An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in City of York, Volume 2, the Defences. Originally published by Her Majesty's Stationery Office, London, 1972.

This free content was digitised by double rekeying. All rights reserved.

'The Central Area', in An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in City of York, Volume 2, the Defences(London, 1972), British History Online https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/rchme/york/vol2/pp108-138 [accessed 26 April 2025].

'The Central Area', in An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in City of York, Volume 2, the Defences(London, 1972), British History Online, accessed April 26, 2025, https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/rchme/york/vol2/pp108-138.

"The Central Area". An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in City of York, Volume 2, the Defences. (London, 1972), British History Online. Web. 26 April 2025. https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/rchme/york/vol2/pp108-138.

THE CENTRAL AREA

The sector of the defences in this area extends from the Ouse at Lendal Bridge to the Foss at Layerthorpe Bridge and includes Bootham and Monk Bars, the site of Layerthorpe Postern, fourteen existing towers and the sites of four others (Lendal Tower to Tower 34). For most of their length the rampart and wall follow the N.W. and N.E. sides of the Roman fortress: Bootham Bar stands on the site of the Roman N.W. gate, and at the Multangular Tower the remains of the Roman W. angle tower are crowned by mediaeval masonry. A unique tower, perhaps of the 7th century, formerly buried in the rampart near the Multangular Tower is now exposed.

Lendal Tower, Ground floor plan

Lendal Tower (Pl. 27; Pl. opp. p. 107; Fig. above) stands on the bank of the Ouse opposite North Street Postern Tower which it originally resembled, being circular, but with a staircase turret on the N.W. The chain by which the river could be blocked extended between these towers. Lendal Tower is first mentioned in the Custody of 1315 as 'Turrim Sancti Leonardi' and in c. 1460 was described as the stone tower in St. Leonard's Landing. (fn. 1) A date soon after 1300 is probable on architectural grounds. Leland noted it as 'a great towre with a chain of yren to caste over the Ouse'. Bulwarks were made here and at the landing opposite by order of the Lord Lieutenant in 1569 as a protection against attack by the rebel Earls of Northumberland and Westmorland. (fn. 2) The tower was repaired in 1584–5: the cost was £6 10s. but this included work on the adjoining walls, requiring 2,300 bricks, and on a 'house of ease' at the landing. (fn. 3) In 1598 Henry Lynne agreed to roof the tower with tiles, draining well away from the walls, 'make a chambre floor plastred over' inside, to refrain from having a lime or plaster kiln there, and to maintain it, in consideration of a lease for 21 years at 4s. per annum. (fn. 4)

From 1616 to 1632 a Mr. Maltby was attempting to operate a piped water supply for the city based on the tower. (fn. 5) Previous suggestions in 1552, 1579, and 1593 for such a water supply had come to nothing. (fn. 6) In 1631, when the city agreed to take a fourth share in the enterprise, the tower was called 'the waterhouse'. (fn. 7) In the following year the city's share was leased to Thomas Hewley for £5 per annum and he was instructed to remove the wooden water pipes from Ouse Bridge. (fn. 8) Hewley was still tenant in 1646 when the tower was described as much ruinated. (fn. 9) At about this time it was used as a warehouse. Engravings by Lodge ('From the old Water house in York' and 'Yorke from St. Maries') show it as of three storeys but dilapidated. The making of a wall beside the tower to block passage along the river bank was ordered in 1654. (fn. 10)

In 1674 Henry Whistler of London proposed a new scheme for supplying water, and on 1 April 1677 the tower, noted as 'heretofore used as and for a Waterhouse or Waterworke', was leased to him for 500 years at a peppercorn rent. (fn. 11) He was permitted 'to lay Pipes, Wheeles and other Engines and things necessary' into the river and to dig up the pavements and road surfaces for pipes, provided they were made good within twenty-four hours. The tower was enlarged and heightened to take a lead cistern to which water was at first pumped by a waterwheel in the Ouse. This worked so erratically that in 1684 it was replaced by 'a wheel wrought with Horses, within the Tower'. (fn. 12) By 1685 the supply was apparently working quite well. At some stage before 1700 water was perhaps also raised by a wind pump on the roof of the tower or on that of a large, square and apparently wooden tower shown on drawings to have existed immediately to the N.E.

In 1719 Whistler died and the concern was sold for £4,000 to Col. William Thornton of Cattal. In 1756 it was mortgaged for £1,400 to Samuel Crompton of Derby, possibly to raise money for the installation at about this time of a Newcomen steam engine, perhaps designed by Henry Hindley, the clockmaker, of Blake Street. This engine had a cylinder 25 ins. in diameter and raised the water 72 ft., requiring 4.7 horsepower which was generated in a boiler 7 ft. in diameter. Baths supplied with hot and cold water were added adjoining the tower, in the present Lendal Hill House. In 1769 Mary Thornton was leased more land on condition that water was supplied to the Mansion House, Ouse Bridge Gaol, and St. Anthony's Hall. (fn. 13) The waterworks were sold in 1779 for £7,000 to Jerome Dring, who formed a new company: most of the twenty-eight shares were held by him and John Smeaton.

In 1781–4 Smeaton rebuilt the engine to work more efficiently. It then produced 18 horsepower, raising 16 gallons a stroke or 10,500 an hour, and was used up to 8 hours a day. The cylinder was 27 ins. in diameter and 8¼ ft. long and the beam was 24 ft. long, operating two pumps of 7½ ins. and 9 ins. bore. Details of Smeaton's test runs in August 1785, directions for running the engine, and several working drawings remain (Pl. 27), but of the machine itself only one pivot plate for the beam axle survives. The old boiler had been replaced by a copper one of haystack type 9¼ ft. in diameter: a detailed account of its installation in 1784 is preserved. (fn. 14) The improved engine worked in the tower until 1836, when it was moved to an engine house nearby. In 1846 the New York Waterworks Company was incorporated and bought the old shares for £20,000. The waterworks were moved to Acomb Landing and the tower was lowered by 10 ft. and given a mediaeval appearance to designs by G. T. Andrews. It was restored as offices for the company in 1932.

Architectural Description. The tower was originally 28 ft. in diameter with walls 4 ft. thick and with a spiral staircase in a rounded turret on the N.W. It has been considerably altered. A rectangular 17th-century addition to the E. and the destruction of the rounded E. and N. walls have changed the plan to a rectangular block, with rounded projections on the S. and W. The ground level has been raised, concealing the lower part of the walls, but on the side to the river, where a walk supported on cast-iron arches was added in 1864, a chamfered plinth is visible. The building of Lendal Bridge in 1862 has also affected the setting. Apart from the arrow slits visible in the ground floor of the original round tower and the staircase turret, none of the present windows is earlier than 1784. In 1844 there were three doorways, but all have been blocked and another has been pierced through the E. wall. There is much reused stone in the irregular facing, including a mediaeval canopy, finial and mouldings, probably from St. Mary's Abbey ruins. The present crenellated parapet was built in 1846, when the water tank was removed. The roof is covered with copper.

Inside, only two of the arched recesses for the embrasures of the mediaeval tower remain. The brick wall dividing the lower two storeys retains evidence of having accommodated the 18th-century engines, and it is possible that the two beams supporting the first floor over the W. room are reused from the beam of the first engine. A corbel course to support a floor exists inside the stair turret 8 ft. 2 ins. above the present ground level. The upper two floors were panelled and decorated in Jacobean style in 1932, as an inscription in the board room on the third floor records. The lift in the E. part of the tower was added at the same time, although the wooden spiral staircase remains in the turret. Drawings by Smeaton for the engine, its axle plate, and several wooden water pipes are preserved in the tower.

From Lendal Tower to St. Leonard's Hospital the city wall appears to have been difficult to maintain, both because it was built on a slope and because the road to the landing and ferry made this a desirable site for buildings which encroached on the defences. The wall has been rebuilt or destroyed between the tower and the point where it is pierced by a 19th-century arch. There is an abrupt ascent on to the rampart, and the facing of the wall, both outside and in, is fairly rough. The inner face is here up to 13 ft. high, in contrast to the external height of 6 ft., indicating reduction in height of the rampart. On the inner face can be seen large gritstone blocks, 3 ft. 2 ins. by 1 ft. 8 ins., and other reused stones with lewis and cramp holes, all probably Roman. There are four internal buttresses. The wall was rebuilt 5 ft. lower in 1874; the wall walk is only 3 ft. wide with a crenellated parapet 5 ft. high. The Lodge to the Museum Gardens was built in that year to a design by G. Fowler Jones. It is uncertain when the wall for the 110 ft. from the site of the Lodge to the buildings of St. Leonard's Hospital was removed.

The rampart in this stretch now extends from a point about 135 ft. from the river bank to a point about 110 ft. from the Roman fortress wall, a distance of only 100 ft. The ground rises to a level platform in front of the fortress wall. The level of the city wall incorporated in Lendal Hill House is such that the rampart can never have extended further towards the present river bank. Beyond the Lodge to the Museum Gardens there may have been a gap in the rampart on the line of the Roman road now represented by Lendal and Coney Street. The rampart is 72 ft. wide, 17 ft. high outside, and 12½ ft. high inside. The site of the outer ditch was marked by a strip 40 ft. wide between the base of the rampart and the city boundary as it existed up to 1884. Orders for scouring the ditch and repairing the wall in this stretch were made in 1601. (fn. 15)

From St. Leonard's Hospital to the Multangular Tower the city wall is the Roman fortress wall, standing up to 16 ft. high but patched in places with rubble and brick and reduced at the S.E. end for the Hospital buildings. Three blocked window recesses are visible inside, but in the outer facing there is now no sign of the large cannon ball scar and radiating cracks illustrated in 1683. (fn. 16) Internal buildings adjoining the wall, already existing in the 16th century, were not removed until after 1830.

It is possible that this length of wall was covered by the Danish and Norman rampart and exposed in July 1316 when the citizens demolished an earth rampart in this area. The Chronicle of St. Mary's Abbey, which records this, ascribes the death of five workmen to divine vengeance: 'die Processi et Martiniani venerunt Maior et Cives Eboracenses ad Abbatiam eiusdem et murum terre factum conquassarunt ita ut ulcione divina operantes scilicet v occisi sunt. Eodem anno in crastino Translacionis sancti Martini videlicet predicti maior et cives fossam inter sanctum Leonardum et Abbatiam fecerunt.' (fn. 17) This length of walls is the only one on the party boundary of the city and St. Mary's Abbey where the rampart is totally absent.

The Chronicle also mentions a ditch in this area cut by the abbot with the consent of the mayor only a few years before it was filled in again by the citizens in 1315, perhaps because the rampart was slipping. The ditch dug in 1316 presumably replaced this earlier one in a position less favourable to the abbey. 'Anno eodem videlicet die sancti Magni Martiris [August 19] venerunt cives Eboracenses cum manu forti et impleverunt fossam iuxta muros infirmarii ab Abbate Alano [elected 1313] Monasterii beate Marie eiusdem Civitatis erga inimicos Anglie scilicet Scotos consilio Maioris Nicholai dicti Fleming' et omnium fere civium operatam contra legem divinam et regiam iusticiam instigante Segewans' et aliis.' (fn. 18)

Three excavations in this area are relevant. In 1914 G. Benson revealed a mediaeval cobbled road entering the existing water gate of St. Leonard's Hospital, indicating that when the gateway was built in the early 13th century no rampart can have covered its site. (fn. 19) This water gate is probably the sally-port in Mint Yard mentioned in 1647; it may also be the Lendall Postern referred to in c. 1660 and otherwise unidentified. (fn. 20) In 1957–64 Mr. G. F. Willmot excavated the Roman interval tower (SW6) to the N.W. of this point and found that the Roman ditch was overlaid by the rough stone footings of a timber building. At the tower he found the plinth and facing stones of a mediaeval wall on the line of the city wall from Lendal Tower and overlying the end of a post-Roman ditch. When this wall was begun, whether or not it was actually completed, no rampart existed. (fn. 21) In 1926 S. N. Miller dug a section adjoining the Multangular Tower to the S.E. which revealed two ditches, previously interpreted (fn. 22) as of the 1st and 4th centuries. The outer ditch may, however, be post-Roman, since further to the W. Miller found two ditches following the curve of the Multangular Tower. (fn. 23)

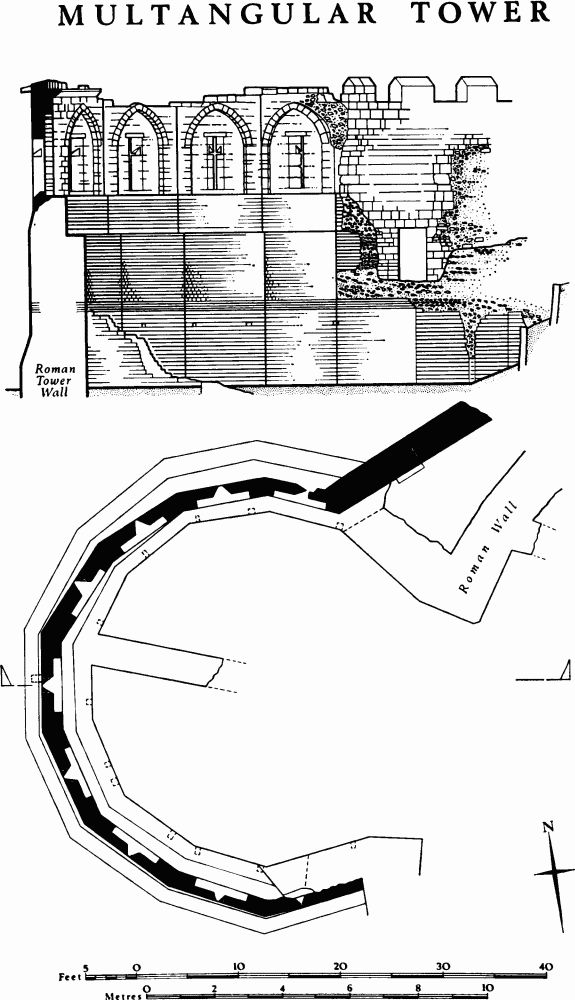

The Multangular Tower (NG 60005208. Pl. 29; Fig. p. 112), so called since 1683, but called Elrondyng in 1315 (p. 12) and 1505, (fn. 24) consists of the W. angle tower of the Roman fortress, (fn. 25) upon which are built late 13th-century walls. The latter are only 1½ ft. to 2 ft. thick, built of good ashlar in which the large blocks contrast markedly with the small Roman ashlar below. Between the two builds is a band of rough masonry where the Roman facing is missing. In each of the nine faces of the mediaeval work is a cruciform arrow slit; previous to restoration in 1960 the centres of these slits had been hacked out seemingly for gun loops. Internally the slits are set in recesses with pointed arches. A stone water-spout projects on the W.N.W. face 29 ft. from the ground, indicating the level of the wall walk; the parapet has gone. The interior was filled with earth to the base of the mediaeval walls until cleared by the Yorkshire Philosophical Society in 1831. (fn. 26) A stone plaque set at the base on the S.W., giving a brief history, was unveiled in 1968.

From the Multangular Tower to Bootham Bar the mediaeval city wall was built 2 ft. to 5 ft. in front of the Roman fortress wall buried in the rampart below. There is a 19th-century doorway through the wall adjoining the tower. The wall survives for only 200 ft. before the gap of 350 ft. whence the wall was cleared away for St. Leonard's Place in 1832–5. It is only 2¾ ft. thick and 11¾ ft. to 15¾ ft. high, with a wall walk only 1 ft. to 1½ ft. wide. There are seven evenly spaced original buttresses on the exterior and one, and scars of five others, on the inside. A double stepped coping on a merlon near the tower may be old. The slightness of the wall in this stretch is perhaps related to the presence of the adjacent fortified precinct of St. Mary's Abbey, here providing an outer defence.

The rampart has been removed internally between the Multangular Tower and Tower 19 to reveal the Roman fortress wall and lowered externally, exposing mediaeval footings. The present stone retaining wall 10 ft. high behind the Central Library may incorporate a retaining wall already existing in 1612 when the city council were concerned about its demolition: 'ther is a stone wall of freestone which holdeth upp a great parte of the ramper or moat lyeinge nere Bowthome barr within the walls of this cittie ... if the same should be suffred to fall or to be takne downe then the same ramper or moat will fall and likewise the cittie wall'. (fn. 27) A wall 1½ ft. thick immediately N.W. of the present retaining wall is probably of late mediaeval date (Fig. p. 113). The site of the outer ditch is marked by a lane running beside the King's Manor from Exhibition Square to the Museum Gardens. The ditch has gradually been filled up or encroached upon since 1580 when the Earl of Huntingdon, Lord President of the Council in the North, was given permission to set pillars or buttresses upon it. (fn. 28)

Multangular Tower

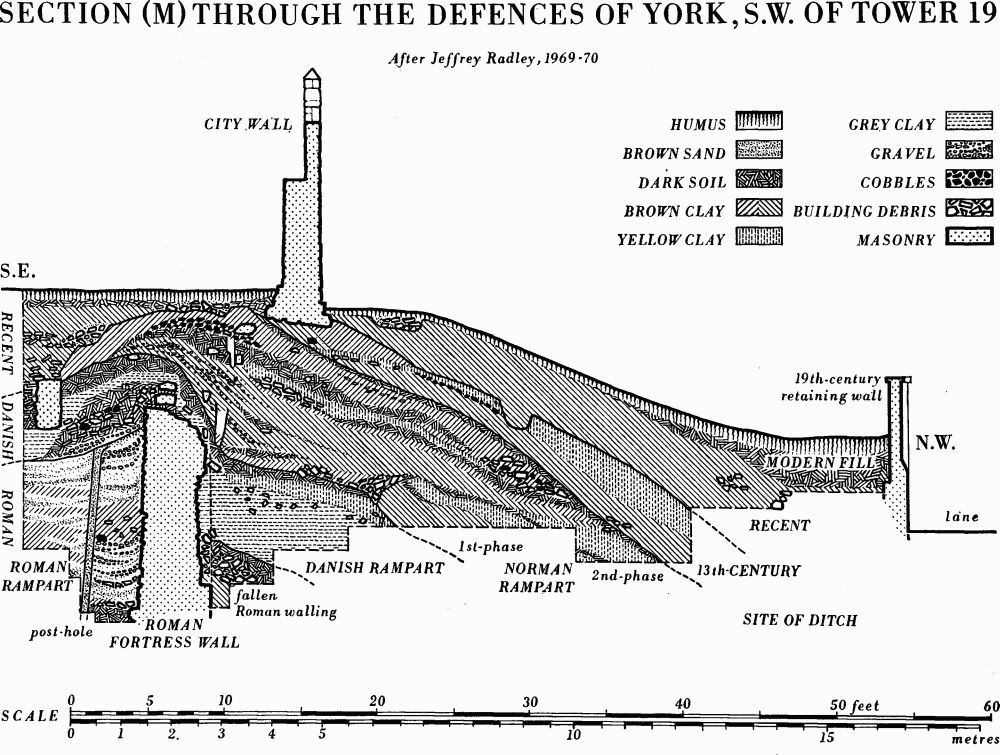

Tower 19 (NG 60045214. Pl. 30; Fig. p. 113) lies within the line of the mediaeval wall and was formerly concealed by the rampart behind the N. angle of the Central Library. It was built between c. 400 and 870, perhaps in the 7th century A.D., and may have been used for only a comparatively short period before being buried beneath a rampart in c. 900. It was opened up again in the 13th century, probably when the present city wall was built. Bones and jugs were then thrown in and lime was washed into the interior. After being filled up again it was rediscovered in 1839: 'On Thursday when some workmen were engaged in making a tunnel from the gardens behind the residence of C. H. Elsley, Esq., in St. Leonard's Place, in this city, to his stables in Mint Yard they came to a cavern which has excited much attention and consequent speculation.' (fn. 29) Much of the interior was then dug out and the vault was largely rebuilt in brick. When the exterior was seen again in 1934 it was identified as a Roman interval tower. (fn. 30) It has also been described as part of the porticus of a 7th or 8th-century church. (fn. 31) In 1969 it was excavated by Mr. J. Radley for the Commission and York Corporation and is now exposed. It was consolidated by the City Engineer's Department and opened to the public in 1971. An attached plaque describes it as the 'Anglian Tower'; another commemorates Jeffrey Radley.

Tower 19, Excavation 1969

Tower 19 is entirely built of roughly dressed oolitic limestone, mortared, but laid in a dry-stone technique, perhaps in haste. It is rectangular and still stands to a height of 14½ ft. The N.W. wall is built in a breach in the Roman fortress wall. A bench or step was cut into the inner face of this wall and the Roman internal bank was levelled to form a clay raft extending on to this step, on which the tower was then built. In the S.W. and N.E. walls are narrow segmental-arched doorways; in the N.E. of these, two steps lead down to the floor inside the tower. The roof was a segmental barrel vault with the long axis at right angles to the Roman wall. Externally the vault was levelled, forming a platform, but much of the vault has been replaced in brick. The 19th-century tunnel, 3 ft. wide and 6 ft. to 7 ft. high, also vaulted in brick, was cut through the N.W. and S.E. walls towards the eastern end; the entrances to it are visible in the rampart outside the city wall and as a blocked arch in a former stable, now a garage.

The excavation of the tower has shown that the Roman wall, which still stands 15 ft. high on either side of the breach, survived as a line of defence until c. 900, when it was covered by a bank 2½ ft. higher and 35 ft. wide at the base. The bank had a timber breastwork on the crest, backed by two courses of reused gritstone blocks, and partly supported on horizontal timbers set in grooves cut, where necessary, in the top of the Roman wall. In c. 1080 the bank was enlarged to a width of 45 ft. at the base and heightened by 3 ft. with sand and gravel, presumably from the ditch. Post-holes and nails indicate that this enlarged rampart also had a timber breastwork. The bank was again enlarged in the 13th century to a width of 70 ft. and a height 3 ft. above the crest of the Norman rampart; it has since been cut back and its height obscured by changes in the adjacent ground level. In 1970 an excavation through the rampart outside the city wall (Fig. p. 114) in continuation of the line of the section within the wall by Tower 19 was still unfinished when Mr. J. Radley was killed by a fall of earth as he was investigating the presumed Danish ditch. The section confirmed the conclusions reached in 1969 but suggested that the supposed Norman rampart was of at least two periods. Birch stakes and many animal bones were found in the dark filling of a ditch some 30 ft. outside the mediaeval wall, but the dimensions of the ditch and filling were not recorded. Later in 1970, during clearance S.W. of Tower 19 to display the Roman wall and to underpin the city wall, a more complicated stratification was revealed in the sections. Consideration of the evidence may necessitate modification of the suggested chronology of the successive ramparts. The excavations, carried out at this time for the Department of the Environment, were directed by Mr. B. K. Davison.

Section (M) Through The Defences of York, S.W. of Tower 19 After Jeffrey Radley, 1969–70

Tower 20 (site at NG 60055215) was rectangular. It appears on maps from 1694 to 1829 and was subsequently demolished.

Excavations relevant to the rampart have been made at three other places on this stretch. In 1928 S. N. Miller dug several trenches in the grounds of No. 9 St. Leonard's Place. (fn. 32) At the site of the Roman interval tower NW2, in trench XXIX (NG 60075215), he observed that the Roman wall stood 16 ft. 5 ins. high and was covered by the rampart and 3½ ft. of sandy makeup, presumably from the house cellars. The mound above the wall contained a coin of Constantius and Crambeck pottery with an unusually high proportion of late sherds.

Miller's trench XXVI to the footings of the fortress wall on the exterior at a place (NG 60075218) where most of the rampart had been removed in modern times showed that the base of the rampart overlay debris from the wall, including facing stones and a merlon. A hole into the core of the wall appears to have been a deliberate attempt by attackers to weaken it. Trenches XXXVI and XXXVII revealed evidence to suggest that the mediaeval outer ditch was about 23 ft. wide and 8 ft. deep below the 13th-century ground level; the inner edge was about 50 ft. outside the Roman wall. A layer of brown clay 8 ft. thick over the Roman ground surface in the forecourt of the King's Manor is unlikely to have been a defensive bank of the Saxon Earlsborough, as Raine thought. (fn. 33)

Excavations for drains outside the De Grey Rooms on the opposite side of St. Leonard's Place during 1842 revealed a coin hoard of 10,000 Northumbrian stycas dating to c. 865 (fn. 34) buried at a depth of 5½ ft. below the surface of the street. The coins were in a pot close to the Roman wall. The street level is here 6½ ft. to 8 ft. above the general Roman ground level, so the hoard must have been buried to some depth into the Roman rampart rising above that level, no doubt before the Danish bank covered both the rampart and the wall. Other stycas had previously been found near this spot. (fn. 35)

In this stretch the Roman curtain wall was still standing to a height of at least 16½ ft. when covered by the later bank; indeed a wall of even greater height was possibly preserved where interval tower NW3 was seen, for openings noted during its demolition were presumably in the upper stage at or above the level of the parapet walk. (fn. 36) Where removed for St. Leonard's Place the rampart must have stood to a height of well over 20 ft. above the Roman level or 15 ft. above the mediaeval level.

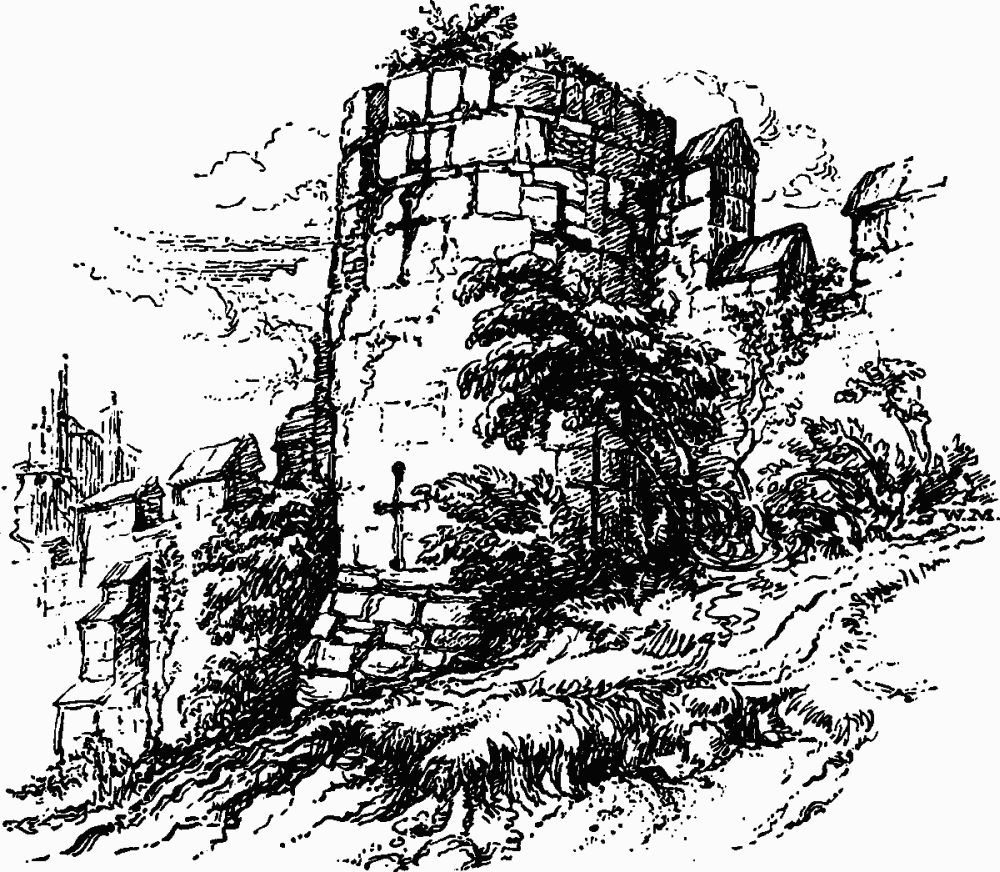

Tower 21 (site at NG 60105221. Pl. 28, Fig. below) was semicircular, 17½ ft. wide and projecting 9½ ft. It was open to the rear and rose above the wall walk. Externally it had a battered plinth and at least four cruciform arrow slits on two levels. It was demolished in 1831–5.

Tower 21 near Bootham Bar after G. Nicholson, 1827.

The length of wall adjoining Bootham Bar was removed in 1834–5 and replaced by the existing wall a few feet N.W. of the old line. The latter was altered soon afterwards by the piercing of a wide round-headed arch, since blocked, leading to a builder's and stone-mason's yard, and by the addition of an external stairway leading to the first floor of the Bar and to the wall walk. The archway was built to a design by G. T. Andrews after 1842, when the erection of the De Grey Rooms blocked the former entrance. (fn. 37) The city wall is here approached by the precinct wall of St. Mary's Abbey, described below (pp. 160–73).

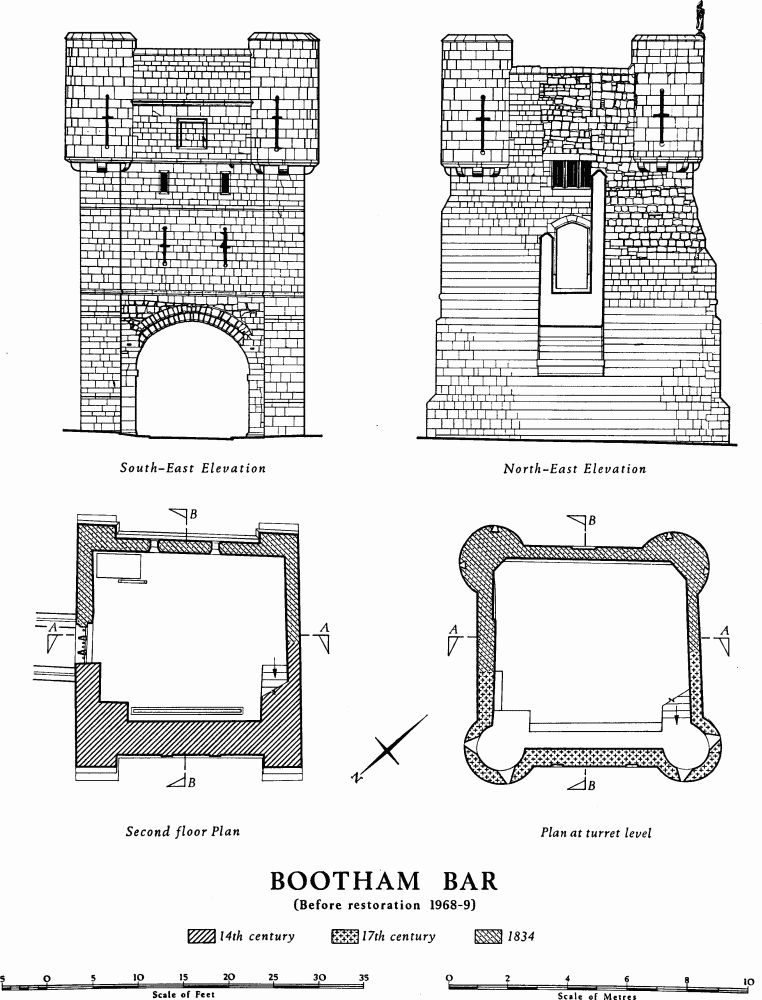

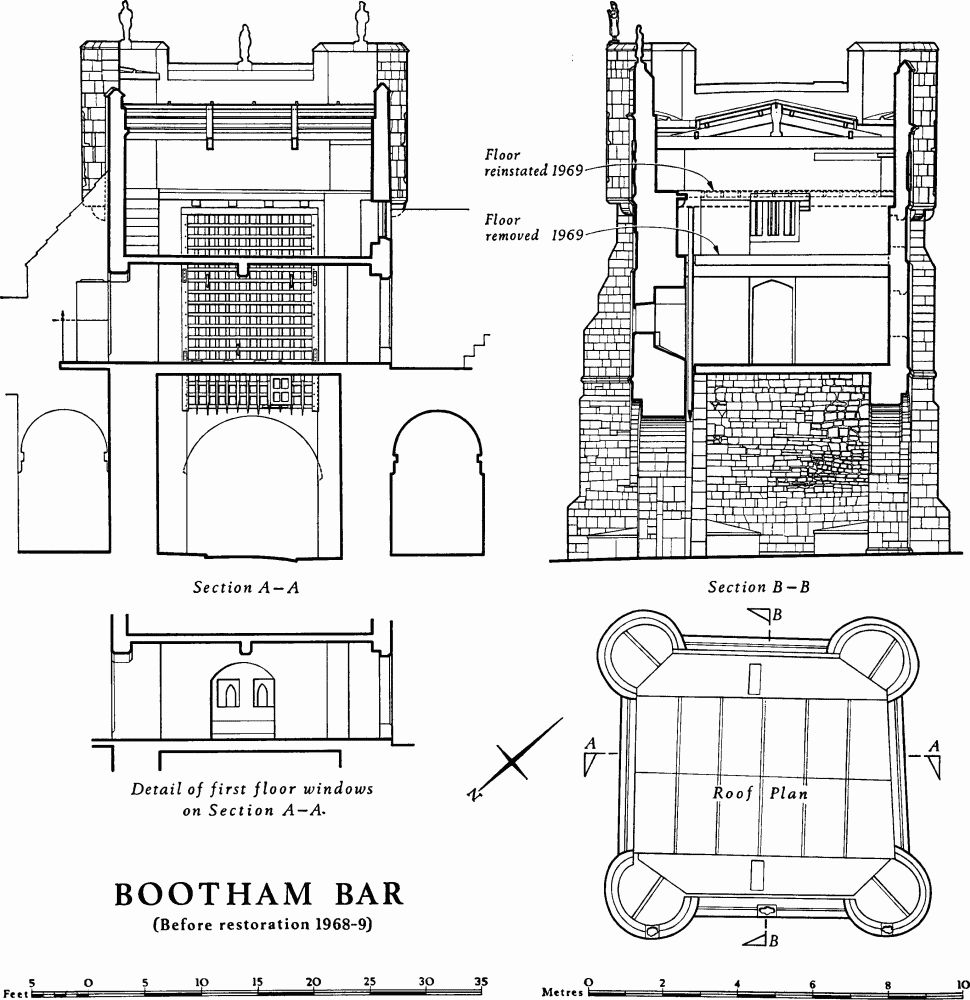

Bootham Bar (Pls. 28, 31–3; Pl. opp. p. 121; and Figs. pp. 117–20) consists of a passage with archways at each end and of a rectangular gatehouse of two storeys above with circular bartizans at the angles and a low-pitched leaded roof. Much of the outer archway is of gritstone, the rest is of magnesian limestone.

Bootham Bar replaces the porta principalis dextra of the legionary fortress, which lay immediately behind and beside the mediaeval gate. (fn. 38) The Roman gate was probably still in use in the late 7th century, when it was mentioned as a boundary in a land grant known from an early 11th-century summary. (fn. 39)

The earliest parts of the present structure, the jambs and inner order of the outer archway date from the 11th century. The name, which first occurs in c. 1200, (fn. 40) means 'the bar at the booths'. (fn. 41) St. Mary's Abbey had the right to hold a weekly market here, a custom which may go back before the abbey's foundation in 1089 to the period of Earl Siward's minster.

The gate was also known in c. 1210 as Galmanlith or Galmonelid, perhaps a scribal error for Galmouelid, the gate of Galmou, the pre-Conquest name for the hill on which St. Mary's Abbey was built. The identity of Galmanlith and Bootham Bar is proved by documents in St. Leonard's Hospital Cartulary. (fn. 42) One reference is to a plot 'infra portam Civitatis Ebor. que vocatur Galmanlith', (fn. 43) and another to 'Galmanlith scilicet infra Barram de Bouthom'. (fn. 44) By the late 13th century Galmou was also understood to indicate Bootham Bar. (fn. 45)

Tolls collected at the Bar are recorded in 1280. (fn. 46) In 1376 a rent of 4s. was received for a house over the Bar; (fn. 47) rent and expenditure on repairs to this house continue in the city's accounts during the 15th century and later. During the 14th century the Bar was heightened to house a portcullis and a barbican was added; the absence of any means of access to a barbican parapet walk from the first floor of the Bar, as provided in the other three main Bars, suggests that when the heightening took place a barbican was not envisaged. The portcullis is mentioned in 1454–5, (fn. 48) and in 1488/9 there were great gates and a wicket. (fn. 49) In 1511 two guns were delivered to Robert Preston, officer of the ward, for the Bar: 'a brasen gonne and a potte gonne of yren with v. chambres belongyng unto theym'. (fn. 50) Expenditure of £25 in 1581–3 (fn. 51) probably indicates the rebuilding at that time of the rear façade, as at Micklegate and Walmgate Bars. In 1603 over £10 was spent on repairs, including £4 to Edward Bykes, painter, for gilding the Bar on both sides and painting it russet and white. (fn. 52) The Bar was again painted and gilded in 1633. (fn. 53) On both occasions the redecoration was in preparation for a royal visit. There are also occasional references to the display over the gate of the heads of traitors, including that of Thomas Mowbray, the Earl Marshal, in 1405. (fn. 54)

The gateway was damaged in the siege of 1644 and repaired in 1645. The bartizans and the upper part of the façade towards Bootham were probably built then, preserving the general form of the earlier work. In 1647 'the kings armes and the citties armes' were carved in stone and set up on the Bar. (fn. 55) In 1719 the façade to High Petergate was rebuilt in stone, (fn. 56) and in 1738 a statue identified as King Ebrauk, the eponymous founder of York, was placed in a niche there. (fn. 57) The gates were replaced in 1748 by new ones made by George Gelson as qualifying work to become a freeman, but after 1780 they were allowed to decay until only one leaf was left, which was removed in 1789. (fn. 58) A passage through the city wall on the N.E. side of the Bar was made in 1771. (fn. 59) The heightening of an outer arch to 12 ft. was ordered in 1785, but it may not have been done. (fn. 60) When St. Leonard's Place was made in 1831–5 the barbican was removed and a length of wall and rampart S.W. of the Bar was demolished. The Bar itself was in danger of destruction, (fn. 61) but in 1834 the inner façade was rebuilt and the sides refaced at the Corporation's expense to a design by Peter Robinson, and foot passages were made on each side, (fn. 62) the one of 1771 on the N.E. being reconstructed to conform. Further repairs were carried out in 1844, and in 1889 the exterior stone stairway was added, replacing the former access to the first floor from within the walls. The three statues on the outer façade were renewed in 1894. (fn. 63) The whole Bar was restored in 1951, but more extensive restoration and conservation, made necessary by serious cracks, and costing some £25,000, was completed in 1970.

Architectural Description. In the N.W. front towards Bootham (Pl. 32) the large round-headed archway to the passage is of two plain orders of which the inner is supported on large gritstone blocks, probably reused Roman material; the arch springing is set back from the main plane of the jambs. This order, which is also of gritstone and has been badly scraped by vehicles, is the oldest part of the gate and can hardly be later than c. 1100. The outer order of limestone, which is probably a 12th-century addition and more neatly coursed, rests on a single corbel to the N.E. and a double corbel to the S.W. Several of the voussoirs of this outer order are modern replacements. The archway is flanked by muchaltered buttresses with chamfered setbacks, and above it is a string at the level of the first floor. On the N. buttress is a rectangular stone plaque carved in relief and painted with the words BOOTHAM BAR RENOVATED 1969 and with a shield of arms of the City of York below a cap of maintenance and upon a mace and sword in saltire. A half-round blocking in one of the stones above the string course is the remains of a spout discharging above the arch and represents the 12th-century parapet level.

Two small pointed windows light the first-floor room. Above these is a setback. The upper part of the façade projects at the level of the base of the bartizans on a chamfered corbel course. Below the latter are two shields carved and painted with the arms of the City of York and, above it, within a round-headed moulded frame is a larger shield surrounded by a garter and now surmounted by an open crown, added in 1864, when the shield was painted with the arms of England (Fig. below). It probably originally bore the royal arms of the Stuart kings, since these shields are probably those carved in 1647, and was so restored in Portland stone in 1970. On each side of this coat of arms and at a higher level is a blocked rectangular window or gunport. Another string course marks the roof level. The bartizans are supported on plain corbels and lit on the front and outer sides by two cruciform arrow slits with round oillets to the vertical slit. A weathered parapet on the bartizans and central block supports three statues in Portland stone dated 1894, the central one representing Nicholas Langton, mayor in the 14th century, and the others a mason and a knight. These are by George W. Milburn, whose workshop adjoined the Bar.

Bootham Bar. Arms on N.W. Elevation (before 1969)

Bootham Bar (Before restoration 1968–9)

Bootham Bar (Before restoration 1968–9)

Bootham Bar (Before restoration 1968–9)

Bootham Bar, from W. Watercolour by J. Mullholland, c. 1835.

The S.E. façade to High Petergate (Pl. 33), apart from the archway to the passage, was built in 1834. The arch is roughly semicircular and rises from roll-moulded imposts of c. 1150–75 which have been partly dressed off; it is faced towards the city with a skin of masonry added in the 14th century. The arch springing is again set back from the main plane of the jambs; these last have chamfered plinths, also 12th-century. The iron hooks for the gates survive on both sides of the archway. The buttresses, with two chamfered setbacks, were rebuilt to the old pattern in the 19th century, but previously reached only to the string course above the arch. Before 1719 the façade had three gables (Pl. 28) and was probably timber-framed. As rebuilt in 1719 it had a round-headed niche between two round-headed windows (Pl. 33); above was a rectangular plaque, and a continuous cornice broke forward above the spaces between the windows and the niche. The whole was crowned by a high parapet with a pedimental feature in the middle. The niche later held the stone statue of Ebrauk brought from the Guildhall, a replacement for that which, previous to 1501, had stood at the junction of Colliergate and St. Saviourgate and was known as 'Old York'. The statue set in the Bar represented a king in armour, crowned and bearing an orb and sceptre. (fn. 64) The present façade has two cruciform arrow slits at first-floor level, two narrow rectangular windows lighting the second floor, and a plain square recessed panel above in a high parapet in two stages divided by a moulded string. The bartizans resemble those on the Bootham front, but are solid below roof level and the two arrow slits penetrate only to a slight depth.

The side elevations of the Bar are mainly 19th-century, including the doorways at first-floor level and a three-light rectangular window in the N.E. side lighting the second floor.

Inside, at ground level the passage walls are regularly coursed in the lower part, which is probably 12th-century work. In the S.W. wall 6 ft. 10 ins. from the ground are three worn corbels 3 ft. apart, but there are no corresponding ones in the opposite wall where there is an offset for a timber roof. There is a portcullis slot, now blocked, behind the N.W. arch.

The first-floor room is now entered by doorways in the side walls but in 1832 was reached by a spiral staircase approached through a house adjoining on the S.E. The wall walk to the S.W. was reached through a doorway in much the same position as the present one, but another doorway formerly existed to the W., where a low recess marks its site. The two windows opening into a segmental-arched recess in the N.W. wall could have been reached only when the portcullis was lowered. The portcullis is now cut into two and fixed in position; the grating, made of timbers 4 ins. by 3 ins. in section set 7 ins. apart, is now 19 ft. high and 12¼ ft. wide; it has the usual pointed ends to the upright members and a small wicket; the outer frame includes some old timbers. The floor of the room, of concrete and steel joists, is modern. The room itself is loftier since the 19th-century second floor was removed in 1969; the offset on which the floor rested is now exposed. A flight of stone steps against the S.W. wall leads to a low gallery linking the two ancient bartizans. The wall walk to the N.E. was apparently once reached from the second floor by a doorway in the N.E. wall.

The third floor was replaced in timber at the 1969–70 restoration and the space above can only be reached through a trap-door. The portcullis was operated from this level by an upright windlass and ropes, still in good condition in 1834 (fn. 65) but not now surviving. A new rope had been supplied in 1746 as part of the preparations against the Jacobite army. (fn. 66) The leaded roof, which is reached through a trap-door in the N. bartizan, formerly sloped to S.W. and N.E., not as now to N.W. and S.E.

The barbican, demolished in 1831 except for the S.W. side which remained until 1835, projected 47 ft. in front of the Bar, was 26 ft. wide and about 16 ft. high, with walls 3½ ft. thick. A wide pointed archway in the front was flanked by two crenellated bartizans, each with one tall cruciform arrow slit and resting on a cone-like corbelling. A string course formed a weather-mould over the arch and returned below the corbelling. Above the arch was a plain parapet supported on corbels and with a rectangular panel in the middle. A doorway in the S.W. wall was probably a sally-port. It is uncertain how the wall walk of the barbican was reached since there is no sign of openings through the buttresses flanking the front of the Bar, as in the other major gateways; moreover the form in 1832 of the stepped fronts of the buttresses was as it is today, making the existence of blocked passages unlikely. Thus the barbican may have been accessible only from ground level outside the main gate, as at Thornton Abbey, Lincolnshire. The wall walk was narrow and projected internally on a chamfered ledge. The watch house adjoined the Bar on the S.W., and the 'Bird in Hand' public house abutted against the S.W. side of the barbican.

From Bootham Bar to Monk Bar the wall was restored in 1888–9; it was the last section so to be treated. From G. T. Clark's advice on the restoration and from detailed contemporary drawings, it appears that in 1886 the wall retained generally a plain parapet, although with some embrasures remaining walledup near Bootham Bar, a fragment of wall walk and twenty-nine old buttresses. Clark's suggestions seem to have been followed, and the present crenellated parapet, the upper part of the external facing, the wall walk, and the series of internal arches supporting it were all built in 1888–9. The external face of the wall is exposed and readily accessible along Lord Mayor's Walk but concealed by buildings in Gillygate, where it forms the rear boundary of some twenty different back yards. The internal face is mostly visible in the Deanery, New Residence, and Gray's Court gardens.

The rampart at Bootham Bar was formerly about 16 ft. high with the Norman gateway projecting externally. The greater height here may be due to additional material from the recutting of the ditch. The length of ditch along Lord Mayor's Walk is the best preserved of any on the circuit. Internally the rampart has been damaged by use as a garden feature from the 17th century onwards.

Tower 22 (NG 60155227) is demi-hexagonal, 16 ft. wide and projecting 7 ft. There is a battered base and part of an arrow slit, mostly buried, on the W. The cruciform slit with rounded oillets in the N.W. wall is modern. The parapet rises above an external string course and has small merlons with miniature arrow slits below gablets on the N.W. Internally the platform is raised above the wall walk. This parapet and upper facing are of 1888–9.

Tower 23 (NG 60175228. Pl. 5; Fig. below) is demihexagonal. It has a chamfered plinth and a circular gunport, 1 ft. in diameter, set 4 ft. above the external ground level, with a modern cruciform dummy arrow slit above. The gunport dates from c. 1460 and is apparently an insertion in an earlier wall. The parapet is treated as in Tower 22 and the platform is raised above the wallwalk on either side. Internally the tower is hollow and open-backed with a brick-arched recess. A further small recess does not penetrate to the arrow slit or gunport.

Tower 23

In the wall between Towers 23 and 24 there are two setbacks indicating earlier rebuilding. Miller's most important section of the defences was cut at a point near Tower 24 in the Deanery Garden at NG 60225233 (Profile N). The Roman wall here survived to a height of 13 ft. above the foundation and the internal rampart stood to a height of 12 ft. and was separated from the post-Roman layers by odd piles of debris and a layer of vegetation. In the post-Roman rampart Miller observed 'two strata of beaten occupation-earth with a layer of clayey earth between' although he regarded it as all of one Norman date. A block of stonework shown on his section as resting on the top of the Roman wall and overhanging its outer face may be the footings of a later wall rather than wall debris gathered from a Roman level. An indication that the two upper strata of the rampart differ in date is given by the levels of three post-Roman stone walls behind the Roman wall. Of these, one revetted the cut-back upper part of the rampart at the level of the top of the upper stratum, and the other two, connected by a floor and so forming the walls of a large building, belonged to a level 4 ft. lower but still later than the lowest stratum.

The evidence from this section suggests that the Roman defences lay derelict for a long period and were covered by vegetation. Both wall and rampart were then concealed under a bank of earth scraped up from areas of occupation, probably by the Danes after 867. On top of the bank either a stone wall was built or stone debris was dumped to revet a timber breastwork as at Tower 19. The bank was later enlarged by adding further layers of occupation soil on its inner side, probably in the Norman period, and again heightened, perhaps under King John or when the stone wall was added in the 13th century. (fn. 67)

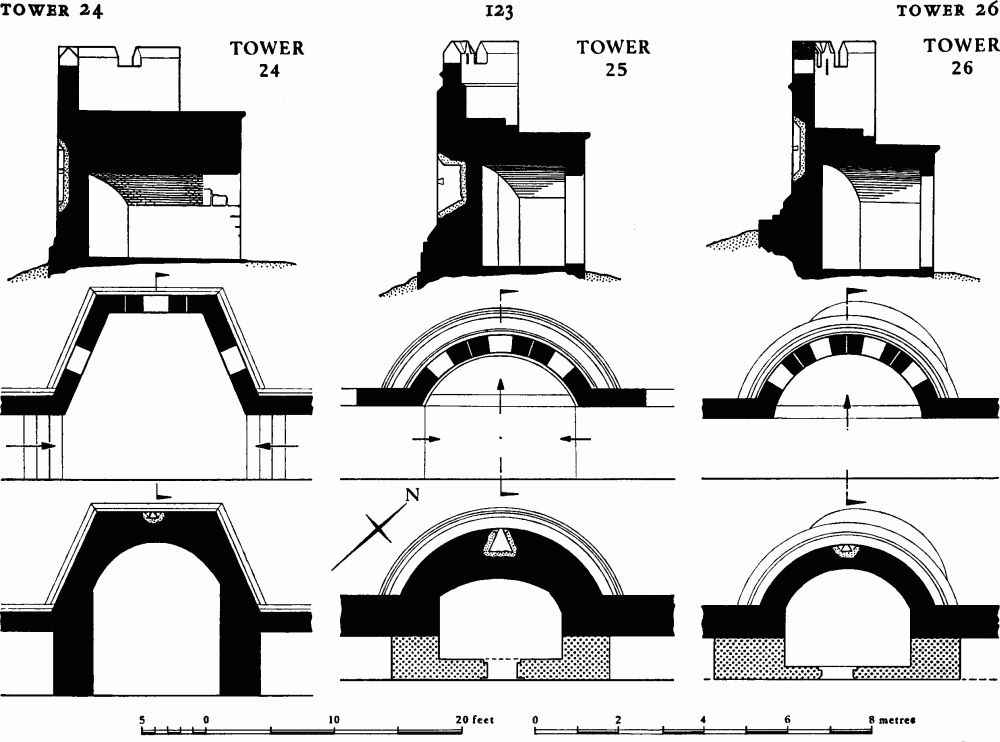

Tower 24 (NG 60225234. Fig. above), added against an earlier curtain wall, is demi-hexagonal. It has a prominent chamfered plinth and a modern cruciform dummy arrow slit in the N.W. wall. The base course includes two reused blocks with roll mouldings resembling those in the wall to the S.W. (see below). The parapet resembles that of the preceding towers and the platform is raised above the wall walk on either side. Inside there is a semicircular recess, open to the rear, arched in brick and stone.

A notable feature in the base of the wall adjoining Tower 24 is a group of reused stones. These include two with chevron and pellet decoration, apparently voussoirs, and others with chevron and roll mouldings. They date from c. 1150 and may be derived from the Arch bishop's Palace. A buttress near the same tower is of late 13th-century type, and others between Bootham Bar and Tower 27 are also probably original.

Tower 25 (NG 60255238. Fig. above) is semicircular. It has a slight battered plinth, with the arris marking the base of the batter cut in the middle of a course, and is faced with large blocks. The rounded lower oillets of arrow slits appear in the sides 6 ins. above the plinth, and the central cruciform slit is in completion of an old lower oillet. Lengths of the uprights of two more slits appear 5½ ft. above the plinth. The parapet, above an offset, resembles the parapets of the preceding towers, and the platform is also raised above the wall walk. The tower was open to the rear until 1888–9 when straight brick side walls and a stone rear wall with a central doorway were added.

There are two old musket loops in the parapet between Towers 25 and 26.

Tower 26 (NG 60285241) is semicircular, 14 ft. wide, and projecting 5 ft. It collapsed in 1957 and was rebuilt with the old materials, above the footings. It has a plinth, a central arrow slit with old lower oillet, and reset facing stones with three other oillets, probably from this same slit. The parapet has been rebuilt as restored in 1888–9, and the platform is raised above the wall walk. The interior, open at the rear in 1850, is now a room with a rounded N.W. end, 10 ft. wide, 7¾ ft. deep, and 8 ft. high, with a doorway in the rear wall.

Tower 27 (NG 60315244. Pl. 34) at the N. angle of the defences was called the Bawing Tower in 1370, (fn. 68) the Frost Tower in 1485, (fn. 69) and Robin Hood Tower in 1622 and 1629. (fn. 70) Inconsistencies between the various maps of the city make it difficult to determine the original form, but Archer in c. 1682 shows the plan much as it existed in 1886; the corner was then polygonal with three buttresses and a round opening, possibly a gunport, in the N.E. face. The present tower was built in 1888–9. It forms a three-quarter circle on plan. Outside it has a base, then a chamfered setback below a neatly faced wall with eight cruciform slits in two staggered rows. The parapet, above a string course, has a small cruciform slit in each merlon. The platform is raised above the wall walk by five steps. The inside, entered through a doorway in the rear wall, is divided into a small lobby and a larger rounded room, roofed in concrete.

The rampart S.E. of this tower was examined by Miller in a section cut from the outside at about NG 60345241 (KL; Profile O, Fig. opp. p. 41). Evidently the Roman ditches had been allowed to silt up with black alluvial filling; at one place this was heaped into a ridge 2 ft. to 3 ft. high, perhaps as part of a boundary bank. Three strata were seen in the rampart, the lowest of which did not cover the Roman wall; the uppermost probably corresponded to the heightening of the rampart in the 13th century.

Tower 28 (NG 60385239. Pl. 34; Fig. below) is semicircular. Seen from outside, the lower 12 ft. is mediaeval and built of large blocks above a battered plinth of the same type as that of Tower 25; there are three cruciform arrow slits and remains of another at a higher level. The upper part, restored in 1888–9, has a shield with an equal-armed cross in relief in the centre and a parapet supported on corbels with a cruciform slit in the central merlon. At the junction of the tower and curtain wall on either side are hollow 'pepper-pot' turrets of 1888–9 with corbelled bases and crenellated parapets. Each has a small cruciform slit in the front and a narrow opening to the rear. The platform is raised above the wall walk, here itself widened and raised by 2 ft. to 3 ft. The semicircular room inside, with splayed openings to the arrow slits, is entered through a doorway in the stone-faced rear wall of brick.

Tower 28

Tower 29 (site at NG 60455233) is variously shown on plans from 1610 to 1785 as rounded or square; it does not appear after 1822. A reused stone with part of an oillet and a piece of plinth moulding, probably 13th-century, in the outer face of the city wall on the approximate site may have come from this tower or from the presumed earlier Monk Bar. Speed's map is the only evidence for another tower between this point and Monk Bar. A tower on this stretch of wall was called 'Talkard Tower' in 1477. (fn. 71)

The curtain wall from the N. angle to Monk Bar appears to be of one build, with numerous added buttresses. The length of 250 ft. N.W. of the Bar is sinuous in plan as if the wall had been very unstable; where it crosses the two depressions on the rampart it has cracked and been rebuilt and patched (Pl. 35). The parapet is largely 19th-century. The arches supporting the wall walk give way to a solid wall at the boundary between Minster Court and Gray's Court, and the wall walk drops here by six steps. Internally the face is stepped back thrice and contains many reused blocks, including a 15th or 16th-century window mullion and some gritstone slabs 3½ ft. to 3¾ ft. by 1¼ ft., perhaps Roman. A bronze plaque on the inner face of the parapet reads: 'This tablet was placed here by the Council of the City of York, October, 1898, to record that this portion of the Walls (37 linr yds.) was in the year 1889 restored to the City by Edwin Gray, who served the office of Lord Mayor in 1898.' The inner face of the wall immedately adjoining Monk Bar is obscured by buildings in Monk Yard, formerly Elbow Lane.

The rampart in this stretch is generally about 90 ft. wide, 18 ft. high outside, and 13 ft. high inside. The ditch before the walls survives along the S.W. side of Lord Mayor's Walk as a hollow 40 ft. wide and 4 ft. deep. There are two subsidences in the rampart in such positions as may have flanked the site of the porta decumana of the Roman fortress. The first (NG 60465233. Pl. 35) probably results from the removal of Tower 29. The other depression (NG60485231) is perhaps due to the demolition of a 12th-century gate on the site of, and possibly incorporating the remains of, the Roman gateway. The rampart was sectioned by Miller at this latter point, showing that the inner part had been completely removed, perhaps by Gray in 1860, and that the city wall had been subsequently underpinned. The footings of the mediaeval wall were separated from the much-damaged Roman wall by 2 ft to 3 ft. of earth. (fn. 72)

One of the many King's Ditches in York ran along the base of the rampart on the inside. It was the subject of a dispute in 1419. (fn. 73) This and later references (fn. 74) show that it was an open sewer. A length near the N. angle was enlarged to make fishponds in Sir Arthur Ingram's gardens and later lay in 'Kettlewell's Orchard' but no trace is now visible.

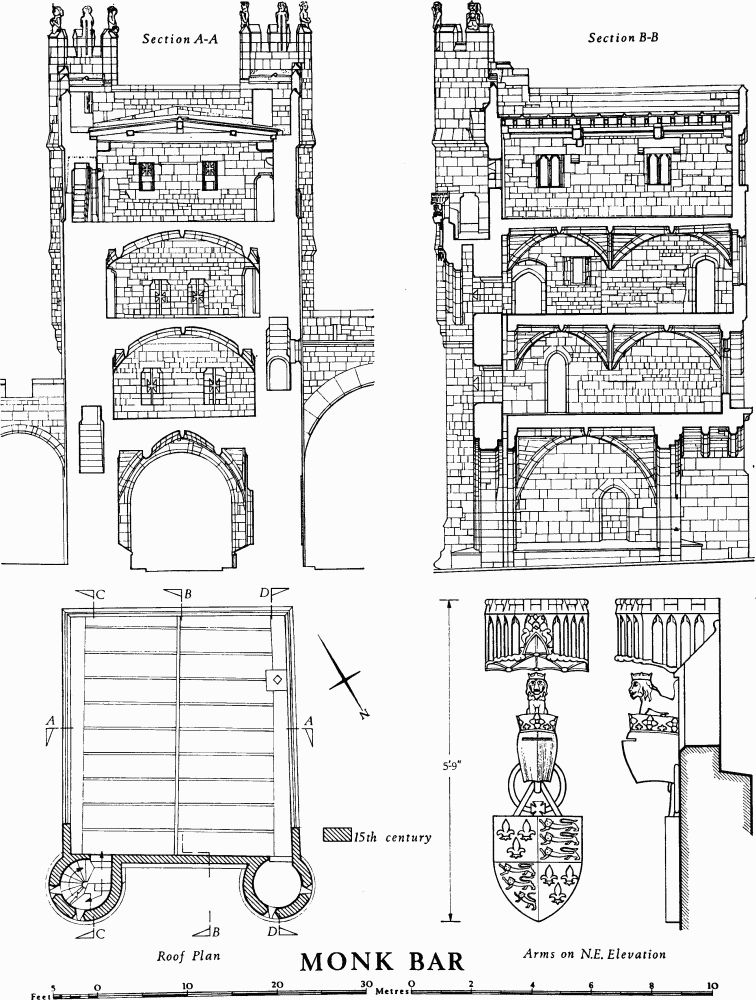

Monk Bar (Pls. 36–40; Figs. pp. 126–32) consists of a four-storey gatehouse with circular bartizans at the N. and E. angles and a low-pitched leaded roof. The passageway and two lower storeys above have ribbed vaults. A lofty arch on the outer face between the bartizans supports a narrow crenellated gallery at third-floor level. The Bar, which lies 100 yds. S.E. of the porta decumana of the legionary fortress, is built almost entirely of magnesian limestone and dates from the early 14th century; the uppermost storey was added in the late 15th century and windows were renewed in the 16th century. The gatehouse was built to a sophisticated design, making it a self-contained fortress with each floor defensible, even when the others had been captured. Variations in stone sizes and irregular coursing indicate several stages during the construction, with the front wall apparently preceding the vaulting. There is no trace of an earlier gate on this site.

The earlier mediaeval gate probably lay on the site of the Roman porta decumana, where signs of extensive rebuilding and of a former tower may be seen. This position for the gate is indicated both by the alignment of the S. part of Goodramgate and by the name of the destroyed church of St. John del Pyke (of the gate). Tolls collected in 1280 at Monk Gate (fn. 75) must refer to this earlier gate. The name derives from the street of Monkgate, mentioned as early as c. 1075. (fn. 76) The monks were the community of the pre-Conquest minster, a designation which would have been obsolete in the 12th century. The original Monkgate was a street on the Roman line running from Monk Bridge to the porta decumana and so called because it led directly to the Minster precincts. It is suggested that when the stone defences were built the old gate was replaced by one on the present site and the street name was also transferred. The question has recently been discussed by Mr. H. G. Ramm. (fn. 77)

Monk Bar

Monk Bar

Monk Bar

Monk Bar

The present form of the name first occurs in 1370. (fn. 78) In 1435/6 the house above the Bar was rented for 4s. a year to Thomas Pak, the master mason of the Minster, (fn. 79) in 1440/1 to William Croft, gentleman, (fn. 80) in c. 1450 to John, Lord Scrope, (fn. 81) and in 1476, when described as the stone tower situated above the Monk Bar, to Miles Metcalf, Recorder from 1477 to 1486, for 5s. (fn. 82) Hand-guns were delivered to William Wode, officer of the ward, presumably for this bar, in 1511. (fn. 83) In 1541 the Bar was cleaned in preparation for Henry VIII's visit. (fn. 84) In 1563 it was used as a temporary prison, (fn. 85) and in 1577 this use became permanent. (fn. 86) In 1583 the rooms there were inspected to see if they were suitable for imprisoning recusants. (fn. 87) They were presumably found so, because in 1594 'Alice Bowman was sent to a place called Little Ease, which is in Monk Bar'. (fn. 88) A recalcitrant apprentice was also confined in Little Ease in 1598. (fn. 89) This prison was probably one of the tiny rooms in the bartizans.

Although it was used for a sally during the siege of 1644, the Bar escaped damage since this side of the city was not closely invested. The gates were renewed in 1671 and 1707. (fn. 90) In 1815 part of the barbican was removed, (fn. 91) and in 1825, when a foot-way was made to the S.E., the watch house and the rest of the barbican were demolished. (fn. 92) The gates were removed and together with the old hay weighing machine from Mint Yard sold for £18. They appear to have resembled those of Walmgate Bar, with heavy moulded muntins, curved in the upper part (Pl. opp. p. 133). (fn. 93) In 1845 another side passage was made through the city wall to the N.W. and the Bar was restored at a cost of £429 for use as a house for a police inspector. (fn. 94) The existing large arch to the S.E. was made in 1861. In 1913–14 further restoration took place and use as a house was discontinued. The portcullis was put in working order and periodically lowered for public inspection. There was more extensive restoration in 1952–3 at a cost of £6,000 and in 1966 voussoirs of the inner arch and of the vaults to the passage were replaced after damage by a vehicle. The upper floors are now used by the Scouts.

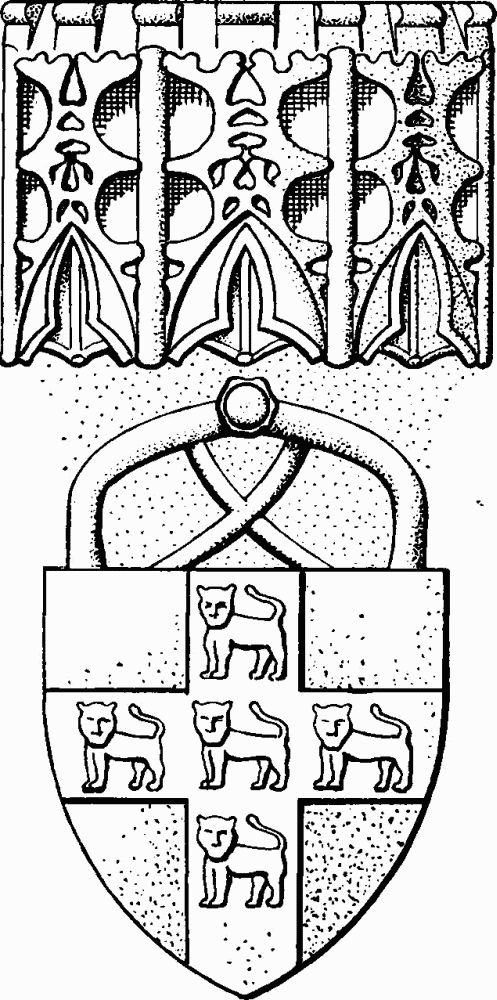

Monk Bar, Arms on N.E. Elevation

Architectural Description. The N.E. front to Monkgate (Pl. 36; Fig. p. 126) has a round-headed archway of two orders opening to the passage; some of the smaller voussoirs are of gritstone. Behind a portcullis slot is an inner arch of the same size but of a single order and with larger voussoirs. The archway is flanked by projecting buttresses with moulded and weathered plinths. On the N.E. buttress is a rectangular stone plaque carved in relief and painted with the words MONK BAR RENOVATED 1953 and with a shield of arms of the City of York below a cap of maintenance and upon a sword and mace in saltire. At first-floor level both buttresses are pierced by shoulder-headed doorways, formerly leading to the wall walk of the barbican. Over the passage archway are two cruciform arrow slits terminating in round oillets, and there is a second pair set closer together at second-floor level. Above again and 3¼ ft. in front of the main wall is a pointed arch of two chamfered orders supporting a gallery. A coffered effect on the underside of the gallery may be due to a series of 'murder-holes', now paved over. Below a string course at the floor level of the gallery and in the spandrels of the supporting arch are two shields of arms of the City of York under low canopies with crocketted pinnacles. Above the crown of the arch, on the central merlon of the parapet of the gallery, are the royal arms of England as used after c. 1405, but formerly with Old France in the first and fourth quarters. (fn. 95) The shield is depicted as hanging by a guige below a crowned helm bearing the crest of a crowned demi-lion rampant, the whole under a canopy. The flanking merlons have blocks projecting from their coping, apparently as bases for pinnacles or small statues. The face of the Bar behind the gallery is pierced by two square gunports, each with an equal-armed cruciform sighting slit above. A deep weathered band separates these from a plain parapet.

The bartizans spring, as at Micklegate Bar, from three rounded corbel courses broken at the outer angles by the corners of the buttresses below. At third-floor and roof levels they are surrounded by steeply weathered string courses and have two cruciform arrow slits at each level. On each bartizan three of the merlons support a demi-figure of a wild man holding a boulder as if to hurl it (Pl. 37). These are perhaps 17th-century, replacing earlier figures.

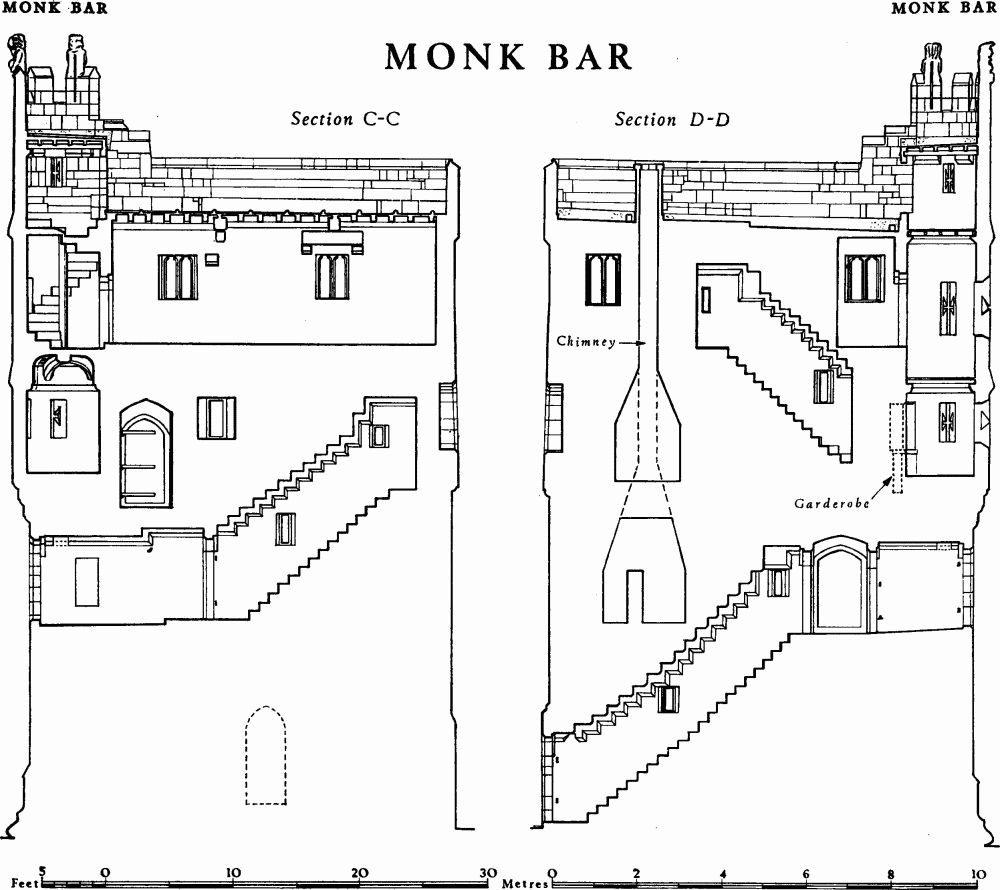

The façade to Goodramgate (Plate 37; Fig. p. 127) is ancient; it is the only rear façade of any of the major Bars to have been built originally wholly in masonry. The archway to the passage, round-headed, and of three orders on the face, is inset some 7 ft. and flanked by projecting blocks of masonry. Spanning between the blocks is a segmental arch above which a platform projects, supported on seven corbels of various forms. There is another segmental arch above the platform which is filled by a wall set back to give the platform a width of 2½ ft.; the wall is pierced by a central three-light window with mullions and high-set transom of c. 1580 which is flanked by a doorway 4 ft. high and a small rectangular window. A corbel-course marks the level of the second floor. Above this a central three-light window with trefoil heads to the lights is flanked by two empty niches; the cusped head of the right niche has been restored. The third floor is lit by two windows, each of two shoulder-headed lights, flanking a shallow trefoil-headed niche. The narrow pointedarched doorway gives access to the stairway in the thickness of the N.W. wall.

The side elevations have been much altered by the removal of the rampart for foot passages and on the S.E. by the demolition of the watch house. Variations in sizes and coursing of the masonry indicate numerous repairs. On the S.E. side prominent features are the projecting garderobe, resting originally on two chamfered corbels, and a row of small square patches of stone at the third-floor level inserted in recent years after the removal of the 19th-century iron tiebars.

Masons' Marks from Monk Bar

Inside, the through passage between the main archways is covered with an octopartite ribbed vault springing from brackets (Pl. 39). In the S.E. wall of the passage a pointed-arched doorway, now blocked, led to the demolished watch house. There are masons' marks (Fig. above) on this wall and on the N.W. wall. The rear main archway retains the hooks for the wooden gates on the city side. The through passage continuing beyond the rear archway but within the Bar has a segmental vault supported by three ribs. The staircase passage in the thickness of the N.W. wall, with a stone roof on a corbel course stepped parallel to the steps, is lit by two slits. At the head of the stairs is a square lobby with archways in all four directions; each archway could be closed by a door.

The first-floor room (Pl. 40) is lit only by the two arrow slits in the front wall and by two windows in the rear wall. It has two bays of octopartite ribbed vaulting, allowance being made for the portcullis to rise behind an arch set inwards from the front wall. When raised, the portcullis partly blocks the arrow slits. There is a wide fireplace in the N.W. wall below a straight lintel, which has cracked and is supported by a later pier. The floor is stone-flagged. In the S.E. wall a pointedarched doorway leads to a short passage to the barbican and to a straight staircase ascending in the thickness of the wall to the second floor. A garderobe recess opening off the passage retains its stone seat. The staircase is lit by two slits and roofed with stepped slabs.

The second-floor room (Pl. 40) also has a ribbed vault in two bays, a stone-flagged floor and a fireplace in the N.W. wall. In addition to the arrow slits in the front wall and the three-light window in the rear wall, there is a rectangular window in the S.E. side wall. A pointedarched doorway, at one time blocked, leads by three steps down to the wall walk on the S.E., and two other doorways, one shoulder-headed, lead to the bartizans. In front of the arrow slits is the wooden windlass with bars and sockets for raising and lowering the portcullis and, at one end, an iron ratchet and pawl to prevent slipping (Pl. 38; Fig. below). There was a similar ratchet and pawl at the other end in 1834. (fn. 96) The windlass itself is a beam 8 ins. in diameter, cut to an octagonal shape and mounted 3½ ft. above the floor. The supports now rest on a board set in the floor, but holes in the wall 9 ins. square may have held beams to support the weight. The portcullis is still in working order and after restoration in 1914 was lowered on Sundays and Bank Holidays. A pointed-arched doorway in the N.W. wall leads to an ascending staircase. Initials and the date 1617 are incised on the S.E. wall.

Monk Bar: portcullis

The E. bartizan room has a domed vault with two intersecting ribs springing from a corbel course (Pl. 39). A cross is deeply cut in the wall near the floor just inside the door, perhaps by a recusant prisoner if this cramped room may be identified as 'Little Ease'. The other bartizan has a modern timber ceiling resting on a corbel course; in the W. angle is a small garderobe, again retaining its stone seat and also a ledge behind it. The floor level in the main room has probably been altered in relation to those of these turret rooms.

The third-floor room is lit by the gunports and their sighting slits in the front wall and by two-light shoulderheaded windows in the other walls. Shoulder-headed doorways in the front wall lead to the bartizans, of which the E. is occupied by a stone spiral staircase, probably a later insertion, ascending to the roof. From the bartizans similar doorways lead to the outer gallery. The 16th-century timber roof is supported on two main trusses, but corbels built into the walls suggest a different earlier arrangement. On and near a corbel in the N.W. wall are several 17th-century graffiti.

Without Honk Bar, after drawing by H. Cave, 1803.

The roof is of low pitch and leaded. The doorways to it from the bartizans have flat lintels. The plain parapet rises in two steps to shelter these doorways, and the chimney stops at the parapet level.

The barbican (Figs. p. 42, above), demolished in 1825, projected 44 ft. in front of the Bar, and was 27 ft. wide and 17 ft. high with walls 5 ft. to 6 ft. thick. The round-headed archway of two orders resembled that of the outer archway of the Bar and was set in a plain wall below a low parapet with moulded cornice. By 1807 this had no merlons and the bartizans may have been lowered; the latter, set at the outer angles, were polygonal, supported on three corbel courses. Four slits in the parapet over the arch and two in the front walls of the bartizans appear to have been too low down for use as loopholes. There was a rear arch internally and in the centre of the N.W. wall was a narrow doorway which could be used as a sally-port. Views of c. 1820 show wooden gates in the outer archway (Pl. opp. p. 133). (fn. 97) In demolishing part of the barbican a reused 13th-century coffin lid of Milicia, wife of Jeremy de Lue, was discovered. (fn. 98) The watch house adjoining the Bar on the S.E. was a single-storeyed rectangular building, measuring 10 ft. by 15 ft., presumably added because the gatehouse was used as a dwelling or later as a prison.

Monk Bar from N.E. Watercolour by H. Earp, c. 1820.

From Monk Bar to Layerthorpe Postern the city wall (Pl. 41) is known to have been repaired in 1579, (fn. 99) and 1666. (fn. 100) It was thoroughly restored in 1871 and 1877–8, when a wall walk was added where missing. The line of the mediaeval wall near Monk Bar is slightly sinuous with numerous buttresses, indicating instability; part collapsed in 1957. When in 1858 the Board of Health Committee in order to make a new road proposed removing 158 ft. of the wall and rampart adjoining the Bar, the wall was described as ruinous. (fn. 101) The outer face is in places battered for the whole height and there are signs that at least one length has been taken down and rebuilt. An irregularity E. of the Bar may mark the site of a small tower. Internally the inner face of the Roman fortress wall within and below the mediaeval wall was cleared and exposed in 1875 and 1928, the rampart having already been removed. Some of the internal arches (Fig. above) supporting the wall walk here already existed in 1827 when George Nicholson sketched them. (fn. 102)

The parapet adjoining Monk Bar is pierced by a series of thirteen musket loops, most of which are modern rebuilds. At a point 32 ft. N.W. of Tower 31 is an unusual feature comprising, externally, a solid buttress 7½ ft. wide and projecting 3¼–4¼ ft., but internally two arched recesses, apparently garderobes, opening off the wall walk. The latter are 2¼ ft. and 2½ ft. wide, 4¼ ft. high, and 1¾ ft. deep; the N.W. one has a round hole in the floor and is railed off.

The rampart S.E. of the Bar was originally about 95 ft. wide and 14 ft. high, but the internal ground level has been lowered by 7 ft. to 8 ft. to expose the Roman wall. Miller excavated here in 1925–8. The church of St. Helen-in-Werkdyke (or St. Helen-onthe-Walls) stood near the rampart foot at about NG 60625219. It was demolished in c. 1580. A tablet commemorating the proclamation of Constantine I as Emperor in 306, allegedly at this spot, was set up by the Corporation in 1914.

Wall Walk from Tower 31 to Monk Bar, 1971.

An early 19th-century brick ice-house, now ruinous and partly filled with rubbish, is built into the outer slope of the rampart at NG 60595221. It is circular, 12½ ft. in diameter, roofed with a pointed dome, and entered from the N.E. by a passage 7 ft. long and 3½ ft. wide, originally vaulted.

Tower 30 (site at NG 60615220) was semicircular, but was removed before 1812. A 17th-century brick building stood on the wall walk at this point until the mid 19th century.

The section inside the wall cut by Miller at NG 60625219 (Profile P, Fig. opp. p. 41), (fn. 103) showed that the almost level surface visible before his excavation represented a levelling-up of the rampart. In it, as in his section G, there were three strata of 'beaten and stratified earth, consisting of a middle layer of clean soil between two layers of occupation-earth, both containing Roman debris of various periods'. Further S.E. the breach in the Roman wall adjoining the E. angle tower had been patched up with a timber stockade: 'Following the outer curve were a series of wooden stakes a foot apart', covered by a thick deposit, 'in turn covered by the tail of the early medieval bank'. (fn. 104) Miller's photographs show possible post holes some 3 ft. long and over 1 ft. across at the top above the Roman wall N. of the angle tower and outside its line at the curve. (fn. 105) If these were post holes they must have belonged to a Norman or earlier stockade.

Excavations inside the Merchant Taylors' Hall (fn. 106) (Profile Q) showed that the Hall was built over the floor of an earlier structure built on a slope, perhaps the latest phase of the rampart, which itself overlay the tail of a rampart 12 ft. nearer the city wall. The mound S.E. of the Roman angle tower is described as 'of clean hard beaten earth and only bits of Roman pottery were found in it'. (fn. 107)

Tower 31 (NG 60675214. Pl. 35, Fig. next), called in the Custodies of 1380 and 1403 'turrim super Herlothill juxta Petrehall', is semi-circular, set at a slight bend in the wall. It has a low 13th-century plinth. There are three arrow slits, the central one having a rounded oillet at the foot of the upright arm, and the others having triangular oillets. The plain parapet has only one central embrasure, but where it meets the wall there is at each side a 'pepper-pot' bartizan. These turrets are hollow, but with no openings in the sides other than a cruciform arrow slit, and each is supported on a large corbel. Like the parapet and platform, raised 2 ft. above the wall-walk, these bartizans were added in 1877–8. Previously there had been a brick summer-house on top of the tower. (fn. 108) The interior of the tower is entered by a shoulder-headed doorway in the rear wall and roofed with a shallow brick vault supported on concrete beams of 1950 and with flat stone flags. The arrow slits are splayed internally.

Tower 31 (Harlot Hill Tower)

The internal arch immediately S.E. of Tower 31 shelters an opening at the base of the wall. Externally this appears as an arrow slit with sides of recent stonework, but internally it is clearly a gunport 2¾ ft. wide and 2½ ft. high with splayed sides narrowing the opening to 1 ft. 1 in. The wall is here only 3 ft. 10 ins. thick, excluding the arches. Two apparently similar gunports formerly existed in the demolished length of wall between Tower 34 and Layerthorpe Postern and appear in a sketch of 1717 by Francis Place.

The length of rampart from the E. angle of the Roman fortress, probably a Danish addition, continues the alignment of the Roman wall for about 175 ft. and then curves to the S. It was about 100 ft. long and 19 ft. high in the latest phase, but was narrower and lower before the Merchant Taylors' Hall was built in c. 1400. The curve to the S. is continued by old property boundaries to exclude St. Cuthbert's church.

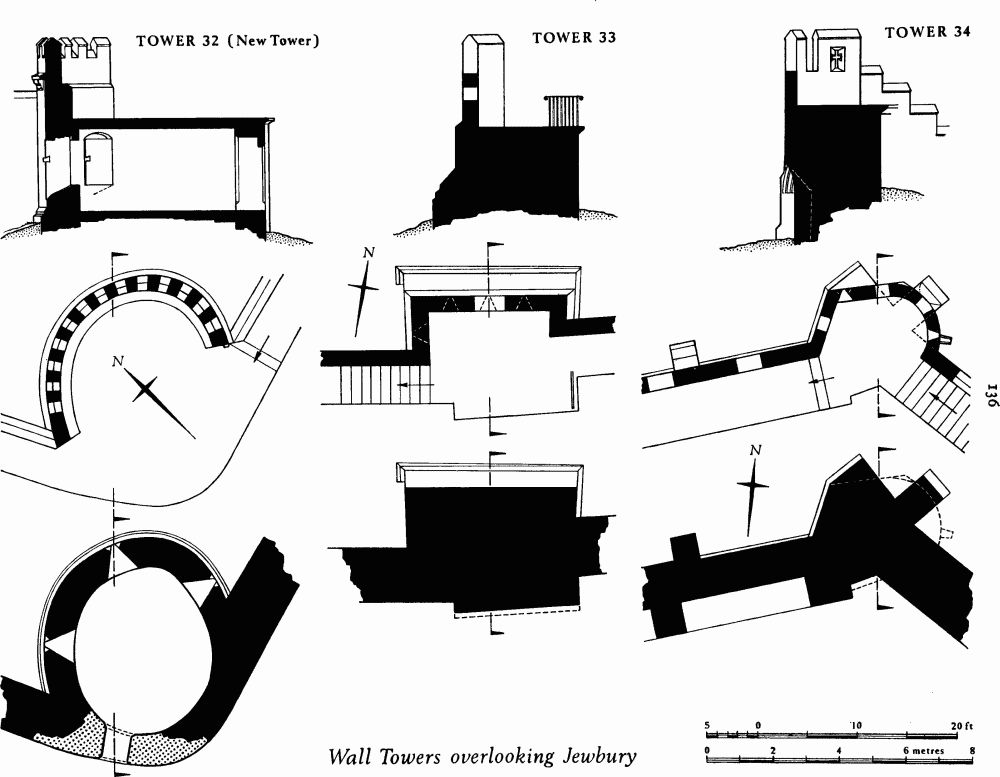

Tower 32 (NG 60715207. Pl. 42; Fig. p. 136), called in 1380 and 1403 'novam turrim super cornerium versus le Jubiry', is oval, set in the angle where the wall turns to the E.N.E. It has a chamfered plinth and three arrow slits with fish-tailed lower arms set close to the ground. A stone above the plinth on the E. bears a mason's mark, and a reused block has the side arm of an arrow slit. The lower part of the parapet is older than the 19th-century upper part, which has small merlons and an added external string course supported on corbels of 14th-century type. The interior is entered by a square-headed doorway and the arrow slits are set in splayed recesses with rough half-domed heads within segmental arches. Until 1851 the rear of the tower was open and there were the remains of a half-timbered building on top. (fn. 109) The present flat concrete roof was made in 1950 to replace the brick vault of 1871, which had partly collapsed.

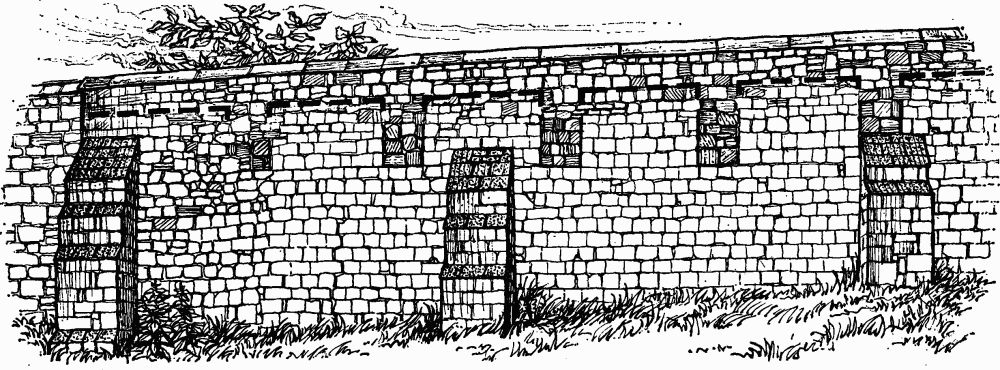

Bonded into the city wall near Tower 32 are four low shallow original buttresses, each 4½ ft. wide, 4 ft. high, and projecting 3 ins. to 6 ins. Further E. is a taller strip buttress. There are also four blocked embrasures between Towers 32 and 33 (Fig. below), indicating that the level of the wall walk has been raised by about 7 ft. This is evidence that the original stone wall here was only about 6 ft. high to the wall walk and that it has been gradually built in stages. When the blocked embrasures were in use they would have been well below the crowns of the arches supporting the wall walk. There are forty-seven of these arches in this stretch, most of which appear to be 19th-century since they often rest on brick footings and are not bonded into the wall. However, arches existed in 1634 near Layerthorpe Postern, when it was proposed to remove them for building stone. (fn. 110) They also appear on an engraving of 1718, and some of those now visible may be earlier than that date. Those near the Layerthorpe end of the wall, which are most likely to be ancient, measure 14¾ ft. wide, 8¾ ft. high, and 4½ ft. deep, and are larger than those nearer Monk Bar.

In the stretch of rampart running E.N.E. from Tower 32 towards the Foss, including St. Cuthbert's church, the mound gradually decreases in height and disappears entirely at Tower 34, but it is still traceable as a slight rise from the churchyard, where it is 85 ft. wide and externally 15 ft. high with an outer ditch 35 ft. wide and 2 ft. deep.

City Wall between Tower 32 & 33: original profile with later blocking and buttressing

Wall Towers overlooking Jewbury

Tower 33 (NG 60785209. Fig. p. 136) is rectangular, with a great chamfered plinth and a weathered setback. It is roughly finished with some sandstone blocks among the limestone. In the parapet are three musket loops at the front and one on the S.W. The solid platform projects internally but is offset to the E. of the external projection. This tower does not appear on any plan before 1812, but it is probably a late mediaeval addition to the curtain wall.

Tower 34 (NG 60805209. Pl. 42; Fig. p. 136), only 45 ft. from Tower 33, is perhaps that called 'Lathorp Towre' in 1370. (fn. 111) It is set at an angle, with straight sides to the W. and N. and a curve to the E. and S.E. It is unusual in being without a solid base and supported on two buttresses and, between them, to the E. a pointed arch of five orders, resembling those on the mediaeval Layerthorpe Bridge, and to the S.E. six reused corbels, the earliest of the 12th century. This arrangement may be due to soft ground near the river Foss and may indicate that the curved part is later, though the buttresslike supports rather suggest hasty repairs, possibly after or during the Civil War. There are two cruciform arrow slits in the merlons of the parapet, and a stone spout draining the platform projects to the S.E. On drawings of 1717 and 1808 it had the present appearance, but Archer's plan of c. 1682 shows it square, and in 1822 a gabled brick building stood on top. (fn. 112)

Layerthorpe Postern or Peasholme Green Postern (site at NG 60825207. Pl. 43) is first mentioned in 1280 (fn. 113) and occurs in all three Custodies. The gates were repaired in 1453–4. (fn. 114) The city mason Christopher Walmesley superintended work upon it and on the adjoining bridge in 1568 and 1580. (fn. 115) A lease granted to John Criplinge in March 1604 mentions his intention of building over the postern and making it habitable, and a longer lease of May 1605 states that he had lately built a house over the gate at his own expense. (fn. 116) The passageway was narrowed in 1723 to prevent the entry of vehicles, (fn. 117) and widening was considered in 1727 (fn. 118). By 1820 the postern was in a very dilapidated and dangerous state: consequently the gates, floors and roof were removed. (fn. 119) The keystone of one of the arches had later to be wedged up and secured. (fn. 120) In 1829–30 the postern was demolished when Hiram Craven and Sons rebuilt the bridge at a cost of £1,358. (fn. 121) During this work a 10th or 11th-century coin hoard and a mediaeval Jewish amulet were found near the postern. (fn. 122)

The postern consisted of a passageway with arches at each end within a rectangular tower 26 ft. by 20 ft. externally. The arches were 9 ft. wide and pointed, with labels and stops around them. Stepped buttresses projected parallel to the rear wall at the angles of the side towards Peasholme Green. A narrow crenellated rise in the parapet of the adjoining city wall sheltered a pointedarched doorway leading from the first floor of the tower to the wall walk. The room over the passage was lit by a small window over the outer arch and by two rectangular windows in the rear wall. Originally there was a flat roof, marked externally by a string course, and with a crenellated parapet above, but by 1700 the tower had a gabled roof with windows in the embrasures and a S.W. chimney, no doubt added by John Criplinge.

The Fishpond of the Foss once filled the gap between the end of the wall at Layerthorpe Postern and the beginning of the Walmgate defences at the Red Tower. It formerly extended N.E. along the river from the Castle Mills, with a W. arm which ended at St. Mary's Abbey mill 340 yds. N. of Monk Bridge, and an E. arm along the tributary Tang Hall Beck to about NG 614520, where a wooden cross marked the limit. It was formed in c. 1068, when William I dammed the Foss as a protection for the more important of his two castles. Domesday Book records that 'the King's Pool destroyed two new mills worth twenty shillings and of arable land and meadows and gardens fully one carucate'.

Keepers were appointed, mostly from yeomen of the court. Bream and pike are mentioned in grants of fish. Apart from the keepers, the only persons allowed to have a boat on the pond were the Carmelites, who were granted this right in 1314 with permission to build a quay, and the wardens of Foss Bridge, who needed access in 1393 for repair work. In 1545 the pond and fishery were granted to the Nevilles of Sheriff Hutton and in 1685 to the Ingram family. The level of the water was controlled by sluices in the dam at the Castle Mills in 1577 the miller was accused of keeping the Foss either above the high water mark on the dam wall or below the low water mark, thus either flooding adjacent gardens or killing the fish. (fn. 123) In 1584, when the banks were thoroughly cleaned, a complaint of rubbish dumping mentions the swans' nests as a landmark on the bank. The penalty for depositing rubbish in the pool or on its banks was £100.

By the time the pond first appears on maps of the city in the 17th century it had probably shrunk from its largest extent. Horsley's map of 1694 already marks the Foss Islands separating the main streams of the Foss and the Tang Hall Beck between Layerthorpe Bridge and the Red Tower. The last traces of the marsh, which the former fishpond eventually became, did not disappear until the 19th century.

In 1792 the Foss Navigation Company was formed and an Act of Parliament was obtained 'for making and maintaining a navigable communication from the junction of the Foss and Ouse to Stillington Mill'. (fn. 124) Some £45,000 was spent, as against W. Jessop's original estimate of £16,274, but only 14 miles of the river were ever made navigable. After further borrowing powers were granted in 1801, the company was at last able to make a profit in 1808, when income of £1,446 from tolls and rents amply exceeded expenditure of £367. In 1810 a first dividend was paid, and it was planned to extend the navigation upstream to Sheriff Hutton.

In 1853 York Corporation bought the company for £4,000, following a report which attributed recent outbreaks of illness in Layerthorpe to exhalations from the Foss. At the same time the Corporation bought Foss Islands with the fishing and fowling rights for £1,500. Instead of removing Castle Mills Lock and moving the first lock to Monk Bridge or of covering over the river from Layerthorpe Bridge to the Ouse, as reports had recommended, it was decided to raise the level of the marsh and to encourage the dumping of rubbish there by payments for each cart load. The water in the river was purified by emptying each level and refilling from a higher level. A drain was made in the moat at the Red Tower and a sewer was constructed 13½ ft. below the surface of the new Foss Islands Road. This road replaced a precarious footpath over the islands, often made impassable by floods.

In 1856 Castle Mills were demolished and the new St. George's Wharf was built near by. In 1859 a new and larger lock was made there. Another Act of Parliament had also been obtained by which the Corporation could abandon the navigation from a point 200 yds. above the workhouse in York up to Sheriff Hutton Bridge but must maintain the reservoirs at Oulton Moor. These reservoirs still exist and there are traces of the abandoned channel above Strensall. Within the city some of the original work of Yearsley Lock remains but the bridges have all been widened.