Survey of London: Volume 47, Northern Clerkenwell and Pentonville. Originally published by London County Council, London, 2008.

This free content was digitised by double rekeying. All rights reserved.

'The Angel and Islington High Street', in Survey of London: Volume 47, Northern Clerkenwell and Pentonville, ed. Philip Temple (London, 2008), British History Online https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vol47/pp439-455 [accessed 10 February 2025].

'The Angel and Islington High Street', in Survey of London: Volume 47, Northern Clerkenwell and Pentonville. Edited by Philip Temple (London, 2008), British History Online, accessed February 10, 2025, https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vol47/pp439-455.

"The Angel and Islington High Street". Survey of London: Volume 47, Northern Clerkenwell and Pentonville. Ed. Philip Temple (London, 2008), British History Online. Web. 10 February 2025. https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vol47/pp439-455.

In this section

CHAPTER XVII. The Angel and Islington High Street

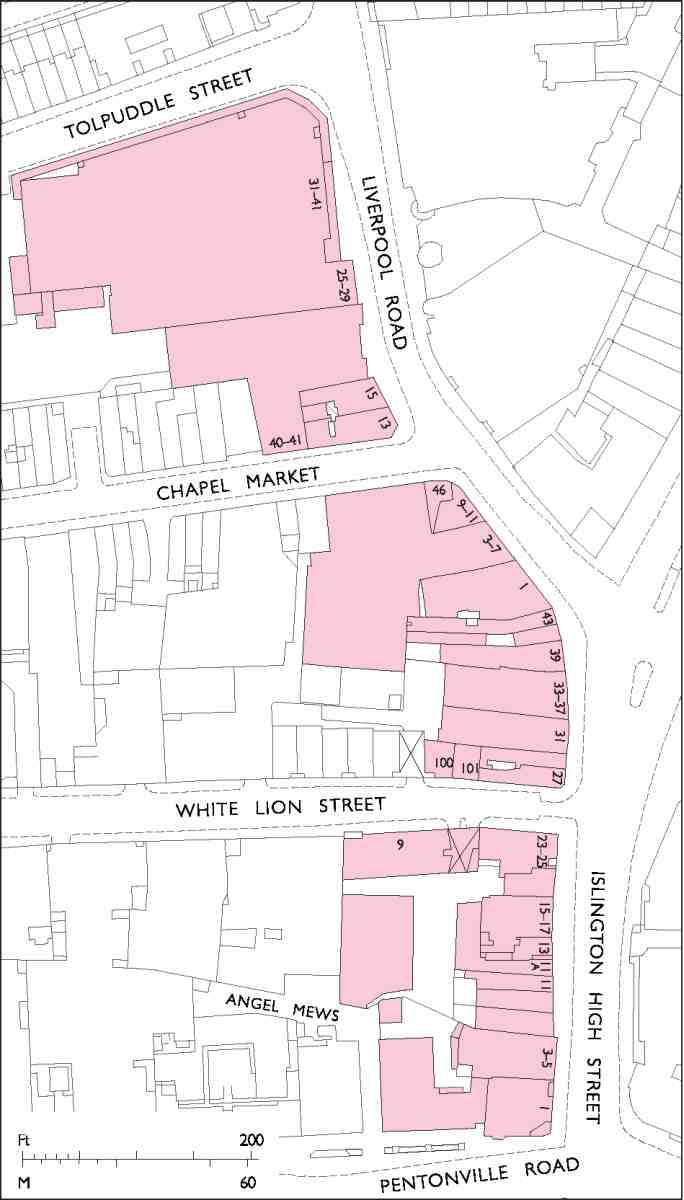

Islington High Street is a place of ancient settlement, the consequence of its key position for travellers to and from London. A short road, it runs from the convergence of Upper Street and Liverpool Road to that of St John Street and Goswell Road (Ill. 570). All these are roads of at least medieval origin. The addition of the New Road and City Road to this nexus in 1756 and 1761 created what has since become one of the most important road intersections in London.

570. Islington High Street and south end of Liverpool Road

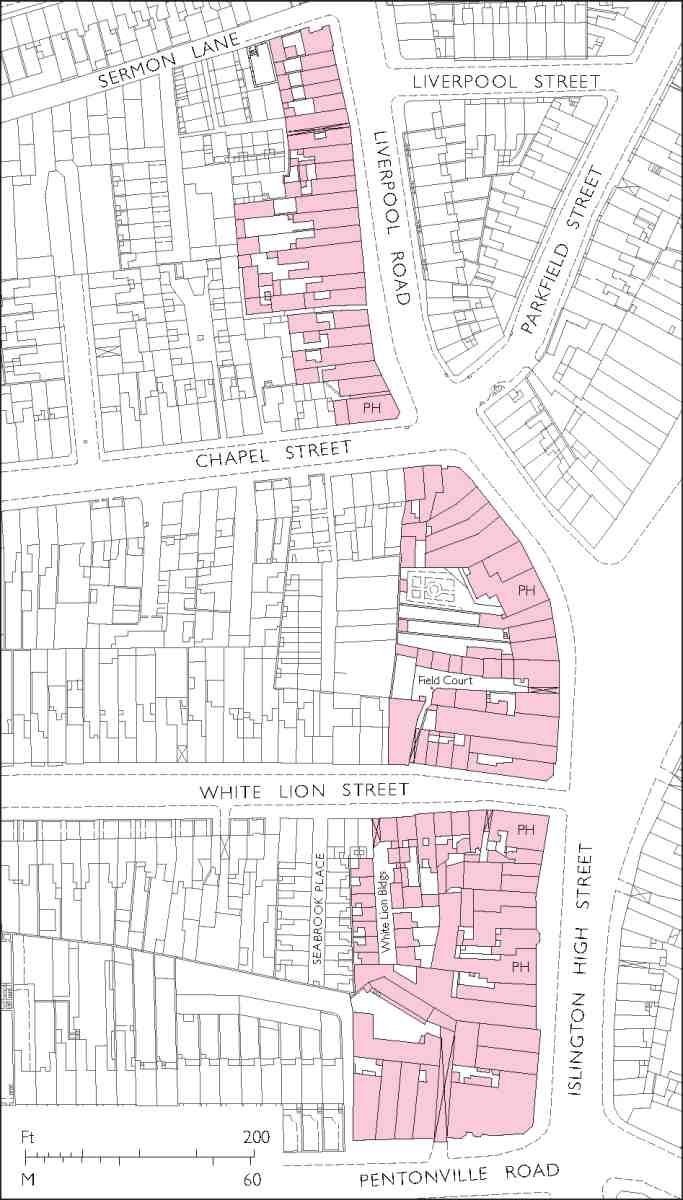

571. Islington High Street and Liverpool Road, c. 1874

Despite the name, the west side of Islington High Street belonged to the old parish of Clerkenwell, and it is dealt with on its own here (together with a short section of Liverpool Road also in Clerkenwell) on account of its historic separateness from the rest of the parish as regards development and character. Boundaries aside, it was always considered part of Islington, in common with the fields to the west built up in the late eighteenth century as the suburb of Pentonville.

572. Islington High Street in the late sixteenth century, with Liverpool Road shown as 'The Waye to Hollowaye'. From a map in Hatfield House collection

Islington High Street was already densely built up by the end of the sixteenth century. By 1700 development extended along Back (now Liverpool) Road towards the westwards turn of the parish boundary, at what is now Tolpuddle Street. (fn. 1) Of the earliest buildings nothing survives, and little is known. Some of Tudor, if not medieval, origins are visible in old prints (Ill. 589), and into the nineteenth century the High Street 'presented an antiquarian appearance'. (fn. 2) A late sixteenth-century map preserved at Hatfield House, with its suspiciously generic lobby-entry type houses, is probably unreliable as a visual representation of the early townscape, but important evidence nonetheless (Ill. 572). Six flag-like signs in front of the buildings on the Clerkenwell side of the road are indicators of the inns and taverns that came to line almost all this frontage, catering particularly for those bringing livestock to London from the north. Their presence was consolidated in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, a period that saw a boom in road transport and coach travel, and three became important coaching inns, with a nearly continuous combined frontage of more than 200ft; just outside London, they were the airport hotels of their time. The most important was the Angel, which has given its name to the locality in general and to the Underground station opposite, as well as to a property on the Monopoly board. Its long-standing status as a London landmark is now embodied in the inn's successor, a domed public house and hotel of 1903.

Islington High Street remained a stopping and shopping place for agricultural and other travellers into and out of London even once the town had grown to meet it. A scheme for a cattle market near the Angel, promoted in 1810, came to nothing and the inns were in decline by the 1820s when houses were being built on the fields in which many of their customers had rested their animals. The hostelries survived as public houses, still numerous until the 1960s. Just north of the Angel was the Peacock, somewhat smaller, but a substantial building of c. 1700 of which a part survives as No. 13 Islington High Street. The White Lion, once as big as the Angel and with a grander façade, was rebuilt in 1898 on the corner of the street that perpetuates its name. Further north were the Black Boy and Three Hats, rebuilt in 1839; the Pied Bull, on the turn to Liverpool Road, rebuilt in 1931–2 in a neo- Tudor style; and the Agricultural Hotel of 1862–3.

A challenge to the dominance of pubs was the building of a large luxury cinema here shortly before the First World War, intended for improving entertainment; only the entrance and tower now survive. Later pubs were surpassed as a primary presence by the arrival of shopping multiples. In 1951 Islington High Street was 'full of chain tailors and flashy shoe shops'. (fn. 3) Along Clerkenwell's section of Liverpool Road there is a Marks & Spencer store of 1930, a Woolworths, recently rebuilt but of similar vintage, and a large 1980s supermarket belonging to Sainsbury's, which has had a local presence (in Chapel Market) since 1882. Alongside these shops there are still places to drink and eat, but to the south finance has come to dominate—in the stretch that was the Angel, the Peacock and the White Lion are now the Co-operative Bank, Abbey National and HSBC.

The Angel intersection

The road junction at the Angel is fiercely and notoriously busy. It seethes with traffic and is a dangerous place to be preoccupied. This has long been so. Traffic bottlenecks and frequent accidents led to widening at the south-east corner in 1879–80 (see Survey of London, volume xlvi). Growing congestion and a tangle of tramway lines made the Angel an obvious target for further improvement, and proposals were regularly floated after 1900. At mid-century, still traffic-clogged and 'roofed in with a network of trolley-wires', (fn. 4) the intersection was part of London–wide plans for traffic management that envisaged cleansweep rebuilding.

By 1970 there had reportedly been nineteen schemes in seventy years. The Greater London Council then put forward plans for a large roundabout, working with Islington Council, which retained Star (Great Britain) Holdings Ltd as developers, and Llewelyn-Davies, Weeks, Forestier-Walker & Bor as architect-planners, for a project that included shopping subways and a tube station, rather like that carried out at the Old Street roundabout. This was planned 'to revitalize the Angel without destroying its personality as a place'. (fn. 5) The Angel Planning Study gained Government approval in 1973, but it had met strong opposition, local, professional and conservationist, led by the Islington Society and the Homes Before Roads lobby; the Angel Action Group advanced the argument that real improvement would come only if traffic was restrained rather than facilitated. In 1975–6 the GLC looked into less ambitious options for improving the blighted intersection. A version of these gained approval in 1979, but, with political changes, was abandoned in 1981, when the Angel Conservation Area was designated, taking in the whole west side of Islington High Street. Concern about traffic at the essentially unimproved junction flared up in 1996, when pedestrian users protested, but there has been no substantial change for the better. (fn. 6)

The following accounts of buildings begin with the old inns and later public houses, taking them in topographical order from south to north. These are followed by descriptions of the other buildings on the west side of Islington High Street and Liverpool Road south of Tolpuddle Street.

The Angel

The property that became the Angel was known as Sheepcote in the early sixteenth century and was part of the extensive lands that belonged to St John's priory. (fn. 7) There was an inn here by the end of the century, that was then depicted as the biggest building on this side of Islington, with a three-bay front, a southern cross-range, a gateway alongside to the north, and what was probably a free-standing stable range to the south (Ill. 572).

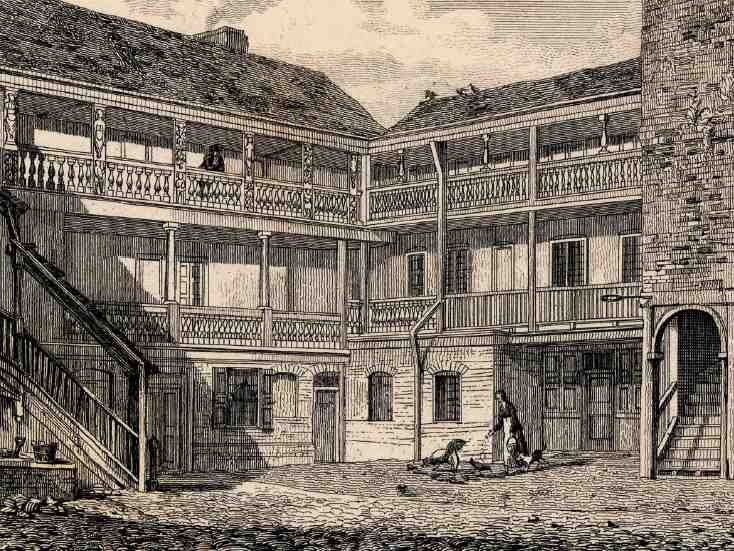

This establishment was called the Angel by 1614, and it was then of sufficient importance to be used for the holding of manorial courts. (fn. 8) By the 1630s it appears to have come into the hands of William Riplingham, a minor courtier from Warwickshire. Riplingham was an officer of the Great Wardrobe under two nobles also with Warwickshire connections: William Feilding, 1st Earl of Denbigh (brother-in-law of the 1st Duke of Buckingham, favourite of James I); and Spencer Compton, 2nd Earl of Northampton, a major Clerkenwell landowner and lord of Clerkenwell manor. The Angel may have come to Riplingham through Compton, as the 3rd Earl was identified as the Angel's owner in 1677. In or about 1638 Riplingham was fined for erecting (against building–control proclamations) 'a new building in the Angel's Inn in Islington'. (fn. 9) Riplingham's building was most likely one of the galleried courtyard ranges that survived into the early nineteenth century—perhaps the more ornamental west range, which had 'Tuscan' columns on the first floor and carved caryatid and other figures and pendant festoons on the upper floors (Ill. 574).

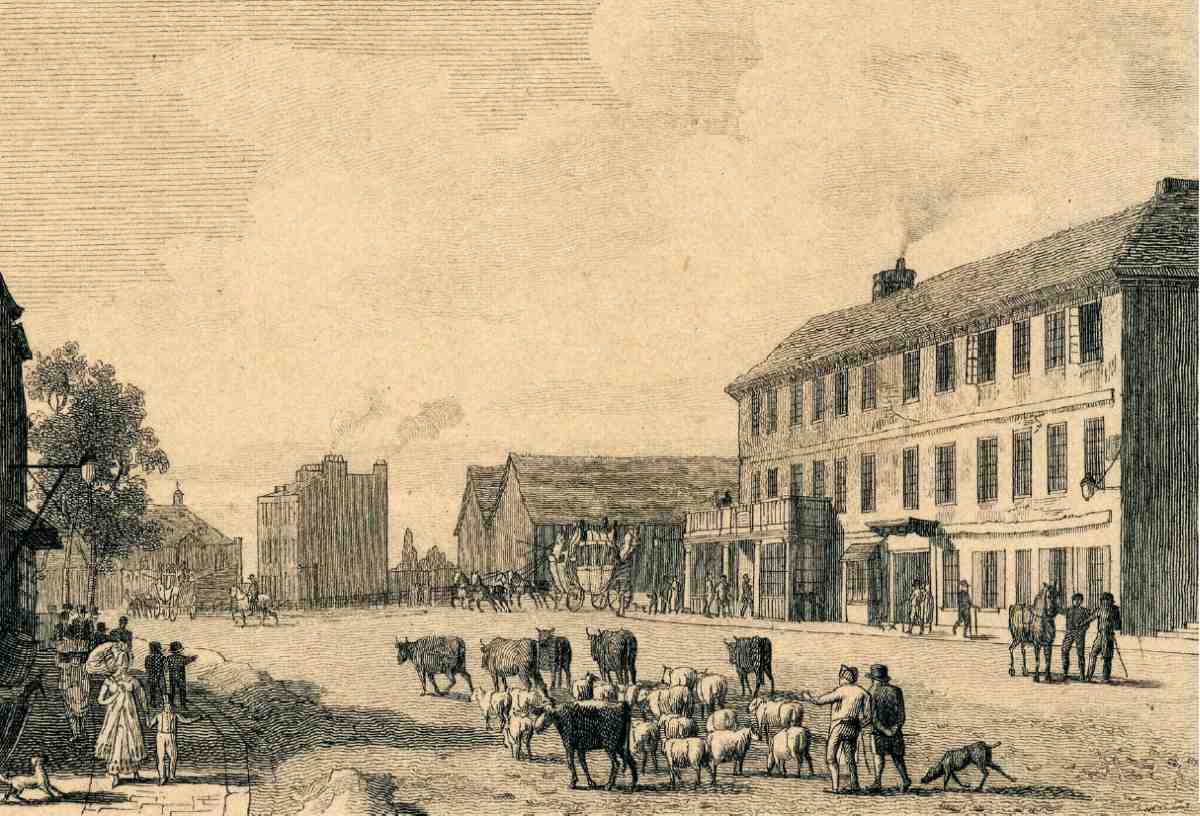

573, 574. The Angel Inn, in 1818. Front range with stable buildings behind looking south along Islington High Street, and (below) courtyard, probably looking north-west

575. The Angel Inn. Site plans in 1750s (left) and 1817 (right), showing impact of the New (Pentonville) Road. Variations in the main courtyard follow original sources

At some point in the seventeenth century, the front block was rebuilt in brick. A three-storey range of twelve bays with a frontage of almost 90 ft, it was plain but elegantly proportioned with a heavy classical cornice under a hipped roof (Ill. 573). Conceivably, this rebuilding might have been done in the 1630s through Riplingham, but its appearance suggests a somewhat later date. There are similarities with Northampton House, built in southern Clerkenwell by the 3rd Earl of Northampton in the 1660s (see Survey of London, volume xlvi).

By 1666 the Angel was occupied by Edward Fawcett, innkeeper. He held the Angel, at least part of it as a freehold, up to his death in 1696. With 23 hearths, this was a major inn and post-house. (fn. 10) Unlike the coaching depots off the south end of St John Street, the Angel was understood to be outside London. It provided extensive lodging for livestock traders, especially travellers destined for Smithfield market, and also accommodated long-distance coaches, in part for those who preferred not to risk arriving in the capital after dark, dishevelled, exhausted and vulnerable. Its location alongside pasture and its broad frontage distinguished it from London's typically more confined courtyard inns and gave it a country character. The amply quadrangular courtyard occupied the site of the present Nos 1–5 Islington High Street, and there was a separate enclosed stable-yard alongside to the south (Ill. 575). (fn. 11)

By the early eighteenth century the Angel was the biggest of a row of coaching inns along the High Street. Fawcett had been succeeded by Henry Hankin up to c. 1710, probably on a lease from Gibbons Bagnall, a London vintner, then by Henry Billingay, and from the late 1720s by John Winchester. Around 1744 the Angel was taken by Robert Bartholomew, who was succeeded by Christopher Bartholomew, probably his son, from 1766 to c. 1795. (fn. 12) The Angel was now a place of some renown, and in 1747 Hogarth used it as the setting for his famous depiction of coaching hubbub, 'the stage-coach, or the country inn yard' at 'the Old Angle Inn'.

A decade later the property was bisected by the New Road, which promised to bring much more cattle-droving business. The road cut through the inn's sheep pens and stable-yard, leaving the principal barn-like stable buildings intact on the south side. From 1744 the High Street inns had been joined by the New Inn, to the south on what is now the northern part of St John Street, an unsuccessful New River Company venture to cash in on the demand for accommodation from graziers and drovers. (fn. 13)

The Angel continued to provide for overnight travellers approaching London, also serving as a locus for public administration and other meetings in its larger 'assembly' rooms. The writing of the Republican Thomas Paine's Rights of Man has long been said to have been begun at the Angel in late 1790, as a monument across Islington High Street at Angel Square records. (Another tradition ascribes this to the Old Red Lion a little south in St John Street.) (fn. 14)

The Bartholomews were also tenants of the Angel Inn estate, a considerable acreage mainly in the parish of Islington, and were the proprietors there of the White Conduit House pleasure ground. As the land's development value increased the now much-divided ownership of the Angel Inn estate became subject to a protracted Chancery dispute, while Augustine Kemp ran the inn. By an agreement of 1817 the estate was divided into numerous parts, the Angel itself going to the Rev. William Coxe, and the stables across the road to Daniel Sutton, who promptly redeveloped the site (see page 346). (fn. 15)

Rebuilding and alterations, 1819–90

Following this settlement, and at a time when the fields

south of the Angel were rapidly disappearing under brick,

the Angel was completely rebuilt in 1819–20. The architect for the replacement building may have been Henry

Rhodes, who was involved with the Coxe family's disposal

of its property in 1817 and who, many years later, was surveyor to the family's estate in Islington. The building lease

for the new inn, for which plans had been settled, was sold

at auction in January 1819 as relating to:

a central post-house and focus for all the communications to

and from the heart of London, the east and west ends of town,

the booking office, and depot for passengers travelling north,

long celebrated as the meeting-house of the salesmen, carriers, and graziers attending Smithfield, the assemblies of

Islington and Pentonville, the public trusts, etc. (fn. 16)

Redevelopment of the site was taken on by Charles Smith,

a builder of Paternoster Row, possibly working in partnership with Henry Minter Fyffe, a grocer and tea-dealer

in Holborn, or relying on him for backing. Fyffe, who was

later active as a developer on the New River Company's

estate, took leases of the inn and a couple of new houses

to the north in 1820. By the following year, when a fresh

lease of the inn itself was made out to Smith by the Coxes,

the building had been sub-let to James Smith, possibly a

relation. (fn. 17)

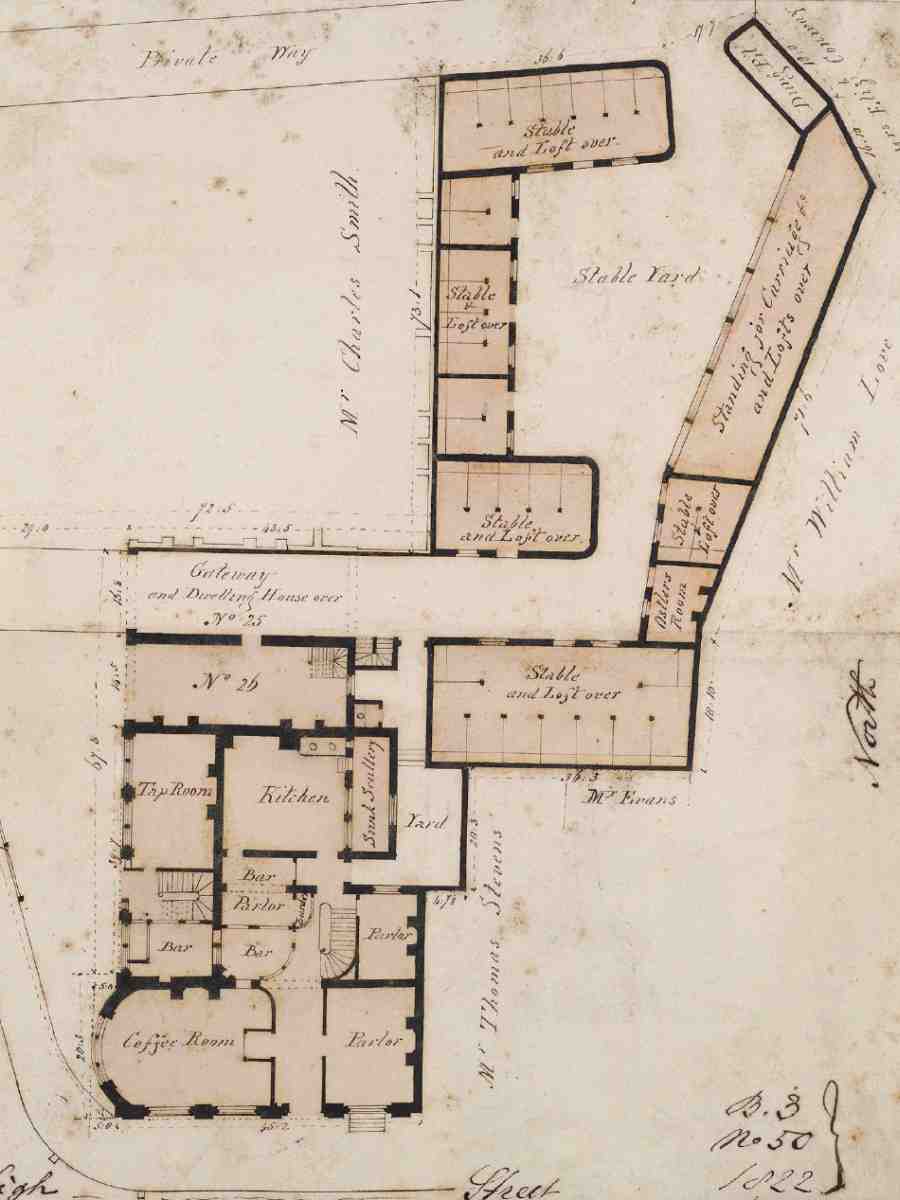

576. The Angel Inn, ground plan in 1822, with stable yard to the north-west

The rebuilding maximized the value of the Angel's site. The size of the inn was reduced, permitting speculative development of outer plots with houses, some with shops—two to the north (see below) and six to the west along the New Road (see page 346). Despite this retrenchment the Angel was still substantial, and had a new stableyard, entered from the New Road (Ills 571, 576). The plain brick inn was itself outwardly distinguished only by a fullheight bow with tripartite sash windows that gave views across Clerkenwell to London. The establishment advertised itself along the High Street front as the 'Angel Inn Tavern and Hotel for Gentlemen and Families'. The main first-floor room above this legend was used as an assembly room, and the tavern faced the New Road (Ill. 577). There were no more Hogarthian courtyard scenes, but the famous post-house continued to be an anchoring location for artists. In 1827 James Pollard painted The Royal Mails at the Angel Inn, Islington, and the inn is mentioned in Oliver Twist as the place where 'London began in earnest'. But, as the railway age began, the census of 1841 recorded only eight resident staff. Management had now passed to the brothers James and John Smith, perhaps sons of the earlier James Smith. (fn. 18)

In the 1850s a visiting American diplomat judged the Angel to have degenerated. The Smiths then failed to gain permission to bring the shopfronts forward on Pentonville Road, as this part of the New Road became in 1857. This improvement was accomplished in 1869–70 by their successor, George J. Jones, along with further works of alteration, all overseen by Bird & Walters, architects, with Williams & Son as builders. The ground floor was opened up with structural iron for plate-glass windows, and the upper storeys were given a lavish helping of ornamental stucco, in architraves, cornices and balustraded parapets that prominently proclaimed the hotel, now a 'well-known rendezvous for omnibuses' (Ill. 578). (fn. 19) These works cannot have had the desired effect as, within a decade, replacement of the hotel with a theatre was being contemplated. Instead, in 1880, the Angel, now promoted to the status of 'one of the great landmarks of London', was refitted internally by the shopfitters Shoolbreds, its wainscoted parlours being replaced with 'glittering plate glass and spacious splendid bars with costly fittings'. This upgrading was carried out for William Henry Baker and Richard Baker, who went on from here to become largescale pub operators. (fn. 20)

577. The Angel Inn, from the south-east c. 1828, also showing Nos 3–17 Islington High Street

Changes in the area's transport regime were manifest in 1883 when the stable-yard was given up and adapted for the horses of the London Street Tramways Co. In 1890 the Angel's assembly room became a billiard room and the Bakers made further improvements, designed by Saville & Martin, architects and carried out by the builders Gould & Brand. Having revived the building's profitability, they sold up in 1896. (fn. 21)

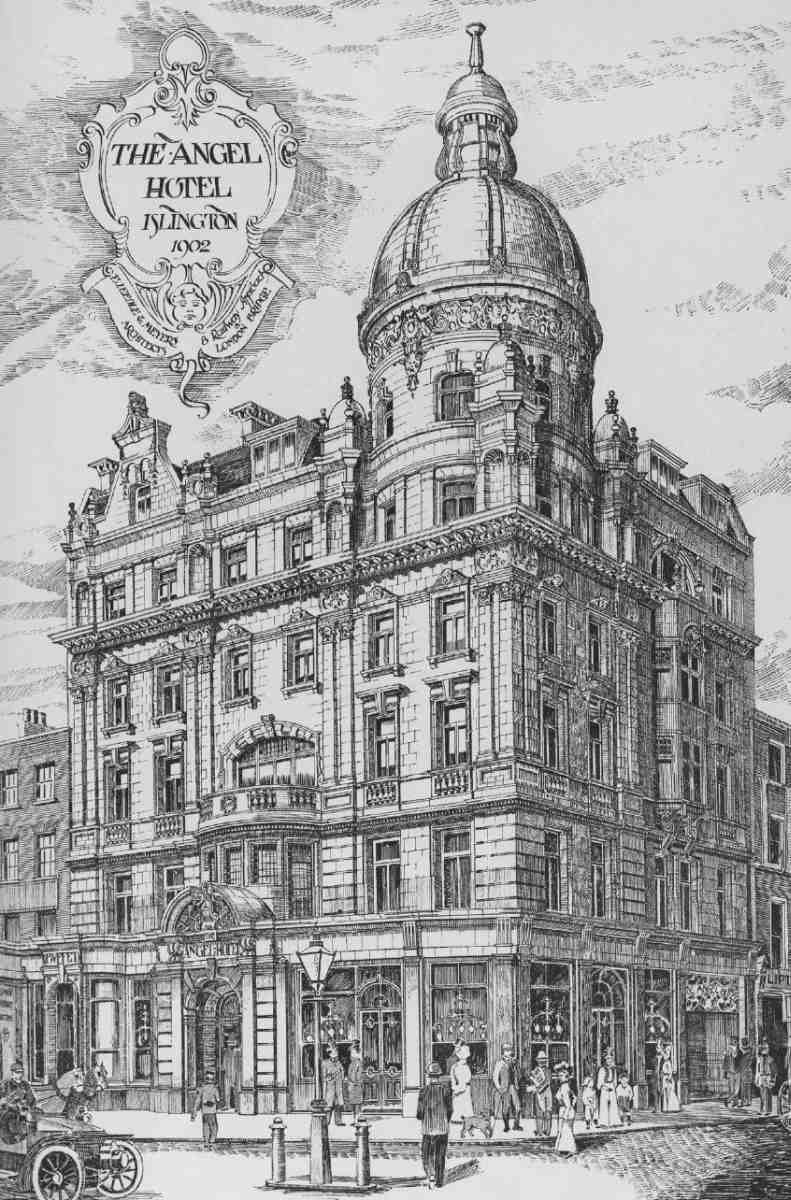

The present building

New owners, the brewers Truman, Hanbury, Buxton & Co. Ltd, soon decided to rebuild what was now acclaimed, a touch extravagantly, as 'the widest-known hostelry in the world'. (fn. 22) Plans were prepared in 1901, approved in 1902, and carried out in 1903. The architects were Frederick James Eedle and Sydney Herbert Meyers, partners since 1890 and established public-house specialists. The building contractors were W. H. Lascelles & Co. of Bunhill Row. Biscuit-coloured Ruabon terracotta facing was supplied by J. C. Edwards, and polished Norwegian granite for the ground floor by Fenning & Co.

578. The Angel Inn, from the south-east in the late 1890s as the Angel Hotel, showing embellishments of 1869–70 and adjacent buildings along Pentonville Road (left) and Islington High Street (right)

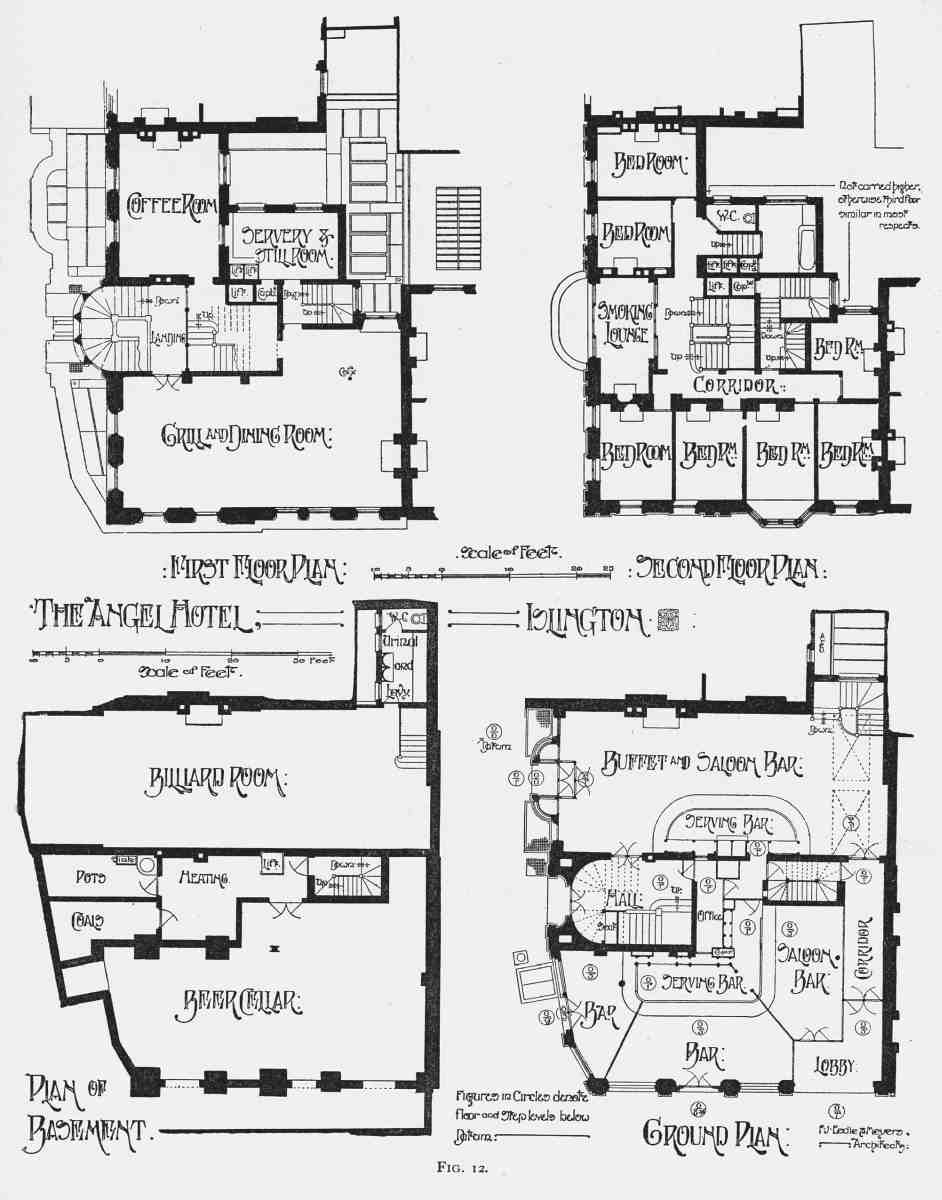

The hilltop corner site was exploited with panache (Ills 579, 581, 583). The lower parts, relatively sober in their classicism with a rusticated first floor below a giant 'Corinthian' pilaster order under a strong cornice, hold down restless Baroque movement around a dome. This has since been a defining feature of the locality, though latterly without its finial. The principal entrance to the new Angel Hotel was to the centre on Pentonville Road, between bar spaces and under an open pediment, richly ornamented around a head, not quite winged, but perhaps meant as an angel. A second-floor balcony bears a panel with the date 1903, and seraphic winged heads top the windows under the cornice. Internally the building incorporates steel construction and, under fireproof floors, ornamental plaster ceilings were made by De Jong & Co. The basement had a three-table billiard room, and there were large eatingrooms on the first floor. Above a green-marble and mahogany-lined principal staircase, long removed, a smoking lounge opened on to the balcony overlooking Pentonville Road. The upper storeys contained twentythree bedrooms, some taken for staff, and just four bathrooms (Ill. 582). (fn. 23)

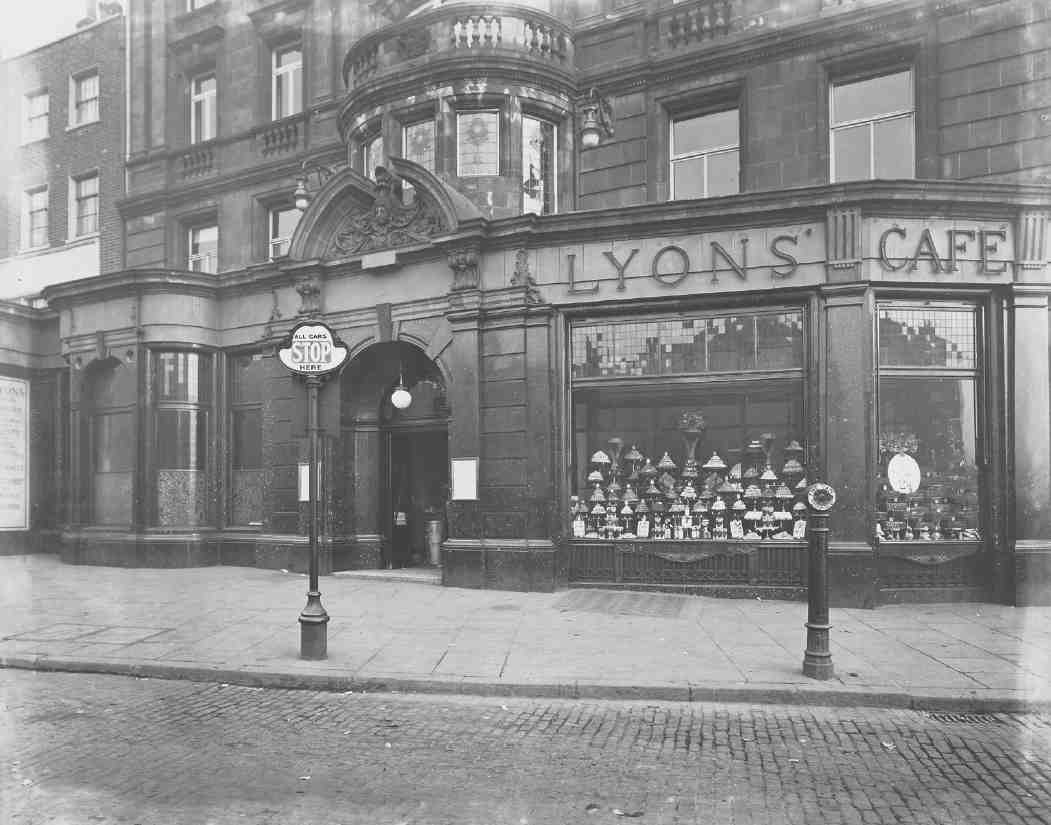

The Angel was once again adapted in 1921–2 when the three lower storeys were made a flagship Lyons' Café. (Despite the corner site, it was not technically a Lyons' 'corner house'.) For this the ground floor was refitted with plate-glass windows and neo-classical bronze trim, by H. H. Martyn & Co. Ltd of Cheltenham (Ill. 580). Arnold Bennett, revisiting the area in 1924, was impressed to find that the Angel had been 'conquered and annexed by the Lyons ideals … Compare its brightness and space to the old Angel's dark stuffiness'. (fn. 24) Here, in this popular café in 1935, it is said, the secretary of Victor Watson, the founder of John Waddington Ltd, decided to include the Angel Islington as one of the lowlier locations on the British version of the Monopoly board. Before Lyons' Angel premises closed in 1959 there was seating for more than 300, in the Angel Grill in the basement, the Angel Café on the ground floor, and a cafeteria on the first floor. (fn. 25)

579. The Angel intersection, c.1919, showing west side of Islington High Street with tower of Angel Cinema

580. South front c. 1922, refitted as Lyons' Café

581. Perspective view, 1902

The Angel Hotel of 1903

582. The Angel Hotel of 1903, floor plans. F. J. Eedle & Meyers, architects

583. The Angel and Islington High Street in 2004

The café was closed and the Angel purchased by the London County Council to allow for demolition in connection with planned road improvements (see above). Up to 1968 the building was used by the City University and its predecessor's Department of Geology. It stood empty thereafter until, following retraction of the road scheme, it was reprieved. A conservation campaign had succeeded, but attempts to introduce a community use failed. The Greater London Council sold the building to the New River Company, as a subsidiary of London Merchant Securities, which, in 1979–82, repaired, refenestrated and refitted it for bank and office use, through Elsom Pack & Roberts, architects, and McLaughlin & Harvey Ltd, contractors. (fn. 26) Since listed and renamed Angel Corner House, it now accommodates a branch of the Co-operative Bank under the head offices of ORC International.

The Peacock

Between the Angel and the White Lion, along the frontage now belonging to Nos 7–17 Islington High Street, there was at least one tavern or alehouse in the late sixteenth century. By the 1670s there were three victuallers (but no inns) in eight relatively small buildings along this stretch. Some time around 1700 these were largely replaced by the new Peacock Inn, which occupied a 67 ft frontage where the present Nos 9–13 stand (Ills 584–6), creating an allbut-solid run of three inns. Remarkably, a part of this building survives at No. 13.

An Islington Council plaque on No. 11 records this as being the site of the Peacock Inn from 1564. The earlier Peacock, however, was further north, on the site of Nos 31 and 33, in a building that had eight hearths in the 1670s when it was run by a widow Liquorish. (fn. 27)

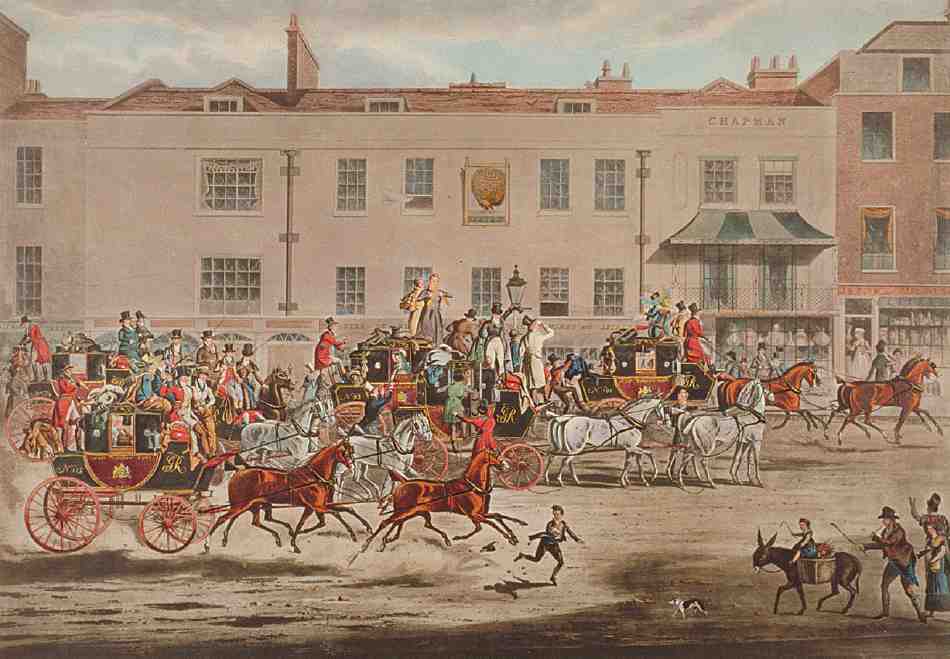

584. The Peacock Inn of c. 1700 with mail coaches departing: aquatint after a painting by James Pollard, 1823. The two northern bays, shown here as altered for a chemist's shop, survive in carcase as No. 13 Islington High Street

585. Nos 5–15 Islington High Street in 2007. No. 7 (left) with campanile, former Angel Cinema, 1911–13; No. 9 of 1891; No. 11, formerly the Peacock Inn of 1931; No. 13 (right of centre), remnant of the Peacock Inn of c. 1700

The Peacock of c. 1700 may have begun with a symmetrical nine-bay (2:5:2) brick front. Other ranges, probably timber-built and relatively short, ran back from either end, that to the north being constrained by an irregular site boundary. Entrance to the inn's narrowly confined yard was off-centre to the south. At No. 13 the front wall, floors (with chamfered binding beams) and forward roofline of c. 1700 still survive. From the original roof there is much of the substantial north end truss, a collared assembly of halved principal rafters, with butt purlins. A number of common rafters also remain in situ and elsewhere mortise positions indicate the former presence of a dormer window, already absent in 1823, and the junction with the back-range roof that Pollard showed as having a slightly higher ridge. The back wall was rebuilt in brick in the twentieth century. (fn. 28)

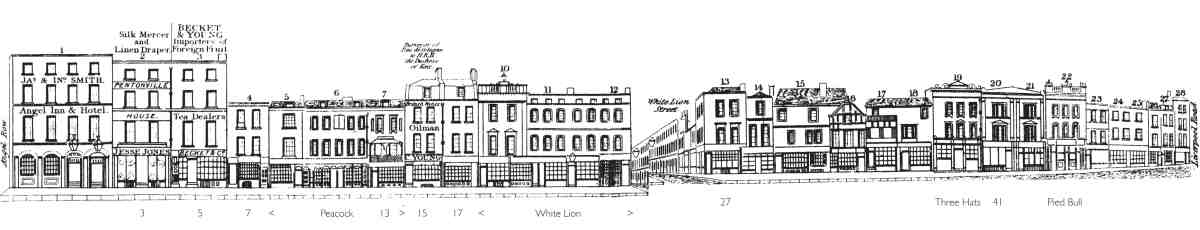

586. Islington High Street, west side, south (left) and north (right) of White Lion Street, from Tallis's London Street Views, 1838–40. Modern numbering and indications of the extent of the former inns have been added. Nos 13, 27, 39 and 41 survive

The Peacock perhaps had difficulty establishing itself between its bigger neighbours, and may already have been scaled down by the 1760s, when it had a rateable value just a quarter to a third that of the Angel; the yard, which incorporated a skittle ground, had become inhabited as Peacock Court. By 1807 the inn had shrunk to occupy just the central five bays (Nos 11 and 11A), with John Todd, china-dealer (later cheesemonger), at No. 9 (perhaps rebuilt as a single bay), and Samuel Birch at No. 13, succeeded by George Chapman, chemist, in 1809. The freehold remained undivided. (fn. 29)

By the time of Pollard's painting, the whole of this front had been stuccoed. The present appearance of the front of No. 13, with its incised panels and upper-storey architraves, is perhaps largely due to Chapman's arrival in 1809. Despite its reduced size the Peacock was, as Pollard's painting indicates, a well-known address in the early nineteenth century—'a house we all stop at', as a coachman of the Chester Mail witnessed at the Old Bailey in 1813. (fn. 30) This fame as a stopping place was attested later on, in Nicholas Nickleby and Tom Brown's Schooldays. By the 1850s the old 'long-roofed and capacious' building had long been divided, only part remaining in use as an inn. (fn. 31)

In 1857 the reduced inn was rebuilt as a substantially taller, three-storey public house with a four-bay front. This was extensively upgraded in 1888–9, (fn. 32) and in 1931 it was replaced by the present yet taller, three-bay building at Nos 11 and 11A—erected, as the rainwater hoppers record, for Higgins & Co. Ltd, freeholders, and P. Goodrich, licensee. The entrance had a large encaustic-tile representation of 'The Triumph of the Emperor Aurelian after the Conquest of Palmyra'. (fn. 33) The Peacock closed in 1962. At No. 13 the shopfront was replaced in 1932 for H. Samuel, jewellers and long-standing occupants, by which time the first-floor veranda was long gone and slates had replaced tiles on the roof. (fn. 34)

The White Lion

The White Lion Inn appears on the late sixteenth-century map, by the third sign from the south, as already then having a cross-range (Ill. 572). In the 1660s and 70s, when it was assessed as having twenty-three hearths, the same number as the Angel, the innkeeper here was Christopher Busbee, who also held a yard with stables and coach houses, as well as bowling greens to the west, where Busby's Folly stood (see page 327). The inn and its two acres were part of the Wood estate that passed to Henry Penton in 1710, much of which was then occupied by John Oakley as White Lion Farm. (fn. 35)

It was perhaps Oakley and Penton who rebuilt the White Lion Inn in 1714. Evidence for its early appearance is thin, but it was depicted in the 1830s as having a ninebay brick front range, 63 ft long (Ill. 586). The two southernmost bays were articulated by a giant order of Corinthian pilasters—suggesting an end pavilion, the pair to which must have been lost when White Lion Street was laid out in the late 1770s. The attic over the central bays was perhaps an addition. The inn was U-shaped on plan, with back ranges, perhaps galleried, enclosing part of a yard, entered through the front range and extending much further west and south. Between two first-floor windows (perhaps over the yard entrance) was the inn sign, a panel with a rampant lion in high relief, which was re-mounted to face White Lion Street when the inn was rebuilt at the end of the nineteenth century. It is now obscured by thick paint, but a photograph taken about the time of the rebuilding shows the lion to have been the work of a virtuoso sculptor. Together with the background panel, which carries the date 1714 and the monogram of Henry Penton, it is almost certainly executed in stone (Ills 587, 588). (fn. 36)

587. The former White Lion of 1898, Nos 23–25 Islington High Street, in 2007. On the White Lion Street flank (right), the lion reliefs of 1714 and 1898 at first-floor level

588. The White Lion Inn, sign of 1714, photographed for the London Survey Committee before the rebuilding of 1898

Like the Angel and the Peacock, the White Lion was frequented by cattle drovers. In 1767 it was leased to Joseph Barron, perhaps the same Joseph Barron who decades earlier had tried to make a go of the New Inn (see above). With the inn were barns and stables, two 'little messuages', meadowland and cattle layers. (fn. 37) Barron was followed by Joseph Ridgway, a Clerkenwell grocer, who took out a 79-year lease of the inn and the yard from 1788. The formation of White Lion Street permitted side access to the yard, and other development there, including the building of several small houses (see pages 384–5). Ridgway divided the inn fronting the High Street into three properties, letting those to the south and centre as shops, blocking up the old yard entrance, and keeping the public house to the north himself. Christopher Gapp took over in 1809, to be succeeded by Charles James Gapp into the 1870s. By 1841 four shops had been squeezed in alongside the White Lion (Ill. 586), for a hatter, a tobacconist, a hosier and glover and, to the south, for Samuel Mayers, biscuit baker, whose name appeared above a balustraded parapet and under an urn—seemingly grandiose stucco embellishment of the former inn's end pavilion. This front (No. 19) was subsequently remade with a pediment in 1878–9. (fn. 38)

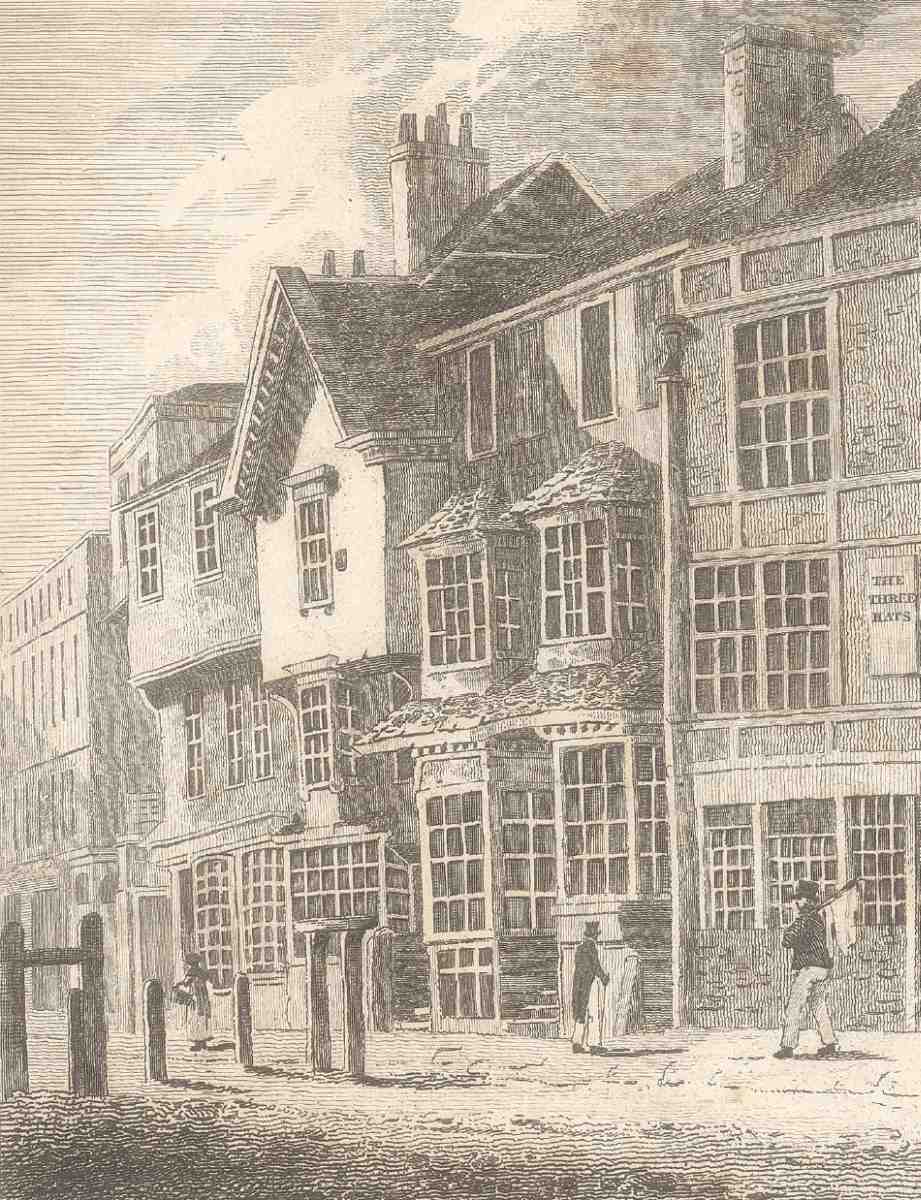

589. Timber-framed buildings on the site of Nos 29–37 Islington High Street, drawn by T. H. Shepherd, c. 1820. On the right is the Three Hats

590. The Pied Bull, No. 1 Liverpool Road, in 1933. Sidney C. Clark, architect, 1931–2

591. Left to right: Nos 39–43 Islington High Street and 1–13 Liverpool Road in 2007. No. 39 is the former Three Hats, rebuilt c. 1840, with later gable

The White Lion (Nos 23–25 Islington High Street) was rebuilt in 1897–8 for Eli Perry, victualler of Oakley Square, Camden Town. It was set back from the old building line to permit the end of White Lion Street to be widened. The lion panel of 1714 was reset along this side, supplemented by another bearing the date 1898 (Ill. 587). The pub front was given polished granite pilasters, the lines of which continue up through three more red-brick storeys to give the somewhat Flemish gabled front strong vertical emphasis. There was mosaic flooring in what was said to be a luxurious interior. (fn. 39) In the later 1960s the White Lion closed and was purchased by the Greater London Council for proposed road-widening. In 1984 it was bought by Land & Equity Group, renovated, and made into offices over a bank. It is now called Lion House. (fn. 40)

The Black Boy and Three Hats

Beyond the sign of the early Peacock on the Elizabethan map, the fifth sign denotes another establishment with a cross-range. Standing on part of the Wood (later Penton) estate, this was known as the Black Boy in the 1730s and then as the Black Boy and Three Hats in the 1750s, when it was leased by John Aishman, glazier and victualler, who also held the White Lion for a time. (fn. 41) It gained a reputation for staging equestrian acrobatics in its grounds in the fields behind; an exhibition in 1766 was reportedly attended by a crowd of hundreds that included the Duke of York; in 1770 it was advertising the 'manly diversion' of 'Double Stick', with a two-guinea prize to 'those who break the most heads'. (fn. 42) A tea garden to the rear survived until the late nineteenth century. By 1820 the house had a flat but curiously panelled front, presumably of brick (Ill. 589). It was then known simply as the Three Hats, that name perhaps deriving from the Northampton family arms, which include three helmets.

The Three Hats was among a number of old buildings on the High Street destroyed by fire in 1839. (fn. 43) It was rebuilt and the stuccoed front, at least, of this three-bay, three-storey structure seems to survive (No. 39 Islington High Street). It closed as a public house in the 1850s, and was converted to shop use. From the early 1880s a Post & Money Order Office and Savings Bank shared the premises with William Alpheus Higgs & Co., grocers and tea importers, who appear to have added the shaped gable in 1894, to measure up with those put up in the preceding decade on neighbouring buildings to the south. The building later became a branch of the London & County Bank, then of the Midland Bank. (fn. 44)

The Pied Bull

The northernmost of the hostelries shown on the late sixteenth-century map (Ill. 572) was the Pied Bull. Like the Three Hats this was burned in 1839 and rebuilt (Ill. 586). (fn. 45) It was again rebuilt in 1931–2, in the shape of a neo-Tudor representation of the ideal English 'inn'—its design showing a high awareness of type, if not of specific local precedent. Consciously or otherwise, it produced a nostalgic evocation of the form and appearance of earlier buildings here (Ills 590, 591). This public house (No. 1 Liverpool Road) was designed for Hoare & Co. by Sidney C. Clark, an architect who specialized in buildings of this genre. The builders were Courtney & Fairbairn Ltd. It was given a stone-faced lower storey and upper storeys of Binfield brick, with a jettied half-timbered gable bearing patterned timbers and a projecting inn sign. (fn. 46) The Pied Bull became a music venue by the 1980s, but has closed since the early 1990s, and is now a branch of the Halifax Building Society, with offices above. (fn. 47)

592. The Agricultural Hotel, No. 13 Liverpool Road, in 1998. Finch Hill & Paraire, architects, 1862–3

The Agricultural Hotel

As Chapel Market developed into a shopping street, the late eighteenth-century buildings at its northern corner with Liverpool Road were rebuilt in 1862–3, ostensibly as a house and shop, for Henry Penny, bootmaker, but in the event as the Agricultural Hotel, No. 13 Liverpool Road. Finch Hill & Paraire were the architects. Stuccoed and with a curved corner, the building incorporates cast-iron columns in front of its ground-floor windows (Ill. 592). The formation and name of this new public house reflect the proximity of the Royal Agricultural Hall, a short distance up Liverpool Road and built in 1861–2 for the Smithfield Club to exhibit livestock and agricultural improvements. This late arrival, and last survival, among this stretch of public houses, therefore represents in both origin and name the mainstay of the custom that had sustained the local inns for centuries. In 1893 the premises were extended and altered along Chapel Market to include the building then known as No. 43½. (fn. 48)

Other buildings: Islington High Street

Nos 3–5. As part of the redevelopment of the seventeenth-century Angel in 1819–20, Charles Smith gave over the northern part of the site to two new shop-houses (Ills 577, 586). Like the inn itself, these were at once leased to Henry Minter Fyffe, who sub-let the southern house to a haberdasher. (fn. 49) Both buildings were occupied by Liptons in the 1890s. The site was redeveloped again in 1928 with a warehouse and shop for the Saxone Shoe Co., designed by J. Reeve Young and still perpetuating the building line of the seventeenth-century inn (Ill. 583). A new shopfront was added in 1936–7, for premises that remained Saxone's into the 1990s. The ground floor has since housed a J. D. Wetherspoon pub called the Angel, with offices above. (fn. 50)

593. Islington High Street, west side from the north, 1930s

No. 7 was rebuilt before the First World War as the entrance to the Angel Picture Theatre (see Angel Cinema, below.)

No. 9, once part of the Peacock inn site, was rebuilt to its present form in 1891, for Hudson Brothers, cheesemongers and provision merchants, by William Shepherd, builder (Ill. 585). (fn. 51)

The site of Nos 15–17 was until recently occupied by a pair of shop-houses of c. 1800 (Ill. 586), when this was still the property of the manor of St John of Jerusalem. It was redeveloped in 1993–5 for Abbey National plc, which put up a rectilinear brick-faced block for its own use, with Perry Associates as architects, working with the Miller Partnership, and Wilmott Dixon Symes Ltd as building contractors. (fn. 52)

The two-storey building at Nos 19–21, which occupies part of the old White Lion site, was built in 1954–5. The architect was D. E. Harrington, and it was first occupied by Civic television dealers. (fn. 53)

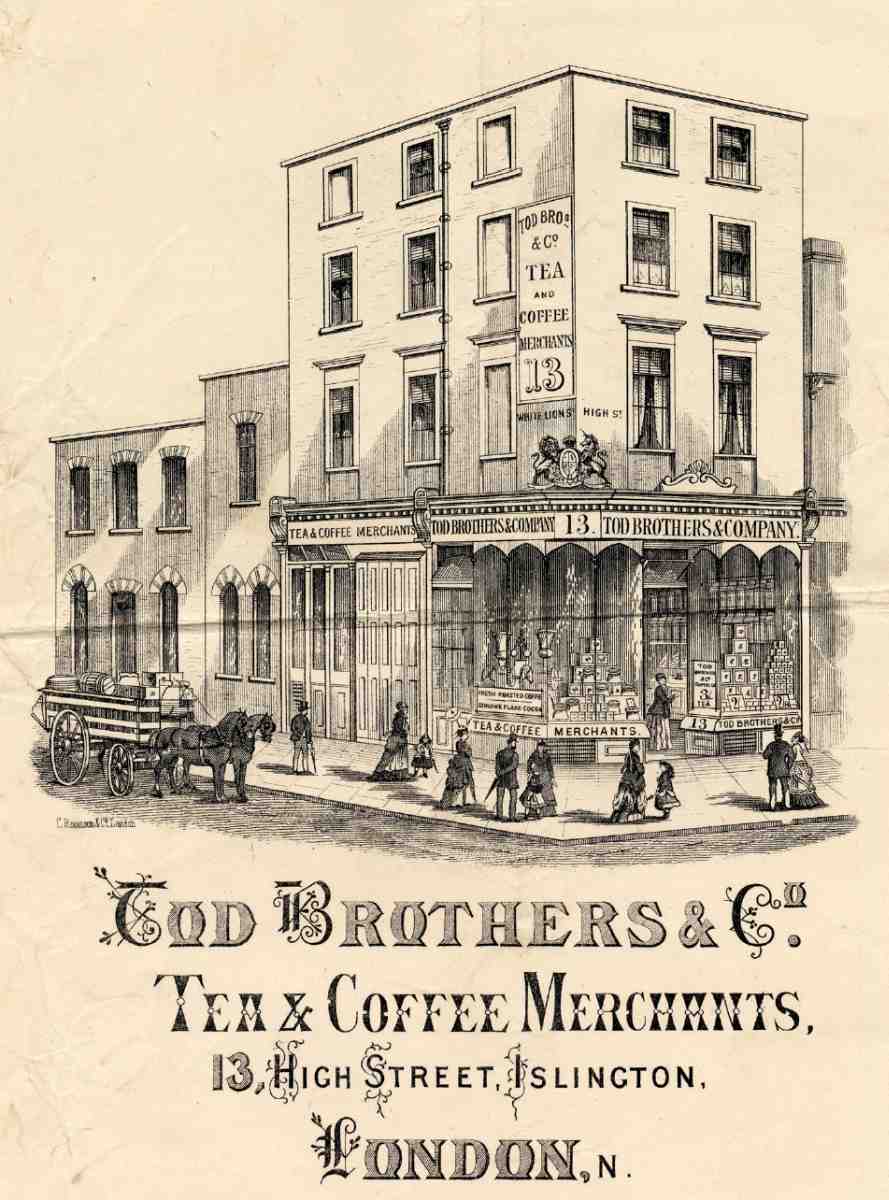

The site of Nos 27 and 29 Islington High Street was that of a 'great edifice' by the early seventeenth century when it was home to Sir Robert Wood, the owner of what later became the Penton estate. This was perhaps occupied by Sir James Edwards in the 1670s and then assessed for twenty hearths. (fn. 54) There was a jettied front and ornamental interiors of note, including a stone chimneypiece that depicted Orpheus. In the eighteenth century it came to be used as a ladies' school, and then, after White Lion Street was made, was divided and used as two shop-houses. (fn. 55) That to the south, No. 27, was probably rebuilt in the 1830s for Alexander Samuel Braden, tea dealer, who raised it a further storey in 1852. This addition, by John Ashton, builder, was so well done as to be scarcely evident as such, though much of the flank wall has been remade since. (Ills 586, 594, 595). (fn. 56)

The other, No. 29, was rebuilt in 1883–4 for Alfred Goad, watchmaker, as a shop-house for his own occupation. His builder was J. Sharman. Goad did not stint, packing a great deal of incident into five storeys on his narrow frontage, including a delightful arched balcony on the third floor, and the monogram AG&S, for Alfred Goad & Sons. The whole project was, no doubt, a response to the adjoining development to the north. (fn. 57)

Until the late nineteenth century the frontage at the present Nos 31–37 was occupied by early timber buildings (Ill. 594), standing hard by the Islington turnpike gates and the twin octagonal tollhouses of 1808 on either side of the Clerkenwell—Islington parish boundary. One of these old buildings, jettied and with a cross-range, had been the Peacock until replaced by a new building further south around 1700 (see above). Another had projecting bays. To the rear was Field Court, a row of six early eighteenth-century cottages, probably built by John Field. (fn. 58)

All this was replaced in 1881–3 by Leverett & Frye Ltd, Irish grocers and 'italian warehousemen', who had a shop at No. 31. The speculation provided shops with artisans' dwellings above and behind. The architect, for F. C. Frye, was Arthur Vernon, and William Woodbridge of Maidenhead was the builder. The tall triple-gabled front range lifted the scale of this section of the High Street. Between the polished granite and plate-glass windows of the shopfronts a central archway led through to a remade courtyard, Frye's Buildings, giving access to twelve tworoom tenements. (fn. 59) The back buildings were cleared in the 1940s and the front block was rebuilt in 1986–7 by Greater London Properties (Islington) Ltd as offices over shops, with the 1880s façade rebuilt in facsimile. The building is now known as Lancaster House. (fn. 60)

594. Islington High Street, block north of White Lion Street, c. 1843. The turnpike gate and the junction between Liverpool Road and Upper Street are seen to right

The fire of 1839 that destroyed the Three Hats (see above) began in a hairdresser's shop in one of two small buildings on the site of Nos 41 and 43 (Ill. 589), which were then rebuilt as a symmetrical pair. The first occupants of the new shops were a laceman at No. 41 and a linen-draper at No. 43. (fn. 61) No. 41 retains a robust pair of shop-facia consoles with lion heads, possibly from a refit of 1855. (fn. 62) From 1898 No. 43 was an early Sainsbury's outlet, a game branch here succeeding that established at No. 51 Chapel Market in 1887. It was rebuilt for Sainsbury's in 1932 by W. T. Yates, to the designs of Hamblin, Fox & Baily. (fn. 63)

No. 7, former Angel Cinema

The site of No. 7, belonging successively to the Wood and Penton families, was redeveloped about 1790 with a threestorey shop-house, following a lease to Joseph Ridgway. (fn. 64) This eventually came to be occupied by the Funland Amusement Arcade, which was replaced in 1911–13 by the entrance to the Angel Picture Theatre, whose large auditorium lay behind on the site of White Lion Buildings, previously White Lion Yard.

595. No. 27 (formerly No. 13) Islington High Street at corner of White Lion Street. Trade card of c. 1870

596. Sainsbury's, Liverpool Road, looking south from Tolpuddle Street corner, 2007

An early purpose-built cinema, this was the most ambitious of several cinemas in the area about this time. It was erected for the Social Service Educative Entertainment Co. Ltd, which was set up in 1912, after the site had been secured, by Abraham Davis, the East London Jewish builder, developer and founder of the London Housing Society. With him in the venture were his brother and frequent partner, Ralph Davis, and Henry Mills, mayor of Islington and secretary to the National Sunday League. Its purpose was 'to provide educational recreation by means of popular entertainments of a refined and wholesome character, which it is hoped will tend to elevate and instruct the masses', through 'attractive Halls in the more congested parts of London'. (fn. 65) Preliminary plans were drawn up in 1911 by Harry Harrington, architect, but the detailed designs were the work of H. Courtenay Constantine, with W. G. C. Hawtayne as consulting engineer for what was a largely steel-framed structure. (fn. 66) The building-site hoarding told the public that the proprietors aimed to revive 'merrie, merrie Islington', and the completed building was welcomed as 'a temple beautiful in the realm of picture palaces'. (fn. 67) The films shown were intended to be educational and enlightening as well as entertaining, showing 'distant countries … the wonderful growth of flowers [and] all the various arts and industries'. (fn. 68)

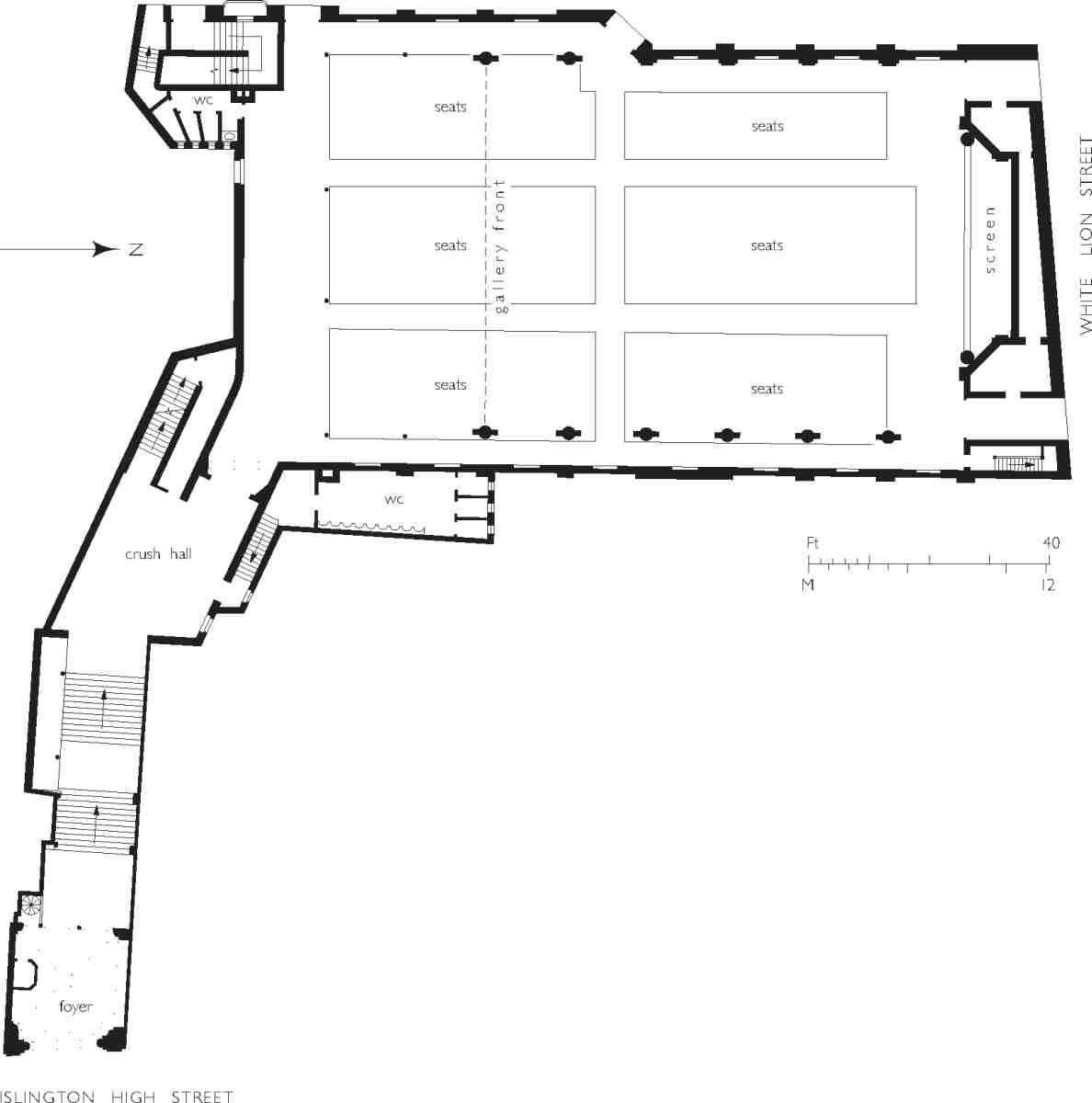

All that survives of what came to be known as the Angel Cinema are its stuccoed entrance pavilion and bold, fruitily Baroque tower—with its copper-domed campanile, taller than the Angel at 100 ft (Ills 579, 583, 593). A drawing by Constantine shows a statue in the secondstage niche and other enrichments, but these were perhaps never executed. (fn. 69) This was the most luxurious cinema in Clerkenwell and Islington. It originally seated 1,448 in the hall and balcony, with room for 490 more standing (Ill. 597). The interior decoration was in white relieved by Pompeian red, with black-and-white marble floors and stairs, stained-glass windows, 'richly draped hangings' and tip-up seating throughout upholstered in plush. Under the copper roof was a plaster ceiling in the form of a coffered vault (Ill. 598). (fn. 70) The cinema had its own orchestra and an organ built by Hill, Norman & Beard. (fn. 71)

The cinema's success was such that there were immediate plans for a second hall to the west along White Lion Street, for up to 1,750 more patrons. Davis put forward alternative schemes by Constantine until 1919, when approval was gained, but the extension was not carried out. Later plans for a new entrance at Nos 19 and 21 Islington High Street were also abandoned, in favour of an extension in 1925–6 along White Lion Street and behind the High Street properties. From this time, except during the war, the main entrance was on White Lion Street; only those with seats in the balcony used the High Street entrance. The cinema was acquired by Gaumont in 1926 and altered for talkies in 1929. From 1963 it was an Odeon, but only until 1972 when it closed. (fn. 72)

597, 598. Angel Cinema, No. 7 Islington High Street, H. Courtenay Constantine, architect, 1911–13. Ground plan in 1913 and interior from the north-east in 1972

Demolition of the auditorium followed soon after. The former entrance pavilion and its tower were restored in the 1990s after gaining listed-building status, and now house a coffee shop. The site of the cinema has reverted to being a yard, with buildings of the 1980s facing White Lion Street and on the west side, the latter housing the Nadell Patisserie Factory. On the east side of the yard is a midnineteenth century workshop that may have originated as an outbuilding to the Peacock.

Liverpool Road

Islington's Back Road began at the Pied Bull public house. The Clerkenwell frontage up to what is now Chapel Market was first built up during the seventeenth century, and was at least partially redeveloped in the 1780s as Pentonville was being laid out behind. The frontage further north up to present-day Tolpuddle Street, which had been open ground as Joseph Barron's cattle layers, was developed from about 1771 to 1796 with twenty-two houses comprising Mount Row. Early on there was backbuilding in small courts. The developers included George Clements, a Clerkenwell carpenter, who built Clements Buildings, a row of six houses of 1772–3 about where Woolworth's (No. 17) now stands. (fn. 73)

The Back Road became Liverpool Road in 1826, presumably taking its name from Lord Liverpool, the Prime Minister. The frontage south of Chapel Market was redeveloped in the early 1930s, that to the north of the Agricultural Hotel in the 1980s and 1990s in work that harked back to the Angel Planning Study of 1971.

Nos 3–7. It was here that the local branch of Marks & Spencer Ltd began in 1914, with a penny bazaar at No. 5. The present building was put up in 1930, by which time the company had begun building its stores to a standard formula. The architects were Percy H. Clarke & Son, and the builders Bovis Ltd, Marks & Spencer's usual choice (Ill. 591). It retains panelled ceiling decoration. Offices adjoined at No. 47 Chapel Market, but it was not until 1964 that the store was extended along that street (see page 398). (fn. 74)

Nos 9 and 11. Henry Kennett, a grocer and oilman, who had rebuilt No. 46 Chapel Street (Market) about 1896, had plans to rebuild here from 1908, and designs were drawn up for him by Tasker & Wright, architects. (fn. 75) However, this project was not carried forward until 1929 when the scheme was redesigned for Kennett by (Herbert A.) Wright, who had built up an extensive commercial practice in the Clerkenwell—Pentonville area. (fn. 76)

Nos 25–29. In 1929 F. W. Woolworth & Co. Ltd built one of its characteristic neo-Georgian stores at this address, a large L-shaped building with a second frontage at Nos 40–43 Chapel Market. (fn. 77) In 1991–3 the Liverpool Road arm was rebuilt to the south, at No. 17, making room for an extension to Sainsbury's on the corner of Tolpuddle Street. The new Woolworths block, designed by Watts & Partners for Chartwell Land, has a plain front, the upper parts in darkish brick. No. 15, a single shop unit on the site of two shop—houses, was also part of this redevelopment. Variety in the street frontage was maintained through the use there of paler, pinker bricks in a sober unornamented neo-Georgian manner. (fn. 78)

Nos 25–41 is a Sainsbury's supermarket of 1984–5, and the successor to their several smaller shops locally (Ill. 596). That scale of commerce was, however, left behind, and the company's in-house architects treated the densely grained urban site as if it was an out-of-town precinct. The large car park adjoining reinforces that impression. When new the store covered 25,000sq.ft with 'a dismal brick-clad shed'. (fn. 79) In 1992–3 it was extended to the south, to designs by John Living & Morrison Rose, to provide extra sales space, storage and staff facilities. (fn. 80)