Survey of London: Volume 46, South and East Clerkenwell. Originally published by London County Council, London, 2008.

This free content was digitised by double rekeying. All rights reserved.

'St John Street: East side', in Survey of London: Volume 46, South and East Clerkenwell, ed. Philip Temple( London, 2008), British History Online https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vol46/pp221-241 [accessed 23 November 2024].

'St John Street: East side', in Survey of London: Volume 46, South and East Clerkenwell. Edited by Philip Temple( London, 2008), British History Online, accessed November 23, 2024, https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vol46/pp221-241.

"St John Street: East side". Survey of London: Volume 46, South and East Clerkenwell. Ed. Philip Temple(London, 2008), , British History Online. Web. 23 November 2024. https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vol46/pp221-241.

In this section

East side

Charterhouse Street to Clerkenwell Road

London Printing & Publishing Co.'s works (demolished). This short-lived building is of interest both for its stylistic character, derived from French and Flemish sources, (fn. 1) and for its connection with the entrepreneur John Tallis, publisher of the London Street Views. It was erected in 1860 by the trustees of Jane Cart's Charity, the freeholders, for the London Printing & Publishing Co. Ltd, to the designs of George Somers Clarke; the builders were Kirk & Parry, and the stone-carver was Thomas Earp. It stood at the corner of Charterhouse Lane, opposite the site now occupied by Nos 2–6, and was numbered 97–100 St John Street, Smithfield. One of the first large commercial buildings in the southern part of St John Street, most of which were not erected until after the opening of Smithfield Market and were to do with the meat industry, it was knocked down after only a few years for the creation of the market.

The building was faced in red brick, with Box stone dressings (Ill. 292). Earp's ornamentation was concentrated on the two rather narrow doorways on St John Street and Charterhouse Lane (Ill. 293), goods access being supplemented by a crane over the Charterhouse Lane entrance. In the basement was a fireproof store; the ground floor contained offices and a sale-room, and the first floor the boardroom, secretary's room and authors' rooms. Bookbinding was carried out on the floor above, lithographic printing on the third floor, and the top two floors were given over to engraving and copperplate printing. There was a steam-powered lift from the ground to the top floors.

291. St John Street, junction with Skinner Street, 1950s, showing warehousing at Nos 223–227 (left) and 231–243; Hugh Myddelton School and Northampton Buildings in background

292, 293. London Printing & Publishing Co. works, St John Street. G. Somers Clarke, architect. Looking north-east in 1860, at the time of its completion, and (right) detail of stone-carving by Thomas Earp. Demolished

John Tallis (1818–76), bookseller, printer and publisher, occupied No. 100 St John Street, Smithfield, from 1846, and later No. 97 also, where Richard Willoughby & Co., who printed his London Street Views, had been based. Possibly Tallis took over Willoughbys. In 1853 Tallis's business was incorporated as the London Printing & Publishing Co. Ltd. He was initially co-managing director with his partner E. T. Brain, his general manager for several years, but also apparently a bookseller and publisher in his own right, in Paternoster Row and at Leipzig. Tallis seems to have fallen out with the board over his venture to set up a rival to the new Illustrated London News, the Illustrated News of the World, in 1857–8, but he remained a substantial shareholder in the company at the time the new premises were built. (fn. 2)

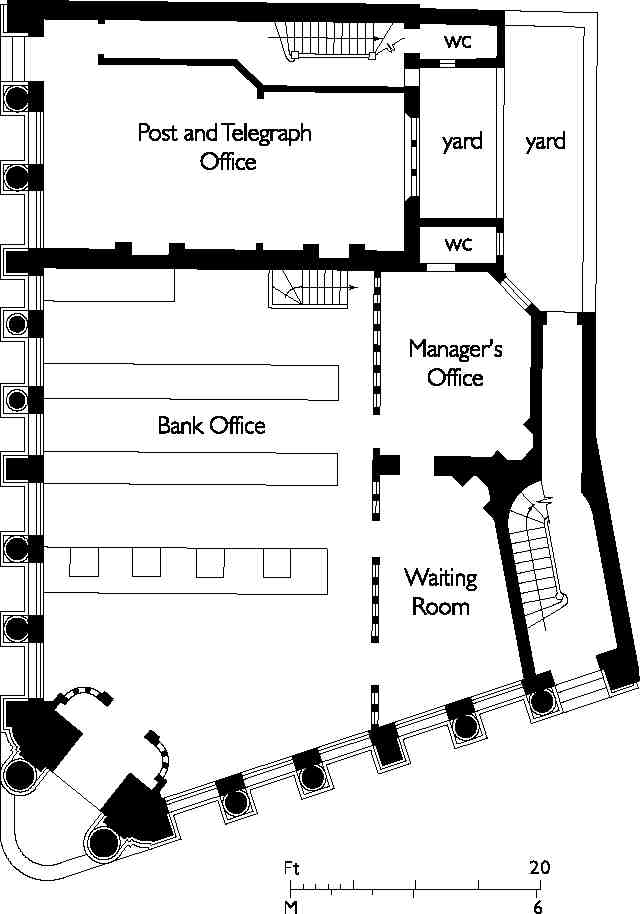

294. Nos 2–6 St John Street, ground-floor plan in 1872

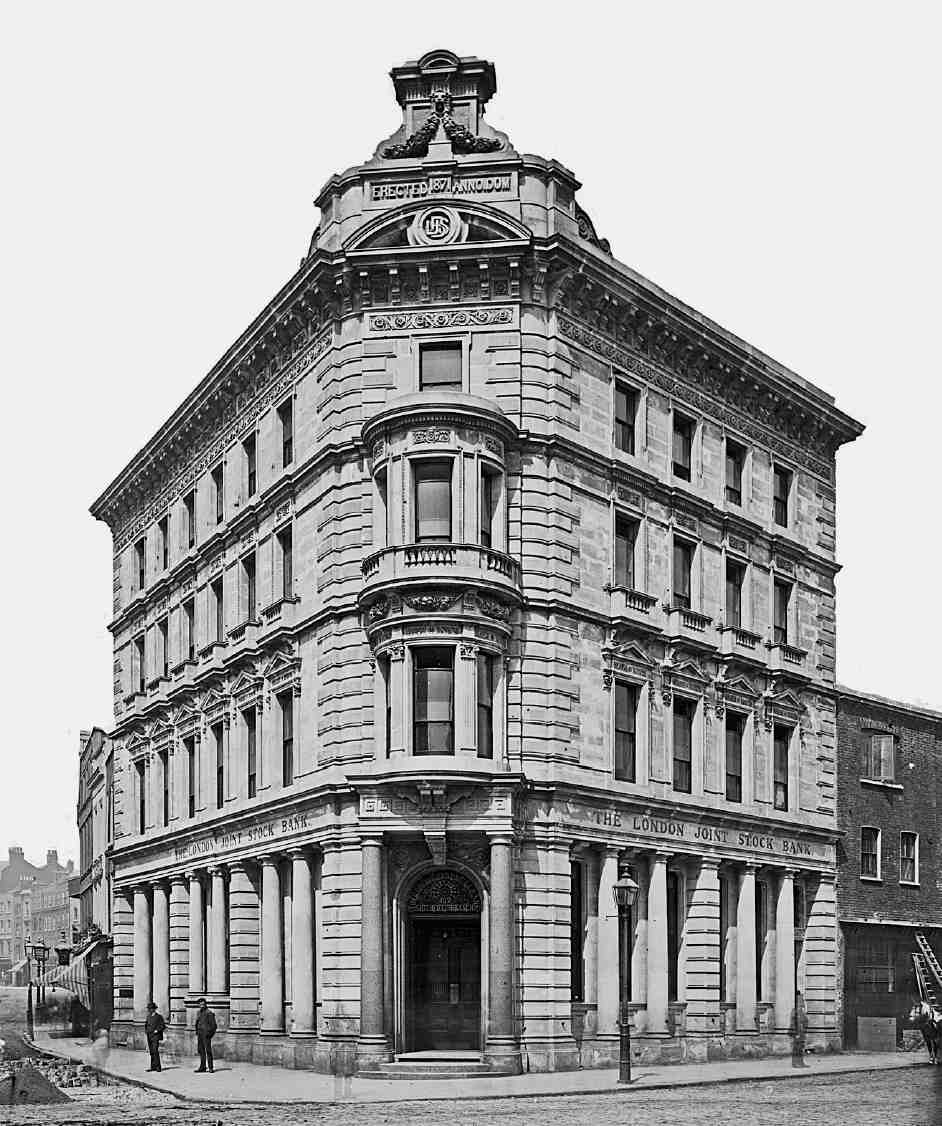

Nos 2–6. This was built in 1871–2 as a branch of the London Joint Stock Bank, to serve the meat-trade firms drawn to the area by the new Smithfield Market, replacing a temporary branch further up St John Street, opened in 1869. (fn. 3) The architect was Lewis Henry Isaacs, and the builders Browne & Robinson (the contractors for Smithfield Market). It is in the Italianate style favoured for banks (Ills 274, 295), with a heavily rusticated façade of Portland stone, ornamented with carving (by Bell & Almond). The iron girders and joists were supplied by Matthew T. Shaw & Co., and Dennett & Co. laid the fireproof floors. Part of the ground floor was originally sublet as a Post and Telegraph Office, with its own entrance (Ill. 294). The upper floors, originally living quarters for the bank manager, were later converted to offices (now No. 89 Charterhouse Street). (fn. 4)

295. Nos 2–6 St John Street, former London Joint Stock Bank, c. 1872

No. 16, the former Cross Keys inn, was rebuilt in 1886–7 for Lovell & Christmas, provision merchants. (fn. 5) The builders were J. Lidstone & Sons; the architect's name is not known. It has been closed as a pub since the Second World War, and was occupied during the 1980s as the London headquarters and library of the Communist Party of Great Britain, before being refurbished as offices in the early 1990s (Ills 263 and 296). (fn. 6)

Nos 18–20. This Gothic-style warehouse of 1886–7 follows the much-copied pattern established by William Burges twenty years earlier in Upper Thames Street, of two arched openings rising through several floors (Ill. 296). It was built speculatively by Richard Curtis, builder and contractor of Aldersgate Street. Curtis went bankrupt during the work, and the building was completed for his mortgagee, the Nineteenth Century Building Society, who let it in 1889 to S. Oppenheimer & Co., sausage-skin manufacturers. (fn. 7)

296. Nos 16–26 St John Street (right to left) in 2004

297. No. 22 St John Street in 1946

298. No. 22 St John Street, first-floor plan in 2004

No. 22. The exact date of construction is not known, but the house is evidently of the early eighteenth century (Ills 296, 297). It appears to be the survivor of a row of three similar houses (Nos 18–22, formerly 109–111, see Ill. 257), mentioned in the will of Frances Ashton, née Chew, proved in 1727. The house passed in 1748 on the death of her daughter to the charity set up by her late sister Jane Cart, widow of James Cart, distiller, who lived further south in St John Street, on the site later occupied by the London Printing & Publishing Co. All three houses may have been built for their brother William Chew, also a distiller. (fn. 8)

On the upper floors the house retains much of the original plain panelling and box-cornices. The open-string staircase, which has a narrow light-well to the side, has slender turned balusters and square newel posts with turned finials.

The house was in commercial use by the 1820s, and was occupied from then until the 1890s by a succession of wire-workers, manufacturing being carried on in a workshop in the back yard. (fn. 9)

No. 24 was erected in 1863–4 for George Penson, provision merchant, replacing the Golden Lion inn (see Ill. 257). Fronting the street is a tall, narrow house faced in white brick, with, originally, a ground-floor shop (Ill. 296). At the rear is a yard, originally covered by a glazed iron roof, and a warehouse, set at right-angles on the L-shaped site. (fn. 10)

No. 26. The origins of the house are uncertain. It appears from several features to date from the early nineteenth century, but may in carcase be older. The site is shown on Ogilby & Morgan's map (1676) as occupied by an inn, the Swan with Two Necks, and this inn continued in existence until the late 1770s or 80s. It was then acquired by a distiller, William Hooper, whose son Richard continued in business here as a wine and brandy merchant and distiller into the early nineteenth century. The property was let to another distiller, William Windus, for a few years around 1810, re-occupied by Hooper and finally sold by him in 1822 to Richard Hardwick Browning, oil merchant, whose firm stayed until the late 1880s. Whether the rebuilding or modernization of the inn was carried out by the Hoopers, Windus or Browning is not known. (fn. 11)

The house is faced in stock brick, the only exterior ornament being the doorcase, which has a reeded wooden surround and curvilinear fanlight (Ill. 296). It has a staircase and some panelling of early nineteenth-century type.

At the rear, the yard was completely roofed over for oil storage by Brownings, latterly described as oil and spice merchants. (fn. 12) The premises were occupied from the 1890s by a succession of provision merchants, who built baconsmoking stoves in the yard. Though varying in size, these are of characteristic form, with iron bars across the smokechamber for hanging hams, and doors at high level. The stoves are of varying date. There were three by about 1910, and another was erected in 1923; six were in existence by 1948. (fn. 13)

299. Farmiloes (Nos 34–36 St John Street, far right) and adjoining buildings at Nos 38–50 in 2004

In 1994 the buildings in the yard were converted to the St John restaurant and bar. The bacon-stoves were retained, the largest being opened up for the insertion of a bar, another for a food counter, and a third adapted as a store-cupboard. The conversion was designed by the restaurateur, Fergus Henderson, a trained architect. (fn. 14)

Nos 28–36 (formerly Farmiloes). George Farmiloe, the son of a Clerkenwell watchmaker, set up as a window-glass cutter about 1824 in St John's Lane, moving from there in the 1830s to a shop in St John Street (then numbered 114, see Ill. 257) and subsequently developing his business as a builder's merchant, specializing in lead and glass. Between 1848 and 1856 he acquired in stages much larger premises at Nos 34–36 (then numbered 118–119 and 121), comprising two old shops and the former White Hart inn with its large wagon-yard. (fn. 15)

In 1892, the year after Farmiloe's death, the firm acquired the Windmill Inn and other adjacent buildings at Nos 28–32. (fn. 16) The inn-yard and stables were used as a stained-glass and embossing works until the 1930s, when the site was redeveloped; the inn and other buildings fronting the street remained until the 1950s. (fn. 17)

By the late nineteenth century Farmiloes had several works and warehouses apart from St John Street: the Island Lead Mills in Limehouse; factories for colour, sanitary appliances and plumbers' brass work close by in Eagle Court; and a wharf, first at Wapping, then at Blackfriars. (fn. 18) The company remained in St John Street until 1999, relocating to Mitcham that year.

300. Farmiloes. Staircase in 2004

301. Farmiloes. View across covered yard to rear warehouse, 2004

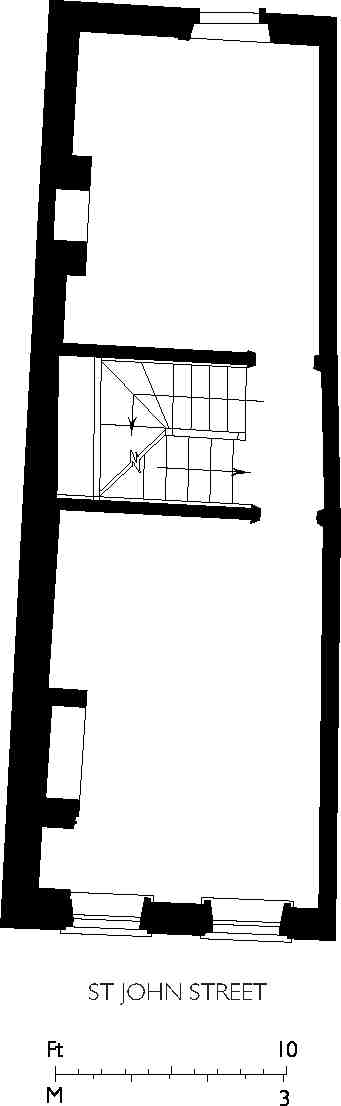

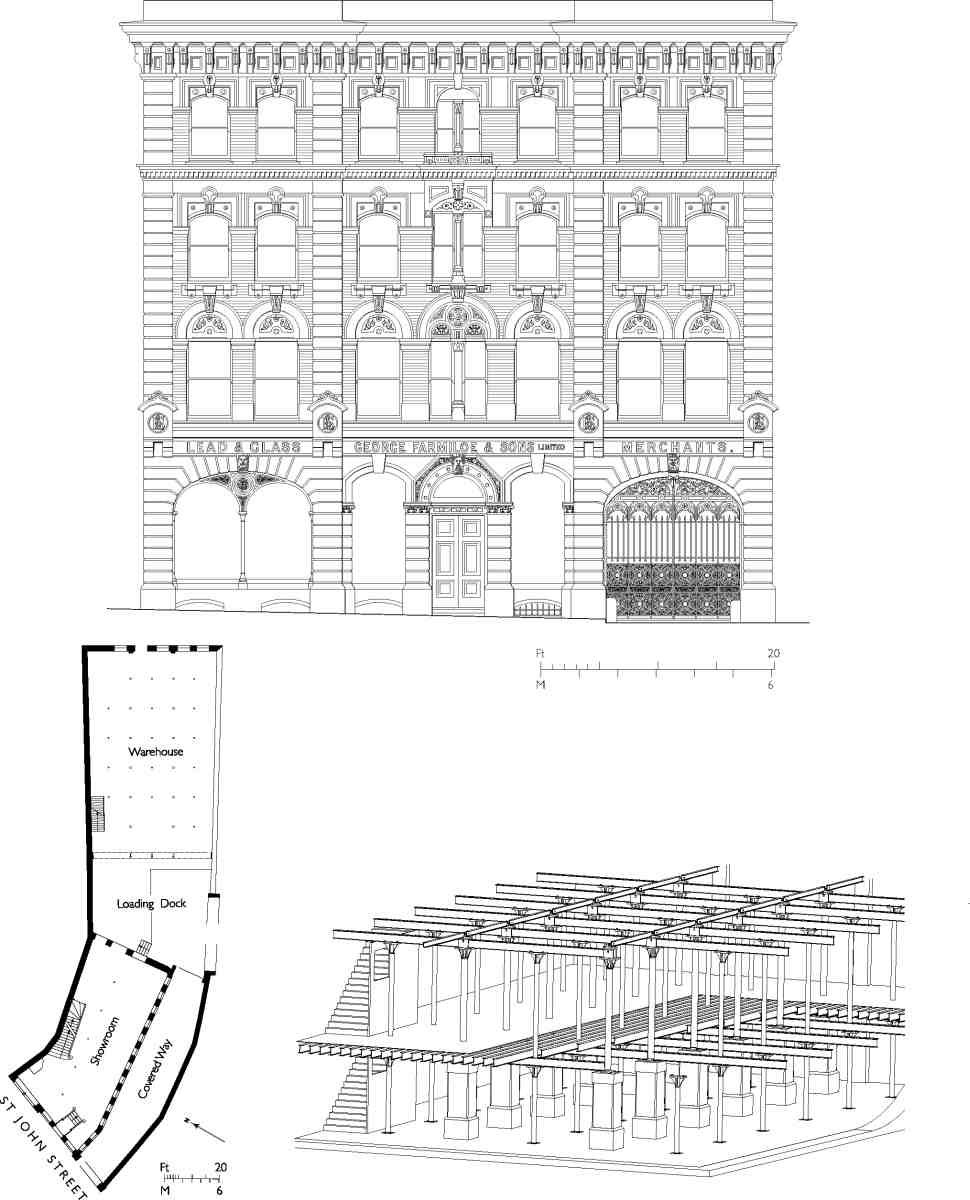

302. Façade, plan and cut-away view of ground floor and basement of rear warehouse. Farmiloes, Nos 34–36 St John Street. Lewis Henry Isaacs, architect, 1868

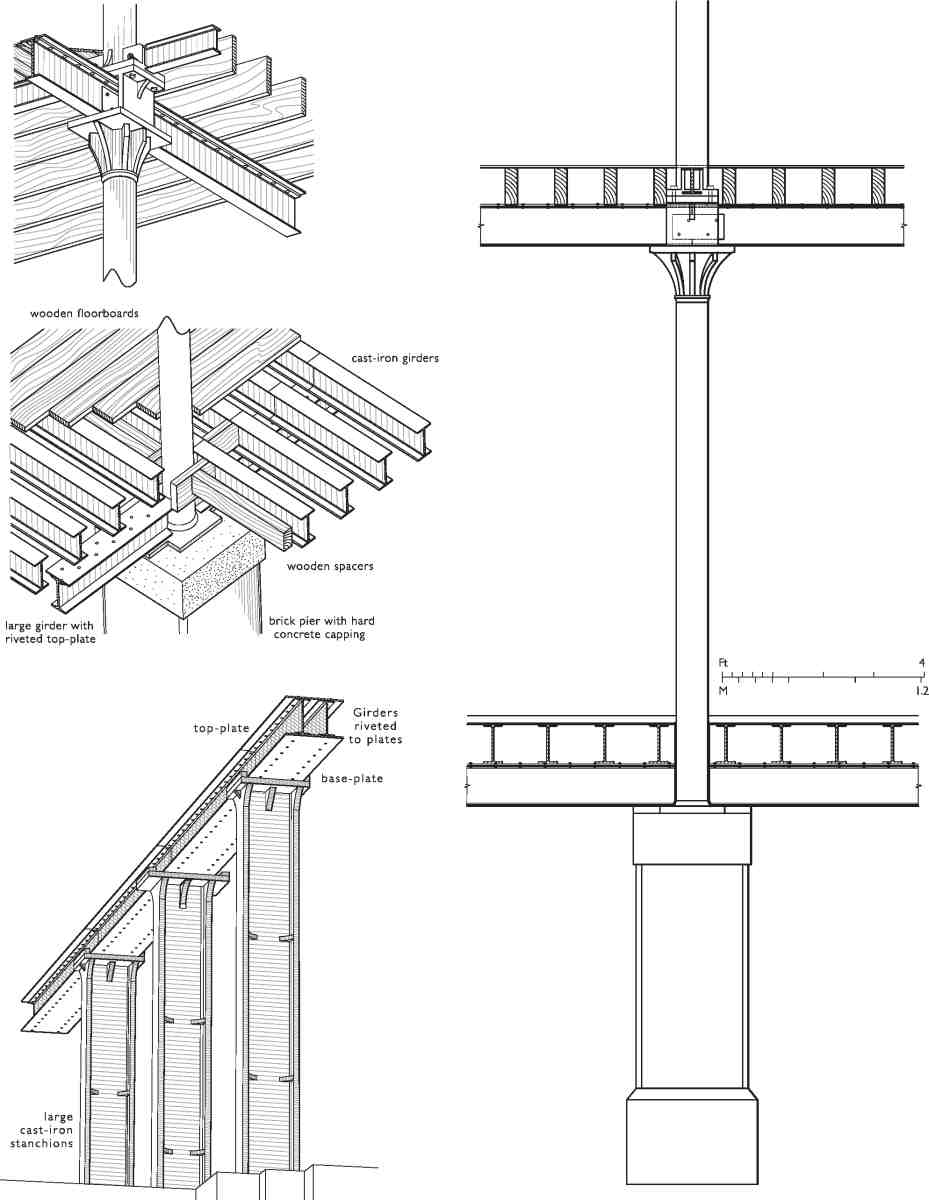

303. Details of structural ironwork in ground floor and basement of rear warehouse

304. Nos 42 and 44–46 St John Street. Charles Bell, architect, 1877

George Farmiloe replaced some or all of the St John Street buildings with warehouses in the early and mid-1860s, (fn. 19) but in 1868 these were destroyed by a fire, in which neighbouring buildings to the north were also damaged. (fn. 20) Rebuilding began almost immediately.

The buildings of 1868 (Nos 34–36) consist of a groundfloor showroom with offices above, and warehousing and workshops at the rear, separated by a yard and loading-bay, roofed at high level in iron and glass and approached from the street through decorative iron gates (Ills 301, 302). The architect was Lewis Henry Isaacs, and the builders, on a contract of slightly under £13,000, were Browne & Robinson. (fn. 21)

The Italianate palazzo-style façade to the street is executed in Portland stone, white Suffolk brick and polished Aberdeen granite, with much decoration, incised and in relief (Ills 299, 302). All the carving was executed by a Mr Seale, presumably John Wesley Seale of Walworth. (fn. 22) (The original lettering above the front entrance, g. farmiloe & sons, was evidently replaced by the present george farmiloe & sons limited, in more condensed lettering, after the firm was incorporated as a limited liability company in 1892.) Inside, the staircase between the showroom and offices has a cast-iron balustrade, decorated with flower motifs and the monogram F & S.

In the rear warehouse the weight of the materials stored, including lead on the ground floor, demanded unusually strong construction. The ground floor, designed to take a load of 10cwt per square foot, is carried by closely spaced wrought-iron girders of I-section, strengthened by plates riveted to the flanges, parallel with the long axis of the building. These girders rest on transverse iron beams of similar construction, three of which span the width of the floor. The transverse beams are supported by cast-iron columns alternating with brick piers, or brick-encased columns supporting the girder-ends (Ills 302, 303).

On the ground floor the warehouse is open to the yard, the walls above being carried by wrought-iron box girders, made up of I-section beams sandwiched between plates and riveted together, and four H-section stanchions of cast iron (Ills 302, 303).

Farmiloes' warehouse is one of the earliest examples of this 'built-up' or 'compound' mode of wrought-iron girder construction, which became known as Phillips' Patent Girder System (or Phillips' Girders) from the City firm of William and Thomas Phillips, who acquired the patent from its inventor, Julius Homan. Phillips's supplied all the ironwork at Farmiloes, most likely from their yard in Belgium. (fn. 23)

In 1937–8 the Windmill Yard buildings were replaced by a five-storey warehouse, of reinforced-concrete construction, clad in grey flint brick, designed by H. E. & E. D. J. Mathews. (fn. 24)

305. Former bacon stoves in Smokehouse Yard, Nos 44–46 St John Street, in 2004

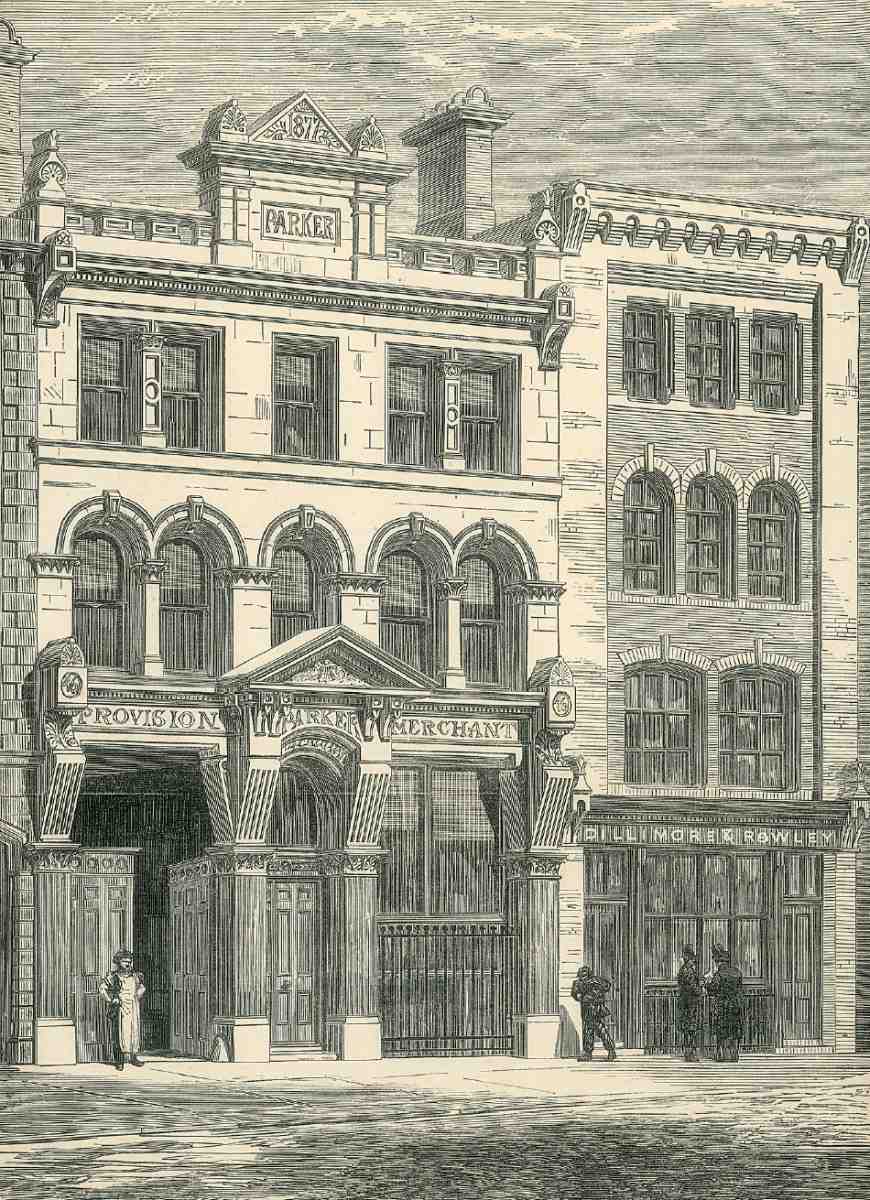

Nos 38–46. This short run of warehouses was built in two phases, in 1877 and 1890, replacing buildings damaged by the fire at Farmiloes in 1868. Nos 42 and 44–46 were built first, No. 42 for Dillamore & Rowley, cork manufacturers, Nos 44–46 for Edward Richard Parker, provision merchant. Both were designed by the architect Charles Bell, and erected by J. Woodward of Finsbury. Nos 38 and 40 followed in 1890. They were built by E. Collins of Finsbury, again for Parker. (fn. 25)

306. No. 78 St John Street in 2004. Alfred Allard, builder, for William Bodecker, developer, 1891–2

Of the four buildings, the largest and most interesting is Nos 44–46. Illustration 304 shows the original treatment of the façade, the ground floor with over-scaled embellishments in Portland stone, above polished granite pilasters. The upper part, faced in Bath stone, was slightly less extravagant. At the back of the warehouse, which included offices and a manager's flat, are outbuildings ranged round a courtyard, originally bacon stoves, stores and stabling but now converted to offices and business units (Smokehouse Yard, Ill. 305). The basement, extending over nearly the whole of the site, was used for storing provisions.

Nos 48–76 were mostly built speculatively in the 1950s and 60s as factories and warehouses and occupied by firms in the meat industry. (fn. 26) The exceptions are Nos 52–54, an office development of the late 1980s, and No. 72, a house and shop probably of the 1830s.

No. 78 was erected in 1891–2 by Alfred Allard, builder, of Pentonville, for William George Bodecker or Boedecker, presumably as a speculation. Bodecker, who briefly appears in the Post Office Directory as a 'builder' with an office in Queen Victoria Street, had acquired the ground as a cleared site. (fn. 27) The architect responsible for the design is not known. The new building was evidently used at one time by the printers Perry Gardner & Co., whose letterhead in the late 1890s carried an engraving showing both No. 78 and—rebuilt to match—No. 80, as 'warehouse and stock rooms'. (No. 80 was not in fact rebuilt.) (fn. 28) Palmer & Co., tyre manufacturers, took up occupation about 1903. (fn. 29) The façade, with a Gothic-style opening spanning three floors, is faced in red wire-cut brick. The ground-floor incorporates the entrance to Mitre Court (Ill. 306).

The five houses at Nos 80–88 make up the most substantial Georgian remnant of lower St John Street (Ill. 307). Not all can be dated with much accuracy.

No. 80, though described as 'new erected' in a deed of 1786, seems to be a rebuilding carried out in the early 1770s of a house bought in 1753 by John Watson, distiller. The long plot provided space for stills and stores behind the house. After Watson's death in 1763, his widow Alice and son John carried on the business here in partnership, and about 1772 Mrs Watson appears to have taken up residence in the house adjoining (on the site of No. 78). (fn. 30) Both houses were probably rebuilt at this time as a pair: Tallis, in the late 1830s, shows the next-door house to have been similarly proportioned, though by that date embellished with pilasters and perhaps stuccoed (Ill. 257).

307. Nos 80–92 St John Street in 2004

Several interior features, including the cut-string staircase, are consistent with a 1770s date. The chief feature of interest is the Adam-style ceiling in the first-floor front room, which forms part of a neo-Classical decorative scheme including panelling and window-shutters.

308. East side of St John Street, c. 1910–15. Wagons delivering willows to Waldens' basket-works at Nos 78–80

A fragment of blue-and-white trellis-patterned flock wallpaper, dating from the second half of the eighteenth century, was recovered from the first floor in 1992. (fn. 31)

Illustration 308 shows a delivery of Somerset willow to Waldens' basket-ware factory at No. 80 in the early twentieth century. A. & G. Walden Bros., makers of wicker trucks and trolleys, were based here from 1902 until c. 1960.

Nos 82 and 84. These two houses are closely matched in style and probably erected at or about the same time. No. 82 was certainly built in the mid-1750s, replacing half a dozen small buildings comprising 'Marriott's tenements' or Rising Sun Alley. (fn. 32) From about 1768 the house, with a rear workshop and warehouse, was occupied by Edward Jones and Samuel Ware, leather merchants. Ware and his son Richard Cumberlege Ware remained in business here for many years, taking over the present No. 84 and enlarging the workshops and warehousing in Hat & Mitre Court.

309. No. 82 St John Street. First-floor front room in 1996

310. Nos 94–100 St John Street (left) in 1935; Milner & Craze, architects, 1934–5 (demolished). Nos 90–92 to right

The two houses were still occupied by leather-workers in the 1950s. R. C. Ware was the father of the architect Samuel Ware, who trained under James Carr of Clerkenwell.

Though documentary evidence is lacking, it is likely that No. 84 (on the site of an inn called the Goat and Harp) was also rebuilt (or at least modernized and refronted) in the 1750s. Both houses retain wooden chimneypieces, with lugged surrounds and ornamented with fret patterns, and other internal details characteristic of the period (Ill. 309). Externally, the smaller house, No. 84, is distinguished by brickwork laid almost entirely in header bond, in contrast to the conventional Flemish bond of No. 82.

No. 86. Surviving internal features suggest a 1720s or 30s date, but there is no documentary evidence to support this, and the house has probably been refronted.

No. 88 (formerly 88 and 88a) is an asymmetrical pair of houses, probably built about 1837 when after a rapid succession of tenants, including at least one absconder, both houses (then numbered 150 and 151) were taken by Coats & Brockmer, linen-drapers and silk mercers, John Coats staying for several years. (fn. 33) In 1878 a Home for Working Girls was established here, with 37 beds for girls 'anxious for the comfort and cleanliness of the home'; this had closed by 1886 and the houses reverted to commercial occupancy. (fn. 34) In the early 1900s rear warehousing was erected on the site of old cottages in Hat and Mitre Court for the latest tenants, Gedge & Co., polishers and lacquerers, who were based here until the 1960s. No. 88 was refurbished in 1998 as a bar-restaurant, with a singlestorey glazed rear extension (by Karen Byford of Design Solution, architects), which overlooks the Tudor outer wall of the Charterhouse. (fn. 35)

Nos 90–92, now converted to offices and apartments, was built in 1925–6 by Walter Gladding & Co. for the City Sites Development Co. as a warehouse or factory. The architect was Ronald Aver Duncan of Percy Tubbs, Son & Duncan, and the design was intended to relate to the domestic scale of the adjoining houses through the use of small windows on part of the front (Ill. 310). The capstanlike decorative feature over the doorway, and the main window surround (faced with yellow marble chippings), were made by F. de Jong & Co. Ltd. (fn. 36)

Nos 94–100 (demolished) and No. 100. The present building, No. 100, an office block of 1990 by Hamilton Associates, has none of the quirky character of its predecessor demolished in 1983, numbered 94–100 (Ill. 310). Designed by the church specialists Milner & Craze, this was built in 1934–5 by Gee, Walker & Slater Ltd as offices, workshops and a garage for the Stepney Carrier Co., delivery vehicle contractors. It consisted largely of a depot for the maintenance and repair of the company's vans, carrier cycles and tricycles, but also incorporated a service and filling station for public use. The front was faced in 'Mulberry' brick, with bright blue faience window-sills. The three-dimensional lettering along the open facia, made of metal box-sections and coloured cream and blue, was manufactured by Frederick Sage & Co. Ltd. (fn. 37) The building was latterly used as a carpet warehouse.

Nos 102–106 are described under Clerkenwell Road on page 392.

311. No. 1 Leo Yard. Sketch by Michael F. Clements, 1992

312. No. 144 St John Street in 2006

Clerkenwell Road to Compton Street

The frontage from Clerkenwell Road to Compton Street was formerly divided between three or more landholdings, principally those of the Charterhouse and the Earls (later Marquesses) of Northampton (see Ill. 4 on page 11). Between Clerkenwell Road and Great Sutton Street the history of the landownership is uncertain. Some of it at least, at the corner of St John Street and Clerkenwell Road, belonged in the 1770s to Jacob Houblon of Great Hallingbury in Essex, whose descendants the Archer Houblons sold it in the late 1820s and early 1830s. (fn. 38)

On the corner itself is the former Criterion public house at Nos 116–118, described under Clerkenwell Road on page 402. North of this are a number of undistinguished houses, variously altered and mostly undatable with any precision. The largest of these is No. 120, formerly the Priory Hotel, greatly enlarged in the 1880s, when it became a lodging-house. (fn. 39)

Of the remainder, Nos 122–126 were refronted if not largely rebuilt in the late 1850s, when long leases were granted, in a very plain and old-fashioned manner. (fn. 40) No. 124, crudely refronted again in the 1950s, was eccentrically remodelled in 1997–8 by the architect Charlie Sutherland of Sutherland Hussey. (fn. 41) No. 122 retains its old shopfront, probably of the 1850s. No. 128, its front much patched, is probably eighteenth-century, and No. 130 eighteenth- or early nineteenth-century.

No. 1 Leo Yard (formerly 122a St John Street) is a slightly puzzling building, on account of its particularly substantial, part-iron construction and recessed ground floor (Ill. 311). It was built in the early 1900s, apparently for the polish makers Gedge & Co., who used it as a warehouse and French polish factory. (fn. 42)

Nos 132–154 occupy the St John Street frontage of the former Charterhouse estate (see Ill. 388 on page 280).

313. Cannon Brewery. St John Street frontage in 1925, looking west from Pollards' shopfitting works. Partly demolished

314. Cannon Brewery. Nos 148–176 St John Street, elevation as in 1927

Nos 132–136. This was built in 1959–60 to designs by White & Traviss, architects, as Thessco House, the London branch of the Sheffield Smelting Co. Ltd, refiners, smelters and recoverers of precious metals from industrial waste and sweepings. The firm had a long Clerkenwell connection, and had been in Berry Street since the early nineteenth century. (fn. 43)

No. 138 was probably built in the eighteenth or early nineteenth century, and the stucco window surrounds on the first and second floors added about 1860, when a long lease was taken out by the occupant of some years, a pork butcher. The building was gutted in the late 1990s and converted into a factory-style studio and house for an artist and his family (by Trevor Horne Architects). (fn. 44)

Nos 140–142. A speculative commercial building of 1937–9, this was designed by Herbert Wright for A. Class & Son, who rebuilt much of the Charterhouse estate during the inter-war period. (fn. 45)

No. 144 (then numbered 38) was the original premises in the late 1830s and early 1840s of the tobacco manufacturers Lambert & Butler. The house was refronted and partly rebuilt in 1930–1 by C. P. Roberts & Co. as offices, workshops and showrooms for the Permanent Bronzing and Restoring Syndicate Ltd, electroplaters (Ill. 312); the architect was A. Burnett Brown, estate surveyor to the Charterhouse. Its good quality neo-Georgian façade is of red brick laid in English bond, with gauged brick and stone dressings; the original casement windows have been removed, but the ornamental shopfront has been preserved. (fn. 46)

No. 146. The carcase of the building consists of the former Hoop and Adze (later Crown) public house, probably rebuilt c. 1803 and later stuccoed, and two-storey workshops at the rear, built in the mid-1890s for a firm of electroplaters who had leased the recently closed pub. (fn. 47)

These very modest structures were transformed in 1996–7 by Derek Wylie Architecture into an open-plan family dwelling, but with a large office to meet planning requirements for 'live/work' rather than purely residential use. The style is minimalist, and contrasts sophisticated finishes and fittings with rough bare brickwork. The glazed ground-floor front, looking on to the office, has been recessed behind a security gate. (fn. 48)

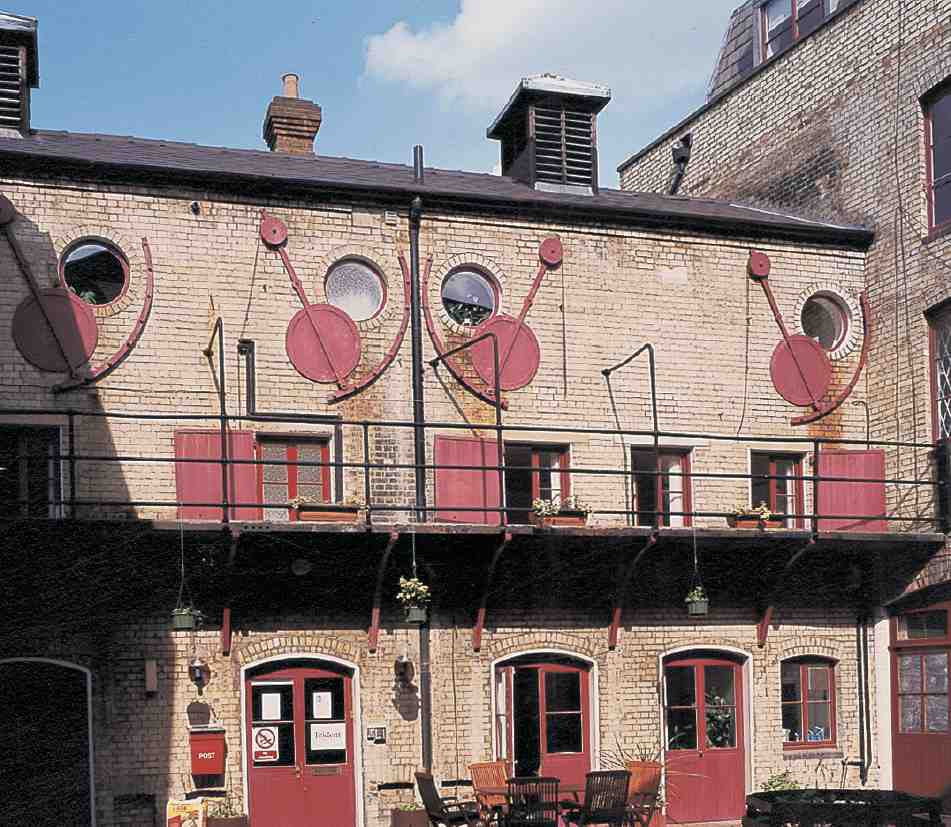

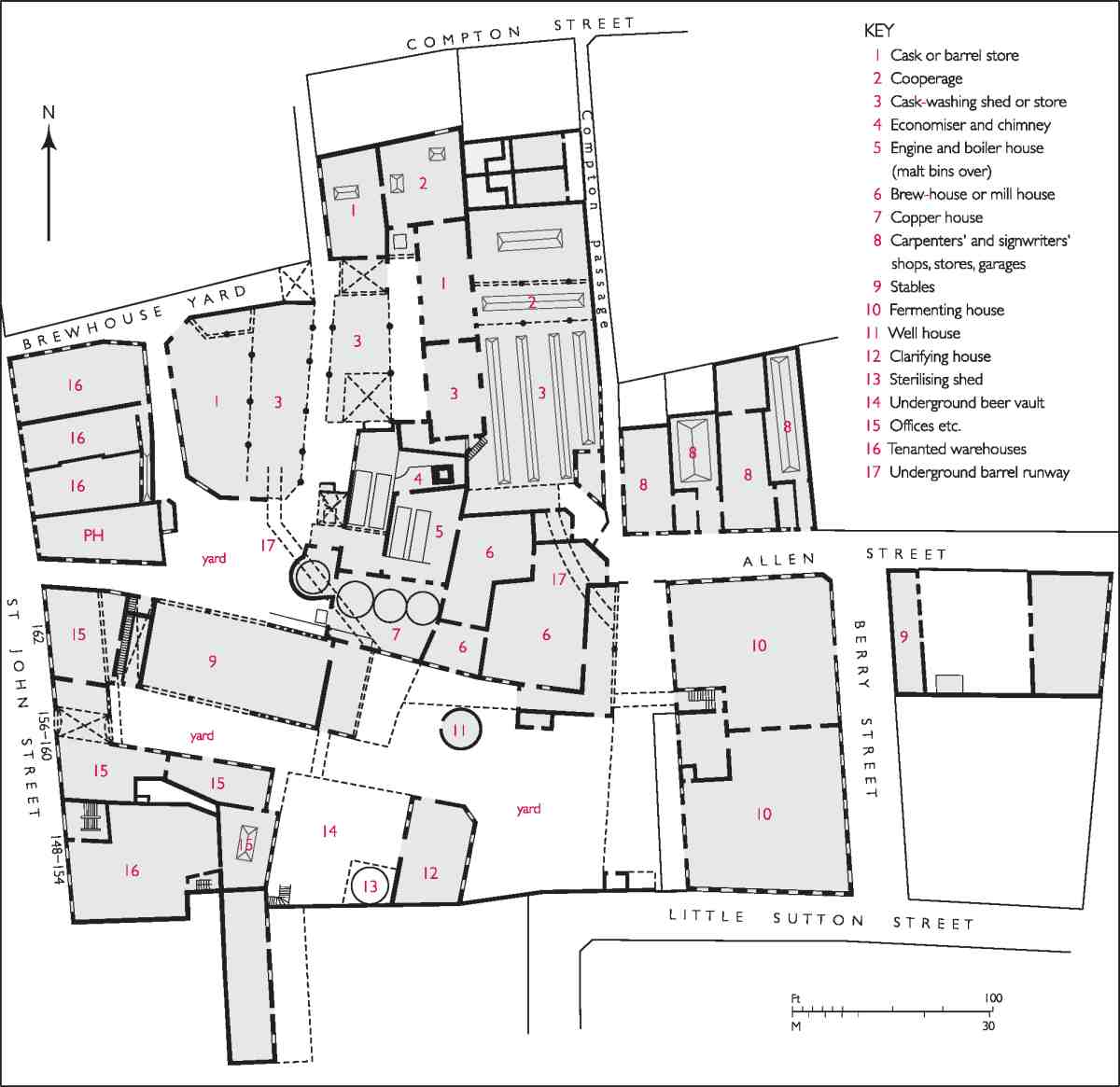

Cannon Brewery site. The Cannon Brewery originated with a brewhouse attached to the Unicorn inn, which stood towards the northern end of the site. It was in existence by the early 1670s. Known as the Horseshoe by the 1740s, it was the twelfth-largest of the 52 principal London breweries in 1759, producing more than 23,000 of their combined annual output of 975,000 barrels. In 1764 the brewery was acquired, with other property in the vicinity, by Samuel and Rivers Dickinson of Chick Lane, whose family were long-established brewers and maltsters in London and Hertfordshire. Their father, Rivers, had been an associate of Edward Godfrey, proprietor of the brewery for many years until 1715. (fn. 49)

Under the Dickinsons and their sons the brewery was enlarged, and the Unicorn rebuilt and renamed the St John of Jerusalem. Rivers Dickinson is traditionally credited with establishing the name Cannon Brewery, to distinguish it from another family business, but no documentary evidence is known to support this. Retirement and bankruptcy brought the partnership to an end by 1818, when the brewery was sold at auction, and shortly afterwards the premises were broken up for various commercial uses. (fn. 50)

By 1822 Henry Gardner had established a brewery on part of a former vinegar yard adjoining the former Horseshoe brewery on the south. In partnership with his brothers William and Philip, he gradually expanded the premises, taking over most of the Dickinsons' former site. It appears to have been the Gardners' establishment that was first referred to as the Cannon Brewery, appearing as such on the map accompanying Cromwell's Clerkenwell in 1827. In 1863 the Gardners sold the brewery and 59 associated public houses for over £110,000, to George Hanbury and Barclay Field.

315. Cannon Brewery. Looking east from the main gates towards the fermenting house, 1990. Brewery Yard Offices to right, former stables and beer stores to left

Hanbury and Field made a number of additions and improvements during the 1870s, of which one building, the Brewery Yard Offices, survives. In 1876 the business was reconstructed as the Cannon Brewery Co., subsequent growth and expansion being driven by William Wroughton and Andrew Motion, who became partners in the firm in 1876 and 1889 respectively. They aggressively pursued the tied-house system, buying up over 100 public houses, and in 1895 floated the Cannon Brewery Co. Ltd, raising £ 1m in share capital. (fn. 51) Some new building had been undertaken in the 1870s under Field & Co., and this was followed by a major programme of rebuilding and expansion in the 1890s, when the site was extended eastwards to Berry Street and Pardon Street.

In 1930 the Cannon Brewery Co. was acquired by the Taylor Walker group, subsequently part of Ind Coope (Allied Breweries from 1963). Seriously damaged during the Blitz of 1940–1, the brewery resumed production after the war, but closed in 1955. In the early 1960s the northern part of the brewery was demolished for a new headquarters building, Allied House, facing St John Street, and an NCP car park. Allied House, designed by Llewellyn Smith & Partners, was an eight-storey slab, unrelated in scale and character to its neighbours. This and some of the old brewery buildings were used by Allied as offices, stores and garaging, until its departure in the late 1980s, following which Allied House was demolished and much of the brewery site cleared.

The oldest surviving building is the former Brewery Yard Offices (Ills 315, 316). This was erected directly behind the old main entrance in 1874–5. Built of soft red brick with stone dressings, with an ogee-capped turret and bracket clock, it comprised a counting-house and offices above a basement beer-cellar. Carved barley and hops decorate the capitals of the doorway, a theme continued in coloured mosaic on the floor inside (Ills 318, 320). The architect is not known; the contractor was Thomas Elkington of Golden Lane. (fn. 52)

Two large blocks, now demolished, were built in 1891–3, to designs by the architects Francis Chambers & Son. These were a warehouse fronting St John Street, on the site of the later Allied House, and a range immediately behind, comprising stables and stores for forage and beer (Ills 313, 315). Holland & Hannen were the contractors, as they were for all the major building works at the brewery during its enlargement and reconstruction over the next six or seven years. This programme, costing about £250,000, was overseen not by Chambers but by William Bradford & Sons, the specialist brewers' architects. (fn. 53) Bradford, it was announced in 1893, had prepared designs 'for the whole of the works', a model of which was exhibited in 1894. Chambers & Son, however, were still evidently retained to do certain work, dealing with the London County Council in 1895 over the erection of a brick 'corridor', and the two firms may to some extent have been working in conjunction. (fn. 54)

The entrance block at Nos 156–160, originally offices and caretaker's accommodation, was designed by William Bradford & Sons and built in 1894–5. In general terms, this followed the stylistic lead set by the Chambers & Sons warehouse adjoining, but with some extra ornamental work, including panels of moulded brick and particularly elaborate entrance gates, constructed of wood with applied iron decorations (Ill. 317). (fn. 55) The range adjoining to the south, Nos 148–154, was designed by Bradfords for the Cannon Brewery Co. in 1914, but not erected until 1924–5. Its first occupants in 1927 were the shopfitters Pollards, who used it for storage, and installed the present shopfronts. (fn. 56) Illustration 314 shows the frontage of the brewery as completed in the 1920s.

At the rear of the site, backing on to Berry Street between Dallington and Northburgh Streets, is the former fermenting house, No. 16 Brewhouse Yard (Ill. 319). Designed by Bradfords, this was erected in phases in 1895–8 on the site of model dwellings erected only a few years earlier (Sutton Buildings, see page 289). (fn. 57)

The fermenting house was arranged as basement beer stores, ground-floor packing rooms, yeast or 'brewers' rooms on the first floor, skimming rooms on the second, and laboratories with fermenting and tank rooms on the third—all with white glazed-brick walls to keep conditions cool and hygienic. Not all the building had solid flooring: the workers moved between the slate fermenting vessels on boarded gangways. The upper floor, lined with matchboard and partly top-lit by louvres and lanterns, housed the coolers and refrigerators, and the roof held a 36,000– gallon cast-iron water-tank. To take the weight of the plant, the floors were of concrete arch construction, supported on cast-iron circular columns and wrought-iron compound girders, and the building was divided internally into three separate blocks, connected by an open iron staircase and double iron doors. Built of load-bearing brick, with a facing of soft red brick, its façade of giant Tuscan pilasters and round-headed window recesses complemented the entrance buildings on St John Street. The fermenting house was connected with the main brewery building in the middle of the site (now demolished) by an iron and steel bridge. A short section of the bridge has been preserved as a 'feature' in the landscaped area in front of the fermenting house.

316. Cannon Brewery, block plan in 1933

After the brewery's closure the fermenting house was used for warehousing, and latterly by Christie's as an exhibition space. It was restored and refurbished in 1999–2000 by the architects Finch Forman, and is now the London headquarters of the architects BDP (Building Design Partnership).

317. Main entrance block, Nos 156–160 St John Street, in 2004

318. Capital on façade of Brewery Yard Offices, in 2004

319. Fermenting house (now No. 16 Brewhouse Yard), in 2004

320. Mosaic floor panel in Brewery Yard Offices, in 1993

Cannon Brewery, St John Street

Since 2001 the remainder of the site has been redeveloped as housing, initially to a scheme conceived by the Dutch architect Erick van Egeraat, who himself designed an office block for the north end of the site. A compatriot, Easchus Huckson, was to have designed the landscaping. Egeraat's offices, intended to be draped in a flexible stainless-steel mesh which would have revealed the structure beneath like a 'lifting skirt', were ultimately not built. (fn. 58) The architects Hamilton Associates carried out the first phase of the redevelopment, Brewery Square, which was completed in 2002 and comprises apartments and town-houses grouped around a courtyard. The main elevations have a modular arrangement of pre-cast units clad in copper, zinc and glass (Ills 271, 273). The development of the site continues at the time of writing (2007), with plans by the property company Carrot Ltd for a five-storey mixed-use building to comprise one- and two-bedroom apartments with offices and retail space. (fn. 59)

On the corner of Compton Street, the former George public house, No. 180, and the house adjoining, No. 178, were built in 1901 for the publican, H. H. Finch. The architect was W. A. Aickman. (fn. 60)

Compton Street to Percival Street

Between Compton Street and Percival Street the buildings occupy a narrow island site, formed in the 1690s by the creation of what is now Agdon Street. The present buildings were nearly all purpose-built as factories and warehouses, for which the site, with easy rear access, was well suited. They are mostly now converted to apartments or offices.

Nos 240–244 occupy the former frontage of Northampton Place, a narrow street or passage cut through the northern end of the island site about 1804 to connect the west end of Percival Street with St John Street, leaving a small detached triangle of ground, later planted and used for a cab-stand and public convenience. (fn. 61)

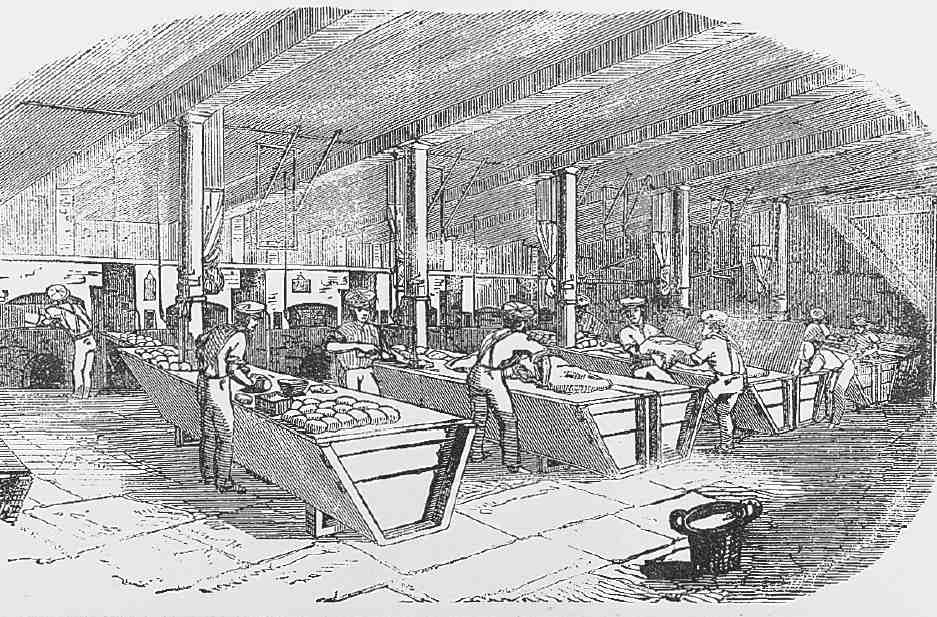

321. League Bread Co.'s bakery, St John Street, in 1848

The long-vanished League Bread Co.'s bakery (Ill. 321) which stood on the site of the present Nos 214–222, was set up in 1846–7 to supply a chain of shops opened throughout London, established on the repeal of the Corn Laws in 1846 'to carry out the principles of Free Trade in Corn and to supply the consumer with good and cheap bread'. Using unadulterated, unbleached flour and fresh yeast, the League company aimed to produce bread as good as home-made or 'farm-house'. It was not a longterm success, and seems to have come to an end in 1854, the premises subsequently becoming a biscuit factory. (fn. 62)

The bakery, which extended along the backs of the houses in St John Street, was incorporated into Thomas Glover & Co.'s gas-meter factory at Nos 214–222 in the late 1860s, and demolished in the 1930s for a new extension.

Of the present buildings on the island block, the southernmost range, Nos 182–204, was the London headquarters of the Scholl Manufacturing Co., the footcare and medical equipment specialists, until the company's takeover in the late 1980s. Only part was built for Scholl. The earliest building is Nos 190–194, erected in 1910 for the United Yeast Co., which also acquired and rebuilt No. 188 in 1919, adding a rooftop canteen in 1925–6. Nos 182–186 was built in 1913 as Pioneer House by George Parker & Sons, builders, of Peckham. This was evidently their own development, let to Rasmussen Webb & Co., watch-material manufacturers. (fn. 63)

Scholl moved from Granville Square to the former United Yeast buildings early in 1930, expanding into Pioneer House over the next few years. Nos 196–204 were rebuilt for Scholl by Parkers in 1937–9, to designs by H. Yolland Boreham of Boreham, Son & Wallace. With minor embellishments at Nos 190–194, Boreham produced a nearly symmetrical façade with a central stairtower, covering Nos 190–204 (Ill. 322). The administrative offices at the top of the new building included an office for F. J. Scholl, with Georgian-style panelling and oak-clad ceiling beams.

322. Nos 182–204 St John Street, former Scholl building, in 2006.

323. Nos 214–222 St John Street in the 1920s. Alexander Peebles, architect, 1867–8

Nos 206–212 (Paramount House). This was built in 1936–8 as a speculation by the builders John Laing & Son Ltd, who were then expanding into industrial and commercial development and property investment. (fn. 64) Designed by Culpin & Son, the new building was faced in red brick, and was named Wigton House, commemorating the firm's Cumbrian origins. It was occupied for manufacturing and warehousing by a variety of companies, including Scholl. (fn. 65)

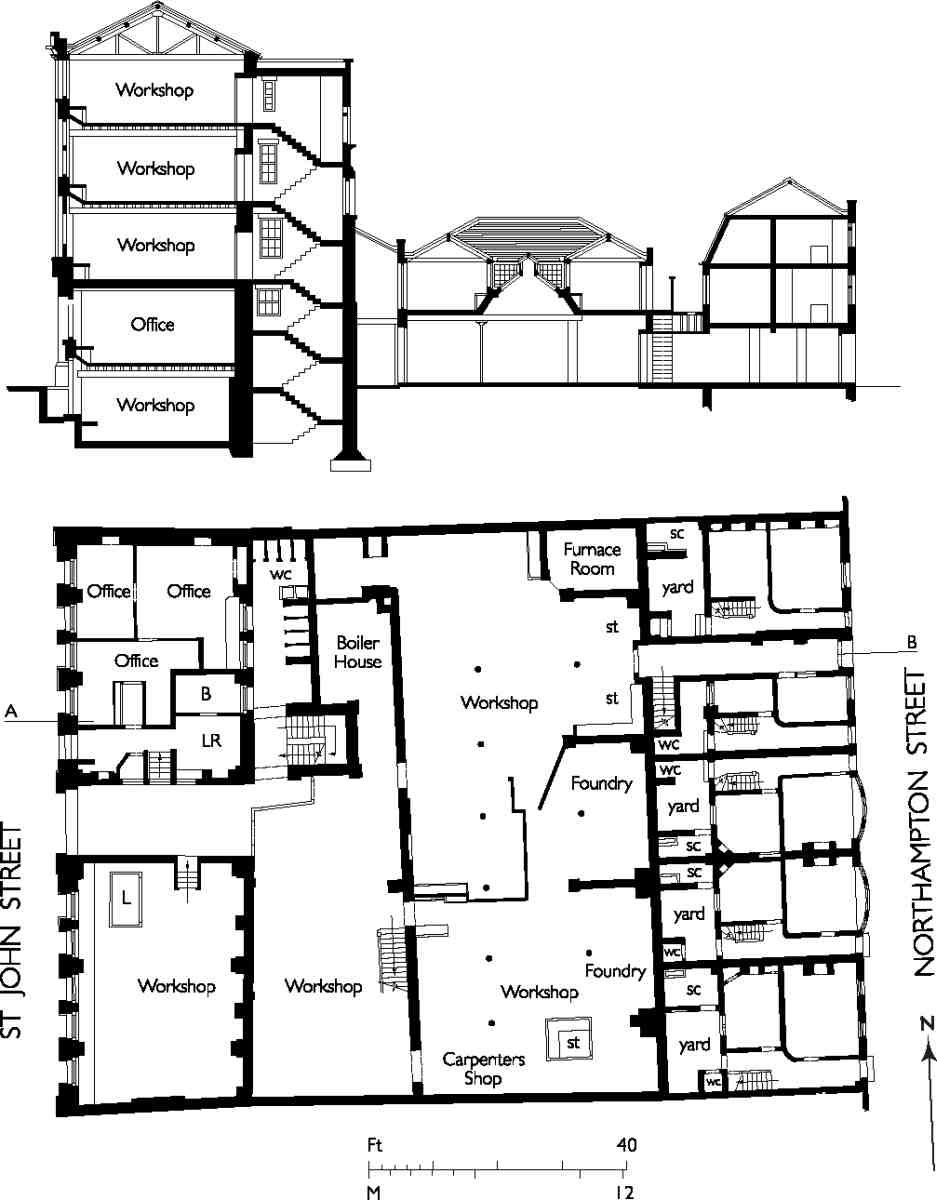

324. Nos 214–222 St John Street, plan and section in the early 1900s

In the late 1990s Wigton House was converted to apartments by Warner Lofts, the front glamorized with whitepainted render and glass balconies, and renamed Paramount House (see Ill. 286).

Nos 214–222 (Walmsley Building). These former industrial premises have been occupied since 1965 by the City University, formerly the Northampton College of Advanced Technology. The name commemorates Dr Robert Walmsley, the first principal of the Northampton Institute, as the college was originally called.

The part of the building fronting the street was built in 1867–8 for Thomas Glover, gas-meter manufacturer, to replace his factory in Suffolk Street (now Hayward's Place). Glover himself died before the completion of the building, but his firm remained there until the early 1900s. Designed by Alexander Peebles, it has an Italianate-style façade of white brick and artificial stone, ornamented with roundels over the ground-floor windows depicting medals awarded to Thomas Glover & Co. at international exhibitions (Ill. 323). (fn. 66)

At the rear, the former bakery of the League Bread Co. was adapted as part of the meter works. Illustration 324 shows the works with the site of the baking ovens now adapted for founding. At the east end of the site, fronting Northampton (now Agdon) Street, is shown a row of early nineteenth-century houses, which had been acquired on lease by Glovers, along with the factory and old bakery, with an eye to rebuilding for industrial purposes. These survived until 1934, when they were replaced by a fourstorey, red-brick factory and warehouse for J. M. Doughty & Sons, art-metal workers and brassfounders, who had taken over Glover's premises about 1903. The new building, extending across the centre of the site and obliterating the old bakery, was designed by R. G. Muir. (fn. 67)

Nos 224–232. This former factory was built for Scholl in 1956–8 (Westmore & Partners, architects), on the site of long-demolished buildings already empty and ruinous in the late 1930s. (fn. 68) Originally faced in 'semi-rustic' bricks, the building was re-fronted in 1989 with white render and dark glass, as part of its refurbishment by Brandon-Jones, Robinson, Sanders & Thorne for Trace Computers (now Trace Group).

Nos 238–240 were built in 1889–90 as the George and Dragon public house and coffee-tavern, replacing an early nineteenth-century inn of the same name and the adjoining house (Ill. 266). The redevelopment, for the publican, William Pierpont, was designed by the pub specialist Harry Isaac Newton, and carried out by the builder W. L. Kellaway. By 1893 the coffee-tavern was under separate management as dining-rooms, but these were later converted to industrial use; this part of the building (No. 238) is now offices. (fn. 69)

Two features of the original interior decoration which survive are a wall panel of painted tiles (by Webb & Co. of Euston Road) and mosaic flooring, each depicting St George slaying the dragon (Ill. 325). The mosaic was brought to light and restored during the refurbishment of the building as the Peasant, one of London's first 'gastropubs'. (fn. 70)

Nos 242–244 is a four-storey red-brick building of 1930, erected as the Northampton Plating Works. The architect was W. T. Walker, of Walker & Mitchell.

North of Skinner and Percival Streets

From Corporation Row north to the Angel the road retained its rural ambience until the late eighteenth century, but by the early 1840s had been completely built up and absorbed into the new suburban districts of northern Clerkenwell and Pentonville, its character essentially residential. In its rural days, passing through the fields between London and the still separate town of Islington, crossing the New River, this northern half of St John Street was known as the Islington or Chester road. From 1818 it was called St John Street Road, and in 1905 was formally merged with St John Street and renumbered.

325. The Peasant, No. 240 St John Street (former George and Dragon public house), in 1993. Tiled decoration by Webb & Co., of c. 1890

326. St John Street, from Skinner Street to Lloyd's Row

Since the Second World War, many of the early nineteenth-century terraces have been swept away for redevelopment, breaking up what must have been a wearying monotony of dullish houses, though already peppered with comparatively ornate late Victorian rebuildings, chiefly of pubs. Several of these survive, including the flamboyant Old Red Lion of the late 1890s (Ill. 269). One no longer in existence was the Coach and Horses of 1899, by J. W. Brooker (Ill. 267), which stood at the north corner of Myddelton Street. The first major new monuments to appear were the Smithfield Martyrs' Memorial Church in the 1870s, a Gothic landmark bombed in the war and since demolished, and the Northampton Institute of the 1890s, the nucleus of the present-day City University (see pages 313, 316). A handful of factories or warehouses dating from the 1900s to the 1930s contribute to a little more diversity, but the public-housing schemes of Finsbury Borough Council are the overwhelming factor in the disrupted architectural character of the street. At the north end, the late 1970s Angel Centre clearly belongs to Pentonville Road, with its arterial-road appearance, rather than to St John Street.

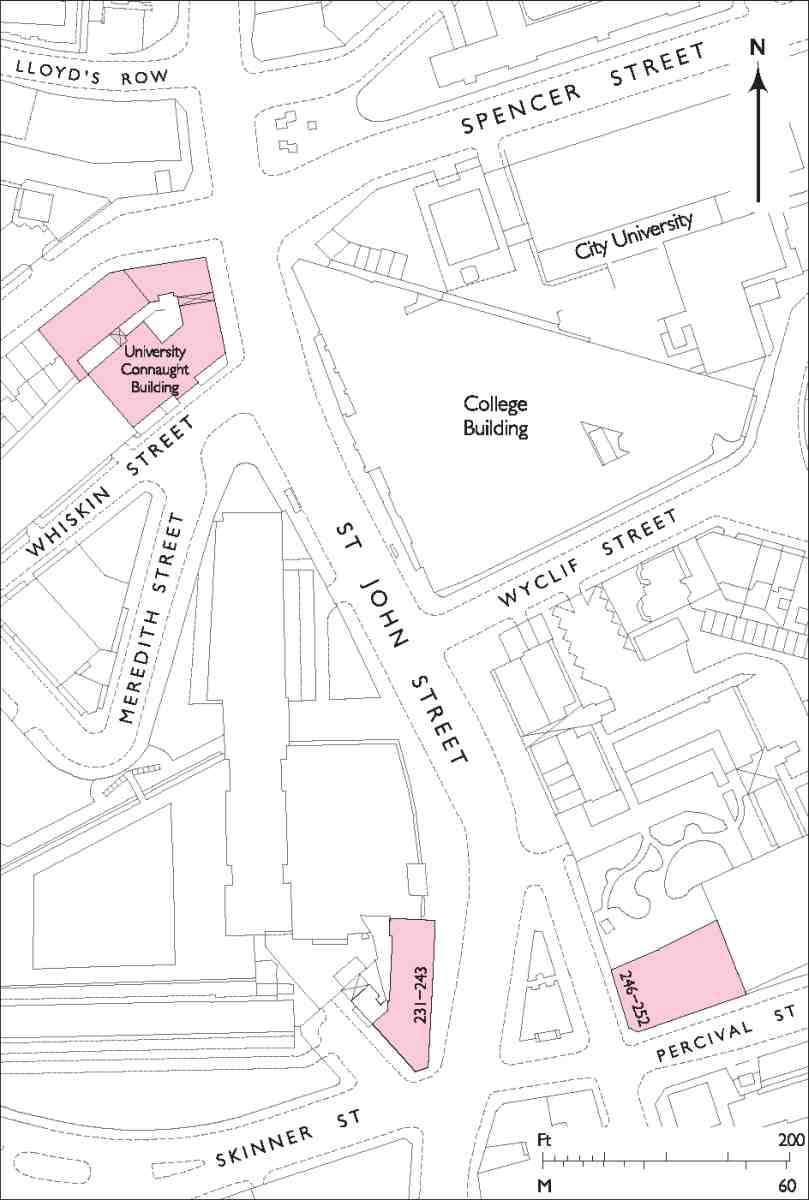

Beyond Skinner Street, the frontage of the street has largely been subsumed into public-housing estates (covered in Survey of London, vol. xlvii), but towards the junction with Rosebery Avenue nineteenth-century terrace-houses remain (Ills 326 and 468 on page 336). On the corner with Skinner Street itself is a former factory of 1909, at Nos 231–243, built for John Wilkins & Co., metalworkers, replacing old houses they had occupied for some years (Ill. 291). The architect was Walter H. Woodroffe. (fn. 71)

327. Nos 335–345 St John Street in 2007

328. Nos 347–351 St John Street in 2004. Nos 353 and 355 adjoining to right; Nos 357–365 far right

329. Nos 367–371 St John Street in 2004; Nos 357–365 to left

North of the Finsbury Estate, between Whiskin and Myddelton Streets, is the City University's new School of Social Sciences, completed in 2004. Designed by Stanton Williams on 'low-energy' principles, it replaces the Connaught Building, built in 1932 for what was then the Northampton Polytechnic, and later extended (Ill. 269). The Connaught Building (by Campbell-Jones, Sons & Smithers, architects) contained laboratories and workshops for chemistry and specialist manufactures including lenses, clocks and watches. (fn. 72)

The terrace-houses, on the former Lloyd Baker and New River Company estates, are of several dates (Ills 327–329). Nos 347–351, the earliest, were built in 1819–21 for Isaac Wright, gentleman, and Joseph Wilson, victualler.

330. No. 399 St John Street, former butchers' shop, in 2006

The site was part of a field belonging to the New River Company called Cow Layer, which had a small reservoir of 1805 adjoining. Known at first as Caroline Place, presumably in honour of the Queen, they are in a typically plain late Georgian style. The lease included a narrow passage to the south (now a gap between Nos 345 and 347), which originally led to a yard and privy behind. They were followed in 1833–4 by Nos 353–363, on Lloyd Baker ground, erected by Benjamin Matthewson of Hoxton, builder; No. 365 was presumably built at about the same time. (fn. 73) Both rows resemble the contemporary houses in Amwell and Great Percy Streets, where first-floor recessed window arches and other features were adopted by the Lloyd Baker Estate to match the New River Company's houses. The northernmost brick-and-stucco row at Nos 367–371 date from the late 1840s, part of the development of Nos 96–110 Rosebery Avenue, adjoining (originally Myddelton Place). (fn. 74) The present No. 371 is a rebuilding of 1977–8, when it and No. 369 were converted by Sadler's Wells Theatre to a box-office and administrative offices.

South of Caroline Place, the remaining stretch was built up in 1860–1, following the closure of the reservoir in 1857, as part of the redevelopment of Cow Layer and the frontage to its south, which had also been acquired by the New River Company. The principal developer was Henry Rydon, the creator of Highbury New Park, who laid out a new street—Rydon Crescent—across the site, joining St John Street and Myddelton Place. Between 1859 and 1862, Rydon and his associates built 42 new houses here, in St John Street (Nos 313–345), Rydon Crescent, Lloyd's Row and Myddelton Place. (fn. 75) Nearly all of these were pulled down for the Spa Green development in the 1930s and 40s, the six forlorn houses at Nos 335–345, built by John George Bishop, being the only survivors. (fn. 76) Their heavy stucco detailing contrasts with the earlier houses adjoining to the north.

Beyond Nos 377–379 (built in 1895 with Nos 197–199 Rosebery Avenue), Nos 381–399 are the only surviving New River Company houses on the street north of Rosebery Avenue. Mostly of the standard type found on the company's estate, they were constructed in 1823–4 by George Bishop, a Holborn bricklayer, for Daniel Toohey of Clerkenwell, victualler. (fn. 77) No. 381, with a broad, late Georgian elevation, is set back from the road in a yard behind two-storey workshops; it was built in 1823–4 and was at first called Arlington Cottage. Although used as a builder's yard for many years from the 1850s, the yard and outbuildings may originally have been livery stables, as they were occupied in the 1830s and 40s by the proprietors of livery stables near by in Arlington Street. These stables were probably supplying a need arising from the rebuilding of the Angel in 1819–20, when its stabling was greatly reduced. No. 399 was probably much rebuilt about 1845 for John Bland, a butcher, and it remained a butcher's shop from then until the 1990s. (fn. 78) It retains an attractive shopfront and interior fittings, installed in 1928 by J. Cannon & Son, builders and shop-fitters of Stoke Newington (Ill. 330). (fn. 79)

On the corner of Pentonville Road, the site of New Inn Farm and some of the stabling belonging to the Angel, was redeveloped in the 1820s with a dairy (Goose Yard). In the same period, the short length of frontage between this and Chadwell Street belonging to the New River Company was built up with houses. All this has disappeared. In its place is now the Angel Centre, a development by London Merchant Securities, which acquired the New River Co. Ltd, owner of the former New River Company estate, in 1974. Designed by Elsom Pack Roberts & Partners and built in 1979–83, this consists of a large office block on the corner of Pentonville Road, let to British Telecom in 1984, and a smaller, neoGeorgian block to the south, occupied by the National Probation Service. (fn. 80)

On the east side, the frontage between Percival Street and Rawstorne Street is mostly taken up by two large developments reaching back to Northampton Square: Finsbury Borough Council's Brunswick Close Estate, and the City University's College Building (formerly the Northampton Institute). Both of these are described in Chapter XI. Nos 246–252, on the corner with Percival Street, were built in 1911–12 as a speculation by the Pentonville builders, Perry Brothers, and occupied by Henry Mead & Sons, wholesale stationers, and later by the City University. The building was converted to flats in the mid-1980s and named College Heights. (fn. 81)

Beyond the City University buildings, at the junction with Wynyatt and Rawstorne Streets, is No. 292, the Queen Boadicea public house, formerly the New Red Lion and then the Bull, a rebuilding of 1923–4. (fn. 82)

Most of the eastern frontage further north belonged from the early seventeenth century to the Brewers' Company, as trustees of Dame Alice Owen's Charity. The individual buildings there up to the junction with Goswell Road are described in Chapter XII.