Petitions to the House of Lords, 1597-1696.

This free content was born digital. CC-NC-BY.

'Introduction', in Petitions to the House of Lords, 1597-1696, ed. Jason Peacey , British History Online https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/petitions/house-of-lords/introduction [accessed 26 April 2025].

'Introduction', in Petitions to the House of Lords, 1597-1696. Edited by Jason Peacey , British History Online, accessed April 26, 2025, https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/petitions/house-of-lords/introduction.

"Introduction". Petitions to the House of Lords, 1597-1696. Ed. Jason Peacey , British History Online. Web. 26 April 2025. https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/petitions/house-of-lords/introduction.

In this section

Introduction

Seventeenth-century petitioners had many avenues for pursuing redress, and at the highest level this included the House of Lords, an institution whose role in handling people's grievances was transformed during the seventeenth century. This partly reflected Parliament's growing importance within the constitution, the increased frequency with which it met, and the longevity of parliamentary sessions. However, it also reflected a conscious decision to revive the House's judicial functions. This occurred in 1621, and it enabled the Lords to instigate impeachment proceedings against prominent officials, a power that had fallen into disuse in the fifteenth century. It also reflected widespread concern regarding the law courts. Preceding decades had witnessed a dramatic growth in civil litigation, and complaints were frequently made that the courts were overloaded, that legal processes had become slow and expensive, and that judges failed to deliver decisive verdicts. The upshot was that the Lords rapidly became a vital forum for petitioners, and this volume includes transcriptions of a sample of 732 petitions submitted between 1597 and 1696.

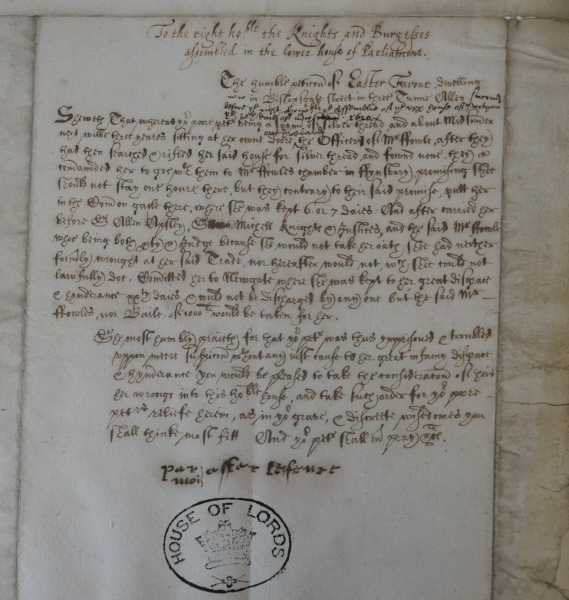

As many petitions indicate, the decisions taken in 1621 ensured that Parliament came to be seen as a 'refuge' for aggrieved people, and a place to which they could 'fly' when other attempts to solve problems were ineffective, and when other options became impossible. This means that the people who submitted their pleas and appeals to the Lords hailed from all sections of contemporary society. It is obviously true that many supplicants were members of the social and political elite (gentlemen, knights and baronets), and indeed from the nobility, and petitions were occasionally submitted by men who insisted upon their membership of, and status within, the upper House. However, petitions also came from humble people, and indeed poor individuals, like the impoverished spinner, Easter Favour, from Three Tuns Alley in Bishopsgate Street, London (1621). Favour also highlights the prominence of women petitioners, who feature in 152 petitions (21%). Indeed, while many women appear within the sample alongside their husbands (or brothers), many more acted alone, or indeed with other women. Many of these came from privileged backgrounds, but many certainly did not.

A petition from Easter Favour of Three Tuns Alley in Bishopsgate Street, London, seeking relief from unfair imprisonment, 1621. Courtesy of the Parliamentary Archives (HL/PO/JO/10/1/16).

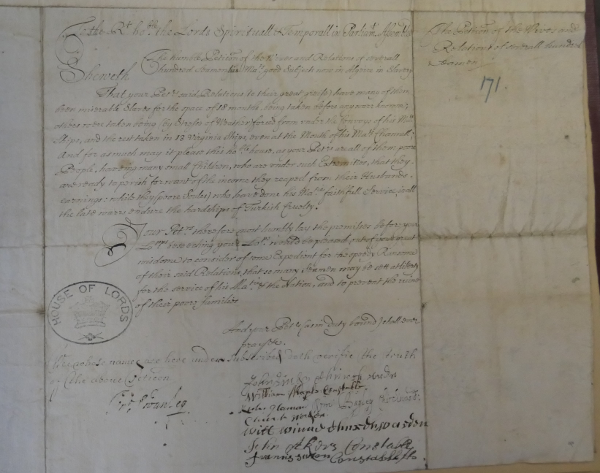

These female petitioners also highlight another important facet of parliamentary petitions: the growing importance of collective petitions. Many women joined small clusters of supplicants, such as creditors, but others joined more substantial groups, as tenants, parishioners and officers' widows, and as shopkeepers, cardmakers, wire-drawers and silk dyers. These petitions thus reveal the diversity of women's lives in the seventeenth century. More generally, while the vast majority of petitions came from individuals, a sizeable minority — 193 or 26% — came from groups of people who do not appear to have been related by blood or marriage. The bulk of these involved fairly large groups, including the parishioners and 'inhabitants' of individual towns and villages, and the tenants of great estates, as well as members of institutions and companies both great and small, and practitioners of particular trades and professions. Some came together as a result of shared experiences, including those who complained about the loss of common land, and the sufferings that resulted from military service, or who endured capture and enslavement by Algerian pirates. Some of these only involved a few named spokesmen, but others contained long lists of signatories, and this sample suggests that the submission of subscribed petitions became more common over time. As such, this sample bears witness to the development of mass petitioning.

A petition from the wives and relations of several hundred seamen 'now in Algeire in slavery', asking for ransom to be paid, 1679. Courtesy of the Parliamentary Archives (HL/PO/JO/10/1/388/171).

Diversity was also evident in the issues that supplicants raised. Given their audience, some petitions obviously related to the affairs of church and state, the controversies of the age, and notorious individuals. They thus shed light upon responses to the 'Bishops' Wars' (1639-40), the Irish Rebellion (1641) and English revolution (1642-51), not least the fates of soldiers and regicides, as well as upon the fallout from the Popish Plot (1678-9), the Rye House Plot (1683), and Jacobite plotting against William III. Some were submitted by leading statesmen, such as the Earl of Strafford (impeached 1640) and the Earl of Danby (impeached 1678), while another came from Titus Oates, the inventor of the Popish Plot scare. A few more came from the House of Commons, and from the commissioners who negotiated with the Scottish covenanters. A great many relate to religious affairs and church politics, including underground conventicles and radical sectarians like Quakers and Baptists, some of whom appealed for toleration. Many more involved recusants and Catholic priests, as well as local disputes over church lands and church repairs, all of which addressed topical controversies, as did grievances regarding royal policies, from the expansion of royal forests to the imposition of Ship Money, as well as officially-backed schemes like the drainage of the Fens. The latter involved notorious episodes of rioting, highlighting the entanglement of local and national politics, as well as the transformation of popular agitation. Beyond this, a small number of petitions related to parliamentary matters, from elections and the franchise to the work of clerks and doorkeepers.

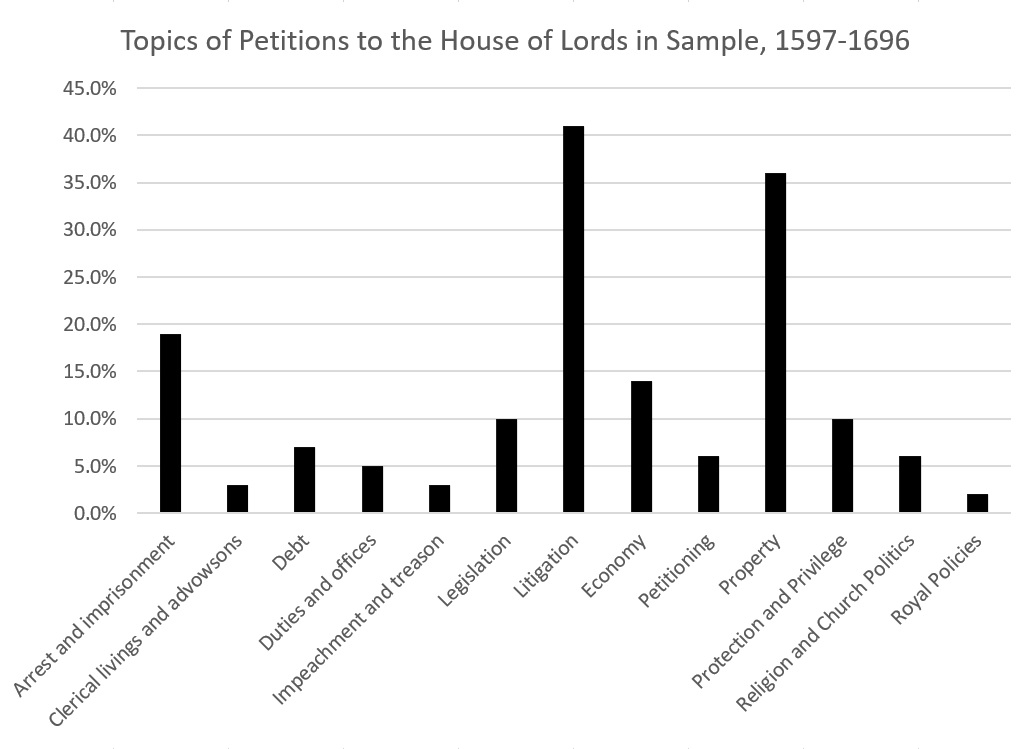

Key themes addressed by petitions in the Parliamentary Archives sample

Much more striking are the everyday troubles — and tales of woe — to which petitioners drew attention. Some of these involved straightforward complaints about assaults, slanderous words and marital problems, or about bizarre episodes like the desecration of Archbishop Matthew Parker's tomb (15 July 1661 and 9 December 1661). Some involved fairly simple requests, for relief, financial assistance and preferment, as well as for clemency and mercy. Generally, however, they were much more complex, setting out substantive grievances at the same time as reflecting upon political and legal processes, and imploring peers to investigate and arbitrate, make interventions and issue rulings. Many petitioners insisted that their own problems revealed matters of wider public concern, and 'the generall case of all the free people of England' (Arnold Brames, 1648). A significant — and increasingly prominent — body of petitions related to economic affairs, both domestic and overseas, in terms of vital trades like fishing, tobacco and clothing. Often, these raised wider issues, such as river navigation, customs and the role of livery companies, as well as the behaviour of trading companies and the vexed issue of customs, patents and monopolies, all of which fed into wider political debates.

This complexity is such that, amid all of the diverse issues that were raised, the majority of petitioners also addressed one or more of three key themes.

1. Legislation. One in ten petitioners addressed specific legislative initiatives, as individuals and interest group vied to intervene in parliamentary processes, something that became much more common over time.

2. Property and property rights. Over a third of petitioners highlighted property claims, most commonly in relation to personal interests and private estates, including trusts, legacies and alimony. Some of these involved lands that suffered depredation a result of the civil wars, that were seized by Parliament during the revolution, and that were claimed by the crown after 1660. Occasional reference was also made to charitable foundations and concealed lands.

3. Civil litigation. This was the largest single issue addressed by supplicants, in over 40% of petitions, something that reflected peers' decision to revive the judicial function of the House of Lords. Here, the issues were numerous, although they generally involved pleas for legal assistance of some kind. Appeals were made against judgments in inferior courts, and complaints emerged about how those institutions functioned, as well as about the conduct of litigants and officials. References were made to forgery and fraud, bribery and corruption, involving ordinary suitors as well as prominent lawyers, such as the Lord Chancellor, Francis Bacon, and judges like Sir Lawrence Tanfield. Many petitioners appealed to the Lords as impoverished litigants overborne by powerful 'oppressors', who felt unable to pursue litigation through the courts. For them, Parliament represented the last hope for a legal solution, and an institution from which they expected assistance; 'a place of super intendent power and authority where all the greevances of his majesties subjectes deprived of releefe elsewhere doe receive honourable examinacion and reformacion to the great comfort of the common wealth' (Mary Lough, 1624). However, to the extent that peers instigated judicial hearings, petitions also related to the workings of the Lords, as attempts were made to speed up or slow down proceedings within the upper House.

Moreover, in raising grievances and promoting personal and sectional interests — sometimes trading blows in rival petitions — supplicants also addressed their experiences of disputation. In part, this involved petitioning itself, as attempts were made to keep cases alive, particularly when the dissolution of Parliament brought proceedings to an end. Many people petitioned the Lords repeatedly, resubmitting old texts alongside new ones, and reflecting on both their experiences and their treatment, however politely. Beyond this, petitioners regularly complained about being arrested or imprisoned, often at the hands of creditors, opponents and enemies, pleading for relief and release (and for habeas corpus), and even raising general concerns about the prison system itself. Finally, petitioners repeatedly raised issues about 'privilege', invoking the 'protection' that they claimed as peers, or as the servants of peers, MPs and royal officials, or else asking for such privilege to be waived in order to make litigation possible.

Archival Context

All of these documents are held at the Parliamentary Archives, London, within the 'Main Papers' of the House of Lords. This material was famously saved from the fire that destroyed the old Palace of Westminster in 1834, during which the bulk of the records of the House of Commons were lost. That said, a few of these petitions were addressed to the Commons, to specific committees, and to the king, and doubtless survive because they eventually reached the attention of peers. It seems likely that the surviving body of parliamentary petitions represents only a proportion of those originally submitted. Evidence from other records — including fragmentary registers of petitions — indicates that some documents have been lost, while others were returned to those by whom they were composed. Indeed, one fascinating issue highlighted by this volume involves the responses that petitioners received, as recorded in annotations by clerical officials. These sometimes indicate the date on which petitions were read, as well as the decisions that were taken, not least when supplications were 'rejected', when appeals were 'dismissed', and when nothing was done.

This sample was created by transcribing every extant petition from a range of years across the century, up to a maximum of 80 items for exceptionally voluminous years: 1597 (1), 1601 (1), 1606 (1), 1610 (4), 1614 (2), 1620 (4), 1621 (65), 1624 (78), 1640 (80), 1648 (80), 1661 (104), 1671 (71), 1679 (88), 1689 (80), 1696 (73). Some of these were certainly unusual years, following the 'personal rule', the Restoration, and the Glorious Revolution. Nevertheless, this selection was made with the intention of producing as even a survey as possible, given that Parliament did not meet every year, and that the House of Lords did not exist between 1649 and 1660. The sampling certainly demonstrates the growing importance of Parliament as a forum for petitioners.

Acknowledgements

The cost of archival photography, transcription and editorial work was funded by an Arts and Humanities Research Council Research Grant: 'The Power of Petitioning in Seventeenth-Century England' (AH/S001654/1).

The petitions were photographed and sorted by Sharon Howard. They have been transcribed by Tim Wales and Gavin Robinson. All images and transcriptions have been published courtesy of the Parliamentary Archives. We highly encourage readers to take advantage of their extensive collections to pursue further research on the individuals and communities mentioned in the petitions.

Further Reading

For analysis of parliamentary petitions in this period, see James S. Hart, Justice Upon Petition: The House of Lords and the Reformation of Justice (1991); Chris R. Kyle, Theater of State. Parliament and Political Culture in Early Stuart England (2012), chapters 5-6; Jason Peacey, Print and Public Politics in the English Revolution (2013), chapters 8-10; Derek Hirst, 'Making Contact: Petitions and the English Republic', Journal of British Studies, 45:1 (2006), pp. 26-50; Mark Knights, 'Participation and representation before democracy: petitions and addresses in pre-modern Britain', in Ian Shapiro, Susan Stokes, Elizabeth Jean Wood and Alexander Kirschner, eds, Political Representation (2010), pp. 35-58; Mark Knights, 'London petitions and parliamentary politics in 1679', Parliamentary History, 12 (1993); Judith Maltby, 'Petitions for episcopacy and the book of common prayer on the eve of the civil war 1641-1642', in Stephen Taylor, ed., From Cranmer to Davidson: A Church of England Miscellany (Church of England Record Society, 7, 1999); Mark Knights, 'The lowest degree of freedom: the right to petition Parliament, 1640-1800', in. Richard Huzzey, ed., Pressure and Parliament from Civil War to Civil Society (2018); Peter Lake, 'Puritans, Popularity and Petitions: Local Politics in National Context, Cheshire, 1641', in Thomas Cogswell, Richard Cust and Peter Lake, eds, Politics, religion and popularity in early Stuart Britain: essays in honour of Conrad Russell (2002), pp. 259-289; Philip Loft, 'Involving the public: Parliament, petitioning, and the language of interest, 1688-1720', Journal of British Studies, 55:1 (2016), pp. 1-23; Philip Loft, 'Petitioning and Petitioners to the Westminster Parliament, 1660-1788', Parliamentary History, 38:3 (2019); Stewart Beale, 'War widows and revenge in Restoration England', The Seventeenth Century, 33:2 (2018), pp. 195-217; Karin Bowie and Thomas Munck, eds, 'Early modern political petitioning and public engagement in Scotland, Britain and Scandinavia, c.1550-1795', special issue of Parliaments, Estates and Representation, 38:3 (2018); Ellen A. McArthur, 'Women Petitioners and the Long Parliament', English Historical Review, 24:96 (1909); Mihoko Suzuki, Subordinate Subjects: Gender, the Political Nation, and Literary Form in England, 1588-1688 (2003); Brodie Waddell, God, Duty and Community in English Economic Life, 1660-1720 (2012); Hannah Worthen, 'Supplicants and guardians: the petitions of royalist widows during the Civil Wars and Interregnum, 1642-1660', Women's History Review, 26:4 (2016), pp. 528-40.

Transcriptions and Editorial Conventions

The transcriptions generally retain the original spelling and punctuation, with a few exceptions as noted below. In addition to the main text of each petition, subscriptions — whether signatures, initials or marks — have been identified using italics. Paratext added in separate hand — usually endorsements by the magistrates — has been signalled by indentation. However, due to the limits of the format of this edition, we encourage any readers interested in the details of layout, subscriptions or paratext to consult the original manuscripts or request reproductions from the archives.

The following changes have been made during transcription: capitalisation has been modernised, obsolete letterforms (e.g. y/th, u/v, i/j, ff/F) have been modernised, obsolete punctuation (e.g. './.') has been modernised), superscript has been transcribed as regular script, common abbreviations (e.g. 'petr' = 'petitioner') have been silently expanded, and interlined words in the same hand have been silently inserted into the main text.