An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in Herefordshire, Volume 3, North West. Originally published by His Majesty's Stationery Office, London, 1934.

This free content was digitised by double rekeying. All rights reserved.

'General Survey of Herefordshire Monuments', in An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in Herefordshire, Volume 3, North West(London, 1934), British History Online https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/rchme/heref/vol3/xliii-lxvii [accessed 26 April 2025].

'General Survey of Herefordshire Monuments', in An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in Herefordshire, Volume 3, North West(London, 1934), British History Online, accessed April 26, 2025, https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/rchme/heref/vol3/xliii-lxvii.

"General Survey of Herefordshire Monuments". An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in Herefordshire, Volume 3, North West. (London, 1934), British History Online. Web. 26 April 2025. https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/rchme/heref/vol3/xliii-lxvii.

In this section

GENERAL SURVEY OF HEREFORDSHIRE MONUMENTS

The Hill Forts of Herefordshire

Herefordshire, like many other counties in the West and South-West of England, includes a large number of hill forts and other defensive earthworks. A superficial survey of these shows a bewildering diversity of detail. This is largely conditioned by the topography of the sites chosen, and a closer examination of the individual examples shows that they belong to two main types.

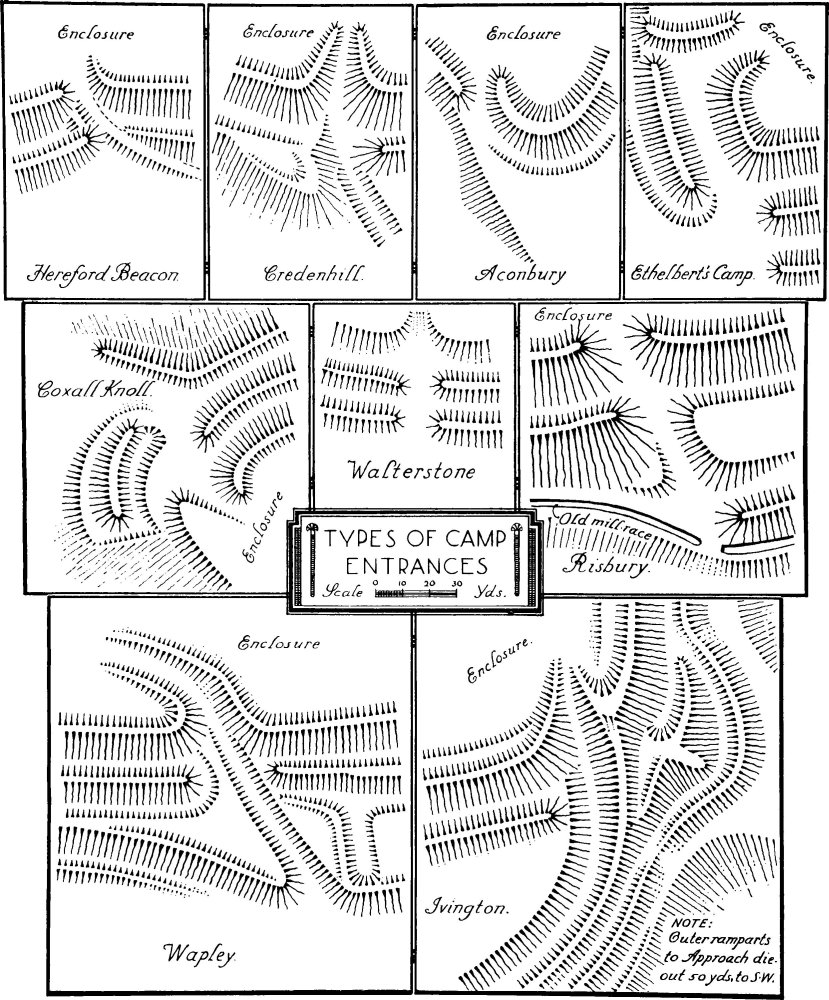

To the first type must be ascribed the hill forts with imposing banks and ditches, generally following the contour of the hill. Usually these enclose a comparatively large area. In some cases the rampart is double or even triple, and the importance attached to a massive bank is shown by the large internal spoil ditches traceable in many places. The choice of hill tops explains the great variety in the plan of these forts, but it should be noted that natural defences are only used when they give additional elevation over the attacking forces. A promontory site with even a moderate upward slope outside the defences across the neck is not favoured. The sites chosen and the large extent of many of these fortresses suggest that the builders were not troubled by any lack of man-power either for the construction or for the defence of their ramparts. A distinctive feature of these camps is the entrance (Fig., p. xliv). (fn. 1) The passage through the innermost line of defence is normally flanked by a pronounced incurving of the ramparts. Analogy with excavated sites in other areas suggests that there were guard-houses at the inner end of the passage thus formed, the outer part being probably spanned by a bridge so that the area immediately in front of the gate would be commanded from all sides. (fn. 2) The approach to the gateway generally runs obliquely through the defences, the roadway being commanded by an overlap of the outer banks or even by detached mounds or platforms. The camp crowning the Herefordshire Beacon (Colwall) and those at Risbury and Wapley represent the most elaborate development of this class, but even comparatively small forts, like Ethelbert's Camp, Dormington, show many characteristic features.

The second type consists of smaller enclosures, in Herefordshire of roughly round or oval plan, with ramparts and ditches of less strength. Sites of a promontory type seem often to have been chosen. The elaborate entrances of the first class are never found, and pronounced incurving of the ramparts is rare, while the approach to the gateway passes directly through the outer defences. Walterstone Camp is the best preserved example within the county, but the same features can be traced in Pen Tŵyn Camp, Brilley, and other more ruined earthworks.

Types of Camp Entrances

This second class represents a simple defensive type that may have arisen at any period. In Herefordshire the typical examples are all found near the south-western border of the county. Beyond this, similar earthworks are recorded in South Wales and Monmouthshire where Gaer Fawr, near Usk, and Lodge Farm Camp, near Caerleon, provide fairly close parallels to Walterstone. In the South of England, where this class of earthwork has been more generally explored, these small simpler camps seem to belong to a period preceding the great hill forts of the latter part of the Early Iron Age. In Wiltshire Figsbury Rings (fn. 3) and the earlier entrenchment within Yarnbury Castle (fn. 4) have both been shown to belong to people using pottery of late Hallstatt or early La Tène type. In Herefordshire, on the other hand, the only evidence available, from a hut within Poston Camp, Vowchurch, indicates a later period. The earliest pottery from the hut floor is native ware, which can be ascribed to the 1st century A.D. The superficial layers above the floor yielded Roman pottery of the 1st and 2nd centuries. The material does not necessarily date the earthwork, but this occupation within the Roman period can be paralleled from analogous sites in South-West Wales, such as Coygon Camp, Carmarthenshire, (fn. 5) where much Roman pottery has been found. Although South Wales was not entirely unaffected by the great development of the hill fort, which marked the last centuries of British independence, the continued use of the small camps and the lack, even in the largest earthworks, of certain features of our first type show that, down to the Roman Conquest, the Silures remained more or less isolated. Dr. Fox (fn. 6) has pointed out that from the Beaker period onward the sea plain of Glamorgan tended to be connected with the opposite shore of the Bristol Channel. The La Tène I brooches from Merthyr Mawr show that this connection was maintained during the earlier part of the Iron Age, and it may be suggested that the ideas embodied in these camps entered by this route. From the coast this type would gradually penetrate into the hinterland, where it was but little affected by subsequent developments in Southern England. (fn. 7) Its extension over the south-west border of Herefordshire would represent the limits of Silurian territory in this direction.

The elaborate hill forts of our first type represent a different and typologically later tradition. These earthworks occur over the whole of South-western England, and all the excavated examples in that region have been shown to belong to a group of cultures of which Glastonbury Lake Village is the type station. (fn. 8) At the time of their greatest extent these cultures, as represented by the pottery of Glastonbury types and by the associated currency bars, extended from Land's End to Sussex, the neighbourhood of Northampton, the Forest of Dean and the Malvern Hills. The earliest objects belonging to this complex are of late La Tène I types, datable to the 3rd or 2nd century B.C.. There is evidence that the whole of the region described was still occupied by people with these cultures at the time of Cæsar's invasion. In the following century a large part of this territory was lost to a Belgic group of invaders, (fn. 9) and at the time of the Claudian Conquest the earlier people had been driven back to the hills bordering the Lower Severn and the South-Western Peninsula. Historically it is clear that the groups in these two regions represent respectively the Dobuni and the Dumnonii.

The Malvern Hills have been suggested as the north-western boundary of this south-western or 'Glastonbury' culture. The Camp on Midsummer Hill (fn. 10) has produced typical pottery, similar to but earlier than that from Lydney, (fn. 11) which was accompanied by La Tène II and III brooches and other contemporary objects. Although this pottery does not definitely date the earthworks there is little doubt that it belonged to the builders. The coarser unornamented ware from the Herefordshire Beacon (fn. 12) probably belongs to the same culture, although certain features are difficult to parallel. The relationship between this pottery and the main ramparts was not established, but typical fragments were found in the body of the bank of the 'Citadel.'

The coins (fn. 13) which belong to the earlier part of the 1st century A.D. would suggest a rather wider extension of the Dobunic area, covering the greater part of Herefordshire. Weston under Penyard, the site of the Roman industrial settlement of Ariconium, (fn. 14) is said to have produced nine British coins, of which six are definitely Dobunic types, and it is reasonable to ascribe the origin of the settlement to this tribe. Less certain evidence is available from Kenchester, (fn. 15) where British gold coins, probably of Dobunic types, have been recorded. A milestone of Numerian from the same site bore the letters R.P.C.D., which Haverfield suggested might possibly stand for Respublica civitatis Dobunorum. The other finds of coins are isolated individual specimens and may well be strays in alien areas.

While it is not possible to affirm that the elaborate hill forts west of the Malvern Hills represent an actual Dobunic occupation it seems clear that the introduction of this system of fortification must be ascribed to the influence of the peoples of the 'Glastonbury' culture. Thus examples in Herefordshire occur all over the area north and east of the Wye, while several are found on the hills immediately south and west of that river. Farther south Llanmelin above Caerwent, (fn. 16) which has yielded typical pottery, is the westernmost example. North of Herefordshire the type is common in the Welsh Marches and in North Wales. In Shropshire, which under the Empire fell within the territory of the Cornovii, Titterstone (fn. 17) has produced no contemporary pottery, but the structural analogies with the south-western camps were too close to be entirely due to chance. During the first season's work at the Breidden, (fn. 18) two miles west of the Shropshire border, late Roman pottery was found in the level covering the debris from the fallen wall. This proves the pre-Roman date of the defences, as it can hardly be supposed that the erection of so large a fort on the fringe of the civil province would have been permitted under the early Empire. The North Wales group was extensively occupied within the Roman period, but in spite of the lack of definite evidence it is difficult to avoid the conclusion that this non-Roman tradition goes back to pre-Roman models. (fn. 19) It is clear that the fortifications of the whole region north of the Dobunic area were due to influences originating with the 'Glastonbury' peoples. Since the hill forts of the Cornovii are, in the present state of our knowledge, superficially indistinguishable from those of the Dobuni, further excavations in Herefordshire will be needed to establish the frontier between these tribes. Until this evidence is available it would be unwise to ascribe to the Dobuni anything west of the Malvern Hills, with the possible exception of Ariconium.

Although this boundary must remain uncertain the frontier between the builders of the large hill forts and the Silures, represented by the smaller type of earthwork, is clear. Beyond the Wye, Llanmelin in Monmouthshire, with Ganarew and Aconbury in Herefordshire form an outpost line, but the great forest area of South-West Herefordshire remained an insuperable obstacle to penetration in this direction, and substantially the boundary was the same as that traced by Offa many centuries later. (fn. 20) Behind this the Silures maintained their independence, and, at least in the science of fortification, proved unresponsive to the influences which affected the tribes of the Marches and of North Wales.

C. A. RALEGH RADFORD.

Appendix on the Pottery (in Hereford Museum)

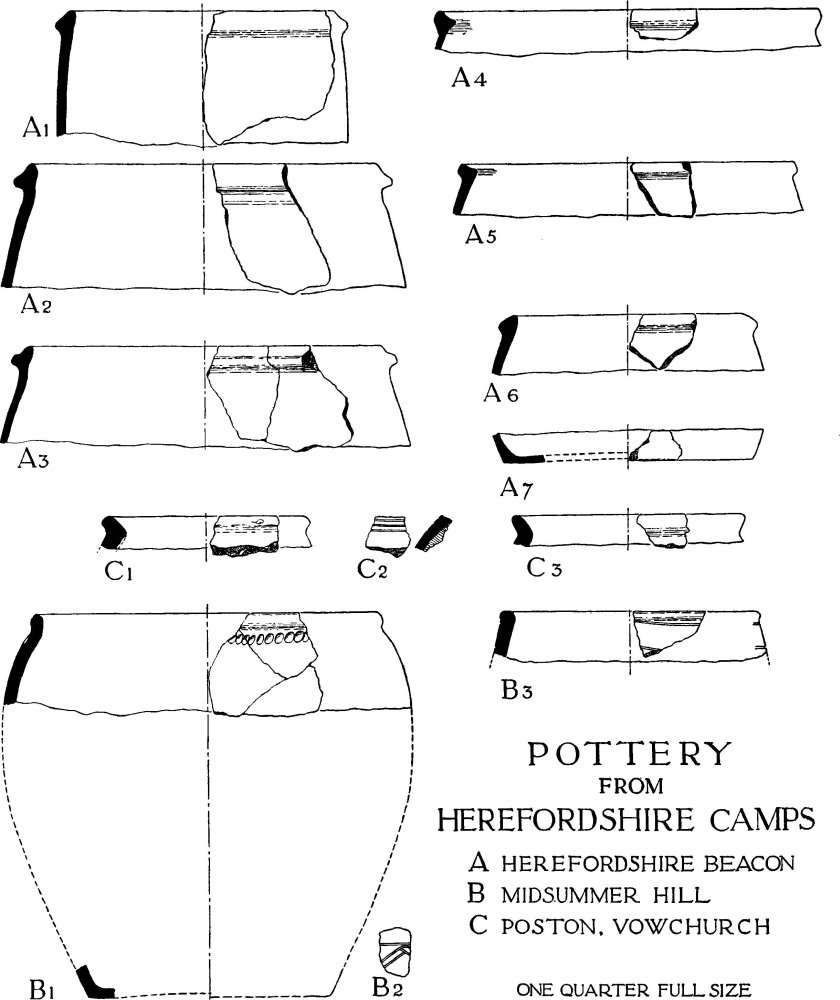

A. Herefordshire Beacon.

(1) Rim, with slight external flange, and part of upright side. Hard, well fired ware with some admixture of grit. The outer surface smooth, the inner left rough. The vessel is a cooking pot with a flat bottom. Pit 4.

(2) Similar rim and part of convex side. Same ware. Pit 4.

(3) Similar fragment. Found 1 ft. below surface of north rampart of 'Citadel.'

(4) Thickened rim, with internal groove for lid, and part of convex side. Same ware. Pit 4.

(5) Similar fragment. Pit 4.

(6) Thickened rim and part of convex side. Same ware. Pit 4.

(7) Bottom of convex side and part of flat base. Same ware. Pit 4. All the fragments illustrated together with many others belong to straight or convex-sided cooking pots. The ware is unusually well fired, but this can be paralleled from other sites in the South Midlands (e.g. Radley, Ant. Journ., xi, 401, fig. 2b). The absence of any ornament or other distinctive features makes it impossible to class this pottery with any certainty, but the shape, resembling the 'flower-pot,' is most at home in cultures allied to that of the Glastonbury Lake Village. The hardness of the fabric suggests a date not long before the Roman Conquest. The greater part of the pottery is unstratified, but a deposit, including No. 4, was found 1 ft. below the interior slope of the northern rampart of the 'Citadel' (Journ. R. Anthrop. Inst., x, 328).

B. Midsummer Hill Camp.

(1) Fragments of rim, convex side and flat base of cooking pot. Coarse, poorly fired ware with a certain admixture of grit. Smooth polished soapy surface. On the shoulder, immediately below the rim, is a row of finger-tip impressions.

(2) Fragment of side of similar vessel ornamented with incised lines. Same ware.

(3) Fragment of moulded rim and straight side from a similar vessel. Same ware.

In fabric these and the other fragments found may be compared with the normal La Tène ware of South-West England. The shape of No. 1 approximates to the 'flower-pot' of Lydney (Report, fig. 24) and other sites, especially in Sussex (e.g. Mount Caburn, Sussex Arch. Coll., lxviii, pl. ix, 63). The simplicity of the rims and the finger-tip ornament suggest an early date, but in a district, remote from the centre of this culture, these features must not be too far stressed. A date in the 2nd or 1st century B.C.. is reasonable. The find spot of the fragments illustrated is not recorded, but all pottery from the camp is of the same fabric, and some fragments were found in a position, which makes it probable that they were contemporary with the earliest occupation of the camp. (Woolhope Naturalists' Field Club, 1924–6, pl. 22.)

C. Poston Camp, Vowchurch.

(1) Thickened rim and neck. Diam. 16.5 cm. Thick, heavy fabric containing a large proportion of grit. Smooth polished black surface. The shape is a cooking pot with convex sides and a flat bottom.

(2) Fragment from the upper part of the side of a similar vessel. Similar ware, but rather thinner. Three horizontal grooves.

(3) Everted rim and neck. Diameter 18 cm. Ware as No. 1. The shape should also probably be restored as No. 1.

Pottery from Herefordshire Camps

The deposit from the hut floor consisted of the three fragments illustrated and a fourth of similar ware from the side of a cooking pot. The levels immediately above contained Romano-British wares not earlier than the Flavian period. The fragments all belong to cooking pots, the commonest shape on Iron Age sites in this region. The better formed rims compare with the pottery from Lydney (Report, fig. 24, 1–3) rather than that from Midsummer Hill (Woolhope Naturalists' Field Club, 1924–6, pl. 17). This, and the position of the Romano-British wares, suggest a date not earlier than the 1st century A.D., and this native pottery may well be contemporary with the Roman Conquest.

Roman Herefordshire

It is easy enough to describe Herefordshire as a border-county. To the west the sombre glens and plateaux of the Black Mountains and the rough horizon of Radnorshire mark the margin of those outlands above which, even on a fine summer day, the airman flying over England may see a lasting barrier of haze or cloud. To the east the knife-edge of the Malvern Hills breaks the transition to the English midlands. But, for the rest, the Old Red Sandstone which floors nine-tenths of the county must anciently have borne a forest differing little, if at all, from that which clad the midland clays. In the 8th century King Offa found this Sandstone forest sufficiently obstructive to form (save in a few clearings) a local substitute for his boundary-dyke against the Welsh. At the same time by including most of it, implicitly at least, within his province, he showed that it belonged properly to the lowland, not to the highland zone. Indeed, if by a border-county we think instinctively of moor and moss and the piping curlew, then it were well not to fit the conventional phrase to that comfortable and fertile shire which, in Roman times as to-day, was essentially integral with the English plain.

For Roman Herefordshire, after the subjugation of the Silures and the Ordovices of Wales in the first generation of conquest, was a land of peace, of small country-towns, industrial villages and farmsteads, with scarcely a trace of military works and men. It may be that the castle-bailey of Longtown, like those of Cardiff and Carisbrooke, owes its unusual rectangular form to the underlying vestiges of a Roman fort. Certainly its situation, at a triple valleyjunction in the foot-hills of the Black Mountains, would suit Roman no less than Norman strategy; it lies nearly midway between the Roman forts at Abergavenny on the Usk and Clyro on the Wye, and is a normal march from both of them. Plan and geography agree in suggesting that the excavator may some day find a Roman border-fort at Longtown. Meanwhile, evidence is Jacking.

Another oblong earthwork, at Leintwardine on the so-called Watling Street between Kenchester and Wroxeter, has sometimes been called a 'camp' in the loose nomenclature of the older antiquaries; but, although the site is in this case indubitably Roman, it has no obvious strategic value and there is no reason to suppose that it was ever anything other than that of a small fenced town (ten to fourteen acres in extent) of a kind common along the highways of Roman Britain.

Map of Herefordshire Showing Roman Sites and Roads and Principal Camps

The only work, indeed, which, however indirectly, links Herefordshire with the military life of the province is the Watling Street to which reference has been made. The antiquity of the name in this county is uncertain, (fn. 21) but that of the street can be inferred with reasonable precision, forming as it does a part of the base-line on which the Roman frontier-system of Wales was laid out in the seventies of the 1st century A.D. At the southern terminus archæology has dated the foundation of the legionary fortress at Caerleon, in Monmouthshire, to about 75 A.D.; Chester, the equivalent legionary fortress at the northern end of the street, may be a little earlier, although we do not yet know much about its beginnings. Between them the road itself, or a closely-related loop-road, passed by the Roman town at Kenchester, where intermittent excavation points again to the seventies as the initial date. Certain stretches of the road—for example, in the neighbourhood of the early site at Wroxeter in Shropshire—may well be a decade or two earlier; but as a whole we may regard the Herefordshire Watling Street (alias East Street or Stone Street), in its wider context, as the work of that vigorous Flavian emperor, Vespasian, who during the early days of the conquest had himself led the second legion into Western Britain.

The general course of the road is indicated in Iter XII of the Antonine Itinerary:—

M.P.M.

| Iscae leg. II Augusta (Caerleon) | |

| Burrio (probably Usk) | VIIII |

| Gobannio (Abergavenny) | XII |

| Magnis (Kenchester) | XXII |

| Bravonio (Leintwardine) | XXIIII |

| Viroconio (Wroxeter) | XXVII |

Between Abergavenny and Kenchester, the road is lost at first in the fringe of the Black Mountains; even a Roman military road, in broken country such as this, quickly loses its straightness and becomes proportionally difficult to identify. On leaving the valley of the Dore, however, its course becomes clear, and the actual road-metal has been exposed in the stationyard at Abbey Dore (vol. i, p. 1). Thence, known in part as Stone or Stoney Street, it proceeds directly to Kenchester, possibly to the road-junction which has been identified by excavation without the E. gate (vol. ii, p. 93). It continues north-eastwards from that point for two miles towards Canon Pyon, in the vicinity of which it bends northward round the shoulder of the hill, and may (though the evidence is very slight) have been joined hereabouts by a road from Weston-under-Penyard (Ariconium). Again farther north, it passes through a village bearing the significant name of Stretford, and so on to Wigmore where, 800 yards north of the point where it crosses the Ludlow road, it stands 2 to 3 feet above the marshland and has a slabbed surface 10 feet wide. (fn. 22) It proceeds thence to Leintwardine (Bravonium), (fn. 23) whereafter it shortly passes into Shropshire near Clungunford, on the way to Wroxeter.

The only other route which brings the county into the Antonine Itinerary is Iter XIII:—

M.P.M.

| Burrio (probably Usk) | |

| Blestio (possibly Monmouth) | XI |

| Ariconio (probably Weston-under-Penyard) | XI |

| Glevo (Gloucester) Etc. | XV |

The identification of this road, as of the places along it, is fraught with doubt. A stretch of road south of the probable site of Ariconium is marked as Roman on the Ordnance map, but at no point between Usk and Gloucester has the actual road-metal been seen. The difficulty is accentuated by the hilliness of the country through which the first part of the route must have run, and by the long discontinuance of such through-traffic as might have helped to preserve the line in the intensely rural district where the second part of it must have lain. Discussion of the problem is unlikely to be fruitful until local fieldwork produces fresh evidence.

Fragments of other Roman roads have been identified or suspected within the county. Recently a road made of "Roman scoriæ and stones . . . running in the direction of the Forest of Dean" has been recorded from Weston-under-Penyard. (fn. 24) Parallel to, and about 6 miles east of, the Watling Street, between Kenchester and Leintwardine, a stretch of 2 miles or more of straight road passes through the Roman site of Blackwardine (Stoke Prior, vol. iii, p. 187) and a second Stretford. The actual structure of the road has apparently been seen at more than one point (Woolhope Field Club Trans., v, 1885, p. 340), but no details are recorded. Its further course has not been traced; its general direction, however, towards the south-south-east is picked up by the road which crosses the Frome, significantly perhaps, at Stretton Grandison, and thence proceeds in a notably direct line for about 9 miles, passing the county-boundary at Little Marcle, and losing its purposefulness near Dymock in Gloucestershire. Thence it now meanders to Gloucester in an un-Roman manner, which emphasizes its previous directness and gives some show of likelihood to the identification of the Stretton Grandison-Dymock route as a vestige of a Roman cross-country road to Gloucester.

One more road may be included in our list. It ran east and west through the Roman town at Kenchester, and can be identified approximately for 2 miles or more up the Wye valley towards the fort at Clyro. Eastwards, it is represented by nearly straight lengths of existing road for about 8½ miles, passing well to the north of Hereford. If continued for another 3½ miles, it would strike the supposed north-south road at Stretton Grandison, but again evidence is lacking.

If we turn now to the economic needs which these, and doubtless many other roads, helped to supply, we are confronted with a reversal of the economic succession which usually confronts the student of an English county. To-day, a man of Herefordshire may boast that, unless for the making of cider, his county is devoid of non-agricultural industries. In Roman times such an assertion would not have been strictly true. To the south, within 2 or 3 miles of Ross-on-Wye, we enter the limestone belt of the Forest of Dean where iron was, until recently, mined more or less continuously from the Roman period, if not earlier. This industry belongs rather to Gloucestershire than to Herefordshire, but it was not without its reactions upon the Roman occupation of our county. Not that any actual iron-mine of Roman date has been identified in Herefordshire; indeed most of the 'scowles' or workings which a popular antiquarianism has dubbed 'Roman' up and down the Forest may equally well be mediæval or later. Nevertheless, a sealed Roman iron-mine at Lydney, on the Severn, and more vaguely associated Roman relics elsewhere are sufficient to prove the exploitation of the ores in the Roman period, and to form a background to the discoveries which led an enthusiastic writer in 1821 to describe the Roman site at Weston-under-Penyard (vol. ii, p. 209), near Ross, as a 'Roman Birmingham.' The discoveries here and hereabouts have included heaps and layers of iron scoriæ, which have discoloured the earth over a very large area, and have given the name of 'The Cindries' or 'Cinder Hill' to a part of the site. 'Hand-bloomeries' and 'floors' and a road made of "Roman scoriæ" (see above) are also said to have been found, together with various masonry structures, all incompletely explored or described. Coins range from the 1st to the 4th century A.D., and a series exhibited in 1870 as from the site included "some of Cunobelin," an interesting link with eastern Britain about the time of the Roman conquest, could the circumstances of discovery be substantiated. Other 'finds' of one kind or another seem to have been numerous, and, in spite of the nebulousness of the record, it is clear both that the settlement was extensive and that it made a considerable use of the product of the Forest mines. No other Roman town in the whole province, perhaps, had quite so specialized an industrial character. Its identification with the Ariconi(o) of the 13th Iter need not give rise to disputation; there is at least no serious rival to the claim, although at Goodrich, Peterstow and elsewhere within a radius of some 5 miles intermittent accumulations of cinders or slag are similarly recorded in proximity to Roman coins and pottery. (fn. 25)

When we leave the environs of Ross and Weston, we pass into a Romano-British countryside of a more familiar kind. The prevalence of natural forest impeded but did not prevent the processes of Romanization, and the little walled town at Kenchester—the Magn(is) of the 12th Iter—differed in scale rather than in character from other walled towns of the province. Its 22 acres make a small show beside the 330 acres of Londinium or the 220 acres of Verulamium; but its well-drained streets, its colonnades and its mosaic floors are equally those of the Roman world, and illustrate, more dramatically than the nearer cities or even than the remoter forts, the determined skill with which civilization was thrust by Rome into the margins of Europe.

Unfortunately, we cannot at present recover the date and progress of this brave effort in partibus. There are slight indications that two of the partially excavated buildings at Kenchester were erected in the 2nd century—the heyday, it seems, of urban life in Roman Britain— and, if evidence observed in 1796 is reliable, the town-wall was constructed or reconstructed after the time of Numerian (283–4 A.D.), whose milestone is said to have been discovered in its foundations. These particles of information serve but to emphasize our ignorance; and even they fail to hint at the ultimate fate of the little town. The coins, as usual, scarcely go beyond the reign of Gratian, who died in 383 A.D. By that time, incessant raids and chronic insecurity had brought country-life in a great part of Britain to a standstill, and urban life, which had at best been always something of a forced growth in its midst, had little incentive to outlive it. Nevertheless, the tenacity of a civic population, even when reduced to slum-conditions, doubtless maintained a meagre population in many of our walled towns right into the Dark Ages; the recent excavation of Verulamium, for example, has shown a little of the squalor in which, during and after the last phase of Roman rule in the island, a part at least of the denizens of a first-class city were content to live. Distant Kenchester, essentially (we must suppose) a markettown supplying the needs of a simple rural district, must, on analogy, have died in fact many years before its last "Roman citizen" left its decaying walls. Some day it will be worth while for a trained excavator, unbiassed by the tradition of Gildas, to dig carefully into the latter history of Roman Kenchester and find out something of that slow economic decline to which ultimate fire and slaughter, if they came at all, came perhaps rather as a sort of scavenging than as a real force of destruction.

The only other Roman town or village in Herefordshire that, so far as we know, rose to the dignity of defences was the small site on the Watling Street at Leintwardine. The mileages enable us to identify this site with the Bravoni(o) of the Antonine Itinerary, but, beyond that fact, and the traces of a much-scarred earthwork enclosing an area about half that of Roman Kenchester, we know nothing significant about the place. It served, doubtless, as a posting-station on the high-road and as a minor market-centre, and may be compared with other roadside 'stations' such as Manduessedum on the Leicestershire Watling Street. Groups of lynchets at three points in the vicinity (see vol. iii, p. 110) may be relics of its agricultural activities; they represent long strip-fields of a type normal in early mediæval England, but dating occasionally perhaps (as at Housesteads on Hadrian's Wall) from Roman times. Beyond this, even guesswork is compelled at present to call a halt.

Nor need other possible village-sites detain us long in the present context. At Blackwardine, in the parish of Stoke Prior (q.v.), the extent and chronological range of the objects found during the making of a railway suggest something more than an isolated building. Stretton Grandison, which lies, as we have seen, at a possible junction of Roman roads, has yielded Roman objects and may well represent another small Roman community. In Bishop's Wood in the parish of Walford-on-Wye (vol. ii, p. 195) a large coin-hoard of the middle of the 4th century, Roman pottery and an ill-described earthwork, which has now vanished, may have been related to one another as the relics of yet another minor settlement. And somewhere between Caerleon and Kenchester, the Ravenna geographer has placed Cicutio as an insoluble problem for the speculative antiquary with a mind for such things. (fn. 26)

From the villages we turn to the 'villas,' whereunder custom includes all isolated buildings of unspecialized or indeterminate character—farmsteads, cottages, occasionally the big houses of the landed gentry. In this category, pride of place must be given to the walls and mosaic pavement found in 1812 under Bishopstone rectory, at a distance of about 250 yards from the Roman road to Kenchester, here 1½ miles away. The mosaic has been immortalized both by a Wordsworth sonnet (". . . For fresh and clear, As if its hues were of the passing year, Dawns this time-buried pavement") and by a fairly adequate engraving, which is here reproduced (pl. 88). This and the solid character of the associated walls point to a house of substance and distinction unparalleled in the county outside Kenchester itself. For the rest, there is little to record. Other tessellated floors vaguely mentioned at Walterstone and Whitchurch (vol. i, pp. 246 and 253), and tiles and pottery at Putley, complete the list of Roman structural remains, save for the kiln (if such it was) at Donnington (vol. ii, p. 69), for pottery and "pottery-clay" at Marley Hall, Ledbury, (fn. 27) and for a well, possibly Roman, at Brinsop. With non-structural relics these inventories are not specifically concerned; lists of the coins, potsherds and the like which have been found from time to time up and down the county are set forth in the Victoria County History, but they add little to the picture. The most notable of them are the inscribed altar which has achieved a new lease of life as the stoup of Tretire church (vol. i, p. 240), and the part of a carved Roman tombstone which has been less ceremoniously preserved in the structure of Upton Bishop church (vol. ii, p. 194), and has there escaped the attention that it deserves.

On the whole, when we recall the extent of natural forest-land which it included, Herefordshire cannot complain of its share of Romanization—a share which, when the moment arrives, could easily and substantially be increased by a little judicious exploration.

[See the Victoria County History, Herefordshire, i, 167–197; Bevan, Davies, and Haverfield, Archæological Survey of Herefordshire; and these Inventories of Herefordshire.]

R. E. M. WHEELER.

Pre-Conquest Herefordshire

The early history of the district known since at least the 11th century as Herefordshire is impenetrably obscure. No traditions of its conquest have survived. The Western midlands as a whole were far from the centres of Old English historical writing, and the ancient church of Hereford has produced no body of local charters in any way comparable to that which has come down from the neighbouring Worcester. In the aggregate, a considerable number of facts relating to pre-Conquest Herefordshire are recorded on good, or at least passable, authority. But they are quite inadequate to support anything approaching a continuous history of the shire.

The most ancient authority for this history is a list of bishops written early in the 9th century. (fn. 28) The series begins with a bishop named Putta, who is otherwise unknown, but probably received consecration from archbishop Theodore of Canterbury between the years 670 and 680. (fn. 29) It would be unsafe to assume that his seat was in Hereford, but his successors were certainly established there by the middle of the 8th century. In 803 a council of the province of Canterbury was attended by Wulfheard, Herefordensis ecclesiæ episcopus, accompanied by an abbot, three priests, and one or two deacons, (fn. 30) and an act of the same council (fn. 31) which speaks of certain monasteries given to the church of Hereford "in ancient days" shows that a bishop's seat had then existed in Hereford for more than a generation. The community serving the bishop's church appears towards the middle of the 9th century, when bishop Cuthwulf and the "congregatio" of the church of Hereford grant land by the river Frome to an ealdorman, with the provision that after three lives have expired it shall be given up to the monastery at Bromyard. (fn. 32) The continuity of the see was not broken by the Danish wars, and the outline of its history is clear.

Originally, the people served by this bishopric seem to have been known as the "Hecani," (fn. 33) an ancient and obscure name, which probably became obsolete at an early date. They also appear in pre-Conquest sources under the name of "Magesetenses" or "Magesætan," and this description remained in current use until the 11th century. It first appears in a document of 811, when archbishop Wulfred of Canterbury gave certain land which he had recently acquired "on Magonsetum aet Geardcylle," that is Yarkhill, to Cenwulf king of the Mercians. (fn. 34) It reappears in a charter of king Edgar giving land at Staunton-on-Arrow "in pago Magesætna" to his thegn Ealhstan, (fn. 35) and the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, in recording the English defeat at Assandun in 1016, states that ealdorman Eadric "stole away first in flight with the Magesætan." (fn. 36) A people whose territory included both Staunton-on-Arrow and Yarkhill must have occupied the whole northern half of the present Herefordshire, and the fact that the mediæval diocese of Hereford included the southern hundreds of Shropshire suggests that they also belonged to the Magesætan. The greater part of Herefordshire south and west of the Wye was still Welsh in the early 11th century, and was only loosely attached to the county when the Domesday survey was made.

In the 7th and 8th centuries the Magesætan, like their eastern neighbours, the Hwicce of Worcestershire and Gloucestershire, were ruled by a separate dynasty of under-kings. (fn. 37) They are never mentioned by Bede or other early historians, but several members of the house were prominent in early English monastic history, and their genealogy has been preserved in what seems substantially an accurate form. The family was believed to descend from a son of Penda, king of the Mercians named Merewalh, and his wife Eormenbeorg, a lady of the Kentish royal house. Their children were Mildburh, foundress of Much Wenlock abbey, Mildthryth, abbess of Minster in Thanet, Mildgyth, a nun at Eastry, and a son named Merefin of whom nothing more is known. (fn. 38) Florence of Worcester, in a passage which seems to be derived from materials now lost, describes Merewalh as king of the western Hecani, and adds that his brother Mearchelm reigned after him. (fn. 39) The alliteration which runs through all these names suggests the antiquity of the series, though it also disassociates the family from the Mercian royal house, in which names beginning with M are never found. (fn. 40) The list is indirectly supported by an ancient inscription on a cross seen at Hereford by William of Malmesbury, commemorating among other persons a regulus named Milfrith and his wife Cwenburh. (fn. 41) Milfrith falls outside the main line of tradition about Merewalh and his sons, but his name preserves the alliteration followed in that family, and the connexion of the group with Hereford is strengthened by the fact that he was remembered there.

There is no trace of the family in Mercian documents of the 8th century, and it had probably lost its semi-royal position before the time of Offa, when these documents become numerous. The power of the great Mercian kings was won at the expense of many dynasties, wholly or partly independent, and one episode in this conflict, though its details are utterly obscure, was connected by an early tradition with Herefordshire. In 794 Offa ordered Ethelbert, king of the East Angles, to be beheaded. (fn. 42) Before the end of the 10th century Ethelbert's body lay in Hereford cathedral, where he was honoured as a saint and martyr. (fn. 43) By the beginning of the 12th century his cult had produced a life in which the circumstances of his death are described at length, and with much legendary detail. (fn. 44) These details spoil the life as history, but they have a local character, and point to a popular interest in St. Ethelbert which may well be of ancient origin. It is best explained by accepting the central fact in his story, his murder by Offa's command at some place in the neighbourhood of Hereford, and there is nothing against the identification of the royal village of 'Suttun,' where, according to the life, he was entertained, and, apparently, killed, with Sutton Walls, 4 miles from the city.

The clearest evidence of the direct rule of the Mercian kings in what was to become Herefordshire is the great earthwork called Offa's Dyke. There is no serious doubt that its name represents an accurate tradition. The life of king Alfred by bishop Asser, which records incidentally that Offa ordered a 'vallum' to be made from sea to sea between Wales and Mercia, has shown under minute examination no features incompatible with a 9th century date. (fn. 45) Asser was a Welshman by birth and long residence, he was intimate with an English king interested in history, and he wrote within a century of Offa's death. His evidence as to the date of the great visible boundary between the countries of his birth and adoption cannot easily be set aside. Offa reigned from 757 until 796, and there are no means of determining within these limits the period to which his dyke belongs. It should probably be assigned to his later years, for in 760 the Welsh attacked Hereford itself, (fn. 46) and Offa's rise to unchallenged supremacy in England was slow. In any case it seems certain that the dyke was completed before his death, for it is unlikely that any of his successors in the Mercian kingdom commanded the resources necessary to continue a work upon so great a scale.

In Herefordshire the course of the dyke is interrupted. Its line can be followed from Knill on the Radnorshire border to the Wye at Bridge Sollers, but there is no trace of it between this point and Hereford, and it is probable that the river itself formed the general boundary from Bridge Sollers to Redbrook below Monmouth, where Offa's work reappears in continuous form. In any case it is clear that Offa's boundary line left more than a third of the present Herefordshire in Welsh possession. To the north of the Wye in Herefordshire and east Radnorshire a number of villages bearing English names occur on the Welsh side of the dyke. Most of these names are of a type which tells nothing as to their date, (fn. 47) but some of them have an ancient appearance. It is hard to believe that such a name as the Radnorshire Burlingjobb, in Domesday, Berchelincope, (fn. 48) can have come into being later than the time of Offa. These place-names have not yet been fully investigated, and any argument from them is hazardous, but they certainly raise the possibility that, in this quarter, the line chosen for Offa's Dyke may have meant the surrender of English territory to the Welsh.

In any case, Hereford remained a border-town. Its fortification may belong to this period, (fn. 49) but apart from the succession of its bishops the history of Hereford and its neighbourhood is almost a blank for a century after Offa's death. The one reference which throws a faint light on the condition of the district in the last phase of the Mercian kingdom comes from a late manuscript, and in a corrupt form. A record of early gifts to the monastery of Gloucester ends with the statement that a certain Nodehard, described as præfectus et comes regis in Magansetum, gave land to that house 'through' Beornwulf, king of the Mercians from 823 until 825. (fn. 50) As the words præfectus et comes regis in the Mercian Latin of this period mean 'ealdorman and member of the king's bodyguard' the description is interesting, for it shows the Magesætan after the disappearance of their own dynasty, subject to an officer connected by a very intimate tie with the Mercian king.

Whether Hereford was fortified under Mercian or West Saxon authority, it certainly counted as a burh in the early 10th century, when its men are known to have shared in a victory over a Danish raiding army. In this raid the Danes had captured Cyfeiliog, bishop of Llandaff, in a district which the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle calls Ircingafeld, (fn. 51) the English name for the Welsh country between the Wye, the Worm, and the Monnow. The Ircingafeld of the Chronicle, a name derived from the Ariconium of the Antonine Itinerary, survived in the form Irchenefeld as the name of the mediæval rural deanery which corresponded with this district. (fn. 52) In Wales this region was called Erging, (fn. 53) and its ancient independence was remembered long after it had been effectively annexed to Herefordshire. At the beginning of the 10th century, although its independence was still strong, it was already gravitating towards the strong power founded by Alfred and Edward the Elder. The fact that King Edward ransomed Bishop Cyfeiliog from the Danes, though not conclusive, certainly suggests that he and his people may have regarded the English king as their overlord. In the next generation the signs of English authority in this quarter become clearer. A contemporary life of Athelstan, preserved by William of Malmesbury, (fn. 54) records that Athelstan caused the reguli of the 'North Welsh' (fn. 55) to come to him at Hereford and promise tribute, and adds the important statement that he appointed the river Wye as the boundary between Welsh and English.

To the reign of Athelstan or the time immediately following, there belongs a curious document, the so-called Ordinance concerning the Dunsæte, which illustrates the condition of the district south of Hereford. (fn. 56) The Dunsæte are otherwise unknown, but the Ordinance shows that their country lay to the north of Gwent, the modern Monmouthshire, that they were partly English and partly Welsh, and that the two races covered by the name were divided by a river which can hardly be other than the Wye. The Ordinance takes the form of a treaty between the English witan and the leaders of the Welsh nation, and the English king, whose name is never given, is only in the background. The treaty was intended to define the relations between the two races constituting the Dunsæte in regard, particularly, to the emendation of manslaughter, the conduct of suits about stolen cattle, and the conditions under which Englishmen and Welshmen might pass into each others' territory. The Englishmen affected by the treaty were presumably the inhabitants of the country immediately to the east of the Wye between Hereford and Monmouth. The Welsh were the men of 'Ircingafeld,' and the treaty is valuable as showing how little their position had been affected by English encroachment since the time of Offa. They may have acknowledged the overlordship of the English king, but they enjoyed a real autonomy.

The importance of Hereford in the following century was two-fold. It was a defensible post on a very dangerous border, but it was also a local centre of trade, the seat of a bishop, and the only minting-place west of Severn. (fn. 57) The date at which it became the head of a definite administrative division is uncertain. A shire may have been organised around the town at any period during the 10th century, if not during the last years of the 9th. But Herefordshire is not mentioned by name in any contemporary source until the reign of Cnut (fn. 58) and it is possible that the shire had come into being not very long before that date. It is included in the list of shires commonly called the County Hidage, (fn. 59) but the oldest form of this list cannot well be earlier than 1000, and may be considerably later. The survival of the name of the Magesætan into the 11th century (fn. 60) suggests that the division of their territory between the two shires grouped round Hereford and Shrewsbury was not of very long standing at that time. Whatever the date at which the shire was created, its boundaries must have been very different from those of the modern county. On the south-west, the river Dore was regarded as the English boundary at the middle of the 11th century, and on the south, the Domesday Survey shows 'Arcenefeld' still unassimilated to the districts north of Wye.

In the generation preceding the Norman Conquest, Herefordshire can have had no settled boundary towards either the west or south. The whole Welsh border was threatened in this period by Gruffydd ap Llewelyn, one of the very few princes of his race recognised throughout Wales, and no part of that border was more vulnerable than Herefordshire. (fn. 61) This frontier danger must be connected with the remarkably early appearance of a Norman military colony in the county. At the middle of the century, if not before, it was placed under a Norman earl of the highest rank, Ralf, son of Drogo, count of the Vexin Normand, and Goda, daughter of King Æthelred II. (fn. 62) Individual Frenchmen are known to have built a number of castles in the county before 1052. (fn. 63) Few of them can now be identified, but there is every reason to believe that Richard's Castle takes its name from Richard, son of Scrob, a Norman settler of this period. A certain Osbern, surnamed Pentecost, is known to have held a Herefordshire castle in 1052, probably, though not conclusively, identified with Ewyas Harold, which was re-fortified between 1067 and 1071, and must therefore be a work of the Confessor's reign. (fn. 64) Other castles of the period, such as that held in 1052 by one Hugh, described as socius of Osbern Pentecost, doubtless survive among the numerous motte and bailey earthworks of the county. It is uncertain how far the castles built by these men formed part of an organised scheme of border defence. The contemporary writers who refer to them speak as if they were the work of individuals. The only castle which can reasonably be attributed to Earl Ralf himself is that of Hereford, of which the existence in 1052 is implied by the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle.

As an experiment in border defence, these measures were unsuccessful. The castles were unpopular, and the emphasis laid on them in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle is due to the misdeeds attributed to their garrisons. In 1052, Gruffydd ap Llewelyn defeated both the countrymen and 'castle-men,' presumably of Hereford, near Leominster. Three years later, in alliance with Ælfgar the exiled Earl of Mercia, he defeated Earl Ralf and the English mounted fyrd 2 miles from Hereford, afterwards burning the town and cathedral. Within the year, Earl Harold and an army drawn from all England had occupied Hereford and followed the Welsh and their allies to a point beyond the river Dore. (fn. 65) The town was re-fortified, and a ditch dug around it, a fact which shows that in Anglo-Saxon times, a place might rank as a burh for more than a hundred years with very rudimentary defences. The Welsh danger disappeared for a time in 1063, when Gruffydd ap Llewelyn was defeated by Harold and killed by his own people, but his earlier raids into Herefordshire had shown that the county could not be defended by its own resources. (fn. 66) With the Norman Conquest, this position was immediately reversed. Within five years of the battle of Hastings, Herefordshire had become the base of a Norman attack upon Central and Southern Wales.

Early in 1067, the Conqueror created William fitz Osbern of Breteuil Earl of Hereford. (fn. 67) It was an earldom of the so-called 'palatine' type, in which the earl replaced the king as lord of the county town and of all landholders within the shire except its ancient ecclesiastical foundations. William fitz Osbern was killed in Flanders in 1071, but his rule in Herefordshire affected the whole subsequent history of the county. He was a great castle-builder, and Domesday Book shows him as the founder of Clifford castle in the west of the county and Wigmore castle in the north. He re-fortified Ewyas Harold, which like Clifford and Richard's Castle appears in Domesday Book as the centre of a territory organised for its defence, a castlery of the French pattern. The Norman knights whom he introduced into his earldom formed a privileged class, and his rule that no knight should pay more than seven shillings for any offence was still operative in the early 12th century. He established a colony of French burgesses at Hereford itself, and granted them the 'laws and customs' enjoyed by the men of his Norman bourg of Breteuil, a concession imitated by the lords of many towns on the Welsh border and elsewhere. He began the Norman conquest of South Wales by the occupation of Gwent, where he founded the castles of Chepstow, Monmouth, and probably Caerleon. His rule in Herefordshire was short, and the earldom which had been created for him came to an end in 1074 with the forfeiture of his irresponsible son and successor; but the Domesday Survey bears witness to the thoroughness of the revolution which he had carried through in his four years of power.

The fall of his house left the way clear for the rise of the families which were to dominate Herefordshire in the early Middle Ages. Most of the feudal honours which centred on the county had come into being by the date of Domesday Book, (fn. 68) which shows Roger de Laci of Weobley the greatest of the local tenants in chief, and Ralf de Mortimer second to him. Herefordshire is one of the counties in which the military basis of the honour is clearest, and the mediæval honours of Snodhill, Kilpeck, Richard's Castle, Ewyas Harold, and Monmouth, (fn. 69) like those of Weobley and Wigmore, each took name from a castle. Each of these honours is separately described in Domesday Book, and the omission of any reference to the castles of Kilpeck, Weobley, and Snodhill is probably due to nothing but the indifference of its compilers. Despite the number of these military lordships, King William himself was one of the largest landowners in the county in 1086, holding in demesne estates which had once belonged to King Edward, Queen Edith, his wife, and the Earls Morcar and Harold. The most valuable of these estates was the rich manor of Leominster, where a house of nuns, dissolved in 1046 because of the misconduct of its abbess, had existed in the 10th century. (fn. 70) The estates of longest standing in the county were the small fief of the monastery of St. Guthlac of Hereford and the large one of the bishop and his canons. (fn. 71) Like other ecclesiastical persons of his rank, the bishop of Hereford was required to supply knights when the king demanded them, and the series of original English charters granting land in return for knight-service begins at present with the document by which in 1085 Bishop Robert Losinga granted Holme Lacy to Roger de Laci for the service of two knights. (fn. 72) It is appropriate that Herefordshire should produce the earliest contemporary record of an enfeoffment for military service. The military organisation of the county had been one of the first tasks attempted by the Norman Government. By the date of this record, the work was complete in outline. The north and west of the county were protected by castleries, and on the south, 'Arcenefeld,' though Welsh in custom, had been brought under Norman lords. There is no county in which the military aspect of the Norman Conquest is felt more strongly than in Herefordshire.

F. M. STENTON.

Early Castles in Herefordshire

Herefordshire is perhaps the most important county in England for the study of the evolution of the early Norman castle. Its position on the Welsh marches and the particularly aggressive character of the Welsh princes immediately before the Conquest, rendered it a district of capital importance in the protection of the frontier. Professor Stenton in an earlier section has given the reasons for supposing that the castles of Hereford, Richard's Castle and Ewyas Harold were raised by the Norman 'men of the castle' under Edward the Confessor. Richard's Castle is almost certainly that referred to as Auretone in Domesday, and Ewyas Harold is referred to in the same record as having been re-built. Immediately after the Conquest the Earldom of Hereford was given by the Conqueror to the able and energetic William fitz Osbern, who fought in the right wing at Hastings. The new earl, in the circumstances detailed above, raised a series of castles throughout his earldom which he confided to certain Norman nobles to hold under him. The mention of castles in Domesday is quite fortuitous, but it so happens that out of a total of fifty throughout the country, four are mentioned in the present county of Hereford. Three of these were the work of William fitz Osbern and were held, at the time of the survey, as follows: Clifford by Ralph de Todeni, Ewyas Harold by Alfred of Marlborough, and Wigmore by Ralph de Mortimer. To these must be added no doubt a number of others not mentioned in the survey such as Ewyas Lacy (Longtown) held by Roger de Laci. Remains of the original earthworks survive at all or nearly all the places mentioned above and indicate a remarkable uniformity of type and construction, whether the castles were constructed before or after the Conquest. The main enclosure is commonly oval in form with a round mound or motte placed at the least defensible side of the perimeter; both motte and enclosure or bailey are generally defended by ditches. Occasionally advantage is taken of any acute natural configuration of the ground, but generally both mound and ditches are largely or entirely artificial. The existing castle at Clifford perched on a crag above the river Wye was preceded, probably, by two other earthen castles in the same parish; the earliest, at Old Castleton, is placed at a double bend in the river over 2 miles below the later castle; this site, on the flat land and liable to flooding, was probably found inconvenient at an early date, and the presence of an earthwork of similar form a short distance to the south at a hamlet called Newtown seems to imply an intermediate stage between the castle of William fitz Osbern and the existing castle which may perhaps be dated, by the stonework, to c. 1200. Again at Longtown the existing castle appears to have been preceded by a smaller motte and bailey work ¾ mile lower down the valley at Ponthendre, which is presumably the castle of Roger de Laci. Only at Wigmore is this normal type in any way departed from. Here the castle occupies part of an abrupt spur which has been perhaps partly scarped to form the motte (facing the base of the spur), and a ditch isolating the bailey from the point of the spur. The heavy labour of cutting a rock ditch between the motte and the bailey seems never to have been undertaken. There is no evidence of any earlier castle in the neighbourhood, so that here the existing site must be taken to represent that chosen by William fitz Osbern. The somewhat similarly placed castle at Ewyas Harold also lacks a ditch between the motte and the bailey (owing to the rapid fall in the ground) as also does Richard's Castle.

The next great period of castle-building is that of the Great Anarchy of King Stephen's reign, when large numbers of unauthorized or adulterine castles were raised all over the country. Some indication of the existence of castles of this age in Herefordshire is provided by the building of a group of churches which may be dated to the period 1140–1160. These churches were commonly placed immediately outside the bailey of the castle, and it is a fair inference that they were built in immediate sequence to the castle to serve the settlement that sprang up without its walls. We know that the church at Shobdon was built by Oliver de Merlemond about 1145, and though it replaced a timber church of St. Julian this is a purely Norman dedication, and might not antedate the stone structure by many years. The tump at Rowlstone is in close proximity to the church there, and Castle Frome church also suggests a date for the neighbouring motte and bailey earthwork. The same may apply to the church at Kilpeck, though here there was a much earlier church on the site, and the important castle may well date back to the 11th century. Other castles of this type, and probably of the first half of the 12th century, may be mentioned at Llancillo, Walterstone, Orcop, Dorstone, Mortimer's Castle Much Marcle, Huntington, Lyonshall, and Lingen. The numerous examples of isolated mounds or tumps, may also belong to this period, and the absence of the bailey may just possibly form the difference between the 'castles' and 'defensive houses' of Domesday. Two of these 'domus defensabiles' are mentioned in Herefordshire, and at one of these, Eardisley, there is now a motte and bailey of the usual type, to which the bailey may have been added later, or alternatively, the motte may have been added to the bailey.

The existing castle at Longtown, constructed in the angle of a rectangular earthwork, is paralleled at Cardiff, Carisbrooke, and Castle Acre. The rectangular works at Cardiff and Carisbrooke are known to be Roman, and there is, at any rate, a probability that excavation would demonstrate the Roman origin of the other two works. The alternative theory that this rectangular work at Longtown represents a village-enclosure is, however, supported by the presence of a somewhat similar, though much weaker, enclosure at Kilpeck, but the more normal form of such Norman town or village-planning appears to be represented by the semi-circular plans of Devizes and Pleshey, of which a trace may survive at Richard's Castle.

The earliest datable stone construction in the castles of Herefordshire is the square keep at Goodrich, which may be assigned to the middle or third quarter of the 12th century, though there was a castle here by c. 1100. There are traces of shell or cylindrical keeps on the motte at Llancillo and at Lyonshall; the former may be earlier than Goodrich keep, but the latter is probably of the 13th century. The polygonal shell-keep at Kilpeck is of the latter part of the 12th century, and the cylindrical keep at Longtown is of the end of the same century. The castles of Clifford, Snodhill, and Grosmont (Monmouthshire) are similar in general type, and may be assigned to the beginning of the 13th century. In these places the shell-keep is of much enlarged oval form, those at Clifford and Grosmont having flanking towers and a hall on one side; all three are entered by gatehouses.

The subsequent development of the stone castle need not detain us as it is not very well represented in the county—Goodrich, indeed, being the only first-class example. Pembridge and Wilton are much altered and Brampton Bryan is a mere fragment. Goodrich and Pembridge have points in common, including the placing of the gatehouse in one angle of the rectangular enclosure. Wigmore, though of great extent, preserves only shattered wrecks of its buildings. Sufficient remains to show that it was very largely reconstructed in the 14th century on the lines of the earlier structure.

A. W. CLAPHAM.

Architectural Survey of the County

Ecclesiastical Architecture.

Mediæval church architecture in Herefordshire does not, generally speaking, display the building-art in its highest form. As a purely agricultural county bordering on the Welsh hills, it never enjoyed more than a moderate degree of prosperity, and consequently was unable to rival the achievements of other districts of the country enriched by the wool or other trades. In addition to this the local building stone was not of the fine quality of that produced by the quarries of Northamptonshire, Somerset and elsewhere, and this inferiority is reflected in the local buildings.

On the other hand Herefordshire, in the 12th century, produced a school of Romanesque decoration, which for elaboration of detail and individuality of motif is hardly exceeded or even paralleled elsewhere. This decoration is widely diffused over the central part of the county and may be studied in situ in the churches of Kilpeck, Rowlstone, and Leominster, in the re-erected arch and doorways of the church at Shobdon, in the tympana of the churches of Fownhope, Stretton Sugwas and Brinsop, and in the fonts of Castle Frome, Eardisley, and Shobdon. The works of this school can be approximately dated by the known facts of the building of the church of Shobdon which was consecrated by Bishop Robert Bethune (1131–1148). This carving is distinguished by a profusion of interlacement and by the rendering of human and beast figures in a highly individualistic style. The costume of the subsidiary human figures at Kilpeck, Shobdon, and Leominster has been thought to represent the Celtic or Welsh trews with a close-fitting jerkin and a peaked cap of Phrygian type. The eyes of both human and beast-figures are rendered very large and full in form, and though the pose and action of the figures is stiff and unnatural it is nevertheless remarkably consistent and eminently decorative. The figure of Samson and the lion on the tympanum of Stretton Sugwas is reproduced with extreme fidelity, but on a minute scale on the W. doorway at Leominster; similarly the diaper with doves at Brinsop is reproduced, again on a much smaller scale, on one of the shafts at Shobdon. These and other equations of ornament are sufficiently exact to prove that the same workshop, if not the same hand, was employed on many or most of the works cited above. The general impression of this ornament is quite different from that of the normal Romanesque ornament of other parts of the country, and at first sight would suggest a Celtic influence from Wales with a strong Scandinavian element; its occurrence, however, on purely Anglo-Norman buildings, and its entire absence from the neighbouring Welsh counties, leads to the conclusion that it is the personal expression of some highly individualistic stone-carver and his pupils, not the result of cultural influence.

The architecture of the Cathedral of Hereford and of the church at Leominster presents certain features which render them remarkable and which must be touched upon in turn. The building of the bishops' chapel at Hereford, almost certainly by Robert de Losinga (1079–1095), marks a curious local break-away from the usual Norman traditions of English Romanesque. This chapel, now mostly destroyed, is precisely on the lines of the two-storeyed chapels of the Rhineland, and indicates a definite influence from that direction, perhaps due to the nationality of the bishop who appears to have come from Lorraine. The planning of the cathedral itself, begun by Bishop Reinhelm (1107–1115), indicates a continuance of this, possibly, German influence in the provision of the two subsidiary towers flanking the main apse, a feature not elsewhere represented in English work, while common enough in Germany. The arrangement of the E. end of the cathedral with the comparatively low arch opening into the central apse is also remarkable as being the earliest example of a type which was subsequently copied at St. John's Church, Chester, and at Llandaff Cathedral. The details of the 12th-century work at Hereford do not otherwise differ materially from Anglo-Norman Romanesque elsewhere, save that the broad responds between the bays of the choir seem to imply a system of roofing with broad arches across the main span, similar to those formerly existing at Chepstow.

Something of the same sort, on a very exaggerated scale, is perhaps implied by the curious and unique arrangement of the main arcades of the nave at Leominster. This nave originally consisted of three semi-solid bays divided by open arches, the solid bays being of greater thickness than the rest of the wall. Here again it seems likely that the solid bays were intended to support broad cross-arches, though what form of roof was designed to cover the open bays does not appear. However this may be, the scheme was definitely abandoned before the building of the existing triforium and clearstorey, which have no provision for a stone vault of any form.

The lesser Romanesque architecture of the county does not differ appreciably from that of the country at large. The proportion of churches either still retaining or formerly possessing apsidal terminations is considerably above the average, however, and foundations have been discovered of two circular churches in addition.

The late Romanesque of the county, of which the best example is the church at Ledbury, is distinguished by the almost invariable use of the scalloped capital with a concave outline to the component cones; this peculiarity has been thought to belong to a west-country school of masons whose members worked at Glastonbury, Worcester, St. Davids, Llanthony, and elsewhere.

The Gothic of the Herefordshire churches is not generally distinguished by richness of detail or delicacy of execution.

An exception, however, must be made for the churches of Abbey Dore and Madley. The former, which dates from the end of the 12th century with an early 13th-century addition, was the church of a Cistercian abbey, and is remarkable as being one of the three Cistercian churches in the country still partly in use, the others being at Holm Cultram (Cumberland) and Margam (Glamorgan). The church at Dore, however, was restored from a ruined condition in the 17th century.

The church at Madley is of a size and elaboration of detail which is altogether unusual in a parish church; this was due to the existence here of a figure of the Virgin which seems to have had some local notoriety, and to have attracted offerings. The apsidal chancel with the unusual crypt below it were in the course of erection in 1318.

A local peculiarity in some of the larger Herefordshire churches is the fairly frequent occurrence of the detached bell-tower. Most of these structures date from the 13th century, and examples still exist at Ledbury, Bosbury, Holmer, Garway, Richard's Castle, Pembridge, and Yarpole; some of these are partly of timber.

The almost excessive employment of ball-flower ornament on the central tower of the cathedral may be noted, as it was imitated in the outer N. chapel at Ledbury, in the S. aisle at Leominster and elsewhere.

Domestic Architecture.

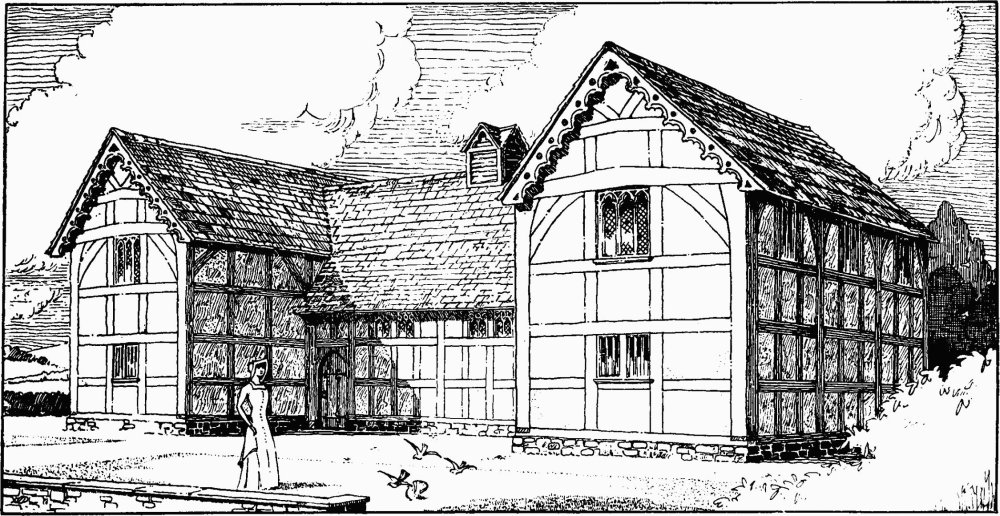

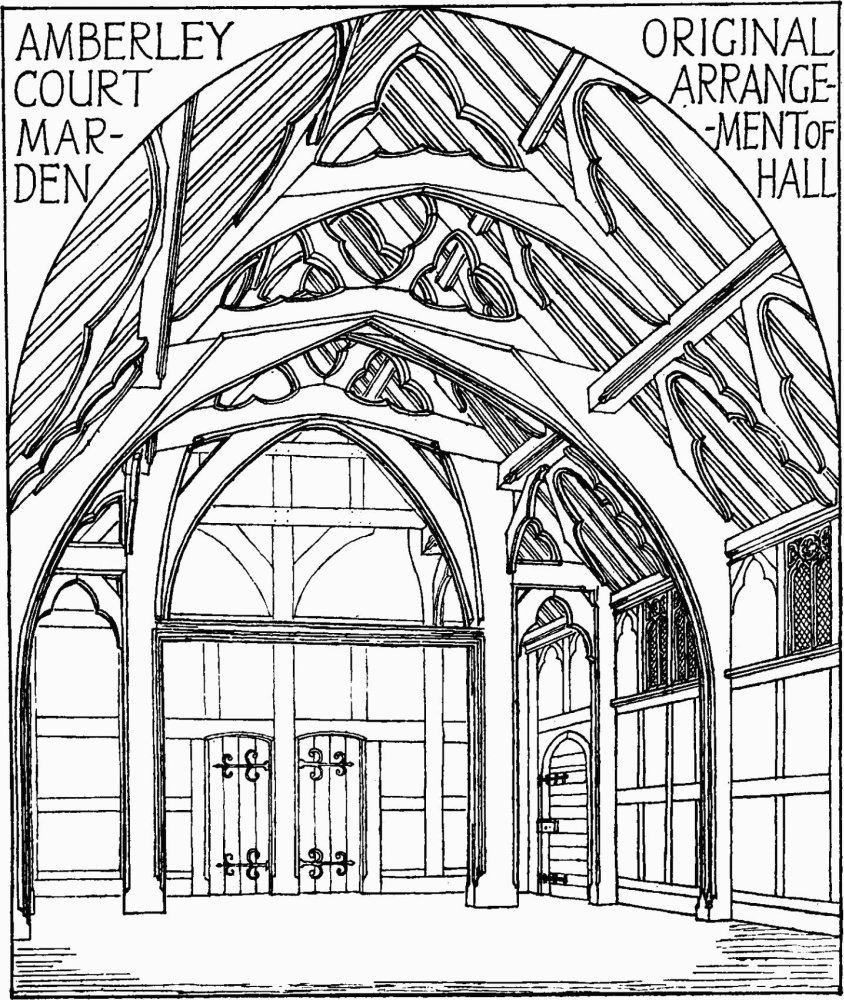

The interest of the domestic architecture of the county is chiefly centred in its timber-framed buildings, both of mediæval and later date. These structures, though not exhibiting any characteristics which are purely local, yet include a few buildings of outstanding interest and illustrate the timber building-tradition of the west of England. The great aisled hall of the palace of the bishops at Hereford is definitely a timber structure of the latter part of the 12th century. As such, it is perhaps the only surviving example in England having definite architectural features of so early a date. These features, it should be noted, reproduce, with some fidelity the mouldings and simpler decorations employed in contemporary stonework from which they are obviously copied. The aisled form of hall, here exemplified, is, however, not the normal type of early hall in Herefordshire, as it is in other parts of the country. Its place is commonly taken by the hall roofed in one span and having a spere-truss at the lower end, which is common to the adjoining counties. None of the surviving examples, however, appears to date from earlier than the 14th century. The accompanying diagrams (based upon the surviving remains at Amberley Court, Marden) show the general disposition of both the interior and exterior of a typical structure of this class. The spere-truss with its two side-posts carried down to the floor may possibly be a survival from the earlier aisled structure, the aisle-posts being retained only in the truss dividing the 'screens' from the body of the hall. However this may be the retention of this spere-truss is a marked feature of the 14th and 15th-century halls of the county, but in no case are there sufficient remains to indicate how the openings between the posts were filled in to form an effective screen, though in more than one instance evidence is left of the existence of a cross-beam at the springing of the main arch. It is possible that the normal screen was formed by the adoption of a movable panelled barrier under the main arch, leaving space at each side for a doorway. Such a barrier still exists under the spere-truss at Rufford Old Hall, Lancashire.

In the smaller and more remote houses in the county use continued to be made, throughout the Middle Ages, of the primitive crutch-truss, a form of construction very widely employed in the more backward parts of this and other countries. The crutch-truss consists of a pair of curved beams, resting on the ground, fixed together at the apex, and sometimes tied together, either at the level of the upper floor of the building or at a higher level. The roof itself is built up on these trusses which thus commonly project within the upper part of the building.

Timber-framed building of the 17th century is chiefly remarkable for the works of John Abel (1577–1674) who seems to have been a native of the county, and who was buried at Sarnesfield where he died at the age of 97. He is credited with the erection of the town halls of Hereford, Leominster, Kington, Weobley, and Brecon, and with less probability with that at Ledbury. The first of these, pulled down in 1862, was amongst the finest timber-framed buildings in the country. The town-hall at Leominster has fortunately been preserved, though removed from its original position; though far smaller than that at Hereford it is an admirable piece of ornamental timber-framing, and has features which are absent from the structure at Ledbury. According to Price (Historical Account of Leominster, 1795), Abel was given the title of one of the King's Carpenters for his services during the siege of Hereford in 1645. The same authority states that he made the woodwork for the church of Abbey Dore, restored by John, Lord Scudamore in 1634.

A. W. CLAPHAM.

Amberley Court Marden, Original Arrangement of Hall