An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in City of York, Volume 2, the Defences. Originally published by Her Majesty's Stationery Office, London, 1972.

This free content was digitised by double rekeying. All rights reserved.

'History', in An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in City of York, Volume 2, the Defences(London, 1972), British History Online https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/rchme/york/vol2/pp7-34 [accessed 18 April 2025].

'History', in An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in City of York, Volume 2, the Defences(London, 1972), British History Online, accessed April 18, 2025, https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/rchme/york/vol2/pp7-34.

"History". An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in City of York, Volume 2, the Defences. (London, 1972), British History Online. Web. 18 April 2025. https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/rchme/york/vol2/pp7-34.

In this section

THE DEFENCES

Before the Norman Conquest

At the end of Roman rule the defences of Eburacum consisted of the strong fortifications of the legionary fortress together with an adjacent enclosure to the N. W., both in the central area of the city, (fn. 1) and of the wall around the civil town or colonia on the Micklegate side of the Ouse (Fig. p. 58). Little is known of the wall of the civil town, but it has been found at three or four places under the later rampart on the N.W. side. The walled area probably coincided with the mediaeval enclosure on that side, but may elsewhere have lain within. This is suggested by burials found at Baile Hill, probably outside the Roman defences, and by the discovery of a house with mosaic floors under the mediaeval rampart in Toft Green.

The legionary fortress was rectangular, 50 acres in extent, with its long axis aligned N.E.-S.W., approximately at right angles to the Ouse. Its defences were largely rebuilt in about 300 A.D. under Constantius I. After this reconstruction they consisted of a stone wall 5 ft. thick and 20 ft. high, an internal earth rampart 20 ft. or more thick and 10 ft. high, and an external ditch 23 ft. to 30 ft. wide and 6 ft. to 8 ft. deep. There were four large gatehouses, two of them set in the centre of the shorter S.W. and N.E. sides, in St. Helen's Square and N.E. of Gray's Court, and two in the long sides, under Bootham Bar and King's Square. The S.W. side of the fortress had large multangular towers at the angles and six intermediate projecting polygonal towers. Along the other three sides and at the N. and E. angles there were smaller rectangular internal towers. A walled enclosure of unknown purpose and at least 8 acres in area adjoined the fortress to the N.W., occupying the area between Bootham, Marygate, and a line continuing the S.W. wall of the fortress.

In the late 7th century a grant of land mentions both the 'city wall towards the south' and the 'great gate towards the west' (the N.W. gate on the site of Bootham Bar), (fn. 2) indicating that it was still a landmark and presumably then in use. In the 8th century Alcuin refers to 'the high walls of the city of York' and describes the city as 'lofty with walls and towers'. (fn. 3) Such phrases may, however, be no more than a poetic echo. In 867, during the warfare which resulted in the capture of York by the Danes, the Northumbrians pursued their enemies 'inside the city defences and began to break down the wall; for in those days that city did not possess strong and well-built walls'. (fn. 4)

Analysis of the finds of the Roman fortress wall indicates that along the N.W. and N.E. sides it still stands, generally in good condition, to a height of 12 ft. to 16 ft. On the S.E. side the wall has been reduced to a height of 8 ft. to 9 ft., and near the E. angle, where only the foundation and plinth remain, a series of wooden stakes, set 1 ft. apart, continued the curve of the wall, indicating apparently a post-Roman attempt to defend a breach. (fn. 5) On the S.W. side the wall had been reduced to its present height of 6 ft. to 8 ft. before it was strengthened by the addition to the rampart of a clay bank, which contained a coin of 335–7 A.D. It had been cut down before the 11th or 12th century, since a building perhaps of the 9th-10th century was erected on top of it.

The differential survival of the Roman wall is not due to the protection of the post-Roman mound which covers it. The height and width of the mound and its consequent incorporation in the Norman defences are due rather to the varying height of the surviving stretches of Roman wall which it covered. This variation is probably due to the expansion of the Northumbrian city to the S.W. and S.E. of the fortress enclosure, when, during a period of comparative peace, the walls on those sides were closely surrounded by timber buildings and probably used as a quarry for stone churches and house footings. On the other two sides of the fortress the Roman wall was still used as a defence. A breach in the wall was blocked, perhaps in c. 650 A.D., by a vaulted defensive tower with doorways leading to a sentry walk along the rampart. Another breach was noted to the N.E. of this tower (19), near the modern St. Leonard's Place. The tower, together with the Roman wall, was buried under a broad earth rampart, no doubt made after the fall of the city in 867. A large coin hoard, ending with issues of c. 865, apparently concealed at that time in the rampart near Bootham Bar, was also sealed under this new earthwork. (fn. 6)

At the time of the Danish conquest then, it appears that on the N.W. and N.E. the walls of the legionary fortress were standing to almost their full height and were in use as the city walls, but on the other two sides were ruinous and breached. At least three, if not all, of the gatehouses were probably substantially intact, as were the angle towers and some of the interval towers. Within the fortress much of the headquarters building had remained standing to a considerable height until the early 7th century, and parts were still visible above ground in the 12th century.

In 876 one section of the Danish army 'restored the walls of York, settled the surrounding region, and stayed there'. (fn. 7) Asser implies that in his time (c. 893) the city had strong and stable walls. (fn. 8) The new Danish defences included the whole of the legionary fortress and an area of some 37 acres extending S.E. to the Foss. On all sides but the S.E. the Roman wall was covered by an earth rampart varying in size according to the height of the surviving wall and, at least on the N.W., where it was 18 ft. high and 35 ft. wide, capped by a palisade revetted with stone. At the E. angle of the fortress the rampart continued the line of the N.E. wall, probably as far as Peasholme Green. Along the marshy banks of the Foss there was built in the 10th-11th century a flood bank, known in the 14th century as 'Dunningdykes', and found in 1950–1 on the site of the Telephone Exchange in Hungate. (fn. 9) This bank, of layers of brushwood and clay laced with stakes, was piled on a raft of brushwood pinned down to the old ground surface by pointed stakes and weighed down by large boulders. It was about 8 ft. high and over 40 ft. wide. A length of 60 ft. was seen; its line is continued by property and parish boundaries to the re-entrant angle in the present defences opposite Jewbury.

From the S. angle tower of the fortress a bank and stockade ran S.S.E. towards the Foss. This stockade was seen in 1902 under Nos. 5–7, Coppergate, and was traced for 32 ft. (fn. 10) It was 8 ft. high, of hazel boughs plaited through two rows of birch posts, but had been abandoned as a defence during the 10th century, and the site had later become a tannery.

The S.E. gatehouse of the Roman fortress may have been standing sufficiently intact to form the nucleus of a Danish royal palace, from which King's Court, earlier Koningsgartha or Curia Regis, derives its name. (fn. 11) In the Saga of Egil Skalagrimsson part of the action takes place in the hall of King Eric Bloodaxe at York in about 948, perhaps at this spot. It may have been the castrum razed to the ground by Athelstan in c. 930, when he distributed to his army the ample booty found there. (fn. 12) The Trajanic inscription from above this gateway was found in 1854 at a depth of some 27 ft. within the Roman walls; the presumption is that it was overthrown into a deep ditch surrounding this castrum. (fn. 13) In a yard W. of King's Square posts of a 10th to 11th-century wooden building were found in 1957 cut into the top of the Roman rampart within 4 ft. of the fortress wall. Combs, wooden bowls, whetstones, and pottery of this period were found on the site in 1963. (fn. 14)

It is uncertain whether the rampart around the Micklegate area of the city also incorporates a pre-Norman bank covering a Roman wall, here of the colonia, but this part was certainly occupied during the 10th century. Six churches founded before 1100 lay within the mediaeval defences on this side of the river, and two Roman streets remained in use for at least part of their length. York in the 10th and 11th centuries was a mercantile city on both banks of the Ouse, and the indications of its wealth and size should imply fortification of the settlement around Micklegate, which would require protection even if the Roman defences did not survive.

As early as c. 780 a colony of Frisian merchants had settled in the city. (fn. 15) A vivid picture of York in the later years of Danish rule is given by Egil's Saga, which in its present form is an Icelandic document of the 13th century incorporating earlier, orally transmitted, verses. (fn. 16) Not only did Egil's enemy, King Eric, have a palace and a hall in the borough, but his helper, the courtier Arinbjorn, also had a large house with a courtyard, hall and upper rooms. Merchants from York were plundered by the men of Thanet in c. 970, and the robbers were consequently punished by King Edgar. (fn. 17) Some thirty years later the biographer of Archbishop Oswald described the city as the metropolis of the Northumbrians, once nobly built and strongly walled but now decayed through age, though still with an adult population of at least 30,000 and filled with the wealth of merchants from all parts, especially merchants of Danish origin. (fn. 18)

In view of this evidence it seems probable that by c. 950 the Micklegate part of York was already enclosed by an earth bank. The short stretch of rampart between the Roman fortress wall at St. Leonard's and the Ouse at Lendal Landing had presumably also been constructed to protect houses along Coney Street and to block access beside the river. At the S.E. end of the city the Foss would have made a similar defence work less necessary, but the erection of the castle has modified the topography there.

After the English reconquest of Northumbria the Earls apparently resided to the N.W. of the city. Here 'there was an ancient street enclosed with a ditch . . . which in English is called Earlsborough'. (fn. 19) The defences were still standing in about 1085, when monks from Lastingham led by Stephen of Whitby were induced to settle here by Count Alan of Brittany 'propter loci munitionem'. He gave them St. Olave's church, a minster built by Earl Siward some 40 years before 'at Galmanho', together with 4 acres of land. (fn. 20) Later the area held by the monks was extended by gifts from William II and others; as St. Mary's Abbey, the monastery became one of the most important Benedictine houses in the North.

The probable limits of Earlsborough are: on the N.W., the S.E. side of Marygate, including St. Olave's and extending S.W. to a point where the mediaeval abbey precinct wall changes direction; on the N.E., the S.W. wall of the Roman enclosure; on the other sides lines parallel to these bounds. The axis of the fortifica tion would then be the Roman road running towards Lendal, and the Norman gateway of the abbey would be in the centre of the N.W. side. Like a Norman castle, Earlsborough would dominate the city.

Entries in Domesday Book of 1086 mention several dwellings as lying in the city ditch and refer to one of the seven shires or wards of York as laid waste for the castles. (fn. 21) Another dwelling had been incorporated in the castle during 1069 or 1070. The king's pool had destroyed two new mills and covered a carucate of meadow, arable, and garden ground, reducing its value from 16s. to 4s. The houses in the city ditch were possibly on the S.W. side of the fortress, where the stone footings of a timber building were found near St. Leonard's overlying the Roman ditch.

The earthwork defences of the city were known in the 12th century as Wirchedik, a name attested on the N.E., where St. Helen's church, later described as 'onthe-walls', lay in the Werkdyke, and on the N.W., where it is mentioned as the boundary of a property in Gillygate. (fn. 22) In Latin the term fossatum, sometimes qualified as vetus or regis, was normally used to describe them. The name Aldwark (the old fortification) for the street which runs from Goodramgate to Peasholme Green within and parallel to the N.E. side of the defences is derived either from the earthwork, or, as at Wroxeter, from still visible ruins of Roman walls protruding above the ground. (fn. 23)

Building in Stone

The recent excavations S.W. of Bootham Bar have shown that the heightening of the Danish bank to substantially the present form took place between the Norman Conquest and the early 13th century. This part of the defences is probably typical of the rest, but it need not be assumed that all the work was carried out at the same time. The operations of Geoffrey de Neville in 1215 were an episode in this long process of strengthening the earth defences. (fn. 24) This heightened bank, originally crowned with a timber palisade and strengthened with an outer ditch, was in turn capped by a layer containing pottery of the 13th and early 14th centuries, contemporary with the building of the stone walls.

There is no trace of stonework, except as rough revetments, in York's defences from the period between the Danish capture and the Norman Conquest, although in the boroughs of southern England there is increasing evidence for stone defences in the later part of this period. The best dated example is South Cadbury, fortified by Ethelred II in c. 1010 to concentrate the defences of the smaller boroughs of West Somerset. (fn. 25) Stone walls, securely dated to the later pre-Conquest period, were added to the Alfredian defences at Cricklade and Wareham. (fn. 26) A stone wall at Towcester is mentioned in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle as early as 921, but the phrasing of the reference makes it clear that this was exceptional. As far as is known, the castles erected at York by William the Conqueror were wholly of earth and timber. Stone gates associated with earthwork defences are, however, known in several early Norman castles, of which Exeter (c. 1070) and Restormel (c. 1100) may serve as examples.

In the Micklegate area the castle of the Old Baile lay at the S.E. end of the fortifications with its motte, Baile Hill, at the E. angle of a sub-rectangular bailey. The town defences formed a much larger trapezoidal enclosure defined by an earth rampart and ditch except towards the Ouse and the Old Baile (Fig. p. 58). No evidence is known for an earthwork blocking the gap between the Old Baile and the river. The city rampart was about 100 ft. wide and 25 ft. high, with an external ditch 50 ft. wide and 10 ft. deep. Its S.W. side is remarkably straight, with only one slight bend where it crosses the boundary between the parishes of St. Mary Bishophill Junior and St. Mary Bishophill Senior, one of the few indications of a possible earlier line of defences. The N.W. side has one noticeable change of alignment, on the crest of a rise opposite the railway station. The ground level within these defences was everywhere consistently higher than on the outside, partly due to a natural slope, but mainly caused by the build-up of occupation debris.

In the central area of the city the pre-Conquest defences were retained from St. Leonard's Hospital to the re-entrant angle in the rampart opposite Jewbury. An external ditch was probably added or deepened after the Conquest, and the bank heightened with the excavated material. At the E. angle of the Danish defences opposite Jewbury the Norman bank and ditch were continued up to the edge of the Foss in order to include St. Cuthbert's church. The gap in the rampart at the entrance to the Museum Gardens may have been left for the passage of the Roman road through St. Mary's Abbey grounds, continuing to the castle by Lendal (formerly Old Coney Street), Coney Street (the 'king's street'), Nessgate, and Castlegate.

The fishpond created by the damming of the Foss 360 yds. above its confluence with the Ouse and close by the new castle covered a wide area of marshy ground. This protected the heart of the city on the E. and made further defences on that side unnecessary. However, the suburb of Walmgate was soon protected by earthworks. There had previously been no early defences E. of the Foss: from the Roman period only two wharves beside the river and a few burials are known in this area. Although Fossgate and Foss Bridge existed before the Norman Conquest, and a settlement with several churches straggled along Fishergate, it was outside the Danish defences. The contract of 1345 for building the stone wall from Fishergate Bar to the Foss implies that the wall was to be built on an old earth rampart, and the existence in c. 1155 of a Walmgate Bar (fn. 27) suggests that this gate was on the line of the present walls.

The earliest post-Conquest masonry remaining in the defences is the outer arch of Bootham Bar, which can be dated to c. 1100 or even earlier. Similar arches, but of a rather later date, are found at Micklegate and Walmgate Bars; there was doubtless an equally early replacement in stone at the earlier Monk Bar, on the site not of the present gateway but of the Roman porta decumana, although scanty traces there are not closely datable. The stone arch of Lounelith, (fn. 28) later blocked and destroyed at the making of Victoria Bar, may also have belonged to this period. The 'bar below the castle', mentioned in a grant of 1232, (fn. 29) was perhaps a predecessor of Castlegate Postern, still set in earth and timber defences, but its location is uncertain.

The surviving remains of these 12th-century gateways indicate an outer arch forming the jambs of the gate, with side walls revetting the ends of the rampart against which they were built. The profile of the earth bank is particularly clear at Micklegate Bar, where it stood some 15 ft. high. The wall-walk would have been carried across the gate passage, probably on timbers. At Bootham Bar a second arch closing the inner end of the passage was built soon after 1150, and at Micklegate Bar a second stage, forming a small house above the passage, was added in 1195/6. It is probable that by the early 13th century all the four main gateways had been carried up one stage above the wall-walk. The phrase 'infra quattuor portas Eboraci' occurs as early as 1212 to describe dwellings within the city defences as distinct from the suburbs. (fn. 30) It suggests an established usage and probably refers to the new stone gates.

The replacement of the wooden palisade with a stone curtain wall seems to have begun only in the middle of the 13th century, when the rebuilding of the castle in stone was already well advanced. Earlier grants of tolls, such as that of 1226 for the enclosing of the city to guard and defend it, (fn. 31) are indefinite. Others, like the royal grant of timber in 1215, (fn. 32) clearly refer to the older fortifications. Moreover, casual references of this period mention the city mound in the Micklegate area. (fn. 33) The extensive work by Geoffrey de Neville in 1215, which destroyed houses beside the defences near Micklegate Bar and affected the Templars' mill below the castle, was apparently confined to widening the old outer ditch. (fn. 34)

During the twenty years ending in 1250 no grant of murage to the city of York is recorded in the Patent Rolls. From 1251, however, grants for a period of years become regular. Exemptions from payment of murage in York were given by the king to the Archbishop, Dean and Chapter, Templars, and Hospitallers in 1251, (fn. 35) in 1260 to the citizens of Lincoln, who were also building walls, (fn. 36) and in the same year to the burghers of Bruges, Douai, Ghent, St. Omer, and Ypres. (fn. 37) In 1267 the grant (for five years) specifically mentions the enclosing of Walmgate and the repair of the walls. (fn. 38) Murage was a tax granted for the fortification of a city, and so it can hardly be doubted that this long and continuous series of grants represents a sustained effort by the citizens to provide a stone curtain wall around the central area and the Micklegate district of York. The contrast between the stone walls and the mention of the enclosure of the street called Walmgate adjoining the city, where the masonry curtain dates from the 14th century, is significant. In addition, the erection of a stone wall surrounding St. Mary's Abbey, begun in 1266, according to the abbey's Chronicle, (fn. 39) implies that the city wall was already built in the central area (Fig. p. 58).

The completion by this date of the city wall in both the central and Micklegate areas is confirmed by several references. In 1268 the Dominican Friars' boundary was described as the city wall, instead of the mound, as previously. (fn. 40) Also in 1268 the Archbishop was granted land adjoining his palace and close to the wall, provided that he made gates by which the guards could approach the wall in time of war or commotion. (fn. 41) In 1285 royal permission was given to build walls 12 ft. high with gates and posterns around the Minster precincts, (fn. 42) in 1292 to John de Cadamo (Caen), prebendary of Driffield, to crenellate his houses within this close, (fn. 43) and in 1302 to William de Hamelton, the Dean, to fortify the Deanery. (fn. 44) Nothing remains of this wall around the Close, but one of the four gates still stands in College Street. The main entrance, High Minster Gates, remained until 1828 at the head of Lop Lane (now Duncombe Place), W. of St. Michael le Belfrey. Its main arch resembled that of Fishergate Bar and the smaller pedestrian arch was like that of Fishergate Postern. There were statue niches above and probably an upper stage, which had been removed by 1827.

An enlargement of the Dominican Friary grounds, proposed in 1298, in the ditch of the city wall, would have involved making a postern, but was apparently not effected. (fn. 45) In 1307 the friars unsuccessfully attempted to acquire Toft Green, stated by the citizens to be the only place within the city for the erection of defensive military engines in wartime and for assembling the people to show arms. (fn. 46) The change from an earth rampart to a stone wall as the main defence may also be illustrated by the name of a grantor of land near Lounlith in about 1250, John de Muro, son of Thomas de Fossato. (fn. 47)

An extension of St. Leonard's Hospital to the N.W. made in 1299 led to complaints by the citizens and consequent commissions of enquiry. In 1308–9 the hospital authorities were said to have appropriated part of the city's stone wall and ditch between St. Leonard's and St. Mary's Abbey, broken it down and carried off stones, and to have closed a public path by which the bailiffs used to approach the wall in order to survey and repair it. (fn. 48) This path apparently linked Blake Street and High Petergate.

In 1305 money collected from the murage was to be used by William de Skeldergate and Roger Basy the younger to build a wall along the Ouse beside Skeldergate. (fn. 49) This was a consequence of the royal licence granted in 1291 to the Franciscan Friars, allowing them to erect the still standing boundary wall to their precinct on the opposite side of the river. (fn. 50) This wall, the citizens claimed, had caused damage to property in Skeldergate, presumably by diverting the current to erode the W. bank. Also in 1305 the citizens petitioned the king to recover money from the murage after the mayor, Henry Lespicer, had been convicted for concealing £73 of it. (fn. 51)

The first curtain wall was probably quite low. Later repairs and rebuilding at many dates make it difficult to establish the original form. Opposite Jewbury, however, between Towers 32 and 33, the original battlements may still be seen on the outer face of the wall, encased in a subsequent heightening (Fig. p. 135). These indicate a wall-walk barely 6 ft. above the level of the rampart, with the top of the merlons originally rising to a height of 12 ft. This may be compared with the original height of the wall enclosing St. Mary's Abbey, 11 ft. to 12 ft.

The towers along this curtain have also been much altered and restored, but the semicircular and rounded ones, the most numerous of the three types of tower distinguishable at York, probably originated in this period. The early feature of a high, battered base occurs in Towers 7 and 11, and several other towers have late 13th-century characteristics.

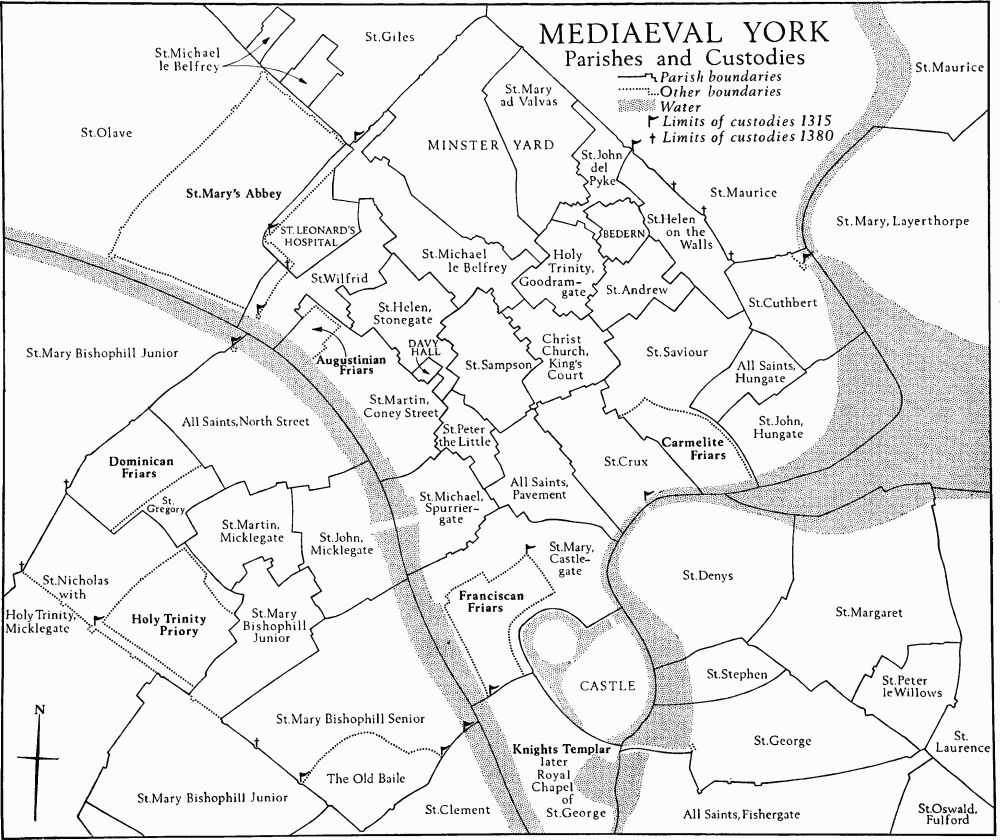

The first main building period may conveniently be reviewed in the light of the Custody of 1315. This document, dated in the ninth year of Edward II, during the mayoralty of Nicholas Fleming, is the first of a series of three preserved in the city archives. (fn. 52) It gives the arrangements for manning the walls in times of danger. The defences are divided into various sectors, allotted to the different parishes of the city.

Custodie Civitatis Eboraci

It may be noted that no provision is made for manning the defences of the Walmgate area, although the gate itself is allotted to four parishes in Walmgate; the survival of the old palisade in this area is proved from other records. (fn. 53) No inference can be drawn from the exceptional treatment of the Old Baile, as this occurs in the later documents; the walls along its ramparts were in fact not yet built. The entry for the Old Baile seems to be an addition in different ink. Of more importance is the treatment of those points where the walls came down to the Ouse. It is a possible inference from the use of the words a pede muri that two of the four towers from which the chains across the river were later suspended were not yet built.

The walls in 1315 were therefore complete for the whole of the Micklegate and central areas except for the Old Baile. This and the Walmgate area were still defended by the old wooden palisades. Most of the semicircular and round towers of the circuit had probably also been built, although the only towers mentioned by name are Ellerendyng, now known as the Multangular Tower, raised on the base of the W. angle tower of the Roman fortress, St. Leonard's or Lendal Tower, and Davy Tower.

The licence granted to St. Mary's Abbey in 1318 was to crenellate its precinct wall, provided that the length between the Abbey and the city was uncrenellated and not more than 16 ft. in height. (fn. 54) The purpose of this provision was clearly to prevent the city defences from being overtopped. It probably indicates the height to which the latter had by then attained, a height corresponding roughly to the present level of the crest of the battlements. This suggestion is borne out by the contract of 1345, (fn. 55) which provides for a height of 6 ells (22½ ft.), including the foundations. However, the com bined height of the rampart and city wall towards the Abbey is such that a wall over 30 ft. high would have had to be built in order to overlook the city's defences.

Some work on the walls was undertaken as a reaction to the raid by the Scots under the Earl of Moray up to the gates of York and the subsequent defeat of a force from the city at Myton-on-Swale on the 12 October 1319, involving the death of the Mayor, Nicholas Fleming. A grant of murage for ten years was made a week after the battle. (fn. 56) In 1321 the Dean of York was ordered by the king to stop hindering the collection of a tallage imposed by the mayor, bailiffs, and citizens to repair and strengthen the walls, ditches, and other defences of the city. (fn. 57) In December 1322 the king also issued a protection until the following Michaelmas to a party sent by the mayor and commonalty with four carts to carry stone for repairing the walls from Thevesdale quarry to the Wharfe at Tadcaster. (fn. 58)

In 1327 the mayor and bailiffs were ordered by Edward III to inspect the walls, ditches, towers, and ammunition, and were given full powers to take the necessary measures for the defence of their city. (fn. 59) The first question that arose concerned the Old Baile, the defences of which were considered to be inadequate. The citizens argued that it lay outside the city and should be fortified by the Archbishop, whose responsibility for its manning had been recorded in 1315, though the entry in the Custody is possibly an addition. The life of William Melton (archbishop 1317–40) by Thomas Stubbs, a nearly contemporary document, mentions that he enclosed the Old Baile first with planks 18 ft. long, and later with a stone wall. (fn. 60) The former work probably dates from the earlier years of his episcopate. The date of the stone wall may be given as c. 1330–40, after the dispute of 1327 (Fig. p. 88).

In 1345 the city took in hand the Walmgate defences and made a contract with a mason, Master Thomas de Staunton, for the construction of 20 perches of stone wall between Fishergate Bar and the Foss. (fn. 61) The specified height of 6 ells (22½ ft.) may be compared with the 18 ft. planks of the Old Baile's defences. The work was to be paid for at the rate of £7 a perch, and the provisions for payment assumed that it would be completed in about 2¼ years. A provision that, if stone or anything else useful for the work should be found in the foundations, Master Thomas was to have it without deduction, is clearly an allusion to the discovery of the buried Roman walls in the rampart of the central area, and perhaps also in the Micklegate bank, within living memory. The mason was also given an option on the future building of walls elsewhere in Walmgate on the same terms. The guarantor for Master Thomas was Henry de Percy, probably the second Lord Percy of Alnwick. The Percies owned property in St. Denys's parish, Walmgate, later known as Percy Inn. (fn. 62)

Composicio facta super operacione murorum in circuitu de Walmegate

Ceste endenture fet entre le Meire e la Communalte de la Citee Deverwyk dune parte e mestre Thomas de Staunton mason dautre parte tesmoigne qe lavauntdit Thomas fera vint perchez de mure de pere comensaunt a la porte de Fischergat e estendant vers leauwe de Foss suth le Chastel de Everwyk tantque les ditz vint perchez de mure soient parfourniz. Et serra chescon perche de sis auns en longure et sis en hautesce du primer pere en le found vers mount et le dit mure serra en espessere deinz la terre en le founde de ute peez et de amount la terre de set peez. tantque al alure du dit mur et serra le founde du dit mur pris et la hautesce fet solonc lordinaunce et avisement des ditz Meire et Communalte et del avauntdit Thomas. Et ceo qe defaute de chescon perche en hautesce soit parfourni en longure. Et les avauntditz Meire et Communalte grantent qe le dit Thomas et ses servauntz auerount fraunche entre et issu pur carier quantque appent au dit mure ou le dit Thomas e ses servauntz verrount greindre eisement et profist pur eux par reson Et serrount quites de tonenewes et murage et tous autres customes des toutes chosses appendauntz al dit overaigne. Et le avauntdit Thomas trovera totes maner des chosses queles appendent au dit mure ovesque le cariage de yceux. Et si nul avantage ysoit trove en celle partye en la found cum de pere ou autre chose appendaunt ala fesaunce du dit mure le avauntdit Thomas laura saunz rien abatre de ceo qil prendra pur loveraigne du dit mure. Et levaundit Thomas comencera a carier et ordeiner pur le dit overaigne a la Chaundelure prochein avenir apres la confeccion de cestes. Et pursuera le dit overaigne solonc ceo qe la seson del an demaunde. tantque sis perchez de mure de les avauntditz vint perchez de mure soient pleinement parfourniz. Et mesme celi Thomas par lui ou par son attorne auera e resceivera de la dite Comunalte dEverwyk al Escheker de la dit Citee des isseux et profitz du murage de la dite Citee par les mains des Coillours et Resceivours de ycele pur chescon perche de mure de pere septe livres dargent saunz nul ore resceivir, cest asavoir chescun Samadi vint south dargent. Le primer paiment comensaunt le Samadi prochein apres la feste de Seint Pere qest dit Ad vincula prochein avenir apres la confeccion de cestes e ensi de Samadi en Samadi tauntque de sept livers pur chescoun perche de mure quil auera fet soit pleinement paie. Et les ditz Meire et Communalte grauntent qe le dit Thomas ferra quanq ils auerount afaire de leure murs vers celles parties de Walmegat a mesme le pris cum de sus est dit. Si ne soit qe mesme celui Thomas ne purra salver ne tenir le un fesaunt la perche pur. vij. livers cum avaunt est dit. Et par cas si le dit Thomas soit occupe aillours issint qil ne soit demoraunt continuelment sur le dit overaigne, mesme celui Thomas ne serra pas chalange pur sa nonne reseantise issint tot foitz qe le dit overaigne soit bien avenauntment et fortement parfourni. Et les ditz Meire et Communalte volent e grantent qe tot largent qe serra promis et done en eyde du dit overaigne soit pleinement livere a dit mestre Thomas en paiement de ceo qil aura fait saunz rien retenir et nule parte ailliours mettre. Et ansi qil eyt chescun an une robe de la Communalte duraunt le dit overaigne. A quele overaigne en la fourme avauntdit fere et parfournir le avauntdit Thomas oblige soi ses heires et ses executors et touz ses biens quel part qils soient trovez. Et estre ceo le dit Thomas pur greigneur surete fere ad trove pur lui Mons. Henri de Percy plegg [f. 352] et enpernour del overaigne avantdit. Les queux Mons. Henri et Thomas a la une partie de cestes endentures. Et la dite Communalte a lautre partie entrechaungablement vnt mis leur seaux. Escrit a Eurewyk meskerdi apres la Feste de la Conversacion de Seint Poule lan du regne le roi Edward dEngleterre dis et neofym et de son regne de Fraunce sisme.

Translation

Agreement made for the building of the walls around Walmgate

This indenture made between the Mayor and Commonalty of the City of York of the one part and Master Thomas de Staunton mason of the other part witnesses that the aforesaid Thomas shall make 20 perches of stone wall beginning at Fishergate Bar and extending towards the water of Foss south of the Castle of York until the said 20 perches of wall shall be completed. And each perch shall be of 6 ells in length and 6 (ells) in height from the first stone of the foundation upwards and the said wall shall be in thickness underground on the foundation 8 feet and above ground 7 feet up to the wall-walk of the said wall and the foundation of the said wall shall be laid and its height determined according to the disposition and advice of the said Mayor and Commonalty and of the aforesaid Thomas. And whatever lacks from each perch in height shall be added to the length completed. And the aforesaid Mayor and Commonalty grant that the said Thomas and his servants shall have free entry and exit for carrying all that concerns the said wall wherever the said Thomas and his servants shall consider is to their greatest ease and profit. And they shall be quit of all dues (tonenewes) and murage and all other duties on all things belonging to the said work. And the aforesaid Thomas shall find all manner of things necessary for the said wall with their carriage. And if something of advantage be there found in this part in the foundation such as stone or other thing belonging to the making of the said wall the aforesaid Thomas shall have it without abating anything of what he is to have for the work of the said wall. And the fore said Thomas shall begin to carry (materials) and to organise the said work at the Candlemas [2 February] next to come after the making of these presents and he shall continue the said work as the season of the year allows until 6 perches of wall of the aforesaid 20 perches shall be fully completed. And the same Thomas in person or by his attorney shall have and receive from the said Commonalty of York at the Exchequer of the said City from the issues and profits of the murage of the said City at the hands of the Collectors and Receivers of the same for each perch of stone wall £7 of silver without receiving anything now—that is to say every Saturday 20s. of silver, the first payment beginning on Saturday next after the feast of St. Peter which is called Ad Vincula [1 August] next to come after the making of these presents [i.e. Saturday, 6 August 1345] and so from Saturday to Saturday until the £7 for each perch of wall which he shall have made are fully paid. And the said Mayor and Commonalty grant that the said Thomas shall build as much as they shall have to make of their walls towards the parts of Walmgate at the same price as is above said, so long as he the said Thomas may be able to keep and hold to making the perch for £7 as is before said. And in case the said Thomas shall be busy elsewhere so that he does not remain continually upon the said work he the same Thomas shall not be challenged for his non-residence so long as the said work shall be well conveniently and strongly completed. And the said Mayor and Commonalty will and grant that all the money promised and given in aid of the said work shall be fully delivered to the said Master Thomas in payment of what he shall have done without any retention or the putting of it anywhere else. And so that he have each year a robe from the Commonalty during the (continuance of the) said work. To the making and completion of which work in the form aforesaid the aforesaid Thomas binds himself and his heirs and his executors and all his goods wherever they may be found. And in this for greater surety the said Thomas has found Monsieur Henry de Percy as his pledge and guarantor for the aforesaid work. The which Monsieur Henry and Thomas to the one part of these indentures and the said Commonalty to the other part have interchangeably set their seals. Written at York Wednesday after the feast of the Conversion of St. Paul [25 January] in the year of the reign of King Edward [III] of England the 19th and of his reign in France the 6th [Wednesday, 26 January 1345].

The city wall from Fishergate Bar to Fishergate Postern, a length of some 500 ft. (about 22 of the 6 ell perches specified in the contract), is uniform at the base with a distinctive chamfered plinth and wellcoursed ashlar masonry. It has a large rectangular tower (39) at the projecting angle, of the same build as the wall, and a smaller added tower, also rectangular, between this angle and Fishergate Bar. This length of wall is no doubt the work of Thomas de Staunton.

Grants of murage are almost continuous throughout the long reign of Edward III, but few other references to the defences are preserved. In 1343 a commission was set up to check the accounts of the collectors of the murage after fraud had been alleged. (fn. 63) In 1394 Thomas del Abbay left £10 to the mayor for the repair of the walls. (fn. 64) During the later 14th century the walls must have reached their present extent and plan, including the addition of many flanking towers of rectangular and polygonal form, the completion of the four great gatehouses, and the provision of chains to close the river Ouse. These chains stretched between Lendal and Barker Towers, and between Davy Tower and the Crane Tower.

Details of the defences in the reigns of Richard II and Henry IV are given in the two later Custodies. Only a part of the text of the first, of 1380, is given here, omitting the names of the constables and subconstables. (fn. 65) The Custody of 1403 (dated Saturday 21 July, 4 Henry IV, when William Frost was mayor) (fn. 66) differs only in the names and numbers of the constables and sub-constables, of whom over twice as many are listed as in 1380, and in a few other details. The most important additional information is given below in brackets. This later document also lacks an entry for the Old Baile.

The Custody of the Walls, 1380

Iste custodie cum constabulariis [names omitted] arainiate et ordinate fuerunt tempore Johannis de Gysburn, maioris Eboraci, et Willelmi de Cestrie, clerici communis, die Veneris in festo Sancti Laurencii Martiris, Anno regni Regis Ricardi secundi post conquestum quarto.

Mediaeval York Parishes and Custodies

Translation:

These custodies with the constables were drawn up and ordained in the time of John de Gysburn, mayor of York, and of William de Chester, common clerk, on Friday, the feast of St. Lawrence the Martyr, in the fourth year of the reign of King Richard the second after the Conquest (10 August 1380).

From 1400 to the Civil War

The city's licence to levy murage was renewed wellnigh continuously until 1449 (fn. 67), but little is otherwise recorded concerning the defences before the late 15th century, largely because of the incompleteness of the York archives until the reign of Edward IV. The few surviving references indicate that regular repair work continued throughout the period. Thus in 1442 20½ tons of stone were bought for Fishergate Bar, (fn. 68) and in 1450/1 a new gate was made there. (fn. 69) In 1453 £7 11s. 8d. was spent on the walls between Davy Tower and Layerthorpe Postern under the direction of Robert Couper, the Common Mason. (fn. 70) In the following year £12 16s. 2½d. was expended and iron was bought to repair the chain by which the Ouse could be blocked at Lendal. (fn. 71) Planks were also needed to pass between the towers, indicating that no continuous wall-walk existed.

Murage rolls, presumably the survivors of an annual series, are extant for the two years 1442–3 and 1445–6. (fn. 72) These rolls record not only the income from the tolls collected at the four bars and from the traffic on the river Ouse ('muragium aque dUse'), but also the annual expenditure on the defences. The tolls were farmed out in return for fixed quarterly payments, and two-thirds of the amount collected came from the farmers of the murage at Micklegate Bar and on the Ouse. In the earlier roll details are given of work costing £16 18s. 3d. and occupying some 18 weeks, set against receipts of £22 11s. 6½d. It includes a payment of 10s. for the letters patent issued in 1442 confirming the right to collect murage. Building work or repairs were being carried out at Fishergate Bar and by the king's ditch at Talkan Tower. John Ampilford, a freeman of York in 1413 and Searcher of the Masons' Guild in 1419 and 1442, was the mason employed. In 1445–6 only £3 16s. 2d. was spent from an income of £26 8s. 9d., mostly on payments to the gatekeepers and on the salary and gown for Robert Couper.

Details of the murage receipts are known for the years 1450–4: (fn. 73) in 1450/1 £16 2s. 5d. was collected. Payments to the gate keepers are also recorded in the same account book, with the bars or portae distinguished from the posterns; Fishergate Postern is called 'posterna iuxta ecclesiam Sancti Georgii' and North Street Postern is not mentioned. In 1463, during the civil war, repair of the walls, overhaul of the city's guns and the purchase of gunpowder were ordered; (fn. 74) this is the first mention of guns. In 1468 the foundations of a tower were repaired. An order was made in 1482 for 'bumbylls, netylls, and all oder wedys' growing round the walls to be pulled up. (fn. 75) In 1484 the city was grateful to Richard III for releasing York from the payment of the fee farm and for granting an annual £60 for the relief of the city's poverty, and for the repair and maintenance of the walls. (fn. 76) He had already granted £20 for the same purpose. (fn. 77) His defeat and death soon afterwards, however, left this grant in doubt. Negotiations with Henry VII about its continuance went on for some years.

The new king was clearly anxious that the defences of York should be put into good repair. His concern is shown by a series of letters to the Mayor and Corporation, resulting in much work on the defences. In 1486 the Recorder had advised the city council to spend money on repairing the walls, (fn. 78) but in 1487 the Mayor, William Todd, wrote to the king that the city was so greatly decayed both by the collapse of the walls, and by Richard III's part demolition of the castle (in preparation for rebuilding), as to be incapable of defence. (fn. 79) The population had been halved and there was poor provision of ordnance. The king, who had visited York in the previous April, instructed the constable of Scarborough Castle to supply the city with 12 serpentines (light cannon), but there were too few at Scarborough to carry out this order. (fn. 80) Soon afterwards the leaders of Lambert Simnel's rebellion tried to win over the city, and a force under the Lords Scrope of Bolton and of Upsall attacked Bootham Bar but was repelled. (fn. 81) After his victory over the rebels at Stoke Field the king again visited York and knighted Todd for his loyalty. Some work was done at this time on the walls of the Walmgate area since Sir William set up three inscriptions on or near Fishergate Bar recording that he had rebuilt 60 yds. of wall at his own expense.

In May 1489, however, rebels under Sir John Egremont and John Chambers burned Fishergate and Walmgate Bars and occupied York. After their defeat Thomas Wrangwysh, alderman and warden of the Walmgate Ward, was reprimanded for not keeping the two gates in adequate repair. (fn. 82) As a result of this attack the king urged that the defences be repaired, and a collection for this purpose was ordered by the city council. (fn. 83) Outer gates of iron and, where necessary, drawbridges, were to be added to the bars and posterns. Sir Richard Tunstall spent £40 out of taxation on repairs, (fn. 84) but in 1491 the king was still ordering the walls and ditches to be overhauled and guns and powder to be obtained. The Mayor promised to do this, but stressed the city's poverty, and the king granted £98 so that York should be fortified with guns, gunpowder, and other equipment. (fn. 85) In 1493 the Mayor ordered the preparation in every ward of ordnance and other material, including gun stones, gunpowder, and portcullises. (fn. 86)

At this time work was in progress at a new tower. In September 1490 two masons were committed to prison for breaking tools belonging to tilers working there. (fn. 87) The alleged murder of a tiler, John Patrik, by two masons resulted from the same quarrel, a result anticipated by the tilers, who had previously asked the city council for protection against murder or mutilation threatened by the masons. (fn. 88) It is probable that the tower involved was the Red Tower, since this is largely built of bricks and is of this period. The masons, led by William Hindley, no doubt resented work on the walls, which they thought to be their prerogative, being handed over to tilers. Bricks were also used at this time to block the main arch of Fishergate Bar, because, although comparatively new, it was so badly damaged by the rebels that it had to be built up; so it remained until its reopening in 1827.

Extensive work on the defences, especially of the Walmgate area, continued for the next twenty years. In 1496 three fines totalling £25 were assigned to this purpose. (fn. 89) During 1501/2 'a pece of the citie wall of the length of c fote betwixt Walmegate and the water of Fosse was anewe maid out of the ground and another pece there off di c fote long was taken down and newe set up agayn'. (fn. 90) The sum of £14 14s. 10d. was paid for this work, (fn. 91) and Robert Symson, one of the Chamberlains, was exempted from serving as a sheriff for four years because of his good work, especially about building the walls in Walmgate. (fn. 92) It is possible that the new stretch of wall was erected to connect the Red Tower with the curtain wall which already existed.

In 1502 'it was determyned that ther shalbe a substanciall posterne maid at Fyschergate which now is closed up an by reason thereof aswell the stretts and beldyngs within the wallez as without ar clerly decayed and gon down'. (fn. 93) Since Fishergate Bar remained walled up this decision apparently resulted, not in its reopening, but in work at Fishergate Postern, including a large new tower built in about 1505 to replace the earlier Talkan Tower. (fn. 94) In 1506–9 £30 10s. was spent on the walls between Walmgate Bar and the Foss, expenditure which may cover work on one of the two new terminal towers of the Walmgate walls. (fn. 95)

It seems likely that the wall-walk supported on internal arches between Monk Bar and Layerthorpe Postern and near the Red Tower (Pl. 45) was added during this period, although there is no direct documentary proof of this. The arches are of a late mediaeval type appropriate to the reign of Henry VII and already existed in 1634. (fn. 96) Similar arcaded wall-walks at London and Tenby are late 15th century in date. The top storey of Monk Bar, which on architectural grounds is a late 15th-century addition, may also have been built on this occasion.

A fresh dispute had meanwhile arisen between the city and St. Mary's Abbey over ground in Bootham. In 1497 the monks, expecting a royal visit, had built there a new postern and tower (the Postern Tower and 'Queen Margaret's Arch'). There was a long correspondence between the Mayor and the Abbot; the citizens threatened to pull down the new work. (fn. 97) In 1506 the citizens also complained that the infirmary of St. Leonard's Hospital had encroached on the city wall. (fn. 98)

In 1511 thirteen guns of assorted types were delivered to the officers of each ward to be set on the four main gates, at Castlegate Postern, and at the Red Tower. (fn. 99) These were presumably the equivalent of the serpentines ordered in 1487. In the city House Book for 1510 there is a detailed scale of the tolls exacted for murage on goods entering the city. (fn. 100) Sums from ¼d. to 6d. were collected for a variety of imports, ranging from corn, meat, herrings, garlic, and wine, to coal, nails, millstones, wood, and oil. In spite of this income and the heavy expenditure on the defences, however, the Mayor could complain in 1521 that a great piece of the N. walls had fallen, (fn. 101) and the ruinous condition of the walls was stressed in 1527 when the Muremasters were elected. (fn. 102)

In 1536 the city made no resistance to the forces of the Pilgrimage of Grace; Robert Aske, the Pilgrims' captain, was hanged on Clifford's Tower in the following year. King Henry VIII visited York in September 1541 to make certain of the city's submission and loyalty. He had already strengthened the Council in the North, set up in 1484 and, since 1539, having its permanent seat in the dissolved St. Mary's Abbey, so that the central government might more closely supervise the area. Micklegate Bar was cleaned for his visit and decorated with wood and canvas turrets bearing the royal arms (fn. 103) since the king was expected to approach from Tadcaster; in fact he entered by Walmgate Bar. Repairs to the walls and to the Red Tower had been authorised in May 1541. (fn. 104)

At about this time Leland wrote the first surviving account of the defences. (fn. 105) He had visited York in 1534, and in the first part of his description mentions St. Mary's Abbey and three friaries as still existing. Later, however, he refers to Holy Trinity Priory, the Dominican Friary, and Clementhorpe Nunnery (dissolved 1536–9) in the past tense. His account can therefore be taken as giving the state of the defences in about 1540.

'The towne of Yorke stondith by west and est of Ouse river, renning through it: but that part that lyith by est is twis as great in buildings as the other.

Thus goith the waul from the ripe of Owse of the est parte of the cite of York.

Fyrst a great towre with a chein of yren to caste over the Ouse: then another tower, and so to Boudom gate: from Boudom bar or gate to Goodrome gate or bar x. towres. Thens 4. towres to Laythorp a posterngate: and so by the space of a 2. flite shottes the blynde and depe water of Fosse cumming oute of the forest of Galtres defendith this part of the cyte without waulle. Thens to Waume gate 3. towres, and thens to Fysscher gate stoppid up sins the communes burnid it yn the tyme of King Henry the 7. Sum say that Waume gate was erectid at the stopping up of Fysscher gate: but I dout of that. And yn the waul by this gate is a stone with this inscription: LX yardes yn length Anno D. 1445 [recte 1487] William Todde mair of York did this coste.

Thens to the ripe of Fosse a 3. towres, and yn the 3. a posterne. And thens over Fosse by a bridge to the castel. Fosse bridge of [5] arches above it: Laithorpbridg of 3. arches. Monke bridge on Fosse of 5. arches withoute Goodrome gate.

The area of the castelle is of no very great quantite. There be 5. ruinous towres in it.

The arx is al. in ruine: and the roote of the hille that yt standith on is environid with an arme derivid out of Fosse water....

The west part of the city of York is thus enclosid: first a turret, and so the waul rennith over the side of the dungeon of the castelle on the west side of Ouse right agayn the castelle on the est ripe. The plotte of this castelle is now caulid the old baile and the area and diches of it do manifestly appere. Betwixt the beginning of the firste part of this west waulle and Michel gate be a xi. towres, and at the lower tower of the xi. ys a posterne gate: and the towre of it is right again the est towre to draw over the chaine on Owse betwixt them.'

Leland's circuit of the walls starts at Lendal Tower, and his mention of the chains for blocking the Ouse is interesting, since in 1553 the city council decided that 'the iron Cheans at the Towre at the lait Gray Freres wall and other place shalbe sold to the Comon profett of this Citie'. (fn. 106) In 1569 the rebellion of the Earls of Northumberland and Westmorland caused urgent preparations to be made for defending York. (fn. 107) The posterns were blocked by 'contre mures of earth or stone', bulwarks were made at St. Leonard's Landing and at the landing opposite it by order of the Lord Lieutenant, the walls were repaired, ditches were scoured, ladders brought in from the suburbs, boats secured, guns were overhauled, and many other precautions were taken. Fortunately the expected attack was never made, and in the following spring the city council could return the planks and boards which it had borrowed 'to be layd apon the citie walls for defens and watch', and could compensate their owners for those which were 'cutt, peryshed or wontyng'. (fn. 108)

In the later 16th century the city records have many references to the walls, so that there is evidence for such details as the widening in 1573 of North Street Postern 'so that my Lord President's great horse may passe through the same', (fn. 109) and for the lease in 1580 to the same Lord President of the Council in the North, the Earl of Huntingdon, of part of the outer ditch near Bootham Bar; he wanted to build pillars or buttresses on it as part of his new work at the King's Manor. (fn. 110) In 1577 Monk Bar was made into a prison for freemen, (fn. 111) and in 1584 Fishergate Bar was cleared of poor folk to serve as a house of correction, holding recusants, and lunatics. (fn. 112) In 1580/1 repairs to the walls near Layerthorpe Postern and Micklegate Bar cost £43. (fn. 113) A regulation of 1584 orders that those occupying the ramparts should cut, scour, and clean the ditches to a width of 4 yds. and to a depth of 1 yd. (fn. 114)

Not all work on the defences was purely utilitarian: the accounts for 1584/5 show that £3 was spent in decorating Walmgate Bar with the Queen's arms, carved in wood and painted, with two shields of the city arms, a wooden lion, three painted iron weathervanes, and glass windows. (fn. 115) Heavy expenditure at this time on Bootham, Micklegate, and Walmgate Bars was almost certainly due to the construction of similar timber-framed houses on their inner façades. (fn. 116)

The castle, partly demolished by Richard III in anticipation of reconstruction which was never carried out, was by this time very dilapidated. In 1582 money was collected by the county justices to repair the hall, gatehouse, and bridge. (fn. 117) The gaoler's attempt in 1596–7 to demolish Clifford's Tower and to sell the stone for his personal profit was frustrated by protests from the city before he had done more than remove the battlements and roof. Interestingly, these protests were on grounds of amenity rather than because of the value of the tower as a fortress, and one petition stresses that if it were pulled down York would have no buildings left for show other than the Minster and the church steeples. (fn. 118)

Normal maintenance work on the defences of the city was carried on up to the Civil War. In 1594 a committee was appointed to search for fallen coping stones, and many were discovered in premises adjoining the Micklegate defences. (fn. 119) Holy Trinity Priory church was the source of stone used for repairs near Lendal in 1603, and a watchman was hired in case plague-infected strangers entered the city through the gap in the wall which was being repaired. (fn. 120) Precautions were also taken against plague in 1631, when posterns and places where the walls could be climbed were checked. (fn. 121) James I's visit in 1603 was prepared for by washing and painting the bars and setting up a stone figure over Micklegate Bar. (fn. 122) In 1616 Lendal Tower was first used as a waterworks, a use later to become permanent. (fn. 123)

During the Civil War

The city was the principal base of the royal army assembled in 1640 to fight the Scots, and fortified camps were constructed to the W. and S.W. The king did not follow Lord Herbert's advice that York should be strengthened at the citizens' expense, 'that at the distance of every twenty five score paces round about the town, the walls should be thrown down, and certain bastions or bulwarks of earth be erected by the advice of some good engineer', and that all houses within 'twenty five score paces round about the wall' should be demolished. (fn. 124)

When the Civil War started in 1642 Henry Clifford, Earl of Cumberland, in command of the royal forces in the north, had the city walls repaired and additional earthworks made. A labour force of 1800 was set to work, and the city council complained of the great expense involved in making trenches and of the felling of trees and hedges around the city. (fn. 125) Clifford's Tower was also restored, apparently at the Earl's own expense, since he claimed the supposed right of his family to be its hereditary captains.

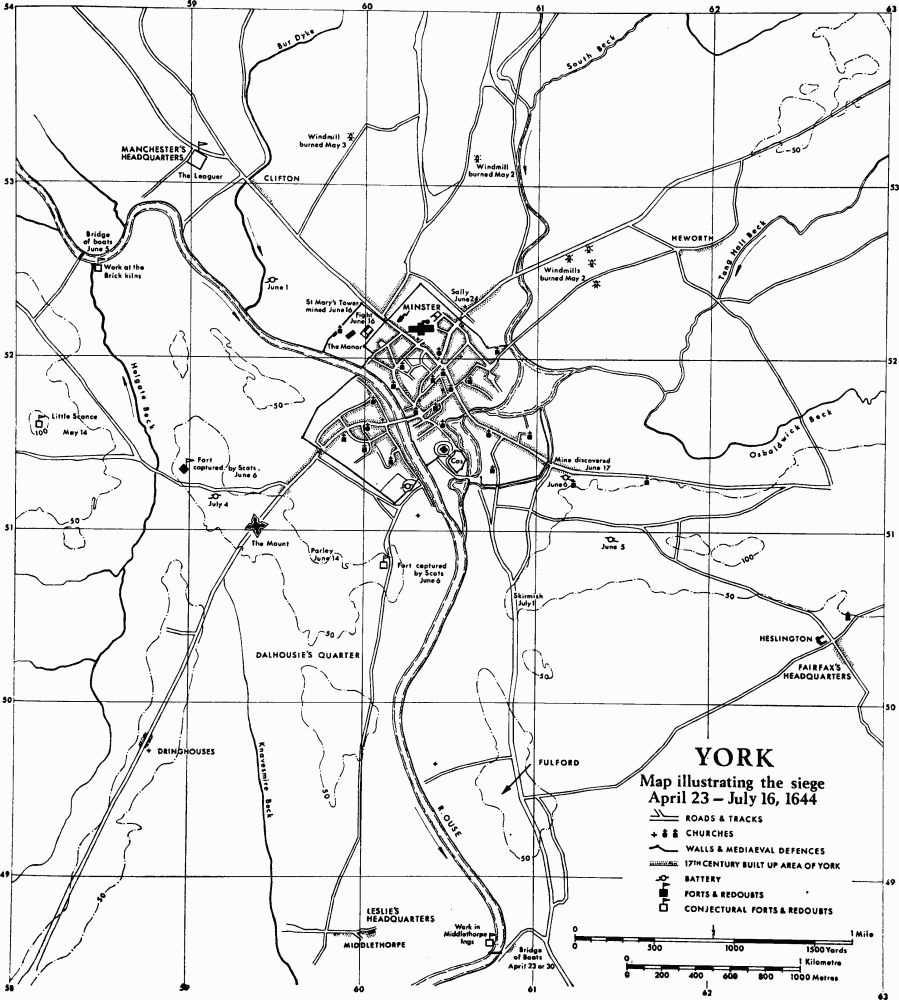

Cumberland was replaced in November 1642 by the Earl of Newcastle, with Sir William Savile serving under him as Governor of York. The new commander unsuccessfully beleaguered the Parliamentary stronghold of Hull, but in April 1644 the advance of a large Scottish army under the Earl of Leven, together with the defeat and capture at Selby of Sir John Belasyse, who had succeeded Savile as Governor of York, forced Newcastle to retreat to York, where he was besieged from 23 April. (fn. 126)

Details are known of the regulations for rationing in the city and of the price of provisions during the siege. (fn. 127) The arrangements for defence included blocking all the posterns with earth and stones and mounting cannon. There were two cannon on each of the four main gates and on Baile Hill, three on the roof of Clifford's Tower, one at the Friars (probably on the Greyfriars' Wall), three in boats moored across the Ouse near the site of Skeldergate Bridge, and 'a platform of guns' on the roof of St. Olave's Church. (fn. 128)

The Scottish army encamped on the S. of York, while Lord Fairfax, who had advanced from Hull, took up a position on the S.E., but the combined forces were still too few to blockade the city completely. Diaries kept by Robert Douglas, chaplain to Leven, and by Sir Henry Slingsby within York, enable the course of the siege to be followed day by day. (fn. 129) In spite of successes in skirmishes outside the walls, however, the besiegers seem to have made little progress during May. On the 2nd they burned the seven windmills on Heworth Moor and later destroyed three mills N. of the city. On the 13th they captured St. Nicholas' church outside Walmgate Bar, taking 80 prisoners, and on the 14th they stormed and slighted a small sconce near Acomb. A general assault on the walls from all sides was contemplated, using the dismounted cavalry as infantry. (fn. 130) The Royalists made sorties on 19 and 30 May and on 1 June, when the Scots captured some 60 cattle and horses grazing outside Micklegate Bar.

York Map illustrating the siege April 23 – July 16, 1644

On 3 June the army of the Eastern Association under the Earl of Manchester arrived and encamped around Clifton, bringing the number of the besieging forces up to about 23,000 infantry, 7,000 cavalry, and 600 dragoons, with 25 guns, as against 4,500 infantry, 300 cavalry, and 35 guns inside the city. More information is available on the course of events after Manchester's arrival from newsletters sent to London by Simeon Ash and William Goode, chaplains in his army, and published in instalments. (fn. 131) Several letters also survive for the next month of the siege. Thus an important episode may be described in as many as ten different contemporary sources. There is even a Latin epic poem on the siege and on the battle of Marston Moor, written by Payne Fisher, a former Sergeant-Major, and published in 1650. (fn. 132)

A sally by the Royalist cavalry towards Scarborough was beaten back on 3 June, and two days later Fairfax's forces built a five-gun battery on Lamel Hill, 650 yds. S.E. of Walmgate Bar. Although the movement of a 60 pounder cannon from Fulford to this battery was delayed by fire from Clifford's Tower, the guns there were soon bombarding the Walmgate sector. (fn. 133) Meanwhile Manchester's forces had built a bridge of boats across the Ouse near Clifton as a link with the Scots, just as a month earlier the Scottish army had built one near Acaster Malbis to provide communication with Fairfax's troops. On 6 June another battery was made in St. Lawrence's churchyard outside Walmgate Bar, and at about midnight the Scots attacked the earthwork forts forming an advanced position to the S. of the city, and captured two of them, those on Holgate Hill and Nun Mill Hill. They failed to take the central fort on the Mount, which held out until the end of the siege.

On 7 June the Royalists, now that most of their outer defences had been lost, burned the suburbs outside the gates on the N., E. and W. On the following day the bombardment damaged Walmgate Bar and a 60 lb. ball went through the tower of St. Sampson's church. (fn. 134) At about this time a mine being made under Walmgate Bar was discovered through the questioning of a prisoner and was frustrated by countermining. (fn. 135) Messengers who reached the city disguised as women probably brought news that the king had ordered Prince Rupert to relieve York. (fn. 136) In order to delay the besiegers while relief approached, Newcastle opened negotiations on 12 June. On the 14th he rejected the terms offered and the siege was pressed on with the bombardment by Manchester's forces of the precinct wall of the Abbey and the explosion of a mine under St. Mary's Tower on 16 June. (fn. 137) This was not co-ordinated with other attacks and, although troops commanded by Lawrence Crawford entered by the breach and penetrated as far as the King's Manor, they were beaten back with the heaviest casualties of the siege, 216 captured and 40 killed, a disaster which disheartened the besiegers.

Little seems to have happened for the next fortnight, and Fairfax, writing to London for more money and ammunition, reported that his men were ready to mutiny. (fn. 138) The Royalists signalled to Pontefract Castle from the Minster towers and on the 24th made an unsuccessful sally from Monk Bar. On 30 June Prince Rupert's army arrived at Knaresborough, and the besieging armies moved off to Marston Moor, hoping to block his approach. However, he marched to the N.E., and on 1 July encamped a short distance N. of York. The relieved garrison were able to plunder the abandoned Parliamentary camps and found there 4,000 pairs of boots, three mortars, and ammunition. (fn. 139)

On 2 July Newcastle's forces combined with Rupert's but were heavily defeated on Marston Moor. As a result Prince Rupert retreated towards Lancashire, while Newcastle fled with other Royalist leaders to the Continent by way of Scarborough. The siege was resumed on 4 July, and the victorious Parliamentary armies made new batteries in Bishop's Fields, S.W. of York, and between Walmgate Bar and Layerthorpe Postern. A tower, probably Tower 13 at the Toft Green angle, was shot down. (fn. 140) Preparations for storming the city were made, including the collection of ladders, the making of a bridge to throw over the Foss, and the storing of hurdles. The point selected for attack was 'where by ye Laterne (Layerthorpe) Posterne it was most easy, having nothing but ye ditch with drought almost dry for to hinder their entrance'. (fn. 141) Sir Thomas Glemham, now the Governor, asked for a parley on 11 July, and negotiations continued for four days.

The city was surrendered on 16 July on terms favourable to the garrison: the Royalists were able to march out with the honours of war and make their way to Skipton. The victorious armies did not stay long, but moved away on the 20th, leaving Lord Fairfax in control of York. He was succeeded as Governor in 1646 by Colonel-General Sydenham Poyntz, and Sir Thomas Dickinson, Lord Mayor in 1647 and 1657, replaced Poyntz. Later Robert Lilburne, one of the MajorGenerals, commanded the garrison.

For the rest of the Civil War the city was no longer involved in active warfare. On 1 August heavy guns used by the besiegers were sent for, to be employed against Sheffield Castle, (fn. 142) and in September a mortar left by Prince Rupert, together with 30 shells, was requested for the siege of Lathom House. (fn. 143) Repairs to the defences started in February 1645, when Edmund Gyles, the newly elected City Husband, patched the wall at the angle of the Old Baile and built a brick and stone watch house there. (fn. 144) He then built a gun platform and guard house at Toft Green and a brick watch house beside Walmgate Bar. (fn. 145) A similar watch house was proposed at Skeldergate Postern, where the 'pallisadoes' blocking the river were removed. (fn. 146) Later in the year Castlegate Postern was unblocked and its portcullis made operational; (fn. 147) the walls at Fishergate Postern were also repaired, and the ditch around the Red Tower was enlarged. (fn. 148)

During the spring of 1645 some of the outer earthwork defences were slighted, when the inhabitants of Rufforth, Knapton, and Hessay were set to 'demolish the worke in Houlgate and the brestworke in Bisshopfeilds', those of Moor Monkton to level 'the worke att the Brickillnes in or neare Holegate Feilds', and the villagers of Acaster Selby 'to demolish the worke in Middlethorpe Inggs'. (fn. 149) For restoring the dam at the Castle Mills, damaged in February 1643 in an attempt to divert the Foss into the city ditch, every householder in St. Sampson's and St. Saviour's parishes was 'to send an able person with spades or shovels to worke there' and 12 men were also to be hired to dig. (fn. 150)

Walmgate Bar had been considerably damaged: work on its restoration commenced in October 1645 with the filling up of the mine beneath it. (fn. 151) To pay for the various repairs £300 had already been raised in York in 1644, but by April 1646 a further £117 had been spent on the walls, and there were still 'great decayes and Breaches in Walmegate Barr, the coveringe of Bowtham barr, the Comon Hall, the Castle Milne damme, and other parts of the cittie wall, the repaireinge whereof will require a greater some than at present can well be rased in this Cittie'. (fn. 152) The city's M.Ps were to see 'if the Parliament will alow anythinge towards the said repayres'. Their attempts were successful, for on 3 October the House of Commons ordered that repairs of the walls, gates, and bridges should be financed by fines on Royalists, and on 12 November a warrant was issued to pay £5,000 from this source. (fn. 153) This sum, which included £400 from Sir George Wentworth's estates at Oulston, (fn. 154) was not necessarily all collected, but nevertheless enabled the damaged Bars to be repaired in 1647 and 1648, (fn. 155) as the date on the Walmgate barbican confirms. Layerthorpe Bridge, however, was not finally repaired until 1655, when a stone arch replaced temporary planks. (fn. 156)

During the renewed hostilities of 1650 and 1651, Gyles was ordered to block the paths along the river banks beside the terminal towers of the city wall, made easier of access by the low level of the river; watch at the posterns was also increased. (fn. 157) In October 1651 he was instructed to store deal and timber from the battlements of the Bars, presumably temporary strengthening during the emergency, and Alderman Dickinson, the Governor, was to be consulted on the disposal of the guns. (fn. 158) Clifford's Tower had also been repaired after the siege and housed an infantry garrison, partly supported by the citizens. (fn. 159) In August 1650, however, soon after a visit by Cromwell, '3,000 unfixed muskets in Cliffords Tower at York, and divers unserviceable pieces of ordnance in the castle yard, and at the several ports of York' were removed to Hull. (fn. 160) In 1652 brass cannon still remaining in the city were also sent to Hull. (fn. 161) The garrison of York under Lilburne surrendered the city to Lord Thomas Fairfax on 1 January 1660, an important step towards the restoration of the monarchy.

Damage to the city within the walls during the siege was apparently mainly caused by shots aimed at Clifford's Tower from the battery on Lamel Hill. The spire of St. Denys' church was pierced by a cannon ball, so was the tower of St. Sampson's. Most of the mortar shells fired from the Walmgate side of York fell into the Foss, but one landed in the Thursday Market (St. Sampson's Square), killing a girl and damaging the old market hall. A vivid description of cannon balls coming through the Minster windows during services and bouncing from pillar to pillar is unconfirmed, (fn. 162) and Sir Thomas Fairfax made a point of protecting the cathedral, even 'by making it Death to level a Gun against it'. (fn. 163) The ruin of St. George's church, ascribed to the bombardment by one writer, (fn. 164) was probably not due to any enemy action.

Outside the city the churches of St. Nicholas, St. Lawrence, and St. Maurice were wrecked, and the first of these remained in ruins. Ingram's Hospital in Bootham, Agar's Hospital in Monkgate, and the Free Grammar School in Gillygate were all ruined and needed rebuilding. The only houses outside the walls which were not destroyed by the Royalists to prevent the besiegers using them as cover were apparently those near Micklegate Bar, preserved by the continued resistance of the fort on the Mount. Many windmills, all no doubt wooden post-mills, were also burned in the siege.

The finds of cannon balls, mortar shells, and bullets made in recent times were all in the chief areas of fighting, namely, on the Mount, near Nun Mill, at the foot of Lamel Hill, and at Walmgate Bar. Bullets recovered from the inner face of the Abbey precinct wall must have been fired in the fighting of 16 June 1644. A cannon ball found embedded in the city wall near Micklegate Bar during restoration would have come from the Scots' artillery.

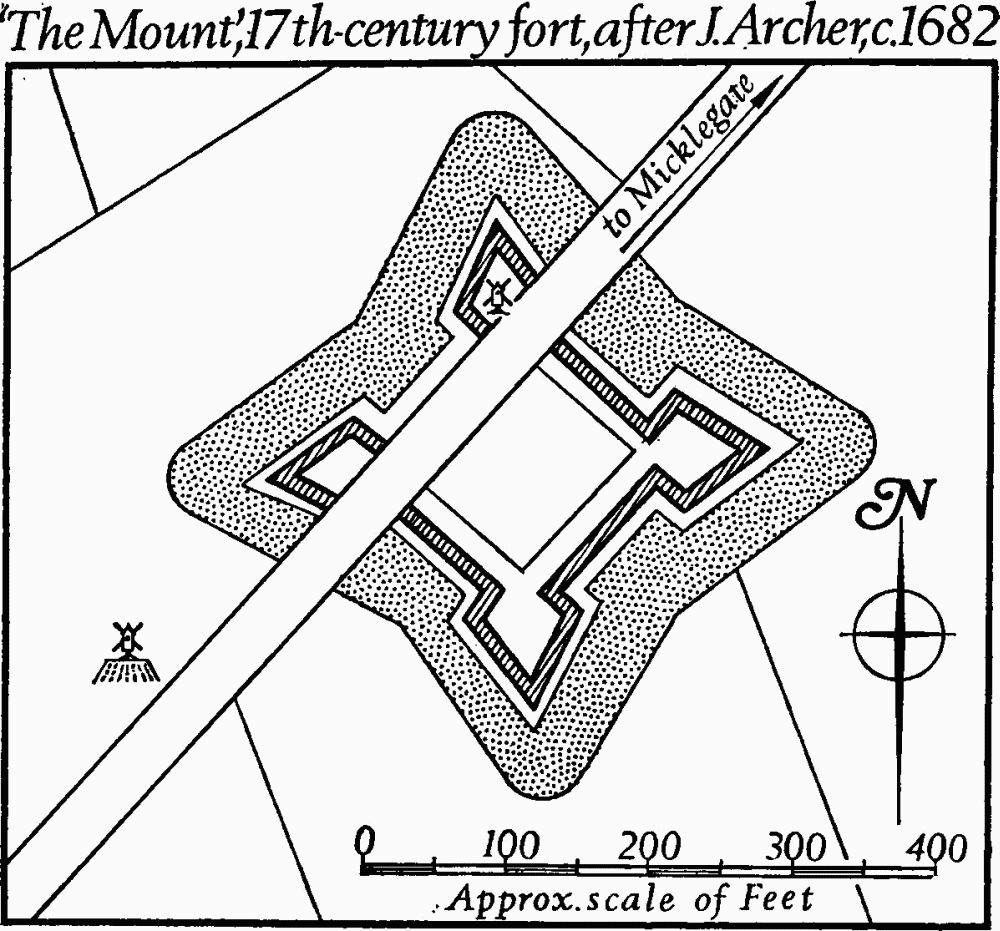

Little now remains of the earthworks mentioned in accounts of the siege. The best attested of these are three forts erected by the Royalists to the S.W. of the city, on the Mount, on Holgate Hill, and on Nun Mill Hill, and the Parliamentary battery on Lamel Hill. There were also works at the brick kilns near the confluence of the Holgate Beck with the Ouse, and in Middlethorpe Ings, demolished in 1645. No plans of the siege are known to exist which might reveal if the few references to trenches and lines of circumvallation mean that there were continuous lines, as at Newark.

'The Mount', 17th-century fort, after J. Archer, c. 1682

The sconce on the Mount (NG 59385107) straddled the main road from Tadcaster. (fn. 165) It was constructed in 1642–3 over the site of a Roman cemetery and near the remains of St. James' Chapel. Timber revetments were removed in 1649 (fn. 166) and the disused earthwork became the site of a windmill, remaining fairly complete until 1742, when it was partly levelled for road widening. The last vestiges were destroyed in the present century. Archer's plan of c. 1682 (Pl. 60) shows that it was a regular quadrilateral with angle bastions and a wide ditch. In plan and siting it closely resembled the surviving Queen's Sconce at Newark-on-Trent, but was only two-thirds the size. At the surrender it was described as 'a curious and strong work', (fn. 167) and by William Stukeley in 1725 as 'a great sconce a little way off York called the Mount, consisting of four bastions raised in the civil wars'. (fn. 168)

The fort on Holgate Hill (NG 58955133) remained visible until recently, but only shapeless fragments remain in the gardens of houses in Enfield Crescent, which occupies its site. It was planned by Benson in 1904 and excavated in 1936 by the late Philip Corder. (fn. 169) A slight rampart 25 ft. wide and 3 ft. high with a feeble internal ditch enclosed a rectangle 160 ft. by 148 ft. The summit of the hill bore a small patch of cobbling and 14th-century occupation debris. Ridges and furrows indicated ploughing of the earthwork. In plan it resembled redoubts constructed by the Scottish army around Newark, like the one at Crankley Point. (fn. 170)

The fort at Nun Mill Hill (NG 60135074) commanded the road from Bishopthorpe, and 'was strengthened with a double ditch, wherein there were about 120 souldiers'. (fn. 171) No traces of it remain: Southlands Methodist Church now occupies the site.

Lamel Hill (NG 61455095) is now a flat-topped mound 105 ft. in diameter and 15½ ft. high set on the tip of a ridge overlooking the city 650 yds. S.E. of Walmgate Bar. It is surmounted by a 19th-century summer-house, is encircled by a spiral asphalted path, and forms a garden feature in the grounds of the Friends' Retreat. Excavations by J. Thurnam in 1849 showed that the upper 10 ft. to 12 ft. of the mound contained 16th and 17th-century coins, the latest of Charles I, many disturbed human bones, and a 15th-century seal. (fn. 172) Below a turf line were 20 to 30 inhumations, orientated E.–W., and unaccompanied except for iron coffin nails and a large storage jar. This last was 17th-century and had no doubt been inserted into an otherwise undisturbed Christian cemetery of the 8th or 9th century. The cemetery had been covered by the windmill hill used for the battery, and again, after the siege, as the emplacement of a mill.

The site of the 'Leaguer' or fortified camp where part of the royal army was encamped in 1640, which was probably also used by Manchester's forces in 1644, can be located with some probability. Entries in St. Olave's parish registers during October and November 1640 mention 'the leager in the fields in Layre Close' or 'in Clifton'. (fn. 173) This camp, 'where several ramparts and bulwarks were thrown up' and many cannon mounted, was in Clifton Fields. (fn. 174) In 1836 'Legar' was the name of a field beside the Shipton Road, around NG 59055315, later to be occupied by Ouse Lea and two plots to the W. of that house. (fn. 175)

It was many years before the scars of the Civil War were healed. Even in 1725 a visitor could distinguish many of the earthworks erected eighty years before. Defoe wrote:

York is indeed a pleasant and beautiful city and not all the less beautiful for the works and lines about it being demolished, and the city, as it may be said, being laid open, for the beauty of peace is seen in the rubbish; the lines and bastions and demolished fortifications have a reserved secret pleasantness in them from the contemplation of the publick Tranquillity that outshines all the beauty of the advanced bastions, batteries, cavaliers and all the hard named works of the engineers about a city. . . . The old walls are standing and the gates and posterns, but the old additional works which were cast up in the late rebellion are slighted; so that York is not now defensible as it was then. But things be so too, that a little time, and many hands, would put those works in their former condition and make the city able to stand out a small siege.' (fn. 176)

From the Restoration to 1800

The city charter of 1665, like that of 1632, provided for the repair of the walls, which were kept in fairly good condition during the later 17th and the 18th centuries. The capture of York was one of the objects of the Farnley Wood plotters of 1663. The Duke of Buckingham, Lord Lieutenant of the West Riding, who was engaged in suppressing the conspiracy, moved the city's store of gunpowder to Clifford's Tower for safety, and the council had difficulty in recovering the thirty barrels. (fn. 177) Subsequently the Lord General, the Duke of Albemarle, wrote in 1665 recalling the plot and ordering the repair of the city walls, as he understood that they were very defective. (fn. 178) The Lord Mayor was able to reply that inspection had shown them to be very little in decay, but that he would have them speedily and effectively repaired, and would direct the removal of a house built upon them. (fn. 179)

Henry Keep's unpublished 'Monumenta Eboracensia' of c. 1680 (fn. 180) mentions the repair in 1666 of walls between Monk Bar and Layerthorpe Postern, the rebuilding in 1668 of many yards of wall between Walmgate Bar and Fishergate Bar (fn. 181), and the repair of a length between Walmgate Bar and the Red Tower in 1673. (fn. 182) He concludes that 'in 1669 not onely the ruinous parts by Bootham but throughout the whole city were all supplyed and amended so that at present she seems to be encompassed and girt about with a strong, lofty, magnificent and new wall which adds much to the grace and beauty as well as to the strength and security of this city'. The impressive appearance of the defences at this time is seen in the general views by Place and Lodge (Pl. opp p. 184. RCHM, York City III, Pls. 2, 3). Thomas Baskerville also noted that the wall and castle were 'constantly kept in good reparation'. (fn. 183)