A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 18. Originally published by Boydell & Brewer for the Institute of Historical Research, Woodbridge, Suffolk, 2016.

This free content was digitised by double rekeying. All rights reserved.

'Warpsgrove', in A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 18, ed. Simon Townley (Woodbridge, Suffolk, 2016), British History Online https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/vch/oxon/vol18/pp422-432 [accessed 31 January 2025].

'Warpsgrove', in A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 18. Edited by Simon Townley (Woodbridge, Suffolk, 2016), British History Online, accessed January 31, 2025, https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/vch/oxon/vol18/pp422-432.

"Warpsgrove". A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 18. Ed. Simon Townley (Woodbridge, Suffolk, 2016), British History Online. Web. 31 January 2025. https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/vch/oxon/vol18/pp422-432.

In this section

WARPSGROVE

Until its unification with Chalgrove in 1932, the tiny parish of Warpsgrove comprised only 335 acres. (fn. 1) In the 13th and early 14th centuries it included a relatively prosperous village of around a dozen houses, but population declined after the Black Death, and by 1453 it was reportedly deserted. The abandoned church had disappeared by the late 18th century, when the settlement comprised three recently established farmhouses and a similar number of labourers' cottages. Two farmhouses and a cottage remained in 2013.

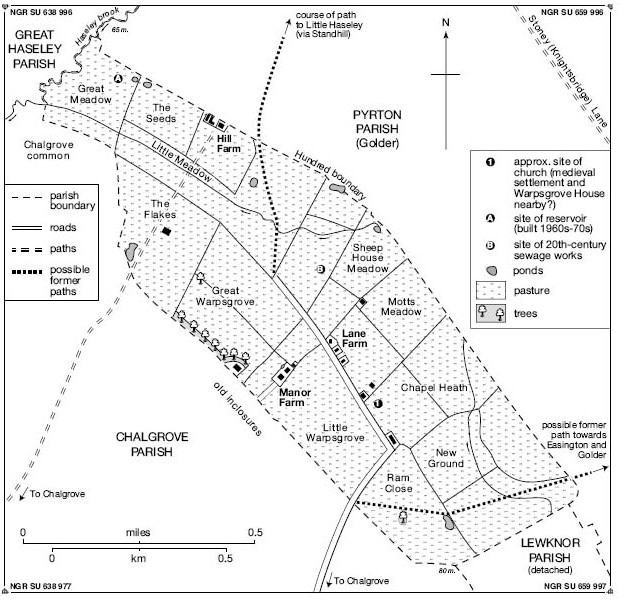

Warpsgrove parish in 1849.

PARISH BOUNDARIES AND LANDSCAPE

Warpsgrove formed a separate manor by 1086, its boundaries partly defined by those of neighbouring estates. (fn. 2) The short northern boundary with Haseley (along Haseley brook) was established by 1002, (fn. 3) while the longer and straighter eastern boundary with Pyrton (to which Warpsgrove may formerly have belonged) followed that of the hundred. (fn. 4) Some stretches there remained uncertain in the early 13th century, when the vicar of Pyrton protested at loss of territory during a perambulation of the boundary near Standhill. (fn. 5) The southern boundary abutted a detached portion of Lewknor, in which Warpsgrove's inhabitants enjoyed rights of common pasture until 1235, (fn. 6) while the western boundary was probably defined by the creation of Chalgrove manor before 1066, Warpsgrove's north-western end there narrowing so as to exclude Chalgrove common. (fn. 7) The boundaries remained unchanged until Warpsgrove's incorporation into Chalgrove. (fn. 8)

The parish lay on Gault Clay, falling gently north-westwards from c.75 m. on the Easington boundary to 65 m. at Haseley brook. (fn. 9) The heavy clay soils provided rich grazing grounds for beef and dairy cattle, and in the mid 19th century the parish's small inclosed fields (with a median size of 13 a.) were all under grass. (fn. 10) Small hedged fields remained a feature in the early 21st century, interspersed with several small woodland plantations; earlier, trees were restricted to hedgerows and orchards. (fn. 11) A 20th-century sewage treatment plant north of the remaining houses served the Second World War airfield at Chalgrove, (fn. 12) and in the 1960s–70s a small reservoir was constructed next to Haseley brook. (fn. 13)

COMMUNICATIONS

The village developed along a road from Chalgrove to Little Haseley, probably that mentioned c.1225 along with roads to Easington and Standhill. (fn. 14) The road was still clearly marked on 18th and early 19th-century maps, (fn. 15) and though the section through Pyrton parish was apparently disused by the late 19th century, and the stretch beyond Warpsgrove sewage plant by 1960, by the early 21st century its whole length was reinstated as a footpath, the section to Warpsgrove's houses being roughly surfaced for vehicles. (fn. 16) A separate path from Warpsgrove joined the Easington–Golder road near Round Hill in 1767, but was later replaced by a less direct route further west. (fn. 17) No direct route to Upper Standhill or Stoney Lane is known, and a path towards Lower Standhill from Chalgrove (crossing Warpsgrove's northern part) was lost when Chalgrove airfield was built in 1943. (fn. 18)

The parish had no carriers, inhabitants relying presumably on those based in Chalgrove. Post was delivered from Tetsworth and later from Wallingford during the 19th century, except in the 1890s when letters were collected from Chalgrove post office. A morning delivery from Chalgrove resumed by the end of the century. (fn. 19)

POPULATION

In 1086 Warpsgrove had six tenant households headed by one villanus, four bordars, and one servus or slave. (fn. 20) Numbers doubled by 1279, when two villeins, nine cottars, and a free tenant were recorded, implying a total population of perhaps 50–60. (fn. 21) The rector may have also resided, (fn. 22) and seven inhabitants paid tax in the early 14th century, suggesting a small but relatively prosperous community. (fn. 23) The Black Death almost certainly initiated population decline: in 1377 poll tax was paid by only 12 inhabitants aged over 14, (fn. 24) and by 1453 the parish was reportedly deserted. (fn. 25)

Thereafter Warpsgrove was omitted from taxation lists. A shepherd lived there in the early 17th century, (fn. 26) but no other permanent residents are known until the early 18th, when a few families were mentioned in Chalgrove's parish registers. (fn. 27) Three resident farmers petitioned the bishop in 1750, their recently established farmhouses remaining probably the only dwellings c.1780. (fn. 28) Thereafter farm workers increased the population to 25 (in 6 houses) by 1801, and numbers fluctuated between 19 and 36 (in 3–6 houses) for the rest of the 19th century. Population peaked in 1911 at 37 people, falling to 16 (in 4 houses) by 1931, the last year in which separate figures were given. (fn. 29)

SETTLEMENT

Finds of pottery, animal bone, ditches, pits, and coins in the south of the parish suggest Iron-Age and Roman occupation characteristic of local rural sites. (fn. 30) The Anglo-Saxon place name means 'the grove by the bridle-path': (fn. 31) 'grove' (OE grāf) may have denoted an area of coppiced woodland, suggesting specialist wood production in a largely arable area. (fn. 32) The bridle-path was possibly Stoney or Knightsbridge Lane, a long-standing route from Oxford to Henley-on-Thames which passes through neighbouring Pyrton parish. (fn. 33) The settlement may have begun as an outlier of a larger estate, supplying coppice poles for fuel, though by 1086 it was an independent manor with no recorded woodland. (fn. 34)

The church (established probably in the 12th century) stood alongside the main road, and the medieval village most likely developed nearby, close to a minor tributary of Haseley brook. (fn. 35) Tenants' houses in the 1250s lay close together, suggesting a nucleated settlement. (fn. 36) In the 15th century both church and village seem to have been largely abandoned, (fn. 37) although in 1519 the manor's lessee received timber for repairs, and the manor house (probably on a site close to the deserted church and village) apparently survived in 1612. (fn. 38) New farmhouses were built in the early 18th century, (fn. 39) and by the mid 18th a small cluster of buildings stood at the main road's junction with the path to Easington, with two isolated dwellings further north. (fn. 40) Settlement remained similar in the mid 19th century, when Lane Farm and three cottages lay by the road near the former church site, with Manor and Hill Farms set amidst the inclosed fields. (fn. 41) Two of Manor farm's cottages were later rebuilt, (fn. 42) but only four houses were occupied in 1931, (fn. 43) and two were removed for the Second World War airfield at Chalgrove. (fn. 44) Nissen huts and other temporary airfield buildings briefly extended into the parish (Fig. 120), (fn. 45) their clearance leaving only Manor House Farm, Lane Farm, and a nearby cottage in 2013.

MANOR

In 1086 Warpsgrove was held by William I's half brother Odo of Bayeux, whose tenant was probably Hervey de Campeaux. (fn. 46) Following Odo's forfeiture the manor was added to the honor of Pontefract (Yorks.), which was held by the Lacy family until 1311. (fn. 47) In 1398 and 1425 the overlordship belonged to the earl of March, and passed later to the Crown. (fn. 48)

The tenancy of Warpsgrove descended (with Little Haseley) to Hervey's Yorkshire successors the Skelbrookes, (fn. 49) who probably subinfeudated it in the mid 12th century to the resident Foliot family. Ralph Foliot and his son Richard (who succeeded him) both held from Robert Foliot (d. 1186), bishop of Hereford, (fn. 50) and in 1205–6 the Skelbrooke heirs granted the service due from Richard's ½ knight's fee to Richard de Parco of Brightwell Baldwin, adding a further link to the feudal hierarchy. (fn. 51) Richard Foliot remained lord in 1235–6, (fn. 52) but around that time he and other interested parties granted the manor to the Knights Templar's preceptor of Cowley, moved soon afterwards to Sandford. (fn. 53) The preceptor owed suit of court to the de Parco overlords. (fn. 54)

The Templars retained the manor (reckoned in 1279 at a knight's fee) until the order's suppression in 1308. (fn. 55) A royal keeper accounted for its revenues in 1308 and 1311–12 (when William of Skelbrooke remained mesne lord), (fn. 56) but by 1324 it belonged to the Knights Hospitallers, who leased it with Easington to Sir John Stonor and his brother Adam. (fn. 57) Sir William Stonor held the lease in 1483, and Sir William Barentin (d. 1549) of Little Haseley from 1519. (fn. 58) In 1540 (following the Hospitallers' suppression) the manor reverted to the Crown, which in 1544 sold it to Barentin and others. (fn. 59) It seems later to have been divided between the Barentins and Harcourts, (fn. 60) but was reunited by Sir Christopher Hatton, who in 1588 sold it to Anthony Molyns, Michael Molyns, and John Simeon. (fn. 61)

Anthony Molyns (d. 1589) left his third to his daughters Margaret (wife of Martin Tichborne) and Anne (wife of John Simeon of Brightwell Baldwin, d. 1618), (fn. 62) while Michael Molyns's son Barentine retained another third in 1626. (fn. 63) John Simeon's son Sir George reunited the manor, however, and in 1631 sold it to Sir Robert Dormer (d. 1649) of Ascot, who was succeeded by his son Sir William (d. 1683). He or his son John sold it to Richard Blackall, one of a local landed family, who by the early 18th century had 'parcelled the land into five or six hands'; (fn. 64) six landowners still paid land tax in 1785, amongst them the farmer Henry Lewingdon, who claimed sporting rights. (fn. 65) Some consolidation occurred in the early 19th century, (fn. 66) and by the 1840s there were only three landowners, of whom William Cozens (owner of Manor farm) was the largest. (fn. 67) Their successors by the 1870s were John Stevens, Samuel Dickers, and Lyford's Abingdon charity, and three non-resident landowners remained in 1910. (fn. 68) After the First World War two of the parish's farms were bought by their tenants, William Franklin and George Nixey; (fn. 69) the Franklin estate was sold in 1949 to R.N. Richmond-Watson of Brightwell Baldwin, who sold it in 1955. (fn. 70)

Warpsgrove House ('in tyme paste a parish Church') as depicted in 1612.

Manor House (Warpsgrove House)

The location of the Foliots' house and of the Templars' grange (fn. 71) is unknown, but was probably close to the former church and village. (fn. 72) No later lords were resident, but in 1519 the lessee was given timber to repair 'houses standing upon the site of the manor', (fn. 73) and a building labelled Warpsgrove House was shown on a map of 1612 (Fig. 119). (fn. 74) The map-maker identified it with the former parish church (by then almost certainly in ruins), suggesting that the two lay closely adjacent. Possibly that was the house inhabited by a resident shepherd or yeoman in the early 17th century, (fn. 75) and Warpsgrove House was again mentioned in 1643 in an account of the Civil War battle of Chalgrove. (fn. 76) Its date of demolition is unknown.

The present Manor Farm was built probably by Henry Lewingdon in the early-to-mid 18th century, on a site some distance from the former church. (fn. 77) In 1874 it was brick-built and tiled, and included a parlour, sitting room, four bedrooms, and two attics, together with a range of outbuildings. (fn. 78) Following fire damage in 1956, (fn. 79) it was modernized and extended in the late 20th century. (fn. 80)

ECONOMIC HISTORY

THE AGRICULTURAL LANDSCAPE

Open fields probably covered most of the parish in the 13th and early 14th centuries. The lord's open-field arable lay intermingled with that of his tenants, much of it extending from headlands abutting the roadside, and in the 1230s Richard Foliot's demesne extended also into neighbouring Golder. Pasture was available in the allow field and in ditched closes, while meadow presumably adjoined the streams. (fn. 81) Woodland was scarce: in 1519 the manor included only 100 oaks dispersed in hedgerows and around the former manorial centre. (fn. 82)

The village's apparent desertion suggests that the open fields had been inclosed and laid down to grass by the mid 15th century, probably by the Stonors. (fn. 83) The parish remained almost wholly pasture in the 18th and 19th centuries (Fig. 118), (fn. 84) and though c.50 a. were cropped in 1880, agricultural depression led to renewed expansion of grassland over the following decades. (fn. 85)

MEDIEVAL TENANT AND DEMESNE FARMING

In 1086 the demesne contained land for two ploughteams, and the manor's annual value (as in 1066) was £4. (fn. 86) No meadow, pasture, or woodland was expressly noted, and arable farming remained dominant until the Black Death. Richard Foliot's grant to the Knights Templar in the 1230s included a barn (grangia) outside the main manorial curtilage, with six strips of land near a stream (rīth), 105 a. of demesne arable with its appurtenant meadow, two tenanted half-yardlands and a cotland, and pasture for a plough-ox and three cows. (fn. 87) In 1279 the two half-yardlanders owed cash rents of 2s. 6d. each, and ploughing, harrowing, threshing, and woodcarting services; one cottar held 4 a. for 2s. annual rent and harvest services, while eight others each held 1½ a. for services and 12d. rent. (fn. 88) Presumably some were also wage earners, like the inhabitant employed as a dairyman at Cuxham in 1289–90. (fn. 89)

Following the Templars' suppression in 1308, the royal keeper accounted for sales of grain including wheat, dredge, and maslin. Livestock included cattle, sheep, and horses (used for carting), while pigeons were bred in a dovecot. Tenants' services were already commuted, with demesne labour supplied by hired servants (famuli). Grain sales accounted for nearly a third of total receipts in 1311–12, when expenses included harvest-workers' wages and repairs to ploughs and carts. Repairs were also made to a wheat barn, granary, and dairy, and the costs of the sheep flock included medicines to treat scab and other diseases. (fn. 90)

From 1324 until the late 15th century the Hospitallers leased Warpsgrove and Easington to the Stonors of Stonor Park, initially for 10 years at an annual rent of £18. (fn. 91) In the 1470s Sir William Stonor (d. 1494) was a prominent wool exporter, who may have contributed to or taken advantage of the village's apparent desertion. Possibly he inclosed the open fields in order to extend his sheep grazing. (fn. 92)

FARMS AND FARMING SINCE 1500

The parish appears to have been largely uninhabited in the 16th century, and was probably used for grazing by outsiders such as Sir William Barentin (d. 1549), who leased the manor from 1519 at £13 6s. 8d. a year, and bought it in 1544, (fn. 93) subsequently keeping colts there. (fn. 94) A shepherd lived in Warpsgrove c.1593–1617, (fn. 95) presumably as a tenant of Barentin's successors, and the parish may have been more fully repopulated in the early 18th century following its division among five or six landowners. (fn. 96) The yeoman Charles White lived there c.1715–17 before moving to Rofford, (fn. 97) while others settled more permanently. (fn. 98)

Three farms were established by 1750, run by John Franklin (d. 1759), Henry Lewingdon (d. 1783), and Thomas Mott, who together complained to the bishop about tithe payments. (fn. 99) Around 1780 Franklin's son John occupied five closes totalling c.60 a., three of which produced an estimated 27 tons of hay each year. Two other closes were grazed by 12 dairy cows and 20 sheep and lambs, save for 6 a. planted with wheat and beans. Franklin employed day labourers from Chalgrove, but for the most part depended on family labour including that of his kinsman and lodger William Brown. (fn. 100) Mott's and Lewingdon's farms were apparently larger, and Mott remained for more than 40 years before retiring to Chalgrove c.1778, when he was succeeded by the grazier Richard White (d. 1796). (fn. 101)

Of Warpsgrove's three resident farmers in 1785, Franklin and the younger Henry Lewingdon (d. 1825) were owner-occupiers, while White leased his farm from two non-resident landowners. (fn. 102) Other outsiders included John Allnatt of Crowmarsh, whose three closes of meadow (covering 30 a.) yielded 30 tons of hay in 1779. (fn. 103) Additional freehold meadow was advertized in 1764 and 1772, and land regularly changed hands. (fn. 104) The agriculturalist Arthur Young was impressed at the yields of milk, meat, and manure produced by James Bonner's long-horned cattle in the early 1800s, (fn. 105) and White, Lewingdon, and John Franklin (d. 1802) made considerable profits. (fn. 106)

By the mid 19th century three ring-fenced pasture farms covered the whole parish. (fn. 107) Manor farm (168 a.), formerly Henry Lewingdon's, was let in the 1840s–60s to William Atkinson, who employed five workers; (fn. 108) at its sale in 1857 (when it was mostly grass) his annual rent was £376. (fn. 109) John Franklin's Lane farm was increased to 82 a. by Henry Saunders of Brightwell Baldwin, who sold it in 1837 to Hugh Hamersley of Pyrton; his tenant James Bryant ran it with one man in the 1850s, and was succeeded by his son William. (fn. 110) Hill farm (82 a.) covered the parish's northern quarter, and in 1848 was owned and occupied by Henry Hamp. (fn. 111)

In 1870 grass covered more than four fifths of the parish, supporting herds of c.80 dairy and other cattle, and 230 sheep. Fewer than 50 a. were sown with wheat, barley, and fodder crops. (fn. 112) Manor farm included a dairy and churn house, two stone and tiled cattle-feeding sheds, and three isolated cowhouses in the fields; it was sold in 1874, when the yearly tenant Thomas Smith paid an increased annual rent of £400. (fn. 113) During the agricultural depression of the late 19th and early 20th centuries the arable largely reverted to grass, but otherwise the parish's farming changed little, notwithstanding some decline in cattle and sheep numbers by 1910. (fn. 114)

From the 1880s Manor and Hill farms were run by bailiffs for non-resident landowners, while Lane farm was occupied in 1891 by George Nixey, one of a prolific local farming family with interests in several parishes. (fn. 115) In 1920 Nixey purchased the farm, which he managed from Langley Hall in Chalgrove; likewise William Franklin, tenant (and later owner) of Manor farm, combined it with Manor farm in Chalgrove. (fn. 116) In 1941 Nixey kept 44 cattle on his still 82-a. grass farm, employing a single worker. Manor farm (owner-occupied by S.C. Franklin) maintained 92 cattle and 128 sheep on 167 a. of meadow and pasture, while 20 a. (probably in Chalgrove) were cropped with wheat and oats. (fn. 117) The farmhouses at Manor and Lane farms were retained, but Hill Farm was demolished in the 1920s or later, and its land (still 82 a.) farmed from outside the parish. (fn. 118)

SOCIAL HISTORY

SOCIAL CHARACTER AND THE LIFE OF THE COMMUNITY

Warpsgrove's 12th and early 13th-century lords were probably resident: both Ralph and Richard Foliot were 'of Warpsgrove', (fn. 119) and almost certainly occupied the manorial buildings which they granted to the Templars in the 1230s. (fn. 120) In 1224 an opponent in a land dispute was briefly imprisoned in their house there, and about the same time Pyrton's vicar accused Richard Foliot of altering the Warpsgrove–Standhill boundary to his own benefit, stealing the vicar's plough, trespassing in his meadow, uprooting trees, and damaging buildings. (fn. 121) Foliot's tenants included unfree peasants and cottars as well as freemen, of whom several followed Foliot in granting land to the Templars. By 1279 only one free tenant (Agnes Pyron) remained. (fn. 122)

The Templars maintained a grange at Warpsgrove, from which they also managed their Easington estate. (fn. 123) In 1306 they paid 18s. 10d. in tax out of a total parish assessment of 22s. 4½d.; (fn. 124) the other taxpayers were presumably tenants, who appear to have formed a small but relatively prosperous community. Particularly prominent were the Woodrows: Ralph Woodrow was assessed in the period 1306–27 on goods worth between £3 11s. and £6, although other family members were less well off. John Lovel's taxable goods increased in value from £6 in 1316 to more than £8 in 1327, when Henry of Warpsgrove, exceptionally, paid on goods worth £12 10s. By contrast Geoffrey James was taxed on goods worth only £2, although noone in 1327 paid the minimum liability of 6d., and in 1334 the parish's assessment of £1 14s. 4d. was relatively high for so small a place. (fn. 125) Two Warpsgrove inhabitants were involved in 1348 in an attack on Little Haseley. (fn. 126)

Following the Black Death only 12 adult inhabitants paid the poll tax of 1377, although families such as the Lovels remained, and in 1432 provided a parish tithingman. (fn. 127) By 1453, however, Warpsgrove was reportedly deserted, and seems to have remained so until the late 16th century, when a resident shepherd was presumably one of several livestock keepers occupying temporary or permanent dwellings for all or part of the year. (fn. 128) No other inhabitants are known until 1710, when an order was issued to remove a man 'of disordered mind' to Tetsworth where he had lived 12 years previously. (fn. 129) The White family were resident by 1717, (fn. 130) while parish tithingmen in the period 1713– 20 included Thomas Baker, Joseph Dewberry, John Franklin, Francis Lewingdon, and Richard Wade. (fn. 131)

Resettlement was presumably associated with creation of the three 18th-century farms run by the Franklins, Lewingdons, and Motts: (fn. 132) Thomas Mott's son was born in the parish in 1735, and some other resident families (notably the Whites) had children baptized at Chalgrove or Great Haseley in the 1740s– 70s. (fn. 133) The farmer John Franklin was resident in 1754, and though Henry Lewingdon and Mott then lived in neighbouring parishes, (fn. 134) all three subsequently settled at Warpsgrove, where Lewingdon employed a gamekeeper. (fn. 135) An illegitimate birth was noted c.1790. (fn. 136)

In 1801, 12 out of Warpsgrove's 25 inhabitants were employed in agriculture, most of the others (including 10 females) presumably comprising wives and children. (fn. 137) Resident labouring families included the Spicers and Terrys, who each had at least eight children during the period 1809–32. (fn. 138) Several older families (including the Franklins and Lewingdons) moved away, but the 70-year-old farmer Henry White remained in 1841, (fn. 139) and while many inhabitants lived in the parish for only a few years as farmers, labourers, or servants, others remained considerably longer. (fn. 140) Few had been born in Warpsgrove even by the end of the century, although most (like the Coleses and Kings of Chalgrove and the Nixeys of Brill) came from nearby. (fn. 141)

Warpsgrove (right) and the adjoining Chalgrove airfield in 1943, showing ridge and furrow and other features around Warpsgrove, and the wide scatter of war-time Nissen huts. North is towards top right.

Social and community activities (including religious worship) focused presumably on neighbouring villages, save for the brief appearance of Nonconformist meetings at Henry Lewingdon's house c.1803. (fn. 142) During the Second World War Chalgrove airfield brought a temporary influx of RAF and USAAF personnel, billeted in ten or so Nissen huts near Manor Farm. (fn. 143) Thereafter, Warpsgrove remained too small to maintain much separate identity.

EDUCATION AND POOR RELIEF

Warpsgrove had no school, most children from the 19th century attending that at Chalgrove. (fn. 144) Poverty amongst the parish's farm workers increased poor-relief costs from just 10s. 6d. in 1776 to more than £19 a year in 1783–5, and though no parishioners received relief in 1803, five were helped occasionally in 1813–14 and seven in 1815, when annual costs averaged £28. (fn. 145) Expenditure peaked in 1820 at £42 4s. (over 31s. per head), then fell intermittently to £10 2s. in 1834, (fn. 146) when the parish became part of Thame Poor Law Union. (fn. 147) No charities are known.

RELIGIOUS HISTORY

Despite its small size Warpsgrove had its own church in the Middle Ages, but following the village's desertion in the 15th century it fell into disrepair and was eventually demolished, leaving no evidence of its size or quality. The living was exceptionally poor, and thereafter became a minor sinecure for non-resident rectors. Inhabitants presumably attended church or chapel elsewhere, although Manor Farm was briefly licensed for Protestant Dissenters in the early 19th century.

CHURCH ORIGINS AND PAROCHIAL ORGANIZATION

The church (dedicated to St James) was probably built by the resident Foliot family in the 12th century, and by the early 13th was apparently fully independent. (fn. 148) The date of its destruction is unknown, but as the village was apparently deserted by 1453, the church, too, was presumably abandoned. (fn. 149) Rawlinson thought it 'long since entirely demolished' in the early 18th century, (fn. 150) although some fabric may have survived in 1762, when it was said to be disused and in ruins. (fn. 151) By 1780 all trace had gone, and the abandoned site (a close called Chapel Heath) was marked on later maps. (fn. 152) The last rector resigned in 1782, (fn. 153) when the parish was presumably served from Chalgrove. Nevertheless Warpsgrove remained a separate ecclesiastical parish within Aston rural deanery until its unification with Chalgrove in 1932. (fn. 154)

Advowson

In 1205 Chertsey abbey unsuccessfully disputed Richard Foliot's possession of the advowson, (fn. 155) which he gave to Dorchester abbey c.1220. (fn. 156) The abbey presented the first known rector in 1244, (fn. 157) and in 1459 granted the advowson to Edmund Rede (d. 1489), who gave it to the Austin friars at Oxford in 1462. (fn. 158) The grant failed to take effect, and patronage remained with the Redes until 1551, when Leonard Rede's daughter Katherine and her husband Thomas Dynham sold it to William Byrte. (fn. 159) Thereafter it belonged to successive laymen and clerics including Thomas Jones, Giles Bingley, and Thomas Sheppard, (fn. 160) who sold it in 1723 (for £200) to John Worth (or North) of Cornwall. In the later 18th century the advowson was owned by the Cornish families of Pearce and Cregoe, (fn. 161) though the Crown presented the last rector by lapse in 1779. (fn. 162) Edward Cregoe (d. 1799) left the patronage to his four daughters, the whole eventually passing to Mary Rouse, who sold it to the Ecclesiastical Commissioners in 1911. (fn. 163)

Glebe and Tithes

In 1254 the church was valued at only 13s. 4d., the poorest in the deanery, (fn. 164) and though the glebe covered 15 a. in 1279, the parish was omitted from the papal taxation of 1291. (fn. 165) By 1341 the church was worth £1 6s. 8d., rising to £2 13s. 4d. in 1526 and 1535; (fn. 166) from this the rector paid (by the 15th century) a 3s. 4d. annual pension to Dorchester abbey, which retained it after relinquishing the advowson. (fn. 167) The lessee of Great Haseley's tithes (Edmund Gadbury) was in dispute over Warpsgrove's tithes in 1512, (fn. 168) when the rector of Warpsgrove was non-resident and almost certainly let both tithes and glebe for a fixed rent. In 1530 his lessee was William Barentin, the tenant (and later owner) of the manor. (fn. 169)

From 1694 the parish's landowners paid a £20 modus to the tithe owner (and later patron) Mr Pearce, (fn. 170) and in the 18th century the whole of the rectory's annual income of £30 was assigned by Richard Eastway (rector 1721–77) to a 'poor decayed family', whose claim was unsuccessfully challenged by the inhabitants and (later) by Eastway's successor. Robert Holmes (rector 1779–82) reportedly spent almost £200 in legal fees seeking to re-establish his right, his failure and subsequent resignation probably contributing to the end of presentations to the benefice. (fn. 171) Thereafter the patron Edward Cregoe (d. 1799) claimed the tithes, which descended with the advowson. (fn. 172) In 1848 they were commuted for a rent charge of £20, despite a claim that they were actually worth £60 a year, (fn. 173) and in 1911 they were sold with the advowson to the Ecclesiastical Commissioners for £400. (fn. 174)

PASTORAL CARE AND RELIGIOUS LIFE

David 'the priest of Warpsgrove' witnessed an Easington deed in the late 12th or early 13th century. (fn. 175) Otherwise Warpsgrove's earliest known rector (instituted in 1244) was Robert of Watlington, a local man who, since he was obliged to serve the church 'like a vicar', presumably resided. (fn. 176) Robert of Aston (instituted 1272), perhaps from Aston Rowant, must have been resident in 1294 when he was required to assist the then blind rector of Easington, (fn. 177) while Henry de Langebergh (instituted 1307) was an executor of Adam Stonor's will in 1326. (fn. 178) Probable non-residents include Eleanor of Castile's chaplain Roger (d. 1272), who while rector of Warpsgrove in 1264 was nominated for a prebend or other benefice in the bishop of Lincoln's gift. (fn. 179)

Baldwin de Bereford (d. 1405) left 3s. 4d. to maintain the church's fabric, (fn. 180) but in the 1420s and 1440s several rectors resigned after only short periods, presumably because of the church's poverty. (fn. 181) Falling population may have also discouraged residence: both Edward Bland (rector 1441–3) and Master John Smart (1443–9) were pluralists, (fn. 182) and with the village's apparent desertion by 1453 (fn. 183) the rectory became a sinecure. Probably it was used by the Redes as an easy form of patronage, Richard Richardson (rector 1487–1500) numbering among the witnesses to Edmund Rede's will. (fn. 184) If a rectory house existed it was not maintained, and the church fell into disrepair, while the glebe seems to have been lost and no parish registers (compulsory from 1538) were compiled. (fn. 185) Clearly the rectors' chief interest in the parish was its tithe income, over which John Newton (rector 1501–25) was in dispute in 1512. (fn. 186)

The rector at the Reformation was Reynold Harrison, (fn. 187) and twelve successors are known between 1560 and 1782. (fn. 188) Most were Oxford graduates, (fn. 189) including the religious controversialist Edward Boughen (instituted 1620). (fn. 190) The father of Giles Bingley (rector 1639–42) presented his son's successor Thomas Sheppard, to whom he also sold the advowson, (fn. 191) while a later Thomas Sheppard presented Richard Eastway (rector 1721–77). Eastway lived near Market Harborough (Leics.), and claimed to have accepted the benefice at a friend's request, out of charity to the family on whom he bestowed the rectory's entire income. The arrangement prompted complaints from Warpsgrove's resident farmers, who likened tithe payment in a parish without a priest to a shepherd appearing only at shearing time to collect the fleece. The evidence submitted suggests that neighbouring clergy may occasionally have held services at Warpsgrove, though if so it is unclear where. Possibly they were performed at the site of the ruined church, (fn. 192) where Eastway's successor Robert Holmes was inducted in 1779. (fn. 193)

Holmes's attempts to replace the £20 tithe modus with a larger levy prompted further objections from farmers, and following the failure of a non-payment case against John Franklin, Holmes resigned in 1782. (fn. 194) No later rector was presented, probably encouraging Dissent, and in 1803 Nonconformist meetings were licensed in Henry Lewingdon's house (Manor Farm). (fn. 195) By then most inhabitants presumably attended church or chapel in Chalgrove or other nearby places, and at his death in 1825 Lewingdon left a £10 annuity to Chalgrove's Baptist meeting house. (fn. 196)

LOCAL GOVERNMENT

In the Middle Ages the Foliots and their successors presumably held regular manor courts, which in 1311–12 yielded 5s. 2d. A constable was named in 1377, (fn. 197) but how long the courts continued is unknown. Tenants also owed suit to Ewelme hundred court, (fn. 198) and from the 15th to the 19th century were represented at the hundred's (and later the honor's) views of frankpledge by separate tithingmen. (fn. 199)

Poor relief was perhaps administered informally by resident farmers, since no parish officers are known. (fn. 200) From 1834 the parish belonged to Thame Poor Law Union, and from 1894 to Thame Rural District; (fn. 201) it was transferred to Bullingdon Rural District in 1932, when the civil parish was united with Chalgrove. (fn. 202)