A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 18. Originally published by Boydell & Brewer for the Institute of Historical Research, Woodbridge, Suffolk, 2016.

This free content was digitised by double rekeying. All rights reserved.

'Newington (Including Berrick Prior, Britwell Prior, Brookhampton, Holcombe)', in A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 18, ed. Simon Townley (Woodbridge, Suffolk, 2016), British History Online https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/vch/oxon/vol18/pp303-341 [accessed 31 January 2025].

'Newington (Including Berrick Prior, Britwell Prior, Brookhampton, Holcombe)', in A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 18. Edited by Simon Townley (Woodbridge, Suffolk, 2016), British History Online, accessed January 31, 2025, https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/vch/oxon/vol18/pp303-341.

"Newington (Including Berrick Prior, Britwell Prior, Brookhampton, Holcombe)". A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 18. Ed. Simon Townley (Woodbridge, Suffolk, 2016), British History Online. Web. 31 January 2025. https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/vch/oxon/vol18/pp303-341.

In this section

NEWINGTON

Until modern boundary changes the main part of Newington parish, located in the Thame valley c.14 km south-east of Oxford, comprised the four tithings of Newington (site of the parish church), Berrick Prior, Holcombe, and Brookhampton. Each had its own fields, and was usually taxed separately. A detached chapelry at Britwell Prior lay 7 km to the south-east, its houses and fields closely intermixed with those of Britwell Salome parish in Lewknor hundred, while a detached woodland area lay on the Chilterns above Watlington. (fn. 1) The whole parish (Holcombe apart) derived from an estate granted to Canterbury cathedral priory in the 11th century, and ecclesiastically it remained a peculiar attached to Canterbury diocese until 1846. Britwell Prior chapel was served from Newington until its demolition in 1865, its frequent neglect contributing to the growth of a Roman Catholic mission in Britwell in the 17th-18th centuries.

Economically the parish relied on mixed farming, with rural crafts and trades concentrated around the turnpike road through Brookhampton and Holcombe. Country houses at Newington and Britwell were built for resident lords c.1679 and in 1727–8, while piecemeal inclosure swept away village greens and several cottages at Newington and Berrick Prior in the 17th and early 19th centuries. Most fringe settlements were transferred to other parishes in the late 19th and 20th centuries, leaving only Newington and Holcombe within the modern civil parish.

PARISH BOUNDARIES

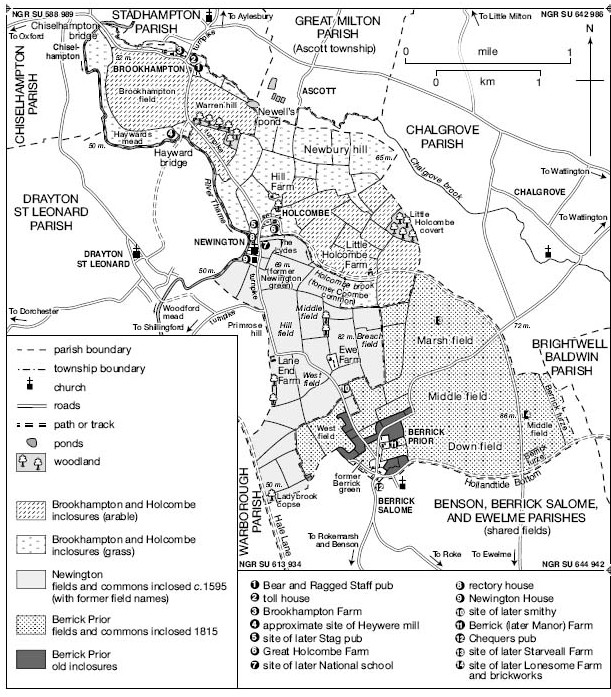

The parish's shape (Figs. 84–5) was determined by Queen Emma's grant of estates at Newington and Britwell to Canterbury cathedral priory between 1017 and 1035, reflecting the fragmentation of Benson's royal estate. The grant included practically all of the later parish, and though Holcombe initially remained attached to Benson, its proximity to Newington church suggests that it was probably absorbed into the emerging Newington parish at an early date. (fn. 2) A further consequence of Emma's grant was that Berrick, Britwell, and Holcombe became permanently divided between Newington and adjoining parishes and lordships. (fn. 3)

The ancient parish's main part was mostly defined by prominent landscape features, (fn. 4) including (on the west) a long section of the River Thame. Boundaries in the south-west, south, and south-east (bordering Warborough, Berrick Salome, and Ewelme) largely followed probable Roman roads, (fn. 5) while the eastern boundary with Chalgrove followed a track and hedgerow, excluding on the north the streamside meadows included within Chalgrove manor and parish. (fn. 6) The rest of the northern boundary followed Chalgrove brook, which like the Thame (into which it empties west of Brookhampton) formed part of the hundred boundary. In 1881 that main part comprised 2,116 a., including 5 a. of meadow at Drayton St Leonard. (fn. 7) The internal township boundaries mainly followed field divisions, while Holcombe brook separated Holcombe from Newington. (fn. 8)

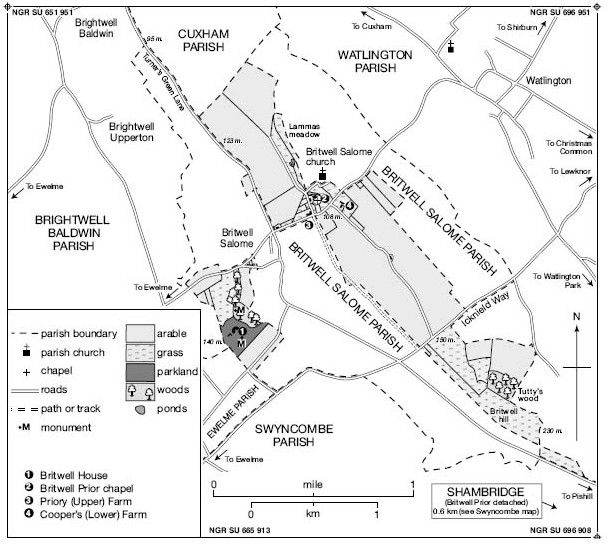

Britwell Prior chapelry lay detached, and until the 19th century remained closely intermingled with adjoining Britwell Salome. The two shared a field system which presumably pre-dated the 11th-century changes, its individual strips titheable to one of the two parishes, while houses, too, lay intermixed. (fn. 9) At inclosure in the 1840s the boundaries were rationalized, with Britwell Prior defined as three separate parcels encompassing 720 a. in all. The largest (467 a.) included the chapel and Priory Farm and the smallest (77 a.) Britwell House and its park, while the third parcel (175 a. on the Chilterns at Shambridge) was probably unaltered since the Middle Ages, when woods there belonged to Newington manor perhaps as part of Emma's pre-Conquest grant. (fn. 10) The Britwells' western boundary with Brightwell Baldwin and northern boundary with Cuxham were certainly of Anglo-Saxon origin, being described in charters of 887 and 995. (fn. 11)

From the 19th century the parish (2,836 a. in total) (fn. 12) was reduced by successive boundary changes. For ecclesiastical purposes Shambridge was transferred to Pishill in 1854, (fn. 13) and in 1867 the rest of Britwell Prior was annexed to Britwell Salome. (fn. 14) For civil purposes Newington lost 5 a. to Drayton St Leonard in 1882, while Brookhampton (271 a.) was transferred to Stadhampton in 1932, and Berrick Prior (41 a.) to Berrick Salome in 1992. (fn. 15) Britwell Prior formed an independent civil parish from 1866 to 1912 when it was merged with Britwell Salome, the resulting Britwell parish losing Shambridge to Watlington in 1932. (fn. 16) In 2011 the surviving civil parish of Newington covered 1,799 a. (728 ha). (fn. 17)

Newington parish (excluding Britwell Prior) c.1840, showing boundaries, inclosures, and key buildings.

Britwell Prior township (shaded) c.1880, showing boundaries defined at inclosure in 1842–5.

LANDSCAPE

The parish's main part occupies gently undulating farmland, rising from the River Thame (at 50 m.) to Newbury hill in the north-east (65 m.), and to Ewe Farm (82 m.) in the centre. Berrick Prior, in the south, lies at 57 metres. Meadows and pastures along the river and Chalgrove brook occupy alluvium accumulated through regular flooding; elsewhere the parish lies mostly on Gault Clay, giving stiff soil containing mudstones, while around Ewe Farm and east of Berrick Prior a lighter loam based on Upper Greensand supported furze until inclosure. Springs break out north-east of Berrick Prior at the junction of the Clay and Greensand, flowing into the hamlet down the narrow valley of Hollandtide Bottom, (fn. 18) which in 887 was called holandene or 'hollow valley'. (fn. 19) A pond there was formerly used to dip sheep. (fn. 20) Holcombe (also 'hollow valley') is probably similarly named from the shallow valley of Holcombe brook, (fn. 21) a short stream which rises north of Ewe Farm and empties into the Thame north of Newington. A pump beside it supplied Newington and Holcombe residents until the arrival of piped water in the early 1950s. (fn. 22) Woodland is scarce, concentrated in coverts planted in the 19th and 20th centuries. (fn. 23)

Britwell Prior's landscape is markedly different, formed almost entirely from chalk, and rising steeply from the edge of the Oxford vale in the north (110 m.) to the high Chilterns (230 m.) in the south, where ancient woods at Shambridge ('sandy ridge') occupy hilltops capped with clay-with-flints. Britwell House stands at 140 m. on a hillock composed of clay, sand, and gravel. Surface water is largely absent except around the chapel site, where a spring at the junction of the chalk and clay gave rise to Britwell's place name. (fn. 24) A pond there was preserved as a common watering-place at inclosure. (fn. 25) The detached Chiltern woods apart, Britwell Priors light and well-drained soils traditionally supported arable and sheep pasture, with just a few small pockets of meadow near the spring. (fn. 26)

COMMUNICATIONS

Roads and Bridges

The principal route through the parish's main part, passing through Brookhampton, Holcombe, and Newington, formed part of the road from Aylesbury (Bucks.) to Shillingford, turnpiked in 1770 and disturnpiked in 1875. (fn. 27) A tollhouse with tollgates stood at Brookhampton (Fig. 86). (fn. 28) The section south of Holcombe was called 'Wallingford way' in 1490, (fn. 29) and part of the route was mapped in 1595, when a bridge crossed Holcombe brook and a gate spanned the road close to Newington manor house. (fn. 30)

Numerous branch roads were recorded early on. At Lane End (perhaps the 'King's Lane End' of 1490), (fn. 31) the branch to Berrick follows a sharp right-angled turn, which in 1595 formed a T-junction with a continuation of the north-south road along the parish boundary, running towards Warborough. (fn. 32) 'Ascott way', mentioned in the early 14th century when the lord of Holcombe narrowed it, may have been a branch road further north, leading from Holcombe to Ascott in Great Milton, and called a 'pack and prime way' in 1621 and (possibly) 'Sile Lane' in 1694. (fn. 33) If so it was lost by 1826. (fn. 34) Another branch from Holcombe, called 'Coll waye' in 1595, (fn. 35) formerly continued eastwards past Little Holcombe to intersect with routes to Chalgrove and Ewelme, (fn. 36) and was subject to protracted litigation from the 1970s. (fn. 37) Westward routes included the Oxford road from Brookhampton over Chiselhampton bridge, the subject of a legacy by a rector of Newington in 1425, (fn. 38) while a predecessor of Hayward bridge, on the road to Drayton St Leonard, was recorded in 1490 (fn. 39) and succeeded by the present road bridge in 1884. (fn. 40) The Berrick-Chalgrove road is presumably also medieval.

Several of those routes were apparently derived from Roman roads. The former turnpike south of Holcombe may partly follow the Roman road from Dorchester to Fleet Marston (Bucks.), which further north may have coincided with the lost 'Ascott way'. Alternatively the Roman road may have forded the Thame at Hayward bridge, passing south-east of Brookhampton up to Little Milton. (fn. 41) Further south, the Romanized Lower Icknield Way ran probably along Hollandtide Bottom and through Berrick Prior, forming part of the parish boundary, (fn. 42) while at Ladybrook copse it crossed another probable Roman route, partly preserved in the line of Hale Lane. (fn. 43) In the south-east, the straight north-south lane past Lonesome Farm to Ewelme was apparently called 'le Stretewey' and 'Akmanstrete' in 1490, suggesting Roman origins, and similarly formed a stretch of parish boundary. (fn. 44) Britwell Prior chapelry was crossed by the main Icknield Way, which follows the Chiltern scarp, while the Benson-Watlington road through both Britwells is probably also ancient. (fn. 45) Turner's Green Lane in Britwell Prior was called a 'fielden way' in 995. (fn. 46)

Carriers and Post

Brookhampton had a carrier in 1835, (fn. 47) and in 1847 John and William Payne ran regular services from there to London, Oxford, Eynsham, Witney, and Burford. (fn. 48) The London service continued until c.1890, when the Holcombe beer retailer and (later) grocer Thomas Moores started carrying to Abingdon and Oxford, and another carrier passed through on his way to Wallingford and Oxford. The Moores family's service continued until the 1920s. (fn. 49) Britwell Prior was served in 1854 by a Watlington carrier, who stopped there weekly on his way to Wallingford. (fn. 50) A weekly bus from Stadhampton to Wallingford was introduced in the 1940s, but later withdrawn. (fn. 51)

Most mail came through Wallingford, and a post office established in Brookhampton by 1881 was a money-order and telegraph office by 1883. (fn. 52) It moved to Stadhampton in the early 20th century, but returned to Brookhampton after the Second World War and remained open in 2014. (fn. 53) Britwell Priors letters were delivered through Watlington in the early 19th century, and by 1881 there was a post office in Britwell Salome. (fn. 54) A shop at Berrick Prior included a post office from the 1960s to 1980s. (fn. 55)

POPULATION

In 1086 Newington manor had 39 recorded tenants at Newington, Brookhampton, Berrick Prior, and Britwell Prior, with tenants at Holcombe presumably recorded under Benson. (fn. 56) Sixty-four tenants were recorded on the manor c.1200 (25 in Britwell Prior, 22 in Berrick Prior, 11 in Brookhampton, and 6 in Newington), (fn. 57) while respective numbers in 1279 were 15, 21, 14, and 15, a total of 65. Another 11 lived at Holcombe alongside the resident lord. (fn. 58) Taxpayers in 1327 included 12 people in Britwell Prior, 10 in Brookhampton, 9 each in Holcombe and Newington, and 33 in Berrick (probably including Berrick Salome), placing the parish as a whole amongst the most populous in the hundred. (fn. 59) The Black Death reduced population particularly at Britwell Prior, where only 4 people aged over 14 paid poll tax in 1377 compared with 47 in Berrick Prior, 43 in Newington, 31 in Holcombe, and 21 in Brookhampton. The parish total of 146 suggests an actual population approaching 400. (fn. 60)

The 1524 subsidy was paid by 28 heads of household, (fn. 61) and parish registers (extant from 1572) suggest a growing population. (fn. 62) Thirty five houses were assessed for hearth tax in 1662: 18 in Berrick Prior, 7 in Holcombe, 5 in Brookhampton, 3 in Britwell Prior, and only 2 in Newington, (fn. 63) where several cottages had been lost through inclosure. (fn. 64) Britwell Prior was said to contain six houses in 1685, (fn. 65) and the number in the parish as a whole was estimated at 55 in 1758. (fn. 66)

Total population grew from 247 in 33 occupied houses in 1801 to 471 in 94 houses in 1841, including 52 (occupying ten houses) at Britwell Prior. Thereafter the population generally declined until the 1920s, (fn. 67) when Britwell Priors figures were amalgamated with Britwell Salomes, and 229 people occupied 57 houses in the rest of Newington civil parish. Following a modest increase to 244 by 1931, subsequent boundary changes reduced the population to 129 (in 38 houses) by 1951, and to 104 (42 houses) by 2001. In 2011 Newington, Holcombe, and outlying farms accommodated 102 inhabitants. (fn. 68)

SETTLEMENT

Prehistoric to Anglo-Saxon Settlement

Despite abundant prehistoric and Roman archaeology in neighbouring parishes, (fn. 69) evidence for early occupation in Newington parish is scarce. A few sherds of late Bronze-Age or early Iron-Age pottery and some worked flints have been found south-east of Newington, (fn. 70) and a sunken-floored structure near Ewe Farm, containing a stone-lined hearth associated with significant quantities of late Bronze-Age pottery, has been tentatively interpreted as a craft or industrial building. (fn. 71) Structural evidence for Roman settlement is so far lacking, although the discovery of unabraded sherds of 2nd- or 3rd-century pottery near Newington House suggests that habitation was close by. (fn. 72) Several Roman metal objects (mostly coins) have been found in the fields between Newington and Berrick Prior. (fn. 73)

Anglo-Saxon settlements were sited close to reliable water supplies. Like neighbouring Brightwell Baldwin, Britwell grew up around its eponymous spring, while Brookhampton ('home farm by the brook') takes its name from the adjacent Chalgrove brook, and Holcombe from the valley of the Holcombe brook. (fn. 74) Berrick also developed near springs, its place name betraying its origins as an outlying dependency (or berewic) of the Benson royal estate. (fn. 75) An unlocated medieval field-name preserved the memory of a separate Anglo-Saxon royal farm or worth nearby. (fn. 76) Further north at Holcombe, a medieval grange granted to Osney abbey was referred to in 1270 as 'Kyngesbur' (king's burh), and possibly originated as an Anglo-Saxon royal residence associated with Benson. (fn. 77) From c.1300 it was more commonly called Newbury (new burh), perhaps reflecting Osney's 'new' ownership or rebuilding of it after c.1155. (fn. 78)

The early 11 th-century grant to Canterbury cathedral priory caused Britwell and Berrick to be each divided into two settlements, the parts belonging to the priory acquiring the place-name suffix 'Prior' during the later Middle Ages. (fn. 79) Then or possibly earlier Holcombe was similarly split, a part (called Little Holcombe in 1241) passing to the bishop of Lincoln and to Drayton St Leonard parish. (fn. 80) Newington ('new settlement'), situated between the two Holcombes, may reflect reorganization when the priory estate was created, marking the location chosen for the new church and manor house. (fn. 81)

Medieval and Later Development

Settlement after the Norman Conquest remained focused on the five main hamlets, with just a few outlying dwellings. Newington bears signs of medieval planning, its north-south row of three regular compounds between the village street and the River Thame containing the former rectory house, the parish church, and the manor house. Peasant housing stood a short distance south-east: a medieval smithy has been excavated there, and a 1595 map (Plate 3) shows up to ten cottages arranged either side of the street and on the edge of a small green. (fn. 82) The green itself (still there in 1648 with at least two dwellings) had been inclosed by 1767, with the loss of most if not all of Newington's cottages, (fn. 83) since only the rectory and manor house were assessed for hearth tax in the 1660s. (fn. 84) Additional houses were the outlying Ewe Farm (so called in 1722 and possibly established by 1595), (fn. 85) Lane End (formerly West Field) Farm, of probable 17th-century origin, (fn. 86) and a cottage north of Lane End, erected on manorial waste soon after 1795 but demolished in the early 20th century (fn. 87) Later building was small-scale. Hares Leap (formerly Starveall) was built c.1840 as outlying labourers' accommodation for Ewe farm, (fn. 88) and two semi-detached cottages near Newington House were built in the 1930s for domestic staff. Four council houses known as The Lydes were completed in 1949. (fn. 89)

Berrick Prior (see Fig. 19) was arranged until early 19th-century inclosure around a large irregular green at the convergence of five lanes: (fn. 90) the surname 'at green was recorded in 1306, and in 1270 there was a chapel. (fn. 91) Three or four surviving cottages are partly 17th-century, and the Chequers pub was licensed by 1754, its red and grey brickwork (Fig. 91) perhaps inspiring its name. (fn. 92) Manor Farm, ostensibly 18th-century, was formerly Berrick Farm, and though belonging to Newington manor until 1856 acquired its modern name only c.1860. (fn. 93) By 1805 an adjoining close was called Burnthouse, presumably recalling a dwelling destroyed by fire. (fn. 94) Following the green's inclosure in 1815 several houses on its northern and western edges were cleared, (fn. 95) the over-all number of dwellings falling from 32 in 1811 to 26 in 1821, and to 23 by 1895. (fn. 96) The outlying Lonesome Farm was built c.1840 to house a labourer (in 1861 a shepherd) on Berrick farm, (fn. 97) while a cottage and sometime smithy on the lane to Newington (demolished in the mid 20th century) existed by 1812. (fn. 98) Within the hamlet new bungalows were constructed in the 1960s, followed by further infilling. (fn. 99)

Holcombe developed around the junction of the Brookhampton-Newington road and a lane to Chalgrove and Ewelme. (fn. 100) Known as 'Up Holcombe' by the 13th century, presumably to distinguish it from Holcombe in Drayton St Leonard, (fn. 101) in the 19th century it was also called Great Holcombe, in opposition to Little Holcombe Farm c.1 km. south-east. (fn. 102) A D-shaped enclosure contained the manor house (now Great Holcombe Farm), (fn. 103) probably with medieval peasant housing grouped around, while the outlying Hill and Little Holcombe farms probably originated as medieval freeholds, perhaps respectively those known as Newbury (a grange of Osney abbey) and Skirmots. (fn. 104) Inhabitants 'of Newbury hill' were recorded in the 17th century, (fn. 105) some of them possibly living at Hill farmhouse which, in its present form, dates from c.1600. (fn. 106) Some surviving cottages are 17th-century, (fn. 107) and in 1821 there were 22 houses in the township; (fn. 108) small-scale infilling followed throughout the 20th century, including three houses built in a former orchard in 1986. (fn. 109) An isolated gamekeepers cottage mapped in 1826 was demolished after 1922, (fn. 110) and Little Holcombe Farm (with its large timber-framed barn) in the 1960s. (fn. 111)

The former turnpike tollhouse at Brookhampton in the earlier 20th century (looking east), with H.E. Upstone's stores to the left, and a former clothing factory (closed by 1901) to the right, fronting the Newington road.

Brookhampton adjoins Stadhampton to the north, but originated as a distinct settlement south of Chalgrove brook, focused on an important road junction. In 1270 it had a chapel. (fn. 112) The demolished Brookhampton Farm, as a copyhold of Newington manor, presumably occupied an ancient site, (fn. 113) while surviving buildings include the Bear and Ragged Staff pub (of 17th-century date and licensed by 1754) and the former tollhouse (c.1770). (fn. 114) In 1821 the hamlet comprised 16 dwellings, rising to 25 in 1841, (fn. 115) of which five stood on manorial waste. (fn. 116) A cottage opposite the tollhouse was demolished c.1860, and two on the Chiselhampton road shortly after 1938; some of their occupants moved into new houses along the Newington road and in a cul-de-sac named Warren Hill, where Nissen huts inhabited during the Second World War were succeeded by houses and bungalows. A bungalow farmhouse (Newell's Farm) was erected in 1955, and the grocers shop was rebuilt c.1960 following a fire. Brookhampton (or Taylors) Farm, a doublepile farmhouse probably rebuilt c.1800, was replaced in the late 1970s by a small housing development called Brookhampton Close, by then in Stadhampton parish. (fn. 117)

Settlement in Britwell Prior was mainly focused around the spring, which divided Britwell Salome parish church from Britwell Prior chapel (demolished in 1865). (fn. 118) In 1685 the rector of Britwell Salome described the two buildings as standing 'not above a bow's shoot from one another'; Britwell Prior then comprised six houses 'in the very midst' of Britwell Salome, two of them west of Britwell Salome village. (fn. 119) Presumably those represented plots granted to Canterbury cathedral priory, and intermingling persisted later, when Britwell House (built on farmland in 1727–8) and two or three cottages were separated from the rest of Britwell Prior by part of Britwell Salome. Priory Farm, immediately west of the chapel, probably occupies the site of Canterbury cathedral's medieval demesne farmstead, (fn. 120) while to the east a short-lived castle may have been erected during the Civil Wars of the 1150s. William of the Castle (de Castello) was mentioned c.1200, (fn. 121) and by the early 18th century the chapel was sometimes called 'Castle church', and the hillock on which it stood 'Castle hill'. (fn. 122) A church house mentioned in 1618 probably stood close by. (fn. 123) The present Priory (formerly Upper) Farm dates in part from c.1600, (fn. 124) and Cooper's (formerly Lower) Farm, recorded from 1717, was rebuilt in brick in the mid 18th century. (fn. 125) In 1821 the chapelry contained seven dwellings, (fn. 126) and in the 1880s Britwell House gained a park lodge and a gardener's cottage. (fn. 127) Twentieth-century building was confined to renovations and extensions of existing dwellings. (fn. 128)

A few additional dwellings existed in the chapelry's detached upland part at Shambridge. The surname 'of Shambridge' (de Samerugge) was recorded in the 13th century, (fn. 129) and Henry Piddington lived there in the 1630s. (fn. 130) Two cottages were erected in the 1850s, and in 1901 Shambridge's population totalled six people. (fn. 131)

THE BUILT CHARACTER

Only two domestic buildings are known to retain medieval work: Great Holcombe Farm, a former manor house with a 15th-century core, and Beauforest House (the former rectory, Fig. 92), which dates partly from c.1500. (fn. 132) Manor House (near the church) may preserve part of Owen Oglethorpe's manor house, built or rebuilt using Headington stone c.1578. (fn. 133) In the 1660s Newington's manor and rectory houses were the largest in the parish, with 12 and 10 hearths respectively; most other houses had 1 or 2 hearths, five had 3, and three (almost certainly including Great Holcombe Farm) had 4, (fn. 134) indicating (together with probate evidence) the presence of a few substantial yeoman farmhouses. (fn. 135) One is Priory Farm in Britwell Prior, in origin an L-shaped timber-framed and thatched farmhouse of c.1600 with two storeys and attics, and a massive central brick chimneystack. (fn. 136) In 1619 its rooms included a parlour, hall, kitchen, buttery, four chambers, and two lofts, (fn. 137) and in 1684 there was a 'new chamber', (fn. 138) while in 1662 it was assessed on five hearths. Other 17th-century examples include Hill Farm in Holcombe (timber-framed with an L plan and lobby entry), The Innocents in Berrick Prior (limestone rubble and thatched with mullioned windows and a central stair), and the Bear and Ragged Staff pub in Brookhampton (also of limestone rubble, originally with a lobby entry). (fn. 139)

Lowlier 17th-century buildings include Farthynge Cottage in Holcombe (timber-framed and thatched with a lobby-entry plan), Priory Cottage in Berrick Prior (limestone rubble and thatched), and Thatched Cottage in Berrick Prior (timber-framed and thatched). (fn. 140) Similar cottages (thatched with a mixture of timber framing, brick infill, and limestone rubble) formerly existed in Brookhampton, and others may have once surrounded Berrick Prior's green. (fn. 141) Several cottages and farmhouses were remodelled in the 18th century, including Hill Farm (which was extended and refaced in stone), and Great Holcombe Farm (where the timber-framed walls were encased in stone rubble and the building enlarged to provide a double-pile plan). (fn. 142)

Classical architecture arrived c.1679 with the construction of Newington House, a seven-bay mansion of three storeys over a basement built probably for Henry Dunch. Equally ambitious was Britwell House, a compact Palladian mansion built probably by William Townesend for Sir Edward Simeon in 1727–8. Both were remodelled in the late 18th century. (fn. 143) More modest houses with neo-classical features appeared after 1700, amongst them Priest's House in Britwell Prior (Flemish-bond red and grey brick), the former parsonage in Newington (largely rebuilt in 1796), and Garden House in Britwell Prior, like Ewe Farm (in Newington) a late Georgian brick-built house with hipped roofs. (fn. 144) Priory Farm's remodelling in 1826 was almost certainly commissioned by the lord of Britwell Salome Richard Newton, its L plan being converted into a square, and its principal entrance moved from the east to the south front, which took on a classical symmetry with brick walls, sash windows, and a hipped slate roof. In 1837 its farmyard (to the west) gained a weatherboarded and tiled barn. (fn. 145)

Victorian buildings comprise a few brick and tile cottages (some of those in Holcombe bearing datestones), (fn. 146) and Newington's red-brick former school of 1857. (fn. 147) From the 1930s new housing was erected along the Newington road in Brookhampton, and further building after the Second World War included four concrete-built council houses in Newington (refaced in brick in 1999), a few brick houses by the local builder Cecil Howlett, constructed from the early 1940s, (fn. 148) and numerous bungalows erected from the 1950s, some of them subsequently replaced with houses. (fn. 149) Priory and Cooper's Farms in Britwell Prior were extended for the farmer Richard Roadnight in 1958, (fn. 150) while Britwell House and Newington House were both renovated in the later 20th century, the former (in the 1960s) by the designer David Hicks. Hicks also restored several estate cottages. (fn. 151)

MANORS AND ESTATES

What became Newington parish belonged to Benson's royal estate until the early 11th century, when Queen Emma granted Canterbury cathedral priory an estate comprising Newington, Brookhampton, Berrick Prior, and the detached Britwell Prior. The priory retained the combined manor (called Newington) until the Dissolution, (fn. 152) establishing a manor house near the parish church. Thereafter the manor passed into lay hands, Britwell Prior becoming separated in 1600. The rest of Newington manor was broken up in 1856 when it covered 988 a., its manor house (Newington House) having been sold in 1776.

Britwell Prior manor acquired a manor house (Britwell House) in the 1720s, which remained the centre of a significant estate into the 20th century. House and manorial rights were parted in 1882, the latter remaining with owners of Brightwell Baldwin, with which both had descended for fifty years. Holcombe, excluded from Emma's grant, emerged as a separate manor from the 12th century, with a manor house probably at Great Holcombe Farm. Around 1600 it absorbed a separate Holcombe estate formerly owned by Osney abbey, and from 1632 until 1911 descended with Brightwell Baldwin. Thereafter the Holcombe estate (c.570 a.) was broken up.

NEWINGTON MANOR

The large Newington estate owned by Canterbury cathedral priory was granted them by Emma or Ælgifu, queen consort of Cnut, between 1017 and 1035, after it was forfeited by the thegn Ælfric. (fn. 153) In 1086 (when it included four houses in Wallingford) it was rated at 15 hides, including one held by Robert d'Oilly and another by Roger, probably Roger d'lvry. (fn. 154) The monks received free warren in their Newington and Britwell demesne c.1155. (fn. 155) Small-scale additions by purchase and gift were recorded in the later 13th century, (fn. 156) and in 1279 the manor included demesne in both Newington and Britwell, with numerous villein tenancies in all four of its settlements. (fn. 157) In 1392 the priory granted 2 marks a year from the manor to Balliol College, Oxford, in return for an Oxford house which it sold to Canterbury College. (fn. 158) The king took over the payment in 1542, following the priory's Dissolution. (fn. 159)

In 1544 Newington manor was granted to two London agents, who in 1546 sold it to John Oglethorpe (d. 1579) of Newington, a kinsman of the rector. (fn. 160) Johns son Owen (MP for Wallingford) (fn. 161) divided the estate in 1600, selling Britwell Prior to John Simeon, and the rest (known as Newington manor) to Edmund Dunch of Little Wittenham (Berks.). (fn. 162) Edmund (d. 1623) was succeeded by his son Walter (d. 1645) (fn. 163) and by Walters nephew Edmund Dunch of Little Wittenham, although Walter's widow Mary retained the manor house and some demesne lands for life. Both Edmund and Mary died in 1678, (fn. 164) when the whole estate passed to Edmunds son Henry (d. 1686), (fn. 165) who probably built Newington House. (fn. 166) Henrys widow Anne retained the manor until her death in 1690. (fn. 167)

Henrys daughter Elizabeth, at first a minor, (fn. 168) married in 1698 Cecil Bisshopp, son of Sir Cecil Bisshopp, Bt, of Parham (Sussex). Cecil succeeded to his fathers title and estates in 1705 and died in 1725, his widow surviving until 1751 when Newington manor passed to their son Sir Cecil Bisshopp, Bt. (fn. 169) He sold Newington House to George White in 1776 (fn. 170) but kept the manor until his death in 1778, when it descended with the baronetcy to Sir Cecil (d. 1779) and his son Sir Cecil (d. 1828), who in 1815 successfully claimed the dormant barony of Zouche de Haryngworth. His estates were divided between his daughters, of whom Katharine Arabella, wife of George Richard Pechell of Castle Goring (Sussex), received the Oxfordshire parts. (fn. 171) Her husband, a distinguished naval officer and politician, sold Culham and Newington in 1856, the latter in three lots: Ewe and Berrick farms (799 a.), meadow at Drayton St Leonard (3 a.), and Newington manor with Brookhampton farm and several cottages (186 a.). (fn. 172) Manorial rights subsequently lapsed, (fn. 173) and in the late 19th and early 20th century members of the Deane, Thomson, and Franklin families were the chief landowners in Newington, Brookhampton, and Berrick Prior. (fn. 174)

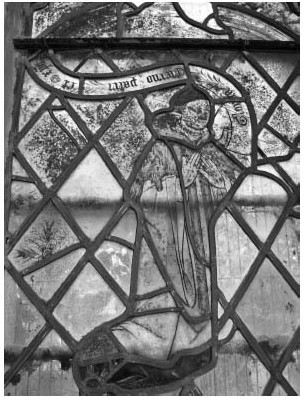

Manor Houses

Before c.1679 The priory's medieval manor house, which had a dovecot in 1479 (fn. 175) and where three chambers were reserved to the prior in 1533, (fn. 176) stood probably on or near the site of Newington House, and may have been the source of medieval glazed floor tiles found close by. (fn. 177) The Oglethorpes lived there after the Dissolution, (fn. 178) and c.1578 either the existing manor house was repaired or a new one built, using stone from Oriel Quarry in Headington. (fn. 179) 'Mr Oglethorpe's house' was subsequently labelled on a map of 1595 (Plate 3), standing south of the church, (fn. 180) and (as Newington Place) was later occupied by both Walter and Mary Dunch. (fn. 181) In 1665 it was taxed on 12 hearths. (fn. 182) The present-day Manor House, an L-shaped dwelling of 2½ storeys between the church and Newington House, may incorporate part of the building, although much of the visible fabric (coursed limestone rubble walls with ashlar and brick dressings) is probably late 17th-century (fn. 183)

Newington House Around 1679 a new manor house (known by the early 18th century as Newington House) (fn. 184) was built probably for Henry Dunch, of classical design and set back from the road on or near the site of its predecessor. (fn. 185) The double-pile building comprises a three-storeyed block above a basement, and is built of coursed limestone rubble with rusticated quoins and ashlar dressings. The principal façade has a central doorway flanked by triplets of sash windows, with two rows of seven windows above: the top storey was raised as part of a remodelling for George White in 1777, when a hipped Welsh-slated roof (re-using elements of the original) was constructed and a Corinthian porch added, together with a low service wing lit by Diocletian windows. Much of the interior, characterized by fine marble fireplaces and plaster cornices in each of the three principal rooms, dates from this remodelling, although 17th-century features in the basement include stop-chamfered beams and remains of a large fireplace. The grounds contain a stable block built c.1679 and a walled kitchen garden of similar date. (fn. 186) Contemporary stone gatepiers in front of the house were topped c.1700 with griffins (representing the Bisshopp crest), which hold later stone cartouches bearing the White arms. (fn. 187)

Newington House (built c.1679) from the east. The stone griffins on the gate piers represent the Bisshopps (owners 1698-1776), and the stone cartouches their successors the Whites.

The houses purchaser George White, a principal clerk in the House of Commons, died in 1789, (fn. 188) succeeded by his widow Letitia (d. c.1792), (fn. 189) their son George (d. 1813), (fn. 190) and Georges son Thomas Gilbert White (d. 1878). (fn. 191) It passed to the antiquary and lexicographer Sir George Floyd Duckett, Bt, who sold it before 1887 to J. Golby; (fn. 192) his successor W.A. Golby sold it between 1907 and 1910 to the tenant, the American artist and hostess Ethel Sands, who conveyed it in 1920 to Alex Wallace Gilmour. (fn. 193) He lived there until his death in 1946, later owner-occupiers including the former MP Alan Gandar Dower (1950–80), Christopher Maltin (1980–7), (fn. 194) John Barratt (1987–91), and John Nettleton. (fn. 195)

BRITWELL PRIOR MANOR

Britwell Prior manor originated in Owen Oglethorpe's sale in 1600 to John Simeon, (fn. 196) lord of neighbouring Brightwell Baldwin. After Simeons death in 1618 it descended in the direct male line to Sir George Simeon (d. 1664), (fn. 197) sometime of Watlington, and to James Simeon (d. 1709) of Chilworth in Great Milton and later of Aston (Staffs.), created a baronet in 1677. James's Roman Catholic (and bachelor) son Sir Edward Simeon, Bt, built Britwell House, where he lived from 1729 until his death in 1768. (fn. 198)

Simeon's heir, his Catholic great nephew Thomas Weld, (fn. 199) resided until 1775 when he inherited Lulworth Castle (Dorset) with his family's estates. (fn. 200) His Britwell estate covered 408 a. until 1797, when the greater part (including Priory and Coopers farms) was sold to his tenant John Stopes. Most of the rest passed on Thomas's death in 1810 to his fifth son James, who inherited the house on his mother's death in 1830 and sold the whole to William Francis Lowndes Stone of Brightwell Baldwin two years later. (fn. 201) Later lords of Brightwell Baldwin retained the manorial rights until at least 1939, (fn. 202) but the estate itself (Britwell House with 147 a.) was sold in 1882 to its tenant John Smith (d. 1888), (fn. 203) succeeded by his widow Emily Jane (d. 1914). (fn. 204) In 1920 Smith's son and heir sold it to Walter Curran, (fn. 205) who in 1926 sold it to Major George Cecil Whitaker (d. 1959); (fn. 206) he added property at Brightwell Baldwin, and in 1960 the enlarged 578-a. estate was bought by the interior designer David Nightingale Hicks. (fn. 207) He sold Britwell House with 150 a. in 1979, moving to Brightwell Baldwin, (fn. 208) and following various sales the house was bought in 1986 by Thomas and Cecilia Kressner, who owned it in 2014. (fn. 209)

Britwell House's main south-east front, with the commemorative column erected by Sir Edward Simeon.

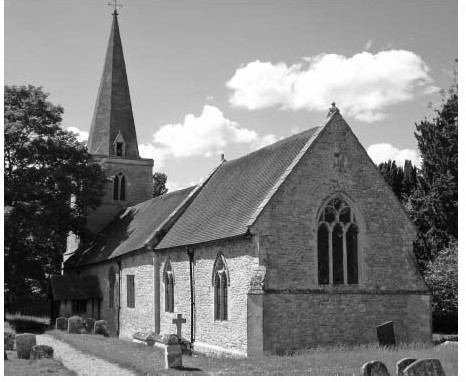

Manor House (Britwell House)

The Britwell estate had no manor house until Sir Edward Simeon began the existing Britwell House c.1727, set in 59 a. inclosed from the open fields to form a park. (fn. 210) The house was completed in 1728 and inhabited from 1729. (fn. 211) Designed probably by William Townesend of Oxford, it is built of red and blue brick with ashlar dressings and hipped slate roofs, and comprises a compact Palladian core of five bays and 2½ storeys with projecting pedimented centres, flanked by freestanding pavilions or service blocks linked to the main house by curved (and originally single-storeyed) corridors. The interior is notable for the comparative grandeur of its hall, staircase, and first-floor gallery at the expense of bedrooms and living accommodation. Original interior features include a heavy Doric frieze and massive Baroque chimneypiece in the hall, twisted balusters and fluted Corinthian columns as newel posts on the cantilever staircase, and Ionic pilasters and pedimented doorways around the walls of the gallery.

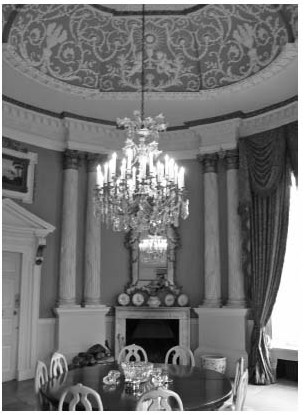

Between 1767 and 1769 an oval Roman Catholic chapel with a copper roof was built between the house and southern pavilion, designed probably by Simeon himself, although he died before its completion. The coved chapel ceiling (Fig. 90) is particularly fine, displaying ornate plasterwork reminiscent of that of James Paine at Wardour Castle (Wilts.). An adjoining two-storey annexe containing a sacristy, and perhaps originally a family pew in the room above, may have been added slightly later. In the late 19th and early 20th century the chapel was used as a billiard room, and the altar was replaced with a fireplace; further alterations attended the room's conversion to a dining room in the 1920s, including substitution of a rosette for the IHS monogram in the plasterwork ceiling. In the early 20th century a single-bay extension was added on the north-west side of the main house and both link-corridors were raised to two storeys, while David Hicks's restorations in the 1960s included installation of a Gothick fireplace in the drawing room. Outbuildings include stables and an early 19th-century brick coach house.

Two limestone ashlar monuments in the grounds were probably also designed by Simeon. A composite pillar supporting a flaming urn, c.90 m. from the house in direct line with the front door, bears a plaque (restored in 1970) dated 1764, inscribed to the memory of Simeons parents. A similar obelisk in the park to the north of the house is topped with a pineapple finial. (fn. 212)

HOLCOMBE MANOR

A ½ knights fee held of the honor of Wallingford in 1235, (fn. 213) and known later as Holcombe or Up Holcombe manor, (fn. 214) can be traced to part of the royal manor of Benson granted to Gilbert Angevin before 1155. Gilbert was succeeded in 1179 by Reginald Angevin, in 1214 by Reginalds son Maurice, and after 1242 by another Reginald, (fn. 215) whose Holcombe estate included ½ hide of demesne and a dozen tenanted holdings in 1279. (fn. 216) Ralph Angevin succeeded before 1300 and retained the manor in 1341, (fn. 217) but by 1356 it belonged to Richard English of Newnham Murren, (fn. 218) a king's yeoman granted free warren and a licence to crenellate his manor house at Holcombe in 1360. (fn. 219) The same year Richard settled the manor on his son Richard; (fn. 220) he or another Richard retained it in 1408, (fn. 221) but conveyed it in 1420 to Sir John Cottesmore, (fn. 222) lord of Brightwell Baldwin. Holcombe descended with Brightwell until 1528, when John (IV) Cottesmore sold it to his stepfather Thomas Doyley (d. 1545). (fn. 223)

In 1546 Doyley's son Robert sold the manor with other Holcombe property to Ambrose Dormer of Ascott (in Great Milton). (fn. 224) Dormer enlarged the estate (fn. 225) and died in 1566, leaving it to his widow Jane (d. 1594), who in 1574 married William Hawtrey Ambroses son and heir Michael (knighted in 1604) (fn. 226) sold it c.1609 to George Carleton (d. 1628) of Huntercombe in Nuffield, (fn. 227) from whom it descended to Sir John Carleton (d. 1637), Bt, and Sir George Carleton, Bt, (fn. 228) owner from 1639 of the Brightwell estate in Brightwell Baldwin. Thereafter Holcombe (576 a. in 1859) passed with Brightwell until 1911, (fn. 229) when it was sold to George Simmins of Croydon (Surrey). (fn. 230)

Simmins broke up the estate the same year, selling Little Holcombe farm (114 a.) to its tenant, and auctioning the remainder (c.450 a.) in 14 lots including Great Holcombe farm (189 a.) and Hill farm (165 a.). The lordship was sold to Henry Edwards Paine (d. 1917) of Chertsey (Surrey), whose trustees conveyed it in the early 1950s to John L. Beaumont of Lincoln's Inn (Middx). In 1955 he sold it to L.T. Harris of London. (fn. 231)

Manor House (Great Holcombe Farm)

The Angevins were resident by the 1270s or earlier, (fn. 232) and Richard English's licence to crenellate in 1360 suggests a remodelling of their manor house to include defensive features. Fifteenth- and 16th-century owners generally lived elsewhere, although Robert Doyley was apparently resident in 1546, (fn. 233) and George Carleton (d. 1628) was often described as of Holcombe. (fn. 234) Later lords all lived outside the parish.

Traces of the early manor house may have been encountered beneath the floor of Great Holcombe Farm in the early 1980s, when a hearth edged with medieval roof tiles was found to overlie a solid limemortared stone wall, which in turn sat upon building debris containing 12th- or 13th-century pottery. (fn. 235) The west range of the surviving farmhouse preserves the storeyed upper end (with a first-floor chamber) of a high-status open-hall house, possibly the manor house. Timber-framed and originally of five or six bays arranged north-south, it was partly constructed in 1475, (fn. 236) and has a crown-strut roof which retains some smoke-blackened rafters. In the 16th century a massive central brick chimneystack was inserted and the entire house ceiled, first-floor access being provided via a new timber-framed stair turret to the east. The house was later extended around the turret, beginning c.1600 with addition of a single bay on the north re-used from another medieval building, perhaps a detached kitchen. The medieval houses southern part was probably demolished around the same time, and the principal entrance moved from west to north. (fn. 237) Perhaps in the late 17th century an eastern range (south of the turret) was built with a cellar beneath, and in the early 18th century the whole house was remodelled to take on a unified double-pile plan, the timber framing encased in stone-rubble walls. Thatched barns forming a three-sided farmyard to the east were removed in the 20th century.

OTHER ESTATES

Two free tenancies at Berrick Prior in 1279 included a hide perhaps identifiable with one of those held by Robert d'Oilly or Roger d'Tvry in 1086. The tenant (Richard of Berrick) held it from the archbishop of Canterbury as 1/5 knights fee, and owed suit to the archbishop's court at Harrow (Middx), (fn. 238) having inherited it from his father Hugh (d. c.1271). (fn. 239) Its ownership is otherwise unrecorded.

Most medieval freeholds were in Holcombe, for which lords of Benson claimed quitrents into the post-medieval period. (fn. 240) One at Newbury belonged to Osney abbey from c.1155, when Henry II granted it with land in Warborough in exchange for a 245. prebend in Benson manor. (fn. 241) The estate comprised a ploughland (c.120 a.) c.1235, (fn. 242) and in 1270, when the lord of Holcombe unsuccessfully claimed a part, it included a headquarters (curia) called 'Kingsbury', adjoining Holcombe's fields. (fn. 243) The abbot was sole taxpayer in Newbury in 1306, (fn. 244) and by the early 16th century the property (then a single pasture close) was let to a local farmer. (fn. 245) In 1542 it was granted to Oxford cathedral, but was returned to the Crown in 1545 and sold to Christopher Edmonds. (fn. 246) He sold it to John Doyley of Chiselhampton, (fn. 247) whose brother Robert sold it to Ambrose Dormer with Holcombe manor in 1546. (fn. 248) Though still attached to the manor in 1591 (fn. 249) it passed shortly afterwards to George Calfield of Oxford, who sold it in 1593 to Owen Oglethorpe. He sold it to George Carleton in 1594 as two pasture and meadow closes totalling 120 a., and it remained part of Holcombe manor thereafter. (fn. 250)

A Holcombe freehold called Skirmots (perhaps Little Holcombe farm) comprised a house and ploughland in 1427, (fn. 251) and was sometimes called a manor. (fn. 252) Sir Gilbert Wace of Ewelme granted it in 1407 to William Skirmot (d. c.1450), (fn. 253) a Bristol merchant succeeded by his son John, (fn. 254) who lived at Holcombe until moving to Abingdon c.1479. (fn. 255) In 1484 he granted a 13-year lease to a tenant, reserving a parlour in the house and various outbuildings. (fn. 256) By 1526 the owner was Thomas Denton (d. 1534) of Caversfield (Bucks.), whose son John sold it in 1538 to William Doyley of Holcombe. (fn. 257) He added another freehold called Bennetts, and in 1561 Thomas Doyley sold both to Ambrose Dormer of Holcombe manor. (fn. 258) Michael Dormer sold them in 1589 to Owen Oglethorpe, (fn. 259) from whom they passed to Sir William Glover (d. 1603) of London following default on a mortgage. Glover's widow and son sold them in 1606 to George Carleton, who reunited them with Holcombe manor. (fn. 260)

ECONOMIC HISTORY

Newington's economy has long been agricultural, with crafts and retail employing only a small percentage of the population. Shops and businesses were mostly focused on the turnpike road in Brookhampton and Holcombe, although a grocers shop in Berrick Prior was run from the Chequers pub for nearly two centuries. Sheep-and-corn husbandry predominated, and until the early 19th century much of the farmland was worked in open fields; exceptions were Newington and Holcombe townships, where some arable was converted to inclosed pasture relatively early. Dairying was concentrated in Holcombe and Brookhampton, whose riverside meadows provided hay. Extensive Chiltern woods belonged to Newington manor in the Middle Ages, while the Thame supported fish weirs and a watermill.

THE AGRICULTURAL LANDSCAPE (FIGS 84–5)

Except for Britwell Prior (which shared its fields with Britwell Salome), (fn. 261) each township had its own open fields probably by the late 11th century. Berrick Prior had three fields in 1288, (fn. 262) and four (of varying quality) in the 18th century, called Marsh, Middle, Down, and West. (fn. 263) The last was shared with Newington until c.1595, when the Newington part was inclosed with Newington's Hill, Middle, and Breach fields, almost certainly by the lord of Newington Owen Oglethorpe, who converted large areas to pasture. (fn. 264) Berrick's fields remained otherwise uninclosed until 1815. (fn. 265) Holcombe's fields were mentioned in 1270, (fn. 266) and were worked on a three-course rotation in 1647 when they included a 'bean field'. (fn. 267) All were fully inclosed by 1795, presumably by one of Holcombe's lords. (fn. 268) No details of Brookhampton's medieval fields are known, although furlongs were described in 1490, (fn. 269) and an open field survived there in 1795. Some 63 per cent of the parish's arable was then still farmed in common, comprising 100 a. at Brookhampton, 573 a. at Berrick Prior, and 381 a. at Britwell Prior. (fn. 270) The Britwell fields were inclosed by Act of Parliament in 1842–5, (fn. 271) and whilst Brookhampton saw no formal inclosure the process there was complete by 1839. (fn. 272)

Common meadows lay chiefly along the River Thame and Chalgrove brook in the west and north, with smaller pieces bordering streams and springs elsewhere. (fn. 273) The largest included Haywards mead at Brookhampton (called 'Heyweremede' in 1384), (fn. 274) which John Oglethorpe tried to inclose in the 1560s; (fn. 275) it remained common in 1795, when it covered 30 acres. (fn. 276) Additional strips (some of them mentioned c.1275) lay detached in Woodford mead in Drayton St Leonard. (fn. 277) Several meadows were lot meadow, their strips re-allocated annually, (fn. 278) and were regulated through Newington's manor court. (fn. 279)

Common grazing was allowed in the common meadows from Lammas (1 August), and in the open fields after harvest. (fn. 280) In 1490 Brookhampton's tenants had additional grazing in 'Cowlese' (a riverside pasture by Chiselhampton bridge), and those of Newington, Berrick Prior, and Brookhampton in 'Hylwork' or 'Hellewerk', a detached Chiltern wood evidently near Bix. (fn. 281) In the late 16th century Holcombe and Newington tenants shared a further common pasture (called the Coombe) by Holcombe brook, while Newington had a village green. (fn. 282) By 1795 neither Newington nor Holcombe had any remaining commons, though a total of 92 a. survived at Brookhampton (57 a.), Berrick Prior (29 a.), and Britwell Prior (6 a.). (fn. 283) Berrick Prior's village green (c.10 a.) was inclosed in 1815 with a 16-a. furze ground at Hollandtide Bottom, (fn. 284) while Brookhampton's commons were inclosed by 1839. (fn. 285) Britwell Prior's small common meadow was inclosed in 1845. (fn. 286)

Little inclosed land is recorded before 1500, although three Newington tenants held crofts c.1200, (fn. 287) and a few small closes were mentioned in 1489–90. (fn. 288) Osney abbey's Holcombe estate comprised a single large close called Newbury by the 1530s, (fn. 289) which after the Dissolution was split into a 100-a. pasture (Newbury hill) and 20-a. meadow (Newbury mead). (fn. 290) Other meadow and pasture closes in Holcombe and Brookhampton were mentioned in the late 16th century, (fn. 291) together with a group of old inclosures in Newington (called the Lydes) beside Holcombe brook. (fn. 292) By 1795 old inclosures comprised 43 per cent of titheable land in Brookhampton, 11 per cent in Berrick Prior (mainly orchards adjoining dwellings), and just 2 per cent in Britwell Prior, while Newington and Holcombe were wholly inclosed. (fn. 293) Newington manor house had an attached 30 a. known as the Park in the mid 17th century, (fn. 294) and in the 1720s Sir Edward Simeon inclosed 59 a. for parkland around Britwell House. (fn. 295)

Woods and Woodland Management

Much of the woodland attached to Newington manor in 1086 (described as one league square) lay on the Chilterns, in an area called Minigrove (or Maidensgrove) in Bix, Pishill, and Watlington. (fn. 296) Around 1200 the prior leased some of those woods to Peter of Bix reserving timber and firewood, (fn. 297) and in the 13th century most of the manors villeins were required to cart wood from Bix, for which they were allowed firewood and timber for repairs from a wood called 'Biggefrit'. (fn. 298) Illicit felling and pasturing in Minigrove was regularly reported, much of it by the abbot of Dorchester, who owned land in Pishill. (fn. 299) In 1436 there was confusion as to whether certain Watlington tenants were entitled to firewood and pasture there, (fn. 300) and in 1520–1 wood sales from Minigrove raised £2 2s. 6d. (fn. 301) After the Dissolution some of the woods may have been sold, (fn. 302) and the remainder (338 a. in the 18th century) (fn. 303) were separated from Newington manor in 1600. Thereafter they formed the greater part of the so-called Minigrove manor, which descended with Britwell Prior until 1830. (fn. 304)

Most other medieval woodland lay in the detached part of Britwell Prior called Shambridge, (fn. 305) which was presumably where William of Shambridge held ½ hide from the prior c.1200 by the service of sawing wood. (fn. 306) Possibly he was a predecessor of the Shambridge forester recorded in 1270. (fn. 307) Fifty trees from there were sold for 35s. in 1371–2, and the Shambridge woodward received 30s. in 1449–50. (fn. 308) Purchasers included Merton College, Oxford, which bought firewood and plough-timber for Cuxham manor in the early 14th century, (fn. 309) while occasional trespassers included Watlington men who broke in and pastured cattle there in 1517. (fn. 310) After 1600 Shambridge wood (then 85 a.) was attached to Minigrove manor, (fn. 311) and whilst the greatest profits in 1772–3 came from beech poles and faggots, smaller sums were raised from ash, oak (including bark), and elm. (fn. 312) A woodman to manage their Britwell Prior and Watlington woods was employed by the Welds in the early 19th century. (fn. 313)

Woods elsewhere in the parish were scarce, although a beech wood high on Britwell hill (10 a. in 1843) may have survived from the prior of Canterbury's medieval demesne wood in Britwell. (fn. 314) Part of Berrick Prior's West field, known as the Grove, was presumably also once wooded. (fn. 315) A few elms and other timber trees grew on glebe land in 1795, when Holcombe had 4 a. of coppice and Newington 2 a., (fn. 316) and by 1826 Holcombe had a further 17 a. of coverts. (fn. 317) By 1911 the coverts covered 26 a., and timber on Holcombe manor (principally elms) was worth £1, 255. (fn. 318)

MEDIEVAL TENANT AND DEMESNE FARMING

In 1086 Newington manor had 19 ploughteams on land sufficient for 18, implying pressure on resources. Six demesne ploughteams were worked by 5 servi, whilst 22 villeins and 10 bordars shared the remaining 13. The manors annual value was £15 compared with £11 in 1066, and besides its woodland it had 15 a. of meadow and two furlongs of pasture, worth 3 55. a year when stocked. Holcombe was presumably separately accounted for as part of Benson. (fn. 319)

By 1200 Newington manor was managed for Canterbury cathedral priory by two reeves chosen from leading tenants, of whom one acted for Britwell Prior. Each received a 45. stipend, with 1 a. of wheat and pasture for his draught animals alongside the lord's. (fn. 320) Both presented annual accounts to the priory (fn. 321) and reported to a bailiff, who was shared with the priory's Buckinghamshire manors. A visiting monk-warden (custos maneriorum) from Canterbury collected manorial profits at Newington twice a year, (fn. 322) and from the 1330s regularly met the warden of Canterbury College, Oxford, to arrange supplies of food and money for the college. In 1394–5 the college received £3 from the manor. (fn. 323)

During the Interdict of 1207–13 Newington manor was confiscated by the Crown and plundered for profit: almost all the demesne livestock and grain stores were sold, and the manors value in 1212–13 was a meagre £4 6s. 8d. (fn. 324) A swift recovery followed its return to Canterbury cathedral, and by 1286–7 gross income (including rents and court profits) totalled £57, leaving £21 after expenses. (fn. 325) The proceeds came partly from demesne farming, which until c.1370 drew on heavy tenant labour services and on hired farm servants or famuli, including (in the 1360s) four ploughmen, a carter, a shepherd, and a swineherd. (fn. 326) The demesne was apparently confined to Newington and Britwell Prior townships, the Newington part in 1279 comprising 200 a. of arable and 20 a. of meadow, with pasture for 12 oxen and 6 cows. The Britwell part contained 100 a. of arable, 3 a. of pasture, and 10 a. of woods, supplemented by two yardlands given by a certain Sybil. (fn. 327)

Little is known about early cereal cultivation on the demesne, although 40 a. were sown with oats in 1211. (fn. 328) Crop accounts for 1365–6 show that 49 a. yielded 61 quarters of spring barley, 76 a. produced 48 quarters of peas, and 3 a. grew 4 quarters of oats, while crop sales raised £9, principally from barley, followed by wheat and oats. (fn. 329) Livestock in 1287 totalled 160 sheep, c.30 cattle (including a bull), 29 pigs (including a boar), and 11 horses (including a cart horse), together with a few poultry. (fn. 330) Sheep numbers increased to 250 at Newington and 300 at Britwell by c.1322, (fn. 331) and in 1367–8 some 136 fleeces were sold for £3. Four years later 91 fleeces were sold and sheepskins raised 2s. 6d., additional income coming from hay (£2) and leases of demesne pasture (12s. 9d.). (fn. 332)

Tenant farming was smaller-scale but similarly mixed, with an emphasis on sheep, corn, and pigs. (fn. 333) Most 13th-century villeins held a yardland (perhaps 24 a.) (fn. 334) for cash rents of 4–5s., hearthpenny (due on 1 August), and heavy labour services including ploughing, harrowing, sowing, hoeing, reaping, haymaking, carting, and shepherding. Other services included repairs to the lord's buildings, mill, and fish weir, carriage of timber and firewood from his Chiltern woods, and carting of grain to market within Oxfordshire. Several villeins undertook extra ploughing in return for commons in the demesne pasture (a service known as 'gerserthe'), and some received hay, sheaves, or sheep for boon works, for which the lord generally provided food and drink. Cottars owed similar but lighter services, and some paid part of their rent in hens or capons. (fn. 335)

Newington's open fields were administered by the late 13th century through a set of autumn by-laws, enforced in the manor court by a group of elected wardens. Offences were punishable by a fine, usually 2d.–12d. The first by-law restricted gleaning to those unable to reap, and set the rate of pay for reapers at a penny a day plus food. Others prohibited payment in sheaves in the field, carting by night, and trampling crops. Grazing by sheep was allowed after harvest, but only after grazing by plough beasts, and pigs were to be supervised by the common swineherds, one for each township. (fn. 336) Fines for excessive or improper grazing were regularly imposed. (fn. 337) Intercommoning existed between Newington and Warborough (fn. 338) and between Britwell Prior and Watlington, (fn. 339) while the bishop of Lincoln had specified meadow rights in Haywards mead. (fn. 340)

The Black Death led to vacant holdings on Newington manor, and in 1359 6½ yardlands in Britwell Prior (previously held by six tenants) were leased to one person until takers could be found. (fn. 341) Britwell rents remained low, with further engrossment of holdings, so that in 1489 one customary tenant there held nine yardlands (219 a.). (fn. 342) Shortage of tenants elsewhere on the manor was less acute, although the number of customary holdings roughly halved, and the average peasant farmed two yardlands instead of one. (fn. 343) Rents stabilized in the 15th century at 105. per yardland in Newington and Brookhampton and 9s. in Berrick Prior, significantly more than the 4–75. charged in Britwell Prior, (fn. 344) while labour services were routinely commuted to cash payments. (fn. 345) Entry fines were significantly lower than those demanded before 1349. (fn. 346)

Probably in response the priory withdrew from direct management c.1370, leasing the manor to one or more farmers who replaced the reeves. Their annual accounts survive intermittently from 1417, showing that they paid £26-£27 rent and regularly spent significant sums on repairs to both tenant and demesne buildings. (fn. 347) A lease of 1487 was issued jointly to three farmers resident in Newington, Britwell Prior, and Shirburn, for 15 years at £27 6s. 8d. rent. The prior provided them with money to stock the demesne (£7 15s. for Newington and £3 12s. for Britwell Prior), on condition that they returned those sums at the end of their term. (fn. 348) In 1490 the Newington and Britwell farmers held 296 a. and 123 a. respectively. (fn. 349)

Medieval agriculture in Holcombe is less well recorded. In contrast with Newington manor (but in common with others nearby), (fn. 350) most Holcombe tenants in 1279 were freeholders or cottars owing cash rents only. The single villein held ½ yardland, owing ploughing-service on Holcombe's half-hide (c.6o-a.) demesne. One free tenancy, comprising a hide, was probably the later Skirmots farm, named after its 15th-century owners; (fn. 351) in 1484 it was let for 13 years at £2 13s. 4d. rent, its outbuildings including a stable, sheephouse, garner, and barn. (fn. 352) Holcombe field-names attest the cultivation of flax, rye, and peas, (fn. 353) and an area known later as the Warren was presumably a rabbit farm. (fn. 354) Osney abbey's Newbury grange was sown c.1280 with seed-corn from Watlington, (fn. 355) and c.1503 was let to a Holcombe farmer for 21 years at £3 a year. (fn. 356)

FARMS AND FARMING 1500–1800

In the early 16th century Newington manor was still leased to local farmers, who after John King's death in 1505 (fn. 357) were principally members of the Hall family. Leases of c.1516 and 1533 (for 25 and 40 years respectively) were at the lower rent of £10, apparently because the priory had resumed control of tenant holdings leaving the farmers with only the demesne. (fn. 358) An Oxford wax chandler was appointed beadle in 1512, (fn. 359) and in 1519– 20 collected £27 rents for the prior: £10 from Berrick Prior, £6 from Newington, £6 from Brookhampton, and £5 from Britwell Prior and Minigrove. (fn. 360) Total manorial income was £33 9s. 7d. clear in 1535. (fn. 361)

Under new lords (the Oglethorpes) the value rose to £38 a year by 1579, (fn. 362) although the manor was reduced in 1600 by the loss of its Britwell Prior and Minigrove properties. (fn. 363) Thereafter little is known about its tenant farms, although several were copyholds let for three lives. (fn. 364) The more prosperous tenants included members of the Freeman, King, and Wise families at Berrick Prior, (fn. 365) and the Andersons of Brookhampton, of whom Thomas (d. c.1729) took the copyhold Brookhampton farm (then called Taylors) in 1692. (fn. 366) His son Thomas (d. 1741), who also farmed in Stadhampton, left goods worth the exceptional sum of £1,020, including £815 in crops and livestock. (fn. 367) In Newington, James Leaver (d. c.1722) held Ewe farm, (fn. 368) which by 1731 had passed to Elizabeth Tripp at £164 a year. (fn. 369) In 1795 the estates principal farms were Ewe (226 a., let to John Tripp), Lane End (100 a., also John Tripp), and Brookhampton (101 a., Thomas Anderson), along with three farms in Berrick Prior held by Jesse Leaver (106 a.), John Lee (104 a.), and Thomas Coles (64 a.). (fn. 370)

Farming in Britwell Prior was dominated initially by the Crook family as tenants under Newington manor, with sheep, barley, and wheat featuring prominently in the wills of Richard (d. c.1569) and his son Richard (d. 1580). (fn. 371) From 1600 the family held under Britwell Prior manor, John Crook (d. 1619) leaving goods worth £288, of which £133 was in grain and £75 in livestock (including 100 sheep). (fn. 372) The Crooks' Priory (or Upper) farm was leased later to the Rolles and Blackall families, (fn. 373) and in 1717 was held by Thomas King for £100 a year; a second farm (Lower or Coopers) was then let to Thomas Hutchins at £60. (fn. 374) From 1738 both farms (352 a. in 1795) were worked together by the Stopes family, (fn. 375) which bought the freehold in 1797. (fn. 376) The 70-a. Shambridge farm, so called by 1717, was apparently sold to its tenant Edward Goodchild in 1797, as part of Lower Greenfield farm in Watlington. (fn. 377)

Holcombes principal 16th-century farmers were members of the Bisley family, of whom John held leases of both the Newbury and Skirmots farms in the 1530s. (fn. 378) Later Holcombe tenants included Thomas King (d. 1731) (fn. 379) and probably Edmund Spyer (d. 1649), whose goods at his death (worth £449) included £285 in crops and £92 in livestock. (fn. 380) By the 1780s Holcombe had four farms, including three on the manor estate: Great Holcombe farm (169 a., let to Thomas Smith), Little Holcombe (228 a., John Blewett), and Hill farm (105 a., Richard Swell). Warren Hill farm (76 a.), held by Richard Butler, belonged to Great Milton's Ascott manor estate. (fn. 381)

Farming remained mixed with an arable bias. In 1795 three quarters of titheable land in the parish was under crop, and all but one farm had more arable than grass. (fn. 382) The main crops were barley, wheat, and pulses, with some oats and rye; (fn. 383) fodder crops were regularly grown on the fallow, (fn. 384) and apples and bees were mentioned occasionally, (fn. 385) while those with malting and brewing equipment included the Berrick Prior victualler John Weller (d. 1792). (fn. 386) Livestock included pigs and cows, with cheese-making particularly prevalent in Holcombe and Brookhampton, (fn. 387) although sheep remained most numerous, with flocks of 100 or more recorded frequently. (fn. 388) In 1647, when both sheep and cattle were admitted to Holcombe's fields after harvest, tenants could graze 20 sheep for every yardland held, and four people had between 2 and 14 cow commons. (fn. 389)

Inclosure increasingly threatened such common rights. In 1568 three Brookhampton copyholders accused John Oglethorpe of trying to inclose Haywards mead, where up to 200 sheep and 21 cattle could be pastured between Lammas and Mid-Lent Sunday along with plough beasts. (fn. 390) His attempt failed, but Oglethorpe's son Owen inclosed Newington's fields c.1595, and Holcombe was inclosed by 1795, leaving only Brookhampton, Berrick Prior, and Britwell Prior pursuing open-field farming. (fn. 391)

FARMS AND FARMING SINCE 1800

Berrick Prior was inclosed in 1815 under a private Act of 1810, promoted probably by Sir Cecil Bisshopp as lord of Newington. The same inclosure extinguished tithes in Berrick Prior and Newington, affecting c.1,100 a. (including old inclosures) in the two townships. Bisshopp received 806 a., the rector 204 a., and five landholders a total of 97 a., while 2 a. were allotted for Berrick Prior's poor in compensation for furze-cutting rights. The rector's allotment included a ring-fenced glebe farm of 182 a. in lieu of tithes (Lane End, formerly Bisshopp's), (fn. 392) which he farmed directly, stock at his death in 1830 including 207 sheep, 13 dairy cows, and quantities of wheat, oats, barley, and beans. (fn. 393) Bisshopp organized nearly all his land in just two farms, Ewe (467 a.) and Berrick (335 a.), (fn. 394) which in 1832 were tenanted together. (fn. 395) Around 1840 each gained a secondary 'field homestead', (fn. 396) and in 1856 the two farms were let to different tenants for £371 and £340 a year. (fn. 397)

Farms in Holcombe, Brookhampton, and Britwell Prior were described in 1839 and 1843. At Holcombe only 39 per cent of farmland was arable, compared with 63 per cent in Brookhampton and 76 per cent in Britwell Prior. The 100-a. Warren Hill farm was still held of Ascott manor, but otherwise all the townships farmland belonged to Holcombe manor and was let as three farms: Great Holcombe (205 a., run by Edward Shrubb), Little Holcombe (231 a., William Gardner), and Hill (116 a., Henry Hamp). Brookhampton farm (183 a.) was held of Newington manor by Thomas Smith, (fn. 398) while Britwell Priors Priory and Coopers farms included land in Britwell Salome, bringing their areas to c.480 a. and 280 a. respectively (fn. 399) The former had been owned and occupied since 1824 by Richard Newton, while the latter (recently bought by James Campion) was let to John Stopes. (fn. 400) At the Britwells' inclosure in 1842–5 Campion (200 a.) and Newton (188 a.) were the principal recipients, whilst James Weld received 85 a. at Shambridge woods, Edmund Painter 73 a. for part of Lower Greenfield farm, and W.F. Lowndes Stone 70 a. for Britwell Prior manor. The rector was allotted 15 a. for glebe, and 12 others shared a total of 58 acres. (fn. 401)

In 1856 Newington manor was broken up. (fn. 402) Ewe and Berrick farms (862 a.) (fn. 403) were bought by John Deane (d. 1886), who ran both from Ewe Farm until the early 1880s; (fn. 404) thereafter Berrick farm passed to the Franklin family, which retained it in 1999. (fn. 405) By 1861 Deane employed 50 men and boys, the parish's seven remaining farmers employing 68 labourers between them. (fn. 406) Farming in Britwell Prior was dominated from 1870 by James Prowse Franklin, a Ewelme man who leased the 480-a. Priory farm from the Paine family. (fn. 407) Franklin continued there until his death in 1908, (fn. 408) to be succeeded by H.W. Stride (d. 1919). (fn. 409) Cooper's, Great Holcombe, Ewe, and Berrick farms were then generally managed by bailiffs. (fn. 410)

Most 19th-century farmers still practised arable-based sheep-corn husbandry, and several employed shepherds, (fn. 411) while in 1861 John Turrill of Brookhampton farm was a butcher raising beef cattle. (fn. 412) As elsewhere, agricultural depression from the 1870s saw arable increasingly converted to grass, with 800 a. under permanent pasture by 1900 and a further 323 a. sown with clover or sanfoin. (fn. 413) Even pastoral farming was insecure, the tenant of Holcombe's Hill farm (a dairy operation employing two farmhands) going bankrupt in 1880, (fn. 414) while numbers of milch cows (excluding Britwell Prior) dropped from 106 in 1870 to 28 in 1890, recovering to 73 by 1900. Numbers of other cattle held firm at 162–70, and pig numbers increased from 37 to 96, but sheep numbers halved from 1,791 to 890, perhaps in part reflecting the decline in arable from 47 per cent of agricultural land to only 37 per cent. Barley, wheat, and oats remained the principal crops, with 60 a. of flax reported in Berrick Prior in 1870. (fn. 415) Small-scale watercress production was recorded in Berrick Prior and Britwell Prior c. 1877–92, exploiting natural springs. (fn. 416)

The earlier 20th century saw most of the parish's farms change ownership. Holcombe manor was broken up in 1911, and its three farms bought soon after by the families which ran them in 2014. (fn. 417) The Deanes sold Ewe farm by 1939, (fn. 418) and in 1941 two smallholdings at Warren Hill were leased from the county council, which had established them in the 1920s. Fairview farm (50 a., mainly pigs) was a sub-holding of Great Holcombe, and Alan Franklin of Berrick Farm let most of his 330 a. to a farmer from Rokemarsh in Benson. (fn. 419) Newell's farm at Brookhampton was established in the 1950s, (fn. 420) and in 1960 the parish's 11 farms (six of them over 100 a.) employed 19 people between them. A third of farmland was still arable, producing mostly wheat, barley, and oats, while livestock comprised 467 cattle (136 in milk), 105 pigs, and 50 sheep. Poultry numbered over 2,000, some of them kept on a holding run from a cottage between Holcombe and Brookhampton. (fn. 421)

The parish's largest enterprise was Priory farm in Britwell Prior, bought by Sidney Roadnight in 1920 and worked by his nephew Richard for over 40 years from 1936. (fn. 422) In 1941 it comprised 900 a. including Coopers farm and employed 16 people, (fn. 423) and by the 1950s covered 2,300 a. in several parishes, employing 28 men and 2 boys and using 15 tractors. Almost two thirds of the farm was arable, producing mostly barley and wheat which was stored and dried in a large brick granary near the farmhouse. The remaining third supported 350 cattle, 1,360 sheep, and 500 poultry, while 1,200 pigs were reared outdoors using pioneering methods. (fn. 424) By the mid 1980s some 4,600 tons of grain were produced annually, and there were 550 breeding sows, although the workforce had shrunk to 18. (fn. 425) The farm was broken up and sold in 1992, and thereafter much of the land was farmed from Brightwell Baldwin. (fn. 426)

During the later 20th century arable across the parish was expanded, accounting for almost three quarters of farmland by 1988. New crops such as oil seed rape and maize underlay some of the expansion, although wheat, barley, and oats still predominated. Hill farm specialized in dairy production, converting later to mixed farming with a beef herd. (fn. 427) Sheep were reared on Berrick farm in 1999, (fn. 428) and from 2006 a restaurant and hotel business in Brookhampton bred Gloucestershire Old Spot pigs on Newell's farm (80 a.), which by 2014 supported various rare breeds and a farm shop. (fn. 429) Ewe and Lane End farms were then mainly arable, and Great Holcombe farm had 450 pedigree Aberdeen Angus beef cattle. (fn. 430)

TRADES, CRAFTS, AND RETAILING

Medieval occupational surnames included Butcher, Carpenter, Chapman, Miller, Tailor, Chandler, Coopator (roofer), Sutor (cobbler), and Webbe (weaver). (fn. 431) Andrew de Furno ('of the oven or furnace'), recorded at Britwell Prior in 1279, was perhaps a baker or blacksmith, (fn. 432) and in 1326 Henry the baker of Newington was fined for obtaining corn sheaves in breach of the autumn by-laws. (fn. 433) Several other tenants of Newington manor (often women) paid brewing fines known as 'tolcester', charged at 1½d. for every 1½ gallons of ale brewed or sold. Around 20 people regularly paid 4–6d. each in the 1280s, (fn. 434) and in 1320 a Britwell Prior woman was described as a taverner. (fn. 435) Inhabitants surnamed Smith were recorded in four of the five townships in the 13th century, (fn. 436) and a blacksmith paying 18d. rent continued in Newington in 1366, when a reeve allowed him iron and steel for plough repairs. (fn. 437) Excavation south of Newington House revealed a 12th-century smithy replaced with a new forge in the 13th century, but decommissioned in the 14th. (fn. 438) Thereafter no further record of smithing has been found until the 19th century. Gravel has been dug from pits in Berrick Prior and Holcombe since the Middle Ages. (fn. 439)

Holcombe inhabitants (as tenants of ancient demesne) had their ancient freedoms from tolls and other dues throughout England reconfirmed in 1588. (fn. 440) Trades there in the 16th–18th centuries included those of butcher, joiner, cordwainer, shoemaker, tailor, thatcher, and wheelwright, (fn. 441) while a Britwell Prior clothworker in 1644 had a well-equipped workshop containing three pairs of fulling shears, (fn. 442) and a Newington man in 1630 left looms worth £2. (fn. 443) Pubs in Berrick Prior and Brookhampton (known by 1822 as the Chequers and the Bear and Ragged Staff) were licensed by 1754. John Weller, the former's publican from 1763, worked also as a thatcher, and by the 1790s ran a grocer's shop from the premises. In 1773 he purchased the pub's freehold, and ten years later added a granary which he left to his son, (fn. 444) a dealer trading in Berrick Prior and Roke. (fn. 445) Aylmor Stopes of Britwell Prior and London was a mid 18th-century clockmaker. (fn. 446)

In 1831 only 23 people from 7 families (18 per cent of those in work) were employed in retail and crafts, with most businesses concentrated in Brookhampton or Holcombe, where there was passing trade from the turnpike road. (fn. 447) Brookhampton in particular saw the greatest amount of commercial activity during the 19th and 20th centuries, the Bear and Ragged Staff pub remaining open in 2014 following its relaunch as a hotel and restaurant in 1993. (fn. 448) A second pub or beer shop called the Wheatsheaf opened there before 1838, when Brookhampton had a bakery, a corn merchant's granary, and a butcher's slaughterhouse, (fn. 449) and by the 1850s there was a grocer's and wheelwright's. (fn. 450) The Wheatsheaf was apparently demolished c.1860, (fn. 451) but later 19th-century tradesmen included two bakers, two grocers, and a butcher, and c.1880 a cottage-based clothing factory run by a tailor employed a few local women as machinists and pressers, closing by 1901. (fn. 452) A grocer's shop and a bakery continued into the 20th century, the shop accommodating a post office by 1881. It was rebuilt following a fire in 1960, and in 2014 was a post office, general store, and petrol station. (fn. 453)

Holcombe had a beer shop by 1838, (fn. 454) and in 1841 a tailor and shoemaker each employed apprentices. (fn. 455) A grocer's shop on the turnpike road traded from the mid 19th century (fn. 456) to the early 1940s, when it passed to a local builder who erected several houses in the parish, (fn. 457) while a pub opposite (called the Stag) traded from the 1850s until 1967. (fn. 458) Members of the Ring family were carpenters in the late 19th century, (fn. 459) and a joiner was resident in 1999. (fn. 460) A horticultural nursery between Holcombe and Brookhampton opened in the 1990s. (fn. 461) At Berrick Prior the Chequers continued as a pub and grocer's shop into the 20th century, gaining a 'refreshment room' in the 1920s and a post office by the 1960s. (fn. 462) The shop and post office closed in the 1980s, (fn. 463) but the pub continued in 2014. A smithy on the Berrick–Newington road, established by 1871, continued as a carpenter's and wheelwright's shop until the early 20th century. (fn. 464)

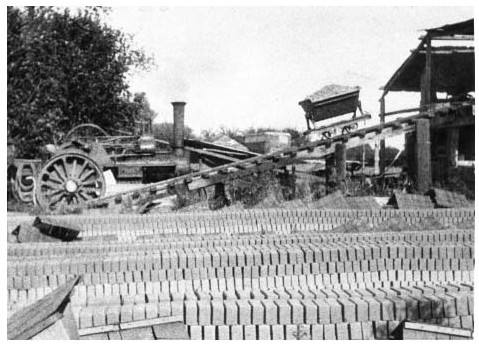

A small brick and tile works established by the farmer John Deane employed one man in 1861, but apparently closed soon afterwards. (fn. 465) A longer-lasting enterprise was started by the Franklins at Lonesome Farm in 1927, employing 3–5 men in the 1930s when it produced 30,000–74,000 bricks a year, sold to builders in Wallingford, Henley, and Benson. In 1947 (following temporary wartime closure) it was revived as the Chalgrove Brick Co., and at its height in 1949 employed twelve men and sold 349,000 bricks, including some to a London building firm. Thereafter production fell sharply, and the works closed in 1954. The kiln and some other infrastructure survived in 1980. (fn. 466)

MILLING AND FISHING