A History of the County of Gloucester: Volume 12. Originally published by Boydell & Brewer for Victoria County History, Woodbridge, 2010.

This free content was digitised by double rekeying. All rights reserved.

'Newent - Economic History', in A History of the County of Gloucester: Volume 12, ed. A.R.J. Jurica (Woodbridge, 2010), British History Online https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/vch/glos/vol12/55-69 [accessed 19 April 2025].

'Newent - Economic History', in A History of the County of Gloucester: Volume 12. Edited by A.R.J. Jurica (Woodbridge, 2010), British History Online, accessed April 19, 2025, https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/vch/glos/vol12/55-69.

"Newent - Economic History". A History of the County of Gloucester: Volume 12. Ed. A.R.J. Jurica (Woodbridge, 2010), British History Online. Web. 19 April 2025. https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/vch/glos/vol12/55-69.

In this section

ECONOMIC HISTORY

The small town of Newent was created in a predominantly agricultural area and hosted a succession of crafts and industries drawing on the natural resources of the countryside. Although the development of a coalfield near by foundered in the 19th century and Newent was drawn ever more into the economic orbit of Gloucester, the town continued to supply goods and services to its residents and to those of surrounding communities.

AGRICULTURE

To the Mid Seventeenth Century

In 1086 there were two slaves on the demesne land of Cormeilles abbey's Newent manor and it was worked by three ploughteams. The tenants were 9 villans and 9 bordars with 12 ploughteams, and a reeve held another part of the estate comprising 1½ villan holdings and 5 bordars. In addition all the tenants of the manor worked jointly another 5 ploughteams. Durand of Gloucester's estate, the later Boulsdon manor, had 2 slaves and 1 team in demesne and a tenantry of 5 bordars with 2 teams. (fn. 1) On Carswalls manor there was 1 team in demesne and the tenants were 3 villans and 1 bordar with two teams. (fn. 2) The large number of ploughteams listed (26) shows that the parish was extensively cultivated but appears disproportionate to the number of individual tenant holdings (33½ in all). Presumably the holdings were large and employed considerable numbers of dependent labourers: in the early 14th century the yardland on Newent manor, possibly the equivalent of the 11th-century villan holding, comprised 72 a. (fn. 3) The existence in 1086 of a manorial reeve with his own group of tenants, and presumably greater administrative responsibility than was usual, probably arose from the ownership of the manor by a religious house in Normandy. Cormeilles later established a cell at Newent with a prior who acted ex officio as bailiff of its manor. The need for regular communication between Newent and the mother house probably led to the creation of four sub-manors (Stalling and three at Okle) which were held from the abbey by riding service. (fn. 4)

Newent manor demesne In 1291 the abbey's demesne, cultivated by Newent priory, was extended at six ploughlands. (fn. 5) Much of its arable formed a tract southeast of Newent town, including fields called Upper and Lower Berry field (80 a. in 1624), Crockwardines, and Nelfield. North of the town and priory precinct were pasture closes, orchards, and a small park, and beyond was meadowland bordering Ell brook. The demesne also included a meadow called Lydenford, presumably by Ell brook upstream of the crossing of that name on the boundary with Upleadon and Highleadon, and parcels in a large common meadow called Cowmeadow adjoining Tibberton and Taynton. There was also demesne adjoining Kent's green (fn. 6) and it was probably to aid the cultivation of the abbey's lands in the south-east of the parish that a farmstead known as the Grange was established on the lane to the green. (fn. 7)

During the 13th century the demesne was intensively cultivated for the priory and opportunities to enlarge its holdings in the parish were taken. Most of the acquisitions were by purchase or lease rather than by gift in free alms. (fn. 8) The meadowland evidently proved insufficient for the numbers of livestock on the demesne farm. Between 1278 and 1296 the priory took leases of parcels in Cowmeadow and elsewhere, usually for terms of six years, from 19 or more of its tenants and freeholders. (fn. 9) Ploughing and harvest work on the demesne was done mainly by the labour services of the customary tenants, (fn. 10) but the priory servants included a cowherd in 1298 (fn. 11) and a shepherd in 1310. (fn. 12) In the early 15th century, under John Cheyne and later Fotheringhay college, parcels of demesne land and some of the farm buildings at the priory precinct were leased out. (fn. 13) Probably from that time the lords gave up all demesne farming, as they certainly had by 1482. (fn. 14) In 1539 the demesne land was held by 11 separate tenants, (fn. 15) and by 1624 it was divided among 18 tenants. (fn. 16)

Holdings and services In the 13th and 14th centuries the parish supported a multitude of small agricultural holdings. About 1315 on the Newent manor estate, including only those for whom a dwelling is mentioned, there were 87 tenants, 36 of them holding freely and 51 by customary tenure; many other holdings comprising just land were listed, often it seems occupied by inhabitants of the town. The customary tenants with dwellings mostly held half or quarter yardlands (36 or 18 a.) and included 18 living in Compton tithing, 14 in Cugley, 13 in Malswick, and 6 in the parts of Newent tithing adjoining the town. (fn. 17) In 1307 Bevis de Knovill's Kilcot manor had eight free tenants and five neifs (four of them holding 30 a. each and one with 6 a.). (fn. 18) For the other six manors recorded in the parish no comparative evidence has been found for the period, but in the late 16th century and the mid 17th (by which time numbers of holdings had probably been reduced) Okle Clifford and Okle Grandison respectively had eight and six resident tenants. (fn. 19) From what is known about the chief manor and Kilcot, and can be surmised about the others (which included the substantial Boulsdon manor), it might be assumed that in the years before the Black Death 150 or more small farmers inhabited and cultivated the rural parts of Newent parish.

On Newent manor many of the services owed by the customary tenants had been commuted permanently for fixed cash rents by the beginning of the 14th century. Among the few still liable to the full quota of works were four quarter-yardlanders in Compton, who might be required to work every fourth week for five days (their duties including ploughing and harrowing 13 a.) and perform 16 bedrips; their whole obligation, if commuted at the will of the abbot, was worth 10s. a year. (fn. 20) Most of the other holdings then owed ploughing service on a few acres, together with some haymaking and carrying duties at the hay harvest. Other obligations owed by certain tenants included guarding the lord's swine at pasture, carrying salt to the manor, providing labour for the repair of the mill dyke at Malswick, contributing to a payment for millstones, and brewing ale when the abbot of Cormeilles visited the manor. (fn. 21) Many of the inhabitants of Newent town, though otherwise free of labour services, were liable to provide a worker, armed with a pitchfork or rake, for the hay harvest in Lydenford or other demesne meadows. (fn. 22) Resistance to the labour services is recorded in the mid 1280s when six men were presented in the manor court for sending insufficient men to work in the hay harvest, another for sending his wife, and another for withdrawing his service altogether. (fn. 23) In 1365 20 tenants were absent from the haymaking and in 1368 a large number failed to appear at the corn harvest. (fn. 24) Some ploughing, harrowing, harvest, and carrying works were still being used in 1390, (fn. 25) but the remaining obligations presumably lapsed or were commuted with the leasing out of the demesne in the 15th century. By 1482 the value of commuted works was subsumed in the sum for tenant rents in the bailiff's annual account. (fn. 26) On the Kilcot manor of Bevis de Knovill in 1307 only one of the five customars still owed labour service, the others paying cash rents. (fn. 27)

From the mid 14th century the decay and abandonment as separate units of many tenant holdings on Newent manor and a general shortage of tenants becomes clear. In 1354 two half-yardland customary tenements in Cugley were leased to a single tenant for a term of six years; (fn. 28) in 1369 two decayed houses were ordered to be taken into the lord's hands; (fn. 29) and in 1397 a tenant died in possession of a holding which included the land once attached to five houses but possessed no cattle or sheep to provide a heriot. (fn. 30) In 1401 another of the Cugley customary tenements was waste, and a lease was granted of the sites of two former houses in Compton. (fn. 31) In 1482 many holdings were on lease at a reduced rent, seven of them including the sites of demolished houses (tofts). (fn. 32) By 1539 the number of free and customary tenancies on Newent manor which had houses had been reduced to 46, (fn. 33) and c.1607 the equivalent number, increased by a few new cottage tenements, was 58. (fn. 34) In 1624 customary tenements (copyholds) with houses attached numbered only 6 in Cugley tithing, 5 in Malswick, and 4 in Compton, but, as a result of the amalgamation of holdings, they included good-sized farms: in Malswick one farm, apparently that later called Rymes Place, had 92 a., Hogsend farm had 51 a., and Horsman's farm had 48 a.; in Cugley a farm based on a house at or near the site of Little Cugley had 86 a. and Ploddy House farm had 77 a.; and in Compton two farms based on houses near Compton green had 56 a. and 43 a. respectively. Various other copyholds, mostly small, comprised lands only, though some, including two of the old customary tenements in Newent tithing, had ruined houses or tofts. Some parts of the former demesne were also tenanted as copyhold in the early 17th century, including the land adjoining Kent's Green. (fn. 35) Most of the copyholds were later enfranchised, apparently by the Winter family in the 1650s. By the late 18th century only three or four of those recorded in 1624 still belonged to the manor. (fn. 36)

Among the other manors of the parish, Okle Clifford in the late 16th century had eight tenants with houses and land (six free and two customary) as well as a larger number of tenancies comprising land only. (fn. 37) Okle Grandison in 1659 had six tenants (freehold, leasehold, or copyhold) with houses and land. (fn. 38)

Fields and closes Most of the cultivated land of the parish was in closes from antiquity, but there were a few small open fields, the principal ones lying west of Newent town, bordered on the south-east by Watery Lane. In the northern part of that area was Worsden field, where the strips were apparently held originally by townspeople or inhabitants of the outlying parts of Newent tithing; in the south-western part, separated from Worsden field by Bradford's Lane, Boulsdon field was probably reserved to inhabitants of Boulsdon tithing. (fn. 39) In the Middle Ages Newent tithing also included an open field called Cleeve field, on the east side of the town in the angle of the Gloucester road and the lane to Cleeve Mill, (fn. 40) and Boulsdon tithing contained at least one other, Mill field, straddling the Boulsdon brook to the east of Great Boulsdon farm. (fn. 41) A field called Withycroft near Stardens farm was recorded in the late 12th century (fn. 42) and still had uninclosed strips in the mid 17th. (fn. 43) In Compton tithing in the early 17th century some tenants held strips in fields called Newlands and Stonylands near Compton green, (fn. 44) and in Kilcot strips remained in a field called Mouse field, lying in the area between the Ross road and Wyatt's farm. (fn. 45)

In the early 14th century the demesne arable of Newent manor was cropped on a conventional threecourse rotation. On parts the courses were wheat, oats, and a fallow, (fn. 46) but large quantities of rye were grown on other parts in 1347, and in Newent generally rye was for long the main cereal crop. (fn. 47) The diverse nature of the soil, some parts clay and some parts sand, led to many closes being distinguished by names such as Wheat field or Rye field. (fn. 48) Fruit growing, mainly for the production of cider and perry, was widespread by the late 16th century when leases of former demesne land usually included a provision for planting apple and pear stocks. (fn. 49)

Commons The strips and common rights in Cowmeadow, on the south boundary, were held by occupiers from all parts of the parish in the late 13th century and later. (fn. 50) Common pasture rights in the woodlands on the slopes of May hill were apparently restricted to freeholders of Newent manor in the early 17th century; in 1632 the commoners secured an agreement with the lord of the manor, Sir John Winter, to protect their claims, which, however, lapsed later that century. (fn. 51) Gorsley common straddling the northwestern boundary of the parish was described in 1624 as fit for pasturing horses and young cattle and sometimes sheep. The tenants of Newent manor, the Kilcot manor based on the Conigree, and Oxenhall, Linton, and Aston Ingham manors all intercommoned there, but the boundaries of the parts belonging to the respective manors were defined and the commoners kept their cattle as much as possible within their own areas. (fn. 52) Among the smaller commons of the parish, Okle green was being overburdened with stock in 1424, (fn. 53) and on Brand green, Pool hill, and Botloe's green, on the boundary with Pauntley, the animals of Newent and Pauntley tenants grazed together without stint in 1619. (fn. 54)

From c.1650 to c.1850

The pattern of landholding in Newent became more complex by the dismemberment of Boulsdon manor and other parts of the Porter family's estate in the early 17th century and the sale of much demesne and tenant land on Newent manor during the Commonwealth period. (fn. 55) Holdings ranged later from temporary groupings of closes rented by Newent butchers (fn. 56) to substantial ring-fenced farms based on ancient manorial sites such as Okle Clifford and Carswalls. The engrossment of farms continued, with the Foleys leading the way after their purchase of the manor by buying a number of free holdings in the south of Cugley tithing in the 1660s to form Black House farm (87 a. in 1775). (fn. 57) The Hartland family formed Green farm near by (131 a. in 1817) by a similar process in the early 18th century, and in Boulsdon tithing Briery Hill farm's 89 a. was made up of four former tenancies in 1802. (fn. 58) Those acreages were typical of the main farms of Newent parish at the turn of the 18th century; Carswalls farm, with 286 a. in 1808, was an unusual size. (fn. 59)

Land use and agricultural improvement During the early modern period farming shared the strong pastoral basis of much of the surrounding region: dairying for cheese making, the raising of cattle and the Ryeland breed of sheep, and the cultivation of cider orchards were the most significant enterprises. (fn. 60) As elsewhere in west Gloucestershire and Herefordshire, the repeal of the cider tax in 1766 was marked by lavish celebrations, including a public dinner in the market place, a sheeproast, bonfires, and a ball. (fn. 61) Almost every farm in the parish made cider and some came to specialize in its production. In 1818 Great Boulsdon farm had c.50 a. of its 139 a. given over to orcharding, (fn. 62) and in 1826 on Caerwents farm 44 a. out of 70 a. was planted with apple and pear trees, said to be capable of producing over 200 hogsheads of cider and perry in a good year. (fn. 63) J.N. Morse, a leading landowner in Newent from the 1780s, (fn. 64) dealt in cider as well as in apple and pear stocks, raised in nurseries on his estate. (fn. 65) Some houses in Newent town had cider-making equipment, (fn. 66) and some of its tradesmen, including the mercer and chandler William Nelme (d. 1702), dealt in cider as a sideline. (fn. 67) Cattle raising had long been an important feature of local farming, reflected in the strength of the butchering trade in the town, (fn. 68) and 15 of Newent's farmers were styled graziers in a trade directory of the early 1790s. (fn. 69)

Improvements in arable farming were hampered by a general reluctance to try new techniques. By the late 18th century, however, manuring and liming of some areas of sandy soil had made them more suitable for growing wheat, and turnips and clover were being introduced to the rotation. A spirit of improvement was also evident in livestock farming, with Ryeland ewes being cross-bred with Dorset and Shropshire rams. (fn. 70) In 1801, when c.2,400 a. of land in Newent was returned as under crops, wheat accounted for 1,238 a. and rye for only 60 a.; barley (572 a.), peas, beans, and oats accounted for most of the remainder and there was 147 a. of turnips. (fn. 71) Inclosure of the remaining open-field land proceeded slowly during the period. Two closes called New Tynings taken out of Worsden field were mentioned in 1705 (fn. 72) and a 13-a. inclosure from Mill field in 1719. (fn. 73) Much of Boulsdon field remained in strips to the mid or later 19th century. (fn. 74) The principal tract of common, at Gorsley, was described in the early 1790s by a writer on agriculture as suitable for raising corn and for orcharding but 'in its present state nearly useless'. (fn. 75) In 1806 some freeholders tried to promote an inclosure of the part of the common lying within Newent, including in their plans the more recent encroachments made by cottagers. The lords of the two manors with rights there, Andrew Foley and J.N. Morse, and their agents were reluctant, however, having regard both for the welfare of the cottagers and the difficulties involved in ejecting them. (fn. 76) Later some Newent landowners, influenced by the contemporary movement to provide allotments as a support for the poor, divided and rented out parts of their estates as small gardens. By 1836 there were some on John Hartland's estate south of the town, adjoining the continuation of Bury Bar Lane, and others on land west of Watery Lane belonging to Benjamin Hooke's Common Fields farm and to another owner. Those allotments were presumably occupied mainly by inhabitants of Newent town. (fn. 77)

The Late Nineteenth Century and the Twentieth

In 1851 Newent parish had 48 farms (using 20 a. as a minimum size for that description). The typical size remained around 80 to 130 a., worked by the family and two or three labourers. The main exceptions were based in Compton tithing, where the Pauntley Court estate's Compton House farm had 500 a., about half of it in Pauntley parish, and employed 20 labourers, Carswalls farm had 320 a. and 18 labourers, Scarr farm had 290 a. and 11 labourers, and Hayes farm had 280 a. and 16 labourers. Okle Clifford farm, with 300 a. and 10 labourers, was the only other farm of similar size. (fn. 78) Also by the mid 19th century there was a proliferation of holdings comprising only a cottage, orchard, and a few acres taken from the waste; most were on Gorsley common and others were on Clifford's Mesne. Some cottagers followed a trade or craft to supplement their income but, as encroachment diminished the area of waste available to pasture animals, others probably worked at least part-time for the larger farms. In 1896 a total of 95 agricultural holdings was returned (fn. 79) and in 1926 114 including 43 of under 20 a. (fn. 80)

Land use Arable predominated in the mid 19th century. In 1866 (when the total acreages suggest that some farms failed to make a return) 3,263 a. was returned as under crops and 1,927 as permanent grassland. Wheat, roots, and grass seeds were then the main constituents of the rotation; the amount of rye grown was then only 33 a. and dwindled to a few acres by end of the century. The slump in cereal prices produced the usual reversal in the proportion of arable to pasture and meadow. In 1896 2,842 a. of land was returned under crops as against 4,060 a. permanent grass, and the number of livestock showed a considerable increase, with 1,154 cattle and 3,399 sheep and lambs compared to 835 and 2,618 in 1866. (fn. 81) Scarr farm was unusual as still being an arable enterprise, with all but 25 of its 347 a. under the plough, cropped mainly with barley and roots. When offered for sale in 1900 it was reported to be well farmed but nevertheless losing money: the previous owner had spent £30,000 in purchasing it and putting up new buildings but the farm was expected to realize no more than £10,000. (fn. 82) The 64-a. Ravenhill farm, which was over two thirds arable in 1869 (fn. 83) and a noted supplier of seed-wheat at that period, was all farmed as pasture or orchard by 1916. (fn. 84) Some owners, including those of Ford House, Great Cugley, and Great Boulsdon, took their farms in hand in the 1880s and 1890s and managed them through bailiffs. (fn. 85)

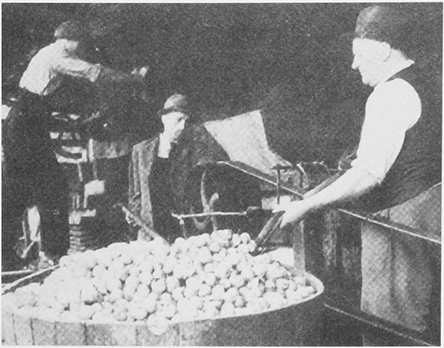

18. Cider making on the premises of Andrew Ford in 1951

Between the wars even more land was converted to pasture, and there was a further increase in livestock, with 1,608 cattle returned in 1926, including a large contingent of dairy cows. (fn. 86) Dairying benefited at that period from Newent's rail links to Gloucester, Ledbury, and Hereford, and c.1921 Cadbury Ltd, the chocolate makers, established a milk collection depot near Newent station. (fn. 87) In 1928 over half of the arable on Okle Clifford farm had recently been laid down to grass and landlord and tenant agreed to share the cost of providing a water supply for dairy farming. (fn. 88) In 1932 on the 103-a. Black House farm only 2 a. was ploughed, (fn. 89) and in the following year Callowhill farm's 143 a. included only c.22 a. under the plough. (fn. 90) In 1926 the crops returned for the parish included 99 a. of sugar beet, which remained an important cash crop for some farms to the end of the century. (fn. 91) An unusual feature of farming in the early 20th century was the survival of Cowmeadow as a common meadow comprising in 1903 40 plots divided among c.9 farmers. In 1908 the Gloucester estate agent and auctioneer Henry Bruton, having become one of the principal owners by his purchase of the adjoining Moat farm, began an annually renewable exchange of plots with the owner of Layne's farm to give each a compact holding. (fn. 92) Similar temporary arrangements, apparently involving all the owners of strips in the meadow, continued in 1921. (fn. 93)

Almost every farm had a cider mill and press in the late 19th century and early 20th. They were also to be found on many of the cottage holdings in the western arm of the parish, (fn. 94) where about half of the former Gorsley common was under orchard in the 1880s. (fn. 95) The Kilcot inn was among premises making cider in that area to the mid 20th century. (fn. 96) In 1896 366 a. of land in Newent parish was returned as orchard. (fn. 97) The firm of Henry Thompson & Co., based at Southends farm, won many prizes for its draught and bottled cider and perry; when it failed in 1911, a collapse attributed to financial mismanagement, the trade was said to be thriving in the area. (fn. 98)

19. Packing market-garden produce at the Scarr in 1951

Market gardening and poultry farming In the 20th century there was a growth in market gardening, particularly the growing of soft fruit in upland parts of the parish. About 30 a. was returned as devoted to that sort of agriculture in 1896, (fn. 99) and there were several specialist market gardens in the parish in 1937 (fn. 100) when the Land Settlement Association bought Scarr farm for one of its schemes for settling unemployed people on the land. The Association divided the 360-a. farm into 57 smallholdings of between 3 and 8 a., each with a small dwelling, piggery, glasshouse, and poultry house. The scheme was run on the co-operative system under a committee and estate manager; supplies and equipment were provided from a pool and packing and marketing of produce were done centrally. (fn. 101) During the Second World War the criteria for granting tenancies were changed to benefit any man of non-military age, and after the war new tenants were required to have experience in horticulture. In the 1950s and 1960s, while the manager ran part of the land as a nursery, the tenants, of whom there were 49 in 1961, produced vegetables, soft fruit, and chrysanthemums. (fn. 102) In 1969 the packing station employed 40 people and each tenant two or three parttime workers in the busy months. A programme of improvements then under way included the replacement of the glasshouses to provide each holding with 1 a. under glass. (fn. 103) In the later 20th century poultry farming, in which some farmers specialized by the early 1930s, (fn. 104) expanded with the establishment of large egg and rearing units. The principal firms were Stallard Bros., which in the early 1960s built a complex of sheds for battery chickens south-west of Compton Green, (fn. 105) and a business run by the Freeman family of Town Farm, which in 1983 employed c.60 people in rearing and processing ovenready chickens. (fn. 106)

Farming in the later 20th century In the mid and later 20th century the proportion of arable in the parish showed a modest rise and livestock farming retained its strength, with 2,124 cattle, mainly in dairy herds, and 4,711 sheep and lambs returned in 1986. In 1956 1,815 a. was returned as growing general crops and 356 a. growing vegetables, glasshouse crops, and soft fruit, while 3,890 a. was returned as permanent grassland and 277 a. as orchard. In 1986 the equivalent figures were 755 ha (1,865 a.), 170.3 ha (421 a.) including 15.7 ha (39 a.) under glass, 1,146 ha (2,833 a.), and 48.3 ha (119 a.). The 1,777 pigs returned in 1956 (compared with 683 in 1926) were mainly accounted for by the piggeries on the Land Settlement Association estate. That estate also contributed to the large numbers of poultry then kept, but the later increase in the number of chickens returned, over 43,000 birds in 1986 compared with c. 25,000 in 1956, was mainly accounted for by the two large businesses mentioned above. (fn. 107) In the early 1980s, following the winding up of the Land Settlement Association, its holdings were sold, many to the tenants. Most were formed into larger units, which continued to grow soft fruit and market garden produce. (fn. 108) In 1986 a total of 42 full-time farming units was returned in Newent parish: 8 were described as dairy farms, 6 as mainly devoted to cattle and sheep raising, 5 to pigs or poultry, and the others to general cropping or fruit and vegetable growing; 92 other units worked on a part-time basis were mainly small market gardens or fruit farms. The latter gave the parish an unusually high proportion of people still employed full- or part-time in agriculture, a total of 389 in 1986. (fn. 109)

20. The Three Choirs Vineyard

The main features in farming at the end of the 20th century and the beginning of the 21st included a reduction in dairying and other general trends in agriculture such as the amalgamation of farms into larger units and the sale of farmhouses, often with a field or two attached, to non-farming owners. In 2007 the larger farms were mainly engaged in cattle and sheep raising, but fruit growing and market gardening remained the principal enterprises in the north part of the parish, where much produce was then grown under 'Spanish polytunnels', many of the glasshouses having gone out of use. A successful new enterprise was a vineyard called the Three Choirs, which began in 1972 with the planting of a vines on a fruit farm at Welsh House Lane in Pauntley (fn. 110) and was later based on the farmhouse formerly called Baldwin's, just within Newent's northern boundary. (fn. 111) By 2007 its vines covered 75 a. in Newent and Pauntley and the buildings comprised a winery, which also processed grapes for other English vineyards, a 'real ale' brewery begun in 2002, a restaurant, and a small hotel. (fn. 112)

WOODLAND MANAGEMENT AND WOODLAND CRAFTS

Yartleton woods on the northern slopes of May hill were an important asset of Newent manor, but during the 13th century and the early 14th the benefit the lords could derive from them was restricted because the south-western part of Newent was within the Forest of Dean and subject to forest law. During the 13th century the Forest's north-eastern boundary followed the Gloucester–Newent road through Malswick tithing and passed along the main street of the town to Ell bridge. For most of the remainder of its course within the parish it ascended Ell brook to Gorsley ford, 700 m north of the boundary with Aston Ingham (Herefs.), but whereas according to a perambulation of 1282 it followed a road from Ell bridge to rejoin the brook at Oxenhall bridge, south of Oxenhall church, according to another of 1300 it followed the brook all the way from Ell bridge to Gorsley ford. The perambulations also appear to disagree whether its course south of the ford into Aston Ingham continued on the brook or by a nearby lane. The south-western part of Newent was finally confirmed as being outside the Forest in 1327. (fn. 113)

In the 13th century Newent priory was several times presented at Forest eyres for committing waste in its woods (fn. 114) and in 1308 and the early 1320s it sought the intervention of the Crown and the justices of the forests when its claim to take estovers without supervision by Dean's foresters was challenged. (fn. 115) The use of other woods on the west side of the parish, belonging to Boulsdon and Kilcot manors, was similarly restricted before 1327, though the owners were permitted to appoint their own woodwards subject to approval by the justices-in-eyre. (fn. 116) Lands called Great and Little Woodwards in Compton tithing, held by a free tenant of Newent manor c.1315, may have been charged with the service of acting as a manorial woodward (fn. 117) but possibly only within Compton, which lay outside the Forest's bounds.

Charcoal Production

In the early modern period much of Newent's woodland was managed as coppice to provide charcoal for the iron industry. That was no doubt the case with Yartleton woods by 1448 when Fotheringhay college leased them to a Mitcheldean man, reserving the standards and large timber trees. (fn. 118) Charcoal burning was a significant source of livelihood in Newent in 1608 when seven colliers were recorded in the parish. Five lived in Compton, (fn. 119) presumably operating in the small woods and groves of that tithing: fields called Coalpits and Coalpit Piece in the south part of Carswalls farm and others called Colliers Leaze and Pit field to the west of Madam's wood (fn. 120) probably got their names from charcoal burning.

Sir John Winter, lord of Newent manor, was supplying his Forest of Dean ironworks from Yartleton woods in 1632. By agreement with leading freeholders he was to enclose certain coppices for a period of six years before felling, and during the following six years the commoners were to exercise their rights, an arrangement presumably intended to rotate among various parts of the woods. To protect the woods against encroachment, it was agreed that cottages there without good title were to be demolished and no more built except those necessary to house workmen cutting and charcoaling the coppices. (fn. 121) In 1660, when Thomas Foley, the new owner of the manor, was using the woods to supply his Ellbridge furnace, 417 of their 595 acres were described as coppice. By arrangement with fellow landowners, Foley also managed other coppices in Newent, including 30 a. of Kilcot wood on Kilcot manor and 35 a. in Boulsdon belonging to the owner of Ravenshill farm. (fn. 122) Under the Foleys the commoners came under increasing pressure to abandon their rights at Yartleton. The Cugley freeholders led by one of the Woodward family resisted and Paul Foley is said to have secured their acquiescence by paying off Woodward and reducing the chief rents owed to the manor by the others. (fn. 123) During the late 17th century and the early 18th the Foleys cut and corded the Yartleton coppices on a 14-year cycle. (fn. 124) In the 1680s at least seven Newent parishioners worked as charcoal burners and others followed the trade of 'corder', cutting and stacking the coppice wood. (fn. 125) During the second half of the 19th century, under the Onslow family, annual sales of timber and coppice wood in Yartleton woods were held by the Gloucester auctioneers Bruton & Knowles. (fn. 126) About 1911, at the sale of the Onslows' estate, the woods were bought by C.P. Ackers, (fn. 127) heir to the Huntley Manor estate, and from that time they were managed with adjoining woodland in Huntley and Taynton, most of the oak coppice being replaced by conifers for commercial timber production. (fn. 128)

Other Woodland Crafts

The woods, by supplying oak bark, contributed to the tanning industry of the town and parish and, by supplying material for hoops and staves, to the manufacture of barrels for local cider production: seven or more coopers were working in Newent during the 1680s. (fn. 129) Other crafts connected with the woodlands were lath and broom making, carried on by a number of cottagers at Clifford's Mesne during the early 19th century. In 1851 four inhabitants of the hamlet were employed as wood cutters. (fn. 130) Brand Green had a lath maker in 1820. In the same period wood cutting and charcoal burning employed cottagers of the Gorsley and Kilcot area, possibly working in the adjoining Oxenhall woods, (fn. 131) and in 1851 two Gorsley men made hurdles for sheep pens. (fn. 132) Several timber merchants operating in the parish in the late 18th century and the early 19th (fn. 133) presumably traded in timber from the local woodlands. A Monmouth timber merchant and ship builder, Hezekiah Swift, contracted to buy Kilcot wood and woodland in Boulsdon, though the sale was concluded in 1818 with the owner of the Pauntley Court estate. (fn. 134) There were timber yards on the canal, north of Newent town, by 1841, (fn. 135) and Herbert Lancaster established a saw mill and timber yard beside the railway in Horsefair Lane shortly before 1900. (fn. 136) Lancaster's firm, one of the main employers in the parish during the early 20th century, continued there until c.1970, (fn. 137) when a firm making fencing and ladders took over the site. (fn. 138)

COAL MINING, QUARRYING, AND BRICK MAKING

The coal measures underlying part of the parish were exploited from the beginning of the 17th century or earlier. (fn. 139) In 1607 two mines were being worked on lands belonging to John Beach (fn. 140) and John Pitt in Boulsdon tithing, where fields adjoining the lane to Clifford's Mesne later had names such as Coal grounds and Coal orchard. The mine on Pitt's land was leased to four miners, who paid him the fifth penny of their profits; two of them were natives of the Mendip region of the Somerset coalfield. (fn. 141) A coal miner recorded at Kilcot in 1608 (fn. 142) possibly worked in the detached part of Pauntley parish near by. Working of the deposits in Boulsdon apparently continued sporadically. At his death in 1652 Walter Nourse, lord of Boulsdon manor, left timber for use in the coal mines and the proceeds from them to his widow. (fn. 143) New pits were sunk by William Nourse, who inherited the manor and Great Boulsdon farm in 1757, and they presumably produced the coal that was sent from Newent to Gloucester in the winter of 1763. Nourse is said to have concluded that the operation was not worth the labour and closed his pits. (fn. 144)

A new incentive for working the deposits in and around Newent came with the promotion of the Gloucester and Hereford canal in 1789. New pits were sunk in Newent the following year and the owners sent a wagon of coal to the mayor and corporation of Gloucester as a sample of what they hoped would be a regular trade to the city. (fn. 145) At Boulsdon the main proprietors were J.N. Morse, who bought the manor in 1789, and Edward Hartland, who bought Great Boulsdon farm then or soon afterwards. In 1794 Hartland offered a lease of his land, which was said to include seams 7–8 ft deep, (fn. 146) and later, together with Morse and some Gloucester men, he formed the Boulsdon Coal Co. to develop the field and purchase pumping machinery. (fn. 147) The works in the Newent area failed to fulfil the expectations: the seams proved thin and the coal failed to compete, even in its own immediate area, with supplies brought down the Severn from Staffordshire and, increasingly from c.1811, from the developing Forest of Dean coalfield. Paradoxically, the canal intended to open up the coalfield made supplies from elsewhere easy to transport to Newent. (fn. 148) Although efforts to win coal commercially continued in nearby parts of Pauntley and Oxenhall, (fn. 149) mining at Boulsdon was said to be extinct in 1856. (fn. 150) Two disused shafts survived on Great Boulsdon farm in 1882. (fn. 151)

Stone for local purposes was dug at small quarries in various parts of the parish, notably at Clifford's Mesne where quarries in the sandstone, one of the assets of Boulsdon manor, were used for repairing the farm buildings on the estate in 1784. (fn. 152) The main quarry there, situated beside the lane from Newent near the north entrance to the hamlet, was worked commercially for building stone in the 1870s (fn. 153) but was described in 1916 as almost exhausted. (fn. 154) A similar stone, known as Gorsley stone, was used in many buildings in the parish but was produced mainly from quarries beyond its boundary in Linton. (fn. 155)

Clay was being dug for brick making in the parish by 1660 (fn. 156) and at a number of sites during the 18th and 19th centuries. There was a brick kiln on Stallions farm in 17642, (fn. 157) and another small works was in production on the south part of Gorsley common by 1790 and until the mid 19th century. (fn. 158) Another, at Clifford's Mesne, operated for a few years in the 1890s. (fn. 159) A works, producing bricks, tiles, and drain pipes, was established on the Gloucester road just to the east of Newent town before 1882 by the Onslows, lords of the manor, and continued in production until c.1900. (fn. 160)

MILLS

There were three mills on Newent manor in 1086, two held in demesne and one held by the tenants. (fn. 161) The Ell brook later drove four mills in its course through the parish. The highest, Cleeve Mill on Cleeve Lane to the east of Newent town, (fn. 162) was recorded as part of the manor from 1235. (fn. 163) It remained a corn mill on lease from the manor until 1913, (fn. 164) except that it was briefly alienated in the 1650s and passed to George Dalton, who sold it with Stardens farm back to the lord of the manor in 1664. Described then as two overshot mills (fn. 165) and in 1714 as three mills under one roof, (fn. 166) Cleeve Mill ceased to work by water power in 1959 when a flood damaged its race, but for some years afterwards it was powered by an oil engine and ground animal feed. (fn. 167) The mill and mill house, rebuilt in brick c.1800, remained in place with an iron water wheel in 2007.

Okle Pitcher mill, c.400 m above the point where Ell brook was crossed by a lane leading from the Gloucester–Newent road towards Upleadon, (fn. 168) was known as Little New Mill in 1612 when it was part of a small freehold estate (Okle Pitchard). (fn. 169) Later it may have been used to grind bark for a tannery, for it was named as 'the leather mill' on a map of 1824, (fn. 170) but it was worked as a corn mill in 1817 by James Humpidge, (fn. 171) its owner in 1838. (fn. 172) It went out of use in the 1930s when the machinery was removed and the building converted as a dwelling. (fn. 173)

Okle mill, later known as Brass Mill, stood just below the lane to Upleadon. It was recorded from 1436 (fn. 174) and probably belonged, as in the early 17th century, to Okle Clifford manor. It was a corn mill in 1627 and was converted as a brass hammer mill possibly in 1639 when it was leased to John Broughton and Richard Ayleway. In 1646 the owners of Okle Clifford, Barbara and William Keys, sold the mill to Stephen Skinner, a Newent clothier, (fn. 175) whose family remained the owners until 1727 or later. By 1690 it had been turned once more to a corn mill. (fn. 176) Thomas Green of Linton, a mealman, owned and worked it in 1827 (fn. 177) and it had an adjoining malthouse in 1838. (fn. 178) In 1919, after a damaged sluice-gate caused the mill to flood, the owner intended to give up working it, (fn. 179) and in the 1930s the building was converted as part of the adjoining mill house. (fn. 180)

Malswick mill, further downstream at a point where the Ell brook borders the Gloucester road, was recorded as a corn mill on the Newent manor estate from 1235. (fn. 181) About 1315 it was kept in hand by the lords, whose customary tenants maintained its dyke and leat as part of their services, and it was presumably the mill to which most of the tenants, both free and customary, were then required to bring their corn. (fn. 182) Malswick mill was on lease by 1389 (fn. 183) and was held by copy in the late 15th century and in the early 17th. (fn. 184) It was probably alienated from the manor by the Winters in the 1650s. Shortly before 1781 William Taylor sold it to Thomas Trounsell, a local farmer. (fn. 185) It continued in use until after the Second World War. (fn. 186)

In 1289 the prior of Newent leased a fulling (or tuck) mill on Newent manor to John the fuller. (fn. 187) The mill was powered from Peacock's brook and stood in the demesne lands north of the town, a short way above the confluence of the brook and the Ell brook (at a site adjoining the line of the later canal). In 1482, known as Pool Mill, it was in decay and was on lease to the bailiff of the manor together with two fishponds and other parts of the demesne. (fn. 188) It was in the same ruinous state in 1506 (fn. 189) but it was possibly in use again in the early 17th century when two tuckers lived in the town. (fn. 190) In 1624 James Morse held it on lease with the fishponds. (fn. 191) It was sold together with the adjoining demesne lands soon after 1657 and passed with them through the Bray, Rogers, and de Visme families. (fn. 192) The building had probably been demolished by the 1770s (fn. 193) but the large mill pond called Tuck Mill pool, evidently one of the fishponds mentioned earlier, survived until the railway was built over the site in the 1880s. (fn. 194)

In 1612 Edward Gwillim, who was possibly then owner of Great Boulsdon farm, joined in a conveyance of a water mill and land in Boulsdon to George Shipside. (fn. 195) The mill may have been on the Boulsdon brook to the east of the farm, where fields were later called Mill fields. (fn. 196)

OTHER INDUSTRY AND CRAFTS

Henry II, when confirming the earl of Leicester's grant of 1181 to Cormeilles abbey, gave it the right to work a forge on Newent manor and burn charcoal in the woods to sustain it. (fn. 197) That and presumably other bloomery forges operating in the Middle Ages left deposits of cinders in various parts of the parish, apparently adding to others left by Roman iron working. (fn. 198) Cinders were being used to fill potholes in the town's streets in 1485 (fn. 199) and large quantities were dug for the use of Ellbridge furnace established in the adjoining part of Oxenhall by the late 1630s. (fn. 200) Francis Finch, the furnace's owner, bought deposits found in a field called Cinder pits, probably in Compton tithing, in 1639 and others from the Moat estate, in Cugley, in the 1650s. (fn. 201) His successors to the furnace, the Foleys, reserved cinders in leases of their lands on Newent manor, (fn. 202) where sites yielding them included a field called Cinders adjoining Cleeve Mill (fn. 203) and Cinder field and Cinder meadow on Nelfields farm. (fn. 204) In 1727 they were being dug on the Skinner family's estate, adjoining the Gloucester road on the east side of the town. (fn. 205)

Among Newent men employed at Ellbridge furnace were two iron founders recorded in the 1680s and two 'furnace men' in the early years of the next century. (fn. 206) As mentioned above, other inhabitants found work cutting and charcoaling the coppices in local woodland, and many must have been employed from time to time in carrying and labouring tasks, including maintenance of the ponds and watercourses on Gorsley common associated with the furnace. (fn. 207) A small nail making industry recorded at Newent from the 1680s (fn. 208) was presumably established in connexion with the furnace but survived its closure c.1750. Three nailers worked in the parish in 1822 (fn. 209) and the trade was represented there in the 1850s. (fn. 210)

A glassworks, operated by French Huguenot families, was established in the late 16th century at Yartleton on the lower slopes of May hill. It gave its name to a small hamlet and inn in Taynton parish but the main site was on land known as Yartleton waste (later Glasshouse green) in the adjoining part of Newent in the angle made by the junction of lanes from Cugley and Clifford's Mesne. Between 1598 and 1634 several glassmakers were recorded in Newent, including Abraham Liscourt, (fn. 211) who c.1607 was paying a rent of £10 for the Yartleton glasshouse to the lord of Newent manor, (fn. 212) and John Bulnoys (or Bolonies), who in 1624 occupied one of a small group of cottages that had been built on the green. Another of the cottages was then occupied by Francis Davis, a potter. (fn. 213) Glass making at Yartleton had probably ceased by 1640, when a widow Davis occupied the glasshouse and paid a rent of £1 for it, (fn. 214) but pottery making appears to have continued at the site until the mid 18th century: between 1676 and 1746 six potters, four of them members of the Davis family, were mentioned among inhabitants of Newent parish. (fn. 215) On Glasshouse green, from which all the dwellings were later removed, many fragments of glass and pottery have been unearthed. (fn. 216)

In the late 13th century and the early 14th, when a fulling mill operated next to Newent town (fn. 217) the town's tradesmen included weavers, fullers, and dyers. (fn. 218) In the early modern period cloth making was probably the town's principal industry. Several clothiers were based there at the end of the 16th century, (fn. 219) and townspeople listed for the muster of 1608 included two fullers (tuckers) and 14 weavers, the latter including three employed as journeymen by clothier or master weaver Roger Hill; (fn. 220) another six weavers were listed then in outlying parts of the parish. (fn. 221) The industry maintained its importance during the 17th century, when leading clothiers included Stephen Skinner (d. 1674), who purchased demesne land from the manor in 1657, (fn. 222) and Miles Beale (d. 1698). The latter's son, Miles Beale (d. 1713), (fn. 223) had racks for drying cloth in the grounds of the Court House. (fn. 224) In the 1680s there were c.5 clothiers in Newent (fn. 225) and c.20 or more men engaged in weaving and dyeing (fn. 226) but, as in other small Gloucestershire towns (outside the Stroud and Dursley areas), Newent's clothmaking industry was in decline by the early 18th century. Few cloth workers were recorded after the 1720s, and the clothier Ailway Parsons (d. 1764) appears to have been the last representative of the entrepreneurial class of the industry, (fn. 227) which had apparently died out entirely in Newent ten years later. (fn. 228)

Three stocking weavers were mentioned in Newent town in 1766 (fn. 229) but that industry, evidently the frameknitting mentioned c.1775, (fn. 230) seems to have been shortlived. Flax dressing employed some Newent men in the late 17th century and the early 18th, (fn. 231) and the town had two linen manufacturers in 1830. (fn. 232) In the late 16th century and the early 17th several men were presented in the manor court for soaking hemp in the pond and millstream at Cleeve Mill and in Peacock's brook in the town. (fn. 233) The fibres were perhaps supplied to rope makers in Gloucester or elsewhere. In the mid and later 19th century the wives of cottagers in the Kilcot area made gloves, probably as outworkers for Worcester firms. (fn. 234)

Tanning was an important trade in Newent, where the woodlands provided the required oak bark and the butchering trade a ready supply of hides. In 1611 and 1619 the manor court was at pains to enforce on the butchers from surrounding villages who sold meat in the Newent market a statutory obligation to bring their hides and tallow as well. (fn. 235) Seven tanners were listed in the parish in 1608, four under Boulsdon and one each under the town, Malswick, and Cugley, (fn. 236) and between 1631 and 1640 four Newent farmers apprenticed their sons to tanners in Gloucester. (fn. 237) A tannery was established in the town, backing onto Peacock's brook on the west side of Culver Street, shortly before 1652 and was bought by Edward Bower in 1671. (fn. 238) Eleven tanners recorded in Newent in the 1680s included four members of the Bower family, which, with the White family, dominated the trade in Newent during the 18th century. (fn. 239) The Culver Street tannery remained in use until 1914, worked in its final years by F.W.H. Lees & Co. (fn. 240) Some of the buildings survived in 2007 adjoining the substantial dwelling (the Tan House) built by the Bowers in the late 17th century. (fn. 241)

MARKETS AND FAIRS

In 1226 Henry III, while passing through Newent, granted Cormeilles abbey the right to hold an annual fair on the eve, feast day, and morrow of the Purification (2 February). The grant was provisional until the king's majority (fn. 242) and was perhaps not confirmed when he declared himself of full age the next year, for in 1253 he made another grant to the abbey of a four-day fair around the feast of St Peter ad Vincula (1 August), together with a weekly Tuesday market. (fn. 243) In 1313 Edward II made a new grant of a market on Friday and a four-day fair around the feast of SS Philip and James (1 May); (fn. 244) the new market day replaced the existing one but later that century the fair was still being held in August rather than at the new date. (fn. 245)

Markets

An inquisition appointed to find out if the market established in 1253 was harming markets near by at Gloucester and Newnham concluded in 1258 that it fitted well into the pattern of local trade, as Welsh cattle dealers could circulate between the markets at Ross-onWye on Thursdays, Gloucester on Saturdays and Wednesdays, Newnham on Sundays, and Newent. The Newent market was said to receive the corn formerly carried from the surrounding area to Gloucester. (fn. 246) The town proved capable of carving out for itself a sufficient trading area between those of Gloucester and Ledbury and was probably a major factor in the demise of an older market at Dymock. In 1291 the tolls taken by the lords of Newent manor from the market and fair produced on average £5 a year. (fn. 247) There was evidently a falling off in the volume of trade later in the Middle Ages: the tolls from the fair produced 20s. in the year 1394–5 (fn. 248) and those of both market and fair only 10s. in 1481–2 and 29s. in 1505–6, over and above the cost of stationing men, presumably toll collectors, at the entrances to the town at fair time. (fn. 249)

About 1775 the Newent market was said to suffer from the poor state of the local roads. (fn. 250) Bad roads appear, however, to have been to some extent a protection to its trade, for, according to another writer, the improvements made by turnpike trusts in the early 19th century ruined it by laying it open to competition from Gloucester, where local farmers now found it practical to go on market days. (fn. 251) No doubt smaller producers and market customers were also finding the trip more practicable in 1822 when three carriers ran from Newent to Gloucester on its two market days; one of the carriers also ran to Ross-on-Wye on its market day. (fn. 252) The Newent market was described as very small in 1830, (fn. 253) and by 1870 it was being held only once a month, mainly for the sale of livestock. (fn. 254) The opening of the railway link with Gloucester in 1885 reduced the amount of stock brought to Newent for sale, (fn. 255) though the market still produced £20 a year in tolls in 1902 (fn. 256) and its meetings were increased again, to once a fortnight, before 1910. It apparently continued on that basis until the Second World War. (fn. 257)

From the 13th century the market was held south of the Newent priory precinct in the central part of the town's main thoroughfare, where there was probably once a larger open area than the small market place that later survived in the entrance to Bury Bar Lane. Market trading apparently extended into the west part of Church Street where there was a row of selds c.1315. Part of the building called the boothall, standing by the priory gate on the north side of the market place, was presumably used for trade in the Middle Ages, (fn. 258) and before 1625 a separate market house was built. That was replaced in 1668 by a new building on a different site, at the north end of the market place. (fn. 259) The open, arcaded lower floor of the new market house was used mainly for the sale of butter in the late 18th century, (fn. 260) while the room above was used for town meetings. The building was in a dilapidated state by 1864 when the lord of the manor, R.F. Onslow, restored and enlarged it. (fn. 261) In the 1870s Onslow moved livestock sales from the market place to a cattle market, fitted with iron pens, on an adjoining site further along Bury Bar Lane. (fn. 262) At the sale of the manor estate in 1913 the auctioneer James Clark bought the rights to the market and tolls. The following year he sold the market house to two sons of Henry Bruton (d. 1894) of Gloucester, an auctioneer who had begun his business in Newent, and they donated it to the parish council in his memory. (fn. 263) In 1944 G.H. Smith sold the remaining rights and assets of the market to a committee formed to build a war memorial hall for the town; it conveyed the market place to Newent Rural District Council (fn. 264) and, some years later, built the hall on part of the old cattle market site.

Fairs

By the start of the 18th century a total of four fairs were held at Newent, on the Wednesday before Easter, the Wednesday before Whitsun, 1 August, and the Friday after 8 September; according to one account, the two spring fairs had been granted by Henry VIII and the two summer fairs granted (presumably confirmed in the case of the August fair) by James I. (fn. 265) Newent's four annual fairs apparently did a modest amount of trade in 1735 when Thomas Foley granted a 21-year lease of his tolls, together with a small farm at Malswick, at a total annual rent of £32 10s. (fn. 266) In the 1760s they dealt mainly in cattle, horses, and cheese, and the September fair was a sheep sale; the calendar change of 1752 had altered the day of the last to the Friday after 19 September and the August fair to 12 August. (fn. 267) The fairs were held in the streets of the north part of the town in the 18th century when New Street had the alternative name of the Beast Fair (fn. 268) and Crown Hill, the adjoining part of the Ross road, was sometimes known as the Horse Fair. (fn. 269) Later, however, horse sales were held a bit further out of town, in a field in the angle of the Ross road and the lane leading to Oxenhall (Horsefair Lane). (fn. 270) In the mid 19th century the fair on 12 August was apparently the principal one, doing a good trade in sheep and horses, (fn. 271) but the September fair was the only one that survived by the end of the century when onions, brought from the Vale of Evesham, were an important commodity sold at it. (fn. 272) The Onion Fair, as it became known, was revived in the late 20th century as a pleasure fair. (fn. 273)

DISTRIBUTIVE AND SERVICE TRADES

The economy of Newent town in the Middle Ages was typical of small inland market centres, with a predominance of tradesmen supplying foodstuffs and basic crafts to the surrounding area. Townspeople listed in rentals of 1278 and c.1315 included those surnamed cordwainer, glover, skinner, tailor, smith, hooper, tiler, carpenter, wheelwright, cook, baker, butcher, mustard seller, and mercer. (fn. 274) In 1297 a group of men attempting to secure from Cormeilles abbey greater powers for the town court included four bakers, two cordwainers, a cook, a brewer, and a tailor, and, representing Newent's cloth-making industry, a weaver and a dyer. (fn. 275) For commodities not available locally the town looked to Gloucester, to which in 1258 dealers were said to go for products such as salt, fish, and leather (fn. 276) and through which John Anketil, a Newent man trading in wine in 1287, presumably got his supplies. (fn. 277) The purchase of items for local distribution was probably the business of the group of Newent men who traded regularly in Gloucester's markets in the late 14th century. (fn. 278) Eels and herrings were sold in Newent in the 1360s, (fn. 279) and in 1500 at least five townspeople retailed fish. (fn. 280) The processing and sale of meat, probably connected with the Welsh cattle trade mentioned in 1258, was long a major occupation of the town. In 1323 17 Newent men were presented for infringing the assize of meat, (fn. 281) and as many as 10 butchers were regularly presented for the same in the early 15th century. (fn. 282) Fourteen men had infringed the assize of bread in 1333, (fn. 283) though later the bakers feature in the presentments in more modest numbers. Larger numbers were engaged in the brewing and selling of ale, often a trade for women: in 1367 22 people were described as ale sellers or alehouse keepers, in 1408 11 as brewers and 14 as alehouse keepers, and in 1527 17 as brewers. (fn. 284) The numbers involved in the presentments indicate that large volumes of staple foodstuffs were produced for surrounding villages and hamlets rather than for the town alone.

In the early modern period, while manufacturing activities gave Newent parish as a whole a varied economic character, for Newent town its role as a provider of foodstuffs and minor crafts and services to its area remained the defining characteristic. In the early 18th century one account said that its trade depended chiefly on its markets and fairs (fn. 285) and another described its 'manufacture' as that carried on by such as tanners, tailors, shoemakers, blacksmiths, innkeepers, and butchers. (fn. 286) About 1775 its business was defined as the supply of 'common necessaries' to surrounding villages. (fn. 287) Apart from the cloth workers, millers, and tanners mentioned above, the muster roll of 1608 listed 47 tradesmen and craftsmen in the town, including 8 shoemakers, 7 tailors, 6 butchers, and 5 smiths. Inhabitants of the outlying parts of the parish at that time included 3 smiths, 2 carpenters, and a cooper. (fn. 288) A similar trading character is revealed in the parish registers of the late 17th century and the early 18th, where almost all the male parishioners mentioned are identified by trade. In the 1680s some 190 men pursued 46 different occupations and, apart from those engaged in cloth working and tanning, the largest categories were shoemakers (29), butchers (24), carpenters (11), blacksmiths (9), and tailors (9). (fn. 289) The number of butchers reflects the town's role in supplying meat beyond its immediate area. About 1725 it was recorded that Newent butchers attended markets at Gloucester, Ledbury, Ross, and Mitcheldean and claimed to slaughter twice as many animals as did the butchers of Gloucester. (fn. 290) The building trades were represented chiefly by the carpenters and by a few thatchers in the late 17th century; men described as masons became more numerous in the first few decades of the next century but were probably mostly builders in brick rather than stone. (fn. 291) A handful of tradesmen of a more specialist character recorded at the period included two gunsmiths, a clockmaker, a locksmith, a pewterer, and a millwright. (fn. 292)

The town also offered scope for a wealthier class of retailer in the late 17th and 18th century. The mercers and chandlers William Nelme (d. 1702), (fn. 293) Acton Woodward (fl. 1686, 1714) and his son Acton (d. 1718), (fn. 294) and Edward Morse (d. 1759) and his son J.N. Morse were dealers in and mortgagees of property both in the town and the surrounding area. (fn. 295) Among the professions two or three surgeons and apothecaries were usually practising in the town in the 18th century, including several members of the Richardson family. (fn. 296) An attorney mentioned in 1713 (fn. 297) is the sole representative of the legal profession recorded in the early 18th century, but c.1792 five attorneys were based in the town. (fn. 298) The number at the latter date presumably reflected the extra business promised by the schemes for the canal, coalfield, and Newent spa; when the attorney Matthew Paul died in 1801 two men competed to succeed to his practice. (fn. 299)

Although the prospects for development and expansion in the late Georgian period were largely unfulfilled and some parts of its marketing role were assumed by Gloucester, Newent town remained a busy centre during the 19th century. In 1851 151 of the heads of households enumerated in the town were engaged in trades and crafts, usually on a small scale. The largest employers were a builder with 10 men at work for him, a fell monger and woolstapler with 8, and a master carpenter with 6. Shoemakers (24), carpenters (12), and tailors (11) formed the largest groups, and there was a range of retailers such as grocers, drapers, and ironmongers but no shops dealing in luxury items. Only four townsmen were butchers, indicating that the trade was by then confined to supplying only the town and its immediate area. The canal provided little direct employment – in 1851 only a barge owner, a wharfinger, and a few watermen lived in the town or at Almshouse Green in Malswick (fn. 300) – but the main cargo it carried kept in business a number of coal merchants in the early 19th century. Two surgeons and two firms of solicitors were in business in the 1820s; the principal solicitors, occupying most of the official posts, were the partners Oliver Ainsworth and Thomas Cadle. Four solicitors working in Newent in 1851 included Edmund Edmonds, (fn. 301) an influential figure until 1872 when the circumstances of his wife's death ruined his reputation. (fn. 302) Newent's first bank appears to have been a branch of the Gloucestershire Banking Co. opened in 1866; (fn. 303) earlier, banking was no doubt one of the services provided by Gloucester. The larger of the outlying hamlets of the parish, Kilcot, Gorsley, Clifford's Mesne, and Brand Green, had men pursuing basic rural trades and crafts, such as blacksmiths, masons, carpenters, wheelwrights, and hauliers, until the mid 20th century, as well as one or two shopkeepers. Blacksmiths and carpenters were also to be found in some smaller hamlets, including Botloe's Green. (fn. 304)

Locally-based trades and crafts continued to provide the livelihood of the majority of the working population of Newent town up to the mid 20th century, when people began to commute to work in Gloucester and, in the 1970s, also to the Rank Xerox factory at Mitcheldean. Its character as a dormitory town for workers in Gloucester and also Cheltenham became more marked with the addition of large new housing estates in the late 20th century, (fn. 305) though some local employment was provided by the development of a business park on the Gloucester road, east of the town, from 1993; (fn. 306) manufacturers of double-glazing, security doors, and computer software were among firms that established themselves at the site. Another small development comprised a group of office buildings with geodesic domes on Cleeve Lane. The growth in the town's population preserved its main thoroughfare as a shopping street at the beginning of the 21st century, with over 40 small shops remaining in 2007, together with a supermarket opened in 2000 (fn. 307) and a range of other businesses including four public houses, two banks, and two firms of solicitors.