Ancient and Historical Monuments in the City of Salisbury. Originally published by Her Majesty's Stationery Office, London, 1977.

This free content was digitised by double rekeying. All rights reserved.

'Major Secular Buildings', in Ancient and Historical Monuments in the City of Salisbury(London, 1977), British History Online https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/rchme/salisbury/pp46-59 [accessed 27 April 2025].

'Major Secular Buildings', in Ancient and Historical Monuments in the City of Salisbury(London, 1977), British History Online, accessed April 27, 2025, https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/rchme/salisbury/pp46-59.

"Major Secular Buildings". Ancient and Historical Monuments in the City of Salisbury. (London, 1977), British History Online. Web. 27 April 2025. https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/rchme/salisbury/pp46-59.

In this section

Major Secular Buildings

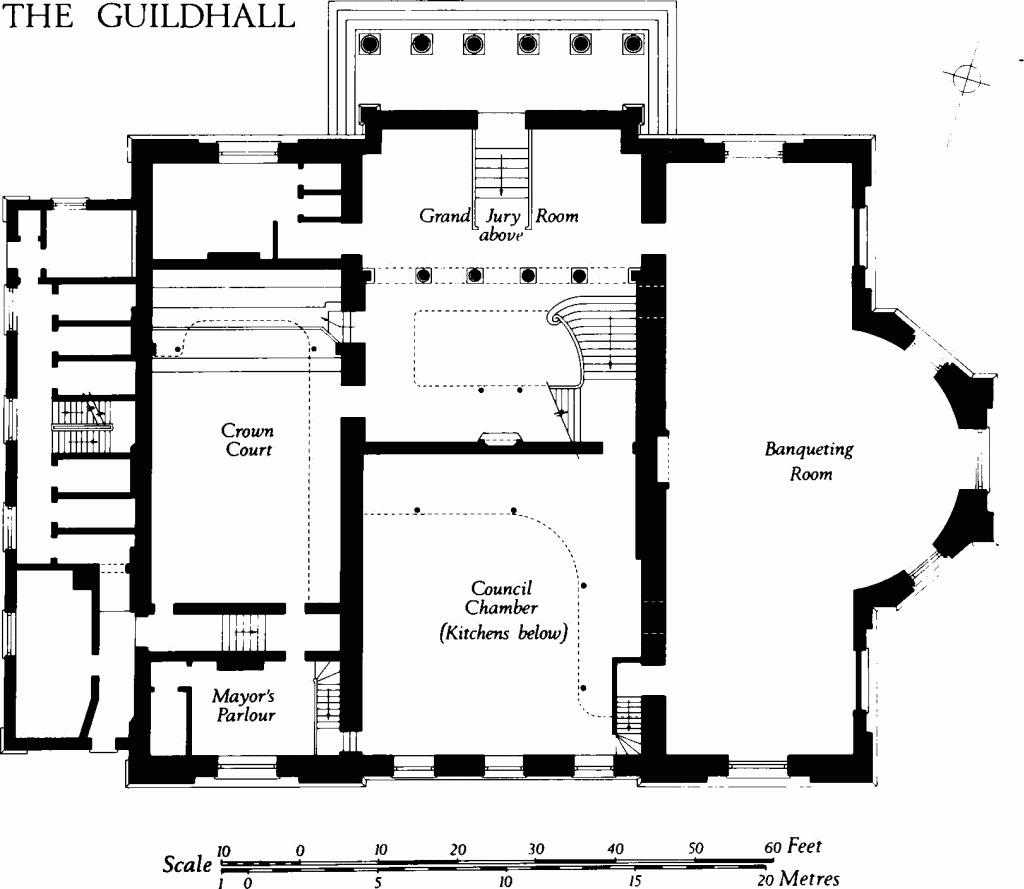

(13) The Guildhall, at the S.E. corner of the Market Place, is mainly of two storeys with cellars and has brick walls with stone dressings, and slate-covered roofs. It was erected in 1788–94 on the site of the former Bishop's Guildhall, demolished to make room for it. The demolished building was probably of early 14th-century origin. (fn. 1) A drawing in Salisbury Museum (Plate 8) depicts the mediaeval hall in the course of demolition; a plan by Buckler (Plate 12) is in Devizes Museum. The drawing shows the scars of the roofs of a row of low buildings which formerly adjoined the hall on the S.; no doubt they formed the N. side of a courtyard which lay S. of the hall, as shown on Naish's map (Plate 16).

The present building, containing a council chamber, a banqueting room, mayor's parlour etc. and a court of justice, was designed by Sir Robert Taylor and erected with some changes by his pupil, William Pilkington. (fn. 2) The foundation-stone was laid on 14 Oct., 1788. (fn. 3) A view by E. Dayes, engraved by Frederick Jukes (1795), shows the building with a recessed portico on the N. and a projecting portico on the west. (fn. 4) In 1829 the building was enlarged by Thomas Hopper, the N. portico being rebuilt in projecting form with a room above it for the grand jury. (fn. 5) In 1889 the W. portico was demolished and a wing containing rooms associated with the lawcourts was built in its place. Internally, the building was extensively refitted in 1896–7.

In the N. front (Plate 18), the two main lateral bays, with large round-headed windows with vermiculated archivolts and quoins, are of 1794. The Roman-Doric portico of 1829 probably incorporates four columns and part of the entablature of the original N. portico; above are the three round-headed windows of the grand jury room. The central stone panel, with dedicatory inscription of 1794, appears to have been in the parapet of the original portico. The E. elevation retains its original form, with a large projecting bay with three round-headed windows. In the S. elevation the two main lateral bays of the N. front are repeated, but with simpler details; the central bay, altered in 1829 and later, has round-headed windows in the lower storey and three square-headed windows above, the latter lighting the council chamber.

Inside, the entrance hall contains a reset chimneypiece of c. 1580; it was brought from the former Council House, burnt down in 1780 (fn. 6) and demolished in 1800, which stood some 40 yds. N. of the Bishop's Guildhall. The jambs of the chimneypiece have coarse Ionic pilasters; the frieze has strapwork panels and centrally the arms of the city, barry of eight, or and azure, supported by double-headed eagles ducally gorged.

The banqueting room has plaster enrichments and joinery of 1794. Joins in the dado and skirting of the W. wall show the original position of the doorways, before the enlargement of the entrance hall in 1829 allowed the present more spacious arrangement. The fireplace surround is of grey marble with the city arms on a white marble panel; above is a replica of Winterhalter's portrait of Queen Victoria in coronation robes, and over this a trophy with the royal arms as borne from 1707–1714. According to Britton, (fn. 7) the Corporation's portrait of Queen Anne by Dahl formerly hung in this position. (fn. 8)

The grand jury room has a marble fireplace surround of 1829. A carved oak chair in the mayor's parlour (Plate 21) bears the date 1585, initials TB. HH, and RBM for Robert Bower, mayor, 1584; a similar chair has the date 1622, WM. II, and MGM for Maurice Green, mayor in 1621. Another chair, richly carved in mahogany (Plate 21), has the initials I T M for Joseph Tanner, mayor, and the date 1795.

The inventory of civic plate compiled in 1895 by L. Jewitt and W. St. John Hope, (fn. 9) remains unchanged in respect of pieces earlier than 1850. The great mace of 1749 is illustrated on Plate 21. A collection of bronze standard weights and measures, engraved 'New Sarum, 1825' with the city arms and supporters, is now in Salisbury Museum (Plate 21).

The Guildhall

St. Edmund's College

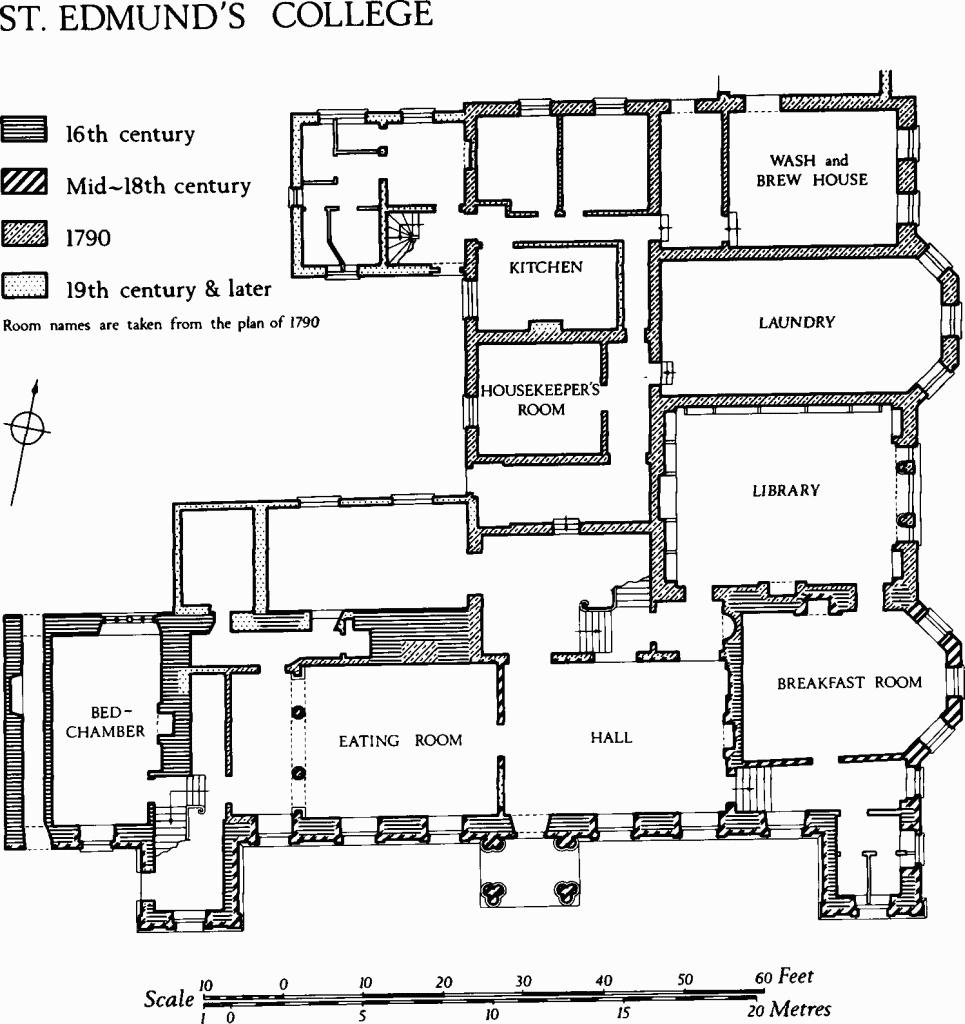

(14) St. Edmund's College, now The Council House, is of two storeys with a cellar and in part with a mezzanine floor; it has rubble and brick-faced walls with stone dressings, and slate-covered roofs. The present building presumably takes the place of the College of St. Edmund which was founded in 1269; (fn. 10) stonework in the cellar below the W. part of the S. range may be mediaeval. In 1546 the college was surrendered to the Crown and sold first to William St. Barbe, three years later to John Beckingham, and in 1575 to Giles Estcourt. The S. range, which appears to be of late 16th-century origin, retains plasterwork in which the Estcourt arms occur. In 1660 the college was bought by Wadham Wyndham of Norrington, whose heirs retained possession until 1871. (fn. 11) Known as The College throughout this period, it was the largest and handsomest private house in the town. In 1873 it became a school and additions were made on the north. In 1927 it was acquired by the City and converted to local government offices and committee rooms.

A drawing dated 1670 in the possession of the City Council (fn. 12) shows the S. front of the 16th-century building as approximately symmetrical and of seven bays, with projecting bays at the centre and at each end of the facade and with an eighth bay on the W., beyond the western projection. The same features are shown on a drawing dated 1690 in Salisbury Museum (Plate 3). The centre bay contained a porch and had a gabled roof; the lateral projecting bays had flat roofs with ball finials at the corners. A stable range stood on the W. of the court in front of the house. The original windows of the S. front were square headed and of three to five lights, many of them with transoms. Above the first-floor windows there were six gables containing attic windows; similar gables occurred on the E. elevation.

About the middle of the 18th century the S. front, perhaps originally of rubble and ashlar, was cased in brickwork with ashlar dressings in a style showing the influence of James Gibbs. The attic storey was removed and new roofs of shallow pitch were masked by brick parapets with ball finials above a moulded stone cornice (Plate 18). In the projecting end bays, mezzanine windows with elliptical heads replaced the former ground and first-floor openings. A single-storeyed stone porch with Roman-Doric details and clustered columns replaced the former two-storeyed porch bay. In the main plane of the S. front the fenestration was completely changed and the place of four bays of transomed casements was taken by six tall sashed openings with rusticated classical surrounds. In the E. elevation a two-storeyed bay window was added at the end of the original range.

In 1790, (fn. 13) under the ownership of Henry Penruddock Wyndham, the N. wing was added, containing the staircase, library, kitchens and service rooms on the ground floor, and bedrooms in mezzanine and upper storeys. The architect was S.P. Cockerell; plans for the projected works, signed S.P.C., 1788, are preserved (Plate 3). (fn. 14) Although adapted to new uses the rooms still remain much as originally planned. The large Venetian window of the library and the adjacent bay window, which together with the mid 18th-century bay window to S. make the E. front into a symmetrical composition, are not shown in the plans of 1778, but probably were added to the design before construction took place. Buckler's watercolour of 1811 (fn. 15) shows the building almost as it is today.

The westernmost bay of the S. range, beyond the W. projection of the S. front, has rendered walls and the windows are asymmetrically disposed. A panel in the W. elevation, with a two-centred head simulating a blocked mediaeval window, appears in Buckler's drawing of St. Edmund's church, 1805 (fn. 16) and dates probably from c. 1790. The rendered N. front of the W. bay retains, in the lower storey, a late 16th-century stone window of four transomed square-headed lights with ogee-moulded and hollow-chamfered surrounds; doubtless the windows seen in the drawings of 1670 and 1690 had similar details. The N. wall of the S. range also retains a 16th-century stone string-course with a strong cyma recta profile.

Inside, the main staircase has cast-iron balustrades and mahogany handrails of 1790; the staircase window has a stained glass panel with the arms of Wyndham. The oak stair in the W. projecting wing of the S. front, with fluted column-shaped newel posts and turned balusters (Plate 89), dates from earlier in the 18th century; on the plans of 1788 it is shown as already in existence. The W. ground-floor room of the S. range (bed-chamber) has a late 16th-century ceiling with interlacing moulded plaster ribs and small panels of foliate enrichment. The 16th-century N. window noted above lights this room, and the embrasure of a similar window, now partly blocked, occurs further E. in the same wall; the remains of a third window are seen in the plan of 1788. A large 16th-century chimneybreast, attested by the thickness of the walls, but hidden by 18th-century and later plasterwork, is shown on the plans of 1788. On the first floor, a room near the W. end of the S. range has a late 16th-century ceiling with interlacing moulded ribs with foliate enrichment and a moulded wall-cornice with a frieze in which shields-of-arms of Estcourt alternate with arabesques. Elsewhere, the principal rooms have decoration of c. 1790 with neo-classical plasterwork of good quality. Francis Bernasconi was employed at the house in 1804, but his bills (fn. 17) relate to exterior work and cannot be used as evidence that he was engaged on the interior.

A 15th-century stone Porch in the garden 150 yds. E. of the house (Plate 59) was removed from Salisbury cathedral during Wyatt's restorations and rebuilt here in 1791; it formerly sheltered a doorway at the N. end of the N. transept (fn. 18) and was known as St. Thomas's Porch. (fn. 19) The plain E. buttresses evidently take the place of the cathedral wall. The octagonal spire and pinnacles seen in John Buckler's perspective views of the rebuilt porch (fn. 20) were added in 1791; engravings show that the porch at the cathedral was flat-roofed. Inside, the two-centred arches have spandrels heavily enriched with 15th-century leaf carving and are outlined by casement mouldings with spaced flower bosses. The shallow elliptical vault with false ribs is of 1791.

Porch from Salisbury Cathedral

rebuilt at St. Edmund's College in 1791.

In the garden is part of a stone Urn, probably of the 17th century, with guilloche decoration; the neck and foot are missing. In 1774 it was set on a pedestal inscribed to record the discovery near that place of bones and rusty armour, (fn. 21) supposed to be evidence of Cynric's victory over the British, A.D. 552. (fn. 22)

Part of the City Rampart survives in the garden (see Monument (16)).

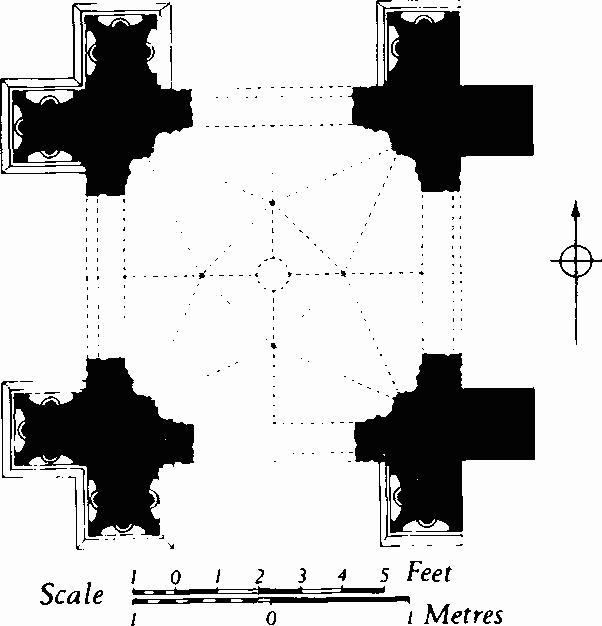

(15) The Poultry Cross (Plate 57), of Chilmark ashlar with a lead-covered timber roof, stands at the corner of Minster Street and Butcher Row. The hexagonal arcade has piers with weathered and pinnacled buttresses supporting ogee-moulded and hollow-chamfered segmental-pointed arches with ogee labels; above is a moulded string-course and a pierced parapet with a canopied niche at the middle of each side. The monument thus far described is datable by style to the end of the 15th century; it cannot be the cross mentioned in the reign of Richard II. (fn. 23) The upper part, with flying buttresses surrounding a central pinnnacle with six ogee-headed niches and a cross finial, was designed by Owen Carter following a proposal published in 1834 by Peter Hall; (fn. 24) the work was executed by W. Osmond in 1852– 4; (fn. 25) the masonry of the lower part of the monument was restored at the same time. Pictures of the Poultry Cross as it was before 1852 include two drawings in Salisbury Museum, (fn. 26) Buckler's view of 1810 (Plate 2), a drawing by A.W. Pugin, (fn. 27) and an oil painting of c. 1850. (fn. 28) Other views are in Salisbury Museum. (fn. 29)

Inside, the hexagonal central shaft and the re-entrant angles of the buttresses retain traces of former vaulting. Each vault rib sprang from a carved corbel; those which survive represent angels holding shields. There are traces of heraldic colouring, barry of eight, or and azure.

(16) City Defences. The royal charter of 1227 granted the bishop the right to enclose the city with adequate ditches (fossatis competentibus). The expression presumably means 'defences' since a ditch with an accompanying bank or wall, or a combination of both, would have been normal, and without it would scarcely constitute an effective defence. (fn. 30) Although work may have begun in the 13th century it was certainly unfinished in 1306–7. (fn. 31) A deed of 1331 concerning a tenement at the N. of Endless Street speaks of novum fossatum, presumably a newly built part of the town defence, on its N. side. (fn. 32) In 1367 Bishop Wyvil gave the citizens permission to fortify the town with four gates and a stone wall with turrets and also 'to dig in his soil on every side to the width of eight perches for a ditch'. (fn. 33) Such an enterprising scheme was altogether too ambitious and it remained unrealised. In 1378 the citizens sought help of the king to complete the ditch around the city and also a wooden fence or palisade, presumably to surmount the rampart. Despite a grant and subsequent levies on property-owners within the city, the work was still unfinished as late as 1440, but it was probably completed soon after that.

On the W. and S. of the city the R. Avon formed a natural defence; on the E., where the ground rises steeply, and on the N., earthwork defences were constructed. From the marsh at Bugmore on the S. a rampart and ditch extended along the E. side of the city to a point N.E. of St. Edmund's Church (5), where it turned and continued westwards to the E. arm of the R. Avon, in reality the leat of the Town Mill. The marshy nature of the ground foiled an attempt to carry it as far W. as the R. Avon proper. Two fragments of the rampart still survive, immediately N.E. and S.E. of the Council House (14). The bank (Plate 17) is about 60 ft. wide at the base and stands up to 18 ft. high; the surrounding land, and especially the ditch, has been much altered by shallow quarrying and by garden landscaping. Along the W. side of Rampart Road, remains of the bank (6 ft. to 8 ft. high) were revealed and demolished during the construction of a road in 1970; evidence of 13th-century occupation was found in a number of places under the bank. An incomplete section of the ditch (at SU 14852982) showed that it had been recut once and suggested that it was 40 ft. across and nearly 20 ft. deep at that point. (fn. 34)

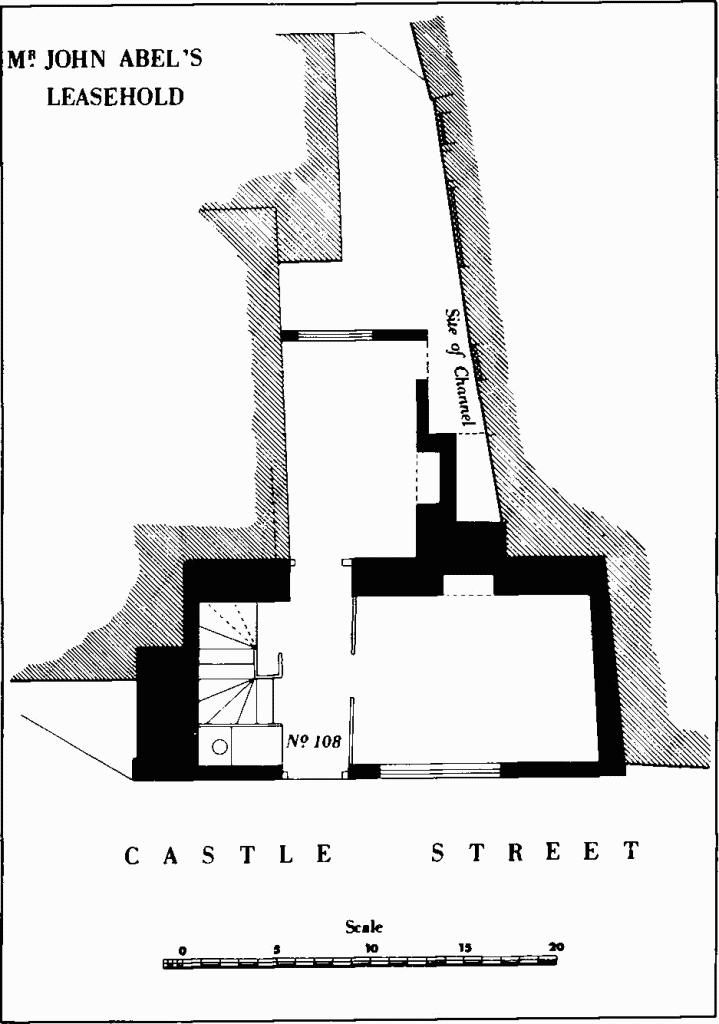

There were eight entrances to the city (Plate 16 and map on p. xxxix) and control over some of them is evident as early as 1269 when there is mention of 'the eastern bars of the city' and of a bar in Castle Street. (fn. 35) Bars or barriers, presumably mainly of wood, served to protect most of the entrances even in the 15th century, and formal gateways appear to have been built only in Wynman Street (modern Winchester Street) and Castle Street. The gateways are shown on Speed's map (Plate 1) as rectangular towers with embattled parapets. Wynman Gate was demolished in 1771, but part of its N. side may have survived until late in the 19th century, appearing as a rubble wall in an old photograph (Plate 15). An 18th-century painting (Plate 9) shows the round-headed archway. The ground was excavated in 1971 for the building of the inner ring-road, but no trace of the former gateway was found. Castle Street Gate was partly demolished in 1788, (fn. 36) but the E. abutment remained until 1906; its thick walls are recognisable in a 19th-century plan preserved in the City Engineer's office. In the upper part of the abutment was a stone panel with the royal arms (Plate 20); presumably it was originally over the archway. Since 1908 the panel has been reset in an adjacent building. It probably dates from 1638, (fn. 37) and it appears to have been taken down during the Commonwealth and re-erected in 1662, (fn. 38)

No. 180 Castle Street

demolished in 1906, including the E. side of Castle Street Gate.

Upkeep of the defences seems to have been neglected from the end of the 15th century, but precise information on the stages of their demolition is lacking. Encroachment on the ditch had started by 1499 and in the following century parts of it on the E. side of the city were regularly leased out. Excavations on the S. side of Milford Street have shown that the ditch was filled with rubbish in the 15th and 16th centuries. (fn. 39) Naish's plan of 1716 (Plate 16) shows defences only on the E. side of the city; those on the N. had presumably been levelled already. By 1880 (O.S.) about 150 yds. of rampart on the E. side of Barnard's Cross Chequer and the present fragments near the Council House were all that survived.

(17) Ayleswade Bridge, (Plate 19) spanning the R. Avon on the S. of the city, was built by Bishop Bingham, c. 1240, (fn. 40) at a point where the river is divided by an eyot into two channels. The wider channel on the S. is spanned by six two-centred arches of Chilmark stone; that on the N. has three arches; the northernmost arch is now blocked. The intrados of each original arch is plain and the end voussoirs have double chamfers. The arches rise from stone piers with up-stream and downstream cutwaters and support a roadway originally some 17 ft. wide. In 1774, to widen the roadway, supplementary arches were built on top of the cutwaters, thus adding 3 ft. to each side of the six S. spans and about 6 ft. to the W. side of the three N. spans. A semicircular pedestrian refuge was built in 1774 on the E. side of the N. part of the bridge; a triangular refuge on the adjacent pier is of the 19th century. Late 18th-century inscriptions record the building of the bridge by Bishop Bingham and its widening in 1774.

(18) Crane Bridge, crossing the R. Avon at the W. end of Crane Street, is of ashlar quarried from the Upper Greensand and has four segmental arches springing from piers with up-stream and down-stream cutwaters. On the N. side (Plate 19) the E. arch has two rings of chamfered voussoirs and may be partly mediaeval. The other arches have wide chamfers and keystones and are probably of the 17th century. In the 16th century a former bridge had six arches. (fn. 41) The S. side of the bridge was rebuilt when the road was widened in 1898, and again in 1970. To the E. of the supposed mediaeval arch, a smaller opening, now blocked, admitted water to the Close Ditch (see p. xxxvi).

(19) Milford Bridge, of squared rubble and ashlar, carries a narrow and apparently ancient road across two distinct channels of the R. Bourne on the E. boundary of the city. The road probably led to Clarendon Palace, (fn. 42) but the present bridge appears to be no older than the late 14th or early 15th century. As the watercourse is divided, the bridge has two pairs of arches separated by a length of causeway (Plate 19). The most westerly arch is semicircular; the others are two-centred. On the S. side the voussoirs of all four arches are mediaeval, with chamfered and hollow-chamfered mouldings. On the N., unmoulded voussoirs indicate rebuilding and lengthening of the vaults for the widening of the road, probably in the 18th century; the semicircular W. arch of the S. side was presumably rebuilt at this time. The piers between both pairs of arches have cutwaters with weathered heads. Road-level is indicated on the N. and S. sides of the bridge by a continuous roll-moulded and hollow-chamfered string-course, evidently mediaeval and no doubt partly reset. The ashlar parapets have 18th-century torus-moulded and weathered coping.

(20) Laverstock Bridge, crossing the R. Bourne on the E. boundary of the city and comprising three spans of cast-iron girders on ashlar piers, was built in 1841 to replace the bridge swept away by floods in that year (Salisbury Journal, 25 Jan, 4). The girders are embossed with the maker's name 'Figes Sarum'.

(21) Dairyhouse, Mutton's and Hatches Bridges, carrying the Southampton road over the R. Bourne and adjacent conduit, S.E. of the city, have been altered in the course of modern roadworks, but retain original features. Dairyhouse Bridge, spanning the main stream, consists of a segmental brick arch between ashlar abutments; the parapets are of wrought-iron with twisted uprights and ball finials. The ashlar coping at road level is inscribed J S 1836. Mutton's Bridge, about 60 yds. to the W., is of ashlar and has two segmental arches. The S. side has been rebuilt in modern times, but the ashlar parapet includes a date-stone of 1732. Hatches Bridge, 250 yds. E. of Dairyhouse Bridge, is of the first half of the 19th century and has two segmental brick arches springing from an ashlar pier with a rounded cutwater. Inside the W. arch are the voussoirs of an ashlar arch, presumably part of an earlier and narrower bridge.

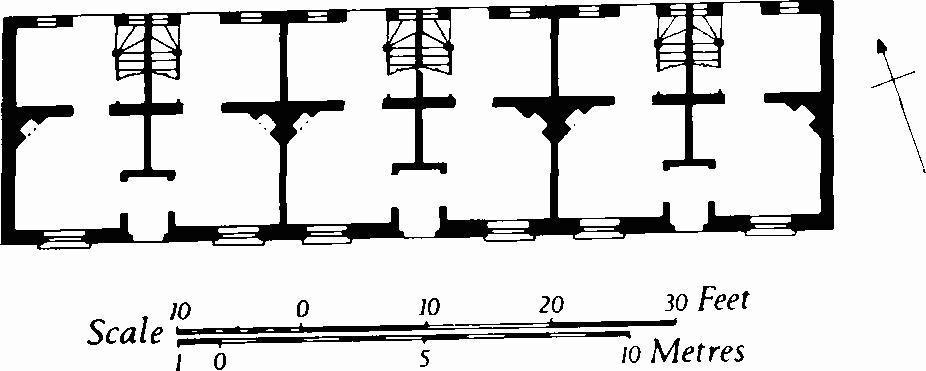

(22) General Infirmary, of five storeys with brick walls and tiled roofs, was designed by 'Mr. Wood of Bath' in 1767 and opened to patients in 1771. (fn. 43) Attribution to the younger John Wood is confirmed by analogies at Standlynch House, Downton, where he was active in 1766. Four plans (reproduced on p. 53) and a N. elevation by T. Atkinson, 1819, show the original form of the building. Although somewhat altered and masked by extensions, the 18th-century structure is still in use (Plate 23). (fn. 44)

Wood designed a tall building with symmetrical elevations capped by crenellated parapets. Turrets projecting on the E. and W. contained privies and nurses' bed closets. The main entrance was originally at first-floor level, the inconvenience of an exterior stair being mitigated to some extent by artificial heightening of the forecourt; an old photograph (Plate 15) shows the arrangement. The principal administrative rooms and the chapel were on the first floor, with the chapel just inside the main entrance. (The entrance has now been transferred to what originally was the basement level, and the forecourt has been lowered.) The three wards were named after the principal benefactors of the hospital, the Duchess of Queensberry and the Earls of Pembroke and Radnor. Queensberry Ward survives nearly in its original form.

The foundation stone was laid in September, 1767 and tenders from contractors were invited early in 1768. Robert Surman was appointed bricklayer and tiler; Robert Schafflin plasterer; Minty & Godwin glaziers, painters and plumbers; carpentry and joinery was undertaken by Mr. Edmund Lush who also was Clerk of the Works; James Kellow of Tisbury was stonemason.

In 1819 the chapel was converted into an accident ward and the former committee room became the chapel. In 1822 part of the old city gaol (see (476)), which stood between the Infirmary and the R. Avon, was converted into a fever ward, but it was dilapidated and inconvenient and in 1845 it was replaced by a new three-storeyed wing named for a Mr. Bartlett who in 1818 had left money for extensions. In 1846 the accident ward was restored to its original use as a chapel and fitted with a columned and pedimented 18th-century reredos from Warminster parish church. The silver-gilt communion vessels have assay marks of 1793, donor's inscriptions of William Batt, 1794, and shields-of-arms of Batt quartering Clarke.

(22) General Infirmary

Early 19th-century plans.

(23) Police Station and Lock-up, near the S. end of Devizes Road, are of two storeys with brick walls and slated roofs; they do not appear on the Reform Act map of 1833, but they are on Botham's plan and probably were built before 1850. The station, now shops, comprised dwellings and offices and has a symmetrical W. front of six bays. The lock-up on the E. has been stripped of floors and partitions and is now a warehouse. The scars of the dismantled brickwork indicate ten vaulted cells in each storey, each cell having a lunette window set high above the floor, with an iron grille in an ashlar frame.

(24) Former County Gaol, 100 yds. S.E. of (23), was of three storeys with cellars and had rendered brick walls and slate-covered roofs. Built between 1818 and 1822, (fn. 45) the administrative building (a) and the chapel (c) were still in existence in 1959, but were demolished soon afterwards. From 1875 to 1901 the administrative building was in private occupation; thereafter it was used as military headquarters.

The former County Gaol

From a drawing of 1854 (City Surveyor's records).

The administrative building had a symmetrical W. front of three bays with a central doorway, round-headed sashed windows in the two lower storeys and square-headed upper windows. The N. and S. elevations were similar but respectively of six and five bays; the E. side was masked by a later building. Inside, the stone stairs had plain iron balustrades. The cellar had brick vaults.

The chapel had long been converted to secular use and in 1959 was much altered from its original form. At the time of demolition it had a basement and two upper storeys; a single-storeyed projection on the E. was probably the former chancel.

(25) The Market House, or Corn Exchange, with walls of ashlar and of brick, with an iron and glass roof, was built in 1858 and thus falls strictly outside the scope of this inventory, but it is included because of its prominence as a public building. A Corn Exchange was mooted in 1854 and at first it was intended to build it on the site of the old Council House, in the E. part of the Market Place, (fn. 46) but in a revised project the site was transferred to the W. side of Castle Street, whence a 'tram road' might connect it with the newly constructed London and South Western Railway. (fn. 47) A plan of the site by Peniston, c. 1855, is in W.R.O. (451/222). The Market House Railway was opened in 1859 with the Corn Exchange as its E. terminal. (fn. 48) The E. front of the Exchange, designed by John Strapp, Chief Engineer of the L.S.W.R., is ashlar-faced. It has three bays defined by rusticated pilasters, and three large round-headed archways; the middle bay has a pediment. In 1975, when much of the building was pulled down, the facade was incorporated with the structure of a new public library.

The site, between Cheesemarket and the R. Avon, was occupied in mediaeval times by a large courtyard house. Early in the 15th century it belonged to a dyer from Longbridge Deverill and was called Deverell's Inn. In 1423 it passed to John Porte (mayor, 1446) and his wife Juliana. (fn. 49) By 1721 the building had become the Maidenhead Inn and it so remained until demolished to make way for the Market House. (fn. 50) The 18th-century E. front of the inn is seen in an old photograph (Plate 14). The remains of a 15th-century hall roof and a stone chimneypiece, discovered during demolition, were saved and re-erected in a school (475) near St. Edmund's church.

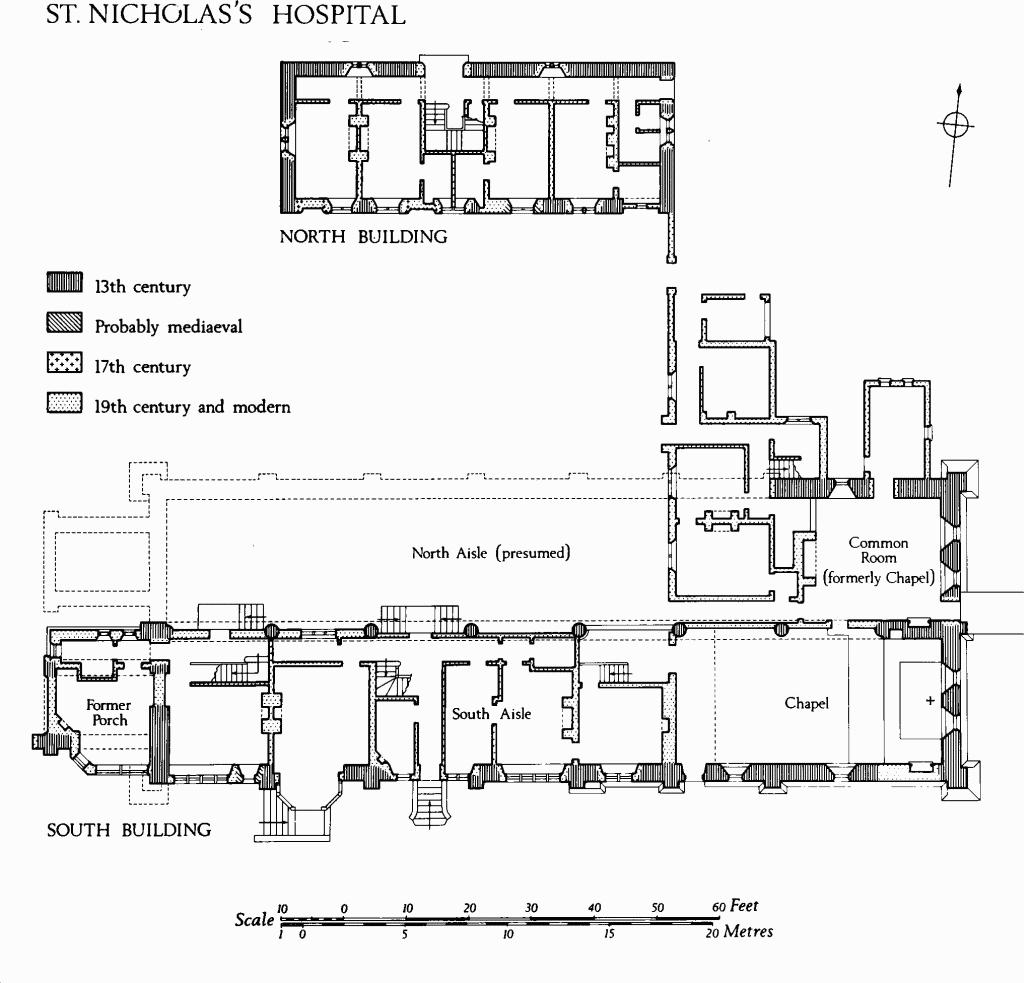

(26) St. Nicholas's Hospital, of one and two storeys, with walls mainly of flint and rubble with ashlar dressings, and with tiled roofs, dates from the second quarter of the 13th century. Although the buildings were extensively restored and altered between 1850 and 1884, (fn. 51) the outlines of the original structure are clearly distinguishable. In the 13th century there were two parallel buildings; to the N. a range 62 ft. long (E.—W.) and 24 ft. wide; to the S. a much larger building, 146 ft. long and 48 ft. wide. The N. building was probably two-storeyed. The S. building was single-storeyed and comprised two aisles parted by a central arcade of seven arches (Plate 58); each aisle had its own pitched roof. A chapel was contained within the E. end of each aisle, and each probably had its own W. porch although that of the S. aisle alone remains. The dual nature of the S. building presumably reflects the obligation of the hospital to care for the sick and poor of both sexes. It was built by Bishop Bingham, probably in 1231 when royal grants were made of timber 'for building the hospital'. (fn. 52) Bishop Bingham's reference to 'the old hospital towards the north' suggests that the smaller N. building may be an earlier hospital of St. Nicholas which occurs in documents of 1227. (fn. 53) When the S. building had come into being the N. building was probably retained as accommodation for the warden and chaplains.

Enough of the hospital survives to afford a particularly interesting example of mediaeval planning: a single building designed for the separate needs, both spiritual and physical, of men and of women.

St. Nicholas's Hospital

Architectural Description — The North Building was restored in 1860 and its masonry repointed, but original stonework is seen in the lower part of the walls. In the S. wall are jambs of four blocked doorways. That on the E., with a chamfered two-centred head springing from square jambs, is probably original; the next doorway corresponds with a modern window, but the threshold and chamfered jambs are partly mediaeval; further W. a blocked doorway with a chamfered elliptical head and continuous jambs is perhaps of the 17th century; a similar blocked doorway occurs near the W. end of the wall. A weathered string-course below the first-floor window sills is of the 19th century, but it may replace a mediaeval feature. Above, at the W. end of the S. elevation, a blocked first-floor window of two trefoil headed lights in 13th-century style, but wholly restored, presumably represents an original opening. The other windows in the S. elevation are modern. The W. wall of the range has a ground-floor window of two pointed lights, perhaps partly original; the upper window is modern. At the E. end of the N. elevation a blocked first-floor window of two pointed lights, fully restored, probably replaces an original opening. In the E. wall the trefoil heads of two 19th-century first-floor windows may echo mediaeval features. Inside, the building has been modernised, but the reveal of a mediaeval S. window is indicated by a niche near the middle of the S. wall.

In the South Building, restored by Crickmay in 1884, the two E. chapels are preserved; that on the N. is used as a common-room by the pensioners of the hospital; the southern remains a chapel. The E. wall has a steeply chamfered plinth and clasping corner buttresses of two stages with moulded plinths and weathered offsets. In the square-set middle buttress the weathered offset is roll-moulded. The E. windows of the chapel have chamfered lancet-headed surrounds, wide splays and hollow-chamfered two-centred rear-arches with moulded labels. Above, the gable has a round window of eight lobes with foliate cusps;this is modern, but a drawing by J. Buckler, 1803, (fn. 54) shows a similar feature. The N. chapel or common-room has a restored N. lancet and two lancets on the E., all similar to those of the S. chapel. The gable has been rebuilt.

The S. wall of the S. range has a plinth as before and pilaster buttresses of one weathered stage. The remaining original windows have lancet heads, chamfered surrounds and hollow-chamfered segmental-pointed rear-arches. In the second bay from the E. is a small original doorway with a chamfered two-centred head, continuous jambs and run-out stops. Buckler's drawing shows a pair of lancet windows near the S.E. corner, but these have gone. The W. part of the S. wall retains elements of four single-stage buttresses and the jamb of another window, but the masonry has been rebuilt and much altered. A small window near the W. end has a chamfered square head and continuous jambs.

The W. gable of the S. aisle has two restored lancets and a loop, as shown on another Buckler drawing (Plate 11). Further W., the W. wall of the former porch contains a blocked archway with a two-centred head and continuous jambs of two orders, chamfered and hollow-chamfered, under a moulded label without stops.

The N. side of the S. aisle is composed of the original seven-bay arcade in which most of the arches have been closed by modern or 19th-century walls. The arches, two-centred and of two chamfered orders with roll-moulded labels, spring from moulded capitals on cylindrical shafts with moulded bases; the latter are now below ground. Inside, the part of the S. aisle which lies W. of the chapel has been converted into the Warden's residence and other rooms. The former W. porch of the S. aisle is likewise used as part of a dwelling. West of the common-room the N. aisle has gone.

Fittings—Aumbry: In S. chapel, in N. wall, with rebated two-centred head and stone shelf, 13th century. Bell: At entrance to S. chapel, by John Wallis, 1623. Benefactor's Table: In S. chapel, on S. wall, marble tablet in stone frame with four-centred head, recording benefactions of Edward Emily, 1795. Piscina: In N. chapel (common-room), in S. wall, with moulded trefoil head, shafted jambs and three-lobed basin (Plate 40), 1231; in S. chapel, replica of foregoing, 19th century. Table: In common-room, of oak (11½ ft. by 2½ ft.), with moulded rails, six turned legs and plain stretchers, 17th century. Tiles: Reset in S. chapel, thirty, with slip decoration including bowman, deer, griffin etc., 14th century; Wall-clock: In common-room, with painted wooden case, by Hugh Hughes, c. 1760.

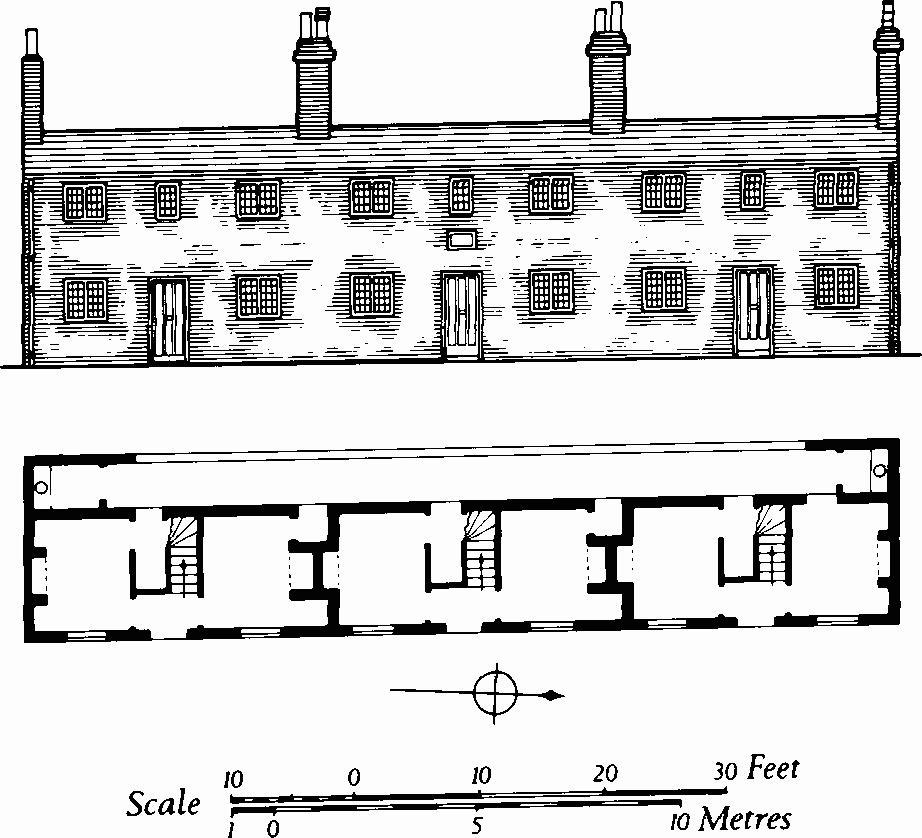

(27) Trinity Hospital, founded in 1379 for twelve inmates, (fn. 55) was entirely rebuilt in 1702. It is of two storeys with attics and has brick walls with stone dressings and tiled roofs. The chapel was refurnished in 1908. Modernisation in 1950 reduced the number accomodated from twelve to ten.

The symmetrical S. front (Plate 22) has a central doorway with a stone architrave and a broken pediment surmounted by a stone panel with a sundial. The doorway opens into an arcaded loggia at the S. end of the central courtyard. At the N. end of the courtyard (Plate 22) a doorway to the chapel, with a bolection-moulded timber surround and acanthus brackets supporting a broken pediment, has above it two reset stones formerly carved and thought to be relics of the original building. (fn. 56) In 1968 the lower stone retained a fragment of a relief suggestive of the decoration seen on some 13th-century coffin slabs, (fn. 57) but this has since perished. Centrally on the roof of the N. range is a square timber bell-cote with a clock and a concave lead roof with an octagonal finial. This bell-cote, a prominent feature in 18th-century drawings (cf. Plate 9 and the view on Naish's plan, Plate 16), seems to perpetuate the memory of a small spire which may have been a feature of the mediaeval building (Plate 1).

(27) Trinity Hospital, 1702.

Inside, the chapel has the height of two storeys. The plain walls have heavy moulded plaster cornices with acanthus brackets; above is an elliptical plaster vault. The windows are round-headed. The hall, of equal height with the chapel, has a draught-lobby with early 19th-century fielded panelling; the fireplace is modern. The adjacent kitchen has a wide fireplace with a cambered and chamfered oak bressummer.

The four staircases have plain oak newel posts and close strings; the balustrades have been boarded in. The committee room on the first floor at the centre of the S. range has a moulded plaster cornice and, above the fireplace, a panel with the arms of Queen Anne, in a bolection moulded frame.

Fittings- Altar: of stone with consecration crosses, mediaeval, discovered and reset in chapel, 1908. Bell: unmarked. Chairs: in hall, six, of oak with turned legs and leather-covered seats, c. 1702. Clock: in bell-cote, probably 1702. Glass: reset in chapel windows, late mediaeval and 17th-century fragments including royal shield-of-arms (1603–89). Plate: in chapel, includes silver cup with engraved strapwork, probably late 16th century; silver stand-paten with Britannia assay marks, 1706; pewter flagon with donor's inscription of William Waterman (mayor 1702) and date 1707. Table: in hall, oak, with six turned legs, c. 1702.

(28) Blechynden's Almshouses, No. 75 Winchester Street, are a 17th-century foundation, but the present group of single-storeyed brick cottages, with tiled roofs, appears to result from total reconstruction in 1857. A stone tablet reset in the S. gable of the E. range bears an inscription of 1683 (not 1663). (fn. 58) Another tablet records the rebuilding in 1857.

(29) Culver Street Almshouses, Nos. 28–32 Culver Street, of two storeys with brick walls and slate-covered roofs, were built in 1842 to replace almshouses said to date from the reign of Elizabeth I. (fn. 59) They were demolished in 1972.

(29) Culver Street Almshouses.

(30) Hayter's Almshouses.

(30) Hayter's Almshouses, near the W. end of Fisherton Street, on the N. side, demolished and rebuilt in 1964, comprised a range of six two-storeyed dwellings with rendered walls and tiled roofs. A segmental-headed plaque was inscribed 'This Asylum built and endow'd for six poor women by Mrs. Sarah Hayter, lady of this manor, 1797'.

(31) Thomas Brown's Almshouses, Nos. 129–135 Castle Street, of two storeys with brick walls and tiled roofs were demolished in 1971. The seven dwellings appeared to be of c. 1800 although the charity was not formally established until 1852 (V.C.H., Wilts. vi, 171).

(31) Thomas Brown's Almshouses.

(32) Taylor's Almshouses, at the N.E. corner of Parsons Chequer, are two-storeyed and have brick walls with ashlar dressings and tiled roofs. Founded in 1695 and first built in 1698, the building was entirely reconstructed in 1886. Stone tablets with inscriptions of 1698 are preserved.

(33) Frowd's Almshouses, at the N.W. corner of Parsons Chequer, are two-storeyed with brick walls and tiled roofs (Plate 23); they were built in 1750 to accommodate 24 pensioners. (fn. 60) The middle bay of the symmetrical N. front has brick quoins and a moulded timber open pediment. The round-headed doorway is set in an oak door-case with rusticated Tuscan pilasters supporting a segmental open pediment within which, on a panel with a rococo carved border, is inscribed 'Built and Endowd by the Liberality of Mr. Edward Frowd, Merch't late of this City, 1750'; above is a Palladian window. Centrally on the roof is an octagonal lantern with a lead cupola. The S. elevation has an arcaded loggia in the lower storey and circular windows lighting a corridor in the upper storey. Inside, the oak stairs have close strings, square newel posts, plain hand rails and Tuscan-column balusters. The vestibule and some lodging rooms retain moulded and coved cornices. The Audit Room at the centre of the upper storey has bolection-moulded oak panelling. In 1974 the building was adapted for use as a hostel and the interior was extensively altered.

(33) Frowd's Almshouses.

Lesser Secular Buildings

ST. MARTIN WARD

The secular monuments of St. Martin Ward are divided for convenience of presentation into groups based mainly on the chequers which the mediaeval streets define. To assist in the identification of monuments, small maps based on O.S. (1880) are inset in the text. The maps are conventionally orientated and are printed at a uniform scale, approximately 1:1,600.