An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in the County of Northamptonshire, Volume 5, Archaeology and Churches in Northampton. Originally published by Her Majesty's Stationery Office, London, 1985.

This free content was digitised by double rekeying. All rights reserved.

'The Development of Northampton', in An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in the County of Northamptonshire, Volume 5, Archaeology and Churches in Northampton(London, 1985), British History Online https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/rchme/northants/vol5/pp27-71 [accessed 26 April 2025].

'The Development of Northampton', in An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in the County of Northamptonshire, Volume 5, Archaeology and Churches in Northampton(London, 1985), British History Online, accessed April 26, 2025, https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/rchme/northants/vol5/pp27-71.

"The Development of Northampton". An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in the County of Northamptonshire, Volume 5, Archaeology and Churches in Northampton. (London, 1985), British History Online. Web. 26 April 2025. https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/rchme/northants/vol5/pp27-71.

In this section

THE DEVELOPMENT OF NORTHAMPTON

Introduction and Sources

The area covered by the present volume, the modern District or Borough of Northampton, comprises a large part of the Upper Nene basin (Maps 1, 3). It is in many ways archaeologically and historically an artificially small area, yet it has been a focus for several thousand years for the surrounding countryside and the restricted geographical area of study perhaps concentrates attention on the theme of the continuity of a preferred location. Northampton is possibly one of the least recognised of English historical centres. It was ravaged by fires in the medieval and post-medieval periods, its town walls were largely demolished in the 17th century and what remained of its castle was almost totally destroyed for railway improvements in the late 19th century. In the 12th and early 13th centuries, however, it was one of the foremost centres of the kingdom and can now be seen to have been an important royal centre in Saxon times with antecedents stretching back still further.

Sources for the history and archaeology of Northampton are relatively numerous. Original documents relating to Northampton's history are preserved in the Public Record Office, the British Library, Northamptonshire Record Office and elsewhere and many have been published, although much was presumably lost in the fires referred to above. John Bridges' county history, compiled before his death in 1724 but not published until 1791, still provides a fundamental grounding in the documentary evidence. The guides to Northampton by Whellan (1849; 1874) and Wetton (1849) seem to have gained a time-honoured authenticity yet, while they contain useful information, must be treated with the utmost caution. In the late 19th century a number of local personages, intensely interested in the local heritage, made 'rescue' observations in advance of and during the destruction of the interior of the Iron Age hill fort at Hunsbury, the Romano-British small town at Duston, Northampton Castle and various medieval religious houses and other structures in the town. Prominent among such people were Sir Henry Dryden, Samuel S. Sharp and Edmund Law. Edmund Law, who practiced as an architect, was also responsible for the restoration of some of the medieval churches in the area and Sir Henry Dryden was instrumental in establishing Northampton Museum, opened in 1866. A fine collection of local antiquities was housed and subsequently much developed by Thomas J. George, curator between 1884 and 1920 (cf. Moore 1979–81, parts 4 and 5; also Dryden 1873–4, 1875–6, 1885–6 and Dryden collections in NPL and NM; Sharp 1861–2, 1871a, 1871b, 1875, 1881–2; Law 1879–80; George 1903–4a, 1903–4b, 1903–4c, 1904, 1915–18, 1919). This early archaeological work was essentially concerned with collecting artefacts except where structural remains were patently obvious. While immense gratitude is due to these archaeological pioneers for what they salvaged, the inadequacies, by modern standards, of their records, the somewhat random selectivity of what was saved and erroneous identification of both artefacts and structures has necessitated careful reappraisal of all the early sources.

The later 19th century also saw a general awakening of municipal pride and an interest in the history of urban institutions. In 1898 the two volumes of the Records of the Borough of Northampton by C.A. Markham and J.C. Cox were published (Cox 1898; Markham 1898), bringing together, albeit with some errors and prejudices, much useful basic material for the town. At about the same time the Rev. R.M. Serjeantson published a fine series of works on the history of Northampton's castle, its churches and religious houses (Cox and Serjeantson 1897; Serjeantson 1901, 1904, 1905–6a, 1905–6b, 1908, 1909a, 1909b, 1909–10, 1909–12, 1911, 1911–12a, 1911–12b, 1911–14, 1913, 1915–16). His work remains a formidable body of evidence although the architectural analysis of the churches of Northampton by his collaborators was not always totally accurate.

Helen Cam's masterly study of the history of the town, published in 1930 in volume III of Northamptonshire of the Victoria History of the Counties of England, fully surveyed Northampton from the Norman Conquest onwards. It is particularly informative on constitutional aspects but, lacking the benefit of modern archaeological investigations, failed to appreciate both the importance of Northampton's pre-Conquest origins and the town's overall topographical development. This latter problem was tackled in a seminal paper by Alderman Frank Lee (1954) in which he used the surviving evidence of the street grid to postulate a model for the development of the town which appears to have been validated by subsequent research. Lee published little but his copious and valuable notes in Northamptonshire Record Office illustrate his insight into aspects of the town's growth.

Some limited archaeological excavation was undertaken in and around the town from the 1950's but the establishment of an archaeological unit by Northampton Development Corporation in 1970 brought about, in a 'rescue' situation, a coordinated research programme into Northampton's past which has continued for more than a decade and has provided a framework within which earlier work can be assessed.

Much has been published in recent years on Northampton, mainly as excavation reports and studies of aspects of its history (in particular Williams 1979, 1982a, 1982b, forthcoming; Williams and Shaw 1981, forthcoming). This survey does not seek to retread such ground in all-embracing detail but rather attempts to draw out themes relating to the history of the area as manifested by its physical remains. Finds and records of archaeological material from the Northampton area are comprehensively listed in the Inventory. The main sources are publications, material deposited in Northampton Museum and the records of Northampton Development Corporation's Archaeological Unit and of the Royal Commission on Historical Monuments. Fuller discussion and further detail may be sought through the comprehensive bibliography. Medieval constitutional and political history is only discussed as a background to the study. Since the Church figured prominently in medieval Northampton the standing medieval churches within Northampton have been surveyed; their architectural significance is discussed below and they are described in the Inventory. Surviving medieval and later secular buildings, however, fall outside the scope of the volume.

Relief and Geology (Maps 1, 2)

The Upper Nene basin comprises a broad valley bottom between 50 metres and 60 metres above sea level with ground rising gradually on either side to a maximum of c. 125 metres above sea level; a number of tributary streams cut the higher ground to join the Nene itself. The alluvial flood plain is damp but the surrounding land is well-drained with extensive deposits of gravel and Northampton Sands as well as other Jurassic strata and would have been attractive for settlement.

The Prehistoric Period

Palaeolithic Remains (Map 4)

The evidence concerning palaeolithic material in the Northampton region, as elsewhere, is of a different order from that for later periods of prehistory, not least because it is largely derived from geologically disturbed and insecurely dated deposits such as river gravels. It is, therefore, considered here separately before discussion of the rest of the prehistoric period.

Palaeolithic tools and pleistocene faunal remains have been found quite frequently, principally during gravel extraction along the Nene valley. Hand axes are the most commonly discovered implements; two from Northampton (fiche, p. 321) are dated to the early Acheulean period while one from Great Billing (1) is middle to late Acheulean. The only site to have received any detailed analysis is a gravel pit at Great Billing (1) where remains of woolly rhinoceros, horse and mammoth were collected along with some palaeolithic flints, including a small Levallois flake, and a date within an interstadial of the Devensian glaciation (c. 40000–35000 BC) is possible. Organic silts interbedded with the gravels in the same pit produced more detailed evidence of flora and fauna and yielded a radiocarbon date of 28225 ± 330 BP.

Mesolithic to Iron Age Remains and Settlements (Maps 4,5)

The number of sites and isolated finds of mesolithic to Iron Age date recorded within the boundaries of the greater Northampton area is considerable. Since such boundaries are irrelevant to the pattern of prehistoric settlement, the distribution maps can be understood only by reference to a much wider area.

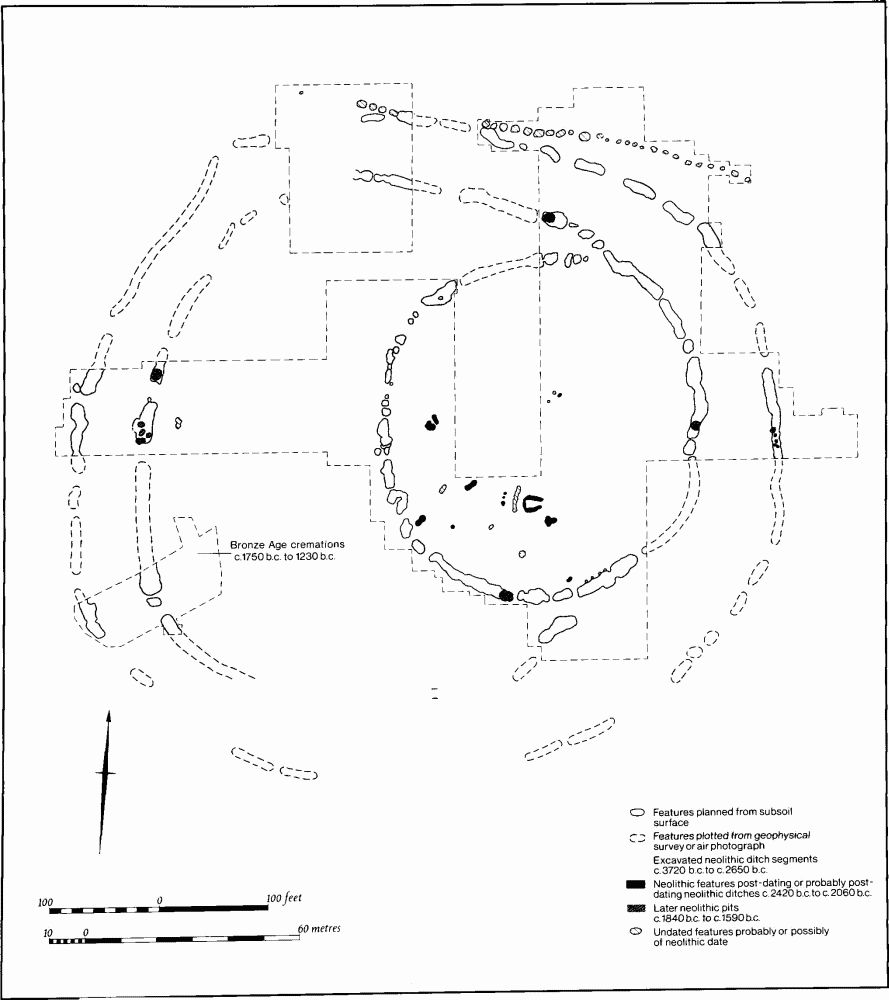

The density of known sites in Northampton and in parishes immediately beyond its boundaries, especially to the north and east, is high compared to Northamptonshire as a whole. Taken at face value this suggests that the area was a focus of settlement from at least the neolithic period onwards, an impression reinforced by the presence of a causewayed enclosure on Briar Hill (Hardingstone (7); Fig. 1). Nevertheless, the known distribution is almost certainly a distorted reflection of the actual pattern of settlement at any given period.

The evidence for prehistoric occupation is of several different types:

1. Chance finds. In built-up areas of the town where sites may be undetectable by other means objects discovered by chance constitute an important part of the record. Only the most distinctive types are likely to have been recognised.

2. Finds and sites discovered in the course of quarrying or construction work.

3. Information and material recovered in archaeological surveys prior to development or in field-walking.

4. Cropmarks. These have been noted within the area on land recently or still under cultivation. The majority cannot be dated but they certainly include features of neolithic and Bronze Age date.

5. Excavated sites.

Circumstances have especially favoured the recovery of all these types of evidence in the Northampton area. The comparatively large numbers of isolated finds of artefacts, especially stone and flint axes, may have as much to do with the high density of the population in recent times as with that of prehistoric peoples (cf. RCHM Archaeological Atlas, 2).

Large collections of worked flints from Duston (2) and around Hunsbury (Hardingstone (7)) were accumulated in the late 19th and early 20th centuries as a direct consequence of ironstone quarrying on two major multi-period sites. More recently, many lesser surface scatters have been located by field-walking. A programme of fieldwork and rescue excavation carried out since 1970 during the planned expansion of Northampton has led to the discovery of further mesolithic and neolithic sites and to the intensive investigation of the neolithic causewayed enclosure on Briar Hill (Hardingstone (7)).

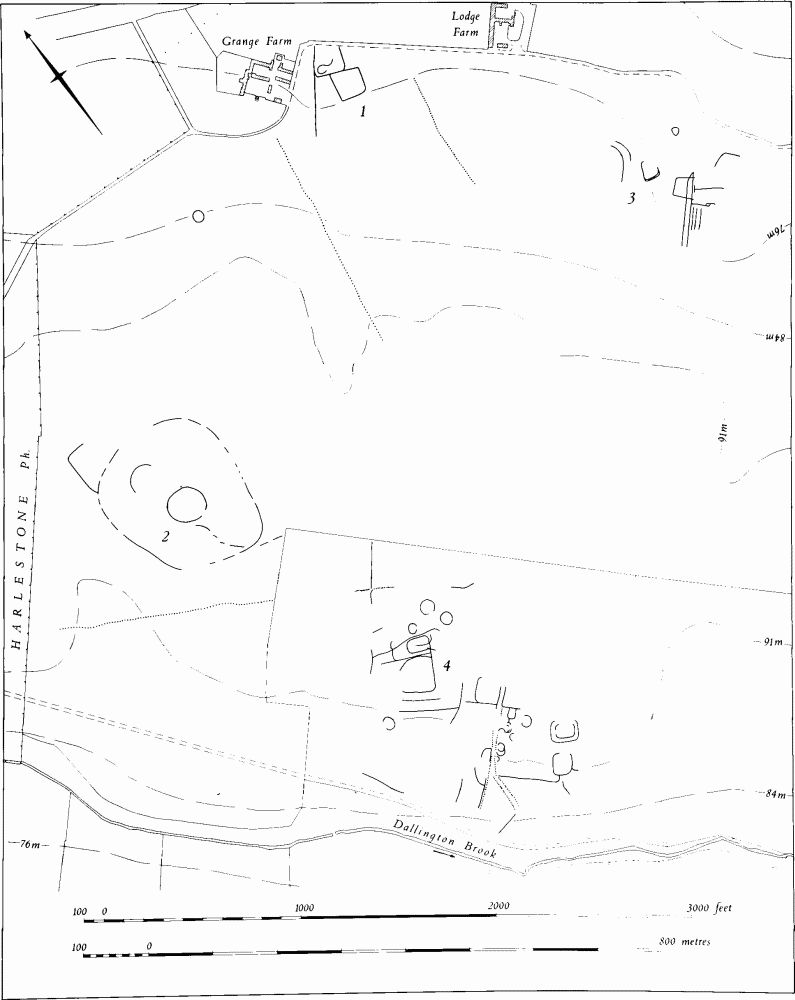

Cropmarks develop best on light, well-drained soils and in this region are generally confined to those overlying the Northampton Sands, Jurassic Limestone and gravels (RCHM Archaeological Atlas, map 4). Northampton itself and the extensive complexes of cropmarks around it, notably at Dallington (1–4) (Fig. 2; Plate 1) and the Bramptons (RCHM Northamptonshire III, 17ff), are on the largest outcrop of the Northampton Sands in the county and on gravels of the Nene valley. It is possible that these lighter soils were preferred by neolithic and Bronze Age farmers, but surface scatters of worked flints on heavier clay soils, as at Brafield-on-the-Green, south-east of the town (RCHM Northamptonshire II, 5ff), demonstrate the existence of a much more extensive pattern of settlement not detected by aerial photography.

Many of the recorded sites, including the majority of cropmarks, are not precisely dateable. None of the surface flint assemblages has yet been analysed in detail and only those which contain clearly diagnostic elements have been assigned here to specific periods. Nevertheless, in the light of the combined evidence, there can be no doubt that the Northampton area was densely settled in neolithic and Bronze Age times. What is in question is the significance of the apparent contrast between this and other parts of the county, where the range and intensity of fieldwork has been uneven.

Mesolithic Period (Map 4)

Most of the major surface collections of worked flints, including those from Duston and the Hunsbury area, contain some microliths, blades and cores of mesolithic type and demonstrate the presence of mesolithic hunter-gatherers along this part of the Nene valley. Only one site of the period has been excavated, at Chalk Lane (Northampton (1a)), where an assemblage of microliths, small blades and cores was found in possible association with a series of pits and hollows in the subsoil. None of these finds can be dated precisely, but the majority of the microliths are typologically early in form. In this respect they resemble the only other major collection of mesolithic flints from the county, that from Honey Hill, Elkington, about 20 km. to the north-west (Saville 1981). A few of the later geometric forms such as triangles, rhomboids and rods are present, however, in the Duston assemblage and in at least one of the surface collections from Chapel Brampton (RCHM Northamptonshire III, Chapel Brampton (4)).

Earlier Neolithic Period

The clearance and settlement of the area by neolithic farmers in the first half of the fifth millennium BC are indicated by three radiocarbon dates centred between 3700–3500 BC (calibrated to 4600–4400 BC) from the neolithic causewayed enclosure on Briar Hill (Figs. 1, 3; Hardingstone (7)). These dates apparently refer to the original construction of the earthwork, implying that by the mid fifth millennium the neolithic population of the area was sufficiently numerous, economically secure and well organised to undertake a communal project such as the construction of this large monument. It encompasses more than three hectares and required the initial expenditure of an estimated 6000–7000 man hours. Further radiocarbon dates, together with the stratigraphy of the ditch fills, indicate that the earthwork was maintained or periodically reinstated over a period of approximately 1000 years until c. 2700–2600 BC (calibrated to c. 3500–3250 BC). This span alone suggests the continuing importance of the site to the population of the area throughout the greater part of the early and middle neolithic period and, judging by the evidence recovered in excavation, the site probably had symbolic and ceremonial functions as well as being the scene of domestic activity. It does not seem to have been designed or used for defensive purposes. As a focal point in the neolithic landscape it may perhaps have served as an expression of social and territorial identity.

A second interrupted ditched enclosure, slightly larger in size, known only as a cropmark but probably also of neolithic date, is located at Dallington, 4.5 km. north of Briar Hill across the Nene valley (Fig. 2; Plate 1; Dallington (2)). The relationship between the two is uncertain and they may have served different functions within the same territory. Alternatively, they could have been the work of two different social groups between which the River Nene marked both a boundary and a meeting point. This would accord with Bradley's suggestion (1978, 103) that causewayed enclosures were often placed near the edges of territories.

No unenclosed settlements of this period have been identified with certainty but most of the principal known surface concentrations of worked flints could mark the locations of such sites. Most appear to include material of earlier neolithic type.

Fig. 1 Hardingstone (7) Briar Hill neolithic causewayed enclosure.

Fig. 2 Dallington (1) Enclosures, pit alignments, ring ditch; (2) Causewayed enclosure (?), henge (?), pit alignments; (3) Enclosures, trackway (?); (4) Enclosures, ring ditches, pit alignments, trackways (?).

The exact provenance of the flints from the Hunsbury area was rarely recorded, but many were probably collected from the vicinity of the Briar Hill site and the fields to the south of it. The very large collection from Duston (2) presumably marks an important settlement on the north side of the River Nene, immediately opposite Briar Hill and lying between it and the Dallington site. Other, apparently large, settlements lay further north of the town (RCHM Northamptonshire III, Chapel Brampton (1, 4, 9, 11), Brixworth (1–11)). The site at Kislingbury (3) and the finds in the area of Weston Favell (fiche, p.413) and Great and Little Billing (fiche pp. 213, 225) may mark the locations of smaller settlements to the west and east of Northampton, as may those at Little Houghton and Brafield-on-the-Green to the south-east (RCHM Northamptonshire II, 5ff, 85ff). Some of the worked flints excavated as residual finds on various sites in the town centre (Northampton (1b, c)) could also be of this period and indicate former settlements there.

No earlier neolithic burials are known other than a cremation interred in one of the ditch segments at Briar Hill and in the acidic soils of the Northampton Sands it is unlikely that inhumations unmarked by a monument would have survived in recognisable form. A long mound at Upton may possibly be a neolithic long barrow (Upton (2)).

Later Neolithic to Early Bronze Age Period (Map 4)

Archaeological and environmental evidence found throughout Britain indicates that some kind of disruption or change in social and economic life occurred in the mid third millennium BC (the second half of the fourth millenium BC) (Whittle 1978; Bradley 1978, 105ff). Such a change can be detected on the Briar Hill site where, following the final recutting of the enclosure ditches towards the end of the earlier neolithic period (c. 2700–2600 BC), activity continued, or was resumed, after a different fashion (Fig. 1). This is evidenced by a series of pits and structures within the southern half of the inner enclosure, without parallel in the earlier phases and dated between 2400 and 2000 BC (3200–2500 BC).

A final phase of use, marked by the digging of pits into the then silted ditches and associated with later neolithic Mortlake and Fengate impressed wares and Beaker pottery, lasted until c. 1600 BC (c. 2070 BC). At Dallington a large ring ditch with possible single entrance within the interrupted ditched enclosure could be a small 'henge' monument (Fig. 2; Plate 1; Dallington (2)).

Elsewhere, slight evidence of settlement sites has been found. In Chalk Lane in Northampton (Northampton (1a)), flint implements of later neolithic type were associated with pottery including Beaker sherds; at Weston Favell a pit contained Grooved Ware sherds and flints (Weston Favell (2)). A later neolithic occupation site on the gravels south of the River Nene at Ecton, just east of Northampton, should also be noted (RCHM Northamptonshire II, Ecton (1)). Flints and other artefacts of later neolithic and early Bronze Age type from Duston and other major multi-period surface collections already mentioned indicate that there was no marked shift in the pattern of settlement.

No fields or other enclosures of this period have yet been identified at Northampton but it is possible that some of the cropmarks here include such remains, particularly in view of the fact that late neolithic ditched field systems have now been discovered at Fengate near Peterborough (Pryor 1978), and that some pit alignments have been demonstrated to be of similar date (Harding 1981, 115ff; Miket 1981).

The Bronze Age (Map 4)

The later neolithic and early Bronze Age period in Britain was essentially one of cultural continuity, but some degree of social change is implied by events such as the ultimate abandonment of the Briar Hill enclosure. Most of the finds which can with certainty be dated to the early and middle Bronze Age in the district are associated with graves. On the other hand, many of the presumed settlement sites marked by concentrations of worked flints probably continued to be occupied and some cropmark enclosures in the same areas could be contemporary. Firm evidence for later Bronze Age occupation is, however, very sparse indeed.

Early to middle Bronze Age finds with probable funerary associations include a small collared urn found in a hollow in the subsoil at St. Peter's Street (fiche p. 322). This was possibly an accessory vessel from a cremation burial, disturbed by later activity. The curving, flat-bottomed ditch excavated on St. Peter's Street approximately 40 m. west of the urn (Northampton (1c)) could perhaps have been part of a Bronze Age ring ditch. Other collared urns have been recorded a few miles away at Brixworth (RCHM Northamptonshire III, 27f). Two 'pygmy cups' from Hunsbury may be of similar date (fiche p. 273).

A flat cemetery, probably slightly later, was found on the west side of the Briar Hill enclosure (Hardingstone (7)), although the siting itself could be coincidental. It consisted of up to 25 cremation burials in shallow pits (Fig. 1). One of four cremations contained in badly decayed and damaged bucket-shaped urns gave a date of 1230 ± 70 BC (c. 1500 BC) which compares closely with the date for the similar cemetery excavated north of the river at Chapel Brampton (RCHM Northamptonshire III, Chapel Brampton (10)).

A number of possible round barrow sites include both visible mounds, such as the one at Upton (Upton (2)) and the 'tumuli' recorded in 1904 at Duston (Duston (3)), and ring ditches as at Abington and Little Billing (Abington (1), Little Billing (2)). These must be seen in relation to the barrows and possible barrow sites on the gravels further down the Nene valley to the east at Ecton, Earls Barton and Grendon (RCHM Northamptonshire II, Ecton (6–8), Earls Barton (2), Grendon (3)).

No early Bronze Age metalwork has been recorded in the Northampton area, but a few isolated bronze tools suggest middle Bronze Age activity. They include a flanged axe from Billing (fiche p. 213) and two side-looped spearheads from Northampton (fiche p. 322) and Upton (fiche p. 401) respectively which are probably roughly contemporary with the flat cemetery on Briar Hill.

No settlements or graves of the later Bronze Age are known in this area. Surface flint scatters cannot be used as a method of locating sites of this period and pottery, even if identifiable, is not likely to have survived ploughing. A small quantity of possibly late Bronze Age sherds from Hunsbury (Hardingstone (14)) perhaps suggests that occupation of the hilltop may have begun during this time. A later Bronze Age presence is indicated by bronze implements such as the unlooped palstave from within Northampton (fiche p. 322) and the socketed axe from Dallington (fiche p. 240).

The Iron Age (Map 5)

For the Iron age the settlement pattern in the Upper Nene basin is rather more intelligible, since although casual finds of material are less widespread than the flint scatters and isolated flints of earlier periods, several sites have been excavated. The evidence from these excavations, from air photographs and from casual finds shows that the area was fairly densely populated by small, perhaps single-family, communities. The most dominant feature, and a focus for the region, is Hunsbury, one of only four possible hill forts in the whole county (Figs. 3, 4; Plate 2; Hardingstone (14)). This hill fort, covering some 1.6 hectares, stands on a prominent hill that affords extensive views over the whole of the Upper Nene valley. It consists of a roughly circular area bounded by an inner rampart and a ditch, with an outer rampart on the north, north-east and north-west sides; an initial timber-laced rampart was replaced by one of glacis form. The interior was largely quarried for ironstone in the late 19th century, at which time were recovered the finds of metal, pottery, glass and bone for which the site is notable, in particular, Hunsbury gave its name to the florid curvilinear style of decoration found on globular bowls of the later Iron Age. The pottery as a whole suggests a limited chronology. Although the presence of vessels decorated with applied cordons, extensive finger-tipping and incised geometric decoration may indicate some minor late Bronze Age or early Iron Age activity here, it is probably more reasonable to regard it as broadly contemporary with the bulk of the pottery from the site which is dated no earlier than the 5th century BC and which suggests that the hill fort itself was first constructed about that time.

Fig. 3 Hardingstone (6) Enclosure; (7) Neolithic causewayed enclosure; (8) Pit alignment; (9) Iron Age settlement; (10) Iron Age enclosure; (11) Pit alignment; (12) Iron Age settlement; (13) Iron Age ditch; (14) Iron Age hill fort; (15) Roman kiln; (16) Roman settlement and kiln; (17, 19) Roman settlements; (21, 22) Saxon settlements. WOOTTON (4) Ring ditches and enclosures; (8) Roman villa.

Other pre-Belgic Iron Age settlements are altogether on a smaller scale and lack the apparent wealth of Hunsbury. Occupation remains have been excavated at Blackthorn (Great Billing (4)), Moulton Park (1), Briar Hill (Fig. 3; Hardingstone (9)), Hardingstone (4a) and Upton (3). Great Billing (4) is a particularly fine example of a double-ditched enclosure of single-family size (fiche Fig. 21). It had an internal area of 0.1 hectare with an oval house in the south-east corner and was occupied for some time within the period c. 200 BC to c. AD 25. The site at Moulton Park is important for its situation on Boulder Clay (cf. Draughton, some 11 kilometres to the north: Grimes 1961, 21–23; RCHM Northamptonshire III, Draughton (8)); it tends to confirm that settlement was not entirely confined to the gravel terraces and well-drained sandy soils (cf. RCHM Archaeological Atlas, 4f). Some 3rd to 2nd-century BC pottery was found at Upton and a 2nd to 1st-century group at Hardingstone village. Similar Iron Age pottery was associated with ditched enclosures on the site of the neolithic causewayed camp at Briar Hill (Hardingstone (7)), but the small quantity from the square double-ditched enclosure some 150 metres to the south-east (Hardingstone (10); Plate 1)) could not be precisely dated. Casual finds come from several other locations (see Map 5) and presumably some of the undated cropmarks also belong to this period. A single sherd of late Bronze Age to early Iron Age pottery is reported from Weston Favell (fiche p. 413), but the lack of early Iron Age material is particularly noticeable. The true significance of this is not clear, but it would appear that elsewhere in the county finds of such material are also uncommon (RCHM Northamptonshire II, xiii).

At the end of the 1st century BC or the beginning of the 1st century AD the Nene valley came under Belgic influence and the distribution of British coins suggests that it fell within Catuvellaunian territory; the boundary between the Catuvellauni and the more northerly Coritani seems to have lain somewhere in the uplands between the rivers Nene and Welland. Belgic pottery has been found in several places, the most important collections having come from Hardingstone (4a), Moulton Park (1) and Duston (5). At both Hardingstone and Moulton Park there appears to have been increased activity on sites that were already occupied, but no pre-Belgic Iron Age material has so far been recovered from Duston. The chronology and indeed the significance of Belgic culture in the region is difficult to assess. Belgic pottery forms continued throughout most of the 1st century AD (cf. e.g. the Camp Hill kilns (Hardingstone (15, 16))) and it could even be argued that these new forms did not penetrate the area until the Roman conquest; this is improbable, however, since late Augustan Gallo-Belgic wares are known at Leicester (pers. comm. V. Rigby). Although the Hardingstone and Moulton Park pottery, and most of that from Duston, is fairly finely made and typical of the middle of the 1st century AD, two sherds from Duston are similar to material from Wheathampstead (Wheeler and Wheeler 1936, 194ff) and, more locally, from Irchester (Hall and Nickerson 1968, 80) and Rushden, and probably date to before 1 BC. While the few earlier Belgic sherds from Northamptonshire are probably best interpreted as outliers from the main area of Belgic influence to the south, the evidence of the British coins from Duston certainly suggests later pre-Conquest Belgic occupation. At least 20 such coins have been found: Catuvellaunian coins predominate, with five of Tasciovanus (c. 20 BC–AD 10) and at least nine of Cunobelinus (c. AD 10–40), together with two of Andoco (c. AD 5–15, apparently ruler of an unnamed tribe on their north-west border); four Dobunnic coins were also found. Evidence from hoards in East Anglia indicates that Icenian coinage continued in use up to AD 60 and perhaps beyond but it is suggested that this may have been due to the special conditions prevailing in the East Anglian area with the Iceni as a client kingdom (Allen 1970, 15–19). It seems unreasonable to argue that all the Duston coinage, ranging back to Tasciovanus, was deposited after AD 43, and it would appear most likely that a settlement was beginning to grow up there by about AD 25. The absence of Belgic material from Hunsbury, suggesting its abandonment by about the same time, supports the idea that a new focus for the Upper Nene basin was growing up, most probably at Duston.

Fig. 4 Hardingstone (14) Hunsbury hill fort.

The distribution of British coinage in Northamptonshire is of some interest in this argument (cf. Allen 1961; Gunstone 1971; Haselgrove 1978 and some more recent discoveries). Of 70 or so coins found at least 20 are from Duston, one from St. James End, and three from Northampton, these last all being of the earlier Gallo-Belgic type. Although the extensive ironstone quarrying may have provided an increased chance of discovering such coins, Duston does seem to be marked as a centre of some importance. Although the sample size is very small and details of provenance are often very imprecise, it may also be significant that many of the find-spots where more than one coin has been recorded (Duston at least 20, Irchester 2, Kettering 3, Oundle 8, Thrapston 2, Towcester 2) were located in or near Romano-British urban centres. Such continuity of nucleated and semi-nucleated settlements from the Iron Age to the Roman period has also been noted in Lincolnshire (May 1976) and Essex (Rodwell 1976, 325). Caution must be exercised, and further research is clearly necessary, but the limited evidence appears to suggest that there was perhaps some move towards nucleated settlement in the first half of the 1st century AD and that this developed further with the arrival of the Roman army.

The Roman Period (Map 5)

Northamptonshire has never been regarded as one of the most prosperous areas of Roman Britain. It does not include a civitas capital or major urban centre and few high quality villas, such as are found in the Cotswolds, the Chilterns and elsewhere (cf. Rivet. 1969, 213, Fig. 5.7), have been located in the area. Yet extensive fieldwork, particularly in recent years, has revealed that the overall settlement pattern in this area was extremely dense and this is evident in the region around Northampton: no less than 31 sites are here recorded, as well as numerous individual find-spots.

The extent to which the Upper Nene valley was caught up in the initial Roman military advance after AD 43 and its influence on the development of settlement is not clear. It would seem reasonable to suppose that Duston may have been an element in the early network of forts, along with Bannaventa (RCHM Northamptonshire III, Norton (4)), Towcester (RCHM Northamptonshire IV, Towcester (3)) and Irchester (RCHM Northamptonshire II, Irchester (7)), but evidence for this has not yet been discovered at Bannaventa and Towcester and even at Irchester the argument relies on the alignment of the surviving earthworks and possible ditches identified on air photographs (RCHM Northamptonshire II, 91). Duston is similarly enigmatic and will probably remain so, since so much was destroyed during ironstone quarrying in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Finds recovered at that time and subsequently, however, throw some interesting light on the problem. There are no structures or artefacts to prove a military presence but at least 20 British coins suggest a pre-Conquest Belgic occupation (see Iron Age, above) and some brooches and Belgic-style pottery belong to the Conquest period. With or without such a military stimulus, a settlement grew up here in the 1st century AD.

The nature of this settlement is somewhat difficult to define. Occupation seems to have extended over at least 8 hectares and evidence of Romanised buildings was discovered both during the quarrying and by limited excavation in the 1970's. The fragmentary stone structures found to the south of the Weedon Road between 1974 and 1976, which appear to respect a road running roughly north-south across the site, seem to belong to the latter half of the 3rd century, with earlier occupation consisting of timber buildings associated with ditched enclosures. Whether this is typical of the whole of the settlement is uncertain, but it would appear to be consistent with the sequence in other lesser towns, such as Water Newton, Ancaster, Margidunum, Thorpe-by-Newark, Alcester, and Wanborough (Wacher 1978, 101ff). The settlement seems to have survived in some form into the 5th century, for the coin series includes examples of Arcadius and Honorius and two buckles of similar date have also been found.

Of the remaining sites in the Inventory area two can be classified as villas, from the evidence of hypocausts, mosaics and painted wall plaster, and also because of the size of the buildings. The site of the one at Moulton (1) is largely built over and it is known chiefly from finds made in the gardens of houses in the area. The other, at Hunsbury (fiche Fig. 38; Plate 3; Wootton (8)), is better known, as various small-scale excavations were carried out on the site between 1973 and 1981, but the details are as yet unpublished and any conclusions must be recognised as tentative. Timber features and boundary ditches, apparently of the 1st century AD, were replaced, probably in the 2nd century, by a rectangular block of stone-built rooms which was subsequently extended. Later still, probably in the 3rd or 4th century, the villa was further enlarged by the addition of a bath-house which was connected to the original building by a corridor.

The interdependence of urban and villa economies has been discussed (Rivet 1969, passim; Todd 1978, passim) and is demonstrated by the presence within a 10 kilometre radius of Duston of other villas: Wootton (8), Moulton (1), Gayton (RCHM Northamptonshire IV, Gayton (1)), Harpole (RCHM Northamptonshire IV, Harpole (6)), Stoke Bruerne (RCHM Northamptonshire IV, Stoke Bruerne (4)) and Hackleton (RCHM Northamptonshire II, Hackleton (11)). There are further possible villas at Harpole (RCHM Northamptonshire IV, Harpole (3)), Little Houghton (RCHM Northamptonshire II, Little Houghton (6)), Hackleton (RCHM Northamptonshire II, Hackleton (22)), Harlestone (RCHM Northamptonshire III, Harlestone (19)) and Kingsthorpe (5). Taken with the other evidence for settlement, this suggests a comparatively dynamic and prosperous economy in the Upper Nene basin and while villas are indeed found over the whole of Northamptonshire they do appear to have been mainly concentrated in the Nene valley.

Two smaller sites, perhaps best described as Romanised farms, have also been excavated at Thorplands (Plate 3; Moulton (2)) and Overstone (2). At both the evidence for Iron Age occupation is insubstantial and the first structural phase to be identified, dating to somewhere between the late 1st and mid 3rd century, was the construction of a circular timber building. Towards the end of the 3rd century timber buildings were replaced, again on both sites, by circular stone buildings. Enclosures of Roman date south of the Overstone farm (Great Billing (11)), probably demarcate the fields of the settlement. The proximity of the Thorplands farm to the villa at Moulton (700 metres south-west of it) has led to the suggestion that it may have formed a unit within a large complex controlled from Moulton, and the similarity of the structural sequences at Thorplands and Overstone might further hint that both were controlled by the same authority. The Moulton villa would then have acted as an estate centre, but this is no more than speculation.

Many small Romano-British rural sites, presumably similar to the Thorplands and Overstone farms, have been found either by fieldwork or during modern development, but precise evidence as to their nature is lacking. A concentration of sites and pottery finds in the north of Great Billing parish shows, in this area at least, a pattern of settlements at intervals of about 700 metres. Many of the cropmark sites noted on air photographs are likely to be of Roman date, but as yet the only ones to be securely identified as such are those to the south of Overstone farm (Great Billing (11)).

Evidence of industrial activity is limited to iron-working at Thorplands farm and a large number of pottery-producing sites of the 1st century AD. So far seven kiln sites have been identified in the Northampton area, at Abington (2), Dallington (5), Hardingstone (4a, 4b, 15, 16), and Weston Favell (6), and seven places with portable kiln furniture at Great Billing (9, 10), Great Houghton (4, 5, 7), Hardingstone (18) and Wootton (8). Similar establishments have been found elsewhere along the Upper Nene valley, their ubiquity and limited life-span leading to the suggestion that they were supplying the Roman army (Webster 1973, 2–3; Woods 1969, 9; 1974, 278).

The only known Roman road in the area is that running north-west from Duston to join Watling Street at Bannaventa, but a further road, running east from Duston through Northampton and along the north side of the Nene valley towards Irchester, has also been suggested (Williams 1979, 4). The distribution map of Roman finds (Map 5) strongly supports this, for there is a notable concentration of them along the line of Marefair-Gold Street and Billing Road. Surprisingly, there is as yet no evidence for any road running southwards from Duston.

The Saxon Period (Map 6)

There are considerable problems in defining the development of settlement patterns in the Saxon period in Northampton, as elsewhere, but the intensive work at the west end of the town, in the area around St. Peter's Church, has yielded most important results. A major middle Saxon palace complex has been uncovered and fairly extensive settlement remains relating to the late Saxon town have been investigated. All this, however, needs to be incorporated within a single framework. For the purposes of discussion, the Saxon period has been divided into early (c. AD 400–650), middle (c. AD 650–850) and late (c. AD 850–1066) phases.

Chronology presents a major problem. By far the most common artefact on early to middle Saxon sites in the area is black gritty pottery. This shows no variation in fabric or form over more than four centuries except for the stamped and decorated sherds which are identified as coming from pagan, early Saxon vessels of funerary type. Only about 30 such sherds, however, have been found outside the cemeteries themselves. Some greater chronological precision for the development sequence of the settlement on the site of Northampton itself has been provided by the Northampton sequence of radio-carbon dates allied to the relative stratigraphy of the excavated sites.

There is some limited evidence for continuity from the Roman period. The two late buckles and coins of Honorius and Arcadius from Duston have already been noted. It may also be relevant that the early Saxon cemetery at Duston (7), apparently the most extensive in the Upper Nene basin, lay immediately adjacent to, if not partly over, the Romano-British small town. The presumed location of the cemetery lies between the main settlement area of the town and a site where 4th-century ditches have been excavated. Furthermore, a Roman lead coffin was recovered from the middle of the cemetery in c. 1903. The date range of the grave goods lies mainly between AD 450 and 550 although there is some later material. Further evidence for continuity is provided by the discovery of eight early to middle Saxon sherds on the site of the Wootton Hill Farm villa (Wootton (8)). It should be noted that the nucleus of early to middle Saxon activity at Northampton itself lay astride the postulated Roman road from Duston to Irchester in an area where there is a scatter of sherds and coins of Roman date but no contemporary structural remains (see Maps 5, 6 and fiche p. 324).

The character of the early Saxon settlement, the precursor of the middle Saxon palace complex and late Saxon town, was in no way out of the ordinary. The excavated remains, lying on a ridge above the probably marshy valley of the Nene are typical only of a small rural site. Four simple sunken-featured buildings probably belonged to this period (Northampton (8, 38)) and some of the post-hole structures associated with the early to middle Saxon pottery were probably of a similar date.

Other settlement and cemetery sites were scattered over the Upper Nene basin and failed to respect directly earlier Romano-British sites although pottery found at Hunsbury suggests that the Iron Age hill fort was being reused at some time between 400 and 850. Remains of early Saxon cemeteries and burials have been found at Cow Meadow, St. Andrew's Hospital (Northampton (3, 4)) and Hardingstone (23, 24) and traces of domestic occupation have been excavated at Hardingstone (21) and Upton (5) and early to middle Saxon pottery has been recovered at Hardingstone (22) and Weston Favell (8). While not individually impressive, taken together the sites indicate more intensive settlement than over the county as a whole. This apparent distribution may partly be a result of development activity in the area from the 19th century onwards and the intensive archaeological study of the last decade but it also seems to demonstrate that the Upper Nene basin was a continuing focus for settlement after the fall of Roman Britain.

Definite evidence for middle Saxon activity outside Northampton itself has not been found but the few sites where either the pottery assemblages lack distinctively early Saxon wares or which for other reasons can only be assigned to the general period AD 400–850 (e.g. Hardingstone (22) and Weston Favell (8)) may be middle as opposed to early Saxon in date. There is, however, a total absence of middle Saxon Christian cemeteries, a phenomenon paralleled in many other places. Negative evidence must be treated with caution and indeed the extent to which rights of burial and the location of cemeteries were formally determined at this time is little understood but it is possible that cemeteries of this date should be sought on the sites of later burial grounds which lie within the medieval and modern villages. It may well be that the framework for the modern settlement pattern was beginning to be established at some time during the middle Saxon period. Indeed, late Saxon pottery has not been found outside Northampton itself, tending to confirm that modern villages cover settlements of that date.

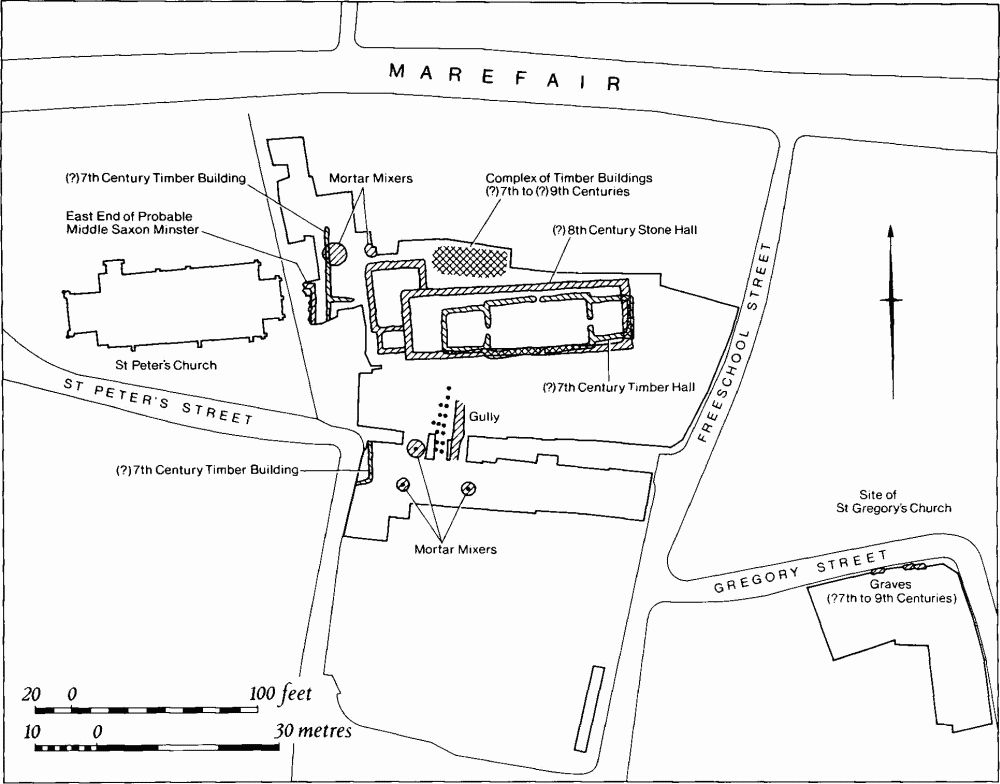

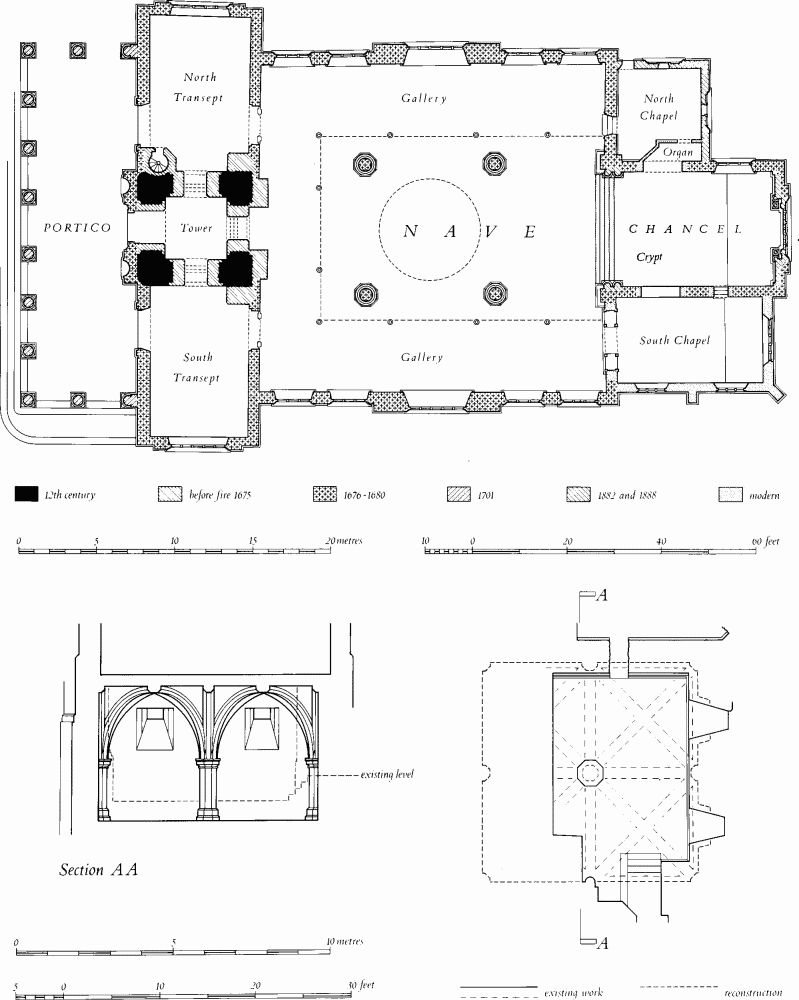

Extensive remains of the middle Saxon period have, however, been found in the area around St. Peter's Church, Northampton (Fig. 5; Frontispiece; Plate 4). Probably in the later 7th century a large timber hall was erected (Northampton (8)). This hall measured, to the centre lines of its wall trenches, c. 29.4 metres (96.4 feet) by 8.35 metres (27.4 feet) and comprised a rectangular unit c. 16.7 metres (54.8 feet) by 8.35 metres (27.4 feet) with central opposing doorways in the long sides and attached annexes 6.35 metres (20.8 feet) square at each end. The unit of measure in laying out the structure resembled very closely the modern foot and it would appear that the building was laid out as a double square 54 'feet' by 27 'feet' with 21 'foot' square annexes at each end. Posts had been set in continuous trenches c. 3 feet deep and 3 feet across. Such massive foundation trenches were needed to support the roof which apparently covered the building in a single span. The form of construction was highly sophisticated with accurately surveyed pairs of posts matching each other across the hall and there is some evidence to suggest that the main hall was divided into nine bays 6 'feet' in length. The site was badly disturbed by later pits and few contemporary artefacts survived. A further large timber structure at least 16 metres by 8.75 metres and with foundation trenches c. 0.75 metres deep lay to the west. Other timber, mainly post-in-trench, buildings on a much more modest scale were located immediately to the north and south-west. There may have been further contemporary structures at Black Lion Hill and in Chalk Lane (Northampton (46, 38)).

The large timber hall by its very nature marks the site out as a major centre of its period and indeed in plan the building most resembles Edwin's royal hall at Yeavering in Northumbria (Hope-Taylor 1977), the postulated palace at Atcham near Shrewsbury (St Joseph 1975, 293–4) and a structure within an impressive complex at Malmesbury in Wiltshire (Hampton 1981, 316–21).

At about the beginning of the 8th century the large timber hall was replaced by an even more massive one of stone. Initially this comprised a large rectangle measuring 37.5 metres by 11.5 metres with walls 1.2 metres wide and foundations 0.6 metres deep. Subsequently, but again in the first half of the 8th century, two smaller rooms were attached to the west end of the building, thereby increasing its length to 43.5 metres. Only short lengths of walls survived, most of the plan being represented by robber trenches; floor levels had similarly been eroded away.

Fig. 5 Northampton (8) Saxon Palace Complex.

To the west of this building the extreme east end of a further stone structure, which extended back under the present St. Peter's Church, was uncovered. The east wall of the structure measured 6.5 metres north to south and was 0.8 metres thick. Two courses of wall survived showing that it had been rendered on its inner face. It is thought that the building was an antecedent of the present church contemporary with the large stone hall.

Associated with the two buildings were five mechanical mortar mixers (Plate 4). These comprised bowls between 2 metres and 3 metres in diameter, generally cut down into the ground but in one case raised above it. Mortar was mixed in them by paddles suspended from a beam rotating round a central pivot in a horizontal plane. Such mixers have been found, generally on high status sites, in Switzerland, West Germany, Poland and Belgium (Gutscher 1981) and a single example has been excavated at Monk wearmouth in Northumberland (Cramp 1969, 32–6 and pl. 3).

Some 50 metres to the east of the large stone hall, four orientated burials were excavated in Gregory Street (Northampton (42)). Radio-carbon dates suggest that these also belonged to the middle Saxon period. The site lay 15 metres south of the site of St. Gregory's Church, first recorded in the 12th century (Northampton (27)) but the early dedication and the presence of the graves suggest that there may have been a church or chapel on the site contemporary with the large stone hall. Other timber structures associated with the early to middle Saxon pottery (cf. Northampton (45, 46)) may have been contemporary with the 8th-century complex.

Archaeologically the stone hall is totally without parallel in England although similar buildings presumably existed at major royal centres (cf. Williams forthcoming). The considerable medieval and later disturbance and erosion of the middle Saxon levels at Northampton demonstrate that it is likely that such complexes, where they existed in towns with intensive medieval and later development, may have been almost totally destroyed; indeed they will probably only be recognised where a sufficiently large area is studied. On the Continent similar structures have been recognised in the Carolingian palace complexes at Paderborn and Frankfurt in West Germany and the Lindenhof at Zurich in Switzerland (see Williams forthcoming). Paderborn and Frankfurt are particularly relevant in that the complexes also contain a major church and thus provide a direct parallel to Northampton. On all the continental palace sites, including such lavish and resplendent examples as Aachen and Ingelheim, the hall is a main feature of the architectural composition.

What then was the precise status of the Northampton complex whose main elements were a large stone hall, possibly two church sites and further ancillary buildings? The name 'Hamtun', Northampton's earliest designation, is regarded as signifying a central residence as contrasted with outlying and dependent holdings (Gover et al 1933, xvii-xviii). This possible estate structure is further evidenced by the local ecclesiastical organisation. St. Peter's Church, at the centre of Northampton archdeaconry, was a mother church with dependencies at Kingsthorpe up to 1850 and Upton up to modern times (Sergeantson 1904, passim; Williams 1982). The manors of Kingsthorpe and Upton were in the King's hands at the time of the Domesday Inquest and subsequently in the medieval period were hundredal manors for Spelhoe and Nobottle Grove hundreds respectively (Cam 1963, 67, 69). The evidence seems to indicate the fragmentation of a substantial middle Saxon royal estate and minster organisation centred on Northampton, elements of which survived for some considerable time. At the caput of this estate were to be found the royal hall or 'palace' and the seat of ecclesiastical authority, the old minster church of St. Peter.

The scale and precision of the successive timber and stone halls, the lack of comparable examples in England and the continental parallels mark Northampton out as a major seat of authority at least as early as the later 7th century. It is tempting to look further back and see in the presence of the Saxon palaces the continuation of a Romano-British area of authority based on Duston. Although areas of influence may well have changed through time this would seem to give Roman Duston a rather more formal status than the excavated remains might suggest.

The geographical extent of Northampton's influence in the middle Saxon period is also a matter of some uncertainty. With the evidence now available the shire town of the late Saxon and medieval periods can readily be identified as the progeny of the earlier estate centre; Domesday Book and other sources, however, show that places such as King's Sutton, Fawsley, Rothwell and Finedon were all heads of substantial royal estates and traces of minster organisations for King's Sutton and Fawsley have survived (Williams forthcoming). It seems unlikely that there were complexes similar to that at Northampton at all these places but if there were not then it must be accepted that Northampton had assumed a pre-eminence within the surrounding countryside at a relatively early date in the Saxon period. In the absence of a Romano-British civitas capital or major centre, unless the interpretation of Duston is incorrect, this is particularly significant.

During the recognisable history of the palace complex Northampton appears to have been within Mercia. Originally within the area defined as Outer Mercia or Middle Anglia it seems to have been subsumed by Penda into Mercia in the 7th century and to have remained under Mercian control. There are some allusions to a connection with East Anglia, in particular the presence at St. Peter's Church of a cult of St. Ragener, the nephew of Edmund of East Anglia, king and martyr, but there is no evidence to suggest that territorially Northampton was ever under East Anglian control. It is most likely that the remains of Ragener were translated to Northampton in the 10th century (Williams forthcoming).

Towards the end of the 9th century Northampton was taken over by the Danish armies and incorporated within the Danelaw. It is probably about this time, and almost certainly in the period 875–975, that the palace fell into disrepair and was destroyed and that the walls were subsequently robbed. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle for 913 records 'the [Danish] army from Northampton' and in 917 it relates how 'Earl Thurferth and the holds submitted to him [Edward] and so did all the army which belonged to Northampton as far north as the Welland' (Whitelock 1965, 62, 66). This seems to mark Northampton out as a major administrative centre within the Danelaw and the 'heres gemote', present in Northampton at the time of Aethelred II, can be seen as a survival of a Danish legal or administrative system (CS: 1130). The presence, however, in the medieval period in Northampton of a town court known by the Scandinavian name 'hustings' is not necessarily informative, for King Richard's charter to Northampton in 1189, in which the right to hold the court of hustings was formally granted (Markham 1898, 25–29), was clearly copying the London charter of 1155 (Ballard 1913, cxliii and passim) and the court itself or its name may have been derived from this London model and been introduced into Northampton at a comparatively late date. There are a few place names with Scandinavian elements in the hundreds of Spelhoe, Wymersley and Nobottle Grove, which surround Northampton, but nothing to suggest strong Scandinavianisation. This is in contrast to those hundreds further to the north-east where such influence is strong. The pattern of the evidence probably reflects Northampton's frontier position on the boundary of the Danelaw (Gover et al 1933, xxi-xxix).

The archaeological evidence is similarly difficult to interpret. A total of ten St. Edmund Memorial pennies found on the site of Northampton, several in well-stratified contexts, suggests that some at least of the earliest late Saxon levels belong to the period before its capture by Edward the Elder, although to distinguish between Danish and Saxon material culture is virtually impossible at the present time.

It is possible, however, to see a general upsurge in economic activity in Northampton during the late Saxon period. Pottery is far more prolific. Local wares predominate with St. Neots ware and Northampton ware most common; the former was perhaps made in the immediate vicinity, and the kiln for the latter has been identified in Horsemarket (Northampton (43)). Smaller quantities of material were imported from Stamford, Leicester, East Anglia and continental Europe. There is considerable evidence for metal-working with iron-smelting and/or smithing being practised in St. Peter's Street, Gregory Street, Marefair and Chalk Lane (Northampton (51, 42, 45, 38)), copper alloy working in Marefair and probably Chalk Lane (Northampton (45, 38)) and silver-working in Chalk Lane and Marefair (Northampton (38, 45)). Antler and bone-working debris has been found in St. Peter's Street and Chalk Lane (Northampton (51, 38)) and antler and bone tools themselves and other artefacts indicate textile manufacture. Evidence of flax-retting was found at St. James' Square (Northampton (50)). Contact with continental Europe is further evidenced by hones from Eidsborg, Norway. More local trading in perishable foodstuffs is demonstrated by the identification of a few sea-water fish bones.

Extensive structural remains have also been found. In St. Peter's Street the fragmentary traces of a number of post-hole structures and five small sunken-featured buildings were discovered adjacent to a rough metalled lane which perhaps meandered across the site. Metal-working was concentrated towards the west (Northampton (51)). In Chalk Lane a complex was excavated which comprised a building, a yard area, a concentration of pits and land given over to agricultural purposes. In its initial phase the building consisted of a hall structure based on six posts with a small square cellar at one end and a fairly deep sunken-featured building outside at the other end. These were replaced by a further structure built with close-set posts (Northampton (38)). Two adjacent post-hole buildings were uncovered in Gregory Street (Northampton (42)). Less complete structural traces have been found in Marefair (Northampton (46)).

Fig. 6 Streets in Northampton.

The evidence from the individual sites needs to be related to the overall form of the late Saxon settlement. Alderman Frank Lee in a seminal paper published in 1954 (Lee 1954) examined the topography of Northampton's street plan which at the time, albeit with additions, largely preserved the medieval one. Subsequently, however, redevelopment has destroyed essential elements of medieval topography and these changes can be seen by comparing the series of maps up to 1847 reproduced in this volume (Fig. 8; Plates 7, 9, 10, 11; see also OS 1:2500, 1964) with the present town plan represented in Fig. 6. Lee argued that Marefair and Gold Street on the one hand and Horsemarket and Horseshoe Street on the other formed the main east-west and north-south axial streets of the late Saxon town. The northern and eastern extent of the town was defined by parallel lines of streets comprising Scarletwell Street, Bearward Street, the Drapery and Bridge Street on the one hand and Bath Street, Silver Street, College Street and Kingswell Street on the other. Between these lines of streets ran the late Saxon defences (Northampton (6)), presumably comprising an earthen bank and ditch. These postulated defences have been investigated in a number of places but definite archaeological confirmation of Lee's hypothesis is not yet forthcoming. To the south and west the river probably formed the main defensive barrier.

Lee also suggested that the Marehold and All Saints originated as markets at the north and east gates respectively and noted how the roads radiated outwards from the gates. The original route to Leicester went due north and its line is still preserved in Semilong (cf. Wood and Law's map, Plate 11) but it was subsequently diverted with the establishment or expansion of St. Andrew's Priory. The road leaving the north gate to the north-east led across Northampton Heath, subsequently known as the Race Course, towards Kettering. At the east gate the roads diverged to Wellingborough and Kettering, Billing and Bedford. The Saxon crossing of the Nene was due south of and continued the line of Horseshoe Street. It can then be identified in Far Cotton as the Towcester Road.

Lee's ideas are fundamental to the understanding of Northampton's topography but the major problem remains as to the date when the defensive line was established. The most probable alternatives are during the time of the Danish occupation of Northampton, under Edward the Elder during the establishment of his burghal network, or later in the Saxon period. Certainly little late Saxon material has been found outside the defensive circuit. Four sherds of late Saxon wares have been recorded from watching briefs in Bridge Street (one sherd), the Drapery (two sherds) and George Row (one sherd) (see fiche p. 384–7) and excavations in Derngate 300 metres east of the presumed east gate have produced a further 14 sherds of late Saxon type but which are not necessarily pre-Conquest in date (Northampton (39); see also Shaw forthcoming b).

The late Saxon defended area would appear to have covered about 24 hectares and to have been divided into quadrants by the north-south and east-west axial streets. These continued as major routeways beyond the line of the defences and there is no reason to see them as the skeleton of a planned grid for the town. Other streets lying roughly parallel to the axial streets such as Castle Street, King Street and St. Katherine's Street are more simply explained as roughly respecting the lines established by the axial streets and the defences rather than as further elements of a planned street lay-out. Within the overall framework formed by the streets, individual properties and structures, while again basically respecting the main axes of the town, are fairly irregularly disposed, perhaps in family or economic units.

The precise role of the church in the late Saxon borough is difficult to determine. In the reign of Edward the Confessor St. Peter's again appears as a minster church whose priest Bruning 'multas ... inter provinciam regebat ecclesias' (Horstmann 1901, 727). Presumably the church had either survived the Danish occupation or been reconstituted early in the 10th century and the same development pattern perhaps applied to St. Gregory's. During the excavation of St. Mary's in 1962 (Northampton (28)) no evidence was found to suggest a Saxon origin but there may possibly have been a pre-Conquest church or chapel on the site of St. Katherine's (Williams 1982b, 82). All Saints' perhaps originated in the 10th or 11th century as a church in the market place at the east gate.

Certainly during the 10th century Northampton changed its character and assumed urban characteristics. It had a mint at least from the time of Eadwig (Blunt and Dolley 1971) and in 1010 was referred to as a port (Whitelock 1965, 90). It may well be that the impetus towards urban status was provided by the Danes whose trading instincts have been demonstrated elsewhere. This development, however, can now be seen to have been less dramatic in that middle Saxon Northampton, the seat of royal and ecclesiastical authority, probably attracted further administrative and trading functions and was presumably a rallying point in times of unrest. The step towards becoming a town proper was but a small one.

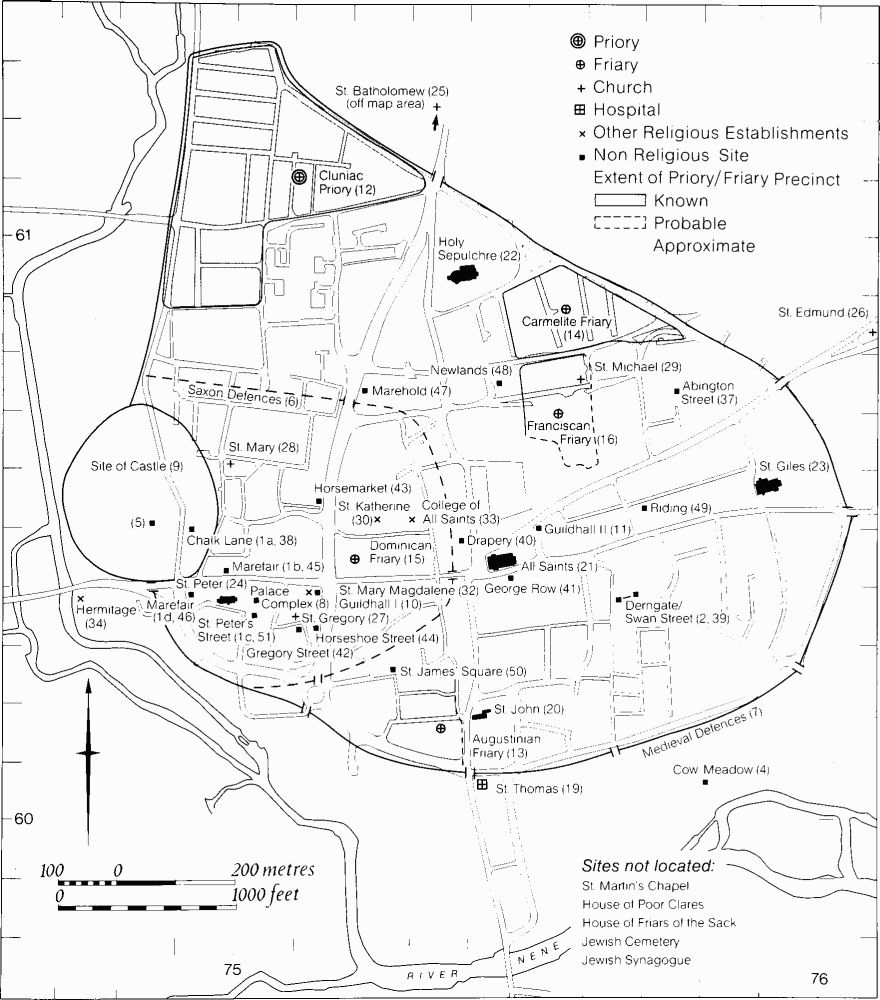

Medieval Northampton (Maps 6, 7)

From 1066 to 1200

The period from the Norman Conquest up to the end of the 12th century was one of consolidation, expansion and prosperity for Northampton. During this time it grew from a well-established yet middling shire town into one of the great centres of England. In Domesday Book between 291 and 301 houses and 36 waste plots are listed (DB, f. 219a). Russell's estimate of 1032 for the population (1948, 51) is probably too low and a figure nearer 1500 is more likely (cf. Baker 1976, 45). A fairly wide variety of tenants in chief are recorded, including such notable people as the king was the Mortain, the Bishop of Coutances, the Countess Judith and William Peverel, but the king was the main landowner with 87 houses and 13 waste plots. Northampton's farm at £30 10s. was some way below the £100 of York and Lincoln and the £300 of London but was roughly comparable with those of towns such as Chichester, Derby, Guildford, Ipswich, Lewes, Nottingham, Torksey and Worcester (Tait 1936, 154, 184). In a ranking based on these farms Northampton lay somewhere between twentieth and thirtieth. By 1130 the town's farm had more than trebled to £100 (Tait 1936, 156) and it was further raised to £120 in 1184 (Tait 1936, 175, 184). At the end of the 12th century the farm was only exceeded by those of London, Lincoln, Winchester and Dunwich (Biddle 1976, 500). Further evidence of the prosperity of Northampton at this time is provided by the aids and tallages rendered to the king between 1158 and 1214. In rankings based on these figures Northampton never fell below seventh position; in 1172 it was third to London and Lincoln and in 1176/7 it was second only to London (ibid, 501).

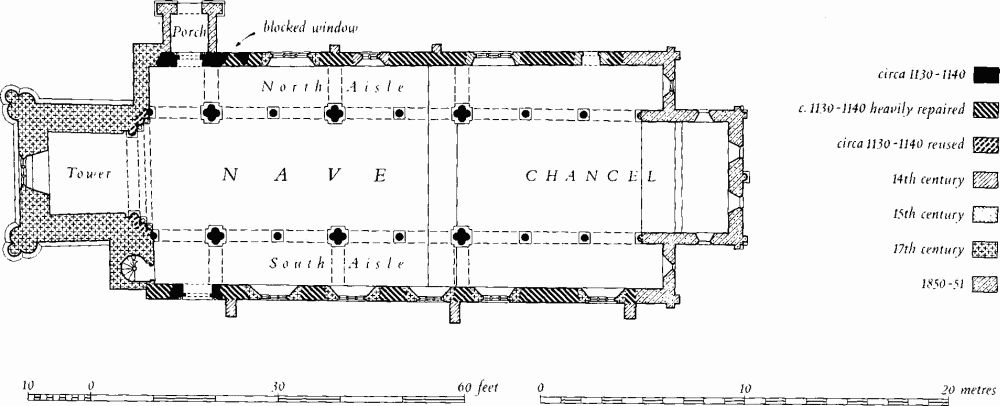

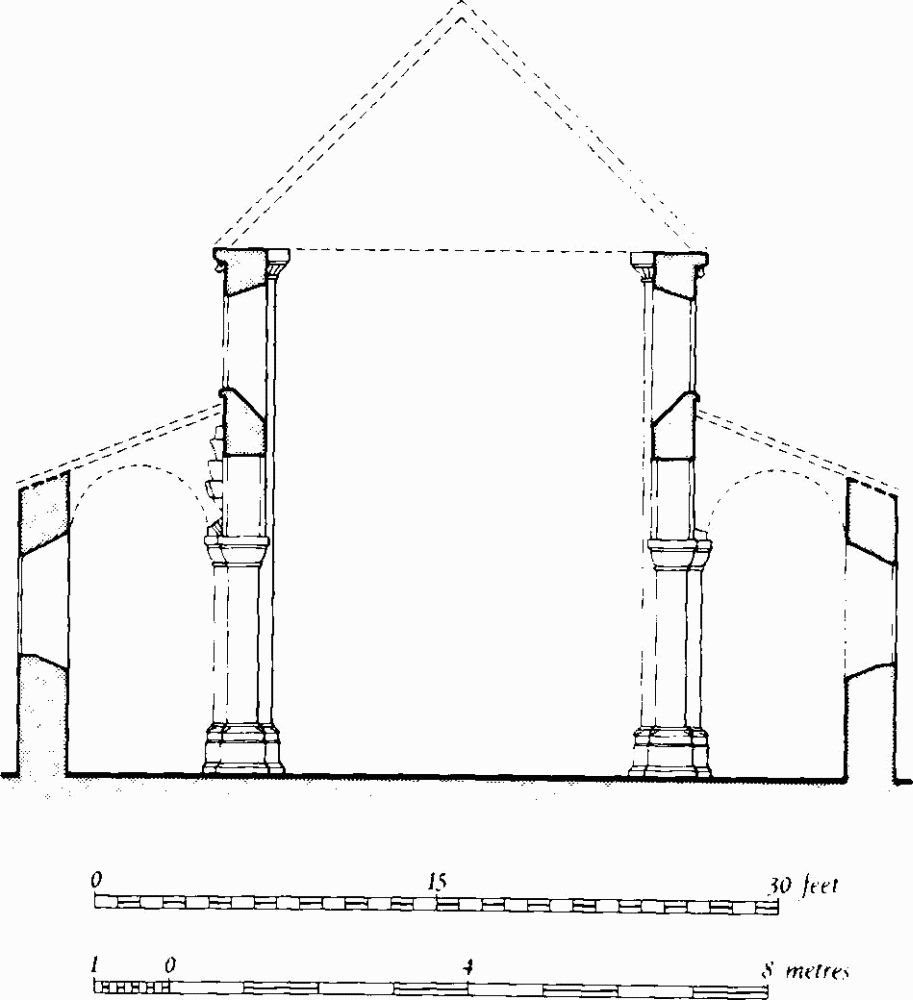

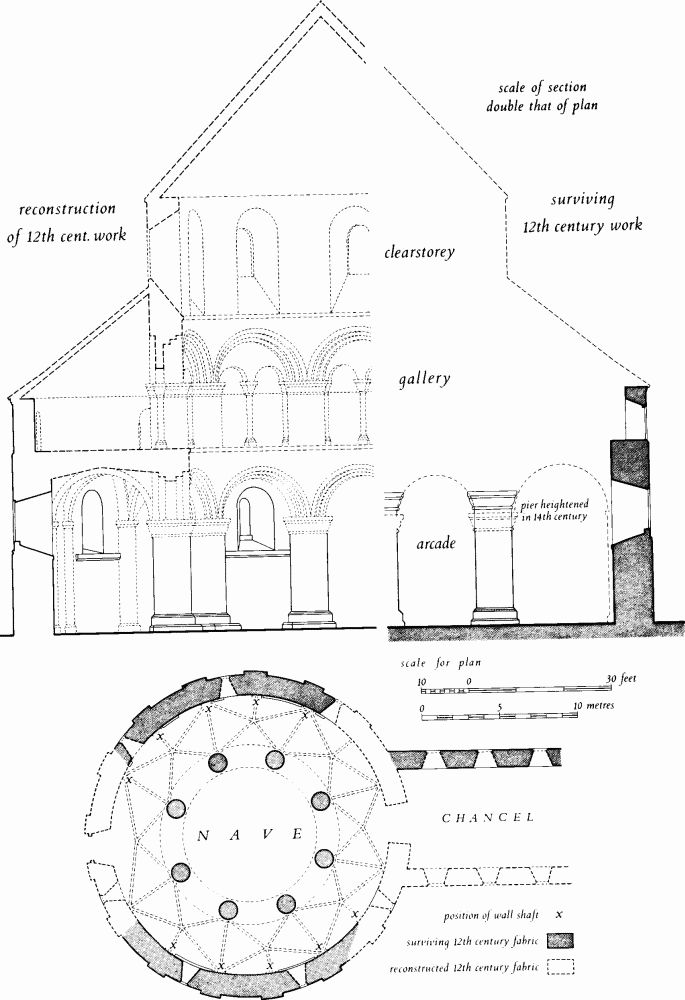

Northampton probably owed much of its growth to its geographical situtation in the middle of the country and astride important routes. This strategic position was probably consolidated by the marriage of Waltheof, the Saxon earl of Northampton, to King William's niece, the Countess Judith. Waltheof was executed for treason in 1076 and Maud, the daughter of Waltheof and Judith, married Simon de Senlis I, probably a cadet of the great Bouteillers family of Senlis, one of the most powerful in France in the 12th and 13th centuries. Simon was probably granted the earldom and the town of Northampton by William Rufus in 1089 and the Senlis family retained the earldom for the next 100 years. Simon died sometime between 1111 and 1113 and the town reverted to the king. Maud, however, married King David of Scotland in 1113 and there is some evidence that he was granted the earldom. Simon de Senlis II, however, had obtained both the town and the earldom by 1138. He died in 1153 and his son Simon de Senlis III, who was still a minor at the time, did not become earl until 1159. He remained earl up to his death in 1184 but never acquired the town which on the death of Simon his father had reverted to the crown and remained a royal borough (VCH Northamptonshire III, 3f; see also Serjeantson 1913 and Tait 1936, 155). Documentary sources are not prolific for the Senlis family but what evidence there is suggests that the family displayed considerable drive and initiative during Northampton's years of expansion after the Norman Conquest (cf. Serjeantson 1913). Simon de Senlis I founded the Cluniac priory of St. Andrew (Northampton (12)) and gave it substantial endowments and he is also attributed with the construction of the town walls (Northampton (7)). Simon de Senlis II founded the Cluniac nunnery at Delapré (Hardingstone (25)) just south of Northampton and it is probable that the Senlis family was responsible for church building and other works in Northampton in the 12th century.

Northampton's strategic location also made it a regular and convenient meeting place for councils and assemblies, secular and religious. Many parliaments and councils were held there from the time of Henry I to Richard II and it received many royal visits, by John on no less than 30 occasions (Markham 1898, 451; VCH Northamptonshire III, 2f). Detailed discussion of political events is outside the scope of this book but the meeting between Henry I and Robert, duke of Normandy in 1106, the trial of Thomas Becket in 1164 and the Great Council of 1176, all held at Northampton, serve to emphasise the town's central position in the affairs of state.

The prosperity of Northampton, however, was not based merely on an authoritarian presence and political considerations for its geographical position helped to make it a major trading centre and its markets and fairs were important. The first reference to a fair at Northampton occurs in the time of Simon de Senlis II (BM Cott Vesp E xvii f. 3a) but Northampton may well have had a fair before the Norman Conquest. Certainly in the Middle Ages its fair became one of the great fairs of England and ranked alongside those of Winchester, St. Ives and Boston; large royal purchases of furs and cloth are recorded during the reigns of John and Henry III (VCH Northamptonshire III, 24). Little is known of the local economic base but the manufacture of cloth was probably important. In 1202 Northampton, Leicester and Winchester paid £10 to be free of the assize of cloth, a figure only exceeded by York, Lincoln and Beverley (Pipe R 4 John, xx). At one point more than 300 weavers from the town are recorded (Rot Parl 2, 85). Woolmonger Street (vicus lanatorum) and Fuller Street (vicus fullonum) are recorded in the early 13th century (BL Cott Tib E v f. 153a, 176a). The few other street names which are known witness before 1200 the presence and separation of the various traders such as cordwainers, skinners, retailers and wimplers (BL Royal 11 B ix f. 129a; Luffield 2, 33; Mon Angl 5, 209; BL Cott Tib E v f. 173b; FEC 158).

The second half of the 12th century also seems to have been marked by the rise of a prosperous and politically aware burgess class. In 1185 the people of Northampton paid the king 200 marks for the privilege of farming the town themselves, thereby in part freeing themselves from the oppression and interference of the sheriff (Pipe R 31 Hen II, 46). From about this time the farm was probably paid to the Exchequer by reeves elected by the people themselves and the privilege of electing a reeve was certainly confirmed by Richard I's charter to Northampton in 1189 (Tait 1936, 175f; Markham 1898, 25–9; VCH Northamptonshire III, 4f). The charter of 1189 in which other rights were also granted was very closely modelled on that of London of 1155 (Ballard 1913, clxii et passim) and may have been to some extent a formalisation of existing arrangements. But in any case the granting of the charter at this time was in itself a significant event. In King John's charter of 1200 the right to choose four coroners was also granted (Tait 1936, 175ff; Markham 1898, 30–3). The first mayor seems to have been chosen in 1215 at which time the first record of a town council occurs.

To what extent the townspeople had been able to or had taken corporate action prior to the 1180's is uncertain. A 'Gildhalle' existed almost certainly at what was the centre of the Saxon borough at least from 1153, probably from 1138 and perhaps from pre-Conquest times (Northampton (10); Williams 1983–4, 5ff) but there is no record of action by the guild or in fact of its exact nature. In the 1170's and early 1180's eminent townspeople such as Philip, son of Jordan, and William, son of Reimund, are seen acting individually or in pairs undertaking royal assignments such as building work on the castle and the gaol (Pipe R 28 Hen II, 129; 29 Hen II, 119; 31 Hen II, 46). Solidarity within the burgess class is, however, perhaps best evidenced in Northampton's first customal dating to the mid 1180's (Leges ville Norht). Although the codification of the customary law is of considerable interest in itself it is the list of the 40 men who drew up the laws which sheds light on the social status of the leading burgesses. There is nothing to indicate that the 40 men were a formal council although the round number might suggest this. Many of them, whose careers can be traced in the Pipe Rolls, cartularies and other documents, were clearly wealthy. Family groups can be seen (e.g. Adam, Reginald and William, sons of Reimund and Robert and Ingram, sons of Henry) but prominent by their absence were the leading members of the local landed aristocracy such as the Gobion and fitz Sawin families. The 40 men thus appear to comprise a body whose wealth and influence seem to have originated in the town itself.

Fig. 7 Sites and monuments in Northampton.

Against this social, economic and political background the topography of early medieval Northampton can be examined (Fig. 7; Map 7). At the time of the Norman Conquest, Northampton comprised the area within the Saxon defences with perhaps some linear development outside the east, north and south gates though the evidence for this is limited (see above). Physical expansion of the town, however, in the late 11th century seems to have gone hand in hand with its economic growth and this is evidenced in a number of ways.

The early development of the castle (Northampton (9)) is problematical. It is not mentioned in the Domesday survey but according to the 'Vita et passio Waldevi comitis' was constructed by Simon de Senlis I (Giles 1854, 18). Otherwise the earliest documentary reference occurs in 1130 when the king paid 3s. 8d. for land taken into his castle; the first building works noted were in 1173–4. The castle was partly demolished in 1662 and most of what was left was destroyed in 1879. Excavation in 1961–4 by Dr. J. Alexander on the part of the castle then remaining uncovered a possible ditch predating the bailey bank of the later castle and this was tentatively identified as belonging to an 11th-century earth and timber motte and bailey castle. The limited archaeological evidence is consistent with an earth and timber castle dating to the time of Waltheof or Simon de Senlis I with work on the great medieval castle probably commencing sometime after the death of Simon de Senlis I and before the accession of Simon de Senlis II to the earldom of Northampton; during part of this time at least the castle was in royal hands (Pipe R 31 Hen I, 135).

In the Domesday survey 40 burgesses are recorded in the 'novo burgo' (DB f. 219a). This new borough should be equated with the area known as Newlands, lying outside the east gate of the Saxon borough and recorded in 1201 as 'nova terra' (BL Royal 11 B ix f. 131). A William 'de nova terra' (not necessarily at Northampton) is recorded in the Northamptonshire section of the Pipe Rolls in 1177 (Pipe R 23 Hen II, 95). It seems originally to have been a district rather than an individual street (cf. the modern Newlands) for early deeds indicate that properties described as in 'nova terra' actually lay in the modern Wood Street (RCHMs 1975, 1–11). An area on Speed's map (Fig. 8) bounded by the modern Newlands, Lady's Lane, the Mounts and Abington Street seems to be enclosed, except to the south-west, by a wall cut through by two streets, the modern Wood Street and Wellington Street. Since the Greyfriars precinct only covered a small portion of this area (cf. Williams 1978, 96–104, 116) it is tempting to interpret this apparent boundary wall as defining the extent of the 'novus burgus' but excavations at Greyfriars and Abington Street (Northampton (16, 37)) and watching briefs elsewhere within the area have produced no evidence of 11th-century occupation although the sites investigated mainly lay away from the street frontages.

The medieval defences (Northampton (7)) pose a number of problems (cf. Williams 1982c). Whellan (1874, 101) and Cox (1898, 427) ascribe the construction of the town walls to Simon de Senlis I, Wetton (1849, 27) more cautiously 'supposed' the same and Cam (VCH Northamptonshire III, 3) and the Ordnance Survey Record Cards refer to a tradition that Simon was responsible but no actual sources are quoted by any of these authorities. The construction of the walls was a massive undertaking which would have increased at an early date (cf. Turner 1971, 21ff) Northampton's intra-mural area to some 100 hectares, an extent only exceeded at London and Norwich (Biddle et al 1973, 11). An Eastgate Street (probably Abington Street) and an Eastgate, almost certainly belonging to the medieval defences, are recorded before c. 1166 (BL Royal 11 B ix f. 144b) and between 1138 and 1154 Earl Simon de Senlis II granted to St. Andrew's Priory 16s. and 14d. rent in exchange for rent lost 'propter murum et ballium quibus villa clauditur' (BL Royal 11 B ix f. 7a). Although the 'murus' is not specified as being Northampton's the context makes this virtually certain. This exchange perhaps suggests construction work at the time and parallels the situation noted above regarding the castle. Charters relating to St. Andrew's Priory add some substance to the tradition of the involvement of Simon de Senlis I in the erection of the town defences. The priory (Northampton (12)) was probably founded in the late 11th century by Simon de Senlis I. There is evidence that the house originally lay probably in Horsemarket and was subsequently transferred to its later site (Cal Pat R 1348–80, 247) but the scope of the endowment by Simon (Mon Angl 5, 190) suggests that it occupied the later site by c. 1100. Two further charters of Simon refer to 'hospites manentes extra vetus fossatum' (BL Cott Vesp E xvii f. 10b) and 'terra ... a fossa eorum [monks of St. Andrew's] usque ad fossam burgi' (BL Cott Vesp E xvii f. 3a). The 'vetus fossatum' in the first charter presumably refers to the Saxon defences but the interpretation of the topographical details in the second is more difficult. According to the Pierce map of 1632 (Plate 7) St. Andrew's Priory precinct did not extend as far south as the Saxon defensive line, although the priory did hold some land before 1130 on the site of the medieval castle (Pipe R 31 Hen II, 135). In the north and west boundaries of the medieval precinct are taken as the 'fossa burgi', that is as part of the medieval defensive system (see Map 7) and the south boundary as the 'fossa corum' all conditions are satisfied. Alternatively, 'fossa eorum' could be interpreted as the north and west boundaries with 'fossa burgi' as the south boundary and perhaps an 11th-century defensive line predating the priory. The use of 'fossa', possibly suggesting earthworks, contrasts with the 'murus' of a slightly later date which seems to indicate a stone wall. Stone quarries, probably of 12th-century date have been identified in Derngate (Northampton (39)). With the medieval defensive circuit largely covered by the modern road network it has not been possible to test satisfactorily through excavation the date of the medieval defences and the few ditch sections cut have produced extremely limited dating evidence. Sections of the wall and ditch survived up to the 19th century (see below p. 70 and fiche p. 330).

Fig. 8 Northampton in 1610 by John Speed. (Northamptonshire Libraries).