An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in Dorset, Volume 5, East. Originally published by Her Majesty's Stationery Office, London, 1975.

This free content was digitised by double rekeying. All rights reserved.

'Sectional Preface', in An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in Dorset, Volume 5, East(London, 1975), British History Online https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/rchme/dorset/vol5/xxii-xlviii [accessed 30 January 2025].

'Sectional Preface', in An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in Dorset, Volume 5, East(London, 1975), British History Online, accessed January 30, 2025, https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/rchme/dorset/vol5/xxii-xlviii.

"Sectional Preface". An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in Dorset, Volume 5, East. (London, 1975), British History Online. Web. 30 January 2025. https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/rchme/dorset/vol5/xxii-xlviii.

In this section

DORSET V

Sectional Preface

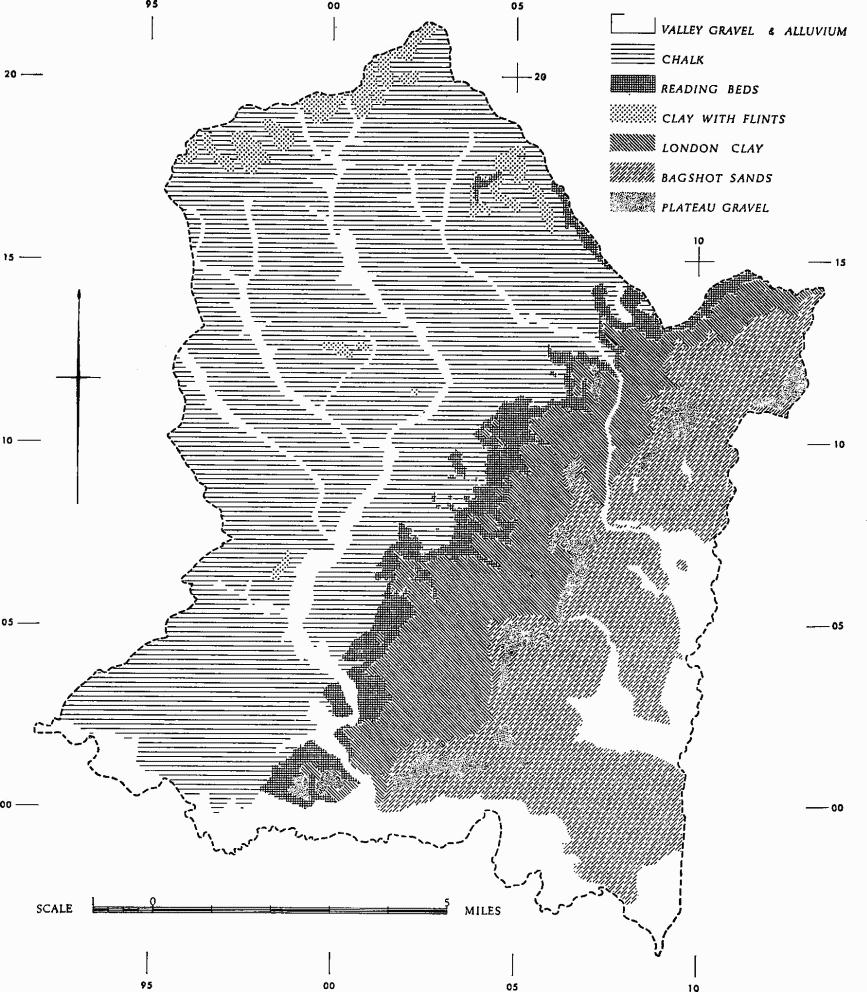

Geological Map of East Dorset

In the preface, numbers in square brackets refer to Plates: those in round brackets denote the Monuments in the Inventory.

Topography and Geology

This Final Volume of the Dorset Inventory describes the Ancient and Historical Monuments of twenty-five parishes on and near the eastern boundaries of the County, comprising a roughly rectangular area of 120 square miles bounded on the N. by Wiltshire, on the E. by Hampshire and on the S. by the R. Stour and the expanding city of Bournemouth.

The underlying geological formation (map opposite) gives rise to two distinct landscapes. The N. and W. of the area is part of the Chalk lands of Cranborne Chase. The Chalk slopes gradually down in a south-easterly direction from the Wiltshire boundary, where it reaches over 450 ft. above O.D. and is capped by Clay-with-flints, to altitudes between 150 ft. and 250 ft. where it is overlain by the Eocene deposits of the Hampshire basin. Four roughly parallel streams drain this dip-slope: the Crichel and Gussage Brooks and the headwaters of the rivers Allen and Crane; they give rise to a rolling landscape of shallow, open valleys with relatively low, rounded interfluves. With the exception of the Crane, the streams are tributaries of the Allen, which flows S. to meet the Stour at Wimborne Minster. Numerous dry re-entrant valleys lead off the main valleys.

The surface in the E. and S.E. parts of the area is composed of Eocene rocks which outcrop south-eastwards in a series of widening bands. A narrow strip of sands and gravels of the Reading Beds is succeeded by a somewhat wider band of London Clay, both outcrops being well-wooded; beyond this an extensive area of sands and gravels of the Bagshot and Bracklesham Beds gives rise to rolling heathland, much of it now planted with conifers. This land is mostly between 50 ft. and 200 ft. above O.D., but it rises to over 300 ft. on Cranborne Common; it is drained generally south-eastwards by numerous small tributaries of the Crane.

Building Materials

Indigenous building materials in the Chalk lands of the N.W. are flint, greensand and cob for walls; timber and thatch for roofs. In all mediaeval churches the walls are of flint with greensand dressings, or wholly of greensand, while the original roofs were presumably thatched or lead-covered, although most of them have subsequently been tiled. Heathstone at Cranborne parish church and manor house and in the tower of Witchampton church is explained by the proximity of the Eocene region. In the church of Gussage St. Michael some heathstone blocks were imported for the decoration of the tower arch. At Cranborne manor house the early walls are of flint with stone dressings, and in other manor houses with walls surviving from before the 16th century similar materials are generally found. Early cottages in the Chalk region generally have cob walls on flint plinths, but in parts of the area adjacent to the Eocene deposits, where oak was abundant, timber framework is found.

In the Eocene region mediaeval churches have walls of heathstone rubble with dressings of worked heathstone and of imported Purbeck stone; the 11th-century walls of Wimborne Minster church provide a good example. At Colehill the 15th-century manor house (1) has some surviving heathstone walls; in the monastic buildings at Horton (6) the original walls were of timber framework. Early cottages to survive in the S.E. region are usually of timber framework. Cob cottages at Verwood and at Hampreston are of 18th and early 19th-century date.

Brick makes its earliest appearance in East Dorset in the 16th-century manor house of Witchampton (3); the fanciful design indicates that the material was a novelty, and it is suggested that this may be the earliest brickwork in the county. By the beginning of the 17th century brick was commonly employed in superior secular buildings, but until the 19th century it was generally thought inappropriate for churches; at Horton, c. 1720, the walls of the church which were seen from the manor house garden were refaced in brick, but the entrance façade and the church tower were rebuilt in stone. By the second half of the 18th century brick was cheap enough for use in cottages; it also was used as a substitute for the wattle-and-daub which previously had filled the panels of timber-framed buildings.

Roman and Prehistoric Monuments

Settlements and Enclosures

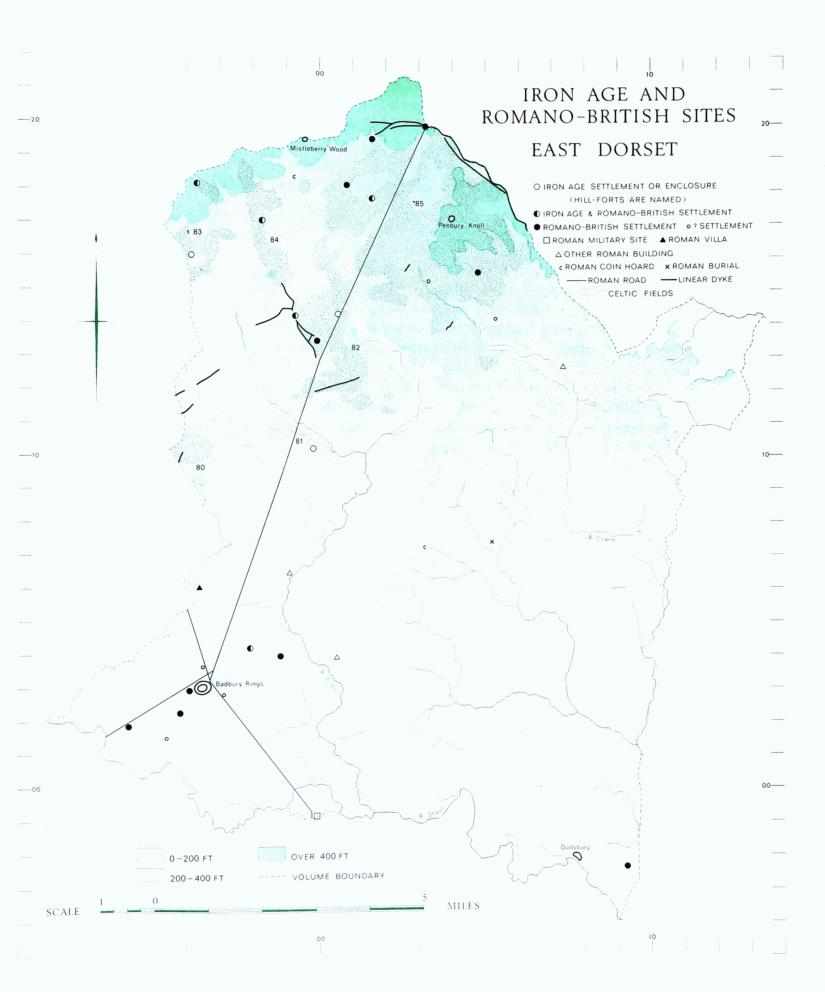

In East Dorset there is a variety of settlements and enclosures, of which the majority are dated and belong to the later prehistoric and Roman periods; they represent many of the types of sites of that date so far discovered in Wessex. The earliest is the late Bronze Age site on Handley Down, known as 'Angle Ditch' (Sixpenny Handley (27)), which though not certainly a complete enclosure invites comparison in plan with the contemporary settlement, also excavated by General Pitt-Rivers, less than 3 miles away on Martin Down in Hampshire. Iron Age sites may be divided between hill-forts and settlements, and the latter may be divided between those which were occupied, as far as is known, only before the Roman Conquest and those which continued to flourish often long after it. The largest hill-fort, Badbury Rings (Shapwick (34)), is a complex multivallate work with massive defences enclosing 17 acres [62]. It occupies a prominent Chalk knoll overlooking the Stour valley, on the S. edge of Cranborne Chase. Further E., on the Eocene Sands, is Dudsbury, an 8-acre fort with strong double defences, now sadly mutilated. It lies on a river cliff above the R. Stour, which would have been navigable at this point and which probably played an important part in its economy. There are no large hill-forts in the heart of Cranborne Chase, and in the part of the Chase covered by this volume there are only two small forts: on Penbury Knoll (Pentridge (18)) a univallate enclosure occupies 4 acres of a prominent hill-top, but the defences are weak and possibly unfinished, though much damaged by quarrying. In Mistleberry Wood an unfinished univallate work of about 2 acres is in a poor defensive position (Sixpenny Handley (25)).

The enclosed Iron Age settlement at Gussage All Saints (20) has recently been excavated [54]. The site was found to have been occupied throughout much of the Iron Age, but it was enclosed only in the last few decades before the Roman conquest and was totally abandoned by c. A.D. 80. Finds of grain and agricultural implements and the existence of 'Celtic' fields near by indicate arable farming, but the funnelled approach and the presence of quantities of animal bones, especially of cattle, suggest the importance of live-stock. The enclosure Gussage St. Michael (8) is cut by the Roman road, and its size (8 acres) and form suggest that it is of the Iron Age rather than earlier. A similar date would appear most likely for the construction, if not for the total period of use, of the 12-acre enclosure at Sixpenny Handley (24). Both sites are integrated with 'Celtic' fields, and the latter site is probably integrated with tracks and ditches.

At four sites there is evidence of occupation in both the Iron Age and the Roman periods. That at Woodcutts (Sixpenny Handley (19)), the only one which has been extensively excavated, was progressively enlarged and continuously occupied until well into the 4th century; a similar sequence is probably true of the settlements on Gussage Hill (Gussage St. Michael (7)), on Oakley Down (Wimborne St. Giles (36)) and King Down (Pamphill (70)). The composite layout of these sites also suggests lengthy occupation and presumably reflects what is likely to have been the time of their greatest prosperity, the Roman period, rather than earlier. Without excavation the Iron Age components in their structures are difficult to isolate with certainty and, morphologically therefore, such sites are more readily comparable with native sites of the Roman period. Finds indicate the existence of a number of the latter, some of which survive as earth-works, but only that at Woodyates (Pentridge (15)) has been substantially examined by excavation and it is likely that some of the remaining sites will prove on fuller examination to have been begun in the Iron Age. For example the enclosure and storage-pits associated with the settlement at Humby's Stock Coppice (Sixpenny Handley (20)) suggest a pre-Roman origin.

Native settlements, whether they began in the Iron Age or after the Roman conquest, vary considerably in size and form; from a single farmstead at Woodcutts with a relatively simple sequence of development to substantial villages covering many acres, as at Gussage Hill or Jack's Hedge Corner (Cranborne (34)). The settlements on Oakley Down, S.W. of Oakley Farm (Sixpenny Handley (21)) and beside Badbury Rings (Shapwick (31)) lie within, or largely within, single irregular enclosures; those at Gussage Hill, at Woodyates, and apparently at King Down (Pamphill (70)), incorporate a number of enclosures of varying size. At Gussage Hill are two small enclosures of a type found in other chalkland settlements in South Wiltshire and, more particularly, in Hampshire and usually considered to be associated with some aspect of stockkeeping. Sometimes known as 'banjo enclosures' they are generally, as at Gussage Hill, less than an acre in area and round in plan, with a narrow funnelled approach linked to other larger enclosures or linear boundary dykes. A comparable enclosure at Humby's Stock Coppice [62], also linked to boundary ditches, is unusual in that it encircles a large number of storage-pits, though as some lie outside it the two features are not certainly contemporary. There is little evidence of tracks associated with settlements, except at Woodcutts and Oakley Down, where they lead into and through the main occupation areas and at the latter site appear to link it with the Roman road. Several of the downland settlements are associated with 'Celtic' fields (see p. 117).

At a few sites masonry remains of substantial buildings indicate more pronounced Roman influence, but none of these has been examined fully, or using modern techniques, and records are generally inadequate. Best recorded is the villa near East Hemsworth (Witchampton (22)), where a complex of structures and numerous mosaics [89] indicate an establishment of importance. What appears to be a villa was found at Holwell (Cranborne (33)). Roman buildings found in Witchampton (23) are possibly those of a temple. Remains of another building have been discovered at Stanbridge (Hinton Parva (3)).

The settlement sites at present known are unlikely to be a representative sample of those which once existed, in particular as far as their distribution and siting is concerned. In areas of intensive post-Roman activity, especially cultivation, many settlements will have been masked or destroyed, notably on the lower ground in the vicinity of the present villages, most of which have been in existence for well over a thousand years. Away from the villages, especially in areas of former downland pasture where the destructive processes are less advanced, early settlements are more readily detectable, though even here intensive arable farming is now taking its toll. The Iron Age sites lie either on hill-tops or on upper slopes, in part a response to the need for defence or at least for a good look-out in that generally unsettled period. Many Romano-British settlements occupy upland positions too, but it is noticeable that the Roman buildings at Holwell, Stanbridge and Witchampton, and contemporary occupation sites at Shapwick (33) and West Parley (6), all lie in or near the bottoms of valleys.

Roman roads played an important part in the appearance or continued development of settlements. Certainly settlements on or close to roads appear to have flourished, as at Oakley Down and at Gussage Hill. At the latter site, for example, a second occupation nucleus grew up, apparently in the later Roman period, nearer the road. The Iron Age settlement at Gussage All Saints (20) did not survive into the Roman period despite its proximity to a road. At Woodyates, where the Roman road from Old Sarum to Badbury Rings passes through the late Roman defensive earthwork, Bokerley Dyke, the settlement occupies a special position probably at the boundary between two administrative units. The focus of Roman roads at Badbury Rings, as at Old Sarum, led to the early appearance of an extra-mural settlement (Shapwick (31)), probably the Vindocladia of the Antonine Itinerary, and is doubtless partly responsible for the concentration of settlements, not all dated, in the vicinity of the hill-fort, notably in the parishes of Pamphill and Shapwick. Presumably contemporary with the establishment of the road from Poole Harbour to Badbury Rings is the Roman military site at Lake Gates (Pamphill (69)). Its precise nature and extent are not yet known, but selective excavation suggests that it probably was a supply-base, beginning c. A.D. 45, beside an important crossing point of the broad, marshy valley of the R. Stour.

Linear Dykes

Linear dykes, constituting some form of boundary, are not common in Dorset; mostly they are found N. and E. of the R. Stour, in Cranborne Chase, where they comprise the S.W. limit of a pattern of distribution which extends over the Chalk lands of Wiltshire and Hampshire. Significantly, two of the most important dykes in the area lie near the boundary between Dorset and these counties. Grim's Ditch (Pentridge (17)) is part of an extensive complex of boundary ditches which extends for 9 miles, mostly in Hampshire, and is itself part of a former system of land division and allotment. Almost certainly it evolved over a lengthy period, from the later Bronze Age to Roman times. Its neighbour, Bokerley Dyke (Pentridge (16)), most of which lies on the boundary between Dorset and Hampshire, is altogether different in character [56]. It is a late Roman work and its course and dimensions indicate that it was a defensive barrier or frontier, facing N.E., probably to defend a stretch of open downland between two wooded areas. It possibly replaces the older non-defensive line represented by the Dorset section of Grim's Ditch.

Boundary dykes extending westwards into Tarrant Hinton and Tarrant Launceston (Dorset IV, 96, 105) are found on former downland in Long Crichel (7). One with multiple low banks and intervening ditches comes to an end on the W. side of the valley-bottom of the Crichel Brook, and reappears on the far slope where it goes on to meet the Cursus earthwork. Similar multiple boundary banks occur in association with the Iron Age and Romano-British settlement on Gussage Hill (Gussage St. Michael (7)); others are associated with settlements of comparable date in South Wiltshire, such as Hanging Langford Camp (Steeple Langford), Hamshill Ditches (Barford St. Martin), and Grovely Earthworks (Great Wishford). 'Celtic' fields are integrated with the dykes on Gussage Hill, and with shorter lengths of dyke such as Gussage All Saints (21), also with those on Bottlebush Down and near Nine Yews in 'Celtic' Field Group (85).

Nearly all the dykes have been flattened or severely damaged by ploughing, leaving the ditch or ditches visible only as crop or soil marks. An exception is the massive earthwork of Bokerley Dyke, but this too has largely been flattened in the area N.W. of the Roman road.

Barrows and Burials

Iron Age and Romano-British Sites East Dorset

Eleven Neolithic Long Barrows and two probable examples are recorded in the area; they are all on the Chalk and all but two lie in the parishes of Gussage St. Michael and Pentridge. All are sited prominently, most of them on the summits of ridges or spurs, as on Thickthorn Down, Gussage Hill and Bokerley Down. Nearly all are aligned S.E.–N.W., but Pentridge (19) and Wimborne St. Giles (38) lie N.E.–S.W. Some of these barrows (mostly in Gussage St. Michael) are well preserved, but ploughing has damaged three (Pentridge (20–22)) and has severely mutilated Gussage St. Michael (13), Wimborne St. Giles (38) and the two probable long barrows, Gussage St. Michael (10) and Pentridge (23). The mound of Wor Barrow (Sixpenny Handley (29)) was removed by excavation.

Nearly all the mounds are between 100 ft. and 200 ft. long and none exceeds 300 ft. Except where reduced and spread by ploughing, all are between 50 ft. and 75 ft. wide and between 5 ft. and 10 ft. high. A few mounds (Gussage St. Michael (14), Pentridge (19) and (20)) are both lower and narrower at their northerly ends. The ditches associated with the mounds, where visible at all, vary in plan. The pattern common to most long barrows, of twin, roughly parallel ditches flanking the sides of the mounds, is found; two mounds set end-to-end (Pentridge (21) and (22)) appear to be flanked by continuous side ditches. Three of the shorter mounds, all in Gussage St. Michael and associated with the Dorset Cursus, have ditches U-shaped in plan; in long barrows (11) and (12) on Thickthorn Down the U opens away from the Cursus; in long barrow (15) on Gussage Hill it opens towards it. At Wor Barrow the ditch encircled the mound except for a few narrow causeways.

Only two of the long barrows have been excavated. At Wor Barrow, General Pitt-Rivers found Neolithic burials within a mortuary feature under the mound and also in the ditch. Of six burials under the mound, three were articulated and three were in disorder; the state of the latter suggested that they had been kept some time before interment. Numerous intrusive burials, probably Romano-British, were found in the mound and in the ditch. At Thickthorn Down (Gussage St. Michael (12)) no burials were found under the mound, but a range of Neolithic pottery was excavated from the ditch. Three secondary burials, two accompanied by bell beakers, were found in pits dug into the mound.

There are at least three hundred and fifty-six Round Barrows in the area, but barely a quarter of them are well preserved; ploughing and other agencies have flattened or destroyed nearly half the number and have damaged the remainder. Seventy-one of the barrows, hitherto unrecorded, have been identified from air photographs taken in recent years; they appear as ring-ditches, the mounds having been destroyed. There can be little doubt that future aerial reconnaissance will reveal many more.

Over three hundred of the barrows lie on the Chalk, but they are by no means evenly distributed. The majority occur in three major concentrations: just E. of Wor Barrow on Oakley Down (Wimborne St. Giles (94–124)); on either side of the Dorset Cursus on and S. of Wyke Down (Gussage All Saints (23–57)); and around Knowlton Circles (Woodlands (29–65)). Nearly fifty barrows lie on the Tertiary sands and gravels of the heathland in the E. and S.E. of the area, over half of them being scattered along the low ridge between Colehill and West Parley in the extreme S.E. No barrows have been found on the Reading Beds and London Clay which together give rise to a belt of heavier soils between the Chalk and the heathland. As elsewhere in Wessex, some of the round barrows have been deliberately built close to long barrows, suggesting a continuous tradition of burial in the area.

The majority of barrows whose form may be determined with some certainty are bowl barrows. They vary considerably in size, but ploughing has distorted the dimensions of many mounds. Of other forms, eleven bell barrows, eight disc barrows and one saucer barrow have been identified.

Records show that at least eighty of the barrows have been excavated or dug into, nearly half of them by Sir Richard Colt Hoare and William Cunnington, working in the early years of the 19th century in the Oakley Down group. Towards the end of the century General Pitt-Rivers opened numerous barrows in Sixpenny Handley, and in 1938 a group in Long Crichel was examined by S. and C. M. Piggott. Structurally most of the barrows are unremarkable, but Sixpenny Handley (37) and (40) had each a penannular ditch, the former very irregular in construction; the earliest feature under Long Crichel (14) was a small penannular palisade trench. Double concentric ditches indicating two main structural phases were found at Long Crichel (18), (19) and (20), and air photographs show similar barrows, now levelled by ploughing, at Shapwick (62) and Woodlands (26), (39) and (48). Great Barrow (Woodlands (46)) is exceptional for the size of its mound and for the diameter of its outer ditch.

Round Barrows demonstrably early in date are Long Crichel (19) and Pentridge (33) or (34) which produced beakers in a primary context, and Wimborne St. Giles (110) in which beaker burials succeeded a crouched interment. Also likely to be early are the primary crouched interments from Long Crichel (18) and (20), Sixpenny Handley (39), West Parley (9) and Wimborne St. Giles (98), (118) and (121). In Wimborne St. Giles the cremations from two unusually long mounds, (99) and (109), and from round barrow (115) are again likely to be early. In addition to barrow burials, two beaker graves, apparently unmarked by surface indications, were recorded by Pitt-Rivers: one (Sixpenny Handley (28)) was found when stripping an area W. of Wor Barrow; the other was found by chance on Blackbush Down in Cranborne. Collared urns of early type were found with primary cremations in Sixpenny Handley (31) and (35); similar urns were found in Badbury Barrow (Shapwick (40) or (41)) apparently in association with food-vessels. The Wessex Culture is represented by burials in Edmondsham (16) and Wimborne St. Giles (97).

From several of the remaining round barrows came primary cremations associated with urns of the middle or later Bronze Age, and such were also found as secondary burials. The majority, however, occurred in flat cemeteries or urnfields in association with barrows, such as Hampreston (36–8) and (40), and Sixpenny Handley (37), or in their near vicinity as elsewhere in Hampreston. Those cemeteries which have been adequately excavated and recorded have been found to hold between forty and one hundred burials.

Numerous skeletons casually buried in disused storage-pits within the settlement at Gussage All Saints (20) were of the late Iron Age. Probably of the late Iron Age too, is the primary cremation found under a round barrow at Sixpenny Handley (30). The cremation burial found under a low mound or barrow at Knob's Crook (Woodlands (18)) is clearly Roman and may be dated c. A.D. 80. Native Romano-British burials, most of them inhumations, occur mainly within occupation sites and usually as a haphazard scatter, as at Woodcutts (Sixpenny Handley (19)) and Woodyates (Pentridge (15)). At the latter site, however, several burials lay in a small square enclosure, and at Oakley Down (Wimborne St. Giles (36)) four of the five burials discovered were cremations. Romano-British inhumation burials, intrusive in earlier barrows, have been found in Sixpenny Handley (29), (31) and (40). Pagan Saxon burials have been recorded in a similar context at Long Crichel (20), Wimborne St. Giles (120)—and probably (88)—and in at least two barrows in Pentridge, no longer identifiable with certainty, but near the Hampshire boundary. The tendency for pagan Saxon burials to occur on or near parish boundaries—themselves a reflection of earlier estate boundaries—has been noted elsewhere in Wessex.

Ceremonial Monuments

North-east Dorset contains some of the most remarkable ceremonial or ritual monuments of the Neolithic period in Britain. The Dorset Cursus (Gussage St. Michael (9)), which extends for over six miles across Cranborne Chase, is the largest monument of its kind so far discovered. Nearly all the long barrows and many of the round barrows in the area are clearly associated with it.

Barrows and Ceremonial Monuments East Dorset

Knowlton Circles (Woodlands (19–22)) are, as a group of earthworks, unique in Dorset, though now sadly mutilated [80]. The opinion that they represent a major ritual or ceremonial centre is reinforced by the occurrence, in their immediate vicinity, of numerous round barrows, including the largest in the county.

'Celtic' Fields

See pp. 117–9, map opp. p. xxvi and plan in end-pocket.

Roman Roads

The network of communications supplemented or replaced by Roman roads is largely unknown, and any attempt to reconstruct it in detail must be highly speculative. Arguments can be drawn from the distribution of pre-Roman sites and finds, especially such features as cross-ridge dykes, some of which appear to have been sited to control movement along ridgeways, and from the existence of routes, supposed to be ancient, occasionally mentioned in land charters of the later Saxon period. Lengths of track are frequently found in association with native settlements and 'Celtic' fields, but they are often incomplete. Doubtless, numbers of local tracks joined Roman roads or other through-routes. By no means all of them are certainly pre-Roman in origin (Dorset II, 622–33; III, 318–46). It has been plausibly claimed that certain major routes, mainly ridgeways, were used in prehistoric times. One such is the ridgeway which follows the crest of the Chalk escarpment, curving S. and W. from near Ashmore, through Dorset to Beaminster and beyond; another is the South Dorset ridgeway which extends from near Swanage to S.W. of Dorchester. Other routes have been suggested, such as that along the ridge between the rivers Piddle and Frome or that between the Iwerne and the Tarrant; for the discussion of these, see Arch. J., CXIV (1973), 257–91; XCIV (1938), 174–222; also L. V. Grinsell, The Archaeology of Wessex (1958), 295–301, and R. Good, The Old Roads of Dorset, 2nd ed. (1966), 10–24.

The Romans introduced an entirely new element into the existing network of communications; that of direct, planned and engineered roads with metalled surfaces, which quickly became the main arteries of the system. They were designed to meet the needs—at first military, but increasingly administrative and economic—for fast and efficient communications in a province where peace and a central administration replaced the internecine strife and political divisions of the British.

The main Roman road in Dorset comes from London and Silchester, and runs S.W. from Old Sarum via Badbury Rings to Dorchester, and thence W. to Exeter. At Badbury Rings it is crossed by a road leading N.W. from Hamworthy, on Poole Harbour, to Donhead in Wiltshire and probably on to Frome and Bath. From Dorchester there were links with Radipole, an inlet of Weymouth Bay to the S., and with Ilchester to the N.W.; a branch road bypassed the town on the north. Roads from Dorchester to Radipole (Road I) and from Badbury Rings to Hamworthy (Road II), together with the immediate portions of other roads converging on Dorchester, are discussed in Dorset II (pp. 528–31; 539–42). Roads III–VII are described below. Published accounts of the visible remains and courses of the roads are as follows: Hutchins's History of Dorset, 1st ed. (1773), I, xiii–xvii; 3rd ed. (1861), I, v–viii; C. Warne, Ancient Dorset (1872), 162– 208; T. Codrington, Roman Roads in Britain, 2nd ed. (1918), 250–7; I. D. Margary, Roman Roads in Britain (1967), 104–16; R. Good, op. cit., 24–9.

Roman Roads in Dorset

The influence of geology and physical topography on the alignment of the Roman roads within the county is marked. The roads which converge on Badbury Rings from the N. and W., crossing the gently undulating dip-slope of the Chalk, proceed in a series of long, straight alignments; very few minor deviations were necessary to negotiate awkward slopes. By contrast, in the very broken terrain beyond the Chalk in West Dorset, the Dorchester-Exeter road was forced to take a much more irregular line to avoid unacceptable gradients. Concerning the structure of the roads there is only limited information; continuous post-Roman usage has often destroyed, or modern metalling has obliterated the evidence. From what survives it would appear that few roads had an agger exceeding 3 ft. in height; a notable exception, however, is the road from Old Sarum to Badbury Rings (Ackling Dyke), where the agger is much more massive. Where cross-sections have been cut through roads the agger is normally found to be composed of local materials capped by gravel metalling (where it survives). Side ditches, though occasionally visible on the ground, have often been obliterated by later tracks or ploughing; in arable they can sometimes be seen on air photographs. It is not certain, however, that the roads were accompanied by side ditches throughout their length; none was found, for example, in a recent excavation of the BadburyDorchester road in Thorncombe Wood (see Road V).

As yet little is known of the date and sequence of construction of the various roads, but that from Hamworthy to Badbury, and perhaps to Bath, is likely to have been laid out in the early phases of the Roman conquest. The settlement at Hamworthy, which has yielded evidence of Claudian occupation (Dorset II, 603–4), appears to have been the port for Poole Harbour and one of the main ports of entry into Britain from Gaul. Immediately beside the road, a few miles inland, is the Claudian military site at Lake Gates (Pamphill (69), p. 51). If the road indeed continued to Bath it will have provided a valuable direct link between the south coast and the Foss Way, which appears to have functioned as the spine of a frontier system in the early years of the Roman conquest (Arch. J., CXV (1958), 49–98); Britannia, I (1970), 179–84). Air photographs suggest that this road is earlier than that from Badbury Rings to Dorchester, for the side ditch of the latter appears to cut it, but excavation is needed to determine the relationship with certainty. The probable existence of an early military site at Dorchester prompts the thought that the road linking it with the coast at Radipole might also be a very early one; similarly, perhaps, the road which continued to the Foss Way at Ilchester.

The roads cut a number of earlier features, most of them probably already obsolete, but some they may well have put out of use. Ackling Dyke, for example, cuts Bronze Age disc barrows, an Iron Age enclosure (Gussage St. Michael (8), p. 24) and probably 'Celtic' fields (Group (85), p. 118). The Ilchester and Exeter roads from Dorchester both cut Iron Age enclosures. More important, however, is the apparent impact of the roads on contemporary native settlements. Some of the largest and probably most thriving Romano-British rural settlements, whether pre-Roman in origin or not, lay close to Roman roads and by implication derived much economic benefit from their presence. Examples are Gussage St. Michael (7), p. 24; Pentridge (15), p. 55; Wimborne St. Giles (36), p. 100; Bere Regis (120), Dorset II, 594, and Tarrant Hinton (17–19), Dorset IV, 99–100.

The main road S.W. across Dorset from Old Sarum to Exeter is also likely to be of early origin; a large garrison was already established in Exeter before the end of Claudius's reign and Legio II Augusta is known to have been in Dorset even earlier than this. The course of the road was followed by Iter XII and Iter XV of the Antonine Itinerary. The distances from Old Sarum (Sorbiodunum) to Vindocladia (usually identified with Badbury Rings), and from Vindocladia to Dorchester (Durnovaria) are given in the manuscripts as xii and viii Roman miles respectively. To agree with reasonable precision with the actual distances of 23 and 20 Roman miles, an emendation of these figures is required to xxii and xviii, a solution explained by the omission of an x from each (Britannia, I (1970), 61). The only names in the Ravenna Cosmography which can probably be identified with sites in Dorset are Ibernio and Bindogladia; these occur as adjacent entries in the Exeter-Winchester section. Ibernio, presumably on the R. Iwerne, is possibly identifiable with the villa at Iwerne Minster (15), (Dorset IV, 40–1), suggesting a road running in that direction from Badbury Rings (Arch., XCIII (1949), 25, 35). The suggestion (Dorset Procs., 89 (1967), 160–3) that the Exeter-Winchester route followed a downland course across Dorset and that Bindogladia is the native settlement at Woodyates (Pentridge (15), p. 55) has met with little support. Bindogladia and Vindocladia are clearly identical.

Many of the Roman routes continued to be used as roads or tracks in post-Roman times. The roads from Dorchester to Ilchester and Exeter and probably that to Radipole have remained in use as major routes virtually throughout their length. The Old Sarum-Badbury road is followed by tracks for much of its length, as to a lesser extent is its continuation to Dorchester. The Badbury-Donhead road, on the other hand, is almost entirely ignored by them.

In addition to the known roads, certain other routes or features have been suggested as possible Roman roads, but none of these is confirmed. A route from Dorchester to Wareham crossing Worgret Heath has been claimed as Roman (Hutchins I, pp. vii and 78), but the evidence is entirely circumstantial (Dorset II, 539). The possibility of a road from the Ringwood area meeting the Hamworthy-Badbury road, S. of the crossing of the R. Stour, is suggested by a possible agger running S.W. near Park Farm, Wimborne (SZ 034997), and by a straight earth ridge which is traceable for 200 yds. from N.W. to S.E. near Lake Farm, Pamphill (Margary, op. cit., 95). This ridge was sectioned at SY 99949926, but there was no confirmation that it was a Roman road (Dorset Procs., 87 (1965), 100). The presumed line would have crossed the present course of the R. Stour three times. The straight parish boundary running N.W. from Badbury Rings has suggested a road to Hod Hill, perhaps continuing N. as a ridgeway (Codrington op. cit., 255), but no conclusive evidence of a road on this line has yet been found. The Roman fort at Hod Hill was evacuated so early that it is unlikely that a metalled road had been built; such a road, however, might have relevance to the site of Ibernio, mentioned above.

Roads I and II—see Dorset II, 528–31. Part of Road II is illustrated on Plate 87 in Dorset V.

Road III. Badbury Rings to Donhead (Bath?).

At Badbury Rings the road from Hamworthy turns sharply through 20° from N.W. to N.N.W. and continues towards Bath (Margary's No. 46). At this bend it is joined by the road from Old Sarum. Most of its course in Dorset has been obscured by ploughing, but a few fragments of the agger survive and much of its line may be traced on air photographs. In arable just N. of Badbury Rings the narrow side ditches, about 75 ft. apart, and the levelled agger are clearly visible from the air (Plate 87) and at the crossing here they appear to be overlain by the road to Dorchester. A little further N. a ditched enclosure of about 5 acres, one of a group of features now levelled (Pamphill (73)), adjoins the road. From here the road is traceable on air photographs almost without a break as far as Sing Close Coppice (ST 956057) in Tarrant Rushton (CPE UK 1975:1002–3; 2102: 4248–9; 1893: 3072–3, 3096–7, 4073– 4; 1934: 1123–4, 3152–2; 1845:2053. C.U.A.P., ANC 80, 82).

Remains of the agger survive in Hogstock Coppice (ST 954072), but beyond, where it descends The Cliff to follow the E. side of the Tarrant valley, its course has been obliterated. To the E. of Tarrant Monkton and throughout Tarrant Launceston the line of the road is marked by field boundaries, but in Tarrant Hinton it is completely ignored by them, except for a pronounced kink in a hedge at ST 94121131. In Tarrant Hinton parish the road has been levelled or severely reduced by ploughing, but its line is clearly seen on air photographs (N.M.R., ST. 9510/1; CPE/UK 1934:2151, 4151). Northwards through Eastbury Park, Tarrant Gunville and Ashmore there is little left of the agger, but in some fields it is still visible as a very low rise about 30 ft. across. On Main Down (ST 931145) it is followed by a field hedge. To the N.E. of Mudoak Wood (ST 92251705) it is clearly visible crossing an earlier boundary dyke (Ashmore (16), Dorset IV, 3). Beyond this the road enters Wiltshire and on Woodley Down in Tollard Royal it is met and followed by a modern road to Ludwell. It is traceable to the R. Nadder at Donhead St. Mary, but beyond this its course is far from clear. It has been claimed that it continues N.N.W. on the same alignment to link with the known Roman road from Bath to Frome (J. B. Berry, A Lost Roman Road (1963)).

A number of sites lie close to the road, but so far only two have yielded any evidence of occupation in the Roman period: the villa near Hemsworth (Witchampton (22)) and the native settlement at Tarrant Hinton (19), (Dorset IV, 100). The relationship to the road of enclosures at Tarrant Gunville (32) and (34) and at Tarrant Launceston (19), (Dorset IV, 96, 106) is at present unknown.

Road IV. Old Sarum to Badbury Rings.

The road from Old Sarum to Badbury Rings (Margary's No. 4c) enters the county just N.E. of Woodyates, which presumably takes its name 'the gate in the wood' from the passage of the road through Bokerley Dyke, the massive late Roman defensive earthwork which here forms the county boundary. At this point the road changes alignment 17° towards the S. and for a mile it is followed by the modern road (A 354), which then diverges westwards. The Roman road continues across Oakley Down and cuts two disc barrows (Wimborne St. Giles (106) and (111)) on the edge of a large group there. The well-preserved agger (Plate 87), often flanked by later tracks on one or on both sides, is now known as Ackling (?Oakley) Dyke. On Wyke Down the agger forms the parish boundary between Gussage All Saints and Wimborne St. Giles; it then crosses the Dorset Cursus (Gussage St. Michael (9)) and becomes the parish boundary between Gussage All Saints and Gussage St. Michael. The agger survives along the edge of The Drive Plantation, but beyond Harley Down it is increasingly damaged by tracks and after a short distance the line of the road is assumed by James Cross Lane, which continues to the Gussage Brook. On the far side of the stream, on Sovell Down, the road bends S.E. and then back to its former line, apparently to negotiate the slope; the angle is now occupied by a chalk pit. Beyond this, in Moor Crichel, its line is for part of the way a track, but in The Rookery wood the agger is preserved and in the arable fields near by it is still visible as a low ridge. Through Witchampton parish and into Pamphill the road is obscured by a later track, but the agger survives on the edge of the copse beside King Down Farm. The Roman villa and the Roman temple in Witchampton (22) and (23) lie on either side of the road, within a mile of it.

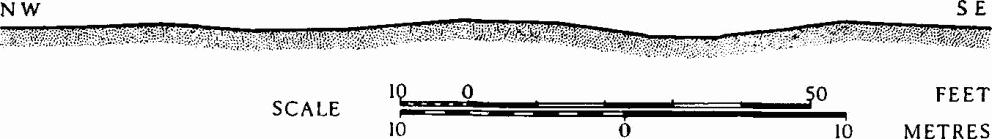

Road IV. Profile S. of Oakley Down (SU 017166).

The junction of roads N.E. of Badbury Rings is described and illustrated in Dorset II (pp. 528–9). It seems likely that the Old Sarum-Badbury road was initially continuous with the road which comes from Hamworthy and Poole Harbour, and that the branch from Badbury to Dorchester, though also early, was secondary.

Where best preserved, as on Oakley Down, the road has an agger 40 ft. to 50 ft. wide and from 4 ft. to 6 ft. high with remains of gravelled metalling. Such a height seems unnecessary on well-drained downland and it has been suggested that the intention was either to overawe the native inhabitants, or to make effective use of forced labour. The suggestion presupposes that the present agger was an early feature of the road, an hypothesis which as yet lacks support. The method of construction is known from several cross-sections. When cut at Woodyates in the 18th century three successive layers, each 1½ ft. thick, of gravel, chalk and flint were noted (Hutchins I, vi). In 1888–90 General Pitt-Rivers cut two sections N.E. of Bokerley Dyke. In trench IV the agger was 40 ft. wide and 3 ft. high between V-shaped ditches 83½ ft. apart (centre to centre), 3 ft. to 4 ft. wide, and 2 ft. to 4 ft. deep. Its construction consisted, from the surface downward, of 5 ins. of surface mould, 6 ins. of rammed chalk rubble, a layer of gravel 10 ins. thick, a further 6 ins. of rammed chalk and, resting on the old ground surface, a single layer of nodular flints. In trench III the agger was lower and contained sherds of New Forest Ware, nails and a glass bead; the ditches were only 56½ ft. apart, centre to centre. Other sections showed that the original W. road ditch cut into a 1st-century pit containing a burial. It was also found that the ditch of Bokerley Dyke had been cut through the road in the late 4th century, but was soon refilled and metalling laid down over the filling; later it was recut and not refilled (Pitt-Rivers, Excavations III, 21, 69–70, 74, 80, 91. Pls. clxvi, clxxi). A cutting made through the road for a modern Forestry Commission track on Oakley Down (SU 01931709) showed an agger 2 ft. thick composed of layers of fine chalk, gravel and earth, sometimes mixed, overlying a spread of flints.

Road V. Badbury Rings to Dorchester.

Road V. Profile N. of Badbury Rings (ST 962032).

The road from Old Sarum divides immediately N.E. of Badbury Rings and one branch of it (Margary's No. 4e) heads S.W. towards Dorchester. After a short distance it crosses the Badbury-Bath road, which appears on air photographs (Plate 87) to be structurally the earlier of the two; as yet, however, there is no reliable evidence for the date of the layout of the roads nor for their structural history (Dorset II, 528–9). Along the N. side of the hill-fort and the Roman settlement (Shapwick (34), (31)) the road survives as an impressive agger, up to 65 ft. across and 5 ft. high, scarred by quarrying and by numerous tracks, and flanked in places by side ditches and outer banks; in places the total width is 120 ft. Three prominent barrows (Shapwick (47–49)), in line beside the road, are no longer accepted as Roman (Ant. J., XLV (1965), 41–7). To the W. of the Blandford-Wimborne road the Roman road has been destroyed by ploughing and by the modern road to Shapwick, which approximately follows its line. The road passes through the village, where traces of early Roman occupation have been found (Shapwick (33)), crosses the Stour just S. of the church and continues as a slight agger across the floodplain of the river. For some 3 miles beyond this it has been levelled by cultivation, but much of it is visible on air photographs (CPE/UK 1934:3105–6, 3131–5, 5128–9). In Sturminster Marshall the former old fieldnames Greatstreet and Kingsway recall its presence. A short length of the road survives as an earthwork, 40 ft. across and 2 ft. high, immediately N. of the main ride in Little Almer Wood (SY 906998). From Winterborne Zelstone to Winterborne Kingston its line is marked by field hedges and for much of the way by a lane. On the summit of a spur, where the road crosses the parish boundary into Anderson, it changes direction by 9° to the N. Traces of the agger survive in Winterborne Kingston, E. and S. of Abbot's Court, alongside a lane known as East Street; the lane then follows the line of the road into the village.

Road V. Profile in Little Almer Wood (SY 906998).

Beyond Winterborne Kingston the road has been largely destroyed by cultivation, but the agger, some 40 ft. across and 4 ft. high, survives in Bagwood Coppice (SY 852971). Remains of a substantial Romano-British settlement have been found on either side of the road within and W. of this coppice (Bere Regis (120), Dorset II, 594). On Bere Down (SY 846969) the road, poorly preserved, passes through and probably cuts across 'Celtic' fields (Group (32), Dorset II, 633). A section through the road at this point revealed metalling 20 ft. wide in the form of a thin layer of flints and small stones on sandy clay over the chalk rock. It lay between wide, but shallow side ditches, 59 ft. apart centre to centre (Dorset Procs., 71 (1949), 60). Fragments of the agger survive on either side of the valley of the Milborne Brook: on the slope E. of Ashley Barn Farm (SY 816906) where it is flanked on the S. by a deep hollow way, and S.W. of Ashley Barn Farm (SY 810904) where a wide ditch flanks it on the N. side. The road is followed by a track to a point just N.E. of Tolpuddle, but there is no certain trace of it on the outskirts of that village, although a strip lynchet at SY 79509474 appears to mark its alignment. The drains and ridges of the water-meadows have obscured the road where it crosses obliquely the flood-plain of the R. Piddle, but its line is preserved in part of the S. boundary of Burleston parish.

In High Wood and Cowpound Wood, Athelhampton (SY 770937), where Reading Beds overlie the Chalk, a hollow way and a terrace mark the line of the road. Its course in the arable beyond is visible on air photographs (CPE/UK 1934:4074–5; 2018:3041–2). Traces of the agger survive, again on Reading Beds, in Ilsington Wood and also on Castle Hill and Puddletown Heath, now within the conifer plantations of Puddletown Forest. Near the W. edge of the forest the road curves sharply N.W. to avoid a steep-sided hollow, but after 160 yds. it resumes its course S.W. across Duddle Heath. Here the agger is 30 ft. across and up to 3 ft. high with occasional traces of side ditches and outer banks. Just to the W., in Thorncombe Wood (SY 727920), a section cut across the agger showed that it was composed of gravel laid directly on the ground surface; hollows in the top were interpreted as wheel ruts; no side ditches were found (Dorset Procs., 92 (1970), 147–8). A short length of the agger survives in pasture on Hollow Hill (SY 71859167) and slight traces of it are still detectable along the N. side of the present road skirting Kingston Maurward Park. The alignment if continued would carry the road down Stinsford Hill, N. of the modern A 35, across the flood-plain of the R. Stour, towards the presumed E. gate of Roman Dorchester at the foot of High East Street. No convincing surface traces of this section of the road have yet been found, but a ford (or bridge?) apparently of Roman date, discovered in the bed of the Stour in the last century, lies on the same alignment (Dorset II, 540). An uninscribed milestone, probably Roman, stands beside the line of the road at the top of Stinsford Hill (SY 70899130; Dorset III, 257).

Road VI. Dorchester to Ilchester.

For much of its course the road N.W. from Dorchester (Margary's No. 47) has remained in use to the present day and is perpetuated by modern roads. It leaves the town as Poundbury Road, the E. end of which points towards the traditional W. gate at Top o' Town, and takes a fairly straight line towards Bradford Peverell, diverging only to negotiate the steep-sided re-entrant of Fordington Bottom. Within this distance the road must have intersected the line of the Roman aqueduct to Dorchester at least six times. Beyond Bradford Peverell it crosses the Frome valley to Stratton; according to Hutchins (I, vii) its line was formerly visible in the water-meadows, but there is no clear trace of it today. At Stratton the road meets another road which appears to have served as a bypass N. of Dorchester. This road (Margary's No. 470) leaves the Badbury-Dorchester road at Stinsford and, except for a short length near Charminster church, is followed by existing roads and lanes. Evidence of Roman occupation has been found close to the road-line at SY 698914 (Dorset Procs., 94 (1972), 87). A marked kink in the alignment at Westleaze (SY 685922), on the line of the old road from Dorchester to Charminster via Burton, raises the possibility that the latter, itself probably part of a pre-Roman trackway, was incorporated in the Roman road network. For further discussion of this road see Dorset II, 539, 541–2, 587.

N.W. of Stratton the Roman road has been largely flattened by ploughing and by a track which follows its line, but just N. of a disused railway (SY 646941) the agger survives as a ridge 36 ft. across and up to 3 ft. high. To the W. of the Sydling Water its line is assumed by Long Ash Lane, the modern road to Yeovil (A 37), which climbs and follows the top of the ridge. The agger, 30 ft. across and 2½ ft. high, survives in Hyde Crook Belt (SY 627960) where the modern road deviates slightly to the E. A cross-section here showed a metalling of angular flints with some small pebbles on a foundation of brown loamy earth (C. D. Drew, unpublished notes in D.C.M.). On Hog Cliff Hill (SY 625965), where the road bisects an early Iron Age enclosure, excavation has produced evidence of Roman metalling beside the modern road (Dorset Procs., 82 (1960), 83).

Beyond this the road follows the ridge as far as Wardon Hill, where it curves W. to descend a spur and cross the valley at Holywell. Along the E. side of Melbury Park and continuing N.W. to Princes Place (ST 575093), the modern road follows a more irregular line and presumably makes several minor deviations from the course of the original road; no certain traces of the latter have, however, been found to confirm this. Beyond Princes Place a straight length of the modern A 37 carries the road to the Somerset border near Closworth.

Road VII. Dorchester to Exeter.

The road (Margary's No. 4f) leaves the former W. gate of Dorchester at Top o' Town and for 3 miles is followed by the present main road (A 35). Over much of this distance the raised nature of the modern road suggests that it lies astride an agger which has perhaps been widened to accommodate it. On Lambert's Hill (SY 632908) the A 35 turns S.W. and the Roman road, followed by a minor metalled road, continues in a series of straight alignments along the top of the Chalk ridge as far as Two Gates (SY 552938), just S.E. of Eggardon; again there is evidence of the agger at intervals. From the outskirts of Dorchester to a little beyond this point the road is followed without a break by parish boundaries. Throughout this part of its course the road passes close to settlements and 'Celtic' fields (Dorset II, 623–4). N. of Long Bredy it crosses an Iron Age enclosure at SY 575936 (Dorset Procs., 87 (1965), 81–3).

At Two Gates the metalled road turns N.W. towards Eggardon and the Roman road continues W. as a track. After nearly ½ mile it is joined and followed by another minor road, the Spyway, running S.W. from Eggardon Hill. In the obtuse angle between the two roads (SY 545939) a short length of the agger survives; it is about 25 ft. across, but damaged by shallow quarrying. The Roman road makes its way along the top of a spur and then makes a steep descent to Spyway Green, just N. of Askerswell, where it leaves the Chalk. Here traces of it were seen in the early 19th century (J. Davidson, Roman Remains in the Vicinity of Axminster (1833), 54). Beyond this its course is less well established, but it seems likely that it continues as the present road to Vinney Cross (SY 510929) where it is met and followed by the main road (A 35) to Bridport. A possible alternative route to the N. follows the Asker valley beyond Spyway Green, via Matravers and Uploders as far as Yondover, where it turns S.W. on the line of a modern track to join the A 35, ½ mile E. of Bridport, at SY 480932.

From Bridport to Morecombelake the line of the Roman road is essentially that of the present main road. Both in Bridport and in Chideock remains of an older road, probably Roman, have been found 2 ft. to 4 ft. below the present road surface (Dorset Procs., 71 (1949), 61–2; 73 (1951), 102). Beyond Morecombelake the Roman road probably crossed Stonebarrow Hill, on the line of the present track, to Charmouth; the route followed by A 35 is apparently a modern one. West of Charmouth the road may have divided. The main route, however, is almost certainly that followed by the A 35 to Penn Cross (SY 348943), then by a minor road as far as Penn and finally by A 375 to the Dorset border on Raymond's Hill. It continues to Axminster, where it must cross the S. end of the Foss Way; thence to Exeter via Honiton. A possible second road W. from Charmouth (Margary's No. 49) followed a more southerly route, now marked by tracks over Timber Hill (SY 350933) and by a minor road N. of Lyme Regis, beyond which it leaves Dorset and is perpetuated as far as Exeter in the modern A 35.

Mediaeval and Later Settlement

The pattern, siting and morphology of mediaeval and later settlement in East Dorset has been determined to a large extent by the two distinct physical regions into which the area is divided.

The Chalk Lands of the North-West

As elsewhere in Dorset, settlement on the Chalk has, until recently, been mainly confined to the valleys, where both water and shelter are most readily available. Documentary evidence, here and there supple mented by earthworks, shows clearly that by the early mediaeval period lines of settlement—villages, hamlets and farms—were strung out in the bottoms of the valleys. Most of these survive and are of similar status today, though generally they have increased in size. Some, such as Bowerswain Farm in Gussage All Saints (6), have remained isolated farms; others, such as Brockington (Gussage All Saints (19)), Hemsworth (Witchampton (20)) and Knowlton (Woodlands (16)), have been reduced from more populous settlements to single farmsteads, or have been abandoned altogether. Most of these settlements are of linear form, lying along a single street, parallel to a stream as at Long Crichel, or sometimes along two streets as at Wimborne St. Giles. Where a valley is very broad and shallow, and settlement is less constricted, compact villages with an irregular street plan are to be found; e.g. Shapwick and Witchampton. As noted in other parts of Dorset, most chalkland settlements are associated with narrow strips of land which extend back from the streams on to the downland, on one or both sides; the boundaries of these strips are often perpetuated in the form of continuous hedgerows.

In the N. part of the area, towards the top of the dip-slope of the Chalk, where the valleys are shallow and waterless, settlement is more dispersed; a thin scatter of farms and hamlets is found, but Sixpenny Handley is the only large village. The number of Romano-British settlements known in this region suggests that the area (if not the settlements themselves) has been continuously occupied since Romano-British times.

The Eocene Deposits of the South-East

Along the edge of the Eocene deposits, but just on the Chalk, a line of early settlements extends S.W. from Cranborne to Wimborne Minster and then E. to West Parley. Only Chalbury lies on the Reading Beds. Most of these settlements are small compact villages, usually of single-street type; e.g. Edmondsham, Hinton Martell and Horton on the Chalk; Dudsbury, Hampreston and Longham on the valley-gravel terraces of the R. Stour. Wimborne Minster also developed on such a terrace, at an important crossing of the R. Stour, near the junction of the Eocene and the Chalk. Within the Eocene deposits the pattern of settlement is dispersed and irregular. On the Reading Beds and the London Clay a general scatter of farmsteads and cottages is found, together with straggling villages and hamlets; often they are centred on triangular or irregular greens; Holt, Gaunt's Common, Pamphill, Woodlands and Woodlands Common are examples. Within the heathland proper on the Bagshot Beds, an area thinly peopled until relatively recently, hamlets and farmsteads are also found, but they tend to be restricted to the valleys of the small streams which cross the outcrop. Some of these settlements on the Eocene deposits were in existence by the 11th century (Petersham and Mannington Farms in Holt); others do not appear in documents until the 13th or 14th centuries, although they may well be older.

Large numbers of late 18th and early 19th-century cottages on the edge of and within the heathland, represent expansion of settlement on to marginal land at a time of growing population. Some of these settlements (e.g. Holt (31)) have been abandoned.

The history of settlement in this area is reflected to a large extent in the distribution and size of the parishes, notably the ecclesiastical parishes as they were until the 19th century. These were all centred on the line of early settlements along the edge of the Eocene deposits. Some, e.g. Edmondsham, Chalbury and Hinton Martell, were of moderate size and have remained so, but others were larger, incorporating extensive tracts of sparsely inhabited heathland, and these have since been sub-divided. From Cranborne, once one of the largest parishes in Dorset (13,000 acres), have been taken the present parishes of Alderholt and Verwood; from Wimborne Minster, little smaller than Cranborne, the parishes of Holt, Pamphill and much of Colehill (the remainder is from Hampreston); from Horton has been taken the parish of Woodlands which incorporates the lands of the former village and chapelry of Knowlton. The need for separate parishes on the heathland less remote from the old centres of settlement was due to the steady increase of population in this area, in particular from the early 19th century onwards. The increase has accelerated rapidly in the present century with the northward expansion of the suburbs of Bournemouth, and this has necessitated the creation of the civil parish of West Moors.

Mediaeval Settlements East Dorset

Mediaeval and Later Earthworks

Relatively few earthworks of demonstrably mediaeval or later date have been noted in East Dorset. Remains of former settlements within and near existing villages and farms include Long Crichel (4), Minchington (Sixpenny Handley (17)), Brockington (Gussage All Saints (19)), Hemsworth (Witchampton (20)) and Didlington (Chalbury (8)). Only at Knowlton (Woodlands (16)) is the settlement site completely deserted.

At only two sites is shrinkage or desertion dated; at Moor Crichel (8) the village was demolished between 1765 and 1770 for the enlargement of the park at Crichel House; at The Leaze, Wimborne Minster (82), excavations suggest a short-lived extension of the town in the 12th and 13th centuries. Little is known of the date of and reasons for the shrinkage of other settlements. None has been excavated and documents have so far proved of little help. At Knowlton, for example, the apparently high population recorded in 1333 (compared with later evidence) suggests that the village was deserted in the late 14th or early 15th century; the figure for 1333, however, includes the population of outlying settlements in the parish as well as of Knowlton village and is, therefore, of little value in determining the size of the village at that time.

Cultivation remains are negligible, but on the heathland numerous abandoned closes, such as Holt (31), Horton (14) and Verwood (57), are evidence of temporary extension of farming on to marginal land. The presence of a substantial motte-and-bailey castle at Cranborne (31) serves to confirm the early importance of what is still one of the largest settlements in the area.

Mediaeval and Later Buildings

Ecclesiastical Monuments

Cranborne. Saxon carving.

The Saxon stone carving [9] here illustrated was discovered in a pond at Cranborne in 1935 and is probably a terminal knop from a mural cross. Measuring 19 ins. by 18 ins. overall, the fragment can hardly belong to a free-standing cross as it is only 6 ins. thick and the sides are convex, but it could be the end of one limb of a cross built into a wall like the well-known example at Romsey. Whether it should be seen as the foot of the cross or as the end of the right-hand arm is uncertain; the beast is sufficiently fantastic to be as much at home in a vertical as in a horizontal posture. One fore-foot is inserted in the mouth. The long branched tail penetrates the body, a mannerism held to indicate a 9th-century date (Kendrick, Anglo-Saxon Art to A.D. 900, 145; Arch. J., CIV (1947), 162). The pre-conquest Benedictine Abbey of Cranborne, later a cell of Tewkesbury, was founded c. 980 (Knowles, Religious Houses of Mediaeval England, 61), but it probably succeeded a group of secular canons serving an Old Minster, to which Dugdale refers (Hutchins III, 381). Another Saxon monument is represented by a fragment of coarse tessellated pavement discovered in 1857 in the nave of Wimborne Minster church. Lying some 9 ins. below the present floor it may well be a part of the church built early in the 8th century by St. Cuthburh, sister of King Ine of Wessex.

Before the Norman Conquest St. Cuthburh's original church at Wimborne was replaced by a cruciform building with a square crossing slightly wider in plan than the arms of the cross, and with a round turret at the external W. corner of each transept. Of this late Saxon building the W. walls of both transepts and the entire N.W. turret continue to stand almost to their full original height [1], contradicting Hutchins's assertion that 'no traces of the Saxon church can be discovered'. After the Saxon cathedral at Sherborne (Dorset I, xlvii–l), Wimborne Minster church is the most important Saxon building to survive in Dorset.

In the 12th century the church at Wimborne Minster was greatly enlarged, the nave being rebuilt with aisles and the eastern arms probably being provided with five apses, as at Shaftesbury (Dorset IV, opp. 58); the apses have gone, but the nave and the richly arcaded central tower remain the most impressive examples of Norman architecture in East Dorset. Also of 12th-century date is the village church, now a ruin, at Knowlton, in Woodlands parish; it is interesting for having been built, at some distance from the settlement, in the middle of a pre-Christian henge monument. Another early 12th-century monument is the W. tower of the parish church of Gussage St. Michael, where the plain tower arch is purposely enlivened by the contrasting colours of Greensand and Heathstone in alternate voussoirs. The adjacent hamlet of Gussage St. Andrew, now in the parish of Sixpenny Handley, has a small 12th-century chapel, altered in the 13th century. The parish churches of Shapwick and Edmondsham have simple 12th-century arcades. West Parley has a good 12th-century N. doorway with a Heathstone lintel surmounted by a semicircular tympanum; to heighten the opening, the underside of the lintel has at some time been given the form of a segmental arch. Hampreston has a reset 12th-century doorway in which three joggled voussoirs form a flat lintel. The N. doorway of Cranborne church is of the 12th century, but reset and altered in the 14th century; the nonradial arrangement of its voussoirs suggests that the pointed arch was originally segmental, a form noted at Pimperne in North Dorset (Dorset IV, 52) and at several places in Central Dorset (Dorset III, xlviii). The 19th-century church of Hinton Parva has an elaborate and much restored 12th-century chancel arch.

In the first half of the 13th century the eastern arm of Wimborne Minster church was rebuilt, the hypothetical centre apse being replaced by a Lady Chapel, with a square E. end pierced by three lancet windows surmounted by quatrefoil and six-lobed lights [68]; the carved stonework in these windows and in the adjacent N. and S. archways is particularly noteworthy. Other 13th-century buildings in East Dorset include the chancel of Gussage St. Andrew (in Sixpenny Handley), and the nave arcades of Gussage St. Michael. The domestic chapel of Cranborne Manor House, built in 1207, is represented by part of an altar recess with a piscina and a small E. window.

Of the early 14th century is the spacious chancel and aisleless nave of Gussage All Saints church. Other notable 14th-century buildings include the nave of Cranborne parish church [6], the vaulted crypt inserted below Wimborne's 13th-century Lady Chapel [66], the chancel and W. tower of Hampreston church, and the porch of Sixpenny Handley church [64].

Of the 15th century is the massive W. tower of Cranborne parish church [4]. It dates probably from before 1438, at which time the W. doorway was inserted, with shields-of-arms and portrait label-stops apparently commemorating the marriage of Richard, duke of York (Edward IV's father) and Lady Cecilia Neville; it may be conjectured that Cranborne Manor House was occupied by this royal couple. Of the middle of the 15th century is the W. tower of Wimborne Minster, with a tall, heavily moulded tower arch. Smaller 15th-century towers are found at Long Crichel, Witchampton, Edmondsham and Knowlton, the last in Woodlands parish.

Little church building of the 16th and 17th centuries is found in East Dorset; the most notable example is the weighty parapet [1] of the central tower of Wimborne Minster, erected in 1608 after the collapse of the spire.

The 18th century church at Horton [3] has a N. tower built in 1722–3, with a round-headed window with a plain keystone and architrave, a heavy modillion cornice and a pyramidal stone spire. These features were paralleled in Vanbrugh's great mansion, Eastbury, 7 miles to the N.W. (Dorset IV, 90). The mason at Horton was John Chapman (Colvin, 137) and it is probable that he also worked at Eastbury.

In 1732 (Hutchins, 1st ed., II, 219) the church at Wimborne St. Giles, the burial-place of the earls of Shaftesbury, was rebuilt by the 4th earl; it has an elegant W. tower [5] of classical form, not unlike that of Blandford Forum which was started in the following year, and a plain rectangular nave with large round-headed windows, also paralleled at Blandford Forum. The affinities suggest that the Bastard brothers were responsible for the design of St. Giles's as well as the Blandford church, although there is at present no documentary evidence to support the attribution. The interior of St. Giles's has been remodelled twice since 1850 and once burnt out, and few of the 18th-century fittings remain.

Small churches at Chalbury and West Parley retain 18th-century furniture.

The 19th-century church of Moor Crichel, now disused, is a pleasing and well-built edifice in the 'gothic' style, in striking contrast with the neo-classical mansion beside which it stands. It was built in 1850 at the expense of Mr. H. C. Sturt. Affinities of style suggest that the designer was George Alexander of Highworth, who in 1847 built Sutton Waldron church (Dorset IV, 84) 'on a piece of ground given by H. C. Sturt of Crichel' (Hutchins IV, 108), but no documentary evidence can be found to support the attribution.

Non-conformist chapels of 19th-century origin include the modest cob-and-thatch meeting-house built in 1807 at Cripplestyle in Alderholt (2), and a more impressive building at Hampreston (2), dated 1841.

Vaulting and Roofs

The oldest stone vault to remain in East Dorset covers the E. part of the crypt of Wimborne Minster church with six bays of quadripartite vaulting of c. 1300 [66]; in the next generation three bays were added, extending the crypt W. into the area of the former ambulatory. The earlier vaults have sunk-chamfered ribbing; in the added bays the ribs are wave-moulded. The N. porch of the same church has quadripartite vaulting of c. 1350, and the S. vestry has a 14th-century vault with moulded ridge and diagonal ribs meeting at a foliate boss. The W. tower of Wimborne Minster has 15th-century vaulting extensively restored after 1850. Apart from Wimborne Minster the only remaining mediaeval vault in East Dorset is a 14th-century ribbed barrel vault, two-centred in cross-section, covering the S. porch of Sixpenny Handley parish church [64]. It was taken down and rebuilt in 1877, but retains its original form. The mid 19th-century chancel of Moor Crichel church has fan-vaulting in the style of the 15th century.

Wagon roofs are found in churches at Cranborne, Shapwick and West Parley. The most noteworthy is at Cranborne [6], where the nave has a 15th-century roof of two-centred cross-section and the S. aisle has a lean-to roof of similar form, spanning from the wall-plate to the nave wall in a single arc. The nave of Gussage St. Michael has a low-pitched 15th-century roof with king-post tie-beam trusses with straight angle-struts; the near-by church of Gussage St. Andrew, in Sixpenny Handley, has a more steeply pitched 15th-century roof with tie-beam trusses with curved angle-struts. In the extended W. bay of West Parley church the wagon roof of the nave gives place to two late 16th-century trusses, designed to support a bell-cote.

Church Fittings

Altar: A large, roughly rectangular heathstone monolith lying on the ground inside the ruin of Knowlton church is perhaps the slab of a former altar, but no consecration marks are seen.

Bells: Few mediaeval bells survive in East Dorset. Two at Shapwick with inscriptions in Lombardic lettering are thought to be of c. 1380–1400 and from London, possibly cast by John Langhorne (Walters MS.); a small bell with a black-letter inscription in the same church is by an unknown 15th-century founder. At Cranborne the 5th, with Lombardic lettering, is of c. 1410 and from Salisbury. Gussage All Saints has three Salisbury bells of c. 1440–50; Holt has a plain mediaeval sanctus brought from Wimborne Minster in the 19th century (Hutchins III, 200, note a). There are no 16th-century bells in the area. Edmondsham, the Gussages and Long Crichel have 17th-century bells. Hampreston has three bells of 1738 by William Knight, and Witchampton has five of 1776–7 by Wells of Aldbourne.

Books: The 15th-century library in Wimborne Minster church contains a collection of chained books brought there in 1686; some are of the 16th century.

Brasses [20]: A small 14th-century inscription plate is reset in a 19th-century tomb in Long Crichel church. A figure representing King Ethelred in Wimborne Minster church is probably of 15th-century origin, but the accompanying copper inscription plate appears to be of the 17th century. Shapwick church has an early 15th-century figure of a lady and a 16th-century figure of a priest. Wimborne Minster has a brass with a black-letter inscription in memory of Elenor Dickenson, 1571, and Moor Crichel has a similar monument to Isabel Uvedale, 1572, with a figure of a lady. Small 17th-century brasses are found in the churches of Sixpenny Handley, Wimborne Minster and Wimborne St. Giles.

Candlesticks etc.: St. Andrew's church at Gussage in Sixpenny Handley parish has an 18th-century brass chandelier with three tiers of scroll-shaped sconce brackets projecting from a stout turned shaft with a large ball finial below it. At West Parley church the 18th-century pulpit retains a pair of original brass and iron candlesticks with swivelling brackets.

Carved Stonework: The only example of Saxon sculpture known in East Dorset, the carving at Cranborne, has been discussed on p. xxxvii. At Hinton Parva, part of the 12th-century chancel arch with shafted responds with spiral and imbricate ornament is incorporated with the late 19th-century church; the same church has a small stone panel, probably of the 12th century, on which a winged figure with a book and a cross is somewhat inexpertly depicted [9]; Sixpenny Handley parish church has a more sophisticated, but badly defaced 12th-century Christ-in-Majesty [9]. Undoubtedly the best examples of 12th-century carving to survive in East Dorset are the label-stops and keystones of the nave arcades in Wimborne Minster, where human faces and animals are skilfully portrayed [8]. Three 13th-century label-stops in the eastern arm of the same church are no less noteworthy [70]. Local 14th-century carving is exemplified in the crude enrichment of a wall-recess at Gussage All Saints [12]. That of the 15th century is represented by a triangular Purbeck marble panel preserved in the library of Wimborne Minster church; carved on one side with a crucifixion and on the reverse with the figure of a king [9], it is evidently part of a stone cross and it has been suggested that it might come from the top of the spire which collapsed in 1600.

Chests: Wimborne Minster church has a notable collection of wooden chests [71]; the oldest, possibly of the 13th century, comprises a massive oak trunk with a small recess hollowed out of it; it is closed by a thick wooden lid with strong iron hinges.

Communion Tables etc.: Oak tables of the 17th century with stout turned legs and enriched rails are preserved in the parish churches of Gussage St. Michael, Hampreston and Horton, in the chapels of St. Margaret at Pamphill and of St. Andrew at Sixpenny Handley, and in the crypt of Wimborne Minster. Horton church has an elegant 18th-century reredos of carved and gilded wood.

Easter Sepulchre (?): An arched recess [12] containing a tomb-chest of 15th-century date, reset in the 19th-century chancel of Cranborne parish church, presumably comes from the mediaeval chancel; it is uncertain whether it was originally an Easter Sepulchre or an ordinary tomb.

Fonts [18]: Twelfth-century fonts are found at Sixpenny Handley, West Parley and Woodlands. That of West Parley has a tub-shaped bowl decorated externally with raised arcading; being of diminutive size the original font now serves as the pedestal of a late mediaeval octagonal bowl. The early 13th-century font in Cranborne church has an octagonal bowl with lancet-shaped panels, nine cylindrical supports and an octagonal base with broached corners. The 14th-century font in Wimborne Minster is similar in form to that of Cranborne, but it has trefoil-headed panels and is more elegantly proportioned; the spirally-fluted centre support may be of 12th-century origin. Wimborne St. Giles has a 17th-century font brought from elsewhere.

Glass: Of English mediaeval stained glass East Dorset retains only a few 15th-century fragments. Panels of 16th-century German or Flemish glass were reset in Wimborne St. Giles church and Wimborne Minster church, the former in 1785, the latter in 1837.

Helmets (funeral) etc.: A well-preserved bascinet of c. 1510, now in the library at Wimborne Minster church [40], hung until recently over the 15th-century monument of the Duke of Somerset (d. 1444). Two mid 17th-century helmets with crests of the Okeden family are preserved in Moor Crichel church. Another with the crest of Uvedale hangs over the monument of Sir Edmund Uvedale, 1606, in Wimborne Minster; associated with the same monument is a wooden cap-of-maintenance.

Lectern: Wimborne Minster has a fine brass eagle lectern [21] dated 1623; the pedestal is modern.

Monuments and Floor-slabs: A recumbent effigy from an early 14th-century monument [11] in Wimborne Minster church bears a shield charged with three lions in an engrailed border; three stone shields similarly charged are built into the adjacent wall, the monument having been reassembled in the 19th century; Hutchins (III, 213) supposes the arms to be those of St. Piers, Peters or Fitzherbert. An effigy of the late 13th century at Wimborne St. Giles (Hutchins III, 603) was destroyed by fire in 1908 and only the original feet remain, the rest being modern. A mail-clad Purbeck marble effigy at Horton [10] bears a shield charged with the arms of Braose and probably comes from the tomb of Giles de Braose, d. 1305; an approximately contemporary effigy in the same church, carved in Ham Hill stone, is thought to represent his wife. Of the 15th century are splendid alabaster effigies in Wimborne Minster representing John Beaufort, Duke of Somerset (d. 1444) and his wife Margaret (Beauchamp) [10]; they lie on a tomb-chest with panelled, cusped and moulded sides, but without inscription (Hutchins III, 212).

Seventeenth-century effigies include that of Sir Edmund Uvedale, 1606, on an alabaster wall monument [14] in Wimborne Minster church. Fine effigies of Sir Anthony Ashley (d. 1627/8) and his wife (Jane Okeover) are preserved in a magnificent tomb [13] in the parish church of Wimborne St. Giles. The kneeling figure beside the bier presumably represents their daughter Anne, who died shortly after her father; as there is no reference to her death the monument is closely dated between January and August 1628. It was erected by Anne's husband, Sir John Cooper of Rockbourne, progenitor of the Ashley-Cooper family.

Canopied and mural table-tombs include one of 14th-century origin in Gussage All Saints church [12]; it has been called an Easter Sepulchre, but when opened in 1864 it was found to contain bones (Dorset Procs., XVII (1896), 84). A 15th-century arched recess reset in the 19th-century chancel of Cranborne parish church might also be a tomb in origin although we classify it doubtfully as an Easter Sepulchre (above). In Shapwick church a small 15th-century arched recess with a Purbeck marble surround with cusped panelling contains a tomb-chest of 1639. The 16th-century table-tomb of Gertrude, Marchioness of Exeter (d. 1558) on the N. side of the chancel in Wimborne Minster retains part of the original brass margin-plate. William Bastard's 18th-century plan of the church (Bodleian Lib., Gough Maps 6, f. 48v.) shows this tomb on the S. side and that of the Duke and Duchess of Somerset on the N. side of the chancel, but this must be a mistake in the drawing since scratchings on the duke's effigy show that the N. side of the monument was easily accessible in 1641.

The more important of the 17th-century wall monuments in East Dorset are illustrated on Plates 14–16. In design nearly all have much in common, but the Sherley monument at Shapwick is exceptional and of more refined quality. Affinities of style suggest that the Cole monument at Witchampton and the Hussey monument at Shapwick are from one workshop, and the same rather distinctive hand is probably seen in some of the Coker monuments at Mappowder (Dorset III, 146).