An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in Herefordshire, Volume 3, North West. Originally published by His Majesty's Stationery Office, London, 1934.

This free content was digitised by double rekeying. All rights reserved.

'Sectional Preface', in An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in Herefordshire, Volume 3, North West(London, 1934), British History Online https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/rchme/heref/vol3/xxvii-xxxviii [accessed 26 April 2025].

'Sectional Preface', in An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in Herefordshire, Volume 3, North West(London, 1934), British History Online, accessed April 26, 2025, https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/rchme/heref/vol3/xxvii-xxxviii.

"Sectional Preface". An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in Herefordshire, Volume 3, North West. (London, 1934), British History Online. Web. 26 April 2025. https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/rchme/heref/vol3/xxvii-xxxviii.

In this section

HEREFORDSHIRE Vol. III

Sectional Preface

(i) Earthworks, etc., Pre-historic and Later.

North-Western Herefordshire is as prolific in hill-forts as the eastern area of the county, treated in the last volume. The forts, furthermore, are of much the same character and nearly all of them may be assigned with confidence to the Early Iron Age, though no excavation has been undertaken in any one of them. The most important examples are Risbury (Humber), Ivington (Leominster Out), Wapley (Staunton-on-Arrow), Bach (Kimbolton), Coxall Knoll (Buckton and Coxall), Croft Ambrey and Pyon Wood (Aymestrey). The general questions concerning these camps are discussed on p. xliii.

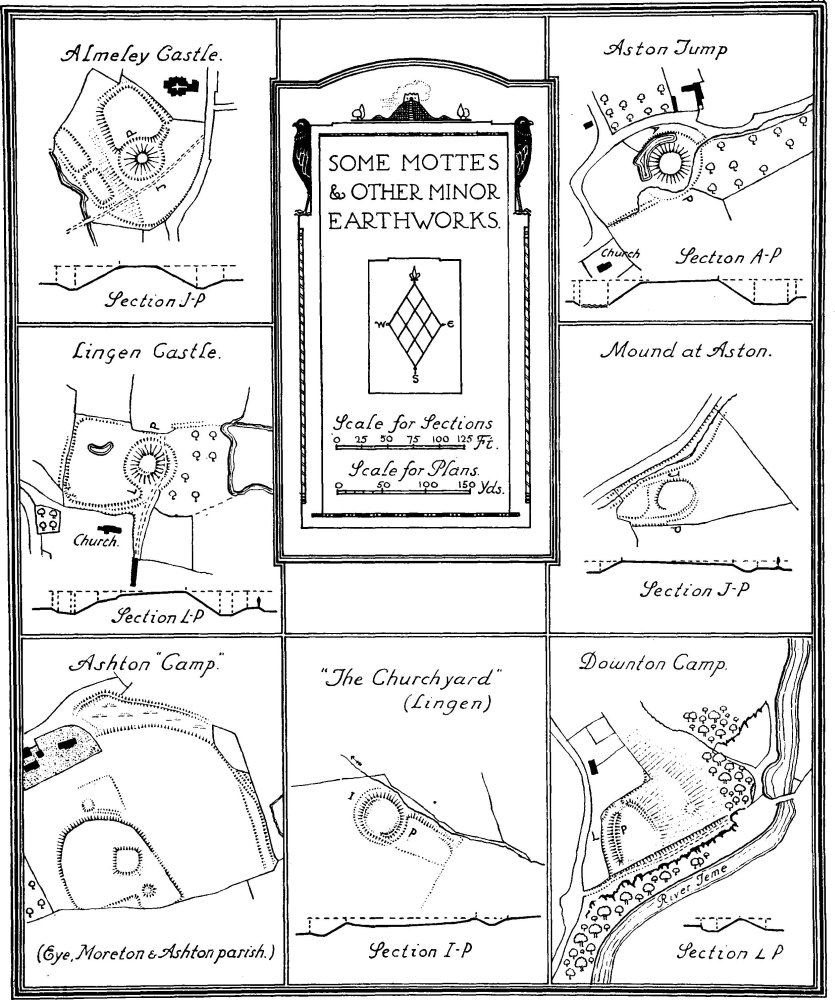

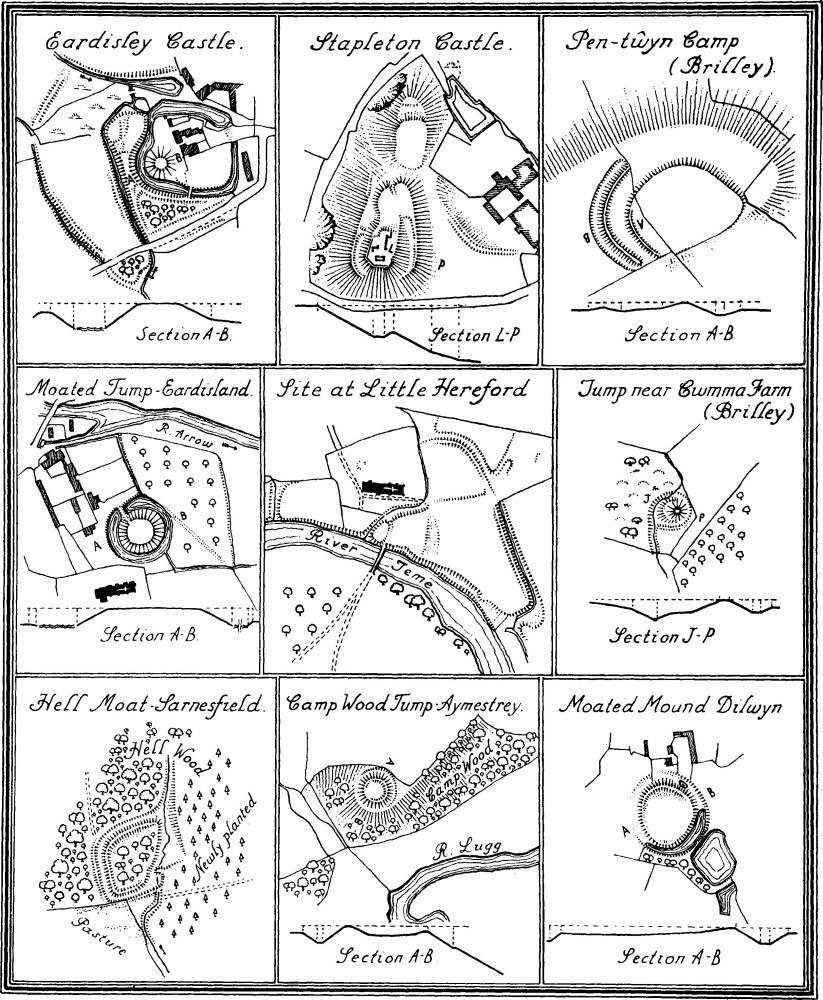

The mediæval earthworks include a fine series of mount and bailey castles, of which Richard's Castle, Huntington, Lingen, Almeley, Eardisley and Turret Castle, Huntington, are perhaps the most notable. There are also a number of isolated tumps, of which the example at Aston may be mentioned.

Offa's Dyke.

The outstanding historical earthwork of this part of the county is Offa's Dyke.

The date and purpose of this travelling earthwork have recently been the subject of an exhaustive investigation and survey by Dr. Cyril Fox and Mr. D. W. Phillips (Arch. Cambrensis, six reports, 1926–1931). As a result of this investigation it may now be taken as proved that the earthwork, as implied by its name, was a delimitation of the frontier between Wales and Mercia, constructed in all probability by the greatest of the Mercian Kings—Offa (757–796).

Previous to this investigation it was generally considered that the intermittent occurrence of the dyke between the Welsh border and the Wye was due either to its subsequent destruction in great part, or to its never having been completed. It now appears, however, that "we have the whole construction in this area as Offa made it," as is evidenced by the distribution of the sectors in relation to the geography and by the survival in three of them, undamaged, of the original terminals (Arch. Camb. 1931, p. 48). This intermittency is accounted for by the fact that a great part of this area, in the 8th century, was thickly wooded and that it was only necessary to defend those valleys which had been cleared and settled by the Saxons or such roads or trackways passing across the boundary, as were then in use. Thus it was only found necessary to construct the dyke for a little more than a quarter of the distance of 13 miles between Rushock Hill (Kington Rural) and the Wye (Bridge Sollers). The longest gap in this line is that between the valley of the Curl Brook and Burton Hill (about 6 m.), and here the boundary seems to have followed the line of the watershed and not to have been intersected by either a watercourse or a trackway. Through the remaining part of Herefordshire the Wye seems to have formed the boundary, for though there are lengths of earthwork at Hereford—the Row Ditches —and another in Foy parish, these, in the opinion of Dr. Fox, can hardly have formed part of Offa's boundary.

Some Mottes & Other Minor Earthworks.

The Course of the Dyke in Herefordshire.

Offa's Dyke enters the county from Radnorshire at Riddings Brook in Lower Harpton parish. Along the flat the bank is broad and its scarp measures 17 feet with a W. ditch largely silted up. Interrupted by a marsh for a few yards it then changes direction and ascends straight up the flank of Herrock Hill. Near the crest, at a height of 1,100–1,200 feet, it is carried along the hill-face and the col connecting it with Rushock Hill. On the hillside the dyke is a rounded bank (26 feet broad) with a well-marked W. ditch, but along the hill-face it varies in form and in places becomes a mere berm or shelf. Passing up the slope of Rushock Hill the dyke is a considerable bank, apparently with an upper ditch only; on the hill is a re-entrant angle forming a right-angle towards Mercia, and with a ditch on the inner side. On Herrock Hill the dyke passes through Knill parish, while on Rushock Hill it forms the boundary between Knill and Kington Rural, passing entirely into Kington Rural at the yew trees called the Three Shepherds. From this point it continues towards Eywood Brook, measuring about 13 feet on the scarp and with a S. ditch; at a distance of 320 yards the dyke becomes small and irregular and the ditch shifts from S. to N. After another 120 yards the dyke again becomes well defined with a well-cut N. ditch. It passes through Kennel Wood as a rounded bank and in the meadow beyond the levelled dyke can be traced nearly to the parish boundary. The dyke in the Eywood valley would appear to have been constructed by another gang to that which worked on Rushock Hill, the change in technique taking place at the end of the plateau. When it next appears, in Titley parish to the N. of Berry's Wood, the dyke has resumed its N. and S. course; here it is a flattened bank 50 feet wide with a broad W. ditch. To the S. of the river Arrow, in Lyonshall parish, the dyke reappears in well-defined form and is cut by the railway line. The next stretch of the dyke begins at the Lyonshall-Kington road, W. of the village, and extends, with minor breaks, for a distance of rather over a mile to near Holme Marsh. The N. part consists of a high rounded bank with a W. ditch, 12–13 feet broad, the whole work being 50–60 feet broad. There are some indications that at the extreme N. end the dyke turned at an angle, its end abutting on the modern road some 250 feet to the N.E. As it approaches the drive, Lyonshall Park, it changes its character, the bank becoming higher and the ditch narrower. Farther on there is a fine piece of bank remaining, but immediately beyond a trackway passes on to the levelled bank, and runs nearly as far as the railway. In this stretch a streamlet has been diverted into the ditch of the dyke for several hundred yards. Beyond the railway the partly levelled bank is clearly visible, with the ditch on the W. side. On the S. side of the Curl Brook the dyke continues, finishing abruptly at the edge of the plateau; here it is on a very large scale, the scarp still measuring 21 feet 7 inches although the ditch has been obliterated.

No trace of the dyke is to be seen for a distance of some 6 miles from this point. It reappears in Yazor parish, about 250 yards N. of the road, near Claypits hamlet, as a large broad bank with traces of a W. ditch. After a short interval it reappears S. of the road and though interrupted by the railway, continues as far as the Yazor Brook, becoming gradually smaller as it approaches the stream. Beyond the brook (Mansell Gamage parish) there is no trace of the dyke up to a point on the S. side of Bowmore Wood. Here there is a very large bank extending up-hill for 220 yards; the W. ditch has been largely ploughed in but can be traced a little farther than the bank. There is no trace of the dyke on the wooded top of Garnons Hill, but it appears again a little to the N. of the Roman road, and from this point to the river Wye it forms the boundary of the parishes of Byford on the W. and Bishopstone and Bridge Sollers on the E. At the start the dyke is much damaged, but as it approaches the Roman road (at The Steps) it becomes larger, higher and continuous. Farther S. it has been partly ploughed down; S. of the main road it fades out on a bluff above the Wye. The W. ditch can be traced along this sector and at the S. end becomes a drainage channel. (See the detailed survey in Arch. Camb., 1930, pp. 44–47 and 1931, pp. 7–20, and general survey of the Herefordshire sector, ibid., 1931, pp. 47–58.)

Offa's Dyke (and Rowe Ditch) in N. Herefordshire

(ii) Roman Remains.

The Roman sites, included in the present volume, are three in number. The station at Leintwardine was defended by a bank if not by a wall; the site at Blackwardine (Stoke Prior) is of indeterminate nature, while the house at Bishopstone must have been a building of some pretensions. A general consideration of these and the other Roman remains in the county will be found on p. xlix.

(iii) Ecclesiastical and Secular Architecture.

Building Materials: Stone, Brick, etc.

The materials used in the North-Western part of Herefordshire do not differ appreciably from those employed elsewhere in the county. Red sandstone is the staple building-stone, except on the Radnorshire border where a certain amount of Silurian limestone is used. The great majority of the secular buildings are timber-framed, except on the Welsh border where stone becomes more general. Brick is little used before the latter part of the 17th century.

Ecclesiastical Buildings.

There would appear to be no evidence of the survival of structural or decorative remains of the pre-Conquest period in N.W. Herefordshire, with the possible but improbable exception of the tower at Pudleston. Of the early post-Conquest period the most remarkable example is the N. wall at Wigmore, which is built entirely in herring-bone masonry. There is an early doorway and sporadic herring-bone work at Hatfield. The finest example of 12th-century work is the monastic nave at Leominster Priory, a three-storeyed building, begun on a highly unusual plan, which was abandoned before the building of the triforium. The rather later W. tower has elaborate carved decoration of the local type noted in the previous volumes and exemplified at Kilpeck, Rowlstone, Castle Frome and elsewhere. The same decoration is to be seen in the district under review in the reconstructed arches and the font at Shobdon and on the font at Eardisley. The two doorways at Shobdon have carved tympana and there is an elaborate and well-executed tympanum of another type at Aston. The rude tympanum at Byton and the carved lintel at Willersley may also be mentioned in this connection. Middleton on the Hill has a largely complete 12th-century church of simple character, and there is late 12th-century detail at King's Pyon and in the form of re-used stones from Wigmore Abbey.

The work of the succeeding century is poorly represented, but there is some good 13th-century detail at Byford, and the chancel at Kington was a large structure lit by a series of lancetwindows, many of which have been destroyed or blocked. The 13th-century chancel and tower at Dilwyn are of interest from their early character, perhaps due in the chancel to a re-use of earlier material.

Several important works of the 14th century survive, including the greater part of the large church at Pembridge, the extensive additions to the nave of Leominster and much of the church at Kingsland. The handsome and lofty tower and spire at Weobley are also of this period as are the towers of Leintwardine and Kinnersley. The old church at Richard's Castle has interesting examples of 14th-century window-tracery.

Very little work of the 15th century is of more than very ordinary interest, except the reconstructed W. tower at Leominster.

In this district, as elsewhere in the county, there is observable a local fashion for building detached bell-towers. Pembridge, Richard's Castle and Yarpole provide examples of this, and the towers at Weobley, and Kington, though actually attached to the building, indicate the same tendency.

The so-called Volka Chapel at Kingsland deserves mention as a highly unusual feature both in position and treatment.

Post-Reformation church-building is exemplified in the churches of Brampton Bryan, re-built after 1643, Monnington-on-Wye, re-built in 1679 with most of its original fittings, and Norton Canon, re-built in 1706. The latter is remarkable for the re-use of mediæval features. Though after the terminal date of the Commission's reference, mention may also be made of the church at Whitney, re-built in 1740 and that at Shobdon, re-built in 1753, with 'Gothic' fittings of that age. Brampton Bryan has a remarkable 17th-century hammer-beam roof, and to the same period belongs the chancel-roof at Bishopstone. The 17th-century lych-gate at Monnington-on-Wye also deserves mention.

Of mediæval roofs, the most remarkable is the combined roof over the two aisles at Stretford, while the nave roof at Almeley has an early 16th-century boarded and painted soffit to the eastern portion.

At Almeley there is a Quaker Meeting House which seems to have been built about 1672. It is a simple timber-framed structure hardly differing externally from the cottages of the district.

Monastic and Collegiate Buildings.

The most important surviving example of monastic work in the district is the nave of Leominster Priory, a cell of the Benedictine Abbey of Reading. Excavations have revealed the plan of the destroyed choir and transept; a portion of the domestic buildings and a chapel within the precinct are still standing. Of the important Abbey of Wigmore (Adforton parish), a house of the Austin Canons of St. Victor of Paris, some fragments of the church, a part of the domestic buildings and a gatehouse still exist. The general lines of the church were ascertained by excavation in 1906–7. Apart from some small remains of the priory of Austin Nuns at Limebrook, and the re-built church at Monkland, which probably served as the chapel of the alien priory there, a cell to Conches Abbey in Normandy, there are no remains of the other religious houses of the district. These were the alien priories of Kinsham and Titley and the Augustinian priory of Wormsley.

Two ranges of 17th-century almshouses remain at Pembridge and there are three school-buildings of note. The small building at Weobley survives but little altered, but the schoolhouse at Kington, built by John Abel c. 1622, has been extensively altered and modernised. Lucton School, built in 1708, is still largely in its original state.

Secular Buildings.

The N.W. portion of the county has preserved an even larger proportion of mediæval houses than was the case in the parts already dealt with. As elsewhere, the series begins with the primitive type of building based on the crutch-truss, a type which can seldom (as at Middleton House, Dilwyn) be even approximately dated. The more developed type, which is usual in 14th and early 15th-century timber-building, is extensively represented. It is distinguished by the bold foiling of the timbers above the tie-beam or the collar and seems to have lasted well on into the 15th century. Several examples are to be seen in Weobley and Pembridge, and others at Swanstone Court, Dilwyn; The Marsh, Eyton; Staick House, Eardisland; Black Hall, Kingsland; Eaton Hall, Leominster Out; and Chapel Farm, Wigmore. At Yew Tree Cottage, Dilwyn, there are remains of a spere-truss in conjunction with a crutch-roof, and another spere-truss survives at Eaton Hall.

Timber-framed houses of later mediæval character may be noted at Almeley Manor; Upper House, Eardisley; Hergest Court, Kington Rural; Must Mill, Kingsland; and Eyton Court.

The larger type of mediæval stone-built house is represented by Hampton Court and Croft Castle. Both are semi-fortified but have been much altered and re-built. The former, however, retains its great gatehouse and chapel and the latter its four angle-turrets.

Elizabethan and Jacobean building is well represented both by timber-framed and stone or brick-built houses. Of the former the Ley, Weobley; Luntley Court, Dilwyn; Butt House, King's Pyon; Rodd Court; New Inn, Pembridge; and Upton Court, Little Hereford, may be mentioned. The stone or brick-built houses include Kinnersley Castle; Court Farm, Hatfield; Byford Court; Gatley Park, Aymestrey; and Wharton Court, Leominster Out. Nun Upton, Brimfield, is partly timber-framed and partly of brick. Symmetrically designed Renaissance houses of late 17th and early 18th-century date are to be seen at Eye Manor (1680), Middleton on the Hill (1692), Court of Noke, Pembridge, Kingsland Rectory, and Shobdon Court (now demolished).

Butt House, King's Pyon, has an interesting timber-framed gatehouse dated 1632.

Numerous pigeon-houses have been noted, the circular stone type, represented at Stockton Bury, Kimbolton, and Court House, Richard's Castle, being probably mediæval. The later examples are generally timber-framed, giving place to brick towards the close of the 17th century. The structures at Broadwood Hall, Leominster Out, and Luntley Court, Dilwyn, are dated respectively 1652 and 1673.

Castle building is poorly represented, only Brampton Bryan and Wigmore retaining remains of any extent. At the former place the ruins are those of a 14th-century gatehouse with a fragment of the great hall. At Wigmore most of the remains above ground are also of the 14th century, and though much shattered are still extensive. Small remains survive at Lyonshall of a cylindrical keep of the 13th century with a curtain carried round it, while at Huntington and Richard's Castle only disconnected masses of rubble survive.

The timber market-hall of Leominster, a work of John Abel erected in 1633, has been reconstructed as a house. It is a handsome example of the ornate timber-work of the age. Only the lower part of the late mediæval market-hall at Pembridge is now standing.

The schedule includes bridges at Eaton, Leominster Out, Ford, and Stapleton, and minor structures at Eaton Hall and Risbury. With the exception of the last named, which is of uncertain date, they all belong to the 17th century.

Condition.

The general condition of both ecclesiastical and secular monuments is good, but as in the last volume attention must be called to two derelict or ruined churches at Downton on the Rock and Yazor. The former is a building of some interest which has been suffered to lapse into entire ruin. The ruins of Wigmore Castle are much overgrown and are well-deserving of careful excavation and preservation.

Fittings.

Bells: There are some twenty-seven mediæval bells in the area under review. Of these six are of the long-waisted form without inscriptions, which may be ascribed to the 13th or early 14th-century period: they are at Elton (1st), Hatfield (two bells), Leinthall Starkes (2nd), Shobdon (Sanctus), and Wormsley (1st). Four bells are probably of the 14th century, at Lingen (two bells, one inscribed and the other blank), Monnington-on-Wye (3rd) and Sarnesfield (4th), the last probably of foreign workmanship.

Fifteen others—all bearing inscriptions and some of them founders' marks—are of the 15th century. Of these six are identified with the Worcester Foundry by the King and Queen head-stops, used in the early years of the century. They are at Kimbolton (5th), Laysters (3rd), Letton (3rd), Middleton on the Hill (2nd and 3rd), and Stoke Prior (4th). Four others with crowned capital letters have been identified with the later output from Worcester and two, with crowns between the words of the inscriptions, with the foundry of Robert Hendley of Gloucester. The former are at Laysters (1st), Middleton (1st), and Pudleston (two), and the latter at Letton (1st) and Yarpole (1st).

Three foundries, not yet identified, are represented at Brobury, Leominster (Sanctus), and Yazor (dismounted and cracked). The second, with a black-letter inscription, is probably late, the other two early to mid 15th-century. Two at Brimfield (3rd) and Richard's Castle (2nd) may be of early 16th-century date.

With regard to the inscriptions, with the exception of that at Leominster all are of Lombardic lettering and are mostly the usual invocations or prayers in Latin.

The most unusual is the bell at Sarnesfield in which the letters of the inscription IESV SALVA ME are shown as though made up of pairs of cords or tendrils, with loops and scrolls, more or less in the form of the usual Gothic capitals: this is quite unlike any other bell in the county and is probably not English.

Of the other dedications there are nine to St. Mary, one to St. Mary Magdalen, four to St. John, two to St. Peter, two to St. Gabriel, and one to St. Margaret.

Among the later—post-Reformation—bells only two are from London, those by Robert Oldfield at King's Pyon (4th) 1606, and Weobley (3rd) 1605.

The local founder, John Finch of Hereford, is represented by four from 1639 at Pudleston to 1663 at Bridge Sollers. Isaac Hadley of Leominster is also responsible for four of the early 18th-century bells.

The foundry of John Martin of Worcester has thirteen bells from 1618 at Mansell Lacy to 1691 at Aston: the former date seems to be quite clear on the bell but may have been intended for 1658.

John Green of Worcester has three of 1605, 1628, and 1634. Six bells can be identified with the Clibury Foundry dating from 1610 to 1674, and two with John Palmer of Gloucester, both of 1671. Another of 1671 at Huntington bears the initials of I. G. who was Palmer's foreman. Single examples exist by Godwin Baker of Worcester, 1615, at Monnington; H. Farmer of Gloucester, Kinnersley (2nd), 1618; Richard Dankes of Worcester, Little Hereford, 1633; W. B., 1684, at Eyton; H. Williams of Brecon, 1693, at Mansell Gamage; and, finally, there are at least two of the many bells from the Rudhall foundry of Gloucester which ante-date the year 1714; one at Docklow (1701) and one at Eardisley (1708).

Brasses: The brasses of the district are of little importance. The only figure is the bust of a priest of 1421 at Kinnersley. There are inscriptions at Eardisley, Letton, Orleton, Pembridge, and Knill.

Chairs: There are 17th-century chairs with carved backs at Brimfield, Little Hereford, Eardisland, and Kinnersley. The two chairs at Leominster incorporate carved figure-panels of foreign workmanship.

Churchyard Crosses: The best of the churchyard crosses of the district are those at Aymestrey and Knill, the former retains its shaft and the latter the head also, with an unusual square sunk panel on the E. face. Others may be mentioned at Orleton and Wigmore. A number of the base-stones have the shallow niches commented on in previous volumes.

Coffin-lids: A considerable number of highly ornate coffin-lids survives, of which good examples may be seen at Brobury, Dilwyn, Mansell Gamage, Norton Canon, and Richard's Castle. Two lids at Sarnesfield retain their inscriptions and a third at Weobley is inscribed to Hugo Bissop and bears a mitre and crozier. If this be a pun on the name it is an unusual one for the 13th century.

Communion Tables: The best of this type of fitting is the late 16th-century table, with bulbous legs, at Letton. There are tables at Monnington-on-Wye and Weobley, dated 1679 and 1707 respectively.

Fonts: The earliest surviving fonts are presumably the group of rudely cut cup or tubshaped bowls, examples of which survive at Byton, Hatfield and Brilley. The earliest date presumably from late in the 11th or early in the 12th century, but the type continued into the following century. The best enriched 12th-century fonts are those at Eardisley, Shobdon and Orleton. The first of these is a fine example of the local school of carving perhaps centred at Leominster, and is paralleled by the similar font at Castle Frome described in Volume II. The Shobdon font is of the same school, but here the carving is confined to the stem. The cylindrical font at Orleton is coarsely carved with a series of figures of apostles under a continuous arcade. The hemispherical bowl with an enriched stem and base at Birley may also be mentioned. A bowl with curious ornament, perhaps of c. 1200, survives at Knill, but the best 13th-century font is the delicately carved example at Hope-under-Dinmore. Later fonts are of minor interest; a fair example of the 14th century is to be found at Weobley, and one of the 14th or 15th century at Dilwyn. There are post-Reformation fonts at Byford and Monnington-on-Wye, dated respectively 1638 and 1680.

Glass: Very little mediæval glass survives in the churches of the district. Some fragments of a Crucifixion at Ford, of the 13th century, are perhaps the earliest examples. The glass of Kingsland, though partly restored, comprises a number of figure-subjects, including an archbishop, scenes introducing the four archangels, a Coronation of the Virgin, and some heraldry, all of the 14th century. There is a panel of the same period, with censing angels, at Dilwyn, and some original tracery glass at Richard's Castle with a Coronation of the Virgin. A delicately executed spandrel with a head and oak-leaves, at Monkland, may also be mentioned. Early 15th-century glass of importance is that in the tracery of a window at Weobley with figures of Seraphim and tabernacle-work. There is some mediæval and later heraldry at Hampton Court.

Monuments: As in other parts of the county the funeral monuments of the district are both numerous and important. There are twenty-two mediæval recumbent effigies, of which eight are executed in alabaster and the rest in freestone. There are no certain examples of the 13th century, but the two pairs of figures at Stretford, the two pairs at Pembridge, the armed figures of a Mortimer and a Talbot at King's Pyon and Dilwyn, and others of less importance date from the 14th century. Of these the most interesting is the figure of a man in the robes of a Sergeant-at-Law at Pembridge. The 15th-century figures include the two monuments at Weobley and that at Kington. Both the armed figures at Weobley wear the collar of SS, and the figure of Thomas Vaughan, 1469, at Kington wears the collar of suns and roses. The fine tomb with the head-canopy and figures of saints at Croft commemorates Sir Richard Croft, 1509, and his wife, and there are two monuments with alabaster effigies of members of the Cornewall family at Eye, both of the first half of the 16th century.

A large number of more or less ornate 14th-century tomb-recesses without effigies survive, the best examples being at Almeley, Brobury, Dilwyn, Eardisland, Little Hereford, and Kingsland.

An incised slab with the figure of a lady at Little Hereford dates from c. 1340, and there are early 16th-century incised slabs with figures at Aymestrey and Hope-under-Dinmore. A slab with figures and canopy formerly inlaid in marble remains at Dilwyn.

The finest Renaissance monument is the handsome alabaster memorial of Francis Smalman, 1632, at Kinnersley, which is remarkable for the delicacy of its carved figures and enrichments. An altar-tomb of 1613 at Bishopstone has recumbent effigies. Of later monuments the most important is that with a standing figure of Col. Birch, 1691, at Weobley. There are also a number of well-designed 17th or early 18th-century tablets, of which the best are to be seen at Monnington-on-Wye (with a bust), Hatfield, Lucton, Mansell Lacy, Pembridge and Shobdon. Though outside the Commission's date, mention may be made of the elaborate Coningsby monument by Roubiliac at Hope-under-Dinmore.

An unusual series, for this part of the country, is provided by the cast-iron floor-slabs at Burrington and the single example at Brilley. All these date from the 17th century.

Overmantels: A certain number of late 16th and early 17th-century overmantels have been noted in the district, but none are of any great distinction. The best are those at Knill Court, Rodd Court and Upper Nash Farm at Rodd, and Titley Court.

Paintings: The survival of mediæval wall-paintings is very infrequent in the district, only two examples of any consequence being recorded. The first of these, the Wheel of Fortune in the N. aisle at Leominster is, however, an important example of this favourite subject, dating from the 13th century, now much faded. The ruined church of Downton on the Rock retains traces of an extensive painted decoration, including figure-subjects, but so weathered as to be quite unidentifiable.

A few examples of domestic painted decoration survive as at Adforton (9). There are late 17th or early 18th-century wooden panels with painted subjects at Upton Court, Little Hereford, and Court Farm, Richard's Castle.

Attention may also be called to the recently discovered paintings illustrating the Commandments in the Black Lion Hotel at Hereford.

Plasterwork: Several houses in N.W. Herefordshire have enriched plaster ceilings of some distinction. One of the earliest and best is the late 16th-century ceiling at Kinnersley Castle, and there are others of the same and rather later date at Monnington Court and Rodd Court. Eye Manor has a long series of elaborately moulded and enriched ceilings of 1680, the date of the house, and ceilings of the same age survive at Titley Court. A house at Walford (1) has a panel of early 17th-century internal pargetting with a mermaid, foliage, and other decorations.

Plate: The communion-plate of the district is remarkable, as including three mediæval pieces. The chalice at Leominster is a rich example with a black-letter inscription round the bowl and a knop formerly decorated in enamel; it dates from late in the 15th century, and was spared for the use of the parish in 1553. The patens at Leominster and Norton Canon are of the same type, though the Leominster piece is the more ornate of the two. Both have the usual sex-foiled sinking with the vernicle in the middle and date from c. 1500.

The Elizabethan cups recorded are twenty-three in number, of which one dates from 1569, and nine either certainly, or probably, from 1571. Four more date from 1576. All of these cups follow the normal Elizabethan form. At Orleton is a cup made up from more than one piece, which is partly of the same age.

Later pieces of plate of some interest include a secular porringer of 1697 at Eyton, an unusual cup of beaker form (1689) at Ford, and a moulded cup with a baluster stem (1696) at Knill.

Pulpits: There is an early 16th-century pulpit with linen-fold panelling at Wigmore, but this is the only mediæval example except for the fragments of what may have been a stone pulpit at Weobley. Of Renaissance pulpits the best is that at Letton, which retains its sounding-board. Others of interest may be noted at Birley, Pembridge, Eye and Monnington-on-Wye; the last forms part of the general fitting of the church in 1679.

Royal Arms: Two important examples of Royal Arms survive in the district. Both are of carved wood, the one at Elton being the arms of Elizabeth on a rectangular panel. The arms of Charles II at Monnington-on-Wye formerly stood on the chancel-screen and are supported by iron stays.

Screens: There are a few rood-screens of interest in the district, the best being the early 16th-century example, with a vaulted loft, at Aymestrey. The rather earlier screen at Eyton also retains its loft, which has a boarded and panelled cove and a richly carved beam in front. The 15th-century screen at Dilwyn has good tracery and carving, but here the loft is a modern restoration. A timber loft, of simple form, survives in the ruined church at Downton on the Rock; it is in very bad repair and owing to the narrowness of the chancel-arch there was never a screen below it. The other rood-screens are of minor interest, but some 15th-century parcloses at Dilwyn may be noted. At Monnington-on-Wye is an interesting chancel-screen of the date (1679) of the church; the Royal Arms, formerly surmounting it, are now on the S. wall of the nave.

Staircases: The earlier staircases are commonly of the type with flat-shaped balusters, sometimes pierced. Examples of these may be seen at Leominster (48), Rodd Court, and Hergest Court, Kington Rural. The best example, however, is at Croft Castle where the balusters are of the diminishing pilaster type. All these date from late in the 16th or early in the 17th century. The finest staircase in the district is that at Wharton Court, Leominster Out, which is of well-type with heavy turned balusters and newels with richly carved terminals of early 17th-century character. Of the same age but of simpler type are the staircases at Heath House, Leintwardine, and Gatley Park, Aymestrey. There is a handsome late 17th-century staircase, with twisted balusters, at Eye Manor, and others of similar character at Titley Court and Leominster (38).

Stalls: The series of stalls with misericordes and screen-work at Leintwardine is the only example of this type of fitting. It seems not improbable that the stalls were formerly in the abbey of Wigmore and removed here at the Dissolution.

Miscellanea: Among fittings of unusual occurrence in this district mention should be made of the late 15th-century salade at Eardisley, said to have been found in the ditch of the castle; a small organ by Father Bernard Smith (1700–1) at Bishopstone and formerly at Eton College Chapel; and, finally, the panelled stone reredos at Leintwardine.