An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in the County of Northamptonshire, Volume 2, Archaeological Sites in Central Northamptonshire. Originally published by Her Majesty's Stationery Office, London, 1979.

This free content was digitised by double rekeying. All rights reserved.

'Irchester', in An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in the County of Northamptonshire, Volume 2, Archaeological Sites in Central Northamptonshire(London, 1979), British History Online https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/rchme/northants/vol2/pp90-99 [accessed 28 April 2025].

'Irchester', in An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in the County of Northamptonshire, Volume 2, Archaeological Sites in Central Northamptonshire(London, 1979), British History Online, accessed April 28, 2025, https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/rchme/northants/vol2/pp90-99.

"Irchester". An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in the County of Northamptonshire, Volume 2, Archaeological Sites in Central Northamptonshire. (London, 1979), British History Online. Web. 28 April 2025. https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/rchme/northants/vol2/pp90-99.

In this section

36 IRCHESTER

(OS 1:10000 a SP 96 NW, b SW 96 SW, c SP 86 NE)

The parish occupies some 116 hectares of land S.E. of Wellingborough, and of the R. Nene which forms its N.W. boundary. From a maximum height of 91 m. above OD, on the S. edge of the parish, the land falls gently to the river, here flowing at about 42 m. above OD. A N.flowing tributary of the R. Hene crosses the E. part of the parish in a deep valley. The higher S. and E. areas of Irchester are composed of Great Oolite Limestone, covered in places by Boulder Clay, but the down-cutting of the R. Nene and its tributaries has exposed rocks of the Estuarine Series, Northampton Sand and Upper Lias Clay. The most notable monument of the parish is the Roman Town (7) with its associated extra-mural area. There are, in addition, a number of other important Roman sites. The parish also contains two deserted medieval settlements, both of which were finally cleared at a late date, (8) and (9).

Prehistoric and Roman

Three polished stone axes are said to have been found near Irchester (Plate 31; NM). One is of Group I, another is of Group VI, while the third is of Group XV (PPS, 28 (1962), 262, Nos. 987–9). Part of another axe, probably of Group VI, was discovered in 1976 (SP 920668; private collection). A late 4th-century gold Roman coin of Eugenius was found in the village before 1904 (NM; T.J. George, Arch. Survey of Northants., (1904), 16).

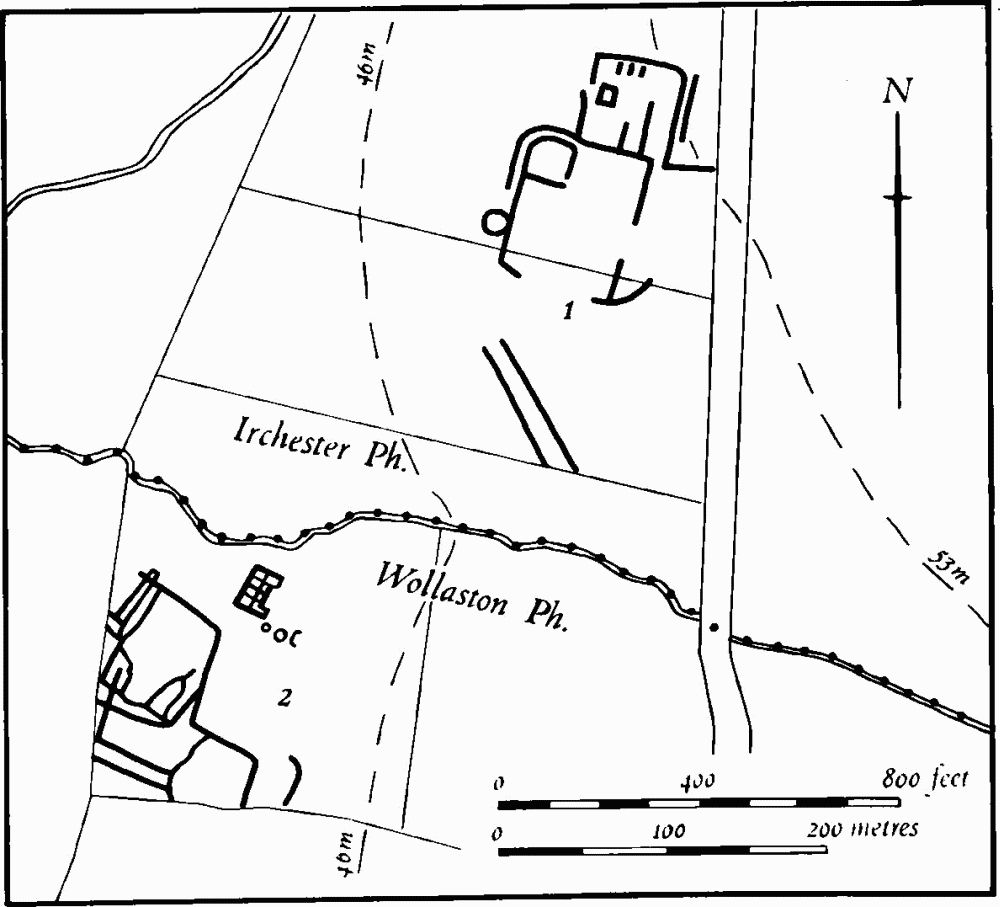

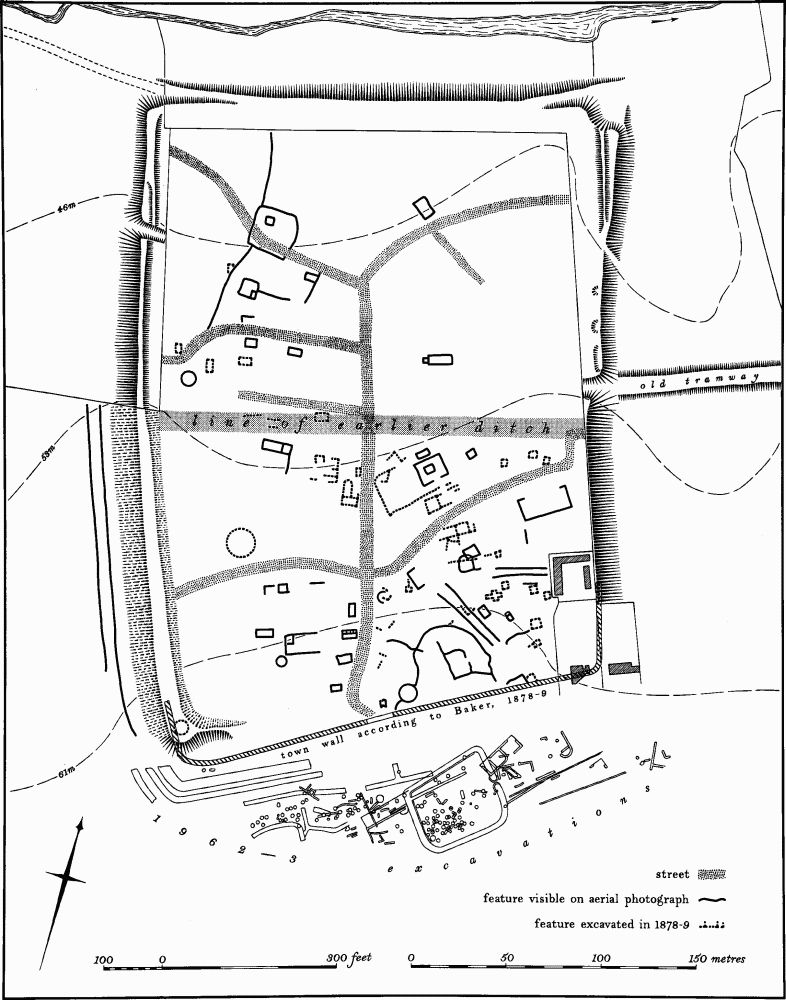

Fig. 85 Irchester (1) Cropmarks and Wollaston (2) Roman villa and cropmarks

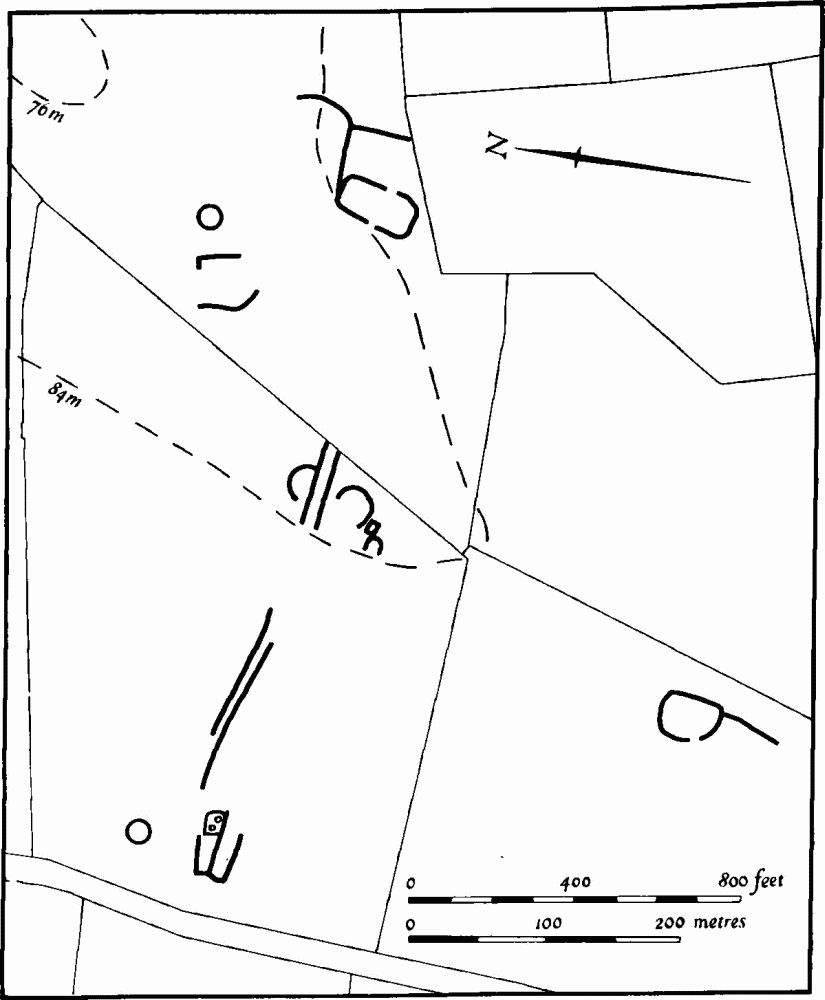

Fig. 86 Irchester (2) Cropmarks

a(1) Settlement (SP 903652; Fig. 85), in the S.W. of the parish, on limestone at 50 m. above OD. Air photographs (CUAP, ZE 71, ZJ 78–83) show parts of a large rectangular enclosure, with an inner enclosure in its N.W. corner and a further enclosure to the N. Part of the interior of the main enclosure and the land to the S. has been quarried away for ironstone. Vertical air photographs also show what appears to be a length of ditched trackway to the S. (RAF VAP 541/611, 4037).

a(2) Ditches (SP 922651; Fig. 86), on limestone at 84 m. above OD. Air photographs (in NMR, and RAF VAP 541/611, 4035–6; 540/RAF/1312, 0278–9) show a number of indeterminate enclosures and linear features, including a possible ring ditch and a trackway, over an area of some 25 hectares.

a(3) Iron Age and Roman Settlement (SP 930653), on limestone at 83 m. above OD. A series of ditches and pits containing Iron Age and Roman pottery were cut by a pipeline trench in 1965 (OS Record Cards).

a(4) Iron Age and Roman Settlement and Kilns (centred SP 943660), E. of Knuston Hall, on Boulder Clay at 76 m. above OD. Excavations in 1971, over an area of 5.7 hectares, revealed ditches, pits, hearths and traces of huts connected with an Iron Age and Roman industrial site. Hand-made and wheel-thrown late Iron Age pottery was being made on the site up to the beginning of the Roman period. This was followed by a short period of intensive activity lasting until the latter part of the 1st century. During this time large quantities of pottery of exotic design were made and fired, in above-ground kilns with movable firebars and central pedestals (Beds. Arch. J., 7 (1972), 14, Knuston (2); Current Arch., 31 (1972), 204–5; Britannia, 3 (1972), 326; 5 (1974), 262–81).

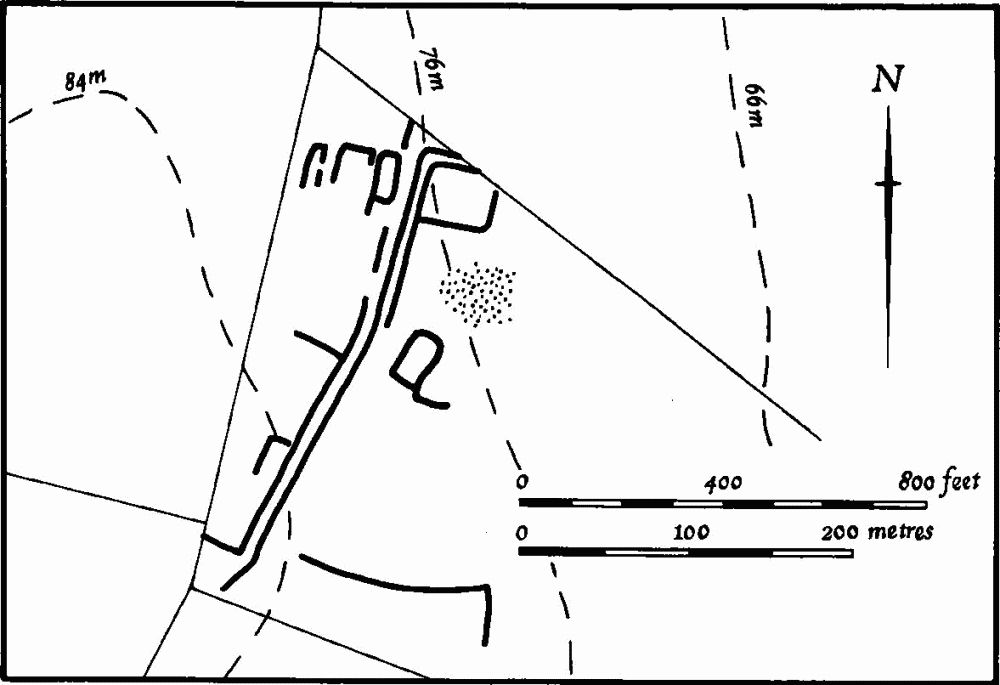

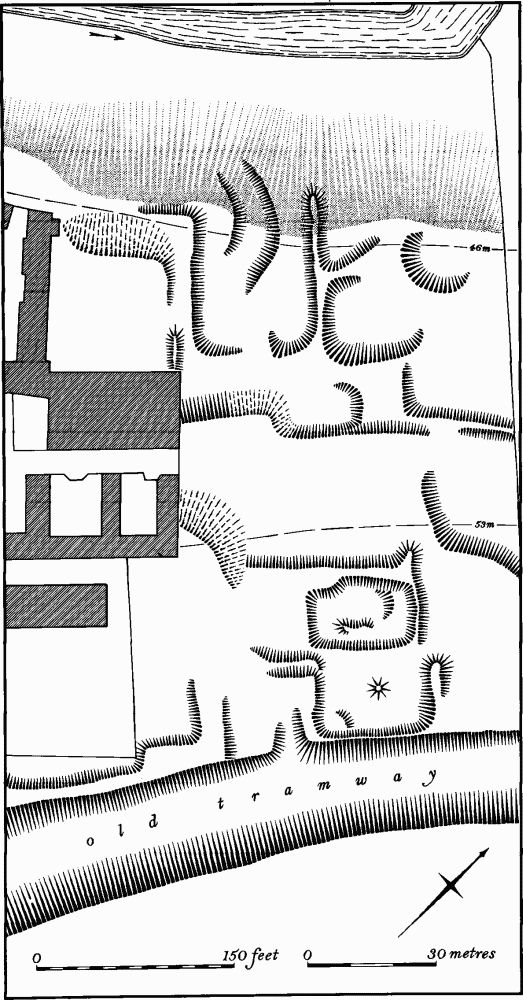

Fig. 87 Irchester (5) Roman settlement

a(5) Roman Settlement (SP 933651; Fig. 87), immediately E. of Irchester Grange, on Boulder Clay at 76 m. above OD. Air photographs (in NMR) show a length of ditched trackway, with a series of enclosures at its N. end and a number of other enclosures and linear features in the general area. Building-stone and Roman pottery have been found on the site (OS Record Cards; Beds. Arch. J., 3 (1966), 5).

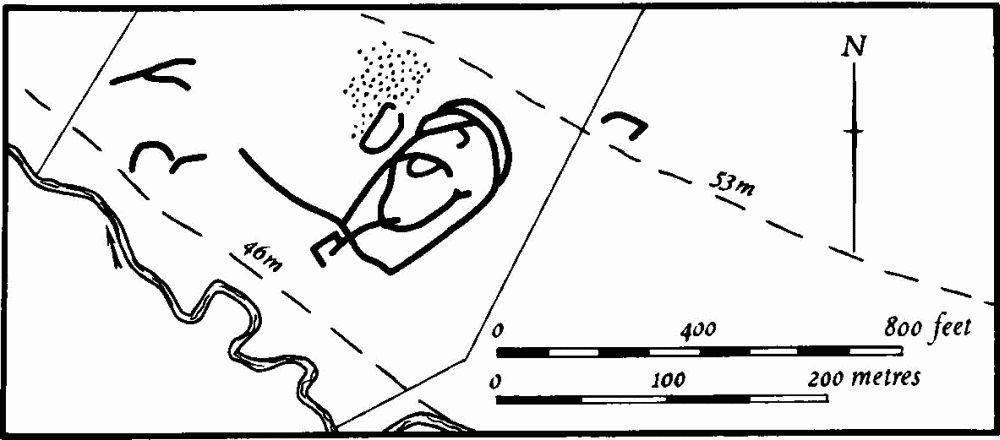

a(6) Roman Settlement (SP 933664; Fig. 88), 500 m. N.W. of Knuston Hall, on sand at 49 m. above OD. Air photographs (in NMR, and CUAP, AGE 8, 9, ZD 96, 97, ZE 10) show an irregular enclosure with complex internal features, a small adjacent enclosure, and a large number of pits to the N.E. There are other ditches in the area but these are not clear on the available air photographs. Roman pottery and a fragment of roof tile have been found on the site, and a number of Mesolithic flints are also recorded (BNFAS, 6 (1971), 14, Irchester (1); Beds. Arch. J., 7 (1972), 14, Knuston (1); OS Record Cards).

Fig. 88 Irchester (6) Roman settlement

a(7) Roman Town (SP 917667; Figs. 11, 89 and 91; Plates 3, 4 and 32), in the N. of the parish, close to the R. Nene, on sand and clay between 45 m. and 63 m. above OD. The site consists of the remains of the walled town and an extensive extra-mural settlement, lying at the junction of two, or perhaps three, Roman roads.

The site has long been recognised as Roman. Camden mentioned it, and Morton in the early 18th century described the walls as still standing (J. Morton, Nat. Hist. of Northants., (1712), 517). Other important finds were subsequently noted, and ironstone-mining in 1873–4 in the extra-mural area E. of the town resulted in the discovery of a large cemetery. In 1878–9 excavations were carried out in the interior of the town by Rev. R.S. Baker (Arch. J., 36 (1879), 99–100; VCH Northants., I (1902), 178–84; Ass. Arch. Soc. Reps., 13 (1875), 88–118; 15 (1879), 49–59). Further excavations were carried out on the ramparts by Dr. W.W. Robb in 1926 (JRS, 16 (1926), 223) and in the following year new ironstonemining produced more evidence from the extra-mural area. Road works in 1962–3 on the S. side of the town led to excavations by the Department of the Environment (Arch. J., 124 (1967), 65–99, 100–128). In addition many finds have been made in the general area, relating to both the town and its extra-mural settlement. All this information, while of considerable value, is often conflicting and no clear picture of the history of the town has emerged.

Historical Summary

Pits or depressions, containing flint arrowheads and scrapers, were noted just to the E. of the town during the 1879 excavations, and other pre-Roman occupation of the site was discovered during the 1963 excavations when an early Iron Age pit was noted immediately S. of the town. Subsequently occupation in the Iron Age was also noticed here. Iron Age coins have been recorded from the area. There is evidence of a 1st-century native settlement around the town, perhaps associated with the establishment of a fort which may have occupied what later became the N. half of the town. The argument that there was a fort rests mainly on the alignment of the remaining earthworks and of a possible ditch system visible on air photographs. A broken pelta-shaped belt buckle and some spearheads (in NM) are the only finds which could have any military significance but this may not necessarily be so. By the end of the 1st century there seems to have been intensive occupation, with some stone buildings, and between 150 and 200 A.D. the existing ramparts around the town were constructed. Much of the then occupied area was left outside the defences. The ramparts were subsequently altered to accommodate an external stone wall.

Over the next two centuries the town acquired an array of stone buildings including a temple around the somewhat abnormal street system; the latter may have been laid out at an earlier date. It was clearly an important and prosperous town, and was, on the evidence of the inscribed slab found in 1853, the centre of an imperial region for horse-breeding. The defences were remodelled in the 4th century, perhaps for artillery, and at least one of the main gates, that on the W., was apparently blocked at the same date. The town appears to have been in decline at this time, and much of the area outside the walls was abandoned.

The later history of the town is unclear. A 5th-century timber building was excavated in 1963 but there is no evidence for later occupation. The Anglo-Saxon material recorded as being found at Irchester in the 19th century is now known to have come from elsewhere (see p. 96). By the 11th century the only settlement in the area was the small hamlet of Chester-on-the-Water (8) which lay to the E. of the town around the existing manor house. This hamlet was entirely deserted by the 18th century and now only the manor house and its farm remain.

The site of the town and its surrounding area were extensively cultivated throughout the medieval period, although the ramparts seem to have remained intact until the 18th or 19th century. Certainly in 1756 (NRO, Map of Chester-on-the-Water) all the ramparts are shown complete and apparently undamaged, though now the S. part of the W. side has been almost totally destroyed by cultivation. The ironstone-mining of the 19th and early 20th centuries has resulted in the destruction of large parts of the assumed extra-mural area and in the late 1920s a tramway for ironstone was cut across the town from E. to W. In 1963 the realignment of the A 45 road led to the partial destruction of the S. side of the town and the adjacent extra-mural area of occupation. However, in spite of the destruction which has mostly taken place during the last 100 years, the site of the town itself remains largely intact and, together with its surrounding area, constitutes a major monument of the Roman period as yet little understood.

Town Defences

The town covers an area of just over 8 hectares and was formerly completely surrounded by large earthen ramparts. The N. side now remains as a massive scarp 6 m. high, falling directly to the edge of the flood plain of the R. Nene. At its E. and W. ends it has been damaged by later tracks. The E. side is bounded by a large scarp 3 m. high with, at its N. end and still preserved in pasture, a shallow trench cut into its summit. Further S. there is a series of shallow depressions, perhaps the result of stone robbing.

Near the centre of this side a narrow gap has been cut through the rampart. This was made in the late 1920s to take the ironstone tramway across the area and the low embankment of the tramway approaches the gap from the E. However on large-scale OS plans, made in the late 19th century before the tramway was built, another gap is shown immediately to the S. This may have been an original gate to the town, for one of the interior streets, visible on air photographs, turns towards it. No trace of the gate now exists, and it may have been blocked when the tramway was built.

The S. side of the town has been cut into by the realignment of the modern road and a modern scarp now marks its approximate edge. The S.W. corner has also been removed, though older OS plans show the position before destruction. On the W. side, the S. half of the rampart has been largely destroyed by cultivation and only remains as a much degraded rise 1 m. high. The N. half still exists as a large bank 2.5 m. high with a flat top. This length is broken through by a narrow cut made for the ironstone tramway.

A close examination of the plan of the surviving defences and of air photographs suggests that the ramparts may not all be of one period. The existing ramparts do not form an exact rectangle for there is a change of alignment of some 5°–8°, at the centre of both the E. and W. sides indicating perhaps that the enclosed area may be made up of two distinct parts. Air photographs show traces of what may have been a large ditch running E.—W. and joining the points where the alignments change. This ditch is overlaid by the main axial street of the town and partly by the southernmost of the branch streets to the E. Thus this ditch may represent the S. line of the defences of either an early smaller town or, more likely, a four-hectare fort connected with the initial advance of the Roman army into this area.

Early observations and later excavations add more information concerning the actual structure of the main rampart. Both the early 18th-century county historians described the walls as they then existed (Morton, op. cit; J. Bridges, Hist. of Northants., II (1791), 181). The town was then 'inclosed with a stone wall in some places about 9 ft. thick, of which the out courses of the stone [were] placed flat-ways, the inward ones end-ways'. During the excavation of 1878–9 the remains of the gates in the W. and S. sides were discovered and some foundations 'not explored' were noted in the centre of the E. side apparently near the assumed original entrance. This latter may have been the E. gate to the town. However the gate discovered on the W. is less easily explained. No road is known to approach the town from that side, although one may be assumed to have done so, and none of the three internal streets on that side of the town meets the ramparts anywhere near the site excavated. Yet the excavator found a massive stone gateway which 'had been dismantled and ruined at some period' and blocked with the reused stone. It has been suggested that this was a 4th-century modification though no dating evidence was noted.

The 1926 excavations cut across both the E. and W. ramparts on the line of the tramway. 'Well built stone walls showing two periods of construction' were discovered. The excavations of 1962–3 on the S. side, carried out by two separate investigators, were more informative. A section was cut through the S. rampart near the S.W. corner. The earliest feature was a small ditch dated to before 68 A.D. which was sealed by a subsequent occupation layer, apparently of late 1st to early 2nd-century date. Above this the main earthen rampart, some 12 m. wide with a stone core, was constructed, with a lightly metalled road at the rear. The date of this rampart was probably between 150 and 200 A.D. At some later but unknown date, the front of the rampart was cut away for the insertion of a limestone-rubble wall at least 2 m. wide fronted by a berm 5 m. wide and a ditch 2 m. deep. A date in the 4th century was put forward by the excavator for this work.

Fig. 89 Irchester (7) Roman town

The S.W. corner of the defences was also examined. Before excavation it comprised a low mound made up of a mass of stone rubble and soil 2 m. thick which contained Roman pottery and some 17th or 18th-century sherds. The excavator interpreted this as a modern spoil heap, but in fact it is more likely to be the site of a small building shown on the 1756 map of the area (NRO) and called a 'Temple'. It was probably associated with the small park laid out around Chester House in the first half of the 18th century. Below this mound a trapeze-shaped limestone structure built into the rear of the town wall was discovered. This was a late corner turret, presumably for artillery and probably 4th-century in date.

Outside the S.W. corner, the other excavation, also in 1962–3, revealed a triple ditch system curving round the town ramparts. The innermost of these ditches appears to be the same as that recognised during the cutting of the section through the town rampart. These triple ditches contained material from the late Iron Age in the primary silt and later Roman pottery in the upper filling. The excavator could not date these ditches but suggested that they were of late Iron Age date, because they were set forward from the later town wall and, in addition, were not parallel to the wall as it was shown on the 1878–9 excavator's plans. However as the wall itself is a late alteration to the original earthen rampart, and the 1879 plan is by no means accurate, this argument does not necessarily follow. More significant is the fact that on air photographs two of these ditches can be traced along the S. part of the W. side of the town parallel with the rampart. They thus appear in plan to be an integral part of the original town defences. However the early date of the pottery in the primary silt makes this unlikely and these ditches may well belong to the military phase of occupation.

Interior of the Town

The interior of the town has been under cultivation for a long time and air photographs clearly indicate a large amount of occupation in addition to that known from the 1878–9 excavations, from chance finds and from field-walking (JRS, 43 (1953), 92). The most obvious feature on all air photographs is the very unusual internal street pattern. The main N.—S. axial street is straight, except at the S. end where it takes a more sinuous course to the town's main gate. At the N. end it bifurcates; one branch curves towards the N.E. and the other towards the N.W. corner of the town. On the E. of the main street a side road runs to the E. gate, again with an unusually winding course. To the W. are three other curving streets, two of which extend to the W. ramparts; the central one, however, though aligned approximately on the W. gate, cannot be traced to it. The main axial road appears to overlie the broad rather indistinct ditch which crosses the centre of the town from E. to W. and which may be the S. side of the assumed early fort.

The air photographs also show a large number of stone buildings and ditches in the interior. Some of the buildings appear to be aligned along the streets, but others do not seem to be related to them. Most of the buildings are rectangular, and internal divisions can be seen in some of them. In addition at least three circular stone structures are visible. The most obvious and clearly identifiable building on the air photographs is a small rectangular temple which lies E. of the main street and N. of the branch street to the E. gate. This temple was partly excavated in the 'extensive turning over' of 1878–9, and part of the main structure was discovered, as well as an outer yard to the S.E. of the temple itself, with a gate into it on the S. side. In the N. corner of this yard a carved capital and the torso of a limestone statue of a nude male figure (Plate 32) were discovered (NM), apparently incorporated in a wall overlying the boundary of the temple yard. To the S. of the temple fragments of at least two groups of buildings were discovered, and to the W. of the latter a large area was also excavated, the only part of the town completely investigated in 1879. Two fragments of sculptured stone, said to be part of an octagonal monument, were found, associated with a paved area.

To the W. of the temple and W. of the main street another group of buildings was explored but the plans are incomplete. Some painted wall-plaster was found. Elsewhere in the interior various lengths of walling and fragments of stone buildings were apparently uncovered, but no details are known; only their outline is shown on the excavator's plans.

Among the small finds discovered during these excavations (mostly in NM) were a clay head of a faun, and a pipe-clay head of a Venus figure, as well as extensive quantities of pottery, including samian and Nene Valley wares, glass, brooches, fibulae, wall-plaster, lead weights, spearheads, tiles, bricks, Collyweston slates and animal bones. There were also many iron objects including knives, drills, part of a sickle, a ladle, shears and the outer casing of a door lock. Large numbers of coins are recorded covering the whole of the period, but there are relatively few of the 1st century.

In 1853 an inscribed slab (in BM; Plate 32) was discovered in the S.E. part of the town a little to the S. of the E. gate. It was found face-down over a rough cist or stone-lined grave which contained bones and broken 'urns'. The slab, which is broken, is from a monumental tomb. It measures 110 cm. by 50 cm., and has a sunken panel inscribed: D[IS] M [ANIBUS]/ANICIUS SATURNINUS/STRATOR CO[N]S[ULARIS]/ M[ONUMENTUM] S[IBI] F[ECIT], i.e. Sacred to the departed spirits: Anicius Saturninus, strator to the governor, made this monument to himself. A strator consularis was in charge of the governor's horses, and could be sent to try out new mounts. The death of this strator, perhaps in office, has been taken to suggest the presence of studfarms in the region (R.G. Collingwood and R.P. Wright, Roman Inscriptions of Britain, 1 (1965), 75–6).

Among other discoveries from the interior of the town are those recorded by Bridges and Morton in the early 18th century (Bridges, op. cit.; Morton, op. cit.). There were 'two plain oblong quadrangular stone pillars about 4 ft. long and almost 2 ft. in width', perhaps altars. These were found on the S. side of the town. Fragments of a tessellated pavement and brick 'have been ploughed up' as well as many coins.

A number of Iron Age coins are also recorded as 'from Irchester' including two of Cunobelinus, apparently from the interior of the town, found before 1898 (Brit. Num. J., 9 (1927–8), 251; 21 (1931–3), 3; J. Evans, Coins of the Ancient Britons, Supplement, (1890), 568; S.S. Frere (ed.), Problems of the Iron Age in Southern Britain, (1958), 223). Another, of Tasciovanus, said to be from Irchester, probably came from Duston, W. of Northampton (Frere, op. cit.).

In recent years large quantities of local pottery as well as considerable amounts of stone rubble and tiles have been found on the surface. The quality of these finds suggests that there are many more stone buildings which are not visible on air photographs. A number of coins, mostly of 4th-century date, have also been found (BNFAS, 5 (1971), 19).

Extra-Mural Area

Roman material from the extra-mural settlement of Irchester has been noted over a wide area S. and E. of the town (Fig. 12). Little has been found to the W.; the large ironstone quarries to the S.W. may have destroyed any occupation on that side. The principal discoveries made in the extra-mural area are as follows:

Cemetery (SP 921671), found in 1873 during ironstone-quarrying. Between 300 and 400 skeletons were discovered, as well as three stone coffins and one of lead. Many of the graves were lined and covered with rough limestone slabs (Ass. Arch. Soc. Reps., 13 (1875), 88–116).

Cemetery and Settlement (SP 921670), found during ironstone-mining in 1927 and possibly a continuation of the above. Finds included a Roman cemetery with some burials in stone coffins, stone-lined wells, pottery and unspecified ornaments (JRS, 17 (1927), 201).

Settlement (SP 920669), found during excavations by Baker in 1878–9. Unspecified Roman finds, a drain, at least two wells and stone foundations were discovered. This area lies immediately E. of the remains of the medieval settlement of Chester (8) and some of the finds may be connected with the latter.

Burials and Settlement (around SP 915666 and 918666). 'Many skeletons and numerous small objects' were noted during the 1926 excavations across the E. and W. sides of the town. Some of this material probably came from outside the ramparts (JRS, 16 (1926), 223).

Iron Age and Roman Settlement (SP 91656641 – 91876653), found in 1963 during excavations for a new road alignment immediately S. of the town. Remains of all periods from the early Iron Age to late Roman were discovered. A single pit containing early Iron Age pottery was found, together with a ditched enclosure with an internal wall, dated to the Iron Age B period. The enclosure had an entrance to the E. and its interior was full of pits, some containing animal bones. The late Iron Age was represented by pottery and animal bones as well as by three inhumations. Roman finds included four separate areas of stone buildings, all very fragmentary and ranging in date from the early 2nd to late 4th century, various ditches and part of a kiln, perhaps of 2nd-century date. Other finds included animal bones, brooches, coins, pins, bone tools, tiles and at least seven burials dated to the 3rd century (Arch. J., 124 (1967), 65–128). Air photographs of the area, taken before the road works started, show some of these features, as well as at least three other enclosures and a number of ditches.

'Tumulus' (SP 921665), S.E. of the town on the side of the A 45 road. It is said that there was once a mound here, but no trace remains (OS Record Cards).

Hoard of Bronze Bowls (SP 921671), found in 1874 during ironstone-mining. The hoard consists of eight bronze vessels found stacked inside an iron-bound bronze tub. There are five bowls, one ladle and two strainers. The whole group is dated to the late 4th century (NM; J. Northants. Mus. and Art. Gall., 4 (1969), 5–39).

Coin Hoard (SP 91866694), found during road works in 1963. A Roman pot contained approximately 42,000 silver-washed copper antoniniani of the mid to late 3rd century (NM; Arch. J., op. cit., 92).

Coin Hoard (?) (SP 924669). Writing in about 1720 Bridges recorded that 'in an orchard of . . . [Chester] House were lately found 45 brass coins in an urn with a ring and chain hanging on it' (J. Bridges, Hist of Northants., II (1791), 181).

Roman Roads

The town of Irchester was the meeting place of two and perhaps three roads. The details of these are fully described in the Appendix but information relating to their form in the area of Irchester is summarised here.

Road 170, Dungee Corner to Irchester approached the town from the S. and entered it through the S. gate to join the axial street. No trace of its line is visible to the N. of Irchester village; apart from a small area S. of the Roman town the land has been quarried away by ironstone-mining. However in the field N. of the iron-stone quarry and immediately S. of the town (SP 91756642), now occupied by the realigned A 45, air photographs (CUAP, DA 14) show a soil mark extending N.N.W. towards the S. gate. No trace of this was noted during the excavations of 1962–3 (Arch. J., 124 (1967), 65–78) but as these took place after surface stripping for the modern road-works the Roman road may already have been destroyed.

Road 570, Durobrivae to Irchester (?) approached the town from the E., and entered it through the E. gate. Although no trace of it remains on the ground or is visible on air photographs, the excavations of 1878–9 are said to have discovered a road of gravel and pebbles laid on limestone, running E. from the E. gate and apparently traced for a distance of some 300 m. (SP 91856680–91246694). However, according to the excavator's plan, the three places where the road was found are not in a straight line, so that either the original road changed direction markedly, or the excavator was mistaken in assuming that each piece was part of the same road.

Road, Duston to Irchester probably approached the town from the W. and entered it through the W. gate. No trace of such a road is known anywhere between Welling borough and Irchester although it is likely that one existed.

Road, Kettering to Irchester probably ran N.N.W. from the E. gate of the Roman town towards Kettering. A large agger, 0.5 m. high and 10 m. wide, is traceable crossing the floodplain of the R. Nene (SP 91686753– 91776709).

(Additional Bibliography: Plans, Sections, Photographs, Drawings and Notes, Dryden Collection, Central Library, Northampton; CUAP, AFX 3, BCJ 84–5, DA 9–14, YP 4–11, ZE 1–5; air photographs in NMR.)

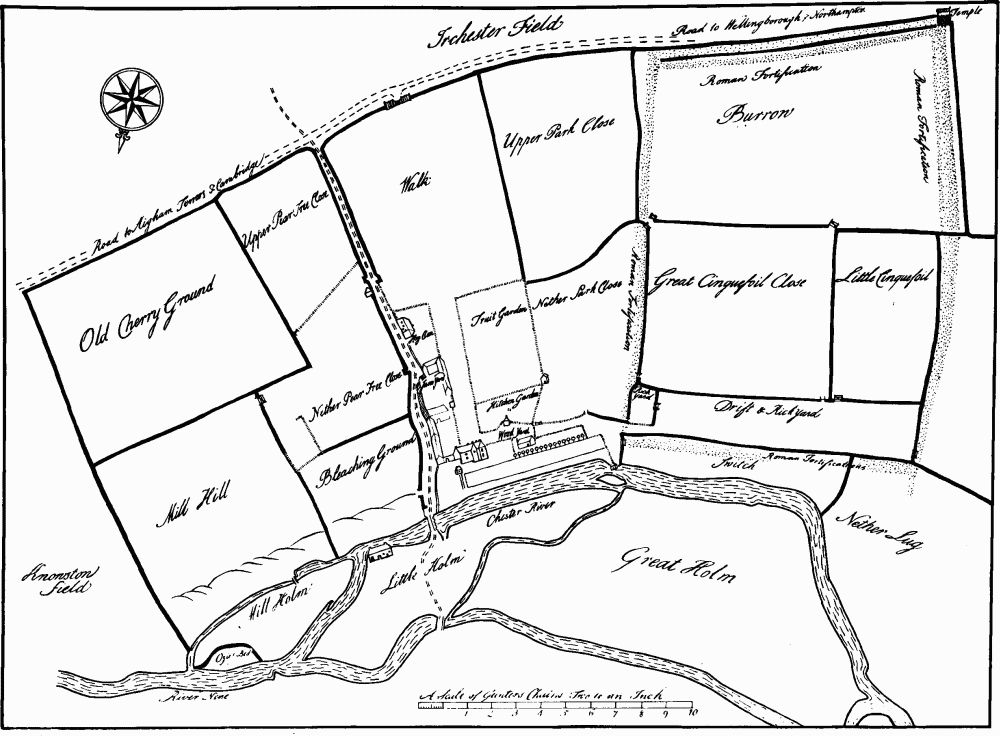

Fig. 90 Irchester (8) Settlement remains of Chester-on-the-Water

Medieval and Later

Two Anglo-Saxon saucer brooches, said to have been found in Irchester (Archaeologia, 63 (1912), 200; Meaney, Gazetteer, 190), in fact came from the large cemetery at Marston St. Lawrence, in the S.W. of the county (J. Northants. Mus. and Art Gall., 6 (1969), 49).

a(8) Settlement Remains (SP 920669; Figs. 90, 91 and 93; Plate 16), formerly part of the hamlet of Chester-on-the-Water, lie immediately E. of Chester House and 250 m. E. of the Roman Town (7), on sand at 52 m. above OD. Although the existence of the hamlet in late medieval times is well documented, little is known of its earlier history, and almost nothing of its population. It is not mentioned in Domesday Book or in medieval tax returns and the earliest reference to it is in 1236. In the Inquisitions Post Mortem of 1309 twenty-four villeins, tenants and cottars are recorded on the manor but it is not certain that all these people lived at Chester itself. In 1517 the Wolsey Commission reported that William Coope, the then lord, had demolished six messuages in 1498, thereby rendering 36 people idle. However another document indicates that there were still five messuages inhabited in the village at that time. In the early 17th century six houses are recorded in Chester and these still existed in the late 17th century. They still remain but in a ruined state, having been abandoned and incorporated into the farm before 1720 when Bridges described Chester as a 'manor with one house . . . anciently an hamlet of four or five houses'. A map of 1756 (NRO) shows that a small country estate had been created by this time, with the present Chester House and a formal garden approached by a wide drive, and since that date there have been few alterations.

The surviving earthworks are slight and much mutilated by later farm buildings, recent rubbish dumps and the abandoned cutting of an ironstone tramway. Two roughly parallel scarps, running S.W.—N.E. may represent former croft boundaries and the slight rectangular depressions associated with them may be sites of buildings. The surviving buildings to the W., now part of the farm, consist of a range of five ruined houses, all probably 17th-century; one carries a date stone of 1690.

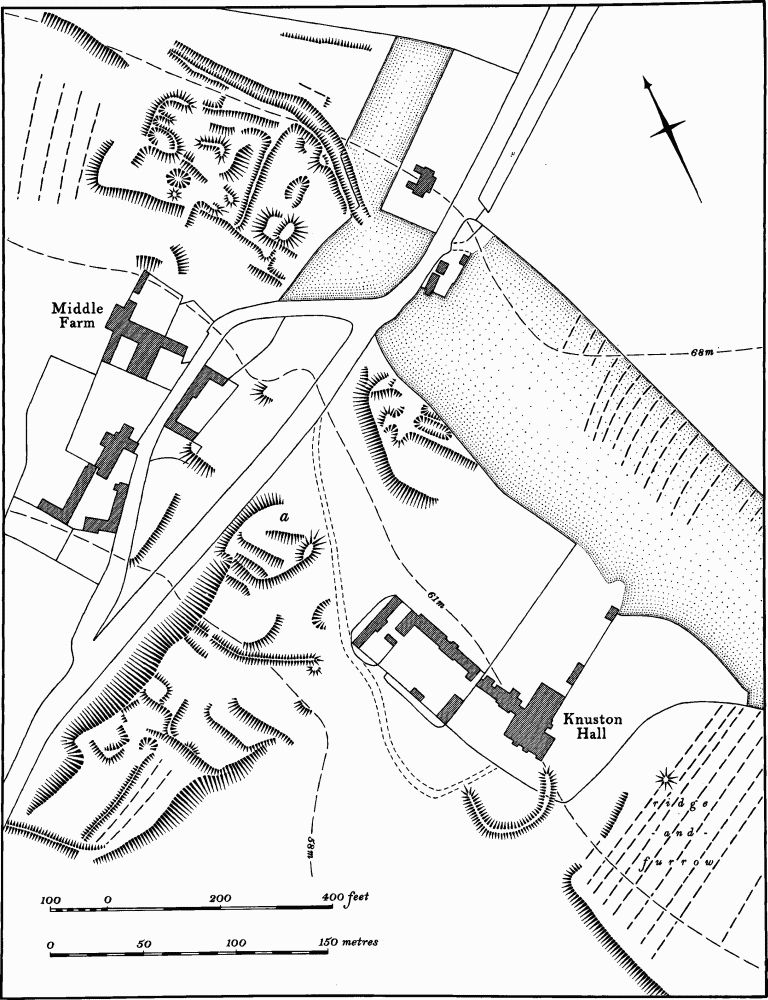

a(9) Deserted Village of Knuston (SP 938662; Figs. 92 and 93; Plate 22), lies immediately N. and N.W. of Knuston Hall, on limestone and clay at 60 m. above OD.

The village is first mentioned in Domesday Book with a recorded population of 12. It is impossible to determine the size of the village before the early 18th century, because the village was a dependent chapelry of Irchester and thus all national taxation records include both places. Moreover as Knuston was divided into two separate manors there are no total population statistics in the manorial records. However 33 tenants are listed under the larger manor just prior to 1345. There is some evidence of enclosure and depopulation at Knuston in the early 16th century, and by 1720 Bridges records twenty families in the village. Inadequate as these figures are they suggest a considerable decrease in population in late medieval or early post-medieval times. A map of Knuston, c. 1769 (NRO), probably made for purposes of enclosure, shows five farms and about a dozen cottages arranged around a group of lanes N. of the hall. By this time the hall had acquired a small formal park around it. In 1775 the Knuston estate was sold to Benjamin Kidney who mortgaged it in 1780 and 1786 and then sold it in 1791 to Joseph Culstone. The documents which record these transactions show clearly the final removal of the hamlet of Knuston and its replacement by parkland. By 1786 at least two farms and four cottages had been bought by the lord of the manor and were without tenants, and at least one other farm was used only as a barn and dove-house. By 1791 (map in NRO) all but one of the buildings S. of the existing road had been demolished and the land emparked (Northants. P. and P., 5 (1975), 188–92).

Fig. 91 Irchester (8) Settlement remains of Chester-on-the-Water (drawing based on a plan of 1756)

The surviving earthworks are slight and have been disturbed by a temporary hospital erected during the Second World War, and by the straightening of the Irchester-Rushden Road in 1967 which removed the hollow-way shown as a through-road on the map of 1769. S. of the present road is a series of disturbed earthworks, most of which are the remains of houses and gardens already abandoned before the 18th century. Those in the area N.W. of the hall ('a' on Fig. 92) lie on the site of buildings still standing in 1769. N.E. of Middle Farm are further low earthworks, also abandoned before the 18th century. Pottery discovered during the road construction in 1967 included one Roman sherd, one possible Saxon sherd, some 12th to 13th-century St. Neots ware and various 13th to 14th-century wares of Lyveden and Potterspury types. Considerable amounts of post-medieval pottery were also noted.

Immediately S. of the hall is a low semi-circular bank, only 15 cm. high. This marks the boundary of the circular forecourt of the hall shown on the 18th-century map.

a(10) Settlement Remains (SP 925660), formerly part of Irchester village, near the church, on lime-stone at 70 m. above OD. Pipeline trenches in the area have revealed medieval pottery, including St. Neots and Lyveden wares, indicating former settlement (BNFAS, 7 (1972), 44).

Fig. 92 Irchester (9) Deserted village of Knuston

a(11) Site of Manor House (SP 928656), immediately E. of High Street, Irchester, on limestone at 68 m. above OD. The area was once covered by low earthworks which were completely destroyed by building development in 1967 (CUAP, AKP–83; RAF VAP 541/ 611, 4033–4). During the development excavations took place and a large number of features and finds were discovered. In addition to some Roman pottery these included the walls of a number of buildings, cobbled yards, pits, ditches and post-holes, Saxon and medieval pottery of St. Neots, Stamford and Lyveden types, an iron-working site, roof tiles, horse-shoes, iron arrowheads, a bone-handled knife and lead glazing-bars. A silver penny of William, Count of Namur (1337–91), was also discovered. Worked flints, including an arrowhead were noted (BNFAS, 2 (1967), 25; 5 (1971), 30; OS Record Cards; inf. P. Foster). Further to the N., beyond Station Road (SP 928658), a number of closes, bounded by low banks and much disturbed by later quarrying, still survive on either side of a shallow valley. These may be associated with the finds described above.

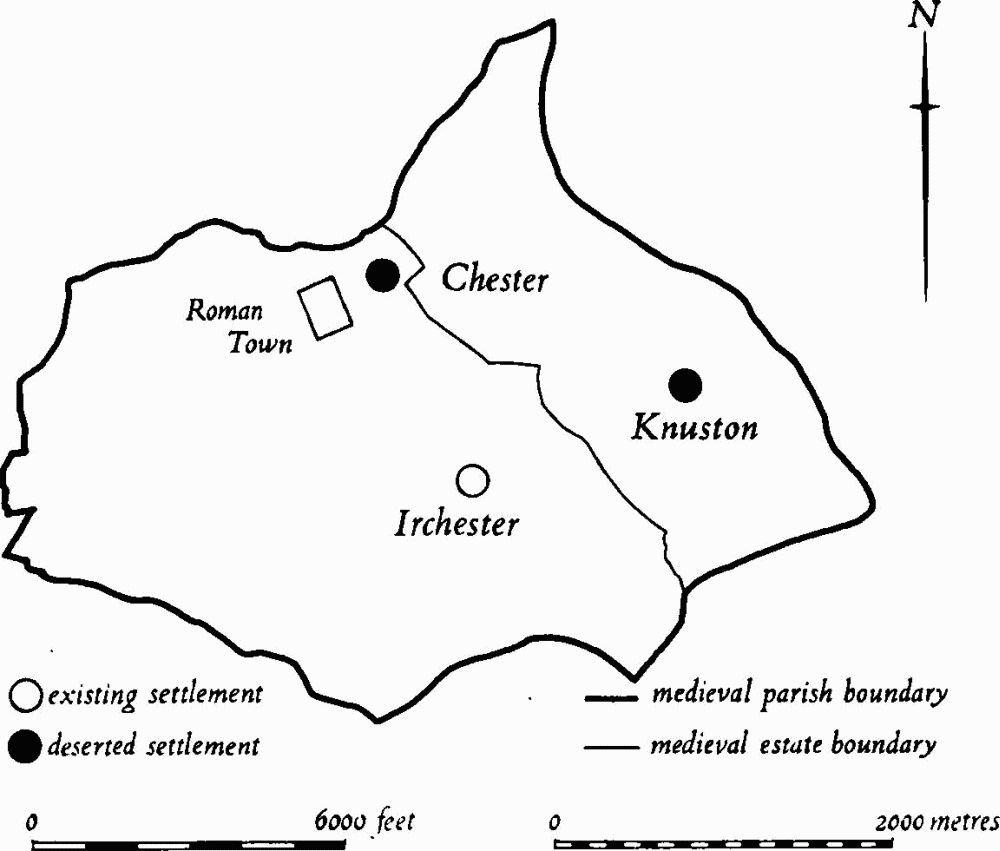

Fig. 93 Irchester Medieval settlements and estates

(12) Cultivation Remains. The common fields of the old parish of Irchester were enclosed in 1773. Shortly before that date there were apparently three fields known as Bridge, Middle Dale and Mill Bunch Fields (Northampton Central Library, Irchester Cuttings). The common fields of the township of Knuston were enclosed in 1769 (VCH Northants., IV (1937), 5; Northants. P. and P., 5 (1975), 191).

Very little of the ridge-and-furrow of these fields remains on the ground or is traceable from air photographs. There are fragments N. and S. of the village of Irchester and S. of Irchester Grange (SP 929649), and a group of interlocked furlongs around Knuston Lodge (SP 944657). Within the land of the old lordship of Chester one block remains, E. of Chester House (SP 919669). Headlands survive S. of Irchester village, running S. for 300 m. from SP 921653 and 922653, and N. of Knuston Hall running N.W. from SP 937664 and 937668 (RAF VAP F22 543/RAF/943, 0101–8, 0031–9; F21 543/RAF/943, 0031–7; 540/474, 3042– 3; 541/611, 4041–3, 4033–7; CPE/UK/2546, 4195–6; F21 540/RAF/1312, 0275–83; F22 540/RAF/1312, 0277–81).