An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in the County of Northamptonshire, Volume 6, Architectural Monuments in North Northamptonshire. Originally published by Her Majesty's Stationery Office, London, 1984.

This free content was digitised by double rekeying. All rights reserved.

'Fotheringhay', in An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in the County of Northamptonshire, Volume 6, Architectural Monuments in North Northamptonshire(London, 1984), British History Online https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/rchme/northants/vol6/pp63-75 [accessed 19 April 2025].

'Fotheringhay', in An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in the County of Northamptonshire, Volume 6, Architectural Monuments in North Northamptonshire(London, 1984), British History Online, accessed April 19, 2025, https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/rchme/northants/vol6/pp63-75.

"Fotheringhay". An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in the County of Northamptonshire, Volume 6, Architectural Monuments in North Northamptonshire. (London, 1984), British History Online. Web. 19 April 2025. https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/rchme/northants/vol6/pp63-75.

In this section

10 FOTHERINGHAY

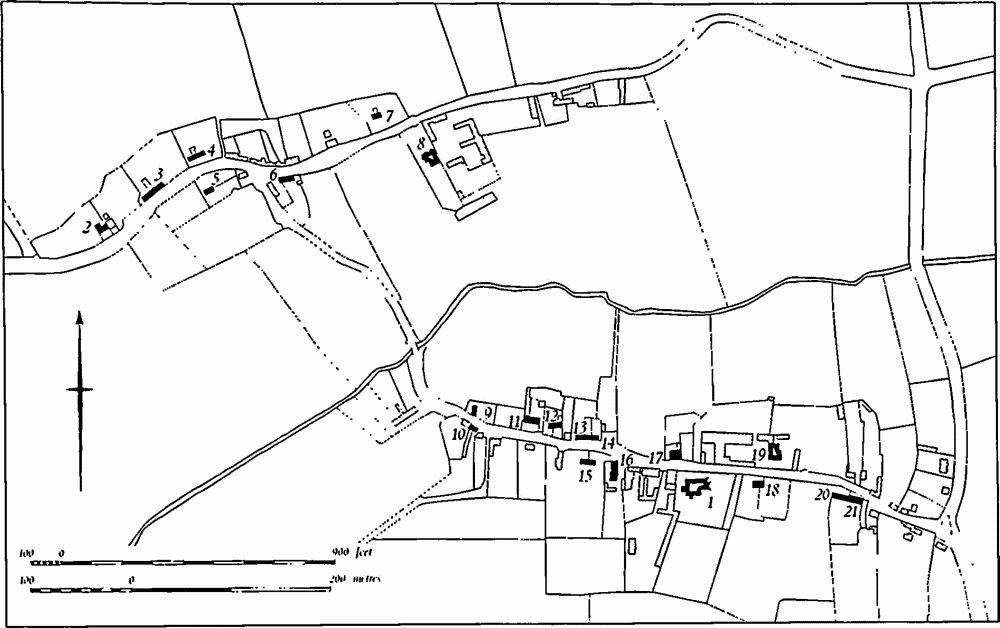

(Fig. 85)

Fotheringhay is a parish of 850 hectares bounded on the E. and S. by the R. Nene and lies in the Forest of Rockingham. From before the Conquest until the 13th century Fotheringhay was part of the lands of the Earls of Huntingdon, one of whom built the castle (RCHM, Northants. I, Fotheringhay (34)). The second Earl in c. 1141 founded a Cluniac Nunnery here, which was moved about four years later to Delapré near Northampton. Subsequently the manor and castle passed through several hands until in 1377 Edward III gave it to his younger son Edmund Langley, first Duke of York. The castle then became an important administrative centre under the Dukes of York until the fourth Duke became king as Edward IV in 1461. Edmund Langley appears to have made extensive additions to the castle to increase the small accommodation recorded in 1340 (Cal. Inq. Misc. (1308–48), 419); these included a large two-storey polygonal lodgings block on the motte, called the Fetterlocks. Edmund and his son Edward also established a college of priests in the castle some time before 1398. In 1411 this college was transferred to the parish church which was rebuilt on a magnificent scale in the following years. This great collegiate building was clearly intended to be the family church and mausoleum (1).

Edward IV continued to use and visit Fotheringhay after becoming king (Cal. Pat. passim); his gift in 1461 of the castle to his mother Cecily, widow of the third Duke, seems to have been of no effect and was rescinded in 1469. Building improvements had begun by 1463 (Kings Works II, 649–50) and in 1464 we hear of the 'garden and spinney which the king has made to enclose the little park' immediately S.E. of the castle, by the river (Cal. Pat. (1461–7), 389; RCHM, Northants. I, Fotheringhay (37)), and by 1476 he had built the New Inn in the village (2) presumably to supplement the accommodation for visitors to the castle.

On the change of dynasty in 1483, Yorkist Fotheringhay gradually lost its importance. Henry VII gave it to his wife, and it was given by Henry VIII to his wives in turn. The castle was kept in repair, and in 1506 there were at least 39 chambers assigned as lodgings to specified members of Lady Margaret's household (St. John's College, Cambridge, MS 91.7). After the execution of Mary Queen of Scots in 1587 the castle was little used; in 1592 the local militia stores were kept there until the castle was alienated to Lord Mountjoy in 1603 (HMC, Buccleuch I, 227, 236). After 1623 it fell into disrepair. The college was dissolved in 1549 and the derelict choir was dismantled in 1573, the proceeds being used to help rebuild the bridge over the Nene (22). The collegiate buildings were converted to form a large house occupied by the lessee of the manor until they were demolished some time after 1657 (PRO, Prob. 11/383). Only the parochial nave now remains.

The village was formerly much larger. Leland remarked that all the houses were of stone (Itinerary I, 4) and the 1524 subsidy suggests a population of over 100 families, about the same size as King's Cliffe. A hollow-way to the N. of mons. (10) and (11) is perhaps associated with this larger settlement. Deprived of its castle and college, the village declined, becoming a purely agricultural settlement. By 1673 the population had fallen to 67 families, and to 57 in 1801. A market and fair were granted in 1308 and renewed in 1457 (Cal. Chart. III, 122; VI, 128) but did not prosper. The area N.W. of the church was called Marketstead, and this together with the position of the church suggest a former open space or green between the church and road. According to Leland, Edward IV recognized the weakness of Fotheringhay's position and intended to rectify it by making the river navigable, but nothing came of his proposal (Itinerary I, 4). The causeway across the floodplain S. of the bridge and in Warmington parish may also be the work of one of the Dukes of York. The village street is continued by a path N. of the castle to cross the Nene at Warmington Mill.

In the late Middle Ages Fotheringhay must have presented the most impressive group of buildings in the area; the dismantling and dispersal of these buildings is a matter of history and folklore. The sale of materials of the dismantled choir in 1573 is documented, as is the dispersal of woodwork and glass to Tansor and King's Cliffe; woodwork at Benefield, Hemington and Warmington can be identified by heraldry (Hemington (1); Warmington (30)). Part of the castle hall is believed to have been reused at Conington Castle (RCHM, Huntingdonshire, Conington (4)) and Robert Kirkham is said to have taken stone from there for his chapel at Fineshade (Bridges II, 308). A late 16th-century doorway in the garden of the former rectory at King's Cliffe (78) is said to have the same origin.

From the 17th century the manor was held by non-residents. In 1806 it was bought by William and Thomas Belsey together with almost all the property in the parish. Thomas, 'who made a fortune as a land-jobber' (NRO, 0.816) and lived at Margate, is credited by Bonney with the major improvements made in the village in the early 19th century (Bonney, Historic Notices, 11). Further building was carried out by Lord Overstone after his purchase of the village in 1842. The parish had been enclosed in 1635, but it was Belsey who reorganized the agricultural holdings, built three outlying farms (19, 20, 21) and 'rebuilt or repaired the greater part of the cottages allotting gardens to each' (Bonney, Historic Notices, 11). He certainly rebuilt three cottages (7, 8, 9) and perhaps another (17). In addition he probably built (16) and a house for his steward (6).

Ecclesiastical

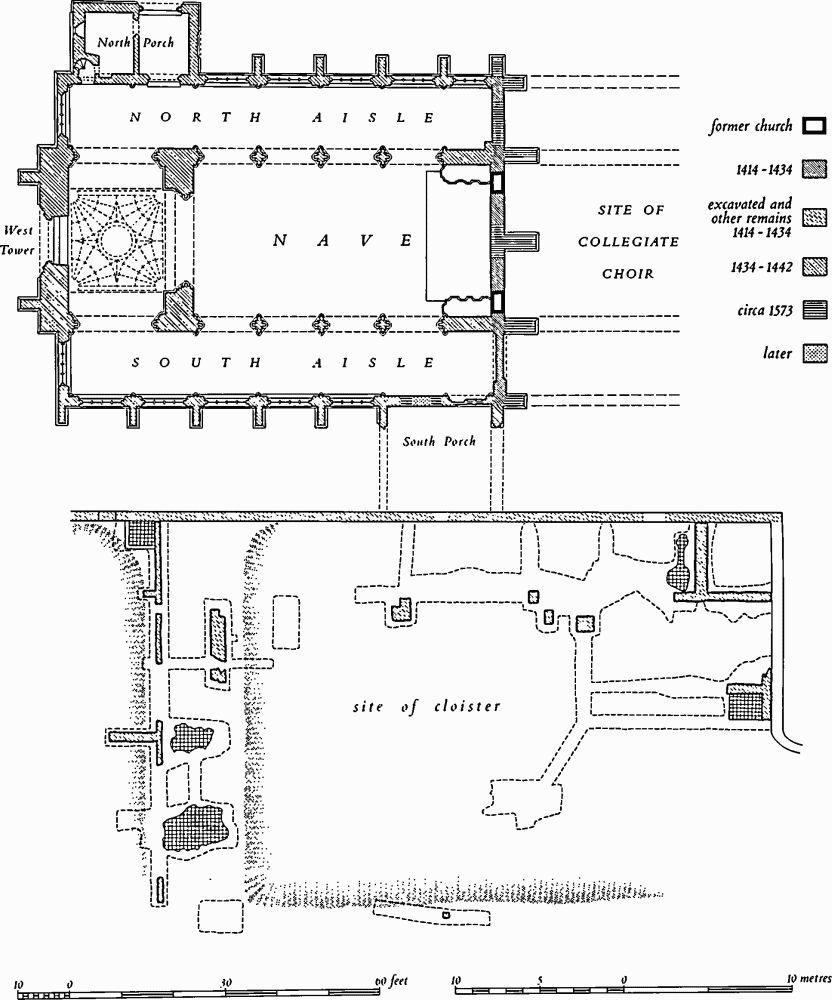

(1) The Parish Church of St. Mary the Virgin and All Saints stands on the S. side of the village overlooking the River Nene (Fig. 86; Plates 46, 48). It consists of an aisled nave and tower and formerly served as the parochial nave of the College of the Annunciation of the Blessed Virgin Mary and All Saints. The very large choir built for the use of the college was demolished in the 16th century. Residential buildings belonging to the college stood S. of the church, but all that survives above ground is part of the N. wall of the complex, modified to serve as the churchyard wall. (A. Hamilton Thompson, 'The Statutes of the College of St. Mary and All Saints, Fotheringhay', Arch. J., LXXV (1918), 241; L.F. Salzman, Building in England down to 1540 (1967), 505–9; R.C. Marks, 'Glazing of Fotheringhay church and college', JBAA, CXXXI (1978), 79–109).

The present church stands on the site of an earlier one, the advowson of which was granted by Simon de St. Liz (d. 1153) to the nunnery of Delapré (VCH, Northants. II, 574). This church was recorded in the early 14th century as having a S. aisle (LAO, Register III, f. 132v.) and part of the E. wall of its nave survives, built into the W. wall of the collegiate choir.

Fig. 86 Fotheringhay Church Plan of standing and excavated remains of the former college of the Annunciation of the Blessed Virgin Mary and All Saints

A college of priests, dedicated to the Annunciation and St. Edward the Confessor, is known to have existed in the Castle before 1398 (Cal. Pap. Let. V, 253, 262). It was probably founded, or perhaps refounded, by Edmund Langley, first Duke of York and his son Edward, and consisted of a Master, twelve chaplains and four clerks. In 1411 Edward petitioned the Pope for licence to increase the college by four clerks and thirteen choristers, to change the dedication to the Annunciation of the Blessed Virgin Mary and All Saints, to make Henry VI the principal founder and for the college to come within the jurisdiction of the Bishop of Lincoln from which it had hitherto been exempt (Cal. Pap. Let. VI, 190). The wish to place the college under the control of the Bishop of Lincoln signifies Edward's intention to move the college to the parish church. The parish church was amalgamated with the college by the acquisition by exchange of the advowson and vicarage from the abbess and convent of Delapré (Cal. Pat. (1413–16), 282). Indulgences were granted in 1413 to those giving alms for the building of the collegiate church (Cal. Pap. Let. VI, 378).

Building work must have started at once. A commission was issued by the king for building workers in February 1414 (Cal. Pat. (1413–16), 180) and work was in progress when Edward wrote his will in August 1415. He died at Agincourt in October of that year. Dugdale (The Book of Monuments, Earl of Winchelsea coll., BL loan MS 38) records an inscribed tablet dated 1415 at the E. end of the S. aisle of the nave, which was probably a foundation stone and may have come from the choir (Marks, op. cit., 80). The progress and character of the work is known from the contract for the nave, which was drawn up in September 1434 between commissioners of Richard, third Duke of York and William Horwood, mason (Salzman); the choir and the cloister were completed by that date, although the library on the N. of the cloister had not been built by 1438 (LRS, 14 (1928), 98). The architectural details of the choir were given as a pattern for the nave but there are several variations between the contract and the building as constructed (see below). The exact date of completion of the nave is unknown; the hospitium, the building of which was to be delayed until the church was finished, was operating by 1441, and this has been taken to indicate that the nave was complete by then (Hamilton Thompson, Arch. J., LXXV (1918), 267). Leland records that the cloister was made in the reign of Edward IV when Field was master of the college (1480–1507); this must refer to a rebuilding of the cloister between 1480 and 1483, the year of Edward IV's death.

The college was dissolved in 1548 (Knowles and Hadcock, 320); the nave remained in the hands of the parish, and the residential buildings were eventually sold to James Cruys in 1558 (BL, Harl. MS 608, 62). A commission was set up in 1572 to enquire into the status of the choir, and despite opposition from parishioners it was demolished (PRO, E178/1654). Money from the sale of materials and fittings was used to modify the wall that formerly divided the nave from the choir (PRO, E101/ 463/23). Letters patent of 1573 authorizing Sir Edmund Brudenell of Deene to do this work also empowered him to move the tombs of Edward Duke of York and Cecily to the parish church; in the event he caused replacement tombs to be put at the E. end of the nave (PRO, E101/ 622/35). The N. claustral range was demolished before 1603, but the remainder of the residential buildings were converted into a substantial house which was demolished shortly after 1662 (Hearth Tax).

The collegiate choir, built between 1414 and 1434 served as a mausoleum for the house of York. Edward, second Duke of York was buried there in accordance with his will, under a floor slab with a brass image (PRO, E178/1654). Richard, third Duke of York, and his son Edmund Earl of Rutland, brother of Edward IV, were killed at the Battle of Wakefield in 1460, and were both reinterred at Fotheringhay in July 1476. Edward IV's mother, Duchess Cecily was buried in the tomb of her husband, Richard, on her death in 1495 (Marks, op. cit., 80–82).

The choir, replacing the chancel of the earlier parish church, stood together with the old nave until 1434 when the present nave was built. The outline of the E. wall of the former nave can be seen within the wall separating the parochial nave from the collegiate choir (Fig. 87). This wall was modified to become an external wall when the choir was demolished in 1573, but retains some features belonging to the choir including its outline in cross section. The length of the choir is unknown but it was doubtless considerable. The contract for the present nave stipulated that the two were to be of the same width and height and that the design was to be generally uniform, although slight differences in detail were introduced. The choir windows had bowtel mouldings whereas the nave windows were to be plain, and the buttresses of the choir were smaller than those of the nave but of the same design. The letters patent of 1573 mention the chancel, its aisles, and a lady chapel to the E. and a 'little chapel' on the S.; their relative sizes may be gauged from the prices paid for their roofs on demolition later in the same year. The chancel roof cost £6.13.4., two roofs probably from the aisles cost 13s.4d. each, and the Lady Chapel roof and a 'long roof' perhaps from the 'little chapel' cost 23s.4d. (PRO, E101/622/35; E101/463/23). Stalls from the choir survive at Tansor and Hemington churches and there are three misericords at Benefield church; these are liberally embellished with Yorkist badges.

The contract of 1434 required the nave to be 80 feet (24.4 m) long, built on to the choir, and there was to be a tower 80 feet high at the W. end, and N. and S. porches. The S. porch was to connect with the cloister of the college. However, the contract is at variance with the building as executed. It stipulates a building with ten pillars and four responds, implying a plan with two arcades each of six bays, whereas the present arcades are of four bays. Similarly, there were to be six flying buttresses on each side of the nave and two each side of the tower, so conforming with a six-bay arcade. Such a building, based on the bay-widths of the nave as built, would have been of the same size as that specified in the document. One clause refers to the arcades being of 'five arches above the steeple', an arrangement which is contradicted by other conditions in the contract; it can perhaps be best explained by assuming that 'arch' was written instead of 'pier'. It is clear that the tower was always intended to have extensions of the aisles on the N. and S., and except for the shortening of the arcades by two bays, the specification was adhered to. The contract also described in great detail the arrangement at the E. end of the nave. The two eastern respond walls are referred to as 'perpeyn walls' (i.e. walls of single thickness ashlar) flanking a central door to the choir. Each wall was to have a window of three lights, presumably clearstorey windows, and piscinae in each side to serve four altars, two flanking the choir door and one in each aisle. A stone screen and traces of the central door survive below the choir arch which was blocked in 1573. The arrangement suggests that the E. end of the nave and aisles formed an ante-chapel to the choir, following a monastic model. It is therefore likely that there was a screen between the first piers of the nave to enclose this area required by the college for access to the choir from the cloister by way of the S. porch. This porch was of two storeys and there was a corresponding floor in the S. aisle perhaps with a stair. The suggested screen, which would have served as a reredos for a central parochial altar, may have held the rood referred to in the early 16th century: twenty pence was bequeathed 'to the rode light' in 1536, and two years later one Richard Davy asked 'to be buried in the mydle allye [before] the crucyfyx, betwyxt the west dore and mayster Coterylls gravestone' (Arch. J., LXX (1913), 324).

The only part of the church which was not completed by c. 1441 was the vaulting in the tower. A vault was stipulated in the contract and the springing for it survives below the present fan vault added in 1529. The design of this fan vault may be compared with that in the retrochoir of Peterborough Cathedral, which was constructed during the abbacy of Robert Kirkton, 1496– 1528 (for similar vaults see J. Harvey, English Medieval Architects (1954), 285).

The residential buildings of the college were finally demolished after 1662 and are now only represented by earthworks; excavations by Oundle School in 1926 revealed foundations which define a cloister about 18 m. from E. to W. and somewhat less from N. to S. (RCHM, Northants. I, Fotheringhay (35); Oundle School magazine (1927); Northants. Archaeology 11 (1976), 177, 179); there were apparently six four-light windows on N. and S., and five on the other sides. The N. range contained a library, and was connected to the church by a two-storey block; all of this range and the N. side of the cloisters were demolished before 1609. Around the other three sides of the cloister were two-storey ranges of chambers, four chambers on each storey on the E. and W., and three on the S. along with two corner chambers and a parlour with a great chamber above. This last room was possibly part of the master's apartment. In 1442 there does not appear to have been sufficient accommodation for fellows and choristers to have a single room each. To the S., probably in a parallel range, were a hall and guests' chamber, with kitchen and service rooms to the E. (BL, Harl. MS 608; PRO, E317/145; NRO, transcript 45a). There was no chapter house, the Lady Chapel being used instead for visitations (LRS, 14 (1918), 108).

Fig. 87 Fotheringhay Church E. wall showing outline of nave of earlier church and subsequent development

The sale of the college buildings in 1557 and demolition of the choir in 1573 led not only to the blocking of the choir arch but also to the removal of the S. porch and the blocking of openings between it and the S. aisle. In the nave new tombs of elaborate Classical design were constructed to replace those commemorating members of the House of York in the choir. Also, floor slabs originally with brasses of priests of the college were reset in the nave. Since the 16th century the fabric of the church has been little altered but the original glazing, recorded in 1719 (Bodleian Library, MS Top. Northants. f1, 121–4; e5, 325–33), was almost entirely destroyed between 1787 and 1821 (Bib. Top. Brit.; Bonney, Historic Notices). A few quarries from the nave are preserved in King's Cliffe church (q.v.; for full account see Marks, op. cit.). The most important 15th-century fitting to survive is the pulpit which bears the arms of Edward IV.

Although only half its original size the church is an outstanding example of Perpendicular architecture. Its royal patronage, its association with a large college of priests and the survival of a detailed contract for its construction combine to emphasize the importance of this impressive building.

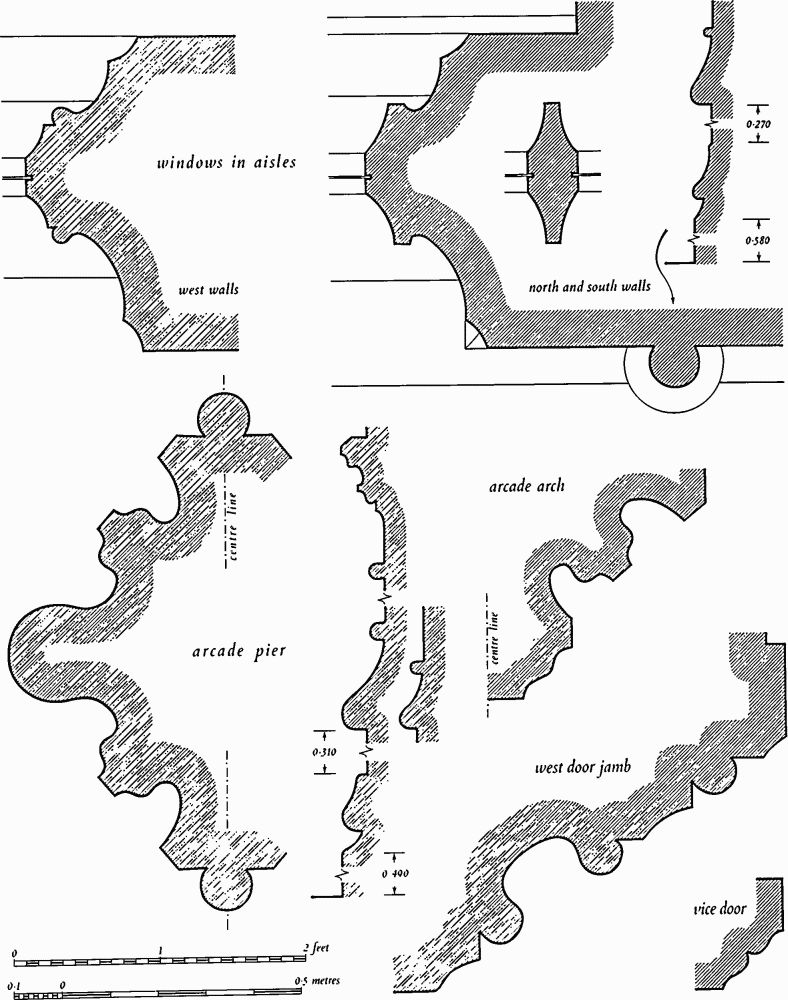

Architectural Description – The church consists of a Nave, North and South Aisles, West Tower and North Porch. The walls are constructed of limestone rubble with an external facing of finely-jointed masonry; the roofs are flat-pitched. The Nave of the present church has an E. wall with three tall buttresses built at the demolition of the collegiate choir in 1573. The E. wall of the former nave is incorporated in the existing E. wall, and is defined by straight joints on the N. and S. and by a roof line visible internally (Fig. 87). Within this early wall is a blocked arch formerly opening into the choir. It has jambs which terminate well above floor-level showing that there was a solid stone screen across the lower part. A patching in the wall behind the central buttress indicates the position of a door. Above the arch is a five-light window with a four-centred head; it was initially above the old nave roof and lit the choir, but with the construction of the present nave it became internal. A fragmentary ogee-moulded base in the angle between the E. wall and the N. buttress, of slightly different design from those in the nave, originally formed part of the base of the N. W. respond of the choir arcade. Adjacent to this base are some worked stones, chamfered on one side; they may be associated with the insertion of the respond close to the old nave wall.

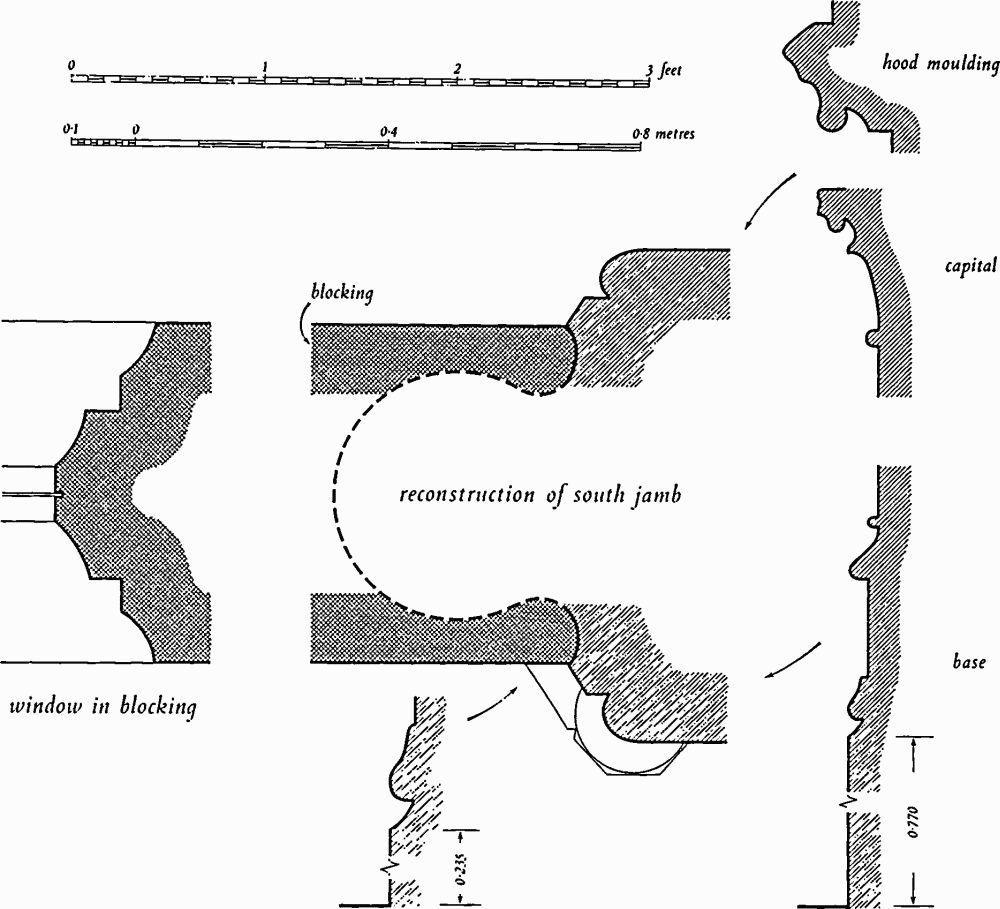

Fig. 88 Fotheringhay Church Mouldings of E. wall of S. aisle, c. 1414 with early 15th-century blocking

The N. and S. arcades of the nave (Plate 47), constructed under the contract of 1434, are each of four bays with long E. responds. High in the S.E. respond is a square-headed window with plain mullions; which was doubtless associated with the medieval upper floor at the E. end of the S. aisle. The outer order of the arches of the arcades are continuously moulded and the inner order is carried on shafts with caps and bases (Fig. 89). There are wall shafts facing the nave and aisles, the former rising into the clearstorey, crossing a string-course at sill level and carrying the wooden wall posts of the roof. The clearstorey has an embattled parapet and a string-course enriched with grotesque heads. The wall is supported by flying buttresses which spring from pinnacles above the aisle buttresses. The windows have four graduated lights except for those in the E. bay which have three.

The North Aisle has a N.E. angle buttress built when the choir was demolished. The side buttresses have crocketed pinnacles. In the E. wall is an arch originally leading into the choir aisle with which it was contemporary. In the 16th century the arch was blocked and the upper part of the wall rebuilt with a half gable containing a pointed-headed opening; the pitch follows that of the flying buttresses over the aisle. Windows in the N. aisle have vertical tracery with quatrefoils; the first is of three lights, as stipulated in the contract, the remainder of four (Plate 49). The N. doorway has a four-centred head, rectangular surround and spandrels enriched internally with roses. Above, a window, opening from the upper room of the porch, has three lights. A small doorway, W. of the last and serving a stair turret is double-ogee moulded. The W. window follows the general design of the main windows but has an extra bowtel moulding (Fig. 89).

The South Aisle (Plate 46) has in the E. wall an arch, contemporary with the choir; it was blocked at its construction and has remained so. Within the blocking is a window with graduated lights, also early 15th-century; it has jambs which are similarly moulded inside and out, and was thus designed to be internal (Fig. 88). The aisle windows (Plate 49) are uniform with those on the N. The first two bays of the side wall contain various blocked openings connected with the former south porch. On the ground floor are two large blocked square-headed openings; that on the E. was a window of three lights incorporating a small doorway, and that on the W. was a large doorway. Within the blocking of the latter is a reset rectangular blocked opening. At a higher level is a blocked rectangular window and on its E. a small blocked door. Some lengths of the E. and W. walls of the porch survive: on the E. the wall has a moulded plinth, and a window jamb which follows the form of the aisle windows; on the W. is a door jamb, the dimensions of which suggest a doorway of some importance, perhaps associated with a processional way. These features indicate a two-storey porch with the main access to the church on the ground floor; an upper floor at the E. end of the S. aisle was reached by way of the smaller, upper door. A long cutting in the aisle wall shows the extent of this floor.

The Tower is of three main stages, the lowest being rectangular in plan, the others square. Above is an octagonal lantern. There are arches on the E., N. and S., and a W. doorway. The design of the arches broadly follows that of the nave arcades. Above the E. arch is a blind recess, masked by the nave roof. The W. doorway has a pointed head in a rectangular frame with spandrels containing shields in quatrefoils (Fig. 89). A large W. window of eight lights has a heavy central mullion which continues into the head; the flanking window forms are united by a transom at the springing (Plate 49). The second and third stages have wide clasping buttresses terminating in octagonal turrets with embattled parapets. Within the parapets of the N. pair of turrets are remains of sculpture, now much weathered. The openings in the second stage are small and of two lights. Those in the upper stage have four graduated lights with transoms and pronounced central mullions. The lantern has an embattled parapet and triangular pilasters at the corners, enriched with niches and terminating in pinnacles. The eight large windows each have three lights with a transom above cusped heads, broadly following the design of the aisle windows; below the springing is blind panelling. Within the tower is a fan vault (Plate 51); a band slightly above the N.W. springing is inscribed 'AnOd1529m'. The crude springings supported on demi-angels belong to the main fabric of 1434 and indicate that a vault of different design was originally intended. The fan vault has a central aperture for bell-raising and quadrant fans embellished with cusped panelling and brattishing.

The North Porch is divided on the ground floor to provide an entrance on the E. and a room on the W.; on the first floor is a single room. In the S.W. corner is a stair turret, entered from the aisle, which gave access to the ground-floor and upper rooms, and then to the aisle roof from which the second stage of the tower is reached. In the E. wall are rectangular windows, the lower blocked, the upper of three cinque-foiled lights. The archway on the N. has a continuous outer order and shafted inner order. A doorway in the dividing wall is probably 16th-century. The upper window on the N. is rectangular and of four lights. On the first floor the large room has two cusped niches at the E. end. In the N.W. corner are remains of a stone hearth which, although supported on wooden joists, is apparently original; a flue, no longer visible, may have been in the thick W. wall. It is not known whether the treasury, referred to in the Statutes as being in the form of a tower, was in the N. or S. porch.

The 15th-century nave Roof of five bays has principal rafters, collars, purlins and ridge-pieces, embattled wall plates and braced wall posts which rise from wall shafts; at the junctions of the principals and the purlins are floriated bosses. The aisle roofs, of seven bays, are double-pitched internally with ridge-pieces, braced tie beams and wooden wall posts rising from wall shafts, all much restored.

Fittings – Bell-frame: of oak, with five pits, 15th-century. Bells: four in tower and priest's bell hung in room over porch: (1), 1595; (2), 1614; (3), 1609, recast 1860, G. Mears founder London; (4), by Thomas Norris, 1634; (5), priest's bell, by T. Mears of London, 1817. Brasses and Brass Indents. Brass: of Thomas Hurland, schoolmaster, January 1589, rectangular plate inscribed in black-letter in English and Latin. Indents: all in slabs of Purbeck marble, with rivets in sinkings and lead-pouring channels, 15th-century; in nave (1), within sanctuary, cleric under cusped and crocketted canopy with side pinnacles, scroll coming from mouth, marginal inscription fillet and angle-roundels; (2), adjacent to (1) and precisely similar; (3), largely obscured by monument (2), apparently similar to (5), fragment of brass surviving; (4), cleric under cusped and crocketted canopy, side pinnacles, marginal fillet, quatrefoil angle-roundels; (5), cleric, with surrounding sinking for a large area of brass, cusped architectural setting, scroll coming from mouth, marginal fillet with quatrefoil angle-roundels. In N. aisle (6), figure in armour, head on helm with mantling (?), children at base, marginal fillet returning below male figure, four shields and nine sinkings for heraldry (?), second half of 15th-century. In S. aisle (7), male figure, rectangular inscription plate, 15th or 16th-century. Doors: on N. and W., with two leaves, fielded panelling, both early 19th-century. Font: octagonal, bowl with cusped panels enclosing paterae, underside carved with leaf forms and lions' heads, panelled stem, renewed and altered foot pace, 15th-century. Gates: in porch (1), cast-iron, mid 19th-century; at entrance to churchyard (2), cast-iron, standards of Greek pattern, gates of lattice work, mid 19th-century. Glass: for glass formerly at Fotheringhay, see King's Cliffe church; for destroyed glass, see Marks, op. cit.

Fig. 89 Fotheringhay Church Mouldings of nave, aisles and tower c. 1434

Monuments and Floor slabs. Monuments: in the nave (1), within sanctuary, of Richard Plantagenet, third Duke of York, father of Edward IV, killed at the Battle of Wakefield in 1460, also of Cecily his wife (d. 1495). This and monument (2) (Plate 52) on the S. side of the sanctuary were constructed to receive the burials when the choir was destroyed in 1573. The monuments, of limestone and clunch, are almost identical in design differing only in some carved detail and in their heraldry. Built in a classical Renaissance style, the effect is architectural rather than sculptural. The infilling above the chest is abnormal and the random use of clunch and limestone is unusual. The chest has pilasters on the front and W. end, the faces of which and the spaces between are panelled and decorated with the Yorkist badge of a falcon within a fetterlock. The upper part consists of twin Corinthian columns which rest on the outer pilasters; the narrower central pilaster terminates abruptly at the top of the chest with only a column base. The columns support an entablature decorated with more Yorkist badges and on the cornice is a small semicircular 'pediment' in the centre. Between the columns is an elaborate carved panel of strapwork and foliage enclosing a shield of England and France quarterly with a label of five points impaling Nevill (for Cecily, daughter of Ralph Nevill, first Earl of Westmorland); above is a coronet decorated with fleurs de lis and trefoils. Monument (2) (Plate 52) of Edward, second Duke of York, killed at Agincourt in 1415, repeats monument (1) in reverse; the arms are of England and France quarterly with a label of five points and above is a coronet. (3), attached to second pier, of Katherine Hutchinson (West). 1826, cartouche of early 18th-century character with lozenge of arms of Hutchinson impaling West, perhaps mid 19th-century. In N. aisle (4), of Rev. Robert Linton, 1832, vicar and schoolmaster of Fotheringhay, and Mary his wife, 1846, plain tablet by Gilbert of Stamford. In S. aisle (5), of Rev. John Morgan, incumbent of Warmington, Apethorpe and Newton, schoolmaster of Fotheringhay, February 1781, and Alice his wife, January 1785, black marble tablet, stone surround comprising carved pilasters, broken pediment and shaped apron enriched with fruit and flowers.

Floor slabs: in nave (1), of Augustnie Forster, 1723, black-letter inscription, pitch-filled, shield of arms of Forster in a scroll-work surround; (2) of Thomas Forster, 1697, with shield of arms of Forster; (3); of John Newton, 1701; (4), of . . . Forster, lozenge of arms of Forster; (5), of Elizabeth Southwell, 1782, black marble tablet set in stone slab; (6), of John Southwell, 1801, as (4); (7), of Elizabeth Southwell, 1828, as (4); (8), of William Thrumpton, February 1695, pitch-filled inscription; (9), of Rev. George Griffiths, 1780; (10), of Letitia Hicks, 1796; (11), of Edward Hicks, 1802; (12), of John Tool . . .. 1728. In N. aisle (13), of Rev. Richard Robinson, vicar, 1775; (14), of the twin daughters of Rev. Robert Linton, 1806; (15), of Martha Linton, 1816; (16), of George Linton, 1831, set in slab with brass indent (6); (17), of Mary Linton, 1826; (18), of Rev. Robert Linton, 1832 and Mary his wife, 1846; (19), of Elizabeth Linton n.d. In S. aisle (20), of Rev. John Morgan, 1781, and Alice his wife, 1785, on slab with brass indent (7); (21), of John Morgan, January 1767, and Sarah, 1814; (22), of Charlotte Bonney, 1779; (23), of Mary Witwell, 1792; (24), of Thomas Blewie, 1682; (25), of Ann Whitwell, 1792; (26), of Mary Whitwell, February 1794; (27), of John Whitwell, 1780; (28), of John Maidwell, 17 (9.?); (29), of John Maydwell, 1785; (30), of Elizabeth Maydwell, 1793; (31), of Sarah Parris, 1748.

Pulpit (Plate 53): polygonal and asymmetrical to include wing from stair; panelling in two heights, the upper cusped, second half 15th-century on modern (?) post, with 17th-century tester above an original canopy with cusping, with cut-card enrichment, back board with remounted shield of arms of Edward IV with engrailed lower edge, supporters and crown; altered in modern times and repainted in 1967. Rain-water head: now over N. door, lead, with date 1646 and initials IP/GW. Reredos: triple panels, Gothick outline, tables of the Law and Commandments, probably 1817 (illustrated in 1821 by Bonney, Historic Notices, opp. p. 53).

Seating: stalls from the collegiate choir survive in Tansor and Hemington churches (q.v.). Reset on the font cover are two fragmentary misericords, one a demi-female, the other a male head with a fool's cap, 15th-century. Other misericords from Fotheringhay are at Benefield in the same county; they are carved with foliage, a grotesque head and a lion's head. Seating was removed from the nave in 1817 and some was reused in King's Cliffe (q.v.) for a pulpit, reading desk and pews. The present box pews, of oak, were installed in 1817 under the direction of Thomas Belsey, owner of the Fotheringhay estate (Gents. Mag., Dec. 1821; Peterborough Advertiser, June 1863). Stoup: in N.E. pier of tower, with four-centred head, multilated, 15th-century. Weather-vane: in form of falcon and fetterlock was provided at the instigation of Thomas Belsey in 1819 (letter from Thomas Belsey to W. Bradshaw, 1 July 1819 – NRO, Y2 4356). Miscellaneous: loose in tower, stone panel with carved crowned lion rampant.

Secular

(2) Garden Farm (Fig. 90; Plate 79), formerly the New Inn, was built by Edward IV some time after his accession in 1461 as indicated by heraldry around the gateway. It had been completed by 1476 when custody was given by the king to his servitor John Russell 'to hold, with all profits, without rendering account' (Cal. Pat. (1467–77), 563). The heraldry represents four generations of Edward's family and other decoration includes Yorkist badges; this display may be compared with the heraldry contained in the glass formerly in the collegiate church (Marks, JBAA, CXXXI, 97). The building's function was probably to provide supplementary accommodation for visitors to the castle, and this and the Old Inn can be compared with the two lodgings formerly flanking Bailiffgate, the approach to Alnwick Castle. In a survey of 1624 it was described as the New Inn and as belonging to the castle, and containing hall, parlour, kitchen and 'divers other chambers', but otherwise its later history is obscure (Bonney, Historic Notices, 4). Engravings of 1786 (Bib. Top. Brit. no. 40, p. 20) show a similar arrangement of buildings as exists today except for a first-floor gallery along the rear of the main range, but it is not clear whether this was an original feature, and no trace of it remains today. In 1842 when it was part of the estate bought by Lord Overstone the building was a farmhouse (NRO, 0.160).

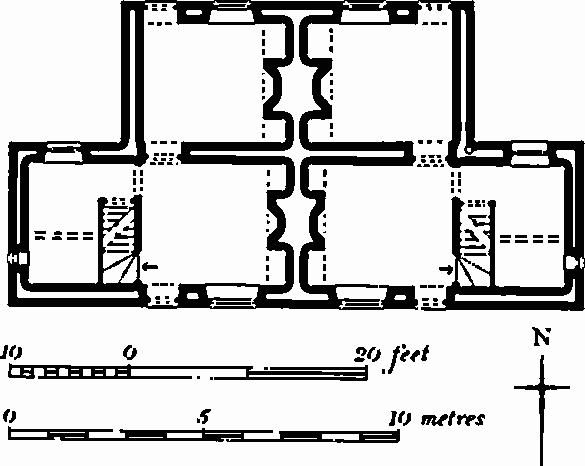

Fig. 90 Fotheringhay (2) The New Inn Plan and section through former open hall

The building, of coursed rubble, partly with original rendering, freestone dressings and stone slated roofs, has a main range lying parallel to the street, pierced by a central gateway which separates the former open hall on the W. from the two-storey E. end. The main range, built between 1461 and 1476, has two wings, the western continuing forward as a cross wing; the E. and S. walls of this wing are also 15th-century, but the W. wall and the N. part are mid 19th-century reconstructions. The rear wing, at the E. end of the main range, was rebuilt later in the 19th century.

In the centre of the S. front of the main range is an enriched gateway flanked by buttresses. It is rebated for doors and has chamfered jambs and a moulded four-centred head with traceried spandrels and a label stopped on demi-angels holding shields of arms. Above is a band of cusped panels containing blank shields and roses, and a square-headed window of two cinque-foiled lights with a label and stops similar to those below. The arms on the shields carried by angels are now eroded but in 1821 Bonney (Historic Notices, 4) interpreted them as, on gateway, Castile and Leon quarterly, and Mortimer; on window, France and England quarterly, and France and England quarterly impaling Nevill. If correctly recorded, these represent Isabel, daughter of King Pedro of Castile and Leon; Anne, daughter of Roger Mortimer, Earl of March; Edward IV; Richard, third Duke of York, and his wife Cecily (Nevill). To the E. of the archway are upper and lower cinque-foiled windows of the 19th century and a large four-light transomed window which, although a complete restoration, is in the position of a former large window; above the last is a renewed two-light casement-moulded window with original label stops, one carved as a rose and the other a collared and chained animal. Two casement-moulded windows W. of the archway have cinque-foiled lights and labels, and light the compartment occupied by the hall at a low level only. The N. side of the gateway has chamfered jambs supporting a beam and an original close-studded timber-framed upper wall which extends only the width of the archway. All the openings on the N. side of the range are 19th-century including a doorway with a four-centred head which relates to the use of the hall as a stable. The E. gable has a parapet with terminal figures of crouching animals, one being a lion; to the side of the original stack are blocked cinque-foiled windows, one of which has a label with stops carved as animals.

The E. section of the main range was always of two storeys. The ground-floor room, perhaps the parlour of 1624, was sub-divided in the 19th century, and retains intersecting moulded ceiling beams and a wall beam carried on stone corbels. The fireplace (Plate 127) has chamfered jambs and pyramid stops and a four-centred ogee and hollow-moulded head. The section W. of the gateway, now stables, was formerly an open hall of two roughly equal bays. Inside at first-floor level the E. wall of the hall is timber-framed above an embattled sill which overhangs the lower masonry wall. It is close-studded with a tie beam and collar, and an in-filling of hard plaster. The central truss (Fig. 90) has an arch-braced cambered collar with a roll and hollow moulding, two cranked struts, one tier of butt-purlins and wind-braces. The principals rise from sole plates provided with large pegged tenons to carry carved features, probably figures, now missing. The W. truss has a cambered tie beam, struts to the collar, and wind-braces, but with no indications of a framed wall below the tie beam.

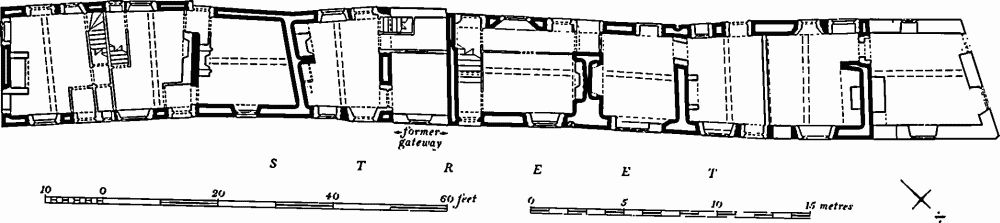

Fig. 91 Fotheringhay (3) The Old Inn

The W. range, projecting S. of the main range, has several original blocked openings. On the E. a blocked doorway with a moulded four-centred head, label and stops, is set well above ground level. Adjacent to the door is a blocked window with a label, formerly of two lights. The engraving of 1786 shows two upper and one lower single-light windows, all apparently 15th-century, but now obliterated by later rebuilding. The S. gable wall has blocked openings asymmetrically placed. Formerly with a buttress against the W. corner, the wall has a blocked doorway, lower than that on the E., with a four-centred head; a label stop is possibly carved as an angel. The relative disposition of these two adjacent doorways cannot be explained. The upper and lower blocked windows were probably of two lights; a rose is carved on one label stop. The openings have internal wooden lintels. The remainder of the wing was rebuilt in the 19th century, but an earlier roof, possibly of the 18th century, remains. It is of six bays with tie beam, staggered butt-purlins and collars. There is no indication of the positions of the original internal partitions.

(3) Nos. 10, 12, 14, 15, 16, 17, formerly the Old Inn (Fig. 91; Plate 78), dates from the 15th century. On the evidence of the name it predates the New Inn (2) constructed between 1461 and 1476. Like the New Inn it provided accommodation for visitors to the castle, but it never had the architectural elaboration of the later building; it was subsequently sub-divided into eight cottages, considerably altered and partly rebuilt, the W. tenement being added in the 19th century.

The range is of two storeys with rubble walls and thatched roof; the piecemeal refronting and repair of separate tenements mainly in the 19th century has left a number of straight joints and has obscured the original internal arrangement. There was a wide central gateway, now blocked, the plain jambs of which rise above the upper floor level. On either side were two small rooms, and a large room at each end of the range. The room W. of the gateway is entered from the street by a 15th-century doorway with wooden frame and four-centred head (Plate 83); the fireplace has a chamfered four-centred head; the staircase is 17th-century. The next room W. has a fireplace with rectangular head; the lobby to the S. of the stack is approached by two doorways with wooden frames and four-centred heads. The two rooms E. of the gateway are separated by a skew wall which looks like an insertion, but a corbel on the W. face supports a blocked first-floor fireplace whose embattled stack remains embedded in the 19th-century chimney. Of the two end compartments, the E. has been entirely refitted; the W. one has three transverse beams and indications of a partition below the W. beam although this beam could be a replacement as the fireplace with cambered bressummer may be original. On the first floor this W. compartment is divided into two equal rooms by a close-studded partition without evidence for an original door. This indicates separate access to the two rooms; the absence of evidence for internal stairs and the possibility of an external door on the rear wall to the W. of the gateway suggest external access to the first floor. Much of the original roof remains, but could not be examined.

Fig. 92 Fotheringhay (9) Nos. 26 and 27

(4) Garden Cottage, one storey and attics, thatched roof, class 4a, 17th-century with some refitting in the 19th century.

(5) Former Vicarage, two-storey, two-room front range of 18th-century origin, altered in the early 19th century and extended to the E. after 1900. The rear wing, of 17th-century origin, was cased and extended in the 19th century.

(6) Falcon Farm, was built in the first quarter of the 19th century by Thomas Belsey for his steward (Bonney, Historic Notices, 11); it was subsequently enlarged by R. S. Tomlin, Belsey's cousin, who inherited the estate. It is of two storeys with ashlar dressings and sash windows, but has been greatly altered and extended. Farm buildings of the second quarter of the 19th century include a barn, stable range and cart lodge.

(7, 8, 9) Row, Nos. 21, 23, and two pairs Nos. 24, 25 and 26, 27 (Plate 117), were built by Thomas Belsey in the first quarter of the 19th century (Bonney, Historic Notices, 11). They are of two storeys with hipped roofs and brick stacks; originally all the windows had cast-iron lattice casements. The row was built as three two-room dwellings. Nos. 24, 25 have the same plans as Nos. 26, 27 (Fig. 92) and all have secondary wings at the back.

(10) The Thatched Cottage, one storey and attics, originated as a class 4a house of c. 1800. To the E. a barn was built at approximately the same time; this was converted to a dwelling sometime after 1842 (NRO, 0.160), and both parts, formerly with central doorways, are now united. Behind is a row of three two-storey cottages, Pigeon Row, built shortly before 1842 and recently modernized.

(11) Tall Trees, No. 33 (Fig. 93), two storeys, originally a pair of class 4a houses with a one-storey rear wing containing a washhouse and privy for each house, early 19th-century. A Gothick appearance is given by the pointed-headed openings, the windows having Y-tracery. Some door and window openings were interchanged when the dwellings were united.

Fig. 93 Fotheringhay (11) Reconstruction of original plans

(12) Farmyard, formerly College Farm Yard (NRO, 0.160), consists of a barn and open sheds, early 19th-century.

(13) The Falcon Inn, two storeys, formerly class 6a with rear wing, early 19th-century. The symmetrical front has freestone dressings, sash windows, and a pedimented door-case. Interior now gutted. To the W. is a one-storey building, perhaps a contemporary club room.

(14) House, two storeys, thatched roof, of two rooms with an internal stack, 17th-century. (Not entered)

(15) Post Office, two-storeys, class 4a, built at right angles to the street, 18th-century.

(16) College Farm House, two storeys, class 6a with rear wing, early 19th-century. Shortly after 1842 a kitchen was built in the angle (NRO, 0.160), linking the house with an already existing detached single-room building of two storeys with large sash windows. The walls are of neatly coursed rubble, most of the windows have sashes and the main door has a porch with slender columns.

(17) A pair of early 19th-century cottages of two storeys with hipped roofs; class 4a plans with shared stack and entrances in the end walls.

(18) Lodge Lawn, two storeys, originally two class 4a dwellings, now united; built after 1842 (NRO, 0.160).

(19) Fotheringhay Lodge (TL 074947), of two storeys with cellar, and with freestone dressings and sash windows, was built in the early 19th century by Thomas Belsey. It has a class 8 plan and was extended to the N. after 1842 to incorporate an already existing single-room cottage (NRO, 0.160); the S. front was also remodelled. Of the extensive farm buildings only a large barn is contemporary with the house; two long cattle lodges with elliptical-headed openings along one side, and a wagon lodge with similar openings date from after 1842. W. of the farm buildings is a two-storey, early 19th-century, cottage.

(20) Fotheringhay Park Lodge (TL 062943). The deer park at Fotheringhay was created c. 1230 (RCHM, Northants. I, (36)) and may have had a lodge from the beginning. In 1547 the lodge was mainly timber-framed (PRO, E101/463/21). In an agreement made with a new tenant in 1713 it was described as Park Lodge Farm suggesting that some or all of the park had by then been converted to agriculture (NRO, F.H. 286). The farmhouse, barns and probably the W. range of cow sheds appear on the map of 1842 (NRO, 0.160); the cottage adjacent to the farm buildings, and the rear wing of the house are later. The farmhouse, class 8 and roofed with two parallel roofs, has freestone dressings and sash windows. The parlour retains a ceiling with moulded cornice and angle-paterae. The Farm buildings on the W. (Fig. 6) include a double barn, two ranges of cattle lodges with stables and a row of pig sties.

(21) Walcot Lodge (TL 051938), two storeys, freestone dressings and sash windows, class 8 with two parallel roofs, early 19th-century. The farm buildings which included a barn and cattle lodges have been demolished.

(22) Bridge over R. Nene (Plate 75). The earliest reference to a bridge is in 1498 when a bequest was made for its repair (PRO, Prob. 11/11). Leland says it was of timber (Itinerary I, 5) and in 1551 it was in need of rebuilding (King's Works III, pt. 1, p. 249). This early bridge may be associated with a causeway carrying the road S. across the Nene flood plain. There were several bequests for the repair of this causeway between 1546 and 1562 (PRO, Prob. 11/31). The bridge was replaced in 1573 at a cost of about £180, of which £100 was given by Sir Walter Mildmay and the remainder came from the sale of materials of the collegiate choir. Lord Burghley's mason, Haward, advised on the project and the contractors were William Gromball and Thomas Haywood (?Haward); the stone came mainly from King's Cliffe, timber from Sulehay and Cotterstock and lime from Peterborough and Oundle (PRO, E101/463/23). Bridges records that it was of four bays, with masonry piers supporting a timber roadway; the masonry parapet bore a tablet inscribed 'This bridge was made by Queen Elizabeth in the 15 yere of her Reygne A° Dni 1573' (Bridges II, 449).

Fig. 94 Glapthorn Village Map

The present bridge was built in 1722 to designs by George Portwood of Stamford using stone from King's Cliffe (Gent's Mag. 1827 pt. 1, 401–2). It is of ashlar with four semicircular arches of unequal heights, between cutwaters. Each arch has two chamfered orders and a fluted keystone.

(23) Bridge (TL 062935) over Willow Brook, single span, dressed stone voussoirs, 18th or early 19th-century. To E. of the bridge are retaining walls with sluice gates associated with the watermill. A mill is recorded in 1804 (Sale Catalogue, Burghley Estate Office), but it had probably been demolished by 1832 (NRO, Y2, 4361, Insurance Valuation; NRO, 0.160, map of 1842).