval Economy

The rural economy of the area was long based on the type of mixed farming called 'sheep-corn husbandry'. (fn. 74) Extensive local woods were exploited to produce firewood and timber, and woods and commons were used for grazing and pig pannaging, although animal husbandry was not as central to the local economy as in less fertile wooded districts like the Weald. John Leland's comment that there was 'plenty of wood and corn about Henley' is as suggestive about the local economy in the 16th century as it is about the landscape. (fn. 75) As later, Henley was probably the main market in the Middle Ages, thanks especially to its role as a trans-shipment point for grain and firewood bound for London and for goods brought upstream. (fn. 76) But there were other nearby markets at Reading (a strategically located Domesday borough and England's 40th wealthiest town in 1334), Watlington (where a secondary market was chartered in 1252), and Wallingford (a major early centre in serious decline by the late 13th century), all three within a dozen miles of Henley. (fn. 77)

In the Middle Ages and long after, overall wealth was low by Oxfordshire standards. In 1334 Binfield was the second poorest of the county's 14 hundreds in terms of assessed taxable wealth per acre, although the county as a whole was then among the richest in England. (fn. 78) Settlements in the hillier north of the hundred were generally poorer than those with a greater share in the flatter land to the south (Table 1). Economic development in the Henley area was doubtless held back by low population density and limited farming output, factors in turn related to topography, poor water supply, indifferent soils, and large tracts of woodland. (fn. 79) Although Henley provided an important market, its hinterland extended well beyond the parishes covered in this volume, and included better farming country north of the hills. (fn. 80) The prosperity of the town itself was initially very modest, not least because its trade was controlled by non-resident London merchants until the Black Death. In 1334 it ranked 15th out of 19 Oxfordshire towns, and was well outside the top hundred nationally. (fn. 81)

High medieval agriculture seems to have been organized around a mixture of inclosures and small open fields, with a predominance of arable farming over pastoral husbandry. (fn. 82) In the early 14th century lords retained demesnes of differing sizes (the absentee Pipards only 60 a., but the resident Greys 300 a.), while tenant holdings varied in size from cottage plots to part or whole yardlands. Detailed analysis of local farming in the Middle Ages is hindered by the limited number of surviving manorial accounts and court rolls, especially before 1350, but serious agrarian problems had apparently set in by the 1340s, when much land lay uncultivated. In the long period of low population which lasted from after the Black Death to the 16th century demesne land was leased out and there seems to have been a restructuring and amalgamation of holdings, perhaps including inclosure of some open fields. These processes allowed a reduced number of tenants to consolidate land, and the late Middle Ages almost certainly formed the earliest phase in the emergence of the larger farms visible in the 16th and 17th centuries.

In the later 14th and 15th century the rural economy seems to have become more focused on grazing (particularly sheep farming) and wood-production, both of which were less labour-intensive than cereal farming. Henley itself briefly emerged as a market for wool; its supply zone extended far beyond the area covered in this book, but Henley-based merchants played a prominent role. (fn. 83) Pastoral farming was presumably facilitated by some reduction in the area under crops, since the grazing available on commons and in woods was of poor quality and often shared between many townships; (fn. 84) nonetheless cereal growing probably remained important. Larger flocks were kept by demesne lessees and other more substantial tenants. Those with smaller plots and fewer resources could probably afford only a few animals.

The 16th to 21st Centuries

The 16th century saw the beginning of a long phase of relative agricultural prosperity in the area, based on growing demand from London, and the continuation of Henley's role as an export centre for grain and wood. The river trade with London provided a direct market for barley and meal, and from the early 17th century Henley's burgeoning malting industry created additional demand for barley. (fn. 85) A 1587 survey suggests the same focus on barley-growing in Binfield hundred as elsewhere in the Oxfordshire Chilterns, with other crops including wheat, rye and pulses, although the scale of production seems to have been lower. (fn. 86) Farming remained mixed, but animal keeping was subsidiary to cereal production.

Already in the late 16th century many local tenants ran farms considerably larger than the county average, and by the late 18th century there had been a further concentration of land into the hands of a few leading men. (fn. 87) Farmers were unhindered by any substantial common field organization, (fn. 88) and the many farmhouses and large barns built in the 17th and 18th centuries reflect rising agrarian production and profits, notwithstanding periods of difficulty such as (for example) that caused by falling grain prices in the 1730s and 1740s. (fn. 89) Farmland was expanded through woodland clearance, (fn. 90) and from the late 17th century crop yields were increased by improved agricultural techniques, especially after c. 1780. These included more intensive marling, and the use of new fodder crops that enriched the soil and supported larger sheep flocks, thus providing more manure. (fn. 91) Even so, commercial rents remained generally modest in 1800, presumably because of the limited natural potential of the land. (fn. 92)

| TABLE 1. Population and wealth in Binfield hundred, 1086–1801 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| parish or other unit | area c. 1880 (acres) (fn. 93) | households 1086 (including slaves) (fn. 94) | plough teams 1086 (fn. 94) | taxable wealth 1334 (fn. 95) | taxpayers 1377 (fn. 96) | tax paid 1524 (fn. 97) | taxpayers 1662 (fn. 98) | population 1801 |

| Bix (including Bix Brand and Bix Gibwyn) | 3,078 | 17 | 10 | £27 15s. | 45 | £3 17s. 10d. | 17 (fn. 99) | 303 |

| Caversham | 4,879 | 43 | 17 | £102 18s. 9d. | 153 | £11 3s. 4d. | 33 | 1,069 |

| Eye and Dunsden liberty (part of Sonning) | 3,151 | 59 (fn. 100) | 22 (fn. 100) | £72 8s. 9d. (fn. 100) | 100 (fn. 100) | £3 1s. | 38 | 705 |

| Harpsden (including Bolney) | 2,021 | 34 | 12 | £37 2s. 6d. | 41 | £4 16s. 2d. | 17 | 173 |

| Henley (including Badgemore) | 1,758 | 11 (fn. 101) | 5 (fn. 101) | £60 5s. (fn. 102) | 398 (Henley borough 377) | £41 1s. 8d. | 215 (fn. 102) | 2,948 (fn. 103) |

| Rotherfield Greys | 2,928 | 20 | 7 | £37 8s. 9d. (fn. 104) | 61 | 15s. 6d. | 57 | 677 |

| Rotherfield Peppard | 2,194 | 17 | 5 | £15 11s. 3d. | 31 | £4 6s. 4d. | 23 | 317 |

| Shiplake (including Lashbrook) | 2,740 | 13 (fn. 105) | 3 (fn. 105) | £55 | 112 (fn. 106) | £3 4s. 6d. | 42 | 476 |

Despite ongoing clearance, woodland provided an important additional source of income for landowners and some tenants, albeit one which is often poorly recorded. The Stonors in particular had very extensive woods (over 2,200 a. in 1725, including in Bix and the Rotherfields), and exploited them systematically. In the late 17th and early 18th century what seem to have been annual Stonor wood sales usually generated over £1,000, mostly from fuel wood (billets and bavins) cut from woods managed as coppices-with-standards. (fn. 107) Even after deduction of labour costs this must have provided an important part of the family's income, since their rents brought in just under £1,000 each year in the 1690s. (fn. 108) Most of the wood (for domestic and industrial use) was destined for London, but some was sold locally and in the vale. (fn. 109)

Henley itself was a malting centre by c. 1600, and malting and brewing remained its chief industries, with brewing taking over from malting by the early 19th century. But Henley was never a significant industrial town: alongside its role as a long-distance trans-shipment point it was mainly important as a service centre, particularly in the 18th century with the development of coaching, and from the late 19th when (after a period of stagnation) it emerged as a fashionable resort. In addition it continued to provide a local market, albeit one with exceptionally wide connections, where goods produced in the area were sold alongside more varied items imported along the river. (fn. 110) By the early 1520s it was the third wealthiest town in Oxfordshire in terms of assessed taxable wealth, and by 1642 it was second only to Oxford. (fn. 111) Nonetheless it remained a small town, comparable in size and function with places such as Abingdon or Marlow rather than with the much larger, wealthier and more industrial Reading to the south. (fn. 112) By 1800 Henley's urban population (including houses beyond the borough boundary in Rotherfield Greys) probably totalled some 3,300; by contrast, Reading's was almost 10,000. (fn. 113)

Local agriculture seems to have remained generally healthy in the first three quarters of the 19th century, the more substantial farmers successfully weathering both the post-Napoleonic depression and Henley's mid century stagnation. After 1840 some used carriers to transport part of their produce to the new railway terminus at Reading, (fn. 114) and from 1857 they benefited from a station at Henley itself, which handled grain, fertilizer, and livestock. (fn. 115) Local woods remained valuable assets, despite continuing woodland clearance and the increasing dominance of coal as domestic fuel. (fn. 116) Stonor wood sales brought in gross revenues of c. £1,300 a year in the first half of the 19th century, (fn. 117) by this time mainly from large beech poles cut from high forest woodland. Some of the timber was used locally for a variety of purposes, including making boards, chair legs and wheel rims. However, much was sent by river, road or rail to supply Chilterns furniture factories, and the turnery and finishing trades and industrial furnaces of the capital. (fn. 118)

The late 19th- and early 20th-century agricultural recession affected the area badly. One result was a dramatic move away from labour-intensive cereal production towards dairying, with the growing populations of Reading and Henley providing markets for milk. (fn. 119) Demand for timber from local sawmills and Chilterns furniture factories continued to provide landowners with useful additional income, (fn. 120) though not enough to prevent the break-up of many local estates between 1894 and 1953. Owner-occupation of farms increased as a result of land sales, but agricultural employment continued to fall steadily. In 1941 farm rents in the area, except in Bix, were higher than the (low) Oxfordshire average, presumably because nearby urban centres provided demand for produce. (fn. 121) By the 1960s, however, farmers were struggling in the face of static profits and rising costs, (fn. 122) and many smaller producers went out of business in the late 20th century.

In Henley the 20th century brought the decline of traditional craft production, and in 2002 the long-established Brakspears' Brewery was closed. From the 1960s, however, a variety of new businesses moved to small industrial estates on the town's south side, attracted by good communications and a congenial setting. Most focused on light engineering, financial services, or computing, and though many were part of larger concerns, several became important local employers. Service, finance and retail remained dominant in the town itself. (fn. 123)

Society

Medieval Society

In the Middle Ages Henley was inhabited chiefly by craftsmen and retailers, with an important veneer of prosperous London corn merchants operating in the town before the Black Death. From the 15th century Henley-based merchants became more important, amongst them the well-connected wool merchant John Elmes (d. 1460). Such men played a prominent role in the life of the town, which was by then largely self-governed through the town guild. Lords of Henley manor were major national figures who were almost invariably absent, although some gentry may have lived in the town in the 15th century. The surrounding rural estates had a mix of resident and non-resident lords; some were involved with the life of the town, but most operated in a social and business world which crossed county boundaries and encompassed a much wider area than the immediate neighbourhood. Several were wealthy enough to establish deer parks close to their seats, like the Greys at Greys Court or the (largely absentee) Pipards in Rotherfield Peppard. (fn. 124)

Resident lords such as the Greys or Harpsdens probably exercised a degree of social control and influence in the countryside, if only through their manor courts and patronage of the parish church. But even where lords were resident, the area's dispersed settlement, the absence of heavy tenant labour services and the limited development of communal farming probably allowed local tenants substantial independence, particularly in the later Middle Ages when tenant farmers were in short supply. The great majority of the rural population comprised a mix of free and customary tenants, with holdings of varying size. There were differences in status and material prosperity from an early date (notably between slaves and villani in the 11th century), and differences in wealth seem to have become more marked in the later Middle Ages.

Society 1500–1900

By the 16th century only a few landowners remained resident: the Knollyses, who had succeeded the Greys at Greys Court, a junior branch of the Stonors, who lived at Blount's Court, and the Elmeses of Bolney. Below these leading families and some resident rectors, a considerable divide had opened between the two main elements in the population: tenant farmers, and smallholders and labourers. Most farmers, who with their families comprised a substantial portion of the small population, had secure tenure and (by contemporary standards) sizeable holdings, and seem to have been better off than the middle rank of Oxfordshire farmers. In the 17th century a large majority of local yeomen left personal estates worth over £150, with a sizeable number worth £250–£400 or more. (fn. 125) A median value of £227 from a sample of 13 late 17th-century inventories compares favourably with a median of £148 derived from a much larger sample of yeoman inventories from Oxfordshire as a whole between 1690 and 1730. (fn. 126) Many who described themselves more modestly as 'husbandmen' seem also to have been better off than those of similar standing elsewhere in Oxfordshire. Most of their wealth was tied up in grain and animals, but the most successful lived in some comfort, sleeping in featherbeds and employing a few domestic servants in their moderately large and solid houses. (fn. 127) Some of these tenant farmers augmented their leased holdings by purchasing fields and pieces of woodland, but there were few substantial owner-occupiers. (fn. 128)

Below this local farming élite was a group of smallholders and labourers who lived in much more modest circumstances, often in cramped and probably poor housing of which little survives from before the 18th century. Sixteenth- and 17th-century bequests made to the 'poor' were presumably mainly directed towards these families. Smallholders seem to have been more numerous in the Rotherfields, particularly Rotherfield Greys, where larger numbers of people carved out small green-side plots. The number of labourers increased somewhat in the 18th and 19th centuries in response to the intensification of farming, and as elsewhere many of these men and their families lived in considerable poverty. (fn. 129)

The population of Henley itself remained relatively small but modestly prosperous in the 16th and 17th centuries, with an élite (by c. 1650) of wealthy maltsters and other traders who dominated town government and society. (fn. 130) From the early 17th century the town had resident lords in the form of the lawyer and parliamentarian Bulstrode Whitelocke and his descendants, who lived at Fawley and Phyllis Court. Over the following decades a new set of mainly resident gentry moved into the surrounding rural areas, of whom most represented the new money which increasingly dominated landownership along the middle Thames. They too included lawyers such as Whitelocke's friend Bartholomew Hall, who bought Harpsden Court a mile and a half south of the town in the 1640s. Others made fortunes from trade, amongst them the Drapers of Park Place and the Freemans of Fawley Court (both just over the county boundary), or in the 18th century the Grotes of Badgemore and the Hodges family of Bolney.

Henley flourished during the 18th century, thanks to the continuing river trade and an increase in coaching traffic. The town became increasingly important as a service centre, with a resulting growth in the number of crafts and trades. Shopkeepers and tradesmen catered for travellers, locals and resident gentry, providing a variety of imported and locally produced goods, and the town also offered a range of well-established inns, many of which were updated and extended. As a result the town became the focus of a varied social scene involving local landowners, clergymen, leading merchants and professionals, many of them with strong London connections. Civic focus and pride were enhanced by the grant of a new charter of incorporation in 1722, expanding the corporation's powers, and by the building of a fine new stone bridge in the 1780s.

Changes affecting the town in the 18th century largely bypassed the surrounding rural parishes, at least beyond the gates of country houses and rectories. Socially the countryside around Henley remained an isolated backwater, with few focal points for community activities. Church attendance was often poor – only partly because of local Nonconformity – and for many living in scattered hamlets or isolated farms the numerous alehouses were probably the main source of social interaction, along with taverns in the town itself. Literacy rates remained extremely low, and the weakness of community social cohesion and control may be indicated by what were apparently high illegitimacy rates. (fn. 131) In the later 19th century vigorous reforming clergy helped sponsor musical and other activities, and supported the establishment of cricket and football clubs. Nevertheless, as in the town itself, poverty and bad living conditions remained serious problems into the early 20th century. (fn. 132)

The social life of 19th-century Henley was greatly enlivened by the establishment of an annual summer rowing regatta in 1839. The regatta, which was intended from the start to be a means of bolstering the fortunes of the town, had become an important visitor attraction by the late 1840s and a major annual event for the British upper and middle classes by the 1880s. A smattering of wealthier private residents moved into the area in the first half of the 19th century and one or two even earlier, but it was only after the construction of the branch railway line in 1857, and especially after improvements to services at the end of the 19th century, that the town and surrounding parishes became attractive to a larger number of professionals, retired military men and other wealthy individuals. Some moved into existing country houses and farmhouses, a number of which had become available thanks to the amalgamation of farms, while others bought villas in Henley's expanding suburbs. In the first decade and a half of the 20th century wealthy incomers also built large detached houses on former farmland, sold to speculators by landowners suffering from the agricultural recession. (fn. 133)

As a result of these changes Henley became a resort town and dormitory of a kind not found elsewhere in the county. As in earlier periods, the social world of these well-to-do looked to the Thames valley and London rather than to Oxford or the Midlands, from which they were separated by the Chiltern hills to the north. In many ways, however, even more dramatic social developments were still to come.

Twentieth-Century Transformation

Enormous changes occurred in the social character of the area in the 20th century, many of them concentrated in a short period after c. 1970. In some ways these represented the culmination of a longer process of gentrification dating back to the 18th and early 19th century, but their pace and scale were unprecedented. Even in 1950 there were few indications of the shape which local society would take in the following fifty years.

In the early 20th century Henley and its environs were dominated by a mixed group of richer residents. These included a few longer-established landowning families, but most were people who had made their money from various professions and businesses, and for whom the Henley area represented a country retreat. Some retained flats in London and elsewhere, but for the most part they played an active role in local life. In any case, up until the 1960s the population as a whole remained socially mixed. (fn. 134) There were many townspeople, small-scale farmers, labourers, gamekeepers and others of limited means, and considerable pockets of rural and urban poverty.

From the late 1960s and 1970s, however, the area increasingly attracted high-earning professionals, wealthy retired people and those with private fortunes. This trend – facilitated by the availability of farmhouses, converted barns and town properties – was stronger than in almost any other part of the county, thanks to Henley's suitability as an up-market leisure and service centre, the attractiveness of the surrounding countryside, and road and rail links to London. In 1974 Henley could be described as having recently become 'an affluent commuter town' after the construction of the M4. (fn. 135) Not surprisingly, local property prices rose hugely, especially from the 1980s. (fn. 136) In 2002 a building society survey found Henley to be the second most expensive town in England in which to buy a property (in terms of average house price), having risen from eighth position in 1988. (fn. 137) Prices were doubtless fuelled by the vast sums paid for houses in the town centre, and for larger residences by the river and in the nearby countryside.

This influx of new money had a profound effect on local life, particularly in the rural areas. Farmers and labourers were replaced by bankers and commuters, with farmhouses and agricultural buildings converted into luxury residences. (fn. 138) For many of the new residents the appeal of the area was the privacy offered by dispersed settlement, and few shared the enthusiasm for civic and social engagement displayed by many of their predecessors. Rather than spending the day in Henley or the surrounding parishes more and more working people drove to offices outside the area, including in Reading (14 km), Oxford (39 km) and London (62 km). (fn. 139) The limited number of local jobs and very high cost of housing made it difficult for young families to settle in the area, and the average age of inhabitants rose. These same factors ensured a low representation of ethnic minorities, especially when compared with neighbouring Reading. (fn. 140)

Religion

In the Anglo-Saxon period the area may have been ecclesiastically dependent on a mother church at Benson, but there is little direct evidence of any such link after the Conquest, except for a statement in the Hundred Rolls that Henley was a chapel of Benson. Local churches had been built by the 12th or early 13th centuries, and in some cases perhaps earlier; by c. 1200 most had achieved full parochial independence. (fn. 141) In the Middle Ages the rural churches were apparently poor and somewhat neglected, with often short-serving incumbents keen to find better livings. Henley church, with its numerous side altars and chapels, was better supported by assistant clergy, and seems to have been a focus for vibrant guild activity in the late Middle Ages. Like some neighbouring places in the Chilterns the town became a focus of Lollardy in the later 15th century, due partly to its strong London trade links and its position on the fringe of both county and diocese (the latter centred on Lincoln until the 1540s). But the majority of the population were probably unaffected, and there is no evidence that the town as a whole embraced the Reformation with any particularly marked enthusiasm.

From the 1660s the Chilterns became one of the chief focuses for Protestant Nonconformity in Oxfordshire, though how far this was related to the earlier tradition of Lollardy is unclear. A number of local landowners were Nonconformists, notably the Halls at Harpsden, and Nonconformity flourished intermittently across the area. This was particularly true in Henley, where an Independent (later Congregationalist) meeting house was established in the 1670s, and other meetings flourished at Rotherfield Peppard and for a time at Harpsden. The Independents remained the strongest sect, with Wesleyans making little early progress. Henley was less dominated by Nonconformity than some other Oxfordshire towns, however, and by the 18th century the area as a whole was characterized by a rather perfunctory conformity. Apathy and poor church attendance, exacerbated by dispersed settlement, seem to have been more characteristic than strong religious feeling, and though many rectors were resident at what were by then valuable livings, few demonstrated any great zeal. Catholicism found little following except in Rotherfield Peppard, where the Catholic Stonors had a minor residence until the early 18th century.

The Anglican church seems to have been poorly served in the early 19th century, but benefited from the widespread revival of religious life from the 1850s and 1860s. For many parish churches this entailed an increase in the number of services and, in some cases, a degree of controversy over a more High-Church style. (fn. 142) Attendance seems to have increased amongst congregations of all denominations, though a weak showing amongst the poor remained a concern. Religious fortunes during the 20th century were predictably more mixed, though the variety of the town's religious life survived into the early 21st century, when five separate denominations retained places of worship. (fn. 143) The rural parish churches continued to attract reasonably sized congregations, although frequently numbers were bolstered by non-parishioners. No non-Christian religious institutions were established, reflecting the very limited presence of ethnic minorities.

Local and Hundredal Government

In the Middle Ages the places covered in this volume formed part of Binfield hundred, one of the 4½ Chiltern hundreds in the soke of the royal manor of Benson or Bensington. (fn. 144) The link between Bensington manor and this group of hundreds stemmed from the Anglo-Saxon period, when the whole area was associated with the large royal estate focused on Benson in the clay vale below the Chilterns. (fn. 145) This multiple estate was mostly broken up before the Conquest, and by 1066 the king retained only Benson and some other outlying pieces of land, including Henley. The division of the estate is poorly documented but seems to have occurred piecemeal, from the 9th century and possibly earlier. (fn. 146) By the 11th century many smaller estates had been created, often forming units of 5 hides or multiples thereof, and these formed the basis of the later ancient parishes.

Binfield hundred was not mentioned in Domesday Book, and its early development is difficult to trace. Thirteenth-century and later evidence shows that the medieval hundred included the same places as in the 19th century, when its area was 22,749 a., or 4.7 per cent of the county. (fn. 147) The early county map-makers seem to have made a number of mistakes in their depictions of the (wooded) north and north-western part of the hundred boundary, not least by cutting off the northern arm of Bix, an area which can be shown to have been part of Bix parish (and therefore Binfield hundred) in the 16th and 17th centuries. (fn. 148)

The administration of Binfield and the other Chiltern hundreds was closely linked with that of the honor of Wallingford from an early date. (fn. 149) After the Conquest the 4½ hundreds usually followed the descent of Bensington manor, which was attached to the honor in 1244. The link was maintained through its re-fashioning as the honor of Ewelme in 1540 up until 1847, after which the honor courts ceased to function. From 1337 to 1540 the honor was formally annexed to the duchy of Cornwall, though it remained separately administered. The honor was closely supervised under the Black Prince (d. 1376), whose servants were vigilant in pursuing financial dues from his feudal rights as overlord of many local landowners. Thereafter it was mainly held by the Crown or by the Prince of Wales, and until the mid 15th century it provided an important focus of lordship for local gentry. The honor's influence was perhaps at its height during the stewardship of the able and well-connected Thomas Chaucer (1399–1434). After his death its impact on local affairs was less pronounced, and its significance gradually declined. (fn. 150)

In the Middle Ages the places covered in this volume were divided into three categories in terms of their relations with the honorial and hundred courts. Several vills belonged to fees of the honor of Wallingford, and therefore answered to the honor courts; in the 13th century these were Bix Brand, Harpsden and Rotherfield Peppard (though the lords of Bix Brand sometimes held their own leet courts). By the 15th century these three vills had been joined by Padnells: part of the manor of Lewknor in the west of Rotherfield Greys, which included the settlements of Highmoor, Satwell, and Witheridge Hill. The tithing group for Bix Gibwyn initially answered to the view of frankpledge at the hundred court, which probably met on Binfield Heath in Shiplake; by the later 18th century, however, Bix Gibwyn had joined the places listed above as part of the Ipsden division of the honor of Ewelme. (fn. 151) Bolney, Badgemore and the eastern part of Rotherfield Greys belonged to manors exempt from suit at higher courts. (fn. 152) Although they had separate tithing groups, the two Bixes were frequently regarded as a single unit, and Rotherfield Greys and Badgemore were regularly linked for tax purposes. (fn. 153)

In the later Middle Ages the main business of the honor's annual view of frankpledge, then held at North Stoke, was the regulation of mill tolls and the assize of ale. (fn. 154) In the 16th century the tithingmen from each vill were joined at the view by constables, who were originally manorial officials mentioned as early as the 14th century. (fn. 155) In the 18th and 19th centuries the combined view and court leet was held at various locations, including the Dog public house at Rotherfield Peppard. (fn. 156) By then the courts brought in minor revenue from fines and occasionally dealt with small matters such as repairs to local footbridges and boundaries. The hundred court dealt mainly with pleas of debt and the assize of ale in the early 15th century, as well as a few cases of trespass and assault, but seems to have rapidly declined in the late 15th century. (fn. 157) Until the 17th century a wide range of matters was also dealt with in local manor courts. (fn. 158)

By the 18th century the main business of local government had passed from the manorial courts to parish officials, chosen in vestry meetings which were usually dominated by local landowners and leading yeoman farmers. Their main concerns were poor relief (until the creation of Henley poor law union in 1834), repair of roads, maintenance of churches and schools, appointment of parish officers, and the setting of rates. (fn. 159) Following the 1894 Local Government Act civil responsibilities passed to the new Henley Rural District Council and its associated parish councils, and under local government reorganization in 1974 the area's civil parishes became part of South Oxfordshire District. (fn. 160) Henley itself was largely self-governing from the Middle Ages, the merchant guild assuming wide powers including responsibility for the bridge and parish church. It was formally incorporated in 1568 and again in 1722. (fn. 161)

Poor Relief

Poor relief was initially organized on a parochial basis and through private charitable bequests. Henley had an almshouse by the 1450s, and others were founded there in the 16th and 17th centuries. In the 18th century workhouses were set up in Henley and Rotherfield Greys, although the latter was short lived. Bix and Rotherfield Peppard were among several parishes to benefit in a minor way from an almshouse established by Sir Francis Stonor (d. 1625) in Upper Assendon in 1620, which remained in use until the 1940s. (fn. 162) From 1834 the main responsibility for the poor passed to the newly established Henley poor-law union, which included 21 parishes divided into three districts. (fn. 163) Nevertheless local initiatives continued, funding coal and clothing clubs, charitable relief, and friendly societies.

The worst period of social distress in modern times was during the high bread prices of the early 19th century. (fn. 164) At that time the Chilterns region had a higher proportion of paupers than any other part of Oxfordshire, which was itself one of the English counties with the least industry and the greatest poor-relief problems. The Chilterns suffered particularly acutely as a mainly inclosed arable region with good transport links, which was closely geared to commercial agriculture; such conditions opened a stark divide between prosperous farmers and irregularly employed landless labourers on low wages. (fn. 165) Detailed analysis for the area covered here is hindered by lack of vestry minutes or overseers' papers for most parishes in this period, but in 1803 and 1813–15 a far higher proportion of the population in Harpsden and Bix received relief than in the other parishes of the hundred. (fn. 166) Presumably this was because there were even fewer smallholders and non-agricultural by-employments in these two parishes than elsewhere in the area. (fn. 167) In Henley, poor-relief costs in the late 18th and early 19th century were amongst the highest of any Oxfordshire town, until reduced by a general tightening up of rating and relief in the 1820s by a newly created select vestry. (fn. 168) Serious pockets of urban and rural poverty remained in the later 19th and early 20th centuries, and even in the late 20th century there was a small amount of relative deprivation, for instance amongst long-resident elderly people on low incomes.

Buildings and the Built Environment

Henley originated as a medieval planned town, and retains a substantial number of high-quality late medieval timber-framed buildings, many of them hidden behind later façades. Nevertheless, much of its architecture, like that of many other towns in the Thames valley, is a product of a long period of general prosperity from the 18th to early 20th centuries. In Henley there were two main phases of rebuilding during high points of affluence: the first during the 18th and early 19th century, when the town was a major coaching centre, and the second from the later 19th century to the First World War. Eighteenth-century work has left a large number of attractive Georgian brick and stucco buildings in place of (or encasing) the timber-framed houses that dominated the town in 1700. (fn. 169) The prominence of these buildings along the main streets gives the town a similar feel to nearby Marlow. Both were places whose architecture was strongly influenced by London fashions, the ready availability of locally produced bricks, and the absence of suitable building stone. (fn. 170)

Brick, which made its first appearance in the town in the later Middle Ages, continued to dominate later building work, including shops and houses on the main streets as well as in the new suburbs. The major work of the early 19th century was the construction of terraced houses in the west and south, catering for a rapidly growing urban population whose numbers were bolstered by immigration of poor families from surrounding rural areas. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries a much larger number of new houses were built to the south of the town, some of them working-class terraces, but others aimed at professionals and the prosperous middle classes. As at Marlow and Cookham, the later 19th century also saw the building of smart apartments and up-market boathouses along the river front. (fn. 171) Many later buildings are neo-Georgian or neo-Tudor in style, and there has been some over-prettification of earlier houses.

In the rural parishes a similarly limited range of building materials helps bring a relatively harmonious appearance to houses which vary a good deal in size, style and date. A few of the oldest farmhouses are timber-framed, their walls probably originally filled with wattle and daub. But from the 17th and especially the 18th century brick and flint, particularly brick, became the commonest building materials, having been reserved at earlier dates mainly for high-status buildings such as manor houses and churches. Today brick-built houses are dominant (although occasionally rendered), reflecting the fact that the surviving rural building stock dates mainly from the 18th century and later, with a very large part of it from the 19th and 20th centuries. (fn. 172)

From the Middle Ages to the early 20th century bricks were produced at Nettlebed and other nearby kilns, but latterly more uniform mass-produced bricks have been brought in from larger production centres. Older roof tiles are made mainly from local clay, with some use of Welsh slate on buildings mostly post-dating the construction of the railway. Thatch was used for more modest homes and outbuildings in earlier periods, and in a few places survives, but since the early 19th century it has rarely been used. (fn. 173)

The rural housing stock can be divided into three main types: first, thinly scattered farmhouses and medium-sized country residences of the 16th to 20th centuries; second, loosely grouped cottages and houses of similar date, mostly unexceptional but frequently detached in substantial plots; and finally, small infills of relatively dense suburban housing of the 19th to early 21st centuries. The vast majority of buildings are post-medieval, except for the parish churches, surviving manor houses, and a handful of farmhouses.

Most older buildings, although solid and attractive, were originally fairly modest: apart from one or two country residences and farmhouses, the gentrified architecture of Henley petered out at the eastern end of the Fair Mile. Even manor houses and gentlemen's residences were generally grand and well-built only by provincial standards, with the striking exception of Greys Court and to a lesser extent Harpsden Court, while the best farmhouses were comfortable but unspectacular. In 1847 the building stock in Bix was characterized as 'a few mean-built houses', (fn. 174) and much the same would have applied elsewhere. The churches too (Henley's excepted) were mainly very small and rather shabby, until rebuilt and extended in the mid to later 19th century. Some farmhouses were extended piecemeal in the 17th to early 19th centuries, but after the period of agrarian difficulties in the late 19th and early 20th century many farm buildings and cottages were in a dilapidated state.

The picture changed a great deal thereafter. A number of grander private houses were built in the early 20th century, and from the 1960s older farmhouses and cottages were frequently updated and made more luxurious. Conversion of barns and other farm outbuildings into luxury homes followed on a large scale from c. 1980. Modern suburban houses were usually built to standard designs, but include a number of more ostentatious 'executive' homes. There are also pockets of plain, red-brick early 20th-century council houses, many now privately owned.