An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in City of York, Volume 2, the Defences. Originally published by Her Majesty's Stationery Office, London, 1972.

This free content was digitised by double rekeying. All rights reserved.

'The Old Baile', in An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in City of York, Volume 2, the Defences(London, 1972), British History Online https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/rchme/york/vol2/pp87-89 [accessed 9 May 2025].

'The Old Baile', in An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in City of York, Volume 2, the Defences(London, 1972), British History Online, accessed May 9, 2025, https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/rchme/york/vol2/pp87-89.

"The Old Baile". An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in City of York, Volume 2, the Defences. (London, 1972), British History Online. Web. 9 May 2025. https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/rchme/york/vol2/pp87-89.

THE OLD BAILE

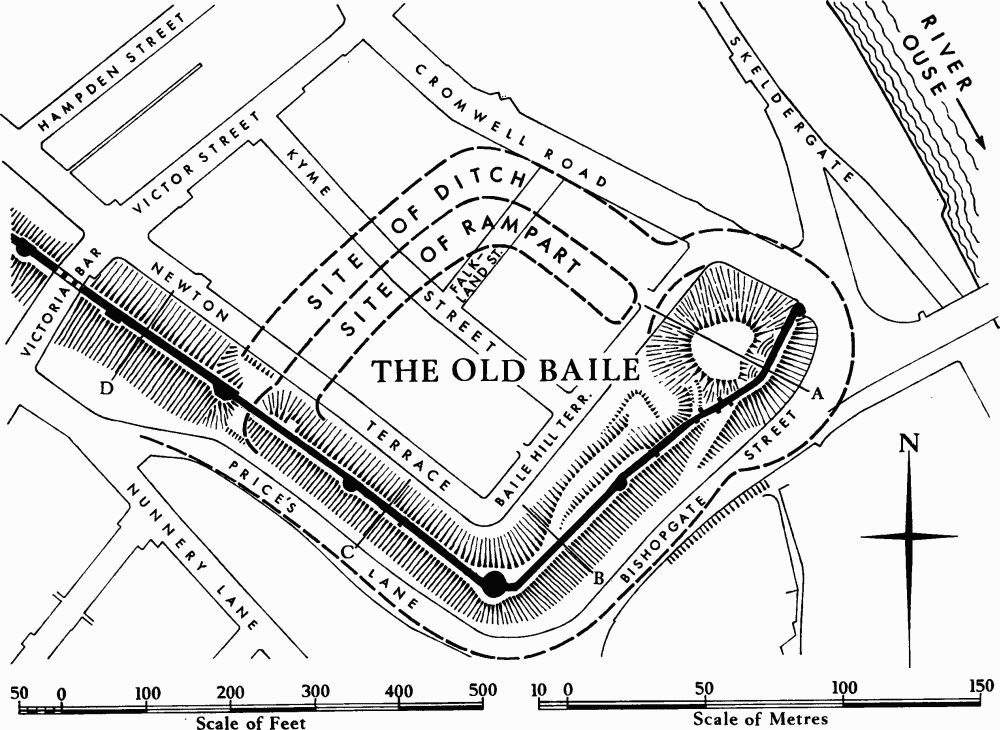

The Old Baile (Pl. 17; Figs. p. 88, opp. p. 41), a motte-and-bailey castle constructed by William I, stands on a low natural ridge parallel to the river, with the motte on the tip of the ridge. It is uncertain whether the site was within earlier town defences or adjoined them on the S., but it was partly occupied by a Roman cemetery which included tile-built tombs. (fn. 1) Pre-Conquest occupation material, including two Northumbrian stycas, iron weapons and bone comb cases, has also been found here. (fn. 2) The castle was built in 1068 or 1069 but, like York Castle on the other side of the Ouse, was destroyed by the Danes in September 1069 and rebuilt by the king almost immediately. (fn. 3) Coin hoards of silver pennies of Edward the Confessor and William I, one of them buried in a Stamford ware crucible, were found here in 1802 and 1882. (fn. 4)

On 12 June 1268 a trial by wager of battle over a pasture disputed between the townships of Birdsall and Thixendale was held 'in Veteri Ballia Civitatis Eboracensis'. (fn. 5) A reference of 1190 to 'castellum in veteri castellaria' (fn. 6) apparently relates to York Castle. Before the 14th century the Old Baile had passed into the possession of the archbishops, perhaps when Geoffrey Plantagenet was both archbishop of York and sheriff of Yorkshire in 1194–8. In 1308 Archbishop Greenfield ordered the excommunication of citizens who broke down the gates and had bows and arrows ready to shoot anyone who tried to stop them. (fn. 7) In 1309 he ordered payment of 'the money necessary for making a foss in the Old Baily, for procuring plants to put in the said foss, and for repairing the road to the mills'. (fn. 8)

In 1322 Archbishop Melton agreed with the commonalty of York to defend the Old Baile in time of war, provided that, if it was the object of a special attack, the citizens would help in the defence. (fn. 9) In July 1327 the defence of this castle was again in dispute between the city and the archbishop: at a royal council meeting in the presence of Queen Isabella the mayor and clerk persuaded the primate to agree to place some of his men there while the royal family was in the city, provided that the citizens would help in case of an attack by the Scots. The citizens argued that 'the place was outside the city's ditches', but the archbishop, although agreeing that 'he had once caused the place to be en closed and placed men there for its defence', asserted that the defence of the Old Baile was the responsibility of the mayor and community. (fn. 10) The defences built by Melton consisted at first of planks 18 ft. long and later, and presumably after 1327, of a stone wall. (fn. 11) In two of the three surviving custodies the responsibility for the Old Baile is ascribed to the archbishop.

Controversy over the defences of the castle was still continuing a century later in 1423, when Archbishop Bowet was sued in the Court of Common Pleas to force him to repair a certain portion of the city walls called the Old Baile, of which a large part had collapsed for lack of repairs. (fn. 12) In 1453–4 Guy Fairfax, later the Recorder, was paid 6s. 8d. for his advice in the dispute. (fn. 13) It ended with the city obtaining possession of the castle: in 1466 the Old Baile was described as having been recently granted by Archbishop William (Bothe, 1452–64) to the mayor and commonalty and their successors. (fn. 14)

From 1466 onwards the city leased the Old Baile for grazing, as the archbishops had done, usually for 26s. 8d. per annum. (fn. 15) The area was also used for musters from 1487, when the wards appeared in harness during Lambert Simnell's rebellion, (fn. 16) and during the 16th and 17th centuries. (fn. 17) The annual 'view of artillery' was held there: in 1609 it was stipulated that citizens aged between 7 and 17 should appear with a bow and two arrows, and those aged between 17 and 40 with a bow and four arrows. (fn. 18) At Leland's visit the rampart and ditch were still visible, and they are shown on Speed's map.

The Old Baile

In 1566 the city council decided that 'where as in the Old Baill there is a part of one inner tower called the Biche Doughter tower already shronken from the Citie wall, and may be well taken away withowte enfeblyng or greatly defacyng of the sayd wall it is therfor thought needfull to take downe the sayd broken tower, and the stones therof comyng to be caryed and converted towards . . . repayring of Ouse brig'. (fn. 19) This tower was no doubt the king's gaol called 'le bydoutre', for repairs to which the city paid in 1451–2. (fn. 20) In 1581 Archbishop Sandys unsuccessfully tried to claim the Old Baile from the city. (fn. 21)

During the Civil War 'two cannon were planted upon old Bayle', (fn. 22) and this was probably the 'Fort Eastward in the City' from which, as well as from Clifford's Tower, the besiegers were bombarded in 1644. (fn. 23) A watch house was built there in 1645, probably now incorporated in Tower 3. (fn. 24) In 1722 Henry Pawson, then tenant, 'leveled the Top of Old Bail Hill and set it about with young Firr Trees and Other Forest Trees'; these were replanted in 1722 and 1726. (fn. 25) Ash trees had already existed in the bailey in 1628, when some were blown down. (fn. 26) A prison for the debtors and felons of York and the Ainsty, designed by Peter Atkinson, was erected in 1802–7 in the N. part of the bailey. (fn. 27) It was closed in 1868 and demolished in 1880. In 1882 most of the bailey was sold to builders, and it is now occupied by Baile Hill Terrace, Newton Terrace, Kyme Street, and Falkland Street. During the 18th and 19th centuries the bailey, popularly known as 'The Hollow', was used for Shrovetide games. (fn. 28)

Baile Hill, the motte, is the principal surviving fragment of the castle (Pl. 17; Figs. p. 88, opp. p. 41). It stands 200 ft. W. of the Ouse and 760 ft. S.W. of the contemporary motte of York Castle. It is 180 ft. in diameter at the base and 40 ft. high with a flat top 70 ft. across. Trees on the slopes and summit are the successors of those planted in 1722. The straightness of the S.E. side at the summit and two sharp angles are probably the result of 17th century alterations to take two cannon. A view by Samuel Buck of c. 1720 ('The South Prospect of the Antient City of York from the Old Baile Hill') shows the summit as irregular with possible earth ramparts around the edge. The mound was derived presumably mainly from the surrounding ditch, which is now only traceable as a slight depression 40 ft. wide in the rampart to the W.

Excavations by Mr. P. V. Addyman for the Royal Archaeological Institute were carried out in 1968 and 1969. (fn. 29) They were confined to the summit and S.W. side of the motte and to small areas at the base on the S.W. The motte had been constructed in roughly horizontal layers sealing an old ground surface, which contained 11th-century occupation debris, and a Roman pit. On the summit deposits over 3 ft. thick, including masonry from the city wall, 17th-century objects, and Saxo-Norman pottery, probably represent the build-up for the battery in 1642. These deposits covered a cobbled area in which was much Saxo-Norman pottery and 11th to 12th-century objects. A 12th-century rectangular timber structure was set centrally on top of the motte with a smaller structure at one corner, of which the lower part was enclosed by the mound. There was a mortar floor around this structure and also a perimeter palisade. On the S.W. face of the motte eroded debris had sealed a flight of steps formed in the clay slope and probably once faced with wood. These were perhaps the original means of access from the bailey to the summit of the mound. The edges of a wide and deep ditch surrounding the motte, with remains of timber structures on the outer lip, were located. Many arrow heads found in the sides of the mound are no doubt relics of the 16th and 17th-century 'views of artillery', when the mound must have been used as an archery butt. Finds of 18th and 19th-century thimbles, needles, coins, and ornaments belong to the use of the area for recreation.

The bailey was rectangular, measuring about 500 ft. by 350 ft. along the ramparts and containing 3 acres. The S.E. and S.W. ramparts, the only ones to remain, are 89 ft. to 103 ft. wide, 24 ft. to 26 ft. high externally, and 17 ft. internally. Most of the bailey, where not built over, has been destroyed by late mediaeval and modern scarping. The curve of the outer ditch at the W. angle appears as a depression in the rampart and is marked internally by a brick patch in the city wall where this has subsided; part of its course is marked on the OS large-scale plan of 1852. The ditch formerly continued across nos. 6–8 Newton Terrace and nos. 22–6, Kyme Street, turned across the end of Falkland Street and ran along the S.W. side of Cromwell Road to join the ditch around the motte. Its width was 40 ft. to 50 ft. Subsidence and cracks are visible on houses along its course. The entrance was probably on the N.N.W., towards which a lane once led from Bishophill.