An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in Dorset, Volume 3, Central. Originally published by Her Majesty's Stationery Office, London, 1970.

This free content was digitised by double rekeying. All rights reserved.

'Sectional Preface', in An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in Dorset, Volume 3, Central(London, 1970), British History Online https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/rchme/dorset/vol3/xxxv-lxii [accessed 30 April 2025].

'Sectional Preface', in An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in Dorset, Volume 3, Central(London, 1970), British History Online, accessed April 30, 2025, https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/rchme/dorset/vol3/xxxv-lxii.

"Sectional Preface". An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in Dorset, Volume 3, Central. (London, 1970), British History Online. Web. 30 April 2025. https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/rchme/dorset/vol3/xxxv-lxii.

In this section

SECTIONAL PREFACE

In the preface, numbers in square brackets refer to the plates; those in round brackets denote monuments in the Inventory.

Topography and Geology

The part of Dorset which is described in this volume has an area of some 260 square miles and is divided into two distinct and almost equal parts by the Chalk escarpment of the Downs, which traverses it from S.W. to N.E. The scarp varies in height between 200 ft. and 500 ft., reaching its maximum altitude on Bulbarrow Hill, over 900 ft. above sea-level. The dip-slope of the escarpment falls S.E. to little more than 100 ft. at Tincleton in the S. and at Spetisbury in the E.; it is dissected by a series of streams which produce a rolling landscape with deep valleys and narrow interfluves. Erosion at the head of some valleys has resulted in large combes or basins, as at Lyscombe and Delcombe Bottom; similar erosion at Melcombe Horsey has cut through the scarp. In the extreme S., small outcrops of Reading Beds, the fringe of the S. Dorset Eocene deposits, overlie the Chalk and give rise to areas of heathland in the parishes of Tincleton and Puddletown.

To the N. of the escarpment the Vale of Blackmoor is almost entirely composed of bands of clays, sands and limestones of the Jurassic Beds, at altitudes between 150 ft. and 450 ft. above sea-level. At the foot of the escarpment is found the usual outcrop of Gault and Greensand; beyond this lies a band of heavy Kimmeridge Clay and this is succeeded by a narrow strip of Corallian Limestone and Sand which, especially in the N., gives rise to a low but prominent ridge. Further N.W. the Corallian belt gives way to a broad band of the underlying Oxford Clay, beyond which a narrow zone of Cornbrash Beds rises gently to the Fuller's Earth escarpment. The whole area is drained by small streams, mostly flowing N. from the foot of the Chalk escarpment to the River Stour; the latter flows generally south-eastwards, close to the N.E. boundary of the area under review and passes through the Chalk escarpment in a narrow gorge at Blandford Forum.

Building Materials

The varied geology of Central Dorset provides a multiplicity of building materials; among them, Corallian Limestone, common Greensand, Forest Marble, Flint, Chalk and Clay. Also within easy reach are Ham Hill stone, Greensand of superior quality, Heathstone, and Purbeck and Portland stones.

Choice of material in building naturally depends on the combination of such factors as local availability, the quality of the intended structure and ease of communication at the time of building. Before the 18th century, small domestic buildings were made of the materials that lay nearest to hand; cottages in Chalk districts were of chalk cob or, where the chalk was good enough, of clunch rubble banded with flint; cottages near the foot of the escarpment were of Greensand rubble, sometimes with flint banding; those of the Limestone area were of rubble and ashlar. On the other hand, the builders of churches and larger houses, with money to spend on appearance and solidity, brought materials of higher quality such as Ham Hill stone and Heathstone from further afield.

Although Corallian Limestone occurs in a broad outcrop running S.W.–N.E. across the N. part of the area, good building stone is confined to the vicinity of Marnhull and further north. In the mediaeval period it was not generally used in churches, except in the immediate vicinity of the quarries; Milton Abbey, however, is an exception to this rule. With the improved communications of the 19th century the material was used at much greater distance from the quarries, as in the rebuilt nave of Okeford Fitzpaine church. In secular architecture, where stone of poorer quality is acceptable, limestone rubble was more widely used and it is found in mediaeval buildings over the whole limestone outcrop, and even in the adjacent clay region.

Greensand in Central Dorset is not of very good quality and the local material is mainly used as rubble and squared rubble in lesser buildings. When good quality Greensand ashlar is found, as in the 15-century church towers of Child Okeford, Okeford Fitzpaine and Durweston, the material is probably from the Shaftesbury region.

Forest Marble, a rather rubbly, flaggy limestone, occurs in the extreme N.W. of the area; it is used locally for rubble walls at Stalbridge. In stone-slated roofs its use is more widespread.

Flint occurs only in conjunction with Chalk; it may be used in rough nodules, or split to give a fairly smooth face, or knapped to allow close jointing. Flint walling must be consolidated with quoins and dressings of other materials. Before the development of brick, Chalk clunch or Greensand was used for this purpose in minor buildings. In larger houses and in churches imported stones were used for the binding of flint walls; for instance in the 14th-century tower of Blandford St. Mary church the flint-work is banded with Heathstone from S. Dorset; in the 18th-century church at Charlton Marshall the flint-work is chequered with Greensand.

Chalk is used in squared blocks, as clunch, to provide an ashlar finish albeit of a weak kind; it is rarely used externally except when banded with flint, and then only in cottages. Clunch is sometimes used for the inner face of barn walls, as at Iwerne Courtney, where the outer face is of Greensand; it is also used for the web of the vaulting at Milton Abbey. Lesser secular buildings of the Chalk area commonly have walls of cob, a kind of concrete made from chalk. Since such walls rapidly deteriorate when damp they are provided with waterproof plinths, generally of flint, and waterproof rendering; occasionally, in 18th-century work, an outer skin of 'mathematical tiles' simulating brickwork is used. At Caundle Marsh cob is made from the argillaceous limestone of the local Forest Marble.

Clay occurs widely N.W. of the Chalk escarpment and in the extreme S. of the area and beyond. Since early in the 17th century it has been used for bricks; previously it was practically unused as a building material except for floor and roof tiles.

Of the imported stones, Heathstone is a coarse brown ferruginous material from the Bagshot Beds of S.E. Dorset (see Dorset II, xxxix); its distribution in Central Dorset is generally confined to the churches of the Winterborne valley and of the Stour valley S.E. of the escarpment. Ham Hill stone from Somerset is found in buildings of high quality all over the area. Portland Stone is found in 18th-century buildings in Blandford Forum and elsewhere. Purbeck Marble is used for decoration, in small quantities, in all parts of the area; it was much used for fonts in the 12th century and for altar-tombs in the 15th century (see Dorset II, xl).

Roof coverings. Until the 19th century Thatch was the normal roofing material of all but the most important buildings in Central Dorset, except perhaps in the Forest Marble district where material suitable for stoneslates is abundant; the great fires of Blandford Forum in 1713 and 1731 are attributable to the prevalence of thatched roofs. On the other hand, large churches and mansions all over Central Dorset were roofed with Stone-slates from the Forest Marble and Purbeck areas, or with slates from Devon and Cornwall. Lead was used for the roof of a chantry at Glanville's Wootton in the 14th century, and in the 15th century it was widely used.

Roman and Prehistoric Monuments

Most of the Roman and prehistoric monuments in Central Dorset lie on the Chalk, particularly those which have survived, until recently at least, as earthworks. A few, chiefly of the Roman period, lie on the Jurassic Beds N.W. of the escarpment. Most of the earthworks are in areas well away from mediaeval and later settlements, generally on the higher ground where arable activity has been limited if not negligible during the past 1,500 years. On lower ground, especially around modern settlements, persistent cultivation from the early mediaeval period onwards has largely destroyed the remains of earlier occupation. The distribution of the surviving monuments coincides to a remarkable degree with the commons, downlands and other uncultivated areas shown on the O.S. map of 1811.

Roads

Although the Roman road from Badbury Rings to Dorchester traverses several parishes in the S. of the area covered by this volume, it is convenient to reserve it to the last volume of the Dorset series, where Roman Roads will be treated integrally.

Roman Fort

At Hod Hill an unusually well-preserved fort of the Roman army, dating from the earliest years of the occupation, exists in one corner of the native oppidum. It was garrisoned by a legionary detachment with auxiliary cavalry, and appears to have been held for about a decade.

Settlements

Apart from hill-forts (see p. xxxviii) and the Neolithic causewayed camp on Hambledon Hill, some twenty-seven occupation sites, including villas and other buildings, are identifiable in Central Dorset (see distribution map at end of volume). Most of the sites are now flat, but a few survive as earthworks; except for some of the latter, from which no dating material has been obtained, all the sites are known to have been occupied in the Roman period and some were occupied in the Iron Age also. In addition, a number of settlements may possibly be detected within areas of 'Celtic' fields, chiefly as crop-marks or soil-marks rather than as earthworks; these are described in the relevant 'Celtic' Field Groups (see pp. 318–321).

Although most of the settlements are on the Chalk, the Iron Age and Roman sites at Marnhull, the Roman villa at Fifehead Neville and the Roman villa at Hinton St. Mary lie on the Corallian ridge. The Roman sites at Holwell and Stalbridge are on Oxford Clay and Cornbrash Beds respectively. Some differences of siting are noticeable between settlements in which occupation began in the Iron Age and those wherein the earliest occupation is of Roman date; the Iron Age sites appear to be restricted to higher ground, locally, whereas at least six of the twenty-one sites occupied only in the Roman period are low-lying, mostly in valley bottoms.

An extensive Roman villa at Fifehead Neville has mosaic pavements of high quality [133]. The design of one of them, and two rings with Christian symbols, link this villa with the mosaics that have recently been found at Hinton St. Mary, presumably the floors of the principal rooms of another villa [145–7]. At Hinton, the representation of a male head backed by a Chi-Rho monogram, together with figures of Bellerophon and the Chimaera surrounded by hunting scenes, raises questions about the extension of Christianity in rural Britain, and the possible Christian significance of ostensibly pagan symbols. The Frampton pavements (Dorset I, 150) and some of the pavements in Dorchester (Dorset II, 536) have many features in common with those of Fifehead Neville and Hinton St. Mary, indicating a 'Durnovarian' school of mosaicists. Other Roman sites include buildings at Milton Abbas, which were probably industrial although unlikely to have been a pottery as is usually claimed, and a well in Winterborne Kingston, the contents of which provide the best evidence for a rural shrine in the area; unfortunately the excavator of both these sites gave insufficient details for precise location.

As in Dorset II, few prehistoric and Roman settlements have survived to be recorded as earthworks. Most of those that do survive are Romano-British, at least in their final phase, but since none has been excavated the structural and cultural development remains unknown. The best preserved sites are at Melcombe Horsey, Piddletrenthide [192], Turnworth [192] and Winterborne Houghton; all are associated with trackways and 'Celtic' fields. The Turnworth site is unusual in that it consists of two small circular enclosures with internal occupation features. One of the Winterborne Houghton sites (10) comprises a series of poorly defined platforms in an incomplete rectangular enclosure; all the other sites consist of level platforms and closes defined by banks and scarps. At Winterborne Houghton (9), where the main occupation area covers at least 3½ acres, the shape of some platforms is suggestive of rectangular buildings, a feature not observed on any other site.

Hill-Forts

There are eight Iron Age hill-forts in Central Dorset: one of them, Dungeon Hill, has already been described in Dorset I (Minterne Magna (6)) but boundary changes have now brought it into Buckland Newton parish; Nettlecombe Tout at Melcombe Horsey is probably an unfinished hill-fort and is therefore included in the number; the others are Hod Hill in Stourpaine, Hambledon Hill in Child Okeford, Rawlsbury in Stoke Wake, Spetisbury Rings, Weatherby Castle in Milborne St. Andrew and Banbury in Okeford Fitzpaine (see distribution map at end of volume). Only Hod Hill has been scientifically excavated, and datable material from the other hill-forts is almost entirely the product of chance.

All but one of the hill-forts lie on the Chalk: Hambledon, Hod, Rawlsbury and Nettlecombe Tout are on the high ground of the N.W.-facing escarpment; Dungeon Hill is on an outlier of the escarpment; Spetisbury and Weatherby are on the dip-slope, overlooking valleys draining S.E. On the other hand Banbury lies N. of and below the escarpment, on a patch of Plateau Gravel surrounded by an extensive area of Kimmeridge Clay, generally shunned by prehistoric peoples. With the exception of Spetisbury and possibly Banbury, the forts occupy sites obviously suited for defence.

The hill-forts vary in internal area from 3 acres (Banbury) [182] to 54 acres (Hod Hill) [198]. The defences vary in size and complexity from the comparatively insignificant bank and ditch at Banbury to the massive multiple ramparts and elaborate entrances of Hod and Hambledon. Spetisbury and Dungeon Hill, like Banbury, are univallate enclosures and there is no evidence that Nettlecombe Tout was otherwise; the other hill-forts are multivallate, but they probably all began as simple enclosures with one main bank and ditch. That this is true of Hod has been proved by excavation, while at Hambledon, which developed in at least three major structural phases, there is evidence that the first and probably the second phases were univallate. The wide spacing of the ramparts at Weatherby [182] suggests that the outer rampart is an addition to an original univallate enclosure. Except for Dungeon Hill, all the hill-forts had entrances with outworks, sometimes of more than one phase. The S.W. entrance at Hambledon is very similar in size and design to the Stepleton Gate at Hod Hill, albeit reversed. Details of rampart construction are available only from Hod Hill, where an initial boxed rampart of the Iron Age 'A' phase was superseded by ramparts of glacis construction.

Occupation earthworks are clearly visible within the defences at Hod Hill [198] and Hambledon [129], and there are traces at Rawlsbury, but they are not recognisable in the other hill-forts. At Hod these earthworks consist largely of hut-circles (at least two hundred are recorded) and storage pits; they once covered the whole of the interior, but the construction of the Roman fort, and recent ploughing, have removed all but 7½ acres in the S.E. corner of the site. At Hambledon the occupation earthworks are widespread and largely undisturbed; they consist almost entirely of platforms (over two hundred are recorded) levelled into the sloping interior. The contrast between Hambledon and Hod, especially in view of their proximity, could hardly be more marked; in part this is due to the more steeply sloping interior of Hambledon, necessitating the construction of platforms, but even on the gentler slopes there are no remains comparable with those of Hod.

Hill-forts and other earthworks on Hod and Hambledon Hills

Hod Hill Remains of Settlement in the Unploughed Area

In few cases are adjacent earthworks demonstrably associated with the hill-forts. Nettlecombe Tout, however, is surely related to the extensive area of 'Celtic' fields with cross-dykes ('Celtic' Field Group (44)) which lies immediately S. of it. Probably the same is true of Rawlsbury and the cross-dykes and 'Celtic' fields to the E. At the N. end of Hambledon traces of 'Celtic' fields are partly overlaid by the outermost rampart.

Evidence for the date of construction and length of occupation of the hill-forts is scanty, except at Hod where excavation has shown that it was continuously and intensively occupied from a late Iron Age 'A' cultural phase until the Roman Conquest. A similar length of occupation is probably attributable to Hambledon, where Iron Age 'A' pottery has been found within the earliest line of fortifications. At Rawlsbury, pottery of both Iron Age 'A' and 'C' types has been found and this, together with the multiple defences, suggests a lengthy period of occupation.

The hill-forts lie within the tribal area of the Durotriges who, on the scanty evidence available, appear to have been strongly opposed to Roman rule. That the Roman Conquest ended the occupation of the hill-forts as defensive centres is dramatically illustrated at Hod, where excavation has produced evidence of an assault by the Roman army, probably the II Augusta Legion under Vespasian; it is recorded (fn. 1) that this legion reduced twenty oppida in southern Britain in A.D. 43–44. A Roman fort was subsequently built within the ramparts and additional entrances were inserted. An unfinished outwork on the N. side of Hod was probably an attempt to strengthen the fortifications against the Roman attack. That a similar fate overtook Spetisbury is indicated by the discovery, within the main ditch, of a mass grave that belongs to the time of the Roman Conquest; it is almost certainly the burial place of those who fell victim to a Roman attack. Spetisbury is interesting as an example of a univallate hill-fort of the 1st century A.D. when, in Dorset at least, multiple defences were common; it would appear that the single rampart was in process of being strengthened in the face of the Roman advance [200].

Finds of the Roman period, including coins, have been made at Hambledon and Dungeon Hill, and Roman pottery is recorded from Weatherby Castle.

Dykes

Twenty-six dykes, or earthworks that probably represent dykes, occur in Central Dorset (see folding map at end of volume). All but one, Combs Ditch, are short lengths of bank and ditch, mostly of the crossridge type. They all lie on the Chalk, the majority of them being on or near the head of the escarpment, and they fall into two main groups: one group around the natural bowl of Lyscombe Bottom (735020), and the other group to the N.E., between Bulbarrow Hill and Shillingstone Hill. Several of the second group lie wholly or in part on 'Clay-with-flints', capping the Chalk.

Nearly every dyke consists of a single bank and ditch, but Blandford St. Mary (27), Cheselbourne (22) and Woolland (9) each comprise two banks with a medial ditch. The dykes vary in length from 70 yds. to 470 yds., and in overall width from 20 ft. to 60 ft.; the majority are from 30 ft. to 50 ft. across. In their present state, the banks rarely exceed 3 ft. in height and the ditches 3 ft. in depth.

Although most of the dykes are of cross-ridge type not all of them are sited across ridges. A few (Milton Abbas (26), Okeford Fitzpaine (39) and (41), Shillingstone (26) and Woolland (7)) cut across and isolate spurs of ground, chiefly the short spurs that jut N. from the Chalk escarpment; they all have the ditch on the up-hill side, facing the higher ground, and they have some of the characteristics of the 'spur dykes' that have been distinguished in Sussex and Wiltshire. (fn. 2) Only at Okeford Fitzpaine (41) is there any indication of an original entrance. The dykes frequently end at or near the shoulder of the ridge or spur, but in a few instances, such as Melcombe Horsey (14) and Woolland (7), they drop right down the slope. Excavation at the W. end of the Melcombe Horsey dyke showed that the ditch ended abruptly and that the bank was probably retained by a light wooden revetment.

The date and purpose of the dykes is largely conjectural, but it is likely that they served primarily as boundaries between units of land; whether between separate estates or between parts within an estate is unknown. Many dykes probably served also to control movement along the spurs and ridges. Each of the two main groups of dykes occurs near an Iron Age hill-fort; six lie E. of Rawlsbury and ten lie S. of Nettlecombe Tout; both these groups are in areas of Iron Age and Romano-British rural settlements and their associated 'Celtic' fields, and in several instances they appear to be integrated with field lynchets. The only direct evidence of date is from Melcombe Horsey (14), where excavation revealed sherds of the Late Bronze Age or Early Iron Age in the secondary silting of the ditch. From the evidence at present available it thus appears that the dykes are a feature of the later prehistoric period, perhaps reaching their maximum development in the Iron Age. That they continued to be used in the Roman period is suggested by their relationship to nearby Romano-British settlements (see folding map at end of volume). Combs Ditch, a linear dyke nearly 3 miles long, began as a boundary bank and ditch, probably of Iron Age date; later it was successively enlarged to become the present formidable defensive work of the Roman period.

'Celtic' Fields

For general remarks on 'Celtic' Fields in Central Dorset, see pp. 318–321.

Flat Burials

Inhumation burials, unmarked above ground, have been found in ten places in Central Dorset. All are presumed to be of Roman date except for two Iron Age burials at Allard's Quarry, Marnhull. With two exceptions the sites have produced multiple burials suggesting cemeteries, but since they have usually been found by accident, and often some time ago, numbers are rarely available. At Great Down Quarry, Marnhull, over twenty burials were recorded. The sites at Marnhull are on the Corallian Limestone ridge and those at Holwell are on Oxford Clay; the others are on the Chalk.

Barrows

As in Dorset II, barrows are described in topographical order from S.W.-N.E. in each parish, and barrow groups are given names of local derivation (see distribution map at end of volume). Information from barrow excavations, which mostly took place during the 19th century and are poorly recorded, often cannot be associated with individual barrows because of difficulty of identification; in these cases the information is set out in a preliminary paragraph before the inventory of barrows. J. B. Calkin's terminology has been followed wherever applicable (Arch. J., CXIX (1962), 1–65).

Two neolithic Long Barrows, Child Okeford (23) and (24), lie on Hambledon Hill near the causewayed camp with which they are almost certainly associated. Orientation, almost due N.–S., is unusual, although in one case (23) it is conditioned by the narrow spur top on which the barrow lies. Both mounds are parallel-sided with ditches extending the full length of the mound; one is 240 ft. long, the other 85 ft. long [132].

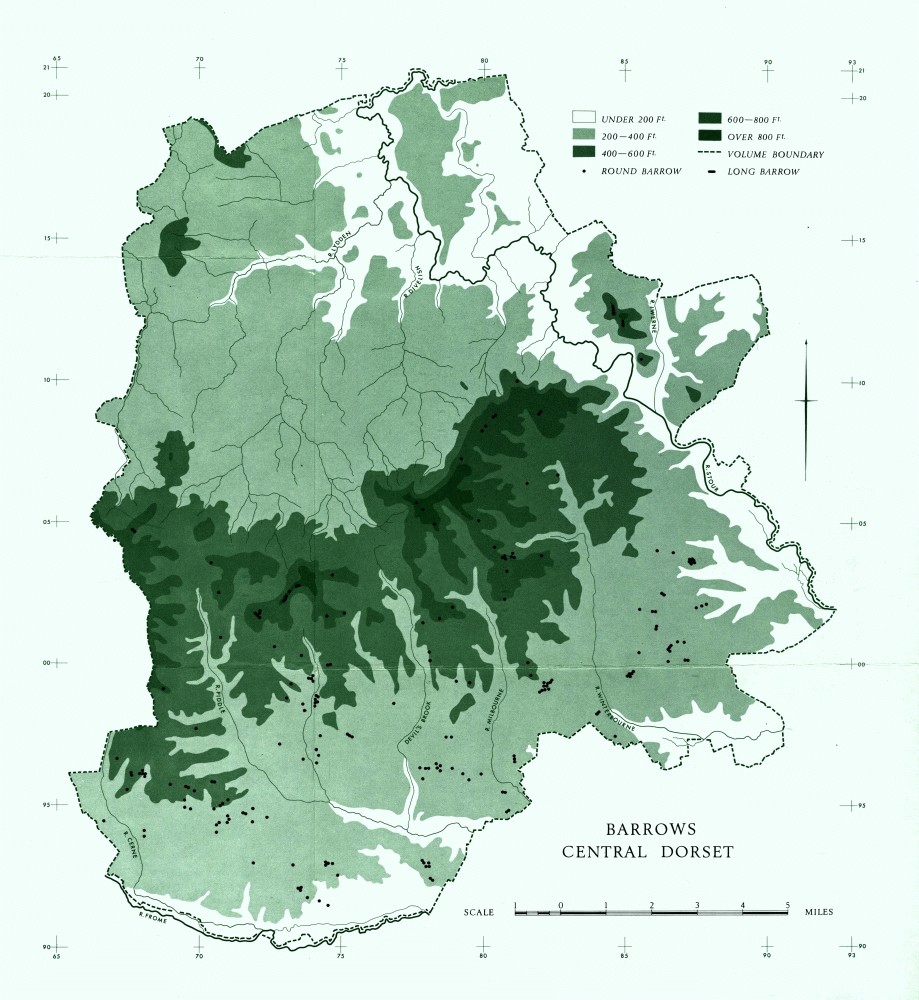

Barrows, Central Dorset

The number of Round Barrows in Central Dorset—just over 200—is very small in comparison with South Dorset. Most of them lie on the dip-slope of the Chalk escarpment and some of them are on the 'Clay-with-flints', which in places caps the higher levels of the Chalk. In the S., a few barrows are found on the heathland of the Reading Beds.

The barrows are well scattered over the Chalk area although, with very few exceptions, they avoid the highest parts of the escarpment. Nearly two-thirds of the total number lie between 200 ft. and 400 ft. above sea-level, the others are higher. They occupy the higher ground between the rivers; some are in prominent positions on the highest local points, e.g. Piddletrenthide (12–15), but many are sited on slopes and false crests and are prominent only when viewed from a particular direction, usually from below.

All the barrows are bowls except for two possible bell-barrows, Milborne St. Andrew (33) and Stinsford (13), and a possible saucer-barrow, Piddletrenthide (59). At least two-thirds of them have been damaged by ploughing, some very severely. Ditches are visible around comparatively few barrows but it is almost certain that the majority originally had ditches which now are filled in, whether by ploughing or by other agencies. Ploughing has affected the size of the barrows, reducing the height and increasing the diameter of the mounds; even so, three-quarters of the measurable mounds are small, 50 ft. across or less. Only one barrow, Puddletown (30), exceeds 100 ft. in diameter; it is unusual not only for its size but also for its situation on the broad, level flood-plain of the River Frome.

In further contrast to South Dorset there are only eight barrow groups, none with many barrows. The largest group is on Deverel Down, Milborne St. Andrew, where the group of eight barrows includes the celebrated Deverel Barrow. All are 'scattered groups' except for the group on North Down, Winterborne Kingston, which is a 'linear group'. (fn. 3)

No barrow has been excavated in recent years but many have been dug into in the past; holes are still visible in about forty mounds. Much of this activity has gone unrecorded, but records were kept of some excavations, chiefly of those carried out during the 19th century. For the most part the records are very brief and it is seldom possible to relate an excavation record with certainty to an existing barrow. The summary nature of many early excavations, together with inadequate recording and publication, means that much information about the structure and contents of barrows has been lost; often it is not even possible to establish the approximate date of the monument. The primary burial is not always to be determined from the records, and sometimes it certainly remained undiscovered; in the few instances where primary burials can be determined with certainty, the lack of associated objects makes some of them undatable.

The earliest datable barrow, one of the Lord's Down group, Dewlish (13), covered a long-necked beaker in a primary position, and it may therefore be dated to the Late Neolithic period; a series of secondary burials, including biconical urns, indicate that the barrow continued in use well into the Early Bronze Age. Of the Early Bronze Age are two other barrows in the same group, with 'Wessex Culture' primary burials, and also the two-phase barrow at Hilton (30), with its primary crouched interment and ridged food-vessel urns in the inner ditch. All the other datable barrows are of the Middle Bronze Age or later, the majority of the primary burials being associated with globular urns. The inverted collared urn which was found, possibly in a primary position, in the Deverel Barrow is unlikely to be earlier than the numerous globular and bucket urns that were found under the mound [132].

Mediaeval and Later Settlement

The pattern, siting and morphology of mediaeval and later settlements in Central Dorset are largely determined by the two very different physical landscapes present in the area: the Chalk land of the Downs, and the Jurassic Clays and Limestones of the Blackmoor Vale (see distribution map at end of volume).

The Chalk Downs

Until very recently, settlement on the Chalk Downs was almost completely governed by the availability of water. Even today settlement is rare outside the valleys, and such settlement as there is is usually of the 19th century or later. Hence mediaeval settlement was largely confined to the deeply-cut narrow valleys which drain S.E. across the Chalk dip-slope. From some of the earthwork remains it appears that the original settlements were small hamlets or farmsteads, set in the valley bottoms and spaced at distances which range from 100 yds. to a mile. Subsequent expansion was along the valley, with the result that the normal form of settlement is a long linear village; such villages sometimes grew to a considerable size, as at Cheselbourne and Piddletrenthide; indeed Piddletrenthide results from the coalescence of several settlements, each of which developed in this way [1]. Where villages are now partly deserted, earthwork remains indicate the same linear morphology, as at Winterborne Clenston [214]. The buildings of these villages were normally strung out along a single street, parallel to the watercourse, as in Winterborne Stickland and Spetisbury, or along two parallel streets on either side of a stream, as in Piddletrenthide and in the old town of Milton Abbas, now deserted (see plan facing p. 199).

Variations on this basic linear pattern occur only where the valleys are wider. The result is a more compact village with an irregular street plan, as at Puddletown, Winterborne Kingston, Hilton and the two deserted villages in Melcombe Horsey. Certain alterations in the pattern of narrow valley villages are evidently of late date and are probably due to changes in lines of communication. For example, Milborne St. Andrew and Winterborne Whitechurch have ceased to be linear valley settlements and have become linear road settlements; leaving the valley layout to survive in the form of earthworks, the present villages are now aligned upon the main road from Dorchester to Blandford Forum. Nearly all the Chalk-land settlements were associated with narrow strips of land running back from the river, usually on one side of the valley but sometimes on both; the boundaries of such land-blocks are often preserved as continuous hedge-lines. Evidence from charters and from Domesday Book indicates that these land-blocks and their settlements composed economic units that were already in existence in the late Saxon period. Each ecclesiastical parish appears to be composed of one or more of such land-blocks (see C. D. Drew, Dorset Procs., LXIX (1948), 45–50).

The Blackmoor Vale

N.W. of the escarpment, in the Vale of Blackmoor, the settlement pattern is very different from that of the Chalk land. The low-lying land has large nucleated villages with outlying farmsteads and hamlets, a pattern that is superficially like that of the Midlands. Again, the surface geology controls the siting of the major settlements. The spring-line at the foot of the Chalk scarp gives rise to a line of nucleated villages from Buckland Newton in the W. to Child Okeford in the N.E. The broad Kimmeridge Clay area to the N.W. is devoid of major settlements, except where the R. Stour crosses the outcrop; here on the river terraces are Manston and Hammoon. The Corallian Limestone outcrop, further N.E., is the basis of another line of villages, extending from Glanville's Wootton in the W. to Marnhull in the N. Beyond this the wide Oxford Clay belt has no nucleated settlement except Pulham and Lydlinch, which both stand on dry gravel patches. Further N.W. the lighter Cornbrash and Forest Marble outcrops give rise to a line of villages from Bishop's Caundle to Stalbridge. The nucleated settlements do not have a common plan; they vary from long street villages such as Stourton Caundle to compact villages like Hinton St. Mary [2].

The outlying farmsteads and hamlets of the area are not, as in the Midlands, late settlement consequent upon enclosure of former open fields; they are the result of a long process of secondary settlement in the waste, developing beyond the open fields of the original nucleated villages. The process started certainly before the Conquest and it continued until the 19th century and later, as the map of Holwell (p. 118) shows.

Secondary settlements like Plumber Manor in Lydlinch and Colber in Sturminster Newton were in existence by 1086, and although others are not recorded in documents until the 13th and 14th centuries many of them are probably much older. There is evidence from Forest Eyres that much assarting was taking place in the area in the 13th century (P.R.O., E 32/10 and 11) and many outlying farms are likely to have been established at that time (see Dorset Procs., 87 (1965), 251–4). The moat at Holwell Manor House probably represents one such outlying farmstead.

Some of the earliest of these farmsteads and hamlets are associated with commons or 'greens', often roughly triangular [3], which probably represent land left for pasture when the surrounding territory was enclosed from the waste into small irregular fields. Outlying farmsteads of 18th and 19th-century origin are associated with fields laid out geometrically, such as Lydlinch (18) and Marnhull (63). Another typical 18th and 19th-century form of settlement has cottages built on the wide verges of roads; these result from Parliamentary enclosure of waste lands, as at Bagber Common in Sturminster Newton, and at Holwell [3].

Mediaeval and Later Earthworks (fn. 4)

These monuments fall into three groups: (a) settlement remains, such as deserted villages, farmsteads and moats; (b) cultivation remains, principally strip lynchets and traces of ridge-and-furrow; (c) miscellaneous earthworks, including deer parks and gardens.

Settlement Remains

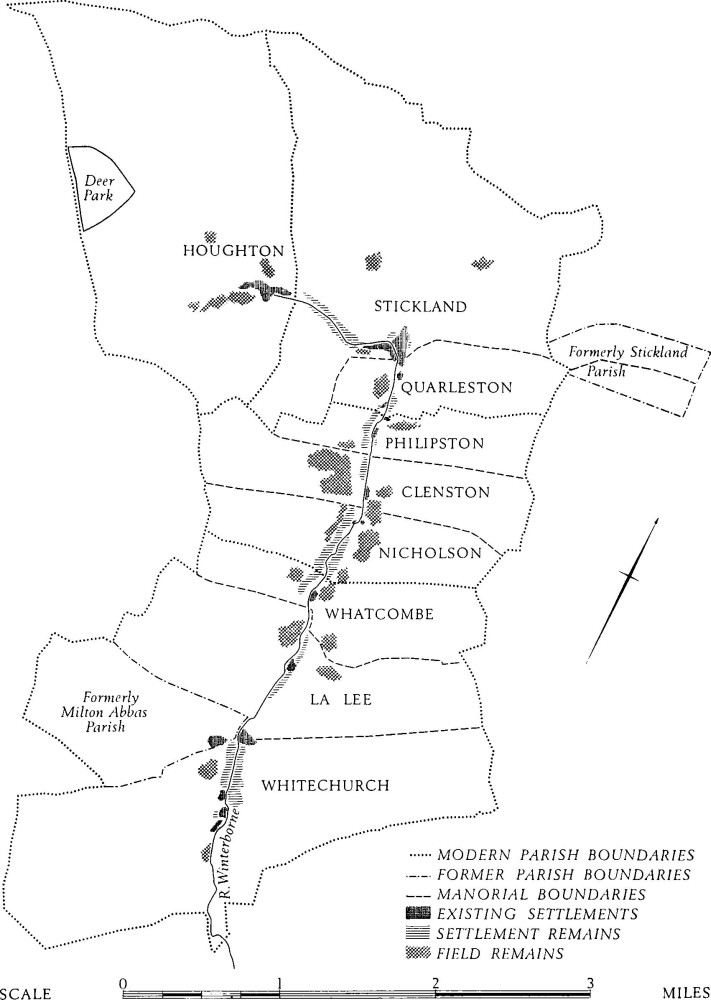

No mediaeval settlement site in the area has yet been systematically excavated and little can be said about the buildings and other features which the earthworks represent. On the other hand, careful use of the documents that survive, in conjunction with study of the earthworks, often throws light on the pattern of settlement; this is especially true in the Chalk area where the abundance of the remains helps materially to build up a picture of the mediaeval settlement pattern. Linear settlements and small compact hamlets and farmsteads all survive in the form of earthworks. The best example of the first type is in the Winterborne valley, where earthworks occur continuously over a length of 4½ miles from Winterborne Houghton in the N. to Winterborne Whitechurch in the S., showing that where now there are four parishes made up of three villages and a scatter of farms, originally there were nine separate settlements, each probably with its own open fields. Examples of separate small settlements are seen in Charminster (22) to (27), where there were once at least ten hamlets or farmsteads within the parish, as well as Charminster itself, strung out along the R. Cerne.

Mediaeval Settlements and Associated Lands in the Upper Winterborne Valley

Off the Chalk there are no large deserted settlements since the great majority of the outlying farmsteads and hamlets are still occupied. Only at Colber in Sturminster Newton parish are there earthworks of a deserted farmstead, and slight remains of larger deserted settlements occur at Stock Gaylard in Lydlinch and at Thorton in Marnhull.

The remains of more than fifty settlements are noted in this volume but only six of them can be said to be entirely deserted: one of the Cernes (Charminster (23)), part of Pulston (Charminster (22b)), Bardolfeston (Puddletown (21)), Cheselborne Ford (Puddletown (23)), Lazerton (Stourpaine (7)) and Colber (Sturminster Newton (69)); the others are all associated with existing villages, hamlets and farms. In a few places a large house succeeds the former settlement.

The reason for the abandonment of settlements is difficult to determine without excavation. Most of the settlements were very small, even in 1086, and the abandoned remains may be the result not of sudden desertion but of a slow decline in prosperity and population over many years. The process can rarely be proved, but Lazerton in Stourpaine may be taken as an example; in 1428 the hamlet certainly had fewer than ten inhabitants, but 250 years earlier it appears to have been almost deserted. It is clear from the Lay Subsidy Rolls that many settlements were almost deserted by the 14th century; Winterborne Clenston (5) is an example, and the pottery found at Hewish in Milton Abbas also indicates abandonment by this date. In contrast Quarleston in Winterborne Stickland was a flourishing community in the early 14th century.

Certain variations are discernible in the forms of the settlement remains. The continuous lines of settlements in the narrow Winterborne and Milborne valleys are remarkably consistent. They have long closes bounded by low banks and are set at right-angles to the stream; house sites, where preserved, are at the lower ends of the closes while other building platforms sometimes occur higher up the valley sides. Roads apparently were adjacent to the streams or were actually in the stream beds, which were often dry. Where settlements are not continuous the same forms recur, as in the Piddle valley and at Pulston and Lazerton. In wider valleys the isolated settlements often comprise square or rectangular closes set on either side of a track or a hollow-way which runs down to and crosses a river, as at Puddletown, Hanford and Blandford St. Mary village. Elsewhere less determinate patterns of closes occur, as at Littleton in Blandford St. Mary and in the two deserted villages of Melcombe Horsey.

Few house sites are well preserved. In most settlements they are merely platforms, either freestanding or cut back into slopes, up to 20 ft. wide and 60 ft. long. Good building sites are found in only two places. Milborne St. Andrew (13) has embanked rectangular building sites within an enclosure, but they are not necessarily the sites of dwellings. On the other hand the earthworks at Bardolfeston in Puddletown include the best preserved house sites in the county [183]; they comprise at least eleven embanked rectangular areas with opposed entrances and traces of internal subdivisions.

Another type of earthwork consists of an enclosure bounded by banks and ditches and sub-divided by banks at right-angles to the perimeter. The enclosures vary considerably in size but are similarly situated on the sides of valleys. Examples occur at Charminster (25), Dewlish (7) and Milborne St. Andrew (13); their purpose is not clear; they may have been some kind of farmyard. A similar site has been noted in Wiltshire (Antiquity XXXVII (1963), 290).

The largest settlement remains in the area are at Milton Abbas; they comprise at least three-quarters of the mediaeval market town which was removed in the last quarter of the 18th century to make way for Lord Milton's park. The town, well documented by an 18th-century plan [176], is now represented by some 25 acres of earthworks.

The so-called 'Castle' at Sturminster Newton is a prehistoric earthwork, reused as a manorial site in the mediaeval period.

Cultivation Remains

Almost all major settlements in Central Dorset appear to have been associated during the mediaeval period with some form of communal or open-field farming. Off the Chalk this usually consisted of a single open field system for each parish. In the Chalk areas, by contrast, many parishes had several open field systems, each system belonging to a separate settlement; for instance Winterborne Whitechurch and Winterborne Kingston probably had three systems each. Thus the 58 modern parishes of Central Dorset contain the remains of over 100 separate open field systems. Most of the open fields were enclosed by the 18th century; there are only twelve parishes with Parliamentary Acts of Enclosure for open fields, and in eight of them the Acts are for the final enclosure of fields which had been partly enclosed earlier.

The field evidence for mediaeval agriculture is of four kinds

(i) Strip Lynchets are fairly widespread in parishes on the Chalk, but they are unknown on the flatter country of the Blackmoor Vale. The remains are of the usual types and are largely identical with those discussed at length in the preceding volume (Dorset II, lxix). An interesting feature are 'flights' of strip lynchets, such as occur in Hilton, Ibberton and Milton Abbas. Enclosure and reploughing has sometimes resulted in unusual forms. The extremely wide terraces near St. Catherine's Chapel at Milton Abbas (24) are not strip lynchets; they appear to be special cultivation terraces and are almost certainly earlier than the 12th century.

(ii) Ridge-and-Furrow of Open Field type (discussed in Cambridgeshire I, lxvi) was formerly widespread in Dorset in parishes off the Chalk, where the pattern of curving and interlocking furlongs is identical with that well known in the Midlands. The feature is less common in the Chalk areas, probably because subsequent ploughing has destroyed the slighter remains there.

(iii) Ridge-and-Furrow of Old Enclosure type has been discussed at length elsewhere (Cambridgeshire I, lxviii) and little more need be said about it. The type occurs in almost all parishes on the Jurassic Beds and is in most instances confined to irregularly shaped fields, lying beyond the limits of the former open fields. These irregular fields were apparently enclosed direct from the waste; they are associated with small hamlets and isolated farms, secondary to the main parish settlement.

(iv) Ridge-and-Furrow lying over 'Celtic' fields, together with the modification of 'Celtic' fields in the mediaeval period, are discussed on p. 318 (see also Dorset II, lxix). As a rule, such remains represent a temporary, and usually undated, extension of the permanent arable into marginal land.

Miscellaneous Earthworks

The most important of these earthworks are the mediaeval Deer Pales. Five deer parks are known in Central Dorset but only those of Milton Abbas and Winterborne Houghton are recorded in the Inventory; those of Buckland Newton, Melcombe Horsey and Athelhampton have been omitted because the remains are too fragmentary; detailed accounts will be found in Dorset Procs. LXXXIV, (1962), 147; LXXXV, (1963), 145; and LXXXVIII (1966), 177. An earthwork described in Buckland Newton (21) probably represents yet another deer park.

Mediaeval and Later Buildings

Ecclesiastical Buildings

Apart from the Roman pavement with a Chi-Rho monogram at Hinton St. Mary, which is unlikely to be ecclesiastical (see p. xxxvii), no pre-Conquest church monument remains in situ in Central Dorset. Minor fragments of 10th or 11th-century interlace carving are preserved at Milton Abbey [12], in the parish church at Puddletown, and in a house at Melcombe Horsey.

The earliest church buildings in the area are the apsed chapel of St. Andrew at Winterborne Tomson in Anderson parish [96], and the parish church of Iwerne Stepleton, which has a fine round-headed chancel arch; both buildings are of the late 11th or early 12th century. The S. wall of the church at Shillingstone, with round-headed loops, is of the early 12th century. Charminster retains the clerestorey walls of a large church of about the same date, but the arcades were rebuilt later in the 12th century [6]. St. Catherine's chapel at Milton Abbas is of the late 12th century and has a fine chancel arch [179], and a S. doorway with a contemporary inscription [49] and a round outer head enclosing a segmental tympanum arch [10]; this kind of doorway is apparently a local peculiarity, other doorways of comparable date and form occurring in the churches at Milborne St. Andrew, Belchalwell in Okeford Fitzpaine, Dewlish and Piddletrenthide [11]. A small deserted chapel in Lyscombe Bottom, midway between Cerne and Milton Abbeys, is of the late 12th century; it is urgently in need of repair.

The most notable 13th-century building is the chancel of Buckland Newton church [120] which, though restored, is sophisticated work for a village church, but unfortunately deprived of the original E. window. Stinsford has nave arcades and a chancel arch [201] of the same period. At Cheselbourne a 13th-century S. aisle or S. chapel was entered through a pair of archways with pointed heads resting on a central column with matching responds, but the original arrangement has been greatly modified. The chancels at Hammoon, Manston, Milborne St. Andrew and Winterborne Whitechurch were all rebuilt or remodelled at this time, and all of them retain well-proportioned E. windows of gradated triple lancets. Spetisbury church has a restored 13th-century N. arcade.

The predominant work of the 14th century was the rebuilding of Milton Abbey church [161–8] after the fire of 1309; an indulgence to assist the rebuilding was granted by the Bishop of Salisbury and the work continued throughout the century. Of comparable quality but very much smaller in scale is the chantry [138] at Glanville's Wooton, c. 1344. Later in the 14th century Marnhull church appears to have been enlarged to include a chantry chapel with a priest's cell above it. Other 14th-century works include church towers at Blandford St. Mary, Dewlish, Iwerne Courtney and Stinsford. At Okeford Fitzpaine the base of the 15th-century tower incorporates, on the E. side, a wide central archway flanked by two narrower openings [180]; this feature is probably of the late 14th century.

The prolific building activity of the 15th century is well represented in Central Dorset. Of the fifty-eight parishes in the area at least twenty-four rebuilt or heightened their church towers; the finest of these is Piddletrenthide [186], dated 1487, and good examples are found at Okeford Fitzpaine, Child Okeford and Durweston [9]. Handsome and spacious naves with arcaded aisles were built at Buckland Newton [120], Hazelbury Bryan [138], Holwell [7], Puddletown [185] and Mappowder, to name only the most impressive. Chantries were provided at Puddletown, Melcombe Horsey and Purse Caundle. The rebuilding of the great church at Milton Abbas was resumed; the tower over the crossing was completed and the N. transept was added. Provision had already been made in the 14th century for the addition of nave and aisles on the W. of the crossing, but the Dissolution of the Monasteries supervened and the church still remains incomplete.

Perhaps the best 16th-century church building in Central Dorset is the noble tower of Charminster [121], and other work of good quality is seen in the naves and aisles at Piddlehinton and Piddletrenthide. The ecclesiastical buildings of Sir Thomas Freke at Iwerne Courtney and Melcombe Horsey [159] are interesting examples of 17th-century 'Gothic'; pointed windows in Hanford and Manston churches represent the same style, the E. window at Hanford [141] being particularly noteworthy.

Blandford Parish Church [frontispiece], built by the brothers John and William Bastard in 1733, is doubtless the most important of the few 18th-century churches of Central Dorset, but the interior of Charlton Marshall church [8], remodelled in 1713, is perhaps a more distinguished work. At about the same time alterations were made to the naves of Winterborne Stickland and Fifehead Neville churches. At Bryanston a small but elegant chapel, the burial place of the Berkeley-Portman family, was built in 1745.

The earliest 18th-century 'Gothic Revival' church in Central Dorset is the parish church at Milton Abbas, consecrated in 1786. Sturminster Newton parish church was extensively rebuilt in 1827, and at Winterborne Clenston in 1839 the old parish church was pulled down and a new one by Lewis Vulliamy was built [215]. The parish church of Hinton St. Mary is largely of 1846. New churches were built at Plush and Tincleton in 1848 and 1849, the architect for both being Benjamin Ferrey.

Church Roofs

Milton Abbey is the only stone-vaulted church in Central Dorset. The towers of Marnhull and Piddletrenthide retain the springings of stone vaults, that of Marnhull being completed in timber. The porches of Buckland Newton and Hilton churches have small 15th-century ribbed vaults, possibly reset.

Of timber roofs, the earliest is at Tolpuddle, dating from the 14th century [210]; the handsomest is the late 15th or early 16th-century wagon roof of the nave at Sturminster Newton [209]. Winterborne Tomson chapel in Anderson parish, the nave and N. aisle at Hazelbury Bryan and the nave at Holwell have less elaborate 15th-century wagon roofs. At Puddletown the nave has an arch-braced collar truss of low pitch carrying moulded longitudinal and transverse members, forming coffers [20]. At Marnhull the nave is spanned by heavily-moulded, cambered beams which support a coffered ceiling with rich fretted decoration in each panel [151]. The aisles of Holwell, Hazelbury Bryan [21] and Hilton have handsome coffered oak ceilings, that at Hilton being dated 1569. The fine 15th-century hammer-beam roof which now covers a barn in Winterborne Clenston [216] was probably taken from a monastic building.

Church Fittings etc.

Altars: Mediaeval stone altar slabs survive in the churches of Glanville's Wootton and Mappowder. Another altar slab has been reused as the lintel of a fireplace in a house at Piddletrenthide (10).

Bells: The two oldest bells in the area, and probably the oldest in Dorset, are at Hanford and Stock Gaylard (Lydlinch); they may be of the 13th century. Numerous 15th and 16th-century bells come from the Salisbury foundry and the earliest known bell from the foundry of John Wallis of that city, dated 1581, is at Buckland Newton; the same foundry was still producing bells in 1636. William Purdue supplied a bell at Holwell in 1604, and he and others of his family are well represented in the belfries of Central Dorset. Several churches have 18th-century bells by one or other of the Bilbies. (fn. 5)

Brasses: The area is not rich in mediaeval brasses. The earliest, in Pulham church, consists of three lines of black-letter dated 1433; a somewhat similar brass at Tincleton is dated 1434. Puddletown church has three 16th-century brasses; Roger Cheverall's, 1517, Christopher Martyn's, 1524 [40], and the third, more elaborate and with four separate plates, of Nicholas Martyn, 1595 [40]; the last is mounted on the rear wall of a canopied table-tomb. Christopher Martyn's brass is the earliest in the area to have an English as opposed to a Latin inscription. At Milton Abbey the monument of Sir John Tregonwell, 1565, is a canopied table-tomb with six brasses, one depicting the knight wearing a tabard [41]. Purse Caundle has small brasses with figures and black-letter inscriptions of 1527 and 1536, that of 1527 being in English [40]. Piddletrenthide has a Latin black-letter inscription of 1564; henceforth there are no more black-letter brasses. At Cheselbourne are three finely engraved rectangular brass plates with shields-of-arms and a verse inscription in Roman lettering dated 1589; Marnhull has a boldly engraved inscription dated 1596. At Woolland a pleasing poem is inscribed on brass in memory of Mary Argenton, 1616; above it on a separate plate is depicted a lady at prayer [40]. Piddlehinton church contains a rustic brass with Latin verses and a crude portrait commemorating Thomas Browne, parson, 1617 [41]. Buckland Newton has a brass plate with Latin verses in memory of Thomas Barnes, 1624; Purse Caundle has one, delicately engraved, commemorating Peter Hoskyns, 1682, mounted in an original aedicule of carved oak. Reset in the 19th-century church at Athelhampton is a small plate to George Masterman, 1744.

Indents for brasses include a floor-slab at Milton Abbey outlining a recumbent figure in vestments, under a canopy; the brass probably represented Abbot Walter de Sideling (d. 1315). At Milborne St. Andrew the canopied table-tomb of John Morton, 1526, retains the inscription-plate, but the brasses of kneeling figures, shields and other devices have gone.

Candelabra: Hanging brass candelabra of the 17th or early 18th century are found in Milborne St. Andrew and Winterborne Stickland churches; the former is dated 1712.

Capitals, Bosses, Head-corbels etc.: A small freestanding shaft capital with four canted volutes and a chamfered abacus, found among detached fragments at Milton Abbey, is probably of the 12th century. The label of the chancel arch in St. Catherine's chapel at Milton ends in grotesque beasts of the late 12th century and Marnhull church has a four-shafted pier with head-capitals of about the same date [16]. At Mappowder church are some reset 12th-century head-corbels, probably from an eaves corbel-table. Head-corbels at Holwell resemble 12th-century work but their correspondence with 15th-century mouldings in situ shows them to be archaistic. Stinsford is the only church in the area with 13th-century stiff-leaf decoration [16]. Hazelbury Bryan church contains two 14th-century shaft capitals with naturalistic foliage [16], and Milton Abbey has many 14-century vaulting bosses of high quality [165]. Of the 15th century are a number of capitals carved to represent angels holding scrolls and shields; good examples are seen at Holwell, Marnhull and Stalbridge [17]. Mappowder has a skilfully carved 15th-century head-corbel with foliage issuing from the nostrils, and Cheselbourne has a capital representing a grotesque woman in a monstrous head-dress [16]. Many 15th and 16th-century church towers and parapets in the area have gargoyles of fantastic form; Pulham and Piddletrenthide are notable in this respect. At the W. end of the nave arcades Pulham also has a pair of Italianate corbels of the 16th century [17].

Communion Tables and Communion Rails: A table and rails were installed in Puddletown parish church c. 1635; the table has the usual heavy turned legs of the period and the communion rails, which enclose the sanctuary on three sides, have stout turned balusters, and corner-posts with ball finials supporting brass candlesticks [23]. Melcombe Horsey church has a table and rails of about the same date, but the chancel is narrow and the rail extends from side to side. A 17th-century communion table with legs in the form of stout Tuscan columns is at Charlton Marshall church, and well preserved 17-century communion rails with turned balusters are found at Purse and Stourton Caundles [23] and at Hammoon.

Although Charlton Marshall's present communion table is of the 17th century, the table designed for the building of 1713 is probably a smaller piece that now stands in the vestry; it is of oak and has deep arcuated top-rails, turned legs with octagonal tapering shafts, and scrolled diagonal stretchers. The tapered legs are repeated in the balusters of the communion rail [23]. Winterborne Stickland church has a table very similar to that of Charlton Marshall.

The communion table made, no doubt by the Bastard brothers, for the chancel of Blandford Forum church, c. 1733, now stands at the E. end of the S. aisle [45]; it is of oak with enriched cabriole legs and delicately carved top-rails. A smaller table of the same kind is found at Okeford Fitzpaine. Winterborne Tomson chapel in Anderson has communion table, rails, pulpit and seating, all probably of the second or third decade of the 18th century [96].

Fonts: The earliest and most interesting font in Central Dorset is at Puddletown [28]; it is a tapering cylinder covered externally with a reticulate pattern enclosing palmettes; Milborne St. Andrew has a tub-shaped font with cable mouldings at the top and scallops at the base; Farrington in Iwerne Courtney [26] and Plush in Piddletrenthide have crude stone tub fonts with horizontal roll-mouldings at about half height and vertical fluting above; all these are of the 12th century. Several churches have square or octagonal Purbeck marble bowls of the late 12th or early 13th century with recessed arcading on the sides; they usually rest on a central stem surrounded by four or eight thinner shafts and have a chamfered octagonal plinth below; Lydlinch provides a good example [26]. The late 12th-century font at Mappowder [26] elaborates the same theme, having a square bowl with shallow reliefs on each side and the underside shaped to form capitals for five supporting shafts; the shafts stand on a plinth with intersecting base mouldings. A 13th-century octagonal bowl with trefoil-headed sides, and capital mouldings below each corner, is now in the garden at Hanford Farm, Child Okeford; it probably belongs to Hanford church. The plain spherical bowl on a squat moulded stem at Stalbridge is perhaps also of the 13th century. The fonts at Hammoon and Fifehead Neville have plain octagonal bowls converted to square bases by means of broach stops; they are probably of the 14th century. Most 15th-century fonts are octagonal and have cusped panelling on stem and sides; typical examples are at Ibberton and Stoke Wake [26]. Winterborne Whitechurch has an elaborate 15th-century font [28] with an octagonal bowl decorated with rich vine-scroll carving; the stem is surrounded by three free standing shafts decorated with pinnacles; the heads of the shafts are masked by shields-of-arms.

Several churches have 18th-century fonts. Those with baluster stems, square on plan, at Blandford Forum, Charlton Marshall and Winterborne Stickland are of Portland stone and presumably come from one workshop [27]. Stourton Caundle has a circular version of the same theme, and a similar example has recently been taken from Melcombe Horsey and is now at Swanage (see Dorset II, 292). Several of the 18th-century fonts have contemporary dome-shaped oak covers with enriched finials.

Galleries: The oak gallery on bulbous Doric columns at the W. end of Puddletown church is dated 1635 and is the earliest W. gallery to survive in Central Dorset. The timbers of a W. gallery at Tomson church, Anderson, are mediaeval but reset; they probably come from a former rood-loft. At Cheselbourne the oak stairs to a former gallery are preserved but they too are now reset. In Blandford Forum church an elegant W. gallery was inserted in 1794 to accommodate the organ; the side galleries were added in 1837.

Glass: Little mediaeval window glass of merit survives in the area; the best is the 15th-century glass in the tracery lights in Hazelbury Bryan church [139]. Other fragments of mediaeval glass are found at Melcombe Horsey and Lydlinch [144]. Milton Abbey has some 14th-century grisaille, numerous 15th and 16th-century shields-of-arms, and a large mid 19th-century window by A. W. Pugin. Ibberton has one panel of 15th-century heraldic glazing [144] and two heraldic panels of 16th-century date [44].

Among secular buildings the most notable collections of heraldic glass are in the halls at Milton Abbey, at Athelhampton and at Bingham's Melcombe [160]. Lovell's Court, Marnhull, contains some 16th-century heraldic glass recently brought from Lancashire.

Helmet: A 16th-century close helmet with Cromwellian modifications is preserved in Iwerne Courtney parish church.

Hour-Glass Stands: of wrought iron occur in the churches at Hammoon, Manston, Holwell and Spetisbury; the latter is probably dated 1700. Hour-glasses are preserved at Holwell and Spetisbury.

Images: There are not many examples in the area and the most important is the earliest, namely the late 10th or early 11th-century relief of an angel, reset in Stinsford church tower [12]. Buckland Newton has a small Christ-in-Majesty of the 12th century [12]. The reredos in Hammoon church, depicting the Crucifixion and six flanking figures in niches, is of the late 14th or early 15th century, but it is a recent acquisition and of unknown provenance. Durweston has an odd clunch relief [13] thought to represent St. Eloi, and Winterborne Stickland has a small semicircular relief of the Crucifixion; both these are of the 15th century. Milton Abbey has part of a 15th or early 16th-century figure of St. James the Great. A small mica-schist relief of a warrior [13], now reset in Buckland Newton church, was discovered in a nearby garden in 1913; it probably is of the 8th or 9th century, but it can scarcely be of local origin.

Monuments: Mediaeval funeral monuments in Central Dorset include eleven with recumbent effigies. The earliest is the 12th-century relief of Philip, priest of Tolpuddle [193]. Effigies of an armoured man and his wife at Puddletown, and a miniature effigy from a heart-burial at Mappowder [14] are of the mid 13th century; of the late 13th century are effigies of a bare-headed man with a sword in Glanville's Wootton church and of an armoured figure in Stock Gaylard church [14]. Of the 14th century is an armoured figure at Puddletown [189]; it lies on an arcaded altar-tomb in a cusped ogee-headed wall-recess. Adjacent is a tomb of c. 1460, with figures of an armoured man and his wife, with angels in niches around the sides of the tomb-chest [188]; Marnhull church contains a tomb of about the same date, representing a man in armour flanked by two ladies [15]. Also of the mid 15th century is a small effigy of a lady at Stourton Caundle [193]; she now lies in a niche which was formerly part of another tomb. The splendid alabaster effigy on the tomb of Sir William Martyn (d. 1503) at Puddletown [15] is probably of the late 15th century; it lies in a rich canopied table-tomb of Purbeck marble. Stalbridge has a late 15th or early 16th-century cadaver effigy [193].

Late mediaeval canopied table-tombs with brasses (q.v.) instead of effigies are found at Charminster, Milton Abbey and Milborne St. Andrew. Tombs of similar form but with Renaissance instead of Gothic detail occur at Puddletown and Spetisbury; both date from the end of the 16th century [31].

Of numerous 17th-century monuments the most notable are those of Sir Thomas Freke at Iwerne Courtney [36] and of Grace Pole at Charminster [34], dated respectively 1633 and 1636. Glanville's Wootton church contains a large wall-monument [35] of 1679 and several lesser examples of about the same date. Noteworthy among the later 17th-century wall-monuments are those of John Straight at Stourpaine [33] and of Grace Morris at Manston [33].

The most impressive 18th-century monument in the area is that of Mary Bancks (d. 1734) in Milton Abbey [37]; the same church enshrines a remarkable tomb erected in 1775 by Joseph Damer, Earl of Dorchester, in memory of his wife [169]; it comprises a marble table-tomb in the Gothic style by Robert Adam with effigies of the deceased lady and her sorrowing lord by Carlini. Among many admirable 18th-century wall-tablets, that of Francis Cartwright at Blandford St. Mary is outstanding for sensitive design and skilful workmanship [119]. Of 19th-century monuments, two examples [39] by King of Bath are notable, one at Bishop's Caundle and one at Buckland Newton, both dated 1815. Characteristic of the mid 19th century is a monument in the chancel of Piddletrenthide church by C. R. Cockerell.

Paintings: Twelve 15th-century oak panels, each depicting an Apostle, were transferred in the 18th century from Milton Abbey to Hilton church where they still remain [25, 137]. Another 15th or early 16th-century panel, possibly from the same source, is preserved at Stock Gaylard church in Lydlinch. Incorporated in the choir-stalls at Milton Abbey are two crude and much restored panels representing a king and a queen. The earliest wall-painting on plaster exposed in a Central Dorset church is the stencilled overall pattern of strawberries and leaves at Charminster; it is probably early 16th-century work. Crude 16th-century outlines of human figures are preserved on the W. wall of Marnhull church. Painted prayers and texts of 16th and 17th-century date have been exposed in several churches, notably at Charminster, Marnhull and Puddletown.

Many churches retain painted hatchments of the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries. At Marnhull one is dated 1631 and another 1663; Lydlinch parish church has one of c. 1650 [44].

Plate: The earliest dated communion cup in Central Dorset is at Mappowder [42]; it has hallmark and date-letter for 1570 and an undecipherable maker's mark. The cup at Charminster is probably of the same date but the letter is badly stamped. Both vessels are of the usual Elizabethan pattern in which the conical bowl is deep, slightly flared and decorated externally with a belt of engraved foliate strapwork; the stem has a central knop and the foot is domed. Between 1570 and 1573 nine Central Dorset parishes obtained similar cups, but no two have the same maker's mark. (fn. 6) On the other hand, one silversmith, Lawrence Stratford of Dorchester, supplied cups and cover-patens in 1574 for Cheselbourne, Dewlish, Okeford Fitzpaine, Shillingstone [42] and Winterborne Houghton; in 1575 he made one for Burleston and in 1577 he made one for Tolpuddle. None of these has a hallmark or a date-letter but they all bear Stratford's mark 'LS' and they have the date engraved on the cover-paten.

Of about the same date but of slightly different form are cups and cover-patens at Hammoon, Hinton St. Mary and Marnhull [42]; they are undated and without hallmarks but they all bear the mark of another local maker, the so-called 'Gillingham' silversmith. (fn. 7) These cups have trumpet-shaped stems with knops near the bowl and strapwork engraving somewhat plainer than that of Lawrence Stratford.

The taste of the 17th century is exemplified in the cup of 1649 at Iwerne Stepleton [42] and that of 1663 at Sturminster Newton; on the other hand a typical Elizabethan cup hallmarked as late as 1633 is found at Stoke Wake. The parish church at Milton Abbas has a cup and cover-paten of 1636, another paten given in 1678, and a flagon of 1663 presented by 'Maddam Jane Tregonwell . . . 1675'; these vessels have now been transferred from the abbey to the parish church.

At Winterborne Whitechurch a silver two-handled bowl of 1653 is used as a communion cup [43]. Turnworth church has a similar vessel, hallmarked in 1764; presumably it is a replica of the first.

In 1714 a silver cup and flagon were acquired by Charlton Marshall church under the will of Catherine Sloper; the cup [43] is of pleasing form with an unusually stout stem. The cup and flagon of 1731 and 1732 in Blandford Forum church have profiles similar to those of Charlton Marshall, but are of slenderer proportions. The handsomest set of 18th-century church plate in Central Dorset is the silver-gilt cup, cover-paten and flagon which Mrs. Strangways Horner gave to Stinsford church in 1737 [202]; the vessels were made by Paul Lamerie and have the date-letter of 1736; in 1755 the same donor presented a bread-knife and sheath. A similar set of church plate is at Abbotsbury (Dorset I, 3). Another fine set of cup, paten and flagon [43], with hallmarks of 1764, given to Bryanston church by the Berkeley-Portman family, is now at Durweston. An unusual cup and cover at Tincleton is probably German 16th-century work; the same parish has an English flagon, apparently designed to match the cup, presented in 1718; the flagon was repaired in 1900 and new hallmarks were applied in that year.

The Congregational Chapel at Blandford Forum has two two-handled silver communion cups of 1714, each with a gadrooned base, enriched necking, and the inscription 'B.M.H.', for Blandford Meeting House.

Pulpits: of 15th-century date survive at Okeford Fitzpaine and Winterborne Whitechurch [46]. The former is of stone and the latter is of wood, but both pulpits are polygonal, with a canopied niche in each side; the drum walls alone are original, plinths, pedestals, top mouldings and much of the detail being 19th-century restoration. Stourton Caundle has a polygonal oak pulpit of the early 16th century in a good state of preservation [46]; its sides have two heights of panelling, the lower panels with linenfold decoration, the upper panels with blind tracery. The richly carved early 17th-century pulpit in Spetisbury church is also polygonal and of oak. Of similar form to the Spetisbury pulpit but simpler in detail is one at Charminster, dated 1635. Also of about 1635 is a polygonal oak pulpit at Puddletown, with arcaded sides and coupled Roman Doric columns at the corners [47].

Oak pulpits of the late 17th and early 18th century occur in many churches; they are polygonal and are often decorated with carving or marquetry. At Holwell the panels have reeded decoration recalling linenfold; at Hazelbury Bryan the pulpit has a wooden sounding board, formerly with a tent-shaped superstructure which has now become the font cover. Charlton Marshall has a handsome pulpit of carved oak and marquetry, crowned with a domed sounding board on top of which stands a carved pelican [47]; presumably this pulpit dates from the restoration of the church in 1713 and it is likely to have been made in the Bastard workshop at Blandford Forum. The same workshop supplied the pulpit at Melcombe Horsey in 1723.

Reredoses: Apart from the recently acquired stone reredos at Hammoon (see Images) the only mediaeval reredos to survive in Central Dorset is at Milton Abbey [166]; an inscription upon it is dated 1492, and although the upper parts of the masonry are largely late 18th-century work much of the lower storey, including some painted decoration, is original. Blandford Forum, Charlton Marshall and Bryanston have carved and gilded 18th-century reredoses inscribed with the Ten Commandments.

Screens: Part of a 15th-century stone screen with niches [24] is reset in the S. transept of Milton Abbey, and the reset beams of a timber rood-screen are preserved at Tomson chapel, Anderson. The 17th-century carved oak screen at the E. end of the N. aisle of Iwerne Courtney church [143] is the most notable piece of woodwork in the area; it encloses the monument to Sir Thomas Freke, 1654, but the style of decoration is earlier and the screen may have originally enclosed the Freke family pew; hence it is probably of 1610, when the church was rebuilt. In 1619 Sir Thomas Freke also erected an oak screen [22] in the church at Melcombe Horsey.

Seating: Very little remains of the mediaeval seating in Central Dorset churches. Milton Abbey has a notable set of painted stone sedilia [166] and fragments of a few oak choir stalls with plain misericordes. Many churches were provided with new seating in the 19th century, often by dismantling and reassembling earlier woodwork, whereby original bench-ends were occasionally preserved; some at Buckland Newton are perhaps of the late 15th century. Puddletown retains a noteworthy set of 17th-century panelled oak box pews [185], and Winterborne Tomson chapel at Anderson retains the neat box pews [96] which Archbishop Wake supplied in the 18th century (Hutchins I, 196). A few 17th-century oak benches survive at Okeford Fitzpaine. The Mayor's seat in the parish church of Blandford Forum, dated 1748, is handsomely carved [101].

Miscellaneous Woodwork: Special mention must be made of the remarkably well-preserved 15th-century hanging pyx-shrine in Milton Abbey [167]; it is of three stages with a spire finial and is lavishly decorated with carved tracery. Other examples are known at Wells and Tewkesbury (P.S.A., XVI (1897), 287–9) and at Dennington in Suffolk. Another interesting object is the 16th-century carved oak pedestal alms-box in Buckland Newton church [22]. Several churches have 17th and 18th-century armchairs and coffin-stools of carved oak; a chair at Milborne St. Andrew is dated 1670 and stools at Marnhull are dated 1683.

Public Buildings

Almshouses: A row of almshouses built in 1682 [112] was one of the few buildings to escape the fire of 1731 at Blandford Forum. A slightly earlier almshouse building in the old town of Milton Abbas was transferred and re-erected in the new model village in 1779, a surprisingly early and successful example of conservation [178]. A workhouse of 1838 by Lewis Vulliamy continues to function at Sturminster Newton, converted into a home for old people.

Assembly Rooms: of the early 19th century are found in Blandford Forum and Sturminster Newton; the first is now a garage and the second is used as a badminton court.

Bridges: Sturminster Newton [51], Spetisbury [199] and Bishop's Caundle have bridges which incorporate late 15th or early 16th-century elements; a small rubble footbridge at Fifehead Neville may also be mediaeval. Blandford Bridge is principally of the 18th and 19th century but the westernmost arch is probably late mediaeval [114]. Durweston Bridge [51] and King's Mill bridge at Marnhull were built in 1795 and 1823 respectively.

Crosses: A stone market cross of the late 15th century survives in a good state of preservation at Stalbridge [50]; the sculptured cross-head and finial were destroyed in a storm in 1950 but they have been renewed. Other mediaeval wayside, market or preaching crosses are represented by stepped pedestals at Sturminster Newton, Minterne Parva in Buckland Newton, Hammoon, Okeford Fitzpaine and Shillingstone; at Shillingstone a modern cross-shaft has been erected on the mediaeval steps.

Town Hall: The Town Hall of Blandford Forum was rebuilt after the fire of 1731; the ground floor is an arcaded loggia and the upper storey is occupied by courtrooms; the Portland stone façade [106] is dated 1734 and signed 'Bastard, Architect' [107].

Domestic Buildings

The earliest surviving secular building in Central Dorset is probably the 14th-century hall and solar at Fiddleford Mill in Sturminster Newton [206–8]. In spite of 16th-century modifications the buildings retain two very important original roofs of much elaboration; the monument is now in the care of the Ministry of Public Building and Works. Hinton St. Mary Manor House may incorporate the walls of a hall as early as the 13th century, but too little remains visible for reliable assessment.

The mid 15th-century Manor House at Winterborne Clenston has a first-floor hall and an adjoining chamber with moulded and cusped arch-braced collar-beam roofs. Access to the hall is by a stone newel staircase in a projecting tower at the centre of the W. front [213]. Purse Caundle Manor House [194–6] has a mid 15th-century ground-floor hall, open to the roof, with two-storied cross-wings to N. and S.; the S. cross-wing has a pleasing first-floor bow window. The hall at Athelhampton is an important example of late 15th-century domestic architecture; it has a beautiful oriel window [94] and the open roof with its enormous decorative cusps is especially noteworthy [95]. The abbot's great hall at Milton Abbey, finished in 1498, has a richly carved hammer-beam roof [172].

Of smaller 15th-century buildings the most interesting is Naish Farm, Holwell. It is a mediaeval farmstead almost in its original state, except for 16th-century chambering-over of the hall. Senior's Farm at Marnhull is a handsomely decorated dwelling of the late 15th or early 16th century and probably originated either as a chantry house or as an occasional lodging for the Abbot of Glastonbury, who was lord of the manor [56].

Wolfeton House, Charminster, retains an impressive gatehouse of c. 1500 with quasi-defensive towers [125]; the elaborately decorated S. range is of the mid 16th century but the greater part of the original 16th-century house has perished. Bingham's Melcombe, principally of the mid 16th century although the gatehouse is slightly earlier, is renowned as one of the loveliest of English country houses [153–60]. Hammoon Manor House comprises an early 16th-century timber-framed dwelling with later 16th-century additions in stone [134]. Kingston Maurward Old Manor House in Stinsford parish has the remarkably well-preserved outer shell of a late 16th-century house on an E-plan [204], but the interior has largely perished. Round Chimneys farmhouse at Glanville's Wootton, another notable late 16th-century house [56], is much diminished from its original size.

Of minor 16th-century dwellings, Haydon Farm at Lydlinch is a good example of a farmhouse on an L-plan; it has moulded and panelled timber ceilings and a through-passage with plank-and-muntin partitions. Pear Tree Cottage, Piddletrenthide, is notable for its well documented history. Manor Farm, Caundle Marsh, has a 15th-century nucleus with 16th and 17th-century additions.

Buildings of the 17th century include Hanford House [135], which dates from 1604–23 and has a square plan with a central courtyard; it was probably designed in imitation of an Italian palace but apart from a few copy-book details the elevations have little Renaissance character. The neighbouring and almost contemporary house at Iwerne Stepleton originally had a somewhat similar plan, but the original design of this house has been obscured by 18th-century alterations [148–9]. At Anderson Manor [52], built in 1622, many of the traditional English architectural forms continued to be applied, and the house has much in common with Kingston Maurward Old Manor although it is a generation later in date. The plan, however, shows an improvement on the usual mediaeval 'one-room-thick' arrangement, having two parallel ranges with a common spine wall, in which the fireplaces are set back-to-back; the innovation was introduced at Glanville's Wootton (6) at the end of the 16th century but it did not become common in Central Dorset until late in the 18th century. Anderson Manor is also an early local example of the use of brick. The nearby Tomson farmhouse [90] is more antiquated in design, being planned in much the same way as the 15th-century Winterborne Clenston Manor, with the main rooms on the first floor; however, the use of brick shows that it must be more or less contemporary with Anderson Manor. The Manor House at Blandford St. Mary is another early example of the use of brick [53]. The mid 17th-century S. front of Waterston House, Puddletown, clearly in the architectural succession of Kingston Maurward and Anderson Manors, has classical details used with understanding and discrimination [52]; on the other hand the Old House at Blandford Forum [110], probably built at the Restoration, still shows the uncertainty with which country builders approached the Renaissance.

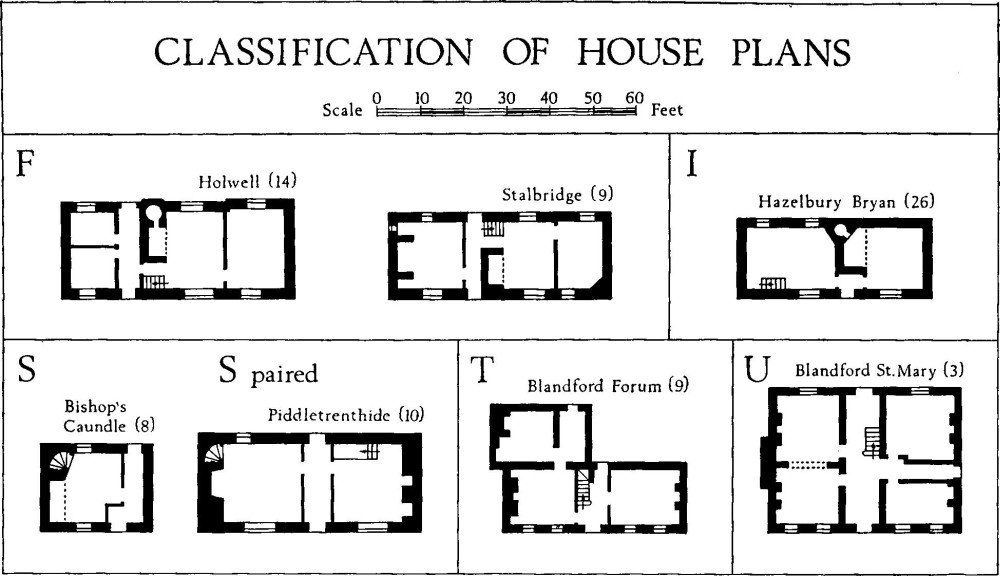

Among smaller 17th-century houses, Tolpuddle Manor [212], dated 1656, Pope's Farm, Marnhull, and the Old Rectory at Cheselbourne must be noted; they are all designed in the traditional late mediaeval manner. Dale House at Blandford Forum [112] shows that some local builders had fully mastered the classical idiom by 1689, the date inscribed on its doorway; Fontmell Parva at Child Okeford [54] is of about the same date and style, and illustrates the same point.