An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in the City of Cambridge. Originally published by Her Majesty's Stationery Office, London, 1959.

This free content was digitised by double rekeying. All rights reserved.

'Sectional Preface: Early Cambridge', in An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in the City of Cambridge(London, 1959), British History Online https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/rchme/cambs/lix-lxxii [accessed 30 January 2025].

'Sectional Preface: Early Cambridge', in An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in the City of Cambridge(London, 1959), British History Online, accessed January 30, 2025, https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/rchme/cambs/lix-lxxii.

"Sectional Preface: Early Cambridge". An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in the City of Cambridge. (London, 1959), British History Online. Web. 30 January 2025. https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/rchme/cambs/lix-lxxii.

In this section

CAMBRIDGE CITY: Sectional Preface

Earthworks and Cultivations

Very few earthworks still visible to the ground observer survive in Cambridge city and none that is certainly representative of the pre-Roman period, but this is scarcely surprising in view of the spread of the built-up areas. The distribution of finds shows that more than the two definite barrows (Monument (I)) and two putative barrows (Monuments (2, 6)) must have existed to represent the Bronze Age; certainly more than the 'War Ditch' (Monument (3)) represented the Iron Age, for this, though once protected by a bank and ditch, has an interior area only a little larger than that of Little Woodbury, an Iron Age farmstead excavated in Wiltshire. (fn. 1) Indeed, apart from the mound (Monument (6)), nothing would have been known even of these sites but for the chance exposures of quarrying and the use of aerial photography.

Apart from the banks of Roman roads (Monument (10)) and perhaps the heavily ploughed scarped boundaries of some fragmentary 'Celtic' fields (Monument (4)), possibly Iron Age in origin, there are no notable remains of the Roman period, though on the W. and N.W. boundaries of the Roman town are grassy scarps that may mark the site of the Roman walls (see p. lxi).

The Castle mound (Monument (77)), the sole survivor of the truly mediaeval earthworks of Cambridge, has suffered heavily over the years. Even the berm running just below the flat summit, which is marked pronouncedly on plans and sections of 1785 (fn. 2) and which perhaps supported an apron-wall, has now been mutilated almost out of recognition. Raised within a decade of the Norman Conquest, Cambridge Castle, which dominated the town physically and administratively, was re-edified with stone walls and buildings in the 13th century. The absence of all stonework today is amply explained by the recorded use of it as a quarry from Henry VI's reign onwards for, inter alia, King's, Trinity, Emmanuel and Magdalene Colleges, and Sawston Hall. The perimeter of the Castle bailey, after many changes, was adapted during the Civil War to meet the military needs of the time, and of the bastions then built one, next N. of the Castle mound, is relatively well preserved.

Broad plough ridges as shown on the plan (p. 3) were still traceable in 1953. They represent remains of cultivation in the pre-enclosure open fields,

The Roman Town

Site and Early Occupation

In the N.W. area of Cambridge a small outlier of Chalk Marl from the main mass S.E. of the river, capped by remains of Pleistocene gravel, forms a broad ridge over 60 ft. above sea level near Castle Hill, rising to more than 75 ft. in the earlier Observatory Gravels towards Girton. Occupying the S.E. end of this ridge was the Roman town at Cambridge.

Such evidence as could be gleaned from the rectangular ditch (Monument (14)) disclosed during the construction of the Shire Hall in 1929–30 has suggested the existence of a military camp or fort of the invasion period: (fn. 3) another view is that it indicates no more than a possible Belgic origin for the settlement. (fn. 4) Other evidence (see p. xxxvi) points to an initial date of c. A.D. 70 for the civil occupation of the hill.

Plan

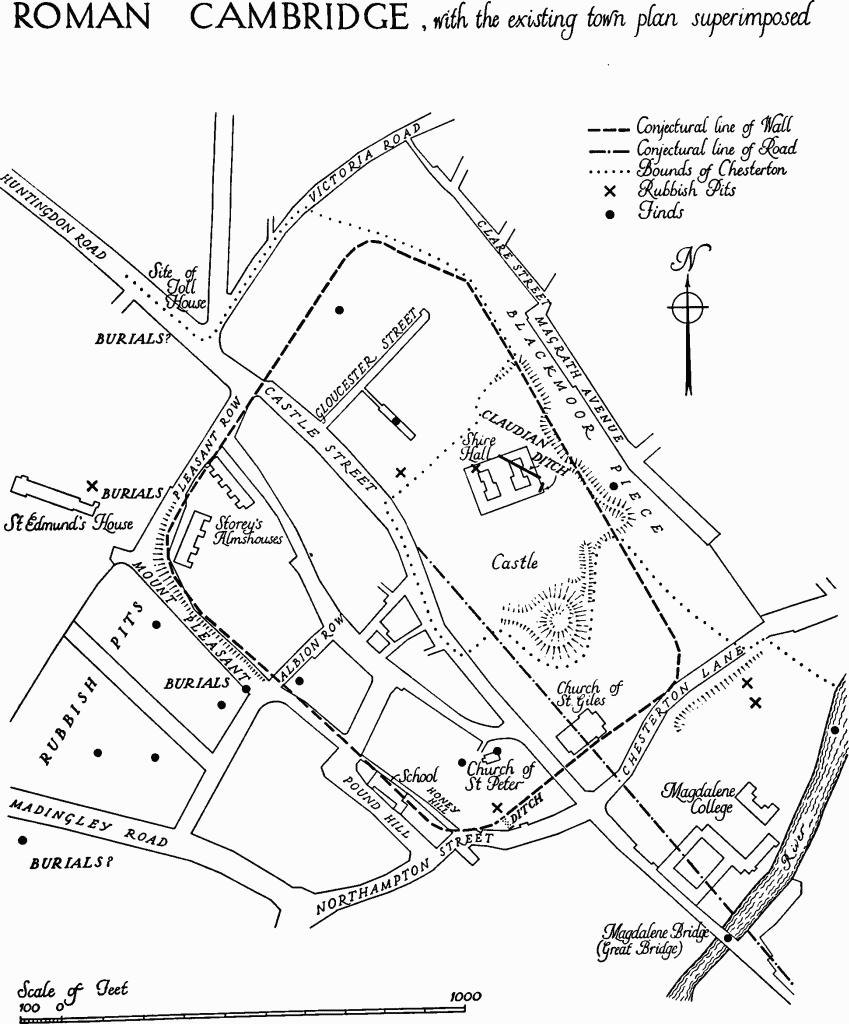

The Roman defences (plan, opposite) appear to have enclosed a sub-rectangular area of between 25 and 28 acres. The longer axis of the town, lying N.W.–S.E., will have been roughly bisected by the 'Via Devana', which, according to the available evidence, crossed the river by a ford or wooden bridge a little below the present Magdalene Bridge and entered the town at about the centre of the southern side. It will have issued again on its route to Godmanchester by a N. gate, the approximate position of which is defined by the Huntingdon Road on the Roman line, and presumably across a bridge over the ditch; McKenny Hughes records the last as uninterrupted at this point. (fn. 5) The upper part of Castle Street may preserve the alignment for a short distance within the town. Smaller Roman towns were not all planned with a regular street system; at Cambridge development may have spread in somewhat haphazard fashion from the intersection of the main roads, but ignorance of the position of E. or W. gates (fn. 6) leaves the situation of Akeman Street quite uncertain, though the last known alignments of its branches permit an inference that it was probably appreciably N. of the centre of the town's axis.

Defences

The only evidence for the date of the defences comes from the excavation near Northampton Street (see Monument (15)) where the ditch was shown, at least in its surviving form, to be certainly not earlier than c. A.D. 200 and more probably later than c. 300. The defences consisted of an earthen bank and ditch which seem to have been supplemented, probably at a later date, by a stone wall of tile-laced mortared rubble. John Bowtell recorded a number of features exposed during the extensive excavations for building and making bricks for the new gaol (on the site of the present Shire Hall) begun in 1802. The eastern ditch, from 10 to 12 ft. deep and 39 ft. broad, was found in Blackmoor Piece, (fn. 7) a strip of land dug for brickmaking, immediately below the Castle scarp, and now built over by Magrath Avenue and Clare Street and the houses to the W. (fn. 8) These dimensions compare closely with those of the southern ditch (Monument (15)) excavated near Northampton Street in 1949, where a width of about 35 ft. was inferred and the depth shown to be 8 ft. below the top of the gault subsoil. The accompanying bank has nowhere survived in certainly recognisable form.

The evidence for the stone wall is provided by the mass of Roman rubble found in 1949 in the lower filling of the southern ditch and by Bowtell (1753–1813), who states that on the interior edge of the fosse 'stood a very ancient wall, some remains thereof were discovered in Mar. 1804 when "improvements" were making thereabouts by destroying a part of the vallum towards the N.W. end; which wall abutted eastwardly on the great road, near to the turnpike-gate leading to Huntingdon, and westwardly at a little distance from "Drake's spring". (fn. 9) The materials in the foundation of this wall consisted of flinty pebbles, fragments of Roman bricks and ragstone, so firmly cemented, that prodigious labour, with the help of pickaxes &c. was required to separate them:—a part of the wall was consequently left undisturbed, and the fosse-way which accompanied it, was filled up with earth from the mutilated ramparts of the Castle-yard, raised in the time of Cromwell's usurpation'. (fn. 10)

Roman Cambridge, with the existing town plan superimposed

Elsewhere he records that during the excavations in Castle Yard in 1802 fragments of Roman brick were found 'scattered along the edge of the fosse where the wall had anciently stood'. (fn. 11)

The perimeter of the embanked or walled area of the Roman town (plan, p. lxi) can be made out with tolerable accuracy from the present topography, supplemented by the evidence of early maps. The circuit described by Stukeley (fn. 12) in 1746 goes astray at the S.W. corner, and adds nothing to what may still be observed.

The western side is defined by the street and lane alignment between Storey's Almshouses and Northampton Street. As far S. as Albion Row there is still a considerable earth scarp, which may be taken to represent the edge of the ditch and perhaps extended in Bowtell's time as far as the Free School between Pound Hill and Honey Hill. (fn. 13) The southern side, as was demonstrated by the section cut across the ditch in 1949, ran well within the loop formed by Northampton Street and Chesterton Lane. The terraced scarp in the grounds of Magdalene College, accepted, since Stukeley wrote, as the remains of the Roman rampart, (fn. 14) and excavated by Walker in 1910, (fn. 15) may be regarded merely as a continuation of the river terrace that exists E. of Strange's Boat House, and its stratification should be interpreted as the successive tips of Roman and later rubbish from the occupied area on Castle Hill.

The eastern and northern limits of the town are less easy to determine with precision, but it is likely that the bounds between St. Giles' and Chesterton parishes and the scarp of the Castle bailey indicate in a general way its eastern limit within the ditch recorded by Bowtell in Blackmoor Piece. The parish boundary in Victoria Road is suggestive of a northern limit, but such a line is not easy to reconcile with the remains seen by Bowtell W. of the Huntingdon Road, which were evidently in the S. side of Pleasant Row. (fn. 16) It seems likely that the latter preserves the general alignment of the whole northern rampart.

Structural Remains

No remains of buildings or streets have been recorded within the walls, although loose tesserae have been found. (fn. 17) Reused Roman brick in the fabric of St. Peter's church could have come from the Roman town wall. As substantial stone foundations could hardly have escaped notice, probably most buildings were entirely of timber and other perishable materials. The town doubtless grew as a local market centre, and may be compared with the walled town of some 35 acres at Great Chesterford, Essex, where stone foundations appear to have been reserved for a few public buildings of simple type, and with other walled towns beneath modern settlements, like Great Casterton, Rutland, of some 13 to 18 acres, where stone foundations are uncommon.

Roman rubbish pits within the town have been observed at the site of the new Shire Hall, Castle Hill, and a pit or ditch with 2nd and 3rd-century pottery at the garage of the Police Station, Castle Street; pottery and other objects, some of which are preserved in the Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, are recorded from the Castle Hill area, Gloucester Street, Albion Row, and St. Peter's church. Rubbish pits with large quantities of Roman pottery found outside the N.W. corner of the town, at St. Edmund's House and between Mount Pleasant and Madingley Road, (fn. 18) and outside the S.E. corner, in the grounds of Magdalene College, (fn. 19) where an area was also found paved with slabs of oolitic limestone, are probably to be interpreted as the result of occupation or industrial activity developing alongside the main roads outside the defences, since late pottery and 4th-century coins, including at least one of the late 4th century at the second site, are numbered amongst the finds. It is possible, however, that some of the remains could relate to a spread of occupation at a date before the erection of the defences.

Late Occupation

The persistence of occupation in and about the Roman town in the late 4th century A.D., and perhaps well into the 5th, is evident not only from the latest coins, of Arcadius and Honorius, recorded by Bowtell at the site of the Gaol, and those including issues of Theodosius I and Arcadius recorded by Walker in the grounds of Magdalene College, (fn. 20) but also from the presence of pottery vessels of hybrid Romano-Saxon type in the Anglo-Saxon cemeteries, as at St. John's College cricket ground and Girton, where continuity of tradition may also be implied by the presence nearby of Romano-British burials. The occurrence of Roman objects, probably as loot, in these cemeteries has been noted, (fn. 21) but the class of hybrid pottery 'reflects in varying degrees the survival of the native population in different communities, no doubt mainly in the form of captive women in whose hands the older craftsmanship here and there maintained a faint and flickering continuance'. (fn. 22) The fragment of a hybrid vessel from Latham Road, Trumpington ('Dam Hill'), where again Romano-British burials were succeeded by Anglo-Saxon, is however of a type that betrays Teutonic influence during the late Roman period. (fn. 23)

Cemeteries

No burials of Roman age have been recorded in the walled area. Two suspected cemeteries, along the 'Via Devana' and Akeman Street, have some certainly of this period on the further fringes, but the evidence for their extent and for the existence also of a third, alongside Akeman Street immediately N.E. of Castle Hill (see Monument (10b)), is largely circumstantial, depending upon the value placed upon the discovery close to the town of whole, or nearly whole, pottery vessels and other objects, and of undated, or unreliably dated, burials that are unlikely to be later than the Roman period. No estimate can be made of the degree to which these areas were developed as cemeteries, but the impression is one of thinly and perhaps intermittently scattered burials along the line of the roads and their vicinity. Very few records appear to refer to cremation burials.

The graves seem to have been poorly furnished in comparison with the richer graves known in the region, even with those in the near neighbourhood of Cambridge, like Girton, Arbury Road, Coldham Common, and 'Dam Hill' (Trumpington), where vessels of glass, bronze and pewter are recorded. Only two (fn. 24) placed together alongside the Huntingdon Road, not far short of Howe House, were provided with stone coffins of Barnack rag. (fn. 25) One of the coffins (Plate 1), now preserved at the Fitzwilliam Museum, contained a female skeleton; it compares with the coffins (Plate 1) found at Arbury Road (Monument (13)), but has an inset semicircular end. (fn. 26) Grave goods, where present at all, seem to have consisted usually of a few pottery vessels and small objects. The richest known group, outside but presumably accompanying this Fitzwilliam Museum coffin, comprised four cylindrical flasks of Rhenish glass, some kind of bronze vessel, a Castor ware bulbous beaker, a coarse-ware plate, a jet armlet, and pins of jet and bone; it may be dated to the 3rd or early 4th century.

Use during the 3rd and 4th centuries of the cemeteries alongside Huntingdon Road and S.W. sector of Akeman Street, if not also of that N.E. of Castle Hill, is attested by grave goods and the prevalence of inhumation burials, which are generally late in the region. The records are too scanty or ambiguous to afford useful evidence for the earlier occupation of the town or the development of the road system.

Industries and Trade

Several pottery kilns are known in the area. A group discovered at Horningsea (fn. 27) and remains of a kiln recently found at Milton (fn. 28) are outside the present city boundaries, but without doubt both existed to supply the people resident in Cambridge and neighbourhood. The kiln at the 'War Ditch' (Monument (3)) appears to have produced pottery in the late 1st century, though a slightly later date is possible. Several complete waster vessels found between Jesus Lane and Park Street attest a kiln or kilns near the Roman town itself; they are described by Fox, (fn. 29) but their date must now be advanced to the 4th century A.D. (fn. 30)

Barnack ragstone was imported from the neighbourhood of Durobrivae (Water Newton, Northants.), as evidenced by sarcophagi found at the Huntingdon Road cemetery and at Arbury Road (Monument (13)). Ketton freestone from the same region was used for the sculpture found at Girton, presumably from a house or monumental tomb, (fn. 31) besides being employed in the construction of Roman buildings elsewhere in the county. (fn. 32) Clunch, used locally, at least, for the foundations of buildings, as at Arbury Road, was obtained from the Melbourn Rock outcrop at the base of the Middle Chalk, probably from near the Romano-British settlement on the site of the 'War Ditch', Cherry Hinton (Monument (3)), although White Hill, Great Shelford, would have been almost equally near and accessible from the Roman road.

The existence of a Fenland river and canal system in Roman times (fn. 33) suggests a direct route for the transport of such heavy materials from Northamptonshire to Cambridge, though the Barnack rag coffins, at least, probably date from after the decay of this system at the Cambridgeshire Car Dyke end early in the 3rd century. The quantity of ware imported into the Cambridge region from the Castor kilns from the late 2nd century onwards also attests continued trade between the two regions.

Settlements near Cambridge

Within the area covered by the Inventory, buildings of stone are known to have existed at Manor Farm and Arbury Road, Chesterton (Monuments (11 and 12)); and a succession of rectangular timber huts or barns has been found overlying the ' War Ditch', Cherry Hinton (Monument (3)). (fn. 34) Excavations at the second and third sites suggest more or less Romanised farms; the occupation at Manor Farm, near which, as in the vicinity of the 'War Ditch', are traces of a field system probably of Roman date, may be of like character. Less is known of the other sites where permanent occupation of major character may be inferred from the presence of rubbish pits and ditches or cemeteries, but all of them may have been of similar nature. These existed on gravel subsoil near the river at Biggin Abbey, Milton Road Sewage Farm, Trinity Hall, 'Dam Hill' (Trumpington), and Newnham College; on gravel and chalk marl at Gravel Hill (University Observatory), and on chalk marl at Coldham Common (Barnwell). They have no place in the Inventory, though the earthworks (Monument (9)) at River Farm may possibly be associated with the site recorded at 'Dam Hill'. Evidence of occupation in the 1st century A.D., in some cases certainly begun before the Conquest, appears at nearly all the sites where Roman occupation is attested, save in the region N. of the Roman town, where its initial date seems to be c. A.D. 130–140.

The Roman Name for Cambridge

Professor Skeat exposed the unsoundness of the major premise upon which the attribution of the name Camboricum, or Camboritum, to Cambridge was based when he showed that the element Cam- was a mediaeval corruption of Granta-. (fn. 35) Two recent authorities have suggested that Cambridge is probably to be identified with the Durolipons of the Antonine Itinerary. (fn. 36) A. L. F. Rivet of the Ordnance Survey has kindly contributed the following note on the Roman name for Cambridge:

'The Roman name for Cambridge is uncertain. The milestones found along the Huntingdon Road omit both the mileage and the name of the place from which it was measured, and no inscriptions have been recorded from the town itself. There are, however, two literary sources that may be relevant. In the Ravenna Cosmography two names, Durcinate (=Curcinate?) and Durovigutum, appear between Colchester and Castor (Northants.); either might conceivably apply to Cambridge, but the latest editors of the work do not support the idea and suggest Braughing and Godmanchester respectively. (fn. 37) The second source is the Antonine Itinerary.

A portion of the fifth of the British itinera (474.4–475.1) reads as follows:

Colonia is certainly Colchester and Durobrivae Castor, but none of the intervening places can be identified with certainty. (fn. 38) In the British section of the Itinerary as a whole errors of more than three Roman miles are very rare and are probably due to textual corruption; in the case of errors of less than three miles the Itinerary figure is invariably short. Unfortunately this particular iter shows signs, especially variations in the form of names, of being derived from a different source from the rest, and it is thus uncertain whether the general standards apply. Nevertheless the fact that the actual distance along the Roman road from Cambridge to Castor (fn. 39) is 36 Roman miles compared with the 35 of the Itinerary for Durolipons to Durobrivae strongly suggests that Durolipons is the name of Cambridge. Two further qualifications must, however, be made. If, as seems likely, Icinos is to be identified with Venta Icinorum in the ninth iter (479.10), this presupposes a more or less direct road from Cambridge to Caister St. Edmunds, with Camboricum falling near Icklingham; this is not in itself improbable, but the road has not been traced. Secondly, in the light of the recent increase in our knowledge of the Roman occupation of the Fens, the possibility must be borne in mind of a reference to the more northerly route from Castor to Caister; and the fenland section of this road is well established.

It will be seen that the text of the Antonine Itinerary lends no support to the once popular attribution of Durolipons to Godmanchester and Camboricum or Camboritum to Cambridge. This arose from the apparent similarity of the names Camboricum and Cambridge and seemed to be confirmed by Bertram's spurious Itinerary of Richard of Cirencester, where the figures are adjusted to agree. In fact Cambridge is Grantacaestir in Bede and Grentebrige in Domesday; the change of Gr- into C- first appears in the Inquisitio Eliensis (1086), where the name is Cantebrigie. (fn. 40) The old name of the river is Granta; Cam is a backformation from Cambridge'. (fn. 41)

Ecclesiastical, Collegiate and Secular Buildings

Parish Churches

The description of Cambridge in the Hundred Rolls of 1279 (fn. 42) includes three parishes N. of the river, fourteen S. of the river, the suburb of Barnwell, some houses at Newnham, seventeen churches (excluding those of the nine religious foundations), etc., though no colleges. Today in the area of the old town of Cambridge and Barnwell eleven mediaeval churches survive and three 19th-century churches are rebuildings of mediaeval ones. The eleven include Holy Sepulchre, Holy Trinity, St. Andrew the Less, St. Benet (Benedict), St. Botolph, St. Clement, St. Edward the King and Martyr, St. Mary the Great, St. Mary the Less, St. Michael, St. Peter; the three, All Saints, St. Andrew the Great, St. Giles. Two churches, Christ Church and St. Paul's, are new foundations of the first half of the 19th century, and the church of St. Matthew, though post-1850, includes some earlier fittings, brought from elsewhere. The new boundaries of the city also include the outlying mediaeval parish churches of Cherry Hinton, Chesterton, and Trumpington. Only the church of St. Benet retains major structural survivals from before the Conquest: the tower and parts of the chancel and nave walls were built in all probability early in the second quarter of the 11th century; the two latter are fragmentary but the tower, except at the wall-head, and the notable monumental tower-arch with original carved label-stops stand complete. To the beginning of the same century, c. 1000, belong the important cross and series of carved gravestones (see Monument (77)) found under the rampart of the Castle bailey; the existence of the minster church of post-Danish Cambridge near this site suggested by their presence is confirmed by the foundation near the Castle in 1092 of a house of Canons Regular, later removed to Barnwell (see Monument (64)), (fn. 43) for these houses often succeeded and took over the property and duties of the Saxon minsters of secular priests. The stone fragments of interlacement reset at St. Mary the Less, which was until the mid-14th century known as the church of St. Peter without Trumpington Gate, suggest a late pre-Conquest foundation, and a 'Saxon coffin-stone' in St. Edward's (until 1939) may indicate an Anglo-Saxon origin for that church, but neither the stone nor details of it have survived. The dedications of St. Botolph and St. Clement have been adduced to support a pre-Conquest date for their foundation, but such evidence is inconclusive; the earliest references to both churches are very much later and the structures retain nothing earlier than the 12th and 13th centuries respectively.

The earliest post-Conquest fragment to survive in a Cambridge church is the late 11th-century chancel-arch of St. Giles reset in the new building of 1875. St. Giles was founded in 1092 as a priory of Canons Regular, the house referred to above, and the reset arch is doubtless a part of the original church. Of the old church of All Saints in the Jewry, given to St. Albans Abbey between 1077 and 1093, nothing survives but the churchyard opposite St. John's College; it was replaced by a new church in 1864 opposite Jesus College.

The 12th-century and later mediaeval churches include only three or four of particular architectural distinction but their range of form and the adaptation of plan to meet special requirements that they demonstrate are of high interest, in particular in St. Michael's. Holy Sepulchre is one of only five round churches surviving in any completeness in England, with the Temple church in London, St. Sepulchre's in Northampton, Little Maplestead, Essex, largely rebuilt (R.C.H.M., Essex, I, 184), and Ludlow Castle chapel; remains of others survive or have been excavated at the old Temple church in Holborn, St. John's Clerkenwell, Garway in Herefordshire (R.C.H.M., Hereford, I, 69), Dover, and Stoke Bruer in Lincolnshire. It may be observed that the Cambridge foundation is one of those that had no connection with either of the Orders, of Knights Templars and Knights of St. John of Jerusalem, that built round churches, and the dedication must account for the form, which is based upon that of the Anastasis in Jerusalem, (fn. 44) the dedication being, to the mediaeval mind, one of the outstanding characteristics of a church. In Cambridge a 'fraternitas Sancti Sepulchri', probably an early guild, was granted the building site (appropriately, and no doubt by design, a cemetery) between 1114 and 1130 (fn. 45) : the structure, though much restored, is of this period. The restoration, of interest in its own right, is referred to later. Part of the 12th-century tower survives at St. Mary the Less and the W. wall of the same age at Holy Trinity. For the rest, the remains of this period are even more fragmentary and consist of reused carved stones in St. Andrew the Great, St. Botolph, and St. Peter and, of this or the succeeding century, parts of wall-arches flanking the chancel-arch at St. Benet's; these recesses were presumably the settings for altars either side of the earlier chancel-arch. The 12th-century Stourbridge Chapel is referred to below with Hospitals.

Evidences for building or some rebuilding in the 13th century remain in seven Cambridge churches, St. Andrew the Great, the whole of St. Andrew the Less, a type of 'ecclesia juxta portam' of Barnwell priory, St. Clement, St. Edward, Cherry Hinton, Chesterton and Trumpington. Amongst these the church of St. Andrew the Less is an unpretentious building much restored in 1854–6 in the 13th-century style, and the only notable architectural work is the chancel of Cherry Hinton, with an impressive treatment of lofty shafted arcading along the side walls; the spacious nave of the same, of rather later in the 13th century, was rebuilt with the old materials late in the 19th century.

The 14th-century work includes three outstanding churches, of St. Mary the Less, mostly of c. 1350, St. Michael, wholly of the latter part of the third decade of the century, and Trumpington, mostly of c. 1330. The three show the widest variations in plan, spacial form and detail. The architectural detail is markedly simple at St. Michael's, typical of the period at Trumpington, and of mature elaboration at Little St. Mary's where identity of window-tracery design with that in the Lady Chapel of Ely Cathedral may be seen. Much of the spacious church at Chesterton is of the early 14th century; of the end of the century are the singularly elegant and subtly moulded nave-arcades of St. Edward's. Rather less distinguished 14th-century work survives in the naves of Holy Trinity, St. Benet, and St. Botolph. The chancel of St. Mary the Great is much remodelled and restored. St. Peter's, now only a fragment of a larger building, and Chesterton are the only two churches included in the Inventory with mediaeval spires, both of the 14th century.

Mention of special-purpose planning, in relation to St. Mary the Less and St. Michael, raises, together with that of St. Benet and St. Edward, the matter of local parish churches used for collegiate purposes, and this is discussed separately below in connection with the Cambridge College plan (p. lxxxvii). But space may be given here to the exceptional organisation of the rectory of Chesterton, which, though not affecting the church plan, has created a scattered architectural group. Henry III's gift of the church to Cardinal Gualo and the latter's bestowal of it upon his foundation of canons regular in the church of St. Andrew at Vercelli, who remained the appropriators until c. 1440, explains the existence of the 14th-century Chesterton Tower (Monument (305)). At Chesterton a proctor, probably a canon of Vercelli, represented the foreign house. A vicarage was ordained in 1273 but that the Tower was not the vicar's dwelling is indicated by the concession of land south of the church for a vicarage. The presence of both proctor and vicar at Chesterton is shown by the direction that 'all priests celebrating in the church are to obey the abbot's procurator and also the vicar, who has the governance of the church on account of the English tongue, and they are to do principal reverence to the procurator and secondary reverence to the vicar'. (fn. 46) Chesterton Tower is a building of architectural pretension, and the descent of its ownership set out in the Inventory leaves little doubt that it was the proctor's dwelling.

By far the most outstanding church building of the 15th century is St. Mary the Great, the University church. The only other works of the age of any importance are either additions to or rebuildings of older structures: they include the transepts of Holy Trinity, the aisles for college use at St. Edward's, the westernmost bay of Little St. Mary's and the W. tower of St. Botolph's. This last, fine in mass and silhouette, is a rustic product compared with the sophistication of St. Mary the Great, a lofty spacious building of the greatest assurance in execution and much decorative elaboration. Except for the earlier chancel and the later upper parts of the tower, Great St. Mary's gives the impression of a single coherent and carefully premeditated design. Begun in 1478, the major part was not finished until 1514. The nave has the closest stylistic affinities with that of Saffron Walden church and a contract for this last was drawn up in 1485, at Cambridge, with Simon Clark, mason (ob. ? 1489) and John Wastell, mason (ob. ? 1515). (fn. 47) Wastell succeeded Clark as master-mason at King's College Chapel and his work there is identifiable (see Monument (31)). He also built the Angel Tower of Canterbury Cathedral, where the decoration is closely reminiscent of some on the lowest stage of the Great Gate of Trinity College with which also he seems to have been concerned (see Monument (40)). The close net-like pattern of curvilinear forms in the strainer arches he introduced at Canterbury and in the elaboration of the chancel-arch and arcades of Great St. Mary's are informed by the same spirit of invention. Whether St. Mary's tower should also be attributed to him is conjectural; it may be noted that features of the ground stage are duplicated in the tower of Dedham church, Essex (see R.C.H.M., Essex, III, plan, p. 81), and that the lower part of the tower at Soham, Cambridgeshire, would appear to be by the same designer.

Cambridge churches retain little structural work of the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries except for the late 16th-century upper stages of the tower and the galleries and staircases of 1735 at Great St. Mary's. The elaborate 17th-century timber roof in Little St. Mary's was destroyed late in the 19th century. The importance of the works of the first half of the 19th century, and it is considerable, lies in the direction of ecclesiology rather than visual quality. The population of the parish of St. Andrew the Less rose from 252 in 1801 to nearly 10,000 in 1841; Little St. Andrew's church became inadequate and Charles Perry bought the advowson in 1835 and inspired the provision and endowment of Christ Church, 1839, and St. Paul's, 1842, to meet the needs of the parish; they became parish churches in 1846 and 1845 respectively. Both were hall-churches, aisled halls with only a shallow sanctuary, and, in that they thus departed, in the view of the Cambridge Camden Society, from the traditional setting of Anglican worship, St. Paul's and by implication Christ Church were mercilessly criticised by the Society in the first volume of its publication, the Ecclesiologist (1841). It was less severe with Great St. Andrew's, an elaborate and notable work of 1842–3, since it presented a tolerably ecclesiastical appearance.

The Cambridge Camden Society was founded in 1839 'to promote the study of Ecclesiastical Architecture and the restoration of mutilated architectural remains', and the work of restoration of Holy Sepulchre sponsored and financed by the Society, at a period when one of the chief tenets of ecclesiological belief was the superiority of Gothic church architecture of the 14th century ('Middle Pointed') over all others, is an interesting expression of the Society's dictum that architects should know enough of earlier styles to enable them to restore earlier churches. Here the work extended to rebuilding most of the later Gothic accretions, including the 15th-century polygonal lantern, which was recreated in the 12th-century style. The measure of the Society's approval is suggested by the inclusion of an impression of the church on their Corporate seal. The same restoration also made important liturgical case history, for the provision of a stone altar was disputed and the Court of Arches ordered its removal, the church being closed until a change was made. (fn. 48)

Religious Houses

By far the most important and extensive remains of a monastic house in Cambridge are those of the Benedictine nunnery of St. Radegund (see Monument (30)). The priory, founded between 1133 and 1138, was one of those nunneries suppressed by orthodox bishops in the years not long preceding the Dissolution by Henry VIII. It was dissolved and refounded in 1496 by Bishop Alcock as Jesus College, with the retention of most of the priory church and the claustral ranges. The church was cruciform with an aisled nave and the nuns' choir would probably have provided enough space for collegiate purposes; the preservation of the nave was doubtless due to its parochial status, though the aisles were demolished.

Some of the few foundations by black monks in England after c. 1200 were the conventual colleges at Oxford and Cambridge. Of Ely Hostel for monks of Ely and other Benedictine houses studying at Cambridge only a wall, and that not certainly identifiable as part of it, survives between Trinity Hall and Clare College where the hostel stood from its foundation after 1321 until moved on the foundation of Trinity Hall in 1350 (see Monument (41)). But of Buckingham College much survives. It was founded as a regular house of studies in 1428 on the initiative of Crowland Abbey, other Benedictine houses having the right of building rooms there for their monks. It was refounded in 1542 as Magdalene College, with the retention of many of the original buildings. Thus, though since much remodelled, the separate 'camerae' remain and may be compared with those at Worcester College, Oxford (R.C.H.M., Oxford City, 123–5); most notable is the survival in one building of the mediaeval internal arrangement, with common room, studies opening from it, lavatory and garderobe (see Monument (32)).

Mention has been made above of the house of Canons Regular by the Castle, one of the earliest foundations of the Order in England, and the possible remains of it (see Monument (52)). The canons moved to Barnwell in 1112 and there remained under the Augustinian Rule until the dissolution in 1538. The removal, with an increase from a foundation for a prior and six canons to thirty canons, is of interest in the context of the period, 1110–1160, when the greatest number of houses of black canons was founded. Of Barnwell priory valued at £256 11s. 10d. in 1534–5, only two bays of a 13th-century vaulted undercroft survive (see Monument (64)) and a part perhaps of the precinct wall (see Monument (270)). (fn. 49) The church of St. Andrew the Less, just outside the precinct, was served by the canons.

Nothing of the Gilbertine priory of St. Edmund for resident canons and some student canons survives.

A Dominican priory where Emmanuel College now stands was founded before 1238, one of more than forty houses founded within half a century of the Friars Preachers' arrival in England. Dissolved in 1538, some of the buildings survived and were used for Sir Walter Mildmay's college foundation of 1584 (see Monument (27)). That the Preachers' church and W. claustral range were retained, and were still recognisable in c. 1688 is clear from Loggan's engraving of Emmanuel College of that year. Although the former has since been remodelled almost out of recognition the structural evidence described in the Inventory seems to suggest a typical friars' church plan, with the nave, now containing the Hall and Combination Room, an altar against the east wall now of the Combination Room, and the same wall being the W. wall of a narrow tower interposed between nave and presbytery, the tower, except parts of the W. wall, and presbytery since being wholly remodelled or rebuilt. The claustral range was entirely rebuilt in c. 1770 but it was evidence for a cloister S. of the church; thus it is probable that the Westmorland Building of the College represents the position of the S. claustral range. The priory was intended for as many as seventy friars, implying an importance commensurate with Cambridge being one of the four Visitations into which the Dominican Province in England was divided.

Regarding other Mendicant orders in Cambridge, something of the buildings of the Franciscan, Carmelite and Austin friars is recorded or survives; those of the friars of the Sack were taken over by Peterhouse in 1307 and nothing more is known of them; the Pied friars remained for less than half a century and the Bethlehemites seem not to have become established. The Franciscan friary, founded in c. 1226, very shortly after the arrival of the Minors in England, was soon established where Sidney Sussex College now is. Granted after the Dissolution to Trinity College, the buildings were largely demolished and the material taken for the King's new foundation, but the efforts made by the University to obtain them for ceremonies indicate that they were of some size and pretension; indeed as many as seventy-five grey friars were recorded here in c. 1300. It is not without irony that Mary Tudor was using the building materials for her chapel at Trinity College. One building, carefully surveyed by James Essex, (fn. 50) which was probably the hall of the Warden's Lodging, survived until 1776 approximately in the position of the E. range of the present Chapel Court of Sidney Sussex College. The Carmelites moved in c. 1292 from Newnham to the N. part of the area now occupied by Queens' College and the N. wall of their church in part survives incorporated in the boundary-wall between that College and King's College (see Monument (35)). Here again such structural evidence as remains suggests an aisleless building with the oblong crossing usual in friars' churches between nave and presbytery. Of the Austin friars' house, founded in 1290, dissolved in 1538–9, only three rebuilt arches and some worked stones survive in the Arts Schools, which now occupy part of the site of the friary (see Monument (63)).

Less of the structures of the mediaeval Hospitals survives than of the monastic buildings. The Hospital of St. John the Evangelist founded in c. 1200 for the care of the poor and sick, with a Master, chaplain and brothers who adopted the rule of St. Augustine in 1250, was dissolved between 1509 and 1511 and the main buildings were incorporated in St. John's College (see Monument (37)). They were not demolished until c. 1869, by Gilbert Scott, and detailed records of them survive. (fn. 51) They comprised two long narrow buildings roughly parallel with one another on the N. side of the present First Court; they are imposed on the Commission's plan of the College (see plan in pocket at end of pt. II). The early 13th-century N. block contained the chapel in the E. end, the infirmary in the W.; it departed from the more familiar plan of the mediaeval hospital, which is reminiscent of the normal chancel and nave church, in being of constant width from end to end, without structural division between the 'chancel' (chapel) and 'nave' (infirmary). The S. building was at least as old as the late 13th century, and the smallness of the nave indicates that it was not a larger infirmary building but always the brothers' church. This again was of uniform width throughout but with an internal division in the form of an oblong crossing, doubtless rising into a tower. It is the plan of this later building which is now outlined in stone kerbs in the grass of the First Court of St. John's College.

The Hospital of St. Anthony and St. Eloy is perpetuated, but on a different site, by the almshouses of 1852 in St. Anthony Street. Of the Hospital for lepers established about the middle of the 12th century beyond Barnwell, the chapel, dedicated to St. Mary Magdalene, alone survives; it became a free chapel after 1279, without lepers. Such hospitals were placed near but not in the towns where leprosy was endemic and, for obvious reasons departing from the conventional mediaeval hospital plan, consisted of scattered houses about a common chapel. It is this last that stands at Stourbridge.

By definition under the heading of Religious Houses many of the Cambridge Colleges, the academic secular colleges of the Middle Ages, also come, but they are included in the Section below devoted to all the pre-1850 Colleges.