An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in the City of Cambridge. Originally published by Her Majesty's Stationery Office, London, 1959.

This free content was digitised by double rekeying. All rights reserved.

'Cambridge: The Growth of the City', in An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in the City of Cambridge(London, 1959), British History Online https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/rchme/cambs/xxxii-lviii [accessed 26 April 2025].

'Cambridge: The Growth of the City', in An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in the City of Cambridge(London, 1959), British History Online, accessed April 26, 2025, https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/rchme/cambs/xxxii-lviii.

"Cambridge: The Growth of the City". An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in the City of Cambridge. (London, 1959), British History Online. Web. 26 April 2025. https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/rchme/cambs/xxxii-lviii.

In this section

CAMBRIDGE THE GROWTH OF THE CITY (fn. 1)

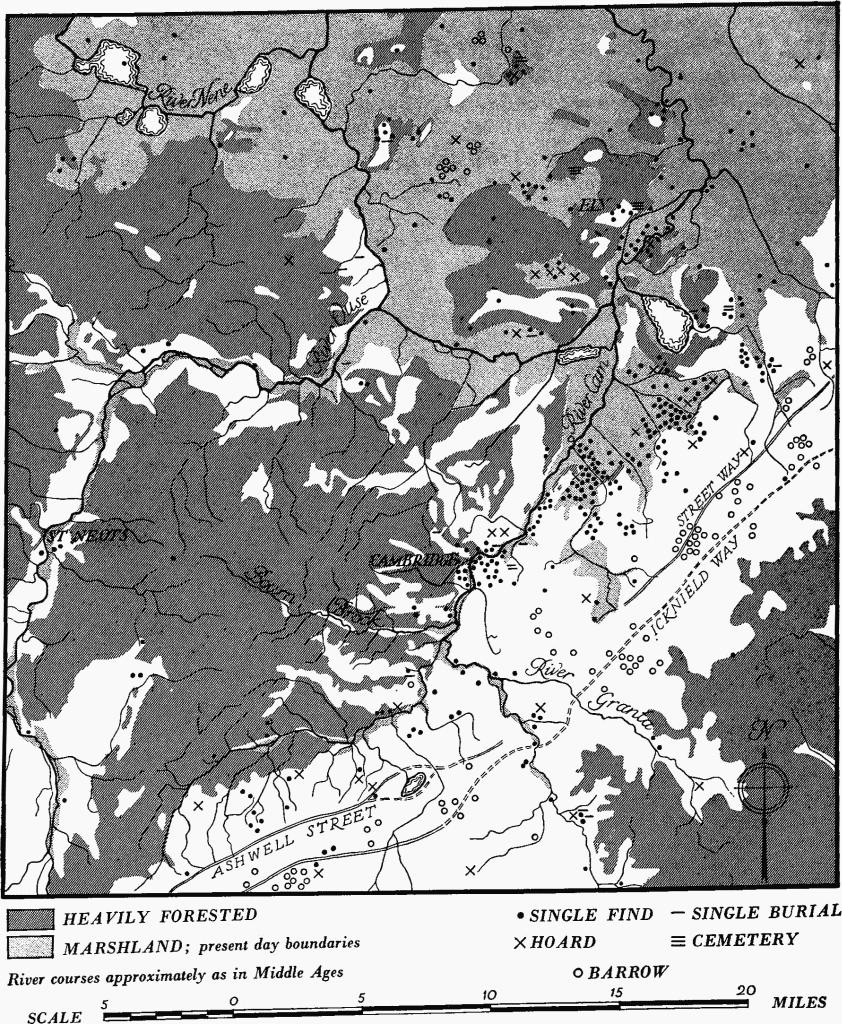

Physiographical Map Showing Bronze Age Remains in the Cambridge Region

The City of Cambridge has grown to its present size and dignity on a site that has many advantages for settlement, of a type well-recognised by geographers, and familiar to historians: at the point nearest to a sea where a slow-moving river can readily be crossed by ford or dug-out canoe, by ferry or bridge; that is, where there is hard well-drained ground on either side and where the alluvial flat through which the river meanders is reasonably narrow. (fn. 2) Such a crossing may be of use to enable a single community to exploit the land on either side for hunting, cultivation or trade, or to link two communities potentially or actually in a friendly relationship. The site of Cambridge, in the course of its history, has served both purposes. (fn. 3)

Since Cambridge is far from the sea (forty miles from the Wash) and at the most southerly point of the Fenland, it is an actual or potential nodal point of east and west land-traffic and one of the chief terminals of water-traffic on the Cam-Ouse river system.

These aspects are illustrated on the physiographical map p. xxxii, which shows the river system and the southern fens in relation to forested, or comparatively open, country. To complete the picture the maps on p. xlvii should be examined; they show the breadth of the river Cam and its various channels within the borough area, with the muddy soft fringes subject to floods under natural conditions, but now largely covered with dumped soil, and built over. This alluvial flat, it will be seen, is conveniently narrow at the site of the mediaeval (and Roman?) bridge, which is, in fact, the lowest crossing point practicable in early times.

The well-drained, habitable ground beside the river Cam at mediaeval Cambridge varies in character and elevation. On the right bank (S.E. side) it is a gravel spread, some 30 ft. above sea level at 'Peas Hill'; on the left bank (N.W. side) it is a localised gravel-capped outcrop of the Lower Chalk, steep-ended to the river at Castle Hill, where it is between 60 and 70 ft. above datum level. This dominating spur provides potential military control of the crossing and is an additional reason for the crossing being sited here in every successive culture phase from Roman times onwards: it is a point of strategic importance.

PREHISTORIC AGES, STONE, BRONZE AND IRON

The Phase of Diffuse Settlement

The few paleolithic finds in the Cambridge area are strays in natural deposits; the earliest occupation known to us, in the long phase of diffused settlement which preceded the foundation in Flavian times of the Roman town, is indicated by a find of late Neolithic grooved ware (c. 1800 B.C.) in a pit beside the Hills Road associated with flint flakes and ox bone. A well-known 'A' beaker burial at Barnwell and lesser finds from Chesterton and Cherry Hinton represent the dawn of the Bronze Age, which is illustrated in its early phase by a flanged axe from Barnwell and a food vessel and pygmy cup from Midsummer Common, and in its Middle period by isolated finds of palstaves and rapiers. It was, however, not until the Late Bronze Period (c. 1000–500 B.C.) that any considerable activity in this diffuse settlement is manifest. Two bronze hoards, one of which is illustrated in Plate 2, come from a gravel pit in Chesterton; their combined make-up well illustrates the range of tools and weapons available. There are 52 socketed axes, the all-round tool, mostly in perfect condition, 4 spears, a rapier (hangover from the previous period), a leaf-shaped sword, 4 gouges, a chisel and an awl, a twisted tore, 4 rings and 31 lbs. of metal. A bronze mould for axes found in New Street, Cambridge, suggests that there were bronze-workers here as well as traders in metal. These activities will have been maintained by a mainly pastoral and hunting economy.

The importance of the Roman and mediaeval site of Cambridge, suggested in the initial paragraphs of this Introduction, is in no way apparent, however, in the Bronze Age. Nor is it in the Early Iron Age which followed. A map (p. xxxviii) based on the Geological Drift map shows, to larger scale, by red symbols, the sixteen very widespread known sites of the period, seven on the W. side of the river, the rest on the E., covering an area of some 20 square miles. The evidence of human activity they provide, however, is of course more massive; they include three banked enclosures, of which one is a hillfort, pits and ditches and a cemetery. All these occupation sites, like the few of earlier periods, are on the soils naturally open or lightly forested. Some ill-documented finds may have come from the river alluvium (having been dropped overboard).

The physiographic map referred to in the introductory paragraph has been overprinted to illustrate the diffused settlement phase of the early history of the City area and the region adjacent. (fn. 4) It shows that the aggregation of finds of the Bronze Age in the City area is but a part of those spread out along the water and fen-side in Cambridgeshire, from Barrington to Horningsea, and that there are no find-sites to the W. of Cambridge that suggest a more than local significance (i.e. the presence of small patches of open country).

The explanation, as is well known, lies in the geology of the county; western Cambridgeshire is almost entirely a countryside of heavy claylands of the Mesozoic period, wet underfoot and densely forested in early times: such country moreover extends many miles beyond the county to the valley of the Ouse at Huntingdon. Patches of better-drained soil in this great area are local and lie mostly to the N. and N.W. of Castle Hill, and in the Bourn Brook valley, as the map shows. No through east-west traffic to the midlands was, we may affirm, possible in the area in prehistoric times, even if it were advantageous.

This does not imply that Cambridge is on a site isolated from early trade, we know that it was not, nor that the settlement area was difficult to reach or leave in Bronze Age times; it was widely open to traffic on the E. The slow-moving river was easily crossed in dug-outs by those who lived on the left bank, from Castle Hill to the St. John's salient where the later bridge was sited. Few prehistoric centres of occupation in Britain had a more important, easier, line of through communication than that provided by the bundle of tracks later called the Icknield Way, extending northwards to the Brecklands, the sea-coast, and Norfolk generally, and south-westwards to the Thames at the 'Goring Gap'. Thence, by the Berkshire Ridgeway, packmen and tribesmen could reach the nodal area of South Britain in this Age, namely Salisbury Plain. (fn. 5)

A journey such as this, from north to south, was, for nearly all the way, on the Chalk outcrop; and it is, in Cambridgeshire, on the western margin of the belt of well-drained light soil easily cleared of scrub which this rock produces, where springs well out, that most of the early inhabitants of our county will have lived, as the map p. xxxviii suggests. Here, in particular, the inhabitants of the eastern riverside settlements at 'Cambridge' must have kept the flocks and herds that could not be accommodated on the gravel spreads near the river (fn. 6); here a scratch agriculture no doubt developed—precursor of the 'Celtic' fieldsystem in our area.

We now turn to the Early Iron Age (500–400 B.C. to the Roman Conquest, A.D. 43), the phase when settlement in the region seems first to have had its principal focus on the 'Cambridge' area. This is suggested not so much by the bulk of the material as by the contrast that the overall pattern of finds of this Age in the district makes with that of the Bronze Age. The fen borders to the N., then, as we have seen, packed with finds, were in the early Iron Age almost completely evacuated, (fn. 7) while the occupation of the Cambridge area continued.

Early Iron Age 'A' pottery in the primary silting of 'War Ditch' (Monument (3)) denotes settlement on the chalk ridge above Cherry Hinton. That from Trumpington, again indicating settlement, is coarse and ill-fired, showing both angled and rounded shoulders and ornament characteristic of this initial phase. (fn. 8) A pit or ditch ¼ mile S.E. of Red Cross, the largest of many exposed by a wartime cutting (but not necessarily of the same period), yielded a trapezoidal bronze razor probably assignable to the earliest Iron Age (c. 500 B.C.). This came from the same level as rough pottery fragments not closely datable themselves. (fn. 9)

The Early Iron Age 'B' culture, here dating c. 250–30 B.C., of very different character from 'A' was, as is well known, introduced into Britain by a chariot-using aristocracy probably from the open uplands bordering the river Marne in northern France. This ruling caste is well represented by a man of rank who died in middle age and was buried close to the left bank of the Cam at Newnham Croft. His skeleton and grave-goods were discovered in 1903 (fn. 10); the latter, though not numerous, are personal enough to make him live again for us to-day. The coral-enriched brooch no doubt secured his cloak on the right shoulder, the two penannular brooches his tunic; the cast-bronze ring with delicate wreathed scrolls in relief (dating in the late 3rd century B.C.) worn on the left upper arm(?) and the brooches would be seen as he handled his ponies from the open chariot-front (fn. 11) and the cloak blew clear. On one of these galloping ponies the bronze cap with noisy dingle-dangles poised above the head-harness would perhaps have been worn. Here then, we have a landowner of the period, who presumably lived and died in an Iron Age 'B' homestead or village, close to the burial place.

The 'pedestal' vases, 'barrel' and 'butt' urns, tazzas and platters, pottery characteristic of the 'Belgic' Iron Age 'C' culture of the late 1st century B.C. onwards to the Roman Conquest, are represented by finds at Chesterton, Madingley Road and 'War Ditch', Cherry Hinton; other objects worthy of mention here are a bronze dagger-sheath, a cheek-piece of a pony's bit from 'Cambridge' and an Italo-Greek amphora (wine-jar) found in Jesus College Garden.

This 'Cambridge' settlement, in Belgic times, was in Catuvellaunian territory, and the control of its inhabitants will have been centred at Verulamium (St. Albans) in the time of Tasciovan (30 B.C.—A.D. 5) (fn. 12); his famous successor, Cunobelin (A.D. 10–40), ruled in Camulodunum (Colchester), the former chief town of the Trinovantes, 40 miles to the S.E. (fn. 13)

THE ROMAN PERIOD c. A.D. 43–410

Concentration of Settlement Begun

The evidence for a civil settlement of the Roman period on Castle Hill, in a 'four-sided enclosure of some 28 acres' (25 is perhaps more correct), has not been materially altered since 1922, (fn. 14) although the present work has provided the opportunity for a fuller statement (see Sectional Preface). The coin series, largely that of 168 coins recorded by John Bowtell, (fn. 15) begins with a few pre-Flavian issues, is fullest for the 3rd and 4th centuries, and ends with Arcadius and Honorius. The evidence that made it possible to attribute the beginning of effective occupation to the Flavian period (c. A.D. 70) has been augmented by the examination of some 200 pieces of decorated 'Samian' pottery in the University Museum, none of which was pre-Flavian. (fn. 16) Material from Barge Yard (London) was erroneously taken into account in 1922.

Deep excavations in 1929–30 for the foundation of the Shire Hall added to our knowledge; these revealed traces of what was apparently an earlier ditch (Monument (14)), on a rectangular alignment on the S. and E. sides of the spur, yielding pottery comparable with Claudian material from Camulodunum, so we may surmise an initial military post to control the crossing. (fn. 17) No adequate examination was however possible.

The approximate line of the defences of the later civil settlement (plan, p. lxi) has long been recognised, but it can now be seen that the scarp in the grounds of Magdalene College does not form part of it, and the position of the ditch has been fixed with certainty at one point on the S. rampart. The excavation at this latter site (Monument (15)) has also indirectly confirmed Bowtell's recorded discovery in 1804 of a masonry wall contained within the ditch. This was probably a 4th-century addition to the defences, but evidence of the buildings that these enclosed is still lacking. Whatever the significance of the earliest occupation on the site of the Shire Hall, the settlement probably was, for most of the period it covered, a 'road junction of local importance', and a rural township mainly 'built of wood, clay and thatch', (fn. 18) with the necessary corollary of Roman causeways and a bridge across the 300 yards of marsh and stream below it. (fn. 19)

No evidence has so far emerged that any important landed family of Celtic stock lived in or near 'Cambridge' in the period, nothing comparable to the family whose representatives were buried in such a noble fashion at Bartlow on the Essex border 12 miles away. It seemed at one time likely that we should seek the local administrative centre elsewhere, perhaps at Great Chesterford, Essex, 10 miles to the S.E., but excavations in 1949 have shown that the 1st-century settlement was a small one, and that the town was not walled until the 4th century. (fn. 20) 'Cambridge' therefore, with its considerable population, remains the chief centre in the district as the distribution map in The Archaeology of the Cambridge Region demonstrated.

That the Castle Hill site on the Cam may have attracted the attention of the Roman command at the time of the Conquest was to be expected: that the Romano-British town which grew up here was comparatively unimportant is to be connected, probably, with the failure of the Roman civilisation and the Roman administration in the centuries of its power, here as in Britain generally, to bring the forested clay-lands into cultivation. The distribution map in Archaeology of the Cambridge Region suggests intensive Romano-British occupation on the south-facing slopes of the Bourn Brook valley and for a mile or two westward on the upland beyond the settlement; otherwise finds of the period in the western forest areas, 16 miles across, are few.

Civilised occupation of the gravelly river terraces on both banks of the Cam, outside as well as inside the present City boundary, is well attested as the above-mentioned map and the accompanying map, p. xxxviii, show. This must be in part related to the Roman administration's appreciation of the position of the little township at the head of navigable water, referred to already. Striking evidence of this is the construction in Neronian times (fn. 21) of the Car Dyke starting in fenland 6 miles below Castle Hill, and serving as a traffic route to the N. The development of the southern fenlands for agriculture, possibly as an act of Imperial policy, is perhaps exemplified in our area by the extension of occupation to the loamy gravels N.E. of Castle Hill; this does not seem to have begun before the second quarter of the 2nd century A.D. Lastly the number of finds in the area generally indicates a considerable settlement; the concentration here, compared with any other part of the county, is remarkable, (fn. 22) but it must be admitted that the quality of Romanised native life in the Cambridge centre was low.

This concentration raises the problem of the road-system in the area, traditionally centred on ' Cambridge'. This has been studied by many scholars, the results of whose work were embodied with modifications in The Archaeology of the Cambridge Region. (fn. 23) Later work aided by air-photographs has tended to confirm the alignments therein set out, first of the Akeman Street, branching from the Ermine Street (Braughing-Royston-Huntingdon) at the crossing of the Cam near Croydon, which enters, at a point not yet defined, the S.W. side of the Roman town and continues therefrom N.N.E. into the Isle of Ely; second, of the road from the S.E., presumably from Camulodunum, the course of which has been established at Ridgewell in Essex, and is manifest on the Gog Magog Hills; its position has been determined in two places in the Perse School Grounds, and there is no reason for doubting that it crossed the Cam close to the present bridge. From the Roman township to Godmanchester and the crossing of the Ouse, the straight course of the present highway has obliterated its remains, and the evidence is limited to the coincidence of parish boundaries, to the discovery of Roman milestones in 1812, and to Roman burials beside it at either end, Godmanchester and Cambridge. The meagre records of finds in between emphasises what has been said of the occupation of the forested clay-lands (fn. 24).

Physiographical Map Showing Iron Age, Roman and Saxon Remains in and Near Cambridge

The suggestion (fn. 25) made before the discovery of mid 1st-century remains at Castle Hill that the early Roman ford was near Grantchester is no longer valid. The road by-passing Cambridge but passing through the present boundary of the city in Trumpington, and indicated by a broken line on the map in The Archaeology of the Cambridge Region, seems however to have crossed the river further N. than was formerly supposed; and the earthwork at Grantchester is not Roman.

Study of the limited data provided in the Cambridge area by chance finds, geological and archaeological research thus leads us to tentative conclusions that illumine that astonishing irruption (temporary, but sustained for three and a half centuries) of a gifted, civilised but ruthless Mediterranean people into our confused and barbaric, though politically complex, affairs.

ANGLO-SAXON 'CAMBRIDGE'

The Pagan Period c. A.D. 450–650

When we lose sight of the 'Cambridge' area at the end of the 4th century it was extensively occupied by Romanised Britons; when approximately datable material reappears, perhaps 50 years later, the occupants are 'Anglo-Saxon' invaders who have apparently replaced them. The material evidence is almost entirely the grave-goods of newcomers, in large and small cemeteries, but the survival of many of the earlier inhabitants, in a servile condition, is strongly suggested by the 'Romano-Saxon' form of some of the pottery vessels. (fn. 26) The other Roman crafts, however, certainly disappeared, for the small metal objects of that civilisation found in barbarian graves (fn. 27) will surely have been picked up here and there by the newcomers.

The map p. xxxviii shows the sites of the cemeteries and the probable centres of settlement: the former are discussed in detail in The Archaeology of the Cambridge Region. (fn. 28) Burial is, from the first, both by cremation and inhumation. On the left bank of the Cam are the important cemeteries of St. John's College Playing Fields and Madingley Road, perhaps one site, and that at Newnham Croft. The last suggests that this gravel terrace was continuously occupied from the Iron Age 'B' phase (p. xxxv above). A cemetery just outside the City area, at Girton, not shown here, is important and grave-goods from Chesterton are known. There was probably also a cemetery near the S.E. corner of the Roman township, material from which slipped, through erosion, into the bed of the river. On the right bank of the Cam interments in the area of the mediaeval town (in Jesus Lane, Sidney Street, Rose Crescent, and Trinity Hall) form a cemetery site on ground then open across the spur (of made ground?) leading to the Roman ford or bridge. There were also on this side, as on the other, outlying groups of graves.

The left-bank cemeteries, Girton, St. John's and Newnham Croft, characteristic grave-goods from two of which are illustrated by individual burials on Plate 3, date back to the 5th century, and show that the settlers had close connections with Slesvig in Denmark and the adjacent Saxon lands between the Weser and the Elbe. Cruciform and long brooches (as on Plate 3), equal-armed fibulae and some urns go back to the mid-century, c. 450. There is no difference between the scantier grave-goods on the right bank of the Cam, and these all represent 'Anglian' settlement of the same phase, as is well shown by a mid 5th-century brooch from the cemetery at Trumpington.

To sum up: the settlement on the left bank will have been mainly on or near Castle Hill and may have included a surviving Romano-British element. On the right bank the newcomers, on the evidence, will have occupied the centre of the later (mediaeval) town, somewhere in the area of Great St. Mary's to St. Benet's churches, as well as the Trumpington gravel-spreads. Viewed as a whole the settlement illustrates the economic pull exercised at this little centre of a higher civilisation to which the newcomers were hostile or indifferent, and makes probable the persistence, to some extent, of that Roman road system of which we have so little direct evidence.

The Early Christian Period (7th to 9th Centuries A.D.)

The latest dated objects in the group of cemeteries we are considering belong to the 7th century, when Christianity was replacing Pagan beliefs. Late in that century, as Bede records, monks from Ely fetched from the 'waste chester' ('Grantacaestir') a stone coffin, similar no doubt to those on Plate 1, for the burial of the foundress of their monastery, St. Etheldreda. In the 12th century the site of this Roman burial was defined as 'Armeswerk', which is a known enclosure protected by a watercourse, possibly artificial or an early course of the river Cam, north of 'Great Bridge'.

The story, with its hint of depopulation of the Dark Age settlements, illustrates stresses which developed in the communities we have defined. The forests, it will be recalled, may never have been cleared in our part of Roman Britain and we may be fairly sure that the road system linking Camulodunum with Ermine Street at Godmanchester had fallen in the 'dark centuries' into disuse as a through route, and that one of the breaks was to the west of Cambridge. The inferred destruction of a settlement on Castle Hill may be connected with the merging of the Middle Angles between the rivers Ouse and Cam, in the Mercian kingdom. Penda (626–655) is likely to have carried this through, despite the security provided by the environing 'Dark Age' forest, for he could have come in on the open (eastern) flank after his victory over the East Angles in 634. The East Anglian kingdom then came under Mercian hegemony—at first intermittently; and therefore the community of the right bank, on the theory here set out, will have also been under alien control. In the next century we may with some assurance place the building (or rebuilding) of the bridge uniting the 'Dual' settlement (fn. 29); its builder is likely to have been King Offa (756–793) who was in full control of the affairs of East Anglia. Grantebrycge is first referred to in the Anglo-Saxon chronicle annal for 875, a record which is nearly contemporary; it is one of the earliest known uses of the term 'bridge' in the language.

Finds of this Early Christian phase in Cambridge are very scanty; as T. C. Lethbridge remarks, graveyards of the period may well have escaped notice by reason of the poverty of their contents (fn. 30); this may be the case at Cambridge itself. The only important finds are a gilt-bronze disc, part of a trio of pins linked together (suited to a well-born lady, as is seen in the Lincoln example in the British Museum).

ANGLO-DANISH CAMBRIDGE

The Viking Settlement c. A.D. 875–1066

The Chronicle records under the year 875 that the Danes wintered at Grantabrycge; three years later, by the treaty of Wedmore, it passed into the Danelaw. The army (here) which belonged to Grantabrycge is mentioned in the Chronicle under 921 when the Danes submitted to King Edward the Elder, and the Anglo-Danish town was burnt in the most formidable of the northern invasions (A.D. 1010), that which placed Svein, followed after an interval by Cnut, on the throne of England.

If a town is a good trading centre, such destructions in those days would be quickly put to rights. The buildings will have been of cob, or wood-framing with wattle and daub, roofed with thatch: all local materials easily obtained. Recent research (fn. 31) has indeed suggested that Cambridge was flourishing (at intervals, necessarily) in the 10th and early 11th centuries, pottery of this range of date having been found on many sites on the right bank. It was thus a matter for surprise that none was found during the excavations on Castle Hill in 1929–30 (p. xxxvi, above). 'We must look for the "late Saxon" settlement at Cambridge, the Danish burgh, on the right bank of the Cam'. (fn. 32) It occupied, it is now fairly certain, much the same area as was protected in early mediaeval times by the King's Ditch, which may indeed have been originally dug at this time. Miss H. M. Cam's paper on the origin of the borough of Cambridge (1933) (fn. 33) takes into account these discoveries, and summarises the new outlook thus attained; the ancient settlement on the left bank was commercially unimportant. (fn. 34) Cambridge was then definitely a seaport, and the wharves of the oversea traders—'Irish merchants' (? Danes from Dublin)—were in the right-bank quarter suitably known as the Holm, where the church of St. Clement now stands. It was, no doubt, the trade-wealth of this right-bank community that made possible the building of St. Benet's church in about A.D. 1025 (p. 263, below) and other of our early-founded churches, since rebuilt.

Cambridge, it should be added, had a mint in the 10th century: down to the time of Edward the Confessor coins were struck bearing the abbreviated place-name Grant.

The unimportance of the ancient settlement in the Castle Hill area was, as has been implied, comparative; the number of houses on the Hill destroyed when Cambridge Castle was built (see below) shows that it was by no means negligible, as does the remarkable series of monumental sculptured stones of 10th and 11th-century date found under its bailey bank in 1810 (see Monument (77)), the site being almost certainly a graveyard though a church hereabouts is not known. Four of these stones, one of a 'coped' style derived from 10th-century Wessex, the others upright gravestones, all decorated with interlaced work, are illustrated on Plate 28. (fn. 35) The group suggests an old minster, the predecessor of Sheriff Picot's foundation.

Many well-to-do local families are surely involved in such a find as this, of no less than nine carved stones. The style was widespread in East Anglia, but among the Cambridge examples are the best and earliest of the group; there are some also in the shire, and the craft that all these represent will surely have been centred in the town.

The Immediate Effect of the Norman Conquest: A.D. 1066–68

The latest of the gravestones referred to in the previous section are of mid 11th-century date; they bring us to the Norman Conquest. The full effect of the battle of Hastings in 1066 on the community at Cambridge was felt in 1068; for after the surrender of York in that year King William came south, raising en route castles at Lincoln, Huntingdon and Cambridge as Orderic records. St. John Hope wrote a classic paper half a century ago on the motte-and-bailey structure of our 'Castle Hill', which he identified as the Conqueror's earthwork (fn. 36); as he concisely remarked 'it controls the waterway, commands the bridge, and dominates the town'. Twenty-seven houses in two wards were, we know, destroyed to make room for it; it ensured that the responsibility for law and order in Cambridge, exercised hitherto, no doubt, by leading trading families on the other side of the river, was manifestly royal; we know that the hand of William's Sheriff, Picot, lay heavy on the community. Its construction permanently centralised here the control of the shire.

'He raised castles at Huntingdon and Cambridge'. At long last, through the unrecorded activities of Anglian (followed by Danish) freemen in the 8th to the 11th centuries, the woodlands which we have often referred to had been heavily reduced, villages built, open fields created, parish boundaries defined, and, no doubt, 'broken men' and thieves liquidated throughout the whole of western Cambridgeshire (and East Huntingdonshire); much of this achievement is recorded in Domesday Book. By the Roman road, then, or a track from Huntingdon (possibly indirect, from village to village, but through open country) William will have come to Cambridge; the castle he built here is evidence of his appreciation of the township as one of the two strategic key-points (now with good inter-communication) on the southern margin of the Great Fen. What the Roman (Aulus Plautius?) doubtless had in mind in Claudian times, the Norman achieved a thousand years later, and thus made possible the future prosperity of the borough.

C.F.F.

FROM THE NORMAN CONQUEST TO 1850

The Conquest to c. 1200

The heavy hand of Sheriff Picot appears in the Domesday account of the town in increased requirements of services and greatly increased heriot demanded from the Lawmen, whose presence in Saxon times is an interesting indication of the status of the town. Domesday shows Cambridge divided into ten wards and gives particulars of each, except for the 6th ward which seems to have been omitted accidentally. (fn. 37) In addition to the twenty-seven houses destroyed in the 1st ward to make room for the castle, eleven burgages are described as waste in the 3rd ward and twenty-four in the 4th. Mr. Salzman in the Victoria County History (fn. 38) suggests that this may imply a fire. The situation of the wards, except for the 1st where the castle was built and the 2nd which is referred to in the Inquisitio Eliensis as 'Bruggeward', is obscure though the presence of a church belonging to the Abbot of Ely in the 4th ward may provide a further hint, as St. Botolph's is the only church in Cambridge whose earliest known patron was Ely. The largest ward is the 1st with fifty-four burgages and Domesday states that before the destruction of the twenty-seven houses to make room for the castle it was reckoned as two wards; the second largest was the 5th which had fifty burgages in King Edward's time when it was presumably the largest. Three mills are mentioned as having been made by Picot and many houses are said to have been destroyed in the process. A mill of the Abbot of Ely is also mentioned, presumably the Bishop's mill of later times. The most significant fact that emerges from the survey, which is a fiscal survey, is the relative importance of the town within the county; as Maitland points out, it paid ten times what the ordinary Cambridgeshire village would pay. (fn. 39)

The predominance of the Sheriff in his castle over the town of Cambridge in the late 11th and early 12th centuries led directly to an important innovation in the ecclesiastical life of the town. In 1092 the Sheriff Picot established a house of Regular Canons, consisting of a church dedicated to St. Giles and accommodation for six canons hard by the castle to the south. Picot's successor greatly increased the foundation and removed it in about 1112 to a new site outside the little town, to the north-east, at Barnwell where, as a house of Augustinian Canons, it became one of the most important factors in the life of the place throughout the Middle Ages. (fn. 40) A second religious foundation, also outside the town in the same direction as Barnwell, was a house of Benedictine Nuns apparently established at the very end of Henry I's reign or in the first years of King Stephen. (fn. 41) The nuns' church and conventual buildings which now form the nucleus of Jesus College are the most substantial remains of a religious house surviving in Cambridge. The ground on which the existing church was built seems to have been given by Malcolm, King of Scotland and Earl of Huntingdon, between 1159 and 1161, but it is believed that the nuns had been settled hard by this site from the beginning, some twenty-five years before.

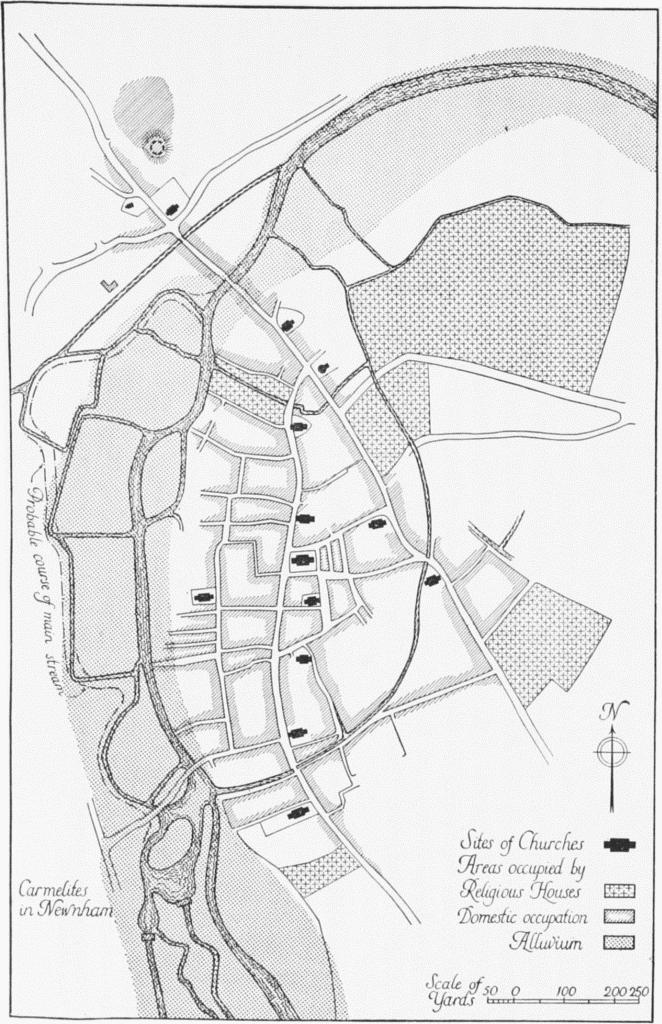

The establishment of these two substantial religious houses alongside the high ground that carried the road from Bury St. Edmunds (later known in the appropriate parts as Barnwell Causeway and St. Radegund's or Nuns' Lane) led to a considerable suburban development in this direction. Two village groups grew up adjacent to the two foundations and like them separated by a belt of open land consisting of Midsummer Common (Green Crofte in the early documents) and the fields to the south of it, and it is worth noting that Barnwell Priory was certainly built on common land, the Nunnery possibly also. Early in the 13th century the existing church of St. Andrew the Less was built, presumably to serve the needs of the more distant of the two hamlets, though we have no real evidence, documentary or archaeological, of the relation of this building to the canons' precincts. About the middle of the same century a parish of St. Radegund was formed adjoining the site of the Nunnery to the south and the nave of the nuns' church served it as a parish church. It seems probable that these two north-eastern parishes were the most populous of the suburbs but we have little detailed knowledge of them and they do not appear on the 16th-century maps.

Beyond Barnwell to the eastward was yet another religious foundation, the Leper Hospital. (fn. 42) Though there is no documentary evidence of its existence earlier than 1169, the existing chapel associated with the hospital seems to date from the mid 12th century. The hospital stood close to the site of Stourbridge Fair which was to become so important a local, even national, event and which survived until almost modern times. The first documentary reference to a fair in this neighbourhood is believed to be a grant of King John to the hospital in 1210–11 and this probably implies the grant of a going concern. (fn. 43) The commercial importance of the town was clearly growing in the 12th century, and there is an undated writ of Henry I (fn. 44) forbidding ships to discharge at any hythe in the shire other than Cambridge and requiring that toll shall be taken there and there only. By the end of Henry II's reign the townsmen were able to buy the farm of the town from the King, though their position over against the Sheriff was not finally consolidated till the reign of King John. The prosperity of the town is also suggested by the founding and building of churches by townsmen 'sometimes clubbing together in a gild', to use Maitland's words, and by the foundation by a townsman about 1200 of St. John's Hospital served by a Master, chaplain and brethren. (fn. 45)

The town itself, excluding suburban developments, was bounded to the S. and E. by the line of the King's Ditch; how early it was so defined is uncertain though there must have been a ditch before Henry III improved it in 1267. (fn. 46) The ditch left the river just S. of the site of Queens' College; it was crossed by the Trumpington Road at the corner of Mill Lane and by the Hadstock Road just N.W. of the site of Christ's College: thence it passed through what is now the garden of Sidney Sussex College, beyond which it was crossed by the Bury St. Edmunds Road, and joined the river again near the site of the electric light works (see maps, p. xlvii). The area so enclosed was far from being completely built up in early mediaeval times and can conveniently be considered in four parts: the nucleus of the town was round the Market Place lying between the High Street (now King's Parade and Trinity Street) and Conduit Street (now Sidney Street): there was a small concentration of houses in St. Clement's parish at the bridge end in the N.W. corner of the area: between these two was what has been described as a 'green belt' in the parishes of St. Sepulchre (earlier called St. George's) and All Saints, which had been filled up with houses by the latter part of the 13th century. The fourth part was originally the land behind the houses on the W. side of the High Street, between it and the marshy land by the river. After the building of the new Mills in the later 11th century, it seems probable that the main course of the stream tended to take a line more nearly that of the present day, nearer, that is, to the hard ground on which the town is built, with a consequent increase in the importance of the land along its right bank. (fn. 47) The built-up area beyond the river, Castle End, was bounded to the N. and E. by the Common Fields of the parish of Chesterton in which the Castle itself was situated, and by the northernmost of the Western Fields of Cambridge to the S. and W. The boundary between Chesterton Field and Cambridge Field ran along the Huntingdon Road from a point less than half a mile north of the Castle.

The evidence on which this pattern of growth is based is, in the main, the number of houses in each parish liable to contribute to the fee farm of the town as given in the very full account of the town in the Hundred Rolls of 1279. (fn. 48) As the total amount paid in at that time is almost unchanged since 1086 and each house is enumerated and its liability stated, a picture of the growth of the different parts of the town in the two hundred years between Domesday and the 1279 survey can be obtained. The figures are 63 being liable out of 212 houses and shops in the central parishes, 15 out of 40 in St. Clement's parish and 3 out of 22 in St. Sepulchre's and All Saints' parishes. In the Castle End, 22 out of 73 houses were liable in 1279 and in the suburbs, including Barnwell and Newnham, only 8 out of 153 houses. The parish churches founded in the late 11th and the early 12th centuries give substance to this pattern of development. St. Peter's (now Little St. Mary's) stands outside the ditch on the W. side of the Trumpington Road and some fragments of the 12th-century building have survived; St. Andrew's is immediately outside on the Hadstock Road. There are two parishes in the 'green belt', St. Sepulchre's, a building of the early 12th century, and All Saints' Jewry, removed to a new site in the 19th century. Most significant of all is St. John Zachary's which is referred to in a document of the beginning of the 13th century now at Jesus College. (fn. 49) This is particularly interesting as Milne Street where St. John's stood formed the backbone of the area between High Street and the river. It ran northwards, parallel with High Street, from a point near the southern junction of the ditch with the river, hard by the two ancient and long surviving mills, the King's Mill and the Bishop's Mill, from which it may have derived its name. Where Milne Street reached the point where the Queen's Gate of Trinity College now stands, it turned east to join the High Street, the eastward extension being called St. Michael's Lane (now Trinity Lane). The general line of Milne Street was continued northwards by a lane called by Dr. Caius Foul Lane, till it met another cross-street leading from High Street to the river from a point near the present Great Gate of Trinity College. Along the riverside a series of hythes was formed served by lanes leading from Milne Street and from the northern part of High Street. The line of Milne Street followed the edge of the alluvium (see map, p. xlvii), and it was the taking into use of the made ground along this strip that brought about the development of the new street and neighbourhood which the church of St. John Zachary served. At the extreme northern end of the alluvial strip within the town was the site of the Hospital of St. John, which was said to have been a 'very poor waste place of the community of the town of Cambridge' before the Hospital was founded there about 1200.

Round the perimeter of the town to the S. and E. and across the river from the new hythes above the bridge were the celebrated dual field systems made famous by F. W. Maitland, the Barnwell Field and the Cambridge Field. On the evidence of the distribution of tithes among the parishes of the town, those of the Barnwell Field mainly paid to churches in the right bank town and those of the Cambridge Field to those in the Castle End. Visible evidences of the cultivations of the Cambridge Field can still be traced on the ground (fn. 50) and both Fields are admirably shown in Loggan's general views of the town from E. and W. (Plate 4).

c. 1200 To c. 1325

The 13th century is perhaps the most important in the history of Cambridge. In the early years the Charters of King John (1201 and 1207) (fn. 51) finally consolidated the position of the town as a corporation, and in 1215 there is a reference in the Close Rolls to the enclosing of the town which may well refer to the beginnings of the actual ditch that Henry III improved in 1267 and which was certainly known as the King's Ditch before that date. Among the 1267 improvements were the construction of gates at the points where the Trumpington and Hadstock Roads crossed the ditch.

More significant even than King John's Charters is an entry in Roger of Wendover which speaks of a migration of scholars from Oxford to Cambridge in 1209. (fn. 52) This is the first reference to such a body of men in Cambridge, and whether this is the origin of the University or whether the migrants came to join an already existing body is unknown. The second document in the history of the University is a reference to the Chancellor in the transcript of a deed of 1226 now at New College, Oxford, (fn. 53) and the third and most important a writ of Henry III to the Sheriff of Cambridgeshire in 1231 directing him to punish contumacious scholars by imprisonment in the county gaol or by expulsion from the town, but only at the discretion of the Chancellor and Masters of the University. (fn. 54) Further, two Masters of the University were to be associated with two townsmen in the assessment of the rents of all hostels where scholars lived 'according to the custom of the University'. For the first three-quarters of the century the presence of the University seems to have left no trace on the topography of Cambridge. The hostels were at the most boarding houses established by individual Masters, except for two properties given to the University by Roger de Haydon before 1279 which stood one on the site of Pembroke College, just outside the new Trumpington Gate, and one in the site of the present Chapel of Corpus Christi College. More important than these was the site given to the University by Nigel de Thornton about 1275, (fn. 55) on part of which the Old Schools was eventually built (the earliest part of the structure to be undertaken seems to date from the mid 14th century). (fn. 56)

These early endowments of the University were small matters from a topographical point of view compared with the great changes which came with the introduction of the Mendicant Orders, itself a factor of great importance in the early development of the University as a learned Institution. The first to come were the Franciscans who arrived in about 1226. They settled first near the present Guildhall and were very modestly accommodated until they moved to the site of Sidney Sussex College in the 1270s. (fn. 57) On the new site they built themselves a large hall of which the University made use for important ceremonies until the mid 16th century. The Dominicans seem to have been settled in their final home (now Emmanuel College) much earlier, for the King gave timbers for the building of their Chapel in 1238, and in 1240 a document authorising them to enclose a lane near their Chapel seems to imply that they were not newcomers to the site. The Carmelites first came to Chesterton in 1249 and not long afterwards removed to Newnham where they remained till the last decade of the century when they established themselves on a site now divided between Queens' and King's Colleges, the existing boundary wall between these two Colleges being the N. wall of the conventual church. (fn. 58) The Friars of the Sack (or of Penitence) who arrived in 1258 soon acquired substantial premises on the W. side of the Trumpington Road beyond the church of St. Peter, as gifts from prominent townsmen, especially the Le Rus family. They seem to have gained considerable reputation in the University before their suppression in 1307. A fresh influx of Religious Orders came in the last ten years of the century when the Austin Friars established themselves on a site to the E. of St. Benet's church in the heart of the town. (fn. 59) At about the same time the Friars of St. Mary appear at the Castle End (they too disappeared in about 1320) (fn. 60) and in 1290 the Gilbertine Canons of Sempringham were given a large property, including the Chapel of St. Edmund, by a lady of the St. Edmund's family, another prominent Cambridge dynasty. The property, including the Chapel, was on the E. side of the Trumpington Road, hard by the present site of Addenbrooke's Hospital. The Sempringham Canons are also said to have taken a prominent part in the life of the University.

Before this second influx of Religious Orders into the town, Hugh of Balsham, Bishop of Ely, had established his community of scholars, soon to become the College of Peterhouse, alongside St. Peter's church, between that building and the premises of the Friars of the Sack. It seems that there was a considerable stirring of life in the affairs of the University about the beginning of the fourth quarter of the 13th century. There are the benefactions of Nigel de Thornton and Roger de Haydon: there are the new regulations of Bishop Hugh of Balsham (1276) giving the University independence of the Archdeacons' Court and regulating the relations of the University and grammar students: and there is finally this establishment of the Bishop's scholars, first with the Canons of St. John's Hospital in 1280 and, four years later, with a suitable endowment, at the new site by St. Peter's. It is perhaps significant that as early as 1270, the year in which Walter de Merton promulgated the second body of statutes of the College he had inaugurated in 1264 and which are cited as an example by Bishop Hugh, he had acquired a fine stonebuilt house (still existing) in Cambridge with considerable adjacent property. The house had formerly belonged to the Dunning family, an important name in early Cambridge history, and was built in the early years of the 13th century. (fn. 61) It remains the property of Merton College, Oxford, to this day. And so a process was set in motion which transformed the structure of the University and the topography of Cambridge.

Mediaeval Cambridge. Diagrammatic Sketch-plans. 1280 1380

In the later 13th century also the Castle assumed its final mediaeval form. It seems that in the middle years of the century the Castle had fallen into a dilapidated state, and it is perhaps significant that neither King Henry III nor the Justices holding their enquiries in 1268 and 1270 were lodged in it. From 1286 to 1289 a reconstruction was undertaken and work was resumed, after an interval, in 1291. Before this time the original motte and bailey Castle of the 11th century had been improved in the late 12th century. Stone is mentioned for building in 1191 and considerable works were undertaken after 1212 in the later years of King John. (fn. 62) The late 13th-century works were on a considerable scale and included walls and towers, a gatehouse which survived to be drawn by Cotman in 1818, and a hall and various chambers. In all some £2,500 were spent. King Edward I lodged for two nights in the new Castle in 1293. The military necessity for such large works is not altogether clear. The Fenland had been in a very disturbed state at the end of the previous reign as a centre of resistance by the 'Disinherited Party', and it may be that it was to guard against a similar use of the Fenland in the future that the King undertook the reconstruction of this Castle. If this was indeed the intention, it was achieved.

c. 1325 to c. 1440

In the second quarter of the 14th century a number of colleges were founded at Cambridge, beginning with Michael House (now absorbed into Trinity College) for which Hervey de Stanton, Chancellor of the Exchequer to Edward II, bought a large house, previously belonging to Roger de Buttetourte, opposite the junction of Milne Street and St. Michael's Lane in 1324. The premises were entered from Foul Lane and the whole property was enlarged and consolidated by the acquisition of further land to the N., including the sites of two hostels, the whole series of transactions being completed by 1353. In addition to the actual site of this College, the founder bought the appropriation of St. Michael's church which he rebuilt between 1323 and 1327 on a very original plan to serve both collegiate and parochial uses. (fn. 63) It compares interestingly with the Chapel built at Merton College, Oxford, some 35 years before.

Further to the southward on the riverside of Milne Street, another College was established by the University itself in 1326, on land which formed part of Nigel de Thornton's gift of about 1270. This foundation was taken over in 1338 by the Lady Elizabeth de Clare who endowed and rebuilt the College to which she gave her name. The site, however, remained that left to the University by Nigel de Thornton, hemmed in between the church of St. John Zachary on the S. and a hostel acquired by John Crauden, Prior of Ely (1321–41), for the use of the monks of that house when attending the University. This hostel was not long to remain on its original site for the monks were bought out by Bishop Bateman of Norwich in 1350, in order to incorporate their premises with property to the northwards, already acquired, as part of his new foundation, Trinity Hall. The monks then moved to another house near St. Michael's church.

At the time of the foundation of Trinity Hall, Bishop Bateman, acting as the executor of the will of Edmund Gonville, moved Gonville Hall to a new site at the corner of Milne Street and St. Michael's Lane from the site purchased by the founder in 1347 on the W. side of Luthborne Lane (now Free School Lane), just E. of St. Botolph's Church. The new site had a considerable length of street frontage on the E. side of Milne Street opposite Trinity Hall, extending from the lane now called Senate House Passage to St. Michael's Lane and returning eastward up that street rather more than half way to the High Street.

North-westwards of this group of four colleges in Milne Street and St. Michael's Lane, King Edward III founded an ambitious establishment on land extending from the High Street to the river, bounded on the southward by a street running from just S. of the present Great Gate of Trinity College to some hythes on the river side of what is now the Master's Garden of that College, and on the N. by the property of St. John's Hospital. The King's new foundation was for a Warden and 32 scholars, by far the largest hitherto established in Cambridge. It was an enlargement of an Institution for the education of the children of the Royal Chapel which dated back at least to Edward II's time when it is mentioned in a writ of 1317. The nucleus of the site of King's Hall was a house of Robert de Croyland, a substantial building situated just W. of the existing Great Gate of Trinity College with a garden extending westwards towards the river and its hythes. This property was bought by the King in 1336 and the site was enlarged by further purchases, in 1339–41 and 1344, to form a large consolidated property which was rounded off by the purchase of the hythes themselves in 1351 and a small corner site on the High Street immediately E. of the Great Gate in 1376.

The documents still in the possession of these 14th-century foundations, or in the case of Michael House and King's Hall of their successor, Trinity College, show that this new University quarter that came into being in the middle years of the century, replaced a quarter of well-to-do houses that had grown up at the N. end of the new part of the town between the High Street and the river in the course of the 12th and 13th centuries. The parcels of land acquired by the colleges, except along the High Street itself, are of considerable size and the houses of Robert de Croyland and Roger de Buttetourte were clearly large buildings for town houses. Moreover, there is evidence that the house in St. Michael's Lane which formed the nucleus of Gonville Hall (and probably still remains in part embedded in later work) was of stone, a luxurious way of building in Cambridge, and remains were found in the 19th century of a round-headed Romanesque window in stone in the part of Trinity Hall purchased from the Ely monks in 1350. Another stone house in this area was that of the Prior of Anglesey Abbey on the High Street itself, forming the S.E. corner of the present site of Gonville and Caius College.

The colleges founded in the area W. and N.W. of St. Michael's church form a distinct group of special significance for the topographical history of the town. Two other foundations of the mid 14th century, Pembroke (1347) and Corpus Christi College (1352), were sited just outside the Trumpington Gate and immediately to the S. of St. Benet's Church respectively. The site of Pembroke College was formed of a fairly large piece of ground at the corner of Trumpington Street and the lane running eastwards alongside the King's Ditch, bought by the Countess of Pembroke in 1346, and a similar sized piece, which had been given to the University by Robert de Haydon before 1279 and on which a hostel had been established, was bought by the Countess in 1351. The site was enlarged by further purchases in the later 14th and 15th centuries but these two pieces of ground accommodated the entire buildings of the mediaeval college. Our knowledge of the formation of the site of Corpus Christi is less complete than that of other early colleges. The ground on which the Old Court was built, just to the S. of St. Benet's Church, is said to have been the gift of various members of the Guild which founded and endowed the College. But we have no details except for the acquisition of the advowson of St. Benet's which, together with a house in Luthborne Lane (now Free School Lane) adjoining the churchyard, was conveyed to the College in 1353. In the same year the new College effected an exchange with Gonville Hall, the original founder of which had acquired a site further along the Lane to the S. The Guild of Corpus Christi gave for this the property it had inherited from Sir John de Cambridge at the corner of Milne Street and St. Michael's Lane, including a stone-built house, the nucleus of the present Gonville and Caius College as described above. Corpus Christi College, from the circumstance of its foundation by a Guild of townsmen and its attachment to one of the oldest of the parish churches, is the only College whose site is in the real heart of the original Cambridge. With the house of the Austin Friars immediately to the E. on the other side of the Lane, it formed a great area of the commercial centre of the town taken out and devoted to pious uses.

From the muniments of these earliest colleges much information can be gathered on two aspects of the mediaeval town, the hostels for members of the University which the colleges in no way superseded at their first foundation, and the position of the little lanes and entries which distinguished the plan of the mediaeval town from much of the present-day Cambridge. These little lanes and entries seem to have been closed and absorbed into the consolidated sites of the colleges with comparative freedom from an early date, as, for instance, the lane which bisected the site of Gonville and Caius from E. to W. This became private as early as 1337, sixteen years before the College acquired the site. Others, such as Swynscroft Lane, which divided the original site of Pembroke College from the pasture to the eastward acquired by the foundress, lasted until 1620 and some have survived until modern times.

c. 1440 to c. 1500

The first half of the 15th century saw no very drastic changes in the topography of Cambridge until the activities of King Henry VI began in the 1440s. Before that time the most important changes were the gradual acquisition by King's Hall of various pieces of land on the S. side of King's Childer Lane, i.e. the Lane leading from High Street to the junction of Foul Lane at which point a new Gatehouse was begun by King's Hall in 1426–7 facing southwards down Foul Lane. The consolidation of this new site was completed by 1433 in which year also the town agreed to closing that part of King's Childer Lane from the High Street to the new Gatehouse, thus incorporating the newly acquired land with the original site of the College. Another important development was the grant by King Henry VI in 1428 of a site in the parish of St. Giles, i.e. on the N.W. side of the river, to the Abbey of Crowland for the accommodation of monks of the Benedictine Order resident at the University. This is the first sign of the extension of University interests to the left bank of the river. The site of the new 'Hostel' seems to have included the back lands, now the Fellows' Garden of Magdalene College, from an early date, as the Abbot is paying rent to the town for them as early as 1432. An interesting detail, though of no great topographical significance, recorded under the year 1423, is an agreement between the town and Michael House whereby the College is allowed to construct a small dock leading from the main river into its Garden for the loading and unloading of barges with fuel and other goods. Small private docks of this kind can still be traced in connection with large late mediaeval farms in some of the Cambridgeshire parishes bordering on the Fens.

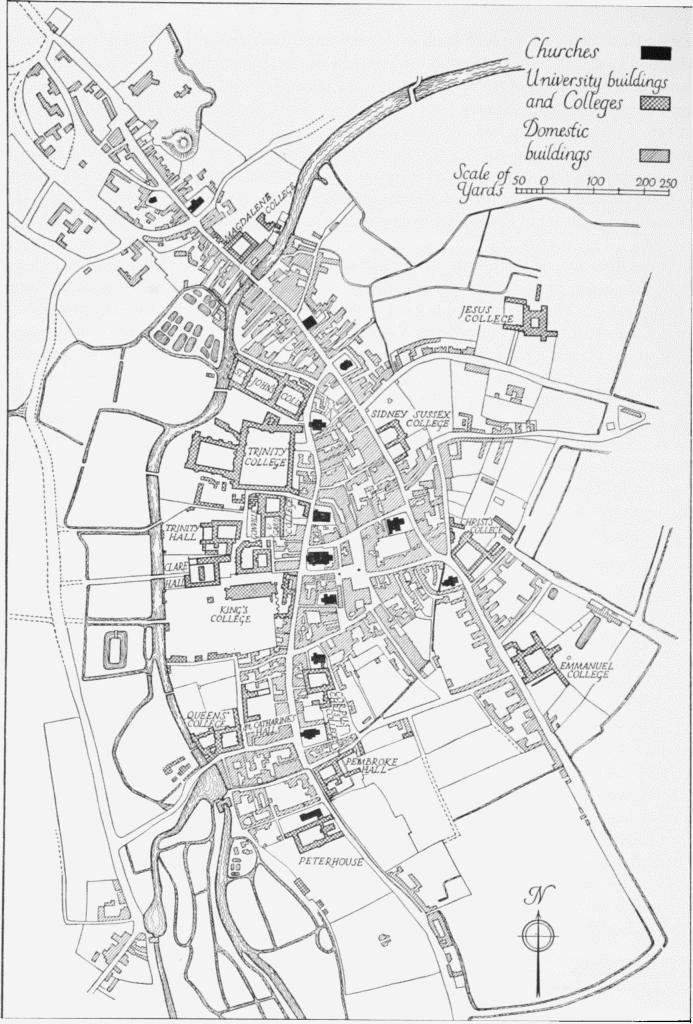

King Henry began to acquire land in Cambridge for his new college foundation in 1440–41. His first intentions were of a comparatively modest kind and the site acquired was a small one, mainly to the W. of the University property on which the Schools buildings were gradually being erected. The site faced on to the E. side of Milne Street and included a considerable piece to the southwards, extending from Milne Street as far E. as Schools Street. Other small properties to the N. of the Schools' site were not acquired till later. By August 1443 the King, having determined on a much more ambitious foundation, began to acquire a larger site. This lay between the High Street and the river and extended from Clare College southward to the House of the Carmelite Friars in the area W. of Milne Street and from the S. boundary of the 1441 site about the same distance southwards in the area between Milne Street and High Street. This area included a great part of Milne Street itself, Piron Lane which connected Milne Street and High Street, and two other lanes leading from Milne Street to the river. It also included the Church and Vicarage of St. John Zachary hard by Clare College, the newly acquired site of God's House, a collegiate institution for grammar teachers lately established at the corner of Milne Street and Piron Lane, and a number of properties described as Hostels. Along the riverside was a considerable amount of common land belonging to the town and the landing-place called Salt Hythe. The first site to be acquired was the corner of Piron Lane and High Street; almost the whole was in hand by 1449, except for a most important piece on which the E. end of the present King's College Chapel was set. This purchase was not completed until 1451 and then only under the most stringent conditions. Other hard bargains were made. Compensation was promised in 1445 to the town for the loss of access to the river at Salt Hythe. This was a new way down to the river to the N. of Trinity Hall. More important than this, a new site was acquired for God's House in 1446, gradually enlarged over the following thirty years to include almost all the site of the present Christ's College to the W. of the Fellows' Building and forming the first College building site outside the town on the great S.E. road, Preachers Street as it was then called after the Dominican Friary just a little further out on the same side of the road. In 1447, the King obtained from the town a large part of the common pasture (Water Meadows) on the left bank of the river extending from the present southern boundary of King's College to what is now the northern boundary of Clare College garden. This was the beginning of the extension of College gardens across the river, which was ultimately to constitute the Backs. The formation of the site of King's College was the most important single event in the topographical history of mediaeval Cambridge. The closing of so many streets, especially Milne Street and Piron Lane, and the extinction of the parish church of St. John, meant the practical obliteration of a large part of that quarter of the town which had developed in the 12th century.

The foundation of King's College was not the only charitable act of the King affecting the Milne Street area. In 1446 he gave a small property at the eastern corner of Milne Street, where it joined Small Bridges Street (now Silver Street), to Andrew Docket, Rector of St. Botolph's, for a new College, some eighteen months later to be taken under the protection of Queen Margaret of Anjou and called the Queen's College of St. Margaret and St. Bernard. By that time, however, a more convenient site immediately opposite on the W. side of Milne Street had been acquired and the existing buildings were begun on the second site in 1448. Yet another foundation was established on the east side of Milne Street, opposite the junction of the new Queens' College site with that of the Carmelite Friars, in 1475. The site had been acquired by Robert Woodlarke, the Provost of King's College, as early as 1459, but the difficulties of the times delayed the fulfilment of his plans. The site was a small one and did not extend through from Milne Street to High Street though the founder clearly hoped to acquire access to the latter. The main gate of the new College, St. Catharine's, remained in Milne Street until the 18th century. In the same year as the foundation of St. Catharine's College, Queens' College obtained from the town all the land on the left bank of the river from the boundary of King's College property to the road to Newnham and extending as far back as a branch of the river running northwards from Newnham Mill.

The first University buildings, the Schools, which were begun about the middle of the 14th century on the site originally given to the University by Nigel de Thornton before 1278, progressed very slowly and the first range was not completed in its present form till about 1400. (fn. 64)

The site was enlarged and further buildings put up in the course of the 15th century, the first purchase of land being from Trinity Hall in 1421 to the W., and the second purchase followed in 1431 of the garden of Crouched Hostel to the S., the major part of which was then resold to the King for his new College in 1440. The whole site was formally consolidated by the purchase of a small plot belonging to Corpus Christi College in 1459.

The 16th Century

The great series of College foundations which begins with Jesus College in 1496 and ends with Sidney Sussex in 1594, though it profoundly changed the architectural character of the town, changed its topography less than the 14th and 15th-century foundations. This was because the new colleges occupied sites which were already given over to religious or collegiate uses and did not entail the purchase of houses and shops in a process of formation and consolidation of sites on a scale comparable with the earlier schemes. Jesus College was accommodated on the land and in the premises of the Nunnery of St. Radegund, property which had been religious since the 12th century; Christ's College (1505) was a re-foundation in ampler form and on ampler principles of God's House whose site had been acquired in 1446; St. John's College (1511) took over the site of the Hospital of St. John, again an early foundation, and even the land on the left bank of the river had in part been acquired by the Hospital in the mid 15th century; Magdalene College (1542) was a re-foundation of the Benedictine Hostel, latterly called Buckingham College, on a site which dated back to before 1430; Trinity College (1546) took over the sites of Michael House and King's Hall, and the two latest foundations, Emmanuel College (1584) and Sidney Sussex College (1594), were settled on the sites of the Dominican Friars and the Franciscans respectively. Of the sites of the other religious houses within the town, that of the Carmelites was divided between its neighbours, Queens' College to the S., and King's College to the N., the N. wall of the church being left standing till this day as a boundary between them. Only the Austin Friars' on the E. side of Free School Lane passed into private as against institutional possession.

One quality shared by all these foundations seems to have been an increased awareness of the undergraduate element in the Colleges. This is very markedly so at Christ's College and St. John's College, the two Lady Margaret foundations, and with this begins a process of the absorption of the Hostels, the system of student accommodation that antedated the College system, into the body of the Colleges. Dr. Caius writing in the early 1570s compares the Cambridge of his first period of residence 1529–39 with that he found 20 years later: of the eighteen Hostels he remembered in the 1530s the 'most part are deserted and given back to the townsmen' except for a few that had already been merged in Colleges. This change meant a great increase in the number of undergraduates in Colleges who paid for their accommodation, pensioners, as against those on the foundation, and with the increase in numbers in the University in the last quarter of the 16th century we begin to hear of Pensionaries, i.e. sets of rooms for this kind of undergraduate, as at Corpus Christi in 1569 where the old tennis court was fitted up for this purpose; at St. John's in 1584, where a storehouse forming part of the old original hospital was similarly fitted up, and again in 1589 when some houses opposite the main gate were adapted for the purpose; also at Gonville and Caius in 1594 and at Christ's in 1613 Pensionaries were adapted or built. All these, except perhaps the last, were hardly of such substantial character as to be worthy of being called new College buildings but were rather improvised accommodation to meet the emergency overcrowding of the time. They heralded, and were in part superseded by, the series of buildings of a more durable and ambitious character, mainly sets of rooms, that began with the last years of the 16th century and continued throughout the one that followed. Overcrowding was not confined to the Colleges in the late 16th and early 17th centuries. There are a number of complaints about this difficulty, the most illuminating, a letter of the Privy Council in 1584 when the subdivision of old houses, the use of converted stables and the building of new cottages are mentioned. (fn. 65) This all sounds rather like the formation of slums, for the largest number cited seems to be in the poorest parishes such as St. Giles' and St. Peter's at Castle End. This overcrowding does not seem to have gone far to filling up the back lands behind the street frontages by the end of the century, to judge from Hamond's map of 1592, but there is evidence of considerable building in what is now Green Street (fn. 66) in a document of 1632, most of the development being recent. (fn. 67) Out of 26 houses 13 are new cottages and there are 3 empty tenements 'all new built'; there were 151 persons making 32 families in the street. In the mid 15th century the town had, like many others, suffered a decline and the petition for a reduction of an assessment in 1446 is concerned, not only with the loss of the great area taken for the site of King's College, but mentions the houses taken over for the use of scholars, formerly accommodating craftsmen, and also houses standing empty. Though there is evidence of recovery in the new century, by 1541 Cambridge is included in an act of Parliament to encourage the repair of decayed houses, chiefly of the larger kind.

Apart from these general considerations the most important topographical changes of the 16th century seem to be the closing of Foul Lane, that prolongation of the line of Milne Street as far as the gate of King's Hall (1426–7). This was effected in 1551 as the immediate result of the amalgamation of Michael House and King's Hall to form King Henry VIII's Foundation, Trinity College. The other topographical incident of special interest is the first attempt at formal town planning in Cambridge, that is, the making, at the expense of Archbishop Parker in 1574, of a new street leading straight from the W. door of Great St. Mary's church, then not long completed, to the front of the Schools. The new street was 157 ft. long and 24 ft. broad at the High Street end (the High Street itself was only 25 ft. broad at that point) and 28ft. broad at the Schools Lane end. The relevance of these dimensions is that before Archbishop Parker's improvement the only approach to the Schools was directly by way of East Schools Street, a narrow way about 12 ft. wide. The purpose of the new street was not only for convenience of access to the Schools but as the Archbishop's biographer puts it, 'that so a more handsome sight might be of the public Schools, obstructed before by the town houses.' (fn. 68)

The 17th and 18th Centuries

The most important topographical changes in the 17th century took place in the first fifty years. In 1613 Trinity College obtained by exchange with the town the land on both sides of the river at the back of the College. These pieces, together with the parts acquired by St. John's College in 1610, completed what are now known as the Backs. An equally important change in the same part of the town was the arrangement between Clare College and King's College, whereby Clare acquired the northern part of the water meadows on the W. side of the river opposite the College, which they were rebuilding in its present form. These are now Clare Walks and Fellows' Garden. The land given by Trinity College in the exchange with the town was a part of the common fields now known as Parker's Piece, the most important public open space in Cambridge and second only in size to the great series of commons that stretch from Jesus College to Stourbridge Common and beyond.

The other important changes in the 17th century were architectural rather than topographical. Some of the late mediaeval Colleges—Queens', Christ's and St. John's—had set an example of more or less formal street fronts with towered gatehouses, but of the late 16th-century foundations only Sidney Sussex made any attempt to have an entrance front to a main street. Emmanuel College preferred to have its main entrance off a side lane. Magdalene, it is true, in a modest way contrived a range including a gateway on the street side of the court, but Trinity left its splendours largely hidden from the main street by a block of houses and shops, as it still does, and King's College, still a great unfinished fragment, was largely masked from Trumpington Street by buildings of various kinds.

Cambridge in 1688 After David Loggan

Two Colleges, however, showed some regard for their street frontages in the 17th century: Peterhouse and Pembroke. Peterhouse, with its chapel linked by arcades to flanking ranges, was the more ambitious of the two. Pembroke's front, an extension to the southwards of the original western range, was finished by the pilastered façade of the chapel crowned with its urns and lantern cupola. (fn. 69) It is interesting to note, however, that the ambitious new scheme for the rebuilding of St. Catharine's College, shown in Loggan's print and map, though it provided for access to Trumpington Street by a narrow alleyway, was content to have its eastern façade cut off by houses from the main street of the town and only visible from a narrow lane continued along its eastern boundary. The main reason for this lack of enterprise in street façades was no doubt economic; the blocks of houses to the E. of the Great Court at Trinity, the enlarged site of King's or between St. Catharine's and Corpus Christi and Trumpington Street were valuable revenueproducing properties. Nevertheless the taste for display was certainly present in the minds of the dons of 17th-century Cambridge, as not only the Peterhouse and Pembroke fronts bear witness, but also the river fronts of Clare, Trinity and St. John's; the 17th century saw only the beginnings of the effects of such a taste, which continued through the 18th century and culminated in the first years of the 19th century.

Three admirable engraved maps of the town, Hamond's map of 1592, Loggan's of 1688 and Custance's of 1798, show the progress in the 17th and 18th centuries. The filling up process and crowding within the borough boundaries already referred to, which we know to have begun before Hamond's map was drawn, is very marked and almost complete by the time of Loggan, but there is surprisingly little change by 1798. No doubt there was much rebuilding, refronting and heightening of houses but there is comparatively little new development in the 18th century. The great system of common fields hemmed in the town and expansion had to wait for the enclosures of the early 19th century.

The improvements of the 18th century were again largely architectural. In 1747 a new Sessions House was built on the site of the Shambles immediately in front of the Town Hall to the S. of the Conduit in the Market. This was a building raised on an open colonnaded ground floor thus preserving in some degree the vested interests of the stall holders who had used the site. The upper floor containing courts was connected by a bridge to the old Town Hall. The Town Hall itself was remodelled by the architect James Essex in 1782. Until 1849–50 the Market Place at Cambridge consisted of a series of small open spaces devoted to various trades. The chief or Garden Market contained both the Cross and the Conduit to the N. of the Town Hall. The Corn and Poultry Market was in a comparatively wide extension of this leading out of the N.E. corner, and the Fish Market was (and still is in part) in Peas Hill, i.e. the wider part of the street running out to the S.W. The Butchers were in the streets to the E. and S. of the block containing the Sessions House and Town Hall. The main area of the existing Market was formed in 1849 as a result of a fire that destroyed a small block of houses immediately to the E. of the University church and a larger block separated from them by a narrow street and occupying a large part of the existing Market space. Other architectural improvements to the look of the town were the new front, to St. Andrew's Street, built for Emmanuel College by James Essex in 1770, and the opening up of St. Catharine's to Trumpington Street achieved at last also by Essex.

The focus of architectural enthusiasm and zeal for improvement in 18th-century Cambridge was the area immediately E. of the Old Schools and Henry VI's enlarged site of King's College. The problems of these two sites were clearly closely interconnected. Schemes for both sites seem to have dated back to the beginning of the 17th century and after the Restoration there are signs that the University project, which included a Senate House and additions to the Library, took on a new lease of life animated by Bishop Cosin of Durham among others. A beginning was made by the acquisition of property lying between Archbishop Parker's University Street of 1574 and Caius College, and a drawing of a new Senate House survives which seems to date from this period. In the later years of the century there are renewed signs of the interest in a project to complete King's College. On the election of Provost Adam in 1712 there was considerable activity in procuring benefactors, and the Provost himself approached Nicholas Hawksmoor and Sir Christopher Wren in the first months of his office. As a result Hawksmoor produced an ambitious design for exploiting the great site to the S. and W. of the Chapel, including in it a grand façade towards Trumpington Street. A number of drawings of this scheme and two models survive in the College, and in the British Museum is a rough drawing showing a complete scheme for remodelling the whole town (fn. 70). This was even more ambitious in the baroque manner than the partly realised scheme by the same architect at Oxford.