Ancient and Historical Monuments in the City of Salisbury. Originally published by Her Majesty's Stationery Office, London, 1977.

This free content was digitised by double rekeying. All rights reserved.

'Sectional Preface', in Ancient and Historical Monuments in the City of Salisbury(London, 1977), British History Online https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/rchme/salisbury/xxv-lxiv [accessed 27 April 2025].

'Sectional Preface', in Ancient and Historical Monuments in the City of Salisbury(London, 1977), British History Online, accessed April 27, 2025, https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/rchme/salisbury/xxv-lxiv.

"Sectional Preface". Ancient and Historical Monuments in the City of Salisbury. (London, 1977), British History Online. Web. 27 April 2025. https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/rchme/salisbury/xxv-lxiv.

In this section

SALISBURY I

SECTIONAL PREFACE

DOCUMENTARY SOURCES

In compiling the Inventory much use has been made of documentary material, both published and unpublished. Almost all published matter is included in the list of works frequently cited (p. 175), where also early maps are listed. Documents used in connection with particular monuments are identified as far as possible in notes at the end of the relevant entries; however, as new catalogues are now being compiled, these references can only be provisional. Unpublished matter consulted for the Inventory includes mediaeval deeds, wills and account rolls, and many later minute-books, leases, lease-books, surveys, terriers, maps and plans. Most of these are now in the care of the County Archivist, being either in the Record Office at Trowbridge, in the Diocesan Record Office at Salisbury, or among the city archives in the Council House. For the present volume, the last-named has proved the most valuable of the three collections.

The main use of the documents has been in elucidating the history of individual tenements. Inevitably the survival of documents has been as uncertain as that of buildings. At a few sites documentary evidence and architectural evidence are mutually illuminating, but it happens all too often that an interesting building has no documentation while the history of an adjacent site, now vacant or occupied by some modern structure, is illustrated by a long sequence of deeds. It has not been possible to trace the history of any tenement back to a date before the late 13th century. The student of Salisbury history is hampered by lack of early documents, but a lifetime might be spent sorting out evidence which survives from the late 14th century and subsequent periods.

Normally the identification of a tenement is only possible when a considerable number of surviving deeds relates to a known length of street frontage (defined by fixed points, such as two angles of a chequer) or where a notable landmark such as a watercourse or a well-known inn is mentioned; we are able to say little about long frontages such as New Street, the W. side of Castle Street, the N. side of Bedwin Street, or the W. side of Catherine Street. Our method has been to compile the descent of a tenement from owner to owner, making use of evidence from the deeds of neighbouring tenements, of which the owners' names are nearly always mentioned. In general, the research worker is often surprised at the large size of mediaeval tenements and at the persistence of their boundaries over many years and even centuries.

Most of the identifiable tenements belonged at some time to corporate landlords, the continuity of this kind of ownership making such properties easier to identify; the bulk of the records moreover emanate from these corporate bodies. Among the largest mediaeval landowners in Salisbury were the Mayor and Commonalty (the Corporation after 1612), the Dean and Chapter who administered both the Fabric Fund of the Cathedral and the Common Fund of the Canons, the Vicars Choral, the Choristers of the Cathedral, the College of St. Edmund, De Vaux College, Trinity Hospital, St. Nicholas's Hospital, and the trade guilds, especially the Tailors' Guild. From all these bodies some documentation of property has survived, in some cases in great quantity. St. Edmund's College, dissolved at the Reformation, has left few records although it certainly owned important tenements. By contrast a full cartulary survives in the British Library (Add. MS. 28870) for De Vaux College, which owned several tenements in High Street near the Close gate. Lists of 'corporations' appear in seven episcopal quit-rentals from c. 1650 to 1781 and confirm that only minor changes took place in the number and value of their tenements during that period (Sar. D. & C.M., Ch. Commrs. Docs., 13678881–7). The bishop himself owned few tenements, but he collected quitrent from every householder in the town. The rental for 1455 in Bishop Beauchamp's Liber Niger is one of the few surviving documents to provide a general conspectus of the mediaeval town.

By the common mediaeval practice of founding a chantry or obit many private owners became benefactors of the corporate landlords, to whom they bequeathed tenements for the endowment of their pious foundations. Their names appear in the obit calendar of the cathedral (Wordsworth, Statutes, 3–16), in the bede roll of the merchant Guild of St. George (Benson & Hatcher, 133) and in the bede roll of the Tailors' Guild (Haskins, Guilds, 130; W.A.M., xxxix (1916), 375).

Once a tenement had become the property of a corporate landlord (often in the 15th century) its subsequent history was recorded in a great variety of records: leases and lease-books from the 16th century onwards; surveys and terriers from the 17th century onwards; maps and plans of the 18th and 19th centuries. Many plans of individual tenements were made in the 19th century when the property was leased to a new tenant or sold into private ownership. The survey of the city, scale 1:500, made in 1854 by Kingdon & Shearm, engineers, in preparation for the installation of modern sewers, includes a valuable record of the former watercourses.

The documents which have proved most useful in the compilation of the Inventory are listed below.

Salisbury City Archives (Council House muniment room) (fn. 1)

1. Records concerning miscellaneous properties:

Domesday Books. Four MS. volumes containing transcripts of documents, mainly deeds and wills, witnessed in the court of the subdean by the bishop's bailiff, the mayor, other officials and citizens. Vol. i, 1357–68; vol. ii, 1396–1413; vol. iii, 1413–33, together with a register or short list of conveyances from 1317–40 and 1355–1422; vol. iv, 1459–79.

Deeds, 1270–1830, filed chronologically; also a few wills. Many of these documents refer to tenements which later became city property.

General Entry Books or Ledgers. The minutes of the meetings of the city council from 1387 to 1836 are preserved in eight MS. volumes which supply much general information such as market, watch-and-ward, and building regulations, as well as grants of leases and records of repairing and rebuilding city properties.

Ward Taxation Lists. A roll of contributors' names with the sums contributed. Formerly dated to the late 15th century, this roll is now firmly assigned on internal evidence to the year 1399 or 1400. (fn. 2)

2. Records concerning properties of the Mayor and Commonalty:

The Chamberlain's Account Rolls, 1444–1527. Eleven rolls.

Register of Leases (temp. Ed. IV). The register contains several important items, notably a roomby-room list of 'implements and necessaries' belonging to the George Inn in 1474.

Grammar School Deeds, 1575–1631. Title deeds of the house (423) in Castle Street where the school originated.

Leases, 1647–1904. Forty-five bundles of leases relating to city properties.

Surveys and Terriers. A series of volumes containing abstracts of title etc. Vol. 1 contains leases from c. 1590 to c. 1675; at the end, on unnumbered folios, a complete survey of city lands for 1618 gives dimensions of tenements in poles and feet. Vol. 4 (1672–1716) includes a survey of 1716 with lists of rooms in each building and dimensions of plots in feet and inches; at the end of the volume are transcripts of deeds of sale of city properties which took place between 1649 and 1657 under the Commonwealth. Vol. 8 (1783–1835) repeats much of the information of vol. 4 in a survey made in 1783. It includes names of 18th and 19th-century lease holders.

Plans of City Properties, c. 1850–70. Two volumes of ground-plans drawn by J.M. and Henry Peniston, County Surveyors. The first volume includes an undated plan of the George Inn by F.R. Fisher (Plate 13), the only known plan of the mediaeval inn. The second volume is largely a fair copy of the first, but it omits Fisher's plan of the George and, unlike the first, it includes an abstract of the Corporation Terrier of 1865; there are also a few additional plans of properties.

3. Records concerning properties of other corporate landlords:

Trinity Hospital. All the records of this ancient foundation are in the Council muniment room, including deeds from 1300, account rolls from the mid 15th century onwards, many late leases and 19th-century terriers. An article by T.H. Baker (W.A.M., xxxvi (1910), 376) contains transcripts of several inventories and other documents.

The Tailors' Guild. This trade guild owned more property in the city than any other and was the only one to retain a sizable corpus of records. Its muniments include deeds from 1307 to 1815, a 'Survey of Lands of the Taylors' made in 1657, and plans (additamenta 29 and 32) of six tenements drawn in 1823 by W. Sleat, architect.

Parish Deeds. Some 19th-century deeds of St. Thomas's parish help to explain various changes made during that period to the churchyard and footpaths around St. Thomas's church.

The Diocesan Record Office

1. Chapter Records (formerly in the Cathedral Muniment Room):

Parliamentary Survey of Church Lands, 1649. From this most useful document it is possible to identify nearly all of the tenements (many described room-by-room and with some dimensions) owned by the four ecclesiastical corporate landlords: the Dean and Chapter or Common Fund of the Canons; the Cathedral Fabric Fund administered by the Clerk of Works; the Vicars Choral; and the Choristers.

Deeds and Wills. Several boxes of mediaeval deeds and wills relating to Salisbury properties and to the tenements of the four corporate landlords (see above) are among the Chapter records. A number of these documents relate to properties of the Harding family, one of whom was Cathedral Clerk of Works in the 15th century. Among the Vicars Choral deeds is a terrier for 1671–2.

Lease Books. The Vicars Choral lease book 1673–1717 includes a copy of the terrier mentioned above. From further study of the Chapter lease books it would be possible to trace the history of some tenements throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, but we have done this only occasionally.

2. Records formerly in the care of the Church Commissioners:

Deeds. These include a few mediaeval deeds and a great number of later leases relating to church properties. They include properties of the bishopric.

Plans. A volume of mid 19th-century plans entitled 'Salisbury Chapter Estates', perhaps by the Penistons, contains useful material. One drawing shows the line of Bridge Street before its widening.

Wiltshire County Record Office

The collection of plans and other papers from the offices of the Peniston family, Surveyors, 1822– 64, was of great value in compiling the Inventory. A few mediaeval deeds in W.R.O. have also been consulted.

H.M.B.

HISTORICAL SUMMARY

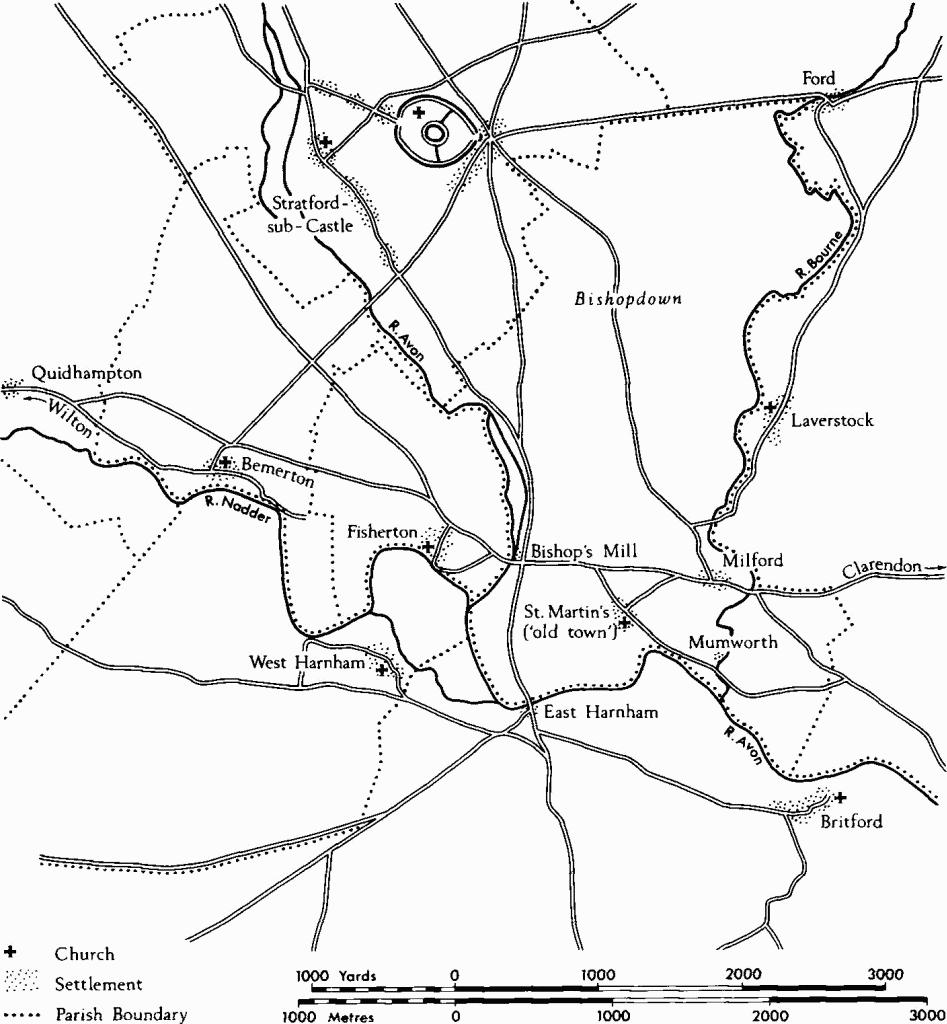

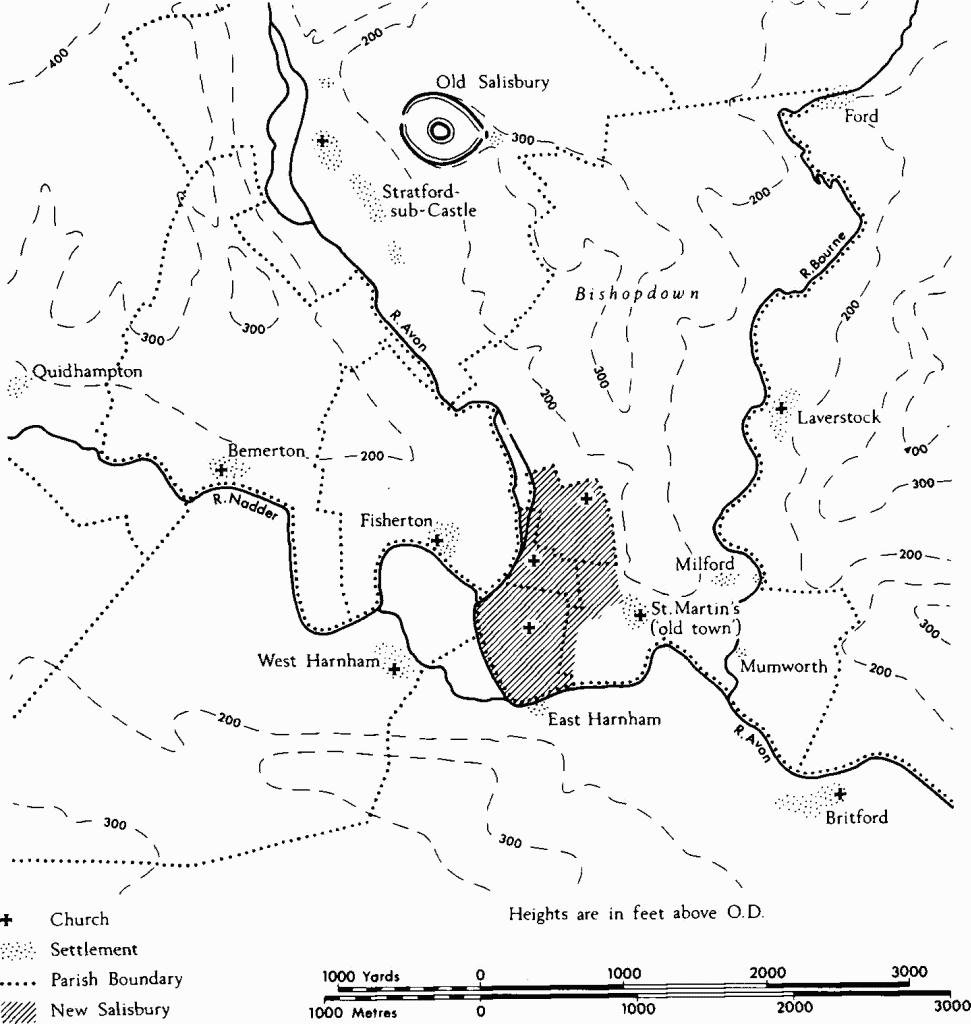

Salisbury lies at a confluence of rivers: the Nadder from the Vale of Wardour to the W., augmented by the Wylye at Wilton, and the Avon and the Bourne from the chalk uplands of Salisbury Plain to the north. The alluvial plains of the valleys, about 150 ft. above O.D. in the vicinity of the city, are bordered by continuous gravel terraces of varying width from which the Upper Chalk rises, often steeply, to over 300ft. above O.D. in the adjoining spurs and ridges. The pattern of rivers and intervening ridges has led to a concentration of routes, especially upland routes, and river-crossings in the area, while the gravel terraces have provided suitable sites for nearly all the post-Roman settlements and notably for the city of New Salisbury itself.

EARLY DEVELOPMENT

The logical starting point for any consideration of the evolution and development of the various Salisburys is the Iron Age Hill-fort at Old Sarum, the presence of which had so obvious an impact on local history, and the influence of which may be said to have persisted down to the Reform Act of 1832. As a major defensive work the hill-fort presumably functioned as an administrative centre for the surrounding area during the Iron Age, though the limits of the territory under its control and protection remain unknown. After the conquest some element of this administrative role may well have been retained by the Romans. The settlement, which came to be known as Sorviodunum, clearly takes the latter part of its name from the hill-fort, (fn. 3) but it does not necessarily follow that it lay within the Iron Age defences. The general paucity of Roman finds from the site suggests otherwise, although the raising and levelling of the interior in the Norman period has inhibited exploration of potential Roman levels. The recent discovery of a substantial Roman settlement a short distance to S.W. in the present village of Stratford-sub-Castle raises the possibility that this is Sorviodunum. It lies astride the Roman road from Old Sarum to Dorchester at the point where it crossed the R. Avon, and finds indicate that it was inhabited from the conquest down to the 4th century. Other evidence of occupation in the Roman period, in the immediate vicinity of Salisbury, is at present limited; most finds have been made along the ridge extending S.E. from Old Sarum, especially around Paul's Dene.

A number of Roman roads met on the E. side of Old Sarum which, because of its prominent position, served as a sighting point for the Roman surveyors. These roads continued to be used long after the Roman period; even today, in the vicinity of the hill-fort, metalled roads follow the line of the earlier roads to Winchester and Silchester; a third probably corresponds with a road which led northward to Cunetio.

The only historical event which may be confidently associated with the Salisbury area in the immediate post-Roman period marks a stage in the growing ascendancy of the Anglo-Saxon settlers over the native Britons. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle records (s.a. 552) 'In this year Cynric fought against the Britons in the place which is called Searoburh and put the Britons to flight'. Searoburh without doubt refers to the hill-fort at Old Sarum, and a battle there suggests use of its defences, though whether by Briton or Saxon remains unknown. The capacity of the hill-fort to control a major junction of Roman roads immediately outside it may well have been significant in this encounter. Material evidence from the sub-Roman and early Saxon period at Old Sarum is equally sparse, comprising a 5th-century belt-fitting and a 7th-century silver sceatta.

For the Salisbury area generally, however, there is substantial evidence of pagan Saxon occupation, though almost entirely in the form of burials. Most of these occur in cemeteries, and it is cemeteries in particular which indicate the presence of settled communities nearby. The cemeteries at Harnham Hill, St. Edmund's churchyard, Petersfinger (fn. 4) and Winterbourne Gunner (fn. 5) all lie on the lower slopes of the valleys; along the margins, but usually just above the gravel terraces. Probably all of them were in existence by the early 6th century and some possibly even earlier. Finds (fn. 6) from the vicinity of Dairyhouse Bridge suggest the possibility of early Saxon settlement near the con fluence of the Bourne and the Avon, on or near the site of the former hamlet of Mumworth. Two burials, probably of the late 5th century and perhaps part of a cemetery, were found together in a pipe-trench immediately N.W. of Old Sarum. (fn. 7)

The later Saxon period, too, is thinly represented archaeologically at Old Sarum; a circular bronze brooch ascribed to the late 9th century and silver pennies of Athelstan (925–40) and Edgar (959–975) represent the total of finds dating from before the beginning of the 11th century. There is some hint that, by that time, the ravages of the Danes in southern England had made it necessary to refurbish the defences of Old Sarum so that they might serve as a military strongpoint and as protection for those who dwelt in the locality, together with their goods and livestock. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle (s.a. 1003) records that Swein 'led his army into Wilton, and they ravaged and burnt the borough, and he betook him then to Salisbury and from there went back to the sea ...'. (fn. 8) That Salisbury should have been visited, though the Chronicle is silent about the purpose and the outcome of the visit, raises suspicion that it was more than a few villages on a large rural manor. What is beyond dispute is that immediately after this time a number of moneyers formerly associated with Wilton are to be found coining at Old Sarum, and that a mint continued there until the reign of Henry II. Possession of a mint was one of the normal attributes of a borough, and under Athelstan's laws was one of the necessary qualifications for burghal status. There is a slight suggestion from excavations across the inner rampart on the N.E. side that the defences were remodelled before the Norman Conquest.

A possible date before which any substantial reoccupation of Old Sarum might be regarded as unlikely is A.D. 972. In that year a charter, granting an estate which appears to coincide with the later manor of Little Durnford, refers to a length of the present road between Amesbury and Old Sarum as 'the way which runs from Amesbury to Alderbury'. (fn. 9) This old road came as far S. as Old Sarum and then turned S.E. towards the crossing of the R. Bourne at Milford. The description suggests that no place of importance lay along the road between Amesbury and Alderbury.

OLD SALISBURY AND OLD SARUM

By the Norman Conquest the general picture of the Salisbury area appears to have been as follows: Old Sarum was occupied as some kind of borough or fortified settlement which lay, presumably, entirely within the defences and was under royal control. It seems to have been one of the two most important minting-places in the shire and, therefore, probably one of its most advanced trading centres. (fn. 10) Stretching on either side of it, to N. and S. along the Avon valley, lay a large estate, nearly nine square miles in extent, in the possession of the Bishop of Ramsbury and Sherborne. Essentially it comprised the later parishes of St. Martin's, Stratford-sub-Castle and Woodford. Of the earlier history of this estate, when it was granted to the Church and whether as an entity or piecemeal, nothing is known. It has been suggested that it was a royal benefaction of a date not later than the early 10th century. (fn. 11)

So large an estate must have comprised several settlements or vills, but these did not begin to be recorded by name until the end of the 11th century, by which time many of them must have been in existence for several centuries. In Domesday Book the whole estate, assessed for some 50 hides, is described collectively under Salisbury (Sarisberie) (fn. 12) and it is, therefore, impossible to distinguish geographically its component settlements. It is, however, clear from Domesday Book that the essentially riverine pattern of mediaeval and later settlement in the neighbourhood of Salisbury, so characteristic of the chalklands throughout Wessex, was already well developed by the mid 11th century and there is no reason to suppose that this pattern did not continue within the bishop's estate. Its N. part, represented by Woodford, is of no immediate concern. The central part developed into a manor and parish around the settlement of Stratford, a name first mentioned in 1091 (fn. 13) and one descriptive of a position at or close to the point where the Roman road to the S.W. crossed the R. Avon. The borough at Old Sarum lay within this part of the estate and acquired certain of its lands, probably during the 11th century. The remainder of the bishop's estate lay to the S. and E., between the Avon and the Bourne. Before the foundation of New Salisbury in the early 13th century the whole of this area lay within the parish of St. Martin. It too became a separate manor and from the early 14th century onwards was usually known as the manor of Milford, but it was also known as the manor of Salisbury at least until the late 14th century. The chief settlement of the manor, sometimes referred to as 'the old town', lay close to St. Martin's church, mostly along the way leading to it from the N.W. Further E. lay a second settlement, Milford, on either side of an important crossing-point of the R. Bourne; only that part of it on the W. bank of the river lay within the bishop's estate. A third settlement may well have existed on the W. side of the manor, close to the bishop's mill, beside the R. Avon. These settlements, of which only that at Milford developed a distinctive name, are presumably included among the veteres Sarisberias mentioned in a papal bull of 1146, a collective phrase probably intended to describe all the vills on the bishop's estate. Later in the 12th century the term Old Salisbury occurs in the Pipe Rolls; it is used apparently to distinguish the bishop's estate, and perhaps the southern part of it in particular, from the borough of Salisbury at Old Sarum.

Roads, settlements etc. before 1220.

The founding of New Salisbury disrupted the existing pattern. St. Martin's church and the old settlement around it were left on the very edge of the new town and soon became a form of extramural suburb; any settlement which might have existed beside the bishop's mill would have been absorbed into the town itself. Milford, on the other hand, lay at a distance from the town sufficient to retain its separate identity.

The history of Old Sarum, by contrast with that of the bishop's estate, was altogether more eventful. The rapid establishment of a royal castle and the seat of a bishop in the years immediately following the Norman Conquest led to substantial changes of both a physical and an administrative nature within the Saxon borough. The castle founded by William I appears to have been in use by 1070 at the latest. It became the sheriff's headquarters and was visited frequently by the early Norman kings. It was here, for example, that the famous meeting of the king's council took place in 1086, at which all the major landholders in England took an oath of allegiance to the king. The castle was built within the hill-fort, on the highest part of the spur, where it dominated the surrounding countryside as do its remains even today. A massive ring motte, set within an impressive ditch, was erected in the centre of the enclosure. The bailey comprised the whole of the E. part of the hill-fort, the defences of which were greatly strengthened. The first castle buildings were almost certainly of wood; the remains of the earliest stone buildings, the Great Tower and the Courtyard House, date respectively from the late 11th and early 12th century.

In 1075 the Council of London decreed that the seats of certain bishops should be transferred from villages to towns; the Anglo-Saxon rural cathedral was an anachronism in Norman eyes. The central churches of the sees of Lichfield and Selsey, for example, were to be moved to Chester and Chichester; and that of the bishop of the combined dioceses of Sherborne and Ramsbury, brought together as recently as 1058, was to be moved to Old Sarum, or rather the Borough of Salisbury as it would have been known at the time. William of Malmesbury, in writing of the event, clearly considered Old Sarum an odd choice for a bishop's seat, declaring it a castle rather than a city. (fn. 14)

The transfer to Salisbury took place under Bishop Herman, but the building of the first cathedral church, completed in 1092, was the work of his successor, Bishop Osmund (1078–1099). The new church was sited outside the castle defences but within the N.W. quadrant of the hill-fort, an area which was levelled up to receive it and which appears to have comprised the ecclesiastical precinct, or a substantial part of it. Bishop Roger, nominated in 1102 and consecrated in 1107, planned to rebuild the entire church on a larger and grander scale. He finished the E. end, the transepts and the crossing, but the treasure which he had provided for the completion of the work was siezed after his disgrace in 1139 and the old nave remained standing. Roger also obtained custody of the castle, probably soon after 1130, and is said to have surrounded it with a wall, probably the unfinished stone wall of which foundations remain on the line of the inner rampart of the hill-fort. This effectively enlarged the castle to include the ecclesiastical precinct, an act which was to prove a recurrent source of trouble to the clergy.

Little is known of the civil part of the borough until the 12th century. Coins continued to be minted there until the reign of Henry II and it may be presumed to have possessed a market, although one is not mentioned until 1130. Henry I granted a charter to the burgesses of Salisbury, giving them a guild merchant. (fn. 15) There is no evidence that any part of the civil settlement lay within the defences in Norman times; although much of the interior has still to be investigated archaeologically it seems likely that most of the settlement lay outside the defences, on E., S. and W., in the areas of so-called 'suburbs' ((1), p. 12). In support of this is a map of c. 1700 which shows the burgages of Old Sarum outside the E. gate and on either side of the Portway, as far as the R. Avon on the south. Bishop Osmund's charter of 1091 provided land for the canons' houses and gardens ante portam castelli Sarum. (fn. 16)

The borough of Salisbury is likely to have declined in importance as the 12th century advanced. (fn. 17) Despite attempts to sustain it in the 13th century, rapid decline set in with the departure of the bishop and clergy, c. 1219, and in the face of strong competition from the growing town of New Salisbury. Old Salisbury as it soon came to be known, and eventually Old Sarum, was a military borough and, unlike its successor in the valley below it, had not been planned and sited with the needs of trade and industry primarily in mind. The Poll Tax returns of 1377 demonstrate the relative positions of the two boroughs: New Salisbury has a recorded (not total) population of 3,226; the comparable figure for Old Sarum is 10. (fn. 18)

NEW SALISBURY

Two separate but closely connected aspirations may be presumed to have come together in the removal of the cathedral and clergy from Old Sarum and in the foundation of a new town 1½ miles to the south. The more obvious and pressing was the desire of the clergy to move to a more commodious site from the generally inhospitable environment of Old Sarum, where even water had to be brought at high cost from a distance; and in particular to leave their inconvenient quarters in the castle, where their movements and those of pilgrims were subject to interference by the castellan. Less obstrusive was the wish of the bishop and clergy, presumably supported by many of the citizens of Old Sarum to establish a new town in the fashion of the times, in which the privileges granted to the inhabitants would provide increased incentive to trade and where tolls would make a welcome addition to the revenue. The first of these aspirations may to some extent have provided a pretext for the second.

The idea of removing the cathedral church from Old Sarum to the site by the R. Avon appears to have originated during the episcopate of Herbert Poore (1194–1217) and to have been effected during that of his successor Richard Poore (1217–1228). According to the compiler of St. Osmund's Register, Richard I gave his approval to the scheme. By 1213 precise plans for the layout of the buildings in the Close are evident in the Chapter decrees. Pope Honorius III was petitioned in 1217 and the bull authorizing the transfer was issued in March 1219. Immediately, a churchyard was consecrated and a temporary wooden chapel erected to serve during the construction of the new cathedral, on which work began in 1220. A residence for the bishop, referred to as ad novum locum, may have been built by 1219. In the same year a license to hold a market on the new site was obtained from the king, and thereafter was renewed for short periods from time to time; by 1224 it was referred to as the Market of New Salisbury. In 1221 the bishop obtained a grant of an annual fair. Both grants were confirmed in the royal charter of 1227. The latter emphasized the ecclesiastical nature of the foundation and granted the bishop and his successors the right to hold the city as their demesne in perpetuity. It also declared New Salisbury a free city and granted its citizens all the liberties enjoyed by the citizens of Winchester.

In 1225 Bishop Poore granted a charter in which he set out the conditions of tenure within his city. The citizens were to hold their tenements by what amounted to burgage tenure, although it was not so described. (fn. 19) The standard plot was to be seven by three perches, or about 115ft. by 50ft. - an ample size, in keeping with the character of the whole scheme-and the standard ground-rent was to be 12d. a year. Tenants who held more or less land than that were to pay more or less rent accordingly, so it is evident that from the very outset the tenements were expected to vary in size. The plan of streets and chequers was in part laid out to accommodate standard plots and a few such plots are still traceable today.

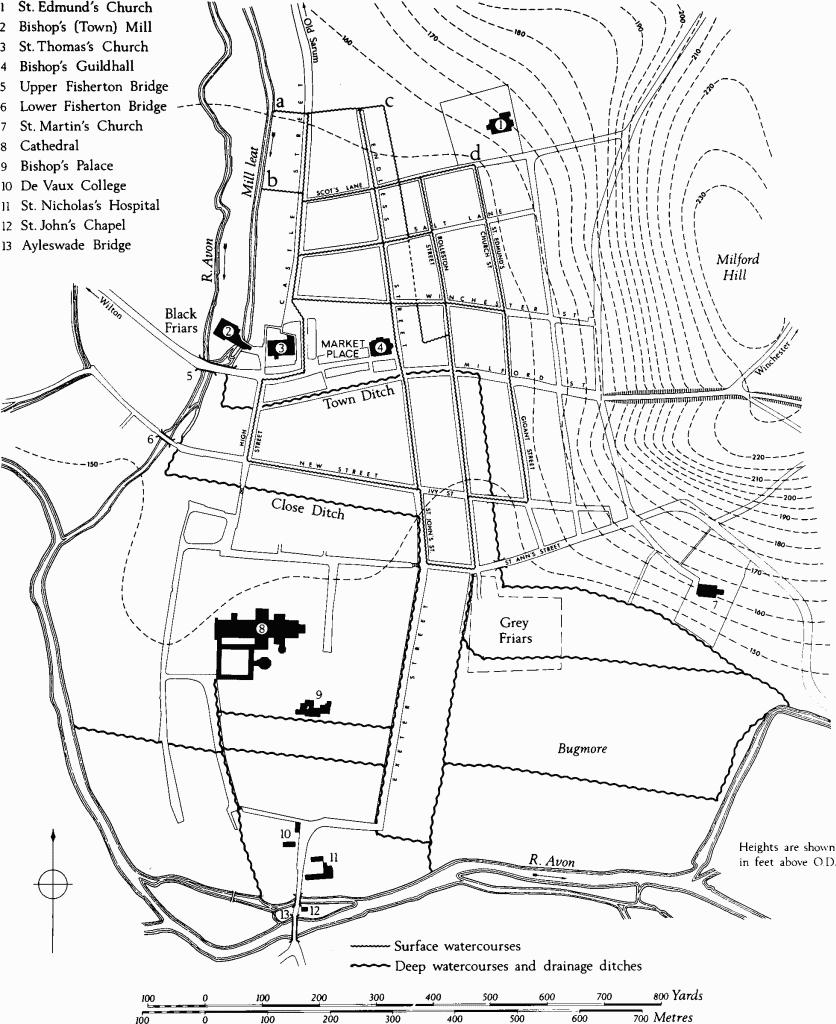

Siting and Layout. As in a number of other new towns of the 12th and 13th centuries, the layout of New Salisbury was on a generous scale, manifest in the ample proportions of its tenements, of its streets and, above all, of its market place. The urban area was unusually extensive; about 260 acres (105 ha) of the bishop's land was set aside for the new city, of which the Cathedral Close occupied approximately 83 acres (34 ha) and the fully-developed urban area a further 120 acres (49 ha). The remainder was low-lying marshy ground known as Bugmore (plan, p. xxxix).

Three factors in particular exerted a strong and obvious influence on the siting and layout of the new town: the presence of existing settlements, routes and river-crossings; the need for an ample water supply; and the need for an ecclesiastical precinct giving both space and privacy. The importance attached to the second and third requirements was in large measure a reaction to the conditions experienced at Old Sarum.

Settlement after 1220.

The decision to provide the town with a supply of water running in shallow channels down the centres of most of its streets must have been taken at an early stage and was clearly an essential and integral part of the town plan. It was, moreover, probably the most important single consideration in the actual siting of the town. It required a large, nearly flat area close to, but above water-level and for the most part above the level of regular flooding. Within the whole extent of the bishop's manors of Salisbury only one such area, that within the bend of the Avon, E. of its confluence with the Nadder, met that requirement. Here, in addition, the leat or stream supplying the bishop's mill (on the site of the present Town Mill, just N. of Fisherton Bridge) constituted a ready source of water at the correct height above river level to feed the system of street-channels.

The plan of the town (Plate 17) indicates that some attempt was made at a regular layout, but a truly rectangular grid-iron pattern characteristic of many new towns of the period was not possible. To begin with the plan had to take account of certain pre-existing features, in particular routeways. A major road linking Winchester and Wilton descended Milford Hill and proceeded W. to a crossing of the Avon, presumably a ford on or near the site of Upper Fisherton Bridge; the alignment of Milford (formerly Winchester) Street probably follows it closely. A road from N. to S. passed by way of Old Sarum towards a crossing of the Avon near Ayleswade Bridge; Castle Street and High Street mark its approximate line and the continuation of the latter southwards through the Close may have had some influence on the position of the cathedral, the W. front of which abuts it. In the N.E. angle of the intersection of these two routes the large market place of the new town was laid out, and almost at the crossing the first parish church within the town, St. Thomas's, was built.

There were also pre-existing settlements (see p. xxx) within the subdivision of the bishop's manor of Salisbury which coincided with the parish of St. Martin. In addition to Milford, or rather that part of Milford which lay W. of the R. Bourne, there was a settlement in the vicinity of St. Martin's church, and smaller settlements may have existed near the bishop's mill and, less likely, near the river-crossing to East Harnham. The settlement at St. Martin's was probably the most important of these and it appears to have been concentrated along the way or street which leads S.E. towards the church, now known as St. Martin's Church Street. The presence of this street may well have caused St. Ann's Street, which meets its N.W. end, to deviate from an original planned line parallel to New Street, thus giving rise to a peculiar pattern of chequers in this part of the town. It is noticeable that the W. part of St. Ann's Street is parallel to New Street (Ivy Street) and that a continuation of this alignment would have led straight to St. Martin's church.

It was the system of channels, designed to provide water for both household and industrial use, which had the most marked influence on the street plan. Since the channels ran along the centres of the streets it was essential that the latter should be carefully aligned to respect the contours and to ensure a gentle gradient for the water all the way from the mill-stream on the N.W. to the meadows at Bugmore. Water entered the system from the mill-stream by means of two inlets controlled by sluices, one (a) W. of Castle Gate, the other (b) further S., to the W. of Scot's Lane (map, p. xxxv). Water at the level of the mill-stream could be made to flow in surface channels to a point (c) a short distance E. of Endless Street on the N., and as far as the S. side of St. Edmund's churchyard (d) on the N.E. From this crucial latter point the water was taken S. at the foot of the rising ground along the line marked by St. Edmund's Church Street and Gigant Street. That this constituted its absolute eastward limit is indicated by the fact that the alignment of these streets tends to follow the contour rather than a straight line. (It is noticeable that the next street up the slope to E., where no water channel had to be accommodated, is markedly straight.) In all, four streets on the E. side of the town run parallel, or very nearly so, to this most easterly water channel. The interval between them is, understandably, the approximate length of two burgage plots, and they are the most obvious manifestation in the town plan of an attempt at a regular layout. To accommodate the most westerly of these streets it was necessary to impinge on the N.E. corner of the Close. Their divergence from the old line of Castle Street and High Street to the W., however, left an irregular area between and prevented a true grid plan overall. A truly rectangular pattern of streets was achieved only in the most northerly chequers. Further S. the rectangularity is broken by Winchester Street, the direction of which was probably determined by the slope of the ground and the resultant necessary alignment of the water channel along it.

A notable exception to the general pattern of water channels is that which ran S. from point 'c' through Gores chequer, presumably once continued through Three Swans chequer, and reappeared in Cross Keys chequer. It followed no street and was conceivably a later addition to the system. No excavated section of any early water channel in a street has been illustrated or adequately described; the only record is of late date and well after the channels were reconstructed in the 18th century (see p. xlviii).

There were also two much deeper water courses, the Town Ditch (also called New Canal) and the Close Ditch. These took water from the R. Avon below the bishop's mill and therefore flowed at a considerably lower level than the street channels. The Town Ditch was carefully positioned to collect water which passed under the easternmost arch of Upper Fisherton Bridge. This it carried southwards for a short distance, to maintain the flow, before turning sharply to the east. The Town Ditch defined the S. side of the Market Place, at its fullest extent, and acted as a main drain in that area. Its existence accounts for the notably oblique alignment of the N. side of New Street chequer. Beyond the Market Place, in Milford Street, the Town Ditch turned S. through Trinity chequer and Marsh chequer, where for the whole of its length it served as a property boundary. South of St. Ann's Street it turned E. to flow past the Friary precinct and thence to the Avon once more; it also joined the ditches draining Bugmore. Because of its depth, bridges were necessary to carry the streets over it. It has been suggested (fn. 20) that the Town Ditch was built later than the main water system, but this seems most unlikely and the deed of 1345, quoted in support, scarcely constitutes evidence for this (see monument (77)).

The Close, the precinct of the bishop and clergy, was also part of the original town plan and, as such, affected its layout. Bounded on the W. and S. by the R. Avon it occupied much of the low-lying S. part of the site and stood physically separate from the town and largely independent of it. It was bounded by the Close Ditch, a deep wet ditch which took its water from the Avon at Lower Fisherton (Crane) Bridge in a manner similar to that of the Town Ditch further upstream. The Close Ditch provided drainage for the houses of those canons whose tenements backed on to it and it also helped to drain the Close as a whole, much of it wet and subject to flooding. During the first century of its existence it probably also provided the precinct with a measure of defence or protection, until it was supplemented by the building of the close wall in the second quarter of the 14th century.

It is significant that New Street, undoubtedly one of the earliest streets of the new town and first recorded in 1265, was laid out parallel with the N. side of the Close and approximately the length of a burgage plot from it. The name Novus Vicus was originally used of the whole street-line, now bearing six names, which extends from Lower Fisherton Bridge on the W. to the town boundary at the top of Payne's Hill on the east. The line of the present Exeter Street and its continuation to Ayleswade Bridge was also conditioned by the presence of the Close.

Mention should be made of Endless Street which, as its name may imply, once continued N. beyond the city boundary, perhaps with the original intention of meeting the main road S. from Old Sarum; Naish's map (Plate 16) shows a length of lane just to the N. of Endless Street and directly in line with it. This line was severed, presumably, by the construction of the city defences in the 14th or early 15th century. It has been suggested that this street line, which continues S. to skirt the Close and so leads to Ayleswade Bridge, was originally intended to be the main thoroughfare through the city, but that it never succeeded in usurping the old route represented by Castle Street. (fn. 21) It may be significant that the whole way from Endless Street to Ayleswade Bridge was referred to as altus vicus in the early 14th century (but see under).

Street-names etc. (fn. 22) Many of the present street-names are of mediaeval origin and some of them were in use within a few decades of the foundation of the city. Over the centuries names have changed, sometimes more than once, and some of the earlier names no longer survive. Such changes appear to have been gradual rather than sudden and they are in consequence not precisely datable. It is not unusual to find two names for a street in use at the same time. The general tendency, however, has been for street-names to become more specific and therefore more numerous. Most early names were originally used of longer lengths of street than they are today; the case of New Street which today bears six separate street-names has already been mentioned. Some examples of different types of name illustrate the various processes at work. (Dates in brackets are those of the earliest known mention of the name.)

In 14th-century deeds the term altus vicus appears in combination with certain street-names, and in most instances it refers to streets which served as thoroughfares through the city. It conveyed the sense 'the king's highway' as used of streets in 17th-century deeds rather than any modern connotation of 'high street'. It was used, for example, of the whole way, some seven-eighths of a mile, from Endless Street to Ayleswade Bridge, and in the early 15th century it was also used of the way from Castle Gate to the Close Gate; but by this period 'le Heystrete' (1420) (fn. 23) referred to the modern High Street.

A few streets acquired directional names, notably the original Winchester Street (1316), (fn. 24) now Milford Street and New Canal; this was the only street to acquire the name of a distant place in the mediaeval period. Other directional names relate to nearer places; in the 13th century Minster Street (1265) (fn. 25) was used of the way leading towards the cathedral,'from Castle Gate to the Close Gate in High Street, and in a deed of 1348 (fn. 26) it was used in the description of a tenement which lay some distance N. of Castle Gate. Castle Street (1339), (fn. 27) the way leading towards the castle of Old Sarum, was not commonly used until the 15th century;in a deed of 1342 Castle Street and Minster Street are used of the same frontage. (fn. 28) St. Ann's Street (1716), (fn. 29) which acquired its present name from St. Ann's Gate at its W. end, was, together with St. Martin's Church Street, originally known as 'the way leading to St. Martin's Church' (1302). (fn. 30)

The names of several streets described trades and activities carried on in them. Wynman Street (1316), (fn. 31) now Winchester Street, is self-explanatory. Catherine Street, a corruption of Carterestret, 'the street of the carters' (1323), (fn. 32) originally began in the Market Place and reached some distance S. of St. Ann's Gate. The name Gigant Street (1320) (fn. 33) or Gigor Street (1485) is perhaps derived from gigour, a fiddler; it was used of the whole length from Bedwin Street to St. Ann's Street. Culver Street (1328) (fn. 34) may suggest the presence of dove-cotes along the E. margin of the town; it extended from the present Winchester Street to St. Ann's Street. Further N. this line, now Greencroft Street, was known as Melemonger Street (1361), (fn. 35) 'the street of meal sellers'. Chipper Lane, formerly Chipper Street or 'the street of the market men' (1323). (fn. 36) once continued as far E. as St. Edmund's Church Street.

Streets also acquired personal names: Scot's Lane which once continued E. to St. Edmund's churchyard appears to have been named from John Scot (1269), (fn. 37) whose house stood at its W. end. Rolleston Street (1328) (fn. 38) is alleged to take its name through Rolveston (1455) from one Rolfe, and its S. extension, Brown Street (c. 1275), (fn. 39) may well be a personal name. Street-corners and the tenements occupying them also acquired personal names in the mediaeval period. Nuggescorner (1365) (fn. 40) in the angle between Endless Street and Blue Boar Row took its name from Hugh Nugge whose house stood there in 1269. (fn. 41) Florentyn Corner in the angle between High Street 'and New Street was occupied by the family of that name in 1297; in 1455 it was known as Old Florentyne Corner (see monument (92)). Drakehallestret (1339), (fn. 42) or Dragall Street, an earlier name for Exeter Street, was apparently named after Drake's Hall, no doubt an important building in the street.

The three bridges giving access to the mediaeval city have all changed their names. Ayleswade Bridge, so called in 1255, (fn. 43) was generally known as Harnham Bridge by the later 15th century, but with the building of a modern bridge downstream the older name is returning to use. Fisherton Bridge (1561) (fn. 44) and Crane Bridge (1540) (fn. 45) were originally known as the upper and lower bridges of Fisherton.

The roughly square blocks into which the mediaeval part of the city is divided by its intersecting streets have been known as 'chequers' since 1603 if not earlier. Most of them, especially those near the centre, were named after their most prominent building, often an inn. (fn. 46) The 18th-century names are shown on Naish's map (Plate 16).

Defences. In general the construction of mediaeval town defences, especially walls, was a burdensome, piecemeal and protracted process except in those places, usually the royal boroughs, where the king took a direct interest. Sufficient money was rarely allocated for the purpose and many of the seigneurial boroughs, of which Salisbury was one, received no walls. An additional disincentive was the fact that the slightest barrier was enough to protect a town's rights in its tolls.

For all its great prosperity Salisbury had only earthwork defences. A bank and ditch, the former perhaps surmounted by a palisade, were built along the N. and E. sides of the city; on the remaining sides the R. Avon and the marsh at Bugmore were evidently considered an adequate protection. Work on the defences had probably begun before the end of the 13th century, but it appears to have been pursued only intermittently and despite successive attempts by the mayor and commonalty it seems not to have been completed until shortly after 1440. Bars or barriers, probably constructed mainly of wood, controlled the entrances to the city, which included the three bridges over the R. Avon; only in Wynman (now Winchester) Street and Castle Street were stone gateways built.

From the late 15th century onwards the defences were neglected and allowed to fall into disrepair. By 1716 those on the N. side of the city had been levelled and by the later 19th century only a few fragments were left along the E. side.

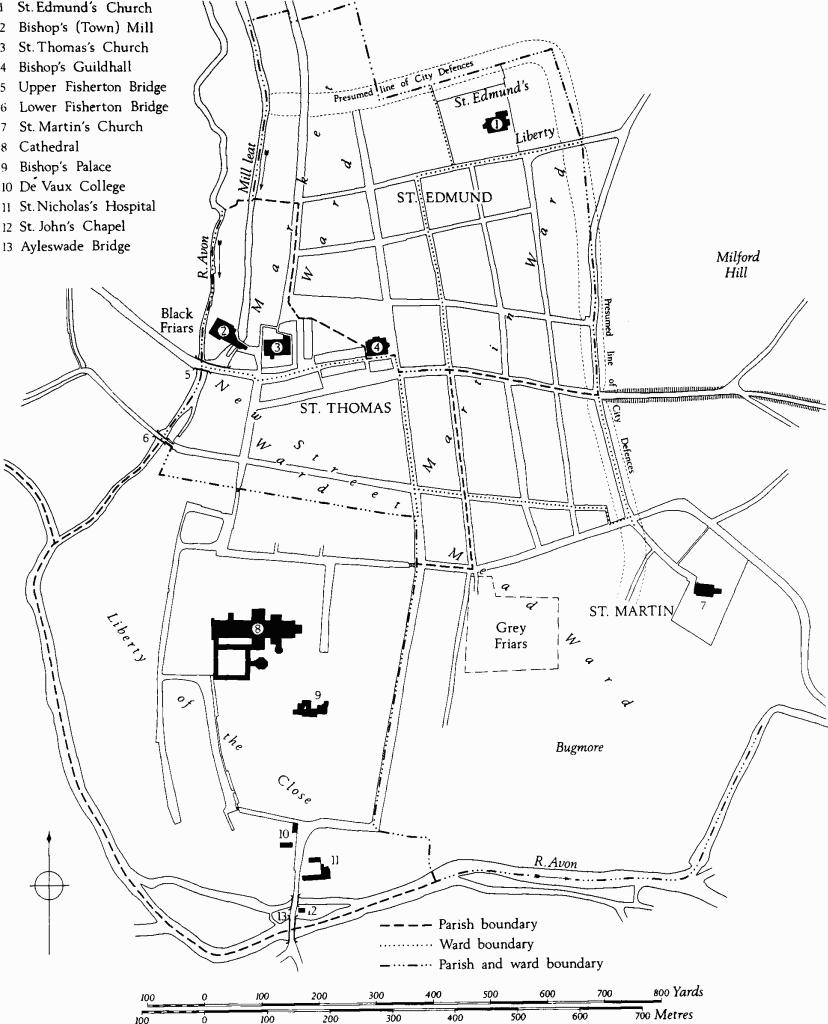

Parishes and Wards. Before the end of the 13th century the city had been divided into four wards and three parishes (map, p. xxxix): rapid growth made such administrative divisions desirable. Two aldermen, implying the existence of wards, are mentioned as early as 1249 (fn. 47) and the four wards appear by name in a list of citizens who signed an agreement with Bishop Simon of Ghent in 1306. (fn. 48) The names of the four wards, Novus Vicus, Forum, Pratum and Sanctus Martinus — New Street, Market, Mead and St. Martin's — sound as if the wards belong to an early phase of the city's development; in particular it is noticeable that St. Thomas's does not appear.

Parish arrangements during the first fifty years are far from clear. St. Martin's, the original parish church of the area, appears to have had no parochial status within the new town, the boundary of which seems to have been drawn deliberately to exclude it. A chapel of St. Thomas had been built by 1238, and the parish of St. Thomas is mentioned in 1246. (fn. 49) Already in 1245 Bishop Bingham appears to have given St. Nicholas's Hospital (26), founded by him in 1231, parochial rights over much of the southern and eastern parts of the town. (fn. 50) All this changed in 1269 when the collegiate church of St. Edmund was established, presumably to meet the needs of a growing population. So rapidly were the chequers becoming occupied, it seems, that a large enough site to accommodate the new foundation could be provided only in the N.E. corner of the town. St. Edmund's churchyard is as large as a whole chequer, much larger than St. Thomas's. The church was served by a college of priests whose house adjoined the churchyard on the east. St. Edmund's was also to be responsible for the church and parish of St. Martin. The first provost of this grandiose foundation was one of the cathedral canons, Nicholas de St. Quintin, one of the earliest founders of a private chantry in the cathedral, a chantry endowed with property in the town ((86), (91)). The foundation-deed of St. Edmund's (fn. 51) sets out in detail the exact boundaries between the three parishes of St. Edmund, St. Thomas and St. Martin, the last now being given parochial status within the city boundary although the church and parish were to be cared for by the new college. At the same time St. Nicholas's reverted to its original function as a hospital, entrusted also with the care and maintenance of Ayleswade Bridge (17) and the chapel of St. John (11), built on the island between the two arms of the river. Opposite the hospital, in a meadow by the river, lies De Vaux College (327– 8), founded in 1261 by Bishop Giles de Bridport. This was an academic institution, designed to cater for the needs of students and scholars associated with the cathedral. (fn. 52)

Parishes and Wards

The parish arrangements, the colleges, St. Nicholas's, the bridge, and St. John's chapel, were all episcopal enterprises. However, the growing city attracted two other ecclesiastical foundations, the Friaries, dependent here as elsewhere upon powerful lay patronage. The Franciscans arrived in Salisbury in the very first years of its existence and by 1228 were provided with a house and precinct lying south of St. Ann's Street (see (304)). Royal patronage provided them, both then and later, with timber for building from Clarendon Forest. (fn. 53) In 1281 the Dominicans also acquired a site on the edge of the new town, just W. of the R. Avon, near the upper bridge. Their removal from Wilton, where they had arrived in 1245, is a pointer to the relative growth and decline of the rival towns.

D.J.B.

DEVELOPMENT OF THE MEDIEAEVAL CITY

Among the provincial towns of England, Salisbury ranked sixth in 1377 and in 1523–7, and as high as third in the 15th century. (fn. 54) It is fortunate that, for the early 15th century, both architectural and documentary evidence survives in sufficient quantity to provide a detailed picture of the city at the height of its prosperity, based on the wool trade.

The centre of the town was the Market Place which stretched originally from Blue Boar Row to New Canal and from St. Thomas's Church to Queen Street (Plate 1 and map, p. 60). Around the Guildhall, against the churchyard of St. Thomas's and in much of the area between, were rows of shops and houses, replacing earlier stalls. In contrast to the very large tenements in the surrounding chequers, many of which contained several buildings, courtyards, gardens and even orchards, tenements in the encroachments upon the Market Place consisted only of the few square yards occupied by the actual buildings. Both the 'rows' and the chequer frontages overlooking the market tended to acquire street-names descriptive of the goods sold thereabouts. However, the various trades were by no means rigidly segregated; not all of them were represented among the street-names and many names which were representative have been altered in succeeding centuries.

One market frontage which never had a trade name was the N. side of New Street chequer. Here were some of the largest houses in the town, belonging to wealthy citizens, many of them wool merchants or grocers, for example Henry Russel and John Hall. The tenements were described in the documents as standing 'in Winchestrestret on the Ditch', a description which also applied to houses on both sides of Milford Street as far E. as the point where the Town Ditch turned S. into Trinity chequer. Tenements on the N. side of the Market Place were said to be 'opposite the market where corn is sold', whether they were in Blue Boar Row or Cheesemarket. On the E. side the tenements were 'opposite the market where wool and yarn are sold'; somewhere nearby there stood a stone cross referred to as the 'yarn market' and also the king's weighbeam for weighing sacks of wool. (fn. 55) Most of the houses and shops in Guildhall chequer, built up against the Guildhall and round the courtyard there (Plate 12), were occupied by wool merchants, drapers and mercers. (fn. 56)

Permanent buildings began to replace the stalls in the rows by about 1300. Some had been built in the Fysschamels, later Fish Row, by 1314. (fn. 57) The butchers' stalls may have lasted somewhat longer, although a tenement worth 5s. existed in le Bocherie by 1328. (fn. 58) The name Butcher Row, first used in 1380, (fn. 59) applied only to the S. side of the present street; the N. side was la potrewe in 1350, (fn. 60) Bothelrewe or Pot Row in 1385. (fn. 61) In 1405 three shops in Pot Row were still said to be opposite the butchers' stalls, (fn. 62) a phrase used since 1350 at latest. (fn. 63) The house at the W. end of Pot Row, Otemele Corner, was bequeathed to the mayor and commonalty by Christina Baron between 1418 and 1461; (fn. 64) later the name was transferred to Oatmeal Row, the N.–S. row in the E. side of Minster Street. Here too there were buildings by 1314; (fn. 65) in 1329 they were said to be 'where the wheelrights live,' (fn. 66) in 1365 simply le Whelernrow. (fn. 67) The two corner houses at the S. end of this row had both cellars and solars in 1351 and were called, after the families who owned them, Hamptonscorner and Powelscorner. (fn. 68) Walter Hampton, baker, already occupied one of them in 1314. Ironmonger Row is mentioned in 1366, (fn. 69) but the name occurs only rarely; it seems to refer to a few shops in the eastern side of Mitre chequer, opposite Ironmongercorner. This last was the S.W. corner shop at the W. end of Butcher Row; it was inhabited by Thomas Blecher, ironmonger, in 1405 and by John Swift, ironmonger, in 1416. The neighbouring house in the N.W. corner was inhabited by butchers in 1405 (fn. 70) and in 1416. (fn. 71)

Regulations have survived from the mid 15th century describing the arrangements made for traders who brought fresh food from outside the town to sell in Salisbury market. (fn. 72) Fishermen and butchers were ordered to have their standings along the Town Ditch, behind and separate from the shops of the Salisbury men in Fish Row and Butcher Row. Milk, cheese, fruit and vegetables were sold in Cheesemarket around the Milk Cross or Cheese Cross, (fn. 73) in c. 1440 said to be newly built (35). Poultry was sold around the Poultry Cross, rebuilt in the 15th century; its predecessor, extant by 1307, (fn. 74) was called la Fayrecroys in 1351. (fn. 75) At that period fruit and vegetables were sold there (fn. 76) and the poultry market was in Silver Street, (fn. 77) called la polatrie in 1405 (fn. 78) and still known as Poultry Street in 1629. (fn. 79) Many shopkeepers in this street followed other trades; against St. Thomas's churchyard was Cordwainer Row and on the S. at least two of the larger tenements in Mitre chequer belonged to goldsmiths. (fn. 80)

Away from the Market Place fewer street-names were descriptive of the many and varied trades of the inhabitants, but clearly, for practical reasons, certain trades tended to congregate in certain areas. On both sides of the High Street, leading to the Close, there were inns and taverns, especially on the W. where the long plots provided space for stabling and the river supplied water for the horses (map, p. 67). In Bridge Street, then called 'the street leading towards the church of the friars preachers' or 'leading to the upper bridge of Fisherton', were tenements belonging to fishermen and dyers who no doubt made good use of the river (fn. 81) Dyers also lived on the W. side of Cheesemarket and Castle Street, with room for workshops on the large plots backing on the river and with a plentiful supply of water. In 1512 Nicholas Martin, merchant, had a tenement called the 'Digh House' beside Fisherton Bridge, and in 1523 William Webbe had another near Water Lane. (fn. 82) Water Lane, a 'lost' street name, lay opposite Scot's Lane (fn. 83) and led to the river-bank and the sluice which controlled the southern inlet of water to the street-channels; (fn. 84) traces of this old right of way remain (see monument (427) and map, p. 149). In 1398 the lane was used for taking horses to the river. (fn. 85)

Away from the river the streets accomodated a great variety of trades. Many weavers, tailors and tuckers, none very wealthy, appear in the Ward Lists of 1399–1400. The involvement of so many citizens in the manufacture of cloth and clothing is striking, and in the case of the tuckers was no doubt made possible by the city's plentiful water supply. A great number of deeds refer to gardens and other empty plots used as rack-closes for drying cloth, particularly in outlying chequers. (fn. 86) Many tanners, parchment-makers and glovers appear in the Ward Lists, most of them living in the S.E. part of the town. In the 16th century 'the way leading to St. Martin's Church, (St. Ann's Street) came to be called Tanner Street, but the name probably came by corruption from St. Ann's chapel over the Close gate at the W. end of the street. (fn. 87) The tanners living thereabouts were the last (and one of the dirtiest) industrial users of the water-supply in the Town Ditch. (fn. 88) Certain metal industries were located in this part of the town, carried on by smiths, braziers, bell-founders and a few cutlers. Archaeological and documentary evidence relates to a bronze-foundry and bell-foundry pit which may have belonged to John Barber, brazier (d. 1403), who lived on the corner of Milford Street and Guilder Lane (see monument (169) and map, p. 94). The pots supposedly sold in Pot Row would have included pots made by braziers as well as clay pots. Brewing and baking seem to have taken place all over the town, not particularly in any one area; there are numerous references in deeds to bakehouses. (fn. 89) In 1407 John Hampton, brewer, acquired the S.E. corner tenement in Griffin chequer, known as Juescornere from a previous owner, Ralph Juys. (fn. 90)

Two members of the legal profession occupied large houses near the S. end of Brown Street. In 1431 William Alessaundre, one of the five legal officers for the city, was living in the house called The Barracks (258), or its predecessor. Windover House (302) was probably built by Edmund Enefeld, clerk, who in 1399–1400 was the richest inhabitant of Mead Ward; his name appears frequently in late 14th-century deeds as a witness to property transactions, or as an executor. In 1455 the most important official in Salisbury, the Bishop's bailiff, John Whittokesmeade, was living as a tenant of the mayor and commonalty in Balle's Place, a 14th-century house with a dignified great hall (351).

The planning of houses was conditioned by the size and position of the tenements they occupied. Some no doubt had been small from the outset, but many tenements were of standard burgage-plot size or larger. Although the relative lack of congestion in the town meant that many tenements remained large and undivided, some in favourable positions were sub-divided at an early date, and others were amalgamated and then sub-divided later, making irregular-shaped plots, such as that of Pynnok's Inn (77). The grid pattern of streets with the tenements arranged in chequers resulted in there being very few of the back lanes which are so characteristic a feature of other mediaeval towns, providing access to the rear of the tenements when the street frontage is fully occupied by buildings. In Salisbury such access had to be contrived in other ways, most commonly by an arched gateway in the main frontage. In the 19th century these gateways were still a noted feature of Salisbury's streets. (fn. 91) Alternatively a back gateway might be provided by annexing an adjoining tenement which fronted on a minor street, either on the opposite side of the chequer or round the corner. Both the 'George' and the 'Leg' inns in High Street had back entries through tenements in New Street, creating L-shaped properties, typical of many. Back-to-back pairs of tenements resulted in very long plots with houses built up along a succession of courtyards and passages; in several chequers these little alleys acquired the name 'abbey' (e.g., monument (131)); an alley in Antelope chequer appears on Naish's map, as does another in New Street chequer. The latter (beside monument (184)) provided access to gardens and orchards surrounded by high walls of flint, chalk and rubble at the centre of this very large chequer. The lane in question is mentioned in 14th-century deeds, (fn. 62) but it was obliterated at the S. end in the 18th century when the tenements there were made into an extensive garden for 'The Hall' (199).

In Cross Keys chequer (plan, p. 81) a sufficient number of mediaeval buildings and boundaries survive to illustrate the diversity in size and shape of the tenements. The W. and S. frontages were more favoured than those to N. and E., with the result that houses and shops were crowded into the S.W. angle while in Brown Street there were only minor tenements, back entries and outbuildings. An unusual feature of this chequer was the small watercourse which bounded the N.E. quarter (map, p. xxxv). Towards the N.W. corner four standard burgage plots are recognisable, overlooking the market and extending back as far as the watercourse. All were large courtyard houses with gateways leading in from the street. St. Mary's Abbey (131) had annexed to it an adjoining tenement in Brown Street, thus creating an alley across the centre of the chequer. The next tenement on the S. (129–30) was divided in 1306, making two long, narrow plots. Monuments (126–8), small shops and houses, were crowded into the W. frontage of Cheesecorner (on the S.W. angle), a favourable position for wool-merchants and mercers, opposite the Guildhall and wool market. The tenements facing S. to Milford Street were larger, particularly in the centre of the frontage. Near the S.E. angle there were two tenements containing eleven shops; they included the site of (136), all the ground behind it, on the corner and as far N. as the watercourse. The angle tenement must have been contained within the 'L' plan of the inner tenement, and there were two gateways in Brown Street. (fn. 93) At the N.E. angle of the chequer there was a similar arrangement, with a squarish corner plot (135) enclosed by a large L-shaped plot now partly occupied by monument (134).

Five large tenements occupied the entire S. frontage of Black Horse chequer (plan, p. 89). All three central tenements were L-shaped, with back entries in Pennyfarthing Street, a small tenement on the site of Grove Place serving Nos. (152) and (153), properties of the Harding family c. 1400.

A different arrangement was contrived at the N.E. angle of Trinity chequer, making use of that major amenity, the Town Ditch. Glastyngburiecorner was a large irregular tenement which stretched into the interior of the chequer, as far as the ditch and southwards along it. The street frontages to either side of this important house were occupied by smaller tenements, those in Milford Street also having access to the ditch (see monument (234)). There was a similar layout in the N.E. part of Marsh chequer (see monument (270)).

Perhaps the largest tenement of which we have any record is the High Street property, 9 perches and 10 feet long, given to the dean and chapter in 1265 (fn. 94) by Nicholas de St. Quintin when he made provision for a chantry in the cathedral (see note preceding monuments (86)–(92) on p. 70). Nicholas was a canon of the cathedral and in 1269 became the first provost of St. Edmund's College. He owned all the land on the E. side of the High Street between New Street and the Close Gate, but he excluded from his gift the small angle tenement (92) and another tenement in New Street. His gateway in New Street lay between them, with the solar of one house built above it. It is not clear where the main house stood in 1265, nor whether the High Street frontage was fully built up, but certainly by the later Middle Ages there was a row of narrow, gabled shops (88–91) and a larger house (86), all facing High Street. The shops had only the smallest of back yards whereas to the house there belonged a great garden, still '10 perches of ground' in 1649. (fn. 95) This property, held by a canon of the cathedral, invites comparison by virtue of its size and position with some of the extensive sites allotted to the clergy within the Close.

At the other extreme were tenements on the fringes of the urban area which were never fully developed. They might contain cottages, or probably were used merely as gardens or as rack-closes for laying out cloth to dry after dyeing or fulling. There were many such tenements in Friary Lane, both on the E. side, S. of the Friary precinct, and on the W. side where some came to be annexed to tenements in Exeter Street. (fn. 96) Others lay in the northern chequers. In 1362 John Richeman gave a group of four tenements in Rolleston Street, on the W. side of Parsons chequer, to the College of St. Edmund to augment the endowment of the Woodford chantry. The property consisted of four cottages, each with a curtilage and the racks built there. Also included in the gift was a curtilage without any buildings at the N.W. angle of the chequer. In the town centre, by the 1360s, a corner site such as this would have contained a shop or a jettied house.

The drastic conversion of many town houses into modern shops has destroyed their original plans at ground level, but much can be inferred from roofs and upper floors. In some cases it has been possible to supplement the fragmentary architectural evidence with information from documents which, in the absence of excavation, is the only indication to be had of the existence of outbuildings. Of all the hundreds of workshops, barns, stables, warehouses and other minor buildings which existed in mediaeval Salisbury, none that is datable so early has survived. The tithe barn, presumably mediaeval, which stood on the N. side of St. Martin's Church emphasised the original status of that church within the whole of the large episcopal holding, but it was demolished towards the end of the 19th century. (fn. 97) Three parish churches remain, but the two friary churches have disappeared together with their conventual buildings; also the College house of St. Edmund. Only fragments, both large and small, of the more substantial inns and houses exist today.

The grandest buildings were built of stone, but most buildings were of timber framework, often with carved bargeboards to decorate the tall gables, a noted feature even in the 19th century. (fn. 98) Roofs were covered with tile after the city council forbade the use of thatch in 1431. (fn. 99)

The late 13th-century Bishop's Guildhall had a simple trussed-rafter roof; it is seen in a drawing made while demolition was in progress (Plate 8). Several unusual roof structures survive from the 14th century, including crown-post roofs with stout bracing springing from near the base of the post (e.g. monument (173)), and there is one example of a tall crown-post with coupled rafters (102). Three different types of scissor brace used in conjunction with tie-beams over relatively narrow spans are notable (monuments (82), (132), (219)). Heavy cross-bracing is a repeated feature in 14th-century buildings; it is used not only in roof trusses but also in gables and in wall framing. The customary infilling seems to have been chalk rubble; no doubt this was easier to use in large triangular panels than it would have been between close vertical studding. The latter, together with wattle-and-daub infilling, appears in later mediaeval houses (e.g. monument (80)). Chalk infilling was found in situ when the cross-braced gable roof of No. 47 New Canal (177), the heavily braced wall of the Plume of Feathers (132) and the main hall roof truss of No. 9 Queen Street (129) were investigated; since then it has all gone. The truss of No. 9 Queen Street has the shape of a large cusped arch spanning a hall 21 ft. wide. A similar profile appeared in the wider hammerbeam roof of Balle's Place (351), where vertical boarding was applied to fill the spandrels of the truss above the main braces. The form of the hammerbeams in this roof imply that the hall had stone walls about 2 ft. thick, but a similar truss without a crown-post was used a generation later in the timber-framed hall at the Plume of Feathers (132). Hammerbeam roofs of similar date, but without 'aisle' plates and with decorative cross-bracing above the collar, were used over the hall and upper chamber of Windover House (302). The N.E. chamber of the George Inn (173) contains an early example of a false hammerbeam roof, a type which has structural similarities with the arch-braced collar roof. With two or three purlins and with tiered pairs of cusped wind-braces both roof-types were used, sometimes in combination, for the fashionable hall roofs of the 15th century.

Many Salisbury merchants lived in courtyard houses, each with an open hall and numerous ancillary buildings. The halls measured, on average, about 23 ft. by 35 ft., which can be compared with the grander scale of the canons' houses in the Close (the Dean's hall was 32 ft. 50 ft.). In the 14th century the halls were heated by open hearths and the roof-timbers became heavily encrusted with soot. Evidence of smoke louvres is found at the Bolehall (140) and at Windover House (302). The latter also contains an example of the new stone fireplaces which became fashionable in the 15th century, usually set into a side wall of the hall. Storeyed hall ranges were then a possibility; an early example was The Barracks (258), built fronting the street with the chimney-stack in the front wall and a screens-passage alongside, an unusual arrangement, more common in Devonshire.

In Salisbury it was common for a merchant's house to fill the main street frontage of the tenement. The house was built on the normal mediaeval plan of a hall with one or two gabled crosswings. The hall was well lit by windows on the street, and the courtyard behind was reached by a through-way in the main range, in the normal screens-passage position. In one case (177) a screenspassage and a through-way wide enough for carts were provided side-by-side, occupying the whole ground floor of the cross-wing. At Church House (97) the through-way has a handsome arched gateway. Here the hall was entered by a doorway (now gone) from the courtyard, and there was no screens-passage.

An alternative plan was to site the main house parallel with the street, but in the interior of the tenement, between the courtyard and the garden. The street front was then occupied by shops or by a minor range of buildings which might be sublet to tenants. A passage or through-way in the front range led to the courtyard, and a screens-passage in the house led through to the garden or back yard. At Windover House (302) the front range may originally have contained shops, but it was rebuilt by William Windover early in the 17th century. At Balle's Place (351) the mediaeval layout of the main house and the street range could both be deduced from the surviving structures and from documents (plan, p. 136). Deeds for a sub-tenement on the corner of the chequer state that it occupied the square of ground between the threshold of the S. entry, leading to the main house, and the kitchen of the main house in Rolleston Street. (fn. 100) Evidently the S. entry was the small W. bay in the street range, where a narrow through-passage still existed until demolition; the kitchen would probably have been detached from the main range, but in line with it. Further N. along the street was a gateway wide enough for carts, and in the garden was a dovecot. (fn. 101) (A dovecot was often one of the appurtenances of a Salisbury messuage, as at Shoves Corner (p. 120) which had a large garden in the centre of Marsh chequer.) A layout such as that of Balle's Place provided most of the usual advantages of a free-standing house.

A third layout for courtyard houses was to place the hall within the tenement, but at right-angles to the street and alongside the courtyard. John Hall's hall (185) is the best surviving example, but the type was common as it was easily adapted to tenements of various sizes. The frontage could be filled with one or more shops and a gateway to the courtyard, which could be left open at the inner end. This type of plan was often paired, two houses sharing an entry and courtyard. Detailed evidence of such an arrangement is contained in the 'Survey of Radborde's land', dated 1584. (fn. 102) As by that date the houses in question were very much decayed it is probable that they were of mediaeval origin. They occupied a tenement with a frontage of 43½ ft. to Blue Boar Row, where they stood on either side of a long narrow courtyard. Each house had a shop with a chamber over it, fronting the street, an open-roofed hall overlooking the yard, a kitchen with a well, butteries, stables, lofts and outbuildings. The eastern house of the pair had, next to the hall, a parlour with an open-roofed chamber over it. At the N. end of the yard, with a small garden beyond, was an openroofed great hall (22 ft. by 37 ft.) used by the tanners of Salisbury for their guildhall. The relationship of this important building to the others named in the survey can only be conjectural. The mention of wells is typical; many houses in the town had a shallow well excavated in the valley gravel, either in the kitchen or in the courtyard. The well water was better for drinking than the general supply in the street channels.

Occasionally a house with a hall was built with a gable-end towards the street, filling a narrow tenement; the hall was then entered through the shop or room in the front. Side windows in the hall were vulnerable to blocking by any new building on adjoining plots and it is not surprising that the one well-preserved example of this type is relatively early in date (129).

Smaller houses were built either one bay deep and roofed parallel with the street, or two or more bays deep and set gable-end to the street. The subsidiary shops at Balle's Place, dating from the 14th and 15th centuries (only the latter survive), were of the former type. Another group (203), at the S.E. corner of Antelope chequer, comprises an L-shaped range with a crown-post roof; in 1415 it contained three shops in Ivy Street and one in Catherine Street. In Guilder Lane a terrace of seven jettied cottages (158) was built on ground which had been empty from 1425 to 1443.

Gabled houses were also built in short rows. A mid 14th-century row of three shops in High Street (82), two bays deep, has three parallel scissor-braced roofs, each three bays long, with steep gables toward the street; a narrow side-passage at the S. end of the building led from the street to a small yard at the back. In Silver Street another group of three gabled houses (63), three storeys high, was built in 1471. Pynnok's Inn (77) was rebuilt in 1491 as four houses, each with two upper floors. Further S., on the corner of Crane Street, a three-storeyed pair of houses (81), also of late 15th-century date, occupies a plot only 22½ ft. by 24 ft.; at one time it was a subsidiary tenement of the Rose Inn.

Single-gabled houses were no doubt common on small sites, especially in the 'rows' and near the town centre, where many were rebuilt in the 16th and 17th centuries. When carried up to three storeys and double-jettied they were substantial buildings; monuments (44), (52), (71) and (92) provide examples. Taller houses gave greater scope for display. No. 58 High Street (84) had a double-jettied gabled front decorated with cusped bracing. Extra space was sometimes provided by making the lowest storey a cellar or half-cellar and by raising the ground floor above it, as in the Wheatsheaf Inn (71), No. 25 High Street (171) and the George Inn (173). Most documentary references to cellars occur in deeds for tenements on cramped sites; when they occur in deeds for large tenements such as monument (132) it can usually be shown that the word is used to refer to storage accomodation above ground. A complete small house, two storeys high and two bays deep, is the 15th-century corner house (57) which was given to Trinity Hospital in 1458 by John Wynchestre, 'barbour'. Other corner houses of similar size are probably not complete houses, but remnants of larger ones; examples are monuments (305) and (341), properties of the Baudrey and Nugge families in the 14th century.

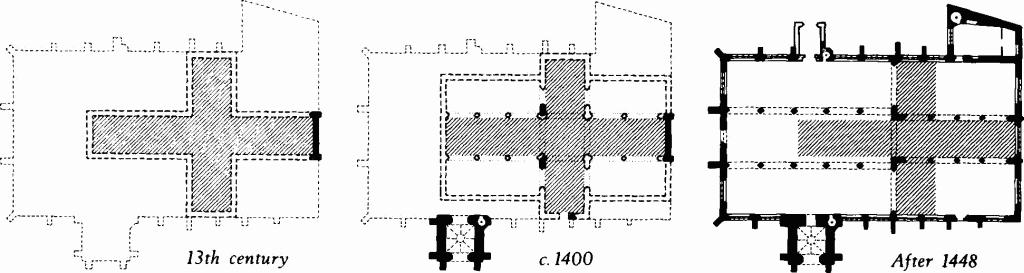

By the late 15th century some prosperous merchants were choosing to live, not in a great courtyard house, but in a compact gabled house two bays wide and two or three bays deep, with windows back and front and with a narrow passage leading from the street to the back yard. Four surviving examples, built on small sites in favourable commercial positions, date from the middle or late years of the 15th century: No. 3 Minster Street (55), No. 56 High Street (83), No. 8 Queen Street (128) and No. 13 High Street (174). The internal arrangements of the first named are clearly described in a detailed 'schedule of implements' accompanying a lease of 1611. The ground floor contained the shop and a half-cellar with a low room over it. The hall occupied one whole bay of the first floor and extended from front to back of the house, with doors leading to a chamber at the front and to a kitchen at the back, the latter overlooking St. Thomas's churchyard. The upper floors contained chambers and attics. Houses of this type required a substantial chimney-stack of brick or stone. In plan and profile they were the forerunners of Georgian double-pile town-houses.