Survey of London: Volume 46, South and East Clerkenwell. Originally published by London County Council, London, 2008.

This free content was digitised by double rekeying. All rights reserved.

'Charterhouse Square area: Charterhouse Street and other streets', in Survey of London: Volume 46, South and East Clerkenwell, ed. Philip Temple (London, 2008), British History Online https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vol46/pp265-279 [accessed 15 April 2025].

'Charterhouse Square area: Charterhouse Street and other streets', in Survey of London: Volume 46, South and East Clerkenwell. Edited by Philip Temple (London, 2008), British History Online, accessed April 15, 2025, https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vol46/pp265-279.

"Charterhouse Square area: Charterhouse Street and other streets". Survey of London: Volume 46, South and East Clerkenwell. Ed. Philip Temple (London, 2008), British History Online. Web. 15 April 2025. https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vol46/pp265-279.

In this section

Charterhouse Street (east of Smithfield Market)

Before 1869, the one connection between the Smithfield and St John Street area and the Charterhouse was an ancient street called Charterhouse Lane. In the seventeenth century this street consisted of a narrow alley which started from the east side of the open space at the bottom of St John Street, then widened a little and swung northwards on a straight line to the gate that protected Charterhouse Yard. The opening-out of the western section when the new Smithfield Market was built in the 1860s destroyed the old lane's integrity. Less than half its former length remained, renamed as part of the otherwise entirely new Charterhouse Street.

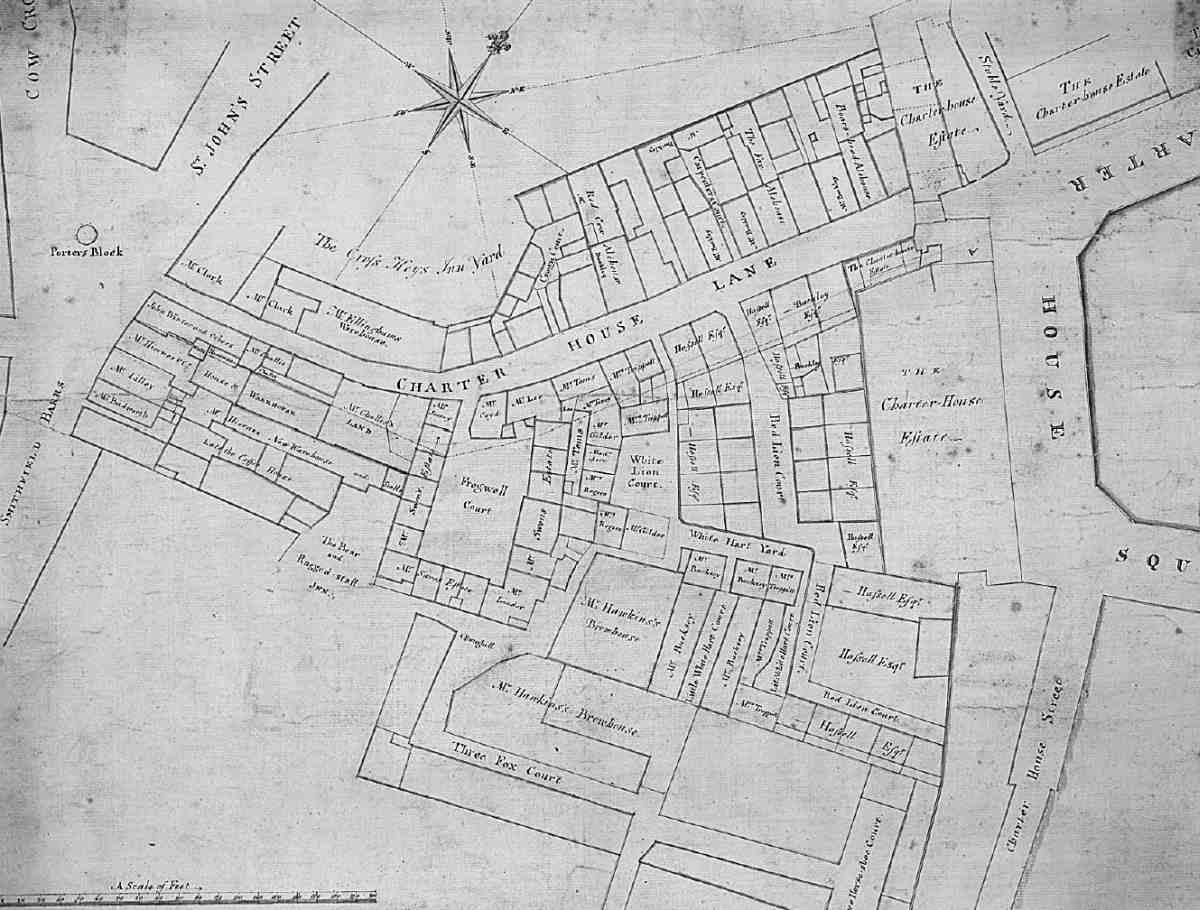

366. Charterhouse Lane and surroundings. Extract from a map of 1718

The earliest records of Charterhouse Lane go back to the late fifteenth century, and twenty-four tenements were recorded there in 1539–40. (fn. 1) Pre- and post-Reformation tenants depended on the Charterhouse for the use of its excess water which ran down the lane. (fn. 2) There was already one large yard off the south side, called Froggeswell, Frogwell or Fogwell Court. As property ownership fragmented after the Dissolution, the density increased. Since the vicinity was outside City jurisdiction it became raffish and unruly. In 1611–12 alone several incidents concerning Charterhouse Lane came before the Middlesex sessions, including threats of violence, victualling without licence, and keeping 'a house of lewd report'. One resident was accused of 'harbouring a great bellied whore, and as soon as she was delivered of two children in his house, he suffered her to run away with them in her lap to bury them in a dunghill at Bunhill'. (fn. 3) In the late 1620s Charterhouse Lane was one of the streets singled out by magistrates as dens of open prostitution. (fn. 4)

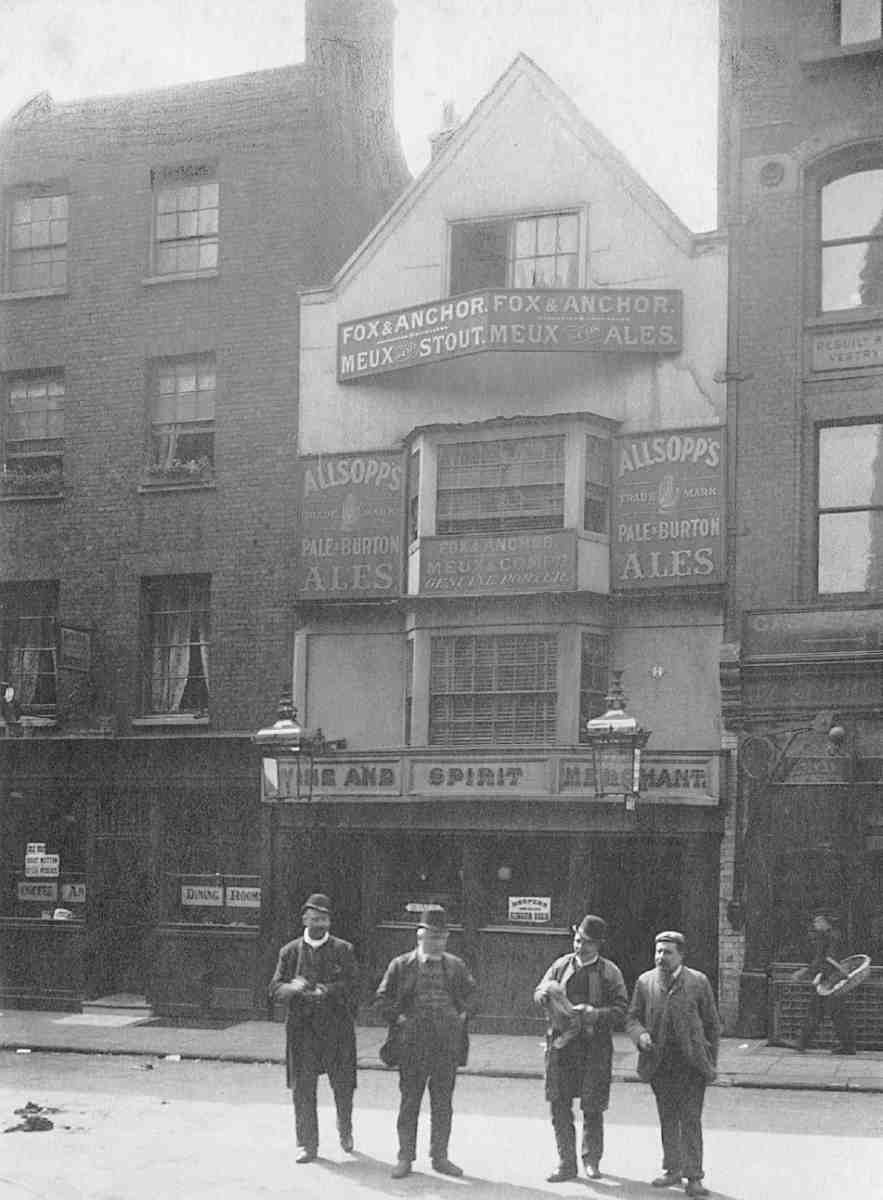

Taverns proliferated hereabouts. Names noted between 1660 and 1751 include the Bricklayer, Feathers, Woolsack, Red Lion, Red Cow, Red Lettice, Flying Horse, Boar's Head, Rose and Crown, Fox and Anchor, Cat and Fiddle, Sun, Moon and Duke William. (fn. 5) The Fox and Anchor now at No. 115 is descended from a pub so named by 1756 and previously known as the Rose and Crown and the Blue Anchor. (fn. 6) Its seventeenth-century predecessor was deemed worthy of recording as one of the last reminders of the street's antiquity before its demolition in 1897 (Ill. 370). By the early eighteenth century the courts on the south side had increased to three, Frogwell, White Lion and Red Lion Courts; there were less extensive ones opposite. No particular trades appear to have predominated, but a map of 1718 shows warehouses, so named, making an appearance at the west end of the lane (Ill. 366).

On the north side, where St Bartholomew's Hospital owned properties, some rebuilding took place at the west end around 1752. (fn. 7) It fell to St Sepulchre's Vestry, within whose jurisdiction Charterhouse Lane came, to do more. The parish promoted an abortive improvement bill for widening the lane in 1764. In the next decade they were more successful, and in 1775 improvement commissioners purchased eleven houses for demolition on the south side along with Frogwell Court, several then in the hands of distillers. (fn. 8) The old Charterhouse gateway was also removed, and new houses were built along the northern frontage. Of the five erected on Charterhouse property next to the gate in 1786–7 (see page 260) two were numbered in the lane, on the site of the present Nos 121 and 123 Charterhouse Street; the surviving lease of one of them was to Daniel Pinder and William Norris, masons. (fn. 9) No. 119, the oldest house now surviving here, appears to be of similar date.

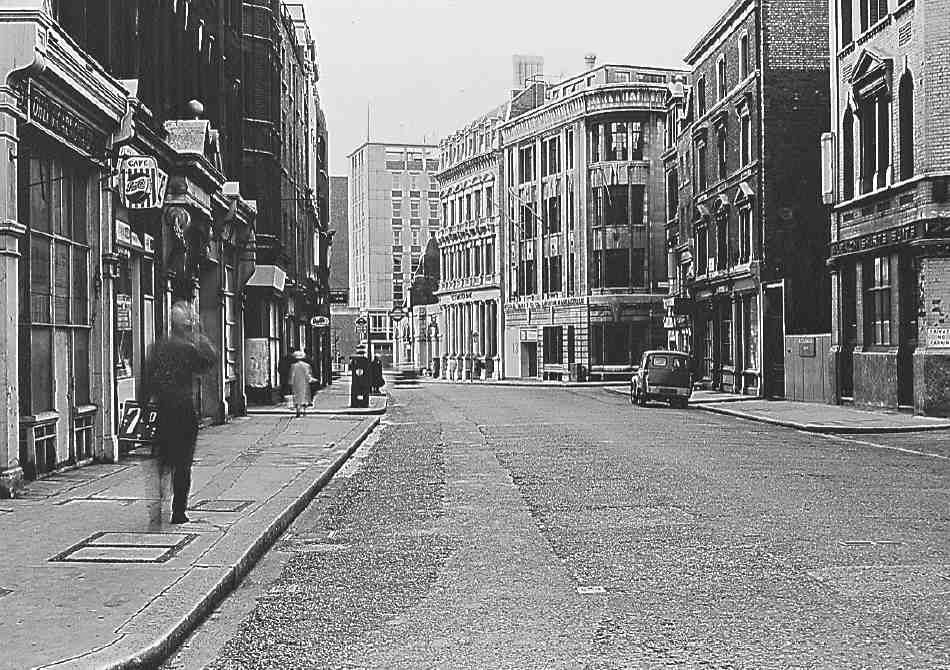

367. Charterhouse Street, looking east towards the Charterhouse, 2006; Nos 38–42 in centre

The City's redevelopment of Smithfield Market on a cleared site north of the previous open market area had a drastic effect on Charterhouse Lane, involving the demolition of most of the south side and the opening-up of two-thirds of its length towards the market. In 1869–70, with the new market building complete, it was resolved to take the new road along the north side of the market further east into the square itself, carried out in 1873–4. The road was called Charterhouse Street, apparently at the suggestion of the Charterhouse, on the grounds that there was 'one Charterhouse-street already in existence, but it is a small and unimportant street, and a new name [Hayne Street] has been suggested for it'. (fn. 10) The name Charterhouse Street was applied both to the eastward extension into the square and to the remnant of Charterhouse Lane, which name was formally abolished in 1869. But Charterhouse Lane continued in informal use as a name until 1881, when the whole length of Charterhouse Street was sequentially numbered and the present Nos 89–123 (odd) were assigned to addresses formerly in the lane. The remnant of ground at the angle between the old and new roads was laid out for a small block of buildings and allotted the numbers 38–42 (even) Charterhouse Street, behind which a tiny street, Fox and Knot Street, was cut through in 1871. The name was taken from Fox and Knot Yard, a court obliterated by the new market.

The effect of these changes was immediate. Whereas in 1860 Charterhouse Lane enjoyed a mix of businesses, in 1876 half of the sixteen surviving houses were occupied by meat and poultry traders. The same trades dominated the new buildings put up, though there were also coffeerooms to rival the two remaining pubs and a large bank at the corner with St John Street. By the time of the Second World War most of the buildings west of the Fox and Anchor at No. 115 were purpose-built cold stores. Only with the decline of Smithfield Market did the grip of the meat trades loosen. Today restaurants and bars have largely supplanted them.

The small triangular block west of Fox and Knot Street (Ill. 367) just within the City boundary, belongs to the land acquired by the Corporation of London in the 1860s for the Smithfield Market development. Set out for building in 1871–2, it remained empty until 1875–6. At the apex a warehouse (No. 38), was then built for Myer and Nathan Salaman, ostrich-feather merchants, to designs by Benjamin Tabberer. (fn. 11) It is four storeys high, of red brick with regular fenestration; all the ornamentation is concentrated on the narrow corner. For many years there were coffee-rooms here. The less eligible eastern portion (Nos 40–42) consisted originally of a mission school building with commercial premises on the ground floor, designed by Habershon & Pite and built by Matthew Allen & Son for the trustees of the Fox and Knot charity schools. (fn. 12) The site was redeveloped in 1956 for R. F. Garnham & Son, meat salesmen, with the current Nos 40–42, Lindsey House, a four-storey purplish-brick building to the designs of Gerald Shenstone & Partners. (fn. 13)

368. Nos 111–113 Charterhouse Street. Elevation by A. H. Mackmurdo, architect, c. 1900

Nos 91–93. This site appears not to have been rebuilt with the extension of Charterhouse Street in the 1870s, when maps show an irregular frontage occupied by a distillery. The present six-storey neo-Georgian block, now known as Boundary House, was erected speculatively in 1930–1 by E. D. Winn & Son to the designs of H. Percy Monkton. (fn. 14) Steel-framed and brick-clad, it is given vertical emphasis by pilasters and higher wings. The style has residually Egyptian touches. In its early years the building housed the wholesale meat department of the London Co-operative Society, while there were commercial dining-rooms on part of the ground floor and offices above.

No. 99 is an office block designed by Newman Levinson & Partners, architects, for Glengate Properties, and completed in 1983. (fn. 15) Its brick front is marked by tiers of projecting windows with bronzed spandrel panels.

No. 105. This site was that of a long-lived pub, the Red Cow, which had existed since at least 1751. As a plaque on the front reveals, it was rebuilt under that name by J. H. Schrader in 1871. The builder was Thomas Elkington. (fn. 16) Remnants of the pub front survive, with cows' heads at the two ends. The Red Cow continued until the early 1950s, when it became the Smithfield Tavern; it is currently the Wicked Wolf.

No. 107 is a building of minimal character. It underwent reconstruction or major refurbishment in 1973 for Guardian Properties, but its plain brick front appears to be later.

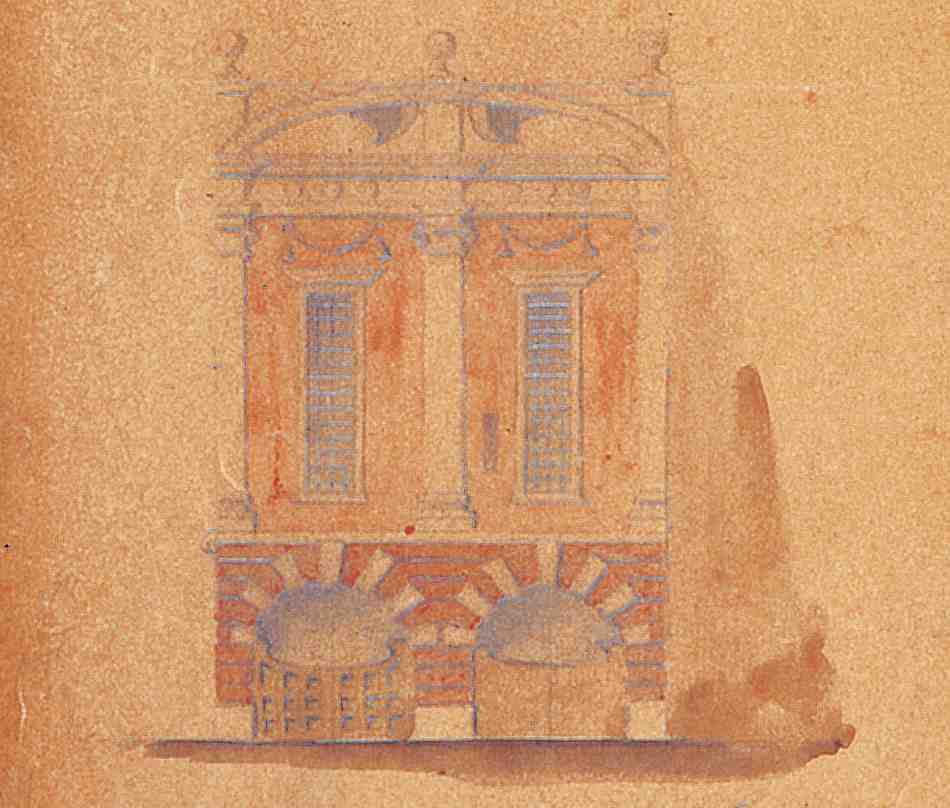

Nos 109–113. The bold-scaled Wrenaissance frontage to this building is the modified remnant of a cold-storage warehouse of 1900, conceived by the maverick architect designer A. H. Mackmurdo, who was working at the time with Latham Withall, architect of the newly rebuilt Fox and Anchor next door. (fn. 17) Mackmurdo's clients were the meat-traders John Palmer & Co., who had occupied premises in Charterhouse Street since about 1880. (fn. 18)

369. Nos 109–113 Charterhouse Street. Elevation before 1921 (left), showing original front at Nos 111–113 and addition of 1907 at No. 109. Elevation in 2001 (right)

Of rubbed red brick, with dressings of stucco and Portland stone, the façade incorporates rustication, giant pilasters and elongated windows—features frequent in Mackmurdo's oeuvre. But the existing elevation is not as built. The original design covered only the centre and right-hand bays of the frontage at Nos 111–113 and was topped by a segmental pediment surmounted by three ball finials (Ill. 368). An extra left-hand bay with a flat cornice appears to have been added on the site of the former No. 109 by Francis E. Jones, architect, in 1907, leaving the front asymmetrical. (fn. 19) Symmetry was achieved only in 1921, when a new cooling plant was added on the roof, and the present upswept parapet constructed to conceal it (Ill. 369), to whose design is not known. The result was to impose a sleeker, more Wren-like feeling upon a front previously more robust and vernacular in spirit. The cold store behind was demolished in 1988–9. Mackmurdo's modified façade was retained and incorporated as the entrance feature of a large office development by IKA Project Design & Management. (fn. 20)

370. Fox and Anchor, No. 115 Charterhouse Street, before 1897. Demolished

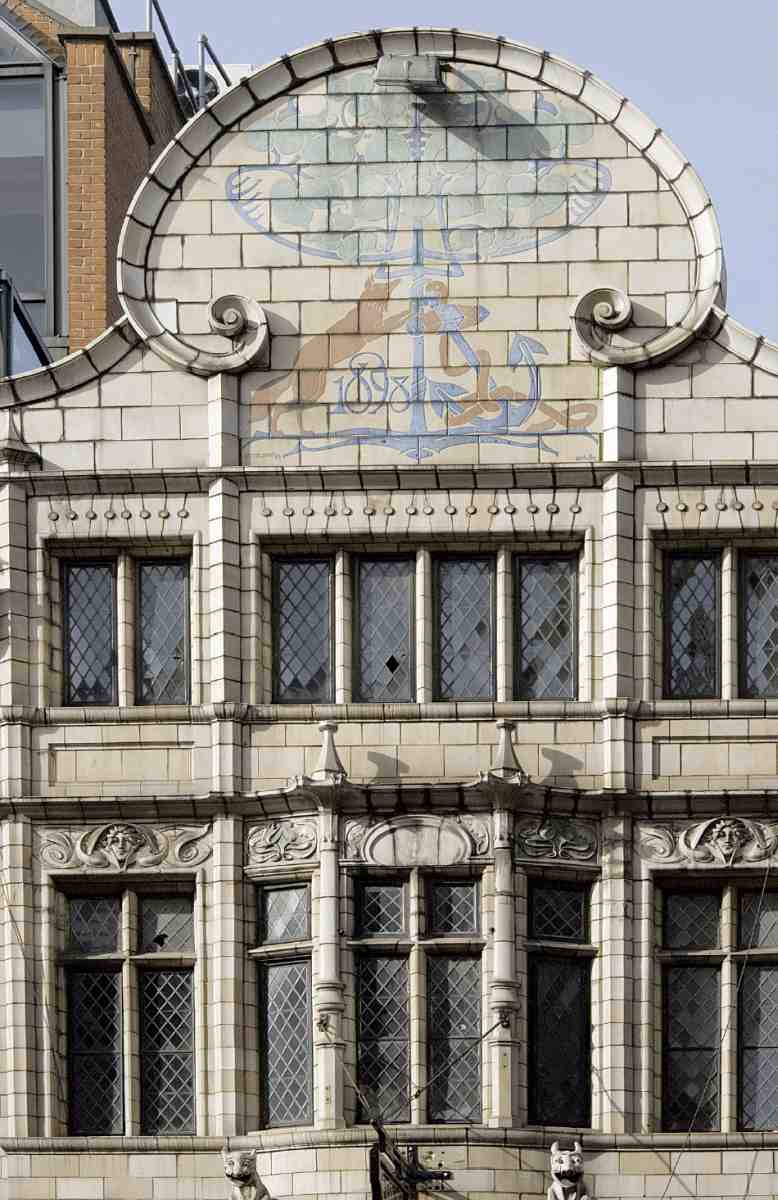

No. 115, the Fox and Anchor. This colourful public house replaced the previous long-lived hostelry of the same name in 1897–8 (Ills 370–372). (fn. 21) Its polychromatic facade in Doulton's Carraraware is an exuberant example of the work of W. J. Neatby, the designer, painter and ceramic modeller best-known for his Harrods Food Hall of 1902. (fn. 22) With the exception of Neatby's façade, the building was designed by Latham A. Withall, a City architect experienced with pubs; the contractors were W. H. Lascelles & Co., specialists in shopfitting. At the time of the rebuilding the pub was sub-let by the brewers Meux & Co. to the victuallers Roberts Brothers, who also ran a cigar-store next door at No. 117. During their tenure an opening was made between the two premises to create an extensive first-floor dining-room. (fn. 23)

Neatby's front dates from his period as head of Doulton's architectural decoration department, when he was developing the art possibilities of Carraraware. The façade exhibits a carefree yet disciplined balance of Queen Anne and Tudor elements, set off by two projecting beasts, plentiful relief sculpture and a charmingly painted gable. Other than the intrusion of a modern facia, the frontage has survived well. Some tilework remains in the interior, which was most recently refurbished in 1992. The pub is closed at the time of writing. (fn. 24)

No. 117 is a two-bay building of austere character, with the windows on the main upper floors set back in deep reveals. It was built in 1874 as a vestry room and parish offices for St Sepulchre's parish, with commercial premises in front and above. The architect was Lewis H. Isaacs, and the builder Thomas Elkington. (fn. 25) The site had been in the ownership of St Sepulchre's Vestry since 1616 and the previous building dated from about 1651. (fn. 26) Isaacs, the Vestry's architect, also produced plans for a parish school here but these were set aside as too expensive. (fn. 27) The Vestry's accommodation consisted of a top-lit room at the rear with separate access. The leasing of the upper floors was not at first successful. After 1900 most of the occupants were connected with the meat trades. (fn. 28)

No. 119 is a plain brick mid-Georgian house probably dating from the early 1780s, when the north side of Charterhouse Lane was being set back. The interior is largely featureless apart from the stair in the conventional position at the back. Conspicuous on the front are ornamental iron tie-plates; the date given is 1855 and the initials appear to be those of Charles William Wilbraham, general warehouseman, who occupied the premises around that date. (fn. 29)

371, 372. Fox and Anchor, No. 115 Charterhouse Street, in 2006. Details of Doulton's Carraraware by W. J. Neatby, 1897–8, on upper façade and (below) in entrance

Nos 121–123. This tall, red-brick and stone building was originally a warehouse, erected in 1907 by the proprietors of the nearby Charterhouse Hotel as a storage facility for the many commercial travellers among their clientele. The site had already been occupied by Wheeler and Warren, the developers of the hotel. Construction work was undertaken on their behalf by the builders Thompson & Beveridge. (fn. 30) By about 1913 the upper floors had been partly converted to bed-sitting rooms for hotel staff. But in the 1920s, after the Charterhouse Hotel went out of existence, the building was taken over by the meat trades for cold storage and other uses. (fn. 31) The building shares something of the hotel's style and was possibly designed by the same architect, Edward Haslehurst. But this is the plainer building, of five storeys in brick with tightly packed windows and minimal relief in the form of glazed brick jambs to the arched doorways and a curved stone parapet.

Carthusian Street

The two sides of Carthusian Street have different characters today, corresponding to their different histories. The north side retains small shops with offices or flats above, and a pub (Ill. 374). The south side is dominated by office blocks. The latter belongs to the City but is covered here for the sake of completeness. In the late Middle Ages the street was a narrow, gated outlet from the Charterhouse to Aldersgate Street. The gatehouse was probably replaced by plain gates halfway down the street in the first of two road-widenings, around 1700 (when the name Carthusian Street or Lane was already current); the second, adding a full fifteen feet to the width and entailing rebuildings on both sides, took place around 1820. After several replacements and shifts of position, the gates finally disappeared in 1874. The street was wood-paved by the following decade, no doubt to deaden the noise of heavy carts rumbling between Aldersgate Street and Smithfield. (fn. 32)

North side

Apart from some buildings at the Aldersgate Street end, the north side is shown as blank on Ogilby & Morgan's map (Ill. 333). It was filled up in the late 1690s when, in conjunction with his houses at Nos 1 and 2 Charterhouse Square, William Desborough built along the north side of Carthusian Street and round into Aldersgate Street, setting back the frontage by a few feet in the process. (fn. 33) In 1800 these buildings were the freehold property of the Earl of Dartmouth. They comprised a pastrycook's shop at the Aldersgate Street corner, a bakehouse and stables in a yard to the rear, and eight three-storey houses with shops along Carthusian Street (Ill. 373). (fn. 34)

In 1800 the governors of the Charterhouse bought No. 1 Charterhouse Square, with the intention of roadwidening. That finally took place in 1820, when the Charterhouse and the Corporation of the Sons of the Clergy, owners of the property opposite, employed James Humphreys, victualler, to widen Carthusian Street. Humphreys subsequently built two shallow rows of modest stock-brick houses on the north side. (fn. 35) The plain façades of two of them, built in 1821, survive as Nos 7 and 8, but their interiors were reconstructed in 1997–8. (fn. 36)

Of the other buildings on the north side, No. 1 was rebuilt by a Mr Stockwell, of City Road, for H. E. Beddington in 1883, along with No. 129 Aldersgate Street next door, in hard red brick with minimal stone dressings and shaped dormers next to the corner. (fn. 37) Nos 2–5 are a plainish block of flats over shops with rendered ends and a brick centre to the front, designed by the A & Q Partnership for Berkeley Homes and erected in 1997–9. (fn. 38) No. 6, the Sutton Arms (Ill. 375), was rebuilt in the robust pub style of 1898 for the New City of London Brewery Co., by the builders Courtney & Fairbairn of Albany Road. (fn. 39) It is well preserved. The upper storeys, of red brick with plentiful stone dressings, rise to a pair of shaped gables.

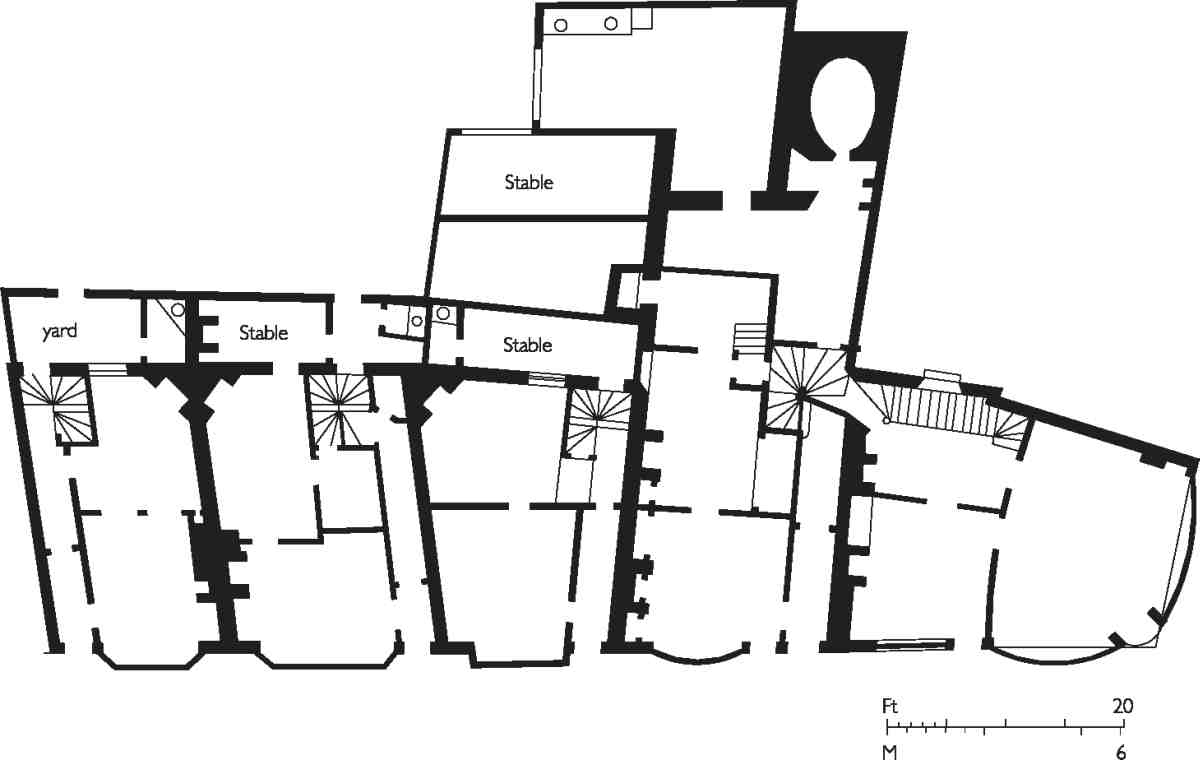

373. Nos 1–7 Carthusian Street, plans of houses and shops in 1819, shortly before demolition

374. Carthusian Street, north side looking west from Aldersgate Street in 2006

South side

Traces of development on Carthusian Street's south side have been found going back to the thirteenth century. (fn. 40) By 1700 it was dominated by the flank of the Red Lion inn, a large courtyard inn entered from Aldersgate Street and reported in 1720 as enjoying 'a pretty good trade' (Ill. 376). (fn. 41) The inn was owned from this time onwards by the Sons of the Clergy. (fn. 42) Westwards lay the entrance to the separate, ramifying Red Lion Yard. Probably to the west of that was the charity school belonging to St Botolph without Aldersgate reported here in 1708. (fn. 43)

The flank of the Red Lion, perhaps along with the rest of the inn, was rebuilt as part of the road-widening of 1820 undertaken jointly by the Sons of the Clergy and the Charterhouse. As opposite, the entrepreneur was James Humphreys, victualler, but the building work was done by Joseph Warren, bricklayer, Thomas Chandler, carpenter, and Matthew Elwall, plumber. (fn. 44) These houses, at Nos 9–17, were replaced in 1885–6 by a block of four-storey warehouses, reflecting the commercial transformation of the area. This was a speculation undertaken by the railway solicitor and prominent Wesleyan, Robert William Perks; his architect was George Vickery and his builder John Allen & Sons. (fn. 45) By then, following the extension of the Metropolitan Railway from Farringdon to Moorgate, the Red Lion had lost most of its back land and been reconstituted on a much smaller scale at the corner with Aldersgate Street.

375. Sutton Arms, No. 6 Carthusian Street, in 2006

At the back between Perks's buildings and the railway a large warehouse had been built in 1873–4 by Michael Nairn & Co., Kirkcaldy-based floorcloth manufacturers, with its entrance from Aldersgate Street. (fn. 46) Seeking a frontage on to Carthusian Street, this company in 1924–5 negotiated the purchase of Nos 9–17 and the Red Lion from the Sons of the Clergy. (fn. 47) Wheat & Luker, architects, with G. E. Wallis & Sons as builders, reconstructed Nos 14–17 in 1927–8 as new offices and showrooms for Nairns, and designed a matching new frontage to No. 131 Aldersgate Street. (fn. 48) The new street elevation was at first interrupted by the Red Lion on the corner at No. 130 Aldersgate Street, but in 1936 Nairns were able to demolish the pub and unite the two fronts. Wheat & Luker's successors, George E. & K. G. Withers, carried out the work, seamlessly joining the two blocks with a curved corner (Ills 377, 378). (fn. 49) The four-storey classical façades to the whole are in fine ashlar, with the vertical proportions and Egyptian-style cavetto cornice then popular. Small venti lation grilles are incorporated into the elevations in a curious and conspicuous manner.

376. Red Lion inn and yards, Aldersgate Street, plan in 1794. Demolished

The remaining warehouses on the south side of Carthusian Street were demolished to make way in 1988–9 for the current Nos 9–13, the Chamber of Shipping, a costly office block with flats above built by Ashby & Horner to the designs of Ronald Ward & Partners. It was built in the historicizing style latterly favoured by these architects, using various materials for the front including copious herringbone brickwork in panels under the windows and Portland stone. (fn. 50) In the open vestibule is a foundation stone and the cast-iron sign from the Chamber's previous building.

Aldersgate Street and Goswell Road

This section covers the addresses Nos 106–134 (consec.) Aldersgate Street and Nos 3–25 (odd) Goswell Road—a small portion of a thoroughfare formerly one of the main northward routes out of the City. Today the eye is drawn to the heroic post-war developments of the Barbican and Golden Lane Estate that skirt the opposite frontage of this stretch of road. Its western side is marked by a miscellany of office blocks, flats, a hotel and small shops built at sundry dates over the past two centuries, but mostly during the past fifty years.

The division between Aldersgate Street and Goswell Road corresponds to the boundary between the City and the modern London Borough of Islington, and was formerly the site of Aldersgate Bars, but no break is now palpable at this point. The City boundary runs from Carthusian Street up the centre of the road, so that apart from Nos 129–134 Aldersgate Street none of the properties mentioned in this section was ever under City jurisdiction. The whole of the land on the west side north of Carthusian Street lay within the precincts of the Charterhouse, and was probably not much built upon before the Dissolution.

Originally the name Aldersgate Street applied only to the portion of that road from Aldersgate itself (sited close to St Botolph without Aldersgate) as far north as Long Lane. The stretch of the road northwards from Long Lane to Aldersgate Bars and the start of Goswell Street (after 1864 Goswell Road) was formerly called Pickax Street. This name perhaps derived from Pickt Hatch, an Elizabethan name for an area of brothels said to be in this part of London. It is mentioned in The Merry Wives of Windsor ('Goe … to your Mannor of Pickt-hatch') and The Alchemist ('The decay'd Vestalls of Pickt-hatch'). By the late eighteenth century the name Pickax had been dropped, and the road became a northern continuation of Aldersgate Street.

The principal features on the west side of Pickax Street in the late seventeenth century were two substantial inns of the type common on main roads out of London: the Horse and Groom and the Black Horse. Behind them, extended yards came into being after the break-up around 1700 of the old houses and gardens on the east side of Charterhouse Square (see Ill. 333). Black Horse Yard was the largest, with stables, coach-houses and rooms or gallery apartments. Beyond Aldersgate Bars, Goswell Street was 'meanly built and inhabited', reported John Strype in 1720. (fn. 51) Here the western frontage and the buildings behind belonged to the development of Glasshouse Yard after 1664, separately discussed below.

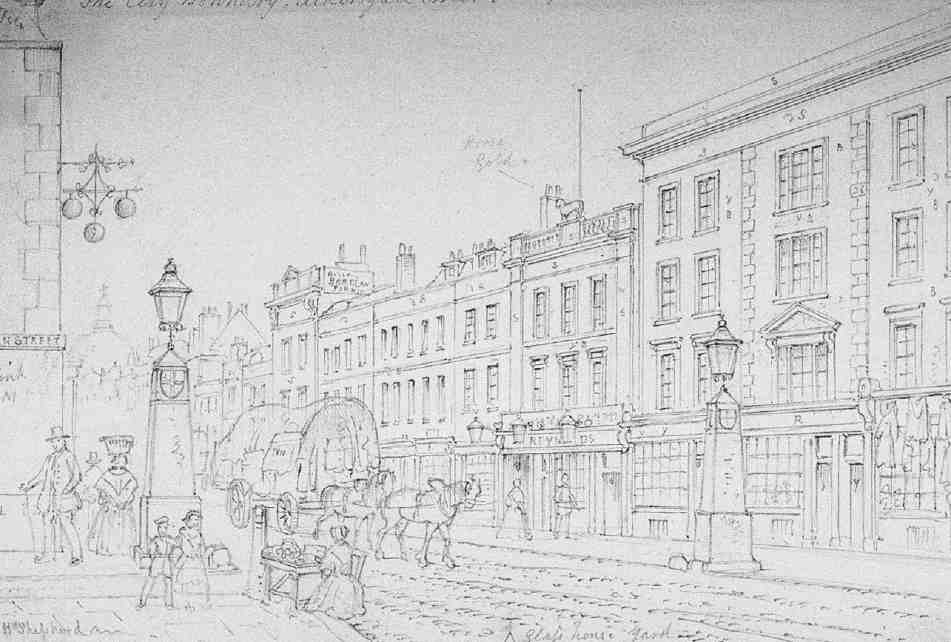

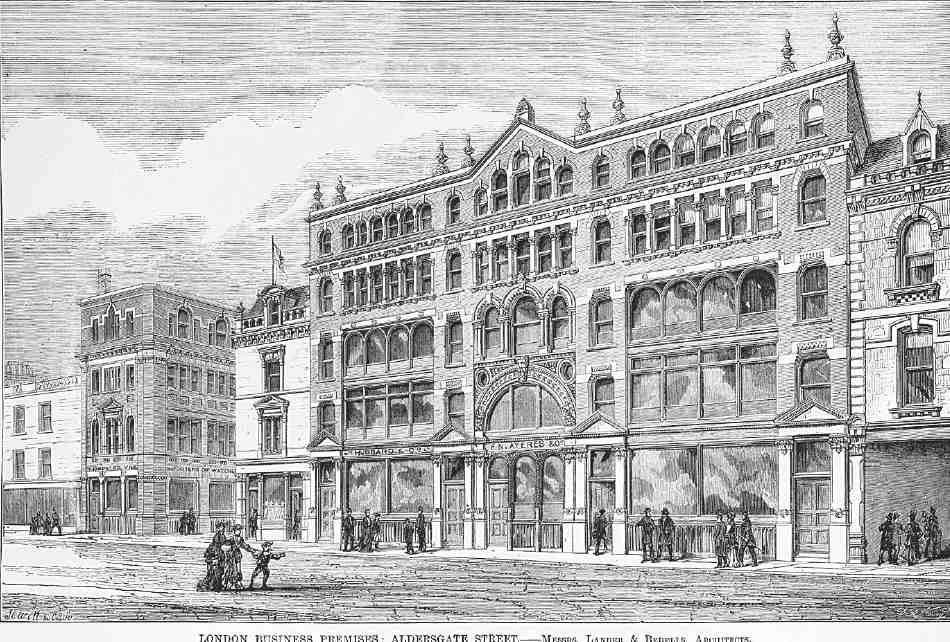

Despite piecemeal rebuildings of the shops and pubs along the main road, the frontage had attained a fair semblance of regularity by the mid-nineteenth century (Ills 379, 380). (fn. 52) But the properties behind had decayed into slums. When, typically for the times, a large warehouse was built on the sites of Nos 110–115 Aldersgate Street and the land behind, the Builder applauded the fact that it replaced 'small shops, with miserably low ceilings, and dirty, ill-ventilated back buildings' along with 'stables, immediately over which there dwelt in small and crowded rooms a large number of the labouring poor'. It added that the clearance would increase demand for improved dwellings, 'so that in the end it is to be hoped all classes will be benefited by the general "move on"'. The warehouse, elaborately fronted and iron-framed, was designed by Lander & Bedells (Ill. 382). (fn. 53)

This block was one of several badly damaged by wartime bombing and later demolished (Ill. 378). In the subsequent rebuildings, light manufacturing, notably the finishing of clothing, was at first as common as offices, but quite soon offices prevailed, not least because the authorities in the post-war years discouraged industry on the fringes of the City. On those grounds an applicant was refused permission in 1957 by the London County Council to use a portion of a new building in Glasshouse Yard, for making ladies' 'wearing apparel'. (fn. 54) Since about 1980 residential development has spread outwards from the Barbican and Golden Lane into this area generally, warehouses giving way to flats and a hotel, together with a mixture of other uses.

377. Aldersgate Street, looking south in 2006, showing junction with Carthusian Street. Nos 123 to 134 (right to left)

Aldersgate Street (west side)

Faced in yellow brick with stucco dressings, No. 107 and No. 1 Goswell Road were built around 1850 as part of a row of three houses, the third of which has been demolished (Ills 380, 383). No. 107 carries a plaque commemorating the erection of a drinking fountain opposite by Robert Besley in 1878.

No. 108, Crown House, is a neat brick-clad block designed in 1972 by a Hampstead firm of architects, Baldwin Beaton Everton & Isbell, to contain offices on the lower floors with flats above. (fn. 55)

Nos 110–115, replacing the Lander & Bedells building mentioned above, was built as Steinberg House, a warehouse, offices and ladies' clothing manufactory for Steinberg & Sons in 1963–4 to the designs of Emberton, Franck & Tardrew, with Tersons of Finchley as builders. C. L. P. Franck was the partner chiefly involved. This project, contemplated since 1956, was originally intended also to cover the site to the south where No. 120 now stands. The deep, seven-storey block is clad in brickwork and rests on a podium supported by columns clad in black glass mosaic. It was radically altered in 1995 when it was converted into flats for Barratts by the A & Q Partnership and renamed Cathedral Lodge (St Paul's, presumably, is visible from the upper floors). The alterations included the addition of three full-height bow-windows, one to Aldersgate Street, two towards Glasshouse Yard. The glazing bands are separated by polyester spandrel panels of duck-egg blue, affording a faint Festival of Britain air. (fn. 56)

No. 120, a concrete-framed office-building of 1977–8, named Priory Fields House, was designed for the British Land Co. by Elsom, Pack & Roberts. It was radically recast in 2000 for Bee Bee Developments Ltd, with new glazed elevations and a new four-storey building at the rear. (fn. 57)

378. Aldersgate Street looking south towards Barbican station in 1963. Right to left: No. 122 (demolished); Nos 125–127; beyond junction, Nos 129–131 and 133–134

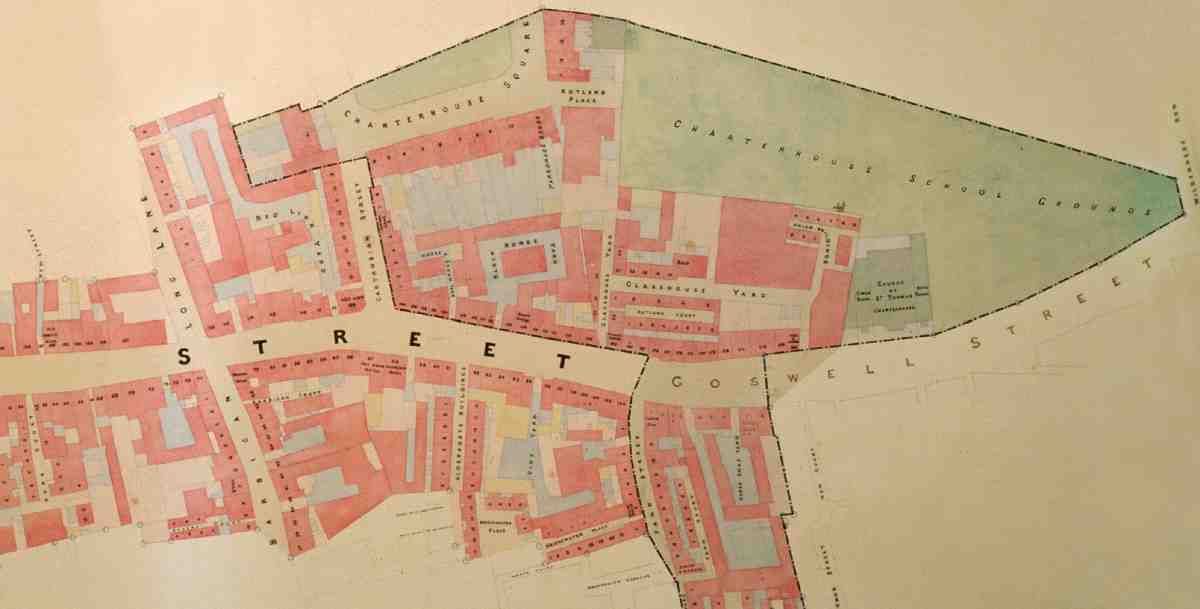

379. Aldersgate Street and Goswell Street in 1861, showing Liberty of Glasshouse Yard within border

No. 123 (Ill. 377) is a plain small office building of 1979–80 designed by Peter Thom Associates, structural engineers of Chingford, for Chester Estates Ltd, with A. Bell & Son as builders. (fn. 58)

No. 124, set back in a yard, originated as a plain Victorian industrial building behind No. 4 Charterhouse Square. In 1963 it was still being used by the firm of Roscoe & Howard for light engineering and included a forge, but by 1970 they had joined the flight of manufacturing industry from the area and relocated to Edenbridge, Kent. In 1980 the building was converted by Campbell Zogolovitch Wilkinson Gough (CZWG). Rex Wilkinson, the job architect, told the local authority that they were doing their best to retain the 'exceptional charm and character of the building's interior', including the timber main staircase. (fn. 59)

Nos 125–127 (Ills 377, 378) comprise a short terrace of three tall and narrow houses with ground-floor shops, probably built in 1854–5. (fn. 60)

No. 128 (Ill. 377) is a low and narrow four-storey house perhaps dating from around 1808. (fn. 61) The first floor has been refronted and a modern shopfront inserted but the top two storeys are relatively unaltered.

For Nos 129 and 131 see Carthusian Street, above.

Nos 133–134. This handsome Italianate bank building just north of Barbican Station was erected in 1873–4 for the London & County Bank by the builders Hill & Sons to the designs of C. J. Parnell. (fn. 62) A sophisticated exercise in the cinquecento banking manner (Ill. 381), it rises from a principal storey of granite with engaged Doric columns to limestone-clad upper storeys with Ionic and Corinthian window surrounds, and hence to a rich cornice. The carving is of high quality throughout. Large additions were made to unite the bank with neighbouring premises to the south, now demolished, in 1887–8. (fn. 63)

Goswell Road (west side)

For No. 1 see No. 107 Aldersgate Street, above.

Nos 3 and 5 were built as part of a row of four houses in 1802–3, making them the oldest surviving buildings in this small area (Ill. 383). (fn. 64) No. 5 has arched window recesses on the first floor. The wheatsheaf keystones, a later addition, denote the fact that it was at one time a bakery. (fn. 65)

Nos 7–21. This long red-brick front belongs to the Citadines Apartment Hotel, completed in 1993 for a French hotel chain, Orion City (Ill. 383). Their architects were the Boisot Waters Cohen Partnership. An asymmetrical arrangement of tiered balconies and a bow at the north end over the entrance add variety to the flat façade. (fn. 66)

No. 23, now known as Italia Conti House, was built as an eight-storey office block in 1959–61 to designs by Morgan & Branch, replacing a large warehouse of about 1866. (fn. 67) Its south end is carried on pilotis over the northern access to Glasshouse Yard, making the lower storeys asymmetrical. The upper six storeys are fronted by alternate window and spandrel strips within a strong overall frame of purple brick. In 1969–70 the building was converted for the use of the City University, becoming Lionel Denny House. (fn. 68) More recently it became the head offices of the Italia Conti Academy of Theatre Arts.

380. Aldersgate Bars looking south from Goswell Street into Aldersgate Street, drawn by T. H. Shepherd, 1857. Junction with Fann Street to left. Mostly demolished

381. London & County Bank, Nos 133–134 Aldersgate Street, c. 1887. C. J. Parnell, architect, 1873–4

382. Nos 110–115 Aldersgate Street. Lander & Bedells, architects, 1872–3. Demolished

No. 25, long a vacant site used as tennis courts, is currently (2007) being built up with flats and commercial space by the Irish property developers Thornsett Group. The new buildings will be linked to another new block adjoining Charterhouse Buildings in Clerkenwell Road. The site was formerly occupied by St Thomas's Charterhouse Church and related buildings, discussed in detail below. The church was built to the designs of Edward Blore in 1841–2, adjacent schools following on in 1846–7 and two parsonages to the north in 1869–70. The church and schools were demolished in 1909, but the parsonages survived until the Second World War, when they were damaged beyond repair. Various post-war plans to build a hall of residence for St Bartholomew's Medical College here failed to mature. (fn. 69)

St Thomas's Charterhouse Church and Schools (demolished)

St Thomas's was a project instigated by Bishop Blomfield of London about 1839 for the purposes of serving a very poor district that lay largely within the parish of St Luke's, Old Street, on the east side of Goswell Road, beyond the area covered by the present volume. The second vicar of St Thomas's, William Rogers, claimed that Blomfield 'had a mania for erecting churches in all sorts of inconvenient places. He could not … have chosen a much less favourable situation, but, as a Governor of the Charterhouse, he got the land for nothing and other considerations had to give way'. (fn. 70) The site was formerly part of the Charterhouse's school playing ground and wilderness garden, which stretched northwards from here to Clerkenwell Road. The Charterhouse sold this piece of land to the Commissioners for Building New Churches in 1839. A district of seventeen acres was formally assigned to the church in June 1843, well after its completion, under Peel's Act of that year for the subdivision of parishes. According to Rogers, it was entirely inhabited by costermongers and ragamuffins. (fn. 71) In 1862 this district was halved in size when a second daughter church and parish of St Mary Charterhouse were created—to the east of the area covered by this volume.

383. Goswell Road, looking north in 2007; Nos 1–23 to left

Blore's design for the church (Ill. 385) adopted a bare, round-arched Romanesque style in brick, popular at the time and similar to his recent churches of St Peter, Stepney, and Holy Trinity, Barkingside, Essex. (fn. 72) Building was carried out by Robert and George Webb and cost a little over £6,000, supplied by the Metropolis Churches Fund. Consecrated in August 1842, the church provided 680 rented sittings and 336 free seats. (fn. 73) The interior was aisled and galleried on three sides. Externally, the east front facing Goswell Road featured a shallow three-sided apse in the centre flanked by the ends of aisles, of which the northern one was surmounted by a squat tower crowned with an octagonal turret and pointed roof. Surviving illustrations suggest a sombre building. Rogers called it an 'unsentimental structure of the Bishop Blomfield era'. (fn. 74)

Little is recorded of the church interior. In 1877 the galleries were removed, and in 1881 St Thomas's was 'artistically decorated', the deal floor of the chancel and sanctuary being replaced with a tile pavement, and various new fittings added. The works were executed by John Allen & Sons, builders, to designs by Medland & Powell, architects. (fn. 75)

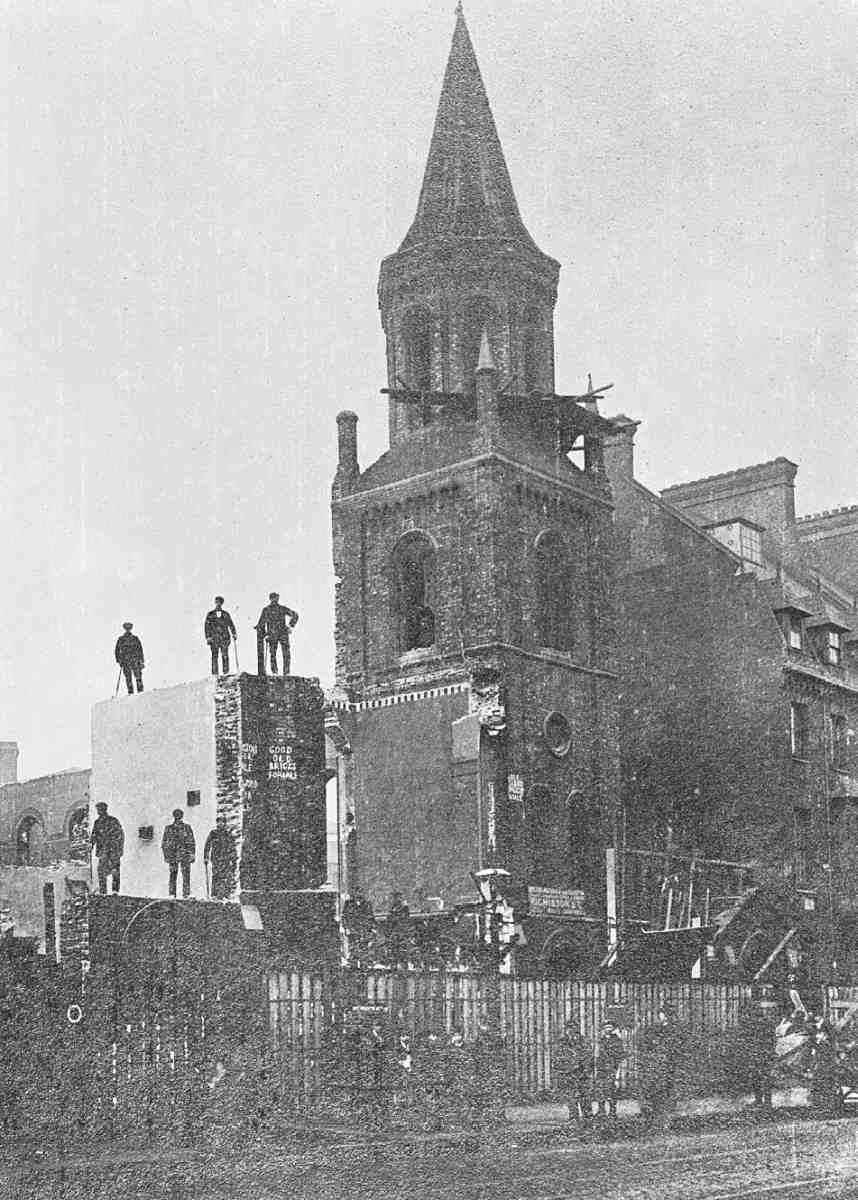

384. St Thomas's Charterhouse Church, Goswell Road. Demolition in 1909

385. St Thomas's Charterhouse Church, Goswell Road. Elevations of east (left) and west ends. Edward Blore, architect, 1842. Demolished

St Thomas's was closed in July 1906 and the district amalgamated with that of St Mary's. Most of the fittings were removed to St Mary's, but the organ was installed in St John's, Upper Edmonton, and the stone font—a gift of about 1891—taken to the new church of St Michael, Cricklewood. The freehold site of the church and adjacent schools was then sold at auction and the buildings were demolished (Ill. 384). (fn. 76)

St Thomas's was noted for its pioneering schools, instigated by the muscularly Christian second vicar William Rogers (1845–63). Concluding that 'it was ludicrous that an individual with the scanty education and loose habits of a costermonger would voluntarily sit through a liturgical service of which he could not understand a word', Rogers 'set to work on the children'. After searching in vain for a site, he 'fastened upon the space round the Church, thinking that by using the walls of the building and clapping a roof on top, the thing might be done cheap'. (fn. 77) By this curious and controversial device, two school blocks were built abutting the church on its north and south sides in 1846–7 to the plans of Robert Hesketh. On the insistence of the Church Commissioners they were designed to resemble extra side aisles. (fn. 78)

These schools flourished, and Rogers claimed them as the first where the pupil-teacher system was introduced. Since the children who attended these schools 'did not come from Costermongria' but were mostly of artisan parentage, he proceeded with aristocratic and mercantile support to open fresh schools on the opposite side of Goswell Street in 1853, and in 1857 yet further schools in Golden Lane, aiming increasingly to educate the very poor but avoiding the concept of the ragged school. (fn. 79) After Rogers's translation to St Botolph Bishopsgate in 1863, his educational work was carried on by the next vicar of St Thomas's, the Rev. John Rodgers, who under the changed circumstances of the 1870s became an influential member and vice-chairman of the London School Board. At Rodgers's death in 1880 it was said that his work at the St Thomas's Charterhouse Schools had 'done much for the education of the lower middle classes'. (fn. 80)

St Thomas's and St Mary's vicarages (demolished)

William Rogers repeatedly requested the Ecclesiastical Commissioners to provide a parsonage house for St Thomas's. He thought it should not be close to the church since 'the neighbourhood is so extremely low that no clergyman could with any propriety or comfort reside in it', preferring Charterhouse Square as 'an eligible situation' which already contained the parsonages of St Botolph without Aldersgate and St Sepulchre. (fn. 81) Only after the parish had been subdivided in 1862 and Rogers had been succeeded as vicar by John Rodgers did the Commissioners acquire the plot to the north of the church (see page 390). There they built houses for the vicars of St Thomas's and the new parochial district, St Mary, Charterhouse. Ewan Christian provided the plans and the houses were built in 1869–70. Benjamin Wells was the builder of the St Thomas's parsonage, while Thomas Ennor built the abutting parsonage of St Mary's to the north. (fn. 82) Both were damaged in the Second World War and afterwards demolished.

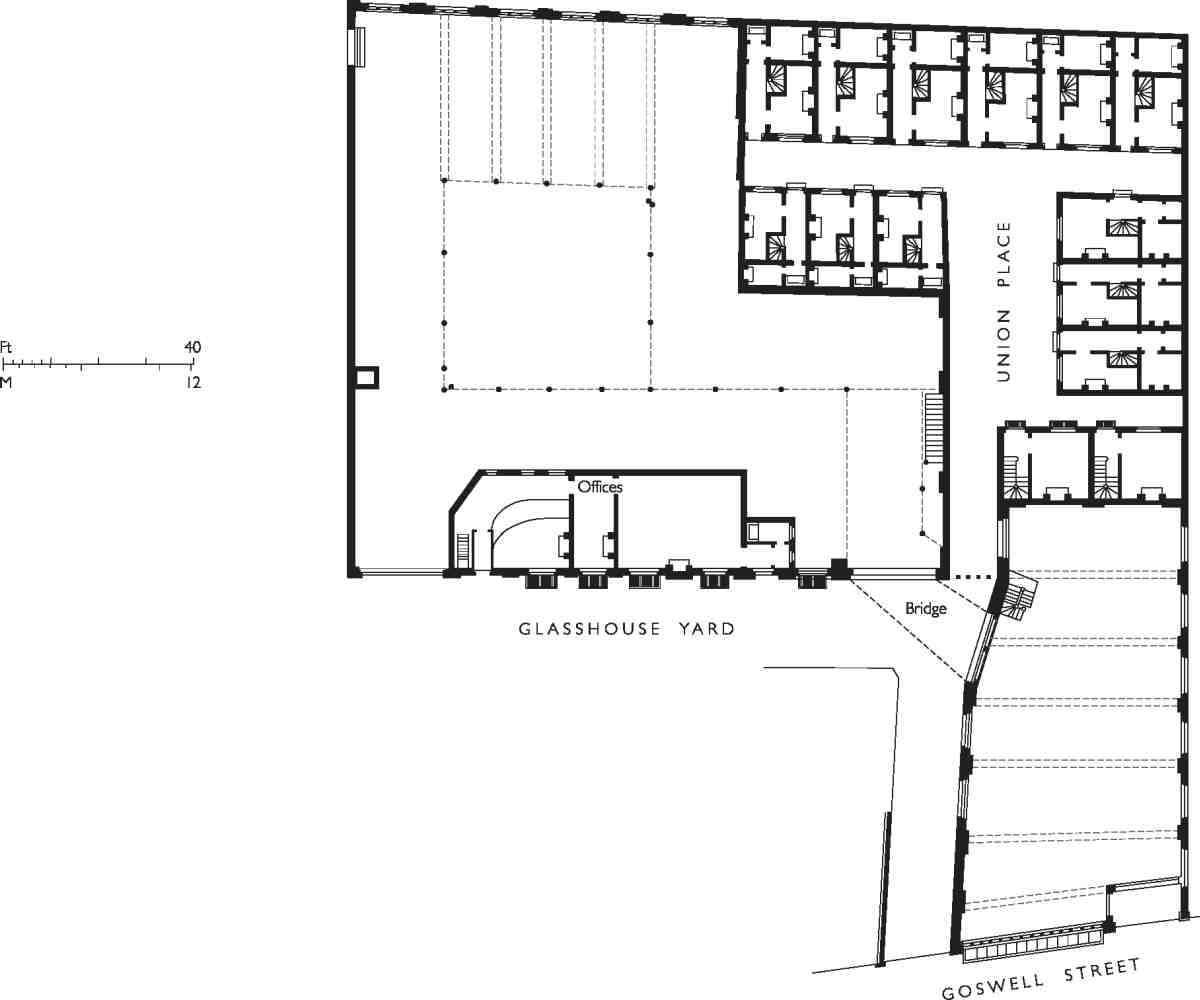

386. Glasshouse Yard, plan of railway carriage works and tenements in Union Place in 1865. All demolished

Glasshouse Yard

Glasshouse Yard is an easily missed, now rather characterless backwater west of Aldersgate Street and Goswell Road. The street is essentially T-shaped, with two entrances from Goswell Road. Its picturesque name stems from a short-lived glassworks set up here in 1660 by the 2nd Duke of Buckingham, when this area was part of the garden to Rutland House, adjoining the Charterhouse.

By 1716 at the latest a wider district had been designated the Liberty of Glasshouse Yard, partly within the City and partly beyond. By 'liberty' was meant an independent district for the purposes of local jurisdiction. The origin of this one was explained in 1756 by the fact that 'the Poor of this Liberty having increased considerably, occasioned the City Liberty to separate from them, and each to maintain its own Poor'. (fn. 83) For a time the Liberty ran its own workhouse, but by a 'tacit understanding' its poor were eventually sent to that of St Botolph without Aldersgate, to which parish the area still belonged. (fn. 84) The Liberty covered Glasshouse Yard, the area southwards to Carthusian Street, part of Charterhouse Square, and a finger of land on the east side of Goswell Road, north of Fann Street (Ill. 379). (fn. 85) Very few records survive for the Liberty, and no clue as to its formation or basis.

The Liberty was not renowned for good government. According to William Rogers of St Thomas' Charterhouse Church, writing of the 1840s, 'The Act of Parliament prescribed that the police rate should be collected by the overseers, and as in our land of liberty there was only one overseer, the rate was not collected, and the police were not employed. Those of the inhabitants who had any property were naturally anxious that it should not be at the mercy of every blackguard whose greedy eyes were fixed upon it, but we were out-voted in the vestry by those whose belongings were of such a trashy description that they were not worth the trouble of stealing. The Church and I suffered in turn. One night the communion plate was carted off, and six weeks later my house was broken into'. (fn. 86) The Liberty's independence was still causing problems in co-ordinating local infrastructural works on Goswell Road as late as 1859. (fn. 87)

Records of the Duke of Buckingham's glasshouse (c. 1660–4) are scanty, but it is known to have been one of the first in England to make Venetian-style rock-crystal glass. (fn. 88) The manufactory may either have been new, or in a converted garden building or stable, like an earlier crystal glassworks of 1658 at Nijmegen, set up in a converted chapel. Buckingham appointed John de la Cam to oversee the work. The latter's application to manufacture crystal glass in England specifically states his intention to 'discover … the Art and Mistery of melting of Christall de Roach'. (fn. 89) De la Cam appears to have left by November 1661, when a licence was granted to Martin Clifford (Buckingham's secretary and later Master of the Charterhouse) and Thomas Paulden for a term of fourteen years, for the exercise of their 'Arte skill & invention of makeing Christall Glasse'. A patent was granted to them a year later. (fn. 90) In 1663 Clifford and Paulden surrendered their grant to Thomas Tilson. This may have coin cided with the establishment of Buckingham's glassworks at Vauxhall, where mirror-plate as well as crystal glass was made. (fn. 91) At any event, glassmaking on this site ceased soon after.

387. Glasshouse Yard, looking north in 2006

In 1662 Buckingham had surrendered Rutland House to his creditor John Eaton and in 1664 Eaton and John Nelthorpe divided much of the house and all of the garden into building plots. Extensive subdivision of the glasshouse site is clearly shown in Ogilby & Morgan's map of 1676 (Ill. 333), with some plots tightly built up and others as yet empty. The first buildings were mostly coachhouses, stables and workshops, and two public houses. There was also a sawmill at the north end of the yard, and a Baptist meeting-house, established by Francis Smith by 1669, with a small burial ground to the rear. The Baptists removed to the Barbican in 1768, but the chapel remained in use by Independents for some years more. It was sold at auction in 1825 and demolished shortly afterwards. (fn. 92)

Subsidiary courts off the yard in the 1740s were called Rutland Court (not to be confused with the Rutland Court off Charterhouse Square), Ship Yard (after the Ship pub), Peel Yard and Pump Yard, while addresses included Snaggs Tenements and Mawsons Rents. The housing was occupied by poor or lowly paid workers. (fn. 93) In 1825 the freehold of much of Glasshouse Yard was sold by the descendants of John Eaton and broken up into small parcels. Purchasers included a distiller, grocer, scalemaker, tyre and coach smith, tallow chandler, stationer, linen draper, chemist and druggist. (fn. 94) Shortly after the sale, a fresh court called Union Place appeared in the north-western sector. (fn. 95)

In the nineteenth century the scale of industry in the enclave increased. The biggest enterprise here (Ill. 386) developed from a coach works and tyre manufactory at the north end, purchased by James Whitburn in the sale of 1825. It became a railway carriage works in the hands of either Walter Williams or Charles Cave Williams in the 1840s. By the time of the latter's bankruptcy in 1865, the premises wrapped round the tenements of Union Place and included a warehouse at No. 23 Goswell Road, connected to the main works by a bridge. By 1898 the railway works had become a smithy and repairing shop for Pickford & Co. the carriers, and by the 1930s the Harris Plating Works. (fn. 96) In the early twentieth century this and other properties along the main western frontage of Glasshouse Yard appear to have been the freehold of the executors of David Cohen, for whom the firm of Lewis Solomon acted as architects in various respects. (fn. 97)

Along with these industrial developments went attempts to improve the housing and facilities. A 'refuge for the houseless poor' fitted up with a few baths existed here in 1848. (fn. 98) Later, some artisans' dwellings were erected, among them Glasshouse Chambers of 1888 on the site of the present Nos 26–28, and the current No. 10 of 1885, now the sole survivor of the buildings built before the Second World War, in the former Rutland Court. (fn. 99) A renumbering took place in 1936–7, when Union Place and Rutland Court were subsumed into Glasshouse Yard. Extensive wartime bombing, subsequent clearances and rebuildings, some large-scale, have transformed the area (Ill. 387). The first post-war buildings still had a measure of manufacture in mind, clothing especially, but warehousing, offices and computing had replaced that by the 1970s.

Other current buildings numbered in Glasshouse Yard are as follows:

No. 8. A plain two-storeyed building of 1956–7 on a concrete frame, designed by Geoffrey Shires, architect, and built by A. A. Contractors of Deptford. Though intended for the manufacture and storage of ophthalmic supplies, the upper storey was used from the start for women's clothing; by 1962 the occupants dealt in cine equipment. (fn. 100)

Nos 20–25 (Ruth Potter House). Corner building of three main storeys, with piers of blue engineering bricks and windows of varying width, built by William Moss Ltd for Trust Securities Holdings to the designs of the Thomas Saunders Partnership, 1979–81. (fn. 101)

Nos 26–28 (The Glasshouse). A composite, inchoate building with recessed and glass-fronted lower storeys behind concrete piers, protruding second storey and further accommodation above. Its core appears still to be the warehouse and model-gown workrooms built here by Geoffrey Shires and John Reddick, architects, in 1955. In the early 1970s it became the Barbican Computer Centre of the Post Office's Data Processing Service; many alterations followed. The present appearance of the building is due to large additions of about 1999–2001 by C2 Architects. (fn. 102)

Nos 29–30. At the time of writing, an eight-storey building housing student study-bedrooms was erecting here to the designs of T. P. Bennett, architects. It replaced Therese House, a brick-faced office building of similar size. A speculation of the developer Harry Hyams, this was built in 1959–60 by Wates Ltd to the designs of Richard Seifert & Partners. Like Nos 26–28 it was used from the 1970s by the Post Office's computer services. (fn. 103)