Survey of London: Volume 47, Northern Clerkenwell and Pentonville. Originally published by London County Council, London, 2008.

This free content was digitised by double rekeying. All rights reserved.

'Percy Circus area', in Survey of London: Volume 47, Northern Clerkenwell and Pentonville, ed. Philip Temple (London, 2008), British History Online https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vol47/pp217-238 [accessed 15 April 2025].

'Percy Circus area', in Survey of London: Volume 47, Northern Clerkenwell and Pentonville. Edited by Philip Temple (London, 2008), British History Online, accessed April 15, 2025, https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vol47/pp217-238.

"Percy Circus area". Survey of London: Volume 47, Northern Clerkenwell and Pentonville. Ed. Philip Temple (London, 2008), British History Online. Web. 15 April 2025. https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vol47/pp217-238.

In this section

CHAPTER IX. Percy Circus Area

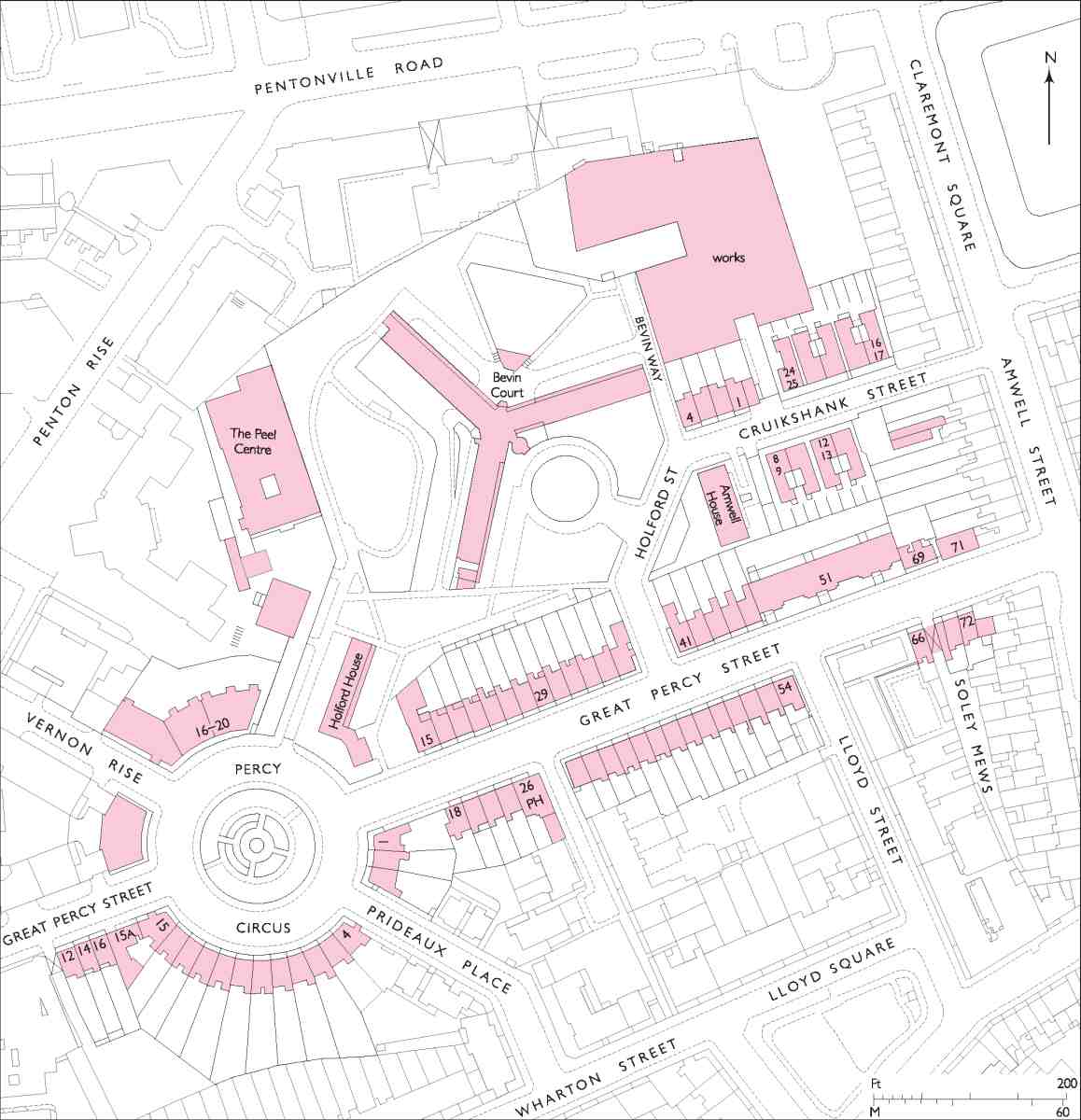

278. Percy Circus and Bevin Court area from the north-east in 2001

The hillside area described in this chapter was Clerkenwell's last big undeveloped space, mainly consisting of a single field belonging to the New River Company. It was mostly built up in the 1840s, though development began in the early 1820s with Great Percy Street (partly on the adjoining estate of the Lloyd Baker family). This was followed by Percy Circus (1841–53) and Holford Square (1841–8), and building in Great Percy Street itself also continued until 1853. There has been considerable redevelopment, the main loss being Holford Square, which was heavily bombed in the Second World War and replaced by the radial-winged Bevin Court flats, an arresting monument amidst the placidity of northern Clerkenwell. Percy Circus too was severely bomb damaged but survives, a significant and unusual piece of early Victorian townscape. Chronologically disparate though it now is, the area's topography has integrity arising from strongly geometric planning and good architecture (Ills 277–80).

279. Percy Circus and Bevin Court area

280. Percy Circus and Holford Square area, c. 1874

A general account of the New River Company's estate, outlining its history, first development and architectural character, is given in Chapter VII. Accounts of Prideaux Place and Cumberland Gardens (developed in conjunction with the Lloyd Baker Estate), are given in Chapter XI, and the westernmost parts of the estate, in and around King's Cross Road and Penton Rise, are described in Chapter XII.

Myddelton Gardens and the London Gymnastic Institute

The laying out of the Lloyd Baker estate in the 1820s and 30s left the New River Company in possession of isolated open ground to the north, previously known as the Hanging Field. This had been used by Richard Laycock, the tenant of the New Inn Farm, for brickmaking from 1811, and from 1820, in the absence of interest in building leases, for subletting as small pleasure gardens, in effect allotments, some with little summer houses. These were called Myddelton Gardens. (fn. 1)

In the late 1820s, when it would have been clear that further development was contingent on the market picking up again, one piece of ground found another, if shortlived, use. This was at the end of a road, later to become part of Great Percy Street, leading from Amwell Street as far as Cumberland Terrace and the New River Company's West Pond. There a rectangular plot, previously one of the larger pleasure gardens, was used as an open-air gymnasium in the late 1820s. The site is now covered more or less by Nos 18–26 Great Percy Street, the west side of Cumberland Gardens and Nos 1–3 Percy Circus (Ill. 281).

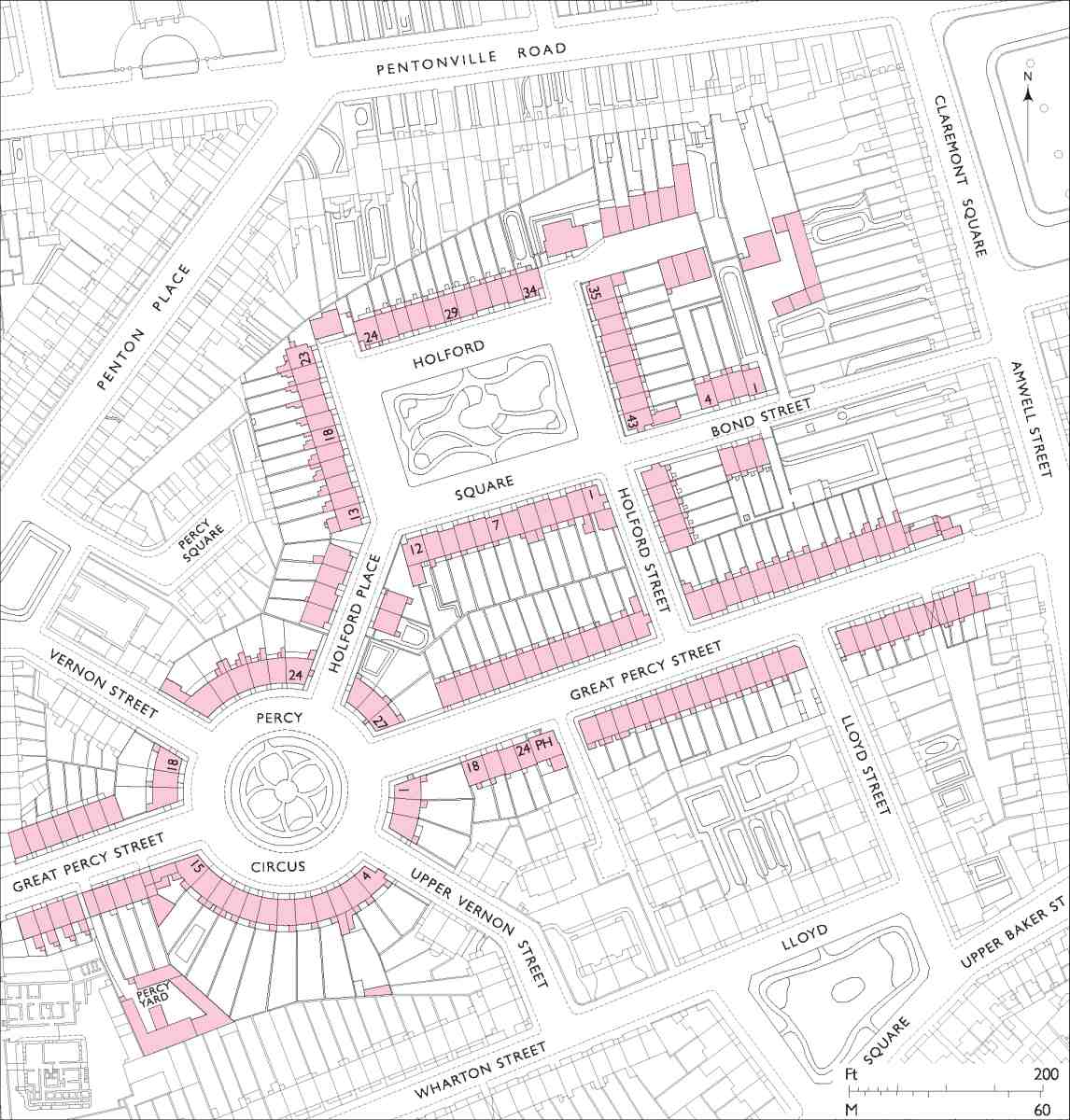

281. The London Gymnastic Society gymnasium, Myddelton Gardens, in 1826, looking south-west

The gymnasium was the project of a German immigrant, Professor Karl Voelker, and tied up with a burst of enthusiasm for German-style physical culture. Voelker was a pupil of Professor Friedrich Ludwig Jahn, the Prussian founder of the Turnverein movement, for whom physical education was vital to personal and national character, and a levelling force across classes. Both men had left Berlin to fight for their country in 1813–15, before separately arousing official hostility, Jahn going to prison and Voelker eventually ending up in London. In 1825 Voelker established a gymnastic school off the New Road near Regent's Park, launching it with a testimonial from Robert Owen. The following year a London Gymnastic Society was founded on the initiative of John Borthwick Gilchrist, philologist, orientalist, republican and co-founder in 1823 of the London Mechanics' Institution. Gilchrist, whose enthusiasm for gymnastics arose from having lived in India, proposed hiring a ground for exercises, to do for the bodies of 'mechanics' what the institution was doing for their minds. With Voelker's backing and guidance the new society set up apparatus at Myddelton Gardens and established the London Gymnastic Institute. This emphasized the moral and spiritual value of physical exercise and was an immediate success, attracting many hundreds of young men, as well as spectators. Summer festivals were held in 1827 and 1828, and branches were established at Voelker's Marylebone site, in Hackney and in Southwark. George Cruikshank was a leading and, in relation to Myddelton Gardens, local advocate of this self-improvement movement. Having patronized, drawn and publicized the Marylebone site, he sat on the institute's managing committee. The society's sudden demise c. 1829 followed the departure of Thomas Latimer, its energetic secretary; with it the institute too seems to have come to an end. (fn. 2)

Great Percy Street

282. Great Percy Street, view of upper section, looking east to Amwell Street in 1906

283. Nos 19–39 Great Percy Street (left to right) in 2005. W. C. Mylne, surveyor, 1839–43

Great Percy Street, connecting Amwell Street with King's Cross Road by way of Percy Circus, was planned by 1818 and its exact line settled with the Lloyd Baker Estate in 1820. It takes its name from Robert Percy Smith, Governor of the New River Company from 1827 to his death in 1845. Above Percy Circus the street has harmony if not unity, achieved by two estates working together, much as on Amwell Street. The broad road sweeps downhill between stately terraces, in this instance without shops or much traffic (Ills 282, 283). Buildings on the south side that follow the type established on the New River estate in the 1820s were, in fact, on Lloyd Baker ground, in what was originally Soley Terrace. Otherwise, with the exception of Amwell Cottage, there is now nothing else here earlier than 1839. At that point the New River Estate began to countenance some updating of its architectural vocabulary. None of the later houses, though, rival the refined Italianate idiom of the Percy Arms public house of 1839–40, designed by R. C. Carpenter. The upper part of the street was completed in 1843, but it was another decade before the lower stretch beyond Percy Circus was finished. The latter section has been largely redeveloped, and now seems an entirely different place. The street is presented here in east-west sequence, crossing from side to side to maintain a broadly chronological account of development. (fn. 3)

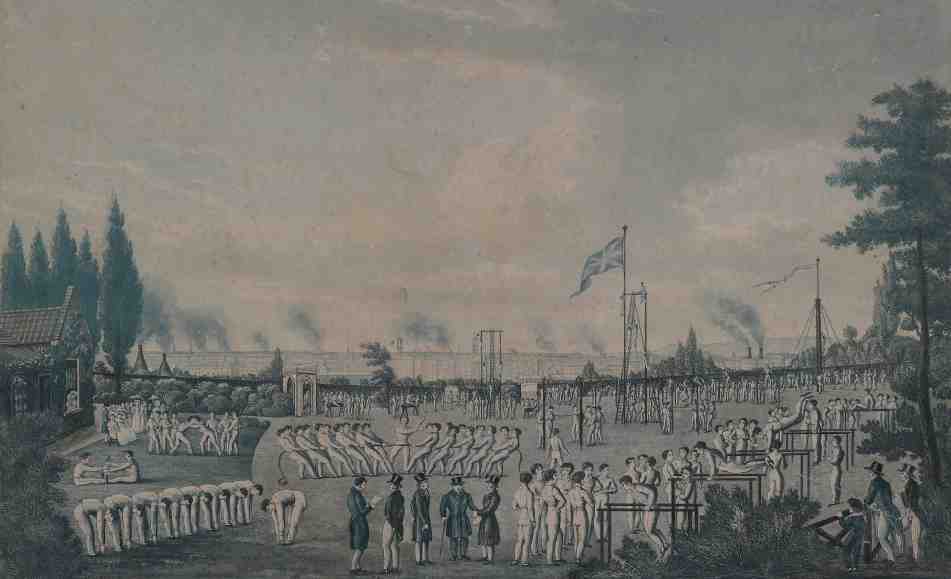

No. 69, Amwell Cottage

Of only two storeys and double-fronted, this stucco 'cottage', as it was first described in the ratebooks, is an oddity in this location, suggesting ignorance of, or insouciance about, the high-density development planned by the New River Company. It was built in 1821–2, before anything else was standing in the immediate vicinity, though Amwell Street was already being laid out and the new cottage was soon followed by a row of houses to its west (Ills 284, 285). Originally called Myddelton House, the small-roomed dwelling may have been built in connection with Richard Laycock's Myddelton Gardens venture, perhaps as a kind of keeper's lodge. There appears to be no mention of the building in the New River Company records, but its architectural elements fall within the estate norms and it may be that Mylne supplied the designs. (fn. 4) In 1843, when Joseph King took up residence, it became a dairy, which it remained until the 1960s. The adjacent and much-altered garage building at No. 71, erected as an outbuilding to the cottage c. 1890, when David Williams, cow-keeper, had the premises, perhaps served as a dairy, cow-house and stables. (fn. 5)

284. Great Percy Street, north side, in 1939. Right, Amwell Cottage (No. 69), 1821–2; left, Amwell Terrace (Nos 55–67), 1822–6, demolished. W. C. Mylne, surveyor

285. Amwell Cottage, front elevation in 1933

Nos 55–67 (demolished) and Sanders House

The seven houses that formerly stood immediately west of Amwell Cottage were originally known as Amwell Terrace (Ill. 284). They were built in 1822–6 following an agreement with William Oliver, Nos 59 and 61 by Oliver himself, the others by George Paul. The whole group, with the later Nos 51 and 53 (see below), was cleared after bombing in April 1941. (fn. 6) The site was redeveloped by the New River Company in 1948–50 as Sanders House (No. 51), designed by Daniel Watney, Eiloart, Inman & Nunn, and named after C. S. Sanders, the New River Company's long-serving Surveyor and later Secretary. More than any other New River Company development this stock-brick block of twenty flats has the clean horizontal lines that hint at awareness of Danish housing, widely influential in the late 1940s. (fn. 7)

Nos 28–72

Eastwards of Cumberland Gardens, the houses on the south side were built on ground belonging to the Lloyd Baker family. Twenty-three houses in two ranges, separated by Lloyd Street, were erected here in the late 1820s and early 30s under the name Soley Terrace, for reasons unknown; the name was abolished in 1862.

As in Amwell Street, the Lloyd Bakers were given access to the frontage along Great Percy Street where it abutted on their land, under an arrangement of 1820. (fn. 8) Here too it had been agreed that the houses would 'correspond' with those already built there by the New River Company. When work started on Soley Terrace, only Amwell Terrace opposite had yet been built in Great Percy Street by way of precedent. The builders broadly followed W. C. Mylne's elevations, retaining the characteristic relieving arches over the first-floor windows; as on the company's houses there are variations in detail. The slightly earlier eastern range differs from the rest of Soley Terrace in not having the white-stone impost bands between the relieving arches. Each range has iron window guards of a different stock pattern.

Work on the eastern range (Nos 56–72) had begun by 1828 and all nine houses were occupied by 1831. (fn. 9) The developer was Robert Rawlings of Red Lion Square. In 1824 Rawlings had agreed to complete Thompson's Terrace in Amwell Street, after the failure of the original builder, and to develop the ground at the back. So his 'take' included the east side of Lloyd Street, the return frontage along Great Percy Street, and the hinterland where Soley Mews was laid out. Rawlings subcontracted part of his agreement to his manager, Benjamin Bellamy, a carpenter in Spa Fields, who before succumbing to bankruptcy in 1826 probably put in some foundations. (fn. 10) The leases for this range were all issued in 1830. Rawlings himself was the lessee of Nos 64–68—then still 'in carcase'—but within days he relet them to the Hoxton builder, Benjamin Matthewson, who must have finished them off and may have built the carcases. (fn. 11) No. 68 incorporates the arched entrance into Soley Mews (Ill. 286). The end house, No. 56, at the corner with Lloyd Street, where it had its entrance, was taken by George Farmiloe, the St John Street lead and glass merchant, though not for his own occupation. (fn. 12) This house, together with Nos 58–64, was destroyed or damaged by bombing during the Second World War: their sites are now occupied by the return wing of Cable House in Lloyd Street (see page 285).

286. Nos 66–72 Great Percy Street (part of Soley Terrace) in 2007

The fourteen houses west of Lloyd Street, now Nos 28–54, were built in 1828–31 under an agreement with George Tindall, gentleman, and George Paul of Great Saffron Hill, builder, proposed in 1825 but not signed until December 1826. (fn. 13) Slow to complete what they had undertaken, in 1829 Tindall and Paul blamed the downturn in the building cycle: 'what little ground we have let in Soley Terrace we have got nothing by and there is yet ground for five houses which we have offered over and over again at five pounds a house—the price we give'. (fn. 14) A couple of houses went to Tindall and Paul, but most to three carpenters presumably involved with the work, Thomas Herridge, Lazarus Holmes and Edward Lord. The houses quickly found tenants, Paul himself being the first occupant of No. 54. (fn. 15)

While the building slowdown of the 1820s delayed Soley Terrace for only a few years, on the New River estate Mylne waited until late 1836 before resuming development, ensuring that the roadway of what was initially called Percy Street East was at last fully made up the following year. (fn. 16) Letting of building ground recommenced in 1838, Mylne seemingly supplying designs as before—with one notable exception, a public house.

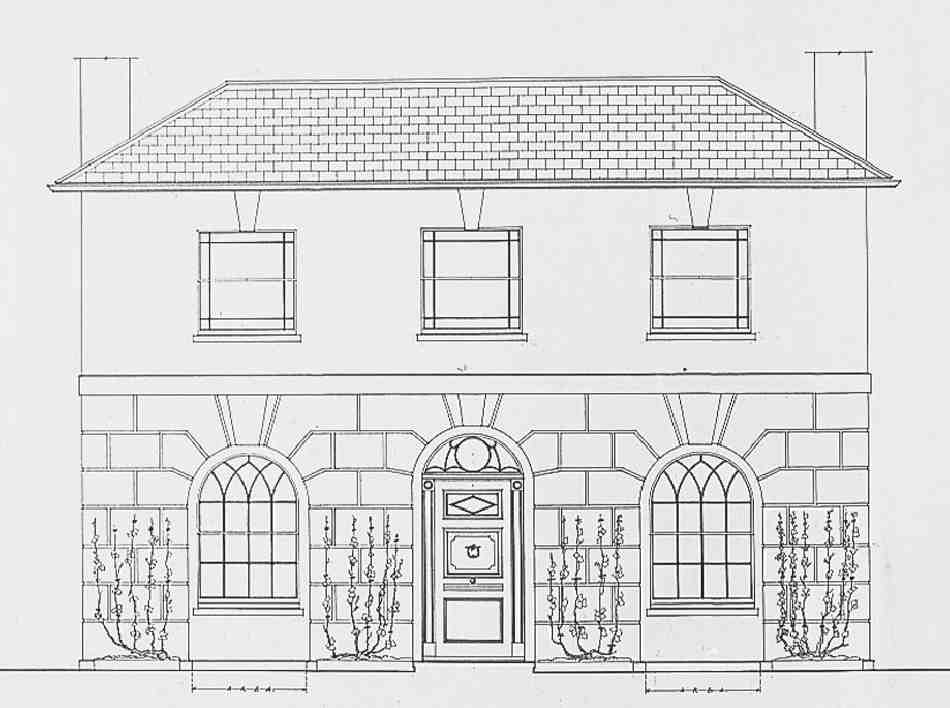

No. 26, Percy Arms

In July 1839 the architect R. C. Carpenter wrote to the New River Company on behalf of E. and W. Calvert, brewers, proposing to build a public house on Great Percy Street's west corner with what is now Cumberland Gardens, and two houses adjoining at No. 24 Great Percy Street and No. 7 Cumberland Gardens. Approval was given on the basis that this was to be the only public house on the 'Hanging Field' side of the estate. Built early in 1840, the Percy Arms was unlike anything else on either the New River or Lloyd Baker estates, and is a highly considered piece of fashionable architecture.

Carpenter's brief, no doubt, was to provide a pub which would satisfy the New River Company in upholding the respectable appearance of the estate, as well as promising good profits for the brewers. He took his Italianate design directly from a West End clubhouse, Charles Barry's Travellers' Club of 1829–32, drawings of which had been published by John Weale in June 1839. (fn. 17) Borrowing elements from both its main elevations, he reorganized them for his smaller and more vertically proportioned building. (At the same time the scholarly young architect was working with his jack-of-all-trades father on the development of Lonsdale Square in Islington, where Italianate designs of 1839 were altered to Tudor-Gothic in 1840–1. (fn. 18) Before long he was to focus on church design and Puginian Gothic.) The design of the Percy Arms was sufficiently distinguished for Weale to publish it too, as an exemplar in its own right (Ills 287, 288). (fn. 19)

287. Percy Arms public house from the north-east in 2005

288. Percy Arms public house, No. 26 Great Percy Street, plans and elevations, R. C. Carpenter, architect, 1839–40

Inside, the pub was planned for a superior clientele, with minimal space for standing and a clubroom on the first floor. Its architectural pedigree proved enduringly appropriate, and in 1898 it was described as 'the one public house of this respectable district, used much as a club by the male inhabitants'. (fn. 20) But at the time of building it had a negative effect on the further development of the street (see below).

A skittle-alley extension of 1891 alongside Cumberland Gardens was latterly replaced by a conservatory. The Percy Arms closed at the beginning of the twenty-first century, and plans for a residential conversion were refused permission in 2005. (fn. 21)

Other houses

While the pub was going up, progress was being made on the north side of the road. Francis Sandon, a builder of White Conduit Street, had agreed to build seven houses (Nos 41–53) in 1838. The New River Company's ambitions for improving the tone of its estate at this juncture are evident in a shift with this agreement from 17 ft to 18 ft fronts, and from three to four storeys (that is, from eight rooms to ten). Nos 51 and 53 (now replaced by Sanders House) went up in 1839, as did Nos 45–49, for which William James Boulton had taken responsibility. Boulton completed the job at Nos 41 and 43 in 1841, by which time Sandon was on the verge of bankruptcy. In 1839 John Lowther, a builder of Queen's Row in the New (Pentonville) Road, undertook ten more four-storey houses (Nos 21–39). He completed Nos 37 and 39 in 1839–40, but could not let them, complaining in 1841 that eight-room houses were 'more in keeping with the neighbourhood since the Public House has been built'. (fn. 22) Within a year he was bankrupt. William Watkins, an Islington builder with links to James Rhodes, took over Lowther's agreement and built Nos 21–35 in 1843. (fn. 23) Operating as a speculator, R. C. Carpenter had in 1841 taken the westernmost plots down to Percy Circus on both sides of Great Percy Street, along with the first part of the Circus itself. The company's aspirations of three years earlier had proved unsustainable and, it seems, Lowther's observation was noted, as three-storey houses were built here, Nos 18–24 within the year, Nos 15–19 by 1842. No. 19 originally included a shop. Carpenter's principal builder was Thomas Gates James, who lived at No. 7 River Street. (fn. 24)

Changes in scale aside there was a gradual move away from the architectural vocabulary of the 1820s. Sandon's speculation at Nos 41–53 echoed Amwell Terrace in its seven-bay composition, but with first-floor stucco architraves and stucco cornices on the outer pairs, and no blind arcading (Ills 282, 283). The development by Lowther and Watkins at Nos 21–39 marches commandingly and voluminously up the hill, cornice bands stepping up under attics, some of which have round-headed windows, perhaps simply for the sake of variety, something that had not previously been a deliberate aim in the estate's longer terraces. Only the pair that Lowther finished himself has upper-storey architraves. Watkins left his windows bare, while introducing a second tier of iron guards and re-introducing round-arched ground-floor windows. Carpenter's smaller houses have or had simple stucco architraves, but are otherwise unremarkable, and entirely typical of their date (Ill. 289). Cornices on all these houses hide butterfly roofs, unlike Soley Terrace. Other details reflect changing fashions, from acanthus balconies to rectangular fanlights, often with lozenge leading, as on the Lloyd Baker estate. Generally, there are two-room rearstaircase plans, the end-of-terrace houses differing with side entrances, some in porches, the best of these being at No. 39. The porch at No. 15 was added in 1853 and that at No. 18 was rebuilt in 1976–7. There has been some refronting, in 1908–13 and since. (fn. 25)

The south side of the short western section of Great Percy Street beyond Percy Circus was built up in 1840–2. Nos 12–16, which survive, were built by Samuel Harris. Nos 2–10, pulled down for the new Clerkenwell police court (see page 308), were put up by Charles Frederick Smyrke, a timber merchant, in front of his development of Percy Yard. This timber yard, occupied by a billiardtable manufacturer in the 1850s, is now a car park for King's Cross Police Station. The north side here, entirely replaced by what is now the Travelodge Islington hotel, was developed in two parcels. Nos 1 and 3, of 1844–6, were built by William Morgan, a box maker, and Nos 5–13, of 1847–53, by Abraham Riddiford, a builder working under James Rhodes's agreement of 1847 whereby Rhodes undertook to complete development on the New River estate (Ill. 290). (fn. 26)

289. Nos 18 and 20 Great Percy Street, reconstructed front elevation and ground-floor plan. R. C. Carpenter, developer, 1841

As the development history of Great Percy Street as a whole has implied, the New River Company's aspirations for this part of its estate were not wholly successful. While Nos 57 and 67 were occupied by solicitors and their families in 1841, No. 51 had become a lodging-house, run by Maria Louisa Bell, alone with her five children. James Harrison, an architect, lived at No. 55 for a few years from 1841, and John Brain, an engraver, was the first occupant of the smaller house at No. 15 in 1842; they later worked together in Holford Square (below). No. 16 Great Percy Street was already divided into three households in 1851, and in 1871 five houses were described as lodging-houses and many households took in lodgers. In 1898 Charles Booth's inspectors found the west end of Great Percy Street 'all lodging houses'. (fn. 27) Houses that remained undivided had mixed trade and professional occupancy. No. 15 was extended to the rear in 1920 when it was used as offices by the National Union of General Workers for part of their National Health Insurance Department. (fn. 28) As elsewhere on the estate, further sub-division and municipalization have been followed by gentrification.

Percy Circus

Percy Circus was begun in 1841, and not brought to completion until 1853. Uniquely complex, it has five unevenly spaced entry points, and is laid out on the side of a steep hill (Ills 279, 280, 291–4). From this difficult starting point, success was achieved through picturesque variation in the house elevations, deftly enlivened by recession and projection, adding up to what Christopher Hussey, in 1939, called a 'monumental conception' and 'one of the most delightful bits of town planning in London'. (fn. 29) Architectural significance here arises not simply from these intrinsic qualities, but also from the rarity and poor survival of the circus form in London. Around the railed central garden are fifteen of the original twenty-seven houses. The three northern sections were bombed, and nine of the twelve demolished houses have been replaced in pastiche form.

290. Great Percy Street, lower section, looking east to Percy Circus in 1906. Left, Nos 1–13, built 1844–53 (demolished); right, flank of Clerkenwell Police Court, King's Cross Road

291. Nos 19–27 Percy Circus (left to right) in 1939. Entrance to Holford Place between buildings. Demolished

292. Nos 16–18 Percy Circus in 1965. Nos 7–13 Great Percy Street to left. All demolished

293. Nos 4–15 Percy Circus (left to right) in 1937

The genesis of the circus layout is obscure. It was not an early intention of Mylne's, but an irregular crossing was inevitable by 1820 given the convergence of the lines of what became Great Percy Street and Vernon Street (later Vernon Rise and Prideaux Place), the latter determined by a water main from the West Pond. Circuses had seldom been deployed in the development of London estates, though Robert Mylne was projecting a small one at London Spa as early as 1805, an idea sustained by W. C. Mylne until at least 1818, perhaps following S. P. Cockerell's intended half-circus at the west end of Spencer Street (see Survey of London, volume xlvi). (fn. 30) Bath's Royal Circus had failed to generate close metropolitan imitations after George Dance the Younger's America Circus, near Tower Hill, of 1768–74. Dance's own Finsbury Circus, designed in 1802 but not laid out until 1815–17, and Piccadilly Circus, formed in 1819, may have given Mylne more local and contemporary inspiration, but neither of these was as pure in form as Percy Circus. It may also be relevant that Mylne was of Scottish descent; perhaps he cast an eye northwards to Edinburgh New Town, where the Royal Circus was built in 1821–3. There is another possible link, with Royal Circus in Norwood, south London, laid out c. 1826 by John Wilson, possibly the John Wilson who had developed Wilmington Square. (fn. 31)

294. Nos 4–15 Percy Circus, perspective view. R. C. Carpenter, architect, 1841–53

The laying out of Percy Circus did not begin until 1839–40, when circuses were less fashionable. George Mansfield built the southern roadway, and then in April 1841 presented a tender for railing in and planting the whole circus. The northern roadway followed in 1842. In March 1841 R. C. Carpenter, attending the New River Company board as architect to unidentified 'employers', proposed to build the first houses. He was perhaps working for William James Boulton, who wrote to the company on his behalf in 1845. (A solicitor who acted for the Carpenter family in their Lonsdale Square development, Boulton occupied a house in Northampton Square, now No. 12 Sebastian Street, which had previously been Carpenter's uncle Thomas's.) His first scheme for the circus involved a change to Mylne's frontages and was rejected. By May, however, agreement had been reached, subject to Carpenter's elevations being approved by Mylne. (fn. 32)

This was an unusual condition—normally builders simply followed Mylne's elevations—and the implication is that Carpenter himself designed the elevations. Their subtle handling and proportions certainly do not speak of Mylne, whose architectural designs were competent but unimaginative and who, in any case, had by this stage a long-settled formula for houses on the estate. Carpenter, on the other hand, was a young architect of great talent, who at this date was trying his hand at numerous styles. The two men had long known each other, and the resolution of the designs is likely to have been to some degree collaborative. Given the time it took to complete the circus it was certainly Mylne and not Carpenter who saw it through and ensured consistency in the elevations as a whole. (fn. 33)

The initial commitments made in 1841 and 1842 by Carpenter and his builder, Thomas Gates James, were to put up Nos 1–8 and 27. No. 6 was the first house finished, in 1842, but James was bankrupted in November 1843, and Carpenter had evidently left the scene. Nos 7, 8 and 27 were not complete until 1847, James's creditor Elisha Ambler, a Dalston brickmaker, having taken over. In 1846–8 Thomas Pentelow, a carpenter, built Nos 9 and 10. The timber merchant Charles Smyrke had undertaken to build Nos 13–18 in 1841, but he did nothing, and in 1846 Thomas B. Watts of No. 30 Claremont Square gained approval for plans to incorporate a 'respectable public library' on a corner plot (Nos 25–26): this too came to nothing. The turning point came in June 1847 when James Rhodes agreed to build the sixteen outstanding houses as part of his larger commitment to finish the development of the estate. Numerous builders worked under Rhodes to see to it that Percy Circus was completed by 1853, Watkins himself coming back in 1850. (fn. 34)

The following list summarizes the development. (fn. 35)

R. C. Carpenter, architect, with Thomas Gates James, builder:

Nos 1–3. Completed by B. and G. Sheldrick, 1841–5

Nos 4–6. 1841–3

Nos 7, 8. Completed by Elisha Ambler, 1842–3 and 1845–7

Thomas Pentelow, builder:

Nos 9, 10. 1846–8

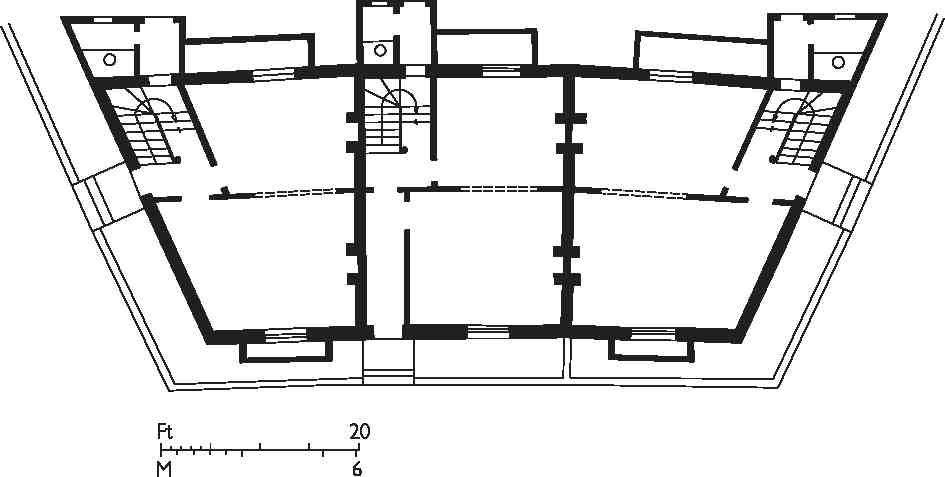

295. Nos 1–3 Percy Circus, reconstructed ground-floor plans

James Rhodes, developer:

No. 11. William Chrystal, builder, 1847–9

No. 12. James Snelling, builder, 1849–51

Nos 13–15. F. Kestevens and Snelling, builders, 1849–53

Nos 16–18. Abraham Riddiford, builder, 1849–52. Demolished

Nos 19–24. William Watkins, George Martin and Snelling, builders, 1850–2. Demolished

Nos 25, 26. James Kent Vote, builder, 1850–1. Demolished

No. 27. T. G. James, builder, completed by Elisha Ambler, 1841–3 and 1846–7. Demolished

Carpenter's elevations of 1841 were carried out with no more than minor modifications. To fit the road layout the twenty-seven houses of Percy Circus were grouped in multiples of three, with three sections of three, one of six and one of twelve. The mid-terrace houses have conventional rear-staircase layouts. Those on corners were given side entrances, in porches except at Nos 1 and 3 (Ill. 295). The best and earliest of these porches survives at No. 4, its quality seemingly reflecting Carpenter's involvement. Return elevations were left largely blind; those on Nos 3 and 4 have been opened up.

The New River Company stuck with large (ten-room) houses on Percy Circus, despite doubts as to whether they could easily be let. In spite of their size and the amenity of the circus these did not attract particularly opulent occupants. The first resident in 1842 was Borchert Brunies, a German 'fancy whalebone worker', who moved to No. 6 from No. 7 Arlington Street. He was permitted to use the premises for his work, which was deemed 'more an Art than a Trade'. (fn. 36) Dr Frederick William Fogarty, a physician and surgeon, was the first occupant of the corner house at No. 15 from 1850, when he built a two-storey surgery and coach-house extension facing Great Percy Street, now remade as a workshop (No. 15). No. 10 was already being used as a lodginghouse in 1851 when No. 9 was also divided, one household being that of an Isle of Wight farmer, Abraham Clarke, whose son, the future architect Thomas Chatfeild Clarke, was that year showing a design for a national sculpture gallery at the Great Exhibition. (fn. 37) Thereafter, the proximity of King's Cross and then St Pancras stations would have been a factor in the gradual spread of lodging-house use.

In 1871 George Palmer, a publisher, lived at No. 6, while No. 19 was occupied by a ladies' underwear maker who employed twelve people on the premises. Antonio Benvenuti, a musician, had No. 23, his lodgers including Alessandro Forelli, a singer, and two Italian priests. No. 15 was occupied by doctors until at least 1910. A plaque still in place on its corner reads 'Bartlett, Surgeon, Accoucheur', suggesting a male midwife, but plausibly a cover for use of the premises for abortions, probably during the early years of the twentieth century. No. 18 then became the New River Company's estate office, and Nos 9–14 and 16 were all in use as apartments or lodgings. (fn. 38) The most celebrated of the lodgers to pass through Percy Circus was Lenin, whose brief stay at No. 16 in 1905 is commemorated by a plaque (see below). In a popular novel of 1891, by J. Maclaren Cobban, No. 10 Percy Circus was made a fictional home for down-at-heel respectability, evoking a communal, even convivial, life for a house full of lodgers who shared a kitchen and occasional meals. The Rev. William Merrydew, unable to afford his rent in Woburn Place, is obliged to step down the social ladder and to come with his daughter into this house. He is introduced by Signor Bottiglia, an 'antique dealer', who explains that Percy Circus 'is not what you say swell, but it is very jolly— very nice; and what a devil does it matter where you have lodging in London? Me, I like Pentonville; it is fresh air; it rise up out of the hole'. (fn. 39)

Nos 19–24 Percy Circus were destroyed by a wartime bomb. Nos 25–27, also damaged, were replaced in 1952–5 by Holford House (see below). Nos 16–18 were demolished in 1968 and replaced in 1970–2 by the rear part of what is now the Travelodge Islington hotel (see page 310), designed by Trehearne & Norman, Preston & Partners, architects. The block facing Percy Circus was, at the request of Islington Borough Council, to have been an 'exact replica' of the demolished buildings. Starkly purple elevations, conspicuously punctuated by vents, sit on channelled stucco lower storeys that, without any street entrance, float disconcertingly behind the area railings. (fn. 40) After half a century's disuse, other than as a car park, the site of Nos 19–24 was redeveloped by Try Homes in 1999–2000, with PRC Fewster designing a speculative block of 27 flats. Nineteen of these flats were designated Nos 16–20 Percy Circus (Ill. 296). The other eight, in a plainer block at No. 9 Vernon Rise, are 'affordable' housing for former council or Peabody Trust tenants. The 'replica' elevation here makes an instructive comparison with that of thirty years earlier at the hotel. The later work is more carefully conceived and more skilfully executed, from the use of yellow stock bricks to the detailing of the architraves, but the copying is so literal and little researched that it extends to the omission of the parapet balustrades. (fn. 41)

296. Nos 16–20 Percy Circus (left to right) in 2005. Try Homes, developers, 1999–2000

Cruikshank Street

Cruikshank Street (misspelled Cruickshank on some street signs and maps) was formerly called Bond Street after one of its builders, and was renamed in 1938 in honour of George Cruikshank's residence near by. Work on this road began in 1822, but formation of the street was left in abeyance until 1838, when the development of Great Percy Street commenced. William Bond, who lived on the corner at No. 17 Claremont Square, then took a 54ft frontage to add to 30 ft he already leased beyond the end of his garden to build four three-storey houses, leaving a carriageway to stables behind. These houses were built in 1840–3 by Henry Johnson of Sekforde Street and survive as Nos 1–4.

By 1842 the street linked through to Holford Square. A further three houses were built opposite in 1843–6, along with five on the east side of Holford Street. These were all built by William Watkins, working under James Rhodes. After bombing in 1941 the site was cleared, Holford Street was realigned and Amwell House was built (see page 231). (fn. 42)

In 1907 the New River Company and Finsbury Borough Council together defeated a London County Council scheme for a school between Great Percy Street and Bond Street (see page 317), it being feared that the intrusion of a school into the 'best residential quarter left in Finsbury' would lower property values. (fn. 43) But the area's residential character had changed, and 'best' did not mean what it once had. In 1909, leases having fallen in, the company took much of the gardens of Nos 12–17 Claremont Square to build five pairs of maisonette flats (now Nos 16–25 Cruikshank Street). A year later four more pairs (Nos 8–15) were built opposite, on the gardens of Nos 75–83 Amwell Street. (fn. 44) The infilling of gardens for the erection of terrace 'houses' designed as flats reflects the New River estate's decline into multi-occupation by this time. Buildings of this nature, common throughout London's Edwardian working-class suburbs, look oddly out of place here, with their plain-tiled roofs and half-timbered gables (Ill. 297).

297. Nos 22–25 Cruikshank Street in 1994. New River Company maisonette flats of 1909

The carriageway east of Nos 1–4 Cruikshank Street has become Holford Mews, at the end of which is the pedimented entrance to a former engineering works, known as Holford Yard, consisting largely of north-light sheds and extending to the back of Nos 91–99 Pentonville Road (Ills 278, 279). The north-west section was built in 1923–5 as Nolan's Garage, and other buildings, replacing stables and outbuildings, were put up between 1928 and 1938 for E. J. L. Delfosse's Ormond Engineering Co. Ltd, manufacturers of screws and radio components. The north-east part was built in 1928–33, the southern part and the fivestorey building at Nos 91–99 Pentonville Road in 1937–8, all to designs by Lewis Solomon & Son, architects, with Henry Kent as builders. (fn. 45)

Sir Frank George Young, biochemist and educationist, was born at No. 2 in 1908, the son of a solicitor's clerk. (fn. 46)

Holford Square

Holford Square existed for just a century. Built up in 1841–8, it was badly bombed in 1941 and wholly destroyed in the post-war reconstruction. This was a fate in contrast to that of Myddelton Square and Percy Circus, the two chief set-pieces of town-planning on the New River Company's estate, which also suffered war-damage. At Holford Square the damage was that much greater. After some attempts at rebuilding, the whole square was demolished and its imprint lost when Bevin Court replaced it in the early 1950s.

298. Holford Square, 1841–8, north-east corner in 1937. No. 30, where Lenin lived, to left of foreground tree. Demolished

The square was named after Charles Holford, Governor of the New River Company from 1815 to 1827, whose family had long been prominent in the company's affairs. Building began on the south side and finished on the north. The first houses, Nos 1 and 2, were built in 1841 by George Bugg, carpenter, of Exmouth Street, and leased respectively to the architect and surveyor James Harrison and the Rev. Elias Parry. Both lived there for some years. Nothing else appeared until 1844, when John Brain, engraver, with Harrison as his 'surveyor', built Nos 11 and 12 at the other end of the south side. No. 12, Brain's own residence, had a 'study' wing at the rear. Harrison also seems to have been responsible for two houses on the east side of the square, for which tenders were published in 1844; these were probably the two at the south corner, Nos 42 and 43. He planned to build more houses on the south side but finally gave up the plots. After this slow start most of the houses followed agreements in 1845 between the New River Company and William Watkins, who was working with James Rhodes. Following Watkins's bankruptcy in 1847 Rhodes quickly saw the project through with other builders, also erecting six further houses in Holford Place in 1848–9. (fn. 47)

The architecture of the square (Ills 298, 299) was conventional for its date, still essentially plain but with stucco decoration to some windows on the first floor, flat heads to all the ground-floor openings, and oblong fanlights over the doors. On the east and west sides the houses were grouped behind palace fronts—a significant departure from usual practice on the estate— with pediments at the slightly projecting ends and centres. The flanks of the end houses, too, were pedimented. The north side, stepping down the slope from east to west, lacked the pediments but otherwise matched; the south side was probably similar. As surveyor to the New River Company, W. C. Mylne was, nominally at any rate, responsible for the design of the buildings or at least their elevations: Watkins was specifically required to build on the north side according to Mylne's plans. The designs are suggestive of a hand other than Mylne's, but whether Harrison or anyone else had any input into the overall design is not known.

299. Holford Square, east side in 1939, with Finsbury Council public bowling green in square. Demolished

Two houses were subsequently built on spare ground at either end of the square, on the north side, where the possibility of laying out link streets to Penton Rise and Pentonville Road was pre-empted by earlier development on the Penton estate. The first was Holford Villa of 1866, the builder's own house and in Christopher Hussey's words 'a last survival of Georgian tradition into the midVictorian jungle'. (fn. 48) It was built by John Dore, who moved there from his house next door at the top of the west side. The second, at the north-east corner, was a vicarage for St Philip's, Granville Square. Firmly in the Victorian manner, this was built in 1870 by Dove brothers, to designs by the architect R. J. Withers (Ill. 298). (fn. 49) In 1937, after the closure of St Philip's, it was turned into flats by the New River Company. (fn. 50)

The central garden, laid out with trees, lawns and flower-beds, was managed by a committee of householders until the expiry of the original ground leases in 1932. It was then acquired by Finsbury Borough Council and laid out as a public bowling green in 1934. (fn. 51)

In its social character, Holford Square underwent the decline from early prosperity common to so much of the New River estate. A number of early and mid- Victorian residents were involved in illustration, engraving and allied crafts: the engraver John Brain (see above); Charles Cheffins, lithographer; William Pope, engraver; Ebenezer Landells, artist and wood engraver; George Belton Moore, artist; Howard Dudley, wood-engraver and illustrator; George Welland, map engraver. (fn. 52) The watch trade was also represented. Among other early residents were Herbert Spencer, in 1847, who moved here (to No. 42) as an unsettled young radical, yet to emerge as a social philosopher, and William Biggar, editor of the Railway Times, recorded here in the 1851 Census. (fn. 53) The mid-Victorian character was mixedly middle-class, with households typically headed by commercial clerks, tradesmen, or professionals. The architect Francis Cranmer Penrose, Surveyor of the Fabric of St Paul's Cathedral since 1852, was living at No. 13 in the early 1860s.

In the early twentieth century Lenin found a temporary home among the lodgings in the square. A later transient was the anti-imperialist historian, Thomas Lionel Hodgkin, who lodged here as a young man in 1936, when he joined the Communist Party. (fn. 54) The square was by this time quite déclassé, a distinctly poor address.

Lenin and the Lenin memorials

In 1902 Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov (Lenin) and his wife, Nadezhda Konstantinovna Krupskaya, came to London, aiming to evade persecution, to publish Iskra, the Russian Marxist newspaper. They stayed in a two-room first-floor flat at No. 30 Holford Square from April 1902 to May 1903. Two years later they returned to the area to lodge at No. 16 Percy Circus, from 25 April to 10 May 1905, when Lenin was one of 38 delegates to the Third Congress of the Russian Social-Democratic Labour Party, held by the Bolsheviks, 'mostly in the backroom of some pub or restaurant', as he later recalled, to hammer out a strategy for the Russian revolution of that year. Other delegates were put up at Nos 9 and 23 Percy Circus. (fn. 55)

Thirty-seven eventful years later Lenin's residence at No. 30 Holford Square was commemorated by a London County Council tablet (not a blue plaque) and a freestanding borough council monument incorporating a portrait bust. The Finsbury Communist Party first proposed a plaque to Lenin in 1939, but the LCC rejected the suggestion as he would not qualify for a blue plaque until 1944, twenty years after his death. Following the Soviet Union's entry into the war in 1941 Alderman Harold Riley and the Finsbury Anglo-Soviet Committee revived the idea, with support from Ivan Maisky, the Soviet Ambassador to Britain. In the new political climate the 20-year rule was overlooked. Unveiled in March 1942, the tablet was placed in a section of rusticated ground-floor wall, all that remained of the recently bombed house at No. 30 (Ill. 300). Maisky stated, wrongly and perhaps opportunistically, that Lenin had stayed on the ground floor, but historical accuracy was of secondary importance to his main theme, that the ceremony 'now would have in it a certain dramatic appeal to public opinion in this country and in mine'. (fn. 56)

300. Unveiling of London County Council tablet, March 1942, commemorating Lenin's residence at No. 30 Holford Square in 1902–3. Ivan Maisky, Soviet Ambassador, at the microphone

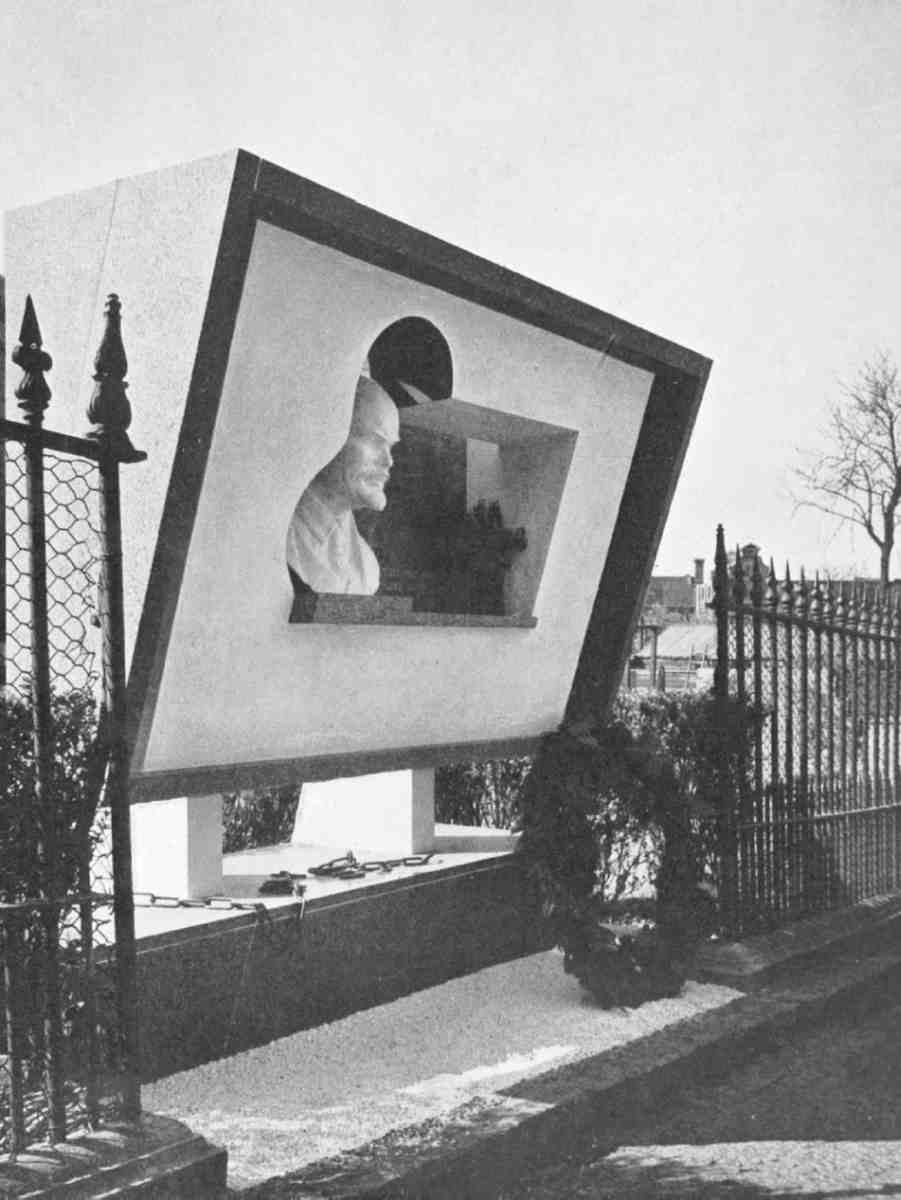

Riley and Finsbury Borough Council had wanted something more permanent, and so commissioned Berthold Lubetkin to design the portrait-bust monument. Unveiled a month later, on Lenin's birthday, 22 April, this stood opposite the remains of No. 30 in a gap in the square's railings (Ill. 301). It was constructed of concrete, marble and granite, with a coloured-glass panel to bathe the head of Lenin in red light, and a broken chain at its base. Within a year the bust had to be replaced, having been defaced by fascist protesters. A police guard was mounted, but when Riley lost control of the council in 1946 it was withdrawn and further attacks were made. Holford Square was cleared in 1948, and in 1951, with the Cold War underway, the tablet and bust were removed to Finsbury Town Hall for storage; the casing of the memorial was consigned to oblivion by its designer in the foundations of Bevin Court, centrepiece of the housing project which was to have been named after Lenin. (fn. 57)

Holford Square and Lenin's memorials there had long been erased when, in 1960, the Finsbury Communist Party again approached the LCC, this time suggesting that there should be a blue plaque on No. 16 Percy Circus. This was agreed and the plaque was mounted in 1962, despite much critical press comment and the New River Company's insistence on an indemnity against consequent damage. This memorial too was short-lived. In August 1968 Nos 16–18 were demolished for redevelopment. The Greater London Council, in keeping with its rules, would not allow the plaque to be installed on the new building, and it was given to the mayor of Moscow. However, the developer of the site, Trevor Burfield of Centremoor Ltd, saw to it that a privately made replacement plaque was incorporated into the new hotel's elevation to Percy Circus. Unveiled in August 1972, in the face of anti-Soviet demonstrations, by the Soviet Ambassador, Mikhail Smirnovsky, standing alongside Burfield, it was immediately covered over again for fear of provoking further trouble. (fn. 58)

301. Lenin Memorial, between railings facing No. 30 Holford Square. Designed by Berthold Lubetkin for Finsbury Council, 1942. Demolished

Peel Centre

The Peel Centre, standing on the site of Holford Square's west side, was built in 1995–6 to designs by Patrick Minns of Gibberd & Minns Ltd, architects, with Charter Construction plc as the main contractors. A community centre with a sports hall, dining-hall, youth club and meeting-room, it continues the work of the Peel Institute, begun in connection with the Quaker meeting-house in Peel Court (see Survey of London, vol. xlvi). Low-slung and brick-faced, the centre has a tripartite layout with a central courtyard. (fn. 59)

Bevin Court, Holford House and Amwell House

The ensemble represented by Bevin Court and its lesser outliers, Holford House and Amwell House, with the space between them (Ills 278, 279), was the last major project masterminded by the architect Berthold Lubetkin for Finsbury Borough Council. Originally known as the Holford Square Housing Scheme, it differs from its predecessors at Spa Green and Priory Green in having been designed and erected in its entirety after the Second World War. Though planning began under the aegis of Tecton, Lubetkin's original practice, the bulk of the work fell to his successor firm of Skinner, Bailey and Lubetkin. Construction took place between 1951 and 1957.

During the war, parts of all four sides of Holford Square suffered damage classified as beyond repair, with destruction worst around the south-west corner. Holford Place, the short access road debouching into that corner, was likewise injured, as was the north side of Percy Circus nearby. In 1943 the freeholders, the New River Company, turned their mind to reconstruction. After investigation, the surveyors Vigers & Co. told Finsbury Council in March 1946 that their clients had concluded that the fabric of the square was irreversibly damaged and that the only policy was to 'scrap the old buildings entirely'. Instead, they proposed blocks of flats round the perimeter 'in the Georgian style in keeping with the general character of the neighbourhood'. (fn. 60) Duly in June of that year the surveyors Daniel Watney & Sons working with Eiloart, Inman and Nunn proposed on the company's behalf to build four-storey blocks of flats on the north, east and south sides. The west side meanwhile had been reserved by the London County Council for a possible extension of Vernon Square School. The scheme was summarily rejected by Finsbury Council, which resolved to buy these sites by compulsory purchase and redevelop the square itself. (fn. 61)

A month later Lubetkin came forward with a plan and Tecton were confirmed as architects. The alacrity suggests that their involvement had been in the air. Having designed the Lenin Memorial attached to the railings on the square's north side in 1942 (Ill. 301), Lubetkin had probably expressed interest in its future. With his usual ambition, the initial project he put forward ran to some seven blocks and adumbrated an enlarged area of redevelopment, including the north sides of Percy Circus and of Great Percy Street west of Holford Street. Bullishly, the council applied for these sites too, but was refused them after a public enquiry at which the New River Company contested the whole order. By March 1947 the compulsory purchase area had shrunk back to the square. The council later bought from the company Nos 25–29 Percy Circus, but was unable to secure No. 15 Great Percy Street. This restricted future access to the development along the line of Holford Place. (fn. 62)

By autumn 1947 Lubetkin was ready to bring forward the matured scheme and full analysis with which Tecton accompanied all their major projects. Their report bestowed faint praise upon the squares of Clerkenwell as 'very characteristic of English town planning' and conveying 'unity of scale and character'. But the architects were against replicating their precise perimeter. A fresh attitude to open space was called for, they argued; density needed to rise to keep down the level of rents, while any north-facing block was bound to be unsatisfactory. (fn. 63)

302. Holford Square redevelopment. Preliminary model with blocks aligned north-south. Tecton, architects, c. 1946

303. Holford Square redevelopment. Portion of model of scheme submitted for tender, looking north; nursery school in front. Tecton, architects, c. 1947–8. Only one of four intended blocks on the south side is shown in this picture, to right

304. Bevin Court, plans of upper floors. Skinner, Bailey and Lubetkin, architects, 1951–4

While developing the scheme, the Tecton team had played with several alternatives, varying from eight-storey blocks around the square to Zeilenbau arrangements with blocks in rigid parallel (Ill. 302). (fn. 64) The solution they now promoted (Ill. 303) was geared to the slope of Holford Square, which dropped some fifteen feet from east to west. There were six blocks altogether: one in four linked parts stepping up and back on the north side, a large slab commanding the crown of the site along the east side, and four squarish blocks in parallel on the south side and along Holford Place. The elevations were to follow the lines of Spa Green, with a chequer of recessed and projecting balcony fronts and vivid colour contrasts. All this was to enclose an urban landscape centred on the old open space of the square, where the Lenin Memorial held potential pride of place amidst 'balustrades, retaining walls, steps and other small architectural features' to cope with the contours. (fn. 65) In respecting this space, the architects were probably heeding the restrictions of the London Squares Preservation Act, 1931.

In retrospect, the architects admitted that this scheme, 'conceived in the immediate post-war years when housing standards were more or less fluid', (fn. 66) represented 'a fairly expensive solution'. (fn. 67) The financial crisis of 1947–8 prevented its progress. But despite the insertion of a nursery school or community centre between the blocks on the square's south side, a review of construction methods in the light of difficulties encountered at Spa Green and Priory Green, and a slight increase in the number of flats from 137 to 143, the scheme described above remained the official one. It went to tender early in 1949, with a ceiling price of £292,670. (fn. 68) The costs then portended caused a radical shift of direction, since 'it was clear that minor economies would not meet the case'. (fn. 69) In July the Finsbury Housing Committee asked the architects, by now Skinner, Bailey and Lubetkin, to revise the project so as to provide flats at substantially lower rentals.

Their first reaction was to pile all the accommodation into a large centrally sited block, offering 'architectural effect by great masses rather than, as previously, by means of intricate and expensive detail'. (fn. 70) This, however, contravened the Act of 1931 and drew objections from the LCC. In September 1949 Skinner, Bailey and Lubetkin came up with the basis of what was built. The bulk of the housing now occupied a 'large 3-winged block' of 112 flats, later raised to 118, with fourteen extra dwellings sited separately and the open space to the west of the main block. At first the LCC's Town Planning Department feared that this would hinder redevelopment of the adjoining areas, but the architects managed to persuade them of the new layout's merits. (fn. 71) The full scheme received outline approval from Finsbury in January 1950 and was worked up during the course of that year.

Bevin Court. Skinner, Bailey and Lubetkin, architects, 1951–4

305. Garden (west) front in 2006

306. Mural in lobby, with emblems of Finsbury Council. Peter Yates, artist, c. 1954

307. Entrance (south-east) front in 2006

308. Entrance porch in 2007.

309. Rear (north-east) front in 2007 showing galleries to flats

The revised concept depended for both blocks on a repetitive bay-module of 10 ft 3in. throughout, permitting the possibility of prefabrication. To avoid monotony, explained the architects, the windows 'are grouped in couples with the solid spaces between filled in with precast concrete elements of standard size, whilst the horizontal bands on the elevation are obtained by carrying the floor slabs out to the surface of the wall and facing them with precast concrete units'. (fn. 72) In the Y-shaped block— the future Bevin Court—they economized by focusing on a single grand staircase hall with two lifts, from which tenants reached their flats along galleries (Ill. 304). To compensate for this mode of access ('not a popular solution'), (fn. 73) all living-rooms and bedrooms faced away from the common galleries. The south-western wing, containing mostly maisonettes, was separately planned, while the small independent block at the end of Holford Place was likewise devoted to maisonettes.

As for the former square, the LCC accepted its division into separate portions, as entailed by the siting of the main block, so long as it remained a public open space. The architects explained the change as one from space 'as a concrete volume inscribed within the surrounding buildings', to 'a system of air-reservoirs contained between points of emphasis'. (fn. 74) Holford Place now shrank to a footpath, so that vehicle access had to be from Holford Street or Cruikshank Street alone.

This scheme went out to tender in autumn 1950. After some economies Tersons began work on the basis of a reduced sum of £212,041 the following spring. (fn. 75) The choice of contractor was bound up with the engineering arrangements and structural system. Hitherto Lubetkin had regularly worked with Ove Arup and the specialist concrete contractors, J. L. Kier. But frictions and differences had arisen recently at Spa Green and Priory Green, some personal, some due to the novelty of the box-frame structural system (see page 102). The architects therefore argued for a construction process undertaken by a single contractor rather than a general builder with a concrete subcontractor, claiming that this suited post-war conditions and avoided duplication on site. The firms tendering were asked to submit separate bids for framed construction, both in situ and prefabricated, as well as for cross-wall and slab. (fn. 76) In the event, prefabricating any more than the cladding proved too costly, so the cross-wall option offered by Tersons was chosen. Working out Bevin House's structure took place between Skinner, Bailey and Lubetkin and Tersons' consulting engineers, J. H. Coombs & Partners. Absalom Green was the job architect for the scheme, as he had been at Priory Green.

310. Holford House, view from Great Percy Street. Skinner, Bailey and Lubetkin, architects, 1951–4

Shortages of supplies and unreliable deliveries, particularly of steel and cladding panels, hampered the contract. Atlas Stone, for instance, agreed to supply the concrete cladding but withdrew in May 1952 'on the ground of more urgent defence orders'. This was serious, since on the end walls the cladding was to act as permanent shuttering for the structure. An alternative supplier, F. Bradford & Co., could supply only rough-faced cladding which, the architects thought, 'could not fail to give a somewhat drab effect'. (fn. 77) Permission was therefore given to add a special white aggregate of Hopton Wood stone chippings to Bradford's panels on four of the six elevations of the Y-shaped block, in distinction to the exposed ballast used on the end walls and gallery sides. Now that most of the concrete has been painted over, these contrasts cannot be seen.

Show flats were ready by the summer of 1953, and the name Bevin House, in memory of the trade unionist and statesman Ernest Bevin, was allotted to the main block that autumn. When the Lenin Memorial was removed from Holford Square in 1951, the architects and many socialists had assumed that the building would be called after Lenin, and a place for it next to the entrance had been reserved. But as Communist support dwindled locally and nationally, Finsbury's ruling Labour group deemed this impolitic. According to Francis Skinner, 'when it came to redesigning the sign over the entry porch, we only had to change two letters'. (fn. 78) At the same time the small maisonette block took the name Holford House. At an opening ceremony held on 24 April 1954, Dame Florence Bevin unveiled a bust and tablet; Arthur Deakin, the anticommunist general secretary of Bevin's former powerbase, the Transport and General Workers Union, also spoke. (fn. 79)

Bevin Court testifies to Berthold Lubetkin's post-war resilience in designing public housing. (fn. 80) Tecton's point of departure for their previous Finsbury estates had been the strict orientation and parallelism of Zeilenbau planning, though they had tried to relieve its rigidity with variation, colour and movement. Much effort had been spent on improving the internal planning and facilities of the flats, and on the construction process. Setbacks in building Spa Green and Priory Green, coupled with the difficulties of the post-war economy and building industry, caused Lubetkin to retrench but not to relinquish his belief in public housing as suitable for monumental expression. Self-sufficient and forcefully geometrical, Bevin Court became the prototype for a new type of multi-storey block which Skinner, Bailey and Lubetkin took on in its work for the borough of Bethnal Green in the 1950s. This later idiom of Lubetkin's develops the strong geometrical impulse always evident in his work, stemming from his exposure to Russian Constructivism. For the heavier concrete forms the post-war work of Le Corbusier is sufficient explanation.

With its 120-degree wings and its focus upon the centre, Bevin Court has a strong 'panoptical' flavour (Ills 305, 307). Y-shaped plans can occasionally be found in nineteenth-century prison and hospital plans, and had featured in Lubetkin's early student projects, but so far as is known no housing of this scale had been built in such a form. The scheme predates by some months Zehrfuss and Breuer's successful competition design for the Y-shaped Unesco secretariat in Paris, to which it bears some formal similarities. Proportionally, the wings dominate the centre. Seven storeys in the south-east, eight on the other two sides, they are some 160 ft long but less than 30 ft deep. On the inner end of each wing, successors to the drying canopies of Spa Green are half-visible on the roof. Liveliness of pattern on the flat fronts of the main elevations is contrived by setting concrete panels against brick spandrels below the windows, and alternating the arrangement of the flats on each floor. Now that most of the concrete on Bevin Court has been painted over, the texture, colour and articulation of the panels, each made up of small units, have largely been lost. The access balconies are gathered on the northeast flank, which forms a true 'back' to the building (Ill. 309). Here plain brick fronts are screened by concrete cantilevered balconies whose uprights once again alternate in position on each storey.

The tour de force at Bevin Court is the sequence of main hall and central staircase, still publicly visible at the time of writing. From a projecting concrete porch, heftily modelled and lit from a fanlight under an oversailing reverse-pitch roof (Ill. 308), the visitor enters a truncated drum, expressed externally in brickwork. Set back within one side of the curve, in space originally meant for a porter's lodge, is a Guernica-style mural in primary colours by Peter Yates, who had been an assistant with Lubetkin at Peterlee; it depicts emblems connected with Finsbury's history and heraldry (Ill. 306). The exact date of its appearance seems unrecorded, but it was not remarked on at the time of the opening. Geometry and scale expand as the visitor moves into the space at the heart of the building. This is an equilateral triangle in plan, cut off at the corners so as to form a hexagon, with open balconies on the short sides of the upper storeys. Two lifts and the common rubbish chutes also share the edges of this space. In its centre, within a circular well twenty feet in diameter, is inscribed the staircase (Ills 311–13). Replicating the building in plan-form, it consists of a sequence of short flights at 120-degree angles with triangular, island-like landings halfway between the floors, poised on a single central pillar. The flights always turn to the right from the half-landing, then take a dog-leg from the floor above up to the next half-landing. The main materials of the staircase and its drum are concrete, with steel rails and a mahogany handrail. Though simple in conception, it has great spatial dynamism. Such communal stairs were further explored in Skinner, Bailey and Lubetkin's late work for Bethnal Green, if never with the same force as at Bevin Court.

311. Bevin Court staircase, during construction, c. 1952

312. Bevin Court, base of stair in 2007

Holford House (Ill. 310), visually quite separate at the join between Percy Circus and Great Percy Street, has none of the drama of Bevin Court. It is a plain four-storey maisonette block with the south end cranked back towards Great Percy Street from the former line of Holford Place. The language is the same as that of the larger block, but the use of concrete and brick for the facing and spandrel panels is inverted. Here the original concrete surfaces remain unpainted.

313. Bevin Court staircase in 2004

The environs of Bevin Court are the only place where the landscaping still bears traces of Lubetkin's intentions for his Finsbury estates. The formal approach from Holford Street takes the form of a simple circle within lawns, dignified and animated by the descending contours. The north-east or back side was reserved largely for children's play and has now been much altered. To the west, a sinuous ramp with dwarf walls partly of concrete and partly of cast-iron trellis takes residents down to the main area destined for garden use. A boundary fence now cuts off Bevin Court from the smaller garden of Holford House, and the pathways have correspondingly changed.

One later addition was made to this scheme. That is Amwell House, the two-storey block at the south-east angle of Cruikshank Street and Holford Street. A building of twelve small flats with bed-sitting rooms, it was allotted to Skinner, Bailey and Lubetkin by Finsbury Council in 1956 and built in 1957–8 by James Webb & Son. (fn. 81) It is remarkable only for its run of west-facing bay windows, otherwise untypical of the architects.