Whitehall: Historical and Architectural Notes. Originally published by Seely, London, 1895.

This free content was digitised by double-rekeying. Public Domain.

W J Loftie, 'Chapter IV', in Whitehall: Historical and Architectural Notes(London, 1895), British History Online https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/no-series/whitehall/pp61-78 [accessed 5 February 2025].

W J Loftie, 'Chapter IV', in Whitehall: Historical and Architectural Notes(London, 1895), British History Online, accessed February 5, 2025, https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/no-series/whitehall/pp61-78.

W J Loftie. "Chapter IV". Whitehall: Historical and Architectural Notes. (London, 1895), British History Online. Web. 5 February 2025. https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/no-series/whitehall/pp61-78.

CHAPTER IV

Legendary Anecdote of Cromwell and the Body of Charles I.—The Funeral—Cromwell at the Cockpit—Removes to Whitehall—Great State—Illness and Death—Richara Cromwell—Pepys on Whitehall—Lodgings in the Palace—Evelyn—St. George's Eve—Death of Charles II.—William and Mary—Royal Apartments Burnt— Conclusion.

It is very probable that, among the colonels and generals who lodged themselves, or were lodged, in Whitehall after the death of Charles I., Oliver Cromwell was one. Five years elapsed before he came into residence as Lord Protector, but, whether as a military commander or as a minister of state, there were several capacities in which he could have claimed chambers in the great straggling congeries of separate sets of apartments which were comprised in the palace. The amount of his guilt in the King's murder it is difficult to assess. He may have been no more involved than any other member of the Regicide party, except, of course, Bradshaw. Cromwell's subsequent prominence made him the subject of every rumour, every fable. When any one heard a story against a member of Parliament or an officer of the Roundheads, if no name was put to it, that or Cromwell was ready to hand. Jesse reports one which is more than usually improbable:—

After the decapitation of Charles, he is said to have paid a visit to the corpse, and, putting his finger to the neck, to have made some remarks on the soundness of the body and the promise which it presented of longevity. According to another account, on entering the chamber, he found the coffin closed, and, being unable to raise the lid with his staff, he took the sword of one Bowtell, a private soldier, who was standing by, and opened it with the hilt. Bowtell, asking him what government they should have now, he said the same that then was.

How an officer, even though he may have been on duty, could penetrate to the chamber of death in such a way must remain a mystery. The body of Charles was conveyed from the scaffold by the faithful Herbert, with Juxon's assistance. It was placed in one of the King's apartments, that nearest, we learn, to the back-stairs. Topham, private surgeon to Fairfax, was employed to sew on the head and to embalm the body. Permission was asked to bury it in the chapel of Henry VII., but this the republican authorities refused, though they provided five hundred pounds for the funeral expenses. A coffin covered with black velvet had been ready on the scaffold. In this the body was removed to St. James's Palace, and placed in a leaden coffin. There it remained more than a week, and was seen by many visitors. The execution had taken place on Tuesday, the 30th of January. On Wednesday, the 7th of February, a little procession was formed, consisting, besides the hearse, of four mourning coaches, in which were Bishop Juxon, the Duke of Richmond, Lords Hertford, Southampton and Lindsay, with Mildmay and Herbert. At Windsor the first halt was at the Deanery, but the coffin was afterwards removed to the King's apartments in the Upper Ward. Meanwhile a search was made in St. George's Chapel for a suitable vault, and, that which contained the remains of Henry VIII. and Jane Seymour having been discovered, the body of King Charles was carried by the Roundhead soldiers to the chapel, the snow falling thick on the coffin of the White King.

Many believed that his burial really took place within the precincts of Whitehall, but an examination of the grave of Henry VIII. in the reign of George III. revealed the decapitated corpse of Charles I., which, after a careful examination by Sir Henry Halford, was restored once more to its resting-place.

Oliver Cromwell appears to have had lodgings within the precincts of the palace, but at a great distance from the state apartments. A kind of village clustered round the Tennis Court, a little to the southward of the tilt-yard and the Horse Guards. A green lawn, and perhaps a garden, existed here, and here General Monk subsequently had his lodgings. A narrow passage or lane, known as the "Entrance to the Cockpit," led to them. It is as nearly as possible the modern Downing Street.

It was almost five years after the King's death before Cromwell was formally installed Protector. This was in December, 1653, a few days only before the end of the year, as we should reckon it, because in those days 1653 went on till the 25th of March, 1654. About one o'clock "his Highness" left the Cockpit in a coach of state. Before him went the judges, the members of the Council, the Lord Mayor, and the aldermen. The procession passed through King Street to Westminster Hall. There he accepted the articles which had been prepared, and the procession returned. In the Banqueting House a minister made an exhortation to the new Lord Protector, the Lord Mayor sitting by, and so the proceedings concluded.

Cromwell apparently returned for the time being to his lodgings in the Cockpit, and the state apartments were got ready for him. He went over to the Banqueting House to receive foreign ambassadors, which he did seated on something very like a royal throne. The whole palace was granted to him, and, as we have seen, it was at about this date when the sale of the royal collection of pictures ceased.

As the spring drew on he thought it was time to move. Jesse supplies us with the following notes on this event. The contemporary notices of the removal of the Protector to the stately apartments of Whitehall are not without interest:—

"April 13, 1654. This day the bed-chamber, and the rest of the lodgings and rooms appointed for the Lord Protector in Whitehall, were prepared for his Highness to remove from the Cockpit on the morrow."—"His Highness the Lord Protector, with his lady and family, this day (April 14) dined at Whitehall, whither his Highness and family are removed, and did this night lie there, and do there continue."—"April 15. His Highness went this day to Hampton Court, and returned again at night."

Hampton Court and Windsor Castle had been granted to him as well as Whitehall. Poor Mrs. Cromwell, who seems to have been of a simple and unostentatious character, can hardly have relished the change. She became "Her Highness the Protectress," and had more servants and attendants than she can have known what to do with. The exact part of the palace in which the new state apartments were placed is unknown. It was probably not where the late King lived, nor, on the other hand, can it have been far from the Banqueting House and the picture gallery. In addition to the Lord Protector and the Lady Protectress, room had to be found for their august family and for sons-in-law and children. It is not uninteresting to read this contemporary notice from the Weekly Intelligencer:—

"The Privy Lodgings for his Highness the Lord Protector in Whitehall are now in readiness, as also the lodgings for his Lady Protectress; and likewise the privy kitchen, and other kitchens, butteries and offices; and it is conceived the whole family will be settled there before Easter. The tables for diet prepared are these:—

"A table for his Highness.

"A table for the Protectress.

"A table for Chaplains and Strangers.

"A table for the Steward and Gentlemen.

"A table for the Gentleman.

"A table for coachmen, grooms, and other domestic servants.

"A table for Inferiors, or sub-servants."

Nothing can be more curious than to observe the change which seems to have come over the plain Huntingdonshire squire. He arrogated to himself and received all the deference previously paid to a sovereign. He allowed nothing to be omitted, and many of his contemporaries, English as well as foreign, have noticed the magnificence and stateliness of the ceremonious observances at his court. Jesse has summarised a few of these notes, and it is well worth while to quote some of his expressions. A few weeks after his elevation, we find the Protector entertained by the citizens of London with all the honours which, for centuries, they had been accustomed to pay to their sovereigns on their accession. Monsieur De Bordeaux writes to De Brienne, 23rd of February, 1654:—"On his solemn entry into the City he was received like a king: the Mayor went before him with the sword in his hand about him nothing but officers, who do not trouble themselves much as to fineness of apparel; behind him the members of the Council in State coaches, furnished by certain lords. The concourse of people was great; wheresoever Cromwell came a great silence; the greater part did not even move their hats. At the Guildhall was a great feast prepared for him, and at the table sat the Mayor, the Councillors, the Deputies of the Army, as well as Cromwell's son and son-in-law. Towards the Foreign Ambassadors, the Protector deports himself as a king, for the power of kings is not greater than his."

Again, De Bordeaux writes a few weeks afterwards:—"Some say he will assume the title and prerogatives of a Roman emperor. In order to strengthen his party, he deals out promises to all parties. It is here, however, as everywhere else; no government was or is right in the people's eyes, and Cromwell, once their idol, is now the object of their blame, perhaps their hate."

There is a record of May Day in the same year, 1654. The writer is much shocked at the licence that prevailed. There was "much sin committed by wicked meetings, with fiddlers, drunkenness, ribaldry, and the like." Cromwell kept open house at Whitehall on Mondays. In 1657, the Speaker announced to the House of Commons that the Lord Protector invited the whole House to dinner in the Banqueting House, and he had similarly received them the year before.

Cromwell's last illness seized him at Hampton Court. He was removed to Whitehall. There, while a tremendous tempest howled round the old walls, he breathed his last on the afternoon of the 3rd of September, 1658. The concourse of fanatical preachers which disturbed his last moments seems to have been doubled at his death, and Tillotson, the future Archbishop, describes Richard Cromwell as seated at one side of a table with six divines at the other. Cromwell's funeral took place from Somerset House, not from Whitehall, so it does not specially concern us. Suffice it to say here, that no king or queen has ever been interred at so much cost or so magnificently.

There is little except Tillotson's note quoted above to connect Richard Cromwell with Whitehall; but a meeting of discontented officers which he permitted at Wallingford House, over the way, precipitated his fall. It has always been asserted, apparently with truth, that Oliver's wife had been inclined to Royalism, and that she pressed her husband to bring in the late King's son. This did not, however, prevent her from an endeavour to secure some of the royal effects at Whitehall, when she, in her turn, received notice to quit. Early in 1660 they were taken possession of by a Commission.

For the next few years the name of Whitehall is chiefly to be found in the delightful pages of Pepys, and those of that sanctimonious prig, Evelyn. Mr. Wheatly, who has made a special study of Pepys, tells us, in his London, Past and Present, that the chief apartments of Whitehall mentioned in the Diary are as follows:— The Matted Gallery, the Gallery of Henry VIII., the Boarded Gallery, the Shield Gallery, the Stone Gallery, and the Vane Room. We may identify some of these. The Gallery of Henry VIII. was probably that which led over Holbein's Gate to the park. The Shield Gallery must be that spoken of by Manningham, about the end of the reign of Queen Elizabeth, as being decorated with scutcheons. There was a Guardroom, mentioned by Lilly, the astrologer. The Adam and Eve Gallery was so called from a picture attributed to Mabuse, now at Hampton Court. The Stone Gallery looked on the Sundial Lawn in the Privy Garden. Pepys also mentions the Banqueting House, where in April, 1661, he "saw the King create my Lord Chancellor, and several others, Earls, and Mr. Crew, and several others, Barons: the first being led up by Heralds and five old Earls to the King, and there the patent is read, and the King puts on his vest, and sword and coronet, and gives him the patent. And then he kisseth the King's hand, and rises and stands covered before the King. And the same for the Barons, only he is led up but by three of the old Barons, and are girt with swords before they go to the King." In the Banqueting House, also, the King touched "people for the King's evil" (June 23, 1660). There was a service "At the Healing" in Books of Common Prayer. It was omitted, I think, about 1709. There was a "balcone" in the Shield Gallery. In this room Pepys saw the King bid farewell to Montagu, who was going to sea. "I saw with what kindness the King did hug my lord at his parting." We have a topographical note in July, 1660. Pepys walked all the afternoon in Whitehall Court. We know where the Court was, and now we learn that the Council Chamber looked into it. "It was strange to see how all the people flocked together bare, to see the King looking out of the Council window." There are many references to the Chapel. It stood near the river, in the eastern part of the palace, and had two vestries. Inigo Jones designed a beautiful reredos of coloured marbles for it. This reredos was saved when the palace was burnt, and was given by Queen Anne to Westminster Abbey. There is a view in Dart's Westminster Abbey which shows it—the only representation of it I have met with. It was destroyed in the early days of the so-called Gothic revival, and a piece of stucco-work by Bernasconi took its place. That again was "restored" away in favour of a very poverty-stricken piece of mosaic, which by some blunder was made too small for its place, and had to be eked out with a meaningless border. A small fragment of Inigo's altar-piece is in the triforium.

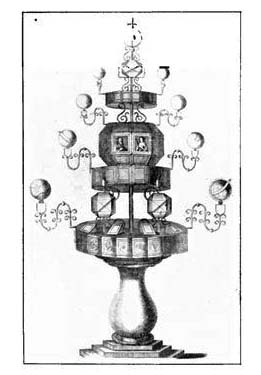

Pyramidal Dial in Privy Garden, set up in 1669. From an Engraving by H. Steel, 1673.

Pepys was much pleased (8th July, 1660) to hear the organ in Whitehall Chapel. The old organs had been destroyed under the Commonwealth all over the country, but now the diarist writes:— "Here I heard very good music, the first time that ever I remember to have heard the organs and singing men in surplices in my life." There are many other mentions of the chapel, and, on one occasion, Mr. Hill took him up to the King's Closet, a kind of gallery looking into the chapel, the King being away—"and there we did stay all service-time, which I did think a great honour."

He has something to say about the works of art at Whitehall. On one occasion he admired "a great many fine antique heads of marble that my lord Northumberland had given the King." Next he inspected the pictures. They consisted (1) of those sold by the Commonwealth and recovered; (2) those retained by Cromwell; and (3) a collection which, having been bought by a Dutchman from Whitehall, was obtained by the States of Holland from his widow, and presented to Charles II. on his restoration. The gallery which, as we shall see, is mentioned by Evelyn, appears to have been used as a kind of drawing-room in the evening.

Pepys and his wife were present on one occasion when the Queen dined at Whitehall. This Queen was Henrietta Maria, the widow of Charles I. He describes her as in her Presence Chamber, and says she was a very little, plain old woman, and nothing in her presence or her garb different from any ordinary person. He goes on: "The Princess of Orange I had often seen before. The Princess Henrietta is very pretty, but much below my expectation; and her dressing of herself with her hair frizzed short up to her ears, did make her seem so much the less to me." A little further on he tells of being locked by accident into "Henry the Eighth's Gallery," and being unable to get into the Boarded Gallery. In 1666, he mentions a dining-room, but where it was he does not tell us. There are many other notices of Whitehall in the Diary, but the foregoing are probably the most important.

Whitehall in 1724.

When we look at Vertue's plan already mentioned, nothing is more striking than the number of separate residences the palace contained. The plan purports to have been made in the reign of Charles II., and is dated 1680. There are, however, apparently, two or three anachronisms. At least a score of dukes and other nobles had their quarters in the palace, including Monk, now Duke of Albemarle, who, with his awful Duchess, has the pleasant house by the Cockpit, occupied by Cromwell before he became Protector. It is said to have been from this house that the Princess Anne set off on her famous ride with the Bishop of London, to meet William of Orange, in 1688. Lady Castlemaine, the Duke of Monmouth, the Duke of Ormonde, and Captain Cooke, of whom Pepys sometimes speaks in disparaging terms, and who was master of the singing boys in the King's Chapel, or something of the kind—all these were close to the Cockpit. In the other part of Whitehall—east, that is, of the "street" —were apartments for the King himself, the Queen, the Maids of Honour, for Lord Bath, Lord Peterborough, the Duke of Richmond, a Mrs. Kirk, a Lady Sears, and a vast number of people of whom history has recorded but little, including "Mr. Chiffinch." There are, besides, a number of officials, such as the Cofferer, the Queen's Secretary and Waiters, the Treasurer, the Chamberlain, the Doctor, and the pages of the back-stairs. A few years later an apartment adjoining the Stone Gallery was granted to Louise Renée de Penancoet de Keroualle, duchess of Portsmouth, whom Evelyn describes as having "a childish, simple, and baby face."

Evelyn, like Pepys, makes occasional mention of Whitehall Chapel and of the other buildings. We need not quote more than one or two. In April, 1667, he writes:—

"22nd.—Saw the sumptuous supper in the banqueting-house at Whitehall, on the eve of St. George's Day, where were all the companions of the Order of the Garter.

"23rd.—In the morning, his Majesty went to chapel with the Knights of the Garter, all in their habits and robes, ushered by the heralds; after the first service, they went in procession, the youngest first, the Sovereign last, with the Prelate of the Order and Dean, who had about his neck the book of the Statutes of the Order; and then the Chancellor of the Order (old Sir Henry de Vic), who wore the purse about his neck; then the Heralds and Garter-King-at-Arms, Clarencieux, Black Rod. But before the Prelate and Dean of Windsor went the gentlemen of the chapel and choristers, singing as they marched; behind them two doctors of music in damask robes; this procession was about the courts at Whitehall. Then, returning to their stalls and seats in the chapel, placed under each knight's coat-armour and titles, the second service began. Then, the King offered at the altar, an anthem was sung; then, the rest of the Knights offered, and lastly proceeded to the banqueting-house to a great feast. The King sat on an elevated throne at the upper end at a table alone; the Knights at a table on the right hand, reaching all the length of the room; over-against them a cupboard of rich gilded plate; at the lower end, the music; on the balusters above, wind music, trumpets, and kettle-drums. The King was served by the lords and pensioners who brought up the dishes. About the middle of the dinner, the Knights drank the King's health, then the King theirs, when the trumpets and music played and sounded, the guns going off at the Tower. At the Banquet, came in the Queen, and stood by the King's left hand, but did not sit. Then was the banqueting-stuff flung about the room profusely. In truth, the crowd was so great, that though I stayed all the supper the day before, I now stayed no longer than this sport began, for fear of disorder. The cheer was extraordinary, each Knight having forty dishes to his mess, piled up five or six high; the room hung with the richest tapestry."

Then comes the end in a well-known and oft-quoted passage. It was in the winter of 1685. Why Evelyn visited Whitehall that particular Sunday we do not know. His description of the scene at Whitehall the last Sunday but one of the life of Charles II. is not new to any one, but must come in here: "I can never forget," he says, "the inexpressible luxury and profaneness, gaming and all dissoluteness, and as it were total forgetfulness of God (it being Sunday evening) which this day se'nnight I was witness of, the King sitting and toying with his concubines, Portsmouth, Cleveland, and Mazarine, etc.; a French boy singing love-songs in that glorious gallery, whilst about twenty of the great courtiers and other dissolute persons were at Basset round a large table, a bank of at least 2000 in gold before them; upon which two gentlemen who were with me made reflections with astonishment. Six days after was all in the dust."

Funeral of Queen Mary, 1694. From an Engraving by P. Persoy.

James II. seems to have preferred St. James's to Whitehall as a residence during his brief and stormy reign. All his children were born there, and there is an account of his Queen, Mary of Modena, hastening from Whitehall just before the birth of the prince who became subsequently the Old Pretender.

William and Mary were hardly settled at Whitehall when they began to look about for a house which would suit the King's health. At Whitehall he was constantly ill. The low, foggy, damp situation was not calculated for a man who suffered daily from asthma and often from ague or low fever. One day he looked at Holland House, and we read in the Kensington parochial accounts of the church bells being rung as he went through the suburban village. Holland House was perhaps too far away; but William next visited what was really the old manor house of Neyte, in Westminster, which was then called Nottingham House. It was purchased for him, and renamed Kensington Palace, and henceforth neither Whitehall nor St. James's saw much of him or of Queen Mary, except on state occasions. We gather from Evelyn that Charles II. had given suites of apartments to the Duchess of Portsmouth, whom the people called Madam Carwell, and others. The Duchess of Cleveland had a house near St. James's, and afterwards lived in Arlington Street. Nell Gwynne lived in Pall Mall: so that of all those "curses of the nation," as Evelyn calls them, only this Frenchwoman remained. If we look at Vertue's map, though we shall not see any mention of the lodgings of the Duchess, we do see an entry which, as it turns out, is more important. It points out the room of the King's laundress.

She was a Dutchwoman at this time, and made a charcoal fire to dry a shirt belonging to a Colonel Stanley. The situation of the room, if it was the same as that of the laundress of King Charles, is precisely that in which a fire, once set going, might spread in all directions, as it was surrounded with small chambers, probably with wooden partitions, and then again by chapels, libraries, galleries, halls, and other inflammable buildings. The unhappy Dutchwoman set her room on fire and perished in the flames. "The tapestry, bedding, the wainscotes were soon in a blaze," says Macaulay. "Before midnight, the King's apartments, the Queen's apartments, the wardrobe, the treasury, the office of the Privy Council, the office of the Secretary of State, had been destroyed." Evelyn mentions a second chapel as having been fitted up for James II.: both perished. The guardroom also, and the glorious gallery of which Evelyn speaks. The Banqueting House was saved, but some pictures by Holbein in the Matted Gallery were burnt out, and there was said to be considerable loss of life. We shall see presently why so many valuable pieces of furniture and pictures were saved. Some of them found their way across the park to St. James's. Others went as far out as Kensington, and are now to be found partly at Windsor and partly at Hampton Court.

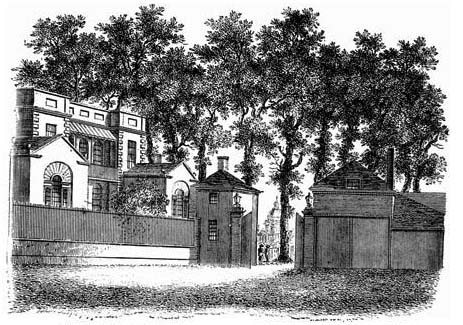

Scotland Yard.

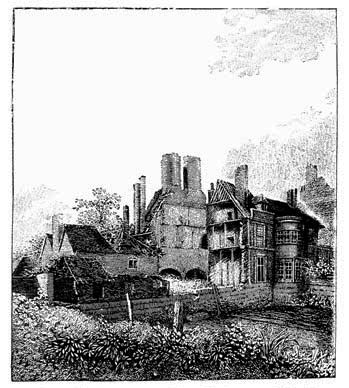

Part of the Old Palace of Whitehall. From an Etching by J. T. Smith, 1805.

The fire occurred on the night of the 4th January, 1698, and the King returning from one of his expeditions to Holland, found his palace, as he came up the river, in ruins. William himself acknowledges in a letter to a foreign friend that the accident, as he calls it, affected him less than it might another, because Whitehall was a place in which he could not live. Several fires had occurred within a short time at Whitehall, the most destructive being that by which in April, 1691, the Duchess of Portsmouth was burnt out, after having had her house three times rebuilt, a subject on which Evelyn enlarges in his usual pious manner. The Duchess went to live in Kensington, and survived until far on in the reign or George II. All these fires did damage, but that of the 4th January, 1698, seems to have been almost or altogether confined to the royal apartments. Macaulay's account of the fire is enormously exaggerated. The whole palace, on both sides of the "street of Whitehall" was mainly intact still—a vast region stretching up beyond Scotland Yard, and almost to Charing Cross. Abundant remains of the Tudor period were still to be seen twenty years ago by those who sought for them. I remember a pointed window in a basement as lately as 1877. The fact is, this part of the palace was never destroyed by fire, but perished gradually, being pulled down piecemeal, to make way for other buildings, or falling into decay.

View in Privy Garden. From an Engraving by J. Malcolm, 1807.

The first fire destroyed the Stone Gallery and the rooms between it and the river. This Stone Gallery, as already mentioned, ran along the east side of the Privy Garden. It was not rebuilt, and the Duchess of Portsmouth lost her house. After the second fire the ground was leased out, and Pembroke House was built on it. I think it is now part of the Board of Trade. The rest of the row is now called Whitehall Gardens, a place in which many eminent people have lived, including Sir Robert Peel, one of the Queen's Premiers. Beyond, further south, was the Bowling Green. Here Montagu House now stands. We may feel sure, when we see how little was burnt, that William and Mary, if they had liked the place, might easily have reinstated the royal lodgings.

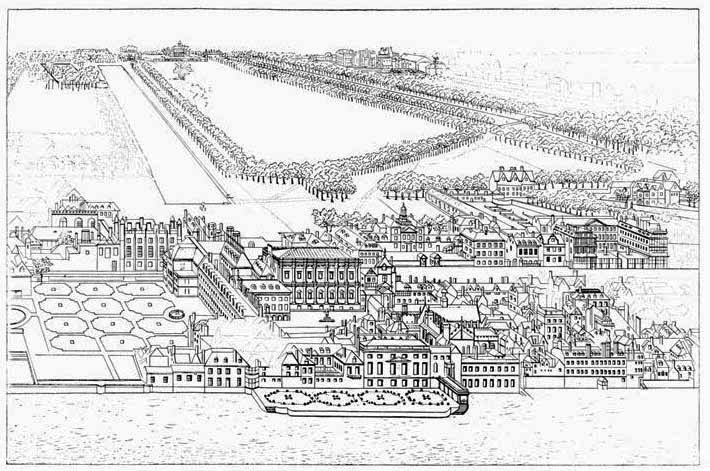

There is a curious print in Smith's Sixty-two Additional Plates, which seems to have puzzled some people. It represents Whitehall in a bird's-eye view in outline, and must have been drawn after the second fire, as Pembroke House has been built. The original drawing was in Crowle's collection. Smith stumbles over it when he says, "The dotted lines show the parts that were not penned in 'by the artist.'" He does not perceive that they mark places which had been burnt and had not been rebuilt. For us this print is interesting, as showing what a comparatively small part of the whole perished in the fire of 1698, and it shows us also what is the true answer to a question often asked: Why were not the pictures consumed? We can see now that they may have been taken down, all but the Holbeins, which were painted on the walls and ceiling of a chamber, and leisurely stored, probably in the Banqueting House, to be removed to St. James's and Kensington as convenient. In the same way there was time to remove anything of value from the chapel, including Inigo's great marble reredos. Indeed, it may be doubted if the chapel was burnt.

Privy Garden. From an Engraving by T. Malton, 1795.

At the beginning of the last century there remained the two gates. The queer old Gothic King Street Gate was taken down in 1723. In 1759, Holbein's Gate was also removed, including, of course, the stairs and gallery by which Charles I. entered the palace on that fatal 30th January. The terra-cotta heads of the Cæsars eventually went to Hampton Court. They are said to have been made by an Italian named Maiano. The brick and stone-work were removed by the Duke of Cumberland to make a triumphal arch at Windsor. They form now a green mound near the Long Walk. Toby Rustat's leaden statue of James II. still stands behind the hall, and is popularly supposed to point to the spot on which James's father was beheaded. We have seen that this tragedy took place at the other side of the hall. There was an immediate talk of a new palace on this site, but it never came to anything. The second plan of Inigo Jones, that of 1639, is sometimes said to have been consulted by the authorities. Colen Campbell obtained it for his Vitruvius Britannicus, as he says, "from that ingenious gentleman, William Emmet, of Bromley, in the county of Kent, Esq., from whose original drawings the following five plates are published, whereby he has made a most valuable present to the sons of Art." Was Mr. Emmet, that ingenious gentleman, who seems otherwise unknown to fame, the architect consulted by William's Government ?

Bird's-eye View of Whitehall and St. James's Park, From Smith's "Views of Westminster,"