The Court of Chivalry 1634-1640.

This free content was Born digital. CC-NC-BY.

Richard Cust, Andrew Hopper, 'Introduction: the court in the 17th century', in The Court of Chivalry 1634-1640, ed. Richard Cust, Andrew Hopper , British History Online https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/no-series/court-of-chivalry/intro-court [accessed 30 April 2025].

Richard Cust, Andrew Hopper, 'Introduction: the court in the 17th century', in The Court of Chivalry 1634-1640. Edited by Richard Cust, Andrew Hopper , British History Online, accessed April 30, 2025, https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/no-series/court-of-chivalry/intro-court.

Richard Cust, Andrew Hopper. "Introduction: the court in the 17th century". The Court of Chivalry 1634-1640. Ed. Richard Cust, Andrew Hopper , British History Online. Web. 30 April 2025. https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/no-series/court-of-chivalry/intro-court.

In this section

The High Court of Chivalry in the early seventeenth century

Between 1634 and its temporary abolition by the Long Parliament in 1640 the Court of Chivalry was established on a regular basis for the first time in its history. Evidence survives for 738 of well over a thousand cases that the court processed during this period.

A new court?

Between 1 March 1633/4 and 4 December 1640 the High Court of Chivalry (or Earl Marshal's Court, as it was often termed by contemporaries) was established on a regular basis for the first time in its history. For an expanded version of this account, with a full scholarly apparatus of footnotes, see the 'Introduction', in R.P. Cust and A.J. Hopper (eds), Cases in the High Court of Chivalry, 1634-1640 (Harleian Society, new series vol.18, 2006). The court could trace its jurisdiction back to the mid fourteenth century when it was set up to deal with disputes arising from the display of arms or the conduct of war; however, it was not until the 1630s that it developed a set of routine procedures based on the civil law, and was open for business, with regular sittings in the same way as other Westminster courts. As Edward Hyde told the House of Commons in April 1640, 'this court, with these processes and proceedings, I am bold to say is very new.'

The surviving case papers and act books make it possible to trace details of 738 cases which were commenced in the court over this period. Sittings of the full court took place in the Painted Chamber in the Palace of Westminster (and during 1640 sometimes at Arundel House in the Strand) before the Earl Marshal, the Earl of Arundel, or his deputy and eldest son, Lord Maltravers, and senior members of the peerage. Because it was a civil law court it was not tied to the common law terms, and meetings took place on average once every ten days. In between there were smaller hearings before the Earl Marshal's professional surrogate, Sir Henry Marten LL.D. Once the court had been set up on a regular basis its volume of business increased rapidly. By 30 June 1634 it had ten cases in process; at the peak of its recorded activity in October-November 1638 it was handling more than seventy cases at a time; and during the autumn of 1640, after the Short Parliament had given notice of its intention to investigate its jurisdiction, it was still dealing with between twenty and thirty cases at each sitting. The amount of business it attracted during the 1630s, still fell well short of two of the other principal civil law courts, the Court of Arches and Admiralty; but it was evidently a popular forum for litigation, and its proceedings made a considerable impact on the public consciousness, as references in newsletters and the attention paid to it in the Long Parliament testify.

The basis for most of the actions brought before the court during the 1630s was defamation. It was also called on to adjudicate contested claims to gentility and coats of arms, together with heralds' claims to exact fees for gentlemen's funerals; but well over three quarters of all cases related to 'scandalous words provocative of a duel.' This was what Hyde identified as the really novel aspect of the court's proceedings in the 1630s, the claim it now made to fine, award damages and imprison in cases involving 'plea of words.' The court's critics in the Long Parliament saw this as a sinister extension of arbitrary government, threatening honest citizens with ruinous penalties for which there was no warrant in common law. Defenders of the court, on the other hand, justified such jurisdiction as urgently needed to curb duelling:

"if this cort should nott take conusans of words tendinge to the dishonor of a gentleman and a duell, where noe remedy is given by lawe then is a gentleman wounded in his honor, and is without repayre, which must needs introduce a worser inconvenience, that every man will endeavour to bee his owne judge and to right himself by duells and the like, whereby murder and the like may ensue".

As these arguments implied, the jurisdiction of the newly established court was rooted in the early Stuart monarchy's efforts to combat the growing menace of the private duel.

Two views of Arundel House on the Strand, where the Court of Chivalry sometimes convened.

James I's anti-duelling campaign

James I's anti-duelling campaign of 1613-14 was prompted by a series of high profile combats between leading courtiers in the late summer and autumn of 1613.In October the king issued a proclamation 'prohibiting the publishing of any reports and writings of duels'. This made it an offence, punishable in Star Chamber, to publicise any of the proceedings relating to the preliminaries to a duel, or the duel itself, and also offered the Court of Chivalry as a remedy to those who felt that their honour had been impugned.' This opened the way to a considerable extension of the court's jurisdiction. During the 1590s and 1600s it had met on an ad hocbasis to deal with a familiar range of disputes over claims to titles, displays of arms and precedence, as well as occasional misdemeanours by heralds and arms painters. Only rarely had it tackled cases relating to duelling. The effect of the 1613 proclamation was to set the court up as the principal arbiter of the quarrels and insults which caused duels in the first place.

The driving force behind this approach was Henry Howard, Earl of Northampton, the leading light among the Lords Commissioners who had exercised the office of Earl Marshal since the death of the Earl of Essex in February 1600/1. Northampton, and his in-house antiquarian, Sir Robert Cotton, had been gathering documentation and reviewing remedies for the problem since 1609, when Henry IV of France had highlighted the whole problem by issuing his own anti-duelling edict. During the weeks following James's October 1613 proclamation, Northampton worked on a more extensive scheme which eventually produced a second proclamation 'against private challenges and combats' of February 1613/14 and an accompanying Edict and severe Censure against Private Combats and Combatants, both issued in the name of the king.

The principle behind Northampton's approach was to try to tackle the root cause of duelling by providing the gentry with a remedy for insulting words 'the first word upon which a quarrel is begunne' following the practise in Spain where, so Northampton claimed, the readiness to punish 'ill language' had led to the virtual eradication of the practice. Under the terms of the royal Edict, insults were to be reported to the Court of Chivalry if the parties lived in the vicinity of London, or to the Lord Lieutenant and his deputies if they lived elsewhere. It was their responsibility to inflict immediate punishment on the offender and provide reparation for the injured party. Punishment was normally to take the form of a spell in prison, banishment from court, removal from the commission of the peace (if the offender was a J.P.) and deprivation of 'that usual and ordinarie liberties (which all gentlemen enjoy as their birth right) to weare swords and daggers.' Reparation would usually be by means of a public apology and submission, which would not only compensate the injured party, but also act as a deterrent to others. In devising these remedies, Northampton was explicitly acknowledging a view that had become firmly established within the gentleman's honour code, that if he allowed an insult to go unchallenged his reputation would suffer irreparable damage. What the Edict proposed was that the repair of such injuries should now be in the hands of a group of judges 'of noble birth, of honourable reputation, of sound judgement' who, acting in the king's name, would have the power 'to interprete and compound all questions of honour.' By offering the gentry an 'honour court' of unimpeachable authority it was hoped that they could be weaned off the temptation to duel. Once this system was in place, the February 1613/14 proclamation explained, it would no longer be possible to make the argument that a gentleman had no remedy other than the duel when he was insulted or given the lie.

Northampton's far reaching and imaginative scheme, however, quickly ran out of steam. His own death in June 1614, and the belief expressed by James in March 1616 that 'we have by the severitie of our Edict, put down and in good part mastered that audacious custome of duelles', deprived it of much of its impetus. The crown opted instead to put most of its effort behind the approach proposed in the 1613/14 proclamations which was to use Star Chamber to punish the act of issuing or sending a challenge to duel. As originally advocated by the new attorney general, Sir Francis Bacon, this was intended as a stop gap until the whole matter could be addressed in parliamentary legislation; but the failure of the 1614 Parliament ensured that it had to serve longer term, and for the remainder of James's reign most duelling cases were tried in Star Chamber. Northampton's proposals were not entirely neglected. In one of the more high profile Star Chamber cases, Darcy v Markham, Bacon himself, when giving sentence in November 1616, acknowledged that 'the matter of reparation of honour of the Lord Darcy' should be referred to the Court of Chivalry. But the court had to wait until the arrival of a new Earl Marshal before it began to take the initiative.

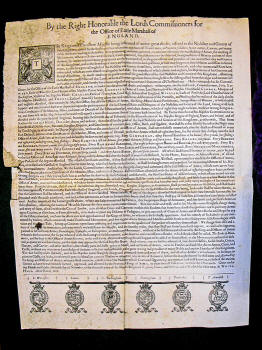

Order of the Lords Commissioners for the Earl Marshal, 1618

The Earl Marshal and the reform of the court

Thomas Howard, Earl of Arundel and Surrey, was appointed Earl Marshal on 29 August 1621 and set about reforming the court.One of the first challenges he faced was a denial of its authority by Ralph Brooke, York Herald, on the grounds that the Earl Marshal had no jurisdiction in the absence of a Lord High Constable. Brooke was attempting to overturn a ruling made by the Lord Chancellor in 1613 that his case (which involved suing his fellow heralds over fees) could not be removed to the Court of Chancery, but must be heard by the Court of Chivalry, and he openly declared that he would overthrow the authority of the Earl Marshal and his court. Arundel referred the matter to the king, and the king passed it on to the privy council, who came back in July 1622 with a declaration that during any vacancy in the office of Constable the Earl Marshal had authority to try cases in the Court of Chivalry on his own. This was confirmed in a privy seal letter from the king on 1 August, which also instructed Arundel 'to restore and settle the honourable proceedings of that court with addition of all the rights thereto belonging ; for which our pleasure is that you assiste yourself as much by antient records and precedents as you may.'

Over the following months the Earl Marshal sponsored extensive research in records covering the period up to the end of the sixteenth century, when there had last been an Earl Marshal. He established the basic procedures for hearing a case; secured a warrant from the attorney general to set a table of fees; and appointed Dr Arthur Duck as king's advocate to the court. This last move was particularly significant because Duck was one of the leading civil lawyers of the day, and his appointment signaled that from now on the court's procedures were to be based in Roman civil law. As G.D. Squibb has shown, this had been the case in the medieval period, but during the sixteenth century both civilians and common lawyers had practiced in the court. Now the primacy of civil law jurisdiction was re-established and common lawyers were excluded; but this did not happen overnight. During the first major hearing of the reformed court, the case of Leeke v Harris, there was still some debate over who should be allowed to act as counsel , and it was ordered that 'because civil lawyers were not of the councell in drawing up the bill, common lawyers might.'

Proceedings in the revived court commenced on 24 November 1623, with a full formal session in the Painted Chamber, set out according to the arrangements in the time of the last Earl Marshal, Essex, in 1598. Arundel and six leading peers sat on a raised platform under the king's arms, with the court register, heralds, counsel and officials arranged around a large table below them. This was to remain the normal layout for full sessions of the court. The hearings began a with a formal reading of the king's privy seal letter of 1 August 1622 confirming the Earl Marshal's jurisdiction, and then Arundel himself made a speech, 'importing the long discontinuance of the said office, and his honor's intent to revive that which had long bin in the dust.' He also explained that he had made careful search of precedents to ensure that he 'might not incroach upon other courts, as his lordship hoped other courts would not incroach upon his.' The court turned next to Leeke v Harris which concerned the issue of whether Harris had made a false claim to gentility in applying for his baronetcy in 1622; and , having established its right to try the case, it allowed Harris until the next sitting to deliver his answer and moved on to hearing Brooke's case. There were at least twenty three further sittings of the court until the verdict was delivered against Harris on 19 November 1624. These enabled it to refine its procedures, regularise its sittings and demonstrate to the public that it was open for business; however, having taken a considerable step towards establishing the court on a permanent basis, Arundel failed to follow up.

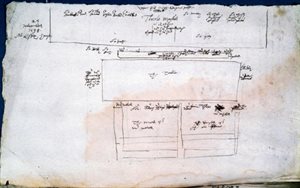

Seating plan for the High Court of Chivalry for the hearing of the dispute over the title of Lord Abergavenney before the Earl of Essex, Earl Marshal, in November 1598 (By permission of the Chapter of the College of Arms)

The court under Charles I

During the early years of Charles's reign the court operated under a much looser and more ad hocregime, much as it had done with the Lords Commissioners in James's reign.

Evidence for proceedings in this period is sparse, but what there is indicates that the hearings held by the Arundel tended to be small, informal affairs, conducted before himself or his deputy. Perhaps the most interesting aspect of these is that they do indicate that the Earl Marshal was now attracting a good deal of business via James's anti-duelling proclamations. In a 1625 complaint, Sir Samuel Argall referred to having been 'digracefully affronted' and given 'the lye, which uncivill behaviour wasin breach and contempt of his Majesties' proclamacon and ordinances.' There was evidently a growing recognition that the Court of Chivalry was prepared to tackle 'plea of words' and willing to provide reparation for gentlemen who had been slandered or defamed. In cases where the offender was a plebeian, Arundel generally sentenced them to a spell in the Marshalsea; where other gentlemen were involved he usually tried to have the matter settled by local arbiters.

Even while it was operating at this relatively low level of activity, however, the court did not escape controversy. Throughout Charles's reign it was subjected to regular sniping and harassment by common lawyers eager to limit its jurisdiction and jealous of the exclusive rights to practice enjoyed by civil lawyers. As Brian Levack has demonstrated, this was part of an ongoing struggle dating back to James's reign in which predatory common lawyers, like Sir Edward Coke, took every opportunity to undermine the civilians and assert the primacy of their branch of law. These tensions came to a head in late 1630-early 1631 over the case of Tompson v Jones, in which Mr Jones, a London churchwarden, had been imprisoned in the Marshalsea at the behest of Thomas Tompson, pursuivant to the heralds. Jones obtained a Habeas Corpus from King's Bench to secure his release, but was then promptly rearrested by the Earl Marshal. The case caused considerable debate amongst the crown's law officers, but eventually they sided with the Earl Marshal, and the claims of his court were upheld.

This offered a considerable boost to the self-assurance of the civil lawyers, and the arguments used in this case to support their jurisdiction give a good indication of the basis on which they were able to make increasingly confident assertions about the rights of their branch of law. Referring to its direct remit from the king to try cases of honour, they insisted that it 'was ever held as a jurisdiction beyond [King's Bench] and of an higher nature and reformation as made by a higher power.' Against the common law assumption of superiority, because it alone had existed since time immemorial, it was argued that 'the law of the court marshall was as ancient and as much lex terraeas any other practised in the kingdom.' And on the vexed issue of prohibitions - which were issued to remove proceedings from civil law courts such as Arches and Admiralty so that they could be tried at common law it was claimed that 'there can be no appeal from the Court Marshall to the King's Bench, for statute hath settled it otherwise.' For good measure the court's supporters referred back to the privy council pronouncement and privy seal letter of July-August 1622 and pointed out that a challenge to its jurisdiction now would represent 'the overthrow of the legall power of the counsell board in this point.'

The outcome of Tompson v Jones undoubtedly helped to bolster the confidence of the Court of Chivalry and its practitioners; but, as William Noy, one of the legal officers called in to advise on the case, warned, its position remained fraught with controversy : 'many will take occasion to talke of the lawfulness of it in this tyme wherein men are ready to dispute of all things.'

Reay v Ramsey

The Court of Chivalry case which attracted most public attention during the 1630s was Reay v Ramsey. This had little to do with the types of business dealt with after 1634; but it again confirmed the readiness of the crown and legal establishment to uphold the court's proceedings. Lord Reay brought a charge of treason against David Ramsey, a groom of the bedchamber, for plotting to use force against the crown whilst acting as lieutenant to the Marquis of Hamilton in Sweden; and, because this rested solely on Reay's word, both sides appealed to the ancient custom of trial by combat to test its veracity. Charles was keen to proceed and in August 1631 consulted the judges. They gave the opinion that trial by combat was justified as an appeal of treason, but that it would have to be authorised by the Court of Chivalry, with the High Constable sitting alongside the Earl Marshal. In November, therefore, Charles appointed the Earl of Lindsey Constable for the duration of the case and proceedings commenced before Lindsey, Arundel and an array of senior peers on the 28th. Arundel hoped to obviate the need for a combat by establishing the validity of the charge in court; but this proved to be impossible, and so, in early February 1631/2, the court ordered that it go ahead, on 12 April at Tothill Fields in Westminster. The whole event aroused enormous public interest and opinion was divided over whether such proceedings were valid. The newsletter writer John Pory reported in late January that

the judges and common lawyers say, in case a combat bee awarded, whosoever killes the other is by their law guilty of murder. And I have heard bishops and divines say it is a heathenish [act] to seek truth that waye, and that all duels and combats whatsoever are condemned by generall councills.

Perhaps because of these objections, Charles eventually decided to call off the combat; however, his willingness to sanction it in the first place, and the evidence this provided of his interest in, and approval of, the court's proceedings, were another boost for the self confidence of its practitioners.

The civil lawyers

This set the context for regularising the meetings of the court in 1634. The decision to go ahead with this was not one which was clearly defined, or traceable to any specific royal instruction, equivalent to James's command to 'restore and settle' the court in 1622. Rather it was something which developed out of a series of opportunities which civil lawyers were able to seize upon and exploit.

For much of the early seventeenth century the civil law was a profession in decline. Attacks on its jurisdiction by common lawyers, and the aggressive use of prohibitions, had begun to produce a shortage of jobs which, as Brian Levack has demonstrated, fed through into a decline in the numbers of Doctors of Civil Law graduating from the universities and a fall in the membership of Doctors' Commons, the professional body representing those who practiced in London. James professed concern over the trend, but did little to try to reverse it. Charles, however, saw the civil lawyers as natural allies of the crown and the Laudian clergy, and inaugurated a series of measures to help them. As early as December 1625 he ordered Archbishop Abbott to work with the privy council to ensure that senior diocesan positions were reserved for Doctors of Civil Law. In February 1633 the privy council addressed the damage done to Admiralty court jurisdiction by prohibitions and directed that in future these were not to be issued against cases which concerned matters taking place abroad or on the high seas. Finally, in December 1633, Charles met with his councillors to discuss measures 'for the breeding up of able and sufficient professors of the Civil and Canon Laws' and to 'incite a sufficient number of men of eminent parts and abilities to apply their industry to the said studies and professions.' They came up with the solution of ensuring that henceforth all vacant masterships of the Court of Requests, and eight out of the eleven masterships of Chancery, should be reserved for civilians. These measures would take time to have an effect; but meanwhile they helped to create a climate of opinion which was markedly receptive to initiatives to improve the lot of civil lawyers. It may well have been around this time that Arundel as he later recalled for the benefit of Edward Hyde received advice from 'Sir Henry Martin and other civilians who were held men of great learning' that the trial of cases for 'plea of words' in the Court of Chivalry was 'just and lawful.'

In these circumstances the civilians were well placed to make the most of the opportunity offered by another high profile case, Hooker v Holmes. This arose out of a murder committed during a duel which had taken place overseas, in Newfoundland, and which therefore fell under purview of the Court of Chivalry. Because it was a capital offence it again required the attendance of the High Constable, and once more Lindsey was temporarily appointed to the position. Hearings commenced on 26 February 1633/4 and continued through March and April until, on 26 April, Holmes was sentenced to hang and then, subsequently, pardoned. On this occasion, however, the opportunity provided by the revival of formal sittings of the court was not allowed to slip away and other plaintiffs started to bring cases, no doubt encouraged by Marten and Duck who were managing Hooker v Holmes. At the session on 1 March, which Hyde identified as the first for which records of the 'new' court survived, another action was added in which Abraham Bowne complained that Henry Throckmorton had accused him of being 'cowardly, petty minded and a liar', and challenged him to duel. Dr Duck, acting as counsel to Bowne, argued that these words were 'punishable to prevent the effusion of blood' and the judges agreed, fining Throckmorton £6 13s. 4d. (with £10 costs) on 24 May 1634. This appears to have been the first instance of a case in a full court hearing being determined on the basis of 'scandalous words likely to provoke a duel.' Others soon followed. By 26 April the court was hearing Turney v Woodden, and on 30 June 1634 Woodden was found guilty and sentenced to pay £10 damages (with £5 costs) for having 'used and given unto Robert Turney divers ignominious and disgracefull words, and amongst others to have given him the lye.' During May several other plaintiffs weighed in with actions, including Dr Thomas Temple, himself a civil lawyer, who complained against Bray Ayleworth for giving him the lie and assaulting him in July 1633. By 30 June 1634 ten cases were in progress. What appears to have happened is that once word spread that the court was open for business this rapidly generated suits and the court's proceedings developed their own momentum, fed by the gentry's desire for cheap and rapid redress in cases involving defamation, and by the civilians' appetite for fees.

Between March 1634 and April 1640 the court was able to establish itself as regular component of the hierarchy of central law courts at Westminster, largely unimpeded by challenges to its jurisdiction. A memorandum of 'Certeyn reasons that the professors of the common lawes ought not to be excluded from practisinge in cases of honor' appears to have been largely inspired by the common lawyers' desire to gain a share of the lucrative fees; but it did rehearse familiar arguments about the inferiority of the civil law as 'a meere stranger' to 'the lawes and customes of this realme.' A more direct challenge to the court's jurisdiction came in a case from May 1636 in which William Say, a Middle Temple barrister, and later parliamentarian and regicide, was prosecuted for 'publishing both by word and writing that my Lord Marshall's decrees and constitutions were contrary to lawe.' When approached by Thomas Thompson with an order for his client to pay heralds' fees he had retorted that these were illegal and the court's constitution 'was of no validitie.' He maintained this position when summoned before Sir Henry Marten and was fined and imprisoned. Others who challenged the court on the issue received similarly short shrift. These were indications that throughout the late 1630s the court's practitioners felt confident of their ability to uphold and defend their jurisdiction.

They were no doubt considerably encouraged by an important privy council ruling of February 1637/8 which supported their right to act on 'plea of words'. In the case of Sherard v Mynne the council stipulated that, although the defendant had already been heavily fined in Star Chamber, because the bill was 'for words spoken by Sir Henry Mynne of the Lord Sherard, tendinge to his disgrace', it was also 'to be heard & censured in the earl marshall's courte', which duly happened. Arundel himself also displayed considerable assertiveness in heading off efforts to obstruct proceedings from the court. In Powis v Vaughan the defence counsel pleaded that under the 1624 Statute of Limitations there was no case to answer because the alleged scandalous words had been uttered many years earlier. The Earl Marshal referred the matter to the Lord Privy Seal, the Earl of Manchester, two of the lord chief justices and Sir Henry Marten. Manchester and the judges, who were all common lawyers, gave their opinion that under the terms of the statute the court could not take notice of words uttered more than twelve months previously, and even Marten argued that under civil law an action had to be brought within two years. Arundel, however, accepted the plea of Powis's counsel that the Court of Chivalry had 'never been strickly tyed in matters of honor, either to the common or the civill lawe, but arbitrary', and ordered that the case should proceed. Edward Rossingham's report of these proceedings along with others in March 1638/9 which involved heavy fines for relatively trivial offences indicated that there was some public disquiet over the court's actions. But prior to the summoning of the Short Parliament there appears to have been no come back.

Dr Arthur Duck, King's Advocate in the Court of Chivalry was mercilessly satirised in 1641 as the epitome of the corrupt Laudian civil lawyer(By permission of the British Library)

The litigants

Once the court was established on a regular basis in 1634 the volume of business multiplied rapidly. By 1637/8, when cases were running at over seventy per sitting, there were signs that the amount of work was becoming too much for the court to cope with. Plaintiffs were having to queue up to be assigned court days, witnesses were kept waiting in London for weeks on end and Dr Duck was pleading pressure of business as a reason for delaying hearings. The civil lawyers enjoyed a bonanza in terms of new business. There is, however, no indication of potential litigants being put off, and even after adverse publicity in the Short Parliament large numbers of new actions were still being started. Knowledge of the court's existence and procedures spread far and wide. The counties where cases originated were spread relatively evenly across England and Wales. London and Middlesex were well out in front, as one might expect given the advantage of geographical proximity, but the other leading providers of plaintiffs were the more far-flung counties of Devon, Cornwall and Yorkshire. Distance and difficulty of communication do not appear to have been any hindrance to the court's activities. Up and down the country potential litigants knew of its existence and understood the forms of redress that it could offer. Knowledge of the rules of the game was not confined to the gentry. When Thomas Cooke, a mercer, was beaten up by Nicholas Wadham and his servant in a tavern in Liskeard, Cornwall, he very self consciously refrained from retaliation, saying to Wadham 'I knowe you are a gentleman, therefore I will not replie, because you shall not take advantage against me in my Lord Marshall's court.' Some litigants appear to have acquired a considerable appetite for suits in the court. Ralph Pudsey, a quarrelsome North Riding attorney, brought four, as well as acting as legal adviser or commissioner in at least three other cases.

One of the reasons for the court's appeal was the high probability that plaintiffs would secure a favourable verdict. This is evident from those cases where we have a record of the final sentence. Of the 126 cases where the outcome is known 94 (73.8%) resulted in conviction, 19 (15%) were settled by arbitration and only 14 (11.1%) resulted in acquittal. For the most part comparable data does not exist for other courts of the period; so it is to hard to know how conviction rates compare with these. But a situation where virtually three quarters of all cases were won by the plaintiff does indicate a set of procedures heavily stacked in his favour. This is confirmed by the detailed record. In practice, if a case ran to its full term it was extremely difficult for a defendant to secure an acquittal, particularly where he was a plebeian. It tended to happen only when a plaintiff failed to pursue a case, or was unable to produce witnesses to support his libel, or where local officers were attempting to carry out their duties in the face of extreme provocation by a gentleman. The case of Filioll v Haskett demonstrates the level of abuse required for a gentleman to lose a case. Here Haskett secured acquittal only after an array of witnesses, including the local tythingman, testified that he was a respectable yeoman, who had been subjected to a sadistic beating by Fillioll and his servant, about which they boasted openly afterwards. Almost uniqely Fillioll was required to answer to the court for false clamour and molestation of Haskett. The norm was for gentlemen to be able to subject plebeians to vicious assaults at the slightest hint of disrespect and still secure convictions. The extent to which the odds favoured the plaintiff is also reflected in the frequency with which defendants promoted counter suits where they were qualified to do so. Sometimes the court would decide between them and award the case to one party or the other; but there were also examples where it maintained its even handedness by awarding sentence to the plaintiff in both actions, notably in Pincombe v Prust, where two ageing Devon lawyers traded insults and insisted on pursuing their actions to the bitter end, in spite of efforts at arbitration.

The considerable advantage enjoyed by the plaintiff in the Court of Chivalry was one of the things which made it attractive to litigants. There were others. Levack makes the point that there was a need within the legal system for civil law courts which could decide cases relatively quickly, based on summary process and written testimony, rather than having to rely on the cumbersome trial by jury. This was what made the Admiralty Court popular with its litigants, who were by and large merchants and traders needing quick decisions so that they could get back to business. Several of these considerations also applied to the Court of Chivalry. It offered a new form of relatively cheap and speedy redress before judges whose authority was unimpeachable. For a gentleman who had been insulted in a manner likely to provoke a duel the principal avenue for litigation prior to the 1630s was the Court of Star Chamber. But Star Chamber process was notoriously slow and expensive. T.G. Barnes has calculated that most cases took years to reach a resolution with the preliminary proceedings lasting anything for eight to twenty one months, and then a further three months to two years before there was a final verdict. The average Court of Chivalry case, on the other hand, took just over a year from start to finish. The cost of Star Chamber suits is harder to calculate, but it appears that most plaintiffs could expect to pay several hundred pounds, whereas the mean costs in a Court of Chivalry case were £43, a sum which most plaintiffs could expect to recoup with a favourable verdict. Overall the experience of litigation in the Court of Chivalry compared favourably with the Court of Requests which was renowned for providing prompt and reasonably priced justice.

There is also every indication that the procedures and outcomes offered by the Court of Chivalry were well suited to the requirements of litigants. For most what probably mattered more than any financial benefit was the confirmation of their status and reputation, and the humiliation of their opponents. The former was provided by the terms of the submissions required by the court and also by the trial process itself. Because only gentlemen were permitted to bring a prosecution, the grant of process provided valuable affirmation of gentility. Corroboration for those whose status might otherwise be questioned was also provided by the taking of depositions in front of local worthies appointed by the court. These hearings frequently constituted mini courts of honour in their own right. Plaintiffs would line up local witnesses, regularly drawn from the gentry and knightly classes, who would attest their standing and worth within the local community. This was done partly in order to emphasise the grossness of the insult perpetrated against them, but also to provide a semi-public reparation for their slighted honour and warn off others from attempting the same thing in the future. And, of course, the effect of these hearings was reinforced by the submission. Performed publicly, often before an invited audience, this was an event which was both immensely gratifying for the plaintiff and deeply degrading for the defendant. George Searle, former mayor and future M.P. for Taunton, had to make his submission in September 1639 at the Mayor's Feast before those who had witnessed his original insult to Robert Browne, the son of a Dorset knight. The experience was still painful in January 1640/1 when he petitioned the Long Parliament for redress for this 'unworthie submission'. In other cases defendants took matters into their own hands and sought to subvert the whole process. The most striking instance of this was Abraham Comyns' submission to George Badcock in the church at Great Bentley, Essex, in which he kept his hat on, denied Badcock the honorific 'Mr' and altered the wording, in 'a jeering and fleering manner', then crowned his performance at evening prayers by making a low, mocking bow to Mr Badcock which the congregation found hilarious. Comyns found himself forced to make a second submission, this time under the eagle eye of the judges at Chelmsford assizes. Submission was evidently a painful process; but, then, as far as the plaintiff was concerned, that was the whole point. All the indications are that the Court of Chivalry was meeting a widely felt need and plugging an obvious gap in the market for litigation.

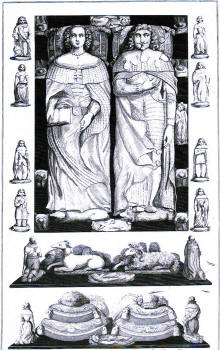

William Lord Sherard (d.1640) and his wife Abigail, from their funeral monument in Stapleford church, Leicestershire in J.Nichols, The History and Antiquities of the County of Leicester, 4 vols (1795-1815). Sherard was the plaintiff in the important case against Sir Henry Mynne, case 593.

The collapse of the court

The fortunes of the Court of Chivalry changed dramatically with the meeting of the Long Parliament in November 1640.On the 23rd the house of commons established a committee to receive petitions relating to its proceedings, and 4 December was the last time the court met in full session. Edward Hyde was able to remark somewhat smugly that 'the very entrance upon this inquisition put an end to that upstart court.' This raises the question of whether its rapid demise was the true reflection of its popularity and effectiveness during the 1630s. Put another way, did the Court of Chivalry it collapse because of a groundswell of opposition to its actions and procedures; or was it a victim of changed political circumstance, ground between the juggernaut of a reforming Long Parliament and the self-interest of common lawyers?

The criticisms of the court made by Hyde and his colleagues in parliament can be summarised under two main headings : firstly, that it was an innovation of the 1630s, 'sett upp when there was noe more hope of parliaments', designed to serve the interests of an increasingly arbitrary regime and ambitious, self-seeking, civil lawyers; and secondly, that once established it took powers to fine and imprison on 'plea of words' which represented all that was tyrannical and unjust about the 'imperial law' practiced by the civilians. The first charge, as we have seen, was only partially justified. The rationale and basis for the newly established court had been set out in James's duelling edict and proclamations, and the initial steps towards its creation had been taken in the late 1610s and early 1620s. Moreover, responsibility for the form it took during the 1630s belonged at least as much to the Earl Marshal as to the civilians, even though, for political reasons, both Hyde and Sir Simonds D'Ewes were eager to deflect blame from the former. The second set of charges, however, had more substance.

One of the features of civil law jurisdiction, in comparison with the common law, was the heavy onus it placed on the impartiality of the judge who assumed the roles of prosecution, judge and jury. As Levack has pointed out it was the failure of civil law judges to meet the exacting standards of fairness demanded of them which lends most credence to complaints of arbitrariness in the civil law courts; and the Court of Chivalry was no exception. Lord Maltravers, the Earl Marshal's deputy and eldest son, who presided over the majority of full sittings after his appointment in April 1636, was certainly guilty of some of the high-handedness and neglect of the due process of law with with which both Hyde and D'Ewes charged him. One accusation born out in the surviving cases was that under his direction the court ramped up the size of fines and damages from a norm of around £20-£40 to in excess of £100, and sometimes as high as £500. The trend appears to have been set in late 1636 in the high-profile case of De La Ware v West, in which George West was fined £500 for seeking to impersonate a member of the nobility. The following March Christopher Copley was again fined £500 for insulting the Earl of Kingston and claiming to be his equal. Thereafter the norm for cases involving members of the peerage was fines or damages in the order of £200-£500, and for members of the knightly class often around £100-£200. Although these sentences fell short of the thousands of pounds being awarded in Star Chamber during the 1630s, they still represented strikingly hefty punishments for a court whose main sanctions traditionally had been to force a public submission, or degrade a man from his honorific status.

A second charge associated with Maltravers' regime which is harder to substantiate is that defendants were often bound over or imprisoned without proper trial. By their very nature such cases left little record in the trial proceedings; however, such evidence as there is does demonstrate that this was happening. D'Ewes' example of Rivers v Bowton, where Bowton was allegedly arrested by a court messenger and imprisoned until he had given a bond of £100 to appear in the court on two days warning, was certainly not unique. Alongside this there is also evidence of proceedings being heavily stacked against the defendant. The case of Warner v Lynch and Snelling cited by Hyde, amply supports such a claim. When Warner petitioned Maltravers to complain that he had been jostled and insulted on the highway by two local clothiers, the deputy Earl Marshal deputy immediately wrote to two Suffolk justices, Sir Thomas Glemham and Edward Poley telling them that this was an abuse of 'so high a nature as deserves severe and exemplary punishment.' The justices, after a somewhat cursory investigation of the facts, duly reported back that 'the foulnes of the abuse [was] such a one as in theese parts we have not knowne', and the clothiers were convicted and sentenced to the unusually heavy penalty of a £200 fine and 200 marks damages. This case exemplified the difficulties inherent in the multiple roles of civil law judges, and there was scope for a further conflict of interests when the court was used to back up the actions of patentees, after the king had referred a complaint of opposition by Sir Popham Southcott, the soap monopolist, to its jurisdiction in February 1638/9.

The criticisms of the court made by Hyde, D'Ewes and others need to be balanced against considerable evidence indicating that it was popular amongst litigants. None the less, there is evidence of bias and arbitrariness in its proceedings, especially under the direction of Lord Maltravers.

Henry Frederick Howard, Lord Maltravers, Deputy to the Earl Marshal, 1636-1640

Charles I's anti-duelling campaign

Duelling was never an issue which appeared as pressing to Charles as it had done to his father, largely because there was no repeat of the clusters of deaths of leading courtiers which occurred in 1609 and 1613.

But for a monarch who prided himself on an orderly and harmonious regime, the existence of duelling, particularly in the precincts of the royal court, was a cause for concern, and there were moments in his reign when the problem did threaten to get out of hand. One of these was the spring and summer of 1634 when news of a series of challenges between leading courtiers was reported by letter writers and Charles himself had to intervene to prevent a combat between Henry Percy and Lord Denluce. However, the incident which, perhaps, had most impact from the point of view of the Court of Chivalry was a quarrel of April 1633 in which the Earl of Holland challenged Jerome Weston, son of the Lord Treasurer, to duel in the king's garden after Weston had opened his correspondence. Lord Fielding and the son of Lord Goring joined in, and Henry Jermyn, another leading courtier, was implicated in sending the challenge. Charles was livid. He gave all those involved a dressing down in front of the privy council, declared his resolution 'herafter to prosecute all delinquents in this kind' and drafted the submissions of the offending parties in person. Further action had to be deferred because of his summer progress to Scotland; but the issue had been pushed up the crown's agenda and this no doubt helped to encourage Arundel and the civil lawyers when it came to pressing ahead with their claims to jurisdiction over scandalous words early in 1634.

But how effective was the court in fulfilling this function of curbing the practice of duelling? This is hard to answer because of the difficulty of making any sort of estimate of the amount of duelling that was taking place in early Stuart England. Historians have tended to rely on stray references in newsletters; however, it is clear from other sources that these are heavily biased towards combats involving courtiers and leading noblemen. Star Chamber and Court of Chivalry cases offer a better guide to the extent of the problem in the localities, but again it is apparent that the combats referred to the courts were only a small fraction of the total. Given these limitations, however, it is still possible to assess some of the ways in which the Court of Chivalry did have an impact on the problem.

Numerous litigants appealed to the court after receiving a challenge, often specifically citing James edict and proclamations. In such cases the Earl Marshal's usual response was to send a messenger to detain the parties involved and then bind them over to good behaviour for substantial sums in the order of £500- £1000. This put an immediate stop to some duelling mainly around the fringes of the royal court or at the Inns of Court, which were two of the main trouble spots but it is doubtful whether it had much impact as a longer term deterrent. Bonds of £500 apiece did not stop Guy Moulsworth and William Gartfoote from continuing to taunt and provoke the two fellow Inns of Court students who had appealed against them to the Earl Marshal; and Robert Walsh, one of the habitual duellists who crop up in the court's records, mocked and challenged Edward Gibbes, the son of a Warwickshire gentleman, in Westminster Hall in May 1639, in spite of having been bound over for 1000 marks the previous year to stop a duel over a horseracing bet. Where the court played a much more effective role was in providing disputants with an alternative means of settling their differences.

There are numerous instances where gentlemen were able to sidestep challenges, or draw aside from quarrels likely to lead to a challenge, because they were confident that the court would vindicate their honour. In February 1639/40 William, Viscount Monson caught Robert Welch cheating at cards, and when he tried to cover up by giving him the lie and challenging him to fight, Monson felt able to hold back and the next day launch a Court of Chivalry suit. In such cases there was often a risk of being branded a coward for refusing to fight; but plaintiffs calculated that the benefits of being vindicated by the king's representative, the Earl Marshal, and of inflicting a humiliating submission on their opponents outweighed this. In some cases wily disputants can be seen leading on opponents to the point at which they would provide a prima facie case for the prosecution.

There was more than an element of this in the Monson case where the viscount baited Welch to the point at which he lost all self-control and, in front of witnesses, tried to force a fight. In Billiard v Robinson, two Northamptonshire gentlemen quarrelling in a Peterborough tavern appear to have known exactly what was at stake as each tried to manoeuvre the other into issuing a challenge. Billiard eventually came out on top, in spite of being the first to draw his sword. He was able to report to the court his sanctimonious response to challenge that Robinson was eventually provoked into making :

I will not meete you in the bushy close, but I will meet you in Star Chamber, or some other Court of Justice, where the lawe shall right mee, and I will not right myselfe.

This was precisely the sort of conduct that the scheme originally devised by James and the Earl of Northampton was designed to elicit; and, to the extent that gentleman could feel that litigation was an acceptable substitute for violence when it came to vindicating their honour, that scheme can be said to have been a success. The regularisation of Court of Chivalry procedures did not eradicate duelling, as James rather fancifully supposed it might. But it did play a part in containing the problem, and ensuring that England never had to face the wholesale slaughter of young noblemen which occurred in early seventeenth century France.

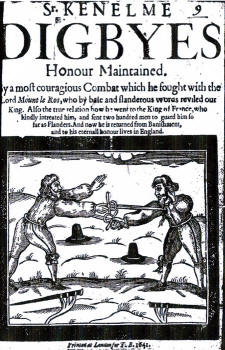

In spite of the crown's efforts to curb the practice, gentlemen continued to boast of their prowess in duelling :Sir Kenelme Digbyes Honour Maintained (1641) (By permission of the British Library)

Bibliography

For an up to date account of the political background:

- R.P. Cust, Charles I. A Political Life (Harlow, 2005)

On the High Court of Chivalry:

- G.D. Squibb, The High Court of Chivalry (Oxford, 1959)

- P.H Hardacre, 'The Earl Marshal, the Heralds and the House of Commons, 1604-1641', International Review of History, 2 (1957)

- M.H. Keen, Origins of the English Gentleman (Stroud, 2002), chp. 2

- R.P. Cust and A.J. Hopper (eds), Cases in the High Court of Chivalry 1634-1640 (Harleian Society, new series, 18, 2006)

- G.D. Squibb, Reports of Heraldic Cases in the Court of Chivalry 1623-1732 (Harleian Society, 107, 1956)

- F.W. Steer (ed), A Catalogue of the Earl Marshal's Papers at Arundel Castle (Harleian Society, 115-16, 1963-4).

On the legal background:

- B.P. Levack, The Civil Lawyers in England 1603-1641. A Political Study (Oxford, 1973).

- T.G. Barnes,'Star chamber litigants and their counsel, 1596-1641', in J.H. Baker (ed), Legal Records and the Historian (London, 1978)

- W.J. Jones, The Elizabethan Court of Chancery (Oxford, 1967)

- T. Stretton, Women Waging Law in Elizabethan England (Cambridge, 1998)

On duelling:

- M. Peltonen, The Duel in Early Modern England (Cambridge, 2003)

- A. Stewart,'Purging Troubled Humours : Bacon, Northampton and the anti duelling campaign of 1613-1614' in S. Clucas and R. Davies (eds), The Crisis of 1614 and the Addled Parliament (Aldershot, 2003)

- R.P. Cust and A.J. Hopper, 'Violence and gentry honour in early Stuart England ; the Court of Chivalry and duelling', in S. Carroll (ed), Cultures of Violence (Basingstoke, 2007)