The Court of Chivalry 1634-1640.

This free content was Born digital. CC-NC-BY.

Richard Cust, Andrew Hopper, 'Introduction: guide to users', in The Court of Chivalry 1634-1640, ed. Richard Cust, Andrew Hopper , British History Online https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/no-series/court-of-chivalry/intro-guide [accessed 9 May 2025].

Richard Cust, Andrew Hopper, 'Introduction: guide to users', in The Court of Chivalry 1634-1640. Edited by Richard Cust, Andrew Hopper , British History Online, accessed May 9, 2025, https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/no-series/court-of-chivalry/intro-guide.

Richard Cust, Andrew Hopper. "Introduction: guide to users". The Court of Chivalry 1634-1640. Ed. Richard Cust, Andrew Hopper , British History Online. Web. 9 May 2025. https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/no-series/court-of-chivalry/intro-guide.

In this section

The Court of Chivalry 1634-1640: guide to users

The Court of Chivalry's records for the period 1634-1640 have been reconstructed on a case–by-case basis from the archives at the College of Arms and Arundel Castle. Details of 738 cases have been recovered, but in most instances what survives is only a fraction of the full run of case papers.

Each case begins with an abstract summarising the main details, followed by blocks of calendared material. These blocks cover initial proceedings, the plaintiff's case, the defendant's case, the sentence, or settlement of the case by arbitration, and the submission by the defendant. This material is then followed by a summary of surviving court proceedings and notes giving further details of the parties involved. The content of each of these blocks is described more fully below. Finally, the surviving documents are listed, along with the people and places mentioned and topics covered in the case.

The calendar of documents summarises case papers or, where there are passages of particular interest, transcribes them in full. The aim is to provide a calendar which is sufficiently complete to satisfy the needs of most researchers. The entire text is fully searchable, both separate from and alongside the rest of British History Online’s content, and a full list of names, places and topics covered is provided in the three consolidated alphabetical indexes.

A published collection of all the abstracts and lists of case papers, is available in R.P. Cust and A.J. Hopper, Cases in the High Court of Chivalry, 1634-1640 (Harleian Society, new series 18, 2006).

This resource originally appeared as a website hosted by the University of Birmingham. It has been converted for publication on British History Online.

As with all publications on British History Online, the URL structure for the Court of Chivalry resource is deliberately designed to be user-friendly. The Court of Chivalry resource itself has the URL: www.british-history.ac.uk/no-series/court-of-chivalry. Each case within the resource has a URL that is formed of its case number and the surnames of the plaintiff and defendant, i.e. Case 1 Allen v Axtell has the following URL structure: www.british-history.ac.uk/no-series/court-of-chivalry/1-allen-axtell.

How to search

The entire text can be searched by keyword from the resource's table of contents using ‘Search within this publication’. The landing page also has a table of contents which includes every case and the indexes. To find a name, place or subject from the index amongst the cases, type or paste the surname, place name or subject into the ‘Search within this publication’ field found in the table of contents.

For academic researchers

The material in this resource offers scope for a series of well-defined research projects using primary source materials. There are opportunities to explore a rich variety of topics relating to the social and cultural history of the early seventeenth century, from the language of insult and defamation to the conduct of disputes and duelling, from contemporary understandings of what it meant to be a gentleman to the social life of inns or parish churches. Alternatively one can carry out local studies on a county basis, or explore cases relating to a particular profession, or class of litigant.

For project and dissertation students

The material on the site offers scope for a series of well-defined research projects using primary source materials. There are opportunities to explore a rich variety of topics relating to the social and cultural history of the early seventeenth century, from the language of insult and defamation to the conduct of disputes and duelling, from contemporary understandings of what it meant to be a gentleman to the social life of inns or parish churches. Alternatively one can carry out local studies on a county basis, or explore cases relating to a particular profession, or class of litigant.

For genealogists and local historians

This resource provides a wealth of genealogical and biographical detail on litigants and witnesses. Each witness statement includes information on the individual's age, place of birth and how long he/she had lived at a particular location. Depositions offer local historians a wealth of circumstantial detail on social relationships and disputes within local communities.

Conventions

New style dating, with the year presumed to begin on 1 January, has been used in the case headings and abstracts; however, to provide greater precision for those researching cases in detail, in the calendars of case papers, old style dating has been used.

Summaries have been provided where documents follow a common form, where material is being repeated or can be condensed, or where the original document is in Latin. Full transcriptions are generally provided where the precise wording might be considered important, that is, for the most part, in petitions, libels, interrogatories, depositions and submissions (however, it should be noted that in the transcriptions redundant terminology, such as 'the said' has been omitted, and legal terms, such as 'producent' have been altered to the name of the person referred to).

In the transcriptions the symbol * has been used to denote passages which have been added to the original and < > to indicate passages which have been crossed out.

Throughout this web site, references without a prefix refer either to the numbered boxes of the Curia Militaris collection at the College of Arms, or to bound volumes at the college. References with the prefix EM refer to the Earl Marshal's papers at Arundel Castle. Manuscripts from other repositories are indicated with a prefix.

For full transcriptions and samples of many of the documents calendared here, see GD Squibb, The High Court of Chivalry (Oxford, 1956), appendix ix-xxv.

Glossary

arbitration

a hearing before referees chosen by the two parties to settle a dispute

bill of costs

itemized list of the expenses incurred by each party in the course of the case

bond

an agreement by which the party undertook to do what was required by the court on pain of forfeiting a stipulated sum of money (usually £100)

citation

an instruction by the Register of the court to all officers of the crown declaring that an individual had been summoned to appear before the court

definitive sentence

a document put forward by each side to the judges outlining the verdict that they sought

fiat

an abbreviation of fiat processus, this is the instruction by the Earl Marshal or his deputy, acting on the advice of the King's Advocate that a case should be allowed to proceed

King's Advocate

the most important court official responsible for promoting office cases (actions on behalf of the king or judge of the court), and also advising the Earl Marshal or his deputy whether process should be granted on an initial petition

interrogatories

questions drawn up by an advocate to be put to witnesses in order to establish the case being made by either plaintiff or defendant

letters commissory

a commission from the court to named persons requiring them to take evidence on behalf of a party in the case

letters remissional

a document taking exception to witnesses

letters substitutional

letters allowing one person to act in place of another, used mainly where the notary public administered interrogatories to witnesses in place of an advocate

libel

the plaintiff's initial pleading in which he usually establishes his own claim to gentility, explains the facts which constitute the cause of his action and pleads for relief from the court

notary public

an official authorized to draw up or attest copies of legal proceedings, in these cases often acting as the deputy to the Register in authenticating witness depositions

porrect

put forward in writing

Register

senior court official formally responsible for registering the acts of the court and preserving its records

submission

formal acknowledgement of wrongdoing and apology for this, usually performed by the defendant in public.

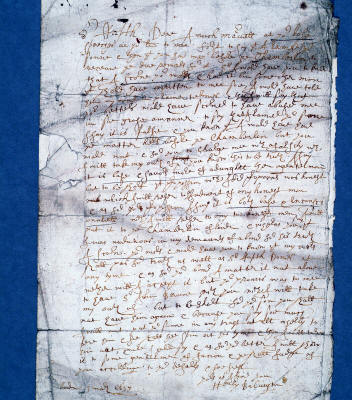

The notary's mark of Humfrey Jones, at the end of witness depositions on behalf of Henry Chaloner, the plaintiff in Chaloner v Lovell, case 102 (By permission of the Chapter of the College of Arms)

Procedure

Procedure in the High Court of Chivalry was similar to that used in the Court of Star Chamber and equity courts, such as the Court of Requests or Chancery. Plaintiffs would initiate proceedings by a libel, the equivalent of a bill of complaint; facts would be ascertained through presenting documentary evidence, or, more commonly, issuing interrogatories and taking depositions from witnesses. This material would then be referred back to the judges of the court who would pronounce on guilt and innocence. The main difference from common law procedure was that there was no use of juries.

To begin with, when the court was established on a regular footing in 1634, procedures were worked out as it went along, with the lawyers and court officials adapting to the influx of business. Early proceedings were recorded in English as well as Latin; but by October 1634 the record was being kept exclusively in Latin, the language of the civil law and its routine had settled into the form described in more detail by G.D. Squibb in his The High Court of Chivalry (Oxford, 1956), chp.13.

G.D. Squibb's classic 1959 study The High Court of Chivalry

Initial proceedings

The majority of proceedings were instance cases, begun through a complaint by an outside party. In such cases the action began with the plaintiff presenting a petition setting out the nature of the offence against him, which in most cases involved 'scandalous words likely to provoke a duel', and also underlining his own claim to gentility, because only gentlemen could plead in the court. A few actions, however, were office cases, initiated by the King's Advocate, Dr Duck, or the Kings or Officers of Arms. In such cases proceedings began with the delivery of articles against the defendant; but thereafter the procedure was much the same as for instance cases. Once a petition had been presented a decision had to be taken by the senior judge, Arundel or Maltravers on the advice of the King's Advocate, on whether there was a case to answer. Notice that process should be granted was issued in the form of a fiat, often inscribed on the petition, which gave the Register of the court authority to issue a citation summoning the parties or their counsel to appear. In some 48 of the cases recorded here there is no evidence of process being granted, or of any further proceedings, which makes it likely that these were actions which fell at the first hurdle. On appearance before the court both parties were required to take out bonds, the plaintiff to prosecute the case to a conclusion and the defendant to appear when required and perform any sentence imposed by the court.

The next stage of the initial proceedings was for the plaintiff to deliver his pleading, known as the libel, in which again he set out the nature of the original offence and his own claim to gentility. This claim would sometimes be challenged by the defence as a means of invalidating the prosecution, in which case, if there was any doubt, the plaintiff would be required to produce proof of his gentility, most often in the form of a pedigree or evidence of the right to bear arms. This would then be investigated and certified as acceptable or unacceptable the Kings of Arms, although they did not usually report back until later, at the time when the plaintiff's and defendant's cases were being heard. At this initial stage the defendant would often enter a personal answer, giving his version of events, but also enabling the court to establish facts which were not disputed.

The normal ordering of the initial proceedings was as follows:

- 1. Petition or Advice of the King's Advocate

- 2. Fiat

- 3. Citation

- 4. Notice of citation

- 5. Plaintiff's bond

- 6. Defendant's bond

- 7. Libel

- 8. Summary of libel

- 9. Personal answer

The libellous letter of March 1637 in which Henry Babington told Sir Ralph Done that his actions 'savour more of the dunghill than a gentleman', produced to support Done's libel case 166 (By permission of the Chapter of the College of Arms)

The plaintiff's/defendent's cases

The court would then proceed to interrogate witnesses, taking each side's case in turn. Sometimes, with cases from London or the home counties, interrogation would take place before the court or in front of Sir Henry Marten, sitting in his chambers. However, in most instances the court would issue letters commissory appointing gentry named by the two parties to hear depositions before a notary public of the civil courts at a convenient local venue, often an inn. Each witness would be examined on a list of interrogatories provided by the parties, with the plaintiff's witnesses being examined on the articles in his libel and a set of defence interrogatories, and then at a later stage defence witnesses being examined on the basis of the defence and a set of plaintiff's interrogatories.

The resulting depositions, which sometimes ran to many pages, would be recorded and then returned to the court by the notary public. Once the process had been completed for the plaintiff, generally over a period of several weeks, the same thing would happen with the case for the defence. It was open to either party during this period to plead for a verdict on the evidence which had already been submitted, or to request that the whole matter be referred to arbitration. Pleas for an immediate verdict were not generally heeded, but the court was very keen to encourage arbitration, mindful of how destructive these disputes could be, particularly where the parties involved were substantial local gentry. There are numerous instances of cases being referred to senior gentry and noblemen in the hopes of achieving a settlement; and in 19 of the 126 cases where the outcome is known (15%) this was achieved.

The normal order of proceedings and case papers during these stages of the case was as follows:

- 1. Letters commissory for the plaintiff

- 2. Appointment of notary public

- 3. Defence interrogatories

- 4. Second set of defence interrogatories

- 5. Letters substitutional for the plaintiff

- 6. Preamble to plaintiff's depositions

- 7. Plaintiff's depositions

- 8. Notary public's certificate

- 9. Letters remissional

- 10. Defence

- 11. Letters commissory for the defendant

- 12. Plaintiff's interrogatories

- 13. Second set of plaintiff's interrogatories

- 14. Letters subsitutional for the defendant

- 15. Preamble to defence depositions

- 16. Defence depositions

- 17. Notary public's certificate

- 18. Arbitration

- 19. King of Arms' Report

The Crown Inn, Evesham, where William Dingley's witnesses were examined in September 1639 in case 161, Dingley v Maulten (Photograph: Richard Cust)

Sentence/arbitration

Once both sides had made their case they would submit a document known as a definitive sentence in which each put forward the sentence that he sought, leaving blank spaces for the insertion of fines to the king, and damages and costs to be awarded to the other party. These would then be filled in by the Earl Marshal or his deputy when sentence was pronounced. Both sides also submitted bills, detailing the expenses incurred in the case term by term which would become the basis for the court's award of costs. At this stage it was, again, open to the court to refer the case to senior local gentry for arbitration.

The normal ordering of proceedings and case papers during the sentencing stage was as follows:

- 1. Plaintiff's sentence

- 2. Defendant's sentence

- 3. Plaintiff's bill of costs

- 4. Defendant's bill of costs

- 5. Arbitration

The Leicestershire peer and Court of Chivalry judge, Henry Hastings, Earl of Huntingdon, who was called on to arbitrate in a number of cases relating to midlands gentry.

Submission

Where sentence was given for the plaintiff it generally also required that the defendant make a public submission of his guilt, either at quarter sessions, assizes or the local parish church, or at the venue where the original offence had taken place. In this he usually had to apologise fulsomely to the plaintiff for the original offence, acknowledge his honourable status and undertake never to commit a similar offence against him, or any other gentleman or noblemen.

This all-important event, the performance of which had to be certified to the court, provided the element of reparation of honour which was regarded as one of the principal functions of the court. Imprisonment was not part of the formal sentence of the court, but it was used regularly to deal with defendants who defaulted on the performance of their original bond, either by failing to appear, or by not paying the fines or performing the submission required in the court's sentence. There are numerous petitions from defendants incarcerated in the Marshalsea, begging for clemency from the Earl Marshal, which indicate that the court was relatively diligent in following up on non-performance of the terms of a sentence, usually prompted by an appeal from the plaintiff.

The final stages of the case were normally as follows:

- 1. Submission

- 2. Defendant's bond on submission

- 3. Certificate of submission

- 4. Defendant's petition

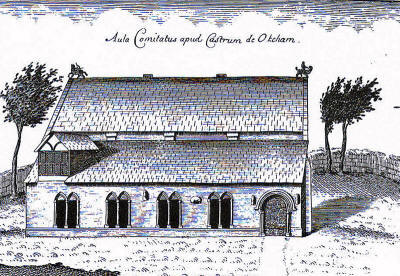

The hall of Oakham castle, venue for the Rutland assizes where Sir Henry Mynne performed his submission to William Lord Sherard before the judges on 29 July 1639, case 593 (From James Wright, The History and Antiquities of Rutland, 1684)

Proceedings

Records of the proceedings in court, taken down by the officials, have survived (mainly in Latin, but with a few early proceedings in English) for a large number of court days. These proceedings have not been transcribed or calendared in detail here, but where they survive for a particular a summary of the proceedings is given at the end of the case papers.

The court days for which records of proceedings have survived are listed below, with an asterisk denoting full sessions of the court. Dates are followed by manuscript references. Where these have the prefix EM this denotes that they are to be found amongst the Earl Marshal's papers at Arundel Castle. The remainder are in the archives of the College of Arms.

- 26 Feb* and 5 Mar 1633/4*: 7/16

- 1 Mar 1633/4*: 8/22a; 8/22b

- 14 Apr 1634*: 7/8; 7/9

- 26 Apr 1634*: 7/9

- Apr-May 1634*: 7/18

- 3 May 1634*: 7/10; 7/11; 7/12; 7/13

- 21 May 1634*: 7/12; 7/14

- 24 May 1634*: 7/15

- 7 Jun 1634*: 7/17

- 30 Jun 1634*: 8/23

- 20 Oct 1634*:1/1

- 13 Nov 1634: 1/13

- unknown date, 1634: 7/7

- 24 Jan 1634/5*: 1/2

- 9 May 1635*: EM348

- 30 May 1635*: EM349

- 9 Jun 1635: 8/24

- 16 Jun 1635: 1/13

- 19 Jun 1635: 1/13

- 20 Jun 1635*:8/25

- Jun 1635: R.19, fos. 390-399; 1/13

- Apr 1636*: 68C, fos. 64r-67r,

- 7 May 1636*: 68C, fos. 74r-83v

- 9 May 1636:68C, fos. 68v, 84r-88v

- 28 May 1636:68C, fo. 102r,

- 30 May 1636: 68C, fos. 101v, 102r

- May 1636: 68C, fos. 69r, 89r-100r, 102r

- 3 Jun 1636*:68C, fos. 122r-124v

- 14 Jun 1636:68C, fo. 111r

- 15 Jun 1636:68C, fos. 111r-v

- Jun 1636:68C, fos. 112r-121v

- 8 Nov 1636*:68C, fos. 105r-110v

- 28 Jan 1636/7*:68C, fos. 43r-49v, 51r-59r; R.19, fos. 381-2

- 8 Feb 1636/7:68C, fo. 59r

- 11 Feb 1636/7*: 68C, fos. 23r-36v

- 16 Feb 1636/7*: 68C, fos. 1r-11r, 14r-20v

- 20 Feb 1636/7: 68C, fo. 11r

- 24 Feb 1636/7: 68C, fos. 11r-12v

- 29 Apr 1637*: 68C, fos. 37r-41v

- 14 Oct 1637*:8/26; 8/27

- 18 Oct 1637: 8/26

- 30 Oct 1637: 8/26

- 31 Oct 1637*: 8/28; 7/20

- 7 Nov 1637: 7/20

- 10 Nov 1637: 7/20

- 15 Nov 1637: 7/20

- 18 Nov 1637*:8/29; 1/3

- 20 Nov 1637: 8/29

- 22 Nov 1637: 8/29

- 23 Nov 1637: 8/29

- 24 Nov 1637: 8/29

- 28 Nov 1637*: 8/30

- 2 Dec 1637: 8/30

- 6 Dec 1637: 8/30

- 27 Jan 1637/8*: 1/5, fos. 1-15

- 3 Feb 1637/8*: 1/5, fos. 23-35

- 10 Feb 1637/8: 1/5, fo. 36

- 12 Feb 1637/8*: 1/5, fos. 38-56, 59-69

- 13 Feb 1637/8: 1/5

- 14 Feb 1637/8: 1/5

- 20 Feb 1637/8: 1/5

- 21 Feb 1637/8: 1/5

- 22 Feb 1637/8: 1/5

- 1 Mar 1637/8: 1/5

- 13 Mar 1637/8: 1/5

- 16 Mar 1637/8: 1/5

- 10 Apr 1638: 1/5

- 19 Jun 1638: 7/38

- 20 Oct 1638*: R.19, fos. 434r-449v

- 22 Oct 1638:R.19, fo. 453r

- 30 Oct 1638:R.19, fo. 449v

- 6 Nov 1638*:R.19, fos. 454r-468v; R.19, fo. 469r-v

- 10 Nov 1638: R.19, fo. 470r

- 13 Nov 1638: R.19, fo. 470v

- 15 Nov 1638: R.19, fos. 470v-471v

- 20 Nov 1638*: R.19, fos. 400v-412v

- 24 Nov 1638:R.19, fos. 412v-413r

- 26 Nov 1638:R.19, fo. 413r

- 27 Nov 1638:R.19, fos. 413v-416v

- 28 Nov 1638*: R.19, fos. 422r-428r

- 30 Nov 1638: R.19, fo. 429v

- Nov 1638: 1/13

- 3 Dec 1638:R.19, fos. 429v-431v

- 5 Dec 1638*: R.19, fos. 474r-484v

- 12 Dec 1638: R.19, fos. 488r-490v

- 15 Dec 1638:R.19, fo. 490v

- 19 Dec 1638: R.19, fos. 490v-491r;R.19, fo. 491r

- 19 Jan 1638/9: R.19, fo. 491v

- 22 Jan 1638/9: R.19, fo. 491v

- 24 Jan 1638/9: R.19, fo. 492r

- 25 Jan 1638/9: R.19, fo. 492v

- 28 Jan 1638/9*: 1/9;68C, fos. 125r-v

- 9 Feb 1638/9*: 1/7, fos. 36-47

- 20 Feb 1638/9: 1/6, fos. 20-33

- 21 Feb 1638/9*: 1/6, fos. 20-33

- 23 Feb 1638/9*: 1/6, fos. 1-9

- 26 Feb 1638/9*: 1/6, fos. 20-33

- 2 Mar 1638/9: 1/6, fos. 9-12

- 9 Mar 1638/9: 1/6, fo. 12

- 18 Mar 1638/9: 1/6

- 19 Mar 1638/9: 1/6, fos. 12-17

- 2 Apr 1639: 1/6

- 4 Feb 1639/40*: 1/10;8/31

- 12 May 1640: 7/48

- 30 Jul 1640: 1/12

- 10 Oct 1640*: 1/11, fos. 73r-78v;1/11, fos. 56r-64v

- 14 Oct 1640:1/11, fo. 72r

- 22 Oct 1640:1/11, fo. 72v

- 24 Oct 1640*: 1/11, fos. 41r-44v;1/11, fos. 49r-52r

- 30 Oct 1640*: 1/11, fos. 13r-16v; 1/11, fos. 19r-30v

- 6 Nov 1640: 1/11, fos. 39v-40r

- 20 Nov 1640*: 1/11, fos. 5r-9r

- Oct-Nov 1640: 1/12

- 4 Dec 1640*:1/11, fos. 79r-87v; 1/11, fos. 1r-4v

- Unknown dates 1636-8: 68C, fos. 60r-61r, 70r-73v, 100v-101v, 102v, 124r-v

- No date: 1/13

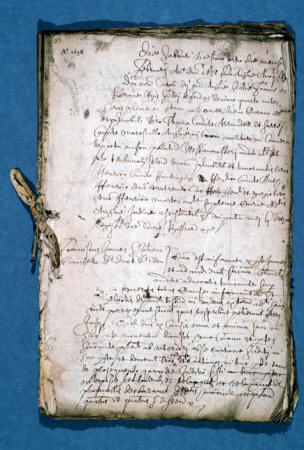

Book of Court of Chivalry proceedings for February 1638/9April 1639 (By permission of the Chapter of the College of Arms)