An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in the County of Cambridgeshire, Volume 1, West Cambridgshire. Originally published by Her Majesty's Stationery Office, London, 1968.

This free content was digitised by double rekeying. All rights reserved.

'Sectional Preface', in An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in the County of Cambridgeshire, Volume 1, West Cambridgshire(London, 1968), British History Online https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/rchme/cambs/vol1/xxviii-lxix [accessed 6 May 2025].

'Sectional Preface', in An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in the County of Cambridgeshire, Volume 1, West Cambridgshire(London, 1968), British History Online, accessed May 6, 2025, https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/rchme/cambs/vol1/xxviii-lxix.

"Sectional Preface". An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in the County of Cambridgeshire, Volume 1, West Cambridgshire. (London, 1968), British History Online. Web. 6 May 2025. https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/rchme/cambs/vol1/xxviii-lxix.

In this section

CAMBRIDGESHIRE I

Sectional Preface

Geological Map

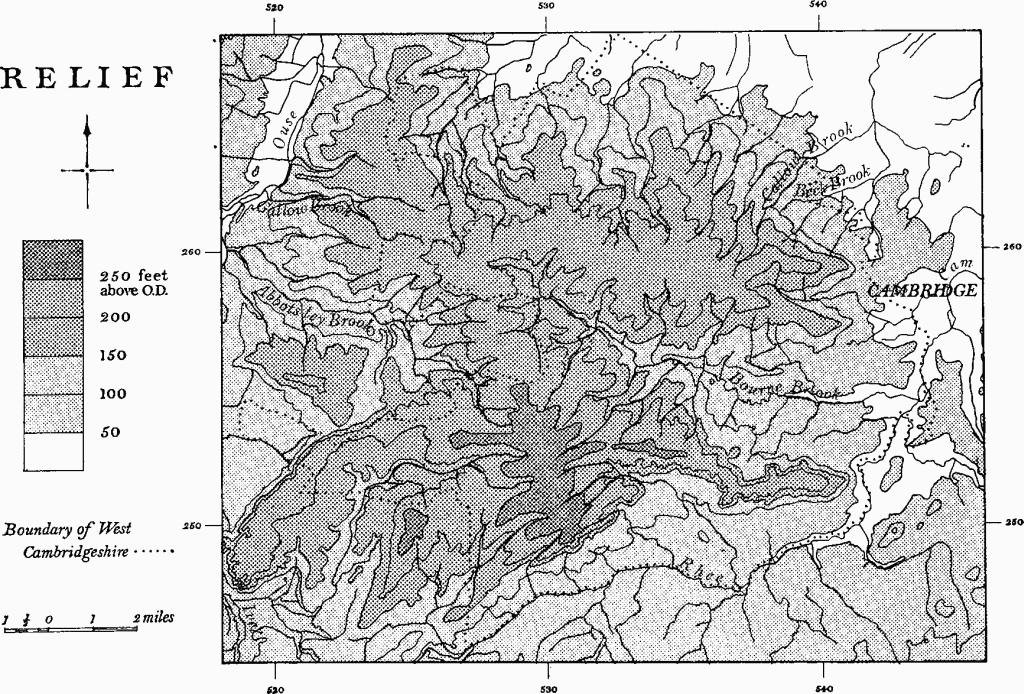

Relief Map

Natural Background

The area surveyed in this volume is roughly triangular in shape and extends from the City of Cambridge on the E. to the borders of Huntingdonshire and Bedfordshire on the W. The greater part is a gently undulating block of land between 100 and 250 ft. above O.D. The Boulder Clay with which this part is covered varies within short distances from heavy clay to light loam, with consequent changes in the soil conditions. The centre of the area is drained by the Bourn Brook, flowing roughly E., which has cut down through the Boulder Clay to expose first lighter Chalk Marl and then heavy Gault clay. On the N.E. edge of the Boulder Clay upland, the tributaries of the Ouse have also cut down through the glacial deposits to expose areas of heavy Jurassic clays; the S.E. edge of this upland is marked by a steep scarp, 100 ft. high, of Chalk Marl capped with Boulder Clay. At the base of this scarp the wide valley of the river Rhee cuts into the underlying Gault. The W. edge of the triangle is drained by tributaries of the Ivel and Ouse, which have exposed Gault and Lower Greensand around Gamlingay and underlying Jurassic clays S. of Croxton. There are narrow strips of alluvium and patches of river gravel along the valleys of the Rhee and the Bourn Brook. These areas of light soil and the chalk hill-slopes were most easily cleared and settled in prehistoric times, but place-names indicate weald ('wilds') or wooded country stretching from Croydon to Dry Drayton (Reaney, 'Place-names of Cambs.' xxvi–xxvii, 54). It is probable that much of the higher ground was at one time wooded, although by the time of the Domesday Book timber resources do not appear to have been particularly rich.

Settlement

The commonest location for villages is close to the outcrop of the junction of the Boulder Clay with the underlying solid rocks. On the N.E. slope of the Rhee valley this junction coincides with a spring line at the base of the Chalk Marl; in the valley of the Bourn Brook and on the slopes facing the Fens the locations are more commonly in the vicinity of small streams draining off the clay. Whilst the evidence is not conclusive, it is probable that villages on the clay, like the Hatleys and Hardwick, are later and were associated with the clearance of the woodland.

Village Morphology

It is of interest that many of the villages retain distinctive plan forms which are of considerable age, although no historical significance can at present be adduced from this observation. The most striking of these is Barrington, which lies around an elongated oval green, now partly enclosed, of about 33 acres. Closes or crofts with narrow frontages fringe this green, and the earliest surviving houses, (5) and (17), are set back from it. Smaller greens survive at Eltisley and Kingston, both being within the irregular intersection of early route-ways and now somewhat altered by encroachment. At Orwell, the former existence of a green is inferred from the topography on a 17th-century map. On the evidence of their existing lay-out, Caxton, East Hatley, Gamlingay, and Haslingfield may also have had central greens. That at Comberton appears to have been little more than a widening of two intersecting streets to allow for a variety of routes in bad weather.

At Tadlow, the old village street is integral with a rectangular field system which has its axis parallel to the valley side. On the W. the parish and county boundary respects this field pattern, for which an early date may therefore be inferred. Other rectangular field arrangements have been recorded in and around the villages of Dry Drayton, Grantchester, Graveley, Great Eversden and Toft.

What may be evidence of village growth away from an old centre can be seen in the way that crofts extend along a road or stream out of a village. This pattern occurs adjacent to the Barrington road at Orwell, along the Brook at Bourn and S. of Little Gransden. The adjoining street villages of Arrington and Caxton both appear to have taken shape in late mediaeval times, as the result of migration from nearby centres, now indicated by the locations of the parish churches.

Parish Boundaries

The pattern and shape of the parish boundaries in the area are evidence of the settlement history. The boundaries often follow natural features such as streams, for instance Bourn Brook; in other places, they coincide with man-made elements in the landscape such as the edges of furlongs in the mediaeval open fields (e.g. between Caxton and Eltisley), or roads, as at Lolworth where the S. boundary butts up against a former road between Dry Drayton and Boxworth. It has already been noted that part of the W. boundary of Tadlow is secondary to the field lay-out. Further N. the boundary is marked by a low bank, which follows a straight course for two miles, and it is probable that it was defined prior to the clearance of the woodland. The effect of modern adjustments is often to obliterate topographical evidence, as at Papworth Everard, around N.G. TL 281635, where the old boundary reflected a detour away from Ermine Street.

Documentary and place-name evidence for the creation of new parishes by subdivision can often be confirmed from study of the boundaries. Bourn and Caldecote, Great and Little Eversden, Grantchester and Coton, Hardwick and Toft, Lolworth and Childerley, were all probably once single parishes. The subdivision of the former woodland area in the vicinity of Hatley is of interest. The parishes of Hatley St. George, East Hatley and Cockayne Hatley (Bedfordshire) may have been formed from the upland ends of parishes on the edge of the Rhee valley. Pincote, now part of Tadlow, appears to have been an independent settlement in a similar position which did not achieve parochial status. Irregular boundaries suggest that the distribution of available woodland was considered when subdivision took place, e.g. between Toft and Hardwick around N.G. TL 353575. A spring, the Nil Well, in a rather dry area, is shared by Graveley, Papworth St. Agnes and Yelling (Hunts.). Five parishes converge on a maypole, probably also the hundred moot, at about N.G. TL 367515 on Orwell Hill. The ridgeway road from Cambridge to Eltisley is a parish boundary for much of its length, and minor variations may reflect the width of the old track before modern surfacing. Two comparatively important houses in the area, Tetworth Hall, Gamlingay (42), and Manor Farm, Papworth St. Agnes (2), straddled the county boundary with Huntingdonshire.

Roads and Trackways

The Boulder Clay upland is intersected by a number of old trackways, few of which are now continuous for any distance although their length can be extended from the evidence of place-names and old maps (cf. Reaney, 'Place-names of Cambs.', 18–33; Fox, Arch. Camb. Reg., 141–158).

Cambridge, at the lowest convenient bridging point of the River Cam, was already a focus of routes during the Roman period, and roads from Wimpole Lodge and from Godmanchester, both of which remain in use today, were laid out then. The ridgeway from Caxton Gibbet to Cambridge, now the third main road to the W., may also have been in use at this time, but no evidence has been found for Roman metalling. Two other roads of this date run N. to S. in the W. part of the area. One, from Godmanchester to Sandy, is presumed to cross the W. part of Gamlingay but has not been located in the field; the other is the Ermine Street or Old North Road. The importance of this main route from London to the North seems to have fluctuated a number of times before it was finally replaced by the W. route through Sandy and Buckden. Records of royal progresses suggest that the latter was in use in the reigns of John and Henry III, and the mediaeval field pattern at Caxton includes strips which appear to have straddled the Roman line. The revival of Ermine Street is probably related to the rise of Royston (V.C.H., Herts. III (1912), 254) and the improvement of the bridge at Huntingdon. It is reflected in the growth of Caxton as a staging town with a number of inns and a posting station. In 1663 a stretch of Ermine Street in Hertfordshire, Cambridgeshire and Huntingdonshire was the subject of the first turnpike act. The preamble stated that 'the road is very ruinous and becomes almost impassable' and puts the blame on 'the great and many Loades which are weekly drawn in waggons ... as well as ... the great trade of Barley and Mault that cometh to Ware and so is conveyed by water to the City of London'. By 1820 the three western main roads from Cambridge had also been turnpiked, together with that from Gamlingay to Papworth, and under an act of 1826 a turnpike was instituted from Arrington to Tadlow, much of it being a new road.

Building Materials

Of the building materials used in the area local sources provided timber, field stones, clunch, carstone and thatch; limestones, alabaster, slate and lead are among the more commonly found imported materials. Brick, perhaps originally imported from the Netherlands through King's Lynn, was made in the area at least as early as the 16th century.

In mediaeval times, wood was, with a few exceptions, the usual material for the walls of secular buildings in the area. Surviving churches are of stone except for adjuncts, such as the wooden porches at Little Eversden and Grantchester, which are mediaeval or of mediaeval origin. The number of stone towers which are later than the body of the church may suggest that wooden towers, or at least bell turrets, were once usual. Certain of the later mediaeval fabrics include small fragments of 11th- or 12th-century stonework, and where this is altogether absent, the possibility of a timber predecessor should not be dismissed. The scantling of timber in mediaeval secular buildings is generally less than in those of N. Essex and W. Suffolk, suggesting that local sources were comparatively limited, a conclusion which is corroborated by the quantities recorded in the Domesday survey. The timber used in such early structures as Manor Farm, Bourn (8), and The Old Rectory, Kingston (3), is of this light scantling. Comparatively prodigal use of timber is a feature of some 16th-century framed structures. A possible explanation is the release of the reserves which had belonged to the religious houses and chantries. Although oak is usual, other sorts of wood occur (cf. R.C.H.M., Cambridge, 346). At Madingley (2) the large mast-like newel of softwood, in the 16th-century stair turret, was presumably imported. Beams of pine or deal are also occasionally to be seen. These extraneous timbers could have reached the area from King's Lynn where Baltic or Scandinavian timber has been found in domestic roof-construction of the 14th century.

It was in the parish churches that stone first made its appearance as a building material in West Cambridgeshire. The body of the walling is usually of glacial erratics, known as field stones, taken off arable land. Freestone dressings were used for external features such as windows, quoins, plinths, buttresses and parapets, and internally for piers, arches and the like. Two native stones used for this purpose in West Cambridgeshire were clunch and carstone. Clunch, in this area, comes from the harder beds of the Lower Chalk, although elsewhere the same word is used for similar material from other strata of the Cretaceous; quarries or pits survive at Barrington, the Eversdens, Harlton, Haslingfield and Orwell. Carstone comes from the Lower Greensand, which is exposed in Gamlingay and Little Gransden. Clunch, reputedly employed by the Romans, was used widely from the 12th century onwards both for walling and for dressings; its weathering properties varied but the better quality stones were resistant to deterioration. The commonest extraneous stone used for dressings in the mediaeval period was Jurassic limestone, much of the earlier work being in Barnack or a similar freestone.

Apart from the plinths of framed structures, which are sometimes of field stones, and one or two external chimneys, such as one of carstone at Gamlingay (9), little stone occurs in lesser secular building before the 18th century, when clunch comes into use. The Old Rectory, Kingston (3), Kingston Wood Farm, Kingston (12), much of which may have been originally of field stones and clunch rubble, or Manor Farm, Papworth St. Agnes (2), where there is reused stone from a monastic or other religious source, were large in comparison with the other buildings of their time.

Brick was the most common alternative material for timber in secular buildings. The earliest evidence for its manufacture locally is in the will of Anthony Mallory of Papworth St. Agnes (PCC 32 Dyngeley), dated July 1530, which provided for a bequest to Randoll Lynne of as much brick as he should need for making a chimney at his farm in Graveley from the testator's 'brikkyll in the field at Papworth'; the residue of brick was bequeathed to his wife Alice 'for her necessary and nedeful reparacion and bylding to be made upon the said manor', and to his son Henry. A field at N.G. TL 267656, shown as 'Brick Walk' on the tithe map of 1839, is further evidence for brick-making in the parish. Such field names are frequent. At Hatley St. George, a map of 1601 shows a 'Brick Close' immediately W. of 'Mr. St. Georg his house' (Hatley (3)) and, to the N., 'The Brickkyll upon ye Queen's Land', traces of which, or of its successor, are to be seen on the ground (Hatley (11)). At Childerley a field called 'Brick Clamps' is known from a sale prospectus dated 1842 of Childerley Hall, Childerley (1); it can be traced back to 1686, and may be older.

Building accounts, dated 1509–11, for work done by Christ's College on their estate at Malton, include payments to bricklayers; the chimney on the S. side of the hall range at Malton Farm, Orwell (24), may include brickwork of that date. The entrance doorway to Kingston Wood Farm, Kingston (12), which is of brick, is early 16th-century. The E. front of Madingley Hall, Madingley (2), c. 1543, is the earliest brickwork of any extent surviving in the area. After the middle of the 16th century brick was used increasingly. Red brick was general up till the end of the 18th century, when white brick made its appearance in the area; Tudor white brick, as at Jesus College, Cambridge, or Hengrave Hall, Suffolk, has not been recorded. Throughout the first half of the 19th century, white brick was gaining popularity, and by 1850 red brick was largely confined to a few localities, among which Gamlingay is notable. Red bricks with vitrified heads were usual in the 16th century; the variation was exploited decoratively as 'diaper' or similar patterning, for example at Madingley Hall and the Manor Farm, Papworth St. Agnes. The size and shape of bricks varied according to foreign fashion and the vagaries of fiscal policy, especially in the 18th century. The 19th-century bricks of unusual design and exceptional size, found at Arrington and Bourn, were probably estate-made. There are elaborately decorated chimney stacks of 17th-century origin at Bourn Hall, Bourn (2), of the kind often described as 'Tudor'.

Clay bats, that is to say comparatively large blocks of a material resembling cob, were used for smaller dwellings, utilitarian buildings and boundary walls; most are 19th-century. Occasionally rather larger houses (e.g. Comberton (22)) are predominantly of these bats or 'lumps'; prefabricated nesting boxes for pigeons at Toft (6) are of the same material and somewhat earlier. The constituents seem to be a chalky clay and chopped straw or other dry vegetable matter. A common size is 18×9×5 ins.; they were used in combination with ordinary brickwork or a light timber framework, and were generally plastered inside and out.

The traditional material for roof covering in West Cambridgeshire is thatch or tile. Whilst no church in the area retains its thatch, in 1593 that at Arrington was described as lacking 'covering with rede', and at Orwell the churchwardens reported in 1544 that the thatch on the church roof was in need of repair (Cambs. and Hunts. A.S., Trans. V (1935), 263). At Arrington, the continuous roof of the nave and chancel, which is completely ceiled, may be original; its pitch is reflected on the E. face of the W. tower, added c. 1300, in a weathercourse about the thickness of a covering of thatch above the existing tiles. On the edge of the fens at Rampton and Long Stanton (St. Michael's), both within a few miles of West Cambridgeshire, thatched church roofs have survived. The nave at Rampton has a queen-post roof similar to those at Hardwick (Plate 52), where there is a redundant weathercourse on the tower, and to that at Arrington. Coton (Plate 62) shows the same feature. Churches of the 13th century and earlier were sometimes tiled, and at Bourn a covering thinner than thatch is indicated by the position of the weathercourse on the tower and its relationship to the clearstorey windows. The importance and wealth of Bourn may have made the use of an expensive material possible. Elsworth and Harlton, both 14th-century, seem to have been designed to receive lead-covered roofs, and some aisles of 13th-century origin, for example the S. aisle at Barrington, may have been leaded from the start. The introduction of lead as a roof covering, making possible a flatter pitch, was associated with structural modifications such as the addition or heightening of clearstoreys, and the widening and heightening of aisles; at Coton (Plate 62), the heightening of the S. aisle in the later middle ages is indicated by a change in material and by the low diagonal S.E. buttress.

Before the introduction of lead, aisles of the width of Coton or Little Gransden probably had a series of transverse gables to give height to the doors and windows. A number of such gablets may have been built in Cambridgeshire during the 13th century, although none survives. The aisles at Long Stanton, (St. Michael's), just out of the area, have transverse gablets which, though modern as they stand, probably reproduce old features.

For the roofs of lesser secular buildings, tile is a common replacement for thatch. The pitch required by both coverings is similar and it is not always possible to determine for which material the roof was designed. The lost S. aisle of the hall of The Old Rectory, Kingston (3), is known to have been thatched, the pitch and thickness of which are clearly indicated by a diagonal band of unplastered masonry on the E. wall of the 14th-century cross wing (Plate 101). Some houses of mixed construction having brick gable ends with generous parapets were presumably designed for thatch, but most are tiled today.

A few larger 18th-century houses (e.g. Wimpole Hall and Hatley Park) are roofed today with Westmorland or similar slate. The introduction of Welsh slate during the first half of the 19th century influenced developments in the design of smaller dwellings. The growth in popularity of houses planned in double depth or double pile (see below: Class U) is related to the gentler pitch of roof structure made possible by the new material. Before that time, houses of this class were roofed in a variety of ways, all of which were complex and correspondingly expensive. With slate, other house types (e.g. Coton (6), Plate 32) could also be roofed more economically, and older dwellings, either open to the roof or with low attics, could be heightened to create bedrooms by raising the walls without altering the position of the ridge. Slate was also used in churches, but there were no comparable structural consequences.

A rendering of plaster was widely used both to simulate stonework in an original design, as on the surrounds to the brick windows of Caxton (8), and to give a weatherproofing surface to less pretentious buildings in clunch or timber framing. In the 19th century Roman cement was employed for this purpose for the repair of architectural detail, especially in churches; at Harlton, head stops were moulded in this material.

In the earlier middle ages, Jurassic limestones were general for coffin lids and effigies. With the exception of a floor slab at Tadlow, which is in a hard white stone, later floor slabs are usually in a shelly marble similar to Purbeck, although the quarry at Alwalton in Huntingdonshire is a more likely source for this area. Mediaeval alabaster, presumably from Nottinghamshire, occurs in fragments from a large sculptural group at Toft (Plate 13); this material was also used in early 17th-century monuments at Harlton (Frontispiece) and Madingley. For the rest there is a wide range of extraneous marbles and other stones in monuments and floor slabs of the 17th to the 19th centuries.

Ecclesiastical

The ecclesiastical buildings of West Cambridgeshire consist for the most part of parish churches, with a few Nonconformist chapels of little architectural interest. Domestic chapels, such as that serving almshouses at Gamlingay (21), or that at Wimpole Hall, Wimpole (2), have been described with the secular monuments of which they form a part, and so has a putative chapel in an attic at Papworth St. Agnes (2).

There are 37 modern parishes, but Hatley, recently formed by the amalgamation of East Hatley and Hatley St. George, has two churches, while Childerley, an earlier amalgamation, has lost the churches of both Great and Little Childerley, a chapel in the grounds of the Hall being now the sole place of worship. Churches have also disappeared with the former villages of Clopton (Croydon (15)), Malton (Orwell (24)) and presumably Whitwell (see Barton, p. 12) and Wratworth (see Wimpole, p. 210); the sites of the first two only are known.

No standing remains of religious houses exist, but one earthwork, Longstowe (14), has been identified as the site of a mediaeval hospital.

Characteristically, churches in the area lie among or adjacent to the houses, and exceptions are probably the result of a shift in population. At Caxton, and probably also at Arrington, there has been migration toward the Ermine Street from the original settlement, which was a short distance to the W.; at Croxton, as at Wimpole, the isolation of the church is the result of emparking and the rebuilding of the village elsewhere. As Fox points out (Arch. Camb. Reg., Map 5) Comberton church lies with Toft and Caldecote on an E. to W. trackway which has been abandoned in favour of an alternative route.

The churches of Barrington, Haslingfield and Gamlingay probably occupy positions on village greens which have been reduced in extent by their churchyards and other enclosures. The determining factor of the siting of Coton, and of Eltisley where there was formerly a well dedicated to St. Pandionia (Pandona), may have been a spring. At Bourn there is a typically Norman association of church and castle. The small church at Tadlow seems to post-date the field and village-street lay-out.

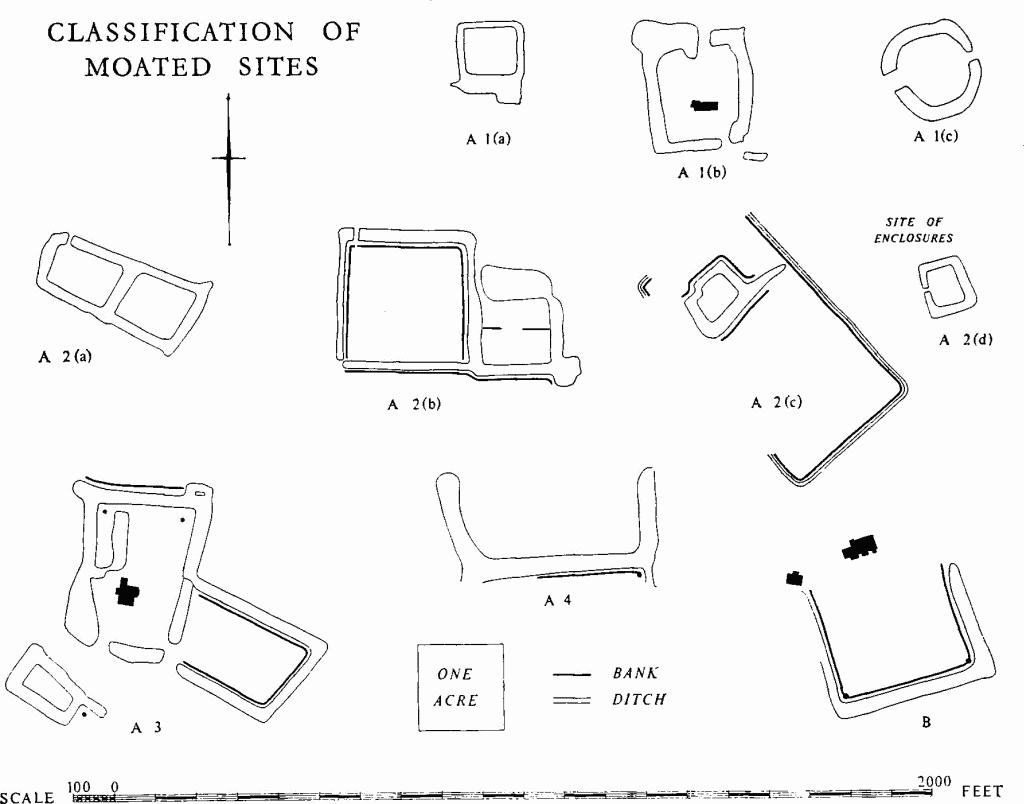

The majority of the churchyards are rectangular, with banks and ditches of indefinite age, some almost substantial enough to qualify as moats, e.g. at East Hatley (Hatley (18)). Croydon is one of several places where the churchyard is a levelled platform; the tower has been affected by subsidence, apparently due to the made-up nature of the ground. The churchyard at Grantchester has a mediaeval boundary wall and several others have old walls. Churches are commonly placed more or less in the middle of their churchyards but at Elsworth and Haslingfield the churchyards are irregular and hardly extend to the N. beyond the structures. In both cases the explanation seems to be that the churches and their churchyards were originally small; subsequent extensions have involved encroachment on neighbouring roadways, and subsidence has resulted which, in the case of Elsworth, has necessitated the total rebuilding of the N. aisle. The tower at Conington is also built over or against a decayed village street on the W.

The churches follow a basically uniform plan; a three-cell arrangement made up of chancel, nave and W. tower is usual, though aisles and porches are common elaborations. Papworth Everard, which has a modern tower on the N. side, lost its W. tower in 1741, and E. Hatley has never had more than a W. bell-cote. Most of the towers are additions, although some churches were rebuilt, like Arrington in the 13th century, to a design in three parts carried out in a single extended operation. An important early exception is Orwell, where the base of the tower is 12th-century and bonds with the W. wall of the Norman nave. The archaeological complexities associated with the addition of a tower at the W. end are well illustrated in several cases. At Grantchester a tower was added c. 1400 a short distance W. of the 11th-century nave, which was then lengthened to effect a junction. At Caxton and Little Gransden the E. wall of the tower was built up on the earlier W. wall of the nave, but at Bourn the W. wall was largely removed in preparation for a new tower of exceptional size. Thickening of the existing W. wall was resorted to at Madingley and perhaps at Gamlingay. At Tadlow, the addition of the tower was complicated by an effort to correct the faulty orientation.

Evidence of the addition, heightening or widening of aisles has survived in a number of churches. The 12th-century quoins of unaisled naves survive at Coton (Plate 62) and at Orwell, aisles having been subsequently added at both. At Coton the S. aisle walls have been heightened, as were those of the low and narrow S. aisle at Little Gransden. At Barrington, evidence for the widening of the N. aisle of the nave in the 14th century can be seen at its E. end, where two windows are strangely juxtaposed. Transeptal chapels are found at Croydon, Eltisley and Tadlow, and others have been removed at Grantchester and Longstowe. They are a more ambitious feature at Bourn and Gamlingay, although at neither do they interrupt the clearstorey. At Barrington the chapels are in the position of outer aisles, to the E. of the porches. A room on the N. side of the chancel of the church at Orwell is probably a sacristy and there are indications of a similar annexe at Kingston and elsewhere. Three churches, Arrington, Graveley and Lolworth, have been reduced in size by the removal of aisles since the Reformation (Plate 11).

The relation of roofing materials to the provision of clearstoreys has already been discussed. The steeply pitched roof at Bourn, which has a late 12th-century clearstorey, probably had a covering of tiles or stone slates. At Elsworth the church, which is of the first half of the 14th century, has an original clearstorey with quatre-foiled circular lights over the piers; Haslingfield, a generation later, is similarly arranged, but the windows are square-headed. The sequence is continued at Barrington and Little Gransden, where there are windows over the arches. Harlton, of the second half of the 14th century, has a hall-type nave with lofty and slender piers designed to include the aisles spatially, and without top lighting (Plate 92). A number of other churches have clearstoreys with two-light windows of indeterminable date. Comberton is the only late example of any pretensions; the four-centred windows each of three cinque-foiled lights are quite large and presumably coeval with the N. arcade.

Whilst some churches (e.g. Croxton) retain elements of a simple and early type of plan, no structural remains have been found which can certainly be ascribed to a date before the Norman conquest. Part of the walling of the chancel at Barton and of the nave at Grantchester is likely to be 11th-century, and there is a possibility that the nave at Boxworth is of the same period. Dressed stonework of this date includes some jamb-stones of a doorway at Grantchester and a small opening, hardly large enough to be a doorway, at Barton. Carved or moulded fragments of small windows having monolithic round heads are to be seen at Boxworth and Grantchester (Plate 4), but none is in situ. Displaced stonework in other churches includes four fragments carved with interlace at Caxton, Conington, Grantchester and Orwell, probably all fragments of coffin lids, and what is apparently a small baluster, cut down, at Caxton. None is necessarily pre-Norman.

Apart from the remains and fragments described above, all of which could be ascribed to the SaxoNorman overlap, identifiable work of any importance earlier than c. 1200 is confined to some half a dozen churches, of which the earliest may be at Coton. Here the design of the chancel, with windows having nook shafts inside and out, resembles that at Stourbridge Chapel, Barnwell, which has been assigned to the mid 12th century (R.C.H.M., Cambridge (62)). The surviving S.E. quoin of the nave at Coton (Plate 62) and the similar W. quoins of the nave at Orwell may be contemporary. The chancel at Haslingfield retains a short length of external string-course with saw-tooth or axe-work ornament closely resembling that on the string-courses of Stourbridge Chapel, and may also be placed in the mid 12th century. The most important 'Transitional' work of the later 12th century is at Bourn. Were it not that there are no traces of a stone castle at Bourn, it would be tempting, on the analogy of other 12th-century churches adjacent to castles, to think of the nave as a parergon by masons engaged on improvements to Picot's original stronghold. The extra elaboration of the piers, with their scalloped capitals, on the S. side and the fact that the N. aisle may not have been completed until some considerable time after the S. aisle, suggest a possible relationship between church and castle. The arcades and S. doorway at Eltisley, likewise 'Transitional', can hardly have been built much before the end of the century although the stocky proportions of the piers and plain treatment of the pointed arches in a single order look primitive.

Architectural fragments ascribed to the 12th century have been noted at Croxton, Elsworth and Little Gransden, and with less certainty at Graveley, Lolworth and Madingley. To these should be added the evidence of fonts at Arrington, Coton, Croydon, Madingley and Orwell. The presence of a 12th-century font at Coton is unexplained in view of the late date at which parochial status was apparently granted. The possibility should be considered that it was brought from elsewhere, as is alleged of the font at Madingley, though for reasons which are not conclusive. Thus there is some evidence for the existence in the 12th century of stone-built churches or chapels, on or near the sites of the present buildings, for less than half the villages of the area, but the number was probably greater.

The majority of parish churches in West Cambridgeshire contain some work of the 13th century when many were substantially rebuilt. Three of the largest, Gamlingay, Barrington and Haslingfield, were planned anew, on an ample scale, in the second half of the century, but in each the work was carried out piecemeal and continued into the next century.

At Gamlingay the nave arcades are in a simple idiom with arches of two chamfered orders carried on octagonal piers having moulded caps and bases. Differences between the two arcades and between the piers and their responds indicate a time lag, and the detail suggests that work was protracted into the 14th century, when transeptal chapels were added. The unadorned stonework was offset by architectural painting, some of which survives, to counterfeit costlier materials. The 13th-century remodelling of Barrington is similarly characterised by minor discrepancies in the treatment of the arcades. The work is more ornate than at Gamlingay, with quatrefoil piers having moulded caps and bases, some of the former carved with nailhead ornament; the arches are in two orders but the double hollow chamfers create a more lavish impression. Traces of painted scroll-work, probably contemporary, have been recorded beneath later mediaeval figure subjects. Haslingfield was rebuilt somewhat later than Gamlingay or Barrington, although a beginning was made before the end of the 13th century when the chancel arch was refashioned and the nave adumbrated by the four responds. The detail of the arcades has affinities with Barrington, but progress appears to have been slow and the S. arcade is noticeably later than the N. A further period must have elapsed before the aisles with their fine 'Decorated' windows were glazed; the fan tracery on the S. side is ostensibly later than the reticulated tracery on the N. The hesitant manner in which all three of these projects was executed is in marked contrast to the precision which is so noticeable and characteristic of parish church building in West Cambridgeshire and elsewhere from the mid 14th century onward.

Other churches with 13th-century arcades are Arrington, Comberton, Croxton, Dry Drayton, Graveley and Little Gransden. The last mentioned is substantially of the mid 13th century, except for the tower, and though restored, retains some plate tracery. The narrow S. aisle is largely original and although the low long wall, which included a gablet for the S. door, has been heightened, the original roof line is clearly traceable. The work in these smaller churches, though usually of good craftsmanship, tends to be economical, with chamfered arches and with simply moulded caps and bases to octagonal piers of clunch and freestone. However, the blocked N. arcade at Graveley, of the second half of the century, was sophisticated, and there are occasional signs of comparative affluence, such as the rear-arches of the E. window in the N. chapel at Eltisley and of the W. window in the S. aisle at Croxton.

The aisleless church at Tadlow, but not the added tower, is of the mid 13th century; that of East Hatley is later. Both have been heavily restored and the latter is now derelict. Further works of the 13th century include the tower at Bourn and the chancel at Caxton. The former incorporates stonework which has been affected by burning both before and after construction, possibly as a result of civil commotion in 1266. Generous in scale and assured in design, despite its deformed wooden spire, Bourn tower (Plate 49) must rank as the most considerable construction of the 13th century in West Cambridgeshire. By contrast, Caxton chancel is pedestrian, but has side windows with elegant geometrical tracery in developed 'Early English' style.

Barton church, remodelled about 1300, has window tracery resembling that at Caxton, but the quatrefoils in the tracery heads are placed on a vertical instead of a diagonal axis, foreshadowing the reticulated pattern which was to dominate the 'Decorated' style for the next generation or two. The most important work of the first half of the 14th century is the nave at Elsworth (Plate 74) where the 'Decorated' idiom is fully developed. The scroll mould is a common factor with Barton, but the hollow chamfer has been almost completely discarded. The piers are filleted quatrefoils on plan, with small rolls between the foils; the windows, except for one of experimental design in the S. aisle (Plate 5), are uniformly reticulated. Elsworth, with lofty arcades, generous aisles and low clearstorey lit by roundels, has affinities with three other Cambridgeshire churches—Bottisham, Isleham and Trumpington. The proliferation of wave moulds on the two orders of the arches and the lifeless and mechanical handling of the design as a whole suggest that Elsworth should be placed late rather than early in this local sequence. More or less contemporary with Elsworth are the nave arcades at Orwell, the S. arcade at Coton, and the N. arcade at Madingley. These are all relatively low and were presumably inserted into the older fabrics without disturbing the main roofs.

At the end of the series comes the chancel at Grantchester. The flowing tracery of the S. window (Plate 69) and that of the side windows (Plate 10), in which reticulation is alternated with a pattern based on four quatrefoils in a large circle, resembles work of the first half of the century, but some of the internal detail, such as the shafted splays and the emaciated double niches (Plate 71), may indicate a later date, though hardly as late as 1384, which a documentary reference suggests.

The transition between the styles traditionally described as 'Decorated' and 'Perpendicular' is well illustrated at Harlton, a church almost entirely of the second half of the 14th century. The chancel has broad windows with two-centred heads filled with early vertical tracery; that in the E. window (Plate 69) occupies half the total height and combines upright panels with others formed by intersecting tracery bars. It bears a very close resemblance to the E. window at Ashwell, Hertfordshire, for which a date c. 1370 has been widely accepted (R.C.H.M., Herts., 38; N. Pevsner, Buildings of England, Hertfordshire (1953), 41); a similar dating is here to be inferred. The nave at Harlton is stylistically quite different from the chancel, but is likely to be contemporary. The elegant interior (Plate 92) embodies a solution to the problems of design evident at Elsworth by the mid 14th century and arising from the need to provide a large well-lit space. This development probably arose directly or indirectly out of the increased emphasis on preaching. The clearstorey lighting has been eliminated in favour of an arcade of more slender proportions than those of its prototypes. The aisles are lit by tall windows divided by transoms, some embattled, and having four-centred heads. Most of the tracery is vertical, although the E. windows, otherwise similar in design, have a variety of branching reticulation, which is an element in the E. window at Grantchester (Plate 69) and of which the W. window of St. Michael's in Cambridge (R.C.H.M., Cambridge, 284) is probably the earliest example in the district. The piers and arch moulds at Harlton are in part continuous and of a refinement verging on the finical; they are not unlike those of St. Edward's, Cambridge, but the arches are less pointed and the composition as a whole is more generous.

The chancel at Orwell, which has been extensively restored, was built in the last years of the 14th century as the framework for an elaborate ensemble, which included painting, sculpture and glass, in memory of Sir Simon Burley who had been executed in 1388. The side windows are of the same design as those in the aisles at Harlton, with embellishments such as embattled transoms and internal labels with carved stops. The similarity of the tracery at Harlton to that at Orwell, which has been closely dated, confirms the ascription of the former work to the two decades 1370–90. Of comparable style and date are the doorway and windows in the remodelled N. wall of the nave at Grantchester which may be regarded as contemporary with the tower; the W. doorway, now converted to a window, bears the arms of John Fordham, Bishop of Ely from 1388 to 1426.

The stylistic dating of church architecture of the period 1350–1530 in the area, as elsewhere in East Anglia, is fraught with difficulty. Much of the work was a remodelling of older structures, and the openings and other details introduced are commonly of an economical, even impoverished, quality, revealing little stylistic progression. The emergence of local schools and the stagnation in design aggravate the difficulty. Surprisingly few documentary references to building activities during these 180 years are known, and much work within this period has therefore been described in the inventory as 'late mediaeval'. Any closer date that may have been ventured should be regarded as tentative. Exceptionally at Gamlingay documentation has indicated that the chancel was being refurbished in 1442–3 and, judging from the similarity between this work and that in the body of the church, the latter may also be ascribed to the middle of the 15th century, a date confirmed by the fact that the N. chapel is known to have been restored by Walter Taylard (d. 1466). The windows are of three or more graduated cinquefoil lights in depressed four-centred heads and have at most perfunctory tracery. Other features include occasional sculptural detail in the form of label stops and gargoyles; in the absence of the documentary evidence much of this work might have passed as 16th-century, when not dissimilar work was being done elsewhere.

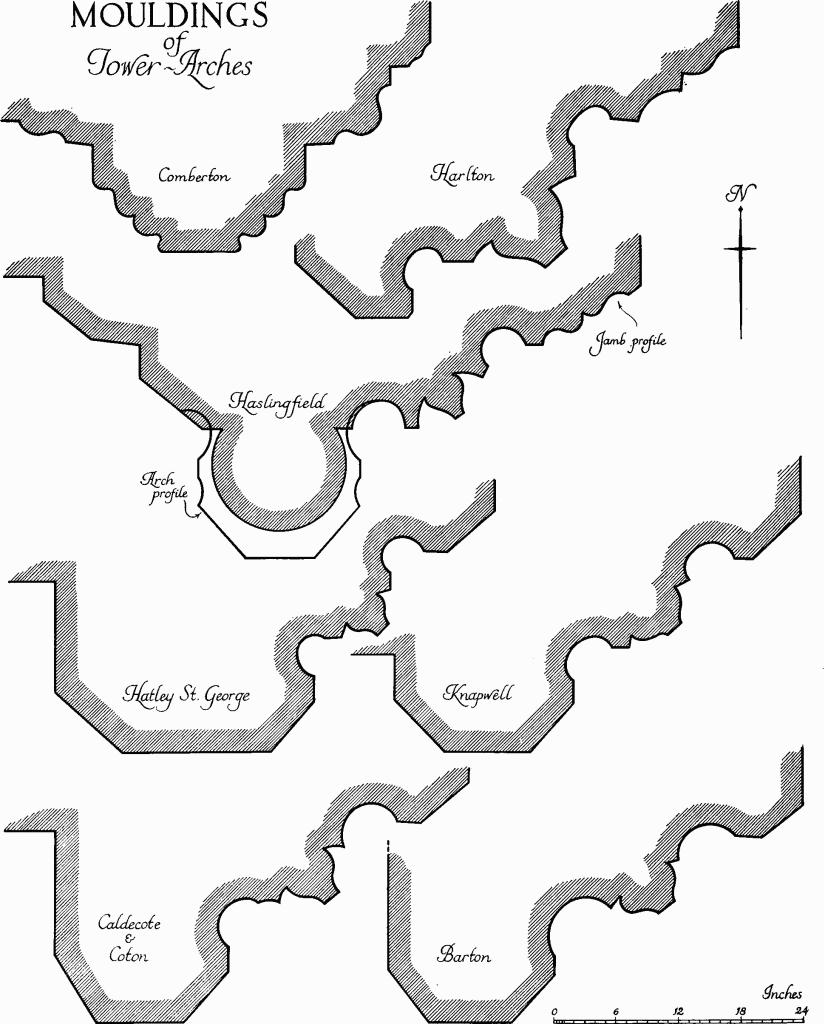

Mouldings of Tower-Arches

The majority of the W. towers of churches in the area were, as already indicated, added to earlier naves; they were mostly built in or after the later 14th century in the 'Perpendicular' style. The problem of the development and dating of these towers constitutes a special study, particularly in connection with the arch mouldings. Twelve have distinctively tall arches of two or more chamfered or moulded orders continuous with the responds. Five of the arches, at Barton, Caldecote, Coton, Hatley St. George and Knapwell, are almost identically moulded in three orders to the E.; the middle order is a filleted bowtell flanked by narrow and deep casements, and the other two are chamfered. These five towers form a group, having other features in common, such as similar belfry windows.

The local prototypes of the continuously moulded tower arches are found at Comberton and Elsworth in the 14th century. The arch at Comberton is relatively short and wide and has a repertory of mouldings which includes a wave mould suggesting a rather retarded date for other details such as head stops, ball flower and reticulated tracery. The Elsworth arch, which is not actually continuous although it has no imposts or capitals, tends to the more slender proportions which are logically consequent upon the provision of a clearstorey and which permit in turn a comparatively tall W. window. Here the window has three lights with reticulated tracery; the three orders of the arch are wave-moulded.

The tower at Harlton was probably remodelled at the same time as, or soon after, the nave was rebuilt in about 1370–90. The mouldings are a more elaborate version of those used in the Coton group, with a triple fillet to the central bowtell; the flanking casement mouldings are only slightly wider and shallower than three-quarter hollows. The Coton group is likely to be slightly later than Harlton, but both may be of the late 14th or early 15th century. The tracery of the tall four-centred W. window at Coton is a simplified version of that in the aisle windows at Harlton and in the chancel windows at Orwell. This would indicate a date of c. 1400, notwithstanding the evidence of a scratching of 1481 on the S. respond (Plate 16). Of the remaining towers with arches of this kind, those at Conington and Kingston have continuous chamfers, whilst those at Little Eversden and Lolworth are moulded. At Lolworth the mouldings suggest a fairly advanced 14th-century date, which is confirmed by the tracery of the W. window. Those at Little Eversden include both the wave and the three-quarter hollow or deep casement, and at Grantchester, where the tower is securely dated between 1388 and 1426, the same two components are found. The later mediaeval towers have arches with the inner order carried on attached shafts with moulded caps and bases, the other orders being continuous. The largest and finest of the later towers is that at Haslingfield (Plate 94). The lofty arch is moulded in three orders, the inmost rising off part-circular attached shafts; the series includes a double ogee, a casement scarcely developed beyond a three-quarter hollow and a filleted bowtell, as in the Coton group. These mouldings and the mannered W. window (Plate 10), with tracery based on 'straight-sided reticulation', suggest that construction of the tower had at least been begun during the closing decades of the 14th century. Part-circular attached shafts with double ogee and casement mouldings also occur in the smaller towers at Croydon, Graveley and Tadlow, but the casements are shallower, indicating a somewhat later date. Little Gransden tower, while in no sense a rival to Haslingfield, has both scale and character, which once may have been enhanced by a stone spire. The unusually generous top stage has belfry windows with a type of 'straight-sided reticulation' often ascribed to the reign of Richard II, and the pointed W. window suggests a similar early date.

On the basis of this analysis of arch mouldings in these later mediaeval towers, it appears that the group having continuous arches and responds overlaps with that having shafted responds, the latter being perhaps somewhat later in date, and that the bulk of both groups may be dated within the period 1377–1422. This short period, evidently one of great activity (see for example Fittings, Screens, below), may well include much of the 'Perpendicular' work in the area, but the evidence is far from conclusive.

Stone spires survive at Conington, Coton, Eltisley, Hardwick and Madingley, the last rebuilt. All are octagonal, rise from behind parapets, and have one or two tiers of windows in gablets. They lie N. and W. from Cambridge and should presumably be regarded as outliers of a main concentration centred in the limestone country. The majority of West Cambridgeshire churches no doubt had wooden spires, one or two of which survive in a modified form.

No complete church of the post-Reformation age exists in West Cambridgeshire. The chapel at Childerley, of 1600–09, replaced two mediaeval churches and was itself intended as a church, but it was not accorded parochial status. It is brick-built in a 'Perpendicular' idiom without the Mannerist overtones with which the survival of this style came to be associated during the succeeding decades. Subsequent alterations have obscured the original internal arrangement, but a western gallery has been inferred. The church at Croxton was embellished c. 1622 and later in the century by Edward Leeds (d. 1679). The chancel at Boxworth was remodelled c. 1640 and that at Croydon seems to have been commissioned by the second Sir George Downing (d. 1685). In 1748–9 Henry Flitcroft rebuilt all but the N. chapel at Wimpole; 18th-century rebuildings at Conington and Graveley were confined respectively to the nave and the chancel.

Church building and restoration in the early 19th century was carried out under the shadow of the evangelical revival set in motion by Charles Simeon, and associated in Cambridge itself with revived Perpendicular and Tudor styles. Harlton and Haslingfield were among the five churches chosen by the Camden Society for their exemplar of 1845; no drastic alterations resulted. In the western part of the area the little new work done prior to 1850 nowhere rises much above the level of Eltisley chancel which is in a nondescript Gothic style of c. 1840 in white brick and slate. Despite earlier criticisms by the Camden Society, Roman cement continued to be the favoured material to combat decaying clunch dressings after the middle of the century, and was often used with comparative restraint and sympathy, as in the restored S. doorway at Barrington. The chancel at Dry Drayton, rebuilt soon after 1850 in a late 13th-century style, favoured by high churchmen, was evidently the work of the 'squarson' family of Smith. The church at Papworth St. Agnes (Plate 24) was rebuilt about the same time by the Rev. H. J. Sperling, likewise a 'squarson', in a style approximating to 'Decorated'.

Mediaeval roofs survive in less than half the churches in the area. That of the nave at Coton, of trussed-rafter type, can hardly be later than the early 14th century. Similar roofs at Arrington, Croydon and Haslingfield are ceiled and have not been inspected but are likely to be of comparable age. Apparently related to them are the 14th-century roofs over the aisles and the nave at Barrington, the latter coeval with the added clearstorey. The Haslingfield aisle roofs (Plate 95) have unusually elaborate reticulated openwork in the spandrels formed by the arched braces. The five-bay king-post nave roof at Barrington (Plate 43) is of rather low pitch and has openwork spandrels of simpler design than at Haslingfield and looking somewhat later.

Fittings

The thirty-seven churches listed are well supplied with ancient fittings including such diverse items as a mediaeval banner-stave locker at Gamlingay and an 18th-century linen damask, illustrating the siege of Lille in 1708, at Knapwell.

Interest attaches to those fittings which from their materials are likely to be of local origin, but objects such as coffins, floor slabs and funeral monuments made from imported materials are also of note in so far as they are evidence of trade channels. The following comments are designed to supplement the conspectus of fittings provided in the index to this volume:

Bells and Bell frames

In several places in the Inventory the descriptions of bells will be found to differ from those given by Raven (Church Bells of Cambs.). A number of bells have been attributed to foundries or to particular founders, the largest early group being that from Bury St. Edmunds. Of the sixteen pre-Reformation bells, eleven are dedicated to saints and most of them to the Virgin. Lombardic lettering was usual for dedicatory inscriptions before the 15th century, and continued in use afterwards both on its own and in conjunction with black-letter or occasionally with Roman capitals; for example on the 5th bell at Croxton a Roman capital appears in an otherwise Lombardic inscription. By contrast with the mediaeval period, when inscriptions normally carried a dedication and no date, the reverse is true after the Reformation. Very few 16th-century bells are recorded in the area, and possibly the earlier bells survived at the time, but in the 17th century many of the churches acquired a new peal or at least augmentation of a depleted peal. This is apparent at all periods of the 17th century, but particularly in the second and third decades when eleven churches received new bells. Barton obtained a ring of three in 1608 and Graveley of four in 1624. Strangely, more bells were installed during the Commonwealth than in the Laudian period, notably at Gamlingay where four were hung in 1653, three of which survive. Of the 18th-century bells, the three at Hardwick (1797) and a peal of five at Dry Drayton (1746) are the most complete series.

About half the churches in the area contain bell frames of considerable antiquity, but precise dating has not been attempted since it has not been possible to attach a chronological sequence to the variations of design. Two such frames, at Comberton and Gamlingay, are examples of this diversity and are illustrated in the text.

Brasses and Brass indents

By comparison with other parts of the county, West Cambridgeshire has relatively few brasses. The largest is that of a priest at Wimpole (Plate 112) which was originally enhanced with enamel inlays. The number of indents which have been recorded indicates that many more brasses of the 15th and 16th centuries once existed, but 18th-century descriptions show that they had already been removed by that time. The largest collection is at Elsworth, where there are nine indents.

Chests

Conventional methods of dating, based on constructional and decorative features, have been used, but they are of doubtful reliability. The most primitive, a 'dug-out', is at Boxworth. This has been assumed to be mediaeval, as has that at Coton, and there are other early examples at Hardwick and Little Gransden.

Coffin lids

Part of a coffin lid at Orwell, carved with interlace and a Maltese cross, may not be earlier than the 12th century. Other small stone fragments carved with interlace, at Caxton (Plate 4), Conington and Grantchester, may likewise be post-Conquest. The remainder, many fragmentary, for the most part carved or incised with crosses of various designs, are 13th- or 14th-century (L. A. S. Butler: 'Mediaeval Grave Stones of Cambridgeshire, Huntingdonshire and the Soke of Peterborough', C.A.S. Procs. L (1957), 89–100; 'Minor Mediaeval Monumental Sculpture in the East Midlands', Arch. J. CXXI (1964), 111–153). The material is usually limestone, often Barnack. Remains of mediaeval grave stones of clunch at Barrington, mentioned by Butler, have been described in the Inventory as floor slabs, there being no very clear distinction between these two classes of fittings.

Communion tables

Some ten are of the first half of the 17th century, more or less restored, and have turned legs at the corners and shaped brackets to the top rails. These last are sometimes carved with stylised natural forms, jewel ornament or fluting. A more elaborate table, at Bourn, has carved legs, and that at Barton, also 17th-century, has arcading of architectural character. The finely-carved table of c. 1720 at Wimpole (Plate 136) is presumably of London origin.

Doors

Fourteen of these, mostly in towers, have been accepted as mediaeval, or, more cautiously, as 'ancient'; several retain old furniture. Plank construction, like that of the door to the rood stair at Harlton (Plate 8), is common. The number also includes a fine, delicately traceried S. door at Barrington (Plate 81) and an equally fine but now mutilated former W. door at Gamlingay. Both are in two leaves and possibly of the 14th century.

Fonts

The retention of early fonts, and especially their bowls, in churches of later construction, is particularly evident in the area; exceptions are the 12th-century fonts at Coton and Orwell which are contemporary with parts of the fabric. Only the bowls of 12th-century fonts have survived and these are either cylindrical or rectangular, the latter being sometimes carved with geometric designs or rudimentary arcading. The majority of fonts in the area belong to the 13th century, and most retain their original stems and bases, which with their bowls are usually octagonal, the latter being undecorated and slightly tapered, e.g. Comberton (Plate 17). At Barton the base of the font appears to be an inverted bowl; the upper bowl is an earlier one, refashioned in the 13th century, and was possibly reused from the deserted village of Whitwell. The later mediaeval fonts continue the octagonal form, but are generally more slender, and the sides are usually enriched with sculpture of an architectural character. The S. aisle was the favoured position, but the original siting is not always clear. The font at Croxton (Plate 5) was presumably placed against the W. pier of the S. arcade when the 13th-century bowl received a new stem, and that at Haslingfield originally stood in a similar position. The number having later stems may be due to re-siting and to alterations for ritual reasons; the elaboration of the new stems is often in contrast to the severity of the earlier bowls, e.g. Kingston (Plate 5). The mid 19th-century font at Harlton (Plate 92), in the 14th-century style, was introduced as a result of the strictures on the previous 'absurd pagan vase' by the Camden Society (Churches of Cambridgeshire (1845), 93).

Glass

The churches of West Cambridgeshire have lost nearly all their mediaeval glass. Much must have been destroyed by the 18th century, but the notebooks of William Cole show that the last two hundred years have seen further significant losses. The largest surviving quantities are at Wimpole and Haslingfield, both of which have 14th-century glass in contemporary tracery, although now largely reset.

Post-Reformation work includes a made-up window of the late 16th century at Madingley, an armorial display of the Yorkes and their connections at Wimpole, and memorial windows in the 19th-century Gothic revival style at Dry Drayton (Plate 24).

'Low-side' windows

A feature common to a number of churches in the area is the small window rebated for a shutter, appropriately and customarily called a 'low-side', which usually occurs at the W. extremity of the S. wall of the chancel; at Coton it is on the N. and at Gamlingay there are low-sides in both N. and S. walls. The window may be a distinct aperture or be part of a larger, conventional window. The earlier tend to be plain rectangular openings, for example those at Arrington and Coton, which are probably late 13th-century. The great majority are of the 14th century, whether they are simple openings, as at Elsworth, or part of a more elaborate arrangement below a transom, as at Barrington, Comberton (Plate 68) or Kingston. At Harlton the late 14th-century S. window is a homogeneous design of three lights with a low transom, below which are quatrefoil-headed low-sides. Those at Gamlingay (c. 1442–3) were presumably still in use when the late 15th-century stalls were put up; the latter block the windows, but original sliding panels provide access. Such an arrangement perhaps favours the explanation that the low-sides were used to display lights, but the absence of such windows in chancels built in toto at a time when these features were particularly in vogue (e.g. Grantchester and Orwell) remains unexplained.

Monuments and Floor slabs

The survival of Elizabethan and early Stuart memorials made of clunch in Cambridge and the surrounding countryside points to the existence of local schools of monumental masons. Those in the area include a wall monument to Anna Lyng, 1586, at Barrington and the canopied tomb of Edward Leeds, 1589 (Plate 82), at Croxton. Fragments of another canopied tomb at Longstowe are presumed to be from that of Anthony Cage, 1603, and his wife Dorothy, the existing monument being a pastiche. Wall monuments of Fogge Newton at Kingston, 1612, and of Andrew Downes, 1627, at Coton illustrate the modest elegance appropriate at the time to persons of academic standing; another, at Orwell, to Jeremias Radcliffe, 1623, is in a genre represented in Cambridge in St. Botolph's (Thomas Plaifere, 1609–10) and in St. Mary the Great (William Butler, 1617–18) (R.C.H.M., Cambridge, 268, 279, and Plate 13).

The church at Wimpole contains a number of monuments to the Yorke family and its connections, and also one of Sir Thomas and Lady Chicheley, whose son built the mid 17th-century nucleus of the existing house nearby. Pride of place must go to the impressive memorial in the N. chapel of the first earl, 1764, and his countess, 1761 (Plate 127), designed by James Stuart and executed by Peter Scheemakers. These two were also responsible for the smaller but still considerable adjacent monument to Catherine, 1759, wife of the Hon. Charles Yorke, mother of the third earl. A third piece, companion to the foregoing and also by Scheemakers, commemorates the Hon. Charles Yorke who died in 1770. Among other monuments at Wimpole are signed works by Flaxman, Banks, Bacon and the Westmacotts, father and son.

The nave of Conington church, rebuilt as a pantheon in or about 1737, has recesses in the side walls housing monuments of the Cotton family. Among them are those of Robert Cotton, 1697, by Grinling Gibbons, and of his mother Alice, 1657, which incorporate portrait busts (Plate 14). Somewhat later is the wall tablet, with twin portrait medallions in low relief, to the daughters of Dingley Askham who remodelled the church (Plate 90). Smaller groups of monuments at Haslingfield, Longstowe and Madingley include that of Sir Thomas Wendy, 1673 (Plate 83), of Haslingfield Hall and that of Sir Ralph Bovey of Longstowe, 1679 (Plate 138), whose naked demi-figure reaches for an anchor dangling from a cloud. The Fryer monument at Harlton (Frontispiece), an elaborate composition in painted and gilt alabaster, presumably of the third decade of the 17th century, would be scarcely more than an average period piece but for two terminal figures (Plate 89) of unusual quality.

The uncertainty of earthly survival is recorded on a number of monuments to the young. At Madingley, a brief Latin epitaph tells of the birth and death of a nameless innocent on a single day in 1636; at Conington, a monument is shared by the two young Askham sisters who died within a few days of each other in 1748 (Plate 90); and at Graveley, a wall tablet narrates how May Warren's short career of three years and three months began in the East Indies and ended at the Rectory in August 1838, after a series of picturesque vicissitudes (Plate 15).

The terms 'coffin lid' and 'floor slab' or 'ledger' are overlapping. The 13th- or 14th-century floor slab of shelly limestone at Comberton fulfils the same basic function as an 11th- or 12th-century coffin lid, the most important difference being the inscribed epitaph, in this case in Norman French. There are several mediaeval inscribed slabs in the area; one at Tadlow of a fine-textured white limestone has incised effigies and inscription, now much worn, and is not regionally a common type.

Most of the floor slabs recorded are of the 17th to the 19th centuries, the commonest material being the dark grey or black stone sometimes called 'Tournai marble'. There are fine series of these ledgers in the chancels of Caxton (members of the Barnard family) and of Haslingfield (the Wendys and their connections). The earliest example in the area is ostensibly that at Barton to Mathyas Martine, who died in 1613, although the slab may be considerably later. 'Tournai marble' or its equivalent seems to have remained in use until the second quarter of the 19th century. A ledger of this material at Orwell records deaths in 1840 and 1846. Adjacent is another, of 1830, by Gilbert of Cambridge, who also signs a ledger at Elsworth.

Outstanding among the few noteworthy monuments in churchyards are those of the 17th century at Orwell which are coffin-shaped and decorated with skeletal ornament (Plate 15). Most churchyards contain memorials of the 18th and 19th centuries, but these have not been individually described in the Inventory. A group, dating from the early 18th century, at Gamlingay, exhibit a high standard of craftsmanship but lack originality in design.

Niches

Corbels and elaborated brackets are often associated with niches, and when internal usually indicate the former positions of altars or images. Clunch is a favourite material for niches, even outside, and they are often badly worn or mutilated and despoiled of their images. Most are of the later middle ages and octagonal on plan; the brackets are as a rule simply moulded and may be carved with supporting half angels or heads; the niches characteristically have side buttresses rising to miniature canopies, vaulted and arched, with crocketed and spired finials, as at Harlton (Plate 69).

Painting

Two churches, Barton and Kingston (Plate 105), retain substantial areas of mediaeval figurative painting. The subjects include scenes from the New Testament, allegories and mysteries. Fragments of similar subjects occur at Barrington and formerly at Lolworth, and painting in imitation of architectural decoration survives at Gamlingay.

Piscinae and Sedilia

The relatively large and elaborate double piscinae at Arrington and Caxton (Plate 6) are early, and the former is comparable to one of the first half of the 13th century at Jesus College (R.C.H.M., Cambridge, Plate 27). Later examples, such as those at Barrington and Gamlingay (Plate 7), are little more than decorated niches. Uncanopied piscinae in window sills, as at Barton and Comberton, where there are respectively two and three sinkings, are difficult to date owing to resetting and re-use within the window embrasure; ritualistic purposes may account for these alterations.

Sedilia, too, are commonly simple seats on low window sills, but more elaborate triple seats occur, as at Bourn (Plate 6) and Gamlingay, and these are often contrived with little regard for a relationship with the S. windows of the chancel. At Elsworth (Plate 6) the early 14th-century double piscina and sedilia are combined in a single architectural composition of high quality.

Plate

No pre-Reformation plate has been found in the area, but cups resulting from Archbishop Parker's liturgical reforms survive in a number of parishes. Nine of these cups, seven of which have cover patens, are unassayed but marked with the flat fish of Thomas Buttell, who was working in the diocese of Norwich in 1567–8 and Peterborough in 1570. The bowls are of a simple cylindrical form and are inscribed in capitals around the centre (Plate 23). The matching patens are all dated '1569'. Late pieces of interest include a set of Laudian revival plate at Wimpole by the 'hound sejant' goldsmith, c. 1655, and a finely engraved communion set at Hatley St. George, presented by Margaret Trefusis in 1723.

Pulpits

A fairly complete but restored mediaeval pulpit survives at Elsworth (Plate 17), and those at Barrington, Boxworth and Haslingfield incorporate similar work. They are wooden and have central supporting posts. Of the 17th-century pulpits, that at Barton (Plate 54), dated 1635, is the most complete.

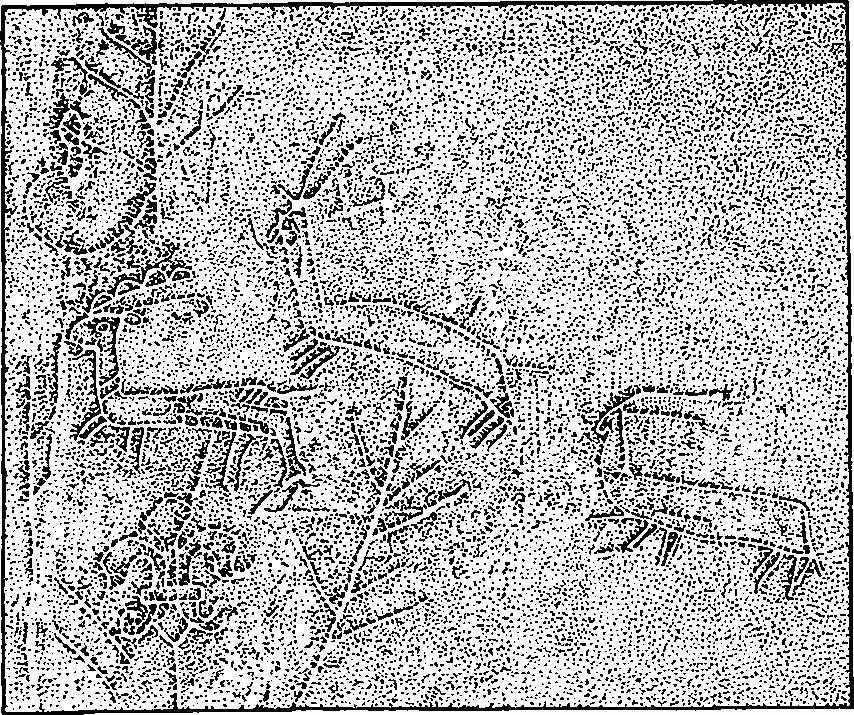

Scratchings

The fine texture of the clunch used for church interiors has acted as an enticement to doodlers and scribes of all kinds from mediaeval to modern times. The resultant graffiti take the form of both drawings and inscriptions. The drawings, which include human figures, animal subjects, windmills, houses, shields and heraldic devices, are by nature of uncertain date and have not always been listed in the Inventory. Inscriptions, apart from names, tend to be phrases alluding to the brevity of life or to local events like storms or epidemics; there are also sacred monograms, guidance for change-ringing, scraps of plain chant and possibly names of masons. A neatly written notice on a pier at Gamlingay (Plate 16) illustrates the tendency in the later middle ages to claim rights to a specific place in church, an added interest being that the claimant is known from other evidence to have been the wife of a local personality who was a benefactor. Among a large number of scratchings at Harlton are several having votive inferences. Scratchings are also to be found in secular buildings, though less frequently.

Screens

Wood was the usual material, but an interesting exception is the late 14th-century stone screen, originally adorned with sculpture, at Harlton (Plate 93), and others have been inferred at Eltisley and Madingley. Most were designed to separate chancel from nave, and there is evidence that some at least were originally associated with a wooden tympanum to take a painted iconographical scheme for which there was no space above the high chancel arch, e.g. Harlton and Gamlingay. The commonest position for the stair to the rood loft was in the N.E. angle of the nave, and judging from the date of their doorways, the screens were in general insertions of the second half of the 14th century or later. The stone screen conjectured at Eltisley would have been an exception of the 13th century or earlier. As well as chancel screens, there were evidently others, like those of the 15th century at Croxton (Plate 75) which enclose the eastern parts of the aisles and are apparently coeval with the seating.

The dating of screens, as of mediaeval woodwork generally, presents difficulties, and therefore special interest attaches to the screen at Barton (Plate 55), which on heraldic evidence has been assigned to the episcopacy of Bishop Thomas Arundel of Ely (1377–88). If this dating is correct, the Barton screen is a point of reference for similar works in the district, for example at Little Gransden, where the screen, heavily restored and repainted, bears a general resemblance to that at Barton, though with window forms ostensibly somewhat earlier in character.

Seating

Mediaeval seating for the laity in the body of the church is a notable feature in a number of places, but none is earlier than the 15th century. A few benches of simple design, with shaped ends rising to poppy heads, are to be found at Elsworth and Orwell; otherwise the pews are of a characteristic pattern with the fronts, backs and ends divided by applied buttresses into panels which are enriched with an applied tracery and carving at the head, as at Barrington and Croxton. Almost identical with these is the seating at Comberton (Plate 17) and Bourn, but the buttresses and tracery are more elaborate; the Comberton pewing also includes some carved finials (Plate 18).

Stalls

The remains of stalls at Harlton, principally desks, of solid and distinctly rustic construction, and two simple ranges at Orwell, were probably introduced soon after the construction of the chancels, respectively in the late 14th century and c. 1400. A developed form may be seen in the return stalls at Gamlingay (Plate 19) which have carved haunches and misericords. They have been ascribed to c. 1442, when the chancel was apparently remodelled; the side stalls (Plate 18) are later 15th-century. The stalls at Elsworth (Plate 19), which incorporate cupboards below the desks, include a quantity of linenfold panelling, which could be as late as the time of the Dissolution.

Stoups

Two of the earlier stoups, respectively of c. 1300 and the 14th century, at Barton and Haslingfield, are just inside and immediately to the E. of the S. door. When external, as was usual in later examples, they were placed on the W. of the N. door or the E. of the S. door, and mostly in porches; that at Gamlingay is on the S. of the W. door. The most usual form is a shallow bowl projecting from a recess, which is sometimes canopied. The Barrington stoup was exceptionally large and elaborate before its mutilation.

Secular

It is unlikely that any dwellings of the labouring classes remain in West Cambridgeshire which are of earlier date than the 18th century, and except in a few contexts the word 'cottage' has been avoided in the descriptions of secular monuments. The surviving houses of early date, although sometimes now in 'cot tage' occupation, were originally built for people of some substance in the rural community. The two or three generations after c. 1620 saw something like a 'general rebuilding' or housing revolution in this, as perhaps in some adjoining areas; the process may be thought of as extending gradually to those lower in the scale, so that by the middle of the 18th century, houses were being built according to types evolved in the course of this revolution for all but the very poorest. Although there is no standing structure in the area to show how these humbler inhabitants had been housed previously, evidence may be forthcoming from the excavation of abandoned house sites in deserted or diminished villages.

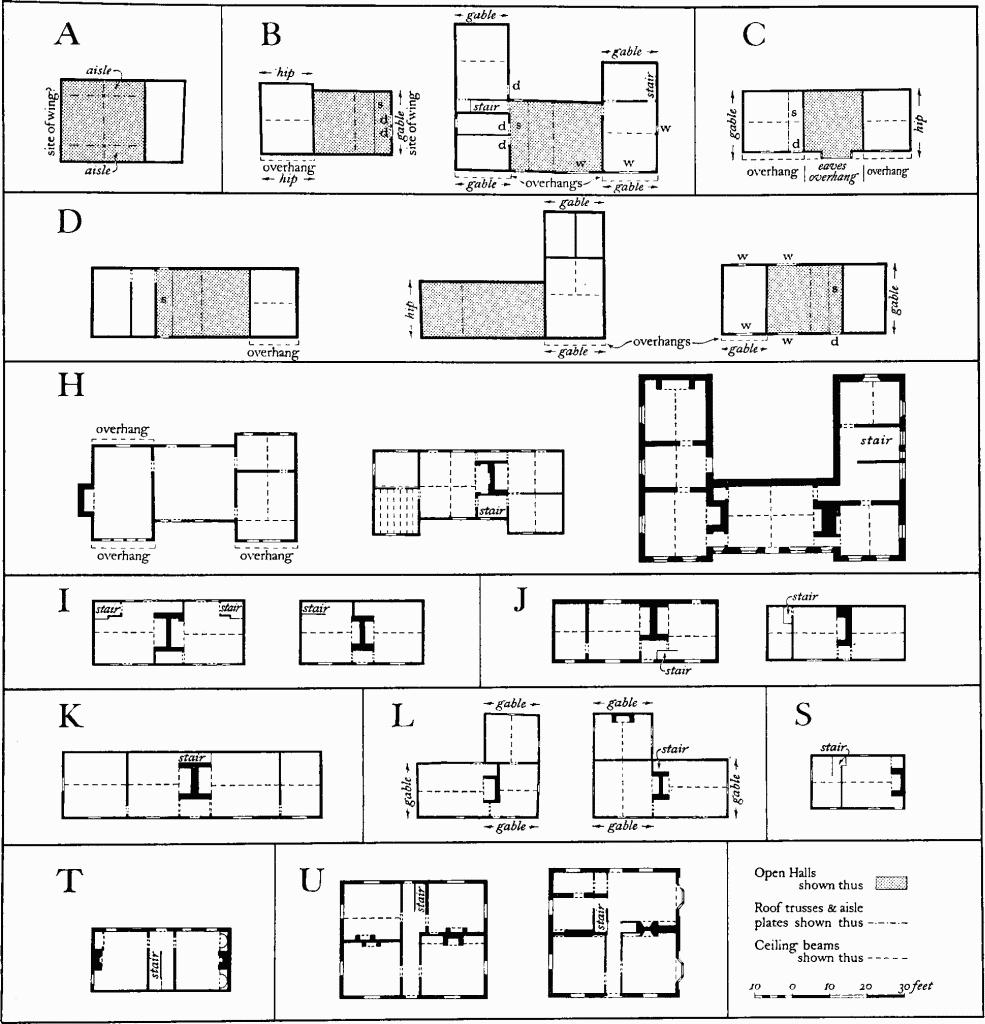

The great variety of house-types in West Cambridgeshire is notable and lends itself fairly readily to a classification based on plan-form. It comprises twelve classes, of which A, B, C and D are mediaeval, or are in the mediaeval tradition, and are characterized by the existence of a hall open to the roof. Class H first appears in the 16th century and classes I, J, K and L in the 17th century; these are separated from the earlier group (classes A to D) by a transitional period of house-construction for which no practical system of classification has emerged. Houses in classes H to L are normally distinguished by having an internal chimney. These are followed by classes S, T, and U, which are mostly of the 18th and 19th centuries, although the earlier classes continued to be built in this period.

The accompanying diagram, which illustrates these classes of houses, is based on examples listed in this Inventory, although it should not be taken that the plans necessarily record the buildings in their present state. The classes may be briefly described as follows :—

Class A: having an open hall with aisles.

Class B : having an open hall, and cross wings usually of two storeys.

Class C: having an open hall with end bays of two storeys, all roofed as a unit, i.e. a 'Wealden' house.

Class D : having an open hall, extended by a bay at one end and with a cross wing at the other, the latter usually of two storeys.

Class H: having a central range, cross wings and usually an upper floor throughout.

Class I: having two ground floor rooms and an internal chimney.

Class J: as class I, but with three rooms in line.

Class K: as class I, but with four rooms in line.

Class L: as class I, with an additional room placed behind one of the others.

Class S: having two ground-floor rooms and one end chimney.

Class T: having a central entrance and chimneys at either end of the range.

Class U: having an approximately square plan, with rooms arranged in double depth.

(Houses in classes H to U are usually of two storeys. Missing letters in the alphabetical sequence allow for an extension of the classification. The end bay adjacent to the screens passage has normally been described as the 'service' end or wing.)

Remains of three aisled halls survive; two (Bourn (8) and Kingston (3)) are probably late 13th-century, and one (Barrington (17)) is 14th-century. All three houses have been assigned to class A because of this structural similarity, although they may originally have had little else in common. Barrington (17) retains much of a service end, coeval with the hall, and apparently roofed in continuation of it. In the other, earlier, examples there is no evidence of the lay-out at the ends of the hall. No trace has been found in the area of any aisled dwelling later than these three, but a small and possibly late example survives at Ickleton in S. Cambridgeshire; another at Fulbourn, some miles to the E. of Cambridge, was demolished a few years ago. However, the tradition of aisled timber-construction continued to be used in barns at least as late as the 17th century, e.g. Gamlingay (4) (Plate 27).

Classification of Houses

The diagrams illustrating types of houses are based upon existing houses in the area covered by this Inventory, but they are schematic in so far as later additions have been omitted. In Classes A to D, door and window openings which are known to be coeval with the building are indicated by 'd' and 'w' respectively, and the position of screens passages, whether existing or inferred, by 's'. In the walls shown without openings, the original features are not traceable.

The following houses have been used as the basis for the diagrams; those marked with an asterisk are shown with later additions in plans in the Inventory:—

Class: A, Barrington (17)*; B, Comberton (2)*, Croxton (6)*; C, Barrington (20); D, Eltisley (5), Haslingfield (6)*, Eltisley (9)*; H, Gamlingay (4), Great Eversden (16), Elsworth (3)*; I, Gamlingay (38), Bourn (11); J, Gamlingay (40), Elsworth (20); K, Elsworth (4); L, Elsworth (21)*, Toft (12); S, Barrington (26); T, Barrington (5); U, Little Eversden (4), Barrington (24).

The class-B houses, of which there are at least eight, are mostly of the 15th or 16th century and are somewhat smaller than the 14th-century prototypes existing elsewhere. The front elevation of these houses, having gabled cross wings often with first floor overhangs or jetties, and a ridge line of differing levels, produces a characteristic appearance. The Manor House, Croxton (6) (Plate 18), may be taken as typical of the class in this area. Its open hall of two bays has a cambered tie beam with arch braces, and the tall side window originally rose as far as the wall plate, being divided horizontally by the middle rail. Within the hall, the screens passage had twin doors to the butteries and an opening to the stair. The service wing projected to the rear to accommodate the kitchen, which contained an external door adjacent to that into the screens passage. Above this wing were rooms of some pretension. The solar wing had two rooms on each floor and a stair.

Class C is the house type, often described as 'Wealden', in which the ground plan, though often with other proportions and scale, is similar to that of the class-B house, the difference being in a unified roof structure which covers the wings as well as the hall; the wings are jettied, as in class B, and thus the eaves of the hall are correspondingly deep. Such houses, though most frequent in S.E. England, have a wide distribution. Only one (Barrington (20); Plate 36) is here recorded. Grantchester (2) and Barton (9) are interesting late mediaeval houses which approximate to class-C design in lay-out and unified structure, but which were not jettied along the fronts.

A number of houses occur in the area which have an open hall and only one cross wing, and these have been grouped as class D. It appears that there are at least two distinct varieties within the class. One of these, of which Eltisley (9) is an example, has a second room at the far end of the hall from the cross wing, roofed with the hall and, like it, open; the function of this adjunct is not clear. The other variety, best represented in this Inventory by Haslingfield (6), consists merely of a hall and one cross wing but the hall is rather longer than normal. At least one such structure, in the village of Fen Drayton, just outside the area, is an inn, 'The Three Tuns'; others, for one reason or another, also appear to have been inns. The typological variety which has emerged suggests that a wider choice of material might make a sub-division of class D necessary.

The open-hall group of houses is superseded by those buildings which have a simple rectangular plan, two storeys, and one or both long sides jettied. The modification of the design of the class-B house by the introduction of a jettied first floor in the hall range produces a distinctive elevation best seen in the nearby Ouse valley, as at Godmanchester (R.C.H.M., Hunts., Plates 68, 69); examples occur locally at University Farm, Barton (2) (Plate 47), and at the Rectory, Wimpole (3), which was built in 1597 but later substantially altered.