An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in the County of Cambridgeshire, Volume 2, North-East Cambridgeshire. Originally published by Her Majesty's Stationery Office, London, 1972.

This free content was digitised by double rekeying. All rights reserved.

'Sectional Preface', in An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in the County of Cambridgeshire, Volume 2, North-East Cambridgeshire(London, 1972), British History Online https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/rchme/cambs/vol2/xxv-lxvi [accessed 30 January 2025].

'Sectional Preface', in An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in the County of Cambridgeshire, Volume 2, North-East Cambridgeshire(London, 1972), British History Online, accessed January 30, 2025, https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/rchme/cambs/vol2/xxv-lxvi.

"Sectional Preface". An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in the County of Cambridgeshire, Volume 2, North-East Cambridgeshire. (London, 1972), British History Online. Web. 30 January 2025. https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/rchme/cambs/vol2/xxv-lxvi.

In this section

CAMBRIDGESHIRE II, SECTIONAL PREFACE

Geographical Setting

This Inventory covers an area of 46.3 square miles (112.2 sq. km.) N.E. of the City of Cambridge and includes the south-eastern edge of the Cambridgeshire fenlands. The area is bounded on the N.W. by the River Cam, on the E. by the county boundary with West Suffolk and on the S.E. by the Icknield Way, now the A 11 road. The N.W. part is flat peat fen or former fenland between 4 ft. and 16 ft. above O.D. and now artificially drained throughout. Over much of this land the original peat has disappeared as a result of drainage and cultivation and remains only as a wide strip adjacent to the River Cam. Elsewhere the underlying Gault Clay and Lower Chalk are now exposed. The S.E. half of the area consists of rolling chalk-land (Lower and Middle Chalk) rising gently to the S.E. to a maximum of about 200 ft. above O.D. It is dissected by broad dry valleys. Only in the S.W. on the low-lying ground near Teversham and Bottisham is there any surface drainage. Elsewhere springs break out at, or close to, the former fen edge.

Village Morphology

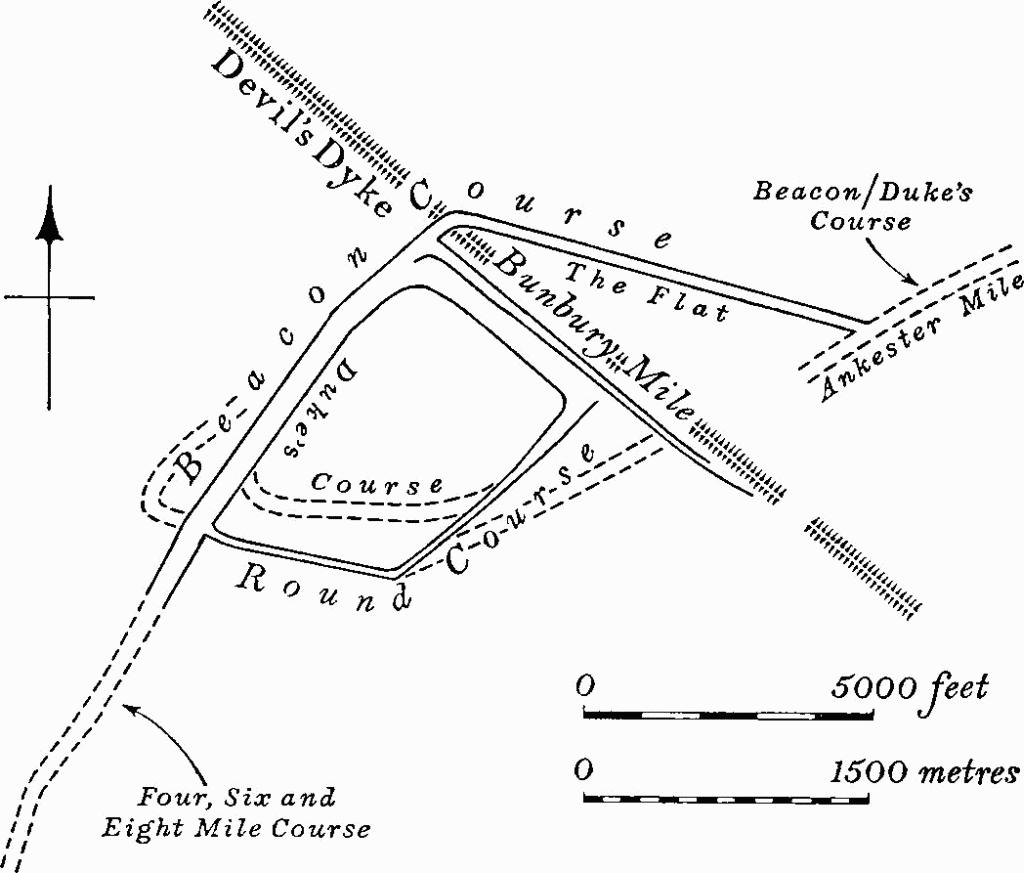

The larger settlements in the area are generally linear villages strung out along a main street with little development along back lanes. Additional means of communication may have been by way of waterways parallel to the main street. At Horningsea, Teversham, Lode, Bottisham, Swaffham Bulbeck and (West) Reach there is evidence of small greens along the main street which may or may not be the original centres. Most of these have been to some degree encroached upon by buildings. At Reach the destruction of a length of the Devil's Dyke to produce a large rectangular green was a secondary stage in the development of the village.

Parish Boundaries

Until recent boundary revision, the greater part of the area was occupied by the elongated parishes of Bottisham, Burwell, Swaffham Bulbeck and Swaffham Prior, stretching between the River Cam and the line of the Icknield Way, over six miles long and often less than a mile wide. The land thus defined provided each village with fenland as well as dry chalkland. The use of the Devil's Dyke, Reach Lode, Swaffham Bulbeck Lode and part of Bottisham Lode as physical boundaries suggests that these features predate the establishment of the parishes.

Interpretation of the boundaries of the parishes in the S.W. of the area presents difficulties, but it is probable that Stow cum Quy parish was once part of Little Wilbraham to the S. and that the two parishes formed another strip-shaped unit similar to those in the N.E., indicating that both Stow and Quy were originally secondary settlements of Little Wilbraham. The interlocking boundaries of Fen Ditton and Horningsea also suggest that they once formed a single unit. The position of the northern section of the Fleam Dyke in this context is also significant (pp. 144–7); it is possible that the area behind it on the N. was some form of land unit before the historic period.

In the medieval period Stow cum Quy and Swaffham Prior parishes were each divided into two ecclesiastical parishes possibly without distinct internal boundaries; no boundaries are traceable today.

Communications

Roads

No Roman roads are known in the area, although the S.E. part is crossed by the so-called Icknield Way which was undoubtedly used both in prehistoric and Roman times. Terms such as 'way' or 'track' tend to be misleading, for until the early 19th century all that existed was a zone of communication across open chalk downlands between the permanent arable land of villages to the S.W. and N.E. Across this zone was a network of trackways used by local and long-distance traffic (see Chapman's Map of Newmarket Heath, c. 1768). These various routes were formalised into one clearly-defined road (the modern A 11) as a result of the gradual late 18th- and early 19th-century Parliamentary enclosure of the open downlands, although some of the other tracks became fenced roads at the same time. An overgrown lane, known as the Street Way in Bottisham and Swaffham Bulbeck parishes, is a survival of one of these fenced roads.

The most important roads during the medieval period, apart from the Icknield Way which was by then already a major route, were probably those from Cambridge to Mildenhall (Suffolk) via Burwell, and from Cambridge to Newmarket. The precise route of the medieval fen-edge road is difficult to trace. It appears to have left the modern Cambridge-Newmarket road (A 45) S. of Fen Ditton and run northwards to that village whence it turned S.E. along the N. section of Fleam Dyke, crossing Quy Water and entering Quy village 100 yds. N. of the present Newmarket road. It then ran to Swaffham Bulbeck, via Lode, either on the line of the existing fen-edge road or through Bottisham village and park. Its line N.E. of Swaffham Bulbeck is not clear; a confusing number of parallel tracks is shown on Chapman's Map (c. 1768), S.E. of Swaffham Bulbeck and Swaffham Prior, but the road certainly passed through the surviving gap in the Devil's Dyke on its way to Burwell.

Until the 18th century the Cambridge to Newmarket road followed a different line from that which it now takes. The section between Quy Bridge and the S.E. end of Bottisham village had not been built by 1719 (E. Hailstone, History of Bottisham, C.A.S. 8vo. Publ. (1873) Appdx. III, 150–2); also, the present road cuts across the common field furlongs recorded in Stow cum Quy in 1827 (map in Quy Hall). These facts indicate that the medieval route to Newmarket was along the fen-edge road as far as Lode where it turned S.E. through Bottisham village and climbed onto Newmarket Heath approximately on the line of the present main road.

During the medieval period the roads linking the port at Reach with Swaffham Prior and Burwell must have seen much traffic. Other medieval roads were those from the fen-edge villages across the chalk downs to the forest-edge villages in the S.E. of the county. These were either abandoned or realigned at the time of enclosure and the resulting long straight roads or lanes with sharp changes in alignment, and with wide verges, are now the characteristic form of road in the area. Other changes to existing roads include the diversion of the Bottisham-Swaffham Bulbeck road, when Bottisham park was laid out, (Bottisham (4)) and a small alteration to the road past Swaffham Prior House in the late 19th century which was also connected with emparking (Swaffham Prior(4)).

During the 18th century the Cambridge-Newmarket road was improved by Turnpike Trusts. The section from Cambridge to the sharp bend in the present A 45 near Four Mile Stable Farm in Swaffham Bulbeck parish was taken over by the Godmanchester-Newmarket Heath Turnpike Trust in 1745. It is likely that this Trust was responsible for the construction of an entirely new road from Fen Ditton to Bottisham, now represented by the A 45. The road from the end of the Godmanchester-Newmarket Heath Trust section to the Devil's Dyke was not altered until 1775 when the Newmarket Heath Turnpike Trust, set up in 1763, acquired it. The old road alignment was abandoned and a new one, exactly straight, laid out with an overall width of 100 ft. The subsequent enclosure of the adjacent heath in the 19th century reduced parts of it to 70 ft. in width (C.R.O., Minutes of the Newmarket Heath Turnpike Trust).

Along the Cambridge-Newmarket road are several milestones, numbered from Cambridge, of which six are within the area of the Inventory. All are apparently of Jurassic limestone, 1 ft. square and about 2½ ft. high with rounded tops; one is broken. The fourth stone from Cambridge is inscribed 'IV Miles' on the back, and the others were originally likewise inscribed but have been defaced; all have now been set back to front and re-inscribed with crude Roman numerals. They probably date from the 18th century.

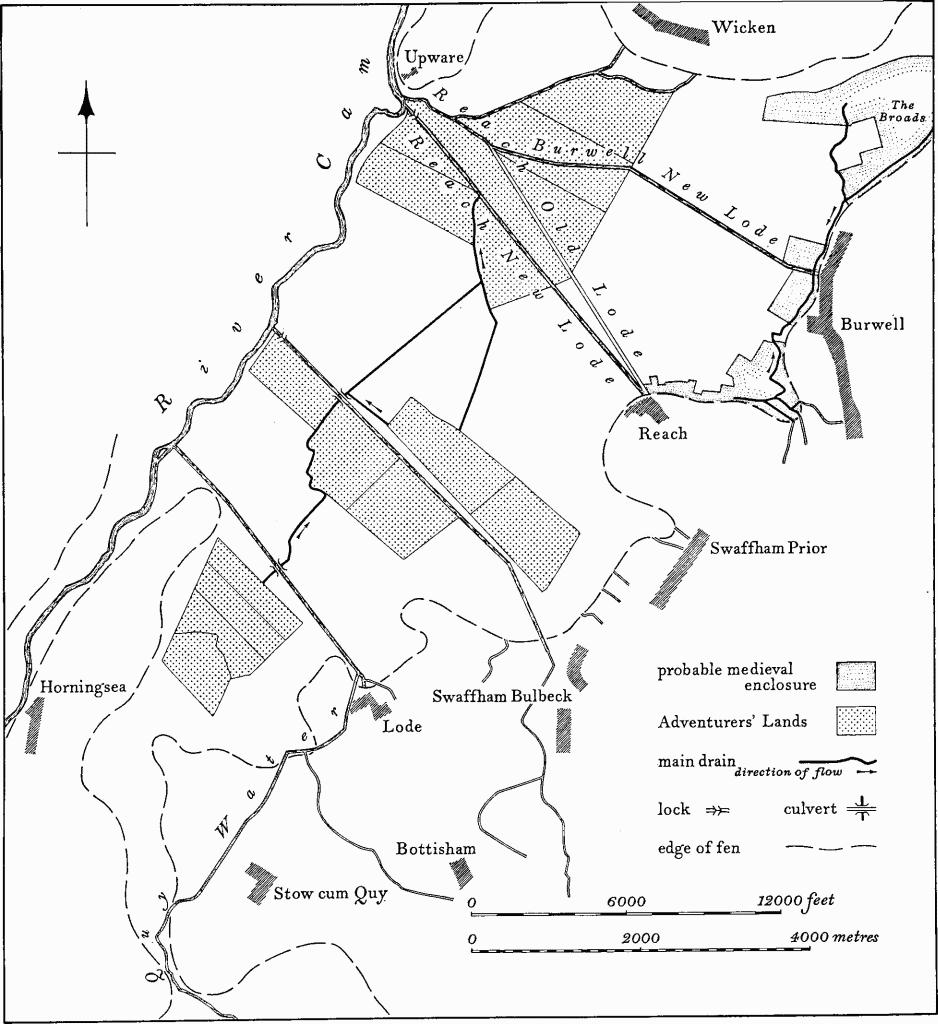

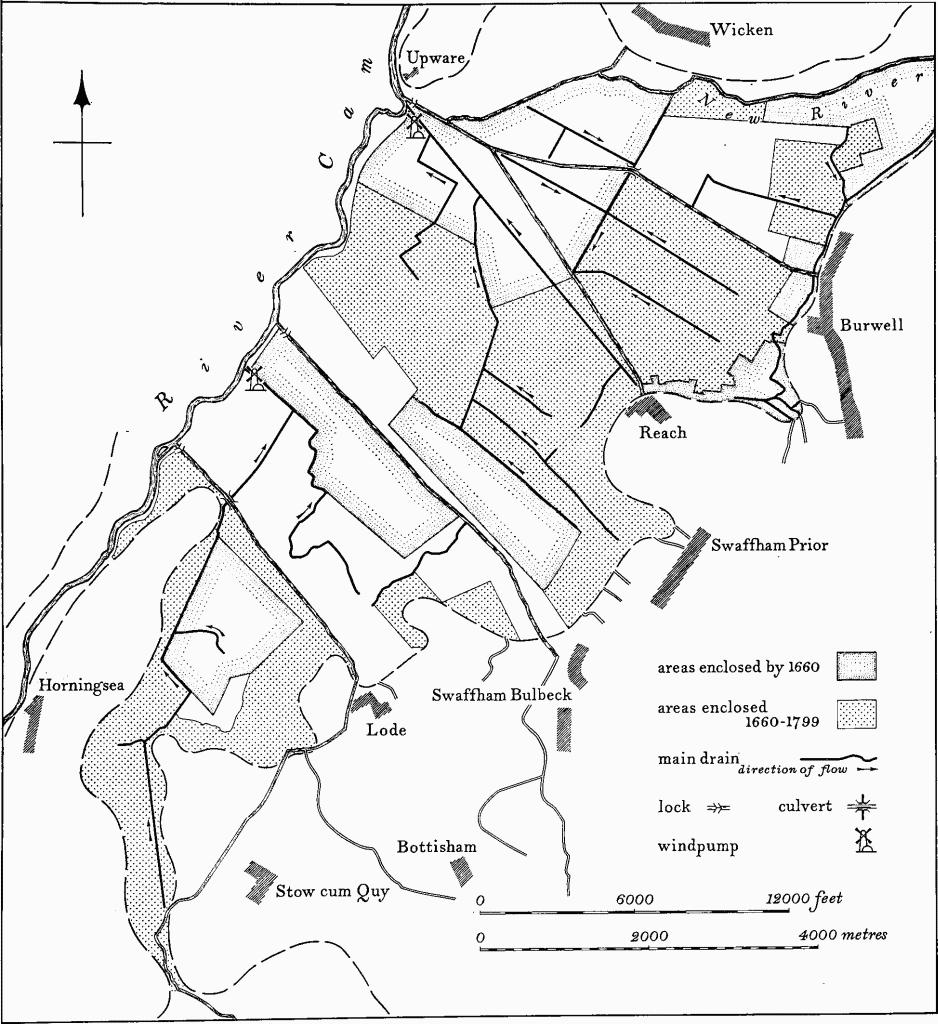

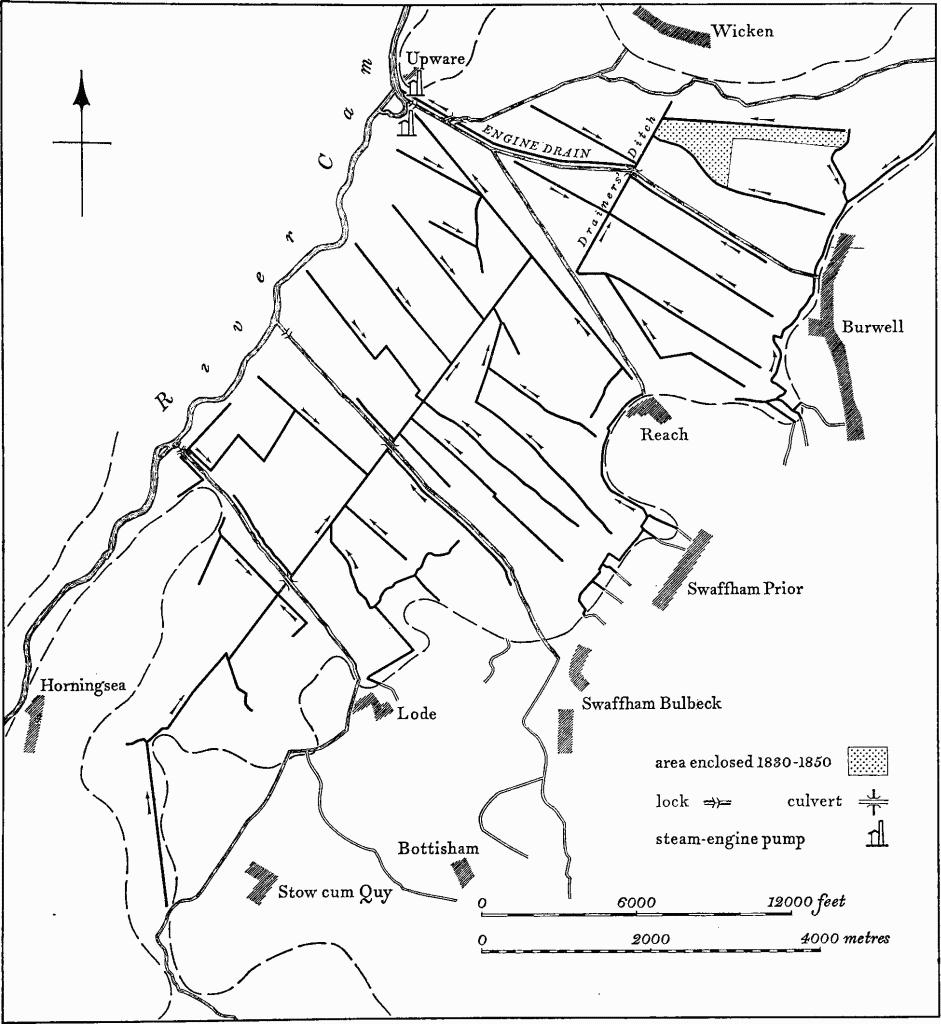

Waterways

The lodes, or navigable canals, which link the uplands with the River Cam have a complicated history. With the exception of Burwell Lode which is probably 17th-century, they are almost certainly of Roman origin. All were used for waterborne traffic both within the area and beyond it. Although long-distance traffic had declined by the end of the 19th century local traffic thrived until the fen roads were made up during the Second World War (see p. lxv, Fen Trade).

Railways

A short section of the Cambridge branch of the Newmarket-Chesterford Railway, constructed in 1848, passes through the S. part of Teversham parish, but the original buildings associated with it survive only in parishes outside the Inventory area (C.A.S. Procs., XXXI (1931), 1–16). The nowabandoned Cambridge-Mildenhall line, built in 1884, passes across the area along the fen edge. All the stations, with the exception of that at Burwell, as well as line-side cottages and bridges, still remain. The stations at Lode and Swaffham Prior, which are similar to others on the line, consist of a two-storey brick T-plan station house with a single-storey waiting room and office block attached. Quy station is a single-storey timber-framed and cladded structure.

Extractive Industries

The remains of a number of extractive industries of various dates have been recorded. Some, for example clunch quarrying and brickmaking, have been described briefly in the Inventory. Others which are either undated, post-1850 or of minor importance have not been listed. All these activities have left their mark on the landscape, but the following were perhaps the most extensive.

Coprolite Digging

The digging of coprolites (i.e. phosphatized shells, sponges, bones and nodules of clay) was an important industry in the county during the latter part of the 19th century. The coprolites are found at or close to the junction of Gault Clay and Lower Chalk and in the Lower Greensand over a wide area of central Cambridgeshire in beds about 1 ft. thick. They were dug out, washed, crushed and treated with sulphuric acid to produce a superphosphate powder for use as a fertilizer. The industry lasted for about 40 years from 1850 and then declined as a result of the agricultural depression of the late 19th century, the exhaustion of the most easily-worked areas and the import of cheap fertilizers from abroad. The extraction of the coprolites was carried out by digging a trench a few yards wide along one side of a field and removing the coprolites, which usually lay 15 ft. to 20 ft. below the surface. The digging then continued across the field in strips, the diggers back-filling the trenches as they went, until the field was left with a bank of earth at one end and a deep trench at the other. The washing of the coprolites was carried out near the diggings either in annular water-filled pits or within the centre of annular earthen mounds or 'hills'.

Coprolites were extensively dug in the area along the fen edge from Horningsea to Burwell. Air photographs indicate that at least 3000 acres were worked. The remains of long mounds and trenches as well as the washing 'hills' are traceable in many places along the fen edge in Horningsea, Stow cum Quy and Lode. Air photographs show that the rows of excavated trenches produced a pattern similar to that of ridge and furrow, for which it is sometimes mistaken (V.C.H. Cambs. II, 367–8).

Gravel Digging

Two types of remains resulting from gravel digging have survived. Extraction of gravel along the River Cam in Horningsea and Fen Ditton parishes, probably in the 18th and 19th centuries, has left a number of small pits, but more extensive remains exist on the chalklands in the extreme S. of Swaffham Bulbeck parish where a number of pits and irregular trenches up to half a mile long are still visible in modern arable fields. These are the result of digging gravels overlying the chalk; their date is unknown, but they are certainly earlier than the 19th century.

Clay Digging

A number of large pits along the fen edge or adjacent to the Lodes have been noted in the Inventory (Burwell (137), Lode (32), Swaffham Prior (74)). These are clay pits resulting from the extraction of Gault Clay in the 19th century for rebuilding and repairing the banks of lodes and rivers, which protected the adjacent fens from floods. Most were owned by, or leased to, the Swaffham and Bottisham or the Burwell Drainage Commissioners, who carried out the work.

Brickmaking

The existence of the outcrop of Gault Clay along the fen edge allowed the growth of a small brickmaking industry. Late medieval and early 17th-century bricks were probably made from local clays, although the sources are uncertain. The bricks were fired to a deep red. In the 18th century small brickpits along the fen edge were operated on a commercial scale. Although Gault Clay was used, a variety of colours was produced, but from the mid 18th century onwards white brick was increasingly manufactured. The larger pits are all probably of the 18th and 19th centuries, e.g. Lode (37, 38), Horningsea (36) and Stow cum Quy (27). Most were abandoned by the late 19th century when large-scale commercial production elsewhere led to the import of cheaper bricks. Locally, large brick works on Burwell Fen started operation in c. 1900.

Clunch Quarrying

Clunch, a hard chalk, capable of being used as ashlar and for carving, has been an important building material from the Roman period onwards. In the area there are many small quarries, especially at Burwell (148) and Swaffham Prior (80); much larger quarries have been noted at Reach (38). There is documentary evidence for the use of clunch from Burwell and Reach throughout the medieval period in the Cambridge colleges, Cambridge Castle, Ely Cathedral and local churches. However, the area of extant quarries in Burwell is small suggesting that much of what was called 'Burwell' stone in medieval documents came from quarries further afield; it was perhaps a term for material which passed through the port at Reach, then partly in Burwell parish. Most of the existing quarries at Burwell were worked after 1817. Clunch rubble was dug extensively for road mending, and from the late 17th century for building and repairing the fen flood-banks, and for general building purposes until the end of the 19th century (V.C.H. Cambs. II, 365–6).

Building Materials

Ecclesiastical Use

In the 12th century and probably earlier (see Horningsea), the predominant material for church walls was rubble with dressings of limestone. In order to preserve a traditional and generic term without inferring a precise provenance, this Jurassic limestone has been described in the inventory as 'Barnack'. The rubble consisting either of field stones (glacial erratics) or flints, or a combination of the two, is usually laid in rough courses and sometimes diagonally. 'Barnack' was also used as ashlar as demonstrated by the reused blocks in the chancel walls at Horningsea (Plate 15); these stones suggest re-use from a 12th-century chancel with ashlared walls in the manner employed for the chancels of Coton and the Stourbridge chapel, Barnwell (R.C.H.M., W. Cambs., 59; Cambridge, 298). Reused moulded pieces of 'Barnack' are often found. The use of local clunch was widespread, appearing in the late 12th century at Horningsea as worked stones for octagonal piers in conjunction with limestone for the capitals and bases. The size of clunch ashlar blocks is noticeably larger in the late medieval period than previously; it never completely replaced the use of rubble even in the richer foundations such as Burwell (Plate 32). To avoid damage to the soft clunch, lower courses and bases are often in limestone (e.g., the screen at Bottisham and the nave-piers at Burwell).

The use of different materials for decorative effect has been noted at Bottisham where knapped flint appears at an early date and at Swaffham Prior (St. Cyriac) where, at the end of the 15th century, the plinth of the tower is enriched with chequerwork of red brick and limestone, and the parapet with flint flushwork (Plate 34). The knapped flint crosses in the faces of buttresses at Fen Ditton (Plate 22) show that some wall surfaces were left unplastered while others, such as the S. porch at the same church, must have been rendered in view of the random selection of material of which it is constructed. Carefully-coursed knapped flint was used internally for the lower part of the wall at the priory at Swaffham Bulbeck (Plate 71) and there is no indication that it was plastered.

The relation between the form of church roofs and the covering material has been discussed in West Cambridgeshire (p. xxxii). In the present area, evidence for steeply-pitched roofs at Horningsea (late 12th-century), Bottisham, Fen Ditton and Swaffham Bulbeck (all 13th-century) is found in the survival of redundant weathercourses on the east face of west towers; the 14th-century chancel roof at Fen Ditton is preserved in its steeply-pitched form. These roofs were probably designed to take thatch, the thickness of which is shown by the distance of the roof from the weathercourse, or by the height of gable parapets. The use of lead, making possible roofs of negligible pitches, influenced the concept of shape and proportion in the architecture of the later period, as typified by Burwell church.

Except for timber-framed Independent chapels at Bottisham (2) and Swaffham Prior (3), ecclesiastical buildings of the early 19th century, whether Established or Nonconformist, in the Gothic style or the Classical, are in white gault brick with slated roofs.

Secular Use

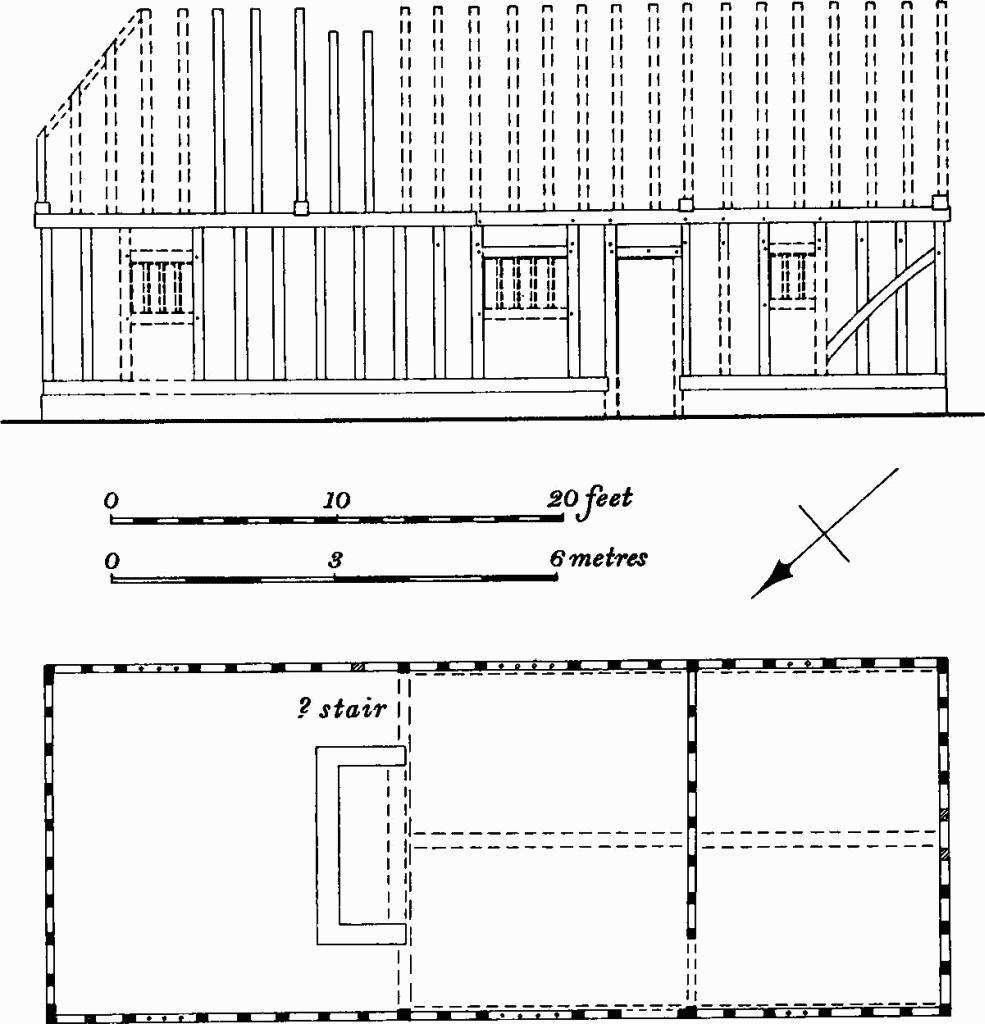

North-east Cambridgeshire, as distinct from the eastern part of the county and the adjacent clay-covered areas of Essex and Suffolk, is not a wooded area and the Domesday survey does not suggest that it was forested to any degree at that time. Local reserves of timber could scarcely have been sufficient for the needs of building from the Middle Ages onwards. An indication of the quantity required in the construction of a three-roomed house of the 17th century may be had from an analysis of such a house at Swaffham Prior (8) (Fig. 1) where it was found that about 79 oak trees, ranging in girth from 2½ ft. to 5 ft., would have been required. This represents the annual production to be expected from at least 70 acres of woodland managed in the traditional manner of rotational cropping, or the total clearance of about 1½ acres. Swaffham Prior is in an area singularly destitute of oaks, the nearest ancient woods being in Stetchworth and Westley Waterless some six miles away. Oak was the predominant material until the 18th century when softwoods were commonly used. In the 18th century the combination of oak and softwood in a single building has been recorded in a number of instances. Although fir and other timbers are known to have been brought into the district no documentary evidence has been found to indicate the extent to which this imported material was used locally. However the trading establishment of Thomas Bowyer at Swaffham Bulbeck (39) was doubtless the source of much softwood used in the immediate area in the 19th century, particularly for the standardised houses built by Bowyer for his workfolk in the early 19th century.

Local supplies of clunch and brick proved an alternative or supplement for timber. For major buildings of the 14th century clunch was employed (e.g. the range of lodgings at Burwell (5) and the Biggin at Fen Ditton (5)), but in the 16th and 17th centuries its secular use became somewhat more general, perhaps when demands for church-building had ceased; the early 16th-century wing at The Hall, Swaffham Prior (21) and the large early 17th-century house at Burwell (41) are examples. From this time until the 18th and 19th centuries clunch walling was mostly rubble with scarcely larger stones for quoins; carefullyworked clunch was confined to mullioned and transomed windows, door heads and jambs and similar features. In the 19th century the clunch blocks were often large and well-squared (e.g. barn at Swaffham Bulbeck (20)) although clunch rubble continued to be used for side walls of houses (e.g. Burwell (50)). In this later period the use of clunch, though widespread, was generally for inferior purposes such as for boundary walls (Swaffham Prior (30)), barns (Burwell (67)), windmills (Burwell (103)) or the core of brickfaced buildings (windmill at Swaffham Prior (32), (Plate 116); with these walls white brick quoins, plinths and copings were customary.

Fig. 1 Swaffham Prior

(8) Elevation and plan showing timber construction before alteration

Red brick was used extensively during the 17th and 18th centuries, continuing to a lesser degree after the middle of the 18th. The Hall Fen Ditton (2), (Plate 82), the Old Rectories at Fen Ditton (4) (Plate 93) and Swaffham Prior (6) (Plate 93) serve as examples. Mottled red and yellow bricks were commonly used from the beginning of the 18th century in conjunction with a style of brickwork which employed blind recesses, platbands or occasional diapering, to decorate wall surfaces (e.g. Bottisham (20), Fig. 20; Swaffham Bulbeck (39), Plate 102). A very narrow brick, often yellow or of the mottled variety, continued well into the 18th century. These yellow bricks were used in the construction of chimney stacks usually with the addition of red brick quoins. A similar combination of yellow and red brick, arranged alternately, occurs in platbands (e.g. Burwell (76)).

White or cream-coloured brick first appears in the mid 18th century at Swaffham Prior House, Swaffham Prior (4), a few years after the introduction of that brick into Cambridge. In the late 18th and early 19th centuries white brick became associated with the villa style of architecture of which there are numerous examples in the area, particularly large farm houses (Plate 113) and parsonages (Plate 94); smaller houses and those in terraces were also built in white brick at this time, but when the gabled roof was retained for such buildings a more traditional stylistic appearance is evident (e.g. Swaffham Prior (14), Fig. 115). Pumping stations were also constructed in white brick; that listed as Burwell (139), built in 1841, has a number of such bricks stamped 'Drain', presumably indicating a special consignment exempt from brick tax; in 1849–50 similar bricks were supplied by William Fison of Horningsea whose account for £518 was still outstanding in 1854 (Swaffham Prior (78); Swaffham and Bottisham I.D.B. Minutes).

For the smaller houses before the 18th century roof-covering of thatch was the normal practice which continued into the 19th century; the introduction of tiles or pantiles for small and medium-sized houses was gradual after the early 18th century, often as a replacement of thatch. Mansard roofs were frequently covered with pantiles on the flatter upper slope and plain tiles on the lower (Plate 110). Slate, which made its appearance at the end of the 18th century (e.g. Bottisham Hall, Bottisham (4)), was imported from Wales and is recorded as passing through the trading establishment at Swaffham Bulbeck (39) in the early 19th century.

Raw material for clay bat or lump was apparently obtained indiscriminately and manufactured as local needs required; it is recorded that one John Cornell was instructed by the Swaffham and Bottisham Drainage Board to desist from making clay lumps out of mud from the ditch belonging to their lands which he occupied in Quy Fen (Swaffham and Bottisham I.D.B. Minutes, 9 July 1838). The bats seldom went beyond their use in smaller buildings, outhouses and small barns; white brick plinths were usual. No clay bat walling has been found dating from before c. 1800.

Earthworks

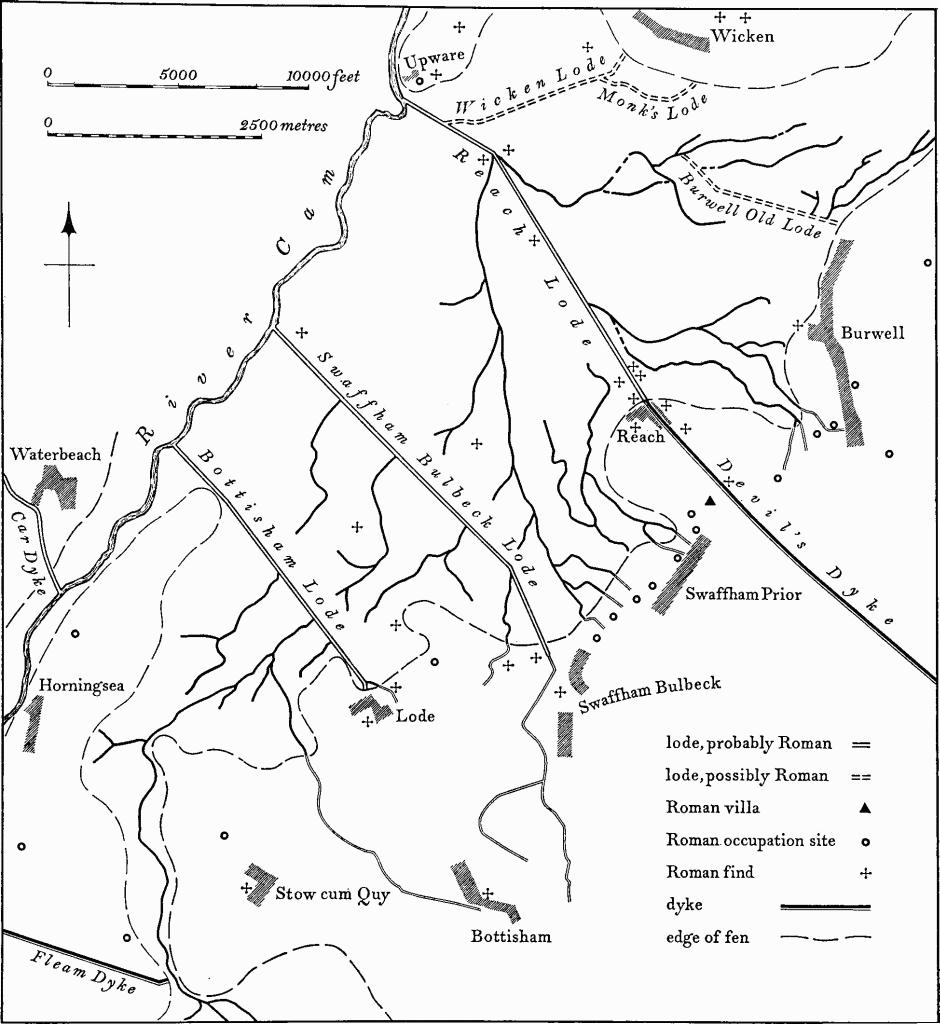

Prehistoric and Roman Settlement (Fig. 2)

Evidence for prehistoric occupation of the area is slight. No sites of settlements are known for certain and only chance finds and burial sites have been recorded. Two important collections of finds are from the fenlands (Burwell (121) and Swaffham Prior (60)). At both, the concentration of finds over relatively small areas suggests permanent occupation. These finds include flint tools of Mesolithic form as well as flint, stone and bronze implements of the Neolithic and Bronze Ages. Other tools of the same kind have been found elsewhere in the fens or along the fen edge, including three Bronze Age hoards.

Before the introduction of air photography the distribution of Bronze Age finds was considered to be in areas separate from the burial sites attributable to the same period, in that most of the known round barrows lay on the higher points of the chalklands whereas the finds came from the fen edge. Subsequently, air photography has revealed the sites of a large number of barrows scattered broadly over the lower slopes of the chalk. Over 50 round barrows are listed in the Inventory, but probably many more originally existed. Many are known to have been destroyed without record during 19th-century enclosure and by the subsequent ploughing of open chalkland. Others were probably removed at earlier periods as agriculture advanced up the hillsides. Of the known barrows none, with the sole exception of that on Allington Hill (Bottisham (49)), is sited on a promontory. Many are on hill sides, low ridges or false crests, and some in or near valley bottoms. Almost half the barrows listed in the Inventory lie together on relatively high ground around Upper Hare Park and are described as the Hare Park Group (Bottisham (47–55) and Swaffham Bulbeck (65–75)). They conform to no obvious pattern.

The barrows listed have not been scientifically excavated and the records of finds from them are of limited value. The long mound (Swaffham Prior (60)), now almost destroyed by ploughing, is of some interest as it might be a Neolithic earthen long barrow. Apart from a few chance finds and two possible settlements (Reach (27) and (28)), nothing is known of Iron Age occupation of the area.

Fig. 2 Distribution of Prehistoric and Roman Remains

a Prehistoric Round Barrows and Ring Ditches b Roman Settlement sites

A particular feature which occurs in the upper parts of the chalklands and which, though undated, presumably belongs to the prehistoric or Roman period, is the group of the linear ditches around Allington Hill (Bottisham (57, 58)). Similar earthworks exist outside the area in Balsham and Fulbourn parishes (C.A.S. Procs. LXII (1969), 31–2), but their date and function are problematical. (For a list of prehistoric finds see V.C.H. Cambs. I; for subsequent discoveries see maps in C.M.; other finds from the fenlands in private hands have not been catalogued; see also Fox, A.C.R.)

Recent work has revealed a number of Romano-British sites in the area. The present evidence (Fig. 2b) indicates a distinct concentration on or near the fen edge, especially in Burwell, Reach and Swaffham Prior. However, many of the sites in Burwell and Reach have been discovered by detailed work in certain localities and are probably not representative of the whole area. Apart from one site (Bottisham (56)), the upper parts of the chalklands are without Roman settlement. This fen-edge settlement is likely to be connected with the apparently contemporary system of lodes or navigable canals which link the chalkland with the River Cam and ultimately with the Car Dyke. These lodes have been included in the Inventory under Medieval and Later Earthworks as they are now the result of changes and alterations during the historic period; however, there is little doubt that they originated in the Roman period as a complex system of canals (see p. lv).

The fenland of the area is devoid of settlement of this period, though many chance finds have been made. The validity of some of these may be questioned (see Lode (30)); Roman pottery found along the banks of Reach Lode could have been brought there in recent times in the clay and chalk used in repairing the lode banks.

None of the known settlements has been excavated scientifically, and most are known only from concentrations of pottery etc. The villa at Reach (30) was extensively dug into in the late 19th century and from the resulting plan it appears to be a typical corridor villa. However, the remains must be only part of a much larger group of buildings. Probably the most important site is that of the Horningsea pottery workings (Horningsea (29)), which not only produced evidence for kilns, but also indications of industrial activity over a wide area.

Medieval and Later Settlement, and Earthworks

The primary medieval settlements in the area, which are still the main centres of population, consist of a line of villages near the fen edge extending from Horningsea in the S.W. to Burwell in the N. E. The siting of the villages varies and only Swaffham Prior may be regarded strictly as a fen-edge settlement. For example, the N. end of Burwell is close to the former edge of the fens, but its original nucleus around the present church is on a low spur half a mile from the fens. Similarly, Swaffham Prior is almost half a mile from the fen edge; the original centre of Swaffham Bulbeck is nearly one mile and of Bottisham nearly two miles inside the chalklands. Fen Ditton and Horningsea are sited on the banks of the River Cam and not on the fen edge.

The siting of the primary villages at a distance from the fens is of significance, for there is evidence to suggest that some developed secondary settlements on the edge of the fens. The settlements of Lode and Long Meadow (now in Lode parish) are probably daughter settlements of Bottisham on the fen edge. Their names are first recorded in documents in the 12th and 13th centuries (Reaney, 'Place-names of Cambs.', 131–2). Bottisham also had a secondary settlement which was not on the fen edge and is represented by a group of sites in Bottisham park (Bottisham (61–67)). Although Commercial End, at the fen edge, is now physically part of the village of Swaffham Bulbeck, it was once separate from it; its earlier name was Newnham. The eastern half of the present village of Reach, formerly known as East Reach, appears to have been a secondary settlement of Burwell, and the other half, West Reach, was probably settled by people from Swaffham Prior. Similarly, Burwell in its present form is apparently the result of the amalgamation of the original nucleus near the church with two later settlements called Newnham and North Street near the fen edge. In Horningsea parish, settlements at Eye Hall, now deserted, and Clayhithe may also be secondary. It is also possible that both Stow and Quy, in Stow cum Quy parish, are secondary settlements of Little Wilbraham, to the S.E.

Habitation was confined to the primary and secondary settlements until the post-medieval period, the undrained fens to the N.W. and the extensive common fields to the S.E. preventing development. By the late 17th century isolated farms started to appear on the fenland of Swaffham Prior parish as the result of internal drainage but no buildings of this period remain. However, in the 19th century fen drainage and enclosure led to a number of isolated farms being established. On the chalklands, only the stables and warren at Upper Hare Park (Swaffham Bulbeck (1880)) on the former open downland date from before the 19th century. Parliamentary enclosure of all the common fields and downs resulted in the establishment of scattered farms.

Settlement remains

A few of the existing villages in the area have earthworks which indicate changes in the location, or reduction in size, of the settlement. The remains of the hamlet of Eye (Horningsea (33)) are worthy of note; later farming activities have mutilated the site to some extent, but most of the former road pattern is recoverable.

Moated sites

Twenty-one moated sites are listed in the Inventory and have been classified under the same system as those in West Cambridgeshire (pp. lxi–lxvi). Of the ten types classified there, only five are found in the present area. The types of moated site occurring in north-east Cambridgeshire are as follows:

Class A: Homestead moats

Group 1. Simple enclosures bounded by wet ditches with no associated enclosures:

(a) rectangular enclosures with an internal area of less than ½ acre.

(b) rectangular enclosures with an internal area of more than ½ acre.

Group 2 (a). Rectangular enclosures with attached enclosures of similar form bounded by wet ditches.

Group 3. None in N.E. Cambridgeshire.

Group 4. Rectangular enclosures bounded by wet ditches on two or three sides only.

Class B: Garden moats

Three of the moated sites, Bottisham (60), Burwell (41) and Swaffham Prior (5), are of Class A1(a); eight sites, Bottisham (62) and (63), Fen Ditton (5), Swaffham Bulbeck (78), Swaffham Prior (17), (27) and (71) and Teversham (10), are of Class A1(b); another eight sites, Bottisham (64), (65) and (68), Burwell (39), Swaffham Bulbeck (4), (16) and (17) and Swaffham Prior (70) are of Class A2(a). Only one belongs to Class A4 (Swaffham Prior (72)) and one to Class B (Bottisham (61)).

The relative numbers of these types differ considerably from those in west Cambridgeshire. In that area moats belonging to Class A1(a), i.e. those with small enclosures, are the most numerous; in the present area they are comparatively rare. The commonest types in north-east Cambridgeshire are those with relatively large enclosures (Class A1(b)) or with attached enclosures of moated form (Class A2(a)). Although the number of sites in the present area is insufficient for firm conclusions to be drawn, an examination of moated sites in parts of the county not covered by Commission inventories suggests that the smaller homestead moats and those with attached enclosures bounded by shallow ditches or low banks, or both, tend to be more common in the boulder clay areas; the larger moats and those with attached moated enclosures are more frequently found in the chalk areas, along the fen edges and in villages adjacent to the river. The existence of larger and more sophisticated homestead moats reflects a greater prosperity in the fen district during the medieval period than in those parts of the county on boulder clay.

Most of the moated sites listed lie within or close to existing villages and generally mark the site of a manor house or other substantial medieval dwelling. Only those in Bottisham Park, (61–65), are situated away from the village, indicating a separate medieval settlement whose name is unknown. These moats and those at Swaffham Bulbeck, (16, 17 and 78), are of interest in that they retain evidence of extensive and co-ordinated work of stream diversion to enable water to fill the ditches. Similar watercourses at Anglesey Abbey, Lode (3), also show an elaborate system of drainage associated with a monastic house.

Cultivation remains

Remains of medieval-type cultivation in the area are not extensive. Unlike west Cambridgeshire, little ridge and furrow survives, and that which does is probably the result of ploughing old enclosed fields as opposed to the common fields.

Traces of early cultivation show as long low sinuous ridges, still visible on the ground, but more clearly seen on air photographs. These appear to be the remains of headlands between individual furlongs in the former common fields. In Burwell (150), existing long ridges correspond exactly with the headlands shown on an early 19th-century map of the common fields.

Other earthworks

The most important medieval earthwork in the area is Burwell Castle, Burwell (132), which is closely dated to 1143 by documentation. The surviving remains show clearly that it was never completed (Fig. 44; Plates 2, 3).

A low bank round Upper Hare Park, Swaffham Bulbeck (80), is of interest in being the remains of the pale round an early 17th-century enclosure for keeping hares.

Devil's Dyke and Fleam Dyke, see p. 139.

Drainage remains, see p. liv.

Remains of fen trade, see p. lxv.

Ecclesiastical Buildings

In the ten parishes lying N.E. of Cambridge there are eleven ancient churches or chapels including those now in ruins and another (Swaffham Bulbeck (3)) which has been converted into a house. There are standing remains on two monastic sites, and a number of Nonconformist chapels. Of the parish churches that at Reach, of 1860, is partly on the site of the medieval building which is ruinous, and that at Lode is mid-Victorian. The church of St. Cyriac and St. Julitta, Swaffham Prior, is dilapidated except for the late medieval west tower. At Quy, the church of St. Nicholas had fallen into disuse by the late Middle Ages and the lesser church of St. Andrew, Burwell, stood until about 1772 having suffered some vicissitudes in 1652 when the 'slates' were removed for use on the new vicarage roof, only to be replaced immediately at the protest of the parishioners (C.U.L., University Register, 32.1). A private chapel which presumably existed at the bishop's palace at Biggin, Fen Ditton (5), does not survive. A former chapel is implied at the Hall, Fen Ditton (2), by squint-holes of 15th-century character in the east wall of an earlier parlour. A second chapel at Reach is known only through its dedication. The chapel in Bottisham Hall, demolished in the late 18th century, was described by Cole in 1743 (B.M. Add. MS. 5805, 15).

The churches are normally sited on the highest ground in the parish, and at Fen Ditton and Horningsea in particular the land falls rapidly between the churchyard and the nearby river to the west. The two churches at Swaffham Prior perch on the edge of an escarpment at the foot of which stretches fenland. At Stow cum Quy the village has moved northwards away from the church at Stow since the combining of the two parishes; at Teversham, settlement has developed south of the church which survives as almost the most northerly of the monuments in the parish.

The earliest ecclesiastical survival is at Horningsea. Although no part of the present structure can be attributed to the pre-Conquest period, a church of this date probably dictated the plan of the existing building. An aisleless nave with chancel and lateral porticus, or side-chapels, is indicated. Examples of such a plan, usually dated to the middle Saxon period, occur at Breamore and Deerhurst, and represent a stage in the development of the full cruciform plan found later at churches such as Stow, Lincolnshire, and Hadstock, Essex (for comparable plans see H. M. Taylor, 'Kentish Churches...', Arch. J. (1969), 194). The porticus at Horningsea were probably quite small, hardly more than 12 ft. wide internally, with comparatively narrow arches from the nave.

There is evidence exists for at least five churches of the 12th century (Burwell (two), Horningsea, Stow cum Quy, Swaffham Prior); a considerable part of four of these survives. Judged by the style of the narrow window openings the tower of Burwell is probably the earlier of the two remaining 12th-century towers, the other being St. Mary's, Swaffham. Prior. Although increased in height in the 15th century, the remains of the lower stages of the Norman structure at Burwell are sufficient to indicate a church of considerable size and elaboration (Fig. 28). On archaeological rather than stylistic grounds the chancel and west wall of St. Mary's, Swaffham Prior may, with the Burwell tower, belong to the first half of the 12th century (Plate 12); the extant walls suggest a church about 82 ft. long without a west tower, but the length of the aisleless nave is unknown. A nave without aisles of about the same date is indicated at Stow by the existence of a Norman window, but the size of the whole building cannot be ascertained (Fig. 83).

The 12th-century west tower of St. Mary's, Swaffham Prior, is adventurously designed; the octagonal upper stage is carried on squinch-arches above the lower rectangular stages (Plate 15). The forms of the windows are more advanced than those in the Burwell tower in that the jambs have external nook-shafts with capitals and bases, and heads enriched with roll-moulding. The treatment may be compared with the windows of the Stourbridge chapel, Barnwell, and of Coton church (R.C.H.M., Cambridge, 298; W. Cambs., 59) which have been ascribed to the mid 12th century; clearstorey windows with similar architectural details at Denney Abbey, Cambridgeshire, may be closely dated to the years immediately following the house's foundation in 1159. A quoin worked as an angle-shaft, as in the lower stage of the Burwell tower (Fig. 28), appears to be a feature which continued to the end of the century (R.C.H.M., W. Cambs., Orwell church, 189).

Cole's sketch of the ruined round tower of St. Andrew's church, Burwell, is too rudimentary for a date to be assigned to the building with certainty, but it was presumably a 12th-century structure (B.M. Add. MS. 5804, 119; Palmer, Inscriptions and Arms from Cambridgeshire, 267, Pl. VII).

Other churches contain fonts or architectural fragments indicating former 12th-century churches: at Bottisham there is a fragmentary square font-bowl enriched with chevrons, and a stone tympanum carved with a wheel cross in low relief; at Fen Ditton, hacked-back dog-tooth decoration is 12th- or early 13th-century. However the round-headed doorway recorded in the S. aisle of St. Cyriac's, Swaffham Prior, must have been reset (Plate 35). Diagonally-tooled ashlar was reused in the 13th-century chancel at Horningsea (Plate 15).

Nave arcades belonging to the 'Transitional' period exist at Horningsea and Teversham. That at Horningsea (Fig. 64), which appears to have been inserted in an earlier aisleless nave, has some capitals with small-scale scalloped decoration and others with simple coves to the capital, but both seem to be late 12th-century; it is possible that scalloped decoration once existed on all the capitals and this has been hacked back. The Teversham arcade (Plate 36) is more ornate, having stiff-leaf enrichment, and may be compared with that at Eltisley, also of the early 13th century (R.C.H.M., W. Cambs., 92).

In the 13th century a number of churches in the area were partly rebuilt or received additions. At Stow cum Quy there is evidence of transepts being added to the Norman nave early in the 13th century; a long chancel, now curtailed, was probably of the same date. Another long 13th-century chancel at Horningsea encroaches on the nave and due to the absence of a chancel arch an attenuated effect is produced (Plate 16). Windows of this date are simple lancets with no more elaboration than the suggestion of a trefoiled head, e.g. at Horningsea, but later windows in towers were sometimes large and plain, e.g. at Swaffham Bulbeck.

In the 13th century, west towers of considerable size were added to four churches, the most elaborate being at Bottisham where a modified Galilee porch was built contemporaneously with the west tower. The porch was always two-storeyed although the tall blind arch on the W. must have been in conscious imitation of the open Galilees of the greater churches (Plate 18); the upper floor communicated with the first stage of the tower proper. Although entirely rebuilt in the last century the tower of Fen Ditton church retains the original arrangement of arches on the N. and S. giving into the W. ends of the aisles; a more elaborate but contemporary version is at Bourn (R.C.H.M., W. Cambs., 18). The third 13th-century tower in the area, at Swaffham Bulbeck, is large but with no peculiarities. These towers may be dated to the mid 13th century and are certainly later than the octagonal upper stage of St. Mary's tower, Swaffham Prior, the former stone spire for which was, to judge from engravings, also of the 13th century (Plate 35).

A former single-cell chapel (Swaffham Bulbeck (3); Fig. 90) which has widely-spaced triple lancets in the E. wall may be placed early in the 13th century, possibly predating the surviving remains of Anglesey Priory, Lode (3), by a few years; these latter remains, documented to c. 1236, are discussed under Religious Houses below together with the remains of the Benedictine Priory at Swaffham Bulbeck.

The major church-building operation in the area during the early 14th century was at Bottisham. Traditionally associated with Elias de Beckingham, Justice of the Common Pleas, who died after 1306, the Bottisham nave exhibits a degree of sophistication in the handling of architectural detail and mouldings in advance of other parish churches in the county. In this respect, the square-headed eastern aisle-windows with free-standing internal mullions may be mentioned (Plate 38); also, the knapped-flint infilling to the spandrels of the recesses below the aisle windows is an early example of this technique of decoration (Plate 20). The sills of these recesses, which appear internally and externally, are in the form of coffin lids and may be connected with reburials resulting from the rebuilding of the earlier nave. The similarity between the arcade-mouldings and those at Elsworth and elsewhere in the county has already been noted (R.C.H.M., W. Cambs., xxxvi); taken in conjunction with the architectural style of the nave, the Bottisham example would appear to be early in the series, although it would be difficult to assign a date as early as that implied by Beckingham's death; the work was perhaps paid for by bequest. However, it would not be unreasonable to expect that the rebuilding of the nave on a considerable scale should originate from benefactions of a layman of Beckingham's standing.

Windows with reticulated tracery, characteristic of the 'Decorated' style of the early 14th century are not extensively represented, but arcades of this period survive at Horningsea, Stow cum Quy and Swaffham Bulbeck. The dedication of the high altar at Swaffham Bulbeck in 1346 by Bishop de Lisle must indicate the completion of the chancel although the number of dedications conducted by de Lisle doubtless gives a false impression of the extent of building activity within the space of a few years. Nave arcades of this period conform to a noticeably uniform pattern with octagonal piers and deeply-cut capitals. Late 14th- and early 15th-century building seems to have been confined to western towers, for example at Stow cum Quy and at Teversham, but an ambitious attempt to rebuild the nave at Burwell was apparently abandoned. The fitting-up of the east end of the south aisle at Horningsea with new windows and a decorative corner-niche for an image demonstrates a style in which the angular-springing of the windows combined with tracery of Geometric derivation.

The architectural and historical importance of the nave and chancel of Burwell church stems from the scale of the enterprise and authenticity of its building-date. The church of Burwell had at least from the 12th century been a large one. After the proposal to rebuild the church in the 14th century had failed, a new nave and chancel was eventually started in the mid 15th century. Constructional features would suggest that the work progressed slowly, but the nave was completed by 1464 as testified in the inscription over the chancel arch; the chancel displays the arms of John Higham, vicar 1439–67. The stylistic affinities between the window-tracery at Burwell (Plate 33) and in the side-chapels of King's College Chapel lend some support to the traditional attribution of the work to Reginald Ely. The blind panelling over the chancel arch incorporates shields within indented quatrefoils (Plate 30) which may be compared with similar decoration at Queens' College gateway for which Ely was almost certainly responsible. The effect of verticality in the interior treatment of the church is achieved by carrying the pattern of the clearstorey windows down as blind panelling into the spandrels of the arcade, and by allowing the shafts on the piers to rise from floor level, past the arcade-capitals, to the roof-corbels (Plate 31). In the chancel tall niches between the windows terminate as roof corbels, so uniting two materials in a single design. Contemporary with the nave and chancel are the octagonal upper stages of the tower, a form repeated at St. Cyriac's, Swaffham Prior, for which a substantial bequest was made in 1493. The octagonal and polygonal forms for the upper parts of towers had an ancestry dating from the 12th century with St. Mary's, Swaffham Prior, continuing almost into the 16th century with St. Cyriac's (Plates 12, 34); popularity for the form was doubtless stimulated by the tour de force at Ely in the second quarter of the 14th century, but the belfry stages of the parish church towers never achieved the lantern-effect of the wooden Octagon; closer perhaps is the octagonal belfry stage on the Cathedral's west tower which was added towards the end of the 14th century. The construction of the sixteen-sided upper stages of the tower of St. Mary's, Swaffham Prior, is but a minor development from the round tower of which there are, or were, a number of examples in the locality (e.g. in Cambridgeshire: Bartlow, Burwell (St. Andrew), Snailwell and Westley Waterless).

Annexed or ancillary buildings which may be identified as vestries or sacristies are, in the present area, normally not earlier than the 14th century, yet some later churches of considerable architectural splendour clearly were never supplied with a structurally separate compartment for these purposes (e.g. Swaffham Bulbeck). Evidence for a number of former annexes lies only in redundant architectural features, such as corbels for a lean-to roof (Fen Ditton; Plate 22) or a doorway with an external rear-arch (Teversham; Plate 17). The 13th-century tower and W. porch of Bottisham may however furnish some indication of the use for which upper compartments were put in the earlier period. Here, the first stage of the tower has windows rebated for shutters and in the E. wall a rebated recess below a window which looked into the body of the church; in the W. wall is a doorway communicating with the upper floor of the W. porch. The arrangement suggests a sacristy where the valuables were kept, there being no other provision in the church. Earlier in the 12th century, at St. Mary's, Swaffham Prior, there is evidence of a similar use for an upper stage of the tower; although less conclusive than at Bottisham, sufficient remains of the rebated recess in the E. wall of the tower to attribute an administrative use to the compartment (Plate 15). Where an aisle projected westward on the side of the W. tower, the compartment so formed could be partitioned off, as at Burwell in the 14th century; small heavy-grilled windows suggest its use as a sacristy and treasury (Plate 19). Also at Burwell is a 15th-century vaulted undercroft beneath the high altar and reached by a stair on the N. of the chancel; it is provided with a masonry altar-like podium and, in the S. wall, a stonecowled fireplace (Fig. 27; Plate 75). The compartment may be identified as a vestry or perhaps a study, even a living room, for a priest. No reference to an anchorite has been traced, but the room at Burwell may have been accommodation for an hermitic priest allowed to celebrate at the high altar; such priests are recorded elsewhere (R. M. Clay, 'Further Studies on Medieval Recluses', J.B.A.A., XVI (1953), 84 note 2). Architecturally it occupies a position which did not interfere with the symmetry of the church's exterior or with the repetition of the large chancel windows—a fact that would have appealed to that sense of precision in design associated with late Gothic architecture. At Horningsea a former outshut with lean-to roof on the S. of the tower does not appear to have had access to the church indicating some special use such as a charnel house.

The steeply-pitched chancel roof at Fen Ditton is 14th-century and probably the earliest in the area. It is of scissor-braced rafter construction and to judge from the height of the E. gable parapet it was probably designed for thatch. Evidence for other steeply-pitched nave roofs exists at Bottisham, Fen Ditton, Horningsea and Swaffham Bulbeck where redundant weathercourses survive, or survived until recently. At Bottisham and Swaffham Bulbeck small openings exist in the tower wall beneath the weathercourse; although similar in size and position, their different purposes should perhaps be noted. The blocked opening at Bottisham is a window which overlooked the interior of the church, but at Swaffham Bulbeck it is a small doorway for access to the leads of the later flat-pitched nave roof, provision for which was customary with lead-covered roofs of the time.

The area contains two 15th-century roofs of particularly high quality. The nave roof at Swaffham Bulbeck incorporating a boss bearing the arms of de Vere, Earls of Oxford, and those over chancel, nave and aisles at Burwell, dated 1464, are similarly constructed with cambered tie beams, purlins and decorative spandrel-infilling (Plates 23, 25). They constitute the height of achievement of 15th-century roof construction whereby the roof pitch is reduced to a minimum and principal rafters are dispensed with. The Burwell roof is fully integrated with the design of the rest of the building, but at Swaffham Bulbeck little respect was paid to the position of clearstorey windows resulting in a makeshift curtailment of the offending trusses. The roofs have bosses carved with figures or foliage but are otherwise not decoratively elaborate (Plate 26); at Burwell however, cornice-panels between the trusses are heavily carved in the manner seen elsewhere, for example at Denston, Suffolk, in 1474 and at St. Neots (R.C.H.M., Hunts., Pl. 122). The panels (Plates 27, 28, 29) are in relief but some of the carved figures are applied. Different hands may be detected in the carving, the master being responsible for the representations of religious themes and the less-skilled carvers for the mythical subjects. Most of the panels with religious subjects have a general connection with the Nativity but others show the Evangelists' symbols, the Host and the hand of God; all in this group are placed in the chancel or at the east end of the nave. The mythical series, often repetitive, may be divided into those that had a didactic implication and those that appear to be solely decorative. Of the first may be mentioned the representation of the tiger and the mirror referring to man's vanity, or the mermaid and the mirror to the perils of enticement, or the monkey and a urine flask to quackery (Plates 28, 29). Fabulous and semi-heraldic beasts, conventional flowers and bushes decorate other cornice-panels but their connection with moral-teaching is tenuous; likewise it cannot be assumed that the crowned heads imply royal portraiture. The carvings have been subjected to repeated repair and some figures may have been recut or renewed, but they do not appear ever to have been painted; a touch of realism was however provided by a large bead or other object which served as an eye for a figure on a boss ((2); Plate 26).

Early 19th-century church architecture is represented by the present nave of St. Cyriac's (1806). Its 'churchwarden' style of Gothic was not surprisingly condemned by purists throughout the 19th century, but the hall-like space it provides has an elegance made more romantic by its present deserted state (Plate 67).

Religious foundations

The Augustinian priory at Anglesey (Plates 68, 69) and the adjacent Benedictine priory at Swaffham Bulbeck (Plates 70, 71) have remains of a similar nature: each has a vaulted undercroft probably belonging to the prior's or prioress' lodging.

At Anglesey the two ranges, placed at right angles, can be attributed to the benefaction of Master Nicholas of St. Laurence in c. 1236. The prior's chamber, reached by an external stair incorporated in a porch, was provided with a garderobe. The range at right angles probably included the guest-hall, or combined guest-hall and prior's hall. Subsequent alterations have been considerable and the internal arrangement is enigmatic, but enough remains to show that the main walls are 13th-century. Landscaping has been extensive and no walls survive to indicate the monastic plan; footings in clunch, reported or recorded, would suggest that other buildings belonging to the priory lay S.W. of the house. The large number of fishponds, some of which have subdivisions, indicate that fish-breeding was intensive and systematic.

The remains of c. 1300 at Swaffham Bulbeck are less certainly attributable to the prioress' lodging but surviving door and window openings preclude the possibility that the range formed one side of a cloister. The vaulted undercroft has an original partition and is amply provided with lockers. No medieval feature remains on the first floor. As at Anglesey the position of the church is unknown and later disturbance to the ground makes further elucidation unlikely except in the immediate area of the building.

Building associated with the Religious

A house, built of clunch, for the bishop of Ely at Biggin (Fen Ditton (5); Fig. 55) illustrates the type of building required as a secondary residence for a 14th-century dignitary. The two-storey residential range survives: a large well-windowed ground-floor room was entered from a side wall perhaps by way of an internal porch; the upper floor appears to have been divided, the larger area possibly being the principal chamber. Only the lower room was provided with a fireplace. A wing on the S., possibly containing a chapel, had vanished by Cole's time.

Nonconformist chapels

Although Nonconformity had a large following in the county no building in the area, associated with the movement, can be dated before the early years of the 19th century, and none has architectural pretensions. A meeting house recorded in 1728 at Bottisham, where a quarter of the population were 'anabaptists or quakers', does not survive, but a community with a common persuasion, having gathered for many generations in a nearby farmhouse, built a weather-boarded chapel near by in 1819 (Bottisham (2); Bodl., Gough MS. Camb. 21, 63). A Presbyterian meeting-house is recorded in Swaffham Prior in 1731 (B.M. Add. MS. 5828, 104), but this may refer to the licensing of a private house for gatherings of dissenters; in this village a number of such licences were issued throughout the 18th and early 19th centuries, and in 1821 dissenting worship was allowed in a schoolroom (C.U.L., B4/4/1, 156, 315). Of the existing chapels only that at Lode contains woodwork of any elaboration; the chapels at Lode and Great Wilbraham (in the adjacent area) follow a common design.

Ecclesiastical Fittings

Although the area is not particularly rich in church fittings, certain groups call for comment. All fittings, both moveable and attached, are indexed under the headings appearing in the parish inventories.

Bells

The larger rings of bells are to be found at Burwell (four of 1703), Stow cum Quy (five of 1670), Swaffham Bulbeck (six of 1820) and Swaffham Prior (six of 1791). There are no bells dated earlier than the late 16th century. A bell at Fen Ditton, dated 1623, probably by William Haulsey of St. Ives, has decoration of conventional foliage (Plate 65). Examples of the archaistic use of early forms of lettering on bells were recorded at Bottisham where Lombardic capitals appear in 1606 for an inscription in English; at Stow cum Quy black-letter is used in 1670 for a Latin invocation in conjunction with Roman lettering for the founder's name. Two frames, at Fen Ditton and Teversham, may be medieval.

Benefactors' Tables

Although a large number of painted boards recording benefactions survive, only that at Bottisham (No. 3; Plate 45) is exceptional on account of its shape and early date. At Stow cum Quy an elaborate marble classical composition recording benefactions in 1675 is notable for its material and its resemblance to a wall-monument (Plate 49).

Brasses and Brass Indents

The earliest brass is indicated by a large slab with indent for the figure of Elias de Beckingham (died after 1306) at Bottisham (Plate 41). The fact that the inscription does not contain the date of death and that the carefully-spaced marginal letters made no provision for its inclusion after death might suggest that the monument had been prepared in advance. The indent has three additional horizontal sinkings to take strengthening pieces at the junctions of plates; in other indents, for tabernacle-work and Lombardic letters, bitumen is preserved.

A 15th-century brass at Stow cum Quy to John Ansty and wife has two groups of children with the sons uniformly wearing tabards blazoned with the arms of Ansty (Plate 42). The palimpsest brass at Burwell (Plate 43), of the early 16th century, re-using a number of earlier pieces, is the most elaborate brass in the district; its attribution is discussed in the Inventory.

Coffin Lids

A large number of early coffin lids have survived. The earliest (Fig. 65) is a fragment at Horningsea having close affinities to the complete stones from Cambridge Castle which have been ascribed to the late 10th or early 11th century (R.C.H.M., Cambridge, Pl. 28 (ii)). Double-omega ornament appears on eight stones (Bottisham (two), Burwell, Horningsea (two), Lode (Anglesey Abbey, two) and Swaffham Bulbeck); these have been described as early 13th-century in conformity with the dating of slabs with this decoration in west Cambridgeshire (R.C.H.M., W. Cambs., xli). None of these slabs is in situ and two, at Bottisham and Swaffham Bulbeck, are now used as stiles. Zoomorphic decoration on a stone at Horningsea (No. 6; Plate 40) emphasises the difficulty in attributing dates to objects of this nature. A complete lid (Plate 40) at Fen Ditton may be noted for its length of only 2½ ft. The slabs incorporated in the internal and external blind arcading at Bottisham (Plate 20) are coffin lids or quasi-coffin lids although the roll-moulded edges return at the ends as part of the architectural treatment; they are certainly early 14th-century.

Fonts

Examples of fonts from the 12th to the 15th century have been recorded but only that from Fen Ditton calls for special comment. This font (Plate 39) may be closely dated on heraldic evidence to the episcopacy of Thomas Arundel, 1374–88. Although mutilated and heraldically inaccurate, the significant shields are for the See of Ely and for Arundel; a further shield may be for Bohun but an association between that family and Fen Ditton has not been verified. A comparable cycle of heraldry allows the screen at Barton Church (R.C.H.M., W. Cambs., 14) to be similarly dated to Arundel's episcopacy at Ely.

Glass

Little ancient glass survives in the district, but some at Horningsea is in situ and is contemporary with the 14th-century S. aisle window.

Monuments

Clunch was the prevailing material for large monuments during the 16th and 17th centuries throughout the county. Two in this group at Burwell have both been moved with consequent damage (Plate 48); that with the recumbent effigy to Lee Cotton (d. 1613) (No. 12) beneath a classical columned-canopy is possibly less pedestrian than the Gerard family wall-monument (No. 8). The iron railings protecting another in clunch, at Bottisham (No. 5; Plate 47) are preserved. The tomb chest at Teversham has also been moved with the loss of its railings (C.A.S., Relhan watercolours) but the alabaster effigies of high quality remain (Plate 46). A black and white marble wall-monument at Fen Ditton to the Willys family (No. 1; Plate 49) is composed of plain panels and pilasters allowing scope for a display of heraldry and calligraphy. Of the later monuments in marble, that with the reclining figures of Sir Roger Jenyns, 1740, and his wife, at Bottisham (No. 6; Plate 50) invited considerable abuse during the 19th century. Of the 18th-century monuments signed by London sculptors that by J. Bacon at Fen Ditton calls for attention (No. 2; Plate 51).

Monuments in Churchyards

Churchyards within the area still contain upwards of 200 tombstones dating from before 1850. Most of those earlier than 1820 are carved in addition to being inscribed. The two earliest stones, both at Burwell, are undecorated but have inscriptions in vernacular spelling. One is dated 1678 (Plate 53 (c)); the other [1668?], probably by the same hand, has a large rectangular hole below the inscription suggesting that it was perhaps one end of a tomb chest of early form (Plate 52 (a)). However, other stones of the late 17th and early 18th centuries are carved in high relief with representations of emblems of mortality, architectural ornament, drapery and winged cherubs' heads (Plate 52 (f)). The decoration usually continues down the sides to form a cartouche. Two early 18th-century headstones with symbolic decoration are outside the general category: one at Burwell, carved with a large flaming heart, commemorates the deaths of 73 people in a fire in 1727, the other at Swaffham Prior is ornamented with a design copied from Quarles' Emblems Divine and Moral, (Emblem 12 from Book II), and is inscribed with a verse only (Plate 53(a) and (b)). Emblems of mortality continued to be used in designs of the second half of the century but the carving is by then much less vigorous. A distinctive early 18th-century group, represented at Burwell and Swaffham Prior, has heavy scrolling with a central roll flanked by inverted scrolls (Plate 55 (a)); other examples occur at Moulton and Newmarket implying a workshop in the eastern part of the county rather than in Cambridge. During the second half of the 18th century, cherubs' heads and floral scrolls were the most favoured decorative motifs although between 1740 and 1780 rococo designs, often of high quality, were also common (Plate 55 (f)). The central urn remained a popular decorative feature for some sixty years from c. 1780 (Plate 55(g)). Headstones dating between 1807 and 1823 at Burwell and Swaffham Prior can be identified as products from the same workshop. There are two basic designs, both having thin floral scrolls flanking a winged cherub's head which is usually drawn with some individuality; their distribution appears to be limited to the Newmarket area (Plate 55(h)).

Many of the earlier stones still have footstones, the most notable group being at Fen Ditton. Apart from the 17th-century stone already mentioned, the earliest coffin-shaped chest is dated 1727; throughout the 18th century such chests were general but many have been removed over the years. Tomb chests, as distinct from coffin chests, first appear in 1737 at Burwell, and later at Bottisham and Swaffham Bulbeck; they are decorated with pilasters and panelling in the fashion of their time.

The earlier stones are lettered in Roman capitals but italic alphabets are frequent by the early part of the 18th century. Copybook Germanic script appears in 1735 but headstones relying entirely on calligraphy for their character are not common until the 19th century.

Jurassic limestones are the normal materials for all headstones before 1800 but the brown sandstone, often associated with calligraphic display in the 19th century, occurs exceptionally at Fen Ditton in 1757. A particularly fine-grained grey stone is used for capping tomb chests in the 18th century. Grey slate is not found before 1851.

Cast-iron monuments in the form of headstones are recorded elsewhere in the county, particularly at Soham, but the tomb chest of 1844 in this material at Horningsea, originally painted in imitation of stone, is exceptional.

Piscinae and Sedilia

Single piscina-recesses unconnected with adjacent architectural features are usually of simple character with pointed or square heads. However, the position of a simple rectangular recess at Horningsea has bearing on the interpretation of peculiarities in the church's architecture. This recess at the W. end of the chancel is 12½ ft. above floor level; below it and slightly westward is another recess of the same date. A wide screen with altars on two levels is indicated and this example of a rood-loft altar requires the amendment of the view that the practice is unknown in eastern counties (Howard and Crossley, English Church Woodwork, 219). Also 13th-century are two double piscinae with central columns in the chancels of Bottisham and Horningsea, but both have suffered by alteration or restoration. At Burwell, the late 15th-century piscina in the N. aisle is in two stages, and that in the chancel is below a recess and in the splay of a side-window; these upper features may be identified as credences.

Sedilia combined with the piscina in the same design occur at Bottisham and Teversham. A unified composition at Bottisham of the early 14th century incorporates sedile, piscina and window above (Plate 38). The graduated sedilia at Teversham has minor variations, according to status, in the widths of the seats; the canopies however differ perceptibly, the eastern receiving greater enrichment (Plate 38). The 14th-century sedilia at Swaffham Bulbeck are not linked with the piscina but instead form part of an architectural composition with the canopied tomb-recess on its W. side (Plate 38). As at Teversham, the backs of the seats and canopies rise above the sill of the side-window of the chancel. This interruption to the window was presumably unacceptable at Burwell where a low window-sill served as sedilia. The tendency to dispense with canopies for sedilia would seem to be customary in the late Perpendicular period (e.g. King's College Chapel, Cambridge).

Plate

Elizabethan plate includes that made for Horningsea in 1569 by Thomas Buttell; it is not assayed but bears Buttell's mark of a flat fish and follows the uniform pattern of cups by this maker already noted in west Cambridgeshire (R.C.H.M., W. Cambs., xliv). Other pre-Restoration pieces are also at Horningsea; the large but simply-designed silver-gilt cup of 1635, with contemporary paten, was given to the parish by St. John's College in 1829. An elaborately-engraved beaker, by Hinrech Ohmsen (active 1654–80) at Swaffham Bulbeck is a distinguished piece of German origin.

Screens

The number of stone screens which survive or for which there is evidence confirms the observations already made on these objects in the west of the county (R.C.H.M., W. Cambs., xlv). At Bottisham in the early 14th century, stone screens filled the first bays of both N. and S. arcades; little remains of these except for a springer on the N.E. respond showing that the tops were weathered (Plate 36). Evidence for a stone screen of the same date is at Teversham where a mutilated stone with weathered top projects from the S. respond of the chancel arch; when the arch was heightened later in the 14th century, the upper part of the screen was destroyed, the lower part of the respond being retained together with the single stone which belonged to the balustrade or dado of the screen. At Fen Ditton a stone screen originally stood at the E. end of the S. aisle; part of it was reset under the W. tower arch in the last century, later to be dismantled and destroyed (Parker, Ecc. Top. Cambs. No. 69). The most complete example is at Bottisham (Plate 21). Dating from the 15th century it is more slender and less of a physical barrier than that at Harlton in west Cambridgeshire; the present balustrade is almost certainly mid 19th-century. Although the existing cornice is a wooden replacement, it appears that the screen was always without a rood loft. It combines limestone in the lower part with clunch in the upper.

Ancient wooden screens, or parts of them, remain in the churches at Bottisham, Burwell, Stow cum Quy and Teversham, and fragments of another from Fen Ditton are not now in the church. They are probably late 14th- or early 15th-century but none has precise dating criteria. Those at Bottisham (Plate 56) have been rearranged as parcloses at the ends of the aisles but mortices and other constructional features suggest a former loft. Chancel-screens at Stow cum Quy and Teversham churches (Plate 57) have lost their rood lofts; each has a wider central bay for an entrance which seems to have been always without doors. These screens conform to the East Anglian type with slender mullions, a complexity of windowforms and, originally, with comparatively small coves below the rood loft. Nothing remains of the substantial screen that must have existed at Horningsea although the lower part remained until 1844 (Paley, Churches near Cambridge, 3); piscinae of the 13th century on two levels imply a lower altar against the screen and a second altar in the loft.

The purpose of a rectangular opening at Fen Ditton, now blocked, at clearstorey level, was probably to light the rood loft.

Seating

13th-century stone wall-benches with arm rests at St. Mary's, Swaffham Prior, are the earliest surviving examples of church seating in the area (Plate 14). Wooden pews of the 15th century at Swaffham Bulbeck have an extensive series of bench-ends with animals, real and fabulous, as finials and arm rests (Plates 58, 59). The benches are plain with simple planks for seats and back-rests. The bestiary consists of a lively selection of creatures including wyverns, fishes, Bactrian camels and a mermaid, but no particular inference can be deduced from the subject-matter although a number of the representations have a known association with morality-teaching. These pews, in their original positions, may be compared with those at Denston, Suffolk, which are contemporary with that church's construction in c. 1474. Later pews, albeit probably pre-Reformation, at Horningsea and Teversham, are without shaped ends and rely on panelling and rollmouldings for decoration.

Post-Reformation Woodwork

A number of churches contain woodwork of the 16th and 17th centuries similar in character to that preserved locally in secular buildings. The pulpit with linenfold panelling at Horningsea (Plate 61) is the most complete; another at Teversham (Plate 61) has lost the tester which survived until the pulpit's removal from Cherry Hinton church during the last century.

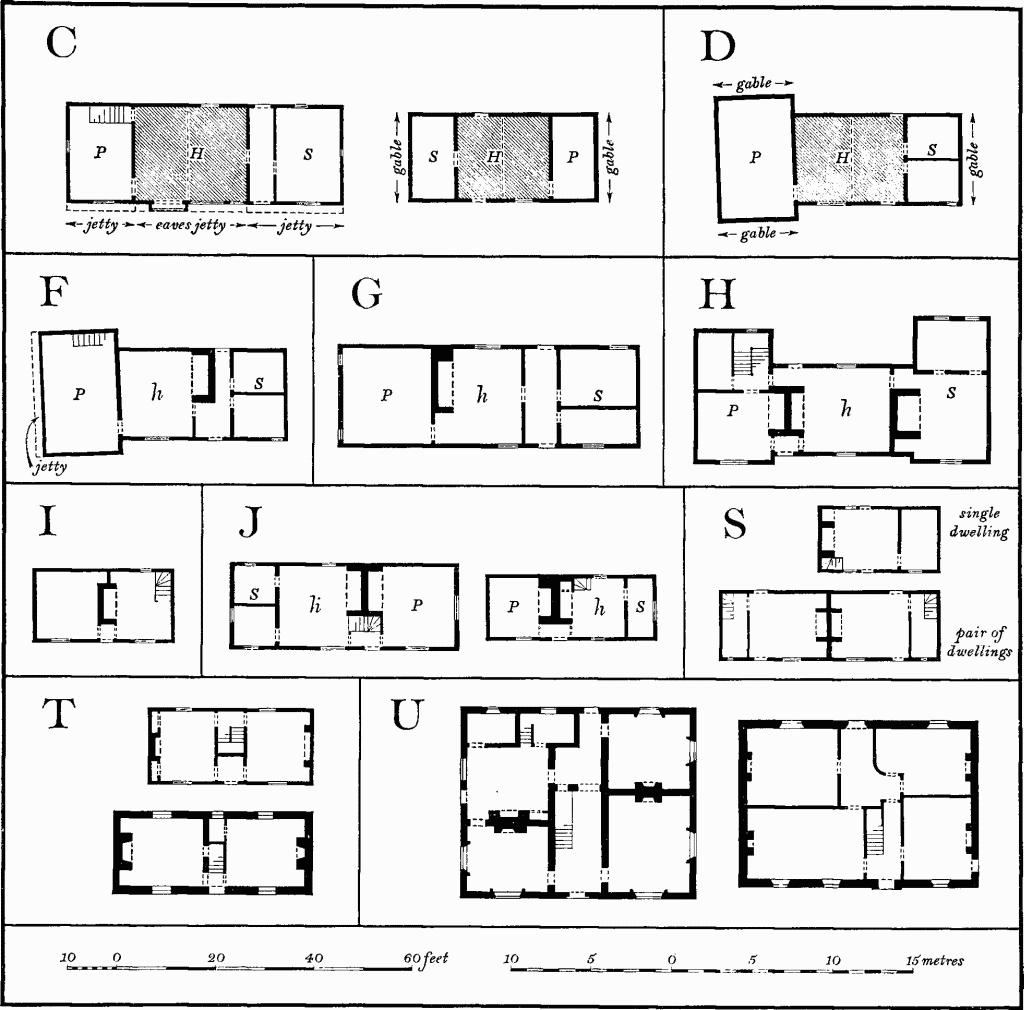

Secular Buildings

In describing the smaller houses in this Inventory it was found convenient to shorten the verbal descriptions of individual buildings by the use of a plan typology similar to that first employed in West Cambridgeshire. The same reference letters have been retained but it has been necessary to redefine some types—notably J and S—and to add two new types: F and G. The accompanying diagram (Fig. 3) shows the revised classification. As in West Cambridgeshire the allocation of a house to a particular class refers to its plan when first built and not necessarily to that which now exists. In a few examples the typology is also used to describe the revised plan of a house after early alterations.

The classes of houses occurring in north-east Cambridgeshire may be briefly described as follows:—

Houses having a hall which is open to the roof:

Class C: having a simple rectangular plan with three ground-floor compartments in line.

Class D: having the service rooms in line with the hall, and the parlour in a cross wing.

Houses in which the hall, or principal room, is ceiled:

Class F: having three ground-floor compartments, with a screens passage against which there is a chimney stack in the central room.

Class G: having three ground-floor compartments, with a screens passage and an internal chimney at opposite ends of the central room.

Class H: having a central range and two cross wings.

Class I: having two ground-floor rooms with a central chimney against which there is a lobby entrance.

Class J: having three ground-floor compartments with an internal chimney against which there is a lobby entrance.

Fig. 3 Classification of Houses The diagrams illustrating types of houses are based upon existing houses in the area covered by this Inventory, but they are schematic in so far as later additions have been omitted. In walls shown without openings, the original features are not traceable. Compartments have been given the following references: P for Parlour; H for Hall; h for hall with a storey above; S for Service end.

The following houses have been used as a basis for the diagrams; those marked with an asterisk are shown in greater detail in the Inventory:

Class C: Swaffham Bulbeck (4)*, Swaffham Prior (12)*; Class D: Swaffham Bulbeck (8)*; Class F: Swaffham Bulbeck (8)*, after alteration; Class G: Swaffham Prior (4)*; Class H: Fen Ditton (6)*; Class I: Reach (22); Class J: Burwell (99)*, Lode (15); Class S: Lode (22), Swaffham Bulbeck (52)*; Class T: Bottisham (43)*, Burwell (8); Class U: Bottisham (9), Burwell (22).

Class S: having a single living room with one end partitioned off to provide storage and sometimes a stair to the upper floor.

Houses with a symmetrical arrangement around a central passage:

Class T: having two living rooms, each with end chimney stacks.

Class U: having an approximately square plan, with rooms arranged in double depth.