A History of the County of Gloucester: Volume 7. Originally published by Oxford University Press for Victoria County History, Oxford, 1981.

This free content was digitised by double rekeying. All rights reserved.

'Chedworth', in A History of the County of Gloucester: Volume 7, ed. N. M. Herbert (Oxford, 1981), British History Online https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/vch/glos/vol7/pp163-174 [accessed 19 April 2025].

'Chedworth', in A History of the County of Gloucester: Volume 7. Edited by N. M. Herbert (Oxford, 1981), British History Online, accessed April 19, 2025, https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/vch/glos/vol7/pp163-174.

"Chedworth". A History of the County of Gloucester: Volume 7. Ed. N. M. Herbert (Oxford, 1981), British History Online. Web. 19 April 2025. https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/vch/glos/vol7/pp163-174.

In this section

Chedworth

Chedworth, one of the more populous Cotswold parishes, lies 10.5 km. NNE. of Cirencester and covers 1,935 ha. (4,781 a.). (fn. 1) It is bounded on the south-east by the Foss way and on the east and north-east by the river Coln and is fairly compact in shape except for a peninsula in the north-west extending down to the river Churn.

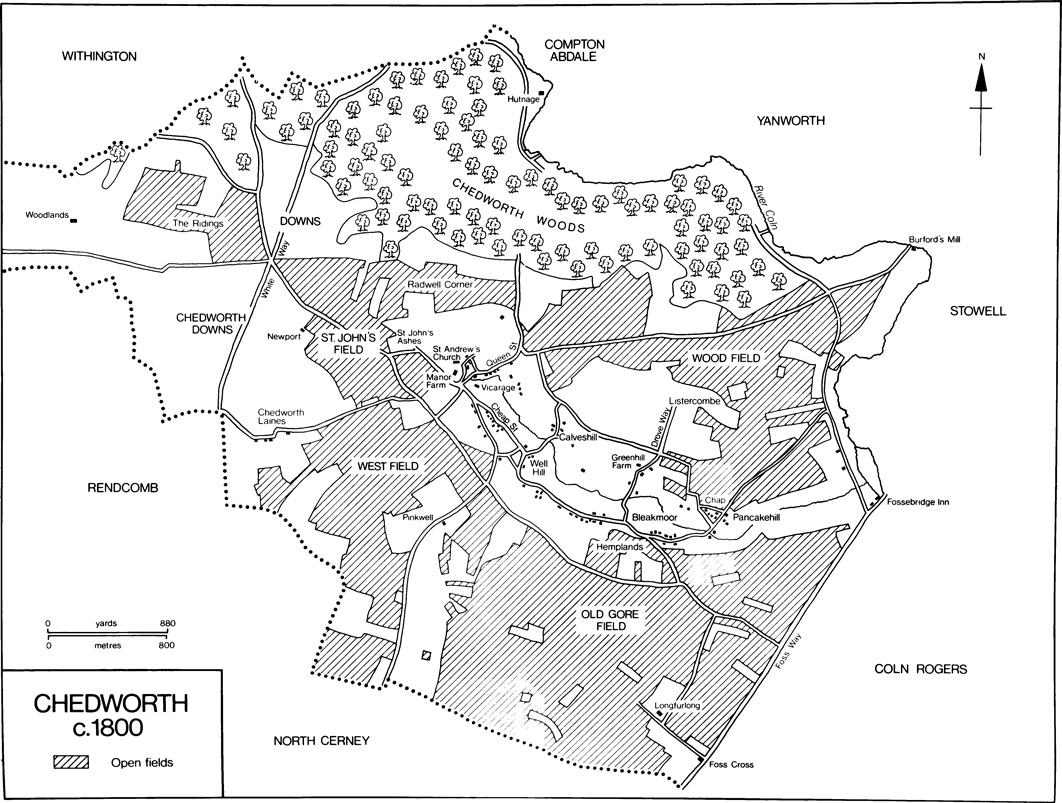

Much of the parish lies on the high Cotswolds at 180–250 m. but a broad valley, formed by a tributary of the river Coln, is its central feature and on the north and east the land falls fairly steeply to the Coln. The bottom of the Marsden valley in the north-west peninsula is on the Upper Lias, which is overlaid in the rest of the parish by successive strata of the Inferior Oolite, fuller's earth, and the Great Oolite; along the valley sides the fuller's earth forces out numerous springs which have contributed to the dispersed nature of the settlement. (fn. 2) The high ground on each side of the central valley was once farmed as large open fields, which, together with Chedworth Downs in the north part of the parish, were inclosed in 1803. (fn. 3) An airfield was laid out on the former downs in 1940; intended originally for fighters, it was later used mainly by aircraft engaged in bombing practice over the Severn estuary. (fn. 4) It reverted to farm-land after the war and some of its buildings were used for pig- and poultry-farming. (fn. 5)

A broad belt of woodland, occupying the slopes in the north-east and north, has long been a major feature of the landscape. It is likely, however, that parts of it, lying above the Coln opposite Yanworth parish, were temporarily cleared for cultivation during the period of pressure on land in the early Middle Ages, when a small hamlet called Gothurst probably existed by the river in that area. (fn. 6) The names Wheatley, Peasley, and Chedworth Long Acres, later given to parts of the woodland there, (fn. 7) suggest that, as does the comparatively small acreage of woodland, 240 a., recorded on the two parts of the manor in the early 14th century. (fn. 8) The woods were evidently a valuable asset in 1398 when a grant or mortgage of them was supported by a bond for £400; (fn. 9) in the late 15th century, when the annual profits were c. £10, they were carefully managed for the manor with a regular policy of replanting and protecting the young trees. (fn. 10) During the 15th century and the early 16th the office of keeper of the woods was sometimes used to reward royal servants. (fn. 11) In 1618 there were 629 a. of woodland on the manor, including the 60-a. Dean's wood (fn. 12) near the north boundary which had been acquired by the lord in 1611, having belonged to the part of the manor held by the dean and canons of St. Mary's College, Leicester, in the late Middle Ages. (fn. 13) The woods, extended at 801 a. in 1842, (fn. 14) all remained with the manor until 1923 when those adjoining the Coln passed with Stowell Park to the Vestey family and those in the north part of the parish became divided between the Chedworth Manor farm, Woodlands farm, and Cassey Compton estates. (fn. 15) The effect of extensive felling during the two world wars (fn. 16) was repaired by replanting, and the woods retained their former extent in 1978, when those on the Stowell Park estate were still much used for rearing game.

Chedworth is widely known for its Roman villa, one of the most extensive to be uncovered in England. The villa, which is situated in the woods in the north-east part of the parish, was found in 1864 and exposed by James Farrer, whose nephew Lord Eldon, the owner of the land, roofed over some of the remains and built a museum (fn. 17) and later employed a caretaker for the site. (fn. 18) The villa was transferred to the National Trust in 1924. (fn. 19) The parish has several other Roman sites, including a temple downstream from the villa and another villa in Listercombe discovered c. 1760; (fn. 20) another site is presumably recalled by the name Chestells given to part of a former open field north of Longfurlong Farm. (fn. 21)

Chedworth c. 1800

The Foss way, turnpiked in 1755, (fn. 22) has always been the main thoroughfare touching the parish, and a lesser Roman road from Cirencester, the White way, crosses the high downland of the north part of the parish before descending to the Coln as Tunway Lane. (fn. 23) On the downs, where a hand-and-post stood in 1803, the White way met a number of local roads (some of which were partly obliterated by the airfield), (fn. 24) and the downs appear to have once been a focal point for traffic in that part of the Cotswolds. The name Newport given to a house near by has suggested the existence of a wayside market in the Middle Ages, (fn. 25) and a beacon stood close by in 1623. (fn. 26) Further south-east a clump of trees called St. John's Ashes, one of the few landmarks included by Saxton on his map of the county in 1577, (fn. 27) evidently marked the site of a medieval chapel; some carved stonework was excavated at the site in 1852 (fn. 28) but no documentary record of the chapel has been found before the early 18th century when some ruins were apparently still visible. (fn. 29) The position seems an unlikely one for a chapel of ease, though the fact that the site was part of the vicar's glebe in 1623 may suggest that; (fn. 30) the chapel is more likely to have been built to serve travellers. Although the ash trees at the site had long since disappeared, a line of tall beeches standing along the road to the west still made that high point of the Cotswolds a significant landmark in 1978.

In the southern half of the parish the road-pattern is fairly complex as a result of the sprawling nature of the village. The road by Pinkwell towards Calmsden was one of the more important, being the main route from the village towards Cirencester in 1623, and another road mentioned in 1623 was that called the port way, (fn. 31) running through the open fields by Pinkwell and Longfurlong to form the road junction at Foss Cross. The port way, which was still in use in 1777 (fn. 32) but in 1978 survived only in short stretches, was presumably part of a route from Chedworth Downs towards Fairford and Lechlade. Also recorded in the early 17th century and apparently still in use in the early 19th was Listercombe drove-way which crossed the valley of that name to a landmark called Horsley's Ash above Greenhill Farm, (fn. 33) where it survived in 1978 as a wide green lane. The significance of the drove-way is not clear but it may have formed part of a route linking the White way in Compton Abdale to the Welsh way at Barnsley or Ready Token; it presumably continued across the Chedworth valley by the lane called Green Lane (fn. 34) and met the port way at Longfurlong.

The Midland and South Western Junction railway, providing a rail link between Cirencester and Cheltenham, was built across the parish in 1891 with stations in the village and near Foss Cross. The line was closed in 1961. (fn. 35)

Chedworth village was established at the head of the central valley where the church and manor-house stand on the hillside by a copious spring. The village was probably confined in early times to the area that was later distinguished as Upper End, (fn. 36) based on Queen Street (formerly Blackwell's Lane) (fn. 37) and Cheap Street. (fn. 38) The former runs across the valley below the church and originally continued over the hill to provide access to outlying settlements in the Coln valley, while the latter runs southwards along the west side of the central valley. Both those streets are fairly closely built up with cottages, though none now apparently older than the late 17th century. During the late 17th century and the 18th the village developed in a sprawling fashion along the valley for c. 2 km. with scattered cottages and small farmhouses on the north-east side and a more continuous belt of houses along the road on the south-west side. At the far end at Pancakehill where the valley narrows again the village ends in a more concentrated group of cottages with a Congregational chapel established in the mid 18th century. Most of the houses along the valley are stone-built cottages and small farm-houses of the 18th century and early 19th but there are a few farm-houses of slightly earlier date, including Old Farm, a substantial gabled house of the 17th century near the south end of Cheap Street, and Greenhill Farm, a house of c. 1700 on the opposite side of the valley. On the southwest side there was some infilling with modern houses in the mid 20th century and many of the cottages of the village were restored and enlarged at that period, in some cases by taking in former outbuildings.

In early medieval times there were a number of outlying dwellings in the woodland area of the north part of the parish, most of which were abandoned during the period of general contraction in land use in the earlier 14th century. In 1341 it was reported that 16 tenants in Woodlands and Gothurst had left their holdings. (fn. 39) Woodlands was evidently a small hamlet in the north-western peninsula of the parish; its inhabitants were presumably tenants on the Woodlands estate, the capital messuage of which was the only dwelling that survived into modern times. The name Gothurst does not survive but its probable location was beside the river Coln in the north-east part of the parish, near the Roman temple site. Edric's Mead in Gothurst, a meadow that was sold to Winchcombe Abbey in 1265, (fn. 40) has been identified, on what evidence is not known, with the meadow below the temple (fn. 41) and the name Gothurst survived until at least the 16th century for a watermill, (fn. 42) which may have stood at the end of the straight, and probably man-made, stretch of river there. Further upstream the late-19th-century cottage called Hutnage is probably on the site of another ancient dwelling, for a family surnamed de Hodeknasse was recorded in 1236 and later in the Middle Ages. (fn. 43)

At Fossebridge on the east side of the parish the earliest dwelling recorded on the Chedworth side of the Foss way was a capital messuage owned and occupied by a branch of the Dutton family in 1634 (fn. 44) and until at least 1672. (fn. 45) It is possible that the house later became the inn, though the present substantial inn building dates from the late 18th century. The inn had opened by 1759 and was then known as the Lord Chedworth's Arms, (fn. 46) changing its name to the Fossebridge inn in the early 19th century. (fn. 47) Adjoining the inn are a small farm-house and some cottages and there are a few dwellings, mainly of the 20th century, on Raybrook Lane, leading northwestwards from Fossebridge.

In the south and west parts of the parish a few scattered dwellings were built in the 18th century on inclosures from the open fields. Longfurlong (or Newman's) Farm, a substantial farm-house on the port way near Foss Cross, was built on one such inclosure before 1751 (fn. 48) and the establishment of the small roadside group of cottages at Chedworth Laines, south of Chedworth Downs, had begun by 1746. (fn. 49) Pinkwell, on the Calmsden road, and Fields Farm, north of Longfurlong, were also built before the general inclosure of the open fields in 1803. (fn. 50) Setts Farm, built before 1824, (fn. 51) was apparently the only farm-house established as a result of the inclosure. In the mid 20th century part of Fields Road running above the village on the south-west side of the valley was developed with bungalows, and a few groups of council houses were built in the same area of the parish, the largest group standing near the junction of Fields Road and the road up from the valley.

Thirty inhabitants of Chedworth were enumerated in 1086. (fn. 52) Thirty-one people were assessed for the subsidy in 1327 (fn. 53) and at least 72 for the poll tax in 1381. (fn. 54) There were said to be c. 160 communicants in the parish in 1551, (fn. 55) 40 households in 1563, (fn. 56) 200 communicants in 1603, (fn. 57) and 100 families in 1650. (fn. 58) About 1710 the population was estimated at c. 500 inhabitants in 150 houses (fn. 59) and c. 1775 the figure of 787 inhabitants in 181 families, presumably drawn from a fairly careful local census, was given. (fn. 60) In 1801 there were 848 people in 191 houses and by 1831 the population had risen to 1,026. During the remainder of the century there were small fluctuations but with a general downward trend; there were 962 people in 1871 and 885 in 1901. In the first 30 years of the 20th century there was a more rapid and consistent decline, reaching 614 in 1931. New building brought about some recovery after the Second World War and the population stood at 708 in 1971. (fn. 61)

Besides the Fossebridge inn there was also the Hare and Hounds on the Foss way at Foss Cross which had opened by 1835 (fn. 62) and possibly by 1777. (fn. 63) By 1891 there were also three public houses in Chedworth village, of which only the Seven Tuns, (fn. 64) below the church, survived in 1978. A friendly society met at the Fossebridge inn in 1759 (fn. 65) and there were two in the parish during the middle years of the 19th century. (fn. 66) Plans to establish a village reading-room were made in 1913 (fn. 67) and from that time or soon afterwards the old Sunday school building near the church was used for that purpose. (fn. 68) A building transferred from the disused airfield at Rendcomb was opened as a village hall, affiliated to the Y.M.C.A., in 1920 (fn. 69) and in 1976 a large new hall was built above the village by Fields Road. (fn. 70) In the later 19th century Chedworth supported two separate village bands, one of them attached to the Primitive Methodist chapel. They were replaced in 1905 by a single band which, as the Chedworth silver band, later became well known in the district. (fn. 71) An annual horticultural show had been started by 1896. (fn. 72)

Manors and Other Estates

Between 779 and 790 Aldred, under-king of the Hwicce, granted 15 cassati at Chedworth to Gloucester Abbey. The grant was confirmed by King Burgred of Mercia in 872 (fn. 73) but the land had been lost to the abbey by the reign of Edward the Confessor when it was held by one Wulward. After the Conquest it was probably granted to William FitzOsbern (d. 1071), earl of Hereford, whose foundation Lire Abbey (Eure) in Normandy became owner of the church. William's son Roger de Breteuil owned the manor of CHEDWORTH until his rebellion in 1075, and in 1086 the Crown held it. (fn. 74) It may have been granted to Henry de Beaumont, created earl of Warwick in 1088, (fn. 75) and was certainly held by Henry's son Roger (d. 1153), who gave land in the parish at Marsden to Bruern Abbey (Oxon.). (fn. 76) Roger's son William (d. 1184) succeeded to Chedworth (fn. 77) but it was later taken by the Crown, from which William Turpin held it at farm between 1194 and 1200. (fn. 78) Waleran, earl of Warwick, owned the manor, however, at his death in 1203 or 1204 and it was retained in dower by his widow Alice, (fn. 79) passing later to their son Henry (d. 1229). (fn. 80)

During the remainder of the 13th century the history of the descent of the manor is complicated by the apparently conflicting dower rights awarded to successive countesses of Warwick. Richard Siward, who married Philippe, widow of Earl Henry, held the manor before 1233 when Henry III granted it during pleasure to two of his crossbowmen, but soon afterwards the king gave full seisin instead to Henry's son Thomas. (fn. 81) At Earl Thomas's death in 1242, however, Siward, whose marriage to Philippe was annulled that year, was said to hold Chedworth for life as 1 knight's fee (fn. 82) and in the same year he had a grant of free warren in the manor. (fn. 83) In 1261 Philippe claimed two-thirds of the manor as dower against John du Plessis, earl of Warwick, who conceded her right and agreed to hold her share from her at an annual rent of £10. Under the agreement the two-thirds should at John's death in 1263 have reverted to Philippe, (fn. 84) who died in 1265. The other third was apparently held in dower by Ela, widow of Earl Thomas: she had a grant of free warren at Chedworth in 1251 (fn. 85) and in 1265 she and her husband Philip Bassett had life-grants of her third of the manor from William Mauduit, earl of Warwick, (fn. 86) who had presumably succeeded to the rest of the manor on Philippe's death. Mauduit died seised of the manor in 1268 (fn. 87) and his widow Alice was conceded it in dower by the heir to the earldom, William de Beauchamp, (fn. 88) who held it in 1285. (fn. 89) Ela, whose right was confirmed by the Crown in 1269, (fn. 90) may, however, have retained her third until her death in 1298 a few months before William de Beauchamp. (fn. 91)

During the next 150 years the manor descended in direct line with the earldom of Warwick, (fn. 92) except that between 1317 (fn. 93) and 1326 (fn. 94) it was held by Hugh le Despenser the elder during the minority of Thomas de Beauchamp, earl of Warwick, and between 1397 and 1399 during the forfeiture of Thomas, the next earl, it was held by John Montagu, earl of Salisbury. (fn. 95) Henry, duke of Warwick (d. 1446), settled the manor in dower on his wife Cecily, (fn. 96) on whose death in 1450 it passed to Richard Neville (fn. 97) (d. 1471), earl of Warwick. George, duke of Clarence, Richard's son-in-law, held Chedworth at his death in 1478. (fn. 98) Richard's widow Anne was restored to the family estates in 1487 but regranted them to the Crown. (fn. 99) In 1489, however, Chedworth was among manors granted to Anne for life. (fn. 100)

The Crown retained Chedworth manor from Anne's death in 1492 until 1547 when it was granted to John Dudley, newly created earl of Warwick. (fn. 101) Dudley, later duke of Northumberland, settled it on his son John and his wife Anne, but it was forfeited to the Crown after the events of 1553. Anne was later restored to the manor and in 1560 her second husband Sir Edward Unton was granted title to the manor in his own right from her death. (fn. 102) He conveyed the manor in 1569 to John Tracy of Toddington (fn. 103) but the conveyance may only have transferred the reversion after Anne's death, which occurred in 1588 when she had been a lunatic for some years. (fn. 104) John Tracy, who was knighted, was succeeded at his death in 1591 by his son, also Sir John, (fn. 105) who in 1608 sold the manor-house and demesne land to John Bridges, William Bridges, and Thomas Howse and the manor to William Higgs of London. Higgs (d. 1612) was succeeded by his son Thomas Higgs of Colesbourne. The three owners of the demesne sold it in 1616 to Sir Richard Grobham of Great Wishford (Wilts.) (fn. 106) who bought the manor in 1618 from Thomas Higgs and a group of Londoners, apparently Higgs's creditors. (fn. 107)

Sir Richard Grobham (d. 1629) settled Chedworth on his wife Margaret with reversion to a nephew George Grobham, (fn. 108) but the manor apparently passed before 1652 to another of his nephews John Howe, who was made a baronet in 1660. (fn. 109) Sir John's son Sir Richard Grobham Howe owned Chedworth in 1672 (fn. 110) and was succeeded at his death in 1703 by his son Sir Richard Howe (fn. 111) (d. 1730). It passed to Sir Richard's cousin John Howe of Stowell (fn. 112) who was created Lord Chedworth in 1741 and died in 1742. The manor and title descended successively to John's sons John Thynne Howe (d. 1762) and Henry Frederick Howe (d. 1781) and to their nephew John Howe (d. 1804). The last Lord Chedworth devised his estates to trustees for sale, (fn. 113) and Chedworth together with Stowell and other adjoining manors was bought in 1812 by the judge Sir William Scott. (fn. 114)

Sir William was created Lord Stowell in 1821 and died in 1836 when his estates passed to his daughter Marianne, wife of Henry Addington, Viscount Sidmouth. The viscountess (d. 1842) was succeeded by her cousin John Scott, 2nd earl of Eldon. (fn. 115) The estate in Chedworth then comprised 1,973 a., (fn. 116) to which the earl added another 280 a. by purchase from William Dyer in 1846; (fn. 117) Dyer had bought part of his estate in 1812 from Lord Chedworth's trustees and another part in 1813 from Joseph Pitt who had amassed it by a series of small purchases between 1802 and 1808. (fn. 118) The earl (d. 1854) was succeeded by his son John, (fn. 119) who put Chedworth up for sale with the rest of his Stowell Park estate in 1923. The smaller farms were all bought then by their tenants but 578 a., mostly woodland, were bought with Stowell by Samuel Vestey, heir to Lord Vestey, and 850 a., comprising Chedworth Manor farm and another large tract of woodland, (fn. 120) was bought by the Revd. John Green (d. 1944). The Revd. John was succeeded by his brother Capt. Henry Green, who had farmed the estate for some years, and Capt. Henry's son, Mr. J. D. F. Green, owned and farmed Manor farm in 1978. (fn. 121)

The ancient manor-house of Chedworth, recorded from 1268, (fn. 122) was at Manor Farm beside the church. The small central range of the present house retains one upper cruck truss and probably formed part of a medieval hall. To that range adjoins a large 17th-century kitchen with some additional 19th-century service rooms and, on the south-east, a long cross-range of c. 1700, incorporating some older walling. The relatively small size of the house reflects the fact that for most of its history it was used as a farm-house. Hugh Westwood, the lessee of the site and demesne of the manor from 1521, (fn. 123) who was usually styled of Chedworth, presumably lived in the manor-house, (fn. 124) but the only lord of the manor recorded as resident was Sir Richard Grobham Howe who appears to have used the house for a period in the late 17th century. (fn. 125) From the middle of that century, however, the lords were usually resident locally at Cassey Compton (in Withington) or at Stowell Park.

A third part of the manor of Chedworth (fn. 126) was given by William de Beauchamp, earl of Warwick, to his daughter Isabel on her marriage to Patrick de Chaworth (d. c. 1283). Their daughter Maud married Henry of Lancaster (fn. 127) who gave the estate for life to his brother Thomas, earl of Lancaster. On Thomas's execution in 1322 it was briefly forfeited before being restored to Henry, (fn. 128) who succeeded to the earldom and died in 1345. Henry's son Henry, duke of Lancaster, gave the estate in 1355 to the hospital of St. Mary at Leicester, (fn. 129) which he raised to the status of a collegiate church. At the dissolution of the college in 1548 (fn. 130) the manorial rights over the estate and the bulk of the land were re-united with the other part of the manor by a grant to John Dudley, earl of Warwick. (fn. 131)

The estate called WOODLANDS in the northwest part of the parish was probably that which Richard Atwood (de Bosco) held from the earl of Warwick in 1268 by the serjeanty of service in the earl's pantry. (fn. 132) The serjeanty estate, comprising a plough-land, was held by another Richard Atwood in 1315 (fn. 133) and John Atwood held an estate at Woodlands in 1386. (fn. 134) The latter was apparently the John Atwood of Gloucestershire who suffered oppression at the hands of Anselm Guise and James Clifford, his estates being forcibly occupied by Guise for some seven years. John recovered his estates in 1402 but in 1405 he was murdered by an assassin hired by Clifford. (fn. 135) In the early 15th century Woodlands seems to have been held by William Daffy. (fn. 136) About 1486 the owner of the manor took possession of the estate on the ground of a supposed reversionary interest (fn. 137) but Sir Walter Dennis later proved his title and recovered the estate in 1496. (fn. 138) Woodlands, or part of it, was later acquired by the younger Sir Edmund Tame, presumably by his marriage to Catherine Dennis. (fn. 139) It was retained by Catherine after Sir Edmund's death 1544, the reversion being settled on his sister Margaret and her husband Sir Humphrey Stafford, (fn. 140) and it apparently passed with Rendcomb manor to Sir Richard Berkeley. (fn. 141) In 1612, however, Woodlands was owned by Jasper Meyrick of Wick Rissington who then made a settlement for the benefit of his children, and in 1647 the estate was settled on trustees to provide for the maintenance of William Clent of Gloucester and Bridget his wife. (fn. 142)

By 1682 the Woodlands estate had passed to James Mitchell of Harescombe and Bridget his wife who settled it from after their deaths on the marriage of their son James (d. by 1704). The estate was partitioned among the three daughters of the younger James, Mary who married George Small of Nailsworth, clothier, Elizabeth who married Jacob Eltom of Bristol, merchant, and Bridget who married Samuel Clutterbuck of Brimscombe, clothier. Jacob and Elizabeth sold their third share in 1711 to George Small (d. c. 1736) who devised his two-thirds to a kinsman John Small, who was succeeded before 1749 by his brother Richard. (fn. 143) Richard Small sold his share in 1752 to Henry Tuffley, who bought the other third the following year from William Clutterbuck of Bristol, merchant, son of Samuel. Henry Tuffley's mortgagee, Edward Wilbraham, (fn. 144) a Cirencester wool-stapler, was in possession of Woodlands by 1756 and was succeeded at his death before 1782 by his son Edward (fn. 145) (d. 1830); the younger Edward was succeeded by his son Edward Wilbraham of Horsley (d. 1859). (fn. 146) The estate, which comprised 378 a. after the inclosure of 1803, (fn. 147) was sold by the last Edward's trustees in 1861 to two men who were apparently acting for the earl of Eldon. (fn. 148) Woodlands was included in the sale of the earl's estates in 1923 and was bought then by H. H. Stephens who sold the house and farm-land to his tenant C. F. Finch in 1931, retaining the woodland of the estate. (fn. 149) The Finch family still owned and farmed Woodlands in 1978. The farm-house was rebuilt or extensively remodelled in 1854. (fn. 150)

The land at Chedworth given to Bruern Abbey by Roger, earl of Warwick, in the 12th century occupied the end of the north-west peninsula of the parish. It was farmed from the adjoining Marsden Farm in Rendcomb and passed into the Rendcomb Park estate; it comprised 291 a. in 1803. (fn. 151)

William (d. 1184), earl of Warwick, granted land at Chedworth to Roger son of Warin, who had a confirmatory grant c. 1198 from William Turpin by which he was to hold it as 1/5 knight's fee. (fn. 152) It was presumably the estate held at that assessment by Robert de Camera in 1268, (fn. 153) by Richard de Anneford in 1303, and by another Richard de Anneford in 1346. (fn. 154) It has not been found recorded later, unless it was the estate at Chedworth that the Cassey family of Cassey Compton held in the 15th century and the early 16th. (fn. 155)

The rectory of Chedworth was owned by Lire Abbey (fn. 156) until the dispossession of the alien houses in 1414 when it was granted with the abbey's other possessions to Henry V's foundation, Sheen Priory (Surr.). (fn. 157) Sir Edmund Tame and his son Sir Edmund were lessees under Sheen in the early 16th century and the younger Sir Edmund devised the lease to Hugh Westwood. (fn. 158) In 1545 Westwood bought the freehold of the rectory from two speculators, (fn. 159) who had just acquired it from the Crown, (fn. 160) and at his death in 1559 (fn. 161) he devised it for the foundation of a grammar school at Northleach. The new school was not, however, secured in possession of the estate until 1606, partly because of an attempt by Westwood's heir, Robert Westwood, to upset the will. (fn. 162) The rectory estate was worth £80 a year c. 1710. (fn. 163) It comprised glebe land, which after the inclosure of 1803 covered 118 a., (fn. 164) and two-thirds of the tithes, for which the master and usher of the school were awarded a corn-rent-charge of £591 in 1842. (fn. 165)

An estate called Hillwalls, comprising a house and 2 yardlands, was held from Lire Abbey, to which it escheated on the death of a tenant without heirs before 1317. (fn. 166) It then appears to have descended as part of the rectory estate, Hugh Westwood including it in his endowment of the Northleach school. (fn. 167) Another estate, comprising a house and 1 yardland, was forfeited to the Crown after Lire Abbey acquired it without licence. Although for some years in the 15th century placed in the custody of Sheen Priory, (fn. 168) it was retained by the Crown until 1545 when it was sold with the rectory to Hugh Westwood. (fn. 169)

Economic History

In 1066 the demesne of Chedworth manor was worked by 7 teams. (fn. 170) In 1298, when two-thirds of the manor were described, Isabel de Chaworth's portion having been severed from it, the demesne comprised 200 a. of arable, 5 a. of meadow, and rights in a common pasture; (fn. 171) the amount of arable remained unchanged in 1315. (fn. 172) The earl of Lancaster's third of the manor had 100 a. of arable and 6 a. of meadow in demesne in 1327. (fn. 173) By 1490 the demesne land was leased, the farmer also filling the office of reeve of the manor. A sheep-house was then included in the lease and a later farmer, Hugh Westwood, who held the demesne from 1521, (fn. 174) is said to have had a flock of c. 600 sheep at Chedworth. (fn. 175) In 1608 the demesne farm of the manor comprised 5 yardlands in the open fields, 85 a. of pasture and meadow in closes, and pasture rights for 300 sheep and other beasts. (fn. 176)

In 1066 the tenantry on the manor were 16 villani and 3 bordars with 6 teams between them. Before 1086 the sheriff of the county as part of an attempt to increase the value of the manor settled on it an additional 8 villani and 3 bordars with a total of 4 teams. (fn. 177) In 1268 the manor had 8 free tenements and 212/3 yardlands held in villeinage. (fn. 178) In 1298 on the reduced manor estate there were 10 free tenants, 14 yardlanders, who owed 4 days' work a week and cash-rents, and 8 tenants holding 7 a. each, who owed only cash-rents. (fn. 179) By 1315 the works of one of the yardlanders had been wholly commuted and from the others less was apparently required for the works at some seasons, lower values being placed on them. A larger number of lesser tenants, 14 described as cottars holding 2½ yardlands between them, were listed in 1315 and they then owed some bedrepes as well as cash-rents. (fn. 180) In 1327 the tenants on the earl of Lancaster's part of the manor were 11 yardlanders and 18 cottars; all held by cash-rents alone and the tenants were then farming the rents together with the profits of court from the earl. (fn. 181) During the early 14th century the number of tenants in Chedworth declined as a result of the slump in arable farming and the effect on sheep-farming of murrain and the failure of pasture: by 1341 16 tenants in the outlying hamlets of Woodlands and Gothurst had abandoned their holdings. (fn. 182) In 1490 on the manor estate 12 yardland tenements and 12 smaller holdings, most described as a 'hunche' of land, were occupied, but it was evidently not a profitable period for the manor, for the tenants' rents had been considerably reduced in recent years and there were some other tenements for which no tenants could be found. (fn. 183) In 1584 the Leicester college estate, then about to be reunited with the manor, had 12 tenants. (fn. 184)

Seven tenements were alienated from the manor by Thomas Higgs, (fn. 185) who was in financial difficulties, but another 17, ranging in size from ¾ to 2½ yardlands, appear to have remained with the manor when it was sold by Higgs in 1618. (fn. 186) More of the tenant land was probably alienated later, for in the 18th century the number of small freehold farms and cottage-tenements was a major feature of the parish. The number of small freeholds was somewhat reduced at the end of the 18th century by the Ballinger family, which bought 7 holdings and added them to a farm which they already owned, (fn. 187) and at the beginning of the 19th by Joseph Pitt, who bought out another 6 owners. (fn. 188) At inclosure in 1803 there were 110 owners of freehold land in the parish, 80 of them having (after the inclosure had been carried through) under 10 a., 18 having 10–50 a., and 12 having larger estates. The larger estates included the manor, which had over 900 a. of agricultural land, the Woodlands estate, the Rendcomb estate's Marsden land, John Ballinger's 301 a., Joseph Pitt's 199 a., two estates of 215 a. and 167 a. owned by members of the Radway family, and the rectory and vicarage estates. (fn. 189)

The parish had four extensive open fields: Wood field occupied the area between the central valley and the woodland, St. John's field occupied the high ground at the head of the valley, West field (formerly Chittle Grove field) lay between the valley and the Rendcomb boundary, and Old Gore field occupied the whole of the south part of the parish. Another area of open-field arable called the Ridings lay east of Woodlands Farm (fn. 190) and was no doubt formed of assarts made from the woodland before 1329 when open-field land lying east of Marsden field was mentioned. (fn. 191) If the Marsden field recorded then was an open field it seems to have been inclosed at an early date.

An area of common downland, covering 260 a. before inclosure in 1803, lay by the White way between St. John's field and the Ridings. (fn. 192) At least part of the woodland was once also open to rights of common: the 200 a. of wood recorded on the manor in 1315 (fn. 193) was commonable and the tenants may still have had rights in the woods in 1543 when a lease of the demesne required that measures be taken to preserve the young trees against grazing animals. (fn. 194) Later the lords held all the woodland in severalty. The meadow land of the parish was limited to a narrow strip in the central valley and in some small stretches by the Coln on the north boundary.

Consolidation of holdings of open-field land, presumably as a prelude to private inclosures, occurred fairly regularly in the course of the 18th century. (fn. 195) In 1757 Edward Wilbraham exchanged land in Wood field for land in the Ridings near his farm-house at Woodlands (fn. 196) and Charles Ballinger made exchanges to consolidate his open-field land in the early 1790s. (fn. 197) Inclosures from Wood field had begun by 1739 (fn. 198) and by 1803 a considerable area had been taken out of that field near Listercombe and out of St. John's field near St. John's Ashes. The open fields still remained extensive, however, in 1803 when together with the downs they were inclosed by Act of Parliament. Most of the land went to the manor and to the larger estates mentioned above, though not to the Marsden estate which was already all inclosed. Many small owners also received allotments for their few strips of open-field land or for commoning rights, and 12 a. near Chedworth Laines were assigned to the poor in general for furzegathering. In all 56 people received allotments. (fn. 199) Twenty-five of them, three of them fairly substantial owners and the rest cottagers, expressed opposition to the inclosure in a notice in the newspapers. (fn. 200)

After the inclosure some large farms were formed from the main estates. In 1805 John Radway farmed 976 a., including his own land, the Ballinger estate, and a large part of the manor estate; another farm on the manor estate comprised 387 a.; the Woodlands estate formed a single farm of 378 a.; Francis Radway farmed 318 a. of his own and Joseph Pitt's land; and another farm of 275 a. included the two glebe estates. (fn. 201) In 1842 Manor farm with 472 a. was the main farm on the manor estate, which also included Greenhill farm with 242 a. and another with 192 a. The Ballinger estate was then farmed with Longfurlong farm by James Newman, the owner of the latter, making 421 a. in all; Woodlands Farm had 289 a.; and Setts farm with 171 a. and a farm with 126 a., based on a house in Queen Street, were among the other more considerable holdings. (fn. 202) There remained many small freehold farms: in 1831 the parish contained 16 farmers who employed labour and 17 who did not, (fn. 203) and there were over 40 agricultural occupiers in the parish in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, more than half of those returned in 1926 having under 20 a. (fn. 204) By the 1970s much of the land had been absorbed into a few very large farms but some small farms survived, 9 parttime agriculturalists being returned for Chedworth and Yanworth parishes in 1976. (fn. 205)

The usual sheep and corn husbandry of the Cotswolds remained dominant at Chedworth during the 19th century with a five-course rotation of grassseeds for mowing, wheat, turnips, barley and oats, and grass-seeds for grazing by sheep the usual practice. (fn. 206) As many as 8 parishioners were employed full-time as shepherds in 1851. (fn. 207) In 1866 2,729 a. were returned as under cereal crops, roots, and rotated grassland compared with only 358 a. of permanent grass, but by 1896 the decline in profitability of arable farming had reduced the acreage of cereals and roots by about 600 a., much of which was laid down as permanent grassland. That trend continued in the early 20th century (fn. 208) when agriculture in the parish was diversified, particularly by the introduction of dairy and beef cattle; the first large dairy herd was brought into the parish in 1919. (fn. 209) In 1926 the number of cattle returned for the parish was 446 compared with 247 in 1896, while the number of sheep was down to 1,261 compared with 2,185 in 1896. (fn. 210) Dairy-farming remained important in 1976 but sheep-raising had recovered its prominence and at least one of the larger farms was mainly concerned with cereal crops. (fn. 211)

There were three mills on Chedworth manor in 1066 (fn. 212) and there were two on the earl of Warwick's manor in 1298, when one was used as a fulling-mill and held from the lord by all the customary tenants in common. (fn. 213) A mill called Gothurst mill, probably on the Coln in the north-east part of the parish, was granted to Llanthony Priory in 1279 by Miles of Stowell, who reserved life-interests for himself and his wife. Soon afterwards the priory alienated the mill to Thomas of Gothurst at a quit rent of 10s., (fn. 214) which it was still receiving at the Dissolution. (fn. 215) The mill passed to the manor before 1490 (fn. 216) and is last found recorded in 1539. (fn. 217) Another mill stood on the Coln where the road to Stowell crossed out of the parish. It was called Burford's mill in 1803, when it remained part of the manor estate, (fn. 218) but later in the 19th century it was usually called Stowell mill. It was working until the 1930s. (fn. 219) There were possibly other mills in the parish in the 19th century, for two other millers as well as the miller of Stowell mill lived there in 1851; one lived at Gadbridge (fn. 220) which appears to have been where the road crossed the central stream of the parish below Pancakehill, (fn. 221) though no signs of a mill were visible there in 1978.

The name Newport given to a house on Chedworth Downs has prompted the suggestion that an unofficial wayside market was once held near by where the White way meets a number of lesser roads. (fn. 222) It is possible that the right claimed by the lord of the manor in 1490 to levy toll on certain goods within 7 leagues of Chedworth (fn. 223) was connected with such a market and the name Cheap Street may also derive from it, either because that street in the village leads towards the downs or because the market was later moved to the street itself. The surviving records, however, provide no indication, beyond the existence of the fulling-mill in 1298, that Chedworth was anything more than an agricultural village in the Middle Ages; two tailors are the only tradesmen who appear on the incomplete poll-tax assessment of 1381. (fn. 224) It was in more modern times that the village became a minor local centre, providing crafts and other services to the much smaller estate villages which surrounded it. It already had a fairly substantial body of tradesmen in 1608 when 16 were among those listed for militia service, (fn. 225) and the pattern of landholding created by the sale of much of the tenant land of the manor was later a factor in the growth of a large population of tradesmen. Many of the tradesmen in the 18th century owned and farmed small holdings of land. (fn. 226)

The stoneworking trades were particularly strong at Chedworth. Among the numerous masons of the parish the families of Smith, Robins, and Bridges were represented for several generations (fn. 227) and the trade of slater employed at least 10 men from another family, the Wilsons, between 1698 and 1851. (fn. 228) In 1851 the parish had a total of 15 masons and 4 slaters. (fn. 229) Several of the small quarries that were worked on the high ground of the parish also had lime-kilns, (fn. 230) and limeburning supported a few men full-time in the 18th century. (fn. 231) Shoemaking and woodworking were among other village trades well represented in the 18th and 19th centuries and there were also some tradesmen less usual to a village, including a mercer in 1730, two clockmakers later in the 18th century, (fn. 232) a pawnbroker in 1823, (fn. 233) and three landsurveyors, all of the same family, in 1851. (fn. 234) In 1831 54 families were supported by trade compared with 131 supported by agriculture (fn. 235) and in 1851 there were more than 70 inhabitants employed in nonagricultural pursuits. At the latter date 12 carpenters and 8 shoemakers formed the largest groups after the masons, and 3 grocers, 3 butchers, and 3 other shopkeepers indicate that the village also had a role as a minor retailing centre. The woodlands of the Stowell Park estate gave employment to 5 woodmen and 3 gamekeepers in 1851 (fn. 236) and the estate had a foreman of trades in 1885. (fn. 237) The woods provided the material for hurdlemaking which employed several parishioners in the days when the folding of sheep on the arable was an important element in local agriculture. (fn. 238) Some of the traditional village trades, including those of blacksmith, wheelwright, and slater, survived into the middle years of the 20th century at Chedworth, (fn. 239) where more modern business activities were represented by the coal-merchants who traded from Foss Cross station after the opening of the railway (fn. 240) and a bus proprietor who operated from 1928. (fn. 241)

Local Government

In the early 15th century the abbot of Cirencester as lord of the hundred retained frankpledge jurisdiction in Chedworth and all profits from it, though the view was held in Chedworth itself; it met twice a year on an outdoor site, (fn. 242) possibly the road junction on Chedworth Downs which had been the focal point of the parish before the depopulation of its northern hamlets. By 1490, however, the lady of the manor was claiming the right to hold the view together with her manor court. (fn. 243) A court roll of 1505 is the only one known to survive, (fn. 244) though the court leet continued to be held until the First World War, when it met at the Fossebridge inn. (fn. 245)

The surviving records of parish government include churchwardens' accounts from 1645, a vestry order book for 1823–94, (fn. 246) and overseers' accounts for 1762–1835. (fn. 247) The cost of poor-relief rose from under £100 in the mid 1760s, when c. 13 people were on permanent relief, (fn. 248) to sometimes as high as £800 in the second decade of the 19th century when 50–60 people received regular relief. (fn. 249) Its large population gave Chedworth by far the highest figures for poor-relief among surrounding parishes. From the mid 18th century cottages belonging to the parish were being used as poorhouses. (fn. 250) In 1830 some paupers were being employed on roadwork and in 1831 and 1832 families were helped to emigrate to America. (fn. 251) Chedworth became part of the Northleach union in 1836 (fn. 252) and was later in Northleach rural district (fn. 253) until the formation of the new Cotswold district in 1974.

Church

Chedworth church was probably founded before or immediately following the Conquest, for it was presumably William FitzOsbern (d. 1071) who granted it to Lire Abbey, which he founded. (fn. 254) The church was appropriated and a vicarage ordained before 1291, (fn. 255) and the living remained a vicarage. It was united with the livings of Yanworth and Stowell in 1964 (fn. 256) and Coln Rogers and Coln St. Dennis were added to the united benefice in 1975. (fn. 257)

The advowson of the vicarage was retained with the rectory by Lire Abbey (fn. 258) but in the 14th century was usually exercised by the Crown because of the war with France. (fn. 259) It passed to Sheen Priory in 1414 (fn. 260) and was included in the sales of the rectory in 1545. (fn. 261) In 1580, however, Justinian Bracegirdle presented, presumably under a grant for one turn, and the Crown presented at the next vacancy in 1602, though a rival unsuccessful presentation was made then by Corpus Christi College and St. Edmund Hall, Oxford. The advowson had, however, probably been intended as part of Hugh Westwood's endowment of Northleach school, for from 1659 it was exercised by Queen's College, Oxford, (fn. 262) which had been appointed patron of the school in 1606. (fn. 263) In 1978 the college shared the advowson of the united benefice by alternation with the dean and chapter of Gloucester and the Lord Chancellor. (fn. 264)

The portion assigned to the vicar was valued at £5 in 1291 compared with the rectory portion valued at £16 13s. 4d. (fn. 265) The vicar's portion included a third of all the tithes of the parish, for which he received a corn-rent-charge of £296 at commutation in 1842. (fn. 266) In 1623 his glebe comprised a few acres in closes, 2½ yardlands of open-field land, and sheep-pastures, (fn. 267) and after inclosure in 1803 it comprised 110 a. (fn. 268) In the mid 16th century an additional payment of £1 6s. 8d. was made to the vicar out of the rectory estate (fn. 269) and it was still being made in 1807, though at some time previously a Chancery decree had been needed to enforce it. (fn. 270) The vicarage house, on the north-east side of Cheap Street, was described as a convenient mansion in 1623; (fn. 271) it was rebuilt by the vicar James Rawes c. 1770 (fn. 272) and was extended by a lower range to the north-west in the early 19th century. It was sold c. 1976 and another house near by in Cheap Street was acquired as the vicarage. (fn. 273) The living was valued at £7 8s. 2d. in 1535, (fn. 274) £50 in 1650, (fn. 275) £70 in 1750, (fn. 276) £276 in 1813, (fn. 277) and £302 in 1863. (fn. 278)

Sixteenth-century vicars of Chedworth included, from 1527, Gilbert Jobburne, (fn. 279) who was found only partly satisfactory in theological knowledge in 1551, (fn. 280) and Richard Woodward (d. 1580), probably a former monk of Hailes Abbey, (fn. 281) who was said in 1576 to preach only once or twice a year and read the commination only once a year. (fn. 282) Edmund Bracegirdle, vicar 1580–1602, was challenged in his tenure of the living in 1599 on the grounds that he also held the rectories of Stowell and Hampnett. He was succeeded by Nathaniel Aldworth (fn. 283) who held the living until at least 1642. (fn. 284) Robert Sawyer, described as a preaching minister, held it in 1650, (fn. 285) and in 1659 John Cudworth was instituted, remaining vicar after the Restoration. (fn. 286) Geoffrey Wall served a long incumbency from 1682 until his death in 1743. (fn. 287) He and his successors in the 18th century appear to have been resident until the time of Benjamin Grisdale, vicar 1785–1828, (fn. 288) who was living at Tooting (Surr.) in 1789. (fn. 289) Arthur Gibson, vicar 1828–78, served a curacy at Norwood (Surr.) in the early years of his incumbency. (fn. 290)

The church of ST. ANDREW, which bore that dedication by 1425, (fn. 291) is built of rubble and ashlar and has a chancel with north vestry, a nave with north aisle and south porch, and a west tower. By the mid 12th century there was apparently a substantial church on the site, from which only part of the nave walling survives. The lower stage of the tower and a north aisle were added in the late 12th century, the three-bay north arcade formed by cutting through the existing nave wall. The chancel arch was enlarged and the chancel extended or rebuilt early in the 13th century and at the same period the upper stage of the tower and the porch were added. Except for a 14th-century window in the chancel there appears to have been little work done later until the mid 15th century when the south wall of the nave was rebuilt with five large windows; (fn. 292) one of the buttresses bears an inscription to Richard Sly (d. 1461), perhaps the benefactor responsible for the work, and the rood-stair turret at the end of the wall bears the date 1485. Other work done in the 15th century included the tower parapet, a new window in the chancel, and the renewal of the doorway to the porch. In 1883 under Waller & Son the north aisle was rebuilt, the vestry added, and the church restored and reseated. (fn. 293)

The church has a Norman tub-shaped font (fn. 294) and a 15th-century carved stone pulpit. The early-17th-century lectern was a gift to the church in 1927. (fn. 295) There are some fragments of early painted glass in a chancel window. (fn. 296) There are five bells cast by Abraham Rudhall, four in 1717 and the other in 1719; a sixth was added by John Rudhall in 1831. (fn. 297) The plate includes a chalice and paten-cover of 1684. (fn. 298) The parish registers survive from 1653. (fn. 299)

Nonconformity

The Congregational interest at Chedworth, which with its large body of independent craftsmen was favourable to the establishment of nonconformity, is said to have been founded as a result of the preaching of George Whitefield there. (fn. 300) Congregationalists presumably formed the group led by a minister, Joseph Humphreys, who registered his house for worship in 1743. About 1750 the Congregationalists built a chapel at Pancakehill (then called Limekiln hill) at the south-east end of the village, (fn. 301) and the chapel was rebuilt in 1804, when the group was styled Independent. In 1851 the average congregations at morning, afternoon, and evening services were 130, 206, and 80 respectively, (fn. 302) and another congregation of c. 70 under the same minister used a building in the upper part of the village, opened in 1847. (fn. 303) The chapel ceased to have a resident minister in 1950, and in 1957 it was amalgamated with the chapel at Dyer Street in Cirencester. (fn. 304)

A Primitive Methodist chapel was built in Cheap Street in 1861 and was in use until the early 1940s. (fn. 305) In 1949 it was acquired by the Chedworth silver band as a practice-room. (fn. 306)

Education

In the earlier 19th century dame schools, of which there were three in 1818 teaching a total of 36 children, provided the only weekday education at Chedworth. A church Sunday school was attended by 130 children in 1818 and by 1833 there was also a Sunday school attached to the Independent chapel. (fn. 307) The church Sunday school, held in a building near the church, (fn. 308) was affiliated to the National Society by 1847. (fn. 309) A National dayschool was started before 1863 (fn. 310) and in 1873 moved into a new building west of Cheap Street. (fn. 311) The average attendance was 90 in 1885 (fn. 312) and 110 in 1910 but fell to 53 by 1932. (fn. 313) In 1978 the number on the roll was 46. (fn. 314)

Charities for the Poor

Land given, it was said, in Richard II's reign for the repair of the church and relief of the poor was alleged in 1601 to have been appropriated by the trustees to their own use when a Chancery decree was obtained placing the land under the management of the churchwardens. (fn. 315) The land was later let on 99-year leases with the result that in 1743 it brought in a rent of only 54s. though said to be worth £10 a year; there was also, however, a rent of £3 received from the parish for cottages built on part of the land and then used as poorhouses. (fn. 316) The land, which after the inclosure comprised 21 a., brought in a rent of £27 in the mid 1820s when all of it was apparently being applied to the church. (fn. 317) The income of the charity was about the same in 1896 when a Scheme divided the profits equally into separate charities for the church and the poor. (fn. 318) In 1978 the poor's part of the charity was distributed in cash at Christmas. (fn. 319)

Hugh Westwood (d. 1559) charged his rectory estate with 13s. 4d. a year for the poor. (fn. 320) The sum was being distributed by the tenant of the rectory land to poor widows in the 1820s (fn. 321) and later in the 19th century was received from the governors of Northleach grammar school and distributed by the vicar. (fn. 322) Charles Ballinger of Chalford (d. 1798), who owned an estate in the parish, (fn. 323) gave a third of the proceeds of two shares in the Stroudwater canal to buy cloth for the poor of Chedworth. About £14 a year was received from that source in 1827 (fn. 324) but the profits fell to £3 by 1896 (fn. 325) and by 1930 no dividends were produced by the shares. (fn. 326)