The English Fur Trade in the Later Middle Ages. Originally published by London Record Society, London, 2003.

This free content was digitised by double rekeying. All rights reserved.

Elspeth M. Veale, 'III. The Emergence of the London Skinners', in The English Fur Trade in the Later Middle Ages(London, 2003), British History Online https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/london-record-soc/vol38/pp36-56 [accessed 10 May 2025].

Elspeth M. Veale, 'III. The Emergence of the London Skinners', in The English Fur Trade in the Later Middle Ages(London, 2003), British History Online, accessed May 10, 2025, https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/london-record-soc/vol38/pp36-56.

Elspeth M. Veale. "III. The Emergence of the London Skinners". The English Fur Trade in the Later Middle Ages. (London, 2003), British History Online. Web. 10 May 2025. https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/london-record-soc/vol38/pp36-56.

III THE EMERGENCE OF THE LONDON SKINNERS

During the Middle Ages the working of skins of all sorts, by whatever name the craftsmen were known and whatever processes they were carrying out, was a familiar sight. The sutor was one of the most important men in Anglo-Saxon England. Abbot Aelfric wrote in the tenth century of the shoes, hose, gear for horses, bottles, flasks, pouches, and clothing which the sutor made out of skins, and suggested that no one would care to face the winter without his assistance. (fn. 1) Wherever a group of people lived together someone dressed skins and made clothes, saddles, and shoes from them. In most villages there would have been a peasant with a bent in that particular direction working for his friends and neighbours. By the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, small market towns were the centres for the surrounding countryside and there the craftsmen congregated, and specialists either prepared skins, or cobbled shoes, or made saddles.

We do not know when it became customary for a separate group of craftsmen to specialize in dressing and making up fur skins. Of those working on leather skins, that is skins from which the hair had been removed, a considerable division of labour had developed in certain areas by the twelfth century, when documentary evidence becomes available. The tanners prepared skins, and among the tanners themselves there was often later a differentiation between the barker, who used the bark of oak trees, and the whittawyer, who used alum. Groups of saddlers, cordwainers or shoemakers, glovers, and tanners were then to be found in centres like London, Oxford, York, and Exeter, and at least by the thirteenth century in newly founded small market towns like Stratford-on-Avon. (fn. 2) The shoemakers of Oxford were numerous and strong enough to be organized in a gild in 1129, according to the only surviving Pipe Roll of the reign of Henry I, and presumably the emergence of such specialist craftsmen long antedates the written evidence. (fn. 3) References to craftsmen described as pelliparii, peleters, or skinners, men who were both dressing fur skins and making them up, are relatively few until the closing years of the twelfth century, the two earliest being found in Lincolnshire charters of the reign of Henry II. (fn. 4) But the fact that the word 'skinner' is of Scandinavian origin suggests that the craft may have made an early appearance in England in important centres in the Danelaw like York, Lincoln, and Norwich. (fn. 5)

Clearly, however, the more skilled and costly work on furs always occupied fewer craftsmen than did the manufacture of leather goods. Even in the larger provincial centres specialized skinners were few, and they remained on the whole small groups of workers seldom strong enough to organize or protect themselves. (fn. 6) In Colchester in 1301 there were only four skinners among its taxed population of four hundred, whereas there were fifteen cordwainers. (fn. 7) Later, when Poll Tax returns permit a wider investigation into the inhabitants of some of the bigger provincial cities, the numbers still remain small. Oxford in 1380 had twenty skinners among its citizens; (fn. 8) York in the following year also had twenty skinners, but forty-four cordwainers. (fn. 9) Many were no doubt like those in Beverley in 1359 who, with the tailors, paid ¼d. a week for a 'window' in which they worked in full gaze of their customers. (fn. 10) Frequently the skinner carried no stock of materials and, as we have seen, he needed little equipment; his customers would purchase the raw skins they required and then bring them to him to be dressed and made up. The more prosperous skinners, however, themselves bought raw skins, dressed them, made them up, and sold them in their shops. In many towns they congregated together, as in Lincoln, where there was a Skinners' Row. (fn. 11) They were craftsmen whose interests rarely extended beyond customers who lived near by, and whose demands for warm and practical garments they satisfied from materials which lay at hand. All too often they elude our grasp completely.

Yet a few hints survive to suggest that in certain provincial towns the fur trade was a flourishing one. In Northampton, for instance, skinners seem to have been particularly prosperous in the thirteenth century. Northampton, well placed strategically, was in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries the most important town in the Midlands, (fn. 12) the centre to which barons and prelates were summoned to meet their sovereign, to which the Exchequer was at one time removed from London, and to which university students fled after disputes in Oxford. (fn. 13) Kings frequently kept court at Northampton Castle and the busy town was often thronged with visitors. Its fair was regularly visited by royal agents and European merchants, and some 300 men are said to have earned their living in its textile industry. (fn. 14) Certainly the scale on which some Northampton skinners were trading is remarkable. As early as 1210 one Johannis Pelliparius was described as mercator, (fn. 15) and by 1250 the size of some of their businesses is revealed by the extent of their sales of furs to the King. Benedict Dod and another Northampton merchant sold furs worth £81. 13s. 6d. in 1250, and were paid a further £68. 6s. 8d. in 1254. (fn. 16) The sum of £190. 14s. 2d. paid to Northampton merchants, nearly all for furs bought during the years 1246–9, suggests that they were at least worthy to be compared with the great Lincoln cloth merchants, who were paid over £505 during the same years. (fn. 17) As they had sold their furs at fairs in Winchester, St. Ives, Stamford, Boston, and Bury St. Edmunds, as well as in Northampton, it is evident that the men responsible were busy merchants whose interests took them far from their Northampton shops.

It was London, however, which was to become the great centre for the manufacture of furs in the later Middle Ages. Sheltered by ancient walls and the river, the square mile of the City of today had already taken shape. (fn. 18) In about 110 parishes there were living early in the thirteenth century probably something in the region of 20,000 people. Several of the wards of the City included small settlements outside the main gates. Beyond lay more open suburbs, green with trees and watered by streams and wells, with forests still crowning the hills to the north. Inside the walls spacious gardens, monasteries, town houses of the magnates, and shops and warehouses of the merchants stood cheek by jowl with the mean alleys and cramped and miserable tenements of the poor. But above all the City was a thriving business community, with busy wharves and a river thronged with shipping. Merchants from all over Europe bustled about the narrow streets, joining the traffic jams across London Bridge, then the only link with the south bank, mingling with the crowds of brightly dressed Londoners shopping amidst the din in West Cheap and the open markets, or streaming out through Ludgate along the road which led over the river Fleet to Westminster.

The emergence of a prosperous fur trade in the capital appears to have been a development of the thirteenth century, a century during which significant changes took place in the population and institutions of the City. (fn. 19) Probably the most remarkable factor in city life was the pressure of rapidly increasing numbers. Assessments of the population of medieval London vary, but it may well have doubled between the early thirteenth and the early fourteenth centuries, an increase reflected particularly in the intensification of settlement within and without the walls. (fn. 20) Many of the new-comers were immigrants from the Home Counties. Many others came from the east Midlands and the North; among them were merchants, lawyers, and clerks, quick to take advantage of the opportunities of city life. (fn. 21) Humbler craftsmen and labourers, too, struggled to secure a foothold in the vigorous and bustling society of the City.

London's trade and industries flourished as her population grew and as she became increasingly a focus for the expanding European commerce of the thirteenth century. Her merchants, while overshadowed at first by the aliens who then dominated English overseas trade, played their part in the developing trades in wool, wine, cloth, and spices, and by the end of the century came to carry an increasing proportion of such goods. Some Londoners, exporters of wool, benefited from the rapidly expanding trade in Baltic commodities as German merchants extended their sway along the Baltic coasts; others profited from the trade in Spanish leather and iron; and still others from the trade in Gascon wines. Thus new mercantile interests pushed to the front in London society: fishmongers, skinners, leatherworkers, girdlers, corders, and ironmongers.

We know little of London skinners in the early years of the thirteenth century except that they existed and sometimes worked for the King. (fn. 22) Yet an occasional glimpse may be caught of dealers in furs, men who no longer concentrated their energies on making furs, but bought skins, employed others to make them up, and then sold the furs. Two London citizens, for instance, were displaying furs for sale in Northampton in 1226, others sold them in York in 1252. (fn. 23) A more prominent Londoner was Radulphus Pelliparius, or le Parmenter. It was he who produced the luxurious silks and furs in which King John delighted, furs of ermine and vair, coverlets of otter and gris, and one of samite and sable, edged with ermine. (fn. 24) He eventually rounded off a successful career in the royal service by marrying the granddaughter and heiress of Henry Fitz Aylwin, London's first mayor. (fn. 25) By 1250 a group of London skinners, specifically described as 'merchant skinners', were trading with the King on a scale which indicates that a prosperous and flourishing industry lay behind them. (fn. 26)

Only one London skinner, John de Northampton, was successful enough at this time to make his way among the patrician families in the City. John was fortunate enough to secure the royal custom, always a key factor in the City's economy, and although he bought wax and timber on the King's behalf, his sales to the King were predominantly of furs. Thus in 1259 he sent to Gascony, for Henry III, furs worth £164. 2s. 0d.; between the years 1250 and 1259 a total of more than £1,000 was paid to him, nearly all for furs. (fn. 27) He also sold furs to the Countess of Leicester, and most probably to other members of the nobility and Church. (fn. 28) His remarkable achievements culminated in marriage into the Viel family, one of the powerful aldermanic families of the time. (fn. 29)

While John de Northampton's success set him apart in his generation, other merchant skinners followed in his footsteps. (fn. 30) Rarely were skinners to be found among the richer merchants of the City, men whose chief interest lay in the import trade; the majority were comfortably prosperous middle-class citizens. Their intermediate position is revealed by assessments for the payment of subsidies in 1292, 1319, and 1332. The fishmongers, who may be regarded as roughly representative of the powerful victualling interest, were far wealthier; the cordwainers, broadly representative of the industrial classes, were far less prosperous than the skinners. (fn. 32)

Assessments of Londoners for Payment of Subsidies (fn. 31)

Assessments of Londoners for Payment of Subsidies [table continued]

Assessments of Londoners for Payment of Subsidies [table continued]

A similar story is told by an analysis of the craft affiliations of those who became mayors or aldermen at this time. From 1290 to 1365, two mayors and eleven aldermen were drawn from among the skinners, whereas the fishmongers and mercers each produced six mayors and twenty-three aldermen, and the grocers seven mayors and twenty aldermen. (fn. 33) But the skinners had drawn well ahead of the leaders of the other leather trades with whom they had probably once been closely linked. While a small group of merchants, known as 'leathersellers', emerged from the leather crafts in the first half of the fourteenth century, only one of them reached aldermanic rank. (fn. 34)

The records tell us something of the status of the skinners as a social group; they tell us more of their personal fortunes. They were traders like Thomas de Hereford, who owned property in Hereford and in three London parishes, who sold furs to Henry III, and who kept a shop in the Peltry in West Cheap and one in Winchester as well, which indicates no doubt a particular interest in the fair of St. Giles. (fn. 35) Thomas de Oxford counted the wealthy Bogo de Clare, son of the Earl of Gloucester, among his customers, and was able to leave £100 to his children on his death. (fn. 36) William de Hanington comes more vividly to life, as a prominent citizen making arrangements for a loan to the City, acting as warden at St. Botolph's Fair, and trading there. He proposed to pay partly in marten skins the builder who had agreed to make his new house, with porch at the entrance to the hall, recess and window behind the high table, chimney in the parlour, solars, kitchen, and stable. (fn. 37) The arrangements made for the guardianship of his children after his death in 1313 focus attention on one of the most revealing facts about this group of skinners: the close personal relationships which bound them. William de Hanington's widow married a skinner; of his three children, the mother became guardian of one, with three skinners standing as surety, and similarly two other skinners became guardians of the other two, another six skinners standing as sureties for them. (fn. 38) Not only were the skinners close personal friends but they took common action in public affairs, when, for instance, Hanseatic merchants needed Londoners to go bail for them, or when one of their number was in difficulties for his scathing description of the Mayor as the 'lowest of worms'. (fn. 39)

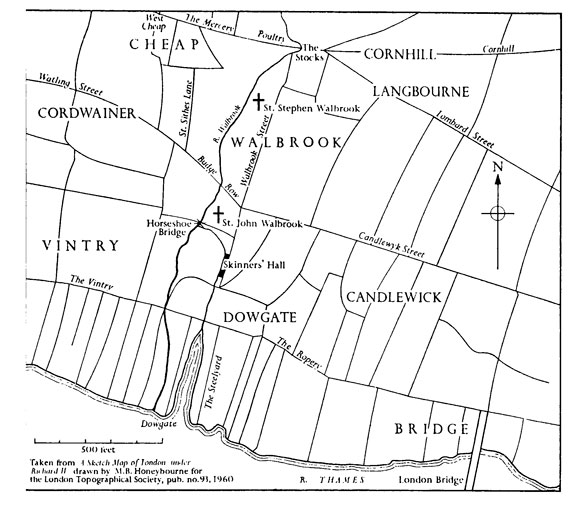

Then, too, many of the merchant skinners lived near together. The Peltry in West Cheap is first mentioned in 1274, and the shops and homes of skinners extended from Cheap southwards, near the banks of the River Walbrook, to the Thames. (fn. 40) Skinners served Walbrook ward in many capacities: they were its aldermen, they collected its taxes, and they supervised the cleansing of the watercourse. (fn. 41) Of inhabitants of the ward whose occupations can be identified the largest single group were skinners. (fn. 42) Shops and other property passed from one to another, and many of them must have lived in neighbouring houses. (fn. 43)

Map A: Medieval London—Sketch map of the Walbrook area

Such close personal and business connexions undoubtedly help to explain the ease with which merchant skinners drew together to organize their trade. Their association took the form most usual in thirteenth-century London, that of a fraternity attached to a parish church, in this case St. John the Baptist, Walbrook; (fn. 44) but whether the fraternity was actually founded by skinners or only slowly came to be dominated by them, we do not know. (fn. 45) Such evidence as survives of the thirteenth-century fraternities suggests that, whatever part religion may have played in their foundation, their development was often conditioned by the secular interests of their members. Professor Van Werweke has suggested in connexion with the history of some continental gilds that where political developments made open avowal of the secular aims of the trades possible, little emphasis was laid on their religious element, but that where this was not possible, the associations grew up under the protection of the Church. (fn. 46) This was certainly true of thirteenth-century London. Only in the closing years of that century did the city authorities show any inclination to recognize corporate organizations among the London trades. Any link with the Church, therefore, which made possible the enforcement of ordinances agreed to on oath by appeal to ecclesiastical courts was of great value. Fraternities such as those of the smiths and spurriers of the late thirteenth century mantained candles in honour of their saints, and supported the poor; but they also collected contributions in a casket for their confederacy, made decrees affecting workmen, such as that none should work at night, and exacted an oath from their members, which the ecclesiastical courts then enforced. Thus a spurrier's servant was once excommunicated for working between sunset and sunrise. (fn. 47)

For the most part the deliberations of these fraternities were jealously guarded behind closed doors and only a few scraps of evidence survive to indicate the nature of some of the activities of the fraternity of the merchant skinners in the late thirteenth century. In 1272 some London skinners were jointly involved in a payment of £13; similarly in 1278 they jointly held a room in a private house. (fn. 48) In 1288 they secured the proclamation of an ordinance, drawn up in the presence of nineteen leading members of the trade, elaborating the grounds on which work might be considered 'good and lawful' : it provided that a certain number of skins were to be worked in each fur, and that skins of different varieties, or old and new skins, were not to be worked together. Those disobeying the decree were to be put in the pillory and their work forfeited to the city. (fn. 49) It is probable, too, that they were involved in the payment of £4 annually to the Abbot of Westminster for the hall of the skinners at the Fair of Westminster, noted in a charter of 1288. (fn. 50) From 1293 onwards the skinners were presenting regularly to the mayor and aldermen, in accordance with a decree dated 1285, men to be sworn as brokers in peltry to serve as intermediaries with alien merchants. (fn. 51) Surveyors of peltry on Cornhill were appointed as early as 1319. (fn. 52) Then in 1327 the skinners were in a position to secure a charter from Edward III.

Thus little direct evidence survives to shed light either on the corporate activities of the merchant skinners or on the reasons why they found joint action desirable in the late thirteenth and early fourteenth centuries. But a study of this critically important period in the history of London soon reveals that the purposes for which they used their fraternity were both political and economic in character. The grant by Edward III in 1327 to them, and to only three other London misteries, of hitherto unknown privileges, and municipal recognition of other organized misteries in 1328, may then be seen as the culmination of half a century of bitter struggle. (fn. 53)

During the second half of the thirteenth century merchant skinners were among the leaders of the rising middle class, members of rapidly growing and particularly prosperous trades. Yet they found they were virtually excluded from sharing in the government of a city which had for over half a century exercised a measure of control over its own affairs. Judging from what was eventually achieved they had three main aims: they wanted a share in high office; they wanted an assembly representative of their interests to be recognized and consulted; and they wanted to ensure that in a city with a rapidly growing population and an expanding economy their privileges as members of the community were respected.

In the middle years of the thirteenth century their chance of achieving any of these aims, presumably then scarcely formulated, would not have seemed promising. As a result of John's recognition of the Commune in 1191, London was ruled by a mayor, chosen from among the aldermen, and his council of 24 aldermen, each representing a ward of the City. (fn. 54) Power was in fact in the hands of a group of sixteen closely related patrician families, wealthy landowners, merchants, and men who prospered in the royal service, from whom 85 per cent. of the newly elected aldermen were drawn in the decade 1240–50. As freemen the successful tradesmen had some say in the election of aldermen and were represented in the big meetings which selected the mayor and sheriffs. They had the duties of contributing financially to the upkeep of the City and of helping to maintain order. The privilege of trading within the city was, as was usual, restricted to them and to other specially privileged bodies, and they were free from the payment of toll throughout England and of custom in London. Yet in a city bursting at the seams with immigrants, but with no very adequate means for ensuring that only those who were freemen exercised the privileges, these had little meaning.

The leaders of the prosperous misteries made determined attempts to remedy this state of affairs. Their first opportunity, brought about indirectly by the conflict between Henry III and the ruling oligarchy in the City, came in 1263 in the wake of the baronial wars. A popular mayor, Thomas fitz Thomas, was prepared not only to recognize the right of some of the trades to regulate their own affairs, but to recognize that the 'Commons' of the City had a right to some place in its government. The success of the rebels was shortlived, and further revolts in 1267 and 1272, while they suggest the strength of feeling to which they gave expression, were also crushed. But the situation changed dramatically when Edward I put into action his plans for integrating his prosperous but turbulent capital into his realm. He worked first through a mayor loyal to him, but from 1285 to 1298 directly through a royal warden, and despite the increasing resistance of the citizens it was only the constitutional crisis of 1297 which forced him to give way to them and to restore the liberties of the City by his charter of 1299.

In many ways royal intervention worked to the advantage of those misteries like the skinners' which had already some organization behind them ready to seize the opportunities given to them. The aldermanry was no longer a closed oligarchy: men from trades hitherto unrepresented, from new families, had supplied 52 per cent. of the aldermen during the period of royal control, and from 1298 to 1307 only 4 of the 22 aldermen were drawn from long-established aldermanic families. In 1300 there were 3 skinners among the 24 aldermen, another had already been sheriff in 1296, and a fifth was to be sheriff in 1301. (fn. 55) Thus the Court of Aldermen of the early fourteenth century was much more sympathetic to the interests of the organized trades.

Then, too, civic administration had been transformed. Procedure had become more formal, records were more systematically kept, and a professional bureaucracy, headed by a highly paid Recorder, was growing up. Ordinances for the maintenance of order were revised and more efficiently enforced, judicial procedure brought into line with that elsewhere, and much of city custom codified. (fn. 56) The misteries, some of which had already shown considerable capacity for action and a desire to regulate their trades in their own interest, were then singled out as units to whom increased responsibilities could be given. The 'better, more discreet men' in each mistery were ordered to draw up lists of their members, to keep registers of apprentices, and to present those whose behaviour was unsatisfactory. (fn. 57) The skinners, like several others, were encouraged to formulate decrees which, with the force of municipal recognition behind them, would ensure that only soundly made furs were sold. By 1312 it was agreed that such ordinances should be registered and read publicly once or twice a year. (fn. 58)

The merchant skinners had been in a position to put forward ordinances for the manufacture of furs in 1288, only three years after the appointment of the royal warden. (fn. 59) In 1300, faced by a conspiracy on the part of the tawyers to increase the rates at which they dressed the skinners' pelts for them, they were able to take action which reflects even more decisively the extent to which their authority was established at this time. Rates on a piece-work basis were fixed : 5s. or 6s. for dressing one thousand greywerk, and for other squirrel and coney skins accordingly. The relative importance of the two crafts is revealed by the fact that penalties for breaches of the agreement were to be fixed by three skinners and one tawyer. (fn. 60) Trading in skins and 'other things belonging to peltry' was assumed to be a prerogative of the skinner, and it is easy to see the hand of the wealthy industrialist behind the attempt in 1304 to stop a tawyer from selling dressed skins. (fn. 61)

But while Edward I's policy gave the organized misteries both responsibilities and opportunities, in one important direction he aroused the bitter resentment of all citizens, merchants and shopkeepers alike. It was partly his concern for his financial resources which had directed his attention to London, and one of his main objects was to remove any obstacles to the free flow of trade throughout his realm. He tried to encourage trade in the City by taking alien merchants under his protection and by facilitating trade between aliens and non-freemen. He even went so far in 1285 as to order the admission of aliens to full rights of citizenship. (fn. 62) Although he had to give way over this by 1299, the status of alien merchants was more fully defined, in return for the payment of increased customs duties, in the Carta Mercatoria of 1303. (fn. 63) Edward's policy had run counter to medieval urban custom: it was generally understood that only members of the community, rather than all domiciled within a city's walls, should share in its privileges, of which the right to trade retail was one of the most valued. Londoners reacted violently to this threat to their long-established traditions, which were in any case seriously endangered by the continued growth of the City's population and the growing intensity of the competition they had to meet.

This period therefore saw a prolonged battle to protect the privileges of citizenship, in which the lead was taken by the organized misteries. This was directed not only against aliens but against immigrants from the provinces and other foreigns in the City. (fn. 64) While administrative reforms had made it easier to discover who was a freeman and who was not, they also facilitated the clarification of the respective positions of freemen and non-freemen, drives to ensure the registration of freemen, and enforcement of the payment of taxes. Thus while there was uncertainty in 1292 as to whether some men assessed for payment of subsidy in that year were citizens or not, there was none in 1319. (fn. 65) When Robert Persone, one of the wealthiest of London skinners, persisted in trading without taking up the freedom of the City, the authorities elected him as sheriff in 1309, assessed him for taxes, distrained on his goods, and shut up his shop when he refused to pay. Robert found it easier to evade his civic responsibilities by securing, through the good offices of the Earl of Gloucester, Letters Patent exempting him for life from all taxes and offices. (fn. 66) But many others submitted, and over 900 men were enrolled as citizens between 1309 and 1312. (fn. 67) Twenty-nine of these were skinners, twenty-two of whom were enrolled, presumably as the result of a campaign by the freemen skinners, in the November and December of 1309. (fn. 68) Judging from their subsequent appearances in the records many were poor, or were possibly elderly, and the attitude of many of them may have been expressed by William de Broughton, who complained bitterly, when asked for 26s. 8d. for his freedom, that the authorities were trying to drive him from the City. (fn. 69) Eventually in 1319 the way was opened for full control of admission to citizenship by the organized misteries when, in the charter granted to the City by Edward II, it was decreed that non-freemen wishing to exercise a craft in the City had to be sponsored by six men of that mistery. (fn. 70) Then, says the chronicler, 'many of the people of the trades of London were arrayed in livery and a good time was about to begin'. (fn. 71)

One other important development of these years also strengthened the position of the organized misteries in the constitution of the City, and was the result of their activities in preceding years. The charter granted in 1319 procured for the 'commonalty', or assemblies representing the 'commons' of the City, soon to be known as the Common Council, a place in the constitution beside the mayor and aldermen. (fn. 72) This broadened the basis of the City's governing body by including not only the wealthy merchants but the leaders of the middle classes in its deliberations. While these representatives were then elected by wards, the time was to come when the organized misteries would try to secure control of this process.

After the successive crises of Edward II's reign, Edward III, in gratitude for the help given to his cause by Londoners, confirmed the privileges and liberties of the City by his charter of 1327. London slowly emerged as a more stable community with a balanced constitution, its autonomous position accepted by the Crown and its authority never again to be seriously challenged. (fn. 73) Then the fraternities within the trades, which had undoubtedly been instrumental in bringing about some of the changes of preceding years, could come out into the open, seeking municipal and royal recognition of their corporate existence and of their control of trade. Four misteries, of which the skinners were one, received royal charters in 1327; (fn. 74) at least twenty-five were being permitted by the aldermen to elect governors in 1328. (fn. 75)

By the middle years of the fourteenth century London skinners were well on the way to dominating the English trade in luxury furs. As the vigorous and enterprising leaders of a prosperous and flourishing industry, the London merchant skinners had been quick to combine to achieve their ends and to seize what opportunities arose. The growth of London and its increasing importance in the English economy further strengthened their position. The court spent more time in London, more government institutions made it their home, and many other bodies, from monastic houses to firms of Italian merchants, found it convenient to maintain a base in the City. London skinners benefited, for instance, as did London drapers and mercers, from the administrative changes of Edward II's reign, which confirmed the separation of the office of the Great Wardrobe, the body mainly responsible for clothes and liveries, from the Wardrobe, the executive body of the Household, and brought to an end its peripatetic existence. (fn. 76) With the establishment of the Great Wardrobe in London in its own buildings, which included a peltry by 1364, it was obviously much easier for furs to be bought and workmen drawn from Londoners. (fn. 77)

The growing dominance of the London skinners is particularly well illustrated by accounts of purchases of furs made for the King. Whereas in 1250 furs were bought for the King from small traders, many of them probably skinners from different towns who frequented the fairs, (fn. 78) as well as from London merchants and skinners, a century later London skinners almost monopolized the valuable trade of supplying the royal household. Edward I's clerks, like those of Henry III, bought only occasionally directly from London skinners; they preferred to buy through one of the greater merchants appointed purveyor to the Wardrobe or to buy from provincial skinners such as, for instance, those of Reading or York, or from Italian merchants; at other times they bought furs in Paris or Flanders. (fn. 79) It was not long, however, before one London skinner, Robert Persone, was trading directly with the Great Wardrobe on a scale which helped him to become, in 1319, one of the three richest men in the City. (fn. 80) While he was an unusually successful skinner, his activities present an interesting picture of the wealthy merchant and industrialist, and indicate the capital, energy, and ability which was helping to build up a thriving industry.

Little is known of Robert's family or background and he made no mark on the political history of the City. His chief interest was in his business, which must have brought him very comfortable profits. His shop was in Walbrook, and his sales were chiefly of furs and counterpanes of gris and minever. (fn. 81) The extent of his retail trade can be inferred from the quantities of furs bought from him for the King, and from the sums of money owed to him by the nobility and clergy, most of them probably for furs. Bills owing to him by the King in 1315 for purchases covering a period of eighteen months totalled £594. 15s. 8d.; (fn. 82) in 1327 he petitioned for the payment of £231. 0s. 7d., and he provided furs worth £102. 14s. 1d. for the coronation of Edward III. (fn. 83) Prominent men like Richard de Grey, Lord of Codenore, and the Prior of the Hospital of St. John of Jerusalem owed him money. (fn. 84) Yet Robert was much more than a shopkeeper: his interests took him to Flanders, as they did other skinners at this time, where he sold wool and presumably bought skins on his own and the Kings' behalf. (fn. 85) At other times he turned to the English fairs, and was on good terms with Hanseatic merchants, trading in other Baltic commodities such as wax, as well as skins. (fn. 86) Of Robert the employer we know nothing. When he was sent abroad to purvey pelts for the Great Wardrobe, he and his men were taken into the King's protection, and we can only assume that there were several men dependent on him for their livelihood. (fn. 87)

Shortly after Robert's death his London friends and business associates virtually controlled the trade with the Great Wardrobe. The greater part of the £960. 11s. 3d. spent on furs in 1329 passed through the hands of Roger de Nettlested and William de Cave, and during the years from 1330 to 1335, except for some purchases from Hanseatic merchants and a Genoese, eight of the other nine suppliers were London skinners. (fn. 88) William de Cave alone handled £1,239. 2s. 8d. for furs bought during those five years, and a further £1,014. 18s. 5½d. for purchases during the year 1344 to 1345. (fn. 89) From this time, although skins were sometimes bought direct from Hanseatic merchants and occasional purchases made in Bruges, London skinners controlled the trade. And from 1405 a King's Skinner was appointed and made responsible both for the purveying of skins and furs and for work on furs within the Great Wardrobe. The appointment went always, with only one possible exception, to a London skinner. (fn. 90)

This concentration of royal purchases in London made the City the great centre of the luxury trade, the place where wealthy customers could expect to find what they wanted. The Black Prince paid a London skinner £100 for furs and other goods delivered in 1346, and John of Gaunt entrusted one of his ermine counterpanes to a London skinner. (fn. 91) The liveries of budge in which Hugh Despenser clothed his men were also bought in London. (fn. 92) Sir John Howard, later first Duke of Norfolk, contented himself with the services of a skinner from Bury St. Edmunds when he wanted his jacket lined with lambskin, but when he wanted mink skins and a gown furred with them, he turned to a London merchant. (fn. 93)

The growth of the market drew country customers. Some of the London merchants had probably maintained a connexion with their home counties. Among them was John Trethewy, presumably a Cornishman, who at one time or another summonsed gentlemen from Cornwall, Somerset, and Hereford, as well as a rector from Dorset, for the money they owed him. (fn. 94) Even quite small London shopkeepers benefited from this country trade: Thomas Betele, who began in a very small way with little more than £1 worth of stock, later sued a gentleman from Wiltshire and a clerk from Lincolnshire. (fn. 95) Clerks from York and Cambridgeshire, gentlemen from Bridgwater, Hereford, Northampton, Chester, Huntingdonshire, Yorkshire, and Hertfordshire all owed money to London skinners, as they did to London tailors, drapers, and mercers. (fn. 96) Sir William Pennyngton, knight of Muncaster, Cumberland, even went so far as to list in the will he wrote in 1533 debts to his London skinner, mercer, hosier, and tailor. (fn. 97) Thus from the fourteenth century onwards there had grown up among the English nobility and country gentry the tradition that their best clothes and furs should be bought in London.

For a lively evocation of the thirteenth-century city, see G. A. Williams, Medieval London: from Commune to Capital, London, 1963, pp. 9–25.