A History of the County of Gloucester: Volume 7. Originally published by Oxford University Press for Victoria County History, Oxford, 1981.

This free content was digitised by double rekeying. All rights reserved.

'Brightwells Barrow Hundred', in A History of the County of Gloucester: Volume 7, ed. N. M. Herbert (Oxford, 1981), British History Online https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/vch/glos/vol7/pp1-4 [accessed 2 February 2025].

'Brightwells Barrow Hundred', in A History of the County of Gloucester: Volume 7. Edited by N. M. Herbert (Oxford, 1981), British History Online, accessed February 2, 2025, https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/vch/glos/vol7/pp1-4.

"Brightwells Barrow Hundred". A History of the County of Gloucester: Volume 7. Ed. N. M. Herbert (Oxford, 1981), British History Online. Web. 2 February 2025. https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/vch/glos/vol7/pp1-4.

Brightwells Barrow Hundred

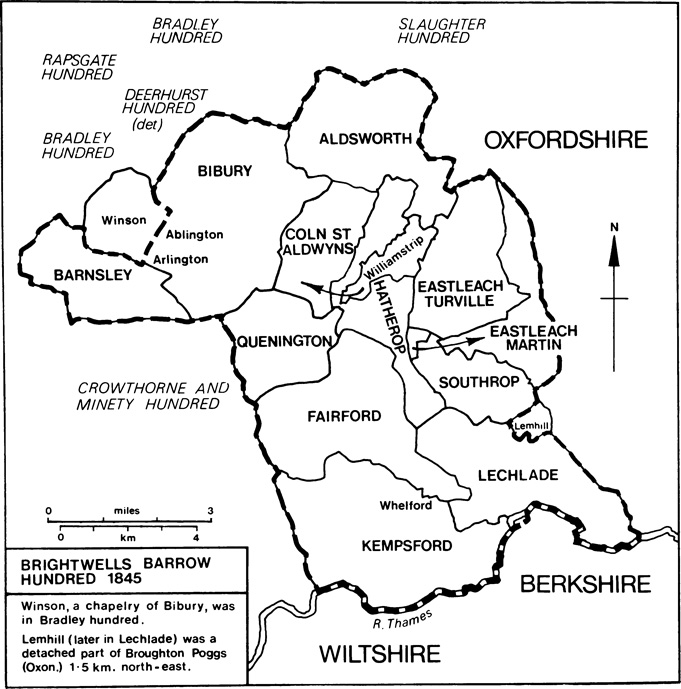

In 1086 Brightwells Barrow hundred comprised Coln St. Aldwyns, Williamstrip (then called Hatherop but later a part of Coln St. Aldwyns), Eastleach Martin, Eastleach Turville, Fairford, Hatherop, Kempsford, Lechlade, Quenington, and Southrop (then, like the Eastleaches, called Leach), and was assessed at a total of 102 hides and 4 yardlands. (fn. 1) Another Domesday hundred, called Bibury, comprising Aldsworth, Bibury (which then included Barnsley), Arlington (a tithing of Bibury), and Eycot, was assessed at 40 hides. (fn. 2) References to Bibury hundred found in the late 13th century (fn. 3) presumably relate only to the separate frankpledge jurisdiction enjoyed by the bishop of Worcester, for by 1221 the Bibury hundred manors had for other purposes been included in Brightwells Barrow hundred. (fn. 4) Eycot, which became part of Rendcomb parish, remained in Brightwells Barrow hundred in the 14th century. (fn. 5) In 1086 Winson, later a chapelry of Bibury, was included under Bradley hundred where it emerged as a separate civil parish. (fn. 6)

Brightwells Barrow hundred was one of the group known as the Seven Hundreds of Cirencester (fn. 7) which was granted to Cirencester Abbey in 1189. The descent and liberties of the Seven Hundreds have been treated in an earlier volume. (fn. 8)

At Bibury the bishops of Worcester retained wide liberties, including return of writs, view of frankpledge, and gallows, (fn. 9) and in 1272 the bishop, who had a prison in Barnsley, was disputing with Cirencester Abbey procedure in cases concerning thieves caught but not red-handed. (fn. 10) The Bibury liberty covered the area of the former hundred including Ablington (a tithing of Bibury) but the court rolls, surviving from 1382, (fn. 11) contain no evidence that Barnsley was represented at the frankpledge court. (fn. 12) The suit of Arlington was withdrawn in the mid 13th century (fn. 13) and later the lord of the Bibury rectory estate held view of frankpledge. (fn. 14) Gloucester Abbey's tenants in Ablington apparently attended a biannual view held in Coln Rogers. (fn. 15)

Elsewhere in Brightwells Barrow hundred three manors secured full quittance of hundredal jurisdiction. The lords of Fairford, a member of the honor of Gloucester, claimed view of frankpledge, gallows, pillory, tumbril, and waif in 1287 (fn. 16) and their court was also the frankpledge court for part of Eastleach Turville and, after the mid 13th century, Arlington. (fn. 17) The view was also held on Quenington manor, owned from the mid 12th century by the Knights Hospitallers, (fn. 18) and on Southrop manor by the early 14th century. (fn. 19) In three other manors the rights of the lord of the hundred were limited. Under an agreement made in the 1230s the biannual view of frankpledge for Hatherop manor was held in the manor court by Cirencester Abbey's bailiffs and the lady of the manor received the amercements for an annual composition and enjoyed pecuniary rights in the hue and cry. (fn. 20) A similar arrangement was in force at Kempsford, apparently by 1258, (fn. 21) but in the later 16th century the view for both places was held by manorial stewards. (fn. 22) About 1230 Cirencester Abbey granted the lady of Lechlade the right to a tumbril and pillory and the profits of the biannual view, which was to be held in her court by the abbey's bailiffs; (fn. 23) in the later 13th century the lords of the manor unsuccessfully claimed wider liberties, including gallows, and the free tenants withdrew their suit from the hundred court. (fn. 24) In 1367 the abbot of Bruern (Oxon.) laid claim unsuccessfully to gallows on his Eastleach Turville manor. (fn. 25)

The remaining places in the hundred were represented at the biannual hundred view of frankpledge at which Coln St. Aldwyns, Eastleach Martin, and part of Eastleach Turville with Williamstrip each formed single tithings. (fn. 26) The meeting-place was in the centre of the hundred at the junction of the Droitwich—Lechlade saltway and a route from Fairford where a barrow was mentioned in 1400; (fn. 27) a tree growing on the barrow later gave the name Barrow Elm to the meeting-place. (fn. 28) In the early 15th century Gloucester Abbey provided overnight hospitality for the court's officers in near-by Coln St. Aldwyns (fn. 29) and in the 1530s the lessee of Hatherop manor entertained Cirencester Abbey's steward holding courts at Barrow Elm. (fn. 30) In the later 16th century views were held there in the spring and autumn and the tithings made presentments and paid cert money, that for Coln St. Aldwyns and Eastleach Martin being called hole silver. At those views Williamstrip was sometimes represented separately and representatives of Hatherop, Kempsford, and Lechlade appeared in order to pay cert money and ask permission for the manorial stewards to hold the view or else for the hundredal lords' bailiffs to be sent to hold it. (fn. 31) The custom of wardstaff involving watching duty on certain nights, although exacted from Hatherop but not from Kempsford and Southrop in 1394, (fn. 32) was limited by the later 16th century to those tithings attending the view and in the autumn they owed a 3d. fine called wake, evidently in place of it. (fn. 33)

The twelve parishes of the hundred formed a compact group at the south-eastern corner of the county, extending from high Cotswold downland in the north to flat and relatively low-lying land by the river Thames, which marks the southern boundary. The higher land is mostly on oolitic limestone and the lower on clay. The most notable features of the landscape are the valleys of the rivers Coln and Leach which flow into the Thames near Lechlade. The rich alluvial soil of the southern part has been well suited for meadow land. In contrast the higher land above the valleys was farmed as open fields and common pasture and some landowners compensated a shortage of meadow land with property in Kempsford and other Thamesside parishes near by. Gravel beds in the southern part were not exploited on any scale until the mid 20th century. Architecturally the area is rich in churches of which those at Fairford and Lechlade were rebuilt in the late 15th century. Of several substantial country houses the most notable is the 18th-century Barnsley Park. The most important early routes crossing the hundred were a salt-way from Droitwich to Lechlade, the old Gloucester—London road (the Welsh way) which passed through Barnsley and Fairford, and the Roman Akeman Street running east-north-eastwards from Cirencester, but in the coaching era and later the Cirencester—London road through Fairford and Lechlade and the Cirencester—Oxford road through Bibury were the main roads. The Thames and Severn canal, opened in 1789, crosses the south part of the hundred to meet the Thames just above Lechlade. The only railway line to penetrate the hundred, a branch line from Witney (Oxon.) to Fairford, was in operation from 1873 until 1962.

In the Middle Ages settlements in the hundred were, with the exceptions of Aldsworth and Barnsley, located beside one of the three rivers. Eastleach Martin (known also as Botherop), Southrop, Williamstrip, Hatherop, and its hamlet of Netherton (formerly Netherup) all share a place-name element that recalls their origin as farmsteads dependent on older settlements. (fn. 34) The villages and hamlets of the central and northern parts have remained small and Netherton was depopulated in the mid 19th century. In the south the market town of Fairford, established at an important road junction and a crossing of the Coln, was a borough from the 12th century. Dominated by John Tame, a wool-merchant, in the late 15th century, it later depended on local trade and road traffic. Lechlade, sited at the head of the navigable Thames close to an important crossing of the river, was a borough and market town from the early 13th century. Later the road traffic and the consignment of goods, particularly cheese, down river to London provided the bulk of its trade. Both towns remained small, their growth possibly inhibited by their proximity to each other.

The land was used extensively for sheep-farming in the Middle Ages, especially by ecclesiastical landowners, including the bishop of Worcester, the Knights Hospitallers, and the abbeys of Cirencester, Gloucester, Lacock (Wilts.), Bruern (Oxon.), and Oseney (Oxon.). A cloth-making industry based on Fairford and mills in the Coln valley was of no great significance, and the hundred remained predominantly agricultural and centred on its estates and large farms. Landowning families, including the Barkers, Coxwells, and Thynnes, had an important influence, and in the northern part of the hundred much land passed into the Hatherop, Williamstrip, and Sherborne estates. The northern part remained sparsely populated in the 1970s when a factory in Quenington was the only significant representative of manufacturing industry. From the mid 20th century there was some expansion in the southern part, for which airfields in Kempsford and Brize Norton (Oxon.) provided employment and which came under the regional influence of Swindon. In the 1970s the hundred with its picturesque scenery was favoured as a residential area, and its rivers, of which the Coln had long been known for trout-fishing, and its flooded gravel pits were developed for recreational purposes.