A History of the County of Gloucester: Volume 12. Originally published by Boydell & Brewer for Victoria County History, Woodbridge, 2010.

This free content was digitised by double rekeying. All rights reserved.

'Preston', in A History of the County of Gloucester: Volume 12, ed. A.R.J. Jurica (Woodbridge, 2010), British History Online https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/vch/glos/vol12/301-317 [accessed 7 February 2025].

'Preston', in A History of the County of Gloucester: Volume 12. Edited by A.R.J. Jurica (Woodbridge, 2010), British History Online, accessed February 7, 2025, https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/vch/glos/vol12/301-317.

"Preston". A History of the County of Gloucester: Volume 12. Ed. A.R.J. Jurica (Woodbridge, 2010), British History Online. Web. 7 February 2025. https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/vch/glos/vol12/301-317.

In this section

PRESTON

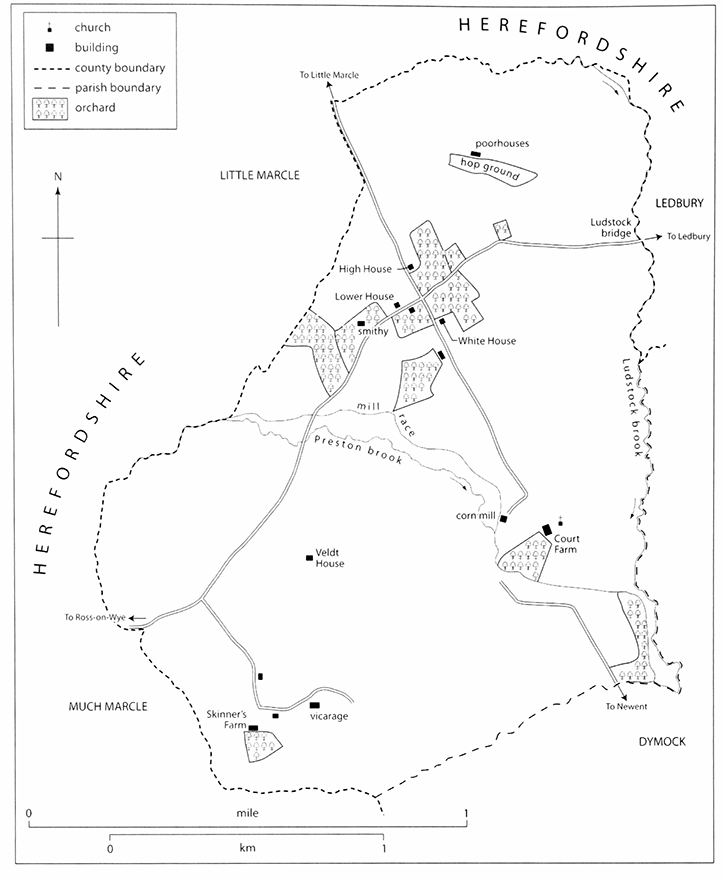

PRESTON, situated 22 km north-west of Gloucester and 5 km south-west of the Herefordshire town of Ledbury, covered 897 a. (fn. 1) and was one of Gloucestershire's smallest rural parishes. It lay at the end of a wide salient of the county jutting northwestwards into Herefordshire. Its ownership by Gloucester abbey, from which it took its name, meaning the priests' settlement, by the late AngloSaxon period, (fn. 2) accounted for its inclusion in the hundred of Longbridge (later part of Dudstone and King's Barton). (fn. 3) As a civil parish Preston was absorbed in 1935 by Dymock, its much larger neighbour to the south-east. (fn. 4)

Map 14. Preston 1834

LANDSCAPE

Save on the west Preston is bounded by streams, (fn. 5) that on the east being the Ludstock brook. (fn. 6) In the north the very end of the western boundary is a straight road leading into Herefordshire on the line of a Roman route by way of Dymock. (fn. 7) The land is generally flat lying at between 40 and 50 m and rising gently in the north and the south-west to over 60 m. The highest point, at 68 m, is in the south-west where the fields on much of the hill were known as the Castle Grounds in the late 18th century. (fn. 8) Most of the parish drains towards the Preston brook flowing across the centre of the parish from north-west to south-east. In the east the Ludstock brook, its principal tributary, was diverted a few hundred metres short of their confluence long before 1790. (fn. 9)

The land is on the Old Red Sandstone with alluvial deposits on the banks of the Preston brook and its tributaries. (fn. 10) The soil is mostly a deep heavy loam suited to arable farming and the land bordering the banks of the Preston brook and its tributaries is made up of meadows and pastures. (fn. 11) The parish contains no woodland (fn. 12) but the manor court dealt with the unauthorized felling of oak and other trees in the late 13th century (fn. 13) and pannage was among payments owed by medieval tenants. (fn. 14) The extent and number of Preston's medieval open fields are not known. Their inclosure was a long process partly determined by the local practice, adopted by the 16th century, of planting orchards in arable land. (fn. 15) Most of Preston's orchards in the mid 17th century were next to farmhouses. Inclosure was completed essentially in the later 18th century and scattered orcharding, although reduced in area in the later 20th century, has remained a feature of the landscape. (fn. 16) In the late 20th century a private air strip was created in a field west of the main road to Dymock in the south of Preston. (fn. 17)

ROADS AND BRIDGES

The main road between Ledbury and Ross-on-Wye (Herefs.) enters the north of Preston from the east at Ludstock bridge and runs westwards to crossroads at Preston Cross and from there continues southwestwards to cross the Preston brook. The road, which probably follows the course of a highway mentioned in the early 16th century, (fn. 18) was a turnpike road from 1722 to 1871. (fn. 19) Ludstock bridge, first mentioned in 1500, (fn. 20) was in considerable disrepair in 1824. (fn. 21) Regarded as a county bridge, it was widened in 1839 (fn. 22) and it was rebuilt, in brick, in 1897. (fn. 23) The junction at Preston Cross was made a roundabout in 1996 and just beyond it the Ross road was diverted slightly to the south. (fn. 24)

In the early 19th century the turnpike road was the only good road in the parish, the other routes being almost impassable in the winter. (fn. 25) From Preston Cross a road or lane ran southwards to the parish church and Preston Court and another ran northwards into Little Marcle (Herefs.), (fn. 26) both roads observing the line of the Roman route mentioned above. The church and Court stood together at the centre of a network of minor lanes or tracks, (fn. 27) some of which were presumably carried over ditches by bridges mentioned in the early 16th century. (fn. 28) About 1835 the lane leading northwards to Preston Cross and Little Marcle was incorporated in a new road constructed as part of a route from Newent to Leominster (Herefs.) by way of Dymock. (fn. 29) The new road, entering Preston from the south, (fn. 30) was a turnpike until 1871. (fn. 31)

POPULATION

In 1086 there were at least twelve tenant households in Preston (fn. 32) and in 1327 eight persons were assessed for tax there. (fn. 33) In 1539 a muster named 11 men in Preston (fn. 34) and in 1563 the parish contained 13 households. (fn. 35) The number of communicants was given as c.60 in 1551 (fn. 36) and 48 in 1603. (fn. 37) Preston's population was estimated at 60 c.1710 (fn. 38) and at 40 c.1775. (fn. 39) The latter figure may have been an underestimate, for in 1801 the recorded population was 87. In the 19th and 20th centuries the population was usually smaller and in 1881 it was as low as 61. In 1931, at the last national census to treat Preston separately, it was 77. (fn. 40) Preston's population fell even lower in the mid 20th century for in 1953 it was said to be 54 (fn. 41) and in 1972 it was 53. (fn. 42)

SETTLEMENT

Preston has few houses. Several form a small hamlet around the crossroads at Preston Cross and the rest are scattered through the parish. Personal surnames in the late 13th and early 14th century, including 'on the hill', indicate the antiquity of some of the inhabited sites. (fn. 43) In the mid 17th century there were apparently just over 20 houses in the parish (fn. 44) but by the early 19th century several farmsteads had been long abandoned (fn. 45) and in 1801 the parish contained 16 houses. (fn. 46) Despite further demolitions, new building in the later 19th century increased the number of houses to 18 in 1901. (fn. 47) There were 14 houses in 1953 (fn. 48) and 23 dwellings in 2000. (fn. 49)

Preston's medieval church stands on the east side of the parish behind Preston Court, an imposing timber-framed house built on the site of the manor in the late 16th or early 17th century. (fn. 50) The cluster of buildings at Preston Cross was made up of farmsteads. White House Farm and High House, east of the Dymock and Leominster roads respectively, were named in 1779. (fn. 51) Outbuildings north of the Ross road mark the site of Lower House, (fn. 52) where the farmhouse was demolished in the mid 19th century. (fn. 53) In the early 19th century there were two other farmhouses at Preston Cross. One, once part of an estate called Hooper's, was by the lane to Preston Court and was occupied as two cottages. The other, formerly part of an estate called Roper's, was on the Ross road and was used as a blacksmith's house and workshop. (fn. 54) Across the fields north-east of Preston Cross were two relatively new cottages built by the parish. (fn. 55)

On the west side of the parish the Veldt House (formerly Felt or Velt House) (fn. 56) stands south of the Ross road on a site where parishioners surnamed 'at' or 'in the field' in the late 13th and early 14th century may have lived. (fn. 57) Once there were also several houses and cottages further south some distance off the Ross road. In the early 19th century they included a farmhouse and two small cottages and a barn near by, in Upper Castle Ground, marked the site of an abandoned farmstead. (fn. 58) The farmhouse, known in 1780 as Green House, (fn. 59) was later called Skinner's, (fn. 60) after the family having the farm in the 18th century. (fn. 61) One cottage, north of the farmhouse, had the name Old Wytch in the mid 19th century. (fn. 62) The farmhouse, its outbuildings, and the cottages were all demolished in the late 19th century, apart from a barn (fn. 63) that remained standing until the late 20th century. (fn. 64) The Parsonage, to the east, began as a small house or cottage that was enlarged in the 1830s when it served as the vicarage house. (fn. 65) In the late 20th century it was restored and a private drive running northwards to the Ross road was created. (fn. 66)

Preston Priory, on the Leominster road northwest of Preston Court, was built as the vicarage house in 1864. (fn. 67) At that time the parish was short of cottage accommodation, two of its eight cottages having been built by squatters. (fn. 68) At the end of the century four new pairs of estate cottages were built, one at Preston Cross on the Ledbury road, another in the west on the Ross road, and two in the south on the Dymock road, and the two cottages just south of Preston Cross were rebuilt, all in the same style. (fn. 69) A new house was built at Preston Cross in 1960 and the old smithy on the Ross road was pulled down a few years later to be replaced by an engineering workshop. (fn. 70) Apart from a pair of cottages lower down to the west few other entirely new houses have been built in Preston.

BUILDINGS

Apart from Preston Court (fn. 71) three early farmhouses survive. In the early 19th century farm buildings on the estate were generally deemed to be in a poor or indifferent condition (fn. 72) and later all three farmhouses were improved and supplemented with extensive red brick outbuildings. Some of the new building presumably formed part of the programme providing new estate cottages at the end of the century. (fn. 73) High House, the oldest and most elaborate of the three farmhouses, incorporates a late 16thcentury two-storeyed cross wing from an L or H plan. The frame has close studding and in the main rooms intersecting beams. The hall was replaced, probably soon after 1803, (fn. 74) by a tall three-storeyed block, one room deep with a shallow external stack and a lean-to dairy. White House Farm, a later 17thcentury house on an L plan, has been subjected to a remodelling similar to that of Preston Court. One gable end was rebuilt in brick with segment-headed sashes and the main front was rendered in work, illustrated on a painting of 1843 in the house, that may have been finished by 1779 when the term White House was used. (fn. 75) The Veldt House was a smaller 17th-century dwelling of 2½ storeys with square-panel framing and a two-room plan with central stack and through passage. The house, occupied by a farm labourer in 1803, (fn. 76) was extended by two bays later in the 19th century and was much remodelled, using some old timbers, in the late 20th century when it was turned into offices. (fn. 77) The hipped roof at one end has been extended to link to what may have been the mill and granary mentioned in 1803. (fn. 78) The houses at Lower House and Skinner's, both demolished in the 19th century, (fn. 79) were recorded in 1803 as small dwellings, at least partly timberframed and thatched and with three rooms on a floor. (fn. 80)

At White House Farm a substantial timber-framed barn contemporary with the house survives. Of three bays and three panels high, it has some woven wattle infill. (fn. 81) At High House timbers from a five-bayed barn (fn. 82) were re-used in a 19th-century barn, which is probably contemporary with five large animal shelters there. At the Veldt House a five-bayed barn (fn. 83) was replaced by a new courtyard of buildings, which were converted as six dwellings at the end of the 20th century. (fn. 84) A small timber-framed barn is among buildings surviving at the site of Lower House.

MANOR AND ESTATES

Although Preston's only manor remained an ecclesiastical possession until the mid 20th century, it was in lay hands from the later 16th to the mid 19th century by virtue of leases to a lord farmer. Copyhold estates made up a good part of the manor (fn. 85) but by the mid 18th century some had been combined and the lord farmer had taken others in hand. (fn. 86) Most of the rest came in hand later on the expiry of their terms (fn. 87) and the last surviving copyhold, White House farm owned by the Elton family of Much Marcle (Herefs.), (fn. 88) lapsed soon after 1803. (fn. 89) The manor estate was broken up by sales in the mid 20th century and there were two main landowners in Preston at the turn of the century.

PRESTON MANOR

Gloucester abbey evidently acquired the manor before the Norman Conquest. It formed an estate of two hides in 1086 (fn. 90) and remained the abbey's property until the Dissolution. (fn. 91) In 1541 it was included in the endowment of the new bishopric of Gloucester. (fn. 92)

In 1583 the bishop granted the Crown a lease of the manor subject to an interest in it of the Powell family. (fn. 93) Thomas Powell had lived in Preston in the mid 1570s (fn. 94) and his son John had acquired a turn in the patronage of Preston church in 1576. (fn. 95) In 1585 the queen granted her interest to Fulke Greville and the following year he relinquished it to John Powell, who became his agent as secretary to the council of the Welsh marches. (fn. 96) John, described in 1587 as of Cheltenham, (fn. 97) resided at Preston by 1604 (fn. 98) and remained lord farmer of the manor until his death in 1632. (fn. 99) Anne Robins, the widow of Thomas Rich (d. 1607) and of Henry Robins (d. 1613), both of Gloucester, (fn. 100) acquired a lease of the manor probably by 1639 (fn. 101) and she retained the estate despite being listed in 1648 as a royalist sympathizer. (fn. 102) At her death in 1659 she left the manor to her grandson Henry Clements (fn. 103) and for a few years following the Restoration John Clements paid the rent owed by the lessee. (fn. 104) Henry Clements, who lived in Epsom (Surrey), died in 1696 leaving the manor to Anne Pauncefoot, (fn. 105) the widow of William Pauncefoot (d. 1691) of Carswalls, in Newent. (fn. 106) After Anne's death in 1715 (fn. 107) it passed to Sarah, the daughter of her son William Pauncefoot (d. 1711), and she married William Bromley of Worcester, later of Abberley (Worcs.). By that time the manor was held under the bishop for a term of three lives, the lease being renewed periodically with a variation in the named lives, and for the same rent as earlier. (fn. 108) The bishop's income came from the renewal fine, calculated at 1¾ year's valuation. (fn. 109)

William Bromley died in 1769 and his son and heir Robert (d. 1803) was succeeded in the manor by Sir George Bromley Bt, the owner of Carswalls in Newent. Sir George, who became known as Sir George Pauncefote after that inheritance, (fn. 110) died in 1808 (fn. 111) and left the manor for life to his companion Elizabeth Lester, known as Mrs Edwards. (fn. 112) She married Thomas Rickards (fn. 113) (d. 1832) (fn. 114) and at her death, by 1834, the manor reverted to Sir George's cousin Robert Pauncefote (formerly Smith) of Swansea. (fn. 115) Robert (d. 1843) was succeeded by his son Robert Pauncefote (d. 1847), and he by his brother Bernard. In 1855 Bernard, who lived in India, conveyed his estate to his brother Julian in order to relinquish it to the bishop, but the death of the bishop delayed the transaction until 1857, by which time the Ecclesiastical Commissioners had taken over the bishop's estate. (fn. 116)

The Ecclesiastical Commissioners included Preston in the estates given back to the bishopric on its re-endowment in 1867 (fn. 117) but they regained the Preston estate later in the century. (fn. 118) In the early 1950s their successors, the Church Commissioners, broke up the estate, selling its four farms to their tenants, and in the early 1970s the principal landowners in Preston were John Rhys Thomas of Preston Court and Michael Thomas of White House Farm. (fn. 119) While Rhys Thomas's land was sold after his death in 1982, Michael Thomas's land was retained by his family in 2004. (fn. 120)

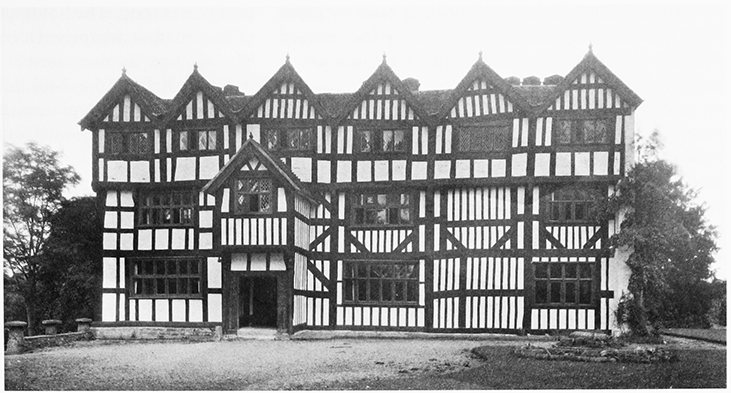

Preston Court

Preston Court stands next to the parish church on the site of the manor, an earth platform (fn. 121) on which a house known as 'the parlour' (le parlure) was rebuilt c.1501. (fn. 122) The Court is a large three-storeyed timberframed house which, although its north end is separately framed in the manner of a cross wing, appears to have been built in a single phase by John Powell in the late 16th or early 17th century. In its U plan with the wings to the rear and its display of close studding and decorative gables it follows local patterns. (fn. 123) The façade design with a jettied second floor and row of six gables is related to urban buildings in the region as well as to some Herefordshire country houses. The central two bays accommodate a hall and screens passage entered by a two-storeyed porch. The wings extend eastwards and a newel stair fills a north-eastern projection axial with the screens passage. The south wing, built over a cellar, has two parlours, the main one panelled and with an original overmantel. The north wing has two service rooms. On the west front the service wing and the four bays of the hall and high end are distinguished by different styles of framing: the former has large square panels, the latter close studding and downward braces. The north front of the north wing has close studding below square panels. The three brick stacks have diamond-set chimneys, two clusters of three at the high end and a cluster of six on the north wing, which together correspond to the 12 hearths recorded in 1672. (fn. 124)

69. Preston Court: the west front in 1945

In the early 18th century the south front of the south wing was faced in brick and given moulded stringcourses, segment-headed window surrounds, and a classical doorcase. The south windows have been altered and in the 1930s rendering added to the main front and a sash window inserted in the west end of the south wing, perhaps also in the 18th century, were removed. (fn. 125) The centre of the north front was made to look Georgian after 1982. (fn. 126)

Extensive outbuildings stand north-east of the house. They include timber-framed stables, a partly rebuilt cider house, and further east a courtyard of 19th-century red brick farm buildings wrapped around an older stone barn.

ECONOMIC HISTORY

The economy of the small parish was devoted to meeting the immediate farming needs of its inhabitants. More specialist services were obtained elsewhere.

AGRICULTURE

The Middle Ages

In 1086 there were ten ploughteams in Preston, two belonging to Gloucester abbey's demesne, which employed 4 slaves, and the others to the abbey's tenants, who were 8 villans and 4 bordars. (fn. 127) In the mid 13th century the abbey's tenants owed 66s. 2½d. in rent and 36s. 10½d. in aid and their services were valued at 8s. (fn. 128) The abbey granted one customary tenant, a carter, 23 a. arable and ½ a. meadow for a cash rent of 8s., the service of a man performing three bedrips, i.e. reaping services, and customary payments including pannage. (fn. 129) In the early 1290s there was a collective duty to mow the abbey's meadow in Gloucester and a woman was presented in the manor court for not repairing the abbey's nets. At that time several tenants were in arrears with their services and several as well as the carter kept cattle. (fn. 130) Tenant holdings included yardlands, one of which was held for a rent of 14s. 2½d., (fn. 131) half-yardlands, and quarter-yardlands. A yardland contained 48 a. In 1351 a dozen holdings, among them several mondaylands, were in hand and a few tenants held some of their land by grant from the abbey. Earlier in 1351 the abbey had granted Richard of Ledbury, archdeacon of Gloucester, a yardland for nine years at a cash rent and the custody of another holding during the minority of the tenant. (fn. 132)

Most land in Preston was used for arable farming in the Middle Ages. (fn. 133) What little meadow land and pasture there was adjoined the Preston brook and its tributaries. In the later 13th century Gloucester abbey's demesne included land in open arable fields and in meadows called South Mead and Pond Mead. (fn. 134) At that time parts of Preston were cultivated in closes and the abbey, which included oats among its crops, had meadow land and pasture in severalty. (fn. 135) There were several open fields. In 1351 a holding of 4 a. was divided between the south field and another place (fn. 136) and in 1512 the tenants were ordered to close the fields sown with corn before All Saints and the other fields before Candlemas. (fn. 137) There was common pasture in the parish (fn. 138) and in 1515 a tenant was presented for overburdening it. In 1518 Thomas Hankins and fellow tenants agreed that he might hold a pasture called Hales Meadow in severalty every third year. (fn. 139)

The demesne, which covered c.250 a. according to later measurements, (fn. 140) was leased with other land in severalty to John Sibles and his sons in 1501 for a rent of 27 quarters of wheat to the abbey cellarer and of 20 each of geese, ducks, capons, and pullets and 44 measures of green pulse to the abbey kitchener. Among the land leased with the demesne were four meadows and pastures, of which Broad Bridge (fn. 141) was next to the site of the manor by the Ludstock and Preston brooks. (fn. 142) The maintenance of ditches to ensure effective drainage of the land was a major concern of the manor court during the period. (fn. 143) In 1535 Richard Sibles's rent, still in kind, was worth £8 3s. 11d. and those of the abbey's other tenants, free and customary, were valued at £13 3s. 7½d. (fn. 144)

In the late Middle Ages there were fewer tenants than earlier and in the early 16th century a dozen paid pannage. Some copyholds had been amalgamated and one tenant held demesne land in the open fields called Brink field and Clan field as part of her farm. The holdings varied in size and one of the smallest comprised a cottage and a few acres. (fn. 145) The decline in the number of small copyholders continued after the Middle Ages and was in all likelihood related to piecemeal inclosure of the open fields, which became small and scattered. (fn. 146)

The Early Modern Period

In the early 17th century John Powell employed four farmers on the demesne and another three men had sizeable farms in the parish. (fn. 147) The demesne remained in hand in the mid 17th century, when it was surveyed as 145 a. and most of the other land was copyhold granted by the lord farmer. Of eleven copyholds recorded in 1647, nine ranged in size from 9 to 68 a. and the others comprised a cottage and a little land. The largest holdings or farms, including four with c.52 a. each and one with 68 a., had probably been created by the amalgamation of smaller units for they each had more than one messuage, one as many as four. The tenants retained the customary rights of ploughbote, hedgebote, and firebote. (fn. 148)

The parish remained predominantly arable with the demesne made up of 120 a. arable, 10 a. meadow, and 15 a. pasture in 1647. Most of the demesne arable was in four places, principally Church field and Great field, and the tenants' arable included pieces of various sizes in the remnants of the medieval open fields, including Brink field in the west, Clan field in the north-east, and Link field in the north. Piecemeal consolidation and inclosure of holdings in openfield land was far from complete; several of the pieces were surveyed as ½ a. Among the many small fields and closes in Preston in the mid 17th century was one called Pease Croft. (fn. 149) The local practice of planting orchards in the fields (fn. 150) presumably began in Preston before the later 16th century; in 1578 a Preston widow left cider as part of her property. (fn. 151) In the mid 17th century one tenant had three orchards next to his house and a cider house among his outbuildings. (fn. 152)

Further reorganizations of tenant holdings took place and in the mid 18th century some copyhold land was farmed with the demesne from Preston Court. (fn. 153) In the later 18th century, when he allowed copyhold tenure to lapse and replaced it with leasehold tenure, the lord farmer added more land to Preston Court farm. (fn. 154) The last remaining copyhold lapsed in the early 19th century. (fn. 155) The tenant farms continued to be reorganized and their number was gradually reduced. (fn. 156) In 1803 Preston Court farm had increased in area to 495 a. and the other four farms comprised 116 a. (High House), 87 a. (White House), 77 a. (Lower House), and 50 a. (Skinner's). A bailiff managed White House farm for Samuel Cooper of Ledbury. (fn. 157)

The inclosure of the open fields continued as land was exchanged between the various farms and was virtually complete by the end of the 18th century; in 1803 only one farm was made up of scattered pieces. The land was best suited to growing wheat and beans (fn. 158) and over half of the 220 a. recorded as being under crops in 1801 was devoted to wheat and the rest comprised small areas of barley and oats, 53 a. of peas and beans, and 11 a. of turnips. (fn. 159) With meadow land of middling quality and poor pasturage, in 1803 pastures called Cow Leaze and Lower Cowleaze on White House farm had not long been converted to arable. The livestock at that time presumably included several dairy herds. The outbuildings of Preston Court farm included a cheese chamber and cattle sheds as well as pig sties and several other farms also had cow sheds. (fn. 160)

Although there were many orchards, each farm usually containing one or more next to the farmhouse, by the beginning of the 19th century some had been grubbed up and others were old and in decline. There were few new orchards at that time. Some of the best were at Preston Cross. Although some pear trees had been planted, most farms made cider for local consumption. (fn. 161) Hops were also grown in Preston and in the early 19th century there were two hop gardens, one of them old, in the north and another old one near Preston Court. (fn. 162)

The Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries

Farm reorganization continued in the early 19th century. By 1824 the entire northern end of the parish beyond the Ledbury–Ross road was farmed from High House (fn. 163) and in 1834 Preston Court farm contained 322 a. and the rest of the farmland (apart from the glebe) was divided between farms centred on High House (208 a.), the Veldt House (109 a.), Skinner's (94 a.) and White House Farm (76 a.). (fn. 164) Veldt House and Skinner's farms, making up the western side of the parish, were amalgamated before 1842 (fn. 165) and Preston's four farmers worked 322 a., 200 a., 190 a., and 110 a. and employed a total of 22 labourers in 1851. (fn. 166) The four farms remained much the same size in the later 19th century. (fn. 167)

In 1842 the parish contained 368 a. of arable and 482 a. of meadow and pasture. (fn. 168) In 1866, when the crop rotation included some clover or grass, cereals, particularly wheat, remained the main crop but there was as much permanent pasture as there was arable. (fn. 169) Each farm had a resident dairy maid in 1861 (fn. 170) and among the livestock returned in 1866 were 117 cattle, including 56 milch cows, 164 sheep, and 49 pigs. (fn. 171) In the late 19th century cereal production declined and in 1896, when at least 34 a. was fallow, livestock in the parish included 196 cattle, among them 37 milch cows, and 158 ewes and 67 pigs. (fn. 172) Cattle farming continued to grow in importance in the early 20th century, and in 1926, when permanent grassland accounted for 506 a. and cereal production for 212 a., 243 cattle, including 64 milch cows, were returned. The numbers of ewes and pigs had fallen to 61 and 15 respectively. (fn. 173) During that period the area of orchards (27 a.) was little changed but blackcurrant bushes were planted in a few of their acres. The agricultural workforce in 1926 included 12 labourers employed full time. (fn. 174)

For a period beginning in the mid 1920s the number of farms was reduced to three (fn. 175) but after the Second World War Preston's farmland was again cultivated in four units. Farming was mixed and in 1951 two farms specialized in dairying and the others raised beef cattle. Sheep and pigs were also reared on two farms. Some land was used as grass leys and the arable crops included potatoes as well as cereals. Mushrooms were cultivated in some places. (fn. 176) By 1972 Preston was divided into two large farms. (fn. 177) The parish retained many of its orchards in the mid 20th century (fn. 178) but most had been grubbed up by the beginning of the 21st century. A new orchard was planted by the Ross road, in front of the Veldt House, in the later 20th century.

MILLS

There was a water mill in Preston by the mid 13th century. (fn. 179) Roger the millward lived in the parish in 1327 (fn. 180) and Gloucester abbey granted a water mill to a man from Redmarley D'Abitot for a term of 60 years in 1351. (fn. 181) In 1511 and 1512 a miller was presented in the manor court for taking excess toll. (fn. 182)

Two places in Preston have been associated with water mills. One, on the Preston brook west of Preston Court, was possibly the site of a little mill held with the house in 1647. (fn. 183) The mill there stood at the end of a long leat (fn. 184) and was leased as part of Preston Court farm in the late 18th century. It usually operated as a corn mill, (fn. 185) although in 1832 it was described as a grist or clover mill, (fn. 186) and in 1803 it was housed in a small timber and boarded building and was powered by an overshot wheel. (fn. 187) Replaced by a brick and weather-boarded building, it was abandoned in the early 20th century and the empty mill pond was used as a chicken run in 1951. The building was demolished after 1966 (fn. 188) and the site was entirely overgrown in 2002.

The other mill stood on the Preston brook in the south-eastern corner of the parish where the Ludstock brook was diverted to increase the flow of the Preston stream. (fn. 189) It was held by the Cam family and the fields on either side of the Preston brook became known as Cam's Mill Orchard and Cam's Mill Meadow. (fn. 190) In 1515, following William Cam's failure to repair it, the mill was declared ruinous. (fn. 191) It was presumably never rebuilt and in 1647 John Cam held land adjoining an old mill. (fn. 192)

TRADES AND SERVICES

Among residents of Preston in the early 14th century was a female dressmaker (shipster). (fn. 193)

Although trades allied to farming have provided employment in Preston evidence for them is almost entirely lacking. An abandoned kiln at High House in 1803 (fn. 194) had possibly been used solely for the purposes of the farm. In the early 19th century, when a blacksmith and a wheelright lived and worked in Preston, (fn. 195) four of the parish's fourteen families were supported by trade or crafts. (fn. 196) A carpenter named in 1815 (fn. 197) remained in business in the mid 19th century and Preston's residents in 1851 also included a drainer and a dressmaker. (fn. 198) One parishioner worked as a sawyer in 1833 and 1841. (fn. 199) The smithy, on the north side of the Ross road at Preston Cross, continued to operate into the 20th century (fn. 200) and its site was occupied by a small engineering firm servicing and selling agricultural machinery in 2002.

Velcourt, a land management company originally founded by John Rhys Thomas at Preston Court, moved to the Veldt House in 1982 and employed ten people there, seven of them full time, in 2004. (fn. 201) An antiques business established at Preston Court in 1983 continued in 2004. (fn. 202)

Preston has never had a post office and no evidence of a shop has been found. (fn. 203)

LOCAL GOVERNMENT

MANORIAL GOVERNMENT

Gloucester abbey held a manor court for Preston. (fn. 204) In addition to tenurial and agrarian business, in the early 16th century it enforced the assize of ale, supervised the maintenance of roads, streams, and ditches and dealt with stray animals. It also regularly heard pleas of assault and affray and on a few occasions it elected a constable. In 1505 the abbey's tenants were ordered to seek justice only in the manor court and through the abbot, a member of his council, or the manorial bailiff. (fn. 205) Members of the Sibles family, as lessees of the site of the manor and demesne, were required to provide hospitality for the abbey cellarer and steward when they came to Preston to hold the court. (fn. 206)

In the early modern period the court belonged to the lord farmer of the manor (fn. 207) and, as indicated in a lease of 1793, the main parlour of Preston Court was its traditional meeting place. (fn. 208) No records of the court survive from the period; its work as a court baron would have largely ceased with the final extinction of copyhold tenure in the early 19th century. (fn. 209)

PAROCHIAL GOVERNMENT

Parish government was in the hands of Preston's few farmers, who between them filled the offices of churchwarden, overseer of the poor, and constable. (fn. 210) There were two churchwardens in 1540 (fn. 211) and in 1626, but by the later 17th century only one churchwarden was appointed and he often remained in office for several years. In the later 18th century John Wood, the farmer at Preston Court, was churchwarden for many years. (fn. 212) From the mid 19th century there were again two churchwardens and farmers continued to hold the office for a number of years. (fn. 213) William Hartland resigned as rector's churchwarden in 1898 after 43 years of almost continuous service. (fn. 214)

Poor relief was administered in Preston by a single overseer. He was traditionally chosen by rotation among the farmers but in the later 18th century John Wood, whose farm took in many former copyholds, usually held the post, occasionally serving on behalf of another farmer. In the early 19th century the overseer remained in office for several years. In the mid 18th century relief was dispensed regularly to two people and a few apprenticeships to local farmers were arranged. Occasional medical expenses included a doctor's bill in 1759–60 for treating a case of smallpox. The overseer also made several payments for building or repairing cottages. (fn. 215) Two cottages erected at parish expense for the use of the poor stood next to each other in the fields in the north of the parish and each was let with a garden near by in 1803. (fn. 216) For several years from 1810 the churchwarden's and the constable's expenses were met out of the poor rate. (fn. 217)

The small size of the parish and its population meant that the cost of relief was among the lowest in the area, (fn. 218) even though by the 1780s it included the expense of keeping a parishioner in an asylum. (fn. 219) Between 1776 and 1784 the amount spent by Preston on the poor fell from £28 to £14, and in 1803, when three people received regular and six occasional assistance, the cost of relief was £52. (fn. 220) About half of that figure went to the asylum keeper, to whom payments continued until 1806. (fn. 221) In the following years expenditure on the poor increased as more families turned to the parish for support and in 1811 £108 was spent and weekly help was given to ten people. In 1813, when nine people received regular payments, the total cost of relief was £81. (fn. 222) It was at the same level in the late 1820s and fell well below £50 a year in the early 1830s. (fn. 223) Preston joined the Newent poor-law union in 1835. (fn. 224)

While an annual parish meeting or vestry appointed the churchwardens and dealt with matters concerning the church and churchyard in the mid 19th century, a separate meeting was convened regularly from 1877, if not earlier, to appoint two overseers and a waywarden for Preston. In 1873 and 1881 the parish also elected a poor-law guardian. Preston's few farmers of necessity often held several offices simultaneously and on several occasions the rector was waywarden. From 1894, when the ratepayers unanimously favoured the parish's transfer to Herefordshire and the Ledbury poor-law union, (fn. 225) the appointment of officers other than the churchwardens belonged to a civil parish meeting. That meeting was held annually and conducted little business. It convened less regularly after 1927 (fn. 226) and the civil parish ceased to exist when Preston became part of Dymock in 1935. (fn. 227)

SOCIAL HISTORY

SOCIAL STRUCTURE

For most of its history Preston was the possession of an absentee ecclesiastical landowner. (fn. 228) The eight people assessed for tax there in 1327 were all presumably tenants of Gloucester abbey. One, John in the field, was assessed for 4s. 2¼d., another for 1s. 8¼d., and the rest for amounts ranging from 1s. 3½d. to 10½d. (fn. 229) In the early 16th century the site of the manor was leased to John Sibles and his sons, of whom Richard was tenant in 1537. (fn. 230) Richard's widow Elizabeth was named in a muster for Preston in 1539. (fn. 231)

By the late 16th century the principal resident was the lessee, and de facto lord, of the manor. While the residence of John Powell, one of the first lords farmer, (fn. 232) Preston Court was visited many times in the early 17th century by his son-in-law (Sir) John Coke, who became a secretary of state in 1625. (fn. 233) In the late 1640s Anne Robins lived there with her son-in-law John Hanbury, a royalist and a former MP for Gloucester. (fn. 234) After the Restoration the lords farmer, apart from Anne Pauncefoot (d. 1715), (fn. 235) were non-resident and Preston Court became a farmhouse. (fn. 236) Visits by the lord farmer were rare enough for Sir George Pauncefote's presence at a church service in 1804 to be noted in the parish register. That visit sealed the family's association with Preston and Sir George and his successors, including Robert Pauncefote (d. 1843) who lived in Paris, were buried there. (fn. 237) In 1899, long after the family had relinquished the estate, (fn. 238) Sir Julian Pauncefote took the title Baron Pauncefote of Preston on his elevation to the peerage. (fn. 239)

In the early modern period much of Preston's small population belonged to farming families, such as the Drews and Gundeys, and there were apparently few landless labourers. Of fifteen men listed in 1608 one, John Cam, was a yeoman, six were husbandmen, and one was a labourer. Cam and three of the husbandmen were in the service of John Powell and one other man was also a servant. (fn. 240) A majority of the 12 people assessed for hearth tax in Preston in 1672 had 1 or 2 hearths, a few had 3 or 4 hearths, and William Vobes at Preston Court had 12 hearths. (fn. 241) From the late 17th century there was no resident clergyman (fn. 242) and in the mid 18th century the parish was run by a handful of farmers headed by the Wood family of Preston Court. (fn. 243) John Wood organized improvements in the parish church in 1773 (fn. 244) and agreed in 1796 to pay part of the cost of hiring the man whom Preston and Dymock were to provide for service in the navy. (fn. 245) In the early 19th century John and his son Charles farmed more than half of the parish from Preston Court (fn. 246) and one of the four other farmers was non-resident. (fn. 247)

The Wood family departed Preston in 1810 or 1811, (fn. 248) and from the mid 1830s, following a few years' occupation by Elizabeth Rickards, (fn. 249) Preston Court was the home of William Hartland, Preston's chief farmer. (fn. 250) In 1851 the population of 80 included 4 farmers, 18 agricultural labourers, 12 of whom lived with one or other of the farmers, and a few women in domestic service at Preston Court and White House Farm. (fn. 251) The vicar was resident from 1855 (fn. 252) and a new parsonage (later Preston Priory) built in 1864 (fn. 253) provided jobs in domestic service. In the late 19th century most Preston men were agricultural labourers and in 1901 ten of the 16 households were headed by farm workers and one by the blacksmith. (fn. 254) The population continued to be made up mostly of farmers and labourers until after the Second World War. (fn. 255) In the later 20th century the number of farmers fell to two (fn. 256) and agriculture ceased to be the chief source of employment.

SOCIAL LIFE

Ale was brewed and sold in Preston in the early 16th century. (fn. 257) There is no record that Preston ever had a licensed public house but in the early 19th century two of the farmsteads at Preston Cross had drink houses for the consumption, and perhaps sale, of cider. (fn. 258) Preston received no charitable endowments for the relief of poverty but the parish itself built two cottages for the use of the poor (fn. 259) and paid for wheat distributed to parishioners in 1800. (fn. 260) J.M. Niblett, the parson, ran a clothing club in 1892. (fn. 261)

There have been few schools in Preston and the parish clerk in 1605 was unable to read and write. (fn. 262) The parish was without a school in 1818 (fn. 263) but a Sunday school was started by 1825. (fn. 264) H.H. Hardy, the vicar, opened a day school in 1859. (fn. 265) A schoolmistress lodged with the blacksmith at Preston Cross (fn. 266) but the school was short lived as there were too few children for it to succeed (fn. 267) and in 1868 children went to schools in Little and Much Marcle (both Herefs.). (fn. 268) The new parsonage built in 1864 became a focus of church and parish life especially after 1879 when Revd Alfred Newton added a room to the stable block for use as a church hall. (fn. 269) Parish meetings were held in the room after 1894 (fn. 270) and A.P. Doherty, rector 1895–1912, taught labourers reading and writing in it. (fn. 271) A men's club used the room between the First and Second World Wars. (fn. 272) Scout and guide groups started by C.W. Dixon, rector 1913–16, lapsed under his successor. (fn. 273) Preston's children attended schools in neighbouring parishes, including Dymock and Little Marcle, during that period (fn. 274) and the older children later went to school in Newent. (fn. 275)

Immediately after the Second World War the church remained at the centre of social life and there was no public house. The nearest public telephone boxes were in Dymock and Little Marcle. Among the community groups in the area was a Women's Institute. (fn. 276) In the 1950s there were organized cricket matches in Preston and, to remedy the lack of a meeting place following the sale of the Victorian parsonage, Revd Daniel Gethyn-Jones obtained the use of an upper floor of an outbuilding at Preston Court as a church room. (fn. 277) The room remained a meeting place in 2004, being used by the Women's Institute for its monthly meetings. (fn. 278) A preparatory school opened at Preston Priory, the former Victorian parsonage, in 1959 closed a few years later. (fn. 279)

RELIGIOUS HISTORY

EARLY HISTORY AND STATUS OF THE PARISH CHURCH

Preston church originated as a chapel built by Gloucester abbey. It had its own graveyard in the 1130s (fn. 280) and the abbey had established a vicarage to serve it by 1291. (fn. 281) Following the abbey's dissolution the impropriate rectory, to which the manorial demesne tithes belonged, (fn. 282) passed like the manor to the bishopric of Gloucester (fn. 283) and by 1603 was annexed to the vicarage. (fn. 284) Although called a rectory in 1538, (fn. 285) the living continued to be styled a vicarage until it was designated a rectory officially in 1867. (fn. 286)

Preston was added to the united benefice of Dymock with Kempley in 1941 (fn. 287) but was reconstituted a separate benefice in 1955. (fn. 288) In 2000 it merged with eight other benefices in Gloucestershire and Herefordshire. (fn. 289)

PATRONAGE AND ENDOWMENT

Gloucester abbey retained the advowson of the vicarage until the Dissolution. (fn. 290) In 1378, during a vacancy in the abbey, the Crown made two presentations to the living on one day (fn. 291) and later that year it ratified the estate of a new vicar instituted on the abbey's gift. (fn. 292) In 1538 the abbey granted three Gloucester men the patronage at the next vacancy, which occurred in 1546. (fn. 293)

Ownership of the advowson passed with the manor to the bishopric of Gloucester in 1541. (fn. 294) In 1575 Anthony Higgins was patron for a turn (fn. 295) and the following year the bishop granted the next turn to John Powell. (fn. 296) John, who became lord farmer of the manor, (fn. 297) was patron in the early 17th century (fn. 298) and Anne Robins had both manor and advowson at her death in 1659. (fn. 299) The bishopric had the advowson after the Restoration (fn. 300) and the Crown presented to the vicarage during a vacancy in the see in 1690. (fn. 301) Leases of the manor granted between 1717 and 1730 included the patronage but the living did not fall vacant until after the bishop had reserved the advowson in 1734. (fn. 302) The bishop, who from 1941 had the right to present at the second of every three turns in the united benefice, (fn. 303) was confirmed as Preston's patron in 1955. (fn. 304)

In 1291 the church was worth £3 6s. 8d. (fn. 305) The vicarage, which included all the tithes save those of the manorial demesne, was worth £6 3s. 5d. in 1535. (fn. 306) Later, after the impropriate rectory was attached to his living, (fn. 307) the vicar received 30s. a year for the demesne tithes and in 1750 the living's worth was £40, including £11 rent for the glebe and vicarage house. (fn. 308) The tithes were commuted in 1844 for a corn rent charge of £127 3s. (fn. 309) and the living was valued in 1856 at £146. (fn. 310) Following an enlargement of the ecclesiastical parish in 1873 the incumbent received £10 8s. 7d. a year out of a stipend of the vicar of Dymock. (fn. 311)

The glebe comprised 31 a. in the mid 19th century, much of it in closes next to the vicarage house in the south-west of the parish some way from the church. (fn. 312) The house described as 'very mean' in 1750 (fn. 313) had two ground-floor rooms, one a kitchen, and two rooms above. In 1836 it was remodelled as the entrance and kitchen of a new house (The Parsonage) designed by Robert Jones of Ledbury for Charles Bryan; the additions comprised a west block, which projected beyond the line of the south front, and rooms on the north side. (fn. 314) The enlarged house was occupied for a time by a curate (fn. 315) but by 1851 it was used as a labourer's cottage (fn. 316) and in 1864 Alfred Newton built a new house (Preston Priory), to a Gothic design by Thomas Fulljames, on the Leominster road north-west of Preston Court. (fn. 317) The glebe and the old house were sold in 1886 (fn. 318) and the new house was sold in 1945. (fn. 319)

RELIGIOUS LIFE

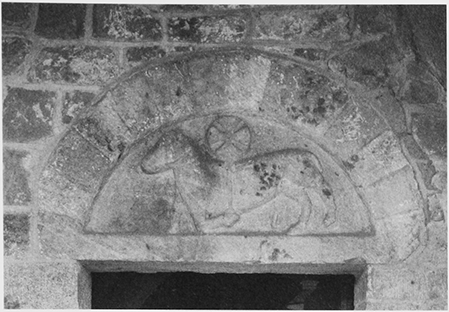

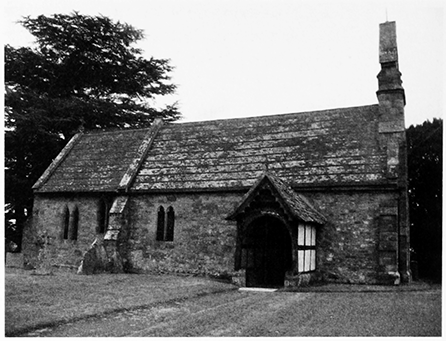

Preston church was a simple rectangular structure of squared rubble until it was elaborated in the mid 19th century. Original fabric of the late 11th or very early 12th century survives on the north side and indicates that the eastern end was extended or rebuilt in the 13th century. The Norman material incorporates one high window (blocked), corbel heads, and a squareheaded doorway. The decoration on the doorway's tympanum is carved in the style of the 'Dymock school' (fn. 320) with dummy voussoirs and an Agnus Dei; the lamb carries a Maltese cross rather than the more usual flag. (fn. 321) The 13th-century walling has pierced lancets. In the 14th century a timber-framed porch was added to shelter the north door and painted glass depicting the Crucifixion with St Mary and St John was set in the only window on the south side of the Norman nave. (fn. 322) The church's dedication to St John the Baptist is not recorded until the mid 19th century. The lessee of the manorial demesne maintained the chancel in the early 16th century (fn. 323) when there was no partiton between it and the nave. (fn. 324) The church, which retains an old, probably medieval, bell, (fn. 325) had a low wooden west tower in the early 18th century. (fn. 326)

70. Preston church: the north doorway tympanum

Of the early vicars John Harper (? Barbour) was deprived of the living in 1437. (fn. 327) James Jones, regularly cited in the manor court in the early 16th century for offences including affray and bloodshed, (fn. 328) retained the living until his death. John Smith, his successor in 1507, (fn. 329) resigned in 1515 having permission to negotiate a pension to be paid by William Davies, his successor. (fn. 330) Davies was accused of keeping a woman in 1526. (fn. 331)

Henry Wakeman or Worcester, who succeeded Davies in 1546, (fn. 332) was formerly a monk of Tewkesbury. (fn. 333) Unable to recite the Ten Commandments, in 1551, when the church had c.60 communicants, (fn. 334) he did penance for 'naughty living' (fn. 335) and in 1554 he was removed for being married. (fn. 336) His successor Richard Wheeler had been a chantry priest and a schoolmaster in Ledbury. (fn. 337) In 1576, when the vicar Edward Carwardine was non-resident, a curate wore a surplice on perambulation and issued an unheeded summons to children to learn the catechism. Carwardine, who was ordered to repair the vicarage house, not to let the living, and to preach quarterly sermons, (fn. 338) was neither a graduate nor a preacher. (fn. 339) His successor Nicholas Drew (fn. 340) was described in 1593 as a sufficient scholar but no preacher. (fn. 341) Although no recusants were recorded in Preston in 1603, (fn. 342) several parishioners, including a preacher, failed to take communion at Easter in 1605. (fn. 343) George Dixon, employed as Drew's curate for 20 years, (fn. 344) succeeded him as vicar in 1629 (fn. 345) and was among those resisting the 1635 writ of ship money. (fn. 346)

By the later 17th century Preston church was attended by the residents of the outlying parts of neighbouring parishes, notably Dymock. (fn. 347) The chancel was maintained by the lords farmer of the manor (fn. 348) and ornate monuments were erected in it to Anne Robins (d. 1659) and her son Richard (d. 1650) and plainer monuments to her grandson Sir Thomas Hanbury (d. 1708) of Little Marcle (Herefs.) and to Anne Pauncefoot (d. 1715). (fn. 349)

Edward Rogers, who subscribed to the Act of Uniformity as vicar in 1662, retained the living in 1666 but had resigned by 1671 (fn. 350) and became a nonconformist preacher in London; he was active in the Preston area in 1683, at the time of the Rye House Plot. (fn. 351) From the 1690s Preston's vicars were nonresident and pluralists (fn. 352) and in 1750, when the vicar, Robert Symonds, was a schoolmaster in Colwall (Herefs.), the church had one Sunday service, alternately in the morning and afternoon. (fn. 353) In 1730 one parishioner refused to pay church rates and attend services. (fn. 354) Among projects undertaken by John Wood as churchwarden were the acquisition in 1764 of a new bell cast by Thomas Rudhall (fn. 355) and a refurbishment of the church in 1773, when a Bible, prayer book, and surplice were purchased as well as a pulpit, reading desk, and other new furniture. Wood also donated railings for the churchyard. (fn. 356) In the later 18th and early 19th century curates usually served the church, (fn. 357) although Jenkin Jenkins, vicar 1780–1817, at first came in person from Donnington (Herefs.). (fn. 358) In the early 19th century the Pauncefotes, non-resident lords farmer of the manor, supported a subscription for a chalice (fn. 359) and several of them were buried at Preston. A memorial to Robert Pauncefote (d. 1843) (fn. 360) carved by Edward Gaffin of London was placed in the chancel.

Under John Kempthorne (1817–20), the evangelical protégé of Bishop Henry Ryder, (fn. 361) and Charles Bryan (1820–55) the church was served until 1834 from Donnington by P.G. Blencowe. (fn. 362) In 1825, when Kempthorne's version of the psalms was sung, the Sunday service was still held alternately in the morning and afternoon and the average congregation, swelled by the presence of people from outside Preston, was 30–50, including children. The number of communicants at the four communion services a year was 20. All the 14 children in the parish attended a Sunday school in the church where religious instruction was given once a fortnight. (fn. 363) In 1833 a Sunday school provided free education to 9 boys and 9 girls. (fn. 364)

71. Preston church from the north

Clergy had a more permanent presence in the parish from the mid 19th century. Curates occupied the vicarage house following its enlargement in 1836 but W.J. Morrish was required from 1846 to be resident for only three months a year and to live in the neighbourhood of Ledbury at all other times. (fn. 365) Morrish was probably the master paid in 1847 to teach 12 boys and 13 girls in the Sunday school in the church. (fn. 366) In 1851 the church's average congregation numbered 54. (fn. 367) H.H. Hardy, vicar 1855–63, (fn. 368) lodged at White House Farm (fn. 369) and energetically promoted religion and education. (fn. 370) In particular he secured money, mostly voluntary contributions, for the restoration and enlargement of the church in 1859 and 1860 to designs by the London partnership of Hugall & Male. (fn. 371) In that work a separate chancel was created by inserting a wall pierced by a wide arch fitted with a low timber screen, the nave south wall was dismantled to make way for a lean-to threebayed aisle in plain 13th-century style, and the west wall was buttressed to support a stone bellcot. The many new fittings and furnishings included an octagonal stone font and an old-fashioned pulpit and reading desk. (fn. 372) Among gifts from the Hardy family was carved furniture and William Drew, a farmer, donated the window containing the 14thcentury glass previously in the nave. (fn. 373) The church's dedication to St John the Baptist is recorded from 1863; in 1856 it was said to be to St Matthew. (fn. 374) The church had a pipe organ in 1878. (fn. 375)

Alfred Newton, Hardy's successor, (fn. 376) built a new vicarage house much nearer the church than the old one (fn. 377) and provided a meeting place for the parish at the new house. (fn. 378) In 1873 his parish was enlarged by the addition of the Hallwood green and Leadington area of Dymock and the Ludstock area of Ledbury. (fn. 379) From 1870, when church income came to depend on voluntary subscriptions, Newton and William Hartland provided most of the money but following the parish's enlargement more people contributed to the funds and from the later 1880s the Ecclesiastical Commissioners, the principal landowners, were regular contributors. There were also occasional collections at services and extraordinary items of expenditure, such as the erection of rails around the churchyard in 1898, were financed by subscription. Weekly church collections were introduced in 1914. (fn. 380) In the church in 1885 the chancel was almost entirely rebuilt and fenestration in both chancel and nave was altered to match the trefoil-headed lights in the aisle, all to designs by the firm of Waller, Son, & Wood. The new, enlarged east window was filled with memorial glass to Alfred Newton (d. 1884). (fn. 381) In 1896 a southeast vestry designed by F.W. Waller was added and, to compensate for its blocking the chancel south-east window, a north-east window was made. (fn. 382)

A.H.A. Camm, rector from 1931, was Preston's last resident incumbent and after his resignation in 1941 continued for a time to live in the Victorian parsonage and take church services. Under Daniel Gethyn-Jones, incumbent of Dymock with Kempley and Preston from 1941, the churchyard was enlarged in 1945. In 1955, when Preston became a separate benefice again, Gethyn-Jones remained rector and H.A. Edwards, formerly rector of Donnington, moved into the former Victorian parsonage to act as curate until his death in 1958. (fn. 383) From 1959 the church was served from Little Marcle (fn. 384) and from 1992 by a priest-in-charge living in Dymock. (fn. 385) On the union of benefices in 2000 it came under team ministry led from Redmarley D'Abitot. (fn. 386)

In 1994 a plaque displaying a bust of the poet John Masefield (d. 1967), who was baptized in the church in 1878, was placed on the nave north wall. (fn. 387) The church has been given an old chair in memory of Geoffrey Houlbrooke (d. 1991).