Ancient and Historical Monuments in the City of Salisbury. Originally published by Her Majesty's Stationery Office, London, 1977.

This free content was digitised by double rekeying. All rights reserved.

'New Street Chequer', in Ancient and Historical Monuments in the City of Salisbury(London, 1977), British History Online https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/rchme/salisbury/pp95-107 [accessed 1 February 2025].

'New Street Chequer', in Ancient and Historical Monuments in the City of Salisbury(London, 1977), British History Online, accessed February 1, 2025, https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/rchme/salisbury/pp95-107.

"New Street Chequer". Ancient and Historical Monuments in the City of Salisbury. (London, 1977), British History Online. Web. 1 February 2025. https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/rchme/salisbury/pp95-107.

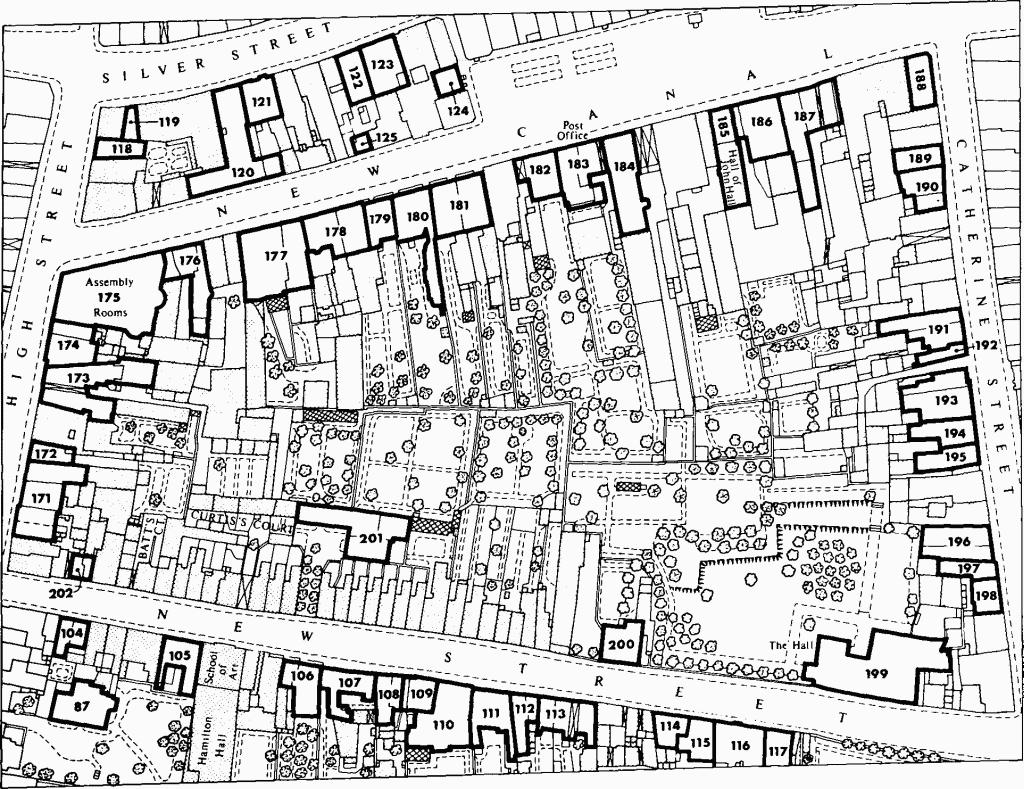

New Street Chequer

Monuments in Mitre Chequer, New Street Chequer and New Street.

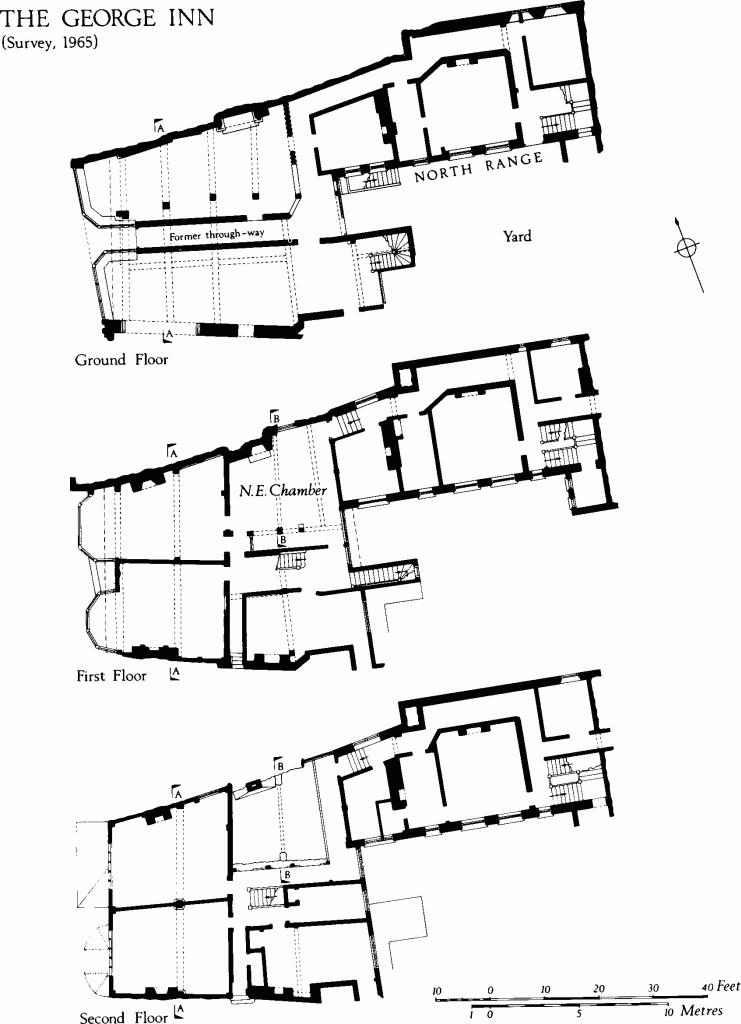

The George Inn

(Survey, 1965)

(171) Houses, four adjoining, Nos. 25–31 High Street, of three storeys with brick and tile-hung walls and with slate-covered roofs, were built early in the 19th century. All the ground-floor rooms have been obliterated to make shops. Nos. 29–31 were originally a pair of houses, but have been combined; they have a common W. front of two bays with plain sashed windows in each upper storey. No. 27, of c. 1830 and with a two-bay facade, now contains two ground-floor shops. No. 25, demolished and rebuilt in 1975, had a two-bay facade of c. 1800 with a single sashed bow window at first-floor level. Inside, all four houses had plain 19th-century joinery and plasterwork. Below the ground floor, No. 25 retained the lower part of a former cellar with N., E. and S. walls of coursed stonework, perhaps mediaeval.

(172) House, No. 23 High Street, demolished in 1967, was of three storeys and had rendered timber-framed walls, jettied in the W. front, and tiled roofs; it was of 16th-century origin. The lower storey contained a modern shop front; the second storey had two 18th-century bow windows under the jetty; the jettied third storey had two 19th-century sashed windows, each with three lights (Plate 102). The roof had collared tie-beam trusses with lower angle struts and clasped purlins.

In mediaeval times the site was part of a tenement called The Leg, of which the history is traceable through deeds dating from 1364. (fn. 1) In 1455, when it belonged to William White of Mere, another tenement owned by him in New Street provided a back entrance. (fn. 2) Subsequently the whole property belonged to Sir Thomas Audeley, and in 1495 part of it was leased to John Godfrey, tailor. Audeley's property included a kitchen and a barton. The kitchen and barton appear again in a deed of 1533 together with shops, solars and a cellar. During the 16th century the whole tenement passed to the Tailors' Guild, which retained it until late in the 19th century. A description is included in the survey of guild lands made in 1657. (fn. 3) The extent of the tenement in 1823 is shown on a plan by W. Sleat. (fn. 4)

(173) The George Inn, as it survives, is of two and three storeys with walls mainly of timber framework and with tiled roofs (Plate 61). The existing W. range is only a small part of an important inn, mainly built during the third quarter of the 14th century, but also making use of antecedent buildings. A strong wall of rubble and ashlar on the N. side, parallel with New Canal and therefore joining High Street front obliquely, probably dates from the 13th century. A stone doorway and window in the S. range, now gone, but attested in 19th-century drawings (below, p. 98), was perhaps of the same period.

The inn belonged to the corporation from 1413 to 1858, but after c. 1760 it was occupied not as an inn, but as dwellings. In 1858 the buildings again became a hostelry, but were extensively altered, everything being pulled down except the W. range. About the same time, the N. range was built. In 1967 the N. range was demolished and the lower storey of the W. range was remodelled, the carriage through-way which led from High Street to the inn yard being replaced by a wider passage as the pedestrian entrance to a modern shopping precinct (Old George Mall). The upper rooms of the W. range were adapted as a restaurant.

A detailed history of the inn might be compiled from the numerous deeds, leases and surveys preserved in the city archives. William Teynturer the younger (mayor 1361 and 1375), a merchant of great energy and enterprise who left much property when he died in 1377, (fn. 5) bought three properties in High Street in 1357 and 1361. (fn. 6) All of these may have become part of the inn site, especially one acquired from the family of John de Homyngton, cook, which included a shop with solars beside an entry which led to the hall of another house, then occupied for life by Peter Moundelard who had been living there since 1342. It is possible that Moundelard's house contained the stone doorway and window mentioned above. In 1371 Teynturer added a curtilage which lay 'behind the tenement and wall of William Mountagu in Wynchestrestret' (now New Canal; i.e. the site of monument (176), an 18th-century building). (fn. 7) A document of 1401 mentions a barn and a laundry in the S. part of the ground obtained from Mountagu; (fn. 8) this probably corresponds with the barn at the George leased with other buildings to Thomas Allesley, 'osteler', in 1427. (fn. 9) The earliest use of the name 'Georgesin' occurs in a deed of 1379 relating to the adjacent house (172). (fn. 10) The name recalls the merchant guild of the city, dedicated to St. George, and it is not unlikely that Teynturer from the beginning of his ownership meant the inn to become city property. (fn. 11) The purchase of the property by the city took place in 1413 when royal and episcopal licences permitted the city to acquire property to the value of 100 marks; (fn. 12) thereafter the George appears in the chamberlain's account rolls. (fn. 13) Some idea of the inn's furnishings and movable fittings may be obtained from the list of goods and utensils which were left for sale by the last private owner, Sir George Meriot, who died in 1410. (fn. 14) The inn came to him through his wife Alice, previously married to William Teynturer. The most interesting of numerous later documents is a lease of 1474 to John Gryme, which includes an inventory of permanent fittings. (fn. 15) Fourteen lodging chambers are listed, each with a distinctive name and all furnished with beds and tables; the principal chamber was the only room in which a fireplace is mentioned. There is no mention of a hall (the word aula denotes a small lobby adjoining the Fitzwareyne chamber); the tavern or wine cellar and the buttery were used as public rooms. The surviving building, with only five chambers, is insufficient in relation to the known extent of the mediaeval inn for any identification of rooms to be possible. Later descriptions of the George occur in surveys of city property made in 1618, 1716 and 1783. (fn. 16) The extent of the buildings in the 19th century is recorded on a plan of c. 1850 by F.R. Fisher (Plate 13); (fn. 17) it shows the inn's narrow frontage to High Street, with the through-way leading to a narrow courtyard surrounded by buildings; further E. were other yards and stables.

The picturesque quality of the buildings attracted many 19th-century artists whose work affords some idea of the former appearance of the street front and of the courtyard (Plates 4–7). Buckler's drawing of 1805 shows the remains of the pargeting which was applied in 1593. (fn. 18) Inside the yard, the W. part of the N. range, near the E. end of the through-way from High Street, comprised a tall building with first and second-floor jetties; it was drawn thus by W.H. Charlton in 1813 (Plate 6), but the top storey had been removed when the view by Goodall and Surgey was painted, c. 1850 (Plate 4). Closing the E. end of the courtyard, Sir Henry Dryden in a watercolour dated 1859 (Plate 6) shows a three-storeyed building with two gables with elaborately cusped bargeboards; the same building is shown in a drawing of 1833 by William Twopeny (Plate 7). A passage on the N. of this building led to the stable yard. The drawings show that the eastern part of the S. side of the courtyard was overlooked by an open first-floor gallery projecting on curved brackets, a feature which made the yard suitable for plays as ordained in 1624. (fn. 19) Further W., the S. side of the courtyard had a three-storeyed building, jettied at the second floor. Measured sketches of 1863 by Dryden (Northampton Public Library) show that the lower storey of this building contained a stone doorway with chamfered jambs shouldered at the top to support a flat lintel, characteristic of the 13th century; beside it was a small chamfered square-headed window. Hall illustrates the same features. (fn. 20) Neither opening appears in Dryden's watercolour of 1859, but they are seen in Charlton's drawing, although here the doorway is shown as round-headed. Adjacent, in the S.W. corner of the courtyard, Charlton, Dryden and Goodall-Surgey all show a square, tower-like structure of two storeys, apparently of brick with ashlar dressings, with a pyramidal tiled roof; a classical entablature lay just below the upper window-sill and the square-headed E. doorway had a classical architrave. By its style this structure dated from about the middle of the 17th century. Dryden's sketch plan of 1863 shows that it contained a newel stair.

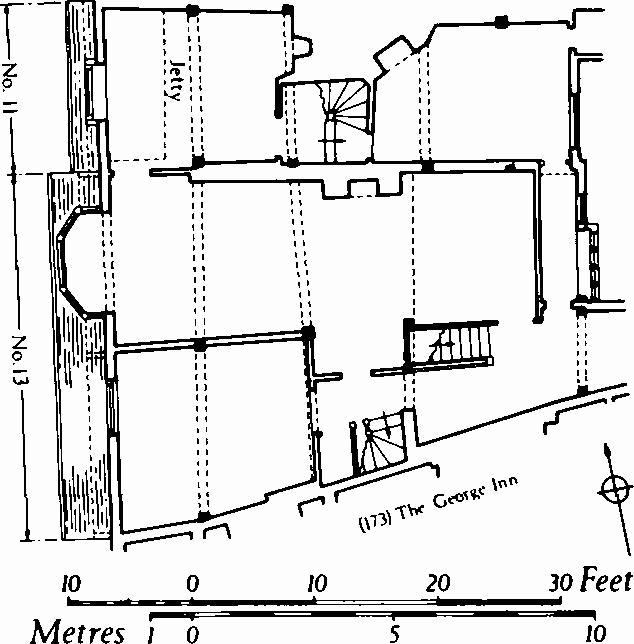

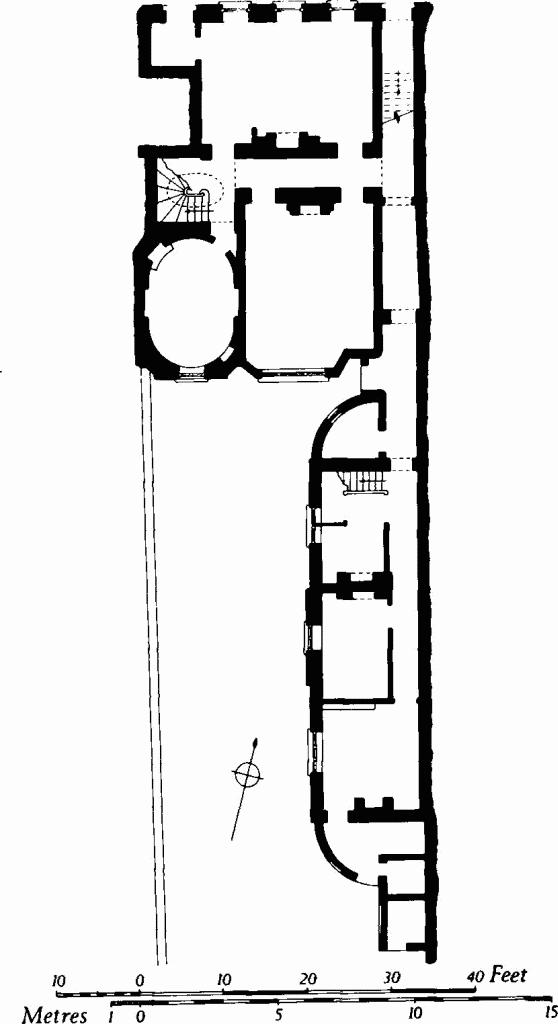

The three-storeyed W. front has modern shop windows in the lower storey. Since the photograph on Plate 61 was taken, the 14th-century oak N.W. pier of the former carriage through-way, seen in Buckler's drawing of 1805 and in Twopeny's drawing of 1833, has been exposed (Plate 84) and a modern replica of its S.W. counterpart has been supplied. The large 17th-century bow windows in the second storey remain as depicted in the 19th-century drawings, except that the pargeting has gone. The third-storey windows are modern restorations of original lights closed in the 17th century. Removal of the plaster has revealed cross-braced timber framework. Because the ground plan is trapeze-shaped, the E. elevation of the 14th-century range is three bays wide in contrast to the two bays of the W. front; the entire E. elevation is, however, hidden by modern tile-hanging. The demolished 19th-century N. range had a three-storeyed S. elevation of brick, with plain sashed windows in each storey and with plat-bands marking the floor levels. (Plan on p. 96.)

Inside, the irregular N. wall is built to the height of the first floor in ashlar with panels of knapped flint-work, the latter including some tile. A former fireplace set at a high level, and corresponding beam-holes in the masonry, now blocked, show that the ground floor was once about 2 ft. above present street level, thus making room for a basement storey on the N. of the throughway. An entrance to this basement appears in an old photograph (Plate 104).

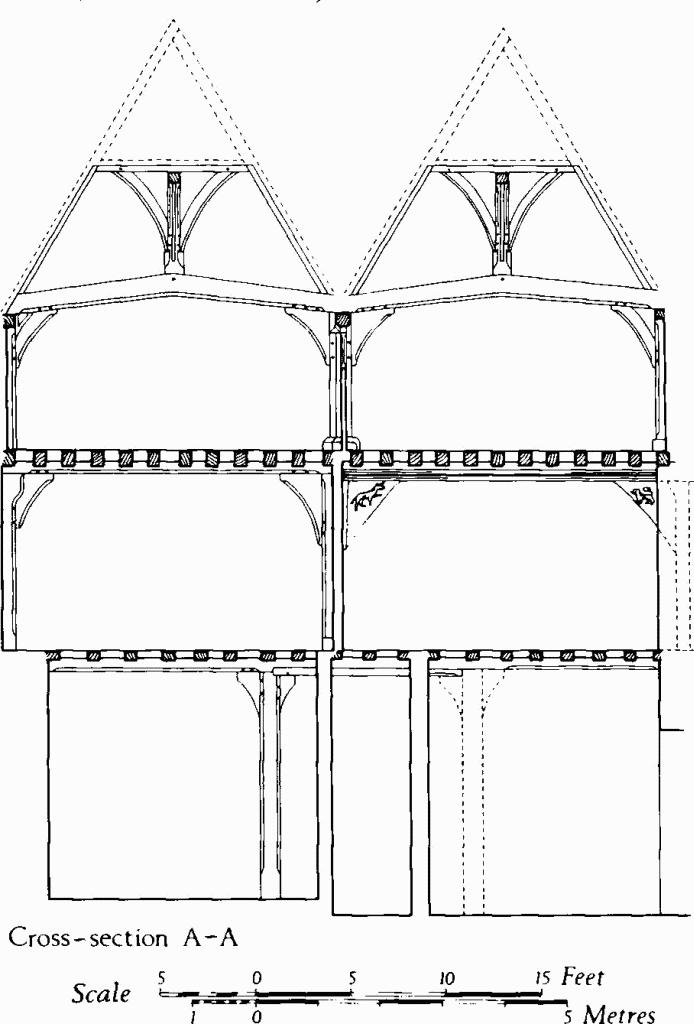

Before the alterations of 1967 the N. side of the through-way was represented by a row of free-standing timber posts braced to the first floor with curved brackets. The corresponding posts which once formed the S. side of the through-way had gone, but their positions were shown by mortices in the first-floor beams (cross-section A—A).

(173) The George Inn

Section, looking E.

On the first floor, the N.W. room retains original chamfered wall-posts, wall-braces, and a large N.–S. beam joined to the wall-posts with chamfered braces. In the embrasure of the 17th-century window are seen the overhanging members of the original second-floor jetty. In the S.W. room the beam and its braces are encased in 17th-century plaster enriched with a frieze of griffins (Plate 93).

(173) George Inn

N.E. chamber.

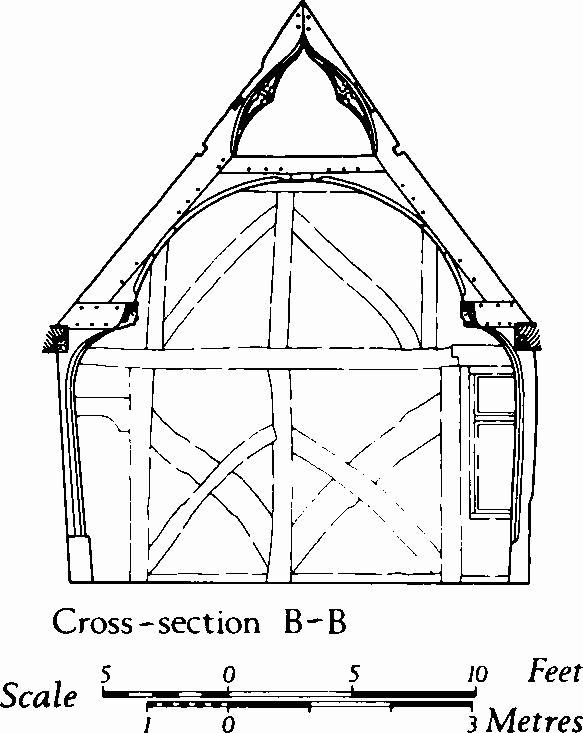

While the W. part of the range is of three storeys, the E. part is two-storeyed, with a large N.E. chamber open to the roof. As in the W. rooms, the walls of this chamber have massive 14th-century timber uprights with crossbracing (cross-section B—B). The central wall-posts on N. and S. have moulded sides and curve out at the top to support a false hammerbeam truss; the ends of the horizontal members are carved to represent a bearded king's and a queen's head (Plate 84); above, there are moulded arch-braces. Over the collar the principals are enriched with ogee mouldings and traceried cusps. The collar-purlin and the original rafters have been replaced by later through-purlins and common rafters. The 14th-century moulded wall-plates remain, with carved flowers at the ends of the mouldings. Original doorways with shouldered lintels occur in the N. part of the E. wall and in the W. part of the S. wall.

On the second floor, each of the two W. chambers is spanned by a cambered and roll-moulded beam supporting a crown-post and a collar-purlin (Plate 83). Mouldings on the gable tie-beams show that the present modern windows replace original openings. The wall-plates are moulded and enriched.

In the 19th-century N. range, demolished in 1967, the thick N. wall was probably mediaeval. Reset in the E. part of the range was an early 17th-century staircase (Plate 87); since 1967 its balustrade has been reused in monument (174).

(174) Houses, two adjoining, Nos. 11 and 13 High Street, are of three storeys with attics and have tile-hung timber-framed walls and tiled roofs. Both buildings are now combined with the George Inn (173) to make shops and restaurants. No. 11 is of mid 15th-century origin. No. 13, of 1476, takes the place of two mediaeval cottages which were given to the Dean and Chapter in 1459 by William Harding, canon and clerk-of-works to the cathedral. (fn. 21) In 1476 the work of rebuilding occasioned a legal settlement concerning encroachment on the George Inn. (fn. 22) By 1649 the houses had been united and were occupied by John Joyce, apothecary. (fn. 23)

(174) Nos. 11 and 13 High Street

First floor.

The W. front of No. 13, remodelled in the 18th century, is jettied at the second floor and at first-floor level has a pentice, but no jetty (Plate 102). The N. bay in the second storey has a bow window with an ogival lead roof. Originally the facade had two gables, but the valley between them was roofed-in during the 18th century and the former gables were concealed by tilehanging. Inside, the lower storey has been modernised. On the first floor, although partitions have been removed, it is clear that there were formerly two W. rooms and one to N.E.; that on the N.W. retains some 17th-century oak panelling in four heights and a modelled plaster ceiling; the panelling is mentioned in the Parliamentary Survey. The beam at the head of the former partition between the N.W. and N.E. rooms has a 17th-century black-letter inscription: 'Have God before thine eies, who searcheth hart & raines, and live according to his law, then glory is thy gaines'. The chimneypiece in the N.E. room is composed of reset pieces of enriched oak panelling, some of it 16th-century work. Since 1967 the balustrade of the 17th-century staircase from the N. range of monument (173) has been reset in No. 13.

The W. front of No. 11 is of the 17th century, with a small jetty at the second floor and with an 18th-century window in each upper storey. The 15th-century W. front, however, stood some 8½ ft. behind the present facade; its alignment is indicated by the outline of the original second-floor jetty, seen in the W. room of the first floor. The position of the former street-front falls on a straight line drawn from the S.W. corner of Mitre chequer to the original ground-level front of the George Inn (173). Inside, the E. room on the ground floor had, until 1967, a chimneypiece composed of reset early 17th-century oak panels with arabesque enrichment. The E. room on the first floor had a handsome mid 17th-century chimneypiece (Plate 92), now gone. In the third storey the original street-front gable, with king and queen struts, now forms an internal roof truss.

(175) Assembly Rooms, now a shop, on the corner of High Street and New Canal, are of two storeys with brick walls and tiled roofs. The building dates from 1802 (S.J., 1 Nov. 1802; 26 Aug. 1804). The three-bay W. elevation with a projecting porch and tall round-headed windows is seen in an early photograph (Plate 104). The lower storey has been completely modernised. On the first floor (plan, O.S., 1880), the main Assembly Room is used as a warehouse. Original neo-classical plaster enrichment survives.

(176) House, No. 53 New Canal, the Spread Eagle Inn in 1854 (Kingdon & Shearm), demolished 1966, was of three storeys and had walls mainly of brick, but with some tile-hung timber framework, and a tiled roof. Most of the structure was of the late 18th century, but the timber-framed W. wall probably represented an earlier building. The four-bay N. front had modern shop windows in the lower storey and plain sashed windows above. Inside, some rooms had panelled dados. The stairs had closed strings and turned balusters.

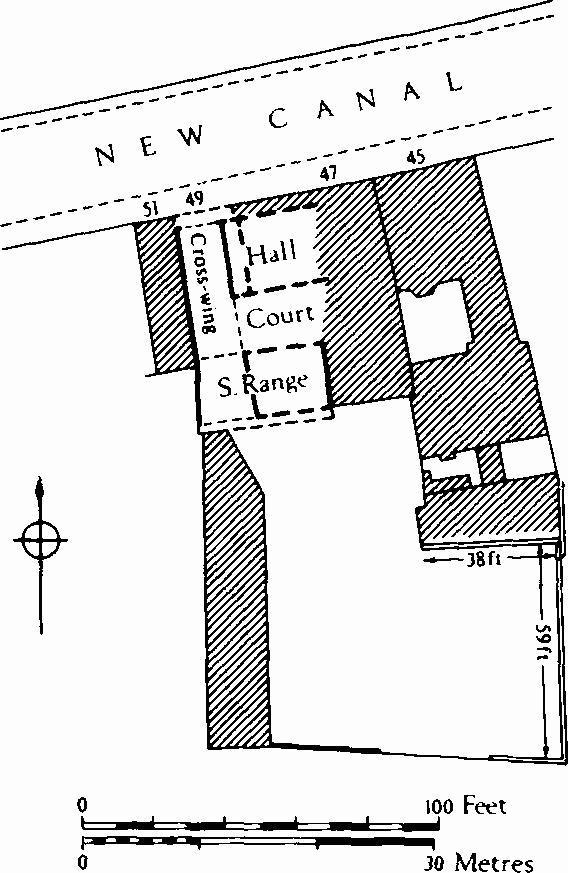

(177) Houses, Nos. 47–9 New Canal, of two storeys with timber-framed walls and tiled roofs, were to a large extent demolished in 1966 and the small part which survives was 'restored' and altered. Before demolition the houses contained remains of a substantial 14th-century dwelling in which there had been a lofty hall with a two-storeyed cross-wing at its W. end. The lower storey of the cross-wing contained a carriage throughway. South of the hall and E. of the through-way there had been a courtyard, and beyond this there was a 16th-century S. range. After 1966 the N. part of the cross-wing was incorporated with a modern shop; the rest was demolished.

The site is identifiable with a tenement held successively by Richard Todeworth and Henry Russel, mayors during the period 1320–40; (fn. 24) In 1365 Russel's executor, Henry Fleming, sold it to William Teynturer, owner of the George Inn (173). On Teynturer's death it passed with the George to his widow Alice and so to her second husband, John Byterlegh, wool merchant. Byterlegh died in 1397, (fn. 25) and Alice married Sir George Meriot. On Meriot's death in 1410 the tenement passed to William Alisaundre, who still had it in 1428. (fn. 26) The deeds repeatedly mention a stone-walled garden measuring 59 ft. by 38 ft.; a piece of ground approximately this size, partly defined by stone walls, was still identifiable in 1961 (see plan). The deeds also mention two two-storeyed shops W. of the house. These possibly explain the restricted plan, wherein the carriage through-way and the hall screens-passage lay side-by-side in the cross-wing, underneath the solar.

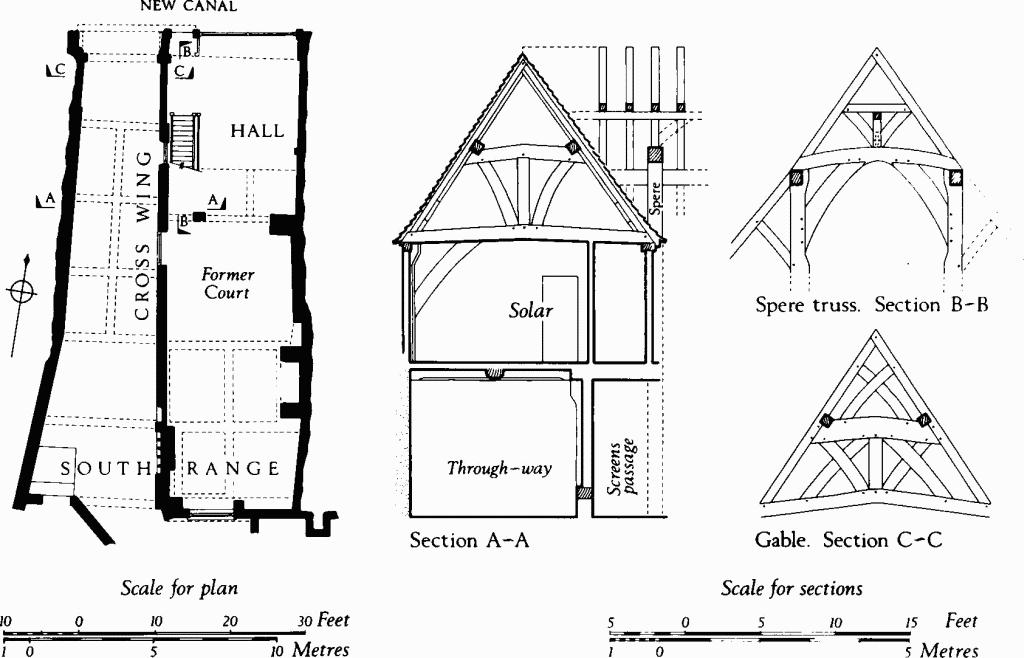

(177) Nos. 47–9 New Canal

Ground plan and cross-sections.

Until 1966 the whole of No. 47 and the E. part of No. 49 were fronted by three-storeyed 18th-century facades with sashed windows in the upper storeys and with a continuous dentil cornice below a plain parapet; the ground storeys had shop windows. The cross-wing in the W. part of No. 49 was two-storeyed, gabled and jettied at the first floor (Plate 60); it remained very much as drawn by William Twopeny in 1833 (Plate 7). The lower storey of the cross-wing contained two openings: on the W. was the entrance to the carriage through-way; on the E., where Twopeny depicts a wall, there was a 19th-century doorway. The gate to the through-way was flanked by stout ovolo-moulded posts with brackets to support the jetty. The gateway occupied little more than two-thirds of the width of the cross wing and the N.E. corner of the upper storey was supported on a dragon beam. (Since 1966 the E. spurpost has been moved and an intermediate post has been supplied.) Cross-braced timber framework, now seen in the upper storey and gable, was revealed in 1967 and is original (section C–C). The cusped bargeboards remain as drawn by Twopeny and are the only surviving example of a mediaeval feature once common in Salisbury.

Inside, the ground and first-floor rooms of No. 49 had no notable features, but in the roof over the N. room mediaeval timbers were found in situ. Parallel with the carriage through-way and about 3½ft. to the E. was a well-preserved spere truss with posts 14 ins. thick supporting massive purlins and a cambered tie-beam with curved braces;above these were trussed rafters and a braced collar-purlin (sections A–A, B–B). Without doubt the spere truss marked the W. end of the hall; its timbers were smoke-blackened on the E. side only.

At ground level, the 3½ ft. gap between the E. side of the carriage through-way and the place where the spereposts must originally have stood was evidently a screenspassage; it was entered by a door from the through-way (described below). The E. end of the hall may have been marked by the wall between Nos. 47 and 49, where a moulded post came to light during demolition, or the hall may have extended as far as the E. side of No. 47.

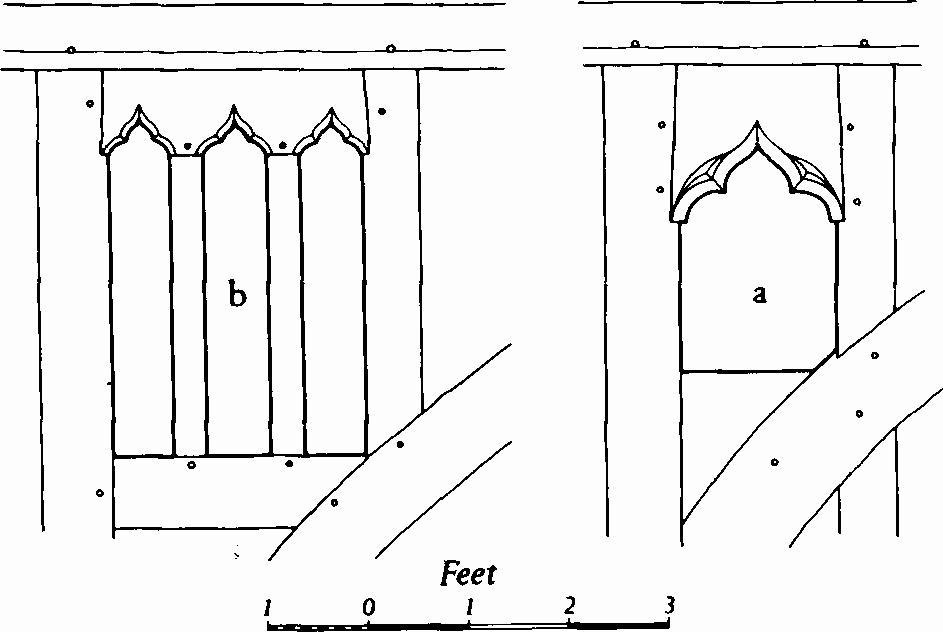

The timber-framed wall seen by Twopeny on the E. side of the through-way was revealed during demolition; the doorway had ogee-moulded and hollow-chamfered jambs, but the shaped head seen in Twopeny's drawing had gone. The W. wall of the through-way was of stone and flint to the level of the first floor. Over the throughway, stout chamfered transverse and longitudinal first-floor beams remain in position. Above the first floor the W. wall, now largely rebuilt, was of timber framework, and at this level there were three windows: near the N. front was a small 14th-century loop with a trefoiled ogee head (a); about 25 ft. further S. was a 14th-century three-light window with three trefoiled heads cut in a single beam (b); beside the latter was a 16th-century opening of three square-headed lights with ovolo-moulded oak mullions. The wide interval between the first and second windows probably accommodated the pitched roof of the two-storeyed shop, mentioned in the deeds as being next-door.

(177) First-floor windows in cross-wing.

A top-lit ground-floor room to the S. of the area of the hall replaced the former courtyard; probably it was roofed over in the 19th century. Further S. was a two-storeyed 16th-century range, parallel with the hall, its upper storey bridging the S. part of the through-way. The ground-floor room had intersecting ceiling beams cased in 17th-century moulded plaster. On the E. was an open fireplace with chamfered stone jambs and a stone lintel with a raised centre. In the timber-framed W. wall, an unglazed window of five lights with diagonallyset oak mullions originally looked over the carriage through-way, but it had been blocked internally. The first floor was jettied southwards. The upper storey contained a single large room with a roof of three bays. Enough of the roof remained to show that it originally had two false hammerbeam collar trusses with arched braces. There were clasped purlins above the collars, and chamfered windbracing between the purlins and the wall-plates.

(178) Houses, two adjacent, Nos. 45 and 43 New Canal, demolished in 1967, were two-storeyed with attics and probably dated from c. 1600, but they had three-storeyed 18th-century brick facades. Some timber framework was seen inside.

(179) House, No. 39 New Canal, demolished in 1967, was of two storeys with an attic and was built late in the 18th century.

(180) House, No. 35 New Canal, of three storeys with brick walls and tiled and leaded roofs, was a late 18th-century town house ingeniously planned to make the most of a restricted site. In 1967 the N. front was remodelled to make it suitable for a shop and the rest of the building was demolished. The W. front of the narrow single-storeyed S. range had gauged-brick dressings and a pedimented central feature with a round-headed window. Inside, the E. passage retained fragments of a plaster vaulted ceiling, removed for the insertion of a later staircase. The principal stairs had mahogany handrails and a plain balustrades; above was an oval sky-light with a moulded cornice. On the first floor, the two N. drawing rooms had moulded and enriched cornices, and that on the E. contained a neo-classical chimneypiece of wood with carton-pierre enrichment.

(180) No. 35 New Canal

Ground floor.

(181) Houses, pair, Nos. 33 and 31 New Canal, of three storeys with attics, with brick and tile-hung walls and with tiled roofs, were demolished in 1967; they had been built about the middle of the 18th century. Each house had a uniform three-bay N. front with modern shop windows below, sashed windows in the two upper storeys and a cornice with modillions. The windows had flat gauged-brick heads with stone keys and shoulders. Inside, the main rooms had panelled dados and each house had a staircase with a 'Chinese' lattice balustrade (Plate 89).

(182) House, No. 27 New Canal, demolished in 1967, was of three storeys with attics and had brick walls and tiled roofs. The N. front, of five bays with modern shop windows in the lower storey, plain sashed windows above and segmental-headed windows in the third storey, (fn. 27) was of the 18th century, but the house itself was of the late 16th or early 17th century. Inside, the main rooms had 18th-century joinery, but the stairs from the second floor to the attics were of oak, with close strings, moulded handrails and turned balusters. The roof had three collared tie-beam trusses with two purlins on each side.

(183) House, No. 25 New Canal, demolished in 1967, was three-storeyed with attics and had walls partly of timber framework and partly of brick, and a tiled roof. Of late 15th-century origin it had been extensively altered in the 18th century. The N. front had modern shop windows at ground level and sashed windows symmetrically arranged in five bays in the upper storeys. The original roof, ridged E.–W., was of four bays with collared and arch-braced tie-beam trusses supporting two purlins on each side.

(184) House, No. 19 New Canal, now a shop and offices, is of two and three storeys with rendered brick walls and slated and tiled roofs. The N. part of the building is of the 19th century. The two-storeyed S. wing has an E.–facing early 17th-century window of six transomed square-headed lights with chamfered stone mullions and a moulded stone label with returned stops. Adjacent is an 18th-century bow window with six sashed lights. Inside, the S. ground-floor room retains part of an early 17th-century moulded plaster ceiling and an open fireplace with a moulded stone surround. The roof, with collared tie-beam trusses with two purlins on each side, retains some glazed ridge tiles with ribbed decoration.

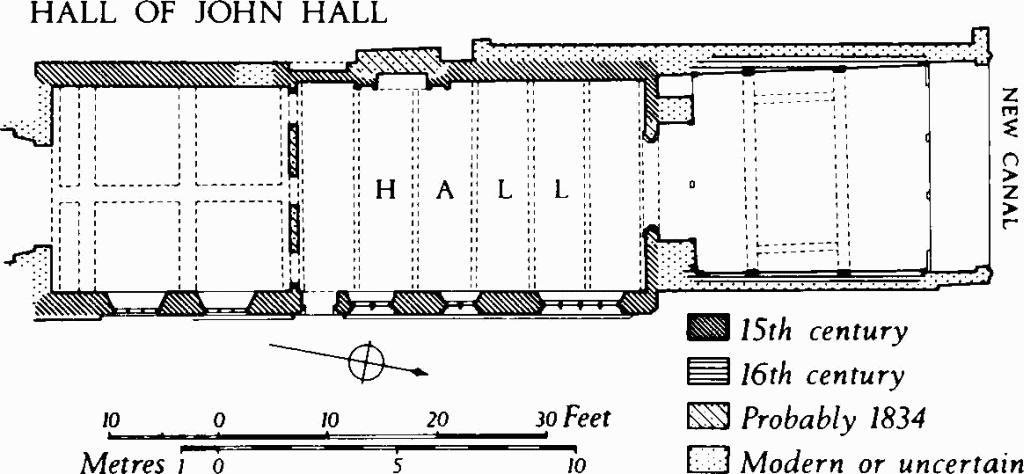

(185) Hall of John Hall, now the vestibule of a theatre, but originally part of a merchant's house, has walls of ashlar and flint, and tiled roofs. It is certainly of the late 15th century although the precise dates proposed by Edward Duke relate to another of John Hall's properties. (fn. 28) It occupies the N.W. corner of a large plot (210 ft. by 60 ft.) which extended E. to Catherine Street and S. as far as the garden of Nos. 26–8 Catherine Street (191).

In 1455 John Hall already held property on the Ditch (New Canal) and in Carternstrete (Catherine Street). (fn. 29) The hall, built some years after this date, stands testimony to his success as a merchant. (fn. 30) In 1669 Aubrey wrote 'as Greville and Wenman bought all the Coteswold, soe did Halle and Webb all the wooll of Salisbury plaines'. Hall was deeply involved in the famous dispute between the commonalty and Bishop Beauchamp. (fn. 31) He was mayor in 1450, 1456 and 1464–5, and parliamentary representative in 1460 and 1461; he died in 1479. His political aspirations appear to have been inherited by his son William, aged 24 in 1479, who was involved with Walter Hungerford and others in Buckingham's rebellion of 1483. (fn. 32) William became M.P. for Salisbury in 1487; his sister Christian (d. 1504) married Sir Thomas Hungerford (d. 1494). Stained glass decorated with heraldic roses and with the arms of Hall, Hungerford etc., was probably installed in the hall windows early in the reign of Henry VII.

Hall of John Hall

The axis of the hall lies at right-angles to New Canal. To the E., where two houses (186) now stand, there was formerly a courtyard entered from the street through a gateway with a pointed arch. (fn. 33) To the N., between the street and the end of the hall, there is a three-storeyed, 16th-century timber-framed building. From 1816 to 1819 the hall was part of the printing offices of the 'Wiltshire Gazette'. (fn. 34) In 1834 it was restored by A.W. Pugin and F.R. Fisher. The N. front, by Frederick Bath, was added in 1880. (fn. 35)

The E. elevation of the hall (Plate 59) is of ashlar and has casement-moulded windows of two and four transomed lights with cinquefoil two-centred heads. In the S. window, two lights below the transom are omitted to make room for a doorway with a moulded two-centred head in a square-headed casement-moulded surround. Further S. the ashlar elevation is two-storeyed, but the windows are modern. The W. wall of the hall is mainly of flint and rubble with some tile lacing courses and also with later brick patching. A blocked opening in the S. part of the wall has a four-centred brick head and is perhaps of the 16th century. The brick chimneybreast appears to be of the 19th century. A stone window set at a high level on the N. of the chimneybreast has two cinquefoil-headed lights and is evidently of 15th-century origin, but almost certainly is not in situ.

Inside, the hall has a roof of six bays with four archbraced collar-trusses springing from false hammerbeams at the ends and between each pair of bays, and with three intermediate trusses springing from carved angel corbels. There are three purlins on each side and four tiers of cusped wind-braces (Plate 83). The false hammerbeam brackets rest on wall-shafts set on carved stone corbels, some with human heads, others with angel busts bearing shields (the latter were probably painted in 1834 in repetition of the original coats of arms in the window glass). The fireplace, with an original stone chimneypiece decorated with a shield-of-arms of Hall and a merchant mark (Plate 90), is not certainly in situ.

Merchant Mark of John Hall.

A stone archway with a moulded four-centred head in the N. end of the hall is of 1834. The S. end has three modern doorways and, above, a cartouche-of-arms painted by Pugin. (fn. 36) An inscription records the restorations of 1834, when the building belonged to Sampson Payne, merchant of china and glass.

The window glass, extensively restored in 1834 by J. Beare, includes quarries inscribed 'Drede' in blackletter, the initials I and H, and shields-of-arms etc. as follows – E. windows, N. to S., upper lights: i Hall with estoil impaling merchant mark; ii (square) France modern and England with label of three points; iii (shield) France modern and England undifferenced; iv as i but with mullet in place of estoil; v Monthermer; vi Hall with estoil impaling Hall undifferenced; vii Campbell; viii ermine, a lion regardant or; ix ermine a lion or; x Fitzhugh. Lower lights: xi Hungerford; xii Montacute and Monthermer quartering Neville; xiii quarterly of seven, Beauchamp, Montacute, Monthermer, Neville, Clare, Warwick and Spencer (Ann Neville, wife of Richard III); xiv Hungerford with label impaling Hall with estoil; xv Hall (altered) impaling merchant mark; xvi See of Winchester impaling Montague (James Montague, Bp. of Winchester 1616–9); xvii red rose; xviii red rose superimposed on white rose, crowned. The W. window contains: i figure of man bearing banner with arms of France modern and England quarterly; ii shield charged with seated, chained and collared bear holding axe.

The ground-floor room at the S. end of the hall has reset heavy oak ceiling-beams with roll, hollow-chamfered and ogee-mouldings forming a ceiling of four square and two oblong panels. The first-floor room contains nothing notable.

The three-storeyed 16th-century house to N. of the hall has been much altered. The N. wall is entirely of 1880. In the lower storeys the E. and W. walls have stout original posts, but a gallery-like opening in the first floor is modern. The third storey has two original W. windows, each of four lights with ovolo-moulded oak mullions. The roof has three collared tie-beam trusses.

(186) Houses, pair, Nos. 13 and 13a New Canal, of three storeys with brick and tile-hung walls and tiled roofs, were built c. 1800. The symmetrical N. front, rebuilt c. 1970, was formerly of timber framework hung with mathematical tiles. Each upper storey had five bays of plain sashed windows, the central windows being narrower than the others, and false. Kingdon & Shearm indicate a central through-passage in the ground storey, now obliterated by a shop.

(187) Houses, three adjacent, Nos. 11, 9 and 7 New Canal, demolished in 1962, were three-storeyed with walls of brickwork and of timber framework hung with mathematical tiles; they dated in the main from the second half of the 18th century. The offices of William and Benjamin Collins, printers of the Salisbury Journal, had been on or near the site since 1748, (fn. 37) and in 1962 the newspaper still occupied No. 7 and the long back range of No. 11. The E. elevation had 18th-century doorways and sashed windows. The third edition of Naish's town plan, printed by Collins in 1751, names the site 'printing office'. During demolition the W. wall of No. 11 was found to be of mediaeval timber-framed construction on a plinth of rubble and ashlar.

(188) Houses, two adjoining, Nos. 2 and 4 Catherine Street, three-storeyed, with rendered walls and slate-covered roofs, are of timber-framed construction and perhaps late mediaeval in origin, but they were remodelled early in the 19th century. Above modern shop windows the N. and E. elevations have plain sashed and casement windows symmetrically arranged.

(189) Houses, three adjoining, Nos. 6–10 Catherine Street, are four-storeyed with brick walls and tiled roofs and were built late in the 18th or early in the 19th century. In each, the E. front is of two bays with modern shop windows at ground level and plain sashed windows above. Nothing noteworthy remains inside.

(190) Houses, two adjoining, Nos. 12 and 14 Catherine Street, now combined, are of three storeys with timber-framed walls hung with mathematical tiles and with tiled roofs. They were built during the first half of the 18th century, but were refronted early in the 19th century. The stairs are of the 19th century.

(191) Houses, two adjacent, Nos. 26 and 28 Catherine Street, are three-storeyed and have walls, probably of light timber framework, hung with mathematical tiles; the roofs are tiled and slated. The houses date from early in the 19th century and the E. front of No. 26 has first and second-floor balconies with wrought-iron railings, and a projecting first-floor window.

(192) Cottage, No. 30 Catherine Street, is two-storeyed with an attic and has timber-framed walls hung with slates and mathematical tiles, and a tiled roof. It is of the 16th century. The first floor is jettied on the S. side.

(193) Houses, originally two, Nos. 32 and 34–6 Catherine Street, now three shops, are two-storeyed with brick walls and tiled roofs. They were built about the middle of the 18th century. Originally the E. fronts were continuous, the N. house having two and the S. house four plain sashed windows in the upper storey, with a continuous modillion cornice and plain parapet above. The lower storeys have been obliterated by modern shops. The S. house was divided into two parts after 1880 (O.S.).

(194) Warehouse, No. 38 Catherine Street, is of two and three storeys with brick and timber-framed walls and tiled roofs. The three-storeyed brick building on the E. is of the 19th century. Behind, a six-bay E.–W. range with rough-hewn timber-framed walls and with braced and collared tie-beam roof trusses is probably of 16th-century origin.

(195) Building, No. 40 Catherine Street, demolished c. 1970, was of two storeys with an attic and had timber-framed walls hung with mathematical tiles. The 19th-century E. front masked a building which retained elements of a 14th-century rafter roof with a collar purlin.

(196) House, No. 46 Catherine Street, of three storeys with brick walls and slated roofs, appears to be of the 18th century.

(197) House, No. 50 Catherine Street, of two storeys and an attic, has timber-framed walls and a tiled roof and probably is of the 16th century. The E. front is jettied at the first floor. In the 19th century a mathematical tile facade was added, with plain sashed windows at first-floor and attic levels.

(198) Cottages, pair, Nos. 52–4 Catherine Street, demolished c. 1970, were originally two-storeyed with attics and had timber-framed walls and slate-covered roofs; they were of the 16th century. In the 19th century the E. fronts were heightened to three storeys and rendered, and the jettied first floors were under-built.

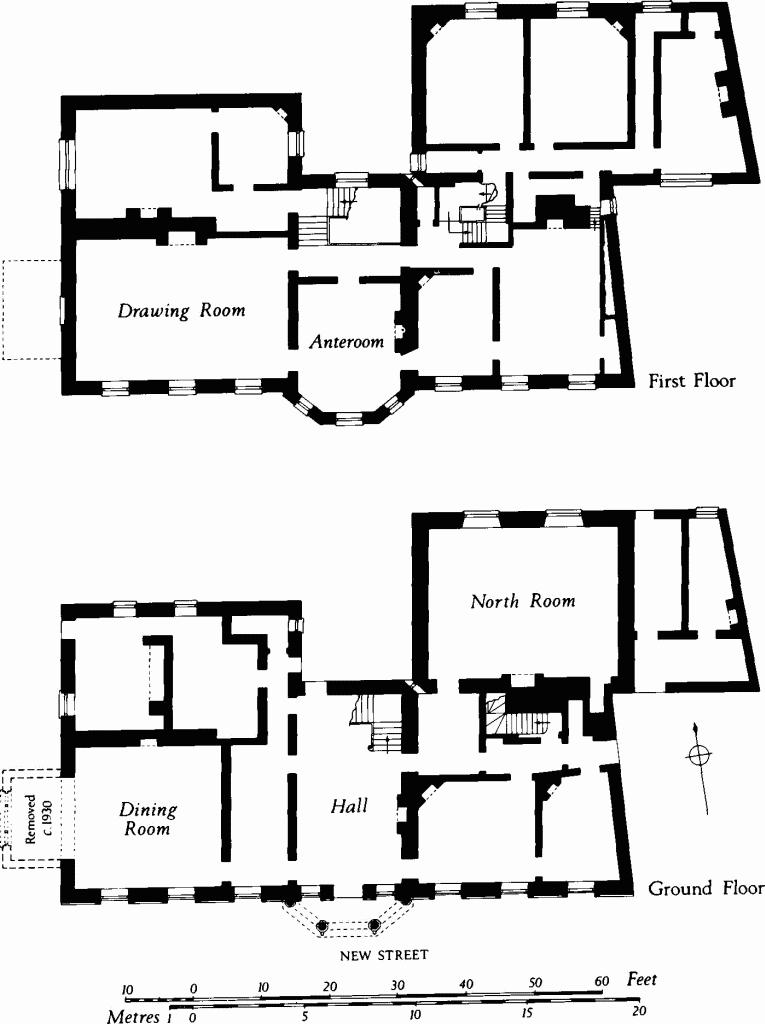

(199) 'The Hall' (O.S., 1880), No. 4 New Street, now offices, is of two storeys with attics and has brick walls with stone dressings, and tiled roofs; the E. wall contains mediaeval flint and tile work and 17th-century brickwork. Built soon after the middle of the 18th century for Alderman William Hussey, (fn. 38) a wealthy clothier, on the site of the old Assembly House, (fn. 39) it is the second largest dwelling house in Salisbury, being surpassed only by The College (14). Hussey represented the city in Parliament from 1774 to 1813. His great-grandfather, Robert Hussey (d. 1710), also alderman of Salisbury, was descended from the Husseys of Shapwick, Dorset.

The symmetrical S. front (Plate 76) has a projecting central bay with a porch in the lower storey and bowwindows above. In the three-bay flanking elevations the window architraves of the lower storey are designed as if for doorways.

(199) The Hall, No. 4 New Street.

Inside, the hall fireplace has a pedimented stone chimneypiece. The main stairs have stone steps with cyma-shaped soffits, a plain balustrade with twisted iron newels and a mahogany handrail. The large North Room, added later in the 18th century, has walls and ceilings enriched with neo-classical plasterwork. On the first floor the drawing room has bolection-moulded panelling in two heights and a high coved ceiling which rises into the attic; the chimneypiece (Plate 94) has a rococo frieze panel The anteroom has panelling with fielded centres and a rococo chimneypiece of pinewood (Plate 94). Several other rooms have carved wood chimneypieces and enriched plaster ceilings.

(200) House, No. 8 New Street, demolished in 1967, was three-storeyed and had brick walls and a slate-covered roof. It dated from the first quarter of the 19th century. The S. front was symmetrical and of three bays.

(201) House, No. 42 New Street, demolished in 1964, was of two storeys with attics and had brick walls and tiled roofs. The W. part of the building, of mid 18th-century date, had an asymmetrical S. front of seven bays. Towards the end of the 18th century cottages were added at the E. end of the range and other additions were made on the S.E.; the cottages were subsequently incorporated in the house. Inside, the stairs had plain balustrades and turned newel posts. The S.W. room on the first floor had fielded panelling.

(202) Cottage, No. 76 New Street, demolished in 1964, was two-storeyed with timber-framed walls and a tiled roof. Of 16th-century origin, the interior had been destroyed to make a garage, but the roof retained collared tie-beam trusses with queen-struts.