Survey of London: Volume 47, Northern Clerkenwell and Pentonville. Originally published by London County Council, London, 2008.

This free content was digitised by double rekeying. All rights reserved.

'Lloyd Baker Estate', in Survey of London: Volume 47, Northern Clerkenwell and Pentonville, ed. Philip Temple (London, 2008), British History Online https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vol47/pp264-297 [accessed 9 February 2025].

'Lloyd Baker Estate', in Survey of London: Volume 47, Northern Clerkenwell and Pentonville. Edited by Philip Temple (London, 2008), British History Online, accessed February 9, 2025, https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vol47/pp264-297.

"Lloyd Baker Estate". Survey of London: Volume 47, Northern Clerkenwell and Pentonville. Ed. Philip Temple (London, 2008), British History Online. Web. 9 February 2025. https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vol47/pp264-297.

In this section

CHAPTER XI. Lloyd Baker Estate

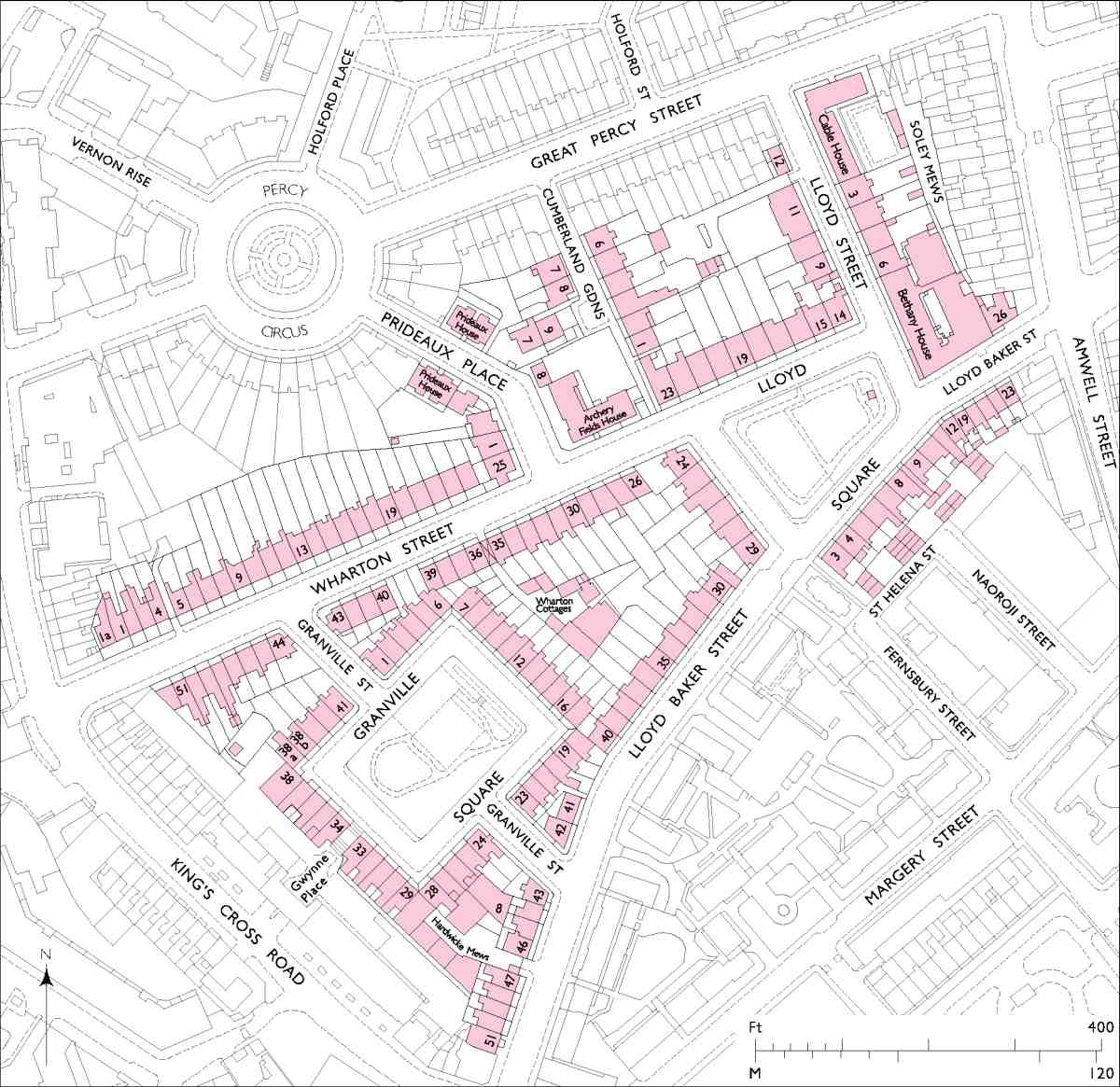

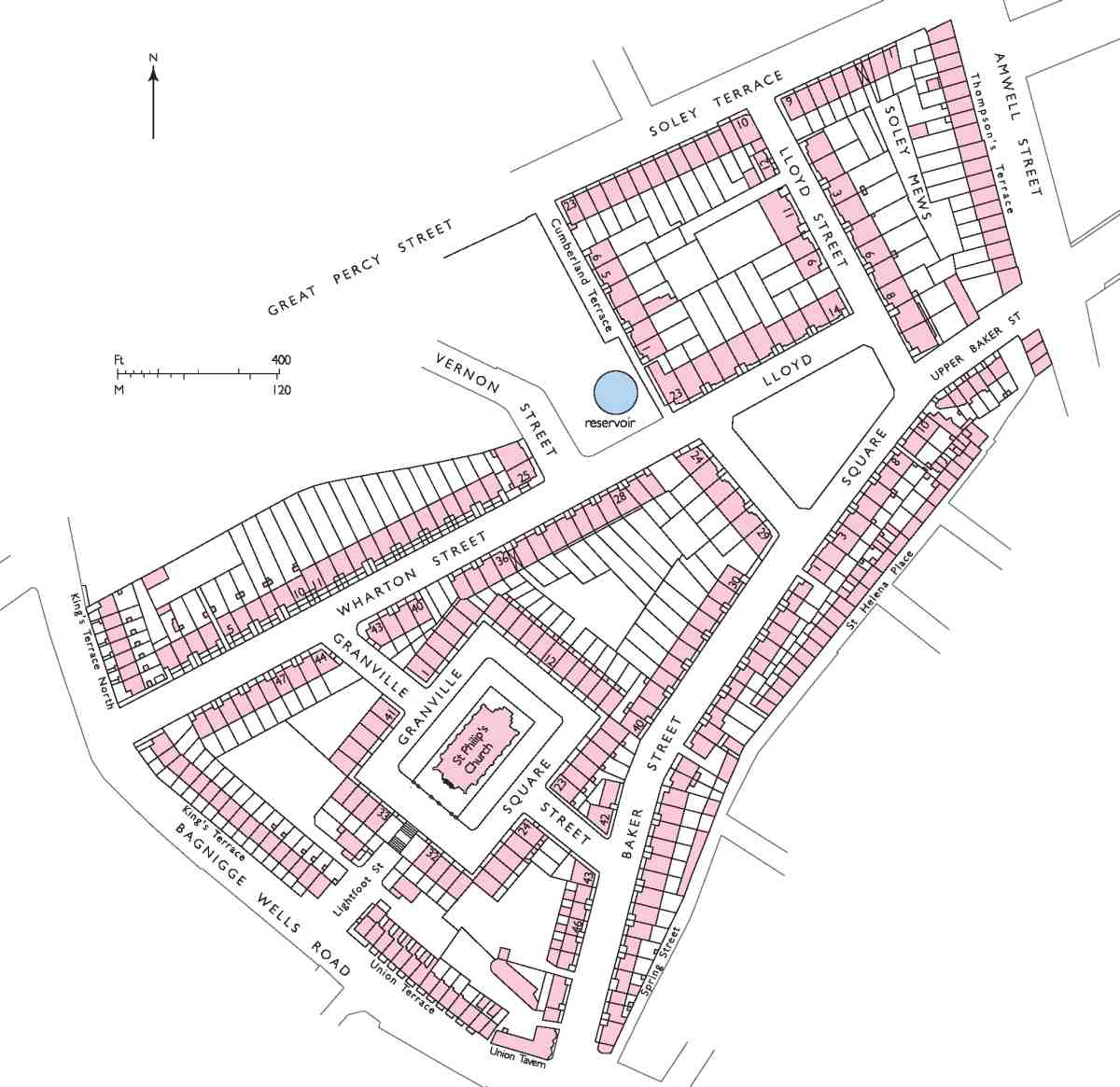

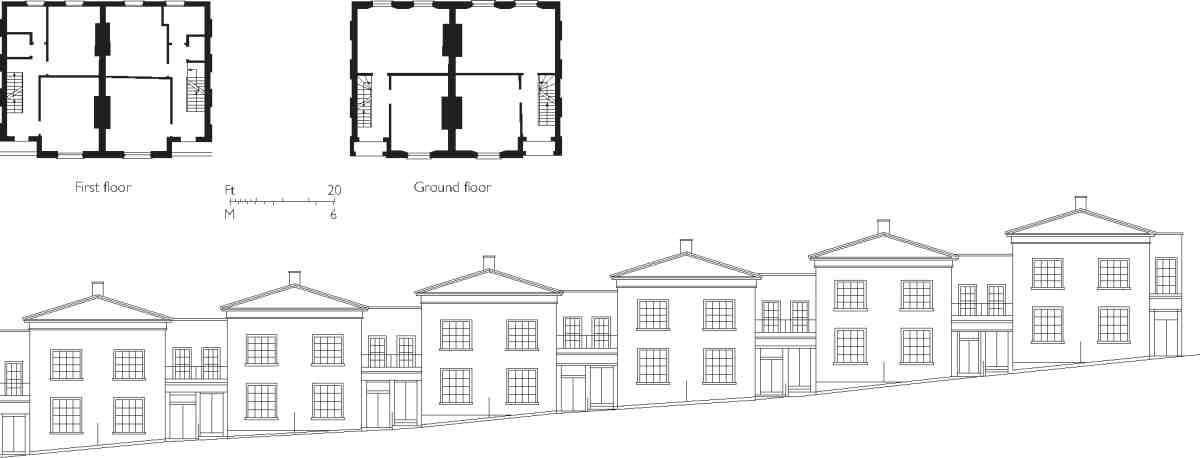

346. Lloyd Square and Granville Square area

Few, if any, of the many small estates around central

London have so distinctive and memorable an architectural stamp as the former Lloyd Baker estate, laid out

between about 1820 and the early 1840s on the steeply

sloping ground between King's Cross Road and Amwell

Street (Ills 3468). Adorned by pairs of small pedimented

villas composed picturesquely on the rising ground, the

idiosyncrasy of the estate has long been noted and sometimes mocked. Arthur Machen, in his novel The Three

Impostors (1895), called it 'decorous, but hideous in the

extreme':

The builder, some one lost in the deep gloom of the early

'twenties, had conceived the idea of twin villas in grey brick,

shaped in a manner to recall the outlines of the Parthenon,

each with its form broadly marked with raised bands of stucco

and for a further surprise the hill was crowned with an

irregular plot of grass and fading trees, called a square, and

here again the Parthenon-motive had persisted.

Seventy years later, in an echo of Machen's sentiments, Ian Nairn described the pedimented pairs 'dutifully climbing Lloyd Baker Street, two by two', as 'like a parody of the Greek Revival'. (fn. 1)

347. Former Lloyd Baker estate from the air in August 2001, looking west. Amwell Street in left foreground, Lloyd Square left of centre and Granville Square at top, between Lloyd Baker Street (left) and Wharton Street (right)

348. Lloyd Baker estate in 1843, on completion of original development

These villas have certainly had their admirers too. The architect Hugh Casson, for instance, called Lloyd Square 'one of the nicest squares in London The houses stand linked arm-in-arm, so to speak, guarding their well-kept simplicity from the roar of Rosebery Avenue and King's Cross Road Full marks anyway to those who built Lloyd Square and to the family that have looked after it so well and for so long'. (fn. 2) By contrast, the lower portions of the estate between Granville Square and King's Cross Road, built up with conventional terraces, have seldom elicited respect. That is the district where Arnold Bennett set Riceyman Steps (1923), his vivid and exactly documented late novel of impoverished Clerkenwell lives.

This chapter covers developments on the core of the Lloyd Baker estate, but not those on the family's separate and smaller holdings around Sadler's Wells and Islington Spa, described in Chapters III and V. For reasons of topographical logic, a few New River Company properties are addressed in this chapter, while the south side of Lloyd Baker Street, Soley Terrace (now Nos 2872 Great Percy Street), Thompson's Terrace (now Nos 2765 Amwell Street), Nos 274 King's Cross Road and Gwynne Place, all built on Lloyd Baker land, are dealt with in Chapters VIII, IX and XII.

Ownership and descent

At the start of the nineteenth century the Lloyd Baker estate in Clerkenwell comprised two separate blocks of property. One, on the east side of the parish, adjoining or near St John Street, was a little Cockaigne of places for entertainment and refreshment, including Sadler's Wells Theatre. The other, western block, destined for development between 1819 and 1843, forms the subject of this chapter. It then consisted of two adjoining fields: the larger, of ten acres, known as Black Mary's Field, and the smaller, under six acres, Robin Hood's Field. Black Mary's Field was shaped like a truncated triangle and had a longish frontage to Bagnigge Wells (now King's Cross) Road, while the squarer Robin Hood's Field was bounded on the east by a footpath along the line of what is now Amwell Street (see Ill. 239 on page 187).

In medieval times these two fields had been portions of one large field of some 150 acres called the Commandery Mantells, which Gilbert Foliot had given to the priory of St John in Clerkenwell during the reign of Henry II. (fn. 3) After the dissolution of the priory in 1540 the Commandery Mantells, by then divided into three, passed to the Crown. Elizabeth I granted the land to Thomas, Duke of Norfolk, who subsequently disposed of a large area to Nicholas Backhouse of London, grocer. In terms of the modern street layout this 80-acre area was bounded on its east, north and west sides by St John Street, Pentonville Road and King's Cross Road, while its southern limit ran from west to east just south of Lloyd Baker Street, before turning south approximately along Amwell Street and then east along Myddelton Street.

In the early seventeenth century Backhouse's son and heir, Samuel, sold some land on the east side to the newly formed New River Company for their main reservoir and 'water house'New River Head (see page 168). The original conveyance having been mislaid, it was re-conveyed to the company by Samuel's son, Sir John Backhouse, in 1639. This second conveyance also allowed the company to lay its water pipes over the adjoining fields, otherwise used for pasturing. (fn. 4) During the seventeenth century the larger fields were gradually subdivided, and at some point these enclosures resulted in the formation of Black Mary's Field and Robin Hood's Field.

Though more land was sold to the New River Company in the seventeenth century, the core of the property descended through the Backhouse family to Flower Backhouse, daughter of the Rosicrucian philosopher William Backhouse, who in 1666 took as her second husband Henry Hyde, future 2nd Earl of Clarendon. From her it passed to her godson, Dr William Lloyd, Chancellor of the diocese of Worcester, whose father, Bishop Lloyd of Worcester, was one of James II's 'Seven Bishops'. On William's death in 1719 it was inherited by his son, the Rev. John Lloyd, rector of Ryton near Gateshead, County Durham. (fn. 5)

Disputes between John Lloyd and the New River Company resulted in his selling most of the land to the company in 1744. (fn. 6) Exempted from this sale were Black Mary's Field and Robin Hood's Field, Sadler's Wells Theatre, the pleasure gardens called New Tunbridge Wells or Islington Spa, the Sir Hugh Myddelton's Head public house, and the so-called 'Breakfasting House' (see pages 859). All these descended to John Lloyd's eldest daughter, Katherine. After her death they passed to her surviving sister, Mary, who in the late 1770s married their cousin, the Rev. William Baker, later of Stout's Hill near Uley in Gloucestershire. After his marriage William Baker added Lloyd to his name (in unhyphenated form).

The remaining Clerkenwell estate was bequeathed by Mary Lloyd Baker to her husband at her death. (fn. 7) But shortly before then, in the second decade of the nineteenth century, William initiated the development of Black Mary's and Robin Hood's Fields. He died with the work only half finished. Ownership of the Clerkenwell estate passed successively to his son, Thomas John Lloyd Baker (17771841), and grandson, Thomas Barwick Lloyd Baker (180786), the latter a pioneer of reform schools and theorist of crime and punishment. (fn. 8)

By 1844 at the latest the outlying portion of the estate next to St John Street, including Sadler's Wells, had been settled on the families of Col. Benjamin C. Browne and his brother the Rev. Thomas Murray Browne, Vicar of Standish, Gloucestershire, both of whom had married Lloyd Baker family members. (fn. 9) Subsequently the freeholds there were divided. Much of this land is now covered by the Spa Green Estate (see pages 96104). The name of Lloyd's Row, a street without houses, is all that is left to testify to the family's connections with that area.

Ownership of the main western body of the estate followed through the male line to T. B. Lloyd Baker's son, Granville Edwin Lloyd Baker, later Lloyd-Baker (18411924). (fn. a) Granville's own son having been killed in action in 1916, when he himself died in 1924 the property descended to his grand-daughter Olive Katherine LloydBaker (190275). (fn. 11) A life-long spinster, Olive Lloyd-Baker ran the estate in an almost maternalistic manner, keeping the rents moderate, paying regular visits, and making it her business to get to know her tenants. According to her friend and obituarist Stella Newton, she 'took an equal interest in their budgerigars, incunabulae [sic] and aunts in Australia, though she often found it difficult, after consuming spaghetti at four in the afternoon with a tenant of Italian origin, to do justice to tea and muffins in each of three adjacent houses'. (fn. 12)

Three years after her deathfollowing a fall on the steps of Gloucester Cathedralhalf the estate was put up for sale. In 1979 Islington Borough Council acquired 95 houses, including most of Granville Square and Wharton Street, and much of the north side of Lloyd Baker Street. Ironically, the long-term consequence of Islington's acquisition coupled with the individual sale of further Lloyd Baker houses has been to perpetuate old divisions in the area's character, with tenanted dwellings predominating on the lower slopes and freeholders in a majority at the top of the hill. At the time of writing the trustees of the Lloyd Baker estate retain some forty properties, mostly in the form of flats, in and around Lloyd Square, Lloyd Street and Cumberland Gardens, plus a small number of complete houses. (fn. 13)

The estate before development, 17441816

At the time of the 1744 partition Black Mary's Field and Robin Hood's Field were let to the New River Company. The only buildings were the Bull in the Pound public house, forerunner of the present-day Union Tavern (though not quite on the same site, see page 306), and a modest L-shaped building, probably a farmstead, situated in the north-east corner of Black Mary's Field. The present-day site of the latter is near the top end of Wharton Street.

In 1769 John Lloyd's widow Mary leased slightly over four acres in the western part of Black Mary's Field to three builders, John Graham, Edward Cole and Thomas Churchill, for a tile works, with rights to erect kilns, sheds and houses for their agents and workmen, and to dig for clay over an area not exceeding three acres. The lease was for fifty-nine years expiring in 1828, when the lessees (called the 'Bricklayer's Company' in later documents) were to restore the disturbed ground 'so as to lay the same on a proper hanging level' towards the adjacent Bagnigge Wells Road. (fn. 14) One kiln had been built by the time the lease was signed, and can be seen in a view published in 1775. A second kiln was added before the end of the century (see Ill. 386 on page 299). Both stood close to the road.

From at least the first decade of the nineteenth century, when J. P. Malcolm described the earth as 'of a bright flame colour its unequal surfaces, turfed with grass', (fn. 15) the tile works was in the hands of George Randell, latterly in partnership with John Randell. The business was a flourishing one, producing not only tiles but also chimneypots, bricks 'and other materials for building', and was 'so well situated' to supply the trade that in 1809 T. J. Lloyd Baker believed that 'the clay would be worked out in no time'. (fn. 16) In 1828 Thomas Cromwell reported that 'a stranger to the spot must feel surprise at the extent to which the clay has been removed for this manufacture'. (fn. 17) That year, George Randell put the kilns and other buildings up for auction and began reinstating the site. The poor quality of the made-up ground was to have severe consequences for the subsequent development of Granville Square. After moving the tile-making business to New Road, St Pancras and to Maiden Lane, north of King's Cross, (fn. 18) the Randells undertook some development along Bagnigge Wells Road.

One more short-lived activity found a home on Black Mary's Field in the early years of the nineteenth century. This was an 'archery target ground', called the 'London Light Horse Target Ground' or, on one plan, the 'Military Ground'. The barracks of the London and Westminster Light Horse Volunteers were relatively close by, in Gray's Inn Road. (fn. 19) An estate plan of 1807 shows the target ground as comprising a squarish building fronting Bagnigge Wells Road, behind which is a long enclosed area approximately on the line of the future Wharton Street. In 1818 Randell was said to be filling in and levelling 'next to the Light Horse Target Ground', so it may have survived until the ground was needed for house-building. (fn. 20)

Planning and layout

The development of the Lloyd Baker lands must be seen in the context of building, active or potential, all around the family holding, especially on the freeholds of Lord Northampton and the New River Company (see Chapters VIIX). Where these larger landlords ventured the Lloyd Bakers might follow, though in the case of the Northampton estate there was as much to avoid as to copy.

Naturally the first part considered for development was the southern outlier around Islington Spa. There in 1806 William Lloyd Baker with the help of his son Thomas John tentatively put the ground into the hands of the speculating builder-surveyor Henry Leroux, who also produced an estate plan of the whole Lloyd Baker holdings in Clerkenwell the following year. At that time Leroux was also actively promoting ambitious plans for Lord Northampton's lands much further north, in Canonbury. The Lloyd Bakers appear to have had limited confidence in Leroux, whose collapse into bankruptcy in 1809 curtailed practical progress. In his place the lessee of Islington Spa, Samuel Bingham, proceeded to undertake development there piecemeal, without an overall plan. (fn. 21)

When it came to building on their larger holding, fresh forethought had therefore to be taken. The first inkling of development comes in April 1817, when William Lloyd Baker consults his lawyers, Bray and Warren of Great Russell Street, about the advisability of having his own surveyor to deal with the professionals on the adjoining estates. At this early stage he is keen for his own land, a wedge between the two larger adjacent estates, to be properly integrated in terms of communications and roads. The solicitors reply that Lloyd Baker needs to be 'well advised as to the consequences to his estate from the projected buildings on each side and how far a mutual correspondence may be to the benefit of all', and urge the appointment of an 'able surveyor'. (fn. 22)

Lloyd Baker's own suggestion was a Mr Bainbridge, a surveyor who shared an address in Guilford Street with the better-known Thomas Chawner and had been satisfactorily employed in connection with Randell's lease. But in the end the man chosen, on the solicitors' recommendation, was John Booth, a surveyor in Devonshire (now Boswell) Street, Queen Square, whom Lloyd Baker had employed the year before to make a valuation of Sadler's Wells Theatre. (fn. 23)

Then in his late fifties, John Booth (17591843) was no doubt a man of some professional experience. Yet little is known of his previous activities. A bricklayer's son, he had in 1802 been president of the Surveyors' Club, a society that leant towards the practicalities of architecture. (fn. 24) He had long family connections with the Drapers' Company, of which he was Master in 1821. (fn. 25) He had also been a member of the Holborn and Finsbury Commission of Sewers since 1811, in Lloyd Baker's eyes a definite point in his favour. (fn. 26) All in all, it is likely that Booth was recommended and hired for his skill as a land-surveyor.

By 1817 Booth was already being assisted by his son, William Joseph Booth (c. 17961871). (fn. 27) Booth junior's education included a pronouncedly architectural element, extending to a tour in 1820 to Italy and Greece, where he 'imbibed a decided taste for Greek architecture'. (fn. 28) He played an increasingly explicit role in the later stages of the Lloyd Baker development, eventually succeeding his father as surveyor. W. J. Booth was also surveyor to the Drapers' Company from 1822 to 1854. From 1830 onwards he made various additions to the company's estate towns of Moneymore and Draperstown, Co. Londonderry, in which the solid classical taste manifest on the Lloyd Baker estate can also be seen. (fn. 29) At his death he was said to have had 'a very refined appreciation of art in all its branches' and to have owned a valuable collection of books, prints and architectural casts. (fn. 30)

The respective architectural contributions of the Booths can hardly be disentangled. Booth senior was responsible for the layout and, in the early years at least, formally for the architecture. By the end of the 1820s 'young Booth' was coming up with suggestions and new designs openly acknowledged as his (see page 271). As will be seen, it is likely that the earliest architectural designs for the estate also emanated from him.

Relations between John Booth and his employer were not always easy. Thorough and conscientious, Booth was slow and at times dilatory. Far away in his Gloucestershire rectory William Lloyd Baker, himself well past middle age, fretted and fussed over the rate of progress while demanding to be consulted over everything. That required Booth to write frequent reports, describing minutely what was going on. These letters would sometimes come back from the country covered with comments in Lloyd Baker's illegible hand. And as if not satisfied with Booth's reports, he also relied on his son in London, T. J. Lloyd Baker, to act as a sort of agent on the spot.

Strained by the delay in settling the layout plan, relations between Booth and Lloyd Baker reached a low point

in 18212 when Lloyd Baker consulted Bray and Warren

about dispensing with Booth's services. Having recommended Booth in the first place, the lawyers' first reactions

were defensive:

we recommended Mr Booth to you knowing that though he

was slow he would do what he could for the benefit of the

party employing him and that you might entirely depend on

him for what he did further than this we have no interest

whatever in Mr Booth being employed. (fn. 31)

In due course they offered to try and find a new surveyor who 'will give your business greater attention and we shall be only sorry that Mr Booth has by his own neglect made it necessary'. (fn. 32) In the end nothing happened and Booth kept his position, though perhaps with increased help from his son.

In accordance with instructions, Booth's first move in determining the layout was to sort out relations with the neighbouring proprietors, then further forward in the course of developing their holdings. At the end of October 1817 he told Lloyd Baker that he had taken a plan of his property but would come to no arrangement until he could see Lord Northampton's surveyor. (fn. 33) Getting a sense of S. P. Cockerell's plans for the Northampton ground to the south and conferring with the other surveyors of surrounding estates, W. C. Mylne for the New River Company to the north and east, and James Spiller for Lord Calthorpe to the west, took many months. Meanwhile Booth had got so far as deciding that 'it may be desirable to build a square' and explaining some 'general outlines and a stile of building' to T. J. Lloyd Baker. (fn. 34)

By August 1818 Booth had made a preliminary plan, which Lloyd Baker then annotated. (fn. 35) But the first fully matured plan may be dated to the end of September when, following an interview with Mylne, Booth on the same day sent to his client 'a Sketch of the lines of Road and Plans of Buildings'. His main preoccupation at this juncture was still 'lines of communication'including disconnections from neighbours as well as connections with them. 'The Estates will not be improved by any communication on the South side abutting on Lord Northampton's Estate', Booth insisted in September, 'the Houses being of an inferior class consequently would be an inlet to all descriptions of Persons and may be a great annoyance to us'. (fn. 36) The effect of this advice was to close off direct connection between the estate and the areas to the south for more than a hundred years.

An intriguing feature mentioned in Booth's letter quoted above was a 'line of Crescent for the accommodation of the [New River] Company's two Principal Mains which run across the Upper Field from East to West into the reservoir'. The site referred to, faintly indicated on an undated New River Company plan, is almost certainly that which later became Lloyd Square, suggesting that the concept of a square there was not yet fixed. (fn. 37) Though briefly debated, in the event the crescent came to nothing. While appreciating that it was intended to contain Booth's 'best houses', and despite his son's plea that 'A Crescent will be handsomer than a straight line', William Lloyd Baker insisted that it be straightened out. (fn. 38) Instead the line of the New River mains was hidden diagonally beneath the square. (fn. 39) Apart from the architectural potential of the crescent, the episode indicates how planning could be influenced by pre-existing water mains.

The earliest plan to survive is the one sent to the

Commissioners of Sewers, (fn. 40) doubtless the same as the

'general plan for building on your estate' which Booth sent

to Lloyd Baker in September 1819 along with 'elevations

of the several classes of houses'. (fn. 41) The layout is not greatly

different from what exists today (Ills 346, 348): Lloyd

Square is now fixed, but a square on the site of the future

Granville Square is smaller and there is a kink at the top

end of Wharton Street, later straightened out. It had taken

two years to get this far. Lloyd Baker's impatience showed

through in the draft of a letter intended for Booth in

November 1819, but perhaps not sent:

When I look back on the length of time since we settled to

build I cannot but feel it hard that no one building is begun

or even agreed for. When you were mentioned to me as one

of the Commissioners for Sewers I hailed it as a means of

getting my business done the quicker but even that I must

complain of as protracted beyond the time in which it ought

to have been settled. (fn. 42)

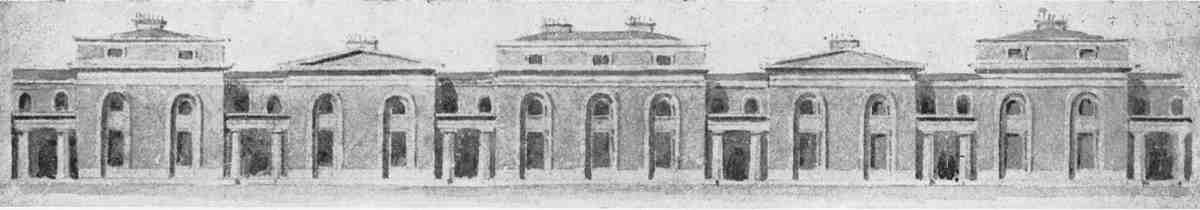

349. Preliminary drawing for elevation of houses in the Lloyd Baker estate, probably by W. J. Booth, 1819. From a lost original formerly in the Lloyd Baker Estate Office

The Pedimented Style

Leaving aside the houses along the boundary roads where special circumstances pertained, and the quite different style used later in Granville Square, most of the houses erected on the Lloyd Baker estate in the 1820s and 30s are pairs of two-storey villas in greyish brick with stucco dressings, charmingly united under shared pediments. These elevations, designed no doubt under the influence of William Lloyd Baker's injunction 'we must have things done handsomely', (fn. 43) are what mark out the estate's streets and squares as memorable.

Though almost no architectural drawings survive, a clue as to first intentions exists in the form of an image that must relate to the Booths' earliest designs (Ill. 349). It was published in Country Life in 1939, (fn. 44) where it is described as a design for houses, now destroyed, on the south side of Lloyd Baker Street. That seems most unlikely. The original, formerly in the Lloyd Baker estate office, cannot unfortunately now be found.

The drawing is said to have been dated 1819 and signed by one of the Booths, though there is uncertainty as to which; (fn. 45) at all events it predates W. J. Booth's tour of Italy and Greece. It shows a symmetrical arrangement of linked villas in pairsalternately two-storey with pediments and three-storey with shallow atticsflanking a broader, three-bay villa with attic in the centre. The style is individual, combining familiarity with Nash's picturesque villa idiom and a penchant for the Greek Revival, revealed by the baseless Doric columns in antis to the shared porches. Unlike the gable-'pediments' which crown some earlier London semi-detached pairs, for instance those in Kennington Park Road of the 1780s, those atop the lower houses are completely classical, and too shallow to contain accommodation. Just that form of pediment was to dominate the estate's early development, entailing a roof-form rare in speculative housing, and one which condemned the inevitable later roof-extensions to be fenestrated awkwardly to the sides.

Also notable on the drawing is the recession of the ground- and first-floor windows throughout within double-height archesa feature not quite original, but seldom so pronounced. Within these arches, the upperfloor windows are shown as implausibly small. The ground is represented throughout as a dead level, while the ends imply that the composition continues in both directions. Basements are not shown, yet the limited height restricts the size of houses evidently conceived as fashionable.

There are arguments for connecting this drawing to the crescent adumbrated in 1818. In favour is the similarity with Michael Searles's Paragon designs at Southwark and Blackheath, which likewise linked semi-detached villas into a crescent by means of colonnaded porches. Yet the shading of the drawing, seemingly in strict elevation, does not suggest a crescent. If the date of 1819 for this handsome composition is reliably reported, it is too late for the crescent but still preliminary. As to the authorship, its architectural idealism and practical naivet alike point to the younger Booth. Most likely it represented an ideal design for the estate which the older Booth expected would be pragmatically adapted to different sites and contexts, as indeed occurred.

While none of the surviving houses exactly matches this design, the closest echoes are to be found in the villas on the north side of Lloyd Baker Street (Ills 3513). Here uniquely the ground- and first-floor windows are set within arches, which look like simplified versions of the ideal design. Clearly however it was never Booth's or Lloyd Baker's intention to carry the ideal design across the whole estate.

Had things gone as first planned, there would have been fewer but wider pairs, each house having three bays. A few houses of that type were built along the east side of Lloyd Street and on the east side of Lloyd Square. But in Lloyd Street at least, the developer was allowed to make some modifications to the design. Generally, builders and developers thought three-bay houses were too big and expensive for the location. As a group of them put it in 1826, 'they might do for the West end of the Town but will never let at that situation'. (fn. 46) Eventually Lloyd gave in to the builders' demands for smaller houses, and the Booths produced the reduced two-bay version found in Lloyd Square and elsewhere.

In Wharton Street the elevations are even more pared down and the residual Palladianism is all but eliminated (Ills 3679). The signature pediments are retained but the houses are narrower, the windows wider, and there are no band courses. This new design is known to have been made in 1829 by W. J. Booth: T. J. Lloyd Baker commented at the time to his father, 'Old Booth is getting past work, and his son is getting into it and seems likely to do it well He has struck out the plan for the different kind of Houses (smaller ones if you will) which are now proposed to be built in Wharton Street'. The houses like those in Lloyd Baker Street could be objected to because they did not make the most of the ground 'in consequence of the recesses passages etc', and 'their decorations cost money'. Now, 'by young Booth's Plan these evils will be avoidedmore houses will be built, and this will be at a smaller expensethe same class of People precisely will inhabit them'. There was no danger, added Thomas Lloyd Baker, 'of their being taken by that sort of people whom we wish to keep out'. (fn. 47)

In the main streets where the pedimented style was established, it continued to hold sway throughout the 1830s (Ill. 351). In Lloyd Baker Street northwards of Granville Street, for instance, John Booth decreed in April 1831 that 'the proposed houses [there] will be similar to those already built in the street'. (fn. 48) But generally the main streets consisted of variations upon the theme set out, producing architectural homogeneity without uniformity.

One of the curiosities of the estate is the way in which a formal architectural language devised for even sites and regular proportions is expediently stretched and squeezed to cope with different dimensional predicaments. The most obvious is that of levels. All the eastwest housepairs have to adapt their architecture to the changing contours of the hill, while maintaining a semblance of classical order. Where the pairs abut, adjacent end-entry porches often jar ludicrously in numbers of steps, levels of doors and fanlights, and other details (Ill. 350).

The pedimented faades also have their effects on the backs of the houses, which are or were mostly flat and mirror the fronts with shallow gables. The three-bay houses of Lloyd Square and Lloyd Street apart, the internal planning is tight, allowing for only two moderate main rooms on each floor, quite square but generally connected on the ground storey by folding doors (Ill. 351). The better houses still have pleasant marble fireplaces. The extra accommodation tucked in over the side porches is limited by the requirement that it must be set back, so that each pair can be separately articulated. On the other hand most of the houses have deep basements to make up for their squatness.

350. Junction of houses at Nos 21 and 22 Lloyd Square, 2006, showing change of levels

Many features reveal that the Booths could not afford to be over-exacting as to detail. The proportions of the main windows vary from square to slightly elongated, with margin lights added to enliven the fenestration. Neither the external ironwork nor the front doors suggest any attempt to enforce uniformity or challenge the supplier's catalogue. If the most elegant doors are those with long, Greek-style flat panels on the north side of Lloyd Square, the most puzzling are the double front doors along the upper half of Wharton Street. As for ironwork, the railings enclosing the Lloyd Square garden are strong and stout. Most other gates, balconies and railings, whether residually classical with anthemion motifs (Ill. 351) or spiderishly Gothic, have a whiff of the job-lot. Once the main lines of the designs had been approved, details seem to have been left to entrepreneurs and builders.

Later phases and styles

The Lloyd Baker estate was built up over a period of more than twenty years, commencing with the rebuilding of the old Union Tavern at the north corner of what are now Lloyd Baker Street and King's Cross Road in 181920, and proceeding until the early 1840s. That rate of progress is consonant with the pace of adjoining estates and known fluctuations in the building cycle. After a good start, progress slowed from 1826 and did not pick up speed for a decade.

351. Lloyd Baker Estate. Typical elevations and plans of houses in Cumberland Gardens (top), Lloyd Baker Street (above), and Lloyd Square (right), with detail of typical front gate in Lloyd Square

Not all of the earlier portions of the estate followed the style of villa set out by the Booths. Along its edges, for instance, the architecture is more conventional. In Amwell Street (Thompson's Terrace) and Great Percy Street (Soley Terrace), where the Lloyd Baker frontage is continuous with the New River Company's and the roads were built by the company, Booth decided that the houses there would 'correspond' with the New River terraces.

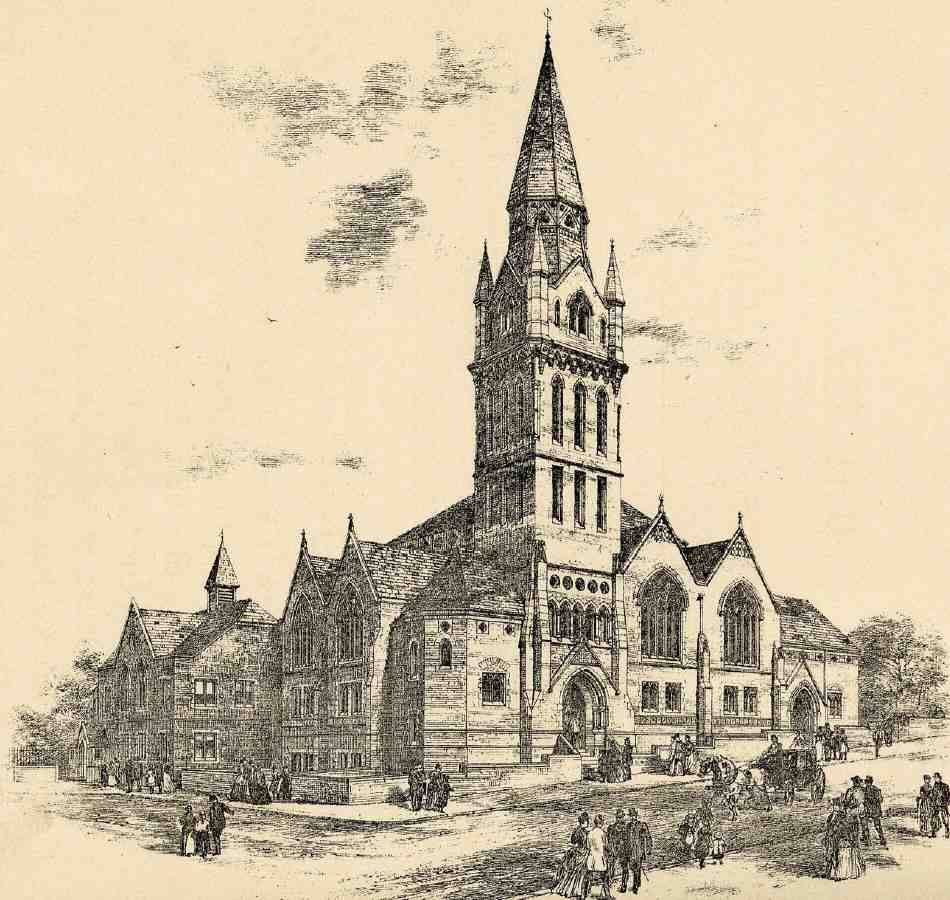

After William Lloyd Baker's death in 1830 the pedimented style carried on in developments still to be completed, but was abandoned for new ones. It may therefore have had something to do with the old clergyman's personal taste. The change is manifest in the comparative banality of Granville Square, the estate's second square. In John Booth's 1819 plan a square of quite modest dimensions was intended here. Its development was postponed, because it was under lease to the brick-and-tile maker, George Randell. When Randell's lease finally expired, the quality of his made-up ground left much to be desired, and the Booths advised holding off building until it had settled. As a result the first building in Granville Square by seven or eight years was E. B. Lamb's St Philip's Church in its centre (18312). Though the Lloyd Bakers gave the site for this Commissioners' Church, they took little interest in it, and its debased Gothic gave no architectural lead. The environs of St Philip's never quite shrugged off the depressive reputation they had then gained. 'For several years after its erection', noted T. F. Bumpus in 1883, 'the church stood in the midst of waste ground where rubbish might be shot, hence deriving the nickname "S. Philip's in the Dustheaps"'. (fn. 49)

House-building started in Granville Square only in 1839 and continued until about 1843, but its dull early Victorian elevations are difficult to credit as the creation of W. J. Booth. The reasons for the change in tone are not apparent, but may have proceeded from a slackening of T. J. Lloyd Baker's interest in the estate during the years before his death in 1841.

Rebuilding and redevelopment since 1843

By 1843, when W. J. Booth made a new survey of the estate, development was largely complete (Ill. 348). All building plots had been spoken for, and with the earliest leases not due to expire until 1911, a period of consolidation rather than change was in prospect. But the arrival in the 1860s of the Metropolitan Railway (see Chapter XII) caused a major upheaval where its designated route from King's Cross to Farringdon traversed the western fringe of the estate. T. B. Lloyd Baker had to give up a significant strip of property there, including the whole of the King's Cross Road frontage, the west side of Granville Square and the western ends of Lloyd Baker and Wharton Streets. (fn. 50) As was not unusual, the railway company's take was a generous one, not every square inch of which was needed, nor were all the standing buildings there demolished. Along King's Cross Road the two longest terraces were spared, but the northernmost terrace was removed, as were the entire west side of Granville Square, the houses in Lightfoot Street (now Gwynne Place) and at the bottom ends of Lloyd Baker and Wharton Streets, and all the buildings behind the Union Tavern.

352. Lloyd Baker Street, north side looking east from corner with Granville Street in 2006, showing Nos 3042 (right to left)

353. Nos 34 and 35 Lloyd Baker Street (right to left) in 2006

In visual terms the railway now hardly registers, since the tracks are mostly roofed over. One small section is open to the sky, and no doubt the sound and soot of the trains carried to adjacent houses.

Once the railway was completed the sites of demolished houses not required for the tracks deteriorated into what the Builder castigated as 'waste lands', the haunt of undesirables and 'a playground for the juvenile street-arab and king-mob population a kind of no-man's land', where the police declined to intervene because the ground was private property, and the railway companies because 'it was the business of the police to maintain order for the public'. (fn. 51) The removal of the west side of Granville Square and adjoining houses probably helped accelerate this district's descent in social standing. The waste ground was finally redeveloped in 18735 under building leases from the Metropolitan Railway. In Granville Square the new houses, while not facsimiles, did at least respect the proportions of the older properties; otherwise they are run-of-mill, even somewhat downmarket, no attempt being made to match the style of the originals.

Elsewhere on the estate the pace of change was slower and the changes themselves were gentler. Gardens were built over, shopfronts inserted, extensions built and extra storeys added. While the blight wrought by the railways was outside the Lloyd Baker family's control and confined to the edge of the estate, the first big disruption to its architectural unity was self-inflicted. This came in the 1880s when T. B. Lloyd Baker allowed the Sisters of Bethany to rebuild the houses on the east side of Lloyd Square as a House of Retreat, and subsequently to expand northwards into Lloyd Street. Built in phases between 1881 and 1884, the convent rises above its less ardent surroundings like a contemporary board school, which indeed it somewhat resembles.

Equally intrusive was the Spa Fields Church (18856), a portentous pile with a saddle-back tower looming over Wharton Street and Lloyd Square. The Lloyd Bakers were powerless to prevent it as they did not own the site. But when the church closed in 1936, Olive Lloyd-Baker bought the freehold to prevent the local authority from building 'cheap flats' there. The building which rose on the siteArchery Fields Housewas intended to harmonize 'both in architectural appearance and in the type of occupier' with the original villas. Making the case for such a style of architecture, the Lloyd Baker agent, R. W. Cable, laid out a strategy for the estate, should it survive 'the present wave of wholesale demolition'. He believed that the future lay in enhancing its 'special and interesting character'. The buildings were 'old and oldfashioned', but they were 'of a type increasingly rare in London and much sought after by a certain type of tenant'. (fn. 52)

The destruction to which Cable referred was on the south side of Lloyd Baker Street, and extending into Lloyd Square. Here the old houses had been acquired in 1921 by the Post Office, together with adjoining parts of the Northampton estate, for offices for the PostmasterGeneral's staff. That did not happen. But in 1930 the Post Office sold the land to Finsbury Council for public housing. Unhappy about the impact on Lloyd Square, the Lloyd Bakers tried unsuccessfully to buy back the strip of land between No. 2 Lloyd Square and No. 22 Lloyd Baker Street with a view to building something there 'specially designed to preserve the architectural unity of Lloyd Square' in face of the council's prospective flats. (fn. 53)

The blocks of the Margery Street Estate facing Lloyd Baker Street represented much the biggest incursion into the fabric of the estate. Another demolition was that of St Philip's, Granville Square, whose site became a playground after it was pulled down in 1938. The 1930s thus qualified as the greatest period of change on the estate since it was laid out for building.

But the changes of that decade pale by comparison with the redevelopment planned for the post-war period. In the closing months of the war a scheme for replacing all the original buildings was presented by C. D. Carus-Wilson, a semi-retired architect and neighbour of Olive LloydBaker in Gloucestershire. His plan shows only a few minor changes to the existing road layout (the two side streets into Granville Square are closed, and a new Olive Street occupies the east side of the square), but all the original houses are swept away in favour of accommodation for 1,704 people in 26 houses (all in Wharton Street), 464 flats and 13 shops. The areas bounded by the new buildings are laid out as communal gardens, with a site at the west corner of Olive Street and Wharton Street earmarked for a chapel. (fn. 54)

The plan was approved by the London County Council in 1945, but nothing could be done immediately to implement it beyond war-damage replacement. This exception allowed one small part of the Carus-Wilson vision to go ahead: Cable House, a block of flats at the corner of Lloyd Street and Great Percy Street, built in 19489 to replace seven houses destroyed or damaged during the war.

While building restrictions saved many of the old houses from demolition after the war, in the longer term Olive Lloyd-Baker's attitude may have been equally important in preserving them. When she laid the foundation stone for Cable House in January 1948 she was reported in the press as favouring a policy of preserving 'the Georgian buildings'. (fn. 55) When in October 1955 the LCC's consent expired, the Carus-Wilson plan was largely abandoned. (fn. 56) The reasons given were various, among them the listing of parts of the estate. A plan for a primary school between Lloyd Street and Cumberland Gardens had been scrapped, and the threat of compulsory purchase had receded. The estate's advisers now suggested that new plans should be prepared for the areas not covered by the 'preservation orders', in particular Great Percy Street, Amwell Street and Granville Square. (fn. 57)

Individual Streets and Buildings. Lloyd Baker Street

This street consists of two sections. Effectively it is a thoroughfare between King's Cross Road and Amwell Street, subsumed into Lloyd Square for part of its route. Until 19367, when the present name was adopted for the whole, the longer stretch west of Lloyd Square was called Baker Street and the short eastern arm east of the square Upper Baker Street. The two were separately numbered and are dealt with here sequentially.

Baker Street

This was the first and longest of the new streets. An early suggested name was Lloyd Street but Baker Street soon replaced it. The first buildings on the estate under Booth's development plan were erected here, at the bottom end, in 181920, but it took twenty years to complete. The pace was initially quite fast, but after the mid-1820s development slowed considerably.

The integrity of what William Lloyd Baker in 1818 thought would be the 'handsomest street' on his estate (fn. 58) was twice compromised: firstly by removal of houses at the bottom of the street for the Metropolitan Railway in the 1860s, and more seriously in the 1930s, when the entire south side was demolished and redeveloped with council flats (see Margery Street Estate), so opening up the estate to communication from the south for the first time.

A minor problem was caused by the presence of the Union Tavern at the junction of the proposed street with Bagnigge Wells Road, which Booth at first planned to get round by putting a kink in the roadway. (fn. 59) This plan was criticised by Lloyd Baker, but fortunately the landlord, John Carr, wanted to rebuild, and so the new tavern was set back from the old site, giving enough space to carry the road along straight and leave room on the opposite side of the road. Though there was little depth of plot there, Booth assured Lloyd Baker that 'it will form an entrance to both sides of the road and the elevations have a good appearance and [will] no doubt be the means of forwarding the general take of the ground'. (fn. 60)

The rebuilding of the Union in 181920 (see page 306) marked the start of the estate's development. Booth's design, though handsome, was unlike any other building subsequently erected there (see Ill. 395, page 306). There was no pediment and there were two double-height bows on the Baker Street front. This was perhaps Booth's way of showing this was a commercial rather than a residential building. A planned portico was not built. (fn. 61)

Lloyd Baker Street alone contained specimens of the houses with windows set within arches, as on the ideal design (Ills 3513). The earliest houses of this type still standing are Nos 4346. Though not the very first to be built, they were erected in the early 1820s during the first phase of development here, and doubtless matched those of 'good appearance' (now demolished) already under construction opposite.

On the south side the first houses to go up were built by David Elson of Old Bailey, builder, who erected Nos 115 between 1820 and 1825, starting at the corner with Bagnigge Wells Road. Eastwards of these, Nos 1622 were erected in 18267: the first two were leased to Daniel Perry and Thomas Ruscoe. At Nos 1822 the lessees were John Hurle, a surveyor, and his nominee, William Jury, a builder, respectively the first occupants of Nos 20 and 18. Jury's house extended over a gateway into his yard at the back. In the 1850s No. 19 was the home of the actor Henry Marston (Richard Henry Marsh). (fn. 62) The remainder of the houses on this side (Nos 2329) were built in 18257 by a local carpenter, Simon Kemp. (fn. 63) All the houses on this side backed on to a narrow street known as Spring Street, at the west end, and higher up as St Helena Place, named no doubt after the island where Napoleon was confined and died. Here there was sufficient depth of plot for small cottages to be built behind. Kemp's lease for his houses in Baker Street also included another ten at the back in St Helena Place. (fn. 64)

On the north side most of the original houses at the bottom end between the Union Tavern and Granville Street were erected under an agreement with Richard Morgan, a timber merchant, who in 1823 contracted to build six houses there (Nos 4348), and complete them within five years, a schedule he was able to adhere to as all but one were occupied by 1828. No. 48, Morgan's own home, was in part built over a gateway leading into his yard. The lessee of Nos 4346 and the occupant of No. 46 was Morgan's nominee Joseph Wright, a stage-coach builder. (fn. 65) The Rev. Warwick Reed Wroth, vicar of St Philip's, Granville Square from 1854 to 1867, occupied No. 43. (fn. 66)

At about the same time as Morgan was building his houses, John Carr erected three smaller houses to the west, between Morgan's plot and the Union Tavern, the one adjoining the tavern being built partly over a gateway into the tavern yard (see Ill. 395, page 306). This building was stylistically more akin to the Union than to Morgan's creations higher up the hill. (fn. 67)

Of all these houses only Nos 4346 are still standing, the rest having been demolished for the Metropolitan Railway. The present Nos 4750 were erected here in 1874 by Arthur Mazzini Wheeler and William Warren of Notting Hill, who also redeveloped similar sites in Wharton Street and King's Cross Road. The Lloyd Baker Street houses are not quite as plain as their dreary counterparts in Wharton Street. Wheeler and Warren also built an extensive range of commercial stabling for the cab trade at the back. As well as stabling, there were forage stores, with workshops above, and a large painters' and repairing shop, with a platform for raising the cabs. This is now Hardwicke Mews, a little enclave of gated housing. (fn. 68) Next door to the Union, No. 51 was largely rebuilt in stages for Wagland Textiles between 1979 and 1993. (fn. 69)

Northwards of Granville Street, houses were not begun until the early 1830s. The first to be completed were Nos 3037, built c. 1831 under an agreement with the developer James Blackburn and occupied by 1832. All eight were leased to Blackburn's nominees: Edward Garland of Amwell Street, builder (Nos 3031), John Harvey of Canonbury Square, gentleman (Nos 3233, and 3637), and Smith Geeves of Macclesfield Street, bricklayer (Nos 3435, Ill. 353). (fn. 70) The next group westwards, Nos 3840, was erected by the builder Benjamin Matthewson of Hoxton in 18312 and occupied from 1833. (fn. 71) Of the three remaining houses on this side, Nos 41 and 42 were due to the builder Thomas Herridge of Wharton Street about 1838, and occupied from 1839, (fn. 72) while No. 30 has evolved from a former stable at the back of No. 29 Lloyd Square (see page 279).

The gap between Nos 40 and 41 is the result of insufficient depth of plot for houses both here and behind in Granville Square, owing to the converging alignment of the street and the south side of the square. The same thing occurs in Wharton Street. In Lloyd Baker Street this led also to a break in the sequence of semi-detached houses in favour of single ones (Nos 40 and 41) with parapets instead of pediments. No. 42 is different again: it too is a single house, but here symmetry required a pediment (Ill. 352). The entrance is on the return front in Granville Street.

Various later alterations took place behind the frontages. A small mission hall facing Spring Street, now long gone, was built to the designs of Hugh Roumieu Gough behind No. 14 in 1885. (fn. 73)

Upper Baker Street

Originally, there were no building plots on the north side of Upper Baker Street. The entire frontage was taken up with the return fronts and back gardens of two corner houses, one facing Amwell Street, now numbered 25 Lloyd Baker Street, and the other (now demolished) facing Lloyd Square and originally numbered 12 in the square. The present No. 26 is a conflation and refashioning of two smaller properties built in the garden of No. 25 in the midnineteenth century. West of this is the return front of the former House of Retreat in Lloyd Square, built in 18812 (see pages 2803).

On the south side the ground was taken by William Wade, the carpenter-builder who also had contracted to develop Lloyd Baker's frontage along Amwell Street (see page 200). He argued, successfully, that the four houses which he had agreed to build here 'would not take', the plot being too shallow, and he was allowed to substitute a short terrace of six 'fourth-rate' houses. Anticipating resistance to the change from William Lloyd Baker, Booth assured him that the elevations would be 'carried up according to my direction'. (fn. 74) In practice this meant dispensing with pediments and porticoes. The westernmost house in this group was given a wedge-shaped plan so as not to interfere with the path of the New River Company's water-main, crossing Lloyd Square from the reservoir at the top of Wharton Street. Building began early in 1822 and was probably still in progress at the time of Wade's bankruptcy in January 1823. Two houses were occupied in that year; the remainder in 1824. All six survive, the eastern five as Nos 1923 Lloyd Baker Street (Ill. 354), and the wedge-shaped house, now enlarged, as No. 12 Lloyd Square. East of No. 23 was formerly the garden of the house, also built by Wade, at the corner with Amwell Street, now numbered 24 Lloyd Baker Street (see page 200).

354. Nos 1923 Lloyd Baker Street (right to left) in 2007

Lloyd Square

Lloyd Square's trapezoidal shape was dictated in part by the tapering of Black Mary's Field from west to east, and the consequent convergence of Lloyd Baker and Wharton Streets as they rise up the hill from King's Cross Road. Lined on three sides by pairs of low pedimented villas, it is one of the most quietly agreeable of the many squares laid out in London during the early nineteenth century (Ills 3557).

Work began on the south side in the early 1820s, but only one pair of houses was completed before the slump in the building industry later that decade. As one of the contractors put it to William Lloyd Baker in 1829, 'such an unlook'd for change in building matters has taken place since we took the ground that has baffled the most cautious and prudent'. (fn. 75) Developers who had already agreed to take plots held back from doing anything with them, or tried to pull out of their commitments altogether. Building did not pick up again until the late 1820s, after builders were allowed to erect smaller houses.

Not all the houses now numbered in the square were originally part of it. The earliest are the present Nos 9 and 10 (numbered 1011 in the lease), which were to have been the easternmost pair on the south side. The builder who contracted to take this site in 1822 was William Wade, who may not have progressed far before his bankruptcy the next year. Later the builder was stated to have been John Folkman, of Folkman & Fowkes, iron-plate manufacturers latterly based in Baker's Row, Clerkenwell. Folkman died early in 1823 and his executors declined the lease, which was not executed until his children came of age in 1839, though both houses had been occupied since 1828. (fn. 76)

Alone of the paired and pedimented villas in the square, Nos 9 and 10 do not have porticoed entrances (Ill. 356). Afterwards, the builders of the houses to the west claimed they 'naturally suppos'd' Nos 9 and 10 set the pattern for building in the square. (fn. 77) It may be that though without porticoes themselves they were intended to be flanked by them. Indeed on the west side a portico is still there, though not built until after Wade's bankruptcy. Independent of No. 9, it was the front end of a passage leading to some cottages at the back of the square facing St Helena Place (now Street), built or at least begun by Wade but not leased until 1830. (fn. 78) After those cottages had been demolished, the passageway led for many years only to an office numbered 8 Lloyd Square; it was being absorbed into No. 8 at the time of writing.

Two different-looking houses lie to the east. The present No. 12 was built in the early 1820s by William Wade as the westernmost house in a modest, pedimentless terrace in what was then Upper Baker Street. Since the plot was crossed by the New River Company's watermain, Wade was obliged to give this building a wedgeshaped plan and to leave a strip of land undeveloped so as to allow access for the company, until the closure of the West Pond reservoir (see below). By 1871 an extra house, the present No. 11, had been built on this strip. With its strangely recessed ground storey flanked by pilasters, it looks like what it is, a piece of infill.

355. Lloyd Square, garden and north side (showing Nos 1421) in 2006

356. Nos 9 and 10 Lloyd Square in 2006, with entrance to No. 8 on extreme right

357. Lloyd Square, north side in 2006, with Nos 1423 (right to left)

The remainder of the south side was contracted for in 1825 by the development partnership of George Tindall, gentleman, and George Paul of Saffron Hill, builder. (fn. 79) By November 1829 the site was still vacant in consequence of the building slump, wrote Tindall and Paul: 'ever since we took it we have been indefatigable in endeavouring to let it and have offered to let it hundreds of times at the same price we agreed to give and to assist the parties a little without the smallest profit'. (fn. 80) They therefore declined to have anything more to do with the site unless they were allowed 'to get 4 pairs of cottages instead of 3 in the space; which will bring them to about the same as the two already built in the square [Nos 9 and 10]'.

This was not the first time that developers had complained of a mismatch between the size and cost of the houses Lloyd Baker wanted and the resources of likely tenants. Tindall and Paul submitted their own plans and elevations, which John Booth called 'inferior and illproportioned', the more objectionable 'by assuming a likeness without agreement in the parts'. (fn. 81) But though Booth resisted any change in the square, on the grounds that it would 'not be right to alter the original plan as 2 sides are already let', (fn. 82) a way to complete it had to be found. As he told T. J. Lloyd Baker, 'the present state of things is against us'. If houses in the square were built 'on a less expensive scale than hitherto designed', he conceded, others might make offers for the unlet parts of the estate. So after some prevarication he overhauled the design of the three-bay pairs, reducing them to two bays, and their double-plot frontages from sixty to forty-six feet, as Tindall and Paul had asked. (fn. 83)

Having seen Booth's revised plan in January 1830, Tindall and Paul 'felt assured' the alterations would not only 'prove beneficial to both the builders and the estate', but being 'more suited to the very small space allotted for the square', would 'no doubt cause the remainder of the ground to be let much sooner'. Yet they were still disinclined to proceed, 'things being in such a state we fear we shall not be able to let the ground'. (fn. 84) Some easing of the rent was conceded, in return for which Tindall and Paul agreed to build eight houses there (Nos 18), and to have four in carcase by September 1830 and the other four a year later. (fn. 85)

The houses were duly leased to them in 1831, and filled up with occupants in 18323. (fn. 86) Nos 1 and 2 were demolished in the early 1930s for public housing in Lloyd Baker Street. Leased with Nos 18 was a range of doublefronted cottages with yards (all now gone) fronting St Helena Place (see Ill. 336, page 257).

Development on the north and west sides of Lloyd Square, once started, was relatively straightforward (as Tindall and Paul had predicted), and more or less contemporary with the building of Nos 18. Nominally responsible for developing these two sides was an entrepreneur named James Blackburn, described as 'gentleman', at that time resident on the estate in Soley Terrace and to all appearances 'highly respectable'. (fn. 87) The son of a scalemaker and brother to the first minister at Claremont Chapel in the New (Pentonville) Road, Blackburn had had at least some training in engineering, architecture and surveying, and had worked for the local Commission of Sewers as an inspector. In Lloyd Square he appears to have been successful; but on moving on to Nos 910 Lloyd Street and Nos 4447 Wharton Street he overreached himself disastrously. Short of money in February 1833, he forged three signatures on a Bank of England draft for 600. He was rapidly caught, arraigned and sentenced that May to transportation, despite character witnesses from, among others, the Lloyd Baker solicitor Augustus Warren, John Booth and several of the sewer commissioners. Once in Tasmania, Blackburn's probity reasserted itself, and by the time of his death in 1854 he was respected as an architect and engineer who had done much to develop Hobart and Melbourne. (fn. 88)

All that was in the future. On the west side of Lloyd Square (Ill. 375), Blackburn devolved the work to two professional builders, William Chandley and Edward GarlandBooth reported in January 1831 that 'another party has begun foundations [for this side]'. (fn. 89) One of Garland's houses was burnt out while under construction. All six were leased, at Blackburn's direction, to Chandley (Nos 24 and 25) and Garland (Nos 2629) in the summer of 1831. (fn. 90) They were all occupied by 1832, those at the corners, Nos 24 and 29, by Chandley and Garland respectively. (fn. 91) Though the lease covenants prohibited 'a public show of business' in the square, in 1839 the occupant of No. 29, Philip Burrowes, obtained permission to convert the stables behind his home into 'a shop for the purpose of carrying on my profession as surgeon'. Later called an office, it is now a separate, small stuccoed house numbered 30 Lloyd Baker Street. (fn. 92)

Along the north side (Ills 355, 357), four houses at the east end (Nos 1417), described by the Lloyd Baker solicitors Bray and Warren as 'very well built', were ready for leasing by the end of 1830. The other six (Nos 1823) were leased in 1831, and all but one occupied by 1832. (fn. 93) Garland, who at Blackburn's nomination was the lessee of Nos 2123, was probably the contractor for the whole. Another of Blackburn's nominees here was the developer George Tindall, who took the lease of No. 20. His widow was still living there in 1851. (fn. 94) The end house, No. 14, was restored at considerable expense in the early 1990s by the portrait painter Henry Mee. (fn. 95)

The short east side was the only side to have the controversial 30 ft-wide houses, effectively continuing the east side of Lloyd Street, where such designs had already been built. There was only room for a single pair here, originally Nos 12 and 13. The builders were James Mansfield & Sons, the firm employed to make sewers on the estate and takers also, like Garland, of part of Myddelton Square. (fn. 96) Mansfield had applied for the site in 1825, but like others seems to have put off doing anything with it during the building slump. (fn. 97) The two houses are first recorded in 1832, when they are called 'new', but they remained empty until 18389, the last in the square to be occupied (fn. 98) The first inhabitants were a merchant and stockbroker and their respective households. (fn. 99) They were demolished in the early 1880s for the House of Retreat.

Past residents of Lloyd Square have included two wellknown illustrators: Linley Sambourne, who was born in 1844 at No. 15, the son of a wholesale furrier, and Sidney Paget, illustrator of the Sherlock Holmes stories, who lived at No. 19 with his parents before he married in 1893. The Victorian architect Enoch Bassett Keeling lived briefly at No. 3 at the end of the 1860s. Among many medical men to live here in the 1840s and 50s, at No. 25, was the Glasgow-trained physician Thomas Harrison Yeoman, editor of The People's Medical Journal. The theatre critic Thomas Purnell ('Q') died at a house here in 1889. (fn. 100)

The square garden

The central garden (Ills 355, 375) was originally a much smaller enclosure. The present-day perimeter fence is nearly 700 ft long, but when James Mansfield & Sons secured the contract to enclose the garden in 1829, their price was based on a total length of only 467 ft. This may correspond to the oval shape shown on Booth's plan of 1819. Mansfields supplied cast-iron railings, with wrought-iron top-rail and dog-rail, two gates, and a castiron curb on brick foundations. The enclosed area was being laid out by the end of 1830, with planting specified as to be agreeable to the tenants and done at their expense. (fn. 101)

Finding this garden 'much too small', James Blackburn set about enlarging it, though without having any authority 'except casual conversation with other persons'. After starting the process in 1832, Blackburn decamped 'in circumstances which preclude his ever finishing it'in other words bankrupt and transported (see above). George Tindall and Edward Garland warned Lloyd Baker that their tenants in the square were threatening to quit unless something was done about the garden's chaotic state. The removal of the railings had left it 'exposed to vagrants who are daily pulling it to pieces', and the shrubs and trees, already 'sadly injured', were in danger of being 'entirely destroyed'. Though they hoped for a contribution from Lloyd Baker, the lessees were responsible for finishing and making good the enlarged garden, the upkeep of which was paid for by a levy or rate on the inhabitants of the square. By April 1834, they had agreed to pay most of the estimated 150 required to put the enclosure back into good order, including painting and planting. (fn. 102) It seems likely that the present railings are the original ones, reused and extended after Blackburn's intervention. The earliest indication of the garden layout is from the Ordnance Survey of the 1870s, when it did not differ greatly from the present arrangement.

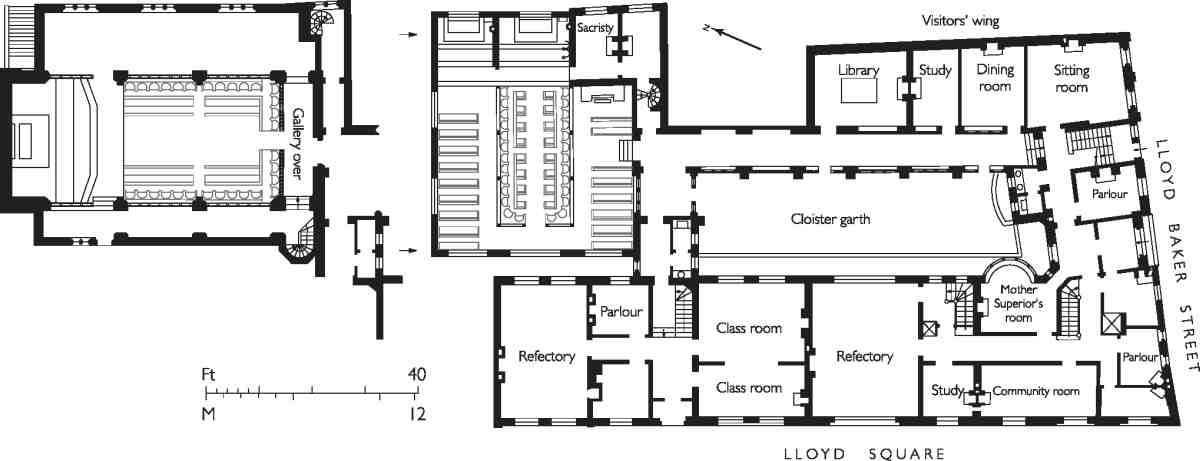

Bethany House (former House of Retreat and Chapel)

Commanding the summit of Lloyd Square and in contrast to the houses around it is the former conventual House of Retreat, a colourful specimen of 'Queen Anne' architecture, raised to the designs of the young Ernest Newton in 18814 (Ill. 358). A refined Gothic chapel was added by Newton behind the street frontage in 18912. The buildings are now in separate ownership, as a hostel and studio respectively, the latter now reached from Soley Mews.

358. Bethany House (former House of Retreat), Lloyd Square in 1998. Ernest Newton, architect, 18814

359. House of Retreat, plan as built, showing temporary chapel of 18834 and Newton's permanent chapel which replaced it in 18912

This complex originated with the Society of the Sisters of Bethany (SSB), an order established by the pious, strong-minded heiress Etheldreda Anna Benett. Mother Etheldreda, as she became, started her religious life in 1864 at the age of 39 as a novice with All Saints Sisters of the Poor, Mortimer Street, in the West End. In 1866 she inaugurated her own order with one companion in a rented house at No. 7 Lloyd Street. Other houses were gradually taken in, beginning with the three to the south (then numbered in Lloyd Square) down to Upper Baker Street, and after 1889 further ones to the north. Calling themselves at first the Sisters of the Order of Retreat, the nuns aimed to attract those 'who aspired to the "mixed life" of prayer and activity'. A feature of their work was retreats for women, a concept then new in the Church of England. Girls were also taken into the convent for training, probably as servants, while the nuns helped with the parish work of St Philip's. These developments doubtless had the support of T. B. Lloyd Baker, a High-Church Tory deeply involved in the reform and training of working-class boys and girls. In time a famous school of church embroidery also developed in the adjacent houses at Nos 46 Lloyd Street. (fn. 103)

360. House of Retreat, perspective of temporary chapel by Ernest Newton, c. 1884

A small chapel was built in the back garden of No. 7 in 18667 to the designs of G. E. Street, who had previously worked for the All Saints Sisters. It was enlarged by Dove Brothers to R. J. Withers' designs in 1868 and again in 1870, as the SSB grew. (fn. 104)

361, 362. House of Retreat, sketches by T. Raffles Davison, 1896. Cloister garth with chapel behind; and interior of chapel

In 18745 the SSB extended its work by building an orphanage at Boscombe on the South Coast, to which a wing for the sisters was soon added. There the architect was Street's erstwhile chief assistant Norman Shaw. Doubtless through Shaw's recommendation it was to his own former chief assistant Ernest Newton that Mother Etheldreda turned when in 1881 the project of rebuilding matured. Shaw and the Mother Superior remained lifelong friends, and his daughter Elizabeth Helen became a nun here in 1897. (fn. 105)

The new House of Retreat was constructed in two stages. First came the southern portion, replacing the old houses in Lloyd Square and including the return front to Lloyd Baker Street. Comprising mainly cells for forty sisters ('each with a fireplace'), it was built in 18812 by Perry & Co. The higher northern portion on the sites of Nos 7 and 8 Lloyd Street, containing school accommodation in front with a toplit chapel behind (Ill. 359), followed on at the hands of William Bangs in 18834. (fn. 106) Perhaps partly because of this division, Newton, still in his twenties and not yet the cool and measured architect he became, chose an episodic Queen Anne idiom. In rejecting Gothic for an order of Anglican nuns, Newton was following Shaw's lead at Boscombe. Apart from his master's influence, there is something of the early schools of the London School Board in the composition, something also of Basil Champneys' Queen Anne style in the swooping parapets, squarish chimneys and arched double stack over the entrance in the flank elevation along Lloyd Baker Street.

The main points of internal interest in the building were two. One was the narrow cloister garth, still extant (Ill. 361). It has a single-storey corridor around two sides, endowed with generous semi-circular windows and topped with a pretty wooden balustrade. The other was the chapel. This took the position of its predecessor behind No. 7 Lloyd Street, and probably incorporated traces of its fabric. A preliminary sketch shows a toplit, timber-framed space of secular feeling, with leaded lights in the dormer windows and central lantern. The width of the previous chapel has become the nuns' choir, now separated off by low screens and flat-centred arches from two aisles for visitors, of which perhaps only the southern one was built. The sketch shows a rood feature similar to the chancel screen in Shaw's St Mark's, Coburg Road, Walworth (187980), and a painted polyptych reredos of the type developed in Arts-and-Crafts circles. These features had vanished by the time Newton made a second perspective of the interior (Ill. 360). In the event, encaustic flooring, an altar with a carved marble front and a reredos divided into large painted panels showing Christ in Glory were brought in from the previous chapel. New stalls in American birch, made by James Knox of Kennington, were however fitted. (fn. 107)

363. House of Retreat, interior of chapel looking towards organ and gallery, date unknown. Furnishings by Ernest Newton

This chapel too was temporary. In 1889 Mother Etheldreda secured a lease of the next house northwards, No. 6 Lloyd Street. (fn. 108) It was for a site comprising that house's garden and the chapel of 18834 that Newton designed the SSB's permanent chapel (Ills 359, 3613). Perhaps contemplated as early as 1888, when Newton showed a drawing of a chapel at the Royal Academy, it was built only in 18912, by Maides & Harper of Croydon. (fn. 109) This time the style was the lofty Gothic of late Victorian High-Church taste. Similar in aesthetic to Newton's only major church, St Swithun's, Hither Green, but more concentrated, it is a building with a plain stock-brick exterior, in response to the confined site, but much internal grace. The orientation was to the north for practical reasons, with vestries beneath the sanctuary. There are three main bays and two aislesa passage aisle on the west side and a wider eastern aisle for visitorsmarked off by deep arcades with flat soffits. Moulded ribs rise sheer from the front of the piers, first to a cornice beneath the clerestory windows, and then to a deep wall-plate carrying the boarded roof. The aisle roofs are also boarded. Lighting is from tall traceried windows in the clerestory on three sides and square-headed windows in the aisles; a window over the altar was omitted at a late stage. The original finishes were stone and ivorytoned plaster. The boarded nave ceiling was whitewashed in readiness for a scheme of painted decoration by Gerald Horsley, never carried out.

The chapel was embellished over the years. The narrow west gallery for the organ, in beechwood, may have been added in 1894, (fn. 110) the organ itself arriving a little later. A pair of rich screens was inserted by Newton in the northwest corner to create a side chapel in 1899, and it was perhaps at this date also that the aisles were screened off with fine oak screens in an Arts-and-Crafts interpretation of Perpendicular woodwork. The stalls and altar had at first been transferred from the old chapel. In 1903 the sanctuary was recast by Ninian Comper, who was closely involved with the SSB's School of Embroidery. It was embellished with black and white marble paving and a marble dado; the altar was given a dossal and hangings and surmounted by a high curved rood beam modelled on St Lawrence's, Nuremberg, with figures against the blank wall. (fn. 111) It was perhaps at this stage that the central panel on the marble altar front was replaced with a relief of the Deposition, though the flanking saints in niches remained. Stained glass in the aisle windows is conventional in character and may be by Burlison & Grylls. Newton's final contribution was a stoup near the entrance, added in 1921. (fn. 112) Only a few elements of this decoration survive today: the main screens to the aisles and the organ gallery, the sanctuary paving, the rood beam and painted cross, and the stained glass.

Additions to the House of Retreat after 1900 included a small annexe in a late Gothic style at the north end of the Lloyd Baker Street front, perhaps of 1909, and further rooms above and behind this, inserted in the 1930s out of view from the street. (fn. 113) The latter work may have been by W. G. Newton, son of Ernest Newton, since he designed the SSB's chapel at Boscombe at that time.

In 1962 the society gave up the House of Retreat and transferred their headquarters to Boscombe, taking with them most of the movable furnishings from the chapel. (fn. 114) The Lloyd Square buildings were sold to the YWCA for use as residential accommodation and converted sympathetically enough by the Elsworth Sykes Partnership in 19623. (fn. 115) The chapel itself was at first used as a sports hall, but later sold off separately and sealed off from the cloister. Thereafter it became accessible only from Soley Mews. Probably in 19623 its structure was altered in various minor ways, chiefly affecting the floor level. Latterly it has been used as a studio. Since the closure of the Boscombe convent, the marble altar front from the London chapel has been transferred to the Roman Catholic Church of the Annunciation, Bournemouth. (fn. 116)

364. Lloyd Street looking north, c. 1933. On right, Nos 15 (left to right). Nos 1 and 2 demolished

365. No. 11 Lloyd Street in 2006

Lloyd Street

Development in Lloyd Street (Ill. 364) got off to a brisk start in March 1823 when a double plot was reserved for a single large house (No. 11). But that promising lead did not result in a swift take-up of the other plots, a lack of interest William Lloyd Baker found 'extraordinary as the superior eligibility of [the street] must allow an addition of rent'. (fn. 117)

In November 1824 a developer did come forward for the east side in the person of Robert Rawlings of Red Lion Street, gentleman, whose contract also covered the return frontage to Great Percy Street (Soley Terrace), most of the houses on the Lloyd Baker frontage in Amwell Street and the whole of Soley Mews. (fn. 118) Rawlings subcontracted part of his agreement to Benjamin Bellamy, a carpenter in Spa Fields, who before succumbing to bankruptcy in July 1826 put in some foundations, but these were most probably in Amwell Street and/or Great Percy Street, rather than Lloyd Street. (fn. 119) The houses along Lloyd Street were built in 18289 and occupied in 182930. All were leased, in 182930, to Rawlings's nominees, who included a builder, William Chandley of Manchester Street, Gray's Inn Road (Nos 34), and a painter, Thomas James Booth of Tavistock Row, Covent Garden (Nos 56). The lease of Nos 1 and 2 included a stable and coach- or chaise-house in Soley Mews. (fn. 120)

The houses on the east side of Lloyd Street (and its southern continuation as the east side of Lloyd Square) were the widest of any built on the estate by speculators, despite the fact that Rawlings had joined with those other developers who had complained to Lloyd Baker that such designs were too big and expensive for this part of London (see pages 2701). In the event, tenants were not hard to find. Each house was three bays wide, and each pair occupied a generous 60 ft frontage. The linking blocks containing the porches were intended originally to be just one storey high, the space above being, in Booth's words, 'designed for giving more airiness as well as effect'. (fn. 121) Perhaps in order to improve the ratio of accommodation to width, Rawlings asked to build over these porches and was allowed to do so, provided the additional storey was set well back. Something like this can still be seen at No. 3, but elsewhere these spaces have been filled in.

Of the original eight houses on the east side only four survive. Nos 7 and 8 were demolished for the House of Retreat; Cable House stands partly on the site of Nos 12.

On the west side only two houses, Nos 9 and 10, were planned over and above the large double plot reserved for No. 11, north of which the ground was needed for a roadway giving access to Cumberland Gardens. Nevertheless an extra house, No. 12, was squeezed in on the garden of No. 54 Great Percy Street (then No. 10 Soley Terrace) in 18302. Double-fronted and detached but only one room deep and described as 'a cottage', it was erected by the builder, lessee and occupant of the Soley Terrace house, George Paul. Having begun work without permission, Paul was served with an ejectment order in January 1831: he appealed, submitting in support a paper signed by the neighbours consenting to the building, but only after T. J. Lloyd Baker had made a personal inspection was he allowed to finish it. (fn. 122) Paul himself was the first occupant. (fn. 123) In 1841 this modest-sized dwelling was home to two families, each with one servant. (fn. 124)

At the south end, Nos 9 and 10 were built in the early 1830s by James Blackburn and Edward Garland, developers on the north side of Lloyd Square, and first inhabited in 18323, No. 9 briefly by Blackburn himself before his conviction and transportation for forgery (see page 279). (fn. 125) Like the buildings opposite they are each three bays wide, though the plots are narrower.

No. 11, the biggest house in the street and the first to be built, was erected in 18236 for a barrister, Holker Meggison, author of The Sponge: Being an Inquiry into the Validity of the Public Charge pleasantly denominated the 'National Debt', and A Treatise of the Administration of Assets in Equity. Outwardly (Ill. 365) it looks like a pair, even to the extent of having two porches, and the floor plan was contrived to fit behind a standard elevation designed for a pair of houses. In fact the north porch (now blocked up) served as an entrance to the stables and offices at the back. When finished, the back building was found to have slightly exceeded its permitted height'the fault of the builders and against Mr Meggison's instructions'; (fn. 126) both this building and the stable seem to have been short-lived.

Although intending No. 11 (originally No. 9) for his own occupation Meggison seems not to have lived there. The first resident was the Rev. John Blackburn of Claremont Chapel, brother of James Blackburn. His successor there in 1838 was another clergyman, the Rev. John Beacham or Beecham, a Wesleyan minister. In 1851 his household included two other Wesleyan ministers, one his son-in-law. (fn. 127) Men of the cloth seem to have found Lloyd Street congenial: in 1841, as well as Beacham, there was a clergyman at No. 9 and the Pastor of the French Church at No. 3. (fn. 128) The budding philosopher Herbert Spencer lived intermittently at No. 2 (now demolished) in 18457. (fn. 129)