An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in Essex, Volume 4, South east. Originally published by His Majesty's Stationery Office, London, 1923.

This free content was digitised by double rekeying. All rights reserved.

'General Survey of Essex Monuments', in An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in Essex, Volume 4, South east(London, 1923), British History Online https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/rchme/essex/vol4/xxv-xxxvi [accessed 7 February 2025].

'General Survey of Essex Monuments', in An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in Essex, Volume 4, South east(London, 1923), British History Online, accessed February 7, 2025, https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/rchme/essex/vol4/xxv-xxxvi.

"General Survey of Essex Monuments". An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in Essex, Volume 4, South east. (London, 1923), British History Online. Web. 7 February 2025. https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/rchme/essex/vol4/xxv-xxxvi.

In this section

GENERAL SURVEY OF ESSEX MONUMENTS.

PREHISTORIC AND ROMAN.

Essex has yielded a rich harvest of finds of the prehistoric era, but contains few structural remains which can with certainty be referred to pre-Roman times. Of the burial mounds which have survived the plough, those that have been scientifically opened and recorded are, for the most part, of the Roman period. In regard to the 'camps' our information is even more scanty; slight excavations have been carried out in the earthworks of Epping Upland and Loughton with inconclusive results, and it cannot be claimed that the casual discoveries of much Roman pottery in Uphall Camp, Great Ilford, throw any light on the date of that earthwork. It is a reasonable conjecture that some of the long lines at Colchester belong to the time when, under Cunobelinus, who died shortly after A.D. 40, Colchester was in effect the capital of south-eastern Britain. Here history, however, begins to supplement archaeology, and later, in connection with the camp at Shoeburyness and with the Burghs of Witham and Maldon, written records become increasingly circumstantial.

Shortly before the advent of Julius Caesar, the close inter-relationship inevitable at almost all periods between south-eastern Britain and the opposite shores of the Continent had been intensified by a renewed migration from north-eastern Gaul. Caesar states that in the districts near the coast he found people who had come over from Belgium to plunder and wage war, almost all of them being called by the names of the tribes from which they had first come thither. The first part of this statement is apparently supported by the distribution of certain distinctive types of pottery (notably, the pedestal-urn) which occur, with variations, in the valleys of the Seine and Marne, and, on this side of the Channel, mainly in Essex, Kent and Hertfordshire. When this pottery first reached Britain is not clear, but it was in use in the 1st century B.C., and the pedestal-urn itself, and its associated types, seem to have survived the Claudian invasion. The second part of Caesar's statement presents more difficulty; tribal names such as Atrebates, Catuvellauni and Parish occur on both sides of the Channel, but the British Parish lay to the N. of the pedestal-urn zone, and there seems to be no definite evidence that the Atrebates had reached this country before the invasion of Caesar. On the other hand, the distribution of the pedestalurns in Gaul has been shown, by Mr. J. P. Bushe-Fox, to equate with the tribal area or sphere of influence of the Catalauni, and in his opinion, the distribution in this country forms an index to the extent of the occupation and influence of the same tribe (here called the Catuvellauni) shortly before and after the time of Caesar's expedition.

Other links between the two shores both before and after the Claudian conquest are important. The mysterious 'Red Hills' are found on the coasts both of Essex and of Brittany; and in Essex one of these contained a piece of Arretine ware, which probably came from the Continent at a time when discarded amphorae of Roman (or Mediterranean) origin found their way into pre-Roman graves between Colchester and Lexden. Much of the pre-Roman coinage found in Britain is now attributed to Gaulish mints; and the connection thus implied with the Continent was not weakened when, at the beginning of our era, British kings such as Tasciovanus and Cunobelinus produced their own currency with Latin inscriptions and even through the instrumentality of Roman moneyers. One of these coins, bearing the names Cuno(belinus) and Camu(lodunum), displays an ear of corn and is reminiscent of the prosperity of agriculture in south-eastern Britain, both when Julius Caesar was able to supply his troops from the standing crops of Kent, and when, in the time of Strabo and in that of Ammianus Marcellinus, Britain was exporting corn to the Continent. Finally, the large 1st and 2nd-century burial-mounds of Ashdon (Bartlow Hills), West Mersea, and, possibly, Colchester (Lexden), Hockley and Foulness, together with other examples in Kent, are to be compared with those which in the same period were raised over the ashes of Belgic nobles in the neighbourhood of Bavai, Tongres and elsewhere in the continental Belgic area. It is indeed worthy of remark that, though these identical burials on both sides of the Channel clearly indicate a common native tradition, analogies of immediately pre-Roman date appear to be lacking. The pedestal-urn burials had not been marked by mounds, and the evidence of the tumuli in question has not yet been correlated with that of the pedestal-pottery.

In the generation preceding the Claudian invasion, the intrigues which, with occasional interference from Rome, had for years been carried on amongst the princelings of south-eastern Britain and their kinsfolk on the Continent, culminated in the hegemony of the Trinovantes under the famous Cunobelinus, described later by Suetonius as "Britannorum rex." The tribal area of the Trinovantes coincided roughly with Essex and part of Middlesex, but the King himself was of the dynasty of the neighbouring Catuvellauni, whose capital was Verulamium (St. Albans), and history throws little light on the transfer of the seat of the Government from St. Albans to Colchester. As the native capital, Colchester became, in A.D.. 43, the first goal of the invading legions, the official centre of the imperial cult, and (then or shortly afterwards) the converging point of at least two main roads. About A.D.. 50 a colony was planted there, and, soon after the disasters which followed ten years later, the town was probably walled and assumed its permanent plan. With its 108 acres, it ranks in area considerably below several Romano-British towns, such as London, Wroxeter, Verulamium, Cirencester, and possibly Winchester. Its buildings, however, were commensurate with the status of the first Roman colony in the province, including, as they did, the Balkerne Gate and the vaulted sub-structure (? of a temple) under the Castle, buildings so far unparalleled, both in form and size, elsewhere in Britain. Moreover, in the neighbourhood of Colchester, West Mersea provides the foundations of a mausoleum which is equally without analogy in this country.

After the dramatic events of the 1st century, Colchester fades from Roman history. In fact, if not in name, York and London became respectively the military and the commercial headquarters of the province, and Colchester devolved into a prosperous country town, probably with a moderate foreign trade, but sufficiently far from the coast to stand aloof both from its immediate perils and from its responsibilities. To the period of the later Empire belongs the fort at Bradwell-juxta-Mare, a typical representative of the defensive works developed under Diocletian and Constantine I. It might be expected that Colchester would serve to some extent as a base-town for this new maritime frontier-system. But the forts established or reorganized under the Count of the Saxon Shore, unlike those of the earlier limites, were not based upon elaborate internal communications and permanent garrisons in reserve. In their case, supplies of men and provisions seem rather-to have been carried coastwise, and the base-fortress was replaced (at least in intent) by a mobile field-force under the Count of Britain, who must also have relied partly upon sea-transport in case of emergency.

The Roman occupation of Essex seems to have led to no important displacement of the native population. In the vicinity of Colchester, and in the north-western quarter of the county from Colchester to the Cambridgeshire border, country-houses of Roman provincial type sprang up immediately after the conquest, and were in many cases occupied probably by the wealthier of the natives, who were ready enough to submit to that Romanization which Tacitus calls "a part of their servitude." The very remarkable richness of the contents of the burial-mounds at Ashdon (Bartlow Hills), already referred to, testifies to the prosperity of some of these native landowners within the century following the conquest. In the same regions, apart from the Colony itself, a small walled town at Great Chesterford, and perhaps still smaller settlements at Chelmsford (? Caesaromagus), Brightlingsea and West Mersea are the only indications of anything approaching urban or village life. For the rest, the poorer natives seem to have continued to live in huts of their traditional type and to have carried on their industries, especially pottery-making, on the sites similarly used by their pre-Roman ancestors. At East Tilbury, the Thames mud has actually preserved the stumps of circular wooden huts occupied in the 1st, 2nd, and possibly the 3rd centuries A.D.. At Great Burstead the trenches cut apparently by pre-Roman potters in search of clay were occupied by kilns built in the Roman manner but tended doubtless by the native workmen; and at Shoeburyness a similar continuity seems to be indicated by kilns associated with Roman and pre-Roman pottery.

Apart from the remains of a 'villa' at Wanstead, no certain traces of any more highly civilized occupation are recorded in the southern half of the county. Towards the west, dense woodland must have obstructed agriculture and settlement. Towards the south-east, the low-lying marshlands, though shown by the submergence of Red Hills, of the East Tilbury huts, and of part of the Bradwell fort to have been higher in Roman times than now, can have offered little attraction for settlement on any elaborate scale. In this respect the Essex shore differs markedly from that of Kent, where the remains of comfortable 'villas' are found in considerable numbers. It is probable, indeed, that the embanking and draining of some of the low lands bordering upon the Thames was begun by the Romans—Southwark, for example, was almost certainly protected by a series of dykes at this period. But the absence of buildings of Roman type from the Essex flats renders it tolerably certain that no attempt on any extensive scale was made by the Romans to reclaim them. It has been pointed out that certain low-lying settlements of early Norman date, such as West Thurrock, seem to imply the pre-existence of dykes, and that these are far less likely to have been built then than in Roman times; but it must be remembered that the gradual lowering has very considerably aggravated the necessity for such protective measures.

In summary, it may be remarked that Essex is singularly representative of all phases of Romano-British life; it contains a military site, two arterial roads, a town of colonial and at least one of inferior rank, several country houses of fully Romanized type, and some of the wattle huts, preserved by an unusual accident, of the simple peasantry who must have formed a large element in the population of the country.

R. E. M. Wheeler.

ANGLO-SAXON AND DANISH.

The change from Roman to Saxon rule is perhaps more obscure in Essex than in other parts of England. It might well be expected that the estuary of the Thames would form a safe and convenient haven for the disembarkation of the early Saxon immigrants, but if they used its northern shore, they passed on inland without leaving any distinct evidence of their presence. One reason, no doubt, for the sparse settlement of the district during the century or more after the withdrawal of the Roman legions was that much of the country was forest and marsh, unsuitable for the early settlers, who were agriculturists. The early Saxon cemeteries which have been discovered at Broomfield and Feering and the Saxon burials around Colchester are probably late in the pagan period of the Saxon settlement and may perhaps be assigned to the first half of the 7th century. They therefore throw little light on the subject. The villages of Essex are chiefly of a type which is considered Teutonic in origin, but their prevalence gives no precise date for their formation. This type, however, is interesting as explaining the lay-out of many of the villages in the county at the present day. The original settlement of this kind stands a little way off the high road surrounded by its territories which formed its open common fields. At one end of the village is the manor-house, adjoining which the lord in the 11th century built the church. In frequent instances the inhabitants migrated to the roadside to obtain the benefit of the traffic, and here a new village arose. Sometimes this migration has been so complete that the church has been left isolated.

No structural monuments of the East Saxons belonging to the period before their conversion to Christianity survive. In 604 St. Augustine sent Mellitus to convert them and to be their first bishop. Their conversion, however, at this time seems to have been merely formal and they soon returned to paganism. They were reconverted some fifty years later, when, in 654, Cedd, brother of St. Chad, was consecrated their bishop. To evangelize the country, according to the custom of the time, Cedd established two monasteries in Essex, in which he placed monks who went forth to preach the Gospel. One of these monasteries was founded at West Tilbury, of which no trace remains, and the other at Ithancester, the Roman station of Othona, the church of which has been identified with the chapel of St. Peter-on-the-Wall at Bradwell-juxta-Mare (post, p. 15). This chapel is one of the few examples existing in this country of a 7th-century church and is therefore of peculiar interest. It takes its name from its position on the site of the wall of the Roman fort and was almost wholly constructed from the Roman tiles and other materials found within the fort. Its original plan was of a type usually to be met with in Kent, and consisted of a sanctuary, formed by an apse, and a small oblong nave with western porch and possibly a porticus on the north and south sides. The chapel was for a long time used as a chapel-of-ease to the parish church and hence its preservation. For a time, however, it was desecrated and used as a barn, until it was recently restored to its original use after having been put in a condition of excellent repair. Erkenwald, bishop of the East Saxons, founded a monastery at Barking in 666 for the benefit of his sister Ethelburga; and by tradition St. Osyth, granddaughter of Penda, established a monastery about 683 at Chich St. Osyth. Nothing remains of either of these churches, both of which were doubtless obliterated by the later buildings which arose on the sites.

At this early date London was the chief town of the East Saxons and the residence of their King and bishop. Its wealth attracted the cupidity of the Danish raiders in the 9th and 10th centuries, whose approach to it was through Essex. Hence the county was constantly devastated and there can be little doubt that many of the churches were robbed and destroyed by the pagan hosts from Denmark and Scandinavia. The monasteries of Barking and St. Osyth are said to have been then attacked and deserted, and a similar fate no doubt befell the other religious houses of the county. Thus for lengthy periods the organized services of the Church were interrupted and church building ceased. Unlike their treatment of the Danelagh, the Danes made few settlements in Essex; it was to them merely a camping ground and a place of refuge when their hosts were hard pressed in other parts of the country. In this way they made use of many of the fortified enclosures of masonry and earth which they found ready to hand, for they had a much higher appreciation of the protective qualities of such forts than their opponents. They repaired the fortifications of the Roman walled towns and adapted the early camps to the more modern methods of warfare. In the opinion of the late Mr. Chalkley Gould, they utilized and altered the earlier camps of Wallbury in Great Hallingbury and Danbury and the entrenchments at Uphall near Barking (V.C.H. Essex, I, 281–3, 289). Earthworks at Benfleet and Shoebury, however, were thrown up as Danish forts. In 894 the Danes were defeated by King Alfred at Farnham in Kent, when they fled to an island in the Colne and thence to South Benfleet. Here Hasten built a fort, indications of the site of which still survive (post, p. 139). The Danes were again defeated here by the English army, which had been reinforced from London. The English took much booty and sent what Danish ships they could to London and burnt the rest. Charred remains have been found at Benfleet which it is suggested represent the Danish ships then destroyed. The survivors of this engagement fled to Shoebury where they threw up another fort, of which the remains of the earthen defences still survive (post, p. 144). This camp was probably of a more permanent character, for we learn from the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle that it served again as a place of refuge later in the same year. In 895 the Danes established themselves in Mersea Island, but no recognizable trace of their residence can be identified nor can any remains be found on the east side of the Lea of the forts built there in the same year when the Danes were again compelled to abandon their ships.

The Danes had taught the English the value of earthworks as a means of defence. During his long campaign against the Danes at the beginning of the 10th century, Edward the Elder spent some time in Essex carrying out his scheme for the erection of 'burns' or forts throughout the country. In 913 he was at Maldon superintending the building of the 'burh' at Witham, some fragmentary remains of which survive (Essex, II, p. 265). In 920 he visited Maldon again, where he built a 'burh,' of which no trace remains (Essex, II, p. 173); possibly it was destroyed after its capture from the Danes in 991.

As might well be expected, no buildings belonging to this long unsettled period have survived in Essex to be scheduled in this Report. Houses for domestic use must have been erected to meet a periodical demand, but they were of an unsubstantial character only intended to meet the needs of the moment. It is unlikely that any churches would have been built at a time when they were the chief objects for plunder by pagan raiders. It was not until the religious revival in the latter part of the 10th century and the gradual conversion of the Danes and Northmen to Christianity that the building of churches commenced. The great era of church building began in the 11th century. Except the chapel of St. Peter-on-the-Wall at Bradwell-juxta-Mare, all the remains of pre-Conquest churches recorded in Essex probably belong to the fifty or sixty years preceding the Conquest. The entries in Domesday of priests and churches, which by no means form a complete summary of the total number of priests and churches in the county, indicate that in 1086 there was a considerable number of churches the majority of which were probably in existence before the Conquest.

In a county which produces little building-stone probably most of the churches were originally built of wood and this may account for the scarcity of Saxon work which has survived. The timber-built churches would be replaced by stone structures in the latter part of the 11th and during the 12th century—whereby all traces of the earlier building would be lost. We are fortunate in having one example left us of a primitive timber structure. The church of Greensted (by Ongar), which it has been suggested is the wooden chapel (lignea capella) built in 1013 as a resting place for the body of St. Edmund on its way from London to St. Edmundsbury (Dugdale, Mon. Angl., iii, 99n, 139), still retains its nave of split oak logs. It is in good preservation and forms an excellent and perhaps unique example in this country of a timber church of its date. Probably it indicates a method of construction commonly used both for ecclesiastical and domestic purposes in the early part of the 11th century.

The remaining pre-Conquest churches of the 11th century are all of masonry or of brick taken from some Roman site not far distant from the spot when the church was built. The most important is the cruciform church of Hadstock (Essex, I, p. 143) that has been identified with the minster ' of stone and lime' which Cnut built in 1020 in memory of those who fell in the battle of 'Assandun,' where he obtained a victory over Edmund Ironside. The nave and north transept of the pre-Conquest church survive, but the chancel and south transept have been re-built, and the central tower, which probably formed a part of the original church, fell and was not built up again.

Most of the Saxon churches in Essex belong, however, to the type described in Professor Baldwin Brown's classification as consisting in plan of an oratory or nave with a rectangular chancel. Examples of this type of church are scattered over the county; they are not confined to any particular district, for their survival is only a matter of chance. They may have been better built than others and so did not require to be re-built, or no pious benefactor arose who desired to leave his mark upon his parish church. The principal instances of this type of church are at Chickney (Essex, I, p. 62) and Inworth (Essex, III, pp. 138–9). The nave of Strethall church (Essex, I, p. 295) is a particularly interesting example of a date a little before the middle of the 11th century and the Saxon chancel-arch remains in good condition. Sturmer (Essex, I, p. 297) has a nave of about the same date as that at Strethall. At Corringham (post, p. 25), parts of the south walls of the chancel and nave are of pre-Conquest date, and at Great Stambridge (post, p. 58) the north walls of the chancel and nave contain work of the same period. The thinness of the north wall of the nave of Fobbing church (post, p. 44) suggests a pre-Conquest date, and indications of early work at the west end of the north wall of Wethersfield church (Essex, I, p. 332) may perhaps assign the original church to a like period.

Little Bardfield church (Essex, I, pp. 170–1), with its contemporary western tower, is a development of the same type. Its chancel has been re-built, but the nave with its windows in the north and south walls and north doorway, all now blocked, is original. The western tower is a good example of a fine 11th-century tower of five stages, the three upper stages having their original round-headed windows. Another example of a pre-Conquest western tower is to be found at Holy Trinity Church, Colchester (Essex, III, pp. 33–5). This tower is of three stages and is an addition to a pre-Conquest church of which only a small portion of the west wall remains. It is typically tall and slender and a contrast to the bolder design of Little Bardfield tower of about the same date.

Two further monasteries were founded towards the close of the Anglo-Saxon period, Mersea, a cell of St. Ouen at Rouen, by Edward the Confessor in 1046, and the famous minster at Waltham by Harold in 1060. At neither of them, however, are there any structural remains of a date definitely before the Conquest.

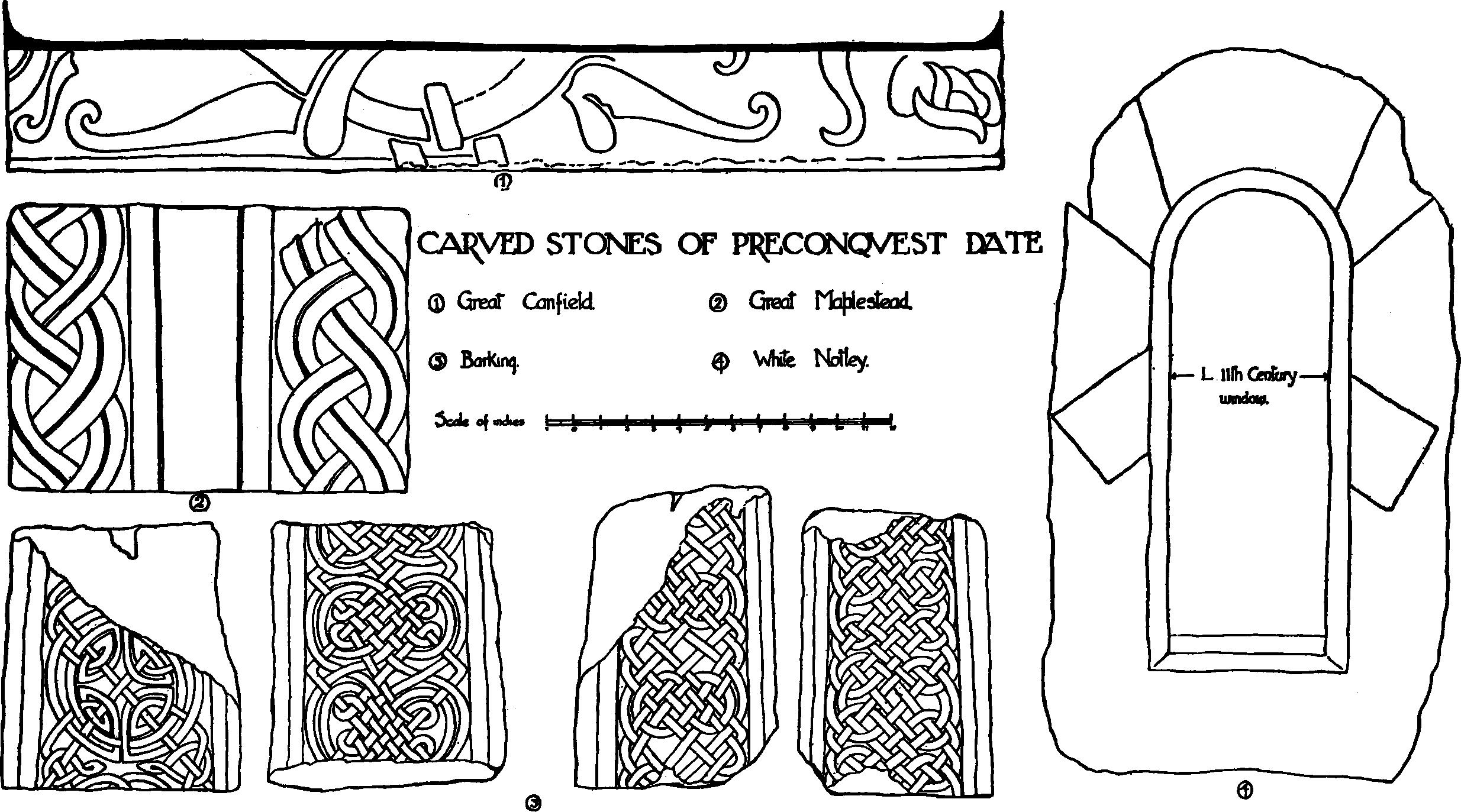

Only four stones with incised ornament of the pre-Conquest period are known to have been discovered in Essex. The earliest is a fragment of the shaft of a cross found built into the churchyard wall at Barking and now preserved in the church. It is ornamented on all four sides with plaits of true Anglian tradition which Mr. W. G. Collingwood, F.S.A., says are more elaborate than any he knows of before 870 and much more ingenious and regular than those of the 11th century. He attributes the date of the stone to the time of Edgar. It may well be that the cross was set up when the Abbey of Barking was restored by Edgar and Archbishop Dunstan about 970, after its destruction by the Danes a century before. Another stone at White Notley church has been used in the construction of a late 11th-century window in the north vestry. It was apparently part of a headstone and may be of the 10th century. It has some analogies with the pre-Conquest headstone at Whitchurch, Hants, and with a stone at Hexham. At Great Canfield church is a stone forming the abacus to the capital of the respond to the chancel-arch, upon the upper surface of which is zoomorphic ornament in low relief, of Danish workmanship. Its position prevents a complete examination of the ornament as a part of it is hidden by being bedded into the wall. It is probably a sepulchral stone of the early part of the 11th century, and closely resembles the Toui stone in St. Paul's Cathedral Library. The fourth carved stone was found not long ago on a rockery at Great Maplestead and has now been placed in the church. It was evidently part of a coped coffin-lid having a plain fillet running down the centre and sunk panels with interlaced ornament in relief on either side. When perfect the ridge would have formed a cross. It belongs probably to the end of the Saxon period and Mr. Collingwood would place it after the Conquest.

Carved Stones of Pre-Conquest Date

On the whole, Essex is not rich in Anglo-Saxon monuments. Danish influence, which for some time was strong, was destructive rather than constructive.

W. Page.

ARCHITECTURE: COMPARATIVE REVIEW.

The completion of the Commission's investigation of the County of Essex provides a suitable opportunity for a general review of the county as a unit and also of the methods and principles which are the foundation of the Commission's system of dating. A county, and more especially a large county like Essex, is in area sufficiently extensive to make a series of deductions from the information collected about its monuments a useful contribution to the study of comparative architecture and archaeology, though at the same time care has to be taken not to make the application too general.

The system of dating mediaeval, and, to a less extent, Renaissance architecture is, of course, primarily based on a series of examples all over the country of which the period or year of erection is recorded either in contemporary documents or on the buildings themselves, the vast majority of such buildings being of the class which comprises cathedrals, monastic and collegiate churches, castles and the larger houses of the country. The precise date of a parish church or small manor-house has been in too few instances preserved, and it is often dangerous to argue by analogy from the town to the country parish, from the main currents of contemporary life and thought to the backwaters, where new ideas may have taken long to penetrate. In the absence therefore of definite historical evidence, other tests have to be applied and it has been found that the character of the mouldings, the window-tracery and other ornamental details are the surest guides to the date of a building, though when these also fail, recourse must be had to such indications as may be provided by proportions of plan, thickness of walls and character of masonry.

Our investigations have shown that the pre-Conquest work of the county is probably nearly all of the later Saxon period, that is, they belong to the last 100 years of Saxon or Danish rule. The only exception is the chapel of St. Peter-on-theWall, Bradwell-juxta-Mare, which belongs architecturally to the class of church built in the early years of Saxon Christianity and of which the distinguishing features are the apsidal chancel, the triple arcade between the chancel and nave, the presence of rectangular 'porticus' (used as porches and chapels), and a relatively high level of constructional ability.

The later Saxon building has far less marked characteristics, though in Essex such characteristics are very uniform and not difficult to recognize. The plan generally is marked by an entire lack of care in setting out and the angles are seldom rightangles; the proportions of the nave are commonly rather less than two squares, (fn. 1) and the walls are, in nearly all the recorded instances, less than 3 feet thick, the average being about 2½ feet. The walls are always of rubble, and most frequently the quoins and dressings are of rubble also, but of rather larger stones than the rest of the wall. Long and short work, that is to say, freestone quoins placed alternately horizontally and on end, and generally accepted as a distinctive feature of late pre-Conquest work, is but little represented in the county, the only definite example being at Strethall. The windows are commonly of the double splay type, that is to say, the actual aperture (or plane represented in later ages by the glass-line) is placed more or less centrally in the thickness of the wall with equally splayed reveals both inside and out. This feature is exemplified at Holy Trinity, Colchester, Hadstock, Chickney, Strethall, Inworth and Little Bardfield, but is not present in the undoubted pre-Conquest work of Little Bardfield tower. Post-Conquest examples of double-splay windows occasionally occur, though not in Essex, but they are almost always in conjunction with detail which leaves no doubt as to their later date. Another pre-Conquest feature is found in the absence of a rebate or door-check on the jambs of the doorways, of which there is an example at Holy Trinity, Colchester, in conjunction with a triangular head, another pre-Conquest feature, probably borrowed from Carolingian work on the Continent.

Turning from the consideration of points of construction and form to that of architectural detail and ornament, the distinctive features are equally clear when contrasted with work of the succeeding period, though mouldings and ornament were but sparingly used by the earlier builders. Late pre-Conquest mouldings are almost invariably distinguished by a lack of form, by a poverty of ideas and an amateurish execution which shows that the mason was attempting an unfamiliar task with little or nothing to guide him but a remote and distorted tradition of debased Roman work. The only exception to this is at the rather ambitious church at Hadstock, where the feeble mouldings, above described, are reinforced by carving on the imposts, which recalls the Greek honeysuckle ornament and is not without some merit.

The 7th-century church of Bradwell-juxta-Mare, as has been said, stands, so far as Essex is concerned, in a class by itself. It is built almost entirely of Roman material from the adjoining station of Othona and conforms in plan to the type of the early churches to which SS. Pancras and Martin, Canterbury, the early churches at Rochester, Reculver and Lyminge, Kent, and South Elmham, Suffolk, belong. It is remarkable for having retained some original windows which are of comparatively large dimensions and of simple rectangular form with wooden lintels to the heads. The buttresses are of the simple pilaster type, weathered at the top, and the chancel formerly terminated eastwards in an apse.

Another presumably pre-Conquest building standing in a class by itself is the timber-built nave of Greensted (by Ongar). This type of construction of split oak logs was no doubt common enough at the period, but Greensted appears to be now the sole surviving example of that age in the country.

Structural remains of the Saxon period have been noted in eleven or twelve churches in the county, a fairly high percentage (3 per cent.), compared to Hertfordshire with three churches (2 per cent.), and Buckingham with four churches (1¾ per cent.).

It is unnecessary to recapitulate here the distinguishing features of the succeeding periods of Romanesque and Gothic, but attention may be called to certain details not generally touched upon by the ordinary text-books. Late 11th or early 12th-century churches are unusually common in Essex and in nearly every case they follow certain well-defined conventions. The proportions of the nave of the Norman parish church in Essex were commonly two squares (i.e., the length was double the width), and where this proportion is departed from by a large increase of length there is prima facie evidence of the former existence of a central tower. The Norman parish chancel was either square-ended or apsidal, and there is little evidence as to which termination was the more popular, as in the great majority of cases the E. end was subsequently re-built. The apsidal ends are of two chief types: (a) the simple type, of the same width as the nave and without a chancel-arch, and (b) the more advanced type, where there is an arch across the chord of the apse and generally a chancel-arch further west. The first type either is or was exemplified at Little Tey, Little Braxted, Langford, Mashbury and Easthorpe, and the second type at East Ham, Copford, Hadleigh and White Notley. The west apse at Langford is probably unique in this country. Simple square E. ends survive at Castle Hedingham, Chipping Ongar, Elsenham, etc. The churches of Copford and Great Clacton belong to a very small and highly interesting class of church. (Chepstow Priory is the only other example in this country), of which the distinguishing feature is the groined stone vault, over the main body, divided into bays by cross-arches. In all three instances the vaults have been removed. The walls of a parish church of this period are almost invariably just under or just over 3 feet thick, and the rubble when of flint or septaria is commonly laid in regular courses; herringbone work is not uncommon, though this form of masonry may also be found in pre-Conquest work. The inclusion of Roman brick in the walls is more usual in this than in any other period. Twelfth-century ashlar may commonly be distinguished by the lines of the tooling running diagonally across the stone; in the 13th century the tooling was almost invariably upright and parallel to the edge of the stone. The 13th century, judging from the architectural level attained, was a period of depression in the county. The only remarkable structure erected during the period is the triangular W. tower of All Saints, Maldon, but except for its plan it is undistinguished.

The 14th century gives evidence of some recovery of building activity and here and there work was produced of a richness and variety not generally met with in a parish church, as in the chancel at Lawford, the S. aisle of All Saints, Maldon, and the chancel at Fyfield. The erection of the handsome chancel at Tilty and the chapel at Little Dunmow are due to the adjoining monasteries of which they formed part.

The wave of church building which covered East Anglia in the 14th and 15th centuries with great parish churches extended into the northern part of Essex, and produced the great churches of Saffron Walden, Thaxted and Dedham, and the less important structures of Coggeshall and Great Bromley, while the handsome tower at Brightlingsea belongs to the same type. The peculiarly East Anglian practice of panelling with knapped flint incased in stone is also in evidence in Essex, chiefly in the northern part of the county.

In the 16th century Essex suffered architecturally, like the rest of England, from the dissolution of the monasteries; of the churches of seven greater monasteries previously existing in the county only one, Waltham, has left substantial remains, though the nave of St. Botolph's, Colchester, shows that even some of the lesser monasteries had churches of considerable extent and magnificence.

The entire absence of freestone in the county of Essex necessitated its importation from elsewhere or the substitution of some other material. In the 12th century a certain amount of Barnack-stone, and other Northamptonshire oolites, was in use, but this material gave place later in the century to the soft limestone of Merstham and Reigate. A little Caen stone is observable in the remains of the larger monastic churches, and there are numerous instances of the use of Purbeck and Petworth marbles for decorative work, shafting and monumental masonry. Clunch or Totternhoe stone (a chalk stratum) is used for internal work in the northern part of the county. The rubble is normally of flint, but towards the east there is considerable use of pudding-stone (conglomerate of clay and pebbles) and septaria (hardened clay), both found locally. Of the substitutes, brick and timber, the former will be dealt with under domestic work, the latter was mainly used for towers only, though there are three instances in the county of timber churches. The towers of this material form a somewhat remarkable group, which it would be difficult to equal in any other part of England. The finest of these towers are at Blackmore, Margaretting, Navestock and Stock. In the most usual type the tower rests on massive angle posts with crossbeams, braces and framing, and is surrounded on three sides by a lower 'aisle' with a pent roof, and of which the framing serves to support and buttress the main structure.

The church fittings in Essex do not call for any very lengthy or particular mention. The woodwork is generally undistinguished, and. the screen-work in no instance rises above a very moderate level of excellence. Only one rood-screen (North Weald Basset), complete with its loft, survives in the county. In monumental art the county takes a much higher place. There are eight oak effigies of the 13th and 14th centuries, a high proportion for any one county, and the series of Vere monuments at Earls Colne and of Marney monuments at Layer Marney are equally interesting. Fine series of Renaissance memorials to the Smiths at Theydon Mount and to the Petres at Ingatestone also deserve mention. Essex is a good county for brasses both from their number and interest. Four brasses belong to the first half of the 14th century, and are consequently among the 25 earliest in the country. Eleven more examples have canopies more or less complete. Of individual fittings, perhaps the only ones of more than local significance are the carved 13th-century rood in the Gatehouse at Barking, the carved late 12th-century slab at Runwell, of which the original form is uncertain, and the painted 13th-century chest at Newport.

Type of 14th-Century House with Aisled Hall

Type of 15th-Century House central hall without aisles

Type of Late 15th & Early 16th-Century House with continuous eaves

Type of Late 16th & Early 17th-Century House with two-storeyed main block

From the point of view of comparative archaeology the domestic buildings of Essex are of much greater importance than the ecclesiastical. Probably in few of the other counties of England can so great a mass of mediaeval building be found, while on the continent of Europe this class is practically non-existent except in towns. The Commission has inventoried in the county some 750 secular buildings of a date anterior to the Reformation. There are no definite examples of the 12th century and only one (Manor House, Little Chesterford) of the 13th, but the 14th, 15th and early 16th centuries are represented by so great a number of examples as to render the deductions drawn from so large a mass of evidence of more than local value. The vast majority of these buildings are of timber and belong to the small manor-house, farm-house and cottage classes, and as such form a remarkable commentary on the social and economic history of the country. The 13th-century and nearly all the 14th-century examples belong to the type of which the distinctive feature is the timber-aisled hall, which can be traced back to the earliest Saxon times and perhaps even earlier. Of this type there survive in Essex some six or seven examples, all with the same external characteristics—the central hall open to the roof, which is carried down over the side aisles to within 6 or 8 feet of the ground, and the gabled cross-wings at each end of the hall, two storeys in height, one containing the solar and the other the buttery and offices. The roof construction is always of the king-post type, except in the case of Gatehouse Farm, Felsted, which has a roof of queen-post type, probably arrived at by the desire to dispense with the oak columns of the aisles. No instance of the aisled hall has been found later than the 14th century, and the type had no doubt been generally abandoned before the close of the century. A 15th-century building in Essex can generally be distinguished by its outline, a central hall (still open to the roof) with two storeyed cross-wings at the ends, the eaves of the hall being thus at a much lower level than the eaves of the cross-wings. The upper storey of the cross-wings generally projects at one or both ends, a feature which is not found in the previous period. The roofs are of the king-post type, except in the few instances where the hammer-beam or the curved principal is preferred. The timbers and joists are heavy and set close together, the floor joists being commonly laid flat instead of upright in the modern and more scientific manner.

Late 15th and early 16th-century buildings show little variation from this type except that there is a more frequent occurrence of the hall block divided into two storeys. A not uncommon feature of small early 16th-century houses is the lack of gables to the cross-wings, the eaves being carried continuously across the whole front and their deeper projection over the hall block being supported by curved braces from the wings. The windows of the early houses seem to have been divided into lights by oak upright bars set diagonally in the frame and with no provision for glazing. This feature, however, seems to have been occasionally used down to the 17th century and is consequently no safe criterion of an early date.

After the Reformation timber domestic building seems to have gradually lost its standard form; the timber studs and joists are set wider and wider apart and the individual timbers become less and less substantial. A late 16th or 17th-century house of the early plan can generally be distinguished from a 15th-century example by the lower pitch of the roofs and by the general level of the eaves being maintained throughout the building.

With the Reformation and the advent of the new Tudor aristocracy began an era of domestic building on a large scale. Essex is well provided with examples of of this and the succeeding periods, among which may be mentioned Audley End, Moyns Park, Hill Hall, Layer Marney Hall, Gosfield Hall, Belhus and New Hall, Boreham. Other great houses of the 16th century, such as Little Leighs, Rochford Hall and St. Osyth's Priory, have suffered more or less from demolition. Of large houses of the mediaeval period only Faulkbourne Hall and fragments of Nether Hall (Roydon) survive, though there were extensive domestic buildings of the Veres at Castle Hedingham, a royal palace at Havering and a palace of the Bishops of London at Orsett.

The use of brickwork in Essex became very common in the 15th century, but before that time there is ample evidence of the occasional use of this material from the 12th century downwards. This early use of brick is perhaps commoner in East Anglia, and its comparatively frequent occurrence in the webs of 14th-century vaulting and similar positions where chalk would have been equally efficacious seems to negative the possibility of importation. The shaped bricks used in the late 12th-century columns at Coggeshall Abbey were evidently made for their present positions and consequently are almost certainly of local manufacture.

A. W. Clapham.