An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in Dorset, Volume 4, North. Originally published by Her Majesty's Stationery Office, London, 1972.

This free content was digitised by double rekeying. All rights reserved.

'Sectional Preface', in An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in Dorset, Volume 4, North(London, 1972), British History Online https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/rchme/dorset/vol4/xxv-xxxix [accessed 17 April 2025].

'Sectional Preface', in An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in Dorset, Volume 4, North(London, 1972), British History Online, accessed April 17, 2025, https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/rchme/dorset/vol4/xxv-xxxix.

"Sectional Preface". An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in Dorset, Volume 4, North. (London, 1972), British History Online. Web. 17 April 2025. https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/rchme/dorset/vol4/xxv-xxxix.

In this section

DORSET IV

SECTIONAL PREFACE

Geological Map of North Dorset

In the preface, numbers in square brackets refer to the Plates; those in round brackets denote the Monuments in the Inventory.

Topography and Geology

The fourth volume of the Dorset County series, somewhat smaller than the preceding volumes, describes the ancient and historical monuments of thirty-four parishes in an area of 102 square miles lying on or near the N.E. boundary of the county, between its northernmost point and Cranborne Chase, and thence extending southwards to include the parishes of the Tarrant valley.

The underlying geological formation (map opposite) gives rise to two distinct geographical areas divided by the Chalk Escarpment, which here runs almost due N.–S. The Jurassic Beds in the western area are generally low-lying; most of the land is Kimmeridge and Oxford Clays, rarely exceeding 250 ft. in altitude. In only two places are there higher and more marked physical features. One, an outcrop of Corallian Limestone near the W. extremity of the area, forms a clearly defined westward-facing scarp, extending from N. to S. and rising to an altitude of 440 ft. The other, Duncliffe Hill, a massive Greensand outlier of the main escarpment, rises almost to 700 ft. above sea-level some 2 miles W. of Shaftesbury. The western area is drained by the south-westward flowing R. Stour, and its tributaries, the R. Lodden and the Filley, Chiverick, Manston and Fontmell brooks.

The eastern area comprises the Chalk lands of Cranborne Chase, defined on the W. by the 300-ft. high Chalk and Greensand Escarpment, which rises on Melbury Hill to a maximum altitude of 862 ft. above sea-level. Eastwards, on the dipslope, the land falls gradually to about 200 ft., where Eocene deposits overlie the Chalk. The dipslope is intersected by a series of southward flowing streams, giving rise to a rolling landscape of broad, open valleys with high, rounded interfluves. The smaller of these valleys, and also one major valley in Pimperne, are dry; the others have permanent watercourses.

Building Materials

Most of the building materials noted in Central Dorset occur also in North Dorset and the general remarks in the former volume (Dorset III, xxxv) apply also in the present area. In the Jurassic zone on the W., rubble and ashlar of Corallian Limestone are the commonest materials for the walls of all buildings. Original roof-coverings were of stone-slate or thatch, although many buildings have been re-roofed with other materials. In Gillingham, where the land is partly Corallian Limestone and partly Clay, all early buildings are of rubble, but brick appears to have come into use early in the 18th century. In Motcombe, where both Clay and Greensand are plentiful, older houses are of squared Greensand rubble; brickwork was being used as a 'show' material for façades [29] by about 1750. In the parishes which lie astride the Chalk escarpment, buildings are almost all of Greensand ashlar or squared rubble, occasionally with ornamental banding of flint; notable exceptions to this rule are the Roman villa at Iwerne Minster, which is wholly of flint [48], and a few 16th-century houses in the same parish and in Fontmell Magna which have timber-framed walls. Timber-framework, however, is rare in North Dorset and a 15th-century building at Tarrant Crawford (3), in the extreme S. of the area, is the only other example noted.

Above the escarpment, on the Chalk dipslope, the walls of 'vernacular' buildings are usually of cob, or of flint with rubble or brick quoins; roofs generally are thatched. A mansion erected at Chettle in c. 1710 is of brick [36], and several 18th-century brick cottages are found in the same parish, presumably because the kilns set up to make bricks for the great house continued to be worked for a time. Churches and other large buildings in the area usually have flint walls with dressings of Greensand ashlar; cottages at Tarrant Gunville have walls of reused ashlar, no doubt salvaged from the demolition of Vanbrugh's mansion at Eastbury, c. 1782. Lower down the Tarrant valley the commonest building materials are cob and flint, the latter with quoins of rubble or of brickwork. Heathstone is occasionally found in the S. of the valley.

Roman and Prehistoric Monuments

(See Distribution Map in end-pocket)

Roads

The Roman road from Badbury Rings to Bath traverses several parishes in the east of the area. It is reserved for description in the fifth volume, where the Roman roads of the county will be treated integrally.

Settlements and Enclosures

Twenty-two such sites are known in the area, nearly all of them levelled, or at least severely damaged by ploughing. The majority are enclosures, not certainly all settlements, ranging in size from one to twenty acres and so far undated by excavation or surface finds. Probably most of them are of the Iron Age, or at least are in the native Iron Age tradition, although some may well have continued in use in the Roman period or may even have been constructed then. All these sites lie on the Chalk, between 200 ft. and just over 400 ft. above O.D.; seven of them occupy spurs, a position much favoured by Iron Age settlements, the others are on or near hill-tops.

Of the sites which have yielded datable material, most lie on the Chalk, on or near hill-tops, and are comparable both in elevation and aspect with the undated enclosures. On the other hand the Roman villa, Iwerne Minster (15), on a site already occupied in the later Iron Age, lies in a valley-bottom on the Upper Greensand, and the Romano-British settlement Gillingham (100) lies on the top of a low ridge of Corallian Limestone. Only one site, the eleven-acre enclosure Pimperne (15), can be ascribed with certainty to the Iron Age alone, and probably to the earlier part of that period ; here, recent excavations have produced remarkably clear evidence of a large timber roundhouse similar to that of Little Woodbury, but without central posts. Presumably the hill-fort at Bussey Stool Park, Tarrant Gunville (32), is also of the Iron Age.

Five settlements have yielded evidence of both Iron Age and Romano-British occupation. Of them, only the Iwerne villa has been dated by large-scale excavations; the others are dated almost entirely by surface finds. At Iwerne, occupation was continuous from the later Iron Age to the 4th century A.D., and the limited evidence suggests that the same is true of the other sites. Morphologically the sites all differ to some extent one from another. Buzbury Rings, Tarrant Keyneston (16), comprises two roughly concentric enclosures, the inner enclosure containing the main occupation area. Tarrant Hinton (18) has two oval enclosures linked by a length of bank and ditch. At Tarrant Hinton (19) an open occupation area adjoins two or more enclosures. The settlement Chettle (14), now levelled by ploughing, appears to have been without enclosures. The extensive but sadly mutilated settlement on Blandford Race Down, Tarrant Launceston (14), has yielded no datable material, but is almost certainly Romano-British, possibly with Iron Age antecedents. Of exclusively Roman date is the large settlement on Barton Hill, Tarrant Hinton (17); it is as yet little understood, but it must surely be more than a villa.

Dykes

Seventeen dykes are known in the area, all on the Chalk; geographically they fall into two groups. In the north, in the parishes of Ashmore, Compton Abbas and Fontmell Magna, seven dykes, mostly crossdykes, lie on spurs and ridges of the higher ground along and near the edge of the Chalk escarpment. Each dyke consists of a single bank and ditch, between 30 ft. and 45 ft. across, overall, with the bank-top rarely more than 6 ft. above the ditch-bottom. An exception is Ashmore (14), where the ditch is up to 8 ft. deep and is separated from the bank by a wide berm. None of these dykes has been examined by excavation and only Ashmore (16), which is cut by a Roman road, bears any obvious relationship to another monument. Vestiges of 'Celtic' fields survive in the vicinity of the dykes, but as yet no settlements are known. The other ten dykes lie to the south on the lower, more gently rolling downland of the parishes bordering the Tarrant brook. Nearly all of them are linear dykes between 600 yds. and 2,000 yds. in length; many have been flattened or severely damaged by ploughing, but where they survive they too are of modest dimensions. They tend to lie nearer settlements, enclosures and 'Celtic' fields than do the seven northern dykes, especially Tarrant Rawston (5) and the group in Tarrant Keyneston (17–21). The dykes of the last named group, unlike the other dykes, consist of twin banks flanking medial ditches; they are clearly associated with the Iron Age and Romano-British settlement at Buzbury Rings and with the 'Celtic' fields surrounding it.

It is obvious that these dykes were originally boundaries, and from their dimensions it is probable that they were peaceful boundaries between estates or units of land. None of them has the dimensions of a frontier work like Combs Ditch (Dorset III, 313), or Bokerly Dyke (Dorset V), but some of the cross-dykes may have served to control movement along the spurs and ridges.

Flat Burials

In addition to the Bronze Age cremation cemetery in Tarrant Launceston, examined by C. Warne in 1840, which was probably flat, inhumation burials unmarked above ground have been found at four places in North Dorset. A burial in a lead coffin near Cann is certainly Roman, as are an unspecified number of inhumations near Melbury Hill, Melbury Abbas; the former burial was certainly on the Upper Greensand, the latter probably so. A single inhumation at Langton Long Blandford is probably Roman. Of greater interest, however, is a cemetery found in 1868 during the quarrying of the Corallian Limestone at Langham near Gillingham. At least one hundred extended inhumations were found, all with heads to the west. Their number and orientation, and the almost total lack of recorded grave goods, suggest affinity with several sub-Roman Christian cemeteries in eastern Somerset, all within forty miles of this site. (fn. 1)

Barrows

As in the two previous volumes, the barrows in each parish are described as far as possible in topographical order from S.W.–N.E.; barrow-groups are given names of local derivation.

Eight Neolithic Long Barrows are recorded in the area, all on the Chalk except for Gillingham (102), which lies on Corallian Limestone. The long barrows vary in orientation between S.S.E. and E.N.E. and are sited either on the crests of ridges or on slopes facing generally eastwards. They differ markedly in length: four are a little over 100 ft., one is nearly 200 ft. and three are over 300 ft.; the latter are situated in the adjoining parishes of Chettle and Tarrant Hinton. Generally the mounds are well preserved, except for Tarrant Hinton (25) which has suffered from heavy ploughing. Ploughing, too, has obscured most of the side ditches, but they are well preserved at Tarrant Hinton (24) and at Tarrant Rawston (6). At least five of the long barrows were opened in the 18th and 19th centuries, with comparatively little result as far as it is possible to tell from the inadequate surviving records of these activities.

There are at least one hundred and thirty Round Barrows in the area, but nearly three-quarters of them have been damaged or levelled, mainly by ploughing. They all lie on the Chalk, the majority between 200 ft. and 400 ft. above O.D., on the low rounded interfluves of the dipslope. Two-thirds of the barrows and eight of the nine barrow-groups lie in the adjoining parishes of Pimperne, Tarrant Hinton and Tarrant Launceston. The groups are small, the largest comprising thirteen barrows. The Telegraph Clump group in Tarrant Hinton is the only one to include a long barrow.

The round barrows are all bowl-barrows, where their form may be determined at all, except Pimperne (22) and Tarrant Hinton (41) which are double-barrows, and Tarrant Launceston (46) which is a discbarrow.

Several of the barrows have been dug into in the past, but such records of these activities as have been kept (chiefly of 19th-century date) are usually too brief to provide useful information; indeed it is seldom possible to relate an early excavation record with any certainty to an existing barrow. The excavations undertaken by S. and C. M. Piggott in 1938 on barrows in Tarrant Launceston are the only ones that have been adequately recorded; they yielded evidence of a variety of burials ranging from the late Neolithic to the Middle Bronze Age or later.

A small number of barrows appear from their contents, size or position to have pagan Saxon affinities. Three barrows in Tarrant Launceston, (17), (43) and (44), all on the parish boundary, have yielded burials which are probably pagan Saxon. Two groups of small mounds, now destroyed, Pimperne (31–35) and Tarrant Hinton (54), lay on either side of the parish boundary close to Pimperne Long Barrow; it has been suggested (Dorset Barrows, 125, 134) that they too are pagan Saxon.

Mediaeval Settlement

(See Distribution Map in end-pocket)

The pattern, siting and morphology of mediaeval and later settlement in North Dorset is largely determined, as already observed for Central Dorset, by the two distinct physical landscapes of the area.

The Jurassic Lands of the North-West

Generally, the settlements in this low-lying area are large nucleated villages, often surrounded by a scatter of outlying hamlets and farms. Geology to an exceptional degree has controlled the siting of the major, and also of many minor settlements. The spring-line at the foot of the Chalk and Greensand escarpments gives rise to a chain of nucleated villages from Iwerne Minster in the S. to Motcombe in the N.; among them, Shaftesbury alone is sited at the top of the scarp, probably because of its defensive role in Saxon times. To the W., the broad belt of Kimmeridge Clay is empty of major settlements; the two Orchards and Margaret Marsh, although now parishes, have never been more than scattered hamlets. The major villages of Gillingham and Milton-on-Stour owe their existence to river terraces. The Corallian Limestone escarpment, on the other hand, give rise to two chains of major settlements; one, at the junction of the dipslope and the Kimmeridge Clay on the E., extends from Todber in the S. to Bourton in the N.; the other, at the western foot of the scarp, includes Fifehead Magdalen and Buckhorn Weston. These settlements have no common plan and most of them are irregular concentrations of lanes and cottages.

The outlying farmsteads and hamlets result mainly from a process of secondary settlement associated with piecemeal clearance of the waste beyond the open fields of the nucleated villages; the process was certainly in operation before the 11th century. A remarkable example of piecemeal secondary settlement is seen in the Royal Forest of Gillingham, which extended in mediaeval times over the whole of what is now Motcombe parish and also over part of Gillingham parish. Hamlets and farms with small irregular fields in this area represent mediaeval encroachments along the edge of the Forest. The Royal Forest was finally disafforested in 1624 (see introduction to Motcombe, p. 48, and map [56]).

The Chalk Lands of the South-East.

Until recently, settlement on the Chalk has been largely confined to the valleys of the dipslope. The only exception is Ashmore, perched high on the downs and drawing its water from a pond; its siting, comparable with that of known Romano-British settlements in the region, may indicate that it too originated in the Roman period. Elsewhere the village plans, the earthwork remains of deserted settlements, and documentary evidence combine to show that the early mediaeval settlement-pattern consisted of chains of villages, hamlets and farmsteads spaced out along the bottoms of the valleys. In some cases, like Luton Farm in Tarrant Monkton, the original settlements have never grown; in others the settlements, formerly larger, have been reduced; yet others have developed extensively, resulting in long, linear villages like Farnham and Tarrant Keyneston. In narrow valleys the linear settlements consist of a single street parallel with the stream, as in Tarrant Gunville and Chettle; in wider valleys two parallel streets are sometimes found, one on each side of the stream, as in Tarrant Monkton. As noted before (Dorset III, xliii), these chalk-land settlements are always associated with narrow strips of land running back from the watercourse, on one or on both sides of the valley. The boundaries of the strips are often preserved as continuous hedge lines.

Mediaeval and Later Earthworks

As in Central Dorset, the monuments of North Dorset under this heading are divided into three groups: settlement remains, cultivation remains, and miscellaneous mediaeval and post mediaeval remains. In preparing this volume, the limitations on documentary research have been as before (see Dorset III, footnote on p. xliv).

Settlement Remains

Without excavation, only documents can show the periods of shrinkage and desertion of mediaeval settlements, and such documents as exist are generally vague in this matter. Nowhere has reliable evidence for a substantial reduction of population been found; in most of the sites, desertion appears to result from a slow process of shrinkage and gradual abandonment over a long period. Dated desertion occurs only at Tarrant Gunville, where cottages were removed early in the 19th century for the improvement of Eastbury Park. Almost all the settlement remains have the form of long closes bounded by low banks, with the house-site, where preserved, at the lower end of the close.

Cultivation Remains

Because of the geological background, fewer traces of mediaeval cultivation remain in North Dorset than in any other part of the county except the eastern heathlands (Dorset V). In the rolling downland of the Chalk dipslope, declivities are usually not steep enough for the development of strip lynchets; it is only in parishes along the escarpment that these features are found. In the low-lying Jurassic area of the N.W. the remains of mediaeval cultivation are almost always ridge-and-furrow. Much of this evidence has been destroyed, or is now being destroyed, by modern methods of agriculture.

Miscellaneous Earthworks

The earthworks of Shaftesbury Castle appear to be the remains of a temporary fortification of 12th-century date. King's Court Palace in Motcombe is of interest, being the remains of a 13th-century royal residence; its history and many details of its buildings are well recorded (History of the King's Works, II, 944–6). Extensive earthworks in Tarrant Gunville result from the abandoned formal gardens at Eastbury, laid out by Charles Bridgeman in the first half of the 18th century [72].

Mediaeval and Later Buildings

Ecclesiastical Buildings

The most important pre-conquest church in North Dorset must have been Shaftesbury Abbey, but it was rebuilt after the Conquest and nothing remains of the original structure; the museum on the site of the later church contains a few stone fragments [3] with interlace carving, perhaps from the Saxon building. Built into the N. wall of Gillingham vicarage are two fragments, of unknown provenance, with 9th-century interlace ornament. Until 1838 Gillingham parish church may have retained the nave arcades of a Saxon church, but if so they were destroyed in that year. At Todber the remains of a stone cross with interlace and other enrichment of the late 10th or early 11th century came to light in 1879 and have been re-erected in the churchyard [2]. An important carved stone from a cross-shaft of about the same period, formerly at East Stour, has recently been taken to the British Museum.

The late 11th-century Abbey Church of Shaftesbury, demolished at the Dissolution and now represented by little more than its foundations [60], was certainly the most important church of its period in North Dorset; it was a cruciform building with an apsed presbytery, apsed N. and S. chapels, and apsed transepts. The work of building continued in the 12th century with the construction of an aisled nave, the finished church being larger than either Sherborne or Wimborne. Excavation of the abbey has been confined to the area of the church itself and a small part of the cloister; nothing is known of the monastic buildings.

Iwerne Minster church, 5 miles S. of Shaftesbury and an ancient possession of Shaftesbury Abbey, appears to be of the mid-12th century; the original church was probably cruciform, and of this early structure there remain the nave, part of the N. transept, the N. aisle and a building on the S. which is likely to have been a tower; a S. aisle was added at the end of the century. Fragments of small 12th-century churches survive at Tarrant Crawford and Tarrant Rushton; Tarrant Gunville retains a section of early 12th-century arcaded decoration [8], discovered when the church was rebuilt in the 19th century, and reset. The nave arcade at Silton [6] is of the late 12th century.

In the 13th century the parish church of Tarrant Crawford [68] was remodelled and enlarged, doubtless in connection with the development of the abbey which had been established there at the end of the 12th century. The nuns' original cell may have been beside the old parish church, but there can be little doubt that a separate convent church was subsequently built on another site, in addition to the work undertaken at the parish church; the convent church, however, has disappeared altogether. The N. transept at Iwerne Minster [6] and the chancel at West Stour have 13th-century features.

In the 14th century a large chancel, which still exists [4], was added to the presumed Saxon nave at Gillingham. The churches of Fifehead Magdalen, Buckhorn Weston [33] and Stour Provost in the westernmost part of the area also date from the 14th century, and in the Tarrant valley Hinton and Rushton have significant remains of the same period. The tower of Iwerne Minster church [49] is distinguished 14th-century work.

As in other parts of the county, the 15th and 16th centuries saw many improvements to churches. A fine tower was built at Kington Magna [I]; that of Iwerne Minster was crowned with a spire. Fontmell Magna church was embellished with carved parapets [10] and also with a tower; Tarrant Hinton church was enlarged and partly rebuilt. Church towers were built at Stour Provost, Farnham and Compton Abbas [33]. St. Peter's at Shaftesbury [7] is largely of this period. At Silton a small N. chapel was built and the S. aisle was rebuilt. The tower of Tarrant Crawford church is probably of 1508, and the S. transept and S. porch of Tarrant Rawston [5] appear to be later 16th-century work.

During the 17th century no significant church building took place in the area. In the 18th century Tarrant Rawston and Tarrant Monkton churches were repaired and to some extent rebuilt, in each case with care to preserve the 'mediaeval' character of the building; other examples of the 18th-century 'Gothic' style are the east window in the church at West Stour and a window in the church at Tarrant Keyneston, now reset in the vestry.

Little early 19th-century church building occurs in the area; the church consecrated at Bourton in 1813 was pulled down and rebuilt in 1880. In 1838 an ambitious project of enlargement at Gillingham caused the destruction of the nave, presumed to have been Saxon; the spacious building which took its place was the first attempt in North Dorset at the revival of Gothic church architecture. St. Rumbold's at Shaftesbury and the nave of West Stour church were built in 1840. Essays in the Romanesque style at East Stour in 1842 and at Enmore Green, Shaftesbury [5] in 1843, yielded interesting results, and already in 1841 Gilbert Scott had demonstrated the possibilities of the Gothic style at Holy Trinity, Shaftesbury [63]. George Alexander's churches at Motcombe and Sutton Waldron [63], both of 1847, appear to profit from Scott's example; Sutton Waldron, indeed, recaptures the mediaeval style as successfully as any 19th-century church in the county.

Church Roofs

Mediaeval stone vaults occur only at Shaftesbury and at Silton, both of small size. The Shaftesbury vault [10] is in the W. porch of St. Peter's church and has lierne tracery with carved bosses of late 15th-century date; that at Silton covers the N. chapel and has fan tracery of c. 1500.

A 16th-century oak ceiling with fretted panels on moulded intersecting beams [66] survives at Stour Provost. At Silton the nave, S. aisle and S. porch have wagon roofs of c. 1500. In St. Peter's, Shaftesbury, the nave and N. aisle have low-pitched 16th-century roofs with moulded and cambered beams, and moulded wall-plates and ridge-beams; these members have recently been incorporated in a modern concrete roof.

Plain 18th-century barrel-vaulted ceilings are found in the churches at Tarrant Monkton and Tarrant Rawston.

Church Fittings Etc

Altars: Mediaeval stone altar slabs remain at Gillingham and at Todber.

Bells: The oldest bell in the area, the 4th at Iwerne Minster, is probably of the early years of the 14th century and from a London foundry (Dorset Procs., 60 (1938), 99). Three bells at Chettle are of c. 1350, as probably is a small bell at Gillingham with 'Gabreel' in Lombardic letters. The Kington Magna tenor, probably of the second half of the 14th century, has an invocation to St. George in crowned Lombardic letters. Interesting 15th-century bells include the 5th and 6th at Fontmell Magna, the 4th at Tarrant Keyneston, and the 2nd and 3rd at Stour Provost. The Salisbury bell-founders of the late 16th and 17th centuries, Wallis, Danton, Tosier and the Purdues, are well represented in the area (Raven, 149–154).

Brasses: There are only two notable brasses [14]. Langton Long Blandford has the inscription plate, figures and shield-of-arms of John Whitewood and his two wives, probably engraved soon after 1467 and preserved in a 19th-century indented slab. Pimperne has a rectangular brass plate in memory of Dorothy Williams, 1694, with a quaint representation of the soul rising from the death-bed; the engraver was Edmund Culpeper.

Chandeliers: Fifehead Magdalen church has four 18th-century hanging brass chandeliers, each with sixteen sconces on scrolled arms radiating from globular pendants [39].

Carved Stonework: Apart from the pre-conquest carvings mentioned above, the earliest architectural sculpture in the area is at Shaftesbury Abbey. Noteworthy in the large collection of carved fragments collected there during the excavations is the base of a small 11th-century Purbeck marble attached shaft, with cable enrichment and delicately carved cinquefoil brattishing (drawing, p. 61); there also are numerous simpler bases and voluted capitals from other small columns.

A carving on the lintel of the S. doorway in Tarrant Rushton church, depicting an Agnus Dei flanked by throned figures [8], is probably of the early 12th century. Of the late 12th century are the S. doorway and the chancel arch at Pimperne [51], both reset in the 19th-century church; in form the elaborately carved door-head resembles those of a group described in the preceding volume (Dorset III, xlviii); the chancel arch, with chevron ornament, springs from admirably carved shaft capitals [9].

The most notable 13th-century carving in the area is a small attached shaft with a stiff-leaf capital [9] and a hold-water base, set between two round-headed windows in the N. chapel at Iwerne Minster; the windows are typical of the 12th century and the conjunction of styles is perplexing.

Of the 14th century are moulded corbels with ball-flower enrichment supporting the twin arches leading to the chapel on the N. side of the chancel at Gillingham; externally the chancel has moulded string-courses similarly enriched, and a few 14th-century gargoyles.

Notable 14th-century stone carvings include small traceried panels [10] set in openings to squints in Tarrant Rushton church. Parapets at St. Peter's and at St. James's, Shaftesbury, include late 15th-century traceried stone panelling with bosses with heraldic and other devices. The parapet [10] reset in the N. wall of Fontmell Magna church, peopled with reliefs of armed men, also has heraldic devices and the letters of an inscription, now confused, which formerly included the date 1530. Several 15th and 16th-century church tower parapets are ornamented with carved gargoyles.

Communion Rails: The most noteworthy communion rails are in the parish church at Tarrant Hinton. Elaborately carved with flower-festoons and cherub-heads, and with turned and twisted balusters [21], they originally formed part of a larger set of rails made c. 1665 for Pembroke College chapel, Cambridge. They were transferred to Tarrant Hinton in c. 1880, when the chapel furnishings were rearranged.

Communion Tables: St. Peter's, Shaftesbury, has two interesting communion tables, neither of them now is in use as such; one has heavy bulbous legs with acanthus enrichment and carved rails with the date 1631 on a cartouche; the other is of c. 1700 and has arcuated rails, tapering legs with claw feet, and scrolled diagonal stretchers with a turned finial at the intersection. Tables of similar form have been noted at Winterborne Stickland and at Charlton Marshall in Central Dorset (Dorset III, l). Another notable 17th-century communion table is at West Stour [22].

Easter Sepulchre: One of the most important monuments in North Dorset is the finely carved stone setting for the traditional Easter arrangements in Tarrant Hinton church. Dating from c. 1536 it is embellished with Renaissance arabesques and other details, full of freshness and grace [77].

Effigies: The earliest effigy is a late 13th-century recumbent figure of a priest, discovered early in the 19th century on the site of Shaftesbury Abbey and reset in the S. porch of Holy Trinity church, Shaftesbury [15]. Buckhorn Weston has a 14th-century tomb with an interesting recumbent effigy of a man in civil dress [15]. A noteworthy tomb in Gillingham church has the recumbent effigies of Thomas and John Jesop (see Monuments and Floor-slabs, below).

Floor Tiles: An important collection of inlaid tiles of the 'Wessex school', dating probably from the second half of the 13th century, is preserved in Shaftesbury Abbey museum (drawings, pp. xviii, xxiii); other examples less well-preserved survive in situ on the floor of the abbey church and chapter-house. These tiles appear to have been manufactured locally; they are associated stylistically with the tiles made at Clarendon Palace, Salisbury, c. 1250. Specimens of similar tiles are preserved in Tarrant Rawston church.

Fonts: [11, 12] The most important font in the area is the 12th-century example at Fontmell Magna; its tub-shaped stone bowl is enriched externally in high relief with a meandering scroll, with birds among the branches. A similar font at Compton Abbas is either a modern reproduction or an original monument entirely recarved. Pimperne has yet another font bowl of the same form, carved in relief with tendrils and scroll-work, with large flowers in the interstices and with bands of pellets above and below; the sculpture is sharp and appears to have been extensively reworked, presumably in the 19th century; the 19th-century tent-shaped stone font-cover is interesting.

East Stour, Tarrant Hinton and Tarrant Monkton have plain 12th-century fonts with square bowls with shallow round-headed panels on the sides, each bowl raised on a stout centre shaft and four small corner shafts. The parish church of Cann, dedicated to St. Rumbold and situated in Shaftesbury, has a well-preserved font of c. 1200, with a stout cylindrical stem, and a scalloped capital incorporated with the base of the bowl. Plain 14th-century fonts are found at Margaret Marsh and Motcombe. Buckhorn Weston, Stour Provost and St. Peter's at Shaftesbury have octagonal 15th-century fonts with trefoil-headed panelling on the sides. An unusual font, probably of 17th-century date, with a tub-shaped bowl, reeded in the upper part and gadrooned below, on a cylindrical shaft with octagonal mouldings above, and below, has recently been installed in the Congregational chapel at Shaftesbury; it came to light during the demolition of the Shaftesbury Poor-Law Institution and its history is unknown. Ashmore and Farnham have 18th-century stone fonts with baluster-shaped stems. At Fifehead Magdalen an 18th-century baluster supports a 15th-century bowl.

Gallery: A panelled gallery-front, formerly at the W. end of the nave in Buckhorn Weston church (Hutchins IV, 117), appears to be of the 18th century; its six panels, with paintings of saintly figures, a Nativity and two landscapes, have been reset on the tower walls.

Glass: A few fragments of mediaeval stained glass survive in Margaret Marsh and Tarrant Crawford churches. Holy Trinity, Shaftesbury has a small stained glass panel with an epitaph of 1646, reset and extensively restored. A glass reliquary unearthed at Shaftesbury Abbey in c. 1902, dating perhaps from the 9th–11th century, though it may be later, is now in Winchester Cathedral (D. B. Harden in Ant. J., XXXIV (1954), 188).

Images: At Buckhorn Weston church a small mediaeval figure, of stone, much eroded, is set in a niche in the gable of the S. porch. Reset in the S. aisle at Motcombe church is the lower part of a late mediaeval figure, probably the heavily draped legs of St. Catherine of Alexandria in traditional posture with an emperor as her footstool [15].

Lecterns: [13] Buckhorn Weston church has an oak lectern with a turned shaft and an inclined desk to which is chained an incomplete copy of Reliquiae Sacrae Carolinae, presented to the church in 1696. At East Stour the lectern desk rests on the wings of a finely carved pelican-in-piety [21], perhaps a finial from an 18th-century sounding-board (cf. Charlton Marshall, Dorset III, 58). It has been thought right to include in this inventory the unusual art-nouveau lectern at Tarrant Hinton, dated 1909.

Monuments and Floor-slabs: The earliest named funerary monument in the area is the floor-slab from the grave of Alexander Cater, with an inscription in Lombardic capitals, found during the excavation of Shaftesbury Abbey and now in the abbey museum; it appears to be of the late 14th or early 15th century. From the same site comes the floor-slab of Thomas Scales, 1532, with an incised black-letter inscription. The epitaph of Thomas Daccomb, rector of Tarrant Gunville, 1549–1567, with deeply cut Roman lettering [23], is reset in the S. wall of the church.

Noteworthy 17th-century monuments include that of the brothers Thomas and John Jesop, 1615 and 1625, in the N. chapel of Gillingham church [42]; it comprises a mural table-tomb with the brothers' effigies side-by-side, Thomas under a wall-arch with his epitaph, now gone, painted in a small panel, John towards the front of the table-tomb under a separate stone archivolt, with his epitaph on a marble tablet suspended from the keystone [23]. Other 17th-century monuments include the glass panel of William Whitaker, 1646, and the heavily enriched cartouche [18] of John Bennett, 1676, both in Holy Trinity, Shaftesbury. The stone wall-monument of Robert Fry, 1684, in Iwerne Minster church [16], has carving of distinguished quality. The most important funerary monument in North Dorset, however, is the grand work [65] by Nost in Silton church, in memory of Sir Hugh Wyndham, 1684, in which a statue of the judge, flanked by mourning figures, stands under a rich canopy supported on spiral columns; the monument was transferred in 1869 from the chancel to a newly-built niche on the N. side of the nave.

An interesting 18th-century wall-monument is that of Sir Henry Dirdoe, 1724, in Gillingham church [17]; it is signed by John Bastard, the architect of Blandford Forum parish church (Dorset III, 19). Another fine wall-monument at Gillingham is in memory of Frances, 1733, the youngest of Sir Henry Dirdoe's ten daughters [43]. The most impressive 18th-century wall-monument in the area is that of the family of Sir Richard Newman in Fifehead Magdalen church [41]; by an unknown sculptor, it is of white and coloured marbles and has admirable busts of the baronet, his wife and son, and portrait medallions [20] of his three daughters; it occupies one wall of a 'chapel' on the N. side of the chancel and appears to have been erected some time between 1747 and 1763. Other noteworthy 18th-century wall-monuments are those of Samuel and Ann Clark, 1761, 1764, in Buckhorn Weston church [17], and of Elizabeth and George Chafin, 1762, 1766, in Chettle church [38].

Paintings: Tarrant Crawford church has wall paintings of the 14th and 15th centuries, including a series of early 14th-century panels depicting the acts of St. Margaret of Antioch, and a beautiful Annunciation of about the same date [67, 69]. Buckhorn Weston church has some 18th-century panels (see Gallery).

Plate: The paten at Buckhorn Weston [24], one of only three pieces of pre-reformation church plate to survive in Dorset, dates perhaps from between 1510 and 1520 (Nightingale, 85); it is punched with a mark having a circle in which is a cross with a pellet between each limb. The same parish has the oldest communion cup remaining in North Dorset, with the assay mark of 1562. Of numerous Elizabethan cups, that of Gillingham [24] is important for its large size and also for giving the name by which a group of similar vessels, by the same anonymous silversmith, is known (Dorset III, liii); the Gillingham vessel is the earliest and that at Tarrant Monkton [24] is the latest of this group. Gillingham also has two fine silver flagons, one [25] with the assay mark of 1681, the other of 1735.

Royal Arms in churches: [27] The three-dimensional representation of the arms of James I in Gillingham church, carved and painted with equal virtuosity on both front and back, is the oldest and also the most magnificent example in the area [Frontispiece]. St. James's, Shaftesbury, has a well-carved cartouche of the Stuart royal arms, designed to be seen from one side. Wooden panels painted with the arms of the Stuart kings are found at Motcombe, Kington Magna, Stour Provost and Todber. Other churches have panels painted with royal arms of the Hanoverian period, notably Ashmore, Holy Trinity in Shaftesbury, Iwerne Minster and Tarrant Rushton; the Shaftesbury example is signed 'M. Wilmot, 1780', that at Ashmore 'K. Wilmot, 1816', but they are closely similar in style. A pleasing 19th-century example occurs at Bourton.

Tables of Creed, etc.: Recently rediscovered and now reset in the chancel of Silton church are two slabs of Purbeck marble carved with the Lord's Prayer and the Creed, with well-proportioned and well-spaced lettering; the inscriptions appear to be of the late 17th or early 18th century [23]. St. Peter's, Shaftesbury, is the only church in the area to retain an 18th-century reredos with shaped panels inscribed with Decalogue, Lord's Prayer and Creed [7].

Woodwork in churches: In addition to the communion-rails and communion-tables already discussed, North Dorset churches contain some other notable woodwork: Gillingham parish church retains a series of oak benches, probably of the 16th century, many with carved bench-ends with blind tracery and poppy-head finials, others square-headed [22]; the backs of some of these seats are formed with oak panels carved to represent trefoiled niche-heads with elaborately crocketed finials. Similar panels are reused in the communion-table at Gillingham, and in a gallery front in the church at West Stour. St. Peter's church, Shaftesbury, has a few 15th-century square-headed bench-ends with blind tracery decoration; it also possesses a small early 17th-century oak alms-box attached to the wall, with a bracket below, with foliate carving and an inscription 'Remember the Poore'.

Several churches retain polygonal oak pulpits of 17th and early 18th-century date [13], with panelled sides, some with chip-carving or with moulded rails; an example at I werne Minster has neat reticulate carving on the panels.

Reset in the tower archway at Fontmell Magna is a 16th-century oak screen with linenfold panels below and traceried open woodwork above, enclosing busts in wreath surrounds (drawing, p. xii). The same church has ten early 17th-century carved oak panels incorporated with modern woodwork to form a closet.

Public Buildings

There are few public buildings of note in the area. Shaftesbury Town Hall [61], in the revived Gothic style, dates from 1826–7 and appears originally to have comprised open arcaded market loggias in the ground and basement storeys, and rooms for civic purposes on the upper floor, but at a later date, probably in 1879 when a clock-tower was added, the arcades of the upper loggia were filled in to provide additional indoor accommodation. Gillingham retains a small early 19th-century stone lock-up, rectangular on plan.

The Free School of Gillingham, mentioned by the Commission for Charitable Uses in 1598, is represented by a room with a late 16th-century ceiling in a house with no other datable characteristics near the parish church. Nineteenth-century schools are noted at Ashmore, Melbury Abbas, Motcombe [28], Stour Provost and Shaftesbury.

Almshouses noted at Sutton Waldron and at Shaftesbury are of the 19th century and of small architectural importance. At Motcombe a late 17th or early 18th-century range of cottages (13) is called 'The Old Workhouse', but its history is not recorded. The large 19th-century Poor Law Institution at Shaftesbury (99) has recently been demolished.

Domestic Buildings

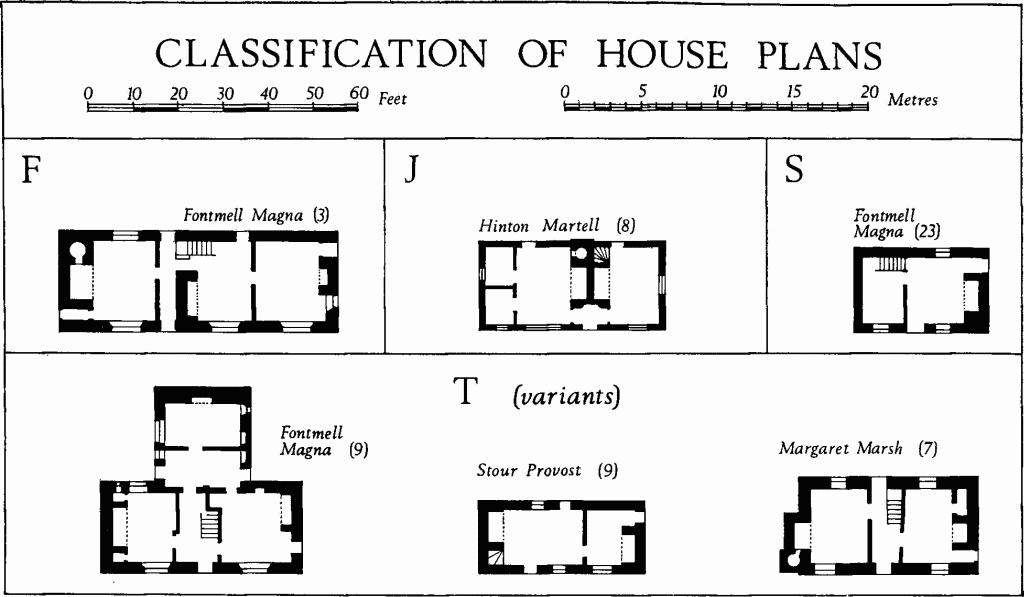

In volume II of the Dorset Inventory, to lighten the task of cataloguing a multitude of 16th to 18th-century 'vernacular' dwellings, a system of classification of typical ground-plans was provisionally set out (Dorset II, lxi-lxiv). The system was adopted in volume III and is again used in the present volume. For explanation of the several classes of plan the reader is referred to volume II, to the Inventory of Cambridge County (West Cambridgeshire, xlv-xlviii), and to P. M. G. Eden, in East Anglian Studies (1968), pp. 72–88. In the present volume the plan-types most commonly found are as follows:

Class F comprises a range of three rooms and a through-passage, with a fireplace in the middle room (hall) backing against the through-passage. A smaller fireplace often occurs on the gabled end-wall of the room (parlour) adjoining the middle room. The third room, separated from the middle room by the through-passage, is for service and is sometimes sub-divided (pantry, buttery, kitchen etc.).

Classification of House Plans

Class J houses are often more modest than those of class F, having a similar three-unit plan, but without the through-passage. Few examples survive in North Dorset.

Class S, the commonest type of 'vernacular' dwelling found in the area, consists of two rooms: a general living-room with an open fireplace set against one gabled end-wall of the range, and a room at the other end which may combine the functions of service-room and entrance-lobby, or it may be an unheated parlour.

Class T, distinguished by having a chimney-stack on each gabled end-wall and none in the middle of the range, is in general a later form than those described above; in North Dorset the plan became common in 18th-century building, but earlier was not often used. Occasionally the T-class plan has an original wing at the rear of the range.

No complete example of a mediaeval dwelling place survives in North Dorset. 'King's Court Palace', a 13th-century royal hunting-lodge in the Forest of Gillingham, is now a rectangle of earthen mounds and ditches (Motcombe (20)). Of the Benedictine nunnery at Shaftesbury, once the richest in the land, practically nothing remains except the foundations of the church. The Cistercian nunnery at Tarrant Crawford is represented by the flint and stone outer walls of a small mediaeval building, presumably some part of the former abbey, with a timber-framed upper storey perhaps of somewhat later date. A cottage at Todber (5) incorporates part of a 15th-century building, but the remains are insufficient for analysis. At Margaret Marsh, a remote and secluded village where several interesting early farmhouses survive, Higher Farm (4) is of 15th-century origin; from the remaining parts of its original roof it appears to have comprised a small two-bay hall with an open hearth, with service rooms perhaps in two storeys at one end and presumably with a parlour at the other end, although all traces of the latter have gone. The construction of a central chimney-stack and the chambering-over of the hall in the 16th century have, as usual, resulted in a class-F plan. Margaret Marsh has interesting 16th-century farmhouses at Church Farm (2) and at Gore Farm (7), the former with an unclassified plan, the latter of class T. A small town house at Shaftesbury (81) with a class-F plan is probably of c. 1500.

Noteworthy 16th-century domestic buildings include Cross House, Fontmell Magna (9), in which the plan is a version of class T, with an original wing set at right-angles at the rear of the class-T range. It is not clear at Cross House if the wing was designed to contain a parlour, or service-rooms as at present, but in a comparable house at Shaftesbury (77) the rooms on both floors of the wing were clearly the best rooms in the house, having elaborate chimneypieces, carved panelling on the walls and an enriched ceiling; many of these features were destroyed in recent 'improvements', but they are recorded in the Commission's files. At Hope Farm, Buckhorn Weston (2), an original rear wing again appears in a 16th-century house, but this time in conjunction with a class-J plan.

An interesting early 17th-century farmhouse is found at North End Farm, Motcombe (3), formerly called 'Easthaies' and noted by that name on a map of c. 1624. The plan clearly derives from the mediaeval kitchen-hall-parlour arrangement, evolved through the class-F plan, but further formalised by the removal of the hall fireplace and the staircase to a turret at the rear of the range. Great care has been taken in the design of this house to achieve symmetry in the main elevations [53], providing a nice example of the application of classical principles to a building which in other respects retains traditional mediaeval characteristics. At Iwerne Minster (7), 'The Chantry' provides another example of early 17th-century innovation. Basically the plan is the humble class I (see Dorset II, lxiii), enlarged to make it suitable for a well-to-do owner, and with a comparatively spacious staircase accommodated in a projecting wing; advantage is taken of the sloping terrain to site the service rooms in a half-underground lower storey. Again the designer has been at pains to achieve a symmetrical elevation [52].

Lower Hartgrove Farm, Fontmell Magna (18), has an unusual L-shaped plan in which the original function of the rooms is perplexing; the presence of two original staircases and perhaps even of two ovens implies occupation by two families, even though there is no solid wall to divide the tenements. Church House, Stour Provost (4) is a good specimen of a superior class-F house in which the kitchen and parlour are defined on the main front by gabled projecting bays. A town house in Shaftesbury (102) has an unusual plan, a variant of class F wherein the positions of parlour and service-rooms are interchanged. Lastly among 17th-century houses may be mentioned a handsome farmhouse at Lower Farm, Kington Magna (7), which has a sophisticated symmetrical façade with classical embellishments [53]; the house has been gutted and the plan is lost, but the two end-wall chimneystacks imply that it was of class T, with a projecting wing at the back for the main staircase, as in Motcombe (3).

The most important 18th-century house to survive is Chettle House [36], a large building of c. 1710 with a baroque plan, almost certainly by Thomas Archer; although the house was remodelled in 1846 and again in 1912 the elevations are as originally designed, except in one particular, and the house retains a fine 18th-century staircase. Of even greater importance than Chettle was Eastbury (Tarrant Gunville (2)), a vast baroque mansion by Vanbrugh, built between 1717 and 1738. Most of the building had been pulled down by the end of the 18th century and there remain only some relatively minor parts of two stable ranges, adapted to form a smaller country house [70], also a splendid archway [80], the park gateway [70], minor fragments of buildings, and traces of the 18th-century gardens designed by Bridgeman. West Lodge, Iwerne Minster (3), a house with a tetrastyle façade [44], is of 18th-century origin if not earlier, but enlarged and much altered during the second half of the 19th century. Smaller 18th-century houses in the area include Pensbury House, Shaftesbury (126); Higher Langham House, Gillingham (59); and Gunville House, Tarrant Gunville (3). Comfortable 18th and 19th-century parsonages are noted at Ashmore (3), Pimperne (4) and Shaftesbury, St. James (100), also [74] at Tarrant Gunville (4) and Tarrant Hinton (4). (fn. 2)

Of large 19th-century houses in the classical style only two fall within the Commission's purview: Fifehead House, Fifehead Magdalen (5), of 1807, and Langton House, Langton Long Blandford, of 1827–33. Both houses have been demolished, but the former [44] was recorded before demolition and is described in the inventory. We give no account of Langton House, (fn. 3) but the stables and other outbuildings are recorded. Wyke Hall, Gillingham (58) incorporates a small 17th-century house, but the greater part of the building is of 1853 and later.

Fittings in Secular Buildings

Ceilings: Higher Farm, Margaret Marsh (4), supplies evidence of an early type of ceiling in the form of wattles fastened to the under side of the common rafters in the roof of the 15th-century hall. The hall is now chambered over and ceiled at a lower level than originally, and the early ceiling is preserved in the roof-space.

Few 16th-century moulded plaster ceilings are found. An example occurred at Ox House, Shaftesbury (77), where the ceiling of the chamber in the N. wing had embossed sprays of foliage and Tudor roses in the angles of the moulded cornice, but this ceiling perished during recent 'improvements'. A fragment of an enriched ceiling of about the same date occurs in an 18th-century cottage at Bourton (21); it has embossed corner-pieces representing pomegranates, and strips of raised vine-scroll decoration on the margins; pieces from a similar ceiling, possibly the same one, are reset in a cottage at Gillingham (75).

A plaster ceiling at Abbey House, Shaftesbury (89) is moulded in the late 16th-century manner with vine-scrolls, roses, thistles and various kinds of foliage; the same ceiling, however, includes foliate scrolls of 18th-century aspect, suggesting that the whole work may be comparatively modern, possibly of the school of Ernest Gimson. If Chettle House had any 18th-century plasterwork it has perished, and all the enriched ceilings in the house today are of mid 19th-century date.

Moulded or chamfered ceiling beams with corresponding wall-plate cornices, often intersecting to form ceilings of four, six or nine panels, are found in many 16th or 17th-century farmhouses in the area; the examples at Gore Farm, Margaret Marsh (7), have elaborate mouldings.

Doorways: A mediaeval stone doorway with a two-centred head remains, blocked up, in a cottage at Todber (5); no other mediaeval doorway survives in a secular building in North Dorset. The traditional stone doorway with a pointed head, modified stylistically first to a four-centred form and later to a shallow triangle, persisted well into the 17th century in stone-built dwellings in this area. The four-centred door-head from Tarrant Hinton rectory, with a 16th-century inscription (Hutchins I, 318), has been reset in the stable-yard of the house, rebuilt c. 1850. An early example of a square-headed doorway of classical form is seen at Lower Farm, Kington Magna (7), a late 17th-century building [53]. Among 18th-century houses, Higher Langham, Gillingham (59), and Pensbury House, Shaftesbury (126), have dignified doorways with pediments etc. in classical style.

Fireplace Surrounds: The earliest decorated fireplace surround in the area is in a 16th-century cottage (5) at Fontmell Magna. It is of oak, with a moulded four-centred head, and probably with continuous jambs although the latter are obscured by modern fittings; the spandrels of the head are filled with triangular panels of foliate carving, one of them incorporating the monogram IP. A 16th-century stone fireplace surround with trefoil and quatrefoil panelled decoration is in an inn at Shaftesbury (20). Two interesting early 17th-century chimneypieces were formerly at Ox House, Shaftesbury (77); their stone surrounds with ogee-moulded and hollow-chamfered four-centred heads and continuous jambs ending at shaped stops, of mediaeval pattern, were surrounded by plain friezes and projecting stone mantelpieces with classical mouldings; the stone jambs were flanked by Ionic pilasters of carved oak supporting panelled overmantels with arabesques, coupled colonettes and vine-scroll friezes. Elaborate early 17th-century carved oak overmantels are found at Wyke Hall, Gillingham (58), and at Chettle Lodge, Chettle (3), both of them brought from elsewhere. In Church House, Stour Provost (4), the chamber over the S. parlour retains a small original stone fireplace of c. 1600 with a moulded four-centred head, continuous jambs and shaped stops. At Diamond Farm, Stour Provost (5), the parlour has a fine 17th-century stone fireplace surround with a moulded four-centred head composed of large voussoirs. The hall in the same house has an open fireplace with a deep oak bressummer, slightly cambered and with an ovolo-moulding, and stone jambs with the same moulding.

The Old House, Gillingham (76), retains a 17th-century stone fireplace with a frieze carved in low relief and a moulded stone mantel-shelf with classical enrichment; Wyke Hall, Gillingham (58), has a stone fireplace of perhaps somewhat later 17th-century date, with rather more correct classical features, but retaining a 'mediaeval' four-centred head and shaped stops in vestigial form. Well-proportioned 18th-century stone fireplaces with good classical details are noted at Pensbury House, Shaftesbury (126), and at Higher Langham House, Gillingham (59). Fireplaces, overmantels, doorcases and other carved fittings of 18th-century date in the late 18th-century house at Eastbury, Tarrant Gunville (2), are thought to have been brought from Yorkshire during the 19th century. A late 18th-century fireplace and overmantel at Barton Hill House, Shaftesbury (38), is said to have been salvaged from William Beckford's ' Fonthill Abbey '.

Staircases: The 17th-century circular example at North End Farm, Motcombe (3), is probably the earliest domestic staircase to survive in N. Dorset. Other noteworthy 17th-century staircases with turned oak balusters and stout newel-posts with ball finials occur at Holyrood House, Shaftesbury (92), at 'The Chantry', Iwerne Minster (7), and at Great House, East Orchard (5); Ox House, Shaftesbury (77), formerly had a good example with vase-shaped finials. Houses at Shaftesbury (37) and at Chettle (4) have 17th-century staircases in which the balustrades are formed with flat boards profiled to resemble balusters.

The most impressive staircase in the area is that of c. 1710 in Chettle House [40]; a central upper flight which formerly doubled back from the half-landing was removed in 1845, but in other respects the original woodwork is little altered. The staircase at Chettle Lodge, Chettle (3), closely resembles that of Chettle House and is probably of the same date; so also is the staircase in a house in Shaftesbury High Street (14). An early 18th-century staircase with spirally-fluted balusters, bolection-moulded panelling and a dog-gate occurs at Adcroft House, Bourton (4), and another noteworthy 18th-century example is found at Abbey House, Shaftesbury (89). The fist-shaped handrail volute noticed several times in Central Dorset (Dorset III, lxii) is not found in this area.

The staircase at Fifehead House, built in 1807 and demolished in 1964, had oak steps, a mahogany handrail, and a balustrade with iron uprights enclosing delicately wrought panels of foliate scroll-work cast in lead.